ABSTRACT

Background

Given the various novel educational approaches and online interactions following the pandemic, it is timely to identify lessons learned for post-pandemic student and teacher relationships within the ‘new normal’ teaching learning processes. This study aims to explore the dynamics and to what extent the disruption influences student-teacher relationships in teaching and learning process following the COVID-19 pandemic.

Materials and Methods

A qualitative descriptive approach was employed to explore individual reflections and perspectives from 28 medical teachers and 35 medical students from different institutions who participated in 10 focus groups. Data were analyzed thematically using steps for coding and theorization (SCAT) approach. The emerging themes were then further analyzed and regrouped into the relationship-centered leadership framework based on emotional intelligence.

Results

The identified themes described three elements representing student-teacher relationships in the teaching learning processes. The self as the center of the diagram consists of the co-existing role of the self as teachers and as students, which to some extent, is related to their personal and professional development, motivation, and struggles to maintain work-life balance. The middle layer represents the dynamic of student-teacher relationship, which showed that despite the increased number of teaching opportunities, the trust among teachers and students was compromised. These changes in the self and the dynamic relationship occurred in a broader and more complex medical education system, pictured as the outer layer. Thorough curriculum improvements, contents, and new skills were emphasized.

Conclusions

Our findings emphasized the need to recalibrate student-teacher relationships, taking into account the intrapersonal, interpersonal, and the system factors. The pandemic has reemphasized the aim of teachers’ roles, not only to nurture students’ competencies, but also to nurture meaningful interpersonal reciprocal relationships through responding towards both teachers’ and students’ needs as well as supporting both personal and professional development.

KEYWORDS: COVID-19 pandemic, student-teacher relationship, teaching learning process, medical education, personal and professional development

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has introduced new norms and affected many aspects in life. From an event system theory perspective [1], we can consider the pandemic as a ‘novel, disruptive and critical event’. Using the lens of this theory, the dynamic processes leading to strengths and weaknesses around the event can be explored further to identify its influences towards potential changes or new behaviors, disrupted organizational routines, and adaptation or improvisation of medical schools. Looking beyond the pandemic to identify which changes should be taken into the post-pandemic world is now relevant given that we have entered what Daniel et al (2021) call the ‘maturation phase’ in our long journey throughout the pandemic [2].

The increasingly challenging repercussion inflicted by the pandemic has demanded the need for learners and teachers to augment their individual emotional resilience, which were highly influenced by their interactions, apart from their individual traits and surrounding environments [3–5]. Focusing on the relationships is believed to have led to a more resilient learning environment. Social connections, interactions, and a sense of belongings in a learning community are known to be important in building meaningful and trustworthy relationships in healthcare [6,7]. Student-teacher relationships are also critical in supporting both learners’ and teachers’ professional identity formation through the mediation of the arduous journey involving individual characteristics, emotions, and reciprocal influences along the medical education processes [8].

Student-teacher relationship is an important aspect of teaching and learning process since, to some extent, it determines the quality of the teaching and learning process [9]. In his study, Abdulrahman (2007) found that medical students perceived the relationship to be good, with adequate teaching skills as the most important attribute of a good teacher [9]. The author further suggested the importance of nurturing a learning environment based on trust and mutuality. Central to this student-teacher relationship is managing a right balance between proximity and distance, i.e. close enough to facilitate learning and mentor, but distant enough for teachers to maintain objectivity and students to become more independent [10].

Unfortunately, despite a myriad of reports on novel educational approaches and digitalization during the pandemic [2,11], studies focusing on how the dynamics of online learning and interaction affect student-teacher relationships are still lacking. Studies have highlighted the well-being and needs of each party but have not yet looked at the interactions between students, teachers, and the environment/systems, although social connectedness is found to be one of the key factors affecting students’ well-being [12]. Simok et al (2021) argued that online interaction might hinder relationship building between students and teachers, some of which are caused by the speed and amount of information exchanged online [13]. Furthermore, these interactions might also be difficult to be monitored remotely [3–5].

With the abundance of experience during the pandemic, it is timely to identify the lessons learned for post-pandemic medical education, especially concerning student-teacher relationships in the teaching and learning process. What are the changes? What is to keep? What should we let go of? And what should be taken forward to the future? These questions reflect the need for organizations to discard the ‘past’ (values and practices that do not work) to create the ‘future’ whilst managing the ‘present’ [2,14] or in other terms, adaptive leadership [15]. Therefore, this study aims to explore the dynamics of student-teacher-environment relationships in teaching and learning process during the COVID-19 pandemic and to what extent the disruption influences on these relationships. The result of this study is expected to inform further adoption of medical education post-pandemic and required support for mutual relationships between students-teachers-environment/systems.

Materials and methods

Context

Indonesia currently has 93 medical schools across Indonesia, with the main medical schools located on Java Island, the country’s most populated and well-developed island. The medical schools in Indonesia have very different contexts, cultures, facilities, and resources, which affects the way they academically adapt in response to the COVID-19, however, generally Indonesia has high power distance and high collectivistic cultural dimensions [16,17], which to some extent would influence student-teacher relationships. Students in Indonesia can enter medical school directly after graduating high school. Programs are mostly 5.5 to 6 academic years (3.5–4 of preclinical years and 1.5–2 years of clinical years) in duration at the end of which students are awarded a degree in medicine and required to obtain one compulsory national internship program before receiving a practicing license.

Study design and participants

A qualitative descriptive study [17] was employed to explore individual reflections on current student-teacher relationships following the pandemic and understand these from the perspectives of medical students and medical teachers. Twenty-eight medical teachers and 35 medical students from different medical schools throughout Indonesia were recruited for the study using maximum variation sampling, considering factors such as gender, medical school status (private or public), and location (in or outside Java Island- as the most populated island in Indonesia), clinical/non-clinical background and length of teaching experience (for medical teachers), and study year (for medical students) Participants were invited to participate through emails and chat messengers. Prior to participation in focus groups, participants were provided with information about the study and a consent form.

Data collection

Ten online focus groups (FG) (3 preclinical student/PCS FGs, 2 clinical student/CS FGs, 3 preclinical teacher/PCT FGs, and 2 clinical teacher/CT FGs) were conducted using the Zoom Meeting platform. Eight to twelve respondents from different medical schools participated in each 1.5 to 2 hour focus group. FGs were conducted in Bahasa Indonesia, they were audio-recorded and moderated by the core researchers (A,B,C,D,E) who are medical educationalists. An interview schedule guided the FGs with probing questions developed from the existing literature in regards to teaching learning adaptation processes, changing roles, as well as the change management following the COVID-19 pandemic Table 1 . The researchers leading the FGs were briefed to ensure a standardized approach in asking the interview questions. Data saturation was reached after the eighth FGs, however, the ninth and tenth FGs were still conducted for further data triangulation.

Table 1.

Focus group interview Schedule.

| Main questions | Probing questions |

|---|---|

| Tell us about your roles and experiences over the years within the pandemic? | What are the highlights and lowlights? |

| What were the changes (made by you or others) to how you have taught/learned during this time? | What might be falling through the cracks as a result, especially in the teaching and learning process, in the relationships between students-teachers, and other aspects? |

| How have you or others decided where to prioritize/focus your time, attention, well-being and other related aspects? | |

| what are the opportunities you had based on the changes? | |

| What do you think has helped/hindered of the teaching and learning adaptation process/changes and its results? | How prepared are you with the changes? |

| What helped you manage this shift/change? | |

| What do you think has helped/hindered of the adaptation process/changes and its results (internal or external factors)? | |

| How has the pandemic placed new/different demands on your role and relationships as a teacher/student? | Have you had to step up to a new/different role? |

| How prepared did you feel for this? | |

| Has there been any changes in your identity (as teacher/student) currently? | |

| What are your expectations towards yourself, students/teachers, and medical education following your experience during the pandemic? | What do you think are important for current medical education and that beyond COVID-19 pandemic, especially related to student-teacher relationships within the larger environment in medical education? |

| What do you want to keep/bring back? | |

| What do you want to let go? | |

| Why do you think that you want to keep/let go certain aspects within medical education? | In regards to the competencies and professionalism of doctors? |

| In regards to teaching and learning process in medical education? | |

| In regards to student-teacher relationships? |

Data analysis

The verbatim transcripts of each FG were analyzed using the steps for coding and theorization (SCAT) approach as guidance in analyzing the content to identify concepts expressed by the participants [18]. Students’ and teachers’ views [19] were combined to comprehensively understand how both stakeholder groups identified important lessons learned on teaching learning processes following the pandemic. We also explored individual characteristics, emotions, and reciprocal influence, as they may influence interactions among teachers and students [8]. As student-teacher relationships were important aspects in teaching learning processes, the emerged themes were then further analyzed and regrouped using the leadership framework that hinges on the interactivity among stakeholders within an organization, based on emotional intelligence, which consisted of three domains: (1) self (personal and professional domain); (2) interpersonal relationships and teamwork; (3) sense of belonging to a community and systems [7]. Two researchers (A,B) analyzed the first two transcripts independently, and any disagreements were discussed and resolved. All researchers analyzed the later transcripts against the agreed framework, and any new concepts or features arising were added subsequently.

Reflexivity

Authors (DS, NG, AF, RM, EF) are medical educationalists and have health professional backgrounds (i.e medicine or dentistry), whereas two other authors (MA and BPA) are medical students. They were personally and professionally affected by the pandemic and had been adapting to teaching, learning, and assessment processes in undergraduate medical programs before, during, and after the pandemic. Their perspectives and experiences were therefore contributive to the interpretation of experiences being shared in this study.

The core researchers (DS, NG, AF, RM, EF) led focus groups with invited respondents from different institutions. Moderators may know some of the study participants, however, data analysis of each FG was conducted by different authors to ensure objectivity of data analysis.

This study has been granted ethical clearance from the Faculty of Medicine Universitas Indonesia Ethics Committee (number: KET-1239/UN2.F1/ETIK/PPM.00.02/2020)

Results

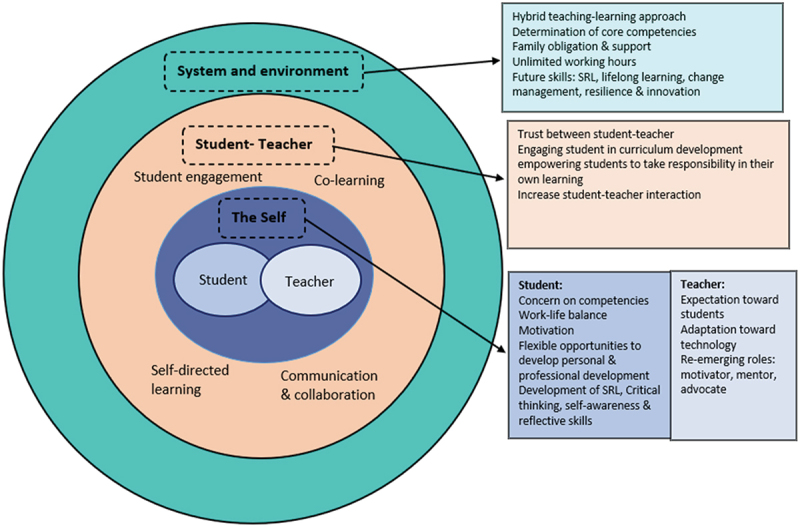

Identified themes were grouped into three elements representing the dynamics of interactions among stakeholders in teaching learning processes. In the center of the diagram, the self as teachers and the self as students co-exist, and in the middle layer, the relationships between the two, teachers and students, are formed. This relationship exists in the context of an overarching medical education system, including curriculum, teaching-learning process, and many more in the outer layer.

Figure 1.

The framework of student-teacher relationships in teaching learning processes beyond the COVID-19 pandemic.

The self

The inner layer of the framework is the ‘self’ factor of either the students or teachers, which highlighted the intrapersonal factors influencing the student-teacher relationships following the COVID-19 pandemic. These intrapersonal factors in students side consisted of students’ concern on competencies attainment, students’ awareness to maintain work-life balance and motivation, students’ flexibility for personal and professional development, and their awareness to maintain soft skills (i.e. self-regulated learning, critical thinking, self-awareness, and reflective skills.

Whilst the intrapersonal factors of the teachers’ side consisted of expectation towards students especially in relation to their competencies, challenges to adapt towards technology, and their new re-emerging roles beyond teaching.

Students

Students mentioned how they were concerned about their competencies’ attainment due to the limitation of distance learning during the pandemic. However, students also suggested how flexibility of distance learning created new opportunities for their personal and professional development which were not accessible before the pandemic due to the timing, location and financial barriers. Therefore, the ability to maintain their motivation, work-life balance, and to practice self-regulation became more important following the pandemic.

Since I commenced my clinical clerkship during the pandemic, I don’t really know whether I am ready or not to be a doctor. (SN-CS-1)

… Activities that are held in other cities or provinces are more easily accessible, as we do not need to be present in person. So, there are many opportunities, but it goes back to how we can take advantage of them. (B-PCS-3)

Students were responsible for maintaining their work-life balance and acquiring skills to manage their time, priorities, emotions, and mood. Maintaining motivation became even more critical since online learning could be tedious and exhausting. Students highlighted self-regulated learning and critical thinking skills as new skills that emphasized their need to take responsibility, reflect, and regulate their own learning.

… But by participating in multiple activities simultaneously, the increase in quantity is not always followed by quality. It might be necessary to manage our priorities first and reorder whichever task is more important to avoid becoming overly fatigued… (P-PCS-1)

Because we do not see our friends around (to look up to), we rely upon ourselves. We are forced to be more aware of our own responsibilities. When we realize how we are left behind in our studies nowadays, it was different from how it used to be in offline learning when we feel more secure (about the situation) and (are) less aware (of our progress). (I-PCS-2)

Teachers

From teachers’ perspectives, it was found that some teachers shared similar worries with students about obtaining the necessary competencies, thus affecting their expectations about the students. Teachers also described adaptation towards technology and their new re-emerging roles beyond teaching were prominent following the pandemic.

Teachers revealed how they had to adjust their expectations of students’ academic performance in this challenging time.

We need to compromise our expectations. For example, research (projects) has changed to using secondary data since primary data collection is no longer possible. (D-CT-1)

Teachers mentioned how aside from the challenges to quickly and continuously adapt to technology, i.e. creating digital animation and developing online quizzes, teachers identified their changing roles from teaching to becoming students’ motivators, mentors, and advocates for students’ needs.

There’s also more involvement in roles as a negotiator, especially between the clinical teachers, who refuse to sacrifice the quality of education for the sake of students’ clinical competence … and parents, who are concerned about the extension of their children’s study period… (S-CT-2)

In the early days of this pandemic, apart from being a lecturer, I also took on the role of a motivator. Because I believe that I need to motivate my students that, despite this pandemic, they will finish becoming doctors. There were cases that students refused to be involved in taking care of COVID-19 patients, but I understand that I can’t force them to do so. So, I provide motivation, appreciation, direction, and motivation so they are willing to learn. I think we need to show them that we are on their side. (MA-CT-2)

The system

The changes in students’ and teachers’ self-perceptions did not occur in a vacuum but rather in a broader and more complex system of medical education (the most outer layer), which consists of the hybrid teaching-learning environment, determination of new core competencies, family obligation and support despite the unlimited working hours, and reemphasize on the future soft skills such as self-regulated learning, lifelong learning, change management, resilience, and innovation.

The pandemic has influences towards the teaching process, both in the skills and cognitive domains. Participants described the great reduction in learning opportunities for skills teaching both in the clinical skills laboratory and in the clinical setting, such as hospitals. The learning process of cognitive domains also changed. The pandemic has forced educational institutions to move to hybrid teaching and learning approaches. One of the most appreciated changes by the students was the opportunity to re-learn materials through video recordings of lectures or discussions.

This pandemic is like a catalyst. It is an opportunity for us to create the changes we have been hoping for, especially in terms of e-learning. Before the pandemic, we did not use a learning management system at all. (PD-PCT-3)

Participants highlighted that the curriculum needed to improve in various aspects. The first was selecting and determining the competencies and which competencies were core. The students also acknowledged the importance of peer support in terms of near-peer teaching or peer-assisted learning.

But now with limited patient contact, … we start to think … what are the most critical aspects of learning?… This is a very valuable process…, as we focus more on managing what is needed by the students to achieve competency while deciding which can be performed online or offline. (D-CT-1)

Topics such as one- health, interprofessional education, health promotion, disaster management, and universal precautions were considered lacking in the existing curriculum, and the pandemic has emphasized their importance. The pandemic has revealed the importance of explicitly teaching self-regulated learning and lifelong learning to students. Change management, resilience, innovation, and a growth mindset are other skills needed by both students and faculty to help them learn, re-learn, and adapt to future disruptions and change.

Many things happened quickly and made us anticipate and act immediately, work and learn, and as I always say to my students, ‘you will become a doctor that works in the future… So don’t become a person that accepts the system as it is’. (C-CT-2)

Some students revealed how family support was important for them at the current time, however, some described that obligations towards their family cannot be avoided because they were in the house and sometimes these responsibilities distracted their studies.

Compared to online and offline learning, it feels more difficult now than before. Being at home, we are often asked to do chores around the house while classes are ongoing. If we refuse, a quarrel might break out instead. So maybe that’s one of the concerns. (DY-PCS-3)

Both students and teachers experienced unlimited working hours. Since everything can be done online, teaching and learning activities could occur after hours.

Our working hours become unclear. From the start of the pandemic, I told my family that the usual working hours will no longer be possible. Our usual hours range from 8 AM until 4 PM in the evening, with the work done when we arrive home. But now even at 6 PM, I am still reviewing clinical skill videos or group discussion assignments. So, the drawbacks would be unclear hours. (R-PCT-3)

Despite the conveniences, online learning creates an indistinct boundary between studying and our personal time, we have to be on standby 24 hours a day, and the information keeps coming in like suddenly a friend informs you about an additional assignment from the teacher beyond the regular working hours. (SI-PCS-2)

The dynamic relationships between students and teachers

The middle layer showed the shifts of student-teacher relationship seen following the pandemic, which involved the trust between student and teacher, the engagement of students in curriculum development, the empowerment of students to be responsible for their own learning, and the increased interaction among student and teachers.

Online learning, to some extent, increases the teaching opportunities of student-teacher interactions, especially for clinical teachers in teaching preclinical sessions. However, the quality of these interactions was influenced by the perceptions of the self and the new roles and experiences following the pandemic.

In fact, following the pandemic, there are more clinical teachers who can teach. It used to be very difficult for them to join as PBL [Problem-based learning] facilitators or resource persons in an undergraduate program. This online learning gives them the flexibility to arrange their teaching time with the hospital service hours. (YW-PCT-1)

It is no longer an excuse to cancel the class even when the teacher is out of town. There was this one time when one of my teachers gave lectures, but at the end of the session, the teacher limited the QnA session to only three questions because the teacher was about to have surgery. At that time, this online learning made it flexible for teachers. Before online learning was applied, teachers would cancel the class whenever they had an emergency. (SP-PCS-2)

There was this time when the resource person of our lecture session was having a parallel online meeting simultaneously during our class. We were told to watch the video lecture and asked questions afterward, but the resource person focused more on the other zoom meeting he/she was having. (RI-PCS-2)

Another example of how the relationships sit within the context of the teaching and learning process and are influenced by the perceptions of the self was that teachers perceived that during online learning they do not have enough control over students, leading to a lack of trust between teachers and students. Trust between teachers and students was mentioned as the challenges occurred due to the distance and online learning, teachers described not believing that students learned, and students felt that they were not trusted.

Before the pandemic, monitoring our student attendance and participation was much easier. But now, it is much more difficult to control these things. It has challenged students’ self-determination and proactiveness. (X-PCT-2)

… Faculty should put substantial effort into being more trusting because most lecturers are not convinced their students would access their recorded video lectures. They always believe otherwise. The trust of the faculty in their students is something that we must strive for. (M-PCT-3)

One crucial lesson from medical education was transforming the student-teacher relationship. More trust is required between each party, and students should be empowered and facilitated to take responsibility for their own learning. Students’ engagement in educational development should also be improved.

There is a change in the relationship between students and teachers, [we] need ways to ensure that students learn, and we need patience, as well, to understand if students encounter difficulties. (D-CT-1)

To strengthen the relationships among teachers and students in teaching learning processes, participants identified several measures, including optimizing student-centered learning, strengthening communication and collaboration between students and teachers, improving student engagement, and building awareness that students and teachers can learn and thrive together, learning from each other and complementing each other.

… No need to be ashamed to learn from the younger generation, we have to have the curiosity to learn. We never learn online; thus, we have to learn from our students the challenges faced when learning online, perhaps [the challenges] are the same as what the students faced and ones we encountered. (AD-CT-1)

Students’ creativity built during the pandemic can be used to create interactive teaching and learning and is still student based. Projects students conducted can be maintained. Next is collaboration, during the pandemic we are forced to collaborate with many parties, and this needs to be kept. (TB-PCT-2)

The pandemic has forced us to be creative in delivering learning materials, to ensure students pay attention and engage them. (X-PCT-2)

Communication and coordination between the faculty, teachers, and students are very important to decide the feasibility of particular policies made by the faculty. (TF-PCT-2)

Discussion

This study provides empirical data on the dynamics of and factors influencing student-teacher relationships in medical education following the COVID-19 pandemic, which were in accordance to the event system theory [1]. Our study has shed light on the perceptions of students and teachers on the shifts of relationship formed between student and -teacher and how to further support the development of such mutual relationships, taking into account the ‘self’ and the ‘system’ factors in which these relationships take place. Using the framework from Lisevick et al. (2022) we were able to identify the situation of the ‘self’ of both students and teachers, the interpersonal relationships between students and teachers, and how the relationship sits within a community or system [7].

Regarding the ‘self,’ the current study has underscored how medical students and teachers perceive themselves individually. Students in this study underlined the importance of strong motivation, time/priorities management skills, self-awareness and reflective skills, and self-regulated learning skills. At the same time, medical teachers in this study suggested that their roles as mentor/motivator/advocator/negotiator should accompany their increasing roles in technology literacy and innovation. Various roles of medical teachers, from information providers to mentors, change agents, and diagnosticians, have been recognized [20]. The current study adds or strengthens the adaptive roles which go beyond content expertise and teaching skills. These roles are highly relevant to the current situation and the need for the future where adaptive expertise is paramount. The adaptive expertise of students and teachers would allow for daily problem-solving and the flexible and effective use of knowledge and innovation, at the individual and organizational [21,22]. In addition, disruption of competence attainment, particularly clinical skills, was reported in this study and confirms the findings of previous studies on such challenges during the pandemic [2]. The disruption of competence attainment of undergraduate medical education during the pandemic, for example, further strengthens the importance of developing future experts who can adapt to changing situations [23].

The current study has also demonstrated significant changes in the environment or system of teaching-learning processes, as have been reported by other studies [24]. Students appreciate the opportunities to record teaching sessions which have helped them to learn theories and cognitive skills in more depth, and they will probably expect more frequent future use of a hybrid learning approach. The current study confirmed other reports in highlighting how skills teaching has been adapted, including the use of pre-readings and digital media, individual practice under supervision through video conferencing platforms [25], and virtual/augmented reality [26]. The flexibility of delivering the curriculum is one of the key findings on the system/environment factor, affecting the welfare and well-being of teachers and students. The use of online platforms increases the flexibility of time, venues, and modalities in teaching and learning, which may remove or blur the boundaries of work/study and personal time. Some participants mentioned that they valued the flexibility of online platforms which increased their opportunities for and access to personal and professional development, however, such availability risks impairing a good work-life balance (i.e. multitasking, unlimited working hours), which may then impact the quality of life. Reports underline that the workloads of teachers and students significantly increased during the pandemic [27,28].

This study also suggests the importance of a family support system for students and teachers in navigating new teaching-learning adaptations. A systematic review on student support systems suggests that during difficult times, both academic and mental health support are necessary [29]. This study highlights that the support should come from both formal and informal systems e.g. the curriculum and the family/friends given the hybrid learning environment. This argument is further supported by the results of a study in Portugal, reporting how the social isolation due to online teaching during the pandemic had reduced students’ social competences and interpersonal abilities, thus, given a strong collectivist culture in the Indonesian study setting, family and friends provide critical support for this development, even after the social restriction were lifted [30]. Furthermore, even the results of this study reported how being at home with family brought about some conflicting duties and obligations which distracted some students from their focus on learning, these conflicts were, to some extent, potential to act as social stimuli to further develop these important competence and abilities [30].

In terms of student-teacher relationship, one important finding is a shift in trust between teachers and students. Teachers revealed their concern over their lack of control over students, and students did not feel they were trusted enough by teachers. The online setting is physically borderless, but it can create a psychological boundary that can limit more profound interactions. Online learning interactions require more effort to ensure recognition of participation, availability of reflection and feedback, and exploration of students’ needs [31]. The current changes emphasize the need for nurturing and supporting effective student-teacher dialogue in a safe learning environment. Such a dialogue allows perspective-taking, building mutual understanding, minimizing distrust, and increasing an individual’s resilience [32,33]. Several measures to recalibrate the relationship between students and teachers, as demonstrated in the study findings, including optimizing student-centered learning, strengthening communication and collaboration between students and teachers, improving student engagement, and building awareness that students and teachers can learn and thrive together, learning from and complement each other. Therefore, students must realize they must take more responsibility for their learning. In contrast, teachers need to be more trustful, act as mentors and empower students to be responsible for their learning. Optimizing student engagement in curriculum development and medical education is also a way to establish a more mutual and supporting relationship between students and teachers. According to Xu et al. (2022), student engagement with the running of the curriculum improves the atmosphere and communication between teachers and students [34]. Moreover, the close interactions among teachers and students within a psychologically positive atmosphere following the COVID-19 pandemic promoted positive learning engagements and learning effects among students [35].

The COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted the way medical education was conducted for at least three years. We have begun to shift back to pre-pandemic medical education. Nevertheless, we should not take the lessons we had for granted. One of the important lessons learned, we argue, is the chance to recalibrate student-teacher relationships in the teaching learning processes. The online learning process during the pandemic has further emphasized and reminded everyone that teaching could not be merely about delivering content. The results of this study resonated how the essence of student-teacher connections, which values trust, respect, and mutuality, are keys to support students in health professions education [36]. Therefore, it requires more effort to pay more attention to students’ participation, engagement, and contribution to the learning process as well as teachers’ adaptations in response to students’ learning needs and their necessary skills development. Thus, effective teaching requires the formation of interpersonal context because learning is about constructing knowledge. Knowledge can be constructed effectively when it is in a particular meaningful context and personal for the students. Such meaningful relationships built between students and teachers can be an intrinsic driver for students’ learning. Student-teacher relationships in the teaching learning processes needs to be about the ‘person’ involved in the process, and it needs to be reciprocal [8]. Engaging students in curriculum development and other educational processes can be one way to achieve this reciprocal relationship, where students and teachers can collaborate and learn from each other.

Limitations of the study and further directions for research

This study was conducted in one country and in undergraduate medical education context, reflecting particular adaptations and circumstances hence perceptions and suggestions for the future are very contextual. However, we involved adequate representation of preclinical/clinical students and basic science/clinical teachers and, despite very few teacher participants holding leadership positions were included in this study, we argue that given the global impact of the pandemic and further considerations of various personal, interpersonal and sociocultural contexts, the paradigm retrieved from our current findings are relevant for other settings. Future studies could therefore be expanded in different countries, involving participants from postgraduate medical and other health professions programs, more educational leaders, and a focus on faculty development needs.

Conclusion

Based on empirical data, the current study has identified the dynamics influences of the COVID-19 pandemic on the student-teacher relationship in teaching learning process and how it needs to be recalibrated, taking into account the intrapersonal, interpersonal, and the system factors in which these mutual relationships take place. The results of this study reemphasized how teachers’ roles are far beyond teaching, aiming not only to nurture students’ competencies attainment, but also to nurture meaningful interpersonal student-teacher reciprocal relationships through responding towards both teachers’ and students’ needs as well as supporting their ability to self-regulate, reflect on their teaching/learning, and their personal and professional development, which are deemed to be even more critical in the future.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to extend appreciation to all respondents involved in this study and to Center for Indonesian Medical Students’ Activities (CIMSA) for supporting the data collections of this study. The authors would also like to thank Prof. Judy McKimm for her continuous support during the study.

Funding Statement

This study was funded by Grants of International Collaboration Universitas Indonesia 2018.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- [1].Morgeson FP, Mitchell TR, Liu D.. Event system theory: an event-oriented approach to the organizational sciences. Acad Manag Rev. 2015;40(4):515–10. doi: 10.5465/amr.2012.0099 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Daniel M, Gordon M, Patricio M, et al. An update on developments in medical education in response to the COVID-19 pandemic: a BEME scoping review. BEME Guide No 64 Med Teach. 2021;43(3):253–271. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2020.1864310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Huey CWT, Palaganas JC. What are the factors affecting resilience in health professionals? A synthesis of systematic reviews. Med Teach. 2020;42(5):550–560. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2020.1714020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Bird A, Tomescu O, Oyola S, et al. A curriculum to Teach resilience skills to medical students during clinical training. MedEdPORTAL. 2020;16(1):10975. doi: 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Findyartini A, Greviana N, Putera AM, et al. Felaza E.E.The relationships between resilience and student personal factors in an undergraduate medical program. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21(1):113. doi: 10.1186/s12909-021-02547-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Wenger E. Communities of practice and social learning systems. Organization. 2000;7(2):225–246. doi: 10.1177/135050840072002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Lisevick A, Dreiling J, Chauvin S, et al. Leadership for medical students: lessons learned from a relationship-centered leadership curriculum. American Journal Of Lifestyle Medicine. 2023;17(1):56–63. doi: 10.1177/15598276221106940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Haidet P, Stein HF. The role of the student-teacher relationship in the formation of physicians. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(1):16–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00304.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Abdulrahman KA. Students′ views on student-teacher relationship: a questionnaire-based study. J Fam Community Med. 2007. May;14(2):81. doi: 10.4103/2230-8229.97506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Plaut SM, Baker D. Teacher–student relationships in medical education: boundary considerations. Med Teach. 2011. Oct 1;33(10):828–833. doi: 10.3109/0142159x.2010.541536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Gordon M, Patricio M, Horne L, et al. Developments in medical education in response to the COVID-19 pandemic: a rapid BEME systematic review. BEME Guide No 63 Med Teach. 2020;42(11):1202–1215. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2020.1807484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Wald HS. Optimizing resilience and wellbeing for healthcare professions trainees and healthcare professionals during public health crises–practical tips for an ‘integrative resilience’approach. Med Teach. 2020;42(7):744–755. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2020.1768230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Simok AA, Pa MNM, Abdul AF, et al. Challenges of e-mentoring medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic. EIMJ. 2021;13(4):107–111. doi: 10.21315/eimj2021.13.4.9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Govindarajan V. Great innovators create the future, manage the present, and selectively forget the past. Harvard Business Review. uptated 2016. March 31; [cited 2021 Feb 2]. Available from: https://hbr.org/2016/03/great-innovators-create-the-future-manage-the-present-and-selectively-forget-the-past.

- [15].Heifetz RA, Linsky M. Adaptive leadership: the Heifetz collection (3 items). Harvard Business Review Press. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Soemantri D, Nurokhmanti H, Qomariyah N, et al. The practice of feedback in health professions education in the hierarchical and collectivistic culture: a scoping review. Med Sci Educ. 2022;32(5):1219–1229. doi: 10.1007/s40670-022-01597-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Felaza E, Findyartini A, Mustika R, et al. Deeper look into feedback practice in an Indonesian context: exploration of factors in undergraduate settings. Korean J Med Educ. 2023;35(3):263–273. doi: 10.3946/kjme.2023.264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Sandelowski M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res Nurs Health. 2000;23:334–340. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Otani T. ‘SCAT’ a qualitative data analysis method by four-step coding: easy startable and small scale data-applicable process of theorization. Bulletin Of The Graduate School Of Education And Human Development Nagoya University. 2008;54:27–44. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Harden RM, Lilley P. The eight roles of the medical teacher: the purpose and function of a teacher in the healthcare professions. Elsevier Health Sci. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Pusic MV, Santen SA, Dekhtyar M, et al. Learning to balance efficiency and innovation for optimal adaptive expertise. Med Teach. 2018;40(8):820–827. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2018.1485887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Mylopoulos M, Kulasegaram K, Woods NN. Developing the experts we need: fostering adaptive expertise through education. J Eval Clin Pract. 2018;24(3):674–677. doi: 10.1111/jep.12905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Mylopoulos M, Regehr G. Mylopoulos M and Regehr G.Cognitive metaphors of expertise and knowledge: prospects and limitations for medical education. Med Educ. 2007;1159–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2007.02912.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Lee IR, Kim HW, Lee Y, et al. And Smith L.Changes in undergraduate medical education due to COVID-19: a systematic review. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2021;25(12):4426–4434. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202106_26155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Shih KC, Chan JCH, Chen JY, et al. Ophthalmic clinical skills teaching in the time of COVID-19: a crisis and opportunity. Medical Education. 2020;54(7):1–2. doi: 10.1111/medu.14189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].De Ponti R, Marazzato J, Maresca AM, et al. Ferrario MM.Pre-graduation medical training including virtual reality during COVID-19 pandemic: a report on students’ perception. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):332. doi: 10.1186/s12909-020-02245-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Illanes P, Law J, Sanghvi S, et al. Coronavirus and the campus: how can US higher education organize to respond?. 2020; [cited 2021 Sept 4]. Available from: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/public-and-social-sector/our-insights/coronavirus-and-the-campus-how-can-us-higher-education-organize-to-respond#.

- [28].Anderton RS, Vitali J, Blackmore C, et al. Flexible teaching and learning modalities in undergraduate science amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Educ. 2021;5:609703. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2020.609703 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Ardekani A, Hosseini SA, Tabari P, et al. Student support systems for undergraduate medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic narrative review of the literature. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21(1):352. doi: 10.1186/s12909-021-02791-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Vagos P, Carvalhais L. Online versus classroom teaching: impact on teacher and student relationship quality and quality of life. Frontiers In Psychology. 2022;13: doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.828774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Wut T, Xu J. Person-to-person interactions in online classroom settings under the impact of COVID-19: a social presence theory perspective. Asia Pacific Educ Rev. 2021;22(3):371–383. doi: 10.1007/s12564-021-09673-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Leung HTT, Bruce H, Korszun A. To see or not to see: should medical educators require students to turn on cameras in online teaching? Med Teach. 2021;43(9):1099. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2021.1873258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Farquhar J, Kamei R, Vidyarthi A. Strategies for enhancing medical student resilience: student and faculty member perspectives. Int J Med Educ. 2018;9:1–6. doi: 10.5116/ijme.5a46.1ccc [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Xu X, Bos NA, Wu H. The relationship between medical student engagement in the provision of the school’s education programme and learning outcomes. Med Teach. 2022;44(8):900–906. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2022.2047168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Sun HL, Sun T, Sha FY, et al. The influence of teacher-student interaction on the effects of online learning: based on a serial mediating model. Frontiers In Psychology. 2022;13:779217. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.779217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Gillespie M. Student-teacher connection: a place of possibility. J Adv Nurs. 2005;52(2):211–219. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03581.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]