Abstract

With the implementation of Act on Hospice and Palliative Care and Decisions on Life-Sustaining Treatment for Patients at the End of Life, interests of the general public on self-determination right and dignified death of patients have increased markedly in Korea. However, “self-determination” on medical care is misunderstood as decision not to sustain life, and “dignified death” as terminating life before suffering from disease in terminal stage. This belief leads that physician-assisted suicide should be accommodated is being proliferated widely in the society even without accepting euthanasia. Artificially terminating the life of a human is an unethical act even though there is any rational or motivation by the person requesting euthanasia, and there is agreement thereof has been reached while there are overseas countries that allow euthanasia. Given the fact that the essence of medical care is to enable the human to live their lives in greater comfort by enhancing their health throughout their lives, physician-assisted suicide should be deemed as one of the means of euthanasia, not as a means of dignified death. Accordingly, institutional organization and improvement of the quality of hospice palliative care to assist the patients suffering from terminal stage or intractable diseases in putting their lives in order and to more comfortably accept the end of life physically, mentally, socially, psychologically and spiritually need to be implemented first to ensure their dignified death.

Keywords: Assisted suicide, Euthanasia, Hospice care

INTRODUCTION

The Act on Hospice and Palliative Care and Decisions on Life-Sustaining Treatment for Patients at the End of Life (hereinafter referred to as the Act on Decisions on Life-Sustaining Treatment) was implemented in February 2018, allowing terminally ill patients to withdraw or withhold meaningless life-sustaining medical care in accordance with their own will. In addition, even healthy individuals can express their intentions by advanced directives (ADs) in advance whether to undergo life-sustaining medical care or not without diseases [1]. This led to over-extended interpretation of the right to opt for dignified death [2], and the Act on Decisions on Life-Sustaining Treatment was even referred to as “Death with dignity Act”. Furthermore, not only the general public but also the press, mass media and some academic literatures and even public institutions are using termination of meaningless life-sustaining medical care and “Death with dignity” as synonyms [3,4]. However, in the US state of Oregon, where a “Death with Dignity Act” actually exists, the concept is not about withdrawing or withholding life-sustaining devices for death with dignity. It is used as an euphemistic expression for “physician-assisted suicide”, which allows a terminally ill patient without possibility of recovery to actively shorten his life with the assistance of physician [5]. Nonetheless, many people use “death with dignity” confusing with euthanasia or withdrawing meaningless life sustaining treatment because they believe confronting death without suffering dying process is “well-dying.” Accordingly, when patients or their family members use “death with dignity”, health care providers should understand and identify what they really want.

MAIN TEXT

1. Concepts of euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide

Euthanasia is a compound derived from the Greek words “eu” (good) and “thanatos” (death), and refers to an act of dying that is peaceful, comfortable, and painless. It is the act of intentionally shortening the life of a patient who is suffering from extreme pain, at the request of the patient or their family members [6]. The patients requesting euthanasia may believe that death would be more comfortable than sustained painful life. Although the views on the scope of euthanasia differ widely, they can be categorized into 1) withdrawal of medical intervention or medication that has no therapeutic functions, 2) assertive and direct intervention to directly induce death of patient in terminal stage, 3) withholding all medical interventions to allow or hasten death, 4) indirect consequence of palliative drug, 5) physician-assisted suicide [3]. What is common to all these concepts is that the patients requesting euthanasia are confronted with the “situation of severe suffering” in which they feel that death is better than sustaining life with suffering, which is anticipated due to aggravation of the disease in the near future.

Depending on the causal relationship of death, euthanasia can be also classified into 1) active euthanasia, which involved taking active actions such as medication injection to terminate a patient’s life, 2) passive euthanasia, which involves hastening the time of death by withdrawing the measures to sustain the patient’s life. In particular, “physician-assisted suicide” is defined as a patient dying directly through a method provided by a physician at the patient’s request [7]. Although passive euthanasia could be constructed as an artificial intervention involving “withdrawing necessary measures”, there is a misunderstanding that it is allowed by the Act on Decisions on Life-Sustaining Treatment. Here, the concept that the decision made by the patient is also misinterpreted that the patient has the right to make decision to end his own life.

2. Current status of perception of euthanasia

Health care provider, civic groups and patient groups in Korea continue to display negative attitude towards formal allowance of euthanasia although general public misunderstand that the Act on Decisions on Life-Sustaining Treatment allows passive euthanasia. Accordingly these groups are presenting the opinion that further institutional support and activation of hospice palliative care is necessary to better prepare for death with dignity rather than euthanasia to ensure “well-dying” of patients. Palliative care ordinance for wellbeing in Taiwan implemented in 2000 comprehensively deals with the scope of hospice palliative care, which is perhaps most similar to Act on Decisions on Life-Sustaining Treatment in South Korea. However, this regulation does not make distinction between terminal stage and last days of life, and they allow decisions can be made through consultation between the patient’s family and/or representative and medical staff if there is no documentary evidence that the patient personally consented to and signed for such action [8].

Some countries include 10 states in the USA, Province of Victoria in Australia, Canada and Netherlands allow euthanasia as of 2021. These countries stipulate the conditions for physician-assisted suicide as follows 1) terminal stage disease, 2) no possibility of full recovery, 3) left with unbearably pain or burdensome life as the direct consequences of the disease, 4) voluntary and continuous request for death while the patient having the ability to make judgments, 5) it is impossible to terminate life of patient without assistance. These countries stipulate conditions as safety measures to prevent abuse or misuse as follows 1) consultations and prescriptions are only available at medical institutions, 2) check whether the patient who is an adult has decision-making capability, 3) check whether it is voluntary decision made out of free will, 4) provide documented explanation and consent thereof, and the explanation must include the details of palliative care, 5) two or more medical professionals must confirm and signed and 6) provide opportunity to withdraw request for euthanasia [5].

3. Euthanasia, and its controversial ethical issues and problems

The withdrawal of meaningless treatment should not be confused with the abandonment of treatment, and is clearly different from the concept of euthanasia. The withdrawal of “meaningless” treatment is defined as stop of measures to be taken without possibility of stabilizing or improving the patient’s conditions, even more harm the patient. It is the termination of what can be deemed as obsession of treatment carrying out under the circumstances of unavoidable death. Abandonment of treatment or care refers to intentionally failling to perform balanced and appropriate actions that could prevent the progression of disease, or not taking necessary care even when death can be averted. Euthanasia, is a different concept altogether, as it intentionally causes a patient’s death at their request, and always involves artificial actions. The Act on Decisions on Life-Sustaining Treatment in Korea allows the withdrawal of “meaningless treatment” in situations where death is inevitable. This is a completely different concept from the abandonment of treatment or euthanasia. Therefore, the implementation of the Act on Decisions on Life-Sustaining Treatment should not be considered as allowing passive euthanasia.

Those who advocate euthanasia believe that it would be better to choose death over the life of living under unbearable pain or suffering because they put greater importance on the how they live, that is, value of life, than on life itself. As such, it is necessary to more closely examine what “life of suffering” that the patients and their families are referring to means. Those with incurable disease often fear the physical pain or suffering that will come as their disease progress, and they worry that they will spend the rest of their life waiting for death in distress. They may also think the high medical expenses associated with prolonged hospitalization as a significant financial economic burden on their family members even disease is not improved. These factors can make patients their remaining life meaningless, leading to consider euthanasia. Those who advocate euthanasia assert that acknowledging the right to choose death is a better means of ensuring human dignity if the terminally ill patients could degrade the dignity by continuing their lives with such suffering. However, it must be pointed out that living a suffering life itself does not degrade human dignity. Terminally ill patients may suffer from physical, psychological, and economic problems, but this does not mean they are not dignified. It is just the situations that they face that make them feel undignified. Therefore, it is important to do everything possible to solve these issues so that patients can maintain their dignity without resorting to terminating their life.

If only the value of life is emphasized rather than viewing the human life itself for dignity, there is a risk or error that euthanasia will be justified even under various situations not terminal disease, leading to the risk of loss of the dignity of life itself. There is also risk of inducing eugenic logic by applying the justification of euthanasia to terminally ill patients who cannot or do not know how to give consent although it will be carried out with the consent of the patients.

4. Rationale and ethical issues of physician-assisted suicide

Those favoring physician-assisted suicide assert that it should be considered different from homicide or euthanasia. They claim that physician-assisted suicide is not a crime it executed for the well-being of the patient under mutual consent or agreement between the patient requesting and health care provider executing the action, unlike homicide intentionally premeditated due to hatred or revengeful thoughts. However, “life” is not a subject or commodity that can be exchanged through mutual consent or agreement. Although euthanasia or physician-assisted suicide differs from criminal homicide, it is nonetheless inevitable to ultimately discern it as an act of aiding suicide. It is because the motivation that induced certain action taken, even it can play an important role in better understanding the moral responsibilities for such action, cannot change or justify the nature of the action itself. That is, even if homicide was committed out of sympathy, a homicide is nonetheless nothing more than a homicide. Physician-assisted suicide, although it is done to relieve the patient’s pain, also leads to artificial termination of life.

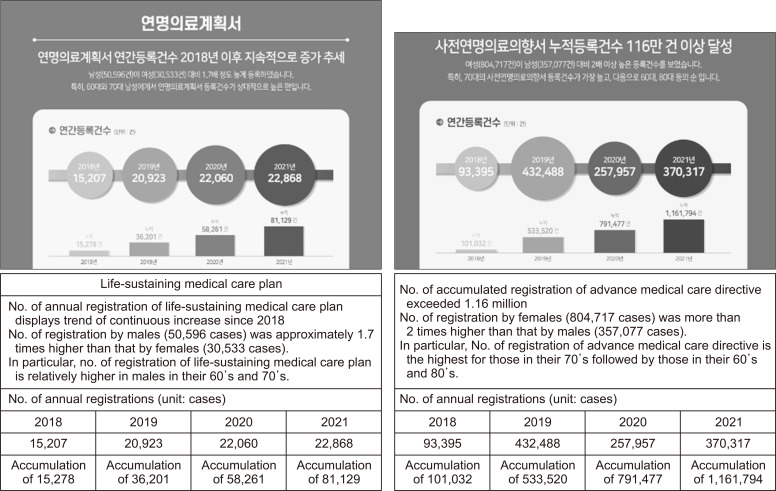

Recent public opinion polls have shown that significant proportion of the people is in favor of physician-assisted suicide [9], but it is risky to accept these results as they are based on surveys of the general public. People may have a vague fear of the pain or suffering associated with incurable or terminal diseases. The proportion of people who prepare AD in a healthy state without a real sense of the disease, is steadily increasing. However, the proportion of those preparing ‘life-sustaining treatment plan’, which discuss the withdrawal or withholding of meaningless life-sustaining treatment in real situation by patients themselves with terminal stage disease has not shown significant changes (Figure 1) [10]. That is, it is quite different of perspectives of patient currently undergoing treatment due to real illnesses from those of general public. Since the aforementioned public opinion polls on physician-assisted suicide were conducted on the general public rather than patients, such results cannot be directly applied to the conditions of terminally ill patients and their family members.

Figure 1.

Current status of life-sustaining medical care plan.

Source: Statistics 2022 [Internet]. Seoul: Korea National Institute for Bioethics Policy; 2022 [cited 2023 Apr 1]. Available from: https://www.nibp.kr.

Another basis for justifying physician-assisted suicide is a right for patient’s self-determination [11]. “Right” refers to demanding of official acknowledgement of certain things that are equality valuable for everyone [12]. For example, the values of rights such as education, caring and freedom, etc. have been acknowledged and accommodated by the constituent members of the society in order to enable people to express the capabilities of human built into the lives of human beings. Accordingly, it is possible to make specific demands to the society and its members to concede certain portions of rights and understanding for realization of such rights for everyone. That is, right is not an issue of each individual but, rather, a concept to which relational principle in the society is applied. From the perspective of the right of patient, since the patients have the right to receive care, they can request and be provided with various types of care for disease control or improving quality of health. This is also an expression of the basic right of human for life. However, death is a state in which all the possibilities for realization of values and virtues of the living state have been terminated. Even if the patient’s special conditions are considered, death itself cannot be state considering “right” because it does not do any good or benefit to society or its members. Therefore, with regard to the “right to die,” it cannot be deemed as a “right’ that can be accommodated by the society. The right to death with dignity requested in a terminal stage or during the last days of life should not be the right to have the patient die, but the right of the patient to be cared for maintain a comfortable life until the end of life [13,14].

Advocates of physician-assisted suicide assert that healthcare providers deal with life through compassion, they should also have the responsibility to manage the end of life based on medical judgments about the quality of life. They are in charge of caring at the time of birth, throughout life and till the time of death. If the disease cannot be cured, they need to assist the patient to live in greater comfort by alleviating symptoms and manifested due to diseases. At this stage, healthcare providers should care for the patient as a whole person, not merely an object of medical care, to maintain the patient’s dignity. This means healthcare providers should understand what the patient wants and what medical assistance is necessary at the end of life, taking into account the patients’ views and preferences. For terminally ill patients, health state affects their decision-making. As they approach the end of their life, it becomes challenging for them to specify their preferences, and they depend on their family members’ decisions. If a patient in his last days of life refuses certain treatment and requests death, it is more appropriate to interpret it as resignation of life rather than accommodation of death. In reality, many patients do not want to die, but want to escape from the difficult situations they face.

CONCLUSION

Physician-assisted suicide refers to assisting of inducing death at the request of a patient who fear of forthcoming sufferings. However, the act of using medical care to artificially end a life that has become as to wish for death does not preserve human dignity, rather than a kind of homicide. Health care provider should be focused on reducing patient’s suffering by alleviating symptoms so that they may live their final days as comfortable as possible. It is necessary to continually provide appropriate medical care to maintain dignified state of the patients until the last days of life rather than artificially terminating life to ensure their death with dignity. Therefore, what the society needs to do for death with dignity is to qualitative and institutional reinforcement and activate hospice palliative medical services for provision of comfortable care rather than allowing euthanasia including physician-assisted suicide.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Enforcement Decree of the Act on Hospice and Palliative Care and Decisions on Life-sustaining Treatment for Patients at the End of Life, author. Enforcement Date Feb. 4. Korea Legislation Research Institute; Sejong: 2018. c 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Na JY, Park JT. Patients' self-decision and death in court decisions and the law of decision of life-sustaining medical care. Korean J Leg Med. 2022;46:1–10. doi: 10.7580/kjlm.2022.46.1.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim CS. Euthanasia and tort liability. Korean J Civil Law. 2005;28:417–55. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim ST. Global trends in legalization of physician-assisted suicide. Korean J Medicine Law. 2018;26:27–73. doi: 10.17215/kaml.2018.06.26.1.27. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seong KS. A study on the acceptance of physician-assisted suicide. The Journal of Legal Studies. 2019;27:211–40. doi: 10.35223/GNULAW.27.4.9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jeffrey L, Shirelle P, editors. Death and dying, life and living. West Pub. Co.; Minneapolis/St. Paul, MN: c1998. West's encyclopedia of American law Volumev.4. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beauchamp TL, Childress JF. Principles of biomedical ethics. Oxford University Press; New York, N.Y.: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ha HS. Graduate School of University of Seoul; Seoul: 2020. Constitutional study on termination life-sustanining treatment : focused on right to self-determination [master's thesis] Korean. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheong KH, Kim KR, Seo JH, Yoo JE, Lee SH, Kim HJ. Research report 2018-02-01. Korean Institute for Health and Social Affairs; Sejong: 2018. Ensuring dignity in old age with improved quality of death. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Statistics 2022 [Internet] Korea National Institute for Bioethics Policy; Seoul: 2022. [cited 2023 Apr 1]. Available from: https://www.nibp.kr . [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang HC. A study on the legal policy for the permit of the physician-assisted suicide. J Law Politics Research. 2018;18:53–82. doi: 10.17926/kaolp.2018.18.4.53. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sung NI. The Law. 23rd ed. Bobmunsa; Paju: 2023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jun JY. A study on the acceptance of euthanasia. Journal Hallym Law Forum. 1995;4:113–60. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim EC, Kim TI. Right of self-decision making about death and death with dignity. Study on American Constitution. 2013;24:97–124. [Google Scholar]