Abstract

PURPOSE

Investigating transgender people’s experiences sharing health information in clinical encounters may yield insights for family medicine clinicians.

METHODS

This was a qualitative study using a community-based participatory research approach and interpretive description methodology. Seven qualitative focus groups were conducted with 30 transgender adults living in North America. We used purposive sampling to ensure diversity. The focus groups were transcribed verbatim, and 2 investigators independently reviewed and coded each transcript, then they mutually reviewed the transcripts, reconciled their coding, and summarized the codes into themes. Themes were reviewed with community members, participants, and uninvolved clinically oriented investigators for member checking and peer debriefing.

RESULTS

Four themes were noted: (1) transgender people often perceive clinicians’ questions as voyeuristic, stigmatizing, or self-protective; (2) patients describe being pathologized, denied or given substandard care, or harmed when clinicians learned they are transgender; (3) transgender people frequently choose between risking stigma when sharing information and risking ineffective clinical problem solving if clinicians do not have all the information about their medical histories; (4) improving the safety of transgender people is difficult in the context of contemporary medical systems.

CONCLUSIONS

Transgender people often must choose between stigma and potentially suboptimal care. Improvements in medical culture, policies, procedures, and data collection tools are necessary to improve the quality and safety of clinical care for transgender people. Institutional and systems changes may be required to safely and effectively implement sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI) data collection in clinical settings.

Key words: transgender persons, health communication, qualitative research

INTRODUCTION

Transgender people experience mistreatment in health care encounters that can include harassment, assault, and denial of care.1,2 Ontological oppression, or the stigma experienced by people who do not fit categorical assumptions, including those related to gender, may be one cause.3 The specific experiences of transgender people when clinicians learn they are transgender and the impact of these experiences on patients’ information sharing remain largely unexplored. Investigating these experiences is particularly timely given that national efforts are underway in the United States to implement collection of sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI) data in primary care and other settings.4-9 While these efforts are imperative to understand and eliminate health disparities for sexual and gender minority (SGM) people, the implications of gender identity disclosure for individual transgender people are largely unknown.

Family medicine clinicians are in the unique role of building close and longitudinal relationships with patients over their lifetimes and coordinating care across medical disciplines. Understanding the experiences of transgender people when their gender identities are known to clinicians and the reasons transgender people may share, modify, or withhold information could therefore yield important insights. This information may assist family medicine clinicians in advocating for patients treated by specialists or in other contexts, inform family medicine clinicians’ decisions about whether and how to discuss and document patients’ gender-related information, and suggest barriers to effective communication with transgender people and mechanisms to improve relationships and the safety of clinical encounters.

Objectives

The purpose of this study was to explore the experiences of transgender people with clinicians who know they are transgender, the deliberations that transgender people make about what information to share in clinical settings, and the recommendations of transgender people to improve the safety of data sharing and co-created knowledge production in clinical encounters.

METHODS

Design

This investigation is part of a research study regarding transgender people’s experiences receiving health care and their experiences viewing their electronic health records (EHRs) conducted between 2020 and 2021.10 The semistructured focus group guides are available in the Supplemental Appendix. We used a community-based participatory research approach, which involves key stakeholders in all aspects of the research process from study design to data interpretation and dissemination.11-13 The research team consists of academic researchers trained in qualitative methods as well as non-academically affiliated transgender community members on a community advisory board (CAB). The CAB met weekly with the investigative team to assist in all stages of the study including the development of the focus group script, recruitment of participants, and reviewing and editing drafts of the manuscript. The CAB is made up of 4 transgender people in their 20s and 30s, 3 of whom are White and one of whom is Black. Two CAB members are non-binary, one is a man, and one is a woman. The CAB members have worked with the first author (A.B.A.) on transgender health research for the last 4 years, are paid $50/meeting, and are manuscript co-authors.

The remainder of the research team is diverse in regard to gender identity (ie, some members are transgender and some are not), sexual orientation, race/ethnicity, geographical location, and professional background. Two members of the research team facilitated the focus groups: a hematologist who was a clinical fellow at the time of the study and a physician assistant who was a primary care clinician at the time of the study (A.B.A., S.J.O.). They are both transgender. To document the researchers’ stance in relation to the participants and the subject matter, both coders (A.B.A., J.E.M.) wrote reflexive notes before the start of data collection and kept an audit trail during data analysis. Peer debriefings with the co-authorship team including the CAB as well as uninvolved clinician investigators were also leveraged to enhance the validity of the findings. Each focus group participant was also offered the opportunity to review the themes and illustrative quotes for the purposes of member checking. The participants who reviewed the themes felt they were representative of the discussions in the focus groups. One participant suggested increasing quotations from transgender people of color to ensure more equal representation, and this was done as suggested.

We recruited transgender clinicians because their roles both as clinicians and transgender patients provide them with important dual perspectives. Approximately one-third of participants, including some clinicians and some nonclinicians, were known to the investigators before the study.

We used an interpretive descriptive research design,14 a theoretically flexible approach to analyzing data within medical and nursing research developed to address complex experiential questions about health and illness and produce practical solutions.15 Purposive sampling was used to increase diversity in age, race/ethnicity, and gender. Early focus groups consisted primarily of White transmasculine people so later recruitment was directed toward people of color, women, and transfeminine nonbinary people. We chose focus groups to provide participants with an opportunity to theorize collectively and generate novel insights. To increase safety and the ability of focus group members to draw on shared experiences, we also conducted 2 focus groups specifically for transgender clinicians, 1 for transgender people of color, 1 of transgender participants who had received specialty care, and 1 for transfeminine people. This decision was made because in early groups transfeminine people and people of color spoke less than other participants. Other groups had a mix of clinicians and nonclinicians of various genders, races, and ethnicities. No participants attended more than 1 group.

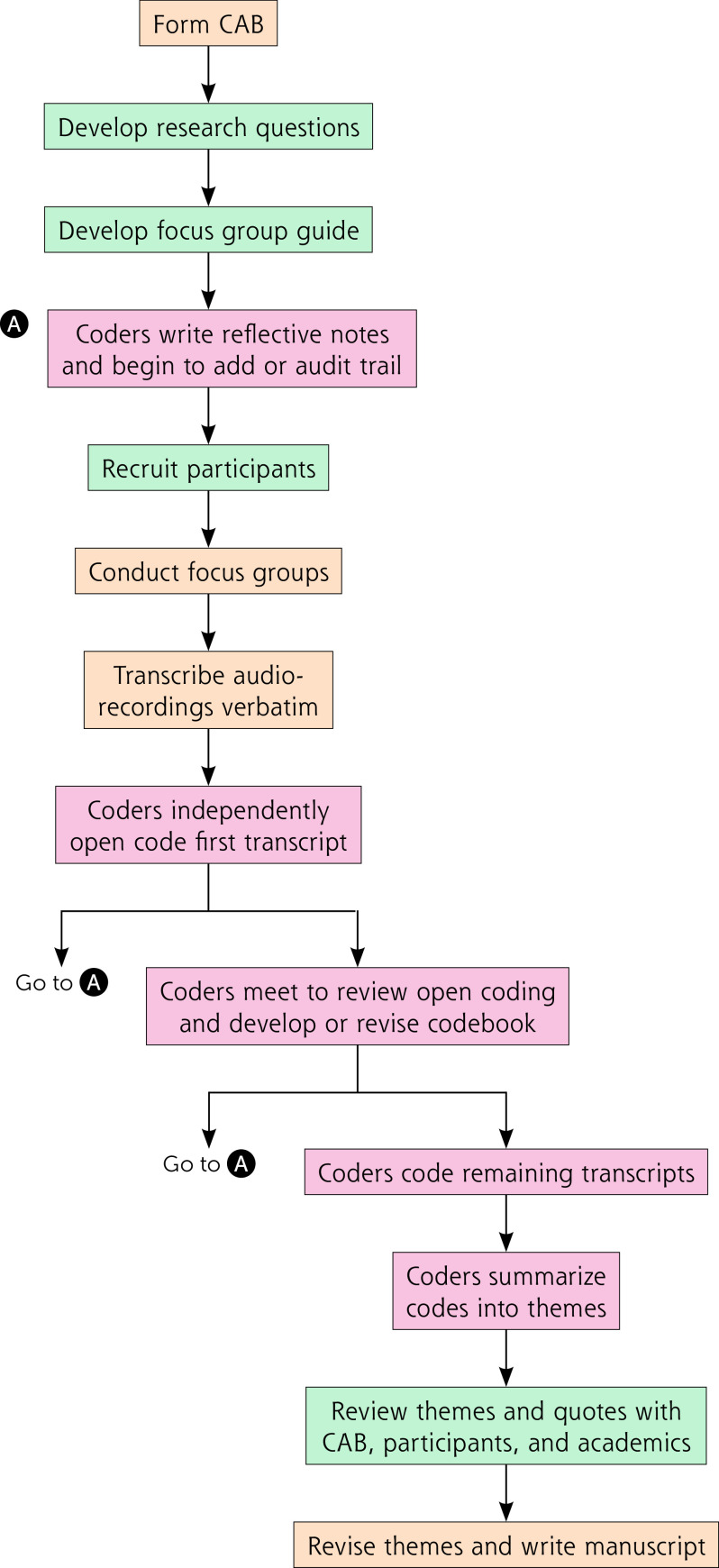

See Figure 1 for a flow diagram of our methods.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of methods.

CAB = community advisory board.

Note: Orange: Involved members of the investigative team but not the community advisory board; green: Involved the community advisory board and other members of the investigative team; red: Involved the first 2 authors only.

The University of Rochester Institutional Review Board approved and oversaw this study. Participants provided verbal rather than written consent to avoid unwanted disclosure of their identities.

Participants

Eligible participants were aged 18 years or older, transgender, North American residents, and English-speaking. We recruited participants via e-mail and social media posts on Twitter and Instagram, leveraging social networks and investigators’ professional networks to recruit clinicians who were transgender. Thirty-eight people met inclusion and purposive sampling criteria and 30 participated. The other 8 agreed to participate but did not attend focus groups.

Approach

Two researchers (A.B.A., S.J.O.) facilitated 7 online focus groups with 3 to 5 participants each lasting 60 to 90 minutes using secure video conference software16 and following a semistructured guide that included questions about experiences with health care and reading electronic health records (EHRs). Additional questions were included for focus groups with clinicians. Following focus groups, participants completed a demographics survey in REDCap (research electronic data capture).17,18 Participants received a $25 gift card.

Focus group audio recordings were transcribed verbatim and entered into Atlas.ti (Scientific Software Development GmbH).19 Two investigators (A.B.A., J.E.M.) developed a codebook by independently reviewing and open coding the first transcript and identifying key ideas, which became defined codes. They then coded the 7 focus group transcripts iteratively by independently double coding, reviewing, discussing, reconciling each coding discrepancy, and revising the codebook. Codes were summarized into themes related to the research questions. By the time we reached the last focus group, we noted that no new themes emerged. This manuscript follows the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ).20

RESULTS

The 30 participants had a median age of 31 years (range 20 to 67 years). Forty percent of the participants were people of color and 50% made less than $40,000 per year. Participants were geographically diverse, residing across the United States and 1 in Canada. The analysis resulted in 4 major themes. Demographic information included with quotes are written as provided by participants, including any shorthand, and includes race, gender, age range, and participant identification number. See Table 1 for demographics and Table 2 for quotations.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics, N = 30

| Age, y, mean (range) | 31 (20-67) |

| Clinician (%) | 10 (33) |

| Race/Ethnicity (%) | |

| Indigenous | 3 (10) |

| Black | 7 (23) |

| Asian | 2 (7) |

| White | 22 (73) |

| Latinx | 4 (13) |

| Gender | |

| Non-binary/gender fluid/genderqueer/agender | 21 (70) |

| Man | 4 (13) |

| Woman | 3 (10) |

| Does not identify with gender | 1 (3) |

| Transgender man | 1 (3) |

| Sexual orientation | |

| Queer/pansexual | 22 (73) |

| Bisexual | 6 (20) |

| Gay/lesbian | 5 (17) |

| Heterosexual | 1 (3) |

| Asexual | 3 (10) |

| Something else | 4 (13) |

| Choose not to answer | 1 (3) |

| Income, $ | |

| <20,000 | 8 (27) |

| 20,000-39,999 | 6 (20) |

| 40,000-59,999 | 3 (10) |

| 60,000-79,999 | 2 (7) |

| >80,000 | 5 (17) |

| Missing | 4 (13) |

| Insurance | |

| Private | 19 (63) |

| Public | |

| Medicaid | 6 (20) |

| Medicare | 4 (13) |

| Uninsured | 2 (7) |

| Missing | 1 (3) |

| Geographic Region | |

| Western United States | 8 (27) |

| Southwest United States | 1 (3) |

| Midwestern United States | 3 (10) |

| Southeastern United States | 3 (10) |

| Northeastern United States | 15 (50) |

| Canada | 1 (3) |

Note: Values documented at n (%) unless otherwise noted. Participants were asked to “choose all that apply.” Thus, column values may not total n = 30 nor percentages 100%.

Table 2.

Illustrative Quotes

|

Theme: Transgender people often perceive clinicians’ questions as voyeuristic, stigmatizing, or self-protective. [D]octors…ask a lot of invasive questions. I saw a pulmonologist earlier in the year and one of his first questions was, “When are you getting genital surgery?” and I was like, “I’m here for my lungs.” (White, non-binary, age 20s, #24) All [clinicians] need is what medical [interventions] you’ve had done and what your pronouns are.… [Other] shit gets documented [because] someone’s fucking curious…so people can talk behind [the patient’s] back. (Xicanx, non-binary, age 30s, #21) When they’re asking about [being transgender], they’re more like, “What was originally in your pants?”…and most of the time it’s not relevant.…[It] also just feels like they’re asking questions because they’re curious. (White, genderqueer, age 20s, #18) There’s this idea of being extra-defensive in your documentation when you’re dealing with a trans person—being really complete…in case something happens. I don’t think you need to ask extra questions. I don’t think you need to ask everything about someone’s gender journey.… Don’t ask [the questions] … you don’t need to ask because that’s a violent thing to do, and it’s not for them it’s for you. (White, nonbinary, age 30s, #28, clinician) What’s surprising for me is that my medical record…says that I have gender dysphoria and that I’m transgender…, but it doesn’t say anything about top surgery, my hysterectomy, my cancer treatments, port placement, bone marrow transplant twice, or chemotherapy. (Black, nonbinary, age 20s, #9) I was [seeking care]…because I have jaw pain and tightness…and the attending kept [misegendering me even after I corrected her] so I was like this is not [a] mistake [and then the attending]…literally started asking, “Oh, are you still on testosterone?”.I was like… why do you think my jaw pain is connected to being on testosterone? Do you ask cis men this? Probably not. (Asian, non-binary, agender, age 20s, #11) If I come to you and you’re a dentist, the only thing you need to know is how fucked up my teeth are. If I come to you and you’re a dermatologist, all you gotta look at is my acne. If you desperately need information because you need it to treat me, I need to know why you need it to treat me. (Black, doesn’t believe in gender, age 20s, #23) As soon as I walk in, no matter what I’m there for, the first thing of business is for them to determine my gender or sex assigned at birth… and…once they…know they’re …much more at ease.… (White, man, age 20s, #25) I’ve also been [referred to subspecialists], say the eye doctor, and they’re just like, “What do you use testosterone for?” and I’ve looked at them in the face and been like “testosterone things” and just left it at that. (Black, man, age 30s, #1, clinician) When we had [a] trans patient on my unit, I was reading the ER note and they made sure to mention that she was wearing a prosthesis. And I was like.… not sure why that’s relevant. Were you doing that to make a point? (White, man, non-binary, age 30s, #30, clinician) Getting my vitals taken in the room, I had to field a lot of questions every time I went about what I was. And why?…And [the clinicians did] this kind of informal [questioning],…this strange, unprofessional, “So tell me what it was that you had done” in this sort of behind-the-curtain way that I didn’t appreciate at all. (White, non-binary, age 30s, #28, clinician) I don’t want to step into a place and be the center of attention because people are looking at me like “Oh, hold on a second,” and I can tell in their eyes that they’re picturing what I looked like before my transition. And looking at my pants.…[For me the whole point of having] anything in my medical record is to get the attention and the weird questions away from me. (Black, doesn’t believe in gender, age 20s, #23) I know there’s medical reasons why they need to know that you take [for example spironolactone].… I just don’t like the conversations that just come after like…“Oh, so you’re transitioning? To female? Did you do this? Did you do this? Dah dah dah dah dah?” (Black, trans woman, age 20s, #13) |

|

Theme: Patients describe being pathologized, denied or given substandard care, or harmed when clinicians learn they are transgender. It wasn’t until after I told the doctor that I was on hormones for transition that I started being “he’d.” And as accidental or whatever it was, it was after. Before that, it was “she.” (Black, trans woman, age 20s, #13) If cis people know what I was assigned at birth, they’re always getting my pronouns wrong. It doesn’t matter how much they promise they’ll get them right; the moment they know they get it wrong. (White, trans-femme, androgyne, demigender, apogender, nonbinary, genderqueer, genderfluid, age 20s, #17) When I got to the hospital, I was…in a lot of pain and …we were trying to explain to the doctor that my appendix burst … and we got yelled at because…I was trans.…They sent me home a lot faster than they usually send people home…and prescribed Tylenol instead of actual pain killers.… I had one of the nurses that was a Black woman who was like, “I have never seen people get out of the hospital without any prescription.” And I would regularly have nurses, usually…not nurses of color, come into the room [and] at the moment they would see my legal name they would get out .… And I was constantly yelled at by people.… Now when something goes wrong I just tough it up.… (Black, doesn’t believe in gender, age 20s, #23) As soon as you tell them “[spironolactone] and estradiol,” the doctor [sometimes] knows why you’re taking them and…[says] out loud, “So you’re transitioning to female” …In front of so many people, especially in an emergency care system, having…someone say that information out loud as a trans person feels invasive to my own privacy and wellbeing. (Black, trans woman, age 20s, #13) After I had top surgery…the tech …[was] asking really inappropriate questions, asked to see my chest, and then proceeded to touch my chest without my permission. So that was probably…the worst story that I will never forget. (White, non-binary, man, age 30s, #30, clinician) [My ex-partner] was in the hospital for an alcohol overdose and everyone was gendering her correctly at first, and then…the doctor pulls up the charts …and…takes…two feet back from her hospital bed, and he’s like, “Oh, this seems to be an emotionally disturbed individual.”…The doctor was probably misgendering…saying, “He’s drunk and dangerous” and this was not the case until he [learned that she was transgender].… [The doctor] acted like my partner was kind of a wild animal from that point forward.… (White, nonbinary woman, age 30s, #14) Once they figure out I’m trans…I feel their demeanor change, their questions. They get really hesitant all of a sudden. I’ve had doctors try to make me put on gowns, and I’m like, “Oh, I don’t need to cover my chest. I’ve had surgery, and I feel comfortable with that,” and they’re like, “No, no, you have to put on the gown.” …They just get…so uncomfortable.… (White, non-binary, age 20s, #24) I had a trans patient come into the ER and I asked their pronouns and then a staff member, a [medical assistant] was like “She blah blah blah blah,” and I was like, “Actually they use they.” And the [medical assistant] was like “Okay, well ‘it’ whatever.” And I was just like, “That’s not appropriate. That’s not funny.” How can you serve a patient if you also call them “it,” if you dehumanize them like that? (Latino, Taíno, trans man, age 30s, #2, clinician) |

|

Theme: Transgender people frequently choose between risking harms associated with transphobia if they share information and ineffective clinical problem-solving if they do not. Do I need to tell all these [clinicians that] much like many other women, I have estrogen coursing through my veins? (White, nonbinary, woman, age 30s, #14) I don’t feel comfortable sharing medical records with physicians anyway because it’s a guarantee that I’m not gonna get services. So I lost [my medical records] and they’re good wherever they are now, far away from me. (Black, doesn’t believe in gender, age 20s, #23) I relate to [what participant 23 said] so hard. That’s why I purposefully do not tell people shit unless they really need to know, …because it will guarantee that I don’t get services. Especially being intersex or if someone knows I’m on hormones then I’ve been denied care a lot for that.… (Xicanx, non-binary, age 20s, #21) We have to…say certain things in order to be treated certain ways… When I went into therapy for my surgeries and things…if I hadn’t gone in there and said “Oh yeah, I want to [have genital surgery], I need this,” I wouldn’t have been able to get [any gender-affirming care]. (Black, trans woman, age 20s, #13) I didn’t really know whether it would be a problem to be a little more ambivalent…to express any non-binary tendency, [to say] these parts of transition are great and these parts of transition I’m less certain about… so I was like, “Oh yeah. I’m a woman. I want all the cis things. Do my hair and my make-up. Let’s go.” (White, non-binary, woman, age 30s, #14) Because I spent so many years getting gendered with the wrong…pronouns. …Sometimes they just straight up assume I have a period… and I just go with it, which is.… not great but it works out for me. (White, trans-femme, androgyne, demigender, apogener, nonbinary, genderqueer, genderfluid, age 20s, #17) I sometimes don’t come out to my providers as trans, in part because once I told a provider I was queer and they commented, “Your underwear doesn’t look queer.” [I] was like, “Okay, I’m just not gonna mention this to people.” (White, Latine, non-binary, age 30s, #4, clinician) I’ve talked to a number of trans people who… want to make [themselves] less controversial… so that… [they] can get what [they] need. In a lot of areas you do know better what you need than honestly the provider. But in some cases you may not.…I think that’s a danger.…You might not get the care that you need… [or] you incur violence as a trans person for having [documentation about being transgender] on your record, truthfully. (White, non-binary, age 30s, #28, clinician) I don’t want [autism] on my medical record because then I know people that would be like, “Oh, that’s why you’re trans.” (Black, doesn’t believe in gender, age 20s, #23) I did have painful periods and…also my period [was] a disembodied experience because it was just so not me. But I was scared to bring that up with my doctor as a reason [for the hysterectomy]. …She’s a great doc but rolls her eyes around certain things, so…I am glad I didn’t bring that up as a reason. I’m glad we took it out, and she saved my life because she found this tumor and pulled it out, but I didn’t feel comfortable sharing that part. (White, nonbinary, age 50s, #3) I was nervous to put my sex at birth [in MyChart] because I was afraid…from then on, does anyone that opens my chart see my sex at birth? What if I don’t want them to see that? If I don’t put trans male as my identity, if I just put male, and I don’t put my sex at birth then what is seen? What is seen by insurance? I don’t want to put too much information because I don’t know who’s seeing it, and I don’t know how it’s going to affect my health insurance. I don’t know if I need to get a pap what is gonna happen. (White, nonbinary, man, age 30s, #30, clinician) |

|

Theme: Improving the safety of transgender people is difficult in the context of contemporary medical systems. There’s no lack of education…at institutions that put in a lot of work and money into diversity and inclusion efforts.…There’s just this disconnect between the resources and knowledge and the implementation. (Black, man, age 30s, #1, clinician) After 15 years of doing this kind of work …My first thought is, will we ever be able to truly take care of any person in the health care system that we have…in a way that’s not violent? (White, nonbinary, trans, age 40s, #7, clinician) The Western health care system [is] looking at people like bodies without souls attached to them.…Trans people…and people of color will never be treated properly in that system until that system is completely revised because that system was built with the idea in mind that those bodies are disposable.… (Black, doesn’t believe in gender, age 20s, #23) I’m a nonbinary person, though I am assigned female at birth, however I don’t identify or relate to the frame FTM. When I said that, the only explanation I got was the only options [for gender in the EHR] were FTM or MTF.… (Black, nonbinary, age 20s, #9) Don’t have male, female, and then other [in the EHR] .…[Include] nonbinary and/or the ability … to type in what is reflective of this person. (Indigenous, nádleehi, Black, Latinx, White, nonbinary, age 20s, #22) At some point [my psychiatrist] did fill out a form which presumably [only] had female or male as [gender] options, [and] she said, “So it’s fine if I just put you as female, right?” And I was just thinking why wouldn’t you at least ask me? It’s really dysphoric for me to be seen as female. (Asian, nonbinary, 24, #10) I got my wisdom teeth out, and I have a hormonal [intrauterine device], and I’m also on testosterone, and I remember the person at the front desk the morning of the surgery was giving me some forms and she crossed something out on one of the forms.… I looked at [what she’d crossed out] and it said something [like] …you need to tell us if you are on birth control because it mixes with the…anesthesia…Maybe if [she] didn’t assume that I was male then I could have just self-written in that yes, I’m on birth control. (Asian, nonbinary, agender, age 20s, #11) [Trans people force clinicians to] face the reality … that they’ve stuffed a lot of people into [their] algorithms [who] don’t fit, and…that [clinicians’] binary, racist algorithm[s] …[don’t] function. (White, nonbinary, 30s, #28, clinician) Something that could go a long way—I know it’s half [because of] insurance companies and stuff—[is] stop making trans people prove that they’re trans. That would be awesome. (White, nonbinary, agender, age 20s, #8) I’ve been struggling a lot with this idea of punitive [solutions].… [In] my clinic I’ve been misgendered for the 4 years that I work there. By staff. So what do we do here? What are we to do in terms of enforcing somehow that trans people are well taken care of? (White, nonbinary, trans, age 40s, #7, clinician) [Obstetrics and gynecology is] very gendered; it’s very binary. There’s a lot of work that needs to be done. Even from the moment someone’s born [everyone is] like, “Is it a girl or a boy?” [In the obstetrics and gynecology notes,] they just skip the patient’s gender or sex because the assumption is that the person they’re seeing is a woman. (Black, nonbinary, age 20s, #6) |

Theme 1. Transgender People Often Perceive Clinicians’ Questions as Voyeuristic, Stigmatizing, or Self-Protective

Participants described feeling that clinicians often ask irrelevant questions that reinforce hierarchal power differentials, titillate clinicians, or defend against liability. Thus, participants found it difficult to assess the medical relevance of specific questions which led participants to feel confusion, anger, and a need to protect themselves. In a conversation engaged in by many of the participants in a focus group specifically for transgender people of color, participants discussed motivations for clinicians’ questions. For example, one Asian, nonbinary, agender participant in their 20s (#11) relayed a story in which a clinician misgendered them repeatedly even after being corrected and then asked irrelevant questions about testosterone therapy, seemingly to stigmatize the patient. A Xicanx (a gender-neutral term referring to people of Mexican descent in the United States with -x suffix replacing -o/-a to reference connections with indigenous identity and to counter colonization),21-23 nonbinary participant in their 30s (#21) implied that clinicians’ questions are motivated by voyeurism. In the context of this conversation, a Black participant in their 20s who does not believe in gender (#23) suggested that clinicians explain the relevance of their questions.

In a focus group with clinicians and nonclinicians, participants described encountering questions that seemed unnecessarily detailed and intended only to protect against clinician liability. These participants urged clinicians to avoid asking irrelevant questions that are not for the benefit of the patient.

Theme 2. Patients Describe Being Pathologized, Denied or Given Substandard Care, or Harmed When Clinicians Learned They are Transgender

Multiple participants described medical encounters that worsened when clinicians found out that they were transgender. For example, they described clinicians using stigmatizing language (eg, referring to patients as “it”), misgendering them (ie, using the wrong name, pronoun, or gender label), providing worse care, or, in one case, performing a nonconsensual exam. One participant (#23) who had presented to the emergency department with a ruptured appendix noted a lack of attention by health care workers and early discharge without adequate pain management due to the intersections of racism and transphobia. A White, nonbinary woman in her 30s (#14) witnessed a clinician misgendering her partner and labeling her as “dangerous” and “emotionally disturbed” after realizing her partner was transgender. A participant (#13) described clinicians noting hormone therapy on her medication list and subsequently using the wrong pronouns for her and making statements that revealed her gender identity to other patients and staff.

Theme 3. Transgender People Frequently Choose Between Risking Harms Associated With Transphobia if They Share Information and Ineffective Clinical Problem-Solving if They Do Not

Given participants’ experiences with transphobia, intersectional stigma, and increased barriers to health care, many participants described reticence about sharing information related to being transgender and some withheld such information to avoid harassment and barriers to care. Participants also described avoiding sharing information about other stigmatized experiences, such as autism or substance use, to avoid intersectional transphobia. Participants sometimes gave incorrect information about their identities or preferences to fit into clinicians’ categorical expectations of transgender people; for example, that only people with a binary gender identity who desire genital surgery are legitimately transgender. Participants worried that they would not receive gender-related care if they did not fit these expectations.

Participants also described difficulties understanding when it might be relevant enough to share medical information that revealing themselves as transgender to clinicians would be worthwhile despite the risks. A White, nonbinary clinician (#28) in their 30s described their concerns about patients choosing between the dangers of being known to clinicians as transgender and the dangers associated with clinicians not having information that may be necessary to provide quality care.

Theme 4. Improving the Safety of Transgender People is Difficult in the Context of Contemporary Medical Systems

Many participants described medical culture as inherently violent or stigmatizing of transgender people and expressed concerns that transgender people and people of color will not be safe getting health care until the system is changed. Although some participants suggested education or changes to electronic health records as a means of improving the safety of clinical encounters for transgender people, many other participants expressed concerns that these changes would be insufficient. One Black man who is a clinician in his 30s (#1) explained that despite training, many clinicians do not implement practice changes. A White, nonbinary clinician in their 40s (#7) expressed concerns that clinicians would never be able to take care of people in our current health care system in a way that is not violent. Another participant (#23) described the objectification of bodies in Western medicine, explaining that in a medical system which views bodies as disposable objects, marginalized people will never be able to receive quality care.

Other participants described limitations of the EHR and other data collection forms, which reinforce ontological oppression and preclude accurate collection and display of gender, pronouns, or name, forcing patients to inappropriately characterize themselves. An Indigenous, Black, Latinx, White, nádleehi, nonbinary clinician in their 20s (#22) suggested ensuring that EHRs have the option to enter via free text a gender that is most reflective of the patient. A participant (#28) framed the contradictions transgender people pose to medical algorithms as an opportunity to identify the limitations of medical systems and change them to improve care.

DISCUSSION

Participants described multiple forms of ontological oppression including fielding voyeuristic, intrusive questions from clinicians, which were often irrelevant to their medical care, experiencing harms when clinicians learned they were transgender, and being put in a position to choose between the harms associated with transphobia and the harms of clinicians making medical decisions with limited information. For example, if clinicians lack information about anatomy or medications, their differential diagnoses could be limited and medication interactions not considered. Participants also described the ways in which categorical understandings of bodies and disease in medicine are contradicted by transgender people,24 and clinicians thus use information gathering and documentation to stigmatize or pathologize patients. Given power imbalances between patients and physicians, patients may be compelled to answer clinicians’ questions with the assumption that these questions are being asked for patients’ benefit. When this is not the case, trust is eroded, and patients are often unable to decipher when it is safe to answer clinicians’ questions.

Prior studies have demonstrated that transgender people face harassment and assault in clinical settings.1,25 Our study generates hypotheses that situate these experiences in the context of medical assumptions that oppress transgender people and put them in a difficult situation in which they are forced between harms associated with stigma and harms associated with poor care. Prior literature suggests that withholding information from clinicians is common, and our study suggests specific experiences with clinicians in the context of ontological oppression create barriers to information sharing for transgender people.26 If medical ontologies and related discourse were to shift—for example by distinguishing concepts of gender and biologic factors such as anatomy, karyotype, and hormonal milieu—transgender people might not be seen by clinicians as abnormal or pathologic and the impetus for stigmatizing patients might cease.24,27

Short-term and long-term steps toward reducing ontological oppression and its sequelae can be leveraged by family medicine clinicians to improve the safety of clinical encounters for transgender people. Family medicine clinicians can (1) ensure their questions are medically relevant and explain their medical relevance to patients, (2) avoid putting information in patients’ EHR that may be used to stigmatize them, (3) advocate for patients who are stigmatized by other clinicians, and (4) shift medical culture by ensuring formal curriculum, guidelines, and patient-facing forms and documents be inclusive of transgender people. In the context of the national conversation in the United States regarding SOGI data collection, our findings also suggest a need to proceed with caution, given that information gathering regarding gender identity and sex assigned at birth may be accompanied by privacy breaches, harassment, poorer care, or nonconsensual exams.

Our study has a number of strengths including community-based participatory research, which allowed us to conduct research responsive to community concerns, recruit a diverse group of participants, and ensure that our findings are written in a community-centered manner.13 Interpretive description allowed us to focus on findings relevant to medical settings and to generate clinically oriented solutions.28 Focus groups allowed participants the opportunity to theorize together based on shared experiences. Limitations of our study include that focus groups do not allow for deep investigation of individual experiences or observation of interactions in clinical settings. Additionally, focus group facilitators were clinicians, which may have prevented participants from speaking as openly.

Future studies investigating multilevel interventions to increase the safety of transgender people are warranted. In the interim, based on our findings, we recommend asking only clinically relevant, patient-centered questions about transgender and other stigmatized identities; explaining the clinical relevance of questions; and ensuring documents, discourse, and policies and procedures disentangle gender and biologic factors. These steps may avoid reinforcing assumptions that render invisible or pathologic transgender people.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: authors report none.

Funding support: This work was funded by Conquer Cancer, The ASCO Foundation who played no role in the conduct of research, data analysis or interpretation, manuscript preparation or author order.

REFERENCES

- 1.Grant JMML, Tanis J, Harrison J, Herman JL, Keisling M.. Injustice at Every Turn: A Report of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey. National Center for Transgender Equality & National Gay and Lesbian Task Force; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alpert AB.CichoskiKelly EM, Fox AD.. What lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and intersex patients say doctors should know and do: a qualitative study. J Homosex. 2017; 64(10): 1368-1389. 10.1080/00918369.2017.1321376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dembroff R. Real talk on the metaphysics of gender. Philosophical Topics. 2018; 46(2): 21-50. [Google Scholar]

- 4.AMA Adopts New Policies at 2018 Interim Meeting [news release]. American Medical Association; November 13, 2018. https://www.ama-assn.org/press-center/press-releases/ama-adopts-new-policies-2018-interim-meeting [Google Scholar]

- 5.Institute of Medicine . Collecting Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Data in Electronic Health Records: Workshop Summary. National Academies Press; 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Health Issues and Research Gaps and Opportunities . The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People: Building a Foundation for a Better Understanding. National Academies Press; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grasso C, McDowell MJ, Goldhammer H, Keuroghlian AS.. Planning and implementing sexual orientation and gender identity data collection in electronic health records. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2018; 26(1): 66-70. 10.1093/jamia/ocy137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deutsch MB, Green J, Keatley J, et al. . Electronic medical records and the transgender patient: recommendations from the World Professional Association for Transgender Health EMR Working Group. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2013; 20(4): 700-703. 10.1136/amiajnl-2012-001472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Badgett MVL, Baker KE, Conron KJ, et al. . Best Practices for Asking Questions to Identify Transgender and Other Gender Minority Respondents on Population-Based Surveys. The Williams Institute; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alpert AMJ, Orta SJ, Redwood E, et al. . Experiences of transgender people reviewing their electronic health records: Insights to avoid harm and improve patient-clinician relationships, a qualitative study. J Gen Intern Med. 2023; 38(4): 970-977. 10.1007/s11606-022-07671-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB.. Community-based participatory research: policy recommendations for promoting a partnership approach in health research. Educ Health (Abingdon). 2001; 14(2): 182-197. 10.1080/13576280110051055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Izumi BT, Schulz AJ, Israel BA, et al. . The one-pager: a practical policy advocacy tool for translating community-based participatory research into action. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2010; 4(2): 141-147. 10.1353/cpr.0.0114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Minkler M. Community-based research partnerships: challenges and opportunities. J Urban Health. 2005; 82(2)(Suppl 2): ii3-ii12. 10.1093/jurban/jti034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thorne S, Kirkham SR, MacDonald-Emes J.. Interpretive description: a noncategorical qualitative alternative for developing nursing knowledge. Res Nurs Health. 1997; 20(2): 169-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thompson Burdine J, Thorne S, Sandhu G.. Interpretive description: a flexible qualitative methodology for medical education research. Med Educ. 2021; 55(3): 336-343. 10.1111/medu.14380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Archibald MM, Ambagtsheer RC, Casey MG, Lawless M.. Using Zoom videoconferencing for qualitative data collection: perceptions and experiences of researchers and participants. Int J Qual Methods. 2019; 18: 1609406919874596. 10.1177/1609406919874 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harris PA, Thielke RTR, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG.. Research electronic data capture (REDCap) – a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009; 42(2): 377-381. 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harris PA RT.Minor BL, Elliott V, Fernandez M, O’Neal L, McLeod L, Delacqua G, Delacqua F, Kirby J, Duda SN. The REDCap consortium: building an international community of software partners. J Biomed Inform. 2019; 95: 103208. 10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fries S. Qualitative Data Analysis with ATLAS.ti. Sage; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J.. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007; 19(6): 349-357. 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luna J, Estrada GS.. “Trans*lating the genderqueer -X through Caxcan, Nahua, and Xicanx Indígena knowledge”. In Aldama, Arturo J.; Luis Aldama, Frederick (eds.). Decolonizing Latinx Masculinities. University of Arizona Press. 2020;251–268. ISBN 9780816541836. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Medina L, Gonzales M.. Voices from the Ancestors: Xicanx and Latinx Spiritual Expressions and Healing Practices. University of Arizona Press. 2019;3–4. [Google Scholar]

- 23.“From Chicano to Xicanx: A brief history of a political and cultural identity”. The Daily Dot. 23 Oct 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dembroff R. Articles and essays [website]. Accessed Jul 19, 2023. https://www.robindembroff.com/articles-and-essays.html

- 25.James SE, Herman JL, Rankin S, Keisling M, Mottet L, Anafi M.. The Report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey. National Center for Transgender Equality; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levy AG, Scherer AM, Zikmund-Fisher BJ, Larkin K, Barnes GD, Fagerlin A.. Prevalence of and factors associated with patient nondisclosure of medically relevant information to clinicians. JAMA Netw Open. 2018; 1(7): e185293-e185293. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.5293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Poteat T, German D, Kerrigan D.. Managing uncertainty: a grounded theory of stigma in transgender health care encounters. Soc Sci Med. 1982; 2013(84): 22-29. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.02.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thorne S, Kirkham SR, MacDonald-Emes J.. Interpretive description: a noncategorical qualitative alternative for developing nursing knowledge. Res Nurs Health. 1997; 20(2): 169-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.