Abstract

Introduction:

Sexual risk behaviors are a public health concern. Although sexual risk behaviors are overrepresented among economically disadvantaged individuals, the mechanisms underlying the link from economic deprivation to sexual risk behaviors are not well understood.

Aim:

The purpose of this study was to investigate whether one of the earliest indicators of sexual risk, age of sexual initiation, mediates the link between young men’s perceptions of economic deprivation while growing up and sexual risk behaviors in adulthood.

Method:

Six-hundred twenty-four men provided data on background variables and risk. Path analyses were conducted in Mplus Version 8.

Results:

Perceptions of economic deprivation while growing up were related to younger age of sexual initiation, which in turn was related to higher risk for sex earlier in a relationship, condomless sex, STIs, unintended pregnancy, and condom use resistance.

Conclusion:

These findings highlight important avenues for sexual health and health equity promotion.

Keywords: Economic deprivation, path analysis, sexual behavior, sexual health

Introduction

Sexual risk behaviors represent a significant public health concern.1 Estimates show that nearly 20 million new Sexually Transmitted Infections (STIs) occur each year in the United States2 and almost 50% of pregnancies are unintended.3 Although sexual risk behaviors tend to be overrepresented among individuals with greater economic deprivation, the mechanisms underlying this association are not well understood.4 Thus, the purpose of this study is to investigate the link between young men’s perceptions of economic deprivation while growing up and sexual risk behaviors in adulthood and examine whether one of the earliest indicators of sexual risk, age of sexual initiation, mediates this relationship.

According to ecological systems theory, individuals are embedded in multiple layers of their environment, ranging from micro- (e.g., family) to macro-level (e.g., culture) contexts.5 In line with this perspective, surrounding contextual factors that determine family-of-origin economic status greatly impact human development and behavior; while economically secure environments offer access to resources and support, such as healthcare and education, economically insecure environments may lack such access, thereby increasing individuals’ risk for a variety of harmful life outcomes.6 Although some studies support an association between objective measures of economic deprivation (e.g., family income) and sexual risk behaviors, others do not, hinting at the conclusion that objective measures of economic deprivation, which lack understanding of how individuals subjectively interpret their circumstances, do not fully explain the economic deprivation-to-sexual risk behaviors link.4 Subjective perceptions of economic deprivation, which tap into individuals’ comparisons between themselves and better-off others,7 yield reliably larger effect sizes than objective economic deprivation measures in predicting a vast range of psychological and behavioral outcomes.8 Thus, the present study tests whether subjective perceptions of economic deprivation hold similar predictive power in the domain of sexual health research.

We examine the effect of subjective perceptions of economic deprivation while growing up on sexual risk behaviors in early adulthood, including having sex earlier in a relationship, condomless sex, STIs, unintended pregnancy, and condom use resistance (CUR), a form of sexual violence that consists of a variety of coercive and non-coercive tactics used to actively avoid condoms with sex partners who want to use them.9 To further understanding of the mechanisms underlying the economic deprivation-to-sexual risk behaviors link, we test whether age of sexual initiation, an early indicator that has been linked to sexual risk behaviors later in life,10,11 mediates this relationship.

We situate our study within a sample of 624 male young men, which offers a particularly suitable sample for the study of sexual risk behaviors due to the high prevalence of these behaviors in this population.12 We hypothesize that higher perceptions of economic deprivation in men’s family of origin will indirectly increase sexual risk behaviors in adulthood, via younger age of sexual initiation. Understanding the sequential events that increase risk for sexual risk behaviors is crucial from an intervention standpoint so that such factors can be targeted in early prevention programs for individuals growing up with fewer economic resources.

Method

Participants and Procedures

The current study was part of a larger data collection examining male–female social interactions among 626 young male adults in the Northwestern United States. Men came to the laboratory and, after providing written consent, completed a battery of measures. Men were compensated $15 per hour. All study procedures were approved by the University’s Human Subjects Division. The current study focuses on the 624 men (Mage = 24.58, SD = 2.73) who provided data on the measures of interest. Most men identified as White (67.8%), followed by Multi-Racial (12.8%), Black/African American (8.7%), and Asian/Asian Pacific Islander (7.1%), and other (3.6%). About half of the men in this sample (50.2%) reported an annual household income below $20,999; 30.2% reported they were students; and 49.7% reported they were currently employed. For additional information on procedures of the larger project, please refer to.13

Measures

Predictor.

Subjective perceptions of economic deprivation were measured using the item, “While you were growing up, compared to your peers, how would you rate your family’s overall financial well-being?” Higher scores indicated higher levels of deprivation with response options including 1 (well-off), 2 (above average), 3 (average), 4 (below average), and 5 (poor).

Mediator.

Age of sexual initiation was measured using the item, “How old were you when you first had consensual sexual intercourse (the age you chose to become sexually active)?” Higher scores indicated older age.

Outcomes.

Sex on the first date was measured using the item “How many times have you had sex with someone on the first date or someone whom you have known for less than 24 hours?”, with higher scores indicating higher number of first date sex. Condom use during sex was measured using the item, “Of the times you had vaginal intercourse in the past 3 months, about how often did you use a condom?”, with higher scores (in percentages) indicating higher condom use. STI diagnosis was measured using the item, “Have you ever been diagnosed with a sexually transmitted disease?”, with response options being 0 (no) and 1 (yes). Unintended pregnancy was measured using the item, “To your knowledge, have you ever gotten a woman pregnant when you did not plan to and/or did not want to?”, with response options being 0 (no) and 1 (yes). CUR was measured using the 32-item (α = .94) Condom Use Resistance Survey9 that asked participants to report on the number of times since the age of 14 they had successfully resisted using a condom with a woman who wanted to use one. Responses were summed, with higher scores indicating more frequent CUR.

Data Analytic Approach

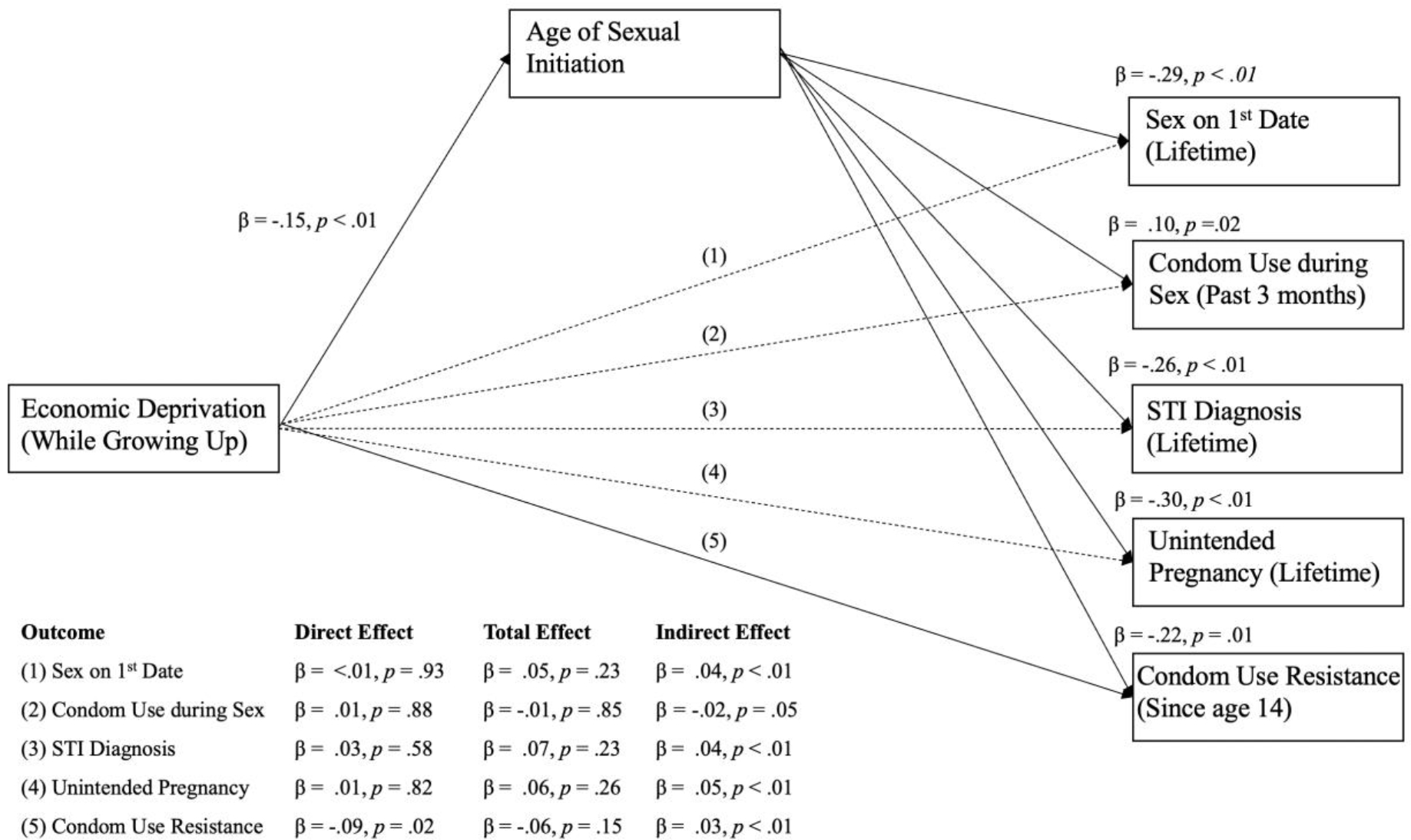

Path Analysis in Mplus Version 8.7 was used. Our model included perceptions of economic deprivation as the predictor, age of sexual initiation as the mediator, and the five sexual risk behaviors as outcomes (see Figure 1). Direct paths and indirect paths via age of sexual initiation were tested from perceptions of economic deprivation to the five sexual risk behaviors. Participants’ current age was controlled for outcomes assessing lifetime prevalence.

Figure 1.

Mediation Effects from Subjective Perceptions of Economic Deprivation to Sexual Risk Behaviors via Age of Sexual Initiation.

Abbreviations. STI = Sexually Transmitted Infections.

Standardized coefficients are reported. Model fit: AIC = 18,566.45, BIC = 18,672.92.

Results

Most men described their economic standing compared to their peers while growing up as average (48.9%), followed by above average (21.5%), below average (17.6%), poor (6.6%), and well-off (5.4%). On average, men reported that they initiated sexual intercourse at age 16.53 (SD = 2.42), had sex on a first date an average number of 5.21 (SD = 8.48) times, and used a condom during 46.2% (SD = 39.0%) of vaginal intercourse events during the past three months. Additionally, 16.9% of men had ever been diagnosed with an STI and 27.8% of men had ever unintentionally gotten a woman pregnant. Mean CUR was 46.69 (SD = 72.16).

Mediation Model

Figure 1 shows standardized estimates and significance values for the mediation path analysis. Higher perceptions of economic deprivation while growing up were indirectly related to higher number of times men had sex on a first date, lower percentage of condom use during sex (marginally significant), higher likelihood of a lifetime STI diagnosis, higher likelihood of a lifetime unintended pregnancy, and greater CUR, via younger age at first sexual intercourse. Direct effects from perceptions of economic deprivation to sexual risk behaviors, except for CUR, were not statistically significant.

Discussion

The current study aimed to examine whether men’s subjective perceptions of economic deprivation while growing up are directly and indirectly associated with sexual risk behaviors in adulthood, via initiation of sexual activity at an earlier age. Supporting our hypothesis, results showed that men who experienced higher perceptions of economic deprivation during childhood started having sex at an earlier age, which in turn was related to higher risk for engaging in sex on a first date, condomless sex, STIs, unintended pregnancy, and strategies to resist using a condom. These findings provide support for the usefulness of subjective measures of economic deprivation7 for assessing outcomes related to sexual risk and highlight age of sexual initiation as a potential mechanism explaining the route by which youth economic deprivation increases risk for adult sexual risk behaviors.

The current results should be interpreted in light of some limitations. Most importantly, although the temporal order of economic deprivation, age at sexual initiation, and sexual risk behaviors can be assumed based on the way questions were worded, it should be noted that all questions were assessed cross-sectionally, which may have led to retrospective and recall bias. Self-report data, especially reports of sexual activity, might be prone to further bias and some men may have misrepresented the amount and types of sexual activities they engaged in, along with associated experiences. Additionally, it remains unclear whether our results would generalize to other populations, such as individuals in committed partnerships, women, teenagers or older adults, and individuals of greater diversity with regards to race and sexual orientation.

Future research could benefit from addressing the aforementioned limitations. Additionally, future studies specifically targeting individuals or couples from economically deprived environments may be useful. Although the income reported in our sample was relatively low, most participants endorsed average economic status during childhood. Tapping into a broader range of economic deprivation may provide a more nuanced understanding of the ways in which economic variables affect sexual risk behaviors. Furthermore, research that clearly delineates the temporal order of sexual risk events is needed. Specifically, it is likely that sexual risk behaviors such as condom use avoidance and resistance precede STI contraction and unintended pregnancy. Given the cross-sectional assessment of these variables in our study, we were unable to tease apart the sequence of these paths.

Conclusions

This study indicates that subjective perceptions of economic deprivation are associated with earlier sexual initiation, which increases sexual health risks, including sex on a first date, condomless sex, STIs, unintended pregnancy, and CUR. We hope that our work will provide a strong basis for motivating future, longitudinal research that will build on our research questions. Our findings provide support for social justice initiatives specifically targeting disparities to promote sexual health among individuals from disadvantaged backgrounds. As such, resources and support, such as healthcare and education, may greatly benefit children, adults, and families vulnerable to sexual risk behaviors.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism [2R37AA025212; R01AA017608].

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The Authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Davis KC, Neilson EC, Wegner R, Stappenbeck CA, George WH, Norris J. Women’s sexual violence victimization and sexual health: Implications for risk reduction. In Orchowski LM, Gidycz C, eds. Sexual Assault Risk Reduction: Theory, Research and Practice. Elsevier; 2018:379–406. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Reported STDs in the United States: 2014 national data for chlamydia, gonorrhea, and syphilis. Accessed February 25, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats14/std-trends-508.pdf.

- 3.Finer LB, Zolna MR. Declines in unintended pregnancy in the United States, 2008–2011. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:843–852. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1506575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Santelli JS, Lowry R, Brener ND, Robin L. The association of sexual behaviors with socioeconomic status, family structure and race/ethnicity among US adolescents. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(10):1582–1588. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.90.10.1582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bronfenbrenner U. A future perspective (1979). Bronfenbrenner U, ed. Sage Publications Ltd, Thousand Oaks, CA; 2005:50–59, Chapter xxix, 306 Pages. http://login.ezproxy1.lib.asu.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/books/future-perspective-1979/docview/620598423/se-2?accountid=4485. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gilman SE., Kawachi I, Fitzmaurice GM, Buka SL. Socioeconomic status in childhood and the lifetime risk of major depression. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2002;31:359–367. doi: 10.1093/ije/31.2.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith HJ, Huo YJ. Relative deprivation: How subjective experiences of inequality influence social behavior and health. Policy Insights Behav. Brain Sci. 2014;1:231–238. doi: 10.1177/2372732214550165. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith HJ, Pettigrew TF, Pippin GM, Bialosiewicz S. Relative deprivation: A theoretical and meta-analytic review. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2012;16(3):203–232. doi: 10.1177/1088868311430825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davis KC, Stappenbeck CA, Norris J, et al. Young men’s condom use resistance tactics: A latent profile analysis. J Sex Res. 2014;51(4):454–465. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2013.776660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coker AL, Richter DL, Valois RF, McKeown RE, Garrison CZ, Vincent ML. Correlates and consequences of early initiation of sexual intercourse. J Sch Health, 1994; 64(9):372–377. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.1994.tb06208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaestle CE, Halpern CT, Miller WC, Ford CA. Young age at first sexual intercourse and sexually transmitted infections in adolescents and young adults. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2005;161(8):774–780. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dariotis JK, Sonenstein FL, Gates GJ, et al. Changes in sexual risk behavior as young men transition to adulthood. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2008;40(4):218–225. doi: 10.1363/4021808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davis KC, Masters NT, Casey E, Kajumulo KF, Norris J, George WH. How childhood maltreatment profiles of male victims predict adult perpetration and psychosocial functioning. J Interpers Violence. 2008;33(6):915–937. doi: 10.1177/0886260515613345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]