Abstract

Non-invasive quantification of the extracellular volume (ECV) is a method for the evaluation of focal and diffuse myocardial fibrosis, potentially obviating the need for invasive endomyocardial biopsy. While ECV quantification with cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (ECVMRI) is already an established method, ECV quantification with CT (ECVCT) is an attractive alternative to ECVMRI, similarly using the properties of extracellular contrast media for ECV calculation. In contrast to ECVMRI, ECVCT provides a more widely available, cheaper and faster tool for ECV quantification and allows for ECV calculation also in patients with contraindications for MRI. Many studies have already shown a high correlation between ECVCT and ECVMRI and accumulating evidence suggests a prognostic value of ECVCT quantification in various cardiovascular diseases. Adding a late enhancement scan (for dual energy acquisitions) or a non-enhanced and late enhancement scan (for single-energy acquisitions) to a conventional coronary CT angiography scan improves risk stratification, requiring only minor adaptations of the contrast media and data acquisition protocols and adding only little radiation dose to the entire scan.

Critical relevance statement

This article summarizes the technical principles of myocardial extracellular volume (ECV) quantification with CT, reviews the literature comparing ECVCT with ECVMRI and histopathology, and reviews the prognostic value of myocardial ECV quantification for various cardiovascular disease.

Key points

• Non-invasive quantification of myocardial fibrosis can be performed with CT.

• Myocardial ECV quantification with CT is an alternative in patients non-eligible for MRI.

• Myocardial ECV quantification with CT strongly correlates with ECV quantification using MRI.

• Myocardial ECV quantification provides incremental prognostic information for various pathologies affecting the heart (e.g., cardiac amyloidosis).

Graphical Abstract

Keywords: Computed tomography, Extracellular volume, Late enhancement, Myocardial fibrosis, Tissue characterization

Introduction

Myocardial fibrosis is a common endpoint of several diseases affecting the myocardium [1]. Focal replacement fibrosis after myocardial infarction or diffuse interstitial fibrosis with accumulation of collagen in the extracellular space as a consequence of non-ischemic or infiltrative cardiomyopathies increase the myocardial stiffness and hamper myocardial contractility [2–7]. The reference standard for quantification of myocardial fibrosis is invasive endomyocardial biopsy with its inherent procedural risks and the possibility of sampling errors as only a small portion of the myocardium can be evaluated [8]. Therefore, non-invasive quantification of the myocardial ECV gained increasing interest in the past decade. It enables the global assessment of myocardial fibrosis and thus may represent a non-invasive quantitative measure for risk prediction and prognostication in patients with various cardiac diseases [9, 10].

While non-invasive quantification of the extracellular volume (ECV) with cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (ECVMRI) has already become a clinically established, quantitative marker [11], recently, ECV quantification with CT (ECVCT) evolved as a robust and reliable alternative. ECVCT represents a quantitative means for the evaluation of myocardial fibrosis on a cardiac late enhancement scan. In comparison to MRI, CT is more widely available, cheaper and faster and enables to obtain submillimeter isotropic volumetric image data. However, CT has the drawback of ionizing radiation, the need for potentially nephrotoxic contrast media (CM), and the lower soft tissue contrast resolution compared to MRI [12].

Extracellular distribution of iodinated contrast media

Non-invasive ECV measurements with CT or MRI depend on the pharmacokinetics of extracellular CM. In this regard, gadolinium and iodine-based CM agents share similar properties. After injection, the CM agents diffuse passively from the vascular space into the extracellular space down a concentration gradient. Later, the concentration gradient reverses and the CM agents reenter the vascular space. At a certain (late) timepoint after CM injection, a state of “quasi” equilibrium is reached, where tissue contrast enhancement parallels that of the blood. After reaching an equilibrium, both the intravascular and extracellular CM concentration declines with time due to the elimination of CM by the kidneys [12].

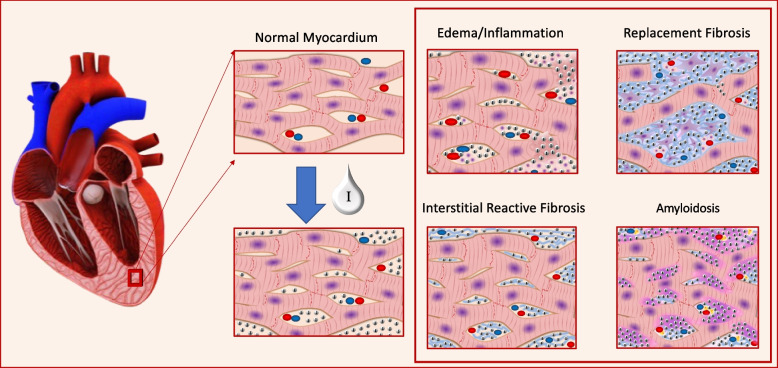

In myocardial tissue with an expansion of the extracellular matrix (ECM) due to an expansion of the collagen volume fraction, edema or amyloid deposition, the ratio between the amount of extracellular CM in the myocardium and the amount of CM in the vascular space is higher compared to healthy myocardium. The properties of both gadolinium and iodine are used to quantify these differences via measuring the T1-relaxation by MRI or the CT attenuation, both being proportional to the concentration of the respective CM agent. A schematic illustration about the extracellular space is provided in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Schematic illustration of myocardial fibrosis. Left: normal myocardium and iodine distribution after contrast media administration. Right: four pathologic conditions related to the expansion of the extracellular matrix: inflammation with edema; replacement fibrosis; interstitial reactive fibrosis and amyloidosis

While both (MRI and CT) techniques for the non-invasive quantification for ECV emerged around the same time [13, 14], initially, ECVMRI gained more attraction due to the widespread use of late gadolinium enhancement imaging to assess focal myocardial fibrosis. In these cases, ECVMRI added the possibility to also assess global or diffuse myocardial fibrosis. Initially, CT was characterized by only small HU differences between normal and pathologic myocardium [12] hindering widespread clinical use. The recent introduction of low tube voltage scanning and dual-energy techniques increased the contrast-to-noise ratio of late enhancement scans improving the delineation of pathologic myocardium and thus triggered the recent interest in late enhancement scanning and ECV quantification with CT.

Non-invasive quantification of ECVCT in comparison to ECVMRI

ECV evaluation with cardiac MRI is a well-established method to non-invasively assess the presence of interstitial myocardial fibrosis. Despite the standard reference role of MRI, the technique is characterized by several limitations including the relatively long acquisition time, the requirement of T1 mapping techniques, and the necessity for expertise in the acquisition and analysis of the images being susceptible to artifacts. In this regard, CT offers the opportunity to assess ECV in a shorter acquisition time being less susceptible for artifacts. Moreover, the access to CT scanners being capable of ECV assessment is easier compared to MRI, and CT is a cheaper and faster method to assess ECV in a non-invasive way. Furthermore, CT allows to perform ECV evaluations in patients with metal implants or devices potentially reducing image quality and interpretability of cardiac MRI, in patients with contraindications to MRI, and in patients with claustrophobia [12, 15]. In contrast to cardiac MRI, CT provides a volumetric 3-dimensional ECV assessment with high-resolution data and isotropic voxels.

The disadvantages of CT are the radiation dose, the potential nephrotoxicity from CM administration in patients at risk for contrast-induced nephropathy [16], and the limited contrast-to-noise ratio, as detailed below.

How is ECV calculated?

The calculation of ECV is based on the ratio between the concentration of CM in the myocardium and in the plasma part of the blood pool, therefore measuring the hematocrit (Ht) of the patient is required to convert whole blood to plasma concentrations.

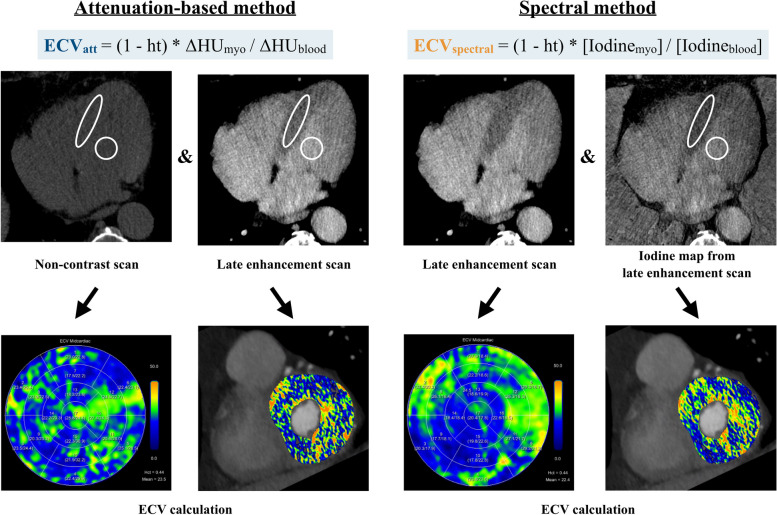

For single-energy CT, the acquisition of two scans is mandatory to calculate ECVCT: an ECG-gated non-enhanced CT scan and an ECG-gated late enhancement scan in the equilibrium phase, acquired between 3 and 10 min after CM administration as detailed below. The differences of Hounsfield units (∆HU) between the pre- and the post-contrast scans are used to assess the distribution of CM, using the following formula [17]:

Measurements of HU are obtained by drawing a region of interest (ROI) in the left ventricular cavity for blood pool values and in the myocardium to assess the amount of extracellular CM in the myocardium [14, 18].

However, this single-energy CT method can be limited by misregistration issues occurring during manual tracing of the ROIs (especially in the non-enhanced scan, in which the visualization of myocardial septal wall can be difficult) [19], due to an automatic voxel-wise misregistration or in case of variable heart rates (non-matching acquisition between non- and late-enhancement scans) [18].

In this scenario, the use of dual energy-capable CT scanners has improved the robustness of this technique. Spectral separation of late enhancement scans acquired with different tube voltages or with energy-sensitive detectors allows for material decomposition and, thus, quantification of iodine [15].

With this method, the quantification of ∆HU can be directly performed on iodine maps obtained from late enhancement scans without the need for a non-enhanced acquisition [17], thus making the ECVCT calculation easier compared to the subtraction method. The formula used for ECVCT in case of spectral imaging acquisition is:

A schematic illustration showing ECV calculation with CT is shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Extracellular volume (ECV) calculation using the single-energy attenuation-based and the spectral method in a 77-year-old male patient. ECV was not elevated with a mean ECV of 23.5% and 22.4% using the attenuation-based and spectral method, respectively. No focal scar was seen, which was confirmed by previous CMR. Abbreviations: Ht, hematocrit; ΔHUmyo, change in attenuation of the myocardium; ΔHUblood, change in attenuation of the blood pool; [Iodinemyo], iodine concentration within the myocardium; [Iodineblood], iodine concentration within the blood pool

ECV quantification with CT—acquisition protocols

Late enhancement scan timing

Several acquisition protocols for late enhancement CT scans in the equilibrium phase of iodinated CM distribution were evaluated in recent years using different CM administration protocols with various time delays for the late phase acquisition. Table 1 shows a summary of studies evaluating ECVCT quantification, detailing scan, reconstruction, and contrast media protocols.

Table 1.

Summary of studies evaluating ECV quantification with CT, detailing scan, reconstruction, and contrast media protocols

| Scanner type | Non-enhanced scan | Timing of LE scan [min] | Slice thickness/ | Tube voltage | ECG-gating | Contrast media [mgI/mL] | Dose of contrast media | Effective radiation dosea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single-energy protocols | |||||||||

| Nacif, 2012 [14] | Aquilion One (Toshiba) | Yes | 10 | 3 mm | 120 kVp | Prospective | Iopamidol (370) | Bolus of 125 mL ± 24 mL | 1.98 ± 0.16 mSv for non-enhanced and LE scan |

| Bandula, 2013 [12] | Somatom Sensation 64 (Siemens) | Yes | 25 | 5 mm | 120 kVp | Retrospective | Iohexol (300) | Bolus of 1 mL/kg body weight + infusion of 1.88 mL/kg/h | 10.7 ± 3.4 mSv (total cardiac CT protocol) |

| Hamdy, 2018 [20] | Somatom Force (Siemens) | Yes | 3, 5, 7 | 1 mm | 80 kVp | Prospective | Iopamiron (370) | Bolus of 1.6 mL/kg body weight | 11.8 ± 2.9 mSv (total cardiac CT protocol) |

| Scully, 2020 [21] | Somatom Force (Siemens) | Yes | 3, 5 | 2 mm | 80 kVp | Prospective | Iohexol (300) | Bolus of 90 mL | 5.1 ± 0.3 mSv for non-enhanced and LE scan |

| Tamarappoo, 2020 [10] | Somatom Definition Flash (Siemens) | Yes | 5 | 3 mm | 120 kVp | Prospective | Iohexol (350) | Bolus of 100 mL | 25.7 ± 6.9 mSv (total cardiac CT protocol) |

| Dual-energy protocols | |||||||||

| Lee, 2016 [18] | Somatom Definition Flash (Siemens) | No | 12 | 0.75 mm | 100/140 kVp | Retrospective | Iopamidol (370) | Bolus of 1.8 mL/kg body weight | 5.59 ± 0.85 mSv (total cardiac CT protocol) |

| Abadia, 2019 [15] | Somatom Force (Siemens Healthcare) | No | 7 | 1.5 mm | 90/150 kVp | Prospective | Iopamidol (370) | Bolus of 65 mL | 3.61 mSv [2.78–4.21] (total cardiac CT protocol) |

| Oda, 2019 [22] | iQon Spectral CT (Philips) | No | 7 | 0.67 mm | 120 kVp | Prospective | Iopamidol (370) | Bolus of 1.5 mL/kg body weight | 4.8 ± 1.6 mSv for LE scan |

| Ohta, 2020 [23] | Discover CT 750 HD (GE) | No | 7–8 | 0.625 mm | 80/140 kVp | Prospective | Iopamidol (370) | Bolus of 0.9 mL/kg body weight + infusion until 1.4 mL/kg/scan | 3.42 ± 0.87 mSv for LE scan |

| Dubourg, 2021 [17] | Discover CT 750HD (G) | No | 7 | 0.625 mm | 80/140 kVp | Prospective | Iohexol (350) | Bolus of 65 mL | 1.89 ± 0.38 mSv for LE scan |

| Qi, 2022 [24] | Somatom Force (Siemens) | No | 7 | 0.6 mm | 90/150 kVp | Prospective | Iopromide (370) | Two boli of 50 mL + 50 mL | 5.9 mSv [4.5–8.4] (total cardiac CT protocol) |

| Photon-counting detector CT scanner | |||||||||

| Mergen, 2022 [25] | NAEOTOM Alpha (Siemens) | Yes | 5 | 1.5 mm | 120 kVp | Prospective | Iopromide (370) | Bolus of 100 mL | 1.2 mSv [0.97–1.75] for LE scan |

LE Late enhancement

aEffective radiation dose was calculated by multiplying the DLP by a factor of 0.014, if not available in the publication

To calculate ECVCT using single-energy protocols, first a non-enhanced scan is acquired, followed by CT angiography for coronary artery assessment and finally, a delayed phase acquisition, most often performed with the same acquisition parameters as the non-enhanced scan [14]. One of the first studies assessing ECVCT used a non-enhanced and a delayed scan 10 min after CM administration for ECV calculation [14]. The scans were acquired with prospective ECG triggering at 120 kV tube voltage and reconstructed with a slice thickness of 3 mm. Several other studies acquired late enhancement scans at different timepoints after CM administration. Hamdy et al. [20] compared ECV measurements obtained with late enhancement scans acquired at 3, 5, and 7 min after CM administration at a tube voltage of 80 kV in patients with known or suspected coronary artery disease. They reported no significant differences of ECV values between the three acquisition timepoints, both for infarcted segments and remote myocardium. However, the delineation of scars on scans with a 5- or 7-min delay achieved higher contrast-to-noise ratio and higher subjective image quality scores compared to the late enhancement scans obtained 3 min after CM administration due to lower tissue enhancement in myocardial segments without scaring [20]. Scully et al. [21] compared ECV at 3 and 5 min in 104 patients before transcatheter aortic valve replacement. They found a small average difference of 0.68% between the two delays, mainly caused by ECV values above 35% (amyloidosis, infarcts).

Other studies on patients with cardiac amyloidosis and in patients with severe aortic stenosis prior to transcatheter aortic valve replacement used a late enhancement scan acquisition at 7 min after CM administration with 120 kV at a 2 mm slice thickness [26], with a 5-min delay at 120 kV and a slice thickness of 1.2 mm [27], or with a 5-min delay using 120 kV for the non-enhanced scan and 80 kV for the late enhancement scan [28].

For dual-energy-based ECVCT calculation, the timing of late enhancement acquisitions varied between studies as well. For dual source dual-energy CT, the acquisition of late enhancement scans ranged between 5 and 12 min after CM administration [18, 24, 29, 30], both with prospective and retrospective ECG-triggering, using energy levels at 80 or 90 kV and 140 or 150 kV [18, 29]. Otha et al. calculated ECVCT using the rapid kV switching technique (80–140 kV) with a late enhancement acquisition performed 7–8 min after CM injection [23]. For dual-layer dual-energy ECV-calculation, the late enhancement scan was acquired 7 min after CM injection, using a tube voltage of 120 kV [22]. ECV quantification with a dual-source photon-counting detector CT has been reported at 5 min acquired at 120 kV, showing a high correlation with single-energy-based ECV measurements [25].

As a conclusion, a late enhancement scan acquisition 3 min after CM injection may be good for quantification of ECV in patients with normal myocardium or diffuse expansion of the interstitium with higher myocardial tissue contrast compared to late enhancement scans at later timepoints after image acquisition. Late enhancement scan acquisition at 5 min may still allow robust ECVCT quantification even with lower tissue contrast of the myocardium but may in addition improve the visualization of focal scars due to lower tissue enhancement of normal myocardium.

CM injection protocols

Late enhancement scans are acquired as part of a cardiac CT scan to provide additional information of the myocardium. While coronary CT angiography may be acquired with a low dose CM protocol, e.g., using only 30 mL of iobitridol, 350 mg iodine/mL in patients with a body surface area of < 1.7 m2 [31], this small amount of contrast media may not be sufficient for ECV calculation due to the low contrast-to-noise ratio of late enhancement scans, mainly depending on the timing of the late enhancement scan and the given total amount of CM [32]. Therefore, the contrast media protocol must be adapted when the acquisition of a late enhancement is considered.

The amount and strategy of CM administration for CT protocols including a late enhancement acquisition vary between studies: Initially, Bandula et al. applied a CM protocol consisting in an injection of a iohexol bolus (1 mg/kg at a rate of 3 mL/s) immediately followed by an infusion of 1.88 mL CM/kg/h (with a maximum of 200 mL) in order to reach an equilibrium between blood and tissue CM concentration, acquiring the delayed phase 25 min after the first bolus injection [12]. While this CM injection scheme may result in a true steady state of CM distribution between the vascular and extracellular space, it is difficult to apply in clinical practice. More practical CM protocols are reported by Hammer et al. [26] using a fixed bolus of 50–60 mL of iopromide 370, by Scully et al. [21] using a fixed bolus of 90 mL iohexol 300 or by Qi et al. [24] using a bolus of 50 mL iopromide 370 for coronary angiography followed by an additional bolus of 50 mL of iopromide 370 before late enhancement scan acquisition. Other groups adapted the CM volume to body weight reaching a total volume of 1.4–1.8 mL/kg of iopamidol [18, 22, 23] or 1 mL/kg of iohexol [27].

Overall, late enhancement scans benefit from a higher volume (in g) of administered contrast media, as a sufficient contrast-to-noise ratio is critical for ECV calculation. Based on the current literature, fixed volumes of 50–100 mL or weight-dependent volumes of 1.4–1.8 mL/kg of contrast media seem to provide adequate image quality for ECV calculation.

Radiation dose

The additional information provided by ECVCT comes at the expense of an additional CT scan requiring a longer CT slot and at the expense of additional radiation dose.

Comparing the radiation dose reported in literature for CT protocols including a delayed phase is a challenging task, as authors used different CT scanners, tube voltages, and acquisition protocols [10, 12, 14, 15, 17, 18, 20, 22–25]. Nacif et al. reported a mean effective radiation dose of 1.98 ± 0.16 mSv for the late enhancement scan assessed with a single-energy approach [14]. With dual-energy CT, the delayed phase acquisition reached an effective radiation dose ranging from 1.89 mSv to 4.8 mSv [17, 22, 23]. ECVCT assessment with the novel PCD scanner allowed for a low effective radiation dose achieved for the late enhancement scan: 1.2 mSv [0.97–1.75]), according to Mergen et al. [25], and 2.07 ± 1.9 mSv, according to Aquino et al. [33].

In comparison, typical radiation doses of coronary CT angiography range between 1 and 15 mSv [14, 20, 23], whereas more modern CT scanners require lower doses.

Clinical validation of ECVCT against ECVMRI, histopathology and clinical data

Accurate ECVCT quantification in comparison with endomyocardial biopsy (EMB), which represents the gold standard for the evaluation of myocardial fibrosis, and in comparison with ECVMRI, which is considered the clinical imaging alternative to EMB, is imperative to use ECVCT in clinical routine. Table 2 presents a summary of studies correlating ECVCT with histopathology and with ECVMRI.

Table 2.

Summary of studies correlating ECV quantification with CT to ECV measurement with MR imaging and histopathology

| CT–MR imaging correlation | |||||||||||||

| Number of patients | Population | CT scanner | CT contrast media | CT timing for late phase | MR scanner | MR sequence | MR contrast media | MR timing for late phase | ECV measurement | Correlation coefficient and p-values | |||

| Nacif, 2012 [14] | 24 | Heart failure | Aquilion One (Toshiba) | 125 mL ± 24 mL of iopamidol (370 mgI/mL) | 10 min | 3 T Verio (Siemens Healthcare) | MOLLI | 0.15 mmol/kg gadopentetate dimeglumine | 12 min | Anterior and antero-lateral segments |

r = 0.82, p < 0.001 |

||

| Treibel, 2015 [34] | 26 | Amyloidosis | Somatom Sensation 64 (Siemens) | 1 mL/kg of iodixanol | 5 min and 15 min | 1.5 T Avanto (Siemens Healthcare) | shMOLLI | Not provided | 15 min | Septal | r2 = 0.85 (5 min) and 0.74 (15 min), p < 0.001 | ||

| Lee, 2016 [18] | 23 | Non-ischemic cardiomyopathies | Somatom Definition Flash (Siemens) | 1.8 mL/kg of iopamidol (370 mgI/mL) | 12 min | 3 T Magnetom Trio (Siemens Healthcare) | MOLLI | 0.2 mmol/kg gadobutrol | 15 min | All myocardial segments |

ICC = 0.992 (reader 1) ICC = 0.987 (reader 2) |

||

| Hayashi, 2022 [35] | 20 | Pulmonary hypertension | IQon Spectral CT (Philips) | 550 mgI/kg of iopamidol | 7 min | 3 T Ingenia CX (Philips Healthcare) | shMOLLI | 0.2 mmol/kg gadobutrol | 15 min | Interventricular junctions, septum, RV and LV free wall |

r = 0.84, p < 0.001 (interventricular junctions) r = 0.73–0.79, p < 0.001 (septum and LV free wall) r = 0.26, p: 0.263 (RV free wall) |

||

| Aquino, 2023 [33] | 29 | No specific clinical indication | NAEOTOM Alpha (Siemens) | 100 mL of iopromide | 5 min | 1.5 T Magnetom Avanto (Siemens healthcare) | MOLLI | 0.1 mmol/kg gadobutrol | 10–12 min | Global and mid-ventricular | r = 0.91, p < .001 | ||

| Baggiano, 2023 [36] | 39 | Dilated cardiomyopathy | Revolution CT (GE) | 1.5 mL/kg Iomeron (400 mg/mL) | 8 min | 1.5 T Discovery MR 450 (GE Healthcare) | MOLLI | 0.1 mmol/kg gadobutrol | 10–15 min | All myocardial segments | r = 0.819, 95% (CI: 0.791 to 0.844) | ||

| CT–histopathological correlation | |||||||||||||

| Number of patients | Study population | CT scanner | CT contrast media | CT timing for late phase | Biopsy sample site | Samples fixing methods | EMB collagen volume fraction | ECV CT measurement | Correlation coefficient and p-values | ||||

| Bandula, 2013 [12] | 23 | Severe aortic stenosis | Somatom Sensation 64 (Siemens) | A bolus of 1 mL/kg + Infusion of 1.88 mL/kg/h of iohexol (300 mgI/mL) | 25 min | Interventricular septum | 10% buffered formalin | 18% [5–40%] | Septal |

r = 0.71, p = 0.0007 |

|||

Animal models with doxorubicin-induced dilated cardiomyopathy using a dual-energy CT technique in adult New Zealand rabbits [32] and using a single-energy CT technique in beagles [37] showed a strong correlation between ECVCT versus collagen volume fraction (CVF) at histology (r = 0.925 and r = 0.951, respectively; p < 0.001 for both) and between ECVCT versus ECVMRI (r = 0.888 and r = 0.899, respectively; p < 0.001 for both). In addition, ECVCT correlated well (r = 0.830–0.907, p < 0.05) with the serum fibrosis index (hyaluronic acid, laminin, and type-III procollagen) in the study of Zhou et al. [37].

In the presence of severe aortic stenosis, Bandula et al. challenged ECVCT versus EMB and ECVMRI in 23 patients [12]. ECVCT was assessed on late enhancement scans acquired 25 min after injection of a bolus followed by slow maintenance infusion of iodinated CM. ECVCT significantly correlated with histological extracellular fibrosis, measured as CVF on a septal myocardial sample collected during valve replacement surgery (r = 0.71, p = 0.0007) and with ECVMRI (r = 0.73, p < 0.0002) [12].

Cardiac amyloidosis has been found to co-exist in up to 16% of patients with severe aortic stenosis [21]. In a study by Scully et al. including 109 patients with severe aortic stenosis, global ECVCT had an AUC of 0.95 and 0.87 to detect grade 2 and higher, or any grade of amyloidosis, respectively, using 99mTc-DPD scintigraphy as the reference [21]. The authors proposed a threshold of 31% as a clinical screening threshold for scintigraphy and other examinations. Treibel et al. [34] compared ECVCT with ECVMRI in 26 patients with a biopsy-proven systemic amyloidosis and 27 patients with aortic stenosis and demonstrated a stronger correlation between ECVCT and ECVMRI when assessed with a late enhancement scan obtained 5 min (r2 = 0.85) compared to 15 min (r2 = 0.74) after CM injection. Moreover, they found that ECVCT was associated with increased laboratory markers (including NT-pro-BNP, troponin), a shorter distance achieved in a 6-min walk test, and the bone scintigraphy amyloid burden (p < 0.001) [34].

In patients with known or suspected pulmonary hypertension, ECVCT strongly correlated with ECVMRI in the septum and left ventricular free wall (r = 0.79–0.73), while there was only a weak correlation for the right ventricular free wall (r = 0.26) [35]. In addition, the mean pulmonary artery pressure had a good correlation to the ECVCT in the anterior right ventricular insertion points (r = 0.64), the latter being a potential noninvasive surrogate marker of disease severity in pulmonary hypertension.

In patients with nonischemic cardiomyopathy (hypertrophic or dilated cardiomyopathy, amyloidosis or sarcoidosis), Lee H-J et al. [18] showed that ECVCT calculated from dual-energy late enhancement CT scans obtained 12 min after CM injection was significantly higher compared to ECVCT in healthy subjects (p < 0.01). In the same study, authors found similar values for ECVCT (34.5% ± 9.0) and ECVMRI (34.2% ± 9.0) [18]. Nacif et al. also observed elevated ECV values in patients with heart failure compared to healthy volunteers and a good correlation between ECVCT and ECVMRI (r = 0.82, p < 0.001) but also a small bias (+ 3%) towards higher ECVCT compared to ECVMRI [14]. In contrast, Baggiano et al. compared ECVCT with ECVMRI in 39 patients with dilated cardiomyopathy and showed a strong correlation (all segments, r = 0.819) between both methods, while ECVCT values were slightly lower (31.8 ± 6.5% vs 33.9 ± 8.0%, respectively, p < 0.001) [36]. In general, myocardial ECVCT assessed with dual-energy CT has an excellent reproducibility and good agreement with ECVMRI in patients with nonischemic cardiomyopathy [18] and heart failure [23, 38]. Moreover, ECVCT is positively correlated with the NYHA classification in patients with non-ischemic heart failure with preserved ejection fraction [24]. ECVCT may even serve as an early biomarker of cardiotoxicity in patients with cardiac dysfunction after anthracycline chemotherapy [39, 40] or chest radiation therapy for esophageal cancer [41], as elevated ECVCT were observed in these patients.

Using a first-generation dual-source photon-counting detector CT, Aquino et al. [33] calculated ECVCT in 29 patients (13 with known cardiomyopathy, 4 with prior myocardial infarction) using both the single-energy and dual-energy approach and then compared these values with ECVMRI. The authors found a strong correlation between dual- and single-energy-based techniques (r = 0.91, p < 0.001) with the dual-energy approach yielding the possibility of reducing radiation dose by 40%. In addition, ECVCT measured by dual-energy photon-counting detector CT had a strong correlation with ECVMRI for midventricular and global quantification (r = 0.82 and 0.91, both p < 0.001), while ECVCT was higher by approximately 2% compared to ECVMRI, similar to the results reported by Nacif et al. [14].

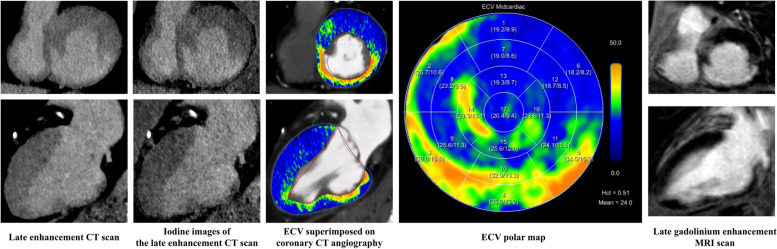

Representative image examples of late enhancement scans including ECVCT calculations are shown in Figs. 3 and 4.

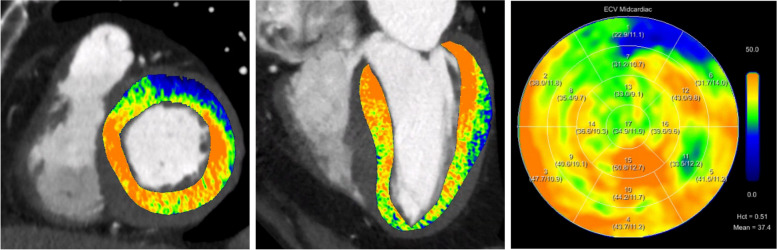

Fig. 3.

Extracellular volume (ECV) images and maps calculated using the spectral method from late enhancement CT shows elevated myocardial ECV in a 78-year-old male patient with confirmed transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis (ATTR)

Fig. 4.

Late enhancement scan and extracellular volume (ECV) calculation in an 89-year-old male patient. Conventional images and iodine maps from the late enhancement scan show increased transmural contrast enhancement of the inferoseptal, inferior and inferobasal myocardium. Elevated ECVCT values were observed in these regions suggesting a focal scar. Findings were confirmed by cardiac MRI. Note the identical extent of the scar on both modalities

The prognostic value of ECVCT

The prognostic role of ECVCT for predicting outcome has been evaluated in various clinical scenarios and diseases.

ECVCT showed predictive value for outcome of patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) or surgical valve replacement [10, 21, 26, 28, 29, 42]. Ishiyama et al. demonstrated in 71 patients with severe aortic valve stenosis undergoing TAVR that ECVCT ≤ 32% was associated with a greater reduction in left ventricular mass at follow-up, and ECVCT represented the best independent predictor of hospitalization due to heart failure [28]. Increased ECVCT obtained from pre-procedural TAVR planning CT (ECVCT > 33%) in patients with low-flow low-gradient aortic stenosis was also found to be a significant predictor of heart failure and 2-year mortality after TAVR [10]. Similarly, Scully et al. [21] showed in 112 TAVR patients with lone aortic stenosis (amyloidosis excluded) that medium-term (> 1.5 years) mortality hazard doubled with a 2% increase in ECV. Furthermore, several authors demonstrated that in patients with severe aortic stenosis, ECVCT was significantly correlated with NYHA class, B-natriuretic peptide, echocardiographic left ventricular ejection fraction and E/e’ ratio, and an increased risk of stroke as well as heart failure after transcatheter or surgical valve replacement [26, 29, 43, 44].

In patients with confirmed systemic amyloidosis and variable cardiac involvement, ECVCT correlated with adverse cardiac remodeling and septal ECVCT was independently associated with all-cause mortality in patients with transthyretin (but not light chain) amyloid (hazard ratio: 1.046, p < 0.05) [27].

ECVCT was a predictor for major cardiovascular events (MACE, defined as death, ventricular tachycardia or fibrillation and heart failure) at follow-up in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy with an ECVCT of 33% as cut-off to distinguish between patients at high and low risk for MACE [45].

Another potential application of ECVCT is the identification and characterization of myocardial injury in patients with acute chest pain and cardiac troponin elevation. In recent years, coronary CT angiography has gained an increasing role in the emergency setting, thanks to the ability to rapidly rule out obstructive coronary artery disease with simultaneous imaging of the aorta and pulmonary arteries. However, there are acute cardiac conditions with unobstructed coronary arteries, which cannot be diagnosed by coronary CT angiography alone, such as acute myocarditis, myocardial infarction with non-obstructed coronary arteries, and various cardiomyopathies. In this clinical scenario, implementation of a cardiac CT protocol that allows scar detection by late iodine enhancement and ECVCT assessment could be of benefit to establish the proper diagnosis earlier, shorten the hospitalization time, and avoid unnecessary downstream tests (including cardiac MRI), thereby reducing the overall cost to the healthcare system [46]. Thus, Palmisano et al. recently proposed a chest pain protocol in which a late enhancement scan (obtained 10 min after CM application) is performed when there are no findings in coronary CT angiography [47]. In their study, they assessed 84 patients with acute chest pain, 42 of whom had an unremarkable coronary CT angiography. The combination of the arterial phase with late enhancement allowed for the following diagnoses: myocarditis (52%), takotsubo cardiomyopathy (10%), amyloidosis (7%), myocardial infarction with non-obstructed coronary arteries (7%), dilated cardiomyopathy (5%), whereas in 19% of the patients, there were no or inconclusive findings. Therefore, late enhancement cardiac CT may even be helpful in the acute setting and expands the diagnostic yield of the modality.

Future outlook on potential applications

The continuously increasing availability of dual-energy-capable CT scanners and the recent advent of clinical photon-counting detector CT systems are advantageous for the more widespread use of ECV calculations with CT. The availability of spectral data for ECV calculation render the need for a non-enhanced CT for this purpose unnecessary. A single, spectrally acquired late enhancement acquisition enables both the calculation of the ECVCT and the quantification of cardiac calcifications using virtual non-enhanced images [48]. Thus, future protocols may indicate a shift from a non-enhanced to a standard late phase acquisition at comparable radiation dose but with a higher diagnostic and prognostic value [48]. This approach may be particularly promising in patients planned to undergo TAVR. In these patients, cardiac amyloidosis is a frequent finding [21], and ECVCT is a predictor of long-term prognosis [27].

To non-invasively calculate ECV, the patient’s serum Ht must be measured via blood sampling. However, the Ht may not be always available when cardiac CT scans are performed, particularly in the outpatient setting. In this regard, as shown with ECVMRI [49, 50], some studies proposed to calculate a synthetic Ht by measurements of the attenuation (in HU) of the blood pool of non-enhanced scans or on virtual non-enhanced images from contrast-enhanced dual-energy CT data [51, 52].

Due to the spectral dependency of iron, the calibration curve has to be determined for each CT scanner separately. Moreover, several technical issues must be considered, including the influence of scan parameters such as tube voltage and iterative reconstruction algorithms on tissue or vascular attenuation. In dual-energy CT acquisitions, the monoenergetic reconstruction level may also have an influence on the formula to non-invasively and synthetically calculate the Ht.

As a drawback of this method, synthetic ECV calculation has the potential for a relevant misclassification of ECV for the individual patient, Chen et al. showed that even when using scanner-specific models for calculating synthetic ECVMRI, the ECV could be under- or overestimated by 4% compared to ECVMRI calculation using the blood Ht level [50]. This drawback may be similar in synthetic ECVCT calculation as Treibel et al. showed that differences on a per patient level were as high as 8% [52].

Conclusion

Myocardial ECV is related to myocardial fibrosis, amyloid deposition, or edema and is associated with patient outcome. ECVCT calculation represents a relatively easy, fast, and robust technique to non-invasively detect focal or global increases in myocardial ECV, particularly when using dual-energy capable CT scanners. Several studies have already shown the prognostic value of ECV quantification with CT in various cardiac disease. However, the incremental value of ECVCT comes at the expense of the need to adapt the CM protocols, add radiation dose, and extend the time needed to complete the entire cardiac CT scan. The further availability of spectral CT machines including photon-counting detector CT may further enhance the clinical role of this technique in the near future as spectral data may allow for ECVCT calculation with a lower CM volume and lower radiation dose.

Acknowledgements

We want to express our gratitude to Ernst Klotz, PhD, for his critical review of this article.

Abbreviations

- CM

Contrast media

- CT

Computed tomography

- CVF

Collagen volume fraction

- ECM

Extracellular matrix

- ECV

Extracellular volume

- ECVCT

Extracellular volume quantification with cardiac CT

- ECVMRI

Extracellular volume quantification with cardiac MRI

- EMB

Endomyocardial biopsy

- HT

Hematocrit

- HU

Hounsfield units

- MACE

Major adverse cardiovascular events

- MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging

- NYHA

New York Heart Association

- ROI

Region of interest

- TAVR

Transcatheter aortic valve replacement

Authors’ contributions

All authors made significant contributions in this article including literature review, summaries, drafting the manuscript and tables, and design and composition of the figures.

Funding

No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

H.A.: institutional grants from Bayer, Canon, Guerbet, and Siemens. Speakers bureau: Siemens.

M.E.: speakers fee from Siemens.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Wong TC, Piehler K, Meier CG, et al. Association between extracellular matrix expansion quantified by cardiovascular magnetic resonance and short-term mortality. Circulation. 2012;126:1206–1216. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.089409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Talman V, Ruskoaho H. Cardiac fibrosis in myocardial infarction—from repair and remodeling to regeneration. Cell Tissue Res. 2016;365:563–581. doi: 10.1007/s00441-016-2431-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prabhu SD, Frangogiannis NG. The biological basis for cardiac repair after myocardial infarction. Circ Res. 2016;119:91–112. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.303577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brooks A. Interstitial fibrosis in the dilated non-ischaemic myocardium. Heart. 2003;89:1255–1256. doi: 10.1136/heart.89.10.1255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maron BJ, Maron MS, Maron BA, Loscalzo J. Moving Beyond the sarcomere to explain heterogeneity in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:1978–1986. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.01.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aquaro GD, Ghebru Habtemicael Y, Camastra G, et al. Prognostic value of repeating cardiac magnetic resonance in patients with acute myocarditis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74:2439–2448. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.08.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trachtenberg BH, Hare JM. Inflammatory cardiomyopathic syndromes. Circ Res. 2017;121:803–818. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.310221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anderson KR, Sutton MGSJ, Lie JT. Histopathological types of cardiac fibrosis in myocardial disease. J Pathol. 1979;128:79–85. doi: 10.1002/path.1711280205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scully PR, Bastarrika G, Moon JC, Treibel TA. Myocardial extracellular volume quantification by cardiovascular magnetic resonance and computed tomography. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2018;20:15. doi: 10.1007/s11886-018-0961-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tamarappoo B, Han D, Tyler J, et al. Prognostic value of computed tomography–derived extracellular volume in tavr patients with low-flow low-gradient aortic stenosis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020;13:2591–2601. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2020.07.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Messroghli DR, Radjenovic A, Kozerke S, et al. Modified Look-Locker inversion recovery (MOLLI) for high-resolutionT1 mapping of the heart. Magn Reson Med. 2004;52:141–146. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bandula S, White SK, Flett AS, et al. Measurement of myocardial extracellular volume fraction by using equilibrium contrast-enhanced CT: validation against histologic findings. Radiology. 2013;269:396–403. doi: 10.1148/radiol.13130130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Flett AS, Hayward MP, Ashworth MT, et al. Equilibrium contrast cardiovascular magnetic resonance for the measurement of diffuse myocardial fibrosis. Circulation. 2010;122:138–144. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.930636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nacif MS, Kawel N, Lee JJ, et al. Interstitial myocardial fibrosis assessed as extracellular volume fraction with low-radiation-dose cardiac CT. Radiology. 2012;264:876–883. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12112458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abadia AF, van Assen M, Martin SS, et al. Myocardial extracellular volume fraction to differentiate healthy from cardiomyopathic myocardium using dual-source dual-energy CT. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2020;14:162–167. doi: 10.1016/j.jcct.2019.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cavalcante JL, Koike H. The rise of myocardial extracellular volume fraction in computed tomography for identification of cardiac amyloidosis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2022;15:2095–2097. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2022.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dubourg B, Dacher J-N, Durand E, et al. Single-source dual energy CT to assess myocardial extracellular volume fraction in aortic stenosis before transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) Diagn Interv Imaging. 2021;102:561–570. doi: 10.1016/j.diii.2021.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee H-J, Im DJ, Youn J-C, et al. Myocardial extracellular volume fraction with dual-energy equilibrium contrast-enhanced cardiac CT in nonischemic cardiomyopathy: a prospective comparison with cardiac MR imaging. Radiology. 2016;280:49–57. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2016151289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tesche C, Gray HN, Albrecht MH. Dual-energy CT for analyzing extracellular volume fraction: a promising novel technique in myocardial fibrosis diagnostics? J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2020;14:377–378. doi: 10.1016/j.jcct.2020.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hamdy A, Kitagawa K, Goto Y, et al. Comparison of the different imaging time points in delayed phase cardiac CT for myocardial scar assessment and extracellular volume fraction estimation in patients with old myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019;35:917–926. doi: 10.1007/s10554-018-1513-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scully PR, Patel KP, Saberwal B, et al. Identifying cardiac amyloid in aortic stenosis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020;13:2177–2189. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2020.05.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oda S, Emoto T, Nakaura T, et al. Myocardial late iodine enhancement and extracellular volume quantification with dual-layer spectral detector dual-energy cardiac CT. Radiol Cardiothorac Imaging. 2019;1:e180003. doi: 10.1148/ryct.2019180003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ohta Y, Kishimoto J, Kitao S, et al. Investigation of myocardial extracellular volume fraction in heart failure patients using iodine map with rapid-kV switching dual-energy CT: segmental comparison with MRI T1 mapping. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2020;14:349–355. doi: 10.1016/j.jcct.2019.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Qi R-X, Jiang J-S, Shao J, et al. Measurement of myocardial extracellular volume fraction in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction using dual-energy computed tomography. Eur Radiol. 2022;32:4253–4263. doi: 10.1007/s00330-021-08514-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mergen V, Sartoretti T, Klotz E, et al. Extracellular volume quantification with cardiac late enhancement scanning using dual-source photon-counting detector CT. Invest Radiol. 2022;57:406–411. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0000000000000851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hammer Y, Talmor-Barkan Y, Abelow A, et al. Myocardial extracellular volume quantification by computed tomography predicts outcomes in patients with severe aortic stenosis. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0248306. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0248306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gama F, Rosmini S, Bandula S, et al. Extracellular volume fraction by computed tomography predicts long-term prognosis among patients with cardiac amyloidosis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2022;15:2082–2094. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2022.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ishiyama M, Kurita T, Takafuji M, et al. The cardiac computed tomography-derived extracellular volume fraction predicts patient outcomes and left ventricular mass reductions after transcatheter aortic valve implantation for aortic stenosis. J Cardiol. 2023;81:476–484. doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2022.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Suzuki M, Toba T, Izawa Y, et al (2021) Prognostic impact of myocardial extracellular volume fraction assessment using dual-energy computed tomography in patients treated with aortic valve replacement for severe aortic stenosis. J Am Heart Assoc 10. 10.1161/JAHA.120.020655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.van Assen M, De Cecco CN, Sahbaee P, et al. Feasibility of extracellular volume quantification using dual-energy CT. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2019;13:81–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jcct.2018.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jin KN, De Cecco CN, Caruso D, et al. Myocardial perfusion imaging with dual energy CT. Eur J Radiol. 2016;85:1914–1921. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2016.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hong YJ, Kim TK, Hong D, et al. Myocardial characterization using dual-energy CT in doxorubicin-induced DCM: comparison with CMR T1-mapping and histology in a rabbit model. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;9:836–845. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2015.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aquino GJ, O’Doherty J, Schoepf UJ, et al. Myocardial characterization with extracellular volume mapping with a first-generation photon-counting detector CT with MRI reference. Radiology. 2023;307:e222030. doi: 10.1148/radiol.222030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Treibel TA, Bandula S, Fontana M, et al. Extracellular volume quantification by dynamic equilibrium cardiac computed tomography in cardiac amyloidosis. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2015;9:585–592. doi: 10.1016/j.jcct.2015.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hayashi H, Oda S, Emoto T, et al. Myocardial extracellular volume quantification by cardiac CT in pulmonary hypertension: comparison with cardiac MRI. Eur J Radiol. 2022;153:110386. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2022.110386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baggiano A, Conte E, Spiritigliozzi L, et al (2023) Quantification of extracellular volume with cardiac computed tomography in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 10.1016/j.jcct.2023.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Zhou Z, Xu L, Wang R, et al. Quantification of doxorubicin-induced interstitial myocardial fibrosis in a beagle model using equilibrium contrast-enhanced computed tomography: a comparative study with cardiac magnetic resonance T1-mapping. Int J Cardiol. 2019;281:150–155. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2019.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang R, Liu X, Schoepf UJ, et al. Extracellular volume quantitation using dual-energy CT in patients with heart failure: comparison with 3T cardiac MR. Int J Cardiol. 2018;268:236–240. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2018.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Egashira K, Sueta D, Tomiguchi M, et al. Cardiac computed tomography-derived extracellular volume fraction in late anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity. Int J Cardiol Hear Vasc. 2021;34:100797. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcha.2021.100797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tu C, Shen H, Liu R, et al. Myocardial extracellular volume derived from contrast-enhanced chest computed tomography for longitudinal evaluation of cardiotoxicity in patients with breast cancer treated with anthracyclines. Insights Imaging. 2022;13:85. doi: 10.1186/s13244-022-01224-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Capra D, Monti CB, Luporini AG, et al. Computed tomography-derived myocardial extracellular volume: an early biomarker of cardiotoxicity in esophageal cancer patients undergoing radiation therapy. Insights Imaging. 2020;11:120. doi: 10.1186/s13244-020-00922-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Treibel TA, Patel KP, Cavalcante JL. Extracellular volume imaging in aortic stenosis during routine pre-TAVR cardiac computed tomography. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020;13:2602–2604. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2020.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vignale D, Palmisano A, Gnasso C, et al (2023) Extracellular volume fraction (ECV) derived from pre-operative computed tomography predicts prognosis in patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI). Eur Hear J Cardiovasc Imaging. 10.1093/ehjci/jead040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Han D, Tamarappoo B, Klein E, et al. Computed tomography angiography-derived extracellular volume fraction predicts early recovery of left ventricular systolic function after transcatheter aortic valve replacement. Eur Hear J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2021;22:179–185. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jeaa310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yashima S, Takaoka H, Iwahana T, et al. Evaluation of extracellular volume by computed tomography is useful for prediction of prognosis in dilated cardiomyopathy. Heart Vessels. 2023;38:185–194. doi: 10.1007/s00380-022-02154-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Esposito A, Palmisano A, Barbera M, et al. Cardiac computed tomography in troponin-positive chest pain: sometimes the answer lies in the late iodine enhancement or extracellular volume fraction map. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019;12:745–748. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2018.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Palmisano A, Vignale D, Tadic M, et al. Myocardial late contrast enhancement CT in troponin-positive acute chest pain syndrome. Radiology. 2022;302:545–553. doi: 10.1148/radiol.211288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mergen V, Ghouse S, Sartoretti T, Manka R, Euler A, Kasel AM et al (2023) Cardiac Virtual Noncontrast Images for Calcium Quantification with Photon-counting Detector CT. Radiol Cardiothorac Imaging 5(3):e220307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Treibel TA, Fontana M, Maestrini V, et al. Automatic measurement of the myocardial interstitium. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;9:54–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2015.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen W, Doeblin P, Al-Tabatabaee S, et al (2022) Synthetic extracellular volume in cardiac magnetic resonance without blood sampling: a reliable tool to replace conventional extracellular volume. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 15. 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.121.013745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Kim NY, Im DJ, Youn J-C, et al. Synthetic extracellular volume fraction derived using virtual unenhanced attenuation of blood on contrast-enhanced cardiac dual-energy CT in nonischemic cardiomyopathy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2022;218:454–461. doi: 10.2214/AJR.21.26654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Treibel TA, Fontana M, Steeden JA, et al. Automatic quantification of the myocardial extracellular volume by cardiac computed tomography: synthetic ECV by CCT. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2017;11:221–226. doi: 10.1016/j.jcct.2017.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.