Abstract

Several studies have reported associations between appetitive traits and weight gain during infancy or childhood, but none have directly compared these associations across both age periods. Here, we tested the associations between appetitive traits and growth velocities from birth to childhood. Appetitive trait data were collected using the Children’s Eating Behaviour Questionnaire (CEBQ) in 149 children from the Cambridge Baby Growth Study at age 9–17 years. These participants also provided anthropometric measurements during infancy (birth, 3, 12, 18, and 24 months) and childhood (5 to 11 years). Standardized growth velocities (in weight, length/height, BMI, and body fat percentage) for 0–3 months, 3–24 months, and 24 months to childhood were estimated using individual linear-spline models. Associations between each of the eight CEBQ traits and each growth velocity were tested in separate multilevel linear regression models, adjusted for sex, age at CEBQ completion, and the corresponding birth measurement (weight, length, BMI, or body fat percentage). The three food-approach traits (food responsiveness, enjoyment of food and emotional overeating) were positively associated with infancy and childhood growth velocities in weight, BMI, and body fat percentage. By contrast, only one of the food-avoidant traits, satiety responsiveness, was negatively associated with all growth velocities. Significant associations were mostly of similar magnitude across all age periods. These findings reveal a broadly consistent relationship between appetitive traits with gains in weight and adiposity throughout infancy and childhood. Future interventions and strategies to prevent obesity may benefit from measuring appetitive traits in infants and children and targeting these as part of their programs.

Subject terms: Epidemiology, Paediatric research

Introduction

Childhood obesity is associated with a multitude of negative health implications. Weight status in childhood tracks into adolescence and eventually adulthood. Children living with obesity are at greater risk of continuing to do so later in life. This suggests that preventive efforts are best targeted at the early years to maximise impact1. Appetitive traits are key behaviours linked with obesity, which comprise a range of food-approach and food-avoidant eating behaviours2. Characterising which appetitive traits are associated with greater velocity of weight gain across key developmental phases in infancy and childhood could help in identifying potential behavioural targets for interventions to prevent childhood obesity.

Appetitive traits are innate tendencies that are observable early in infancy and show continuity and stability throughout childhood3–5. A number of psychometric instruments have been developed to assess these traits in children6, 7. One of the most comprehensive psychometric measures is the Children’s Eating Behaviour Questionnaire (CEBQ)2. The CEBQ is a validated parent-reported instrument composed of 35 items which are used to calculate four ‘food-approach’ appetitive traits (food responsiveness, enjoyment of food, emotional overeating, and desire to drink) and four ‘food-avoidant’ appetitive traits (satiety responsiveness, slowness in eating, emotional undereating, and food fussiness). Although the food-approach traits tend to increase with age and the food-avoidant traits tend to decrease with age2, these changes are relatively small and individual children tend to hold their relative ranking in regards to appetite traits compared to their peers3, 5. A growing body of evidence underscores the substantial heritability of appetitive traits from birth onwards. For example, during the exclusively milk fed period of life in infants, genetic influences already account for approximately 53–84% of inter-individual variability in four appetitive traits8. This substantial proportion of genetic influence remain relatively stable with heritability estimates ranging between 69 and 90% for all CEBQ traits except emotional undereating in school aged-children9. However, as children mature and gain greater autonomy in their dietary decisions, their ability to express their genetic predisposition for heightened appetite may become more pronounced9. In an obesogenic and food permissive environment, this predisposes to increased dietary energy intake and, consequently, risk for obesity10.

Accumulating evidence supports the relevance of CEBQ traits to obesity risk in childhood. Longitudinal studies report that a more avid appetite is prospectively associated with faster growth in childhood (aged 6 to 10 years), indexed by higher body mass index (BMI)11–14, fat mass index (FMI), and fat-free mass index (FFMI)11. On the other hand, food avoidant appetitive traits are associated with subsequent lower childhood growth in children aged 4 to 10 years (BMI15–17, FMI, and FFMI11, 16). Similar findings have been reported regarding appetitive traits measured during infancy using the Baby Eating Behaviour Questionnaire (BEBQ) at 3 months and their subsequent association with infant weights and BMI up to 15 months of age18–20. Conversely, adiposity could also influence appetitive traits, where children of higher adiposity may develop increasingly avid appetite21. It is suggested that appetite plays a more important role in adiposity (than does adiposity in appetite development) particularly in early infancy, while the relationship becomes more complex during childhood22. To date, however, most studies, both cross-sectional and longitudinal, have focused on BMI as an index of adiposity21, which fails to differentiate between lean and fat mass23.

Recent studies have reported a relationship between appetitive traits and dietary intakes, with possible consequences for growth. In the PANIC study (n = 406 children; aged 6–8 years), enjoyment of food and food responsiveness were positively associated with intakes of nutrient-dense and protein-rich foods, assessed by 4-day food records, whereas satiety responsiveness and food fussiness were negatively associated with those food intakes24. In the Generation XXI study (n = 3879 children; 7–10 years), higher enjoyment of food and lower satiety responsive and food fussiness were associated with a higher diet quality, as evaluated by the Healthy Eating Index25. However, there are no data on the links between appetitive traits and growth from birth with consideration of both infancy and childhood growth trajectories.

Therefore, the present study aimed to assess the association between appetitive traits, as assessed by the CEBQ in children aged 9–17 years (mean age 12.5 ± 1.4 years), and growth patterns during both infancy and childhood (in weight, length/height, BMI, and body fat percentage). We hypothesized that appetitive traits would show similar associations with growth in both infancy and early childhood.

Methods

Study population

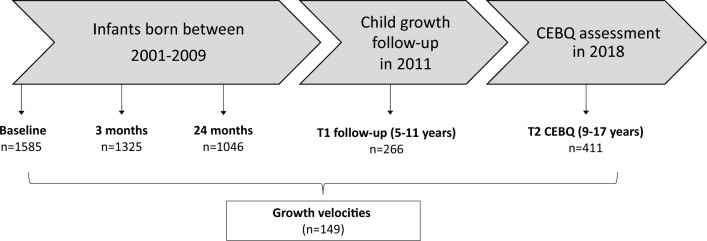

The Cambridge Baby Growth Study (CBGS) is a birth cohort of infants born between 2001 and 2009 to mothers recruited from the Rosie Maternity Hospital, Cambridge, England. Mothers aged 16 years and older and able to give consent were eligible to participate, where all experiments were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Routine data on infant sex, ethnicity, and gestational age were collected at birth, and the mode of breastfeeding was reported by parents at the 3-month clinic visit. Self-reported maternal educational attainment was categorized into high (university degree or higher), intermediate (vocational education or diploma), or low (high school education or less). Anthropometry of the child was assessed repeatedly during infancy (at birth, 3, 12, 18 and 24 months) and at one childhood clinic visit (at 5 to 11 years). The CEBQ was administered by post in 2018 to assess the children’s present appetitive traits. At the time, the children were aged between 9 and 17 years old, with a mean age of 12.5 ± 1.4 years. The sampling frame for this analysis was the 149 children who had growth velocities calculated at both infancy and childhood, and completed the CEBQ (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram showing numbers of participating infants and children. CEBQ, Child Eating Behaviour Questionnaire; T, time.

Appetitive traits

The CEBQ is a validated parent-reported questionnaire with a robust factor structure, internal reliability, and test–retest reliability2. It was administered to children aged 9 to 17, with a mean age of 12.5 ± 1.4 years. The CEBQ comprises eight subscales (traits) ascertained by 35 items answered using a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always). Food responsiveness (5 items) and enjoyment of food (4 items) indicate the child’s likelihood and enthusiasm of eating in response to food cues. Desire to drink (3 items) indicates the child’s preference to consume beverages, typically sweetened drinks. Emotional overeating (4 items) and emotional undereating (4 items) indicate eating tendencies in response to intense emotions. Satiety responsiveness (5 items) indicates the child’s perception of feelings of fullness. Slowness in eating (4 items) and food fussiness (6 items) indicate speed of eating or lack of interest in food in response to its visual presentation, texture or taste, respectively2, 3. A mean score was calculated for each subscale, with higher scores indicative of greater expression of that appetitive trait.

Growth parameters

Anthropometry was performed by trained research nurses at (mean ± SD) ‘3 months’ (3.2 ± 0.3 months), ‘12 months’ (12.5 ± 0.5 months), ‘18 months’ (18.5 ± 0.5 months), ‘24 months (24.2 ± 0.4 months), and ‘childhood’ (9.5 ± 1.1 years; range 5 to 11 years). Weight was measured to the nearest 1 g during infancy and 0.1 kg during childhood. Length/height was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm. Skinfold thickness was measured in triplicate at four body sites (triceps, subscapular, flank, and quadriceps). Total body fat mass was estimated during infancy using validated equations (fat mass in kilograms = 2.167 + 0.512 * weight in kilograms + 0.041 * triceps skinfold (SF) in millimeters + 0.008 * subscapular SF in millimeters + 0.011 * flank (suprailiac) SF in millimeters + 0.002 * age at visit in days – 0.074 * length in centimeters – 0.037 * sex (1 = male; 0 = female))26. At the childhood visit, whole-body dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) was used to assess total body fat mass27.

Growth parameters were weight, length/height, BMI (calculated by dividing weight in kilograms by height in meters squared), and body fat percentage (calculated by dividing total fat mass in kilograms by body weight in kilograms, and then multiplying by 100). Weight, length/height, and BMI values were converted to age- and sex-standardized z-scores by comparison to the British 1990 growth reference28, 29, using the Stata zanthro package. For body fat percentage, at each age, internally derived z-scores were calculated as the standardized residuals of linear regression models that included age and sex as covariates. Measurements at birth and 3 months of age were additionally adjusted for gestational age.

Growth velocities

Linear-spline multilevel models at the individual level (also known as piecewise linear models) were performed to estimate growth velocities (expressed as change in z-score per month) during each growth interval for weight, length/height, BMI, and body fat percentage. Knot points were chosen at 3 months and 24 months based on visual inspection of the data, as previously described27, giving three growth intervals: 0–3 months, 3–24 months, and 24 months to childhood.

Statistical analysis

Univariate distributions for all variables were presented as means and standard deviations for continuous variables and as frequency and percentages for categorical variables. To test the associations of growth velocities with each CEBQ trait, multivariable linear regression models were performed. The models included the combined growth intervals for weight, length/height, BMI, or body fat percentage, and as covariates: sex, age at CEBQ completion, and the corresponding standardized birth measurements (weight, length, BMI, or body fat percentage). Given that there might be age range-specific associations between the eating behaviour and growth, we wanted to assess the heterogeneity across the age groups. To do this, we used a post-estimation Wald test between the growth velocities estimated in each of 0–3 months, 3–24 months, and 24 months to childhood.

All tests were two sided and performed using Stata version 16 (StataCorp, College Station, TX) or R version 3.6.2 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Ethics declarations

Written informed consent was provided by mothers and the study was approved by the local Cambridge research ethics committee.

Results

Sample characteristics

Descriptive characteristics of the 149 children with data on CEBQ and anthropometric measurements during both infancy and childhood are summarized in Table 1, compared to excluded children (n = 1436). The included and excluded samples were similar for all characteristics, except for maternal education, which was lower in the excluded sample.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included analysis sample and excluded CBGS children.

| Mean (SD) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Analysis sample | Excluded children | |

| Characteristic | (n = 149) | (n = 1436) |

| Boys, no. (%) | 63 (42.3) | 750 (52.5) |

| Ethnicity, no. (%) | ||

| European | 114 (97.4) | 912 (95.9) |

| Asian | 3 (2.6) | 18 (1.9) |

| Black | – | 11 (1.2) |

| Other | – | 10 (1.0) |

| Missing/not specified | 32 | 485 |

| Maternal educational level, no. (%) | ||

| High | 61 (41.0) | 414 (28.8) |

| Intermediate | 16 (10.7) | 267 (18.6) |

| Low | 72 (48.3) | 755 (52.6) |

| Maternal age at birth, years | 33.7 (4.2) | 33.5 (4.3) |

| Gestational age, weeks | 40.1 (1.4) | 39.8 (1.6) |

| Exclusive breastfeeding, weeks | 5.9 (4.3) | 4.9 (4.3) |

| Age 0 months | ||

| Weight, kg | 3.5 (0.4) | 3.5 (0.5) |

| Length/height, cm | 51.4 (2.3) | 51.4 (2.6) |

| Body fat percentage | 13.9 (4.4) | 13.3 (5.5) |

| Age 3 months | ||

| Weight, kg | 6.1 (0.8) | 6.2 (0.8) |

| Length/height, cm | 61.2 (2.7) | 61.1 (2.6) |

| Body fat percentage | 23.5 (3.7) | 23.8 (3.5) |

| Age 24 months | ||

| Weight, kg | 12.6 (1.3) | 12.6 (1.5) |

| Length/height, cm | 87.8 (3.3) | 87.8 (3.5) |

| Body fat percentage | 32.6 (1.9) | 32.7 (2.0) |

| Childhood (5 to 11 years) | ||

| Age (years) | 9.5 (1.1) | 9.5 (1.1) |

| Weight, kg | 32.6 (7.0) | 32.9 (6.9) |

| Length/height, cm | 139.2 (8.9) | 138.8 (9.0) |

| Body fat percentage | 22.4 (7.9) | 23.5 (8.4) |

| CEBQ traitsa | ||

| Age (years) | 12.5 (1.5) | 13.0 (0.9) |

| Food responsiveness | 2.4 (0.8) | 2.5 (0.9) |

| Enjoyment of food | 4.0 (0.7) | 3.9 (0.7) |

| Emotional overeating | 1.9 (0.7) | 2.1 (0.7) |

| Desire to drink | 2.0 (0.7) | 2.1 (0.8) |

| Satiety responsiveness | 2.5 (0.7) | 2.5 (0.7) |

| Slowness in eating | 2.4 (0.8) | 2.4 (0.8) |

| Emotional undereating | 2.5 (0.7) | 2.6 (0.8) |

| Food fussiness | 2.5 (0.9) | 2.7 (1.0) |

CEBQ: Child Eating Behaviour Questionnaire; SD: standard deviation.

aCEBQ subscale scores in 411 children.

Correlations between the CEBQ traits among all children who collected such data (n = 411) are shown in Supplementary Table 1. The food-approach appetitive traits (food responsiveness, enjoyment of food, emotional overeating, and desire to drink) showed variable weak to moderate positive intercorrelations (r = 0.05 to 0.56) as did the food-avoidant appetitive traits (satiety responsiveness, slowness in eating, emotional undereating, and food fussiness) (r = 0.09 to 0.49). The correlations between the food-approach and food-avoidant appetitive traits were mostly negative, except for positive correlations between emotional overeating and emotional undereating (r = 0.36) and between desire to drink and emotional undereating (r = 0.17).

Associations between appetitive traits and growth velocities

Food-approach appetitive traits

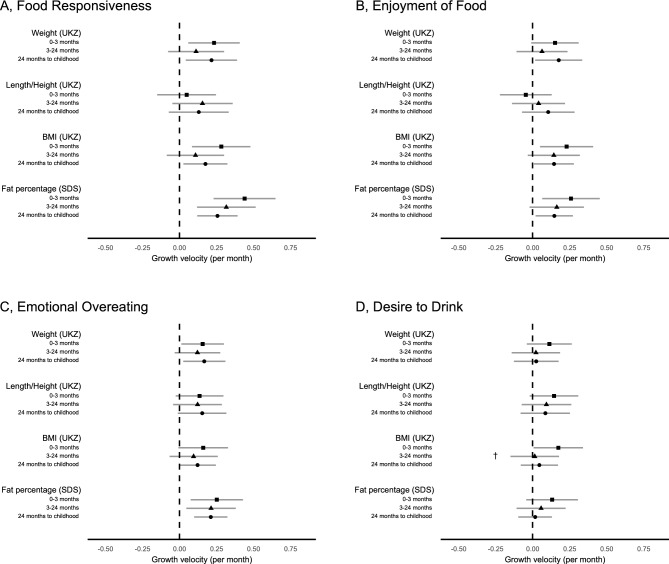

Figure 2 and Supplementary Table 2 show the associations between parent-perceived food-approach appetitive traits at 9–17 years old and growth velocities at different intervals from birth to childhood. Food responsiveness was positively associated with growth velocities in weight and BMI at 0–3 months (β = 0.23 UK z-score change/month for 1-unit increase in Likert scale, P = 0.009 and β = 0.28 UK z-score change/month, P = 0.005, respectively) and 24 months to childhood (β = 0.22 UK z-score change/month, P = 0.015 and β = 0.18 UK z-score change/month, P = 0.021, respectively), and in body fat percentage at all growth intervals. Enjoyment of food was positively associated with growth velocities in BMI and body fat percentage at 0–3 months and 24 months to childhood, and in weight at 24 months to childhood. Emotional overeating was positively associated with velocities in weight at 0–3 months and 24 months to childhood, and in body fat percentage at all ages. These food-approach appetitive traits showed no evidence of heterogeneity across the different growth periods (0–3 months, 3–24 months, and 24 months to childhood). Desire to drink showed no association with any growth velocity except with BMI only at 0–3 months.

Figure 2.

Associations between the food-approach appetitive traits (A, food responsiveness; B, enjoyment of food; C, emotional overeating; D, desire to drink) and individual-level growth velocities (UK z-score change/month for 1-unit increase in Likert scale) for weight, length/height, BMI, and (standard deviations of) body fat percentage. All models were adjusted for sex, age at the questionnaire completion, and birth measurements (weight, length/height, BMI, or body fat percentage). Error bars display the 95% confidence intervals of each estimate. †Associations with growth velocities at 0–3 months, 3–24 months, and 24 months to childhood (5 to 11 years) were statistically heterogenous (Wald test P < 0.05). UKZ, UK z-score; SDS, standard deviation score.

Food-avoidant appetitive traits

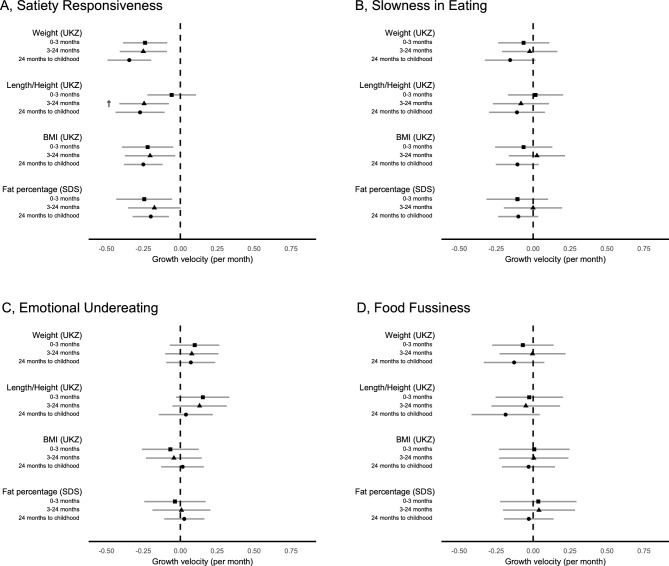

Figure 3 and Supplementary Table 3 show the associations between parent-perceived food-avoidant appetitive traits at 9–17 years old and growth velocities at different intervals from birth to childhood. Of the food-avoidant appetitive traits, only satiety responsiveness was negatively associated with velocities in weight (0–3 months: β = − 0.24 UK z-score change/month for 1-unit increase in Likert scale, P = 0.002; 3–24 months: β = − 0.25 UK z-score change/month, P = 0.002; 24 months to childhood: β = − 0.34 UK z-score change/month, P = 8 × 10–6) and BMI (0–3 months: β = − 0.22 UK z-score change/month, P = 0.013; 3–24 months: β = − 0.2 UK z-score change/month, P = 0.019; 24 months to childhood: β = − 0.25 UK z-score change/month, P = 2 × 10–4) at all ages, and in body fat percentage at 0–3 months and 24 months to childhood. Satiety responsiveness was also negatively associated with height velocity at 3–24 months and 24 months to childhood, but not at 0–3 months (Wald test P-heterogeneity = 0.047).

Figure 3.

Associations between the food-avoidant appetitive traits (A, satiety responsiveness; B, slowness in eating; C, emotional undereating; D, food fussiness) and individual-level growth velocities (UK z-score change/month for 1-unit increase in Likert scale) for weight, length/height, BMI, and (standard deviations of) body fat percentage. All models were adjusted for sex, age at the questionnaire completion, and birth measurements (weight, length/height, BMI, or body fat percentage). Error bars display the 95% confidence intervals of each estimate. †Associations with growth velocities at 0–3 months, 3–24 months, and 24 months to childhood (5 to 11 years) were statistically heterogenous (Wald test P < 0.05). UKZ, UK z-score; SDS, standard deviation score.

Discussion

In this study, we modelled associations between parent-reported food-approach and food-avoidant appetitive traits with objectively measured growth velocities at different time points across child development. Consistent with previous research, we showed that the food-approach appetitive traits (i.e. food responsiveness, enjoyment of food, and emotional overeating) were positively associated with gains in weight, BMI, and body fat percentage at most ages. These relationships were not seen for length or child height. Furthermore, the food-avoidant appetitive traits (i.e. satiety responsiveness) showed negative associations with most growth velocities. The associations with growth velocities were predominantly consistent in effect size across infancy and childhood.

Our findings are consistent with previous reports, which showed that greater expression of food responsiveness and lower satiety responsiveness were associated with higher weight gain in infancy18, 19 and higher BMI in childhood12, 14, 15, 20. Although appetite and satiety are partially controlled by neurologically dissociable systems, there is a considerable interplay between the two11. This is supported by the negative correlations between some food-approach and food-avoidant traits in our study and also in previous reports2, 30, 31. The positive association between enjoyment of food with gains in BMI seen in our study is consistent with findings of an earlier systematic review that investigated prospective associations between enjoyment of food with BMI z-score and percentile21. This aligns with previous research showing that appetitive traits are considered to be innate predispositions, which in obesogenic environments elevates the risk for rapid weight gain21, 22.

Consistent with some earlier longitudinal studies11, 13, 14, emotional overeating was positively associated with BMI gains, however emotional undereating showed no association with any growth velocity. Despite their different patterns of association with obesity, emotional overeating and emotional undereating were positively correlated, which aligns with previous data2, 32, 33. Both traits indicate eating behaviour reactions to emotions, usually negative emotions such as stress or sadness32, 34.

To our knowledge, the associations between the CEBQ traits and body fat percentage are rarely explored. We found appetitive traits had stronger associations with body fat percentage compared to other anthropometric measures. We observed associations of food responsiveness, enjoyment of food, and emotional overeating (all food-approach traits) and satiety responsiveness (a food-avoidant trait) with changes in body fat percentage. This might suggest that prior studies employing BMI instead of adiposity measures could potentially have underestimated the associations with appetitive traits. Furthermore, these findings could indicate a distinct connection between appetitive traits and adiposity, as opposed to overall body size and growth. There is indirect support for this hypothesis from other studies that reported links between food responsiveness and liking of non-core foods, which tend to be of higher caloric density35, 36, and between emotional eating with intakes of palatable energy-dense foods37 and sugar-sweetened drinks38. The strong association between appetitive traits and body fat percentage underscores the potential of using eating behaviour as a tool to differentiate between lean mass and fat mass in the context of childhood obesity.

A key insight in the present study is associations between appetitive traits and growth from infancy to childhood. Although previous longitudinal studies showed similar findings on the association between eating behaviour and growth during infancy or childhood11–20, none has investigated relationships spanning both age periods. Our findings suggest a broadly consistent link between appetitive traits and various dimensions of growth across both infancy and childhood. This highlights the potential of using appetitive traits for predicting childhood obesity.

We found that slowness in eating and food fussiness were not associated with growth velocity. This differs from the systematic review and meta-analysis by Kininmonth et al., which reported that slowness in eating was consistently negatively associated with adiposity whereas food fussiness showed null associations21. It may be relevant to note that, in general, slowness in eating declines with age in longitudinal studies, as children become more proficient at eating3, and we administered the CEBQ at relatively older ages than other studies. The food-avoidant trait food fussiness indicates the innate tendency to be selective about the foods a child is willing to try, often focusing on attributes such as texture or presentation39. It tends to be most pronounced during late infancy and then reduces with age as a result of repeated exposure to foods39.

We acknowledge several limitations in our study. First, we administered the CEBQ at only one time point that spanned a wide range of ages, and after the growth measurements. This is challenging as appetitive traits are to some extent dynamic and the age at CEBQ measurement influences the interpretation of the observed relationships. Furthermore, the CEBQ has not been validated in older children (> 14 years of age). However, there is evidence that childhood appetitive traits track and show stability from infancy to childhood3–5. Moreover, as children mature and attain increased autonomy in their food choices, their ability to express genetic predisposition for heightened appetite might become more evident10. Secondly, the single measurement of appetitive traits limited our ability to assess their likely causal direction with growth. One key area of research in this field relates to better understating the bidirectionality between eating behaviour and adiposity21. However, due to the single CEBQ measurement, the results presented in this study are not able to disentangle directionality of the observed consistent associations. Furthermore, most children in this study were of White European origin and were recruited from a single center, which may reduce generalizability. That being said, the growth parameters of the CBGS sample were comparable to the UK population-based growth references29. A key strength of our study was the comprehensive range of anthropometric indicators included in the analyses, including four skinfolds and DEXA scans. This allows for a more objective understanding of the link between eating behaviours and adiposity development. These growth data have been shown to have low relative intra-observer technical errors of measurements40. Lastly, the CEBQ was parent-reported, and parental perceptions and social desirability bias need to be taken into account.

Conclusions

This study shows positive and negative associations of food-approach and food-avoidant appetitive traits at 9–17 years with growth velocities from birth to childhood, respectively. Given the potentially stable appetitive traits suggested by several studies, this study suggests the relevance of appetitive traits to growth velocities of adiposity-related traits, demonstrating broadly consistent relationships from infancy to childhood. Future research is necessary to determine the potential of mitigating the effects of appetitive traits in reducing risk for childhood obesity.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all the families who contributed to the study. The authors acknowledge the CBGS research nurses Suzanne Smith, Ann-Marie Wardell, and Karen Forbes, Department of Paediatrics, University of Cambridge. We are also very grateful to the midwives at the Rosie Maternity Hospital, Cambridge, and the staff at the NIHR-Wellcome Trust Clinical Research Facility, Cambridge, for their support. For the purpose of Open Access, the author has applied a Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) licence to any Author Accepted Manuscript version arising.

Abbreviations

- BEBQ

Baby Eating Behaviour Questionnaire

- BMI

Body mass index

- CBGS

Cambridge Baby Growth Study

- CEBQ

Children’s Eating Behaviour Questionnaire

- DEXA

Dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry

- FFMI

Fat-free mass index

- FMI

Fat mass index

- SF

Skinfold

Author contributions

F.R.D., D.I.O., K.K.O., and A.S. conceptualized and designed the study, interpreted analyses, and reviewed and revised the manuscript; I.A.H., L.O., and C.J.P. designed the data collection instruments, coordinated and supervised data collection, and reviewed and revised the manuscript; T.S.C. conducted data verification steps and data analyses, assisted with interpretation of analyses and reviewed and revised the manuscript; and all authors approved the submitted manuscript and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

The CBGS has been funded by the Medical Research Council (7500001180, G1001995), European Union Framework 5 (QLK4-1999-01422), the Mothercare Charitable Foundation (RG54608), Newlife Foundation for Disabled Children (07/20), and the World Cancer Research Fund International (2004/03). This research was also supported by the National Institute for Health Research/Wellcome Trust Clinical Research Facility at Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust and the NIHR Cambridge Comprehensive Biomedical Research Centre. DO, FD, TSC, AS and KO are supported by the Medical Research Council (Unit programmes MC_UU_00006/2 and MC_UU_00006/5). DO is also supported by a PhD studentship from the King Abdullah International Medical Research Center (KAIMRC), the Ministry of National Guard Health Affairs. The sponsors had no role in the study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, the writing of the manuscript or the decision to submit it for publication.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-023-42899-0.

References

- 1.Reilly JJ, Kelly J. Long-term impact of overweight and obesity in childhood and adolescence on morbidity and premature mortality in adulthood: Systematic review. Int. J. Obes. 2011;35(7):891–898. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2010.222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wardle J, Guthrie CA, Sanderson S, Rapoport L. Development of the Children’s Eating Behaviour Questionnaire. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry. 2001;42(7):963–970. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ashcroft J, Semmler C, Carnell S, van Jaarsveld CHM, Wardle J. Continuity and stability of eating behaviour traits in children. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008;62(8):985–990. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Birch L, Savage JS, Ventura A. Influences on the development of Children’s Eating Behaviours: From infancy to adolescence. Can. J. Diet Pract. Res. Publ. Dietit Can. Rev. Can. Prat. Rech. En Diet Une Publ. Diet Can. 2007;68(1):s1–56. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jansen E, Thapaliya G, Beauchemin J, D’Sa V, Deoni S, Carnell S. The development of appetite: Tracking and age-related differences in appetitive traits in childhood. Nutrients. 2023;15(6):1377. doi: 10.3390/nu15061377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Archer LA, Rosenbaum PL, Streiner DL. The Children’s Eating Behavior Inventory: Reliability and validity results. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 1991;16(5):629–642. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/16.5.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Strien T, Oosterveld P. The children’s DEBQ for assessment of restrained, emotional, and external eating in 7- to 12-year-old children. Int. J. Eat Disord. 2008;41(1):72–81. doi: 10.1002/eat.20424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Llewellyn CH, van Jaarsveld CHM, Johnson L, Carnell S, Wardle J. Nature and nurture in infant appetite: Analysis of the Gemini twin birth cohort. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010;91(5):1172–1179. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.28868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Warkentin S, Severo M, Fildes A, Oliveira A. Genetic and environmental contributions to variations on appetitive traits at 10 years of age: A twin study within the Generation XXI birth cohort. Eat Weight Disord. Stud. Anorex Bulim Obes. 2022;27(5):1799–1807. doi: 10.1007/s40519-021-01322-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Llewellyn C, Wardle J. Behavioral susceptibility to obesity: Gene–environment interplay in the development of weight. Physiol. Behav. 2015;1(152):494–501. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2015.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Derks IPM, Sijbrands EJG, Wake M, Qureshi F, van der Ende J, Hillegers MHJ, et al. Eating behavior and body composition across childhood: A prospective cohort study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2018;15(1):96. doi: 10.1186/s12966-018-0725-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Steinsbekk S, Wichstrøm L. Predictors of change in BMI from the age of 4 to 8. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2015;40(10):1056–1064. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsv052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Power TG, Hidalgo-Mendez J, Fisher JO, O’Connor TM, Micheli N, Hughes SO. Obesity risk in Hispanic children: Bidirectional associations between child eating behavior and child weight status over time. Eat Behav. 2020;1(36):101366. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2020.101366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parkinson KN, Drewett RF, Le Couteur AS, Adamson AJ, Gateshead Milennium Study Core Team Do maternal ratings of appetite in infants predict later Child Eating Behaviour Questionnaire scores and body mass index? Appetite. 2010;54(1):186–190. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2009.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mallan KM, Nambiar S, Magarey AM, Daniels LA. Satiety responsiveness in toddlerhood predicts energy intake and weight status at four years of age. Appetite. 2014;74:79–85. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2013.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Barse LM, Tiemeier H, Leermakers ETM, Voortman T, Jaddoe VWV, Edelson LR, et al. Longitudinal association between preschool fussy eating and body composition at 6 years of age: The Generation R Study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2015;12(1):153. doi: 10.1186/s12966-015-0313-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Costa A, Severo M, Vilela S, Fildes A, Oliveira A. Bidirectional relationships between appetitive behaviours and body mass index in childhood: A cross-lagged analysis in the Generation XXI birth cohort. Eur. J. Nutr. 2020;60:239–247. doi: 10.1007/s00394-020-02238-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Jaarsveld CHM, Llewellyn CH, Johnson L, Wardle J. Prospective associations between appetitive traits and weight gain in infancy. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011;94(6):1562–1567. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.111.015818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Jaarsveld CHM, Boniface D, Llewellyn CH, Wardle J. Appetite and growth: A longitudinal sibling analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(4):345–350. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.4951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Quah PL, Chan YH, Aris IM, Pang WW, Toh JY, Tint MT, et al. Prospective associations of appetitive traits at 3 and 12 months of age with body mass index and weight gain in the first 2 years of life. BMC Pediatr. 2015;15(1):153. doi: 10.1186/s12887-015-0467-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kininmonth A, Smith A, Carnell S, Steinsbekk S, Fildes A, Llewellyn C. The association between childhood adiposity and appetite assessed using the Child Eating Behavior Questionnaire and Baby Eating Behavior Questionnaire: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes. Rev. Off. J. Int. Assoc. Study Obes. 2021;22(5):e13169. doi: 10.1111/obr.13169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Llewellyn CH, Kininmonth AR, Herle M, Nas Z, Smith AD, Carnell S, et al. Behavioural susceptibility theory: The role of appetite in genetic susceptibility to obesity in early life. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 1885;2023(378):20220223. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2022.0223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rothman KJ. BMI-related errors in the measurement of obesity. Int. J. Obes. 2008;32(3):S56–S59. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jalkanen H, Lindi V, Schwab U, Kiiskinen S, Venäläinen T, Karhunen L, et al. Eating behaviour is associated with eating frequency and food consumption in 6–8 year-old children: The Physical Activity and Nutrition in Children (PANIC) study. Appetite. 2017;1(114):28–37. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2017.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.da Costa MP, Severo M, Oliveira A, Lopes C, Hetherington M, Vilela S. Longitudinal bidirectional relationship between children’s appetite and diet quality: A prospective cohort study. Appetite. 2022;1(169):105801. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2021.105801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Olga L, van Beijsterveldt IALP, Hughes IA, Dunger DB, Ong KK, Hokken-Koelega ACS, et al. Anthropometry-based prediction of body composition in early infancy compared to air-displacement plethysmography. Pediatr. Obes. 2021;n/a(n/a):e12818. doi: 10.1111/ijpo.12818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ong KK, Cheng TS, Olga L, Prentice PM, Petry CJ, Hughes IA, et al. Which infancy growth parameters are associated with later adiposity? The Cambridge Baby Growth Study. Ann. Hum. Biol. 2020;47(2):142–149. doi: 10.1080/03014460.2020.1745887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Body mass index reference curves for the UK, 1990. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1511150/ (Accessed 13 July 2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Cole TJ, Freeman JV, Preece MA. British 1990 growth reference centiles for weight, height, body mass index and head circumference fitted by maximum penalized likelihood. Stat. Med. 1998;17(4):407–429. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19980228)17:4<407::AID-SIM742>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Viana V, Sinde S, Saxton JC. Children’s Eating Behaviour Questionnaire: Associations with BMI in Portuguese children. Br. J. Nutr. 2008;100(2):445–450. doi: 10.1017/S0007114508894391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Steinsbekk S, Llewellyn CH, Fildes A, Wichstrøm L. Body composition impacts appetite regulation in middle childhood. A prospective study of Norwegian community children. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017;14(1):70. doi: 10.1186/s12966-017-0528-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Herle M, Fildes A, Steinsbekk S, Rijsdijk F, Llewellyn CH. Emotional over- and under-eating in early childhood are learned not inherited. Sci. Rep. 2017;7(1):9092. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-09519-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sleddens EF, Kremers SP, Thijs C. The children’s eating behaviour questionnaire: Factorial validity and association with Body Mass Index in Dutch children aged 6–7. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2008;20(5):49. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-5-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Herle M, Fildes A, Llewellyn CH. Emotional eating is learned not inherited in children, regardless of obesity risk. Pediatr. Obes. 2018;13(10):628–631. doi: 10.1111/ijpo.12428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fildes A, Mallan KM, Cooke L, van Jaarsveld CH, Llewellyn CH, Fisher A, et al. The relationship between appetite and food preferences in British and Australian children. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2015;12(1):116. doi: 10.1186/s12966-015-0275-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Russell CG, Worsley T. Associations between appetitive traits and food preferences in preschool children. Food Qual. Prefer. 2016;1(52):172–178. doi: 10.1016/j.foodqual.2016.04.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nguyen-Michel ST, Unger JB, Spruijt-Metz D. Dietary correlates of emotional eating in adolescence. Appetite. 2007;49(2):494–499. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Elfhag K, Tynelius P, Rasmussen F. Sugar-sweetened and artificially sweetened soft drinks in association to restrained, external and emotional eating. Physiol. Behav. 2007;91(2–3):191–195. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smith AD, Herle M, Fildes A, Cooke L, Steinsbekk S, Llewellyn CH. Food fussiness and food neophobia share a common etiology in early childhood. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry. 2017;58(2):189–196. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Prentice P, Acerini CL, Eleftheriou A, Hughes IA, Ong KK, Dunger DB. Cohort profile: The Cambridge Baby Growth Study (CBGS) Int. J. Epidemiol. 2016;45(1):35–35g. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyv318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.