Abstract

Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) is one of the leading causes of disability affecting more than 340 million people and second largest contributor to global burden of disease. Chronic stress is a common risk factor and important contributor for MDD. Stress could be defined as the “perceived inability to cope”. Stressful life events are shown to provoke a sequence of psychological and physiological adjustments including nervous, endocrine and immune mechanisms. Stress can lead to elevation of a variety of inflammatory cytokines and stress hormones, can cause autonomic dysfunction and imbalance in neurotransmitters. Yoga can reduce depressive symptoms by alleviating stress. Studies have shown that yoga can reduce inflammation, maintain autonomic balance and also has a role in maintaining the neurotransmitters. It has role on hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, the peripheral nervous system including GABA, limbic system activity, inflammatory and endocrine responses. Yoga along with antidepressants can help in reducing the depressive symptoms in patient with MDD. Yoga is an ideal complementary and alternative therapy for mental health disorders.

Keywords: Stress, Yoga, Depression, Mental health, CAM, Meditation

1. Introduction

Stress is a normal, universal human experience and is being practiced for many years. Stress is broadly defined as “the nonspecific response of the body to any demand”. Eustress or good stress is the stress that benefits our health (eg., Physical exercise, getting first mark in exams, getting promotions in workplace). Distress or bad stress is the stress that harms the health which often results from imbalances between needs and resources for dealing with those needs [1].

Intensity and duration of stress differs from one person to another. The performance may be affected if there is insufficient amount of stress(meaning lower motivation or boredom). However symptoms of stress that are sustained for a longer duration can be detrimental leading to lethargy, lack of confidence, and disturbed sleep [2]. When stress levels are too high, it could lead to mental health issues such as depression and anxiety, as well as behavioural changes which includes increased alcohol consumption, drug abuse, and eating disorders. It also causes many medical consequences like: gastrointestinal disorders, headaches, cardiac disorders, musculoskeletal weakness, etc [3]. Behavioural coping strategies are those which denotes the different strategies that an individual might apply while experiencing a stressful situation [4]. Coping denotes the method of dealing problems to get rid of negative emotions which allows us to maintain control of our emotions to present conditions and demands. Psychological stress can clearly trigger a depressive episode, especially when the psychological impact of a stressor exceeds the coping ability of the individual [5]. Yoga is one of the most beneficial coping strategies for reducing stress, through release of neurochemicals in the brain. Breathing exercises which could be as simple as a simple deep breath concentration to advanced breathing practices which makes one to perceive the effects of meditation, induces complete relaxation [6]. This review article focuses on the pathophysiological mechanism of stress and depression, and the role of yoga in reducing stress and depression.

2. Pathophysiology of stress and depression

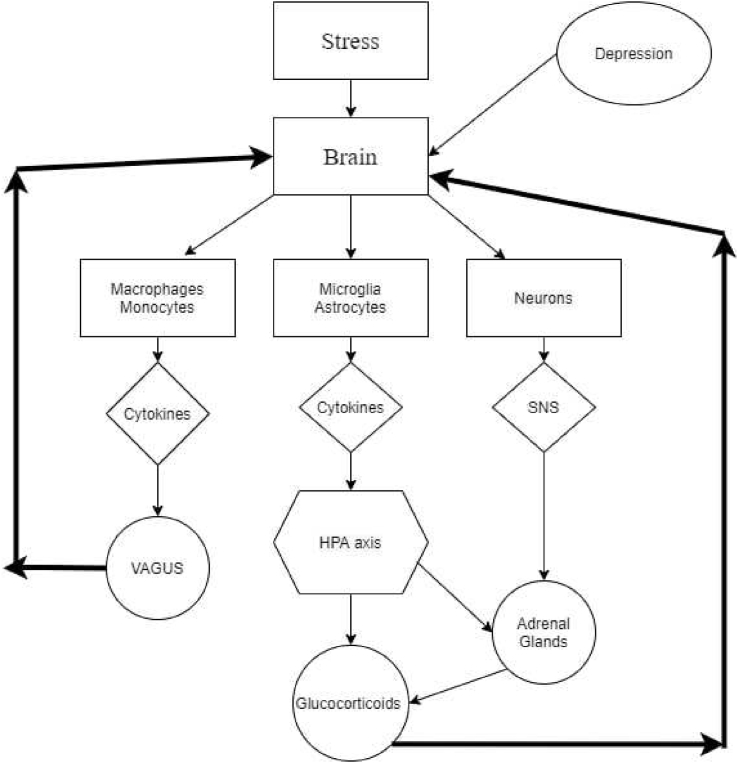

Stressful life events are shown to provoke a sequence of psychological and physiological adjustments including nervous, endocrine and immune mechanisms [7]. Stimulation of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, activation of Sympathetic Nervous System (SNS) and initiation of cascade of inflammatory responses are some of the well-recognized effects of stress [8]. Stress causes higher cortical areas to send impulses to hypothalamus via limbic system. Certain areas of Para Ventricular Nucleus (PVN) are activated to release Corticotrophin Releasing Factor (CRF) [9]. Meanwhile additional neurotransmitters like serotonin, Nor-epinephrine (NE), and Acetylcholine (Ach) are released into the blood stream. CRF acts on corticotrophs and PVN to produce Proopiomelanocortin (POMC) and Arginine Vasopressin (AVP) respectively. POMC eventually divides to produce Adreno Cortico Tropic Hormone (ACTH) and alpha Melanocyte Stimulating Hormone (α-MSH) [10]. AVP acts synergistically with CRF stimulating excess release of ACTH, which ultimately acts on adrenal cortex to produce Glucocorticoids (GC) [11]. SNS releases Catecholamines (CC) into circulation at the same time. Therefore, GCs and CCs are the main stress hormones which impact several aspects of the brain functions including formation and endurance of neurons, size of the hippocampus, metabolism and immunity [11]. Even though, there is no obvious documented evidence about the neural mechanisms involved in the pathogenesis of depression due to stress, the various symptoms of depression suggest that areas such as hippocampus, prefrontal lobe, amygdala, thalamus, corpus striatum and cingulate cortex may be involved very commonly [12]. Chronic stress is shown to trigger inflammatory responses as well, thereby altering physical and mental health. Fig. 1 shows the interaction between stress, brain, HPA axis, SNS and inflammatory cytokines [13].

Fig. 1.

Pathophysiological mechanisms of stress.

It is well-known that stress responses in the body leads to the release of cytokines such as interleukin-6 (IL-6), interleukin-1β (IL-1β), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) which are already proved to produce depression symptoms [14]. These inflammatory markers may affect various functions of central nervous system (CNS) resulting in sleep disturbance, cognitive decline, reduction of monoamine levels all of which collectively aggravate the manifestation of depression [15]. In addition, IL-1β is shown to control the expression of genes related to serotonin transport, IL-6 is capable of neuronal inhibition of hippocampus and TNF-α has the potential to induce pathways which catabolize tryptophan, the primary substrate for serotonin formation [16]. Advanced research in this field may reveal newer neuronal pathways linking the stress induced cytokines with somatic and behavioral effects of depression.

A major downstream consequence of MDD is elevated glucocorticoid (the most important of these being cortisol) levels, which are present in the majority of depressed individuals but not all [17]. High cortisol levels may be particularly harmful alongside elevated levels of inflammatory cytokines, which inhibit the action of cortisol by downregulating cortisol receptor activity [17]. High cortisol levels may directly contribute to cell damage and death in a variety of cell types, including hippocampal cells, in part by impairing effective regulation of cellular glutamate [18]. Unmedicated depressives display low levels of neurosteroids, including GABA-A, DHEA, and allopregnanolone; treatment and remission of depression restores normal levels. Stress (which, as you saw, produces powerful hormones like glucocorticoids into the blood) appears to diminish the levels of BDNF generated in the hippocampus by disrupting neurons in the hippocampus, according to experimental research. ADM therapy appears to prevent or reverse this decrease in BDNF levels [19].

3. Mechanisms of stress management through Yoga

Yoga plays a beneficial role to manage stress related mental illness like depression and anxiety. Regular practice of yoga promotes physiological changes such as reducing blood glucose, blood pressure and cortisol levels and improves general wellbeing [20,21]. Depression is a psycho-physiological disorder which majorly involves alteration in the monoamine (noradrenaline, serotonin, dopamine) metabolism [22]. Central neurotransmitters such as gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) play an important role in depression as well. There are multiple mechanisms through which yoga helps in the management of depression. Yoga is mind-body medicine widely found to be beneficial in various psycho-somatic disorders. Yoga includes physical postures, breathing practices, meditation and also moral principles (yama & niyama) which helps in emotional culturing to reduce inner conflicts [23]. According to a recent review of yoga's effect on stress, a yoga intervention resulted in a significant reduction in stress [24].

Numerous biological mechanisms suggested that yoga may reduce stress which include the Autonomic nervous system (ANS), HPA axis, the peripheral nervous system including GABA, limbic system activity, endocrine functions and inflammatory responses [25]. Previous literature reveals the possible effects of yoga on endothelial function, release of nitric oxide, endogenous cannabinoids, opiates and gene expression [26]. Yoga is suggested to have immediate and beneficial effects on baroreflex sensitivity and heart rate variability (HRV), which has a stimulating effect on vagal nerve [[27], [28], [29]]. It decreases vagal stimulation, which decreases the activation and reactivity of the sympathoadrenal system and the HPA axis and that leads to parasympathetic activation, thus shifting of sympathetic to parasympathetic activity occurs, and also decreases the release of stress hormones.

Yoga shifts the balance from the sympathetic nervous system and the fight–or–flight reaction to the parasympathetic nervous system and the relaxation response [30]. Yoga practice regulates the HPA axis and SNS, both of which could be the reasons for the reduction of stress hormones cortisol and catecholamines release and leads to the reduction of stress and induces relaxation [31].

3.1. Corticosteroids and catecholamines

Yoga acts on hypothalamus which inhibits the activity of the anterior pituitary gland and decreases the production of ACTH, this reduction in ACTH production affects the adrenal gland and reduces the synthesis of cortisol. Many studies have observed this decrease in cortisol levels after practicing yoga [32], whereas Cortisol activates phenyl ethanolamine-N-methyl transferase (PNMT). Decrease in cortisol production after yoga practices simultaneously decreases PNMT. This decrease in PNMT along with sympathetic inhibition also decreases catecholamine formation. Thus the decreased levels of corticosteroids and catecholamines together decreases the stress responses [33].

3.2. Dopamine

Practicing yoga increases the levels of dopamine in the human body. Another study confirmed that, 11C–raclopride binding in ventral striatum decreased by 7.9% while practicing yogic meditation which corresponds to a 65% increase in endogenous dopamine release [34]. Increase in dopamine release concomitantly decreases the stress level.

3.3. Serotonin

The “serotonin hypothesis” denotes that the diminished activity of serotonin pathways leads to the pathophysiology of depression. Increasing serotonin activity in depressed individuals promotes positive shifts in automatic emotional responses [35]. Yogic practices have been proved to increase the plasma levels of Serotonin [36]. Regular yogic practices increase serotonin levels associated with reductions in monoamine oxidase levels, which is an enzyme that breaks down neurotransmitters and cortisol and thus reduces stress.

3.4. Melatonin

Melatonin is a regulatory circadian hormone which has a hypnotic and an antidepressive effect [37]. Meditation has been shown to boost melatonin levels by decreasing its hepatic metabolism or increasing its production in the pineal gland [37]. Thus, yoga reduces stress.

3.5. Noradrenaline

Yoga practices are proved to enhance noradrenalin and decreases the plasma levels of adrenalin which in turn reduces stress [38].

3.6. Inflammatory markers

Yoga reduces inflammatory markers such as NK cells, IL 6 and TNF-α and hs-CRP [39]. According to previous study, yogic meditation reduces the activity of NF–B-related transcription of pro-inflammatory cytokines and decreases the transcription of innate antiviral response genes by Interferon Response Factors (IRF1), both of which are regarded important stresses.

3.7. BDNF

Yogic practices increases the levels of BDNF in the human body. Improvements in BDNF levels after yoga practise may be related to lower stress levels, as evidenced by lower cortisol levels, and improved HRV parameters [40].

3.8. Gene expression

Regular yogic practices have an effect at the molecular level [41] and it modifies gene expression positively [42].

3.9. Sirtuins

There is a relationship between the Sirtuin1 gene (rs3758391) and depressive disorders, according to studies, and Sirt1 expression in the peripheral blood of depressed people is much lower than in healthy people [43,44]. By activating SIRT1, The progress of depression-related phenotypes and aberrant dendritic architecture caused by persistent stress exposure will be prevented [45]. According to previous reports, activating Sirt1 may improve mood function and have an antidepressant impact [46]. Researchers have proved that the yoga and meditation-based lifestyle increases sirtuin-1 levels and hence serve the purpose of producing antidepressive effects and reducing stress [41].

3.10. Proposed psychological mechanism

Psychological mechanisms of the effects of yoga on stress and depressive symptoms has been proved to improve self - awareness, positive attitude towards stress, calmness and mindfulness [25]. Yoga slows the breath, helps to focus on the present and reassure relaxation, slow the breath and focus on the present. It improves self-confidence, attentiveness, relaxing sensations, well-being sensations, an optimistic outlook on life, achieves tranquility of the mind and lowers irritability [47]. Patanjali's Yoga sutras is one of the traditional texts which mentions depression (dhaurmanasya) as one of the important distractions of the mind (chitta vikshepa) and is considered as an obstacles in the path of yoga [48]. Sage Patanjali mentions many ways to overcome the mental distractions and first of which is one-pointedness (eka tattwa abhyasa) which is applied in both pranayama, concentration (dharana) and meditation [49].

Yoga induces relaxation by reducing physiological excitement which is most helpful in coping emotional stress [50]. It has been indicated that simple breathing and concentration techniques, are the two important modules of yoga, which can support individuals mentally manage with stress that permits enormous health benefits. As a result, Yogic breathing practises serve as a link between the mind and the body, and can be viewed as an important element in one's everyday life for cultivating mindfulness [51]. Yoga is the ultimate skill to calm down mind, says the traditional text of Yog Vashishta (mana prashamanopayah yoga ityabhidhiyate) and this is achieved through various techniques, such as practicing the principles of yama/niyama and through yogic breathing techniques for coping with stressors in a better manner, better perception of stress and reducing stress & stress-related illness [49]. Mindfulness techniques involve self-awareness, self-control, self-encouragement, without avoidance, judgement, or self-criticism, to recognize and sustain stressors as they are [52]. Yogic techniques enhance well-being, mood, attention, mental focus, and stress tolerance [53]. For depression and anxiety disorders, Mindful meditation and Yoga has been proved to have positive effects [54].

Individuals are advised to concentrate on their breathing patterns throughout the practice without any distractions. This mindfulness helps the practitioners to be aware of the present and won't be affected or disturbed by the past incidents [55]. It is evident that deep yogic breathing has many functional benefits, which in turn regulates the imbalances in the ANS and thus alleviates stress by stimulating parasympathetic activity [56].

4. Studies on yoga & depression

A randomized control trial (RCT) comparing yoga with usual conventional treatment for a period of six weeks showed a substantial decrease in the depression scores when matched to control group [57]. Another study done in major depressive disorder (MDD) of mild to moderate severity found yoga to have greater reduction in symptoms when compared to control group and were also more likely to achieve remission [58]. A study done in older women also proved that there was a reduction in depression and anxiety symptoms [59]. A RCT done in college students, observed a significant improvement in depression and anxiety symptoms compared to the control group. But interestingly, the comparison between yoga and meditation did not show any significant difference between each other [60]. Likewise, another study done in pregnant women with depression and anxiety, showed significant reduction in the depression scores [61]. A RCT comparing yoga with usual treatment in women with breast cancer showed a significant improvement in the state and trait anxiety in the yoga group [62]. Yoga was also observed to be effective in reducing depression scores in women with premenstrual syndrome [63]. In patients with depression, yoga was found to increase plasma serotonin levels [65]. Brain imaging studies have also documented that yoga increases the release of endogenous dopamine in the ventral striatum and also an increase in the thalamic GABA levels [64]. Another mechanism through which yoga might probably help depression is through correcting the dysregulation of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis which is commonly observed in depression [65]. Depression is also associated with increased cortisol levels which decreases to normal levels after effective yoga treatment [66]. Studies have reported that yoga could reduce subjective stress and levels of both plasma cortisol levels & salivary cortisol [67]. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis article has highlighted the positive effects of yoga in reduction of depressive symptoms in a dose -response manner [68].

5. Recognition of yoga

The United Nations General Assembly has recognized the overall advantages of yoga and its natural connection with the UN's objectives and values by declaring June 21 as International Yoga Day. National Mental health Policy in Vision 2014 has highlighted the importance of Indigenous system of medicine in management of mental health disorder and increase the therapeutic choice. AYUSH clinics are now a part of the hospitals Government is also building research capacities by providing research funds through DST- SATYAM, ICMR and AYUSH funding agencies. Yoga is now included in the school and college curriculum [69].

6. Discussion

Stress is defined as “perceived inability to cope”. Stress and MDD are associated with elevation of a variety of inflammatory cytokines, stress hormones and imbalance in neurotransmitters. Yoga is an ideal complementary therapy for mental health disorders. Yoga is a complex and holistic system that encompasses (i) physical postures to promote strength and flexibility; (ii) breathing exercises to enhance respiratory functioning; (iii) deep relaxation techniques to reduce mental and physical tension; (iv) meditation and mindfulness practices to increase mind–body awareness and (v) enhanced emotion regulation skills through the practice of yama and niyama. The COVID-19 pandemic has increased stress related disorders and depression in recent times, hence the need of the day is to have an integrated therapeutic and preventive approach of allopathy with complementary and alternative medicine. Yoga could be a good complementary and alternative treatment modality for Major Depressive Disorder.

Consent for publication

All the authors consent for publication and have submitted the copyright form.

Availability of data and materials

This is a review paper and content is taken from the approved scientific literatures.

Funding

Nil.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgement

Authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the Management of SRIHER, Chennai and Government College of Yoga and Naturopathy, Chennai.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Transdisciplinary University, Bangalore.

References

- 1.Selye H. Confusion and controversy in the stress field. J Hum Stress. 1975;1(2):37–44. doi: 10.1080/0097840X.1975.9940406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lundberg U. Stress, subjective and objective health. Int J Soc Welfare. 2006;15:S41–S48. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davidson J.R.T. Long-term treatment and prevention of posttraumatic stress disorder. J Clin Psychiatr. 2004;65:44–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ursin H., Eriksen H.R. The cognitive activation theory of stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2004;29(5):567–592. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4530(03)00091-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mikkelsen S., Coggon D., Andersen J.H., Casey P., Flachs E.M., Kolstad H.A., et al. Are depressive disorders caused by psychosocial stressors at work? A systematic review with metaanalysis. Eur J Epidemiol. 2021 May;36:479–496. doi: 10.1007/s10654-021-00725-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuppusamy M., Kamaldeen D., Pitani R., Amaldas J., Shanmugam P. Effects of Bhramari Pranayama on health–a systematic review. J Tradit Complement Med. 2018;8(1):11–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcme.2017.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang L., Zhao Y., Wang Y., Liu L., Zhang X., Li B., et al. The effects of psychological stress on depression. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2015;13(4):494–504. doi: 10.2174/1570159X1304150831150507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Engelmann M., Landgraf R., Wotjak C.T. The hypothalamic–neurohypophysial system regulates the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis under stress: an old concept revisited. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2004;25(3–4):132–149. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2004.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Souza E.B., Grigoriadis D.E. Neuropsychopharmacology: the fifth generation of progress. Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins; Philadelphia: 2002. Corticotropin-releasing factor: physiology, pharmacology, and role in central nervous system disorders; pp. 91–107. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hasan K.M., Rahman M.S., Arif K.M., Sobhani M.E. Psychological stress and aging: role of glucocorticoids (GCs) Age. 2012;34(6):1421–1433. doi: 10.1007/s11357-011-9319-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pariante C.M., Lightman S.L. The HPA axis in major depression: classical theories and new developments. Trends Neurosci. 2008;31(9):464–468. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2008.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Opel N., Redlich R., Zwanzger P., Grotegerd D., Arolt V., Heindel W., et al. Hippocampal atrophy in major depression: a function of childhood maltreatment rather than diagnosis? Neuropsychopharmacology. 2014;39(12):2723–2731. doi: 10.1038/npp.2014.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leonard B.E. Inflammation and depression: a causal or coincidental link to the pathophysiology? Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2018;30(1):1–16. doi: 10.1017/neu.2016.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu Y., Ho R.C.-M., Mak A. Interleukin (IL)-6, tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and soluble interleukin-2 receptors (sIL-2R) are elevated in patients with major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis and meta-regression. J Affect Disord. 2012;139(3):230–239. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karrenbauer B.D., Müller C.P., Ho Y.J., Spanagel R., Huston J.P., Schwarting R.K., et al. Time-dependent in-vivo effects of interleukin-2 on neurotransmitters in various cortices: relationships with depressive-related and anxiety-like behaviour. J Neuroimmunol. 2011;237(1–2):23–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2011.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dantzer R., O’connor J.C., Freund G.G., Johnson R.W., Kelley K.W. From inflammation to sickness and depression: when the immune system subjugates the brain. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9(1):46–56. doi: 10.1038/nrn2297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zunszain P.A., Anacker C., Cattaneo A., Carvalho L.A., Pariante C.M. Glucocorticoids, cytokines and brain abnormalities in depression. Prog Neuro Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatr. 2011;35(3):722–729. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2010.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim E.J., Pellman B., Kim J.J. Stress effects on the hippocampus: a critical review. Learn Mem. 2015;22(9):411–416. doi: 10.1101/lm.037291.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Warner-Schmidt J.L., Duman R.S. Hippocampal neurogenesis: opposing effects of stress and antidepressant treatment. Hippocampus. 2006;16(3):239–249. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Venugopal V., Geethanjali S., Poonguzhali S., Padmavathi R., Mahadevan S., Silambanan S., et al. Effect of yoga on oxidative stress in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2022;18(2):63–70. doi: 10.2174/1573399817666210405104335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rohini P., Roopa S., Padmavathi R., Maheshkumar K. Immediate effects of the practise of Sheethali pranayama on heart rate and blood pressure parameters in healthy volunteers. J Compl Integr Med. 2021;19(2):415–418. doi: 10.1515/jcim-2020-0448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khan S., Nabi G., Yao L., Siddique R., Sajjad W., Kumar S., et al. Health risks associated with genetic alterations in internal clock system by external factors. Int J Biol Sci. 2018;14(7):791. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.23744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mulla Z.R., Krishnan V.R. Karma-yoga: the Indian model of moral development. J Bus Ethics. 2014;123(2):339–351. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cramer H., Lauche R., Langhorst J., Dobos G. Yoga for depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Depress Anxiety. 2013;30(11):1068–1083. doi: 10.1002/da.22166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Riley K.E., Park C.L. How does yoga reduce stress? A systematic review of mechanisms of change and guide to future inquiry. Health Psychol Rev. 2015;9(3):379–396. doi: 10.1080/17437199.2014.981778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Black D.S., Cole S.W., Irwin M.R., Breen E., Cyr N.M., Nazarian N., et al. Yogic meditation reverses NF-κB and IRF-related transcriptome dynamics in leukocytes of family dementia caregivers in a randomized controlled trial. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2013;38(3):348–355. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2012.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anasuya B., Deepak K.K., Jaryal A.K., Narang R. Effect of slow breathing on autonomic tone & baroreflex sensitivity in yoga practitioners. Indian J Med Res. 2020;152(6):638. doi: 10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_559_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saoji A.A., Raghavendra B.R., Manjunath N.K. Immediate effects of yoga breathing with intermittent breath retention on the autonomic and cardiovascular variables amongst healthy volunteers. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 2018;62(1):41–50. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Metri K.G., Pradhan B., Singh A., Nagendra H.R. Effect of 1-week yoga-based residential program on cardiovascular variables of hypertensive patients: A comparative study. Int J Yog. 2018;11(2):170. doi: 10.4103/ijoy.IJOY_77_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kuppusamy M., Kamaldeen D., Pitani R., Amaldas J., Ramasamy P., Shanmugam P., et al. Effects of yoga breathing practice on heart rate variability in healthy adolescents: a randomized controlled trial. Integr Med Res. 2020;9(1):28–32. doi: 10.1016/j.imr.2020.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bagga O.P., Gandhi A. A comparative study of the effect of Transcendental Meditation (TM) and Shavasana practice on cardiovascular system. Indian Heart J. 1983;35(1):39–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kamei T., Toriumi Y., Kimura H., Kumano H., Ohno S., Kimura K. Decrease in serum cortisol during yoga exercise is correlated with alpha wave activation. Percept Mot Skills. 2000;90(3):1027–1032. doi: 10.2466/pms.2000.90.3.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pal R., Singh S.N., Chatterjee A., Saha M. Age-related changes in cardiovascular system, autonomic functions, and levels of BDNF of healthy active males: role of yogic practice. Age. 2014;36(4):1–17. doi: 10.1007/s11357-014-9683-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kjaer T.W., Bertelsen C., Piccini P., Brooks D., Alving J., Lou H.C. Increased dopamine tone during meditation-induced change of consciousness. Cognit Brain Res. 2002;13(2):255–259. doi: 10.1016/s0926-6410(01)00106-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cowen P.J., Browning M. What has serotonin to do with depression? World Psychiatr. 2015;14(2):158. doi: 10.1002/wps.20229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lim S.-A., Cheong K.-J. Regular yoga practice improves antioxidant status, immune function, and stress hormone releases in young healthy people: a randomized, double-blind, controlled pilot study. J Alternative Compl Med. 2015;21(9):530–538. doi: 10.1089/acm.2014.0044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hansen M.V., Madsen M.T., Hageman I., Rasmussen L.S., Bokmand S., Rosenberg J., et al. The effect of MELatOnin on Depression, anxietY, cognitive function and sleep disturbances in patients with breast cancer. The MELODY trial: protocol for a randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blinded trial. BMJ Open. 2012;2(1) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tooley G.A., Armstrong S.M., Norman T.R., Sali A. Acute increases in night-time plasma melatonin levels following a period of meditation. Biol Psychol. 2000;53(1):69–78. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0511(00)00035-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shete S.U., Verma A., Kulkarni D.D., Bhogal R.S. Effect of yoga training on inflammatory cytokines and C-reactive protein in employees of small-scale industries. J Educ Health Promot. 2017;6 doi: 10.4103/jehp.jehp_65_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gagrani M., Faiq M.A., Sidhu T., Dada R., Yadav R.K., Sihota R., et al. Meditation enhances brain oxygenation, upregulates BDNF and improves quality of life in patients with primary open angle glaucoma: a randomized controlled trial. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 2018;36(6):741–753. doi: 10.3233/RNN-180857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tolahunase M., Sagar R., Dada R. Impact of yoga and meditation on cellular aging in apparently healthy individuals: a prospective, open-label single-arm exploratory study. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2017;2017 doi: 10.1155/2017/7928981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dada T., Mittal D., Mohanty K., Faiq M.A., Bhat M.A., Yadav R.K., et al. Mindfulness meditation reduces intraocular pressure, lowers stress biomarkers and modulates gene expression in glaucoma: a randomized controlled trial. J Glaucoma. 2018;27(12):1061–1067. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0000000000001088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kovanen L., Donner K., Partonen T. SIRT1 polymorphisms associate with seasonal weight variation, depressive disorders, and diastolic blood pressure in the general population. PLoS One. 2015;10(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0141001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kishi T., Yoshimura R., Kitajima T., Okochi T., Okumura T., Tsunoka T., et al. SIRT1 gene is associated with major depressive disorder in the Japanese population. J Affect Disord. 2010;126(1–2):167–173. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Abe-Higuchi N., Uchida S., Yamagata H., Higuchi F., Hobara T., Hara K., et al. Hippocampal sirtuin 1 signaling mediates depression-like behavior. Biol Psychiatr. 2016;80(11):815–826. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2016.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lu G., Li J., Zhang H., Zhao X., Yan L.J., Yang X. Role and possible mechanisms of Sirt1 in depression. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2018:2018. doi: 10.1155/2018/8596903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Arora S., Bhattacharjee J. Modulation of immune responses in stress by Yoga. Int J Yoga. 2008;1(2):45. doi: 10.4103/0973-6131.43541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bryant E.F. North Point Press; 2015. The yoga sutras of Patanjali: a new edition, translation, and commentary. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dylan A., Muncaster K. The yamas and niyamas of ashtanga yoga: relevance to social work practice. J Relig Spiritual Soc Work Soc Thought. 2021;40(4):420–442. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bagya D.A., Ganesan T., Maheshkumar K., Venkateswaran S.T., Padmavathi R. Perception of stress among yoga trained individuals. Natl J Physiol Pharm Pharmacol. 2018;8(1):47–50. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Salmon P., Lush E., Jablonski M., Sephton S.E. Yoga and mindfulness: Clinical aspects of an ancient mind/body practice. Cognit Behav Pract. 2009;16(1):59–72. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Batten S.V., Orsillo S.M., Walser R.D. Acceptance and mindfulness-based approaches to anxiety. Springer; 2005. Acceptance and mindfulness-based approaches to the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder; pp. 241–269. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kuppusamy M., Kamaldeen D., Pitani R., Amaldas J., Ramasamy P., Shanmugam P., et al. Effect of Bhramari pranayama practice on simple reaction time in healthy adolescents–a randomized control trial. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2020;33(6):547–550. doi: 10.1515/ijamh-2019-0244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Saeed S.A., Antonacci D.J., Bloch R.M. Exercise, yoga, and meditation for depressive and anxiety disorders. Am Fam Physician. 2010;81(8):981–986. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Morone N.E., Lynch C.P., Losasso V.J., Liebe K., Greco C.M. Mindfulness to reduce psychosocial stress. Mindfulness. 2012;3(1):22–29. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Thanalakshmi J., Maheshkumar K., Kannan R., Sundareswaran L., Venugopal V., Poonguzhali S. Effect of Sheetali pranayama on cardiac autonomic function among patients with primary hypertension-A randomized controlled trial. Compl Ther Clin Pract. 2020;39:101138. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2020.101138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.De Manincor M., Bensoussan A., Smith C.A., Barr K., Schweickle M., Donoghoe L.L., et al. Individualized yoga for reducing depression and anxiety, and improving well-being: A randomized controlled trial. Depress Anxiety. 2016;33(9):816–828. doi: 10.1002/da.22502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Prathikanti S., Rivera R., Cochran A., Tungol J.G., Fayazmanesh N., Weinmann E. Treating major depression with yoga: A prospective, randomized, controlled pilot trial. PLos One. 2017;12(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0173869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ramanathan M., Bhavanani A.B., Trakroo M. Effect of a 12-week yoga therapy program on mental health status in elderly women inmates of a hospice. Int J Yoga. 2017;10(1):24. doi: 10.4103/0973-6131.186156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Falsafi N. A randomized controlled trial of mindfulness versus yoga: effects on depression and/or anxiety in college students. J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc. 2016;22(6):483–497. doi: 10.1177/1078390316663307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Davis K., Goodman S.H., Leiferman J., Taylor M., Dimidjian S. A randomized controlled trial of yoga for pregnant women with symptoms of depression and anxiety. Compl Ther Clin Pract. 2015;21(3):166–172. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2015.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kovačič T., Zagoričnik M., Kovačič M. Impact of relaxation training according to the Yoga in Daily Life® system on anxiety after breast cancer surgery. J Compl Integr Med. 2013;10(1):153–164. doi: 10.1515/jcim-2012-0009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ghaffarilaleh G., Ghaffarilaleh V., Sanamno Z., Kamalifard M. Yoga positively affected depression and blood pressure in women with premenstrual syndrome in a randomized controlled clinical trial. Compl Ther Clin Pract. 2019;34:87–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2018.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Streeter C.C., Gerbarg P.L., Saper R.B., Ciraulo D.A., Brown R.P. Effects of yoga on the autonomic nervous system, gamma-aminobutyric-acid, and allostasis in epilepsy, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder. Med Hypotheses. 2012;78(5):571–579. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2012.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Streeter C.C., Whitfield T.H., Owen L., Rein T., Karri S.K., Yakhkind A., et al. Effects of yoga versus walking on mood, anxiety, and brain GABA levels: a randomized controlled MRS study. J Alternative Compl Med. 2010;16(11):1145–1152. doi: 10.1089/acm.2010.0007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Uebelacker L.A., Epstein-Lubow G., Gaudiano B.A., Tremont G., Battle C.L., Miller I.W. Hatha yoga for depression: critical review of the evidence for efficacy, plausible mechanisms of action, and directions for future research. J Psychiatr Pract. 2010;16(1):22–33. doi: 10.1097/01.pra.0000367775.88388.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Raghavendra R.M., Vadiraja H.S., Nagarathna R., Nagendra H.R., Rekha M., Vanitha N., et al. Effects of a yoga program on cortisol rhythm and mood states in early breast cancer patients undergoing adjuvant radiotherapy: a randomized controlled trial. Integr Cancer Ther. 2009;8(1):37–46. doi: 10.1177/1534735409331456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Brinsley J., Schuch F., Lederman O., Girard D., Smout M., Immink M.A., et al. Effects of yoga on depressive symptoms in people with mental disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2021;55(17):992–1000. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2019-101242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kuppusamy M., Ramaswamy V., Shanmugam P., Ramaswamy P. Yoga for children in the new normal–experience sharing. J Compl Integr Med. 2021;18(3):637–640. doi: 10.1515/jcim-2020-0404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

This is a review paper and content is taken from the approved scientific literatures.