Abstract

Upon returning home from the military, America's veterans face complex challenges such as homelessness and substance use disorders (SUD). Veterans who have experienced SUDs and homelessness are more likely to struggle with depression and suicidal behaviors. This study aims to understand homeless veterans' lived experiences of their everyday life and social interactions. We used semi-structured interviews to conduct a phenomenological study of 14 homeless veterans with known SUDs living in the Baltimore-Washington D.C. Metropolitan area. A Social-Ecological Model (SEM) was used to create themes, a priori, then used open coding analytic methods to identify emerging themes. Two-thirds of veterans used illicit drugs or abused alcohol, and nearly all reported a history of depression or anxiety. Suicidal behaviors were present in a third of all veterans. We found that veteran homelessness and substance use are strongly associated with emotional and physical trauma suffered while on active duty. Consequently, once homeless, a veteran's community may encourage and exacerbate SUDs, thus impeding a path toward sobriety. Homeless veterans who have struggled with SUDs and later experience a death in their family often relapse to substance use. Deeply exploring a veteran's relationships with family, friends, and their immediate community may reveal opportunities to address these issues using healthcare and community interventions.

Keywords: Social-ecological model (SEM), Veteran, Homeless, Substance use, Suicide, Mental illness

1. Introduction

Many of America's veterans struggle upon returning to civilian life. Two notable challenges include substance use disorders (SUD) and homelessness [1,2]. Homelessness is considered one of the most common determinants of substance use among veterans [3]. Additionally, veterans lacking stable housing generally have low SUD treatment compliance [4]. More focused and effective interventions are necessary to reduce homelessness among veterans entering substance abuse treatment [5]. The Veterans Health Administration (VHA), a sub-cabinet level agency within the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), provides healthcare for all qualifying U.S. military veterans and is considered the largest integrated health care system in the United States [6]. The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) partnered with VA supportive housing (VASH) to move veterans and their families out of homelessness [4]. Research shows that nearly 60% of homeless veterans in the HUD-VASH program had an SUD, with the majority having both an alcohol and drug use disorder [7]. Veterans may be more likely to become homeless due to addiction and mental health issues, with more than half of those homeless veterans seeking help via hospital emergency departments [2].

In terms of relapse, a 2008 study evaluated the association between Healthy Lifestyle Behaviors (HLBs) and relapse rates in a homeless residential rehabilitation program [8]. The study found that veterans who practiced several HLBs, such as recreational, social, coping/spiritual, and substance recovery activities, showed lower relapse rates [8]. Previous research has shown the importance of enforcing continued and focused SUD relapse prevention behaviors following residential treatment [9]. Additionally, treatment completion is vital to reducing substance use incidences after discharge, and those who complete substance use treatment have fewer relapses and are more likely to maintain abstinent from substance use after completing treatment [10,11].

Veterans with SUDs also experience suicidal behaviors. Before joining the military, veterans may have been already susceptible to suicidal behaviors due to having pre-existing mental illness and substance use [12], or a history of incarceration [13]. Both psychiatric illness and a history of substance abuse are strongly associated with chronic suicidal behaviors [14]. Unfortunately, substance abuse may originate from prescribed pain management medications used to assuage symptoms from service-related injuries [15].

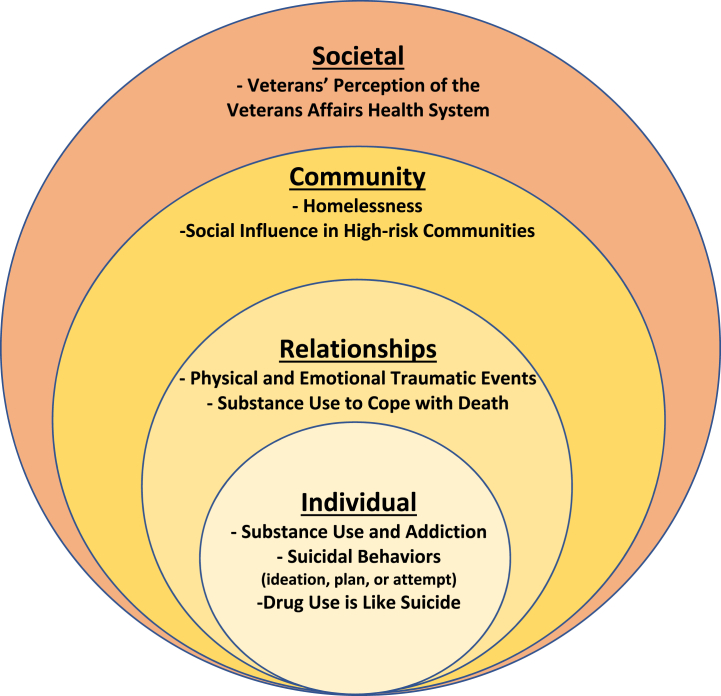

To fully evaluate the multitude of factors that may influence substance use and abuse, relapse, and other mental health illnesses among homeless veterans, a structured framework is necessary to categorize and analyze veterans' lived experiences with these medical conditions. A social-ecological model (SEM) used to evaluate veteran substance use disorders and relapse is beneficial for several reasons. The SEM provides a multilevel analysis that hones in on multiple levels of influence ranging from individual characteristics to interpersonal relationships, community factors, and wider societal influences like healthcare received from the VHA [16]. This framework assists researchers in evaluating the intensity of factors that influence veterans' SUDs and other mental health illnesses and allows for the development of more focused interventions to support veterans’ well-being and recovery.

2. Study aims

This study intended to uncover the challenges faced by homeless veterans living with SUDs. This study investigates major barriers and facilitators in maintaining sobriety upon completion or termination of SUD residential treatment in the Baltimore-Washington D.C. metropolitan areas among homeless veterans. We used the SEM [17] (Fig. 1), originally used to understand violence, and adopted it to understand the complex interplay of factors that influence homeless veterans' behaviors and experiences within their social and environmental contexts. We also used this framework to construct our study design and develop interview questions. Specifically, this model helped us understand how a veteran's health is affected by the interaction of their individual characteristics, relationships, community, and societal environments. The aims of this study were: 1) Understand how individual characteristics increase the likelihood of SUD relapse (Individual); 2) Explore how cultural norms and personal relationships influence SUD relapse (Relationships); 3) Discover how living conditions (homelessness) influence substance use and abuse or suicidal behaviors (if any) (Community); 4) Examine how societal networks and access to basic needs influence substance use and abuse (Societal).

Fig. 1.

Social-Ecological Model (SEM) and corresponding themes. Impact of social-ecological factors on substance use and relapse on homeless U.S. military veterans.

3. Materials and methods

3.1. Design

This study aimed to understand veterans' lived experiences with homelessness, SUDs, and other mental illnesses. We conducted a phenomenological study, which allowed for the development of a complete, accurate, clear, and articulate description and understanding of a homeless veteran's human experience with an SUD.

3.2. Sample

Our sample included 14 U S. military veterans. We selected respondents using a purposive sampling method from veterans who had experienced both homelessness and substance use. Inclusion criteria required that respondents reside in the Baltimore-Washington D.C. Metropolitan area and must have experienced homelessness in the last 12 months. We chose this location because the Baltimore-Washington D.C. Metropolitan area is one of the top areas that saw an increase in homeless veterans between 2019 and 2020 [18]. Another important inclusion criterion is that participants must have self-reported having an SUD sometime in the past and have recently participated in SUD treatment (within the last 12 months). The exclusion criteria required respondents not being on active duty in the U.S. Armed Forces or on reserve status. Veterans with current self-disclosed physical/mental health conditions that they considered would inhibit or delay the interview process were not included in the study. The intent of this study was not to treat, diagnose, or provide counseling for any of the respondent's current health conditions. This research was approved by the primary author's Institutional Review Board and all participants consented to be interviewed for this study.

3.3. Recruitment and data generation

Our recruitment strategy involved contacting several homeless organizations by phone and in person, which included homeless shelters, Veteran Service Organizations (VSO), and food pantries to identify willing veteran participants. Only one homeless shelter, Project “PLASE” - People Lacking Ample Shelter and Employment, and a VSO, Maryland Center for Veterans Education and Training (MCVET), agreed to provide veterans’ contact information for recruitment purposes.

Some veterans who initially met the inclusion/exclusion criteria did not return phone calls or emails asking for participation in the study. We screened 26 veterans, and only 14 of them met the inclusion criteria and completed the interview. The semi-structured interview questions included predetermined and open-ended questions. This interview's structure fostered rapport between the researcher and respondent and created opportunities to expound upon emerging themes and theories [19,20]. Respondents received a gift card for every interview session they participated in.

Interview questions were constructed a priori using the SEM as a framework to guide themes within the four SEM levels. The first several questions focused on basic demographics and military background. The remaining questions focused on the respondents' history of homelessness, substance use, depression, and suicidal behaviors.

3.4. Data analysis process

Veterans serve as the unit of analysis for this study. The semi-structured interviews provide context, constraints, and individual viewpoints of the veteran's lived-experiences with SUD, homelessness, and/or suicidal behaviors, if any. All phone interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed for analysis using NVivo 12 software [21]. We conducted theme coding using two analytic methods, a priori, and open coding [22]. We used a priori techniques to create themes prior to coding using the SEM and used open coding after data collection to identify emerging themes.

4. Results

4.1. Characteristics of study respondents

The 14 participating veterans represented various demographic and military characteristics (Table 1). Nearly two-thirds (64.3%) of the veterans were 35–64 years old. Most veterans were male (92.9%), African-American (64.3%), served in the Army (42.9%), while nearly half (42.9%) of them served during the post-Vietnam era from 1976 to 1990 and the other half (42.9%) served during the OEF/OIF era from 2001 to 2021. Most of the respondents used illicit drugs (78.6%), including heroin, cocaine, crack-cocaine, Molly (MDMA), Fentanyl, and marijuana. The same percentage of veterans (78.6%) abused alcohol either as a sole substance without using any other drugs, or in combination with other mind-altering substances.

Table 1.

Veterans’ demographics, substance use, and mental health illness history.

| Characteristics | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Total Sample | 14 |

| Age | |

| 18–34 | 3 (21.4) |

| 35–64 | 9 (64.3) |

| >65 | 2 (14.3) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 13 (92.9) |

| Female | 1 (7.1) |

| Race | |

| African-American | 9 (64.3) |

| White | 2 (14.3) |

| Othera | 2 (14.3) |

| Military Branch | |

| Armyb | 6 (42.9) |

| Navy | 3 (21.4) |

| Marine Corps | 2 (14.3) |

| Air Force | 2 (14.3) |

| Coast Guard | 1 (7.1) |

| Service Eras | |

| Vietnam 1961–1975 | 1 (7.1) |

| Post-Vietnam 1976–1990 | 6 (42.9) |

| Gulf War 1990–2000 | 1 (7.1) |

| OEF/OIF 2001–2021 | 6 (42.9) |

| Illicit Drug Use | 11 (78.6) |

| Alcohol Abuse | 11 (78.6) |

| Arrest History | 9 (64.3) |

| Depression/Anxietyc | 13 (92.9) |

|

Suicidal Behaviorsc Traumatic Eventd |

5 (35.7) 7 (50) |

Mixed races: White-Hispanic (1), African-American-Hispanic (1). One (1) declined to answer.

Included one (1) Army National Guard.

Self-reported conditions by the participant and not verified by health record.

Major traumatic event that triggered substance use and/or relapse.

Most veterans reported having an arrest history (64.3%), and almost all reported having a history of depression or anxiety (92.9%). More than a third of all veterans reported having suicidal behaviors (35.7%). Lastly, half (50%) of veterans reported at least one major traumatic event that triggered either initial substance use or relapse after receiving treatment for their SUDs.

4.2. SEM level – corresponding themes

4.2.1. Individual – substance use and addiction

Table 2 includes all levels of the SEM, corresponding themes, and respondent quotes from this study. We found that substance did not consistently originate at any specific point in a veteran's life. Some veterans began abusing drugs and alcohol early in their life, while others began using substances after transitioning out of the military.

Table 2.

SEM levels, themes, and supporting respondent quotes from homeless veterans living with SUDs and mental illness.

| SEM Levelsa | Themes | Supporting Respondent Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Individual | Substance Use and Addiction | “The euphoria … You get the first euphoria, then it wears off and you just doing it, just to do it. After a while, the money you get is not going to be legitimate … and if you do get it legitimately, like for me, it wouldn't last long …” [VET05] |

| Individual | Suicidal behaviors | “… some group of like the transient group I was with that was like helping me get by, I thought they were out to get me, you know, but like I was like feeling really paranoid because they found out I cheated on my girlfriend and was doing shitty things in the community … And, you know, they wanted to fight and they wanted to, like, stab me and shit. So, it's like, I wanted to just fucking end it before they did, you know?” [VET03] |

| “… I still like … Kind of [have] thoughts of ‘what if he [friend] didn't do it?‘ … or what if I could have stopped it, or what would be a different outcome if I had talked to him, like, I had just listened. I still at times catch myself blaming myself because of what happened.” [VET07] | ||

| “I had a razor …. I just wanted … I just wanted to die. You know, I ain't had nothing to live for, you know, and like I wasn't getting nowhere. You know, the thought came, the feeling came and everything else came along with it.” [VET14] | ||

| “I was on the bridge at one time, and then I looked in the water, I said [to myself], ‘you know you can't swim.’ [Then], this guy I knew came, he was walking by, I was on the bridge or whatever, and he came by [and] he said … get off that bridge!” [VET04] | ||

| Individual | Drug use is like suicide | “No, no, I never considered committing suicide. Never been on the table. Only suicide I was committing was, like, each time I went out to go get some drug that does not have any type of ingredients on it … I feel as though that's slowly committing suicide.” [VET05] |

| “Well, mainly the hard drugs I did when I was homeless was kind of suicidal because it's very dangerous, you know? I think it could have been somewhat suicidal, you know, because it's very dangerous to do a lot by yourself and you don't really notice what you're getting into.” [VET08] | ||

| Relationships | Physical and Emotional Traumatic Events | “It takes a toll on you physically and mentally. But I would say it was more so mental than physical because seeing, you know, seeing some of the stuff that I've seen, and hearing, like, people tell stories about the stuff that they witnessed or been through on deployment ….” [VET07] |

| “… I was attacked by a Company Commander sergeant in the shower. You know, she tried to …. Rape me … And I fought her off and the words she used out her mouth …, ‘You'll never be nothing, you'll never get nowhere … [if] you tell anybody I'm in here … ’ [VET14] | ||

| “… I deployed to Afghanistan … and, you know, I've dealt with a lot of anxiety and depression and ‘flashbacks’ and, you know, a bunch unwanted feelings and thoughts that I never had prior to my deployment.” [VET10] | ||

| Relationships | Substance Use to Cope with Death | “… I didn't have no help, I didn't have family, no friends, my mom had [died] … I lost my mom during that time, too. I wasn't able to go see her because I was in Texas transitioning from the military. So, I just really went to a real dark place and I didn't want to eat … I would just wake up, you know, I just [didn't] want to feel that. I didn't want to feel it … so, I ran to alcohol.” [VET10] |

| “I went to [a treatment facility] because I had a downfall when …. Somebody - my sister, and I had to bury her … and aunts [died] … Everything was like … they were dying, like, back-to-back, months apart and stuff. I went to [a treatment facility] and I got back on [Suboxone].” [VET14] | ||

| “… when I come out the door, and I'm looking, and I'm like, who are these guys with a gun at my son's head? … and when he handed them the 20 dollars, the guy said, ‘is that all?‘ … And he pulled the trigger. So, I actually sat there and witnessed it … But I was, like, stuck and I couldn't move to do anything.” “That picture I dealt with for about … I say nine years my life. I was trying to get this picture out … Then, all of a sudden, I just started self-medicating.” [VET13] | ||

| Community | Homelessness | “At the time, I didn't know where I was going to go as far as when I got out … we pretty much like bounced around from place to place, anywhere we could lay our head.” [VET07] |

| “I joined the military around 17 and a half … And I was homeless immediately after my discharge, which was around when I was 21. Went to Towson University and I was homeless again when I was 23 …” [VET03] | ||

| “… being homeless and me drinking pretty much ran hand in hand …” “ …. I did it to pretty much, like, get away from that [homeless] world …” [VET07] | ||

| Community | Social Influence of Substance Use in High-risk Communities | “Well, the main thing was that I can't be homeless alone. There's too much things to worry about and to do. So, I usually have to team up with somebody, and you just naturally meet people … and these people have drugs on them, you know, and Molly is the least of them.” [VET03] |

| “… I ain't had no money, but if I met somebody who was buying, I was drinking.” “… one thing, you meet all the homeless people out there, and I don't know if you have ever seen people panhandle, but that's how we did what we did … by panhandling.” [VET04] | ||

| “I tried it to see how the cocaine felt … I liked the experience that I enjoyed [during] that period of time … and [I] went from me indulging in it from every two weeks, then it went from every two weeks to every week, and then it went from every week to every weekend, then from every weekend to every day … It went from a fun thing to becoming misery down the road.” [VET05] | ||

| Community | Violence and Crime in Homelessness | “I was waiting outside [food pantry] and these guys … I don't know … these young guys … I didn't do anything to them … and they jumped me. One of them hit me with something. I was sitting outside in broad daylight, 1:00 [pm].” “They took $60 … and my cigarettes.” [VET02] |

| “I didn't think small petty money, I was looking for a large lump sum of money to have it last longer … And so the (illegal) stuff I was doing provided a large sum of money at a faster pace and faster time.” [VET05] | ||

| Societal | Veterans' Perception of the Veterans Affairs Health System | “… doctors aren't supposed to give any one of those … Pain pills that long. I mean, for four years, how am I not supposed to be hooked on drugs?” [VET01] |

| “My father is a veteran and I've seen how they treat him and they're just being gutted with their budget … and I think that, you know, it's a political thing. They just don't have the funds to keep it going …” [VET03] |

Social-Ecological Model (SEM) levels and themes were displayed in Fig. 1.

An African-American Marine Corps veteran in his mid-thirties [VET05] explained how becoming addicted to drugs happened organically. He lacked self-awareness and became chemically dependent without warning, “I really didn't know what an addictive personality was …” He talked about chasing the “euphoria” reached the first time a person consumes a drug, then tried maintaining it without question. This sentiment was a reoccurring theme among participants.

4.2.2. Individual – suicidal behaviors

More than a third of the veterans in this study reported having some type of suicidal behavior. While some went beyond ideation and followed through with a plan and attempt, others considered their drug use a form of suicidal behavior. One veteran mentioned that he “… sat there with a gun in my mouth a couple times …” [VET03] because he thought another group of homeless people were trying to stab him. A second veteran [VET14] described her experience with planning her suicide with a razor as a way out of what she was going through and explained how she did not want to burden anyone else with her problems. Another veteran [VET04] considered attempting suicide because “… at that time, I had nothing …” and contemplated jumping from a bridge.

A veteran in his late twenties [VET07] talked about his experience with suicidal behaviors. He began having suicidal ideations after a close friend committed suicide. His friend’s suicide came without warning, and still blames himself for not doing more to prevent his friend’s death. This veteran described personal challenges of coping with this traumatic event. This same veteran also experienced death in his family while in basic training. His older brother was shot and killed less than three weeks after leaving for basic training.

4.2.3. Individual – drug use is like suicide

One interesting individual theme that emerged from this study was the respondents' self-awareness of the deleterious effects of their substance use. Although these veterans reported not having suicidal behaviors, they equated their chronic substance use as a form of suicide attempt. They mentioned that while their intention was never to kill themselves, understanding what large quantities of drug consumption can do to one's body was equivalent to attempting suicide. One of the veterans [VET12] described chasing the feeling he experienced the first time he smoked crack and never reaching it. As previously mentioned, drug addicts often find themselves chasing the original sensation they felt the first time they consumed drugs.

4.2.4. Relationships – physical and emotional traumatic events

While many service members complete their time in the military honorably and without much exposure to traumatic events, many veterans who struggle with substance use often attribute their substance addictions to the mental trauma they sustained while on active duty. A Hispanic African-American Army veteran [VET07] explained how some of his military experiences weighed heavily on his mental health. He talked about how some of the pre-deployment videos he watched and the things he saw while on deployment took a toll on him physically and mentally. He explained that age was not a factor in processing these events and how these experiences negatively impacted everyone around him.

A female veteran in her mid-sixties [VET14] still vividly recalls the day she experienced a horrific sexually traumatic event while showering in her barracks. Her anger and frustration shone through the volume and tone of her voice during her recollection of the event. She attributes her depression and anxiety to this event in her life. She explained her traumatic event in great detail. She talked about how it made her feel violated in that manner while in such a vulnerable state. She reported the incident to her chain-of-command, but they disregarded her story and said she was lying.

An Army veteran in his late twenties [VET10], who declined to disclose his race and ethnicity, talked about how his memories from previous war deployments led him to alcohol abuse. He mentioned how he lived in a state of denial after deploying to Afghanistan. He still experiences flashbacks from war and traumatic memories he had to endure. He explains that his pride and wanting to feel like nothing was wrong led him to drown these difficult memories with alcohol.

An Air Force veteran in his mid-thirties [VET09] talked about his addiction to alcohol and how his condition was exacerbated by experiencing “physical and mental trauma” both as a Special Operations specialist and as a firefighter in the military. He was very guarded in expressing detail in his responses and provided very broad descriptions of his experience with trauma; yet, his tone, long pauses between thoughts, and eagerness to change topics presented a clearer picture of the difficulty he had recalling some of those experiences. He also made an effort to validate his toughness by emphasizing where he grew up:

“… there’s mental trauma and there is physical trauma … [pause] … I’m pretty sure you know war brings mental trauma … [long pause] … I’m pretty sure you know firefighting brings mental trauma and it brings physical trauma … [longer pause] … I’m from South Central, Los Angeles, and I grew up gang-banging …”

One Navy veteran in his early forties [VET11] states that he started substance use after a traumatic divorce from his wife and feeling abandoned by his family and friends. He recalled feeling hopeless and helpless:

“… for me, it's like I just snapped. It's like, what the hell did I fight for? … Like, what do I have right now? It's scary. It's like the movie The Matrix, like did I [take] the wrong pill?”

4.2.5. Relationships – substance use to cope with death

One constant relationships theme that emerged from this study was the significant impact that the death of a family member had on a veteran's substance use. Even for those who had discontinued substance use, losing a loved one reignited the need for drugs and alcohol to cope with depression and to help them grieve their loss.

One veteran [VET10] described how his mother’s death, along with homelessness, intensified his alcohol abuse. He mentioned that a lack of support from friends and family made him feel like he had nothing. He drank alcohol to mask his pain and his sorrows during that time. When asked if he thought that homelessness contributed to his alcohol use, he responded:

“Yes, most definitely because I felt like I didn't have no options. I didn't have no help. I didn't have nothing.”

A female veteran [VET14] recalled that after being clean-and-sober over seven years, she relapsed and needed rehabilitative care because several family members died consecutively. She struggled to balance her personal life and dealing with so much death in her family. She spoke about having to reach out for help after she relapsed and how she started a medication to treat her opioid use disorder. She attributed her relapse to grieving her family members' deaths.

Perhaps the most impactful story leading to substance use came from an African-American Army veteran in his late-sixties [VET13] who used substances to grieve the death of a family member. Holding back tears, he talked about the day he witnessed his only child get shot in the head after being robbed in his own home. He mentioned that this event was the sole reason why he turned to drug use and became addicted to heroin. The pain from his trauma was palpable throughout his story and how he told it. He recalled this traumatic experience and how it came with a great deal of personal shame and regret for not reacting while this event unfolded. His deceased son was getting ready to be a father; however, he was shot and killed three days before his son was born. Today, this veteran is staying clean and sober to be present for his only grandson.

4.2.6. Community – homelessness

Veterans often struggle with reentry and social reintegration into the civilian sector post-release from the military, particularly with housing and access to mental health care [23]. All respondents had some experience with homelessness, ranging from three weeks to ten years. Some respondents reported becoming homeless immediately after their military discharge, while others reported becoming homeless due to difficulties they had encountered over time.

One Air Force veteran in his late-fifties [VET06] reported that becoming homeless was “… the last straw” after a series of lost battles with drug addiction and numerous failed rehabilitative substance use treatment attempts. He mentioned that homelessness “… made me more determined to get clean.” Another veteran [VET03] recalled being homeless at 13 years old when he and his family were evicted from their home, resulting from a foreclosure. He and his family moved around from place to place until he joined the military. The military was the only constant and dependable housing he ever had. Once he separated from the military, he immediately became homeless and has since experienced homelessness on three different occasions.

4.3. Community – social influence of substance use in high-risk communities

Homeless veterans often find themselves in a perpetual drug use-sobriety-relapse cycle due to the instability of their housing status and the people within their environment. Homeless individuals regularly contend with unstable and transient social relationships related to their uncertain housing situation [24]. Notably, substance use is often the commonality forging fleeting relationships in homeless communities. High-risk communities include the nightlife communities, and should be avoided by addicts looking to recover from substance use [25]. The next few examples display how these high-risk communities influence substance use in the veteran population.

A White Hispanic Coast Guard veteran in his mid-twenties [VET03], with a deep family history of substance use and alcohol abuse, talked about becoming homeless after leaving the military. Due to VA medical record documentation requirements, he was denied medical care from the VA health system upon discharge from the military. At 21-years-old, he found himself homeless and without friends, family, or the federal government to support him during his transition from the military. He also reported that homelessness contributed to his substance use. He began experimenting with ‘Molly” (MDMA) while he was still in the military; he then increased using this drug once he became homeless. He explained how becoming homeless and surrounding himself with other homeless people who were doing drugs increased his drug use. His desire to “fit in” in the homeless community and to counteract the feeling of depression stemming from homelessness led to his drug addiction.

One veteran [VET05] described how he transitioned from being a casual drug user to becoming an addict. Once a Special Forces Marine, a District of Columbia Guardsman, and a federal employee, a government furlough led him to find work where his unique type of skills were required. He became a bouncer (security) for several Maryland strip clubs (adult entertainment). He stated that the people and the community surrounding that type of business lent themselves to substance abuse. He described this as the “turning point” in his life where he felt everything spiraling out of control.

4.4. Community – violence and crime in homelessness

Violence is common among the homeless community, particularly if there are drugs involved. Whether the veterans committed the crimes or were recipients of a violent act, this study revealed that most homeless veterans experience some level of violence in their lives.

One veteran [VET02] interviewed for this study while still in a hospital's primary care department. He had been the victim of a violent attack while standing in line to receive food from a local food pantry just the night before the interview. He stated that the assailants were likely homeless as well and were standing in line alongside him. The assault location is a place where homeless people are not only provided food but also a place where they can attend Alcoholics Anonymous or Narcotics Anonymous meetings. He mentioned that this whole event was unprovoked and happened in “broad daylight.” Although offered to continue this interview after he fully recovered from his injuries, he was adamant about finishing it because he believed his story was important to share.

Another veteran [VET05] talked about the crimes he had to commit to maintain his addiction and to earn his stay in a communal home shared by other drug addicts engaged in criminal activities. He explained that his drug addiction led to numerous incarcerations. The people he lived with took advantage of his drug dependence and expected him to commit the most egregious crimes because of his military experience.

4.4.1. Societal – veterans’ perception of the Veterans Affairs health system

As active-duty service members separate from the military and become veterans, the federal government is responsible for caring for these veterans' health through the VHA. This level of the SEM represents the outermost factor impacting a veteran's environment.

An African-American veteran in his late forties [VET01] blamed the VA for his addiction to opioids. He stated that he would have never become addicted to painkillers had it not been for the VA unscrupulously prescribing him pain medications for over four years. To assuage the respondent's pain from spinal surgery, he started taking prescribed Oxycodone. He mentioned that his primary care physician routinely evaluated his pain, and the treatment was always Oxycodone. He said that once the phone interview was over, they would prescribe him more opioids.

A White Hispanic Coast Guardsman in his mid-twenties [VET03] discussed not having much faith in the VA. Although he does not receive health care from the VA health system, his opinions of the VA stem from witnessing the inadequate care his father, a Vietnam veteran, receives. The VA does not recognize this respondent as a veteran because he did not serve his entire four-year contract with the military. He receives all his healthcare from hospital emergency departments and homeless organizations like the one he is currently affiliated with.

5. Discussion

This study of veterans who have experienced homelessness and substance misuse found several themes that may explain why veterans start using illicit drugs and abusing alcohol and highlight why they may relapse after reaching sobriety. This study's most prevalent emerging themes experienced by veterans include substance use, sobriety, homelessness, and mental illness.

At the individual level of the SEM, veterans revealed extraordinary stories about their substance use history and how they became addicted. They also talked about how becoming an addict gradually crept into their lives and did not originate at any particular point in their life. Our findings align with recent literature in that some drug users start using drugs and alcohol to eliminate unwanted emotions while unknowingly becoming addicted [26]. Other individual-level themes include suicidal behaviors and the perception of drug use being somewhat suicidal. Research shows that those who have contemplated suicide have either worked in high-risk professions, suffered from financial strain, a traumatic event, or victimization [27].

Relationships also played a significant role in a veteran's recovery from SUDs - specifically, how relationships affected the veterans' mental health and how they managed their traumatic memories from the military. There are no restrictions on who a veteran has a relationship with, and is not limited to those they meet and work with in the military. Most abiding military relationships form during unique experiences, often found during wartime [28]. One theme that surfaced from the open analytic methodology and is directly related to the impact of relationships on substance use was how veterans coped with death in their families. Trauma sustained from a family member's death or close friend may not always increase the risk of substance use [8,29]; however, this type of trauma can have a compounding effect on other mental health conditions such as depression, anxiety, and suicidal behaviors [30].

The community that a veteran is a member of and the people who belong to that group can impact the direction of a veteran's sobriety. Most of the emerging themes from this study could fit into the community level in the model. Homelessness, among other social determinants of health, lies at the crux of most substance-use-related issues among the veteran population [[31], [32], [33]]. This study depicted various examples of veterans' homeless episodes and the unique exposure of living in high-risk communities and explains why substance use is more prevalent in homeless individuals [34,35]. The respondents' communities that they engaged in enabled their substance use and discouraged sobriety. Veterans often felt pressured to conform to their new community; to do that, they participated in high-risk activities that were detrimental to their recovery. One of the most shocking, yet revealing stories told by one of the respondents [VET02] was his encounter with a violent attacker. Although rare, these random attacks of violence happen more often to homeless veterans than non-veterans [36]. Unfortunately, homeless individuals have historically been targeted for violent attacks regardless of demographics [37].

At the societal level, our study presented veterans’ points of view on the VHA. Nearly all veterans perceived the VA as a good place to receive health care. Most respondents have service-connected disability benefits that allow them to receive full medical care at any VA healthcare facility. Two veterans [VET01, VET03], however, provided negative feedback regarding the VA health system, and one veteran [VET01] blamed the VA for his addiction to opioids by being over-prescribed painkillers. Although recent research claims a decline in long-term prescription opioid use [38], opioids have long been over-prescribed for recovery after surgical procedures [39].

5.1. Clinical and policy implications

The findings of this study offer distinct examples of the challenges veterans are currently facing to recover from substance use addiction and support previous literature. This study has important implications for both healthcare professionals serving veterans and policymakers involved in veteran-health legislation. Findings from this qualitative investigation of homeless veterans suggest that stable housing is pivotal for this population, especially those recently separated from the military. Often, veterans leaving active duty with a negative discharge do not have a plan for stable housing [40]. Although there are several pre-separation programs and tools that help prepare veterans for civilian life, there is no follow-up system that tracks their progress once they leave the military. Our findings suggest new veterans exposed to either substance use or other mental health conditions during active duty require high-risk surveillance. Monitoring these high-risk veterans until they are fully recovered or connected to a rehabilitative program may lead to better outcomes. Lastly, particular focus should be placed on grief counseling for veterans who experience the death of a relative or close relationship, especially if they have a history of substance use or mental illness.

5.2. Limitations

While this study sheds light on the experiences that veterans undergo while balancing homelessness and SUDs, there are several limitations. First, COVID-19 required social distancing with respondents during interviews, eliminating face-to -face meetings. The COVID-19 restrictions precluded the interpretation of non-verbal language cues, which can often provide the interviewer with more detailed information than those conducted over the phone [41]. Second, and possibly one of the most significant difficulties during this study, was recruiting respondents from this vulnerable population. It was challenging to locate and schedule interviews with veterans, even though they are connected (administratively) to one of the two participating homeless organizations. Some veterans did not return calls, others were unavailable during scheduled times, and some changed their inclusion/exclusion criteria once they started the interview, thus, disqualifying them from the study. Third, qualitative research requires that investigators spend time immersing themselves in the respondents’ environment, either in person or through multiple interviews; most interviews only lasted an average of approximately 47 min, thus, making it difficult to build rapport and gain enough trust for the veterans to disclose such sensitive information and share some of their most private stories. Fourth, this qualitative study involved a relatively small sample of participants (N = 14), risking the possibility of not achieving full data saturation [42], thus, impacting the comprehensiveness of the results. Lastly, because all qualitative studies are unique and their data are not publicly accessible, data from these studies are difficult to replicate.

6. Conclusion

Investigating what drives most veterans to experience substance use relapse requires ongoing research. However, we can attempt to appreciate addiction's challenges, especially when compounded with additional stressors such as homelessness and mental illness. Veterans endure unique and traumatic experiences while serving in the military. Some of the effects of these distressing events often linger well after separating from the military and can result in substance abuse. We found that veteran homelessness and substance use are strongly associated with trauma suffered while on active duty and personal adverse life experiences. Consequently, once homeless, the communities that veterans live in generally encourage and exacerbate addiction and impede a path toward sobriety. Homeless veterans who have already struggled with SUDs in the past and later experience a death in their family often relapse to drug and alcohol use. Researchers shall continue qualitative research on homeless veterans suffering from SUDs to expand the initial findings from this study. Exploring a veteran's relationships with family, friends, and immediate community may reveal opportunities to address these issues using healthcare and community interventions.

Author contribution statement

Christian Betancourt: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper. </p>

Debora Goldberg: Conceived and designed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper. </p>

Beth Hawks; Panagiota Kitsantas: Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper. </p>

Data availability statement

The data that has been used is confidential.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethical statement

Our study was approved by George Mason University's Office of Research Integrity and Assurance [1,683,652−1]. All respondents provided written informed consent prior to enrollment in the study.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Navy, Department of Defense, nor the U.S. Government.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Biographies

Christian Betancourt, Ph.D., is an Assistant Professor and the Director of the Master of Health Administration and Policy program in the Department of Preventive Medicine and Biostatistics at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences (USU), Bethesda, MD. His research focuses on U.S. military veteran's health and those suffering from substance use disorders and homelessness.

Debora Goldberg, Ph.D., is an Associate Professor at George Mason University in the Department of Health Administration and Policy. She is a mixed methods researcher with an emphasis on survey and qualitative research methodologies. Her research focuses on primary care practice transformation, patient experience, and care for the underserved.

Beth Hawks, Ph.D., is the Vice Chair for Graduate Programs in the Department of Preventive Medicine and Biostatistics at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences (USU), Bethesda, MD. Her research focuses on public management and health policy in the Military Health System (MHS).

Yiota Kitsantas, Ph.D., is a Professor and Chair of the Department of Population Health and Social Medicine at Florida Atlantic University, Boca Raton, FL. She has extensive research experience in the fields of child and maternal health, especially around utilizing data mining techniques to address various public health issues in these populations.

References

- 1.Boden M.T., Hoggatt K.J. Substance use disorders among veterans in a nationally representative sample: prevalence and associated functioning and treatment utilization. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs. 2018;79(6):853–861. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2018.79.853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dunne E.M., Burrell L.E., 2nd, Diggins A.D., Whitehead N.E., Latimer W.W. Increased risk for substance use and health-related problems among homeless veterans. Am. J. Addict. 2015;24(7):676–680. doi: 10.1111/ajad.12289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chinchilla M., Gabrielian S., Hellemann G., Glasmeier A., Green M. Determinants of community integration among formerly homeless veterans who received supportive housing. Front. Psychiatr. 2019;10:472. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Montgomery A.E., Hill L.L., Kane V., Culhane D.P. Housing chronically homeless veterans: evaluating the efficacy of a housing first approach to HUD-VASH: housing chronically homeless veterans. J. Community Psychol. 2013;41(4):505–514. doi: 10.1002/jcop.21554. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buchholz J.R., Malte C.A., Calsyn D.A., et al. Associations of housing status with substance abuse treatment and service use outcomes among veterans. Psychiatr. Serv. 2010;61(7):9. doi: 10.1176/ps.2010.61.7.698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oliver A. The veterans health administration: an American success story? Milbank Q. 2007;85(1):5–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2007.00475.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsai J., Kasprow W.J., Rosenheck R.A. Alcohol and drug use disorders among homeless veterans: prevalence and association with supported housing outcomes. Addict. Behav. 2014;39(2):455–460. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.LePage J.P., Garcia-Rea E.A. The association between healthy lifestyle behaviors and relapse rates in a homeless veteran population. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2008;34(2):171–176. doi: 10.1080/00952990701877060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang G., Martin K.B., Tang M., Fleming J.A. Inpatient hospitalization for substance use disorders one year after residential rehabilitation: predictors among US veterans. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2016;42(1):56–62. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2015.1088863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Decker K.P., Peglow S.L., Samples C.R., Cunningham T.D. Long-term outcomes after residential substance use treatment: relapse, morbidity, and mortality. Mil. Med. 2017;182(1):e1589–e1595. doi: 10.7205/MILMED-D-15-00560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stahler G.J., Mennis J., DuCette J.P. Residential and outpatient treatment completion for substance use disorders in the U.S.: moderation analysis by demographics and drug of choice. Addict. Behav. 2016;58(July):129–135. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nock M.K., Stein M.B., Heeringa S.G., et al. Prevalence and correlates of suicidal behavior among soldiers: results from the Army study to assess risk and resilience in servicemembers (Army STARRS) JAMA Psychiatr. 2014;71(5):514–522. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Edwards E.R., Barnes S., Govindarajulu U., Geraci J., Tsai J. Mental health and substance use patterns associated with lifetime suicide attempt, incarceration, and homelessness: a latent class analysis of a nationally representative sample of U.S. veterans. Psychol. Serv. 2021;18(4):619–631. doi: 10.1037/ser0000488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith N.B., Mota N., Tsai J., et al. Nature and determinants of suicidal ideation among U.S. veterans: results from the national health and resilience in veterans study. J. Affect. Disord. 2016;197:66–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.02.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ilgen M.A., Bohnert A.S.B., Ganoczy D., Bair M.J., McCarthy J.F., Blow F.C. Opioid dose and risk of suicide. Pain. 2016;157(5):1079–1084. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Golden S.D., Earp J.A.L. Social ecological approaches to individuals and their contexts: twenty years of health education & behavior health promotion interventions. Health Educ. Behav. 2012;39(3):364–372. doi: 10.1177/1090198111418634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dahlberg L. Violence: a global public health problem. Ciência Saúde Coletiva. 2006;11:0. doi: 10.1590/S1413-81232006000200007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.The U.S. Department of Housing . Office of Community Planning and Development; 2021. Urban Development. The 2020 Annual Homeless Assessment Report (AHAR) to Congress; p. 102. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Christenbery T. Standalone interviews do not equal qualitative research. Nurse Author & Ed. 2017;27(4):4. http://naepub.com/reporting-research/2017-27-4-4/ 27. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sterk C.E., Elifson K.W. In: Epidemiology of Drug Abuse. Sloboda Z., editor. Springer US; 2005. Qualitative methods in the drug abuse field; pp. 133–144. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.NVivo Qualitative Data Analysis Software. QSR International Software; 2021. https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home/ Published online. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blair E. A reflexive exploration of two qualitative data coding techniques. Journal of Methods and Measurement in the Social Sciences. 2015;6(1):14–29. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hyde J., Bolton R., Kim B., et al. I’ve just never done that:” The influence of transitional anxiety on post-incarceration reentry and reintegration experiences among veterans. Health & Social Care in the Community. 2022;30(4):1504–1513. doi: 10.1111/hsc.13481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pahwa R., Smith M.E., Yuan Y., Padgett D. The ties that bind and unbound ties: experiences of formerly homeless individuals in recovery from serious mental illness and substance use. Qual. Health Res. 2019;29(9):1313–1323. doi: 10.1177/1049732318814250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Racionero-Plaza S., Piñero León J.A., Morales Iglesias M., Ugalde L. Toxic nightlife relationships, substance abuse, and mental health: is there a link? A qualitative case study of two patients. Front. Psychiatr. 2021;11 doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.608219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maina G., Marshall K., Sherstobitof J. Untangling the complexities of substance use initiation and recovery: client reflections on opioid use prevention and recovery from a social-ecological perspective. Subst. Abuse. 2021;15 doi: 10.1177/11782218211050372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cramer R.J., Kapusta N.D. A social-ecological framework of theory, assessment, and prevention of suicide. Front. Psychol. 2017;8:1756. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ahern J., Worthen M., Masters J., Lippman S.A., Ozer E.J., Moos R. The challenges of Afghanistan and Iraq veterans' transition from military to civilian life and approaches to reconnection. PLoS One. 2015;10(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0128599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stebnicki M.A. Clinical Military Counseling. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2020. Complex military ptsd and Co-occurring mental health conditions; pp. 261–295. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mitchell A.M., Kim Y., Prigerson H.G., Mortimer M.K. Complicated grief and suicidal ideation in adult survivors of suicide. Suicide Life-Threatening Behav. 2005;35(5):498–506. doi: 10.1521/suli.2005.35.5.498. https://www.proquest.com/docview/224873500/abstract/F8003E40BC0C4BBFPQ/1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bhalla I.P., Stefanovics E.A., Rosenheck R.A. Social determinants of mental health care systems: intensive community based Care in the Veterans Health Administration. BMC Publ. Health. 2020;20(1):1–13. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09402-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Evans W.N., Kroeger S., Palmer C., Pohl E. Housing and urban development–veterans Affairs supportive housing vouchers and veterans' homelessness, 2007–2017. American Journal of Public Health; Washington. 2019;109(10):1440–1445. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gundlapalli A.V., Redd A., Bolton D., et al. Patient-aligned care team engagement to connect veterans experiencing homelessness with appropriate health care. Medical Care. 2017;55(2):S104–S110. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stablein G.W., Hill B.S., Keshavarz S., Llorente M.D. In: Clinical Management of the Homeless Patient: Social, Psychiatric, and Medical Issues. Ritchie E.C., Llorente M.D., editors. Springer International Publishing; 2021. Homelessness and substance use disorders; pp. 179–194. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.O'Toole T, Kane V. Return on investment analysis and modeling - White Paper. VA National Center on Homelessness Among Veterans; 2014. https://www.va.gov/HOMELESS/nchav/docs/Return_on_Investment_Analysis_and_Modeling_White-Paper.pdf Published online March 2014:10. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schinka J.A., Leventhal K.C., Lapcevic W.A., Casey R. Mortality and cause of death in younger homeless veterans. Publ. Health Rep. 2018;133(2):177–181. doi: 10.1177/0033354918755709. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26408982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.North C.S., Smith E.M., Spitznagel E.L., North C.S., Smith E.M., Spitznagel E.L. Violence and the homeless: an epidemiologic study of victimization and aggression. J. Trauma Stress. 1994;7(1):95–110. doi: 10.1002/jts.2490070110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hadlandsmyth K., Mosher H., Vander Weg M.W., Lund B.C. Decline in prescription opioids attributable to decreases in long-term use: a retrospective study in the veterans health administration 2010–2016. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2018;33(6):818–824. doi: 10.1007/s11606-017-4283-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Eisenstein M. Easing the pain. Nature. 2019;573(7773):S13–S15. doi: 10.1038/d41586-019-02687-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ritchie E.C. In: Intersections between Mental Health and Law Among Veterans. Tsai J., Seamone E.R., editors. Springer International Publishing; 2019. The critical importance of time, place, and type of discharge from the military; pp. 209–218. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oltmann S. Qualitative interviews: a methodological discussion of the interviewer and respondent contexts. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum Qual. Soc. Res. 2016;17(2) doi: 10.17169/fqs-17.2.2551. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Van Rijnsoever F.J. (I Can't Get No) Saturation: a simulation and guidelines for sample sizes in qualitative research. Derrick G.E., editor. PLoS One. 2017;12(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0181689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that has been used is confidential.