Abstract

While mammals require the essential amino acid tryptophan (Trp) in their diet, plants and microorganisms synthesize Trp de novo. The five-step Trp pathway starts with the shikimate pathway product, chorismate. Chorismate is converted to the aromatic compound anthranilate, which is then conjugated to a phosphoribosyl sugar in the second step by anthranilate phosphoribosyltransferase (PAT1). As a single-copy gene in plants, all fixed carbon flux to indole and Trp for protein synthesis, specialized metabolism, and auxin hormone biosynthesis proceeds through PAT1. While bacterial PAT1s have been studied extensively, plant PAT1s have escaped biochemical characterization. Using a structure model, we identified putative active site residues that were variable across plants and kinetically characterized six PAT1s (Arabidopsis thaliana (thale cress), Citrus sinensis (sweet orange), Pistacia vera (pistachio), Juglans regia (English walnut), Selaginella moellendorffii (spike moss), and Physcomitrium patens (spreading earth-moss)). We probed the catalytic efficiency, substrate promiscuity, and regulation of these six enzymes and found that the C. sinensis PAT1 is highly specific for its cognate substrate, anthranilate. Investigations of site-directed mutants of the A. thaliana PAT1 uncovered an active site residue that contributes to promiscuity. While Trp inhibits bacterial PAT1 enzymes, the six plant PAT1s that we tested were not modulated by Trp. Instead, the P. patens PAT1 was inhibited by tyrosine, and the S. moellendorffii PAT1 was inhibited by phenylalanine. This structure-informed biochemical examination identified variations in activity, efficiency, specificity, and enzyme-level regulation across PAT1s from evolutionarily diverse plants.

Keywords: tryptophan, enzyme kinetics, substrate specificity, plant biochemistry, anthranilate metabolism, metabolic regulation

Plants synthesize an abundance of metabolites to aid in growth and development, defense against pathogens and herbivores, the mitigation of environmental stresses, and reproduction. Many plant secondary and specialized metabolites are synthesized from amino acids or their metabolic intermediates. In plants, the aromatic amino acid tryptophan (Trp) is essential for protein synthesis and is a precursor to auxin growth hormones, alkaloids, niacin (vitamin B3), and anti-herbivory metabolites like indole glucosinolates (1, 2, 3, 4, 5). While plants, fungi, and bacteria have retained the enzymes necessary to synthesize Trp de novo, humans require the essential amino acid Trp from their diet (1, 2). Although Trp is essential for protein synthesis, specialized metabolism, and human health, much of what is known about aromatic amino acid biosynthesis and regulation has been inferred from microbial investigations of these pathways and has largely escaped biochemical investigation in plants.

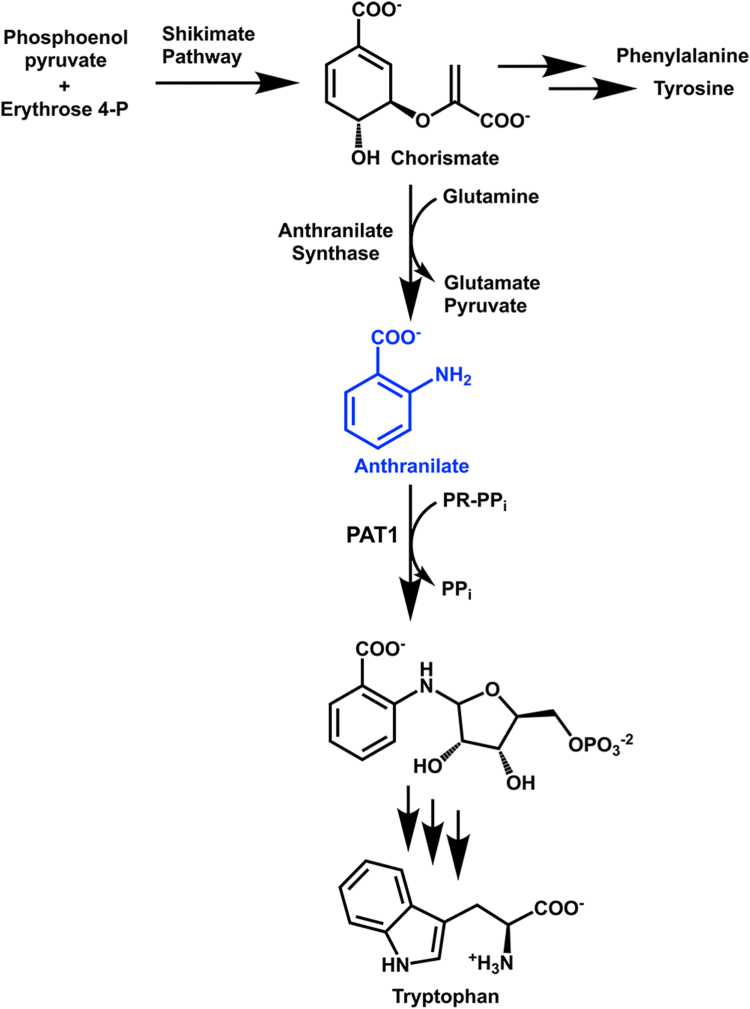

The five-step, plastid-localized Trp pathway starts with chorismate, the product of the shikimate pathway, which is converted to anthranilate (2-aminobenzoate) and pyruvate by anthranilate synthase (AS) (Fig. 1) (6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11). In the second step of the pathway, phosphoribosyl anthranilate transferase (PAT1) transfers a phosphoribosyl sugar onto anthranilate, forming 5-phosphoribosylanthranilate (12, 13, 14). The PAT1, or TRP1, gene was the first Trp pathway enzyme discovered in plants (13). Because PAT1 is a single-copy gene in Arabidopsis, trp1-1 plants are Trp auxotrophs. The trp1 mutants also exhibit blue fluorescence under UV light due to the accumulation of anthranilate β-glucoside (15).

Figure 1.

Anthranilate phosphoribosyltransferase (PAT1) catalyzes the second step in Trp biosynthesis. Phosphoenol pyruvate from glycolysis and erythrose 4-phosphate from the Calvin-Benson cycle are shuttled through the shikimate pathway to generate the precursor of aromatic amino acid biosynthesis, chorismate. Chorismate is then converted to anthranilate, which is phosphoribosylated by PAT1 in the second step of the five-step Trp pathway.

In aromatic amino acid biosynthesis, the first enzyme in the pathway is typically regulated by allosteric effectors (2). In Tyr and Phe biosynthesis, chorismate mutase 1 (CM1) in Arabidopsis thaliana is allosterically inhibited by Phe and Tyr and activated by Trp, while CM3 is activated by all three aromatic amino acids, Cys, and His (16). In Physcomitrium patens, both CM1 and CM2 are allosterically activated by Trp and inactivated by Tyr and Phe, while His is an activator only for CM1 (17). The Selaginella moellendorffii CM is allosterically activated by Trp but is not allosterically regulated by Tyr, Phe, or His. In Trp biosynthesis, AS is feedback regulated through allosteric inhibition by the final pathway product, Trp, although ASαs that are feedback-insensitive to Trp have been identified in rice, common rue, and tobacco (6, 18, 19). While these enzymes at the chorismate branch point are modulated by amino acid effectors, steps within the pathway are regulated by competitive inhibition. For example, arogenate dehydrogenase in Tyr biosynthesis is inhibited by Tyr and prephenate aminotransferase at the branchpoint of Tyr and Phe biosynthesis is inhibited by Cys (20, 21). While feedback inhibition by Trp has been identified in a bacterial PAT, whether or not plant PAT1s are regulated and the molecular determinants of enzyme-level regulation are unknown, and our understanding of the regulation of Trp biosynthetic enzymes remains incomplete (22).

Several examples exist where plants siphon away intermediates in the Trp biosynthesis pathway to use as starting material for building specialized metabolites. In maize, indole-3-glycerol phosphate is drawn from Trp biosynthesis to produce benzoxazinoids, which are used for defense against insect herbivores (4, 23). Anthranilate is methylated in plants such as maize (Zea mays), fox grapes (Vitis labrusca), and strawberries (Fragaria spp.) to generate O-methyl anthranilate, which serves to both attract pollinators and repel herbivores (24, 25, 26, 27). O-Methyl anthranilate is responsible for the recognizable smell of grapes and is used commercially as a grape flavoring agent in foods, beverages, and pharmaceuticals and as a bird deterrent on golf courses (26). In the Citrus family (Rutaceae), N-methyl anthranilate serves as a precursor in acridone alkaloid biosynthesis (28). Acridone, acridine, and their derivatives are toxic to human cell lines and have broad biological activity against bacteria, viruses, and parasites, suggesting that they serve as a chemical defense mechanism in plants (29). As a branch point in primary and specialized metabolism, we hypothesized that plants may modulate anthranilate flux to Trp via PAT1 regulation.

Despite the fundamental role of anthranilate as a precursor to Trp and defensive molecules, PAT1 remains to be biochemically characterized outside of microorganisms. To understand PAT1 enzyme activity, specificity, and regulation, we combined structural comparisons of active site residues with functional assays. Our functional analysis included PAT1s from A. thaliana (thale cress), Citrus sinensis (sweet orange), Pistacia vera (pistachio), Juglans regia (English walnut), S. moellendorffii (spike moss), and P. patens (spreading earth-moss). The PAT1 proteins from these species were selected because the active sites of these enzymes were the most variable, which enabled us to identify residues that may contribute to variations in activity and regulation. While there were many conserved residues in the active sites across these enzymes, they displayed variability in catalytic efficiencies, substrate inhibition, and substrate promiscuity. Key residues in the A. thaliana PAT1 were investigated for their role in substrate specificity, which identified a Ser that is key for limiting non-cognate reactions. We tested four amino acids (Trp, Tyr, Phe, and His) as effectors of each of the plant PAT1s and found that Phe is an inhibitor of the S. moellendorffii PAT1, Tyr is an inhibitor of the P. patens PAT1, and the other four PAT1s were insensitive to amino acid regulation. Our results indicate that plant PAT1s have evolved differential activities, specificities, and modulators based on their metabolic landscapes and selective pressures for balancing Trp biosynthesis with anthranilate-derived specialized metabolism.

Results

Structural comparisons of active site residues across plant PAT1s

To determine the extent of variation across plant PAT1s, we began by visualizing the differences between computed structure models of a PAT1 from A. thaliana, AtPAT1. The location of the active site was confirmed by overlaying an anthranilate-bound archaeal PAT1 structure (PDB: 2GVQ) with the AtPAT1 model (30). The sugar donor, 5-phospho-D-ribose 1-diphosphate (PR-PPi), was docked into the active site, and the PR-PPi-bound structure was used for molecular docking of anthranilate (Fig. 2). X-ray crystal structures have shown that the active sites of microbial PAT1s sit at the hinge region between the N-terminal α-helical domain and a C-terminal α/β domain and contain multiple sites for anthranilate binding, a so-called anthranilate channel, with the S1 site being closest to the PR-PPi to facilitate catalysis and the distal S2 site allowing for substrate capture (31, 32).

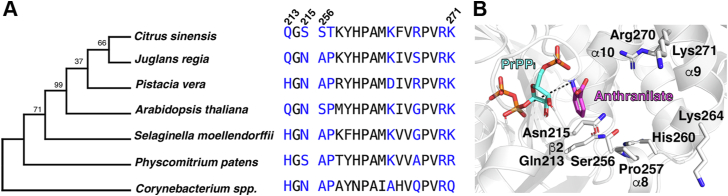

Figure 2.

Phylogeny-guided structural analysis of the PAT1 active site.A, a dendrogram of PAT1 proteins from plants and a microorganism (Corynebacterium spp.) shows the evolutionary relationship among selected PAT1 enzymes. Active site residues for each PAT1 are shown on the left, and residues in blue were within 5 Å of a docking conformation of anthranilate (panel B, magenta). Amino acid numbering is based on the position in the A. thaliana PAT1 protein. B, most identified active site residues are located on the β2 sheet and the α8 and α9 helices. The black dashed line between the amine of anthranilate and PrPPi (phosphoribosyl-pyrophosphate) shows the point at which the transfer reaction occurs.

These anthranilate-bound models allowed us to identify residues that shape the molecular architecture of the active site. Most active site residues fell in two regions on the β2 sheet (213–215) and helix α8 (256–259) and α9 (262–271). There are only three residues within 5 Å of docked anthranilate that are variable between Arabidopsis and Citrus: Pro257 is a Thr in the CsPAT1, Asn215 is a Ser in CsPAT1, and Gly267 is an Arg in CsPAT1. Several charged Lys and Arg residues on helix α9 are highly conserved and are likely involved in electrostatic interactions between the carboxylate of anthranilate (Fig. 2).

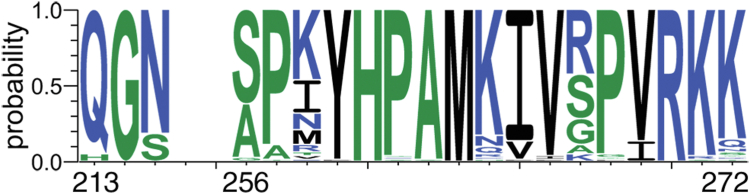

To dig deeper into the variability of PAT1s across plants, we identified an additional 76 PAT1 orthologs across Viridiplantae for active site comparisons (File S1). While some residues were highly conserved (e.g., Gly214, Tyr259, His260, Met263, and Arg270), others were more variable (e.g., positions 256, 258, and 267) (Fig. 3). Instead of testing the role of each residue individually, we reasoned that assaying diverse plant PAT1s would allow us to gain a broader understanding of how these active site residue combinations contribute to the activity, specificity, and regulation of this key Trp biosynthetic enzyme across the plant kingdom. We selected six PAT1s with varied active sites for functional characterization: A. thaliana (thale cress), C. sinensis (sweet orange), P. vera (pistachio), J. regia (English walnut), S. moellendorffii (spike moss), and P. patens (spreading earth-moss).

Figure 3.

Comparisons of 82 plant PAT1 active site residues reveal highly conserved and variable residues. Amino acid numbering is based on the position in the A. thaliana PAT1 protein. Figure was designed using WebLogo3.

Functional characterization of PAT1s

PAT1 uses anthranilate and PR-PPi as substrates in a transferase reaction to form 5-phosphoribosylanthranilate (Fig. 1) (14). To investigate the kinetic differences between the plant PAT1s, the codon-optimized genes were cloned into the IPTG-inducible pET28a protein expression vector for heterologous expression in E. coli. Yields from Ni-NTA affinity purification ranged from 2 to 10 mg/ml. Purified enzymes were assayed using a continuous coupling enzyme reagent that couples PPi release to NADH oxidation at 340 nm. Using this assay, we determined the steady-state kinetics for PAT1s by varying the concentration of anthranilate (Table 1 and Fig. 4).

Table 1.

Steady state kinetics data for PAT1 enzymes with varied anthranilate

| PAT1 protein | KM (μM) | kcat (min−1) | kcat/KM (M−1s−1) | Ki (mM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arabidopsis thaliana | 20.6 ± 2.0 | 7.9 ± 0.1 | 6360 | 4.3 ± 0.4 |

| Citrus sinensis | 22.0 ± 3.3 | 7.0 ± 0.2 | 5320 | 4.1 ± 0.6 |

| Juglans regia | 38.7 ± 3.5 | 3.3 ± 0.1 | 1420 | >5 |

| Physcomitrium patens | 31.8 ± 4.4 | 3.4 ± 0.1 | 1790 | >5 |

| Pistacia vera | 32.1 ± 4.7 | 2.4 ± 0.1 | 1240 | 1.8 ± 0.4 |

| Selaginella moellendorffii | 189 ± 35 | 5.1 ± 0.3 | 450 | 3.6 ± 0.8 |

KM apparent, kcat, and kcat/KM values reported for anthranilate concentrations between 0 and 0.75 mM. Values shown are the mean ± standard error for n = 3.

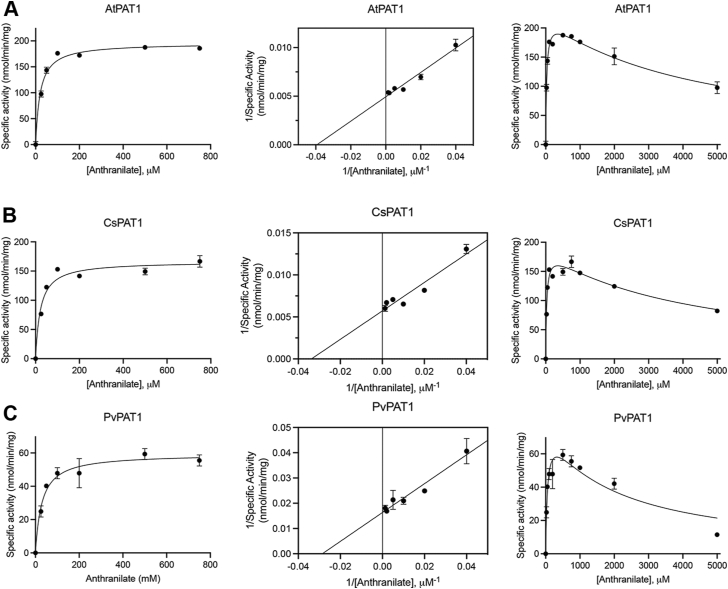

Figure 4.

Kinetic plots of three representative PAT1s. Plots are shown for Arabidopsis thaliana (AtPAT1; A), Citrus sinensis (CsPAT1; B), and Pistacia vera (PvPAT1; C) with varied anthranilate. Data are represented as Michaelis-Menten (left), Lineweaver-Burke (center), and substrate-inhibition (right) plots for varied anthranilate concentrations. Error bars represent standard deviations, where bars are not visible, the standard deviation is too small to visualize. For all points, n = 3.

Across the various PAT1s, the KM values mostly range from 20.6 to 38.7 μM when anthranilate was varied, with the exception of the S. moellendorffii PAT1 which has a notably high KM (189 μM) (Table 1). The A. thaliana and C. sinensis enzymes had the highest kcat (7.9 and 7.0 min−1, respectively) and catalytic efficiencies (6360 and 5320 M−1s−1, respectively) of the PAT1s that we tested. For S. moellendorffii, the high KM value coupled with a moderate turnover rate (5.1 min−1) translated to a low catalytic efficiency (450 M−1s−1), which was the lowest of any of the PAT1s that we assayed. P. vera had the lowest turnover (2.4 min−1) and a catalytic efficiency of 1240 M−1s−1, which is 2.75-fold higher than the S. moellendorffii PAT1 yet 5-fold lower than the A. thaliana PAT1.

Substrate inhibition is a common deviation from Michaelis-Menten kinetics and plays a critical role in regulating metabolic pathways (33). Substrate inhibition with anthranilate has also been reported for Mycobacterium tuberculosis PAT1 (Ki value of 45 μM) and Thermococcus kodakarensis PAT1 (Ki value > 4 μM) (31, 34). While all the PAT1 enzymes also exhibit substrate inhibition kinetics, there was variability in the inhibitory constant (Ki) values, and we were unable to calculate Ki for J. regia and P. patens. The Ki values were 4.3 mM for A. thaliana, 4.1 mM for C. sinensis, and 3.6 mM for S. moellendorffii. However, it is unclear whether anthranilate concentrations would reach 3 to 4 mM or higher in planta. P. vera had the lowest Ki value of 1.8 mM. The other five plant PAT1s have a positively charged Lys in position 264, while the PvPAT1 has a negatively charged Asp in this position, which may account for the low Ki value.

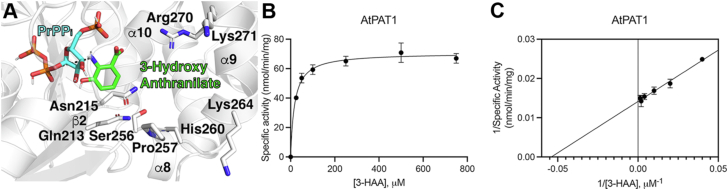

3-Hydroxyanthranilate acts as an alternative substrate of plant PAT1s

To probe the substrate specificities of the plant PAT1s, we assayed the enzymes with the mammalian Trp catabolism intermediate 3-hydroxyanthranilate (3-HAA) as a substrate in vitro. Very little is known about if and how plants break down amino acids, including Trp, and 3-HAA was selected due to its structural similarity to the cognate substrate anthranilate (35). All six plant PAT1s were able to accept 3-HAA as a substrate (Fig. 5 and Table 2). Interestingly, A. thaliana has a similar KM value for 3-HAA (19.63 μM) compared to its KM for anthranilate, while J. regia (28.23 μM) and S. moellendorffii (22.66 μM) have slightly lower KM values compared to anthranilate. Overall turnover rates with 3-HAA as a substrate ranged from 2.1 to 3.2 min−1.

Figure 5.

Plant PAT1s can accept 3-hydroxyanthranilate as a substrate.A, molecular docking shows predicted contacts between 3-HAA (green) and the AtPAT1 active site. Kinetics data for AtPAT1 are represented on (B) Michaelis-Menten and (C) Lineweaver-Burke plots across varied 3-HAA concentrations. Error bars represent standard deviations, and where bars are not visible, the standard deviation is too small to visualize. For all points, n = 3.

Table 2.

Steady state kinetics data for plant PAT1s with varied 3-hydroxyanthranilate

| PAT1 protein | KM (μM) | kcat (min−1) | kcat/KM (M−1s−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arabidopsis thaliana | 19.63 ± 2.3 | 2.9 ± 0.07 | 2470 |

| Citrus sinensis | 1075 ± 300 | 2.3 ± 0.3 | 36.2 |

| Juglans regia | 28.23 ± 4.2 | 2.9 ± 0.1 | 1690 |

| Physcomitrium patens | 99.71 ± 11.2 | 3.2 ± 0.1 | 537 |

| Pistacia vera | 50.03 ± 5.3 | 2.1 ± 0.06 | 711 |

| Selaginella moellendorffii | 22.66 ± 1.5 | 3.2 ± 0.05 | 2360 |

KM apparent, kcat, and kcat/KM values reported for 3-HAA concentrations between 0 and 2 mM for C. sinensis and between 0 and 0.5 mM for all other enzymes. Values shown are the mean ± standard error for n = 3.

Initially, we saw such low activity for 3-HAA with the C. sinensis PAT1 that we did not think that it was able to accept this non-cognate substrate. Upon closer investigation, we were able to calculate Michaelis-Menten kinetics for 3-HAA and show that C. sinensis can use it as a substrate, but the catalytic efficiency with 3-HAA (36.2 M−1s−1) is less than 1% of the activity that the CsPAT1 has with anthranilate, suggesting that the CsPAT1 is highly specific for anthranilate. Similarly, the P. patens and P. vera PAT1s display 3- and 1.75-fold lower catalytic efficiency with 3-HAA compared to anthranilate, respectively.

Conversely, two PAT1s had a catalytic efficiency with the non-cognate substrate that was the same as or higher than with anthranilate. J. regia PAT1 displays a 1.2-fold increased catalytic efficiency with 3-HAA compared to anthranilate, but it is within the standard error of the anthranilate value. The S. moellendorffii PAT1 has a 5-fold higher kcat/KM with 3-HAA compared to anthranilate, which may mean that there has been little selective pressure for the SmPAT1 to evolve high specificity for anthranilate.

Identification of residues that contribute to PAT1 activity and promiscuity

To determine the residues responsible for PAT1 substrate promiscuity, we began by comparing active site sequences to identify residues that are shared among 3-HAA-using PAT1s. Two residues that had previously been noted as varying between the C. sinensis PAT1, which has high specificity for anthranilate, and other PAT1s were Asn215, which is a Ser in CsPAT1, and Pro257, which is a Thr in CsPAT1. To probe the role of these residues in catalysis and substrate specificity, we introduced the N215S and P257T single mutants and the combined N215S/P256T double mutant into the A. thaliana PAT1. If these residues contribute to substrate selectivity, we expected to see reduced activity in the AtPAT1 when the residues from CsPAT1 were introduced. Steady-state kinetics were determined for all three mutants with anthranilate and with 3-HAA (Tables 3 and 4).

Table 3.

Steady state kinetics data for AtPAT1 mutants with varied anthranilate

| Protein | KM (μM) | kcat (min−1) | kcat/KM (M−1s−1) | Ki (mM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AtPAT1 | 20.6 ± 2.0 | 7.9 ± 0.1 | 6360 | 4.3 ± 0.4 |

| AtPAT1 N215S | 24.2 ± 3.7 | 5.2 ± 0.2 | 3570 | >5 |

| AtPAT1 P257T | 42.0 ± 2.1 | 5.8 ± 0.1 | 2320 | 4.5 ± 0.5 |

| AtPAT1 N215S/P257T | 43.4 ± 6.5 | 4.5 ± 0.2 | 1740 | >5 |

KM apparent, kcat, and kcat/KM values reported for anthranilate concentrations between 0 and 0.75 mM. Values shown are the mean ± standard error for n = 3. Data from Table 1 for the A. thaliana PAT1 was included for comparison.

Table 4.

Steady state kinetics data for AtPAT1 mutants with varied 3-hydroxyanthranilate

| Protein | KM (μM) | kcat (min−1) | kcat/KM (M−1s−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arabidopsis thaliana | 19.63 ± 2.3 | 2.9 ± 0.07 | 2470 |

| AtPAT1 N215S | 65.06 ± 5.5 | 2.4 ± 0.06 | 613 |

| AtPAT1 P257T | 35.95 ± 6.1 | 2.9 ± 0.1 | 1360 |

| AtPAT1 N215S/P257T | 60.96 ± 6.4 | 3.1 ± 0.1 | 850 |

KM apparent, kcat, and kcat/KM values reported for 3-HAA concentrations between 0 and 0.5 mM. Values shown are the mean ± standard error for n = 3. Data from Table 2 for the A. thaliana PAT1 was included for comparison.

While the KM value for anthranilate with the AtPAT1 N215S mutant (24.2 μM) was similar to that of the wild-type enzyme (20.6 μM), a reduction in the turnover rate to 5.2 min−1 led to an almost 50% reduction in catalytic activity (Table 3). The AtPAT1 P257T and N215S/P257T mutants doubled the KM value for anthranilate (42.0 and 43.4 μM, respectively) and reduced the turnover rate to 5.8 and 4.5 min−1, respectively. These data suggest that the Asn215 residue is important for enzyme activity and catalysis, while Pro257 may facilitate anthranilate binding.

When assayed with the alternative substrate 3HAA, the AtPAT1 N215S mutant reduced the catalytic efficiency 4-fold compared to the wild-type enzyme (613 versus 2470 M−1s−1; Table 4). This reduction was in part due to the 3.3-fold higher KM value of the mutant (65 μM) and 17% reduction in kcat (2.4 min−1). While the KM and kcat values were also reduced for the P257T mutant, the turnover rate (2.9 min−1) was the same as the wild-type value, which meant that the catalytic efficiency was only reduced by 1.8-fold (1360 M−1s−1) compared to the wild-type enzyme. We did not see an additive effect in the N215S/P257T double mutant. Instead, the enzyme had a further increased turnover rate (3.1 min−1) and a KM value (61 μM) that was closest to that of the N215S single mutant. Taken together, these mutagenesis experiments highlight the role of the Asn215 residue in substrate promiscuity.

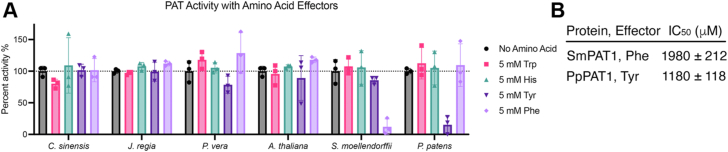

Enzyme-level regulation of PAT1

Although PAT1s lack an allosteric site, we questioned whether these enzymes could be regulated by amino acid effectors. While there is evidence of a bacterial PAT1 from the Gram-positive Brevibacterium flavum (now Corynebacterium glutamicum) being feedback-inhibited by Trp with an IC50 value of 0.15 μM, a regulatory mechanism for eukaryotic PAT1s has not yet been reported (22). Furthermore, the C. glutamicum PAT1 is specific for L-Trp and is not inhibited by Tyr, Phe, His, or D-Trp. In our inhibition assays, we included L-Trp, as well as the other two aromatic amino acids L-Tyr and L-Phe. The broader family of phosphoribosyltransferases catalyze the first step in His biosynthesis, and the A. thaliana ATP-PRT1 and ATP-PRT2 are feedback inhibited by L-His with IC50 values of 40 and 320 μM L-His, respectively (36). Therefore, we also included L-His in our inhibition assays.

None of the six enzymes that we tested were modulated by L-Trp or L-His, and we did not see significant differences in activity for the CsPAT1, JrPAT1, PvPAT1, or AtPAT1 with 5 mM amino acids added to the reaction (Fig. 6). The SmPAT1 was inhibited by 5 mM Phe (12% activity compared to the “no amino acid” control), while PpPAT1 was inhibited by 5 mM Tyr (15% activity compared to the “no amino acid” control). When the concentration of the amino acid was varied, we calculated an IC50 value of 1980 μM for Phe with SmPAT1 and 1180 μM for Tyr with PpPAT1 (Fig. 6). While we are uncertain of the physiological relevance of these IC50 values, this data suggests that if Phe levels were high in S. moellendorffii (or if Tyr levels were high in P. patens), then PAT1 activity would be attenuated.

Figure 6.

Screening amino acid effectors of plant PAT1s.A, plant PAT1s were each assayed with 5 mM Trp, His, Tyr, or Phe, and activity was normalized to a no amino acid control for each enzyme. Error bars represent standard deviations for n = 3. B, inhibition kinetics were determined for SmPAT1 with Phe and PpPAT1 with Tyr by holding anthranilate and PR-PPi constant while varying the concentration of amino acid from 0 to 5 mM. Values shown are the mean ± standard error for n = 3.

Discussion

Since the initial discovery of the TRP1 (PAT1) gene in Arabidopsis, Trp biosynthetic enzymes have remained to be revisited and investigated in the post-genomic era (13). As a single-copy gene in plants, all fixed carbon flux to indole and Trp for protein synthesis, specialized metabolism, and auxin hormone biosynthesis proceeds through PAT1. Here we report the first comprehensive investigation of PAT1 across diverse plants to identify variations in activity, efficiency, specificity, and enzyme-level regulation.

Biochemical investigations of metabolic enzymes usually kinetically characterize one or a few enzymes, but taking a broader approach of studying six variable PAT1 enzymes from plants has enabled us to examine the evolution of combinations of active site residues. Using a combination of structural modeling, active site comparisons, and functional assays, we show that PAT1s across plants as diverse as S. moellendorffii and C. sinensis have evolved varying KM values and catalytic efficiencies (Table 1). Of the plant PAT1 enzymes we tested, P. vera PAT1 had the lowest Ki value at 1.8 mM. The catalytic cycle and binding mechanism, elucidated by structural studies of PAT1 from the tuberculosis-causing M. tuberculosis, could explain why other PAT1s also exhibit substrate inhibition, since binding of multiple anthranilate molecules could prevent folding, trapping pyrophosphate and disrupting catalysis (32). Interestingly, of the PAT1s that we assayed, the P. vera PAT1 is the only plant PAT1 that has an Asp substituted for a Lys at the position that corresponds to 264 in A. thaliana, which implicates that this residue may be responsible for this low Ki value (Fig. 2).

Based on homology to the archaeal Sulfolobus solfataricus PAT1 (SsPAT1), we can infer the importance of several residues in anthranilate binding in plant PAT1s (30). Using an X-ray crystal structure and functional assays for the wild-type and mutant SsPAT1, Arg164 (which corresponds to Arg270 in A. thaliana) was identified as the main determinant for anthranilate recognition and works by coordinating both the carboxyl and amine of anthranilate. Mutating the SsPAT1 His154 (His 260 in AtPAT1) or His107 (Gln213 in AtPAT1) to an Ala had little effect on binding or catalysis, implying that these residues were dispensable. In SsPAT1, the R164A mutant had a 700-fold higher KM value and a 7-fold decrease in kcat, which the authors say implicates this residue in binding but not catalysis. Marino and colleagues suggest that the SsPAT1 Asn109 (Asn215 in AtPAT1) assists Arg164 in binding and orienting anthranilate. We found that the AtPAT1 N215S mutant, when assayed with anthranilate, has a 1.2-fold higher KM value (20.6 μM in wild type to 24.2 μM in the N215S mutant), and the kcat decreased from 7.9 min−1 for wild type to 5.2 min−1 for the mutant (a 34% decrease) (Table 3). This active site Ser residue is also found in PAT1s of grasses (Triticum aestivum (wheat), Oryza spp. (rice), Z. mays (maize), Setaria spp.), Solanum tuberosum (potato), Trifolium pratense (red clover), Medicago truncatula (alfalfa), Prunus avium (sweet cherry), and Prunus dulcis (almond) (File S1).

In our experiments, we noticed that Asn215 is conserved across plant PAT1s that have a high catalytic efficiency with 3-HAA (A. thaliana, J. regia, and S. moellendorffii) and is a Ser in PAT1s that have a low catalytic efficiency with 3-HAA (C. sinensis and P. patens) (Table 2; Figs. 2 and 5). The AtPAT1 N215S mutant has a 3.3-fold higher KM value and only a 20% reduction in kcat, suggesting that this residue is important for binding 3-HAA but not for catalysis (Table 4). Based on docking results, the side chain of either Asn or Ser in position 215 may be positioned to form hydrogen bond interactions with the hydroxyl of 3-HAA (Fig. 2). Because having an Asn in this position leads to a lower KM value with 3-HAA, the slightly larger polar residue, Asn, may more readily form hydrogen bond interactions with 3-HAA compared to the smaller polar amino acid, Ser.

Of the 82 PAT1s that we investigated, only one, the C. sinensis PAT1, has a Thr in the position corresponding to 257 in A. thaliana PAT1. Introducing this Thr into AtPAT1 led to a 2-fold increase in KM for anthranilate and a modest 27% decrease in kcat, suggesting that this residue is responsible for anthranilate binding (Table 3). Because Pro is a nonpolar and conformationally rigid amino acid, replacing it with a polar Thr may allow for hydrogen bond interactions with anthranilate.

Others have shown that the PAT1 found in M. tuberculosis can accept a variety of substrates, including analogs of anthranilate that have been fluorinated or methylated on the aromatic ring (31). To our knowledge, no one has reported 3-hydroxyanthranilate activity for a PAT1 enzyme. Because a Trp catabolism pathway has not been identified in plants, the physiological relevance of this reaction is unknown. We were surprised to find that the SmPAT1 has a 5-fold higher catalytic efficiency with 3-HAA compared to anthranilate, primarily due to the 8-fold reduction in KM with 3-HAA (Tables 1 and 2). On the contrary, 3-HAA activity was almost undetectable with the CsPAT1, suggesting that this enzyme is highly specific for anthranilate. Regardless of the physiological relevance, determining plant PAT1 activity with 3-HAA was a useful proxy for determining substrate specificity and revealed a range of promiscuity across plant PAT1s.

Given the high degree of active site conservation among plant PAT1s compared to the PAT1 from Corynebacterium spp. that is inhibited by Trp, we hypothesized that plant PAT1s may also be inhibited by Trp. On the contrary, we did not detect Trp inhibition for any of the six plant PAT1s that we assayed (Fig. 6). The PAT1s from A. thaliana, C. sinensis, J. regia, and P. vera were insensitive to Trp, Tyr, Phe, and His, while the PAT1 from S. moellendorffii and P. patens were inhibited by Phe and Tyr, respectively (Fig. 6). Because this inhibition is not shared across the plant PAT1s that we assayed, we hypothesize that the ancestor of plant PAT1s may have been sensitive to amino acid effectors and that modern plants are able to regulate the anthranilate branch point effectively and thus are insensitive to amino acid regulation. We were surprised that the two PAT1s from non-seed plants exhibited amino acid sensitivity, while the PAT1s from angiosperms were insensitive to regulation by Tyr, Phe, Trp, and His. Future experiments are needed to reveal the molecular evolution of amino acid sensitivity in non-seed versus seed plants.

Taken together, our findings have led us to hypothesize that because species in the Citrus family (Rutaceae) synthesize anthranilate-derived specialized metabolites like acridone alkaloids, PAT1 has evolved to compete with anthranilate-using enzymes in specialized metabolism. Arabidopsis and other Brassicaceae family members are not known to produce N- and O-methyl anthranilate, and the selective pressure for high substrate specificity may be reduced. This competition for anthranilate may have led to the high substrate selectivity that is exhibited by CsPAT1. Because Trp is a precursor to a number of industrially valuable molecules, such as inks, dyes, edible essences, and plant growth hormones, using the CsPAT1 for metabolic engineering would be ideal because of its high catalytic efficiency, high fidelity, and insensitivity to feedback regulation (37).

In summary, we report the first biochemical investigation of plant PAT1s. We examined the activity, specificity, and regulation of six enzymes, which informs our understanding of the molecular evolution of Trp biosynthesis in plants.

Experimental procedures

Phylogenetic analysis and sequence comparisons of PAT1 proteins

Amino acid sequences for the PAT1 proteins from A. thaliana (NP_197300.1), C. sinensis (XP_006476804.2), J. regia (XP_035550096.1), P. vera (XP_031287690.1), P. patens (XP_024400584.1), S. moellendorffii (XP_024516100.1), and Corynebacterium spp. (WP_004567950.1) were obtained from NCBI. Full-length amino acid sequences were aligned using MUSCLE with UPGMA clustering, and a maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree was produced using 1000 bootstrap replicates with MEGA X v10.1.8 via the Whelan and Goldman model and a discrete Gamma distribution to model evolutionary rate differences among sites (38).

Docking and molecular visualization of PAT1 proteins

An AI-generated structure of the A. thaliana PAT1 (Uniprot A0A178U8D1) was downloaded from the AlphaFold Protein Structure Database (alphafold.ebi.ac.uk). Phosphoribosyl pyrophosphate (PR-PPi) was docked into the active site using AutoDock Vina (ver. 1.5.6) with grid box dimensions of 40 × 40 × 40 Å and the exhaustiveness set to 8 (39, 40). The PR-PPi-bound model of the Arabidopsis PAT1 was used to perform docking with anthranilate and 3-hydroxyanthranilate using the same grid box dimensions. Docking results were visualized using PyMOL (version 2.5.4).

Putative active site amino acids that were within 5 Å of docked anthranilate were noted for their potential role in catalysis. Residues fell within positions 213 to 215 and 256 to 271 in A. thaliana PAT1. To compare PAT1 active site residues across plants, the AtPAT1 amino acid sequence (AAB02913.1) was used as a query in an NCBI protein-protein BLAST search against the Reference Proteins database. Amino acid sequences across 82 diverse plant lineages were selected for comparison and aligned using Clustal Omega. Residue conservation and variability was graphically visualized using WebLogo 3.7.12 (41).

PAT1 protein expression and purification

The PAT1 amino acid sequences were used for codon-optimized gene synthesis and cloning into the pET28a expression vector (Twist Biosciences). A 5 ml LB culture of E. coli BL21 (DE3) harboring the PAT1-containing pET28a plasmid was grown overnight at 37 °C and 225 rpm. The following day, 1 ml of this culture was used to inoculate a 50 ml LB culture supplemented with kanamycin, which was then grown for approximately 16 h at 37 °C and 225 rpm. One-liter cultures of Terrific broth supplemented with kanamycin were inoculated with 25 ml of the 50 ml overnight culture, and the cells were grown at 37 °C and 225 rpm until A600nm was between 0.6 and 0.8. At this point, protein expression was induced using a final concentration of 1 mM IPTG (isopropyl ß-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside). After an approximately 16-h incubation at 16 °C, cells were pelleted by centrifugation (5000g; 15 min) and resuspended in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 500 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole, 10% glycerol, and 1% Tween-20). Following sonication, cell debris was cleared by centrifugation (13,000g; 60 min) and the resulting lysate was passed over a Ni2+-nitrilotriacetic acid (ThermoScientific) column equilibrated in one column volume of the lysis buffer. The column was washed (50 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 500 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole, and 10% glycerol), and bound His-tagged protein was eluted (50 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 500 mM NaCl, 250 mM imidazole, and 10% glycerol). Protein aliquots were stored at −80 °C. Protein concentration was determined by the Bradford method (Bio-Rad) with bovine serum albumin as standard.

Site-directed mutagenesis cloning

The codon-optimized AtPAT1 gene in the pET28a plasmid was used as a template for mutagenesis PCR, and oligonucleotides were designed using PrimerX (https://www.bioinformatics.org/primerx/) (Table S1). Mutations were introduced using the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis method (Agilent), and the successful introduction of each mutation was determined by Sanger sequencing (Azenta). Each construct was transformed into E. coli BL21 (DE3) competent cells (New England Biolabs) for heterologous protein expression and purification. Site-directed mutants of PAT1 were expressed and purified using the same methods as wild-type proteins.

Steady-state kinetic analysis of wild-type and mutant PAT1 enzymes

The transfer of a phosphoribosyl group onto anthranilate was detected by coupling pyrophosphate release from phosphoribosyl pyrophosphate to NADH oxidation at 340 nm using the pyrophosphate reagent, which fructose-6-phosphate kinase (pyrophosphate-dependent), aldolase, triosephosphate isomerase, and α-glycerophosphate dehydrogenase (Millipore Sigma). Following the manufacturer’s instructions, one vial of pyrophosphate reagent was resuspended in 4 ml of milliQ water with a final buffer concentration of 45 mM imidazole HCl (pH 7.4). Phosphoribosyl pyrophosphate (1 mM; Cayman Chemical) was held constant, and the PAT1 enzymes were assayed with anthranilate (Millipore Sigma) or 3-hydroxyanthranilate (0–5 mM; Cayman Chemical) in a final volume of 100 μl in a 96-well plate. Assays were performed at 30 °C and were initiated by the addition of 5 μg of enzyme. Two moles of NADH were oxidized to NAD+ for everyone 1 mol of pyrophosphate was consumed, which was taken into account in our specific activity calculations. Initial velocity data were fit to the Michaelis-Menten or substrate inhibition equation using GraphPad Prism (version 9.5.1).

Amino acid inhibition assays

Amino acid inhibition of PAT1 proteins was screened using an EnzChek Pyrophosphate Assay Kit (ThermoFisher), which couples pyrophosphate release to an inorganic pyrophosphatase and a purine nucleoside phosphorylase (PNP). Reactions were buffered using the provided reaction buffer (50 mM Tris HCl, pH 7.5, 1 mM MgCl2, and 0.1 mM sodium azide) and contained 10 μg of the PAT1 enzyme, 0.5 mM anthranilate, 1 mM phosphoribosyl pyrophosphate, and 5 mM of either Trp, His, Phe, or Tyr amino acids (Millipore Sigma) in a final volume of 100 μl. Assays were performed at 30 °C at 360 nm to detect the conversion of 2-amino-6-mercapto-7-methylpurine ribonucleoside by PNP and were initiated by the addition of PAT1 substrates, per the manufacturer’s instructions.

Data availability

All data are contained within the manuscript.

Supporting information

This article contains supporting information.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Holland lab and Steve Swoap for their critical reading of and feedback on this work.

Author contributions

M. L. and C. K. H. conceptualization; M. L., H. T., and C. G. D. investigation; M. L., H. T., and C. K. H. formal analysis; M. L. and C. K. H. visualization; M. L. and C. K. H. writing–original draft; H. T. and C. K. H. writing–review and editing; C. K. H. supervision; C. K. H. project administration; C. K. H. funding acquisition.

Funding and additional information

This research was supported by funds from Williams College and the U.S. National Science Foundation (MCB-2214883 to C. K. H.). M. L. and H. T. were funded by the American Society of Plant Biologists through a Summer Undergraduate Research Fellowship.

Reviewed by members of the JBC Editorial Board. Edited by Sarah E. O'Connor

Supporting information

References

- 1.Tzin V., Galili G. The biosynthetic pathways for shikimate and aromatic amino acids in Arabidopsis thaliana. Arabidopsis Book. 2010;8 doi: 10.1199/tab.0132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maeda H., Dudareva N. The shikimate pathway and aromatic amino acid biosynthesis in plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2012;63:73–105. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042811-105439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Howe G.A., Jander G. Plant immunity to insect herbivores. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2008;59:41–66. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.59.032607.092825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhou S., Richter A., Jander G. Beyond defense: multiple functions of benzoxazinoids in maize metabolism. Plant Cell Physiol. 2018;59:1528–1533. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcy064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sønderby I., Geu-Flores F., Halkier B. Biosynthesis of glucosinolates–gene discovery and beyond. Trends Plant Sci. 2010;15:283–290. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2010.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tozawa Y., Hasegawa H., Terakawa T., Wakasa K. Characterization of rice anthranilate synthase α-subunit genes OASA1 and OASA2. Tryptophan accumulation in transgenic rice expressing a feedback-insensitive mutant of OASA1. Plant Physiol. 2001;126:1493–1506. doi: 10.1104/pp.126.4.1493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Inaba Y., Brotherton J.E., Ulanov A., Widholm J.M. Expression of a feedback insensitive anthranilate synthase gene from tobacco increases free tryptophan in soybean plants. Plant Cell Rep. 2007;26:1763–1771. doi: 10.1007/s00299-007-0381-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Romero R.M., Roberts M.F., Phillipson J.D. Anthranilate synthase in microorganisms and plants. Phytochemistry. 1995;39:263–276. doi: 10.1016/0031-9422(95)00010-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Niyogi K.K., Last R.L., Fink G.R., Keith B. Suppressors of trp1 fluorescence identify a new arabidopsis gene, TRP4, encoding the anthranilate synthase β subunit. Plant Cell. 1993;5:1011–1027. doi: 10.1105/tpc.5.9.1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Niyogi K.K., Fink G.R. Two anthranilate synthase genes in arabidopsis: defense-related regulation of the tryptophan pathway. Plant Cell. 1992;4:721–733. doi: 10.1105/tpc.4.6.721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ishihara A., Matsuda F., Miyagawa H., Wakasa K. Metabolomics for metabolically manipulated plants: effects of tryptophan overproduction. Metabolomics. 2007;3:319–334. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rose A.B., Casselman A.L., Last R.L. A phosphoribosylanthranilate transferase gene is defective in blue fluorescent Arabidopsis thaliana tryptophan mutants. Plant Physiol. 1992;100:582–592. doi: 10.1104/pp.100.2.582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Last R.L., Fink G.R. Tryptophan-requiring mutants of the plant Arabidopsis thaliana. Science. 1988;240:305–310. doi: 10.1126/science.240.4850.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Radwanski E.R., Last R.L. Tryptophan biosynthesis and metabolism: biochemical and molecular genetics. Plant Cell. 1995;7:921–934. doi: 10.1105/tpc.7.7.921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Quiel J.A., Bender J. Glucose conjugation of anthranilate by the Arabidopsis UGT74F2 glucosyltransferase is required for tryptophan mutant blue fluorescence. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:6275–6281. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211822200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Westfall C.S., Xu A., Jez J.M. Structural evolution of differential amino acid effector regulation in plant chorismate mutases. J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289:28619–28628. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.591123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kroll K., Holland C.K., Starks C.M., Jez J.M. Evolution of allosteric regulation in chorismate mutases from early plants. Biochem. J. 2017;474:3705–3717. doi: 10.1042/BCJ20170549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bohlmann J., Lins T., Martin W., Eilert U. Anthranilate synthase from Ruta graveolens: duplicated ASα genes encode tryptophan-sensitive and tryptophan-insensitive isoenzymes specific to amino acid and alkaloid biosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 1996;111:507–514. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.2.507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Song H.S., Brotherton J.E., Gonzales R.A., Widholm J.M. Tissue culture-specific expression of a naturally occurring tobacco feedback-insensitive anthranilate synthase. Plant Physiol. 1998;117:533–543. doi: 10.1104/pp.117.2.533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schenck C.A., Holland C.K., Schneider M.R., Men Y., Lee S.G., Jez J.M., et al. Molecular basis of the evolution of alternative tyrosine biosynthetic routes in plants. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2017;13:1029–1035. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holland C.K., Berkovich D.A., Kohn M.L., Maeda H., Jez J.M. Structural basis for substrate recognition and inhibition of prephenate aminotransferase from Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2018;94:304–314. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sugimoto S., Shiio I. Regulation of tryptophan biosynthesis by feedback inhibition of the second-step enzyme, anthranilate phosphoribosyltransferase, in Brevibacterium flavum. Agric. Biol. Chem. 1983;47:2295–2305. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Richter A., Powell A.F., Mirzaei M., Wang L.J., Movahed N., Miller J.K., et al. Indole-3-glycerolphosphate synthase, a branchpoint for the biosynthesis of tryptophan, indole, and benzoxazinoids in maize. Plant J. 2021;106:245–257. doi: 10.1111/tpj.15163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Köllner T.G., Lenk C., Zhao N., Seidl-Adams I., Gershenzon J., Chen F., et al. Herbivore-induced SABATH methyltransferases of maize that methylate anthranilic acid using S-adenosyl-L-methionine. Plant Physiol. 2010;153:1795–1807. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.158360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang Y., Cuenca J., Wang N., Liang Z., Sun H., Gutierrez B., et al. A key ‘foxy’ aroma gene is regulated by homology-induced promoter indels in the iconic juice grape ‘Concord’. Hortic. Res. 2020;7:67. doi: 10.1038/s41438-020-0304-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang J., De Luca V. The biosynthesis and regulation of biosynthesis of Concord grape fruit esters, including “foxy” methylanthranilate. Plant J. 2005;44:606–619. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02552.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pillet J., Chambers A.H., Barbey C., Bao Z., Plotto A., Bai J., et al. Identification of a methyltransferase catalyzing the final step of methyl anthranilate synthesis in cultivated strawberry. BMC Plant Biol. 2017;17:1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12870-017-1088-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rohde B., Hans J., Martens S., Baumert A., Hunziker P., Matern U. Anthranilate N-methyltransferase, a branch-point enzyme of acridone biosynthesis. Plant J. 2008;53:541–553. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gensicka-Kowalewska M., Cholewiński G., Dzierzbicka K. Recent developments in the synthesis and biological activity of acridine/acridone analogues. RSC Adv. 2017;7:15776–15804. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marino M., Deuss M., Svergun D.I., Konarev P.V., Sterner R., Mayans O. Structural and mutational analysis of substrate complexation by anthranilate phosphoribosyltransferase from Sulfolobus solfataricus. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:21410–21421. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601403200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cookson T.V.M., Castell A., Bulloch E.M.M., Evans G.L., Short F.L., Baker E.N., et al. Alternative substrates reveal catalytic cycle and key binding events in the reaction catalysed by anthranilate phosphoribosyltransferase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Biochem. J. 2014;461:87–98. doi: 10.1042/BJ20140209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Scully T.W., Jiao W., Mittelstädt G., Parker E.J. Structure, mechanism and inhibition of anthranilate phosphoribosyltransferase. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2023;378:1–9. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2022.0039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yoshino M., Murakami K. Analysis of the substrate inhibition of complete and partial types. Springerplus. 2015;4:292. doi: 10.1186/s40064-015-1082-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Perveen S., Rashid N., Tang X.F., Imanaka T., Papageorgiou A.C. Anthranilate phosphoribosyltransferase from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Thermococcus kodakarensis shows maximum activity with zinc and forms a unique dimeric structure. FEBS Open Bio. 2017;7:1217–1230. doi: 10.1002/2211-5463.12264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hildebrandt T.M., Nunes Nesi A., Araújo W.L., Braun H.P. Amino acid catabolism in plants. Mol. Plant. 2015;8:1563–1579. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2015.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ohta D., Fujimori K., Mizutani M., Nakayama Y., Kunpaisal-Hashimoto R., Munzer S., et al. Molecular cloning and characterization of ATP-phosphoribosyl transferase from Arabidopsis, a key enzyme in the histidine biosynthetic pathway. Plant Physiol. 2000;122:907–914. doi: 10.1104/pp.122.3.907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xiao S., Wang Z., Wang B., Hou B., Cheng J., Bai T., et al. Expanding the application of tryptophan: industrial biomanufacturing of tryptophan derivatives. Front. Microbiol. 2023;14:1–16. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2023.1099098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kumar S., Stecher G., Li M., Knyaz C., Tamura K. MEGA X: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018;35:1547–1549. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msy096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Trott O., Olson A.J. AutoDock Vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 2010;31:455–461. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Eberhardt J., Santos-Martins D., Tillack A.F., Forli S. AutoDock Vina 1.2.0: new docking methods, expanded force field, and Python bindings. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2021;61:3891–3898. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.1c00203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Crooks G.E., Hon G., Chandonia J.M., Brenner S.E. WebLogo: a sequence logo generator. Genome Res. 2004;14:1188–1190. doi: 10.1101/gr.849004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data are contained within the manuscript.