Abstract

Introduction:

The WHO Regional Office for Europe developed the Guide to tailoring immunization programmes (TIP), offering countries a process through which to diagnose barriers and motivators to vaccination in susceptible low vaccination coverage and design tailored interventions. A review of TIP implementation was conducted in the European Region.

Material and methods:

The review was conducted during June to December 2016 by an external review committee and was based on visits in Bulgaria, Lithuania, Sweden and the United Kingdom that had conducted a TIP project; review of national and regional TIP documents and an online survey of the Member States in the WHO European Region that had not conducted a TIP project. A review committee workshop was held to formulate conclusions and recommendations.

Results:

The review found the most commonly cited strengths of the TIP approach to be the social science research as well as the interdisciplinary approach and community engagement, enhancing the ability of programmes to “listen” and learn, to gain an understanding of community and individual perspectives. National immunization managers in the Region are generally aware that TIP exists and that there is strong demand for the type of research it addresses. Further work is needed to assist countries move towards implementable strategies based on the TIP findings, supported by an emphasis on enhanced local ownership; integrated diagnostic and intervention design; and follow-up meetings, advocacy and incentives for decision-makers to implement and invest in strategies.

Conclusions:

Understanding the perspectives of susceptible and low-coverage populations is crucial to improving immunization programmes. TIP provides a framework that facilitated this in four countries. In the future, the purpose of TIP should go beyond identification of susceptible groups and diagnosis of challenges and ensure a stronger focus on the design of strategies and appropriate and effective interventions to ensure long-term change.

Keywords: Vaccine demand, Vaccination coverage, Tailoring immunization programmes, Behavioural science, Health-seeking behavior, Vaccine hesitancy, Review

1. Introduction

The success of immunization programmes is one of the reasons why many countries in the World Health Organization (WHO) European Region (hereafter the Region) enjoy some of the highest life expectancy levels in the world. However, sub-optimal vaccination coverage, often in specific population pockets, poses a continuous threat of outbreaks of preventable disease and death and jeopardizes further progress towards disease elimination [1]. This has been illustrated by the current measles outbreaks in Belgium, Germany, Italy, Romania and Tajikistan [2]. The European Vaccine Action Plan 2015–2020 identifies tailored, innovative strategies as critical in reaching population groups with sub-optimal vaccination coverage [3].

Prompted by the European Technical Advisory Group of Experts on Immunization, in 2012 the WHO Regional Office for Europe developed the Tailoring Immunization Programmes (TIP) approach [4]. TIP offers a step-wise model and a theoretical framework for country processes, guided by principles of broad stakeholder and beneficiary engagement and listening. Drawing on behavioural science, social marketing and qualitative and quantitative research, the TIP approach offers countries a process through which to (1) identify and characterize population groups with low uptake; (2) diagnose vaccination behaviour barriers and motivators and segment target groups based on this; and lastly (3) develop interventions that tailor not only how services are promoted but how they are delivered to overcome barriers and increase vaccination coverage.

The intention with TIP was to inspire the traditionally more supply-oriented immunization programmes to apply a more people-centred and comprehensive approach, built on listening to the intended beneficiaries and taking into account the complexity and the wide range of factors influencing vaccination uptake. These include not only individual motivation, attitudes and beliefs, but to a high degree social, community and cultural factors as well as legislative, institutional and structural factors [5]. Between 2012 and 2016, the TIP approach was applied and tested in four countries in the Region, and was also adapted for seasonal influenza and antimicrobial resistance programmes, with additional projects in four countries. WHO provided technical support in all projects; however to varying degrees ranging from being a driving force together with national coordinators to limiting activities to engagement in workshops and ongoing feedback when requested.

From the beginning, WHO aimed to continuously refine the approach. Encouraged by the Strategic Advisory Group of Experts Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy, which in 2014 identified tailored strategies as critical to address vaccine hesitancy [6], WHO Regional Office for Europe in 2016 asked a team of external experts to review TIP implementation. The group was specifically asked to explore the use, usefulness and effectiveness of the TIP approach for national routine immunization programmes, providing recommendations for the next phase of development for this approach. The terms of reference were to: (1) assess the knowledge, understanding and attitudes to TIP as well as the decision-making process and concerns in relation to implementation in countries; (2) document the outcome and impact of TIP and lessons learned in countries that have conducted TIP projects; and (3) identify areas within the existing approach and guidance material that require revision.

2. Materials and methods

The WHO Regional Office for Europe coordinated the review during June to December 2016 using an external expert committee, representing behavioural science academics as well as international organizations working with vaccination demand issues globally. The review process followed the terms of reference which were fit for purpose – rather than following a formalized evaluation framework, these were specifically oriented to the unique nature of TIP, being heterogeneous in its implementation, and the questions posed by WHO.

In addition to regular committee telephone meetings to discuss the framework and focus, activities and preliminary outcome of activities, the review was based on visits to four countries that had conducted TIP projects (Bulgaria, Lithuania, Sweden and the United Kingdom), review of national and regional TIP documents and an online survey of the 46 Member States in the Region that had not conducted a TIP project. The outcome was a review report [7].

2.1. Review visits

Three countries had completed TIP processes to diagnose barriers and enablers to vaccination in specific population groups, and received review visits (Bulgaria, Sweden, United Kingdom). Two TIP projects were ongoing and therefore not included (Germany, Kazakhstan). While the focus was on routine immunization, one TIP project on flu vaccination was included to learn from the full range of vaccine-related TIP projects (Lithuania). Review visits lasted 4–5 days and were conducted by 1–3 experts committee member along with a WHO coordinator as an observer. The visits involved semi-structured interviews with a broad range of key stakeholders (from 10 in the United Kingdom to 23 in Lithuania) who had participated in, or been observers of, the process. They included representatives of the Ministry of Health and national and sub-national health and immunization institutions as well as community representatives, frontline health workers, non-governmental organizations, research institutions and others. An interview guide was developed and modified by the expert committee and piloted outside the European Region within a country that was also using the TIP approach. The interview guide covered the pre-TIP context; activities and methods used; utilization, usefulness and value of the guidance material and technical support from WHO; implementation of interventions following research and suggestions for TIP in the future. Interviews resulted in a country report based on a fixed template with conclusions and recommendations regarding the respective national TIP processes and implementation, and with recommendations for the regional TIP review report.

2.2. Online survey

In a web-based survey conducted in November 2016, national immunization programme managers were asked about their views on challenges related to vaccination uptake, need for and experience with behavioural insights and behaviour change interventions in their country, plans for and capacity and resources available to conduct such work as well as their perceptions of the TIP itself. The questionnaire was developed in English by the expert committee and translated into Russian. The survey was pretested in both languages over two rounds with 12 test respondents. The final questionnaire included 15 closed questions and eight open-ended questions. At the end of the survey, an optional question invited respondents to give their names and contact information. The survey was sent by the WHO Regional Office for Europe via a link in an email to 69 respondents (the national immunization manager in each Member State and an additional person with a similar position in 23 Member States). A reminder was sent a week after the initial invitation.

2.3. Data analysis

National and regional TIP documents were reviewed by the expert committee prior to the four country visits. Information was summarized according to five main themes defined in a review framework developed for the purpose: (1) the situation leading to TIP implementation; (2) the rationale for applying the TIP approach; (3) the TIP process; (4) the outcome and impact of applying TIP in the country and (5) each country’s recommendations for further development of the TIP approach. Notes were taken during semi-structured interviews with key stakeholders along the main themes discussed in a generic interview guide. Notes were used to complete and revise the information retrieved from the written documents and to develop country-specific reports. Each country’s findings were discussed in the expert committee to reach consensus on the main points of the review. After the four review visits, a three-day workshop of the expert committee was held to compare findings from each country, agree on to the general conclusions and recommendations and prepare an review report [8].

For the online survey, respondents with more than 10% missing responses were excluded. Descriptive statistics were generated for all closed-ended responses. Content analysis was conducted on the open-ended responses. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Inc., Cary, N.C., USA).

3. Results

3.1. Review visits

Table 1 briefly summarizes the TIP projects that were evaluated. Countries varied in how they undertook and experienced the TIP process. Nevertheless, common strengths and challenges were identified that cut across the country contexts.

Table 1.

Summary of expert panel TIP review findings by topic area and Member State.

| Bulgaria | Lithuania | Sweden | United Kingdom | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year initiated | 2012 | 2014 | 2013 | 2014 |

| Background | Suboptimal childhood vaccination coverage, especially among vulnerable (mainly Roma) populations causing large measles outbreak in 2009–2011 | Very low uptake of seasonal influenza (flu) vaccination among pregnant women (<1%) | Suboptimal childhood vaccination coverage among three communities: anthroposophic community [6]; Somali migrants; undocumented migrants | Suboptimal childhood vaccination coverage among an ultraorthodox Charedi Jewish community in north London resulting in recurrent outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases |

| Project initiation | TIP pilot project with considerable WHO support and engagement as part of the development of the TIP guide | TIP pilot project led by WHO as part of the development of a new TIP FLU guide for pregnant women | Initiated by national public health agency’s immunization programme team, with considerable process support from WHO | Initiated by national interdisciplinary project team with modest WHO engagement and support |

| Project elements | Workshop with key stakeholders resulting in situation analysis (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats: SWOT) Extensive qualitative and quantitative research conducted by independent research agency Workshop with key stakeholders to discuss findings and recommendations and define interventions | Situation analysis based on stakeholder consultation Qualitative research with pregnant women and health workers Pilot intervention developed in parallel with formative research Communication materials developed, pretested and implemented Outreach training of health workers to sensitize on benefits of maternal flu vaccine |

Situation analysis based on stakeholder workshop Review of coverage data Reference groups Stakeholder meetings In-depth interviews Conducted in the three communities (four core staff including master thesis projects) Intervention design and early implementation and evaluation planning in one community (Somali) |

Situation analysis based on workshops with engagement of multiple stakeholders Literature review Outbreak and surveillance data analysis Community engagement Questionnaire survey Qualitative research through indepth interviews with community representatives and key informants Stakeholder workshop to define strategies and interventions |

| Results | Recommendations for interventions made, but to date not implemented owing to limited staff and resources Process considered very valuable for the immunization programme in obtaining new information about critical target groups TIP guide published, including case examples from Bulgaria |

Communication interventions implemented, evaluated/refined and extended to broader areas Flu vaccination included as standard question on pregnancy card Flu vaccination included in new guidelines for antenatal care |

Decision to intervene in the Somali community initially: lectures, video, peer-to-peer, training communication skills of nurses and others Possible interventions in the other two communities, but awaiting outcome of the Somali community interventions before implementation |

National TIP report (launched December 2016) with recommendations for tailoring vaccination services to be used for advocacy Initial interventions among those recommended being initiated. Negotiations between commissioning and service provision partners initiated. |

| Evaluation of impact | No evaluation conducted | Materials tested with the target group twice, guiding messages and visual identity Evaluation conducted based on data from questionnaire survey analysis of vaccine coverage data Flu vaccination coverage in the district increased to 107 pregnant women in 2015–16, compared to only six in the season before |

Plan to evaluate impact in 2017 Plan for ongoing surveys of attitudes and demographics associated with undervaccinated groups to signal future areas of focus | Monitoring and evaluation of interventions included in the list of recommendations in the report |

| Examples of insights gained | Many doctors – themselves not from vulnerable communities – perceived that vulnerable communities had a low health culture, leading to mistrust and false assumptions regarding their information needs. In response, the Roma health mediator programme offered a tangible and positive way to support vaccination services by providing vaccination communications and counselling. Other solutions are continuous education and job aids for doctors | It was clear that flu vaccination had not been integrated into health workers’ routines with pregnant women, and that they generally did not support it. This suggested that information and training was needed, as well as a routine “tick box” question on flu vaccination on the standard pregnancy card, prompting health workers to recommend flu vaccination to pregnant mothers | The Somali parents were worried about the incidence of autism in their community. Health workers were hesitant to mention autism in relation to vaccination, causing them to not meet this specific information need of parents. Seminars were held to address vaccination and to help parents understand early signs of autism, enabling them to be reassured when children are displaying normal behaviours misjudged as signs of autism. The seminars both address a need in the community and strengthen the capacity of nurses to discuss autism | There was no (religious or other) resistance to vaccination in the community, but also no community support for vaccination. In an extremely adherent community, social norms are critical. In response, efforts were made to strengthen immunization as a social norm. Convenience, such as opening hours and child-friendly facilities – for the families who often have many children – were critical |

As illustrated in Table 2, many participants perceived value in the TIP process, and cited a number of positive if indirect outcomes, including new insights gained, relationships established and the value of questioning assumptions.

Table 2.

Outcomes of the process of engagement required by the qualitative research component of TIP.

| Outcomes | Description |

|---|---|

| Insights gained and relationships established merely through assembling a diverse group of stakeholders for a common discussion | TIP projects included stakeholder workshops to initiate the process; discuss research outcomes; design strategies to increase coverage – to leverage the collective knowledge of community representatives, front line health workers, academia, experts, national and sub-national health authorities, professional associations, NGOs to gain broader insights |

| Programme value in adopting a participatory approach and listening to the points of view of communities which result in increased clarity about relevant characteristics and points of view of susceptible populations | Focus group interviews, key informant interviews, community stakeholder workshops, often conducted based on insights from broader questionnaire-based surveys, provided new insights and understanding of the complexity of barriers and enablers to vaccination |

| Questioning (previous) assumptions based on insights and dialogue | As an example, in the United Kingdom there was an assumption that there was community resistance and distrust against vaccination in the Charedi community; however, the main barrier was related to the convenience of vaccination services |

| Opening lines of communication that did not previously exist | The broad stakeholder engagement from the very first step of the process allowed new partnerships and alliances |

| Receptiveness to considering changing aspects of service delivery, not only focusing on communication | Insights provided a multifaceted understanding of issues and challenges, including some related to information needs; however, in no cases was information deficit the main barrier to vaccination |

| Increase understanding of and interest for qualitative and people-centred approaches | The value of qualitative approaches was highlighted as a particular advantage among stakeholders with a background in the health sciences, especially in cultural settings where the greater valuing of the collective in how health systems are run made user-centred design more novel |

One common theme across countries was a strong focus on community engagement and consideration of the wide range of behavioural determinants affecting vaccine uptake, including those related to ability, motivation and opportunity. According to participants, this made the approach suitable for working with communities and individuals with complex and multifactorial challenges. In each case the key innovation of the TIP approach involved openness to tailoring service delivery to the needs of communities. Examples include the Charedi community in the United Kingdom, Roma communities in Bulgaria and Somali communities in Sweden. Applications of TIP there seem to have been productive at yielding socially acceptable and appropriate intervention ideas. However, experience in reviewed countries shows that the TIP method can also be applied more broadly to self-identified groups, such as pregnant women in Lithuania. While such groups may not have an identifiable leadership that can be engaged in the TIP process, they may still provide insights into behavioural norms or common beliefs that can be used to tailor immunization practice. The potential value of profiling and segmenting into target groups is highlighted as an opportunity here.

A further common theme was the critical importance of TIP leadership. In countries that relied heavily on WHO engagement and technical assistance there was a risk of reduced ownership and leadership of the process. Without a local sense of ownership and a focal person or team to bring stakeholders through the TIP process, the follow-through and sustainability of recommended interventions was often dependent on the continued involvement of WHO.

The engagement of WHO was generally highly valued and appreciated; the fact that the approach was developed by WHO was seen as a mark of quality and an important aspect in the decision to use it across settings.

A final theme across contexts was the difficulty of translating formative research from the formative phase into to the subsequent steps of implementation of practical interventions. For the formative phase, the current version of the TIP guide was recognized as strong for segmenting susceptible populations and diagnosing barriers and enablers to uptake. However, for the next steps of translating recommendations into discrete interventions and changing service delivery culture, countries indicated that the current TIP guide alone was often not sufficient. Although stakeholder engagement was recognized as critical, many participants also emphasized their surprise at the amount of time and technical skill involved in the process. For the future, a clearer description of the steps of the TIP process will be needed.

3.2. Online survey

Forty responses were received in total, of which 16 were anonymous. Of the 24 non-anonymous responses, two were from the same country which means that a minimum of 31 and a maximum of 39 Member States (67–85%) responded. Four responses containing answers to only two questions were excluded, leaving a total of 36 questionnaires for final analysis. Non-anonymous responses were from countries in all parts of the Region, including central Asia, the Caucasus, the Balkans, central, western and eastern Europe.

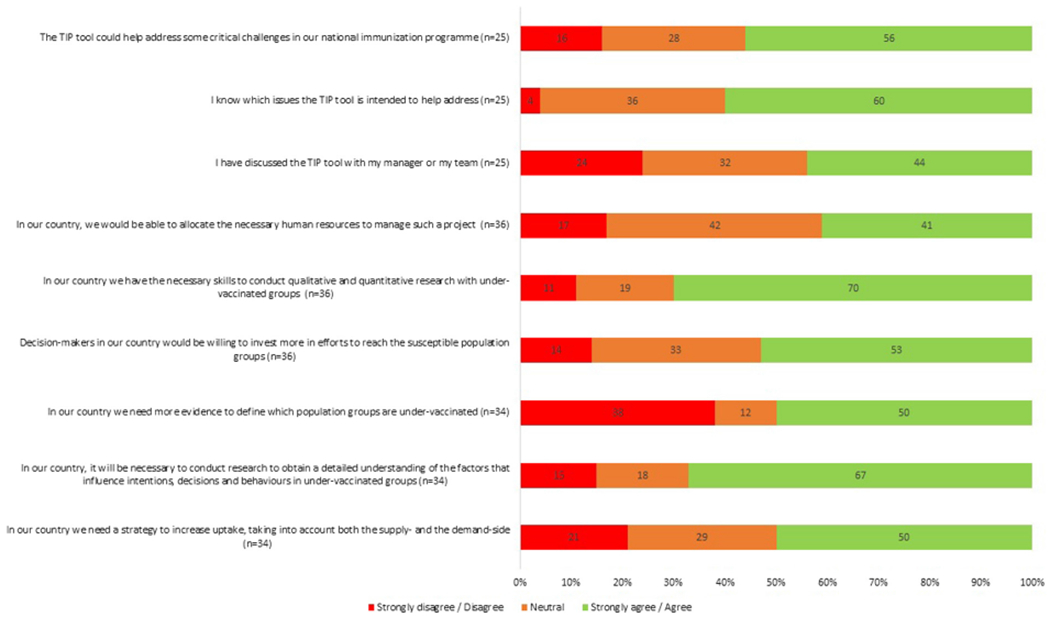

The majority of respondents (78%, 28/36) were aware of the ongoing work of the Regional Office to assist countries in analysing barriers and enablers to vaccination in unvaccinated population groups. The majority (69%, 25/36) had heard of the TIP tool before, most of them through WHO; nearly a third of respondents (31%, 11/36) skipped questions regarding awareness and understanding about TIP. Conservatively assuming that those who skipped this section did so because they lack awareness and understanding of TIP, the finding suggests that fewer than half of respondents knew what the TIP tool is intended to address (42%, 15/36 strongly agreed or agreed) and 14 considered that it could address critical challenges in their national immunization programme (39%, 14/36 strongly agreed or agreed); 11 (31%, 11/36) had discussed the TIP tool with their managers or teams (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Awareness, resources and requests for TIP projects in Member States (online survey).

Roughly half or fewer respondents reported having the necessary resources or backing to conduct research with undervaccinated groups and engage in efforts to reach these groups (Fig. 1).

Six respondents indicated that their countries had considered implementing a TIP project in the past but had not done so. The main reasons for this were lack of resources or expertise (n = 2), lack of communication or engagement among stakeholders (n = 3) and issues due to frequent changes in organization and management (n = 1).

Finally, 64% of respondents (23/36) indicated that their countries were planning to conduct research to better understand the factors that influence vaccination intentions, decisions and behaviours in undervaccinated groups, and 70% were also considering implementing a TIP project at some point in the future. However, only 8% (3/36) were planning a TIP project in the next year or two. Respondents noted that these future TIP projects planned to target: “migrant populations or refugees”, “vaccine opponents”, “particular vulnerable populations, health care specialists and adolescents”, “Roma population”, “undervaccinated groups of parents, media” and “highly educated parents with anti-vax opinions” (see Fig. 1).

Respondents were also asked in an open-ended question what else they would need to know about the TIP approach in order to consider it for use in their country. Of the 12 comments provided, three called for more information from other countries who have implemented a TIP project; five mentioned the need for more detailed guidelines, tools and training; two requested technical support from WHO; and one mentioned the need to raise awareness of TIP among stakeholders. In an additional comment, one respondent also asked WHO to establish a network of experts and immunization managers interested in this area of work.

4. Discussion and recommendations

An in-depth review of the application of the TIP approach conducted by an expert committee in 2016 arrived at several key findings and recommendations for the next generation of this particular approach. In summary, a web-based survey with participation from more than two thirds of the Member States in the Region suggested that the large majority recognize the problems of low vaccination uptake, and there is demand for and in some cases concrete plans for behavioural insights research and behaviour change interventions (see Fig. 1).

The review also found that TIP has several core components that have potential to add value to national immunization programmes. The process of TIP begins with identification of clearly defined population groups whose lack of full participation in immunization programmes represents a public health threat. The TIP approach is clearly suited to specific, tailored approaches to understanding reasons for under-vaccination that are complex and deeply embedded in cultural and local contextual factors.

Unlike many similar programme study or research projects, TIP is designed to be inclusive, participatory and sustained. Community engagement lies at the heart of the TIP approach and means including members of underserved population groups among active stakeholders who will define barriers to immunization and design solutions to overcome them. The review shows that qualitative research is a major strength, as it enhances listening and a rich understanding of individual and community perspectives. In other words, TIP research can be a means to two ends: building in-depth understanding on the side of health authorities, researchers and service providers; and building trust and helping to break barriers of misunderstanding on the side of community. Ideally, TIP involves an extended commitment to community engagement, taking it beyond identifying access barriers to designing and implementing changes that tailor existing services to unique community needs when routine approaches have failed.

The current TIP guide emphasizes its role as a diagnostic tool to understand the causes of under-vaccination among specific groups or segments in society. Implementing innovative strategies that emerge from diagnosis is implied as the logical next step. However, experience from the first round of TIP in countries shows that implementation – i.e. changing immunization systems and service delivery culture – is a long and difficult process. In fact, one country did not reach the intervention stage, and others have only taken the first steps in a longer process towards change. At this stage, only one country (Lithuania) had measured the actual impact in terms of increased coverage which obviously must be the end goal of any TIP project. There is a clear danger that overinvesting in the formative phase may come at the expense of implementing the ideas that emerge. A challenge across all countries visited was the time consuming nature of designing, collecting and analysing qualitative data which turned projects intended to last 6 months into years in some cases. Consequently, the expert committee recommends that new TIP projects should clearly emphasize intervention as the ultimate goal, and design methods to incentivize the move to piloting or scaling up ways to tailor services. “Intervention” can be any number of steps to act responsively to perceived barriers documented in the formative phase. A number of strategies were discussed to encourage this shift in emphasis.

Integrated focus on intervention. Beginning TIP processes with intervention as the goal will have a greater chance of reaching the final stage. The revised guidance documents could place greater emphasis on strategies to translate the diagnostics of the formative analysis into achievable interventions. They might make available ideas about what has been tried in the past (outlining the key principles of intervention, what other countries have tried and promising practices from other fields).

A shortened diagnostic exercise progressing to intervention development and optimisation through formative research: The initial diagnostic phase can be truncated by using rapid review methods, identifying the most obvious barriers affecting target communities and starting the intervention phase as quickly as community engagement allows. The review shows that the initial part of the formative phase – gathering available information and developing a situation analysis through broad stakeholder and community engagement – yields a strong foundation for designing initial interventions. Community engagement can be fostered through the process of implementation itself. Qualitative methods can also form part of the intervention optimisation phase and later the evaluation, where it can be refined and deeper insights into remaining barriers gathered.

Seed funding should be made available to countries for the intervention and evaluation phases. WHO should set aside resources for developing, implementing and evaluating an intervention, conditional on timely completion of the diagnostic phase of the study.

Emphasis should be placed on monitoring and evaluating outcomes and impact. The ultimate success of TIP must be removing barriers that reduced demand for vaccination services and an increase in vaccination uptake. In addition to this, a mix of indicators should be developed and monitored to demonstrate both the direct and indirect gains of the work conducted, including indicators related to equity and other measures as outlined by respondents in Table 2.

The review visits have also shown that WHO engagement and expert support has been highly valued and sometimes essential for a TIP project to take place. WHO participation in data collection in all countries was not considered to strongly bias this perception by national stakeholders, as participants also frankly noted that in some cases strong WHO support led to reduced national ownership and local coordination. Hence, WHO should continue to support TIP processes in countries through technical support in initiation, skilled facilitation of the TIP process and TIP documents and tools, while also ensuring local ownership and investment. WHO should develop and share an “exit strategy” for every country, and return to each country to assess progress and determine what might be useful to support implementation of interventions.

In conclusion, the idea of strong community engagement and targeted tailoring of services proposed by TIP remains as compelling as ever, as evidenced by the growing number of requests for TIP support from national immunization managers in the Region. However, it is important to emphasize that the purpose of TIP is not simply to diagnose enablers and barriers to immunization uptake but to take the next step to intervene appropriately, evaluate and improve over time to finally close remaining immunization gaps in the population.

As next steps, the expert committee has advised WHO to incorporate conclusions and recommendations as a revised version of the TIP guidance document. This should place more emphasis on using the behavioural insights gained in the process to implement and evaluate interventions to increase vaccination coverage. WHO will continue to support Member States in applying the TIP approach. A continuous process of adjustment and improvement based on cumulative evidence will be needed to realize the full potential and optimal conditions for the application of this approach.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Angel Kunchev, Radosveta Filipova, Meilė Minkauskienė, Giedre Gefenaite-Bakker, Pernille Jorgensen, Ann Lindstrand, Karina Godoy, Asha Jama, Emma Byström, Asli Kulane, Vanessa Rew, Louise Letley, Rehana Ahmed, Lisa Menning, Robb Butler, Nathalie Likhite, as well as national health professionals, researchers, immunization programme managers and other staff for their participation in the evaluation. The authors would like to thank Ms. Manale Ouakki for her assistance in the analysis of the survey data. This work was supported by the WHO Regional Office for Europe.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

Katrine Habersaat is a staff member of the World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe and is responsible for overseeing the development of TIP methodology. She was responsible for organizing the review which led to this publication. Eve Dube, Julie Leask and Everold Hosein received remuneration from the World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe to undertake the review. The remaining authors are staff members of organizations which covered the costs of their participation (Brent Wolff and Victor Balaban – Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Benjamin Hickler – United Nations Children’s Fund Programme Division). The authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this article and they do not necessarily represent the views, decisions or policies of the institutions with which are affiliated.

References

- [1].WHO Regional Office for Europe. Fifth Meeting of the European Regional Verification Commission for Measles and Rubella Elimination (RVC). <http://www.euro.who.int/_data/assets/pdf_file/0005/330917/5th-RVC-meeting-report.pdf?ua=1> 2017. [accessed 08.05.17].

- [2].WHO EpiData. <http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/disease-prevention/vaccines-and-immunization/publications/surveillance-and-data/who-epidata> [accessed 08.05.17].

- [3].WHO Regional Office for Europe. European Vaccine Action Plan 2015–2020 (EVAP). Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe. <http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/disease-prevention/vaccines-and-immunization/publications/2014/european-vaccine-action-plan-20152020-2014> 2014. [accessed 08.05.17]. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Guidance document launched in 2013: WHO Regional Office for Europe. Guide to tailoring immunization programmes (TIP). <http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/communicable-diseases/poliomyelitis/publications/2013/guide-to-tailoring-immunization-programmes> 2013. [accessed 24.01.17].

- [5].Report of the SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy. <http://www.who.int/immunization/sage/meetings/2014/october/1_Report_WORKING_GROUP_vaccine_hesitancy_final.pdf> 2014. [accessed 08.05.17].

- [6].Byström E, Lindstrand A, Likhite N, Butler R, Emmelin M. Parental attitudes and decision-making regarding MMR vaccination in an anthroposophic community in Sweden – a qualitative study. Vaccine 2014;32:6752–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].WHO Regional Office for Europe. Review of the WHO Regional Office for Europe Tailoring Immunization Programmes (TIP) behavioural insights tool and approach Final report. <http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/disease-prevention/vaccines-and-immunization/activities/tailoring-immunization-programmes-to-reach-underserved-groups-the-tip-approach/evaluation-of-the-tip-tool-and-approach-in-the-european-region> [accessed 08.05.17].

- [8].WHO Regional Office for Europe. TIP FLU and TAP (tailoring antimicrobial resistance programmes). <http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/communicable-diseases/poliomyelitis/activities/tailoring-immunization-programmes-to-reach-underserved-groups-the-tip-approach/tip-flu-and-tap-tailoring-antimicrobial-resistance-programmes> 2017. [accessed 08.05.17].