Abstract

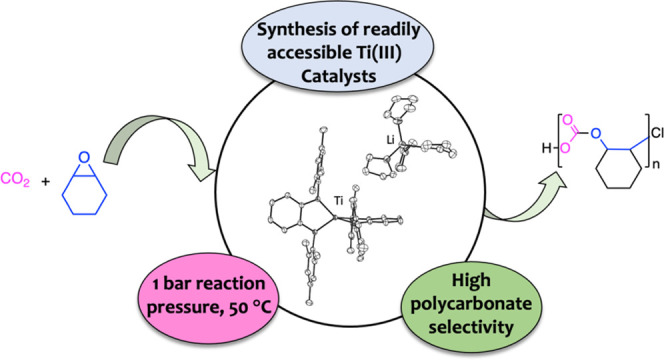

Titanium compounds in low oxidation states are highly reducing species and hence powerful tools for the functionalization of small molecules. However, their potential has not yet been fully realized because harnessing these highly reactive complexes for productive reactivity is generally challenging. Advancing this field, herein we provide a detailed route for the formation of titanium(III) orthophenylendiamido (PDA) species using [LiBHEt3] as a reducing agent. Initially, the corresponding lithium PDA compounds [Li2(ArPDA)(thf)3] (Ar = 2,4,6-trimethylphenyl (MesPDA), 2,6-diisopropylphenyl (iPrPDA)) are combined with [TiCl4(thf)2] to form the heterobimetallic complexes [{TiCl(ArPDA)}(μ-ArPDA){Li(thf)n}] (n = 1, Ar = iPr 3 and n = 2, Ar = Mes 4). Compound 4 evolves to species [Ti(MesPDA)2] (6) via thermal treatment. In contrast, the transformation of 3 into [Ti(iPrPDA)2] (5) only occurs in the presence of [LiNMe2], through a lithium-assisted process, as revealed by density functional theory (DFT). Finally, the Ti(IV) compounds 3–6 react with [LiBHEt3] to give rise to the Ti(III) species [Li(thf)4][Ti(ArPDA)2] (Ar = iPr 8, Mes 9). These low-valent compounds in combination with [PPN]Cl (PPN = bis(triphenylphosphine)iminium) are proved to be highly selective catalysts for the copolymerization of CO2 and cyclohexene epoxide. Reactions occur at 1 bar pressure with activity/selectivity levels similar to Salen–Cr(III) compounds.

Short abstract

We describe the synthesis of Ti(III) bis(o-phenylendiamido) species, including mechanistic insights gathered by a combination of X-ray studies, NMR spectroscopy, and DFT calculations. In addition, we disclose the application of the titanium(III) compounds as effective catalysts for the selective copolymerization of CO2 and cyclohexene epoxide under atmospheric reaction conditions (1 bar).

Introduction

Low-valent titanium compounds are receiving significant attention due to their versatile applications in organic synthesis, catalysis, and small-molecule activation.1,2 However, the chemistry of these reagents is underdeveloped in comparison to mid and late-transition metals, which can be attributed to their strongly reducing character. Therefore, these complexes require powerful stabilizing fragments, typically bulky cyclopentadienyl ligands.3 Nevertheless, the use of other supporting fragments has led to new species otherwise not accessible. For instance, Ti(0) and Ti(I) systems are isolated in the form of bisarene species.3 In addition, the installation of ligands containing amido fragments such as PNP ([N(2-iPr-4-MeC6H3)2]), amidinate, guanidinate, and β-diketiminate compounds4 has enabled access to applications in the field of catalytic dehydrogenation5 and hydrogenation6 reactions, and more remarkably into the more challenging area of nitrogen fixation.7 Comparatively, the use of chelate diamido fragments as ancillary ligands for titanium compounds in low oxidation states has been less explored.

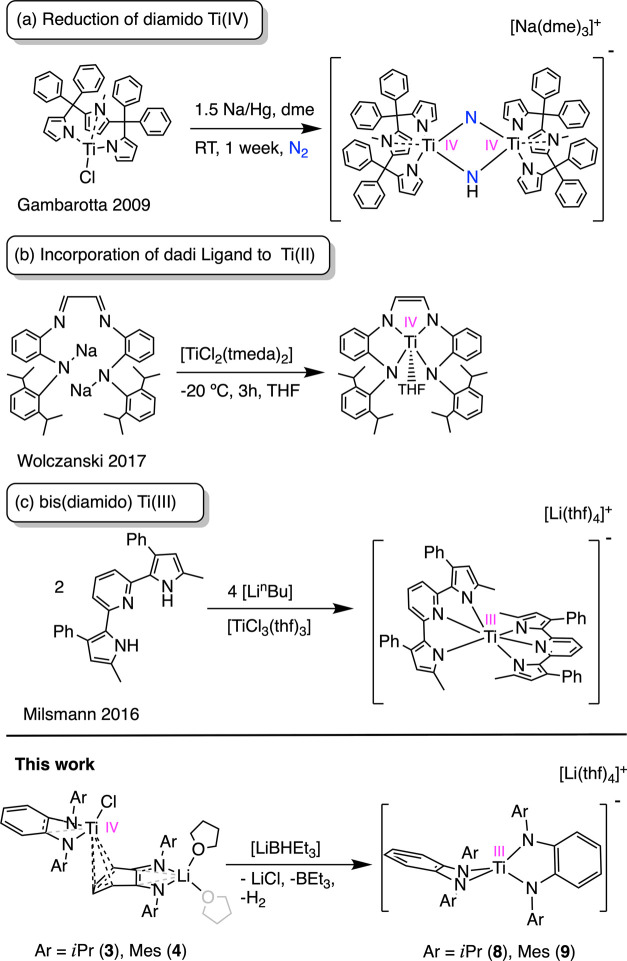

Using a tripyrrole dianion, Gambarotta8 described the chemical reduction of the corresponding titanium chloride complex with Na/Hg in the N2 atmosphere (Figure 1a). Although the reduced species was not isolated, the low valency was evidenced by the splitting and partial hydrogenation of dinitrogen. Later, Wolczanski9 explored the incorporation of the diamido fragment present in the ligand diamido-diimine dadi (dadi = {−CH=N(1,2-C6H4)N(2,6-iPr2-C6H3)}2) to the titanium(II) precursor [TiCl2(tmeda)2] (Figure 1b). Instead of forming the corresponding Ti(II) species, the reaction resulted in the chemical reduction of the diimine fragment and generation of the bis(diamido) Ti(IV) compound [Ti(dadi)(thf)].9 For the oxidation state III, Milsmann10 reported the isolation of a bimetallic Li/Ti(III) compound upon the reaction of lithium 2,6-bis(pyrrolyl)pyridine with the already reduced [TiCl3(thf)3], but no further reactivity was studied (Figure 1c).

Figure 1.

Previous and new work on the preparation of low-valent titanium diamido compounds. (a) Reduction of a tripyrrole Ti(IV) species. (b) Incorporation of the diamido-diimine, dadi, ligand to a Ti(II) precursor. (c) Installation of a 2,6-bis(pyrrolyl)pyridine ligand to the Ti(III) precursor [TiCl3(thf)3].

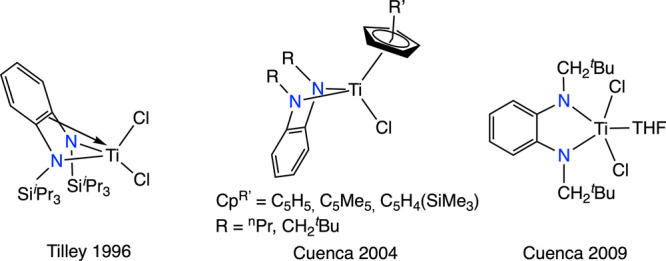

Among the diamido ligands, ortho-phenylenediamido species (PDA) have been demonstrated to be excellent supporting ligands for strongly reducing species such as Mg(I),11 Zn(I), and Ga(II).12 In contrast, within the chemistry of titanium, these ligands have been only employed in the preparation of Ti(IV) compounds, where the most used fragments are the N,N′-disilyl,13N,N′-bis(neopentyl),14 and N,N′-bis(n-propyl)14c,14d substituted (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Prior examples of PDA-Ti(IV) compounds.

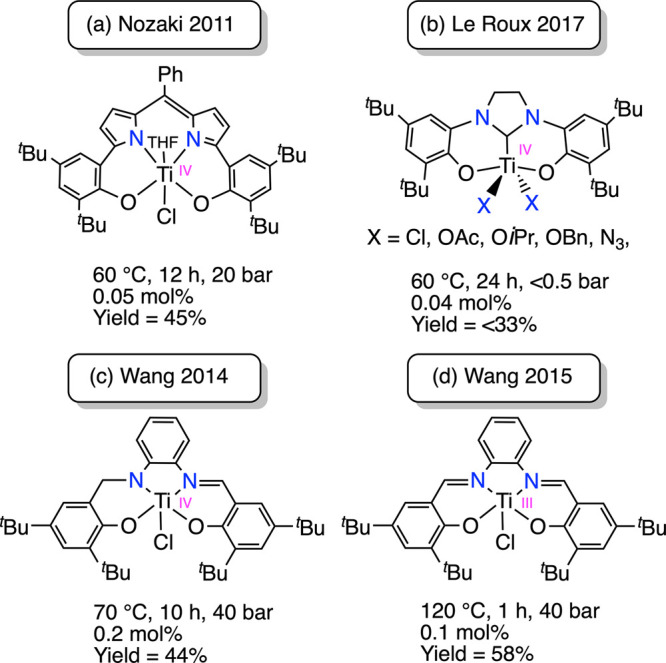

Titanium-based compounds are particularly attractive catalysts for CO2 functionalization through ring-opening copolymerization (ROCOP) with epoxides due to their high abundance, low cost, and limited toxicity.15−17 However, the application of these metal complexes has received limited attention compared with species based on Zn(II), Co(II/III), Cr(III), and Al(III).18 Despite the recent emergence of Ti(III) species as an efficient catalyst,19 this field remains dominated by titanium catalysts in the highest oxidation state.20 Revealing the potential of titanium(IV) compounds in this field, Nozaki21 reported the [(Boxdipy)TiCl] (Boxdipy = 1,9-bis(2-oxidophenyl)dipyrrinate) (Figure 3a) complex, which in conjunction with [PPN]Cl produces a completely alternating polycyclohexenecarbonate in a 45% yield. The copolymerization reaction involves cyclohexene oxide (CHO), CO2 (20 bar), and 0.05 mol % of catalyst and is carried out at 60 °C for 12 h. More recently, Le Roux22 described a series of bis-aryloxy N-heterocyclic carbene (NHC) titanium compounds (Figure 3b). These species, at 0.04 mol % catalyst loading, combined with [PPN]Cl mediate copolymerization of CHO with CO2 at 60 °C and lower reaction pressure (<0.5 bar). Despite this improvement, the catalytic reaction requires longer reaction times (24 h) and results in low yields (<33%). Using Salen ligands, Wang23 developed a [(Salen)Ti(IV)Cl2] species that, despite being unable to mediate copolymerization of CHO/CO2, selectively generates cyclic carbonate. When the asymmetric Salalen ligand was employed, the catalytic system formed by [(Salalen)TiCl] (Figure 3c) (0.2 mol %) and [PPN]Cl mediates copolymerization of CHO/CO2 in a 44% yield, at 70 °C, 40 bar and for 10 h.23 Remarkably, the same Wang19 reported a more active catalytic system based on Ti(III). The [(Salen)Ti(III)Cl] (Figure 3d) complex in 0.1 mol %, along with [PPN]X (X = Cl, Br, 2,4-dinitrophenolate) salts as cocatalyst, catalyzes the formation of polycyclohexenecarbonate with a 58% yield, requiring 1 h at 120 °C and 40 bar. Notably, this low-valent titanium system mimics the remarkably active and selective Salen–chromium [(Salen)Cr(III)N3]/[PPN]Cl binary system, which generates polycyclohexenecarbonate in 85% yield, using 0.04 mol % at 80 °C, 55 bar in 4 h.24 The greater catalytic activity of the Ti(III) compound compared with the Ti(IV) compound is rationalized based on the stronger polarity of the Ti(III)–O bond, which favors the reversible formation and dissociation of the Ti–O bonds necessary for the propagation step.19 Despite this advance, it is surprising that, to the best of our knowledge, there have not been further reports using a Ti(III) catalyst for the copolymerization of CO2 and epoxides. Only Le Roux22 attempted to prepare an NHC-based Ti(III) compound as a potential precursor for the copolymerization reaction, albeit the employed ligands proved to be resistant to accommodate the Ti(III).

Figure 3.

Titanium-based compounds reported for the copolymerization of CO2 and CHO.

Bearing in mind the capability of PDA ligands to stabilize low-valent metallic compounds, and the potential of Ti(III) species in the functionalization of CO2, herein we describe the synthesis and reduction of bis-PDA Ti(IV) species. The isolated bis(diamido) Ti(III) compounds are characterized by X-ray data and EPR spectroscopy. In addition, DFT calculations were performed in order to fully understand the bonding situation, electronic structure, and the thermodynamics controlling the formation of some of the Ti(IV) precursors of the Ti(III) compounds. The catalytic potential of the Ti(III) species is probed for the copolymerization of CO2 and cyclohexene epoxide, generating selective polycarbonate under mild reaction conditions (pCO2 = 1 bar, 50 °C). Remarkably, compound [Li(thf)4][Ti(MesPDA)2] 9 displays activity and selectivity levels comparable to Salen–chromium catalysts.

Results and Discussion

Synthesis of Ti Compounds

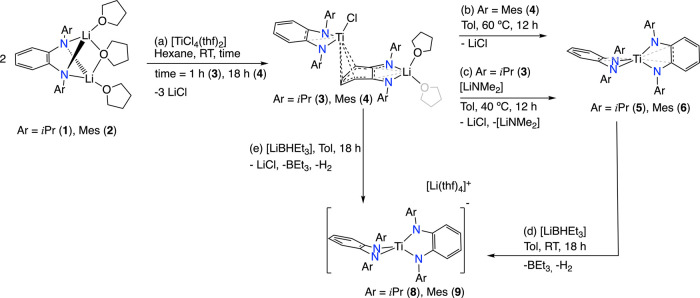

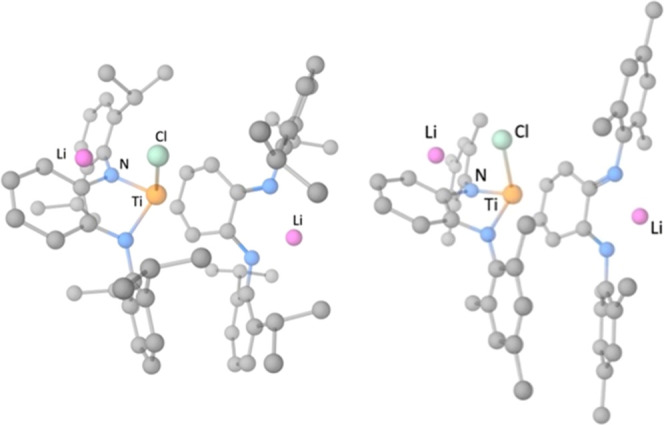

We began our studies by looking into the incorporation of two equivalents of the mesityl (MesPDA)- and 2,6-diisopropylphenyl (iPrPDA)-substituted PDA2– fragments into Ti(III) through transmetalation reaction between the corresponding lithiated precursors 1 and 2 and [TiCl3(thf)3] in C6H6. Unexpectedly, analysis of the reaction mixture by 1H NMR spectroscopy in C6D6 revealed the generation of diamagnetic products, which are assigned to compounds 5 and 6 (Figures S14 and S15). A disproportionation reaction is more likely to be responsible for the formation of the Ti(IV) complexes (5 and 6). Alternatively, we sought the synthesis of the titanium(IV) precursors and subsequent reduction. Initially, we reacted two equivalents of the ligands ArPDAH2 (Ar = Mes, iPr) with [Ti(CH2Ph)4] in C6D6 at temperatures ranging from room temperature to 110 °C. This method was unsuccessful, resulting in no reaction in the case of the bulkier iPrPDAH2, while for the MesPDAH2 ligand only small amounts of a compound identified as 6 were formed. Consequently, we explored a second route that involves a transmetalation reaction using the lithium derivatives 1 and 2 and the [TiCl4(thf)2] starting material (Scheme 1a). The highest yields were achieved using hexane as a solvent. However, the distinct solubility of the final products 3 (soluble) and 4 (insoluble) in this apolar solvent leads to different reaction times, requiring 1 h for 3 and 18 h for 4. 1H NMR spectra of the resulting compounds 3 and 4 in C6D6 reveal the existence of two chemically distinct PDA fragments, in which one of the ligands displays two resonances for the phenylene fragment at high field (range 5.30–6.41 ppm), indicative of a π-coordination to a metallic center. In addition, an inspection of the reaction mixtures by 7Li NMR spectroscopy shows signals at 2.09 and 2.22 ppm for 3 and 4, respectively. X-ray analysis of single crystals of these compounds reveals partial transmetalation, forming a heterobimetallic compound consisting of a [Li(ArPDA)(thf)n] (n = 1, Ar = iPr; n = 2, Ar = Mes) fragment, which binds through the phenylene backbone in a η4-C6H4 fashion to a [TiCl(ArPDA)] moiety (Figure 4).

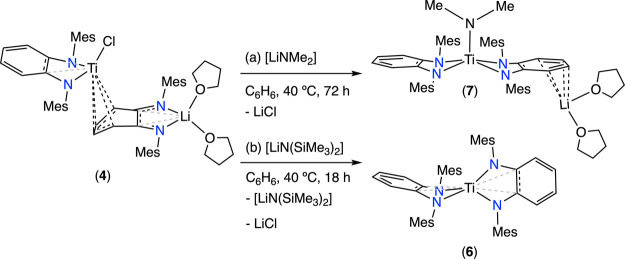

Scheme 1. Synthesis of PDA-Titanium Compounds.

(a) 3 and 4, (b) 6, (c) 5, and (d, e) 8 and 9.

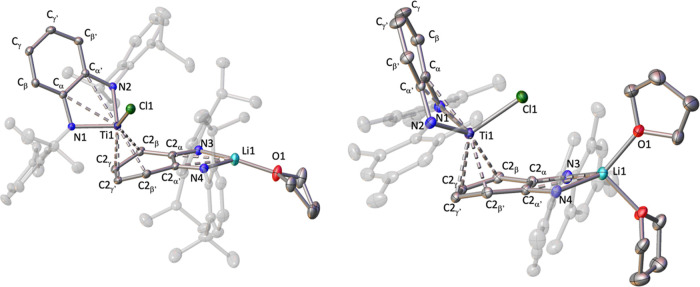

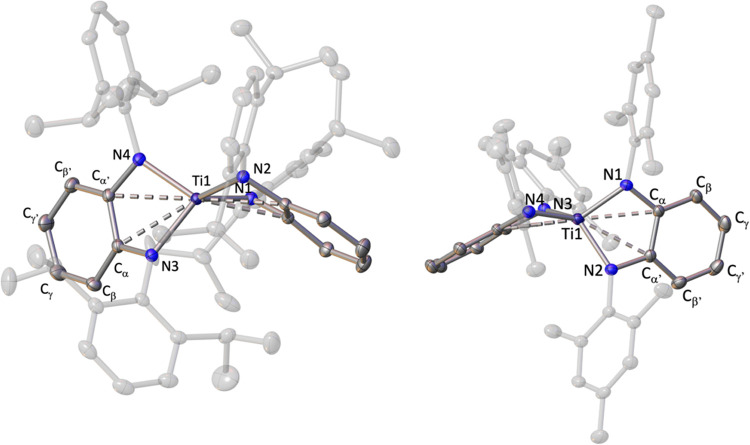

Figure 4.

Solid-state structure of compounds 3 (left) and 4 (right) with thermal ellipsoids at 30% of probability. Hydrogens are omitted for clarity. The torsion angle for cent1–cent2–Ti1–Cl1 is 58.98(1)° for 3 and 1.61(3)° for 4, where cent1 = centroid of diazametallacycle LiN2C2 and cent2 = centroid of the C2α-C2α′ ring. The dihedral angle between planes formed by C2β–C2α–C2α′–C2β′ and C2β–C2γ–C2γ′–C2β′ is 21.1(1)° for 3 and 14.4(3)° for 4.

Structurally, compounds 3 and 4 are similar, although they exhibit different relative dispositions of both fragments reflected by the significantly distinct torsion angle for cent1–cent2–Ti1–Cl1 (see torsion angles in Figure 4). This difference is most likely due to the bulkier nature of the iPrPDA ligands in compound 3 that impedes a close approximation of both PDA fragments as observed in 4 (see van der Waals model representation in Figure S16). In addition, this situation leads to much longer distances between the chlorine and lithium atoms of the vicinal fragments in compound 3 (5.785(3) Å) than the one registered in complex 4 (3.909(6) Å).

Further analysis of the titanium-PDA fragment discloses that the metal in compounds 3 and 4 coordinates with the two nitrogen atoms of the attached ligand, the chlorine atom, and the η4-C6H4 fragment. The latter coordination is confirmed by the puckering of the phenylene ring (see dihedral angles in Figure 4) and the short Ti–C bond distances ranging from 2.281(2) to 2.463(2) Å. Additionally, in both cases, titanium displays an interaction with the electron π density on the Cα=Cα′ fragment of the PDA ligand,13,25 consistent with the elongation of the latter bond (1.425(2) Å in 3; 1.427(5) Å in 4) and the Ti–C bond distances exhibiting an average value of 2.644(3) Å for 3 and 2.548(5) Å in 4.

Doubly deprotonated PDA species can exist as ortho-diamido, ortho-diiminosemiquinonate, and ortho-benzo-quinodiimine fragments through one- and two-electron oxidation processes.26 For the PDA ligand coordinating the titanium atom through the nitrogen atoms (henceforth PDA-N) both X-ray and optimized DFT geometries (at B3LYP-D3BJ(SMD)/def2SVP level of theory) show a notable degree of bond length equalization for the C–C bonds (average 1.39(1) Å), and characteristic single C–N bond lengths (Table 1), pointing to a diamido nature for this fragment.27 Further support for this diamido character is found in the Ti–N bonds of 3 (average = 1.95(1) Å) and 4 (average 1.928(3) Å), which lie in the range for reported Ti(IV) compounds supported by diamido ligands.13,14c,25a,25c,28

Table 1. X-Ray and Optimized DFT (B3LYP-D3BJ/Def2SVP Level of Theory) Bond Lengths (in Å), and Bond Orders for the Phenyl Ring of PDA-N in Compounds 3 and 4.

| Compound 3 |

Compound 4 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bond length | Bond length | |||||

| Bond | X-ray | DFT | Bond order | X-ray | DFT | Bond order |

| Cα–Na | 1.404(7) | 1.397 | 1.05 | 1.406(1) | 1.398 | 1.08 |

| Cα–Cα′ | 1.425(2) | 1.432 | 1.13 | 1.427(5) | 1.432 | 1.14 |

| Cα–Cβa | 1.399(1) | 1.407 | 1.25 | 1.403(1) | 1.406 | 1.26 |

| Cβ–Cγa | 1.380(2) | 1.392 | 1.40 | 1.373(1) | 1.392 | 1.40 |

| Cγ–Cγ′ | 1.384(3) | 1.404 | 1.34 | 1.388(6) | 1.404 | 1.35 |

Bond distance average.

Contrary to PDA-N, the PDA ligand bound to lithium and coordinating titanium through the phenylene ring (henceforth PDA-Ring) displays experimental and DFT-calculated shorter average C–N bonds, as well as the loss of the bond length equalization of the phenyl ring (Table 2). Additionally, and in agreement with the puckering of the rings, the phenyl moieties have lost their planarity.

Table 2. X-Ray and Optimized DFT (B3LYP-D3BJ/Def2SVP Level of Theory) Bond Lengths (in Å), and Bond Orders for the Phenyl Ring of PDA-Ring in Compounds 3 and 4.

| Compound 3 |

Compound 4 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bond distance | Bond distance | |||||

| Bond | X-ray | DFT | Bond order | X-ray | DFT | Bond order |

| C2α–N | 1.313(3) | 1.320 | 1.24 | 1.315(3) | 1.326 | 1.28 |

| C2α–C2α′ | 1.479(2) | 1.489 | 0.95 | 1.488(4) | 1.487 | 0.98 |

| C2α–C2βa | 1.431(1) | 1.431 | 1.17 | 1.432(1) | 1.429 | 1.19 |

| C2β–C2γa | 1.415(2) | 1.419 | 1.25 | 1.416(2) | 1.418 | 1.26 |

| C2γ–C2γ′ | 1.385(3) | 1.399 | 1.32 | 1.389(5) | 1.399 | 1.33 |

Bond distance average.

A structurally similar heterobimetallic Li/Ta PDA-based complex has been described by Song.29 According to the metrical data, the author proposes a diiminocyclohex-2-ene-1,4-diide as the predominant resonant form for the PDA ligand. Based on the electropositive nature of the tantalum atom, they describe the interaction between the [TaClMe3] moiety and the phenylene ring of the [Li(OEt2)(iPrPDA)(thf)] fragment as a metallacyclopentene. In our case, the shorter C2γ–C2γ′ bonds (1.385(3) Å for 3 and 1.389(5) Å for 4) than those for C2β–C2γ (average 1.415(2) Å for 3; 1.416(2) Å for 4) favor a metallacyclopentene interpretation, whereas the significantly longer Ti–Cβ bonds (average 2.44(2) Å for 3; 2.435(1) Å for 4) than the Ti–Cγ distances (average 2.29(1) Å for 3; 2.302 (7) Å for 4) are contrary to this interpretation. Aiming to clarify the bonding situation, we analyzed the electronic structure of 3 and 4 by means of DFT calculations using two parameters: oxidation states (OS) and bond orders (B3LYP-D3BJ/def2TZVP//B3LYP-D3BJ(SMD)/def2SVP level of theory).

First, the OS of Ti and the formal charge of ligands for 3 and 4 were assigned using the effective oxidation state (EOS) approach.30−32 The OS of titanium and both diamido (PDA) units are, respectively, +4 and −2. Considering the occupation numbers of the last occupied spin-resolved effective fragment orbital (EFO) and the first unoccupied EFO (see Tables S1 and S2), this OS assignation in 3 and 4 is indisputable. These results suggest that no redox reactions have taken place, and hence the diiminosemiquinonate and benzo-quinodiimine forms are unlikely to define the PDA-Ring unit.

The Ti–C bond orders in the Ti–arene interaction for compounds 3 and 4 reveal very similar values between Ti and the four carbons Cβ, Cγ, Cβ′, and Cγ′ (Table 3). Regarding the PDA-Ring fragment, the C–N bond orders lie between single and double bond characters, and compared with PDA-N, the Cα–Cβ and Cβ–Cγ bond orders reveal a decrease.

Table 3. Bond Lengths (in Å) and Bond Order for Each Ti–C Bond of the Phenyl Ring of PDA-Ring in Compounds 3 and 4.

| Compound 3 |

Compound 4 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bond distance | Bond distance | |||||

| Atom | X-ray | DFT | Bond order | X-ray | DFT | Bond order |

| Cαa | 3.00(2) | 2.88 | 0.077 | 2.883(6) | 2.84 | 0.085 |

| Cβ | 2.416(2) | 2.41 | 0.263 | 2.437(3) | 2.43 | 0.251 |

| Cγ | 2.281(2) | 2.31 | 0.263 | 2.308(3) | 2.32 | 0.256 |

| Cγ′ | 2.307(2) | 2.32 | 0.257 | 2.295(3) | 2.32 | 0.255 |

| Cβ′ | 2.463(2) | 2.48 | 0.241 | 2.434(3) | 2.44 | 0.241 |

Bond distance average.

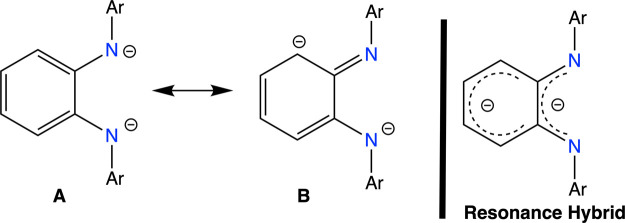

Overall these data suggest that the coordination of the PDA-Ring to Ti(IV) is better described by a Ti-η4-arene, where the phenylene ring is acting as an anionic π-electron-donating ligand according to the resonance form B and its resonance hybrid shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Resonance forms and resonance hybrid for the PDA2– ligand.

Supporting this bonding mode, the registered Ti–C bond distances for compounds 3 and 4 (Table 2) are reminiscent of previously reported Ti–arene compounds, in which Ti-(η4-arene) coordination is observed.33 For example, the structurally characterized titanium-anthracene33a complexes [Ti(η6-C14H10)(η4-C14H10)(η2-dmpe)], [Ti(η4-C14H10)(η2-C14H10)(η5-C5Me5)]− (Ti–C range = 2.295(3)–2.424(4) Å), and Ti-naphtalene [Ti(η4-C10H8)2(SnMe3)2]2– (Ti–C range = 2.30(1)–2.34(1) Å).33b Additionally, these reports also describe longer distances for the Cβ–Cγ (range 1.427(6)–1.44(2) Å) compared with the Cγ–Cγ′ (1.375(6)–1.38(2) Å) for the aromatic ring bonded to the titanium atom.33

Next, we studied the potential transformation of species 3 and 4 toward the desired titanium(IV) bis(diamido) precursors. In agreement with the shorter Li···Cl distance found for compound 4 compared with 3, the former facilitates LiCl release upon heating at 60 °C, generating compound 6 (Scheme 1b). In contrast, intermediate 3 proves to be thermally robust, as no evolution is detected upon thermal treatment. The observed differences in reactivity for compounds 3 and 4 can be related to the exergonicity of the reactions computed with DFT (see Table S3). Thus, the formation of 6 from 4 is exergonic (ΔG0 = −2.1 kcal/mol, see Figure S1 and Table S3), whereas the equivalent reaction to give rise to 5 from 3, with the bulkier iPr ligand, is strongly endergonic (ΔG0 = + 12.8 kcal/mol, see Figure S3 and Table S3). Therefore, while the formation of 6 is thermodynamically favorable, the generation of 5 is not favorable, explaining why 3 does not evolve to the desired bis(amido) titanium species 5 by heating. Remarkably, if the thermodynamics of the transformations of 3 (4) to 5 (6) are simulated including a second lithium cation in the reactant complex (3 or 4), a noteworthy observation emerges. Through the interaction of lithium with the nitrogen atoms of PDA-N and the chloride (Figure 6), the complete transmetalation is strongly exergonic for 4 (ΔG0 = −17.2 kcal/mol, see Figure S2 and Table S3) and is isoergonic for 3 (ΔG0 = + 0.7 kcal/mol, see Figure S4 and Table S3). Thus, the inclusion of a second Li+ in the reactant complex strongly contributes to decreasing the reaction Gibbs energy for the formation of the bis(amido) titanium species 5 and 6. In agreement with these DFT results, the reaction of a toluene solution of species 3 with 1 equiv of the lithium amide [Li(NMe2)] at 40 °C leads to the isolation of compound 5 in a 67% yield along with the recovering of the employed lithium amide (Scheme 1c).

Figure 6.

Geometries for the reactant complex including a second lithium cation, for compounds 3 (left) and 4 (right). The hydrogen atoms are hidden for clarity.

The solid-state structures of compounds 5 and 6 (Figure 7) show the titanium atoms coordinating the two ArPDA ligands in a σ2, π fashion via four Ti–N bonds (average values: 1.94(3) Å for 5 and 1.92(3) Å for 6) and by interaction with the Cα=Cα′ fragment, according to the lengthening of this bond (1.420(1) Å for 5 and 1.436(1) Å for 6) and the average distances between titanium and the carbon atoms (2.54(1) Å in 5 and 2.57(1) Å in 6). These geometrical parameters resemble those registered for the titanium-PDA-N fragment in compounds 3 and 4, and the homoleptic bis(diamido) titanium compounds bearing the N,N′-bis(2,6-diisopropylphenyl)-1,4-diazabutadiene25a and the 1,2-bis[(2,6-diisopropylphenyl)imino]acenaphthene ligands displaying a similar σ2, π coordination.34

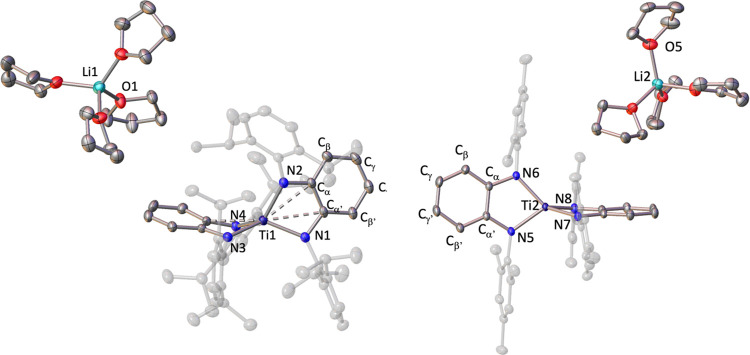

Figure 7.

Solid-state structure of compounds 5 (left) and 6 (right) with thermal ellipsoids at 30% of probability. Hydrogens are omitted for clarity.

Consistent with the diamido nature of the PDA ligands, the average C–N bond lengths are 1.4054(9) Å for 5 and 1.411(2) Å for 6. Moreover, the phenylene ring retains the aromaticity, displaying C–C average distances of 1.38(1) Å for 5 and 1.387(9) Å for 6, excluding the longer Cα=Cα′ bonds. To relieve the steric congestion created by the two ArPDA ligands, they are arranged in a staggered disposition displaying a dihedral angle between the planes formed by the PDA units of 61.94(5)° for 5 and 69.04(9)° for 6. In addition, the wingtip aryl substituents adopt a nearly orthogonal disposition relative to the central phenylene fragments with dihedral angles ranging from 67.84(8) to 74.11(8)° for compound 5 and from 73.4(1) to 80.7(1)° for compound 6. This situation is reflected in the 1H NMR spectrum of 5 in C6D6, which shows four sets of signals for the isopropyl and phenylene groups. In contrast, compound 6 displays in its 1H NMR spectrum in C6D6 one set of broad signals for the methyl substituents, which can be attributed to a rapid rotation around the N–C(Ar) bonds on the NMR timescale. In agreement with the latter, the 1H NMR of compound 6 in C7D8 at 233K shows the inequivalence of the methyl groups (Figure S37).

Contrasting with the exclusive transformation of 3 into 5 in the presence of [LiNMe2], when we reinvestigated the synthesis of 6 by heating a toluene solution of 4 assisted by [LiNMe2], a mixture of compound 6 and a new species was observed. Longer reaction times (Scheme 2a) resulted in the consumption of 6 in favor of the new product, which incorporates an anionic [NMe2]– fragment, according to the signal observed at 3.19 ppm by 1H NMR spectrum.

Scheme 2. Synthesis of Compound 7.

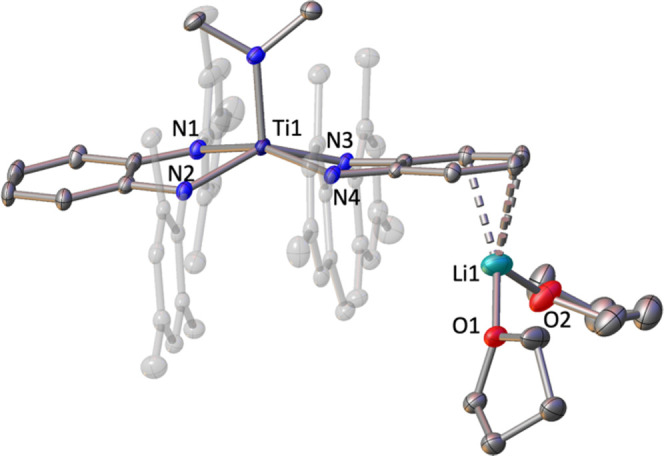

X-ray analysis of single crystals grown by slow evaporation in benzene reveals the formation of the contacted ion-paired species [Li(thf)4][Ti(MesPDA)2(NMe2)] (7) (Figure 8), in which the cationic fragment [Li(thf)2] is bounded through a phenylene unit of one PDA ligand.

Figure 8.

Solid-state structure of compound 7 with thermal ellipsoids at 30% of probability. Hydrogens are omitted for clarity.

The solid-state structure reveals how the PDA units around the titanium atom are capable to transition from the original pseudo-tetrahedral geometry, found in the bis(diamido) compound 6, to a relative pseudo-planar disposition (dihedral angle between the PDA planes is 12.18(8)°). This rearrangement of the PDA fragments results in elongated Ti–N bonds (Δdaverage Ti–N = 0.15 Å compared with 6) and Ti···Cα,α′ distances (Δdaverage Ti···C = 0.34 Å compared with 6) to accommodate a fifth amido group. The molecular structure resembles those reported by Wolzcanski for a series of ionic compounds supported by the bis(diamido) dadi4– ligand with a general formula [Li(thf)2.5–4][Ti(dadi)X] (X = Me, OiPr, H).9 In our case, the PDA ligands display average C–N and C–C bond distances of 1.39(1) and 1.39(1) Å, respectively, in agreement with the diamide form. The titanium atom is shifted out of the N4 plane by 0.474(1) Å and forms the shortest Ti–N bond (1.909(3) Å) with the NMe2 unit.

Repeating the reaction between compound 4 and the bulkier reagent [LiN(SiMe3)2] only leads to the formation of the final product 6 (Scheme 2b). This result along with the lack of incorporation of an anionic [NMe2]− into the sterically congested species 5 suggests that the formation of ionic compounds similar to 7 is ruled by the balance of steric properties between the lateral substituents of the PDA ligands and the incoming anionic fragment.

Reduction of the Titanium(IV) Compounds

The observed flexibility of the PDA ligands to accommodate an additional and relatively small fragment of titanium encouraged us to explore the formation of a possible titanium hydride species as a potential pathway for the chemical reduction of titanium via hydrogen release, similar to previous reports.35 Accordingly, the reaction of 3 and 4 or 5 and 6 with [LiBHEt3] generates in a straight manner the heterobimetallic Li/Ti(III) species 8 and 9 (Scheme 1d,e). It is reasonable to argue that starting from compounds 3 and 4, they are first transformed into 5 and 6 assisted by the presence of the second lithium reagent. Subsequently, the reduction of Ti(IV) proceeds via initial hydride transfer from boron to titanium releasing BEt3 (detected by 1H NMR). This process leads to the formation of an ionic titanium hydride species “[Li(thf)4][TiH(ArPDA)2]”, akin to the isolated species 7. In the last step, the putative titanium hydride compound evolves toward the Ti(III) species and produces molecular H2. The H2 equivalents produced during the reaction time at ambient temperature in THF were determined by monitoring the pressure variation in a closed reaction vessel and using the Man on the Moon X102 device.36

Compounds 8 and 9 are paramagnetic with a d1 configuration according to their EPR spectra. At a temperature of 77 K in THF, these species exhibit an axial symmetry and g values (Figure S5; g⊥ = 1.978 and g|| = 1.950 for 8; g⊥ = 1.972, and g|| = 1.935 for 9) similar to the previously reported Ti(III) [(NacNac)Ti(CH2tBu)2] species.37

In the solid state, the molecular structures of 8 and 9 (Figure 9) feature a solvent-separated species formed by a cationic [Li(thf)4]+ fragment and the anionic [Ti(ArPDA)2]− (Ar = iPr 8, Mes 9) moiety.

Figure 9.

Solid-state structure of compounds 8 (left) and 9 (right) with thermal ellipsoids at 30% of probability. Hydrogens are omitted for clarity. Only one independent crystallographic molecule of the two found for compound 9 is shown.

The structural data for ArPDA fragments in 8 and 9 are nearly identical to the data found for the bis(diamido) Ti(IV) precursors 5 and 6. Thus, the C–N (1.406(2) Å for 8; 1.405(5) Å for 9) and C–C (1.39(1) Å for 8; 1.389(9) Å for 9) bond distances of compounds 8 and 9 display values analogous to those found for 5 (C–N = 1.4054(9) Å; C–C = 1.38(1) Å) and 6 (C–N = 1.411(2) Å; C–C = 1.387(9) Å), which is also in agreement with the diamido nature of the PDA ligands. The ArPDA ligands in 8 and 9 are arranged in a staggered relative position with dihedral angles slightly larger (73.42(7)° for 8; 69.33(6) and 82.37(6)° for 9)38 than those of 5 (61.94(5)°) and 6 (69.04(9)°). Likewise, the distance between Ti and the Cα=Cα′ fragments is significantly longer in compounds 8 (2.70(2) Å) and 9 (2.83(5) Å) compared with 5 (2.54(1) Å) and 6 (2.57(1) Å). The lower oxidation state in compounds 8 and 9 is reflected in elongated Ti–N bonds. Thus, the titanium–nitrogen average bond lengths of 2.01(3) Å for 8 and 2.00 (1) Å for 9 are longer than the values observed for compounds 5 (1.94(3) Å) and 6 (1.92(3) Å). In comparison to structurally characterized aryl-amido Ti(III) species, the Ti–N bonds are lengthened by ca. 0.1;39 however, they are similar to those reported with the bulkier bis(silyl)amido fragments in [Ti(N(SiMe3)2)3] and solvated species.40

CO2/Epoxide Copolymerization

The structurally similar pair of compounds 5, 8 and 6, 9 differs in the oxidation state of titanium. Therefore, they offer a great opportunity to investigate the influence of the oxidation state of the metal in the functionalization of CO2 via copolymerization with cyclohexene oxide. Since our titanium compounds lack an initiating group, we combined compounds 5, 6 and 8, 9 with [PPN]Cl [PPN = bis(triphenylphosphine)iminium] as the source of an anionic chloride. Using a 2.5 mol % of titanium species along with 2.5 mol % of cocatalyst under 1 bar pressure of CO2 at room temperature during 18 h reveals modest to good conversion levels (30–66%, Table 4, entries 1–4) with marked differences in selectivity based on the oxidation state.

Table 4. Ring-Opening Copolymerization (ROCOP) of CO2 and CHO Using Catalysts 5–9/PPNCla.

| Entry | Catalyst | T (°C) | Cat/[PPN]Cl/CHO (mol %) | Conv. (%)b | Carbonate linkages (%)c | Mn (kg mol–1)d | ĐMd |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5 | RT | 2.5/2.5/100 | 30 | 0e | ND | ND |

| 2 | 6 | RT | 2.5/2.5/100 | 66 | 0e | ND | ND |

| 3 | 8 | RT | 2.5/2.5/100 | 41 | 62 | ND | ND |

| 4 | 9 | RT | 2.5/2.5/100 | 50 | 71 | ND | ND |

| 5f | 9/12-crown-4 | RT | 2.5/2.5/100 | 55 | 70 | ND | ND |

| 6 | 9 | RT | 2.5/5/100 | 80 | >99 | ND | ND |

| 7 | RT | 0/5/100 | 0 | ||||

| 8 | 9 | RT | 0.5/1/100 | 23 | >99 | ND | ND |

| 9 | 9 | 50 | 0.5/1/100 | 57 | >99 | 3.9 | 1.2 |

| 10 | 9 | 70 | 0.5/1/100 | 73 | NDg | ND | ND |

| 11 | 9 | 50 | 0.3/0.6/100 | 53 | >99 | 3.7 | 1.14 |

| 12 | 9 | 50 | 0.2/0.4/100 | 21 | >99 | 3.4 | 1.19 |

| 13 | 9 | 50 | 0.1/0.2/100 | 17 | >99 | 3.1 | 1.14 |

| 14 | [(Salen)Ti(III)Cl] | 50 | 0.5/1/100 | 73 | 56 | ND | ND |

| 15 | [(Salen)Cr(III)Cl] | 50 | 0.5/1/100 | 30 | >99 | 3.9 | 1.27 |

Reaction conditions: 1 bar CO2, 18 h.

Determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy of the crude mixture reaction by comparison of the relative integrals of the resonances assigned to the carbonate (4.65 ppm for the PCHC and 4.00 ppm for trans-CHC) and ether (3.45 ppm) linkages against cis-CHO (3.00 ppm).

Determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy by comparison of the relative integrals of the resonances due to the polymer (4.65 ppm) and ether (3.45 ppm).

Determined by GPC in thf, relative to polystyrene standards. For those cases in which oligomers or a mixture of cyclic carbonate and polycarbonate are obtained, Mn and ĐM values were not determined.

Only the formation of polyether was detected. Therefore, the Mn and ĐM values were not determined.

2.5 mol % of 12-crown-4 was added.

A reliable integral value for polycarbonate and cyclic carbonate could not be obtained due to the close proximity of the signals.

While the Ti(IV) species (5 and 6) provide only polyether with no CO2 intake (Table 4, entries 1–2), the Ti(III) compounds (8 and 9) display the formation of polycarbonate with modest levels of CO2 incorporation (Table 4, entries 3–4). The better performance of the ionic compounds 8 and 9 is most likely due to the combination of the electronic saturation of the Ti center bounded to two PDA2– ligands and the lower oxophilic nature of Ti(III). These factors result in more polarized Ti–O bonds compared with those established by the neutral Ti(IV) species, which would favor the insertion of CO2 into the Ti–O bond during the propagation step. It is noteworthy to mention that despite the fact that Ti(III) in compounds 8 and 9 are expected to be poor Lewis acids, the required epoxide coordination is concentration favored as the reactions are conducted in neat epoxide. In addition, the anionic compounds 8 and 9 feature a lithium cation that can cooperate with titanium toward the copolymerization reaction. This synergic effect between an alkali metal and a transition metal has been well documented by Williams,41 who combining cobalt with alkali metals provides an efficient strategy to promote catalyst performance for the copolymerization of CO2 and epoxides. To determine the potential cooperation of lithium in the catalytic reaction, we conducted the copolymerization of CHO/CO2 using catalyst 9 in the presence of the 12-crown-4 to block the coordination sites of Li. Adding the crown ether does not have an impact on the catalytic activity (Table 4, entry 5), which suggests that the lithium atom does not play a significant role in the catalytic reaction.

Comparison of entries 3 and 4 displays that compound 9, with a more accessible Ti(III) center, shows better activity and selectivity than the sterically bulkier 8, and therefore we continued our studies with species 9. Based on the well-established fact that an increase of the cocatalyst loading enhances the activity and selectivity,42 we increased the catalyst/[PPN]Cl ratio to 1:2, leading to selective (>99%) formation of polycarbonate in an 80% conversion (Table 4, entry 6). Notably, no epoxide conversion was observed when the catalytic reaction was conducted under the optimized conditions without using the titanium catalyst 9 (Table 4, entry 7). Despite the good result obtained in entry 6, isolation of the formed polycarbonate by precipitation proved to be difficult, most likely due to the formation of oligomers. Determined to increase the chain length, we decreased the catalyst loading up to 0.5 mol % while maintaining the 1:2 catalyst/[PPN]Cl ratio. However, it resulted in a drop in conversion to 23% (Table 4, entry 8). The latter was improved by a slight increase in reaction temperature to 50 °C (Table 4, entry 9). In this case, the desired polycarbonate was isolated by precipitation according to a molecular weight of 3.9 kg·mol–1 determined by GPC analysis, which also discloses a narrow dispersity (ĐM = 1.2). An increase in the reaction temperature enhances the conversion to 73%, but impacts the polycarbonate selectivity, as cyclohexene carbonate is now detected (Table 4, entry 10). Holding the reaction temperature to 50 °C and CO2 pressure to 1 bar, our system proved to retain similar levels of activity up to catalyst loading of 0.3 mol % (Table 4, entry 11), generating the desired polycarbonate in 53% conversion, and with comparable molecular weights and dispersity to entry 9. However, a further decrease in the catalyst concentration to 0.2–0.1 mol % (Table 4, entries 12 and 13) leads to a significant decrease in conversion, although the generated polycarbonate shows similar properties (Mn and ĐM).

The MALDI-ToF-MS spectrum of the polycarbonate with a greater value of Mn (Table 4, entry 9) displays one major series of peaks in accordance with the formula [{HO(CHO-CO2)nOCHC4H8CHCl}Na]+, confirming the role of the chloride anion as an initiator. Furthermore, the MALDI-ToF-MS spectrum also shows two additional series of peaks with the same polycarbonate unit as the previous one, albeit with alkoxide fragments as ending groups instead of the chlorine atom.43 Similar results in CO2/epoxide copolymerization have been rationalized by chain transfer reactions with organic alcohols generated upon partial hydrolysis of the epoxide.44 In our case, GC-MS and 1H NMR analysis of cyclohexene epoxide after being exposed to CO2 under the reaction conditions employed during catalysis (18 h, 50 °C) did not show the presence of any organic alcohol (Figure S11). Therefore, it is reasonable to argue that the alkoxides initiating the polymerization process are a consequence of minor side reactions of our titanium catalyst with the epoxide, as it has been reported for similar metal-mediated copolymerization processes.45

Our PDA-Ti(III) catalyst is one of the rare examples of Ti-based systems that can promote the copolymerization of CHO and CO2 at atmospheric pressure.22,46 Thus, the series of tridentate NHC–titanium compounds reported by Le Roux22,46 catalyze CO2/epoxide copolymerization under similar reaction conditions to our system (0.5 bar CO2 and 60 °C). Although for the NHC–Ti systems lower conversions (<38%) are reported, they provide polycyclohexanecarbonate with much greater molecular weights (7.4 kg/mol).

In order to benchmark the catalytic activity and selectivity of compound 9, we conducted the copolymerization of CHO/CO2 under the optimized conditions (0.5 mol %, 50 °C, 1 bar, 18 h) with the Ti(III) [(Salen)TiCl] reported by Wang19 and the homolog [(Salen)Cr(III)Cl]47 complex. Comparison with Salen–Ti(III) (Table 4, entry 14) highlights that our system is less active (55% yield for 9; 70% yield for [(Salen)Ti(III)Cl]), but it is more selective at low CO2 pressures. Contrasting with the highly selective formation of polycarbonate by compound 9, the Salen–Ti complex produces a mixture of polycarbonate and cyclic carbonate (Table 4, entry 14). Surprisingly, when compound 9 is compared with [(Salen)Cr(III)Cl] (Table 4, entry 15), both catalytic systems are highly selective, but our Ti(III) catalyst is slightly more active, providing higher conversions.

Finally, the comparison of the catalytic activity of complex 9 with the most active Ti(IV) systems [(Boxdipy)TiCl]21 (0.05 mol %, 12 h, 20 bar, 45%, 13.0 kg/mol), [(Salalen)TiCl]23 (0.2 mol %, 10 h, 70 °C, 40 bar, 44%, 4.2 kg/mol), and [(ATP)MeTiOiPr] (ATP = amino-tris(phenolate))44 (0.2 mol %, 4 h, 80 °C, 40 bar, 48%, 15.7 and 6.8 kg/mol) reveals that albeit our Ti(III) system is capable to mediate the copolymerization reaction at atmospheric pressure and relatively mild reaction temperatures, it exhibits lower catalytic activity (0.5 mol %, 18 h) and generates polycarbonate with moderate molecular weight (3.9 kg/mol).

Conclusions

We describe the synthesis and characterization of bis(PDA)-Ti(III) species and their use for the functionalization of CO2 under atmospheric reaction conditions. Chemical reduction of the Ti(IV) precursors turned out to be the only productive route toward the low-valent titanium compound. Upon combination of X-ray studies, 1H NMR spectroscopy, reaction pressure monitoring, and DFT calculations, we disclose full details for the synthetic methodology from Ti(IV) to Ti(III). The reaction between two equivalents of the corresponding lithiated PDA ligand and the Ti(IV) chloride results in partial transmetalation, forming the heterobimetallic Ti(IV)/Li complexes. Then, the Ti(IV)/Li compounds react with [LiBHEt3] to generate first the Ti(IV)-bis(amido) compounds. These complexes are capable to accept a hydride fragment from [LiBHEt3], leading to a putative complex “[Li(thf)4][TiH(ArPDA)2],” similar to the isolated species [Li(thf)4][Ti(NMe2)(ArPDA)2] 7. Finally, these titanium hydride species react through bimetallic reductive elimination to form the final Ti(III) compounds along with H2 release.

After an optimization process, the Ti(III) bis(diamido) 8 and 9 show good catalytic activity for the catalytic transformation of CO2 into polycarbonate via copolymerization with cyclohexene epoxide. Most relevant, the current studies provide a titanium species capable of operating under low CO2 pressures and selectively, so far only accessible for the bis-aryloxy N-heterocyclic carbene (NHC) titanium reported by Le Roux. Furthermore, the Ti(III) compounds display catalytic activity and selectivity similar to Salen–chromium compounds. Considering the structural versatility of the employed ligands and the levels of activity and selectivity in the copolymerization processes, the development of more efficient catalysts operating at lower catalyst loading with further epoxides, including biorenewable and those extracted as waste products, to generate polycarbonates of larger molecular weights is envisioned.

Experimental Section

General Considerations

All reactions were performed under a protective atmosphere using either standard Schlenk techniques (argon) or in an MBraun dry box (argon). [d1]-Chloroform and methanol were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemicals and used as received. [d6]-Benzene and [d8]-tetrahydrofuran were purchased from Eurisotop and toluene, hexane, and tetrahydrofuran from Scharlab. Solvents were dried by heating to reflux over the appropriated drying agents: [d6]-Benzene, toluene, and hexane (Na/K alloy), [d8]-tetrahydrofuran (Na), and tetrahydrofuran (Na/Benzophenone) and distilled prior to use. CO2 (99.9993%) was commercially obtained from Linde Gas España and used without further purification. Commercially available reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemicals; [TiCl4(thf)2],48N,N′-bis(2,4,6-trimethylphenyl)-o-phenylenediamine (MesPDAH2),49 [Li2(MesPDA)(thf)3],27bN,N′-bis(2,6-isopropylphenyl)-o-phenylenediamine(iPrPDAH2),50 [Li2(iPrPDA)(thf)3],27b [(Salen)Ti(III)Cl],19 and [(Salen)Cr(III)Cl]47 were synthesized as described in the literature. NMR spectra were recorded on a Varian Mercury-VX spectrometer operating at 300 MHz for 1H, 75 MHz for 13C{1H}, or on a Bruker Neo spectrometer operating at 400 MHz for 1H, 100 MHz for 13C{1H}, and 155.4 MHz for 7Li and on a Unity-500 Plus (500MHz for 1H) for variable temperature experiment. 1H, 13C{1H}, and 7Li chemical shifts are expressed in parts per million (δ, ppm) and referenced to residual solvent peaks. All coupling constants (J) are expressed in absolute values (Hz) and resonances are described as follows: s (singlet), d (doublet), hp (heptuplet), and m (multiplet). The NMR assignments were performed, in some cases, with the help of 1H,13C-HSQC and 1H,13C-HMBC experiments. Elemental analyses (C, H, N) were performed with a LECO CHNS-932 microanalyzer. Samples for IR spectroscopy were prepared as KBr pellets and recorded on the Bruker FT-IR-ALPHA II spectrophotometer (4000–400 cm–1). CW–EPR spectra were performed in a Bruker EMX spectrometer. Monitoring of H2 release was carried out in a Man on the Moon X102 kit micro-reactor in the glovebox. The molecular weights (Mn) and the molecular mass distributions (Mw/Mn) of polymer samples were measured by gel permeation chromatography (GPC) performed on an Agilent 1260 Infinity II equipped with two GPC/columns PL gel 5 μm MIXED-D 300 × 7.5 mm and a G7162A refractive index detector. Calibration was performed with polystyrene (PS) standards in a range of molecular weights of 580–364,000 Da. MALDI-ToF-MS spectra were acquired with a Bruker Autoflex II ToF/ToF spectrometer (Billerica, MA, USA), using a nitrogen laser source (337 nm, 3 ns) in linear mode with a positive acceleration voltage of 20 kV.

Synthesis of Complex [{TiCl(iPrPDA)}(μ-iPrPDA){Li(thf)}] (3)

A 100 mL Schlenk vessel was charged in the glovebox with [Li2(iPrPDA)(thf)3] (1) (0.56 g, 0.88 mmol) and [TiCl4(thf)2] (0.147 g, 0.44 mmol) in 20 mL of hexane. The suspension was stirred for 1 h, filtered through a medium porosity glass frit to remove LiCl, and the resulting solution was dried under vacuum to yield 3 as a black solid (Yield: 75%, 0.35 g, 0.33 mmol). IR (KBr, cm–1): ṽ = 3057 (m), 2928 (m), 2867 (m) 1596 (s), 1527 (s), 1458 (s), 1319 (s), 1258 (m), 1170 (s), 1039 (s), 792 (m), 742 (m). 1H NMR (300 MHz, 298K, C6D6): 7.29–7.00 (m, 12H, CHAr-iPr), 6.85–6.72 (m, 4H, C6H4[N(iPr)]2), 6.35–6.24 (m, 2H, C6H4[N(iPr)]2), 5.40–5.30 (m, 2H, C6H4[N(iPr)]2), 3.78–3.68 [m, 2H, CH(CH3)2], 3.66–3.55 (m, 2H, CH(CH3)2), 3.12–3.02 (m, 8H, thf), 3.00–2.80 (m, 4H, CH(CH3)2), 1.45 (d, 6H, J = 9 Hz, CH(CH3)2), 1.27 (d, 6H, J = 9 Hz, CH(CH3)2), 1.23 (d, 6H, J = 9 Hz, CH(CH3)2), 1.22 (d, 6H, J = 9 Hz, CH(CH3)2), 1.17 (d, 6H, J = 9 Hz, CH(CH3)2), 1.09 (d, 6H, J = 9 Hz, CH(CH3)2), 0.96 (d, 6H, J = 9 Hz, CH(CH3)2), 0.73 (d, 6H, J = 9 Hz, CH(CH3)2). 13C-{1H}-NMR (75 MHz, 298K, C6D6): δ 166.2, 148.0, 145.8,145.0, 142.7, 141.8, 139.4, 127.1 100.1 (Cq), 127.1, 124.3, 124.2, 124.1, 123.9, 117.0, 116.5, 100.5 (CHAr), 68.2 (CH2-thf), 28.2, 28.1, 27.9, 25.6, 25.5, 25.3, [CH(CH3)2, CH(CH3)2], 25.2 (CH2, thf), 25.1, 23.9, 23.0, 22.79 [CH(CH3)2, CH(CH3)2]. 7Li NMR (155.4 MHz, 298K, C6D6) δ 2.09. Elemental analysis (%) Calcd. for C68H94N4O2ClTiLi (MW = 1089.78): C, 74.95; H, 8.69; N, 5.14. Found: C, 74.78; H, 8.55; N, 4.98.

Synthesis of Complex [{TiCl(MesPDA)}(μ-MesPDA){Li(thf)2}] (4)

A 100 mL Schlenk vessel was charged in the glovebox with [Li2(MesPDA)(thf)3] (2) (0.52 g, 0.9 mmol) and [TiCl4(thf)2] (0.15 g, 0.45 mmol) in 20 mL of hexane. The suspension was stirred overnight. Then, the solvent was removed under reduced pressure, affording a purple solid, which was extracted with toluene and filtered through a medium porosity glass frit. Evaporation of toluene under vacuum yields 4 as a dark purple solid (Yield: 67%, 0.276 g, 0.301 mmol). IR (KBr, cm–1): ṽ = 3039 (m), 2916 (m), 2858 (m), 1597 (m), 1525 (s), 1446 (s), 1231 (s), 1014 (w), 885 (w), 742 (m), 560 (w). 1H NMR (300 MHz, 298K, C6D6) δ 7.07 (s, 2H, CH, CHAr-Mes), 7.06–7.00 (m, 2H, C6H4[N(Mes)]2), 6.80 (s, 2H, CH, CHAr-Mes), 6.73 (s, 2H, CH, CHAr-Mes), 6.70 (s, 2H, CH, CHAr-Mes), 6.63–6.56 (m, 2H, C6H4[N(Mes)]2), 6.41–6.35 (m, 2H, C6H4[N(Mes)]2), 5.44–5.38 (m, 2H, C6H4[N(Mes)]2), 3.38–3.26 (m, 8H, thf), 2.56 (s, 6H, CH3), 2.42 (s, 6H, CH3), 2.27 (s, 6H, CH3), 2.04 (s, 6H, CH3), 2.01 (s, 6H, CH3), 1.71 (s, 6H, CH3), 1.24–1.12 (m, 8H, thf). 13C-{1H}-NMR (75 MHz, 298K, C6D6) δ 162.4, 148.32, 146.9 (Cq), 134.7, 129.5 (CHAr), 129.5 (Cq), 129.2, 129.1, 129.0, 127.0, 125.1, 117.9, 114.1, 101.6 (CHAr), 68.0 (CH2, thf), 25.7 (CH2, thf), 21.2, 21.0, 20.3, 20.2, 19.3, 18.9 (CH3, Mes). 7Li-RMN (155.4 MHz, 298K, C6D6) δ 2.22. Elemental analysis (%) Calcd. for C56H68N4O2ClLiTi (MW = 919.44): C, 73.15; H, 7.45; N, 6.09. Found: C, 73.41; H, 7.63; N, 6.00.

Synthesis of Complex [Ti(iPrPDA)2] (5)

A 100 mL Carius tube fitted with a Young’s valve was charged in the glovebox with [{TiCl(iPrPDA)}(μ-iPrPDA){Li(thf)}] (3) (0.2 g, 0.18 mmol) and lithium dimethylamide (0.009 g, 0.18 mmol) in 10 mL of toluene. The reaction mixture was heated for 18 h at 40 °C. Then, the volatiles were removed under reduced pressure. The black solid was extracted with hexane, filtered through a medium porosity glass frit, and dried under vacuum to give rise to 5 as a black solid (Yield: 67%, 0.108 g, 0.12 mmol). IR (KBr, cm–1): ṽ = 3060 (w), 2963 (s), 2868 (m) 1597 (w), 1500 (m), 1459 (s), 1259 (m), 746 (m), 587 (w). 1H NMR (300 MHz, 298K, C6D6): δ 7.44–7.31 (m, 4H, CHAr-iPr), 7.27–7.17 (m, 3H, CHAr-iPr), 7.10–7.00 (m, 5H, CHAr-iPr), 6.97–6.86 (m, 2H, C6H4[N(iPr)]2), 6.68–6.61 (m, 2H, C6H4[N(iPr)]2), 6.61–6.50 (m, 2H, C6H4[N(iPr)]2), 6.33–6.22 (m, 2H, C6H4[N(iPr)]2), 2.96 (hp, 2H, J = 6 Hz, CH(CH3)2), 2.84 (hp, 2H J = 6 Hz, CH(CH3)2), 2.68 (hp, 2H, J = 6 Hz, CH(CH3)2), 2.03 (hp, 2H, J = 6 Hz, CH(CH3)2), 1.11 (d, 6H, J = 6 Hz, CH(CH3)2), 1.06 (d, 6H, J = 6 Hz, CH(CH3)2), 1.03 (d, 6H, J = 6 Hz, CH(CH3)2), 0.86 (d, 6H, J = 6 Hz, CH(CH3)2), 0.72 (d, 6H, J = 6 Hz, CH(CH3)2), 0.60 (d, 6H, J = 6 Hz, CH(CH3)2), 0.57 (d, 6H, J = 6 Hz, CH(CH3)2), 0.53 (d, 6H, J = 6 Hz, CH(CH3)2). 13C-{1H}-NMR (75 MHz, 298K, C6D6): 150.1, 144.5, 144.3, 143.7, 142.6, 142.4 (Cq), 126.2, 125.6, 124.5, 124.2, 123.7, 123.4, 116.4 (CHAr), 29.4, 28.8, 28.56, 28.50, 28.4, 27.9, 25.8, 25.7, 24.6, 24.4, 22.8, 22.7 (CH(CH3)2, CH(CH3)2). Elemental analysis (%) Calcd. for C60H76N4Ti (MW = 901.16): C, 79.97; H, 8.50; N, 6.22. Found: C, 79.77; H, 8.55; N, 6.48.

Synthesis of Complex [Ti(MesPDA)2] (6)

A toluene solution (20 mL) of [{TiCl(MesPDA)}(μ-MesPDA){Li(thf)2}] (4) (0.43 g, 0.47 mmol) was heated at 60 °C for 18 h. The reaction mixture was filtered through a medium porosity glass frit and dried under vacuum to produce compound 6 as a black solid (Yield: 85%, 0.290 g, 0.39 mmol). IR (KBr, cm–1): ṽ = 3046 (w), 2965 (w), 2915 (m), 2854 (w), 1597 (m), 1480 (s), 1258 (s), 1153 (m), 845 (m), 745 (m), 562 (w). 1H NMR (300 MHz, 298K, C6D6) δ 6.99 (m, 4H, C6H4[N(Mes)]2), 6.72 (s, 8H, CHAr-Mes), 6.60 (m, 4H, C6H4[N(Mes)]2), 2.10 (s, 24H, CH3), 1.88 (s, 12H, CH3). 13C-{1H}-NMR (75 MHz, 298K, C6D6) δ 145.9, 134.7 (Cq), 132.4, 129.5, 125.2, 117.3 (CHAr), 21.00, 18.79 (CH3, Mes). Elemental analysis (%) Calcd. for C48H52N4Ti (MW = 732.84): C, 78.67; H, 7.15; N, 7.56. Found: C, 78.76; H, 7.07; N, 7.69.

Synthesis of Complex [Li(thf)4][Ti(MesPDA)2(N(CH3)2)] (7)

A 50 mL Schlenk vessel was charged in the glovebox with [{TiCl(MesPDA)}(μ-MesPDA){Li(thf)2}] (4) (0.1 g, 0.1 mmol) and lithium dimethylamide (0.005 g, 0.1 mmol) in 10 mL of benzene. The suspension was stirred for 3 days at 40 °C, and then the solvent was removed under reduced pressure. The product was extracted with toluene and filtered through a medium porosity glass frit. The filtrate was stored at room temperature affording species 7 as dark red crystals (Yield: 53%, 0.057 g, 0.053 mmol). IR (KBr, cm–1): ṽ = 2958 (m), 2915 (m), 2856 (m), 1599 (m), 1504 (s), 1483 (s), 1405 (m), 1257 (s), 1037 (m), 741 (m), 495 (w). 1H NMR (300 MHz, 298K, C6D6) δ 6.70 (s, 4H, CHAr-Mes), 6.62 (s, 4H, CHAr-Mes), 6.36–6.30 (m, 4H, C6H4[N(Mes)]2), 5.92–5.85 (m, 4H, C6H4[N(Mes)]2), 3.19 (s, 6H, N(CH3)2), 3.11 (m, 16H, thf), 2.38 (s, 12H, CH3), 2.36 (s, 12H, CH3), 2.10 (s, 12H, CH3), 1.21–1.14 (m, 16H, thf). 13C-{1H}-NMR (75 MHz, 298K, C6D6) δ 150.1 (Cq), 134.5, 132.8 (CHAr), 132.2 (Cq), 129.2, 128.6, 128.5, 127.3, 125.6 (CHAr), 43.9 (N(CH3)2), 21.3, 19.6, 19.4 (CH3, Mes). 7Li NMR (155.4 MHz, 298K, C6D6): δ 1.04. Elemental analysis (%) Calcd. for C66H90N5O4Ti (MW = 1072.28): C, 73.93; H, 8.46; N, 6.53. Found: C, 73.76; H, 8.27; N, 6.70.

Synthesis of Complex [Li(thf)4][Ti(iPrPDA)2] (8)

A 100 mL Carius tube fitted with a Young′s valve was charged in the glovebox with [{TiCl(iPrPDA)}(μ-iPrPDA){Li(thf)}] (3) (0.17 g, 0.16 mmol) and 15 mL of toluene. The toluene solution was cooled to 0 °C and then lithium triethylborohydride (1 M in thf, 0.16 mL, 0.16 mmol) was added. After stirring at room temperature for 18 h, the solution was filtered through a medium porosity glass frit. Then, the solvent was removed under reduced pressure. The solid was dissolved in pentane, and the resulting solution was cooled at −30 °C for 24 h, affording single dark crystals identified as 8 (Yield: 55%, 0.095 g, 0.09 mmol). Alternatively, complex 8 can be also prepared by reacting complex 5 (0.1 g, 0.11 mmol) with 1 eq of lithium triethylborohydride (1 M in thf, 0.11 mL, 0.11 mmol) during 18 h and room temperature. (Yield: 53%, 0.062 g, 0.053 mmol). IR (KBr, cm–1): ṽ = 3057 (w), 2964 (m), 2929 (s) 1459 (s), 1436 (s), 1248 (s), 1169 (m), 929 (m), 900 (w), 794 (w), 746 (w). Elemental analysis (%) Calcd. for C76H108N4O4LiTi (MW = 1196.53): C, 76.29; H, 9.10; N, 4.68. Found: C, 75.83; H, 8.94; N, 4.48.

Synthesis of Complex [Li(thf)4][Ti(MesPDA)2] (9)

A 50 mL Carius tube fitted with a Young’s valve was charged in the glovebox with the compound [{TiCl(MesPDA)}(μ-MesPDA){Li(thf)2}] (4) (0.56 g, 0.61 mmol) and 10 mL of toluene. To the toluene solution at 0 °C lithium triethylborohydride (1 M in thf, 0.61 mL, 0.61 mmol) was added. The reaction mixture was allowed to warm up to room temperature and stirred for 18 h. The resulting suspension was filtered through a medium porosity glass frit. The filtrate was concentrated to half volume under vacuum and cooled to −30 °C to afford 9 as dark green crystals. (Yield: 47%, 0.31 g, 0.3 mmol). Alternatively, complex 9 can be also obtained by reacting compound 6 (0.50 g, 0.68 mmol) with lithium triethylborohydride (1 M in thf, 0.68 mL, 0.68 mmol) during 18 h and room temperature. (Yield: 62%, 0.43 g, 0.42 mmol). IR (KBr, cm–1): ṽ = 2996 (m), 2915 (m), 1635 (m), 1542 (m), 1471 (s), 1258 (s), 1197 (m), 1149 (m), 1038 (m), 879 (s), 764 (m), 742 (m). Elemental analysis (%) Calcd. for C64H84N4O4TiLi (MW = 1028.21): C, 74.26; H, 8.23; N, 5.23. Found: C, 73.87; H, 8.20; N, 5.87.

General Procedures for Catalytic Tests

All low-pressure reactions were carried out in a magnetically stirred Carius tube fitted with a Young’s valve.

A Carius tube fitted with a Young’s valve was charged in the glovebox with cyclohexene oxide (0.58–14.59 mmol), {[PPN]Cl} (0.017 g, 0.029 mmol), and titanium catalyst (0.014 mmol) with a magnetic stirrer bar. The argon atmosphere was replaced by 1 bar of CO2 using a Schlenk line and the reaction mixture was stirred for 18 h. The reaction crude was purified by evaporation of the excess of cis-CHO under reduced pressure. Then, polymers were dissolved in dichloromethane and precipitated with methanol to form a white solid. The isolated polymers were dried under vacuum at 50 °C for 48 h.

The conversion of cyclohexene oxide into poly(cyclohexene carbonate) (PCHC) was determined by normalization of the integrals of the methylene proton resonances in the 1H NMR spectra for the carbonate (δ = 4.65 ppm for PCHC and 4.00 ppm for trans-cyclic carbonate) and ether linkages (δ = 3.45 ppm) toward CHO (δ = 3.00 ppm) and expressed as a percentage of CHO conversion versus the theoretical maximum (100%).

The percentage of carbonate linkages was determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy of a sample and expressed as a percentage of carbonate linkages versus the theoretical maximum (100%), determined by comparison of the relative integrals of the resonances assigned to the carbonate (4.65 ppm for PCHC and 4.00 ppm for trans-cyclic carbonate) and ether (3.45 ppm) linkages, if present.

Crystal Structure Determination of Complexes 3–9

Single crystals for compounds 3, 5, and 8 were deposited from pentane solutions stored at −30 °C, while for complexes 4 and 6 crystals were grown up by slow diffusion of a toluene solution into a second layer of hexane. Compounds 7 and 9 were crystalized by slow evaporation of saturated benzene and tetrahydrofuran solutions, respectively.

The intensity data sets for 4, 5, 6, and 9 were collected at 200 K on a Bruker-Nonius Kappa CCD diffractometer equipped with graphite-monochromated Mo Kα radiation (λ = 0.71073 Å) and an Oxford Cryostream 700 unit, while those for 3, 7, and 8 were collected at 150 K on a Bruker D8 Venture diffractometer equipped with multilayer optics for monochromatization and collimator, Mo Kα radiation (λ = 0.71073 Å), and an Oxford Cryostream 800 unit. Crystallographic data for all complexes are presented in Tables S4 and S5.

The structures were solved by applying intrinsic phasing (SHELXT)51 using the Olex252 package and refined by least squares against F2 (SHELXL).53 All non-hydrogen atoms were anisotropically refined, while hydrogen atoms were placed at idealized positions and refined using a riding model.

Computational Details

All DFT calculations have been carried out using the GAUSSIAN16 program.54 Geometry optimizations have been performed without any symmetry restrictions, taking into account dispersion effects with the Grimme and co-workers DFT-D3BJ correction55,56 at the B3LYP-D3BJ/def2SVP level of theory.57−59 After geometry optimization, analytical frequency calculations have been performed at the same level of theory to evaluate enthalpy and entropy corrections to the Gibbs energies at 298.15 K and to ensure that all frequencies were positive for all intermediates. Single-point calculations on the equilibrium geometries, including the effect of the solvent (toluene, via the self-consistent reaction field – SCRF – method using the SMD solvation model)60 and the dispersion effects (Esp), have been carried out at the B3LYP-D3BJ(SMD)/def2TZVP level of theory.61 Finally, the total Gibbs energy values (G) have been corrected using the GoodVibes code62 so that frequencies below 100 are not treated with the harmonic approximation, but rather with the quasi-harmonic approximation as described by Grimme.63

Effective oxidation states (EOS), spin-resolved effective fragment orbitals (EFOs), and fuzzy atom Mayer bond orders64 were obtained using APOST-3D65 using a 50 × 266 atomic grid for the numerical integrations and the topological fuzzy Voronoi cells (TFVC)66 for real-space partitioning.

Acknowledgments

I.S. and M.N. acknowledge the Comunidad de Madrid for their contract funded through the Research Talent Attraction Program (2018-T1/AMB-11478). The authors also thank Dr. Miguel Mena and Dr. Avelino Martín for their insightful discussions and advice with single-crystal crystallography, respectively. The authors finally want to thank Prof. Marta E. G. Mosquera and Dr. M. Palenzuela for allowing them to use their GPC instrument.

Data Availability Statement

The optimized XYZ Cartesian coordinates at B3LYP-D3BJ/def2SVP level for all of the structures can be found in the following database link, in a very convenient format and allowing easy visualization and extraction of the XYZ file if needed: https://doi.org/10.19061/iochem-bd-4-52.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.inorgchem.3c01249.

Effective oxidation state (EOS) analysis (Tables S1 and S2). Changes in Gibbs free energies and optimized geometries for the conversion of 3 to 5 and 4 to 6 (Table S3 and Figures S1–S4). EPR spectroscopy (Figure S5). Monitoring of H2 evolution over time (Figures S6 and S7). GPC, 1H NMR, and MALDI-ToF analysis of poly(cyclohexene carbonate) (Figures S8–S10). GC-MS of cyclohexene epoxide after stirring for 18 h at 50 °C under a CO2 atmosphere (Figure S11). Reaction between [ArPDAH2] and [Ti(CH2Ph)4] (Figures S12 and S13). Reaction between [Li2(ArPDA)(thf)3] and [TiCl3(thf)3] (Figures S14 and S15). Crystallographic data for compounds 3–9 (Tables S4 and S5). Van der Waals models for compounds 3 and 4 (Figure S16). Spectroscopical details for compounds 3–9 (Figures S17–S37) (DOCX)

This work was supported by the Comunidad de Madrid (Research Talent Attraction Program 2018-T1/AMB-11478), Programa Estímulo a la Investigación de Jovenes Investigadores (CM/JIN/2019-030 and CM/JIN/2021-031), and the Universidad de Alcalá (PIUAH22/CC-049).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Beaumier E. P.; Pearce A. J.; See X. Y.; Tonks I. A. Modern applications of low-valent early transition metals in synthesis and catalysis. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2019, 3, 15–34. 10.1038/s41570-018-0059-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCallum T.; Wu X.; Lin S. Recent Advances in Titanium Radical Redox Catalysis. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 84, 14369–14380. 10.1021/acs.joc.9b02465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chirik P. J.; Bouwkamp M. W.. 4.03 – Complexes of Titanium in Oxidation States 0 to II. In Comprehensive Organometallic Chemistry III; Mingos D. M. P.; Crabtree R. H., Eds.; Elsevier: Oxford, 2007; pp 243–279. [Google Scholar]

- Fortier S.; Gomez-Torres A. Redox chemistry of discrete low-valent titanium complexes and low-valent titanium synthons. Chem. Commun. 2021, 57, 10292–10316. 10.1039/D1CC02772G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solowey D. P.; Mane M. V.; Kurogi T.; Carroll P. J.; Manor B. C.; Baik M. -H.; Mindiola D. J. A new and selective cycle for dehydrogenation of linear and cyclic alkanes under mild conditions using a base metal. Nat. Chem. 2017, 9, 1126–1132. 10.1038/nchem.2795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguilar-Calderón J. R.; Metta-Magana A. J.; Noll B.; Fortier S. C(sp3)–H Oxidative Addition and Transfer Hydrogenation Chemistry of a Titanium(II) Synthon: Mimicry of Late-Metal Type Reactivity. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 14101–14105. 10.1002/anie.201607441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Mullins S. M.; Duncan A. P.; Bergman R. G.; Arnold J. Reactivity of a Titanium Dinitrogen Complex Supported by Guanidinate Ligands: Investigation of Solution Behavior and a Novel Rearrangement of Guanidinate Ligands. Inorg. Chem. 2001, 40, 6952–6963. 10.1021/ic010631+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Hagadorn J. R.; Arnold J. Titanium(II), -(III), and -(IV) Complexes Supported by Benzamidinate Ligands. Organometallics 1998, 17, 1355–1368. 10.1021/om970933c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nikiforov G. B.; Vidyaratne I.; Gambarotta S.; Korobkov I. Titanium-Promoted Dinitrogen Cleavage, Partial Hydrogenation, and Silylation. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 7415–7419. 10.1002/anie.200903648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Heins S. P.; Zhang B.; MacMillan S. N.; Cundari T. R.; Wolczanski P. T. Oxidative Additions to Ti(IV) in [(dadi)4-]TiIV(THF) Involve Carbon–Carbon Bond Formation and Redox-Noninnocent Behavior. Organometallics 2019, 38, 1502–1515. 10.1021/acs.organomet.8b00930. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Heins S. P.; Morris W. D.; Cundari T. R.; MacMillan S. N.; Lobkovsky E. B.; Livezey N. M.; Wolczanski P. T. Complexes of [(dadi)Ti(L/X)]m That Reveal Redox Non-Innocence and a Stepwise Carbene Insertion into a Carbon–Carbon Bond. Organometallics 2018, 37, 3488–3501. 10.1021/acs.organomet.8b00188. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Heins S. P.; Wolczanski P. T.; Cundari T. R.; MacMillan S. N. Redox non-innocence permits catalytic nitrene carbonylation by (dadi)Ti = NAd (Ad = adamantyl). Chem. Sci. 2017, 8, 3410–3418. 10.1039/C6SC05610E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y.; Petersen J. L.; Milsmann C. A. A Luminescent Zirconium(IV) Complex as a Molecular Photosensitizer for Visible Light Photoredox Catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 13115–13118. 10.1021/jacs.6b05934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma M.; Wang H.; Wang J.; Shen L.; Zhao Y.; Xu W. -H.; Wu B.; Yang X. -J. Mg-bonded compounds with N,N′-dipp-substituted phenanthrene-diamido and o-phenylene-diamino ligands. Dalton Trans. 2019, 48, 2295–2299. 10.1039/C9DT00028C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma M.; Shen L.; Wang H.; Zhao Y.; Wu B.; Yang X. -J. N,N′-Dipp-o-phenylene-diamido Dianion: A Versatile Ligand for Main Group Metal–Metal-Bonded Compounds. Organometallics 2020, 39, 1440–1447. 10.1021/acs.organomet.0c00136. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aoyagi K.; Gantzel P. K.; Kalai K.; Tilley T. D. Bis(triisopropylsilyl)-o-phenylenediamido Complexes of Titanium and Zirconium: Investigation of a New Ancillary Ligand. Organometallics 1996, 15, 923–927. 10.1021/om950671j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Tabernero V.; Cuenca T.; Mosquera M. E. G.; de Arellano C. R. Early transition metal derivatives stabilised by the phenylenediamido 1,2-C6H4(NCH2tBu)2 ligand: Synthesis, characterisation and reactivity studies: Crystal structures of [Ta{1,2-C6H4(NCH2tBu)2}2Cl] and [Zr{(1,2-C6H4(NCH2tBu)2}(NMe2)(μ-NMe2)]2. Polyhedron 2009, 28, 2545–2554. 10.1016/j.poly.2009.05.055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Tabernero V.; Maestre M. C.; Jiménez G.; Cuenca T.; de Arellano C. R. Cationic Cyclopentadienyl Phenylenediamido Titanium Species Generated by Reaction of TiCpR[1,2-C6H4(NCH2tBu)2]R (CpR = η5-C5H5, η5-C5Me5; R = CH3, CH2Ph) with B(C6F5)3. X-ray Molecular Structure of Ti(η5-C5Me5)[1,2-C6H4(NCH2t-Bu)2][μ-MeB(C6F5)3]. Organometallics 2006, 25, 1723–1727. 10.1021/om051088y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Tabernero V.; Cuenca T. Studies of the Nature of the Catalytic Species in the α-Olefin Polymerisation Processes Generated by the Reaction of Diamido(cyclopentadienyl)titanium Complexes with Aluminium Reagents as Cocatalysts. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2005, 2005, 338–346. 10.1002/ejic.200400661. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Tabernero V.; Cuenca T.; Herdtweck E. Preparation of Diamidochloro(cyclopentadienyl) titanium Derivatives as Pre-Catalysts for Olefin Polymerization – X-ray Molecular Structure of [Ti(η5-C5H5){1,2-C6H4(NCH2CH2CH3)2}Cl] and [Ti{η5-C5H4(SiMe3)}{1,2-C6H4(NCH2CH2CH3)2}Cl]. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2004, 2004, 3154–3162. 10.1002/ejic.200400138. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt A. J.; Farmer A. J.; Clark A. J.. Elemental Sustainability and the Importance of Scarce Element Recovery, Element Recovery and Sustainability The Royal Society of Chemistry, 2013; pp 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Haynes W. M.; Lide D. R.; Bruno T. J.. CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics; CRC Press, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Egorova K. S.; Ananikov V. P. Toxicity of Metal Compounds: Knowledge and Myths. Organometallics 2017, 36, 4071–4090. 10.1021/acs.organomet.7b00605. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- For recent reviews see:; a Bhat G. A.; Darensbourg D. J. Progress in the catalytic reactions of CO2 and epoxides to selectively provide cyclic or polymeric carbonates. Green Chem. 2022, 24, 5007–5034. 10.1039/D2GC01422J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Huang J.; Worch J. C.; Dove A. P.; Coulembier O. Update and Challenges in Carbon Dioxide-Based Polycarbonate Synthesis. ChemSusChem 2020, 13, 469–487. 10.1002/cssc.201902719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Kozak C. M.; Ambrose K.; Anderson T. S. Copolymerization of carbon dioxide and epoxides by metal coordination complexes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2018, 376, 565–587. 10.1016/j.ccr.2018.08.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.; Qin Y.; Wang X.; Wang F. Trivalent Titanium Salen Complex: Thermally Robust and Highly Active Catalyst for Copolymerization of CO2 and Cyclohexene Oxide. ACS Catal. 2015, 5, 393–396. 10.1021/cs501719v. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mandal M. Group 4 complexes as catalysts for the transformation of CO2 into polycarbonates and cyclic carbonates. J. Organomet. Chem. 2020, 907, 121067–121078. 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2019.121067. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nakano K.; Kobayashi K.; Nozaki K. Tetravalent Metal Complexes as a New Family of Catalysts for Copolymerization of Epoxides with Carbon Dioxide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 10720–10723. 10.1021/ja203382q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quadri C. C.; Lalrempuia R.; Hessevik J.; Törnroos K. W.; Le Roux E. Structural Characterization of Tridentate N-Heterocyclic Carbene Titanium(IV) Benzyloxide, Silyloxide, Acetate, and Azide Complexes and Assessment of Their Efficacies for Catalyzing the Copolymerization of Cyclohexene Oxide with CO2. Organometallics 2017, 36, 4477–4489. 10.1021/acs.organomet.7b00705. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.; Qin Y.; Wang X.; Wang F. Coupling reaction between CO2 and cyclohexene oxide: selective control from cyclic carbonate to polycarbonate by ligand design of salen/salalen titanium complexes. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2014, 4, 3964–3972. 10.1039/C4CY00752B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Darensbourg D. J.; Mackiewicz R. M. Role of the Cocatalyst in the Copolymerization of CO2 and Cyclohexene Oxide Utilizing Chromium Salen Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 14026–14038. 10.1021/ja053544f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For some relevant examples of the σ2,π-coordination see:; a Anga S.; Naktode K.; Adimulam H.; Panda T. Titanium and zirconium complexes of the N,N′-bis(2,6-diisopropylphenyl)-1,4-diaza-butadiene ligand: syntheses, structures and uses in catalytic hydrosilylation reactions. Dalton Trans. 2014, 43, 14876–14888. 10.1039/C4DT02013H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Matsuo Y.; Mashima K.; Tani K. Half-Metallocene Tantalum Complexes Bearing Methyl Methacrylate (MMA) and 1,4-Diaza-1,3-diene Ligands as MMA Polymerization Catalysts. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2001, 40, 960–962. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Scholz J.; Hadi G. A.; Thiele K.; Gorls H.; Weimann R.; Schumann H.; Sieler J. 1,4-Diaza-1,3-diene (DAD) complexes of early transition elements. Syntheses, structures and molecular dynamics of mono- and bis(η5-cyclopentadienyl)titanium-, zirconium- and hafnium(DAD) complexes. Crystal- and molecular structures of CpTi(DAD)CH2Ph, [CpTi(DAD)]2O, CpZr[(DAD)(NO)] and Cp2Hf(DAD). J. Organomet. Chem. 2001, 626, 243–259. 10.1016/s0022-328x(01)00705-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ray K.; Petrenko T.; Wieghardt K.; Neese F. Joint spectroscopic and theoretical investigations of transition metal complexes involving non-innocent ligands. Dalton Trans. 2007, 1552–1566. 10.1039/b700096k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortho-phenylendiamido metal compounds with similar metrical data can be found in:; a Robinson S.; Davies E. S.; Lewis W.; Blake A. J.; Liddle S. T. Alkali metal derivatives of an ortho-phenylene diamine. Dalton Trans. 2014, 43, 4351–4360. 10.1039/C3DT52632A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Janes T.; Rawson J. M.; Song D. Syntheses and structures of Li, Fe, and Mo derivatives of N,N′-bis(2,6-diisopropylphenyl)-o-phenylenediamine. Dalton Trans. 2013, 42, 10640–10648. 10.1039/c3dt51063h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For some examples see:; a Zhao D.; Gao W.; Mu Y.; Ye L. Direct Synthesis of Titanium Complexes with Chelating cis-9,10-Dihydrophenanthrenediamide Ligands through Sequential C-C Bond-Forming Reactions from o-Metalated Arylimines. Chem. – Eur. J. 2010, 16, 4394–4401. 10.1002/chem.200903017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Ketterer N. A.; Ziller J. W.; Rheingold A. L.; Heyduk A. F. Imido and Organometallic-Amido Titanium(IV) Complexes of a Chelating Phenanthrenediamide Ligand. Organometallics 2007, 26, 5330–5338. 10.1021/om0701219. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Spaniel T.; Görls H.; Scholz J. (1,4-Diaza-1,3-diene)titanium and -niobium Halides: Unusual Structures with Intramolecular C-H···Halogen Hydrogen Bonds. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1998, 37, 1862–1865. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Janes T.; Xu M.; Song D. Synthesis and reactivity of Li and TaMe3 complexes supported by N,N′-bis(2,6-diisopropylphenyl)-o-phenylenediamido ligands. Dalton Trans. 2016, 45, 10672–10680. 10.1039/C6DT01908K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For more information see Supporting Information, Section 1: “Effective Oxidation State (EOS) Analysis”

- Ramos-Cordoba E.; Postils V.; Salvador P. Oxidation States from Wave Function Analysis. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2015, 11, 1501–1508. 10.1021/ct501088v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvador P.; Ramos-Cordoba E.; Gimferrer M.. APOST-3D; Institute of Computational Chemistry and Catalysis, University of Girona: Girona, 2019.

- a Seaburg J. K.; Fischer P. J.; Young V. G. Jr.; Ellis J. E. First Isolation and Structural Characterization of Bis(Anthracene)Metal Complexes: [Ti(η6-C14H10)(η4-C14H10)(η2-dmpe)] and [Ti(η4-C14H10)(η2-C14H10)(η5-C5Me5)]−. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1998, 37, 155–158. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Ellis J. E.; Blackburn D. W.; Yuen P.; Jang M. Highly reduced organometallics. Synthesis and chemistry of the first isolable bis(naphthalene)titanium complexes. Structural characterization of [Ti(η4-C10H8)2(SnMe3)2]2–. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993, 115, 11616–11617. 10.1021/ja00077a078. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morozov A. G.; Fedushkina I. L.; Irranb E.; Grohmann A. Titanium(IV) complexes supported by a dianionic acenaphthenediimine ligand: X-ray and spectroscopic studies of the metal coordination sphere. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2018, 95, 50–55. 10.1016/j.inoche.2018.07.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Álvarez-Ruiz E.; Carbó J. J.; Gómez M.; Hernández-Prieto C.; Hernán-Gómez A.; Martín A.; Mena M.; Ricart J. M.; Salom-Català A.; Santamaría C. N=N Bond Cleavage by Tantalum Hydride Complexes: Mechanistic Insights and Reactivity. Inorg. Chem. 2022, 61, 474–485. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.1c03152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Shima T.; Hou Z. Dinitrogen Fixation by Transition Metal Hydride Complexes. Top. Organomet. Chem. 2017, 60, 23–44. 10.1007/3418_2016_3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- For more information see Supporting Information, Section 4 “Monitoring of H2 Evolution Over Time”

- Basuli F.; Bailey B. C.; Watson L. A.; Tomaszewski J.; Huffman J. C.; Mindiola D. J. Four-Coordinate Titanium Alkylidene Complexes: Synthesis, Reactivity, and Kinetic Studies Involving the Terminal Neopentylidene Functionality. Organometallics 2005, 24, 1886–1906. 10.1021/om049400b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Compound 9 shows two independent crystallographic molecules

- a De Lucio A. J. C.; Cai I. C.; Witzke R. J.; Desnoyer A. N.; Tilley T. D. Synthesis, Characterization, and Reactivity of Low-Coordinate Titanium(III) Amido Complexes. Organometallics 2022, 41, 1434–1444. 10.1021/acs.organomet.2c00162. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Boynton J. N.; Guo J. D.; Grandjean F.; Fettinger J. C.; Nagase S.; Long G. J.; Power P. P. Synthesis and Characterization of the Titanium Bisamide Ti{N(H)AriPr6}2 (AriPr6 = C6H3-2,6-(C6H2 2,4,6-IPr3)2 and Its TiCl{N(H)Ari Pr6}2 Precursor: Ti(II) → Ti(IV) Cyclization. Inorg. Chem. 2013, 52, 14216–14223. 10.1021/ic4021355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Johnson A. R.; Davis W. M.; Cummins C. C. Titanium Complexes Stabilized by N-(Tert-Hydrocarbyl)Anilide Ligation: A Synthetic Investigation. Organometallics 1996, 15, 3825–3835. 10.1021/om960315g. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Wanandi P. W.; Davis W. M.; Cummins C. C.; Russell M. A.; Wilcox D. E. Radical Synthesis of a Heterobinuclear μ-Oxo Complex: Reaction of V(O)(O-i-Pr)3 with Ti(NRAr)3 (R = C(CD3)2CH3, Ar = 3, 5-C6H3Me2). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995, 117, 2110–2111. 10.1021/ja00112a032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Stennett C. R.; Fettinger J. C.; Power P. P. Unexpected Coordination Complexes of the Metal Tris-silylamides M{N(SiMe3)2}3 (M = Ti, V). Inorg. Chem. 2020, 59, 1871–1882. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.9b03084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Putzer M. A.; Magull J.; Goesmann H.; Neumüller B.; Dehnicke K. Synthese, Eigenschaften Und Kristallstrukturen Der Titan(III)-Amido-Komplexe Ti[N(SiMe3)2], [TiCl2 {N(SiMe3)2}(THF)2] Und [Na(12-Krone-4)2][TiCl2{N(SiMe3)2}2]. Chem. Ber. 1996, 129, 1401–1405. 10.1002/cber.19961291115. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Deacy A. C.; Phanopoulos A.; Lindeboom W.; Buchard A.; Williams C. K. Insights into the Mechanism of Carbon Dioxide and Propylene Oxide Ring-Opening Copolymerization Using a Co(III)/K(I) Heterodinuclear Catalyst. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 17929–17938. 10.1021/jacs.2c06921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Deacy A. C.; Moreby E.; Phanopoulos A.; Williams C. K. Co(III)/alkali- metal(I) heterodinuclear catalysts for the ring-opening polymerization of CO2 and propylene oxide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 19150–19160. 10.1021/jacs.0c07980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Cohen C. T.; Chu T.; Coates G. W. Cobalt Catalysts for the Alternating Copolymerization of Propylene Oxide and Carbon Dioxide: Combining High Activity and Selectivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 10869–10878. 10.1021/ja051744l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Lu X. -B.; Wang Y. Highly Active, Binary Catalyst Systems for the Alternating Copolymerization of CO2 and Epoxides under Mild Conditions. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2004, 43, 3574–3577. 10.1002/anie.200453998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For more information see Supporting Information, Section 5 “GPC and MALDI-ToF Analysis of Poly(Cyclohexene Carbonate)”

- Raman S. K.; Deacy A. C.; Carrodeguas L. P.; Reis N. V.; Kerr R. W. F.; Phanopoulos A.; Morton S.; Davidson M. G.; Williams C. K. Ti(IV)–Tris(phenolate) Catalyst Systems for the Ring-Opening Copolymerization of Cyclohexene Oxide and Carbon Dioxide. Organometallics 2020, 39, 1619–1627. 10.1021/acs.organomet.9b00845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Meerendonk W. J.; Duchateau R.; Koning C. E.; Gruter G. -J M. Unexpected Side Reactions and Chain Transfer for Zinc-Catalyzed Copolymerization of Cyclohexene Oxide and Carbon Dioxide. Macromolecules 2005, 38, 7306–7313. 10.1021/ma050797k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hessevik J.; Lalrempuia R.; Nsiri H.; Törnroos K. W.; Jensen V. R.; Le Roux E. Sterically (un)encumbered mer-tridentate N-heterocyclic carbene complexes of titanium(IV) for the copolymerization of cyclohexene oxide with CO2. Dalton Trans. 2016, 45, 14734–14744. 10.1039/C6DT01706A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veronese L.; Brivio M.; Biagini P.; Po R.; Tritto I.; Losio S.; Boggioni L. Effect of Quaternary Phosphonium Salts as Cocatalysts on Epoxide/CO2 Copolymerization Catalyzed by salen-Type Cr(III) Complexes. Organometallics 2020, 39, 2653–2664. 10.1021/acs.organomet.0c00269. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Manzer L. E.Inorganic Syntheses; Wiley, 1982; Vol. 21, pp 135–140. [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai H.; Sugitani K.; Moriuchi T.; Hirao T. Synthesis and oxidation of (benzimidazolylidene)Cr(CO)5 complexes. J. Organomet. Chem. 2005, 690, 1750–1755. 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2005.01.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wenderski T.; Light K. M.; Ogrin D.; Bott S. G.; Harlan C. J. Pd catalyzed coupling of 1,2-dibromoarenes and anilines: formation of N,N-diaryl-o-phenylenediamines. Tetrahedron Lett. 2004, 45, 6851–6853. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2004.07.116. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldrick G. M. SHELXT – Integrated space-group and crystal-structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. 2015, A71, 3–8. 10.1107/S2053273314026370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolomanov O. V.; Bourhis L. J.; Gildea R. J.; Howard J. A. K.; Puschmann H. OLEX2: a complete structure solution, refinement and analysis program. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2009, 42, 339–341. 10.1107/S0021889808042726. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldrick G. M. Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL. Acta Crystallogr. 2015, C71, 3–8. 10.1107/S2053229614024218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisch M. J.; Trucks G. W.; Schlegel H. B.; Scuseria G. E.; Robb M. A.; Cheeseman J. R.; Scalmani G.; Barone V.; Petersson G. A.; Nakatsuji H.; Li X.; Caricato M.; Marenich A. V.; Bloino J.; Janesko B. G.; Gomperts R.; Mennucci B.; Hratchian H. P.; Ortiz J. V.; Izmaylov A. F.; Sonnenberg J. L.; Williams-Young D.; Ding F.; Lipparini F.; Egidi F.; Goings J.; Peng B.; Petrone A.; Henderson T.; Ranasinghe D.; Zakrzewski V. G.; Gao J.; Rega N.; Zheng G.; Liang W.; Hada M.; Ehara M.; Toyota K.; Fukuda R.; Hasegawa J.; Ishida M.; Nakajima T.; Honda Y.; Kitao O.; Nakai H.; Vreven T.; Throssell K.; Montgomery J. A. Jr.; Peralta J. E.; Ogliaro F.; Bearpark M. J.; Heyd J. J.; Brothers E. N.; Kudin K. N.; Staroverov V. N.; Keith T. A.; Kobayashi R.; Normand J.; Raghavachari K.; Rendell A. P.; Burant J. C.; Iyengar S. S.; Tomasi J.; Cossi M.; Millam J. M.; Klene M.; Adamo C.; Cammi R.; Ochterski J. W.; Martin R. L.; Morokuma K.; Farkas O.; Foresman J. B.; Fox D. J.. Gaussian 16, Revision A.03; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, 2016.

- Grimme S.; Antony J.; Ehrlich S.; Krieg H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 2010, 132, 154104 10.1063/1.3382344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]