Abstract

Introduction

The actual rate of conversion surgery and its prognostic advantages remain unclear. This study aimed to assess the outcomes of salvage surgery after conversion therapy with triple therapy (transcatheter arterial chemoembolization [TACE] combined with lenvatinib plus anti-PD-1 antibodies) in patients with initially unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (uHCC).

Methods

Patients with initially uHCC who received at least one cycle of first-line triple therapy and salvage surgery at five major cancer centers in China were included. The primary endpoints were overall survival (OS) and recurrence-free survival (RFS) rates after salvage surgery. The secondary endpoints were perioperative complications, 90-day mortality, and pathological tumor response.

Results

Between June 2018 and December 2021, 70 patients diagnosed with uHCC who underwent triple therapy and salvage surgery were analyzed: 39 with Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) stage C, 22 with BCLC stage B, and 9 with BCLC stage A disease. The median interval between the start of triple therapy and salvage surgery was 4.3 months (range, 1.7–14.2 months). Pathological complete response and major pathological response were observed in 29 (41.4%) and 59 (84.3%) patients, respectively. There were 2 cases of perioperative mortality (4.3%) and 5 cases of severe perioperative complications (7.1%). With a median follow-up of 12.9 months after surgery (range, 0.3–36.8 months), the median OS and RFS were not reached. The 1- and 2-year OS rates were 97.1% and 94.4%, respectively, and the corresponding RFS rates were 68.9% and 54.4%, respectively.

Conclusion

First-line combination of TACE, lenvatinib, and anti-PD-1 antibodies provides a better chance of conversion therapy in patients with initially uHCC. Furthermore, salvage surgery after conversion therapy is effective and safe and has the potential to provide excellent long-term survival benefits.

Keywords: Hepatocellular carcinoma, Conversion therapy, Salvage surgery, Systemic treatment, Transcatheter arterial chemoembolization

Introduction

Liver resection is one of the most important curative treatments for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [1, 2, 3, 4]. However, only a small number of patients have the opportunity to undergo surgery. More than 70% of HCC patients have already lost the opportunity for surgery when diagnosed and receive palliative treatment [3, 4, 5, 6]. Fortunately, the rapid development of systemic therapy has dramatically changed the treatment of unresectable HCC (uHCC) [7, 8, 9]. An increasing number of systemic treatment methods have been applied in the clinic, and acceptable therapeutic outcomes have been achieved [10, 11, 12, 13, 14]. Furthermore, some studies have reported that patients with advanced HCC or initially uHCC received salvage surgery after conversion therapy [7, 15, 16, 17].

In the past, most conversion therapies were local therapy (transcatheter arterial chemoembolization [TACE], hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy, and stereotactic body radiation therapy), and the convert resection rate was only 9.5–16.9% [7, 18]. With the development of systemic therapy, the convert resection rate increased to 15.9–30.6% [7, 18, 19]. More surprisingly, previous studies have reported that combined local and systemic therapy represents a promising strategy for better tumor response and a higher surgical conversion rate with different mechanisms of action [20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27]. In our previous study [24], TACE combined with lenvatinib plus anti-PD-1 antibodies (triple therapy) presented satisfactory results for uHCC, with an objective response rate of 77.4% and a convert resection rate of 46.8%. Similar outcomes of triple therapy have been reported in other studies [23]. However, only few studies have reported successful conversion to surgery, and knowledge about the safety and prognostic advantages of salvage surgery after conversion therapy are limited. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the safety and clinical efficacy of salvage surgery after conversion therapy in patients with initially uHCC. To the best of our knowledge, this study represents the largest case series on salvage surgery after conversion therapy with local and systemic therapy.

Materials and Methods

Patients

This retrospective study included consecutive patients with initially uHCC who received at least one cycle of triple therapy (TACE + lenvatinib + anti-PD-1 antibodies) and salvage surgery at five major cancer centers in China between June 2018 and December 2021 (the Fujian Provincial Hospital, First Affiliated Hospital of Fujian Medical University, First Affiliated Hospital of Xiamen University, Zhongshan Hospital of Xiamen University, and Zhangzhou Affiliated Hospital of Fujian Medical University). Baseline data, including demographic, clinical, and pathological characteristics and treatment-related outcomes, were retrospectively collected. In accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, this study was approved by the Ethics Committee of each institution, and written informed consent was obtained from all patients or their legal guardians.

HCC was diagnosed using histological examination or clinicoradiological criteria, according to the guidelines proposed by the China Liver Cancer Staging system [4]. Patients were considered unresectable if they had extensive bilobar involvement of the liver and the lesions could not be radically resected, extrahepatic lesions, insufficient hepatic functional reserve, or a future liver remnant volume/standard liver volume ratio of <40% in patients with liver cirrhosis and <30% in patients without liver cirrhosis.

Conversion to resectable HCC was defined as follows: (1) R0 resection with preservation of a sufficient remnant liver volume and function is achievable; (2) Child-Pugh class A; (3) Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0–1; (4) no extrahepatic lesions; and (5) no contraindications for hepatectomy.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) initially uHCC patients treated with triple therapy (TACE + lenvatinib + anti-PD-1 antibodies) as the first-line treatment and salvage surgery and (2) age between 18 and 75 years. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) prior treatment with liver resection, radiofrequency ablation, TACE, or systemic therapy; (2) combined with other anticancer treatments, such as hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy, radiofrequency ablation, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy; (3) a history of other cancers; and (4) incomplete data.

Triple Therapy Procedure

The triple therapy method has been described in detail previously [24]. Briefly, all patients received lenvatinib (8 mg for patients with body weight <60 kg or 12 mg for patients with body weight ≥60 kg) orally once daily and anti-PD-1 antibodies (camrelizumab 200 mg, sintilimab 200 mg, tislelizumab 200 mg, toripalimab 240 mg, penpulimab 200 mg, or pembrolizumab 200 mg) intravenously once every 3 weeks. Super-selective TACE was performed under local anesthesia via the right femoral artery. Common hepatic or celiac arteriography was performed to discern the number and location of lesions, tumor size, feeding artery, and presence of anatomic variations. After the artery supplying the tumor was identified, iodized oil (less than 20 mL) and pirarubicin were mixed and injected into the super-selective tumor artery via a microcatheter. TACE was performed without iodized oil in the presence of an arterioportal shunt to prevent severe damage to normal liver parenchyma. Subsequently, the feeding arteries were selectively embolized using gelatin sponge particles until complete arterial flow stasis was observed. TACE was repeated every 4–6 weeks if there was an obvious hepatic arterial blood supply to the tumor based on contrast-enhanced abdominal CT and/or MRI. All patients with active hepatitis B virus infection received oral antiviral treatment (entecavir or tenofovir).

Patients were followed up every 4–8 weeks during triple therapy. At each appointment, patients were evaluated using clinical, laboratory, and radiological (contrast-enhanced CT and/or MRI) data for liver function, treatment-related adverse events, tumor response, and resectability. Tumor response was assessed according to the modified Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (mRECIST) [28].

Surgical Procedure

When the patient met the criteria of conversion to resectable HCC, curative intent resection was performed after obtaining informed consent. Lenvatinib and anti-PD-1 antibodies were stopped for 1 week and 1 month before resection, respectively.

The type and extent of liver resection in each patient were determined based on tumor location, number of nodules, tumor size, degree of cirrhosis, patient performance, and hepatic functional reserve. Anatomical resection was generally preferred over non-anatomical resection. Liver resection was classified as minor (fewer than three anatomical segments) or major (three or more anatomical segments) according to Couinaud's classification [29].

Postoperative complications were classified according to the Clavien-Dindo classification [30]. Posthepatectomy liver failure (PHLF) was defined and graded according to the criteria established by the International Study Group of Liver Surgery [31]. A standard 7-point baseline sample collection protocol was applied for the resected tumor specimen [4, 32]. Additional histological sections were obtained for suspected activated tumor lesions and tumor thrombi. Pathological complete response (PCR) and major pathological response (MPR) were defined as the complete absence and ≤10% of viable tumor cells in the resected tumor specimen, respectively. Based on the liver function, treatment-related adverse reactions, and patient performance, postoperative adjuvant systemic therapy (lenvatinib plus anti-PD-1 antibodies) was recommended for 3–6 months (3 months for patients who achieved PCR and 6 months for others).

Follow-Up

All patients were required to undergo contrast-enhanced abdominal CT or MRI, chest radiography, clinical assessment, and laboratory tests 1 month after surgery and every 3–6 months thereafter. When recurrence was diagnosed, treatments including radiofrequency ablation, re-resection, TACE, radiotherapy, or systemic therapy were initiated after recommendations by a multidisciplinary tumor board, based on the characteristics of the recurrent tumor, liver function, and patient performance.

Study Endpoints

The primary endpoints of this study were the overall survival (OS) and recurrence-free survival (RFS) rates after salvage surgery. OS was defined as the period from the date of surgery after triple therapy to the date of death or last follow-up. RFS was defined as the interval between the date of surgery after triple therapy and the date of HCC recurrence or the last follow-up. Data were right-censored at the last follow-up for living patients with no evidence of recurrence or death. The secondary endpoints were perioperative complications, 90-day mortality, and pathological tumor response. The last date of follow-up was June 1, 2022.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous data are presented as mean and standard deviation or as median and range, and categorical data are presented as number and percentage. OS and RFS were calculated using Kaplan-Meier curves. The risk factors for RFS were identified using univariate and multivariate analysis. Factors with p values <0.1 in the univariate analysis were entered into a multivariate Cox proportional hazards model using the forward selection method. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. All statistical analysis was performed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences software (version 24, IBM, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Baseline Characteristics

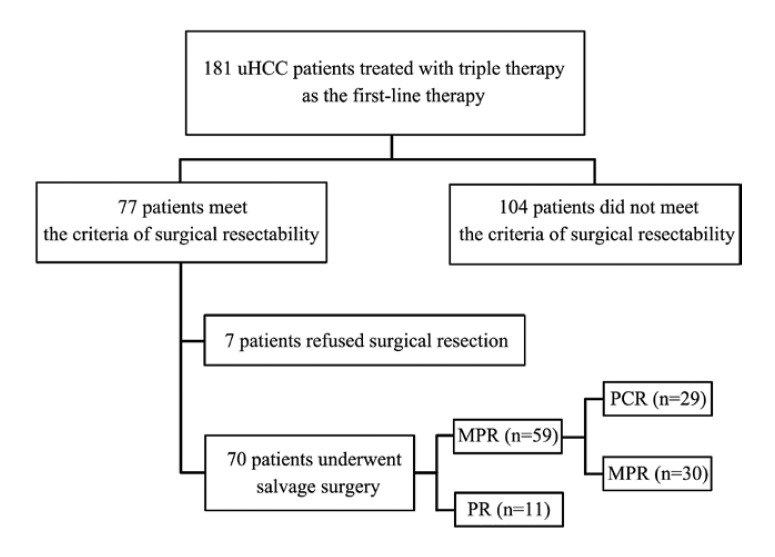

Between June 2018 and December 2021, 181 patients with uHCC who received triple therapy as conversion therapy at five major cancer centers in China were enrolled, including 17 patients with Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) stage A, 46 patients with BCLC stage B, and 118 patients with BCLC stage C; The median patient age was 57 years (range, 23–75 years), and 161 patients were males. A total of 164 patients had hepatitis B virus infection, and 104 had macrovascular invasion. The baseline characteristics of the entire study population are summarized in online supplementary Table 1 (for all online suppl. material, see www.karger.com/doi/10.1159/000528356). A total of 77 patients reached the standard of conversion to resectable HCC; of them, 7 refused surgical resection and continued triple therapy and 70 underwent salvage surgery (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of patient selection.

Of the 70 patients who underwent salvage surgery, 9, 22, and 39 had BCLC stage A, B, and C disease, respectively. Sixty-one patients (87.1%) were men and 9 (12.9%) were women; the median age was 54 years (range, 23–75 years). Seven patients (10%) had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 1, and 61 patients (91.4%) had hepatitis B infection. Macrovascular invasion was detected in 39 patients (55.7%), and 47 patients (67.1%) had multiple tumors. The mean maximum tumor diameter was 10.5 ± 4.85 cm (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of patients who underwent salvage surgery

| Characteristic | Patients (n = 70) |

|---|---|

| Median age (range), years | 54 (23–75) |

| Age, mean years ± SD | 53.8±11.4 |

| Age, n (%) | |

| <65 years | 60 (85.7) |

| ≥65 years | 10 (14.3) |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Female | 9 (12.9) |

| Male | 61 (87.1) |

| ECOG-PS, n (%) | |

| 0 | 63 (90) |

| 1 | 7 (10) |

| Hepatitis B infection, n (%) | |

| Yes | 64 (91.4) |

| No | 6 (8.6) |

| Pre-treatment AFP, n (%) | |

| <400 ng/mL | 30 (42.9) |

| ≥400 ng/mL | 40 (57.1) |

| Pre-treatment PIVKA-II, n (%) | |

| <400 mAU/mL | 12 (17.1) |

| ≥400 mAU/mL | 58 (82.9) |

| Number of tumors, n (%) | |

| Single | 23 (32.9) |

| Multiple | 47 (67.1) |

| Maximum tumor size, cm | 10.5±4.85 |

| Maximum tumor size, n (%) | |

| <10 cm | 30 (42.9) |

| ≥10 cm | 40 (57.1) |

| Macrovascular invasion, n (%) | 39 (55.7) |

| BCLC staging, n (%) | |

| A | 9 (12.9) |

| B | 22 (31.4) |

| C | 39 (55.7) |

| CNLC staging, n (%) | |

| Ib | 9 (12.9) |

| IIa | 9 (12.9) |

| IIb | 13 (18.6) |

| IIIa | 39 (55.7) |

SD, standard deviations; ECOG-PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; AFP, alpha fetoprotein; PIVKA-II, protein induced by vitamin K absence-II; BCLC, Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer; CNLC, China Liver Cancer.

Triple Therapy Procedure

All patients received at least one cycle of first-line triple therapy. The median number of anti-PD-1 antibodies and TACE were 4 cycles (range, 1–9 cycles) and 2 times (range, 1–7 times), respectively. The anti-PD-1 antibodies included camrelizumab (200 mg, n = 24), sintilimab (200 mg, n = 22), tislelizumab (200 mg, n = 11), toripalimab (240 mg, n = 8), penpulimab (200 mg, n = 3), and pembrolizumab (200 mg, n = 2). After conversion therapy, 34 patients achieved complete response and 36 achieved partial response according to the mRECIST.

Salvage Surgery and Perioperative Conditions

The median interval between the start of triple therapy and salvage surgery was 4.3 months (range, 1.7–14.2 months). Nine patients underwent laparoscopic surgery, and the remaining 61 patients (87.1%) underwent open surgery. Fifty-one patients (72.9%) underwent major hepatectomy. The median surgery time was 205 min (range, 90–340 min), and the median blood loss volume was 300 mL (range, 100–6,000 mL). Twenty-four patients (34.3%) underwent blood transfusion. PCR and MPR were achieved in 29 (41.4%) and 59 (84.3%) patients, respectively. The median postoperative hospital stay was 10 days (range, 5–28 days). Five patients (7.1%) experienced Clavien-Dindo grade IIIb or higher complications, including pulmonary embolism (n = 1) and PHLF (n = 4). The prevalence of PHLF was 22.9%, with 12, 2, and 2 patients experiencing grade A, grade B, and grade C PHLF, respectively (Table 2). The 90-day mortality rate was 2.9% (2/70). Both patients underwent right hemihepatectomy for HCC with tumor thrombus in the right branch of the portal vein but unfortunately died of PHLF 9 days and 3 months after surgery, respectively.

Table 2.

Perioperative outcomes

| Characteristic | Patients (n = 70) |

|---|---|

| Surgical type, n (%) | |

| Laparoscopic | 9 (12.9) |

| Open | 61 (87.1) |

| Major hepatectomy, n (%) | 51 (72.9) |

| Operative time, min (range) | 205 (90–340) |

| Blood loss, mL (range) | 300 (100–6,000) |

| Blood loss, n (%) | |

| <500 mL | 43 (61.4) |

| ≥500 mL | 27 (38.6) |

| Blood transfusion, n (%) | |

| Yes | 24 (34.3) |

| No | 46 (65.7) |

| Pathological reaction, n (%) | |

| PCR | 29 (41.4) |

| MPR | 59 (84.3) |

| Microvascular invasion, n (%) | |

| M0 | 50 (71.4) |

| M1 | 13 (18.6) |

| M2 | 7 (10) |

| Clavien-Dindo classification, n (%) | |

| 0–IIIa | 65 (92.9) |

| IIIb-V | 5 (7.1) |

| Post-hepatectomy liver failure, n (%) | 16 (22.9) |

| Post-hepatectomy liver failure, n (0/A/B/C) | 54/12/2/2 |

| Postoperative hospital stay, days (range) | 10 (5–28) |

PCR, pathological complete response; MPR, major pathological response.

Follow-Up

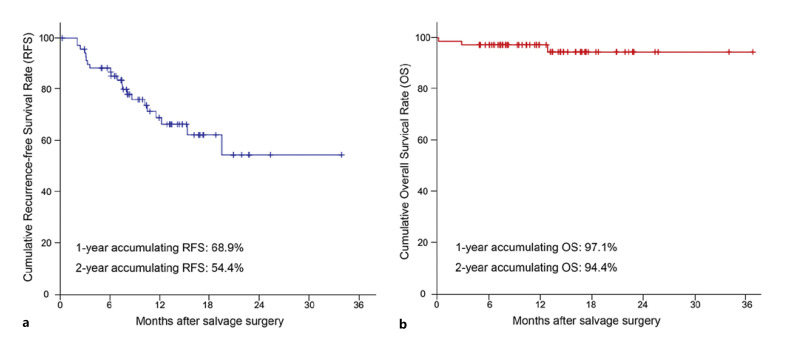

The cutoff date for the present analysis was June 1, 2022. All the patients were followed up until the cutoff date or death. The median postoperative duration of adjuvant systemic treatment (lenvatinib plus anti-PD-1 antibodies) was 6.2 months (range, 0–13.8 months). At a median follow-up of 12.9 months (range, 0.3–36.8 months), the median OS and RFS were not reached. The 1- and 2-year OS rates were 97.1% and 94.4%, respectively, and the corresponding RFS rates were 68.9% and 54.4%, respectively (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of recurrence-free survival (a) and overall survival (b).

Tumor recurrence was detected in 21 patients. Subsequent treatments for recurrence were initiated following the recommendations of a multidisciplinary tumor board, including repeat hepatectomy, radiofrequency ablation, radiotherapy, and second-line systemic therapy (Table 3). In addition to the two patients who died within 90 days after surgery, one patient died of gastroesophageal variceal bleeding due to portal hypertension without evidence of recurrence 13.1 months after salvage surgery.

Table 3.

Patterns of tumor recurrence

| Patients (n = 70) | |

|---|---|

| Number of patients with HCC recurrence, n (%) | 21 (30) |

| Site of recurrence, n (%) | |

| Intrahepatic recurrence | 16 (76.2) |

| Extrahepatic recurrence | 3 (14.3) |

| Both intra- and extrahepatic recurrence | 2 (9.5) |

| Time until recurrence, n | |

| <1 year | 19 |

| ≥1 year | 2 |

| Major treatment for tumor recurrence, n | |

| Repeat hepatectomy | 3 |

| Radiofrequency ablation | 4 |

| Radiotherapy | 7 |

| Second-line systemic therapy | 2 |

| Systemic therapy + TACE | 2 |

| None | 3 |

HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; TACE, transcatheter arterial chemoembolization.

Risk Factor Analysis for RFS

Univariate and multivariate analysis indicated that a high count of white blood cells (hazard ratio [HR], 0.029; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.006–0.136; p < 0.001), a high hemoglobin level (HR, 0.060; 95% CI: 0.011–0.330; p = 0.001), a single tumor (HR, 0.140; 95% CI: 0.041–0.483; p = 0.002), and PCR (HR, 0.113; 95% CI: 0.031–0.409; p = 0.001) were beneficial factors for RFS. Complications classified as IIIb-V on the Clavien-Dindo classification (HR, 14.535; 95% CI: 3.210–65.824; p = 0.001) were identified as risk factors for RFS (Table 4).

Table 4.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of factors related to the RFS

| Variables | Univariate analysis |

Multivariate analysis |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | (95% CI) | p value | HR | (95% CI) | p value | |

| Sex (male) | 1.231 | 0.531–1.827 | 0.690 | |||

| Age (≥65 years) | 0.934 | 0.274–3.182 | 0.914 | |||

| ECOG-PS (1) | 1.773 | 0.520–6.047 | 0.360 | |||

| Hepatitis B infection (positive) | 1.198 | 0.278–5.154 | 0.809 | |||

| WBC count (≥4 × 109/L) | 0.213 | 0.070–0.647 | 0.006 | 0.029 | 0.006–0.136 | <0.001 |

| Hemoglobin level (≥100 g/L) | 0.167 | 0.038–0.745 | 0.019 | 0.060 | 0.011–0.330 | 0.001 |

| PLT count (≥100 × 109/L) | 0.733 | 0.169–3.175 | 0.678 | |||

| Total bilirubin level (≥34 µmol/L) | 1.173 | 0.155–8.864 | 0.877 | |||

| Albumin level (≥35 g/L) | 0.692 | 0.203–2.362 | 0.556 | |||

| ALT level (≥40 IU/L) | 1.162 | 0.492–2.743 | 0.732 | |||

| AST level (≥40 IU/L) | 1.272 | 0.535–3.023 | 0.587 | |||

| Pre-treatment AFP level (≥400 ng/mL) | 1.551 | 0.641–3.754 | 0.330 | |||

| Pre-treatment PIVKA-II (≥400 mAU/mL) | 3.056 | 0.707–13.203 | 0.135 | |||

| Tumor number (single) | 0.330 | 0.110–0.992 | 0.048 | 0.140 | 0.041–0.483 | 0.002 |

| Maximum tumor size (≥10 cm) | 0.710 | 0.301–1.674 | 0.434 | |||

| Macrovascular invasion (positive) | 0.520 | 0.218–1.242 | 0.141 | |||

| Surgical type (laparoscopic) | 0.942 | 0.275–3.223 | 0.924 | |||

| Major hepatectomy (yes) | 0.766 | 0.308–1.904 | 0.567 | |||

| Operative time (≥180 min) | 1.173 | 0.449–3.063 | 0.745 | |||

| Blood loss (≥500 mL) | 0.938 | 0.386–2.279 | 0.887 | |||

| Blood transfusion (yes) | 0.918 | 0.370–2.280 | 0.854 | |||

| Clavien-Dindo classification (IIIb–V) | 6.723 | 1.891–23.901 | 0.003 | 14.535 | 3.210–65.824 | 0.001 |

| Pathological reaction (PCR) | 0.333 | 0.121–0.915 | 0.033 | 0.113 | 0.031–0.409 | 0.001 |

| Microvascular invasion (M0) | 0.629 | 0.253–1.564 | 0.318 | |||

RFS, recurrence-free survival; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; ECOG-PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; WBC, white blood cells; PLT, platelet; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate transaminase; AFP, alpha fetoprotein; PIVKA-II, protein induced by vitamin K absence-II; PCR, pathological complete response; bold, p < 0.05.

Conclusion

The prognosis of patients with uHCC is poor, and the median survival is less than 1 year [1, 2, 3, 4]. Fortunately, significant progress has been made in the development of systemic therapy for the treatment of HCC, and an increasing number of studies have reported the possibility of conversion to resectable HCC in the past 5 years [7, 18, 19]. Furthermore, systemic therapy combined with TACE has a synergistic effect in increasing the rate of tumor response and conversion to resection [23]. In this study, the true rate of convert resection with triple therapy was 38.7% (70/181). A total of 70 patients received salvage surgery with acceptable surgical complications. PCR and MPR were observed in 29 and 59 patients, respectively. The 90-day mortality rate was 2.9%. With a median follow-up of 12.9 months after surgery (range, 0.3–36.8 months), the median OS and RFS were not reached. The 1- and 2-year OS rates were 97.1% and 94.4%, respectively, and the corresponding RFS rates were 68.9% and 54.4%, respectively. Therefore, the combination of TACE, lenvatinib, and anti-PD-1 antibodies provides a good chance of conversion therapy in patients diagnosed with uHCC.

Only few studies have reported the safety of conversion surgery for HCC. In our study, PHLF was identified in 16 of 70 patients (22.9%), and it was the most common severe complication (grade IIIb or higher). Furthermore, two patients who underwent salvage right hemihepatectomy for advanced HCC with portal vein tumor thrombus died in the perioperative period due to PHLF. Although the incidence of PHLF was significantly higher than that reported previously (approximately 10%) [31], most of PHLF is grade A/B PHLF, which are manageable without invasive treatment, and the incidence of grade C PHLF is only 2.9%, which is tolerable. In our study, most of the patients underwent major hepatectomy (72.9%) with a high tumor burden and/or extensive tumor involvement. Moreover, patients always are in a relatively poor liver function reserve or general condition due to the superimposed hepatotoxic side effects of comprehensive treatment. The above conditions might contribute to the high incidence of PHLF in the conversion therapy. PHLF is the major source of morbidity and mortality after surgery, and clinicians should pay more attention to this when conversion surgery is performed.

In our study, three patients died during follow-up: two in the perioperative period and one 13.1 months after salvage surgery due to gastroesophageal variceal bleeding caused by portal hypertension. No patients died of tumor recurrence. Although salvage surgery improves OS in patients with uHCC, the high rate of postoperative recurrence, especially intrahepatic recurrence, remains a critical problem. Overall, 19 patients (27.1%) showed relapse within 1 year after surgery. Aggressive treatment, including repeat hepatectomy, radiofrequency ablation, and radiotherapy, could improve the prognosis of selected patients with local recurrence. Although postoperative recurrence affects prognosis, the tumor burden is significantly lower than that before conversion, and the treatment is simpler. Careful preoperative imaging evaluation, regular postoperative follow-up, and aggressive treatment are important for improving patient prognosis.

Although the efficacy of systemic treatment for patients with uHCC has been widely accepted, the median progression-free survival of first-line systemic treatments (such as atezolizumab and bevacizumab, durvalumab and tremelimumab, levatinib, and sorafenib) is less than 10 months [3, 10, 33, 34, 35]. In our study, 7 patients refused salvage surgery after successful conversion therapy, and 5 of them had progression (range, 5.7–12.6 m). Therefore, salvage surgery is an important means to achieve a long-term progression-free survival and OS. Additionally, salvage surgery is of great significance to reduce drug resistance and treatment-related adverse reactions. Whether salvage surgery is necessary when achieving clinical CR remains controversial. However, clinical CR does not represent PCR. In our study, five patients with clinical CR were pathologically confirmed to have partial response or MPR. The postoperative pathology can not only finally clarify the pathological tumor response, but also provide guidance for adjuvant treatment. In general, salvage surgery is essential to improve the long-term tumor-free survival and provide guidance for adjuvant treatment, but it still needs further exploration by prospective research.

This study has several limitations. This was a retrospective, single-arm study with a comparatively short follow-up time; however, it represents the largest reported case series on salvage surgery after conversion therapy with TACE and systemic treatment, and the prognostic advantage of salvage surgery after conversion therapy was clearly demonstrated. Additionally, patients in this study received various anti-PD-1 antibodies, different times of TACE, varied durations of adjuvant systemic treatment, which may influence the long-term effect of salvage surgery. Therefore, large-scale, well-designed randomized controlled trials are required to evaluate the efficacy and safety of salvage surgery after triple therapy in patients with uHCC. Finally, this study was conducted in China, which has a high incidence of HBV-related uHCC; therefore, whether the study results can be extrapolated to patients with uHCC due to other etiologies is unknown.

In conclusion, the first-line combination of TACE, lenvatinib, and anti-PD-1 antibodies provides a better chance of conversion therapy in patients with initially uHCC. Furthermore, salvage surgery after conversion therapy is effective and safe and has the potential to provide excellent long-term survival benefits.

Statement of Ethics

This study was conducted in accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki and with approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Fujian Provincial Hospital (approval number: K2018-12-042). All patients and their guardians provided written informed consent prior to enrolment.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Sources

This study was funded by the Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province (Grant No. 2020J011105, 2022J011021).

Author Contributions

Served as scientific advisors: Mao-Lin Yan and Bin Li. Critically reviewed the study proposal: Jia-Yi Wu, Zhi-Bo Zhang, Jian-Yin Zhou, and Mao-Ling Yan. Data acquisition: Jia-Yi Wu, Zhi-Bo Zhang, Jian-Yin Zhou, Jing-Peng Ke, Yan-Nan Bai, Yu-Feng Chen, Jun-Yi Wu, Song-Qiang Zhou, Shuang-Jia Wang, Zhen-Xin Zeng, Yi-Nan Li, and Fu-Nan Qiu. Data analysis: Jia-Yi Wu, Zhi-Bo Zhang, and Jian-Yin Zhou. Drafting the manuscript: Jia-Yi Wu, Zhi-Bo Zhang, Jian-Yin Zhou, Bin Li, and Mao-Lin Yan. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article and its online supplementary material files. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the staff of the participating hospitals for their efforts, as well as all of the patients for their participation.

Funding Statement

This study was funded by the Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province (Grant No. 2020J011105, 2022J011021).

References

- 1.Roayaie S, Jibara G, Tabrizian P, Park JW, Yang J, Yan L, et al. The role of hepatic resection in the treatment of hepatocellular cancer. Hepatology. 2015 Aug;62((2)):440–451. doi: 10.1002/hep.27745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.European Association for the Study of the Liver EASL clinical practice guidelines management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2018 Jul;69((1)):182–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reig M, Forner A, Rimola J, Ferrer-Fabrega J, Burrel M, Garcia-Criado A, et al. BCLC strategy for prognosis prediction and treatment recommendation the 2022 update. J Hepatol. 2022 Mar;76((3)):681–693. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2021.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhou J, Sun H, Wang Z, Cong W, Wang J, Zeng M, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma (2019 Edition) Liver Cancer. 2020 Dec;9((6)):682–720. doi: 10.1159/000509424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Villanueva A. Hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2019 Apr;380((15)):1450–1462. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1713263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018 GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018 Nov;68((6)):394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sun HC, Zhou J, Wang Z, Liu X, Xie Q, Jia W, et al. Chinese expert consensus on conversion therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma (2021 edition) Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr. 2022 Apr;11((2)):227–252. doi: 10.21037/hbsn-21-328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kudo M. Combination cancer immunotherapy in hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Cancer. 2018 Mar;7((1)):20–27. doi: 10.1159/000486487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luo XY, Wu KM, He XX. Advances in drug development for hepatocellular carcinoma clinical trials and potential therapeutic targets. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2021 May;40((1)):172. doi: 10.1186/s13046-021-01968-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Finn RS, Qin S, Ikeda M, Galle PR, Ducreux M, Kim TY, et al. Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2020 May;382((20)):1894–1905. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1915745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Finn RS, Ikeda M, Zhu AX, Sung MW, Baron AD, Kudo M, et al. Phase Ib study of lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2020 Sep;38((26)):2960–2970. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.00808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xu J, Shen J, Gu S, Zhang Y, Wu L, Wu J, et al. Camrelizumab in combination with apatinib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (RESCUE) a nonrandomized, open-label, phase II trial. Clin Cancer Res. 2021 Feb;27((4)):1003–1011. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-2571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yau T, Kang YK, Kim TY, El-Khoueiry AB, Santoro A, Sangro B, et al. Efficacy and safety of nivolumab plus ipilimumab in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma previously treated with sorafenib the checkmate 040 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2020 Nov;6((11)):e204564. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.4564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kelley RK, Sangro B, Harris W, Ikeda M, Okusaka T, Kang YK, et al. Safety and pharmacodynamics of tremelimumab plus durvalumab for patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma randomized expansion of a phase I/II study. J Clin Oncol. 2021 Sep;39((27)):2991–3001. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.03555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lau WY, Lai ECH. Salvage surgery following downstaging of unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma-a strategy to increase resectability. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007 Dec;14((12)):3301–3309. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9549-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sun HC, Zhu XD. Downstaging conversion therapy in patients with initially unresectable advanced hepatocellular carcinoma an overview. Front Oncol. 2021 Nov;11:772195. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.772195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen X, Lai L, Ye J, Li L. Downstaging therapies for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma prior to hepatic resection a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Oncol. 2021 Nov;11:740762. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.740762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tang H, Cao Y, Jian Y, Li X, Li J, Zhang W, et al. Conversion therapy with an immune checkpoint inhibitor and an antiangiogenic drug for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma a review. Biosci Trends. 2022 May;16((2)):130–141. doi: 10.5582/bst.2022.01019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhu XD, Huang C, Shen YH, Ji Y, Ge NL, Qu XD, et al. Downstaging and resection of initially unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma with tyrosine kinase inhibitor and anti-PD-1 antibody combinations. Liver Cancer. 2021 Jul;10((4)):320–329. doi: 10.1159/000514313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang F, Xu GL, Huang JT, Yin Y, Xiang W, Zhong BY, et al. Transarterial chemoembolization combined with immune checkpoint inhibitors and tyrosine kinase inhibitors for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma efficacy and systemic immune response. Front Immunol. 2022 Feb;13:847601. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.847601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hack SP, Zhu AX, Wang Y. Augmenting anticancer immunity through combined targeting of angiogenic and PD-1/PD-L1 pathways challenges and opportunities. Front Immunol. 2020 Nov;11:598877. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.598877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kudo M. A new treatment option for intermediate-stage hepatocellular carcinoma with high tumor burden initial lenvatinib therapy with subsequent selective TACE Liver Cancer. 2019 Oct;8((5)):299–311. doi: 10.1159/000502905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ke Q, Xin F, Fang H, Zeng Y, Wang L, Liu J. Corrigendum the significance of transarterial chemo(embolization) combined with tyrosine kinase inhibitors and immune check point inhibitors for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma in the era of systemic therapy: a systematic review. Front Immunol. 2022 May;13:952446. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.952446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu JY, Yin ZY, Bai YN, Chen YF, Zhou SQ, Wang SJ, et al. Lenvatinib combined with anti-PD-1 antibodies plus transcatheter arterial chemoembolization for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma a multicenter retrospective study. J Hepatocell Carcinoma. 2021 Oct;8:1233–1240. doi: 10.2147/JHC.S332420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen S, Wu Z, Shi F, Mai Q, Wang L, Wang F, et al. Lenvatinib plus TACE with or without pembrolizumab for the treatment of initially unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma harbouring PD-L1 expression a retrospective study. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2022 Aug;148((8)):2115–2125. doi: 10.1007/s00432-021-03767-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cai M, Huang W, Huang J, Shi W, Guo Y, Liang L, et al. Transarterial chemoembolization combined with lenvatinib plus PD-1 inhibitor for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma a retrospective cohort study. Front Immunol. 2022 Mar;13:848387. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.848387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cao F, Yang Y, Si T, Luo J, Zeng H, Zhang Z, et al. The efficacy of TACE combined with lenvatinib plus sintilimab in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma a multicenter retrospective study. Front Oncol. 2021 Dec;11:783480. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.783480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lencioni R, Llovet JM. Modified RECIST (mRECIST) assessment for hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Liver Dis. 2010 Feb;30((1)):52–60. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1247132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen K, Pan Y, Hu GY, Maher H, Zheng XY, Yan JF. Laparoscopic versus open major hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma a meta-analysis. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2018 Oct;28((5)):267–274. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0000000000000567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Clavien PA, Barkun J, de Oliveira ML, Vauthey JN, Dindo D, Schulick RD, et al. The clavien-dindo classification of surgical complications five-year experience. Ann Surg. 2009 Aug;250((2)):187–196. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181b13ca2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rahbari NN, Garden OJ, Padbury R, Brooke-Smith M, Crawford M, Adam R, et al. Posthepatectomy liver failure a definition and grading by the International Study Group of Liver Surgery (ISGLS) Surgery. 2011 May;149((5)):713–724. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2010.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cong WM, Bu H, Chen J, Dong H, Zhu YY, Feng LH, et al. Practice guidelines for the pathological diagnosis of primary liver cancer 2015 update. World J Gastroenterol. 2016 Nov;22((42)):9279–9287. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i42.9279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abou-Alfa GK, Chan SL, Kudo M, Lau G, Kelley RK, Furuse J, et al. Phase 3 randomized multicenter study of tremelimumab and durvalumab as first-line therapy in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (uHCC) HIMALAYA. J Clin Oncol. 2022;4((Suppl l)) abstr 379. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kudo M, Finn RS, Qin S, Han KH, Ikeda K, Piscaglia F, et al. Lenvatinib versus sorafenib in first-line treatment of patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma a randomised phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2018 Mar;391((10126)):1163–1173. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30207-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, Hilgard P, Gane E, Blanc JF, et al. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2008 Jul;359((4)):378–390. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0708857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary data

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article and its online supplementary material files. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.