Abstract

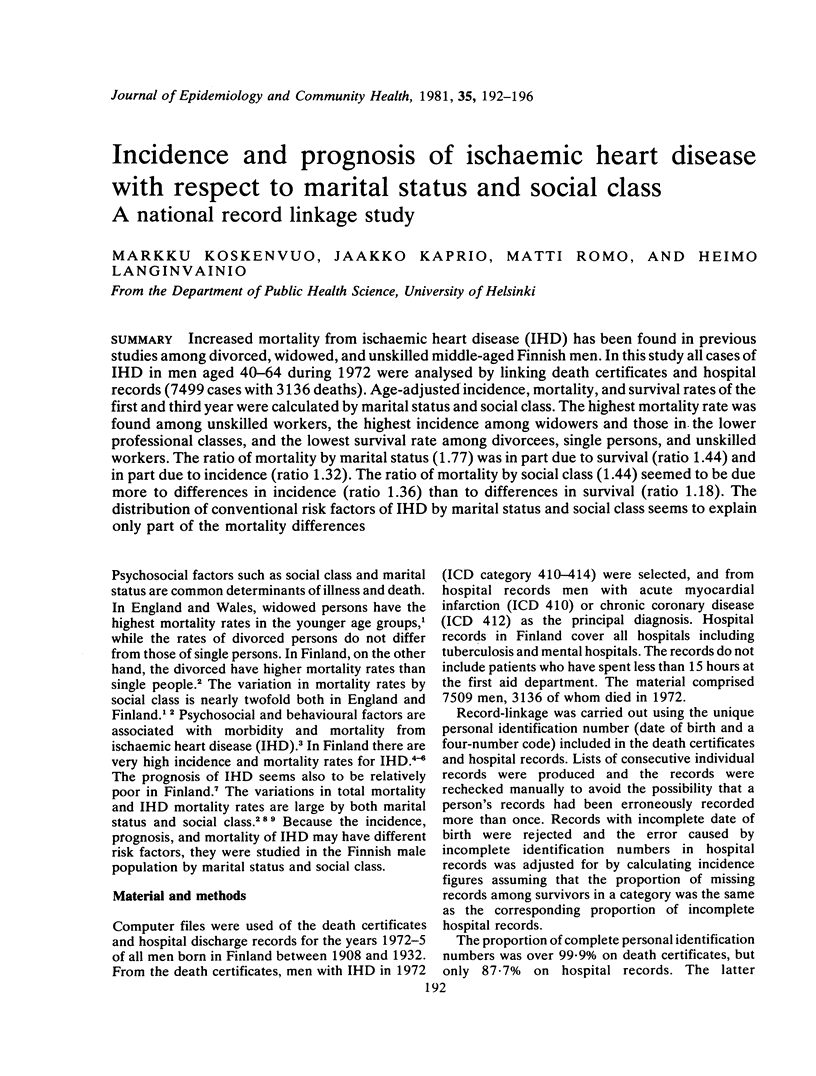

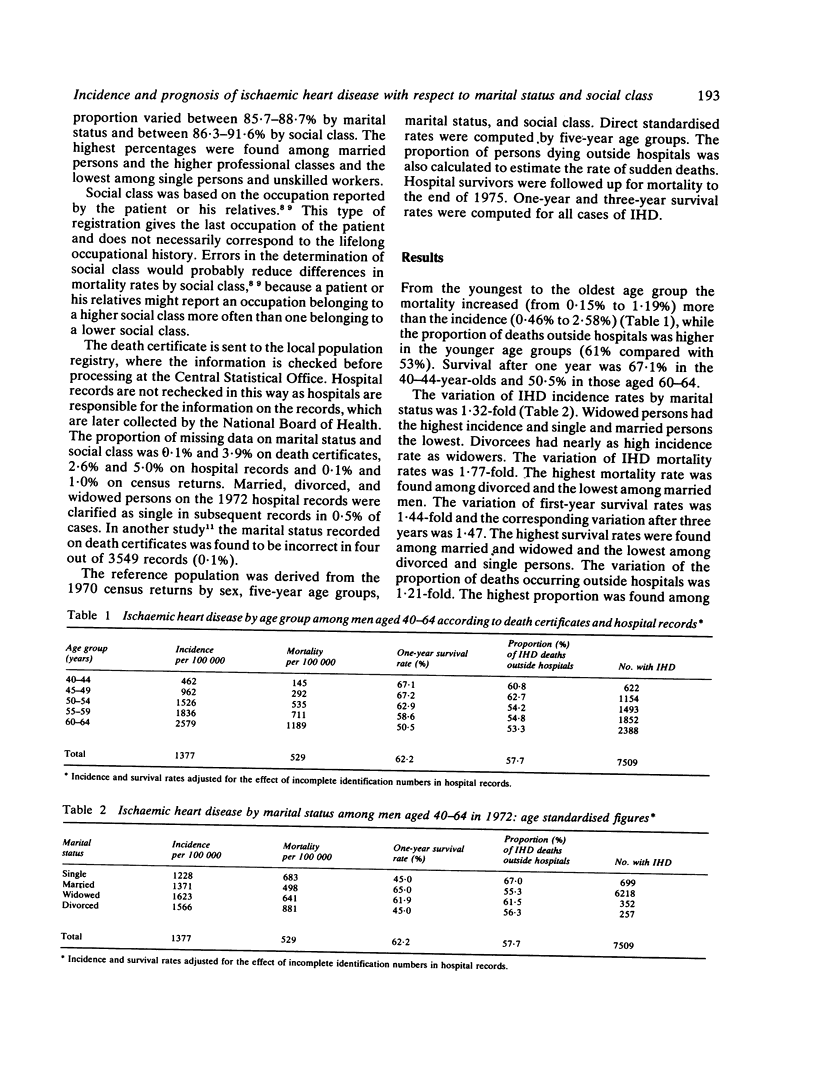

Increased mortality from ischaemic heart disease (IHD) has been found in previous studies among divorced, widowed, and unskilled middle-aged Finnish men. In this study all cases of IHD in men aged 40-64 during 1972 were analysed by linking death certificates and hospital records (7499 cases with 3136 deaths). Age-adjusted incidence, mortality, and survival rates of the first and third year were calculated by marital status and social class. The highest mortality rate was found among unskilled workers, the highest incidence among widowers and those in the lower professional classes, and the lowest survival rate among divorcees, single persons, and unskilled workers. The ratio of mortality by marital status (1.77) was in part due to survival (ratio 1.44) and in part due to incidence (ratio 1.32). The ratio of mortality by social class (1.44) seemed to be due more to differences in incidence (ratio 1.36) than to differences in survival (ratio 1.18). The distribution of conventional risk factors of IHD by marital status and social class seems to explain only part of the mortality differences.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Corr P. B., Sobel B. E. Mechanisms contributing to dysrhythmias induced by ischemia and their therapeutic implications. Adv Cardiol. 1978;(22):110–129. doi: 10.1159/000401022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haney C. A. Life events as precursors of coronary heart disease. Soc Sci Med Med Psychol Med Sociol. 1980 Mar;14A(2):119–126. doi: 10.1016/0160-7979(80)90024-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes S. G., Feinleib M., Levine S., Scotch N., Kannel W. B. The relationship of psychosocial factors to coronary heart disease in the Framingham study. II. Prevalence of coronary heart disease. Am J Epidemiol. 1978 May;107(5):384–402. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins C. D. Behavioral risk factors in coronary artery disease. Annu Rev Med. 1978;29:543–562. doi: 10.1146/annurev.me.29.020178.002551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins C. D. Medical progress. Recent evidence supporting psychologic and social risk factors for coronary disease (first of two parts). N Engl J Med. 1976 Apr 29;294(18):987–994. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197604292941806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaprio J., Sarna S., Koskenvuo M., Rantasalo I. The Finnish Twin Registry: formation and compilation, questionnaire study, zygosity determination procedures, and research program. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1978;24(Pt B):179–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koskenvuo M., Kaprio J., Kesäniemi A., Sarna S. Differences in mortality from ischemic heart disease by marital status and social class. J Chronic Dis. 1980;33(2):95–106. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(80)90033-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koskenvuo M., Sarna S., Kaprio J., Lönnqvist J. Cause-specific mortality by marital status and social class in Finland during 1969--1971. Soc Sci Med Med Psychol Med Sociol. 1979 Nov;13A(6):691–697. doi: 10.1016/0271-7123(79)90114-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmot M. G., Adelstein A. M., Robinson N., Rose G. A. Changing social-class distribution of heart disease. Br Med J. 1978 Oct 21;2(6145):1109–1112. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.6145.1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgenstern H. The changing association between social status and coronary heart disease in a rural population. Soc Sci Med Med Psychol Med Sociol. 1980 May;14A(3):191–201. doi: 10.1016/0160-7979(80)90084-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Näyhä S. Social group and mortality in Finland. Br J Prev Soc Med. 1977 Dec;31(4):231–237. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pohjola S., Siltanen P., Romo M. Five-year survival of 728 patients after myocardial infarction. A community study. Br Heart J. 1980 Feb;43(2):176–183. doi: 10.1136/hrt.43.2.176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahe R. H., Romo M., Bennett L., Siltanen P. Recent life changes, myocardial infarction, and abrupt coronary death. Studies in Helsinki. Arch Intern Med. 1974 Feb;133(2):221–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siltanen P. Life changes and sudden coronary death. Adv Cardiol. 1978;25:47–60. doi: 10.1159/000402005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith J. W. Mortality after recovery from myocardial infarction. J Chronic Dis. 1980;33(1):1–4. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(80)90079-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker K. N., MacBride A., Vachon M. L. Social support networks and the crisis of bereavement. Soc Sci Med. 1977 Jan;11(1):35–41. doi: 10.1016/0037-7856(77)90143-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinblatt E., Ruberman W., Goldberg J. D., Frank C. W., Shapiro S., Chaudhary B. S. Relation of education to sudden death after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1978 Jul 13;299(2):60–65. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197807132990202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss N. S. Marital status and risk factors for coronary heart disease. The United States health examination survey of adults. Br J Prev Soc Med. 1973 Feb;27(1):41–43. doi: 10.1136/jech.27.1.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelmsson C., Vedin J. A., Elmfeldt D., Tibblin G., Wilhelmsen L. Smoking and myocardial infarction. Lancet. 1975 Feb 22;1(7904):415–420. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(75)91488-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]