Abstract

We report on an outbreak of nongroupable Neisseria meningitidis–associated urethritis, primarily among men who have sex with men in southern Vietnam. Nearly 50% of N. meningitidis isolates were resistant to ciprofloxacin. This emerging pathogen should be considered in the differential diagnosis and management of urethritis.

Keywords: Neisseria meningitidis, bacteria, sexually transmitted infections, antimicrobial resistance, urethritis, men who have sex with men, Vietnam

Urogenital and anorectal infections caused by Neisseria meningitidis have been reported in several countries and found to be more prevalent among men who have sex with men (MSM) than among heterosexual men or women (1–3). During 2013–2016, rising numbers of a novel clade of nongroupable N. meningitidis (NmNG) urethritis were reported in multiple US cities and have been termed US NmNG urethritis clade (4). Two cases of US NmNG urethritis were also documented among MSM in the United Kingdom in 2019 (5). We report an outbreak of urethritis associated with US NmNG urethritis clade among men in southern Vietnam.

The Study

We conducted a matched case–control study to investigate N. meningitidis urethritis and risk factors in men seeking treatment for urinary discharge at Ho Chi Minh City Hospital of Dermato-Venereology (HHDV; Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam). Cases of N. meningitidis urethritis were confirmed by either real-time PCR or culture of urethral discharge. Controls were matched to case-patients by age range and sexual orientation (Appendix). During September 2019–December 2020, we recruited 19 case-patients and 76 controls from HHDV (Appendix Figure 1). We collected information on sociodemographic factors, sexual behaviors, and medical history by face-to-face interviews and from medical records (Appendix). The HHDV institutional review board approved the study.

We identified N. meningitidis by using bacterial culture and real-time PCR targeting the sodC gene (6) and determined serogroups by using latex agglutination and real-time PCR. We performed antimicrobial susceptibility testing according to Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute guidelines (7). We conducted whole-genome sequencing, then analyzed multilocus sequence types (MLST) in PubMLST (https://pubmlst.org/organisms/neisseria-spp). We used BEAST (http://beast.community) to estimate the time of bacterial arrival in Vietnam and to conduct antimicrobial-resistance typing (Appendix). We performed conditional logistic regression to assess risk factors for US NmNG urethritis clade by using Stata 14 (StataCorp LLC, https://www.stata.com). We used a log likelihood-ratio test to select the best-fitting model (Appendix).

The mean age of case-patients was lower than that of controls (26.9 vs. 27.8 years). Condom use was low in both case-patients and controls before pyuria developed (5.3% of case-patients, 2.7% of controls). More case-patients than controls lived with male partners (42.1% vs. 13.7%) and had sex with foreign-born persons (15.8% vs. 1.3%). Multivariate analysis results showed that persons living with male partners (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 14.41, 95% CI 1.01–204.62) and having sex with foreign-born persons (aOR 26.78, 95% CI 1.03–697.82) were more likely to contract US NmNG urethritis (Table 1). Moreover, most (79%) case-patients reported sex with male partners. Persons having oral or vaginal sex with female partners in the past 12 months were less likely to have US NmNG urethritis (aOR 0.13, 95% CI 0.02–0.87). Those findings suggest that the US NmNG outbreak was concentrated within the MSM population.

Table 1. Correlates of several selected factors among male patients with Neisseria meningitidis US NmNG urethritis and controls, Vietnam*.

| Variables | Cases, n = 19 | Controls, n = 76 | Univariable analysis† |

Multivariable analysis† |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p value | aOR (95% CI) | p value | ||||

| Mean age, y | 26.9 | 27.8 | 0.90 (0.75–1.07) | 0.232 | NA | ||

| Mean years of education | 10.8 | 11.0 | 0.96 (0.75–1.23) | 0.760 | |||

| Currently living in Ho Chi Minh City |

14 (73.4) |

56 (73.7) |

1.00 (0.30–3.28) |

>0.999 |

|

|

|

| Living arrangements | |||||||

| Live with a female partner | 1 (5.3) | 22 (30.1) | Referent | Referent | |||

| Live with a male partner | 8 (42.1) | 10 (13.7) | 17.03 (1.83–158.26) | 0.013 | 14.41 (1.01–204.62) | 0.049 | |

| Other, e.g., live alone, or with friends

or family |

3 (15.8) |

12 (16.4) |

5.44 (0.65–45.54) |

0.118 |

|

7.0 (0.61–80.24) |

0.118 |

| Ever had sex with | |||||||

| Male sexual partners | 14 (73.7) | 49 (64.5) | Referent | ||||

| Female sexual partners | 4 (21.1) | 16 (21.1) | 0.41 (0.02–7.54) | 0.551 | |||

| Both male and female partners |

1 (5.3) |

11 (14.5) |

0.17 (0.01–3.17) |

0.238 |

|

|

|

| Ever had oral sex |

19 (100.0) |

74 (97.4) |

NA |

|

|

|

|

| Ever participated in group sex |

1 (5.3) |

2 (2.6) |

2 (0.18–22.06) |

0.571 |

|

|

|

| During past 12 mo | |||||||

| Oral or vaginal sex with female partner | 4 (21.1) | 44 (57.9) | 0.10 (0.02–0.47) | 0.004 | 0.13 (0.02–0.87) | 0.035 | |

| Oral or anal sex with male partner | 15 (78.9) | 39 (51.3) | 10.57 (1.28–87.34) | 0.029 | NA | ||

| Any casual partners | 5 (26.3) | 34 (44.7) | 0.39 (0.12–1.32) | 0.131 | NA | ||

| Commercial sex worker partner | 3 (15.8) | 28 (36.8) | 0.30 (0.08–1.15) | 0.078 | |||

| Drunkenness during sex |

3 (15.8) |

23 (30.3) |

0.33 (0.07–1.65) |

0.177 |

|

|

|

| Sex with a foreign-born partner in the past month |

3 (15.8) |

1 (1.3) |

12.0 (1.25–115.36) |

0.031 |

|

26.78 (1.03–697.82) |

0.048 |

| Condom use during sex before symptom onset‡ |

1 (5.3) |

2 (2.7) |

1.81 (0.16–20.08) |

0.628 |

|

|

|

| Used social media sites to find sexual partners |

13 (68.4) |

32 (42.1) |

4.07 (1.17–14.13) |

0.027 |

|

NA |

|

| Ever used ATS§ | 1 (5.3) | 4 (5.3) | 1.00 (0.10–10.07) | >0.999 | |||

*Values are no. (%) except as indicated. ATS, amphetamine-type stimulants; aOR, adjusted odds ratio; NA, not applicable; OR, odds ratio. †Conditional logistic regression. ‡Symptoms were pyuria, dysuria, or both. §Ecstasy, crystal meth (methamphetamine), or other substances used to increase excitement when having sex (also called chemsex).

Among 19 case-patients, 7 were co-infected with >1 other pathogen: 2 (11%) cases of syphilis, 4 (21%) cases of chlamydia, and 1 (0.1%) case involving both ureaplasma and mycoplasma. Ten (83%) case-patients without co-infections and 6 (86%) with co-infections experienced >1 symptom. Pyuria was reported in 2 (29%) co-infected case-patients, and dysuria was reported in 10 (83%) case-patients without co-infections and 3 (43%) with co-infections (Appendix Table 1). Most participants had not received meningococcal vaccines, nor recalled being vaccinated against N. meningitidis (Table 2). The prevalence of HIV, syphilis, and chlamydia infections was higher among case-patients compared to controls but not statistically significant, whereas gonorrhea was only found in controls (98.7%) (Table 2). Multivariate analysis showed that those who had US NmNG urethritis were less likely to report burning sensations during urination (odds ratio [OR] 0.08, 95% CI 0.01–0.46) and more likely to delay seeking treatment (OR 16.0, 95% CI 2.0–127.54) (Table 2).

Table 2. Correlates of demographic characteristics, STI symptoms and pathogens among male patients with N. meningitidis US NmNG urethritis and controls, Vietnam*.

| Variables | Cases, n = 19 | Controls, n = 76 | Univariable analysis† |

Multivariable analysis† |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p value | aOR (95% CI) | p value | ||||

| Mean age, y | 26.9 | 27.8 | 0.90 (0.75–1.07) | 0.232 | NA | ||

| Mean years of education | 10.8 | 11.0 | 0.96 (0.75–1.23) | 0.760 | NA | ||

| Medical examination >3 d after symptom onset |

13 (68.4) |

11 (14.5) |

18.41 (4.04–83.86) |

<0.001 |

|

16.00 (2.00–127.54) |

0.009 |

| Symptoms | |||||||

| Pyuria | 2 (10.5) | 10 (13.2) | 0.79 (0.16–3.79) | 0.764 | NA | ||

| Dysuria | 13 (68.4) | 65 (85.5) | 0.39 (0.12–1.19) | 0.098 | NA | ||

| Burning sensation during urination | 2 (10.5) | 57 (75.0) | 0.05 (0.01–0.22) | <0.001 | 0.08 (0.01–0.46) | 0.005 | |

| Discharge |

4 (21.1) |

16 (21.1) |

1.00 (0.26–3.89) |

>0.999 |

|

|

|

| Time between symptom onset and medical consultation, d | |||||||

| Mean | 4.7 | 3.0 | 1.92 (1.18–3.13) | 0.009 | NA | ||

| Median (range) |

5 (3–12) |

3 (1–14) |

|

|

|

|

|

| History of meningococcal vaccine | |||||||

| Ever | 0 | 1 (1.3) | NA | ||||

| Never | 12 (63.2) | 51 (67.1) | NA | ||||

| Do not know, do not remember |

7 (36.8) |

24 (31.6) |

NA |

|

|

|

|

| Positive tests | |||||||

| HIV | 2 (10.5) | 6 (7.9) | 1.36 (0.26–7.20) | 0.716 | NA | ||

| Syphilis | 2 (10.5) | 3 (3.9) | 2.67 (0.45–15.96) | 0.283 | NA | ||

| Gonorrhea | 0 (0.0) | 75 (98.7) | NA | NA | |||

| Chlamydia | 4 (21.1) | 7 (9.2) | 2.57 (0.67–9.83) | 0.168 | 3.83 (0.37–39.43) | 0.258 | |

| Ureaplasma | 1 (5.3) | 8 (10.5) | 0.48 (0.06–4.01) | 0.502 | NA | ||

| Mycoplasma | 1 (5.3) | 10 (13.2) | 0.39 (0.04–3.10) | 0.372 | NA | ||

*Values are no. (%) except as indicated. aOR, adjusted odds ratio; NA, not applicable; OR, odds ratio. †Conditional logistic regression.

In this study, uncomplicated gonorrhea was treated with a single 500-mg intramuscular dose of ceftriaxone, followed by either a 7-day course of doxycycline (100 mg 2×/day) or a single 1,000-mg dose of azithromycin. In Vietnam, gonococci isolated in 2011 and during 2015–2016 increasingly resisted antimicrobial drugs except for ceftriaxone, spectinomycin, and azithromycin (8). Moreover, 98.3% of N. gonorrhoeae isolates were ciprofloxacin-resistant (9). In a national survey conducted in Vietnam, 30% of persons reported purchasing antibiotics primarily for addressing symptoms, including genitourinary manifestations, and 81.7% did so without a prescription; ciprofloxacin was among the top 5 antimicrobial drugs acquired (10). In another study among MSM in Vietnam, 64% reported ever taking antibiotics without a prescription (11).

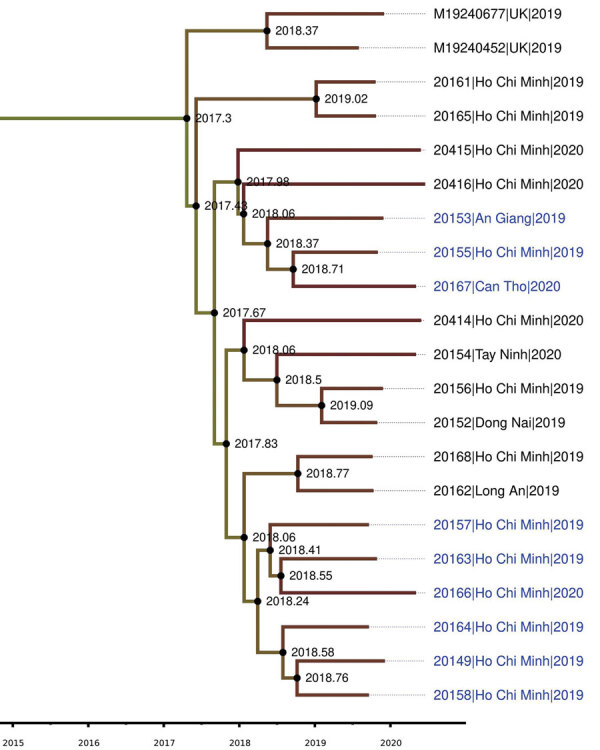

The US NmNG urethritis clade in our study displayed intermediate susceptibility to penicillin, with MIC values ranging from 0.125–0.38 mg/L. Nine of the 19 isolates demonstrated resistance to ciprofloxacin (MIC 0.19–3.0 µg/mL). MLST analysis revealed that the isolates belonged to the sequence type 11 complex (Appendix Table 2). A phylogenetic tree displayed the isolates from Vietnam and the United Kingdom forming a monophyletic clade with those from Ohio, USA, one of the 2 US NmNG urethritis clades (12) (Appendix Figure 2). BEAST analysis estimated that the time of most recent common ancestor of Vietnam and UK isolates appeared between 2016 and 2018 (median 2017.3; 95% high posterior density interval 2016.4–2018.1), with a Bayesian posterior probability of 1.0 (Figure 1; Appendix Figure 3).

Figure 1.

Plylogenetic tree of isolates from an outbreak of sexually transmitted nongroupable Neisseria meningitidis–associated urethritis, Vietnam. Phylogenetic tree was constructed using Baysian Skygrid model, performing with BEAST/BEAGLE version 1.10.4 (https://beast.community/beagle), and displaying with FigTree version 1.4.4 (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/Figtree). Blue text indicates ciprofloxacin-resistant strains. Scale bar indicates the time of evolutionary history.

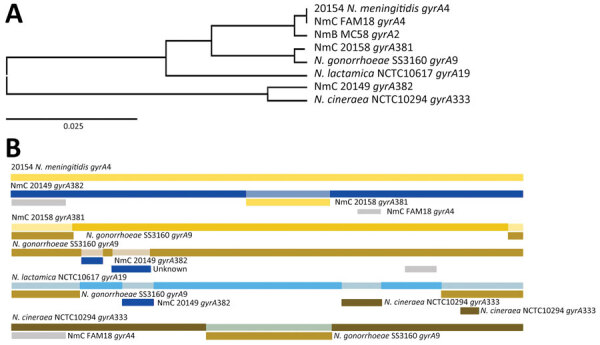

All isolates carried the penA_316 allele and point mutations that reduced their susceptibility to penicillin (13). Nine ciprofloxacin-resistant isolates exhibited 2 new alleles in gyrA, assigned as gyrA_381 (n = 8), which had dual mutations at T91F and D95A, and gyrA_382, which had monomutation at T91I. We used RDP4 (https://rdp4.software.informer.com) to analyze the full 2,751-bp length and found that gyrA_381 received a fragment containing a mutation from gonococci (Figure 2). Our study revealed that isolates containing mutations at both T91F and D95A in the gyrA gene displayed a high level of resistance to ciprofloxacin, similar to that found in N. gonorrhoeae (14). Moreover, isolate 20158 had a mutation at S87R of parC and the gyrA_381 allele had an elevated MIC of 3 µg/mL.

Figure 2.

Whole-genome analysis of isolates from an outbreak of sexually transmitted nongroupable Neisseria meningitidis–associated urethritis, Vietnam. Comparison generated in RDP4 (https://rdp4.software.informer.com) for full length of 2,751-bp. A) Tree shows the genetic relationship between isolate 20158_gyrA381 and gonococci_gyrA9 using unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean of the region derived from their parents, beginning at 1 to ending breakpoint at 337 bp. B) Bars show potential recombination breakage points identified with at least 1 of the 7 methods contained in RDP4. NmB, N. meningitidis B; NmC, N. meningitidis C.

The emergence of ciprofloxacin-resistant N. meningitidis US NmNG urethritis clade in Vietnam is a major concern, especially considering ciprofloxacin resistance is rare in the United Kingdom and United States (4,5). A previous study observed that strains with MICs >0.064 mg/L were correlated with alterations in gyrA (15). Hence, when specimens cannot be cultured, gyrA-sequencing can be particularly useful in predicting susceptibility of ciproloxacin.

Conclusions

We report an outbreak of US NmNG urethritis among men in Vietnam, predominantly MSM. Having sex with foreign-born persons and living with male partners were factors strongly associated with the disease. Isolates in this outbreak might have originated from the Ohio (USA) clade and were mainly resistant to ciprofloxacin, which is commonly used for prophylaxis against invasive meningococcal diseases in Vietnam.

Symptoms among patients with US NmNG urethritis were milder than those in controls with gonococcal urethritis. Because US NmNG urethritis is less likely than gonococcal urethritis to manifest symptoms, clinicians should consider N. meningitidis when managing patients with urethral discharge. Bacterial culture should be routinely performed on urethritis specimens that test N. gonorrhoeae–negative by nucleic acid amplification tests to determine whether the infection is caused by N. meningitidis. More studies with larger sample sizes should be conducted to provide a more comprehensive picture of the burden and clinical symptoms of US NmNG urethritis.

In conclusion, our findings emphasize the importance of ongoing monitoring of appropriate use of antibiotics and antimicrobial resistance to prevent the further spread of resistant US NmNG urethritis clade. Thus, clinicians should be aware of this emerging bacterium and include US NmNG in the differential diagnosis for urethitis.

Additional information on an outbreak of sexually transmitted nongroupable Neisseria meningitidis–associated urethritis, Vietnam.

Acknowledgments

We thank colleagues from Pasteur Institute of Ho Chi Minh’s Laboratory of Respiratory Bacteria and Ho Chi Minh City Hospital of Dermato-Venereology for assisting in the data collection and testing of specimens. We thank Wendy Aft and Minh-Thu Hoang Nguyen for carefully editing the first manuscript. We also thank Richard Yanagihara for his valuable comments and thoroughly editing the revised manuscript.

The findings and conclusions in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the government of Vietnam, the Ministry of Health, the Pasteur Institute of Ho Chi Minh City, and the Ho Chi Minh City Hospital of Dermato-Venereology.

Biography

Dr. H.T. Nguyen is a senior researcher in Ho Chi Minh City Hospital of Dermato-Venereology, Vietnam. His research interests include clinical dermatology and sexually transmitted diseases. Mr. Phan is a microbiologist at Pasteur Institute in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. His research interests focus on the agents that cause bacterial meningitis, particularly Neisseria meningitidis and Streptococcus pneumoniae.

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: Nguyen HT, Phan TV, Tran HP, Vu TTP, Pham NTU, Nguyen TTT, et al. Outbreak of sexually transmitted nongroupable Neisseria meningitidis–associated urethritis, Vietnam. Emerg Infect Dis. 2023 Oct [date cited]. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2910.221596

These first authors contributed equally to this article.

References

- 1.Maini M, French P, Prince M, Bingham JS. Urethritis due to Neisseria meningitidis in a London genitourinary medicine clinic population. Int J STD AIDS. 1992;3:423–5. 10.1177/095646249200300604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hayakawa K, Itoda I, Shimuta K, Takahashi H, Ohnishi M. Urethritis caused by novel Neisseria meningitidis serogroup W in man who has sex with men, Japan. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20:1585–7. 10.3201/eid2009.140349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Givan KF, Keyl A. The isolation of Neisseria species from unusual sites. Can Med Assoc J. 1974;111:1077–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Retchless AC, Kretz CB, Chang H-Y, Bazan JA, Abrams AJ, Norris Turner A, et al. Expansion of a urethritis-associated Neisseria meningitidis clade in the United States with concurrent acquisition of N. gonorrhoeae alleles. BMC Genomics. 2018;19:176. 10.1186/s12864-018-4560-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brooks A, Lucidarme J, Campbell H, Campbell L, Fifer H, Gray S, et al. Detection of the United States Neisseria meningitidis urethritis clade in the United Kingdom, August and December 2019 - emergence of multiple antibiotic resistance calls for vigilance. Euro Surveill. 2020;25:2000375. 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.15.2000375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization. Laboratory methods for the diagnosis of meningitis caused by Neisseria meningitidis, Streptococcus pneumoniae. Geneva: The Organization; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; thirtieth informational supplement (M100–S30). Wayne (PA): The Institute; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lan PT, Golparian D, Ringlander J, Van Hung L, Van Thuong N, Unemo M. Genomic analysis and antimicrobial resistance of Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolates from Vietnam in 2011 and 2015-16. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2020;75:1432–8. 10.1093/jac/dkaa040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adamson PC, Van Le H, Le HHL, Le GM, Nguyen TV, Klausner JD. Trends in antimicrobial resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae in Hanoi, Vietnam, 2017-2019. BMC Infect Dis. 2020;20:809. 10.1186/s12879-020-05532-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nguyen TTP, Do TX, Nguyen HA, Nguyen CTT, Meyer JC, Godman B, et al. A national survey of dispensing practice and customer knowledge on antibiotic use in Vietnam and the implications. Antibiotics (Basel). 2022;11:1091. 10.3390/antibiotics11081091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dong HV, Hoa NT, Minh NXB, Trung NV, May F, Giang LM, et al. Antibiotic usage and commensal pharyngeal Neisseria of MSM in Hanoi, Vietnam. Sex Transm Infect. 2017;93:A52–3. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bazan JA, Peterson AS, Kirkcaldy RD, Briere EC, Maierhofer C, Turner AN, et al. Notes from the field: increase in Neisseria meningitidis-associated urethritis among men at two sentinel clinics—Columbus, Ohio, and Oakland County, Michigan, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:550–2. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6521a5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taha MK, Vázquez JA, Hong E, Bennett DE, Bertrand S, Bukovski S, et al. Target gene sequencing to characterize the penicillin G susceptibility of Neisseria meningitidis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51:2784–92. 10.1128/AAC.00412-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Unemo M, Shafer WM. Antimicrobial resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae in the 21st century: past, evolution, and future. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2014;27:587–613. 10.1128/CMR.00010-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hong E, Thulin Hedberg S, Abad R, Fazio C, Enríquez R, Deghmane AE, et al. Target gene sequencing to define the susceptibility of Neisseria meningitidis to ciprofloxacin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57:1961–4. 10.1128/AAC.02184-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional information on an outbreak of sexually transmitted nongroupable Neisseria meningitidis–associated urethritis, Vietnam.