Abstract

Background:

The recurrence of common bile duct stones and other biliary events after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is frequent. Despite recommendations for early cholecystectomy, intervention during the same admission is carried out inconsistently.

Methods:

We reviewed the records of patients who underwent ERCP for gallstone disease and common bile duct clearance followed by cholecystectomy between July 2012 and June 2022. Patients were divided into 2 groups: the index group underwent cholecystectomy during the same admission and the delayed group was discharged and had their cholecystectomy postponed. Data on demographics and prognosis factors were collected and analyzed.

Results:

The study population was composed of 268 patients, with 71 (26.6%) having undergone cholecystectomy during the same admission after common bile duct clearance with ERCP. A greater proportion of patients aged 80 years and older were in the index group than in the delayed group. The American Society of Anesthesiologists score was significantly higher in the index group. There was no significant difference between groups regarding surgical complications, open cholecystectomy and death. The operative time was significantly longer in the delayed group. Among patients with delayed cholecystectomy, 18.3% had at least 1 recurrence of common bile duct stones (CBDS) and 38.6% had recurrence of any gallstone-related events before cholecystectomy. None of these events occurred in the the index group. There was no difference in the recurrence of CBDS and other biliary events after initial diagnosis associated with stone disease.

Conclusion:

Cholecystectomy during the same admission after common bile duct clearance is safe, even in older adults with comorbidities. Compared with delayed cholecystectomy, it was not associated with adverse outcomes and may have prevented recurrence of biliary events.

Abstract

Contexte

La récurrence de la cholédocholithiase et d’autres lithiases biliaires est fréquente après la cholangiopancréatographie rétrograde endoscopique (CPRE). Même s’il est recommandé de procéder à une cholécystectomie hâtive, l’intervention n’est pas systématiquement effectuée lors d’une même admission pour CPRE.

Méthodes

Nous avons passé en revue les dossiers de personnes ayant subi une CPRE pour extraction de calculs biliaires et de cholédocolithiase suivie de cholécystectomie entre juillet 2012 et juin 2022. Les cas ont été répartis en 2 groupes : le groupe index réunissait les cas ayant subi la cholécystectomie lors de la même admission, et l’autre groupe réunissait ceux dont la cholécystectomie a été faite ultérieurement. Les caractéristiques démographiques et les pronostics ont été recueillis et analysés.

Résultats

La population étudiée comptait 268 personnes, dont 71 (26,6 %) ont subi leur cholécystectomie lors de la même admission après la CPRE pour extraction de cholédocholithiase. Le groupe index comportait un plus grand nombre d’individus de 80 ans et plus que l’autre groupe. Le score ASA (Société américaine des anesthésiologistes) était significativement plus élevé dans le groupe index. On n’a noté aucune différence significative entre les 2 groupes aux plans des complications chirurgicales, de la cholécystectomie ouverte et de la mortalité. Le temps opératoire a été significativement plus long dans le groupe opéré ultérieurement; et chez les patients de ce groupe, 18,3 % ont eu au moins 1 récurrence de cholédocolithiase (CL) et 38,6 % ont eu une récurrence de lithiase biliaire avant de subir leur cholécystectomie. Aucun de ces incidents n’est survenu dans le groupe index. Il n’y a eu aucune différence quant à la récurrence des cholédocholithiases et autres lithiases biliaires après le diagnostic initial de lithiase.

Conclusion:

La cholécystectomie effectuée dans la foulée de l’extraction d’une cholédocholithisase est sécuritaire, même chez les patients âgés présentant des comorbidités. Comparativement à la cholécystectomie effectuée ultérieurement, elle n’a été associée à aucune complication et peut avoir contribué à prévenir une récurrence des lithiases biliaires.

The presence of common bile duct stones (CBDS) in patients with gallstones is estimated to be 5%–30%.1–6 In the era of laparoscopic cholecystectomy, endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography (ERCP) and stone extraction has become the mainstay for CBDS management.7–9 Recurrence of biliary events occurs in 17%–45% of patients after extraction of CBDS, with readmission rates between 10% and 18% within 30 days.10–13 For its part, laparoscopic cholecystectomy following ERCP and stone extraction remains the gold standard of management of choledocholithiasis14,15 and the mainstay in preventing a recurrence of biliary events after common bile duct clearance.2,6,16–21

The timing of cholecystectomy is debatable despite the guidelines recommending early cholecystectomy, either during the same admission or within 2–4 weeks according to the patient’s medical condition.1–4,6,11,12,20,22–28 Studies show advantages in patients undergoing early cholecystectomy.13,16,17,19,22,29–35 Despite evidence and guidelines, early cholecystectomy after ERCP and extraction of gallstones in common bile duct clearance with or without cholangitis or mild biliary pancreatitis is still being carried out in less than 50% of patients.6,12,13,26,36

We aimed to investigate if cholecystectomy performed during the same admission after common bile duct clearance with ERCP is safe in comparison with delayed cholecystectomy.

Methods

Design and setting

We conducted a retrospective study of patients who underwent ERCP for gallstone disease followed by cholecystectomy at Charles-LeMoyne Hospital, Montréal, Canada. Preoperative, operative and post-operative data were collected through individual chart review and individually reviewed medical records.

This study was approved by the Charles-LeMoyne Research Centre and Charles-LeMoyne Hospital ethics committee.

Study population

We evaluated patients aged 18 years or older who underwent both ERCP and cholecystectomy between July 2012 and June 2022. Cholecystectomy records were extracted from the operating room database and ERCP records were extracted from the endoscopy database. Database records were matched to identify patients who underwent both ERCP and cholecystectomy. Patients who had ERCP for CBDS during a first presentation and admission were identified. Patients were included if common bile duct clearance with ERCP was successful during the initial admission. We excluded patients who were younger than 18 years, underwent ERCP for reasons other than gallstone disease, had severe pancreatitis, underwent cholecystectomy without prior ERCP, underwent external investigation, were discharged without complete common bile duct clearance, and who underwent delayed cholecystectomy for medical or miscellaneous conditions.

Patients who underwent cholecystectomy performed during the same admission after ERCP and common bile duct clearance were identified as the index group. Patients who were discharged before undergoing cholecystectomy formed the delayed group.

Variables

We collected information on the following demographic variables and patient characteristics: age, sex, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score, Charlson Comorbidity Index and initial diagnosis related to biliary disease.

Each episode of care with admission was numbered. Dates and types of admission (emergency or elective), diagnoses, timing of all ERCPs, common bile duct clearance (successful or not), number of ERCPs for the common bile duct clearance, types and recurrence of biliary events, date of surgery and date of discharge for each admission were recorded.

Operative and outcome variables included recurrence of CBDS, recurrence of biliary events, number of ERCPs, duration of surgery, conversion or open surgery, surgical complications, length of hospital stay, postoperative stay, readmission stays, pathological status of the gallbladder and death.

Time to common bile duct clearance was the number of days between admission and ERCP showing no residual CBDS. Delay to surgery after common bile duct clearance was the number of days between the ERCP with common bile duct clearance and cholecystectomy.

Recurrence of CBDS was defined as a proven stone after common bile duct clearance and before cholecystectomy. A recurrence of biliary events was defined as any episode of care in relation with gallstone disease (CBDS and others) after common bile duct clearance and before cholecystectomy.

Statistical analysis

We used χ2 or 2-tailed Student t tests for analyzing independent variables. For outcome variables, the χ2 test was used for discrete variables and analysis of variance for continuous variables. We considered results to be significant at p < 0.05.

Results

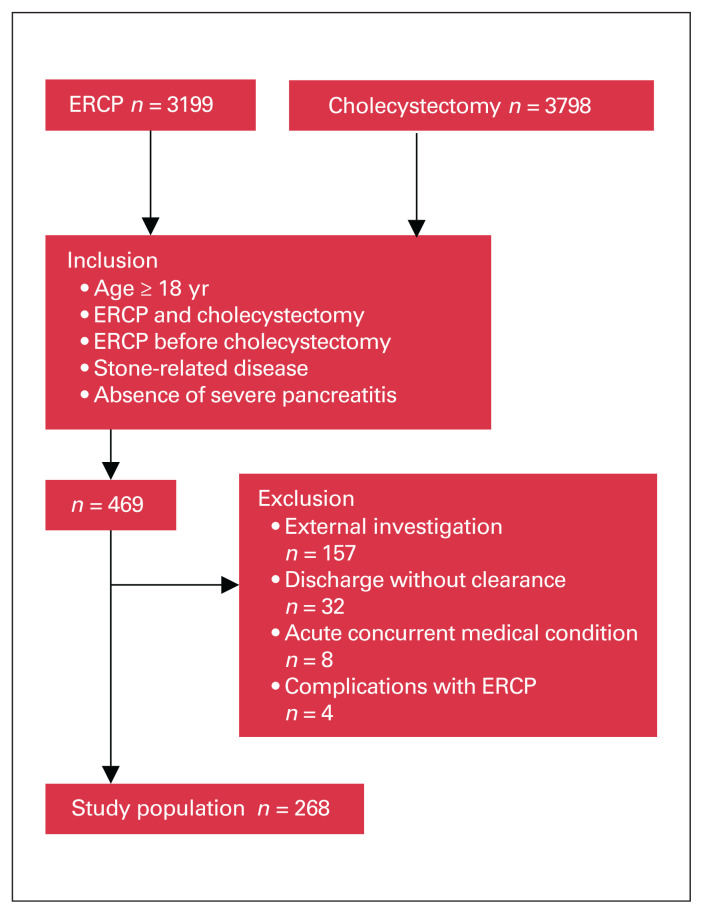

During the 10-year study period, 3798 cholecystectomies and 3199 ERCPs were carried out in our centre. There were 268 patients meeting the inclusion criteria (Figure 1). A total of 278 ERCPs were necessary to achieve common bile duct clearance initially, 96.3% with 1 attempt. Median delay to clear the common bile duct was 3 days. Cholecystectomy was done during the same admission in 71 patients (26.5%) and after a delay in 197 patients (73.5%). In patients with delayed cholecystectomy, the intervention was carried out at a median of 86 (interquartile range [IQR] 50–144) days after common bile duct clearance. One-day elective surgery was successfully achieved in 116 patients (58.9%) in the delayed group. Forty-eight ERCPs were necessary between discharge from initial admission and cholecystectomy in the delayed group.

Fig. 1.

Selection of the study population. ERCP = endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography.

The mean age of patients was 56.9 (IQR 18–95) years, and 145 (54.1%) were female. Table 1 shows the distribution of demographic variables and patient characteristics between the index and delayed groups. Table 1 also shows the distribution of preoperative data according to the timing of surgery and to the initial indication for ERCP. Common bile duct stones without cholangitis or pancreatitis occurred in 141 patients (52.6%).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics and preoperative variables*

| Characteristic | Total (n = 268) | Timing of cholecystectomy, no. (%) | Indication for ERCP,† no. (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Index group (n = 71) | Delayed group (n = 197) | p value‡ | CBDS only (n = 141) | Cholangitis (n = 82) | Pancreatitis (n = 39) | p value‡ | ||

| Sex | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Female | 145 (54.1) | 37 (52.1) | 108 (54.8) | 0.69 | 89 (63.1) | 29 (35.4) | 23 (59.0) | < 0.001 |

|

| ||||||||

| Male | 123 (45.9) | 34 (47.9) | 89 (45.2) | 52 (36.9) | 53 (64.6) | 16 (41.0) | ||

|

| ||||||||

| Age, yr, mean ± SD | 59.6 ± 16.6 | 61.7 ± 17.5 | 58.8 ± 16.2 | 0.74 | 55.3 ± 17.1 | 66.1 ± 13.4 | 61.6 ± 17.3 | < 0.001 |

|

| ||||||||

| 18–59 | 134 (50.0) | 31 (43.7) | 103 (52.3) | 0.21 | 87 (61.7) | 23 (28.0) | 19 (48.7) | < 0.001 |

|

| ||||||||

| > 60 | 134 (50.0) | 40 (56.3) | 94 (47.7) | 0.19 | 54 (38.3) | 59 (72.0) | 20 (51.3) | |

|

| ||||||||

| > 70 | 89 (33.2) | 28 (39.4) | 61 (31.0) | 0.02 | 34 (24.1) | 38 (46.3) | 16 (41.0) | 0.002 |

|

| ||||||||

| > 80 | 24 (8.9) | 11 (15.5) | 13 (6.6) | 9 (6.4) | 10 (12.2) | 5 (12.8) | 0.24 | |

|

| ||||||||

| Comorbidity | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| No comorbidity | 125 (46.6) | 37 (52.1) | 88 (44.7) | 0.28 | 76 (53.0) | 27 (32.9) | 19 (48.7) | 0.01 |

|

| ||||||||

| Charlson Comorbidity Index, mean ± SD | 2.16 ± 1.84 | 2.46 ± 2.03 | 2.06 ± 1.76 | 0.19 | 1.63 ± 1.64 | 3.00 ± 1.80 | 2.43 ± 1.92 | < 0.001 |

|

| ||||||||

| ASA score, mean ± SD | 2.07 ± 0.63 | 2.21 ± 0.61 | 2.01 ± 0.63 | 0.02 | 1.96 ± 0.60 | 2.20 ± 0.60 | 2.00 ± 0.65 | 0.02 |

|

| ||||||||

| I | 42 (15.7) | 6 (8.4) | 36 (18.3) | 0.09 | 27 (19.1) | 5 (6.1) | 8 (20.5) | 0.01 |

|

| ||||||||

| II | 168 (62.7) | 45 (63.3) | 123 (62.4) | 93 (65.9) | 49 (59.7) | 23 (59.0) | ||

|

| ||||||||

| III | 56 (20.9) | 19 (26.8) | 37 (18.8) | 20 (14.2) | 27 (32.9) | 8 (20.5) | ||

|

| ||||||||

| IV | 2 (0.7) | 1 (1.4) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.7) | 1 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | ||

|

| ||||||||

| V | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

|

| ||||||||

| Indications for ERCP | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| CBDS only | 141 (52.6) | 40 (56.3) | 101 (51.3) | 0.22 | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| Cholangitis | 82 (30.6) | 22 (31.0) | 60 (30.4) | |||||

|

| ||||||||

| Pancreatitis | 39 (14.5) | 6 (8.4) | 33 (16.7) | |||||

|

| ||||||||

| Others | 3 (4.2) | 3 (4.2) | 3 (1.5) | |||||

|

| ||||||||

| Concurrent cholecystitis, initial | 90 (35.7) | 42 (59.1) | 48 (24.4) | < 0.001 | 64 (45.4) | 18 (21.9) | 4 (10.2) | < 0.001 |

|

| ||||||||

| Delay before clearance, d, mean ± SD | 4.12 ± 6.27 | 5.00 ± 9.28 | 3.88 ± 4.74 | 0.20 | 3.62 ± 4.24 | 4.01 ± 5.64 | 6.82 ± 11.54 | 0.02 |

|

| ||||||||

| No. of ERCPs for clearance | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 1 | 258 (96.3) | 68 (95.8) | 190 (96.4) | 0.80 | 137 (97.2) | 77 (93.9) | 38 (97.4) | 0.43 |

|

| ||||||||

| 2 | 10 (3.7) | 3 (4.2) | 7 (3.5) | 4 (2.8) | 5 (6.1) | 1 (2.6) | ||

|

| ||||||||

| Sphincterotomy | 225 (83.9) | 58 (81.7) | 167 (84.8) | 0.54 | 124 (87.9) | 72 (87.8) | 27 (69.2) | 0.01 |

|

| ||||||||

| Stent | 117 (43.6) | 27 (38.0) | 90 (45.7) | 0.26 | 60 (42.5) | 44 (53.6) | 11 (28.2) | 0.03 |

|

| ||||||||

| Delay between clearance and surgery, d, mean ± SD | 83.6 ± 96.9 | 2.08 ± 2.02 | 112.9 ± 97.7 | < 0.001 | 72.1 ± 89.3 | 101.1 ± 99.1 | 90.0 ± 113.8 | 0.09 |

ASA = American Society of Anesthesiologists; CBDS = common bile duct stones; ERCP = endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; SD = standard deviation.

Unless indicated otherwise.

Other indications not included for analysis.

χ2 for discrete variables; 2-tailed Student t test for continuous variables.

Table 2 compares the outcome variables between the index and delayed groups. Table 2 also compares outcomes among patients according to the indication for ERCP. Recurrent CBDS and all biliary events occurred in 18.3% and 38.6%, respectively, in the delayed group. No recurrence of biliary events occurred in the index group. There were 110 episodes of recurrence of biliary events in 76 patients (Table 3). Recurrent CBDS and recurrence of biliary events occurred after a median of 41 (IQR 25– 78) days and 44 (IQR 24–97) days, respectively. Cholecystitis was the most frequent (49.1%) among all patients with recurrence of biliary events. The complete list of surgical complications is presented in Table 4.

Table 2.

Outcome variables

| Variable | Total (n = 268) | Timing of cholecystectomy, no. (%) | Indication for ERCP,* no. (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Index (n = 71) | Delayed (n = 197) | p value† | CBDS (n = 141) | Cholangitis (n = 82) | Pancreatitis (n = 39) | p value† | ||

| Recurrent CBDS before surgery | 36 (13.4) | 0 (0.0) | 36 (18.3) | < 0.001 | 19 (13.5) | 12 (14.6) | 5 (12.8) | 0.95 |

|

| ||||||||

| Recurrent CBDS after surgery | 8 (3.0) | 0 (0.0) | 8 (4.1) | 0.08 | 5 (3.5) | 3 (3.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0.48 |

|

| ||||||||

| Recurrence of biliary events | 76 (28.3) | 0 (0.0) | 76 (38.6) | < 0.001 | 68 (48.2) | 30 (36.6) | 8 (20.5) | 0.005 |

|

| ||||||||

| No. of episodes of care | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 1 | 71 (26.4) | 71 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | < 0.001 | 40 (28.4) | 22 (26.8) | 6 (15.4) | 0.13 |

|

| ||||||||

| 2 | 160 (59.7) | 160 (81.2) | 76 (53.9) | 53 (64.6) | 28 (71.8) | |||

|

| ||||||||

| 3 | 30 (11.1) | 30 (15.2) | 22 (15.6) | 5 (6.1) | 2 (7.7) | |||

|

| ||||||||

| 4 | 5 (1.8) | 5 (2.5) | 2 (1.4) | 2 (2.4) | 1 (2.6) | |||

|

| ||||||||

| 5 | 2 (0.7) | 2 (1.0) | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.6) | |||

|

| ||||||||

| Length of hospital stay, d, mean ± SD | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Initial | 6.65 ± 4.95 | 8.31 ± 5.90 | 6.22 ± 4.92 | 0.004 | 5.49 ± 3.49 | 7.79 ± 4.66 | 8.51 ± 8.26 | < 0.001 |

|

| ||||||||

| Total | 9.42 ± 8.11 | 8.31 ± 5.90 | 9.82 ± 8.95 | 0.19 | 8.37 ± 6.52 | 9.83 ± 5.43 | 12.7 ± 15.0 | 0.004 |

|

| ||||||||

| Readmission | 2.64 ± 5.74 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 3.61 ± 6.44 | < 0.001 | 2.88 ± 5.53 | 1.88 ± 2.92 | 3.79 ± 9.86 | 0.21 |

|

| ||||||||

| Postoperative | 1.86 ± 3.56 | 2.35 ± 3.07 | 1.67 ± 3.71 | 0.17 | 1.70 ± 3.21 | 2.02 ± 3.23 | 2.02 ± 5.23 | 0.77 |

|

| ||||||||

| Duration of surgery, min, mean ± SD | 53.3 ± 25.6 | 45.6 ± 16.4 | 56.1 ± 27.7 | 0.003 | 51.2 ± 24.0 | 55.4 ± 26.3 | 56.4 ± 30.2 | 0.36 |

|

| ||||||||

| Conversion or open surgery | 11 (4.1) | 1 (1.4) | 10 (5.1) | 0.18 | 5 (3.5) | 4 (4.9) | 2 (5.1) | 0.85 |

|

| ||||||||

| Surgical complications | 10 (3.7) | 1 (1.4) | 9 (4.6) | 0.23 | 6 (4.2) | 2 (2.4) | 2 (5.1) | 0.71 |

|

| ||||||||

| Diagnosis of cholecystitis, final | 121 (45.1) | 44 (62.0) | 77 (39.1) | < 0.001 | 79 (56.0) | 30 (36.6) | 8 (20.5) | < 0.001 |

|

| ||||||||

| Complicated pathology | 35 (13.0) | 10 (14.1) | 25 (12.7) | 0.76 | 19 (13.5) | 11 (13.4) | 3 (7.7) | 0.61 |

|

| ||||||||

| Death | 1 (0.4) | 1 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0.09 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0.33 |

CBDS = common bile duct stones; ERCP = endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; SD = standard deviation.

Other indications not included for analysis.

χ2 for discrete variables; ANOVA for continuous variables.

Table 3.

Types of recurrence of biliary events

| Type | No. (%) of patients (n = 76) | No. (%) of episodes (n = 110) |

|---|---|---|

| Acute cholecystitis | 46 (17.2) | 54 (49.1) |

| Complicated* | 17 (6.3) | 19 (17.3) |

| Common bile duct stone | 37 (13.8) | 46 (41.8) |

| No cholangitis or pancreatitis | 30 (11.1) | 34 (30.9) |

| Cholangitis | 8 (3.0) | 9 (8.2) |

| Pancreatitis | 3 (1.1) | 3 (2.7) |

| Biliary colic | 7 (2.6) | 7 (6.3) |

| Liver abscess | 2 (0.7) | 2 (1.8) |

| Post ERCP complication | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.9) |

ERCP = endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography.

Purulent or abscessed, gangrenous or perforated.

Table 4.

List of surgical complications

| Surgical complication | Index, n = 1 | Delayed, n = 9 |

|---|---|---|

| Hematoma | 1 | 3 |

| Acute hemorrhage | 3 | |

| Biliary leak | 2 | |

| Peritoneal abscess | 1 |

Discussion

Cholelithiasis is common worldwide and represents a substantial burden on health care resources.37 Its prevalence is 15% in the United States and developed countries,1 with concurrent CBDS between 5% and 30%.1–6 Incidence of cholelithiasis increases with age, affecting 33% of people by age 70 years and as many as 80% by age 90 years,14 and is associated with excess mortality.5 Common bile duct stones may eventually cause cholangitis, pancreatitis, biliary obstruction and death.13 Acute pancreatitis or acute cholangitis occurs secondary to CBDS in as many as 20% of cases.9 Mortality associated with pancreatitis may be as high as 30% in severe cases,8 while cholangitis may cause death in more than 10% of cases.8,13

Although evolving alternatives exist,32 ERCP remains the mainstay to remove CBDS.7–9 The major concern in delaying or not proceeding with cholecystectomy is the recurrence of biliary events after removal of CBDS, with consequences on readmission rates, complications and death related to further episodes, supplementary ERCP and delayed cholecystectomy.6,16,19,38 A recurrence of biliary events after common bile duct clearance with ERCP occurs in 25%–76% of patients with gallbladder left in situ,7,16,17,21,30,35 and the risk increases as the number of recurrences increases.9,39

Cholecystectomy and clearance of stones from the biliary tree remain the mainstay of definitive treatment to prevent a recurrence of biliary events and readmissions.2,6,14–17,19,37,40 Gallbladder in situ is an independent risk factor of biliary pancreatitis or any recurrence of biliary events,41,42 and ERCP with sphincterotomy alone is not sufficient to prevent these episodes.1,6,11,20,22,40 A recurrence of biliary events generally happens while awaiting cholecystectomy39 and occurs in 20%–60% of patients before elective surgery.13,14,16,17,19,37,40 International guidelines recommend early cholecystectomy after episodes of cholangitis23 and pancreatitis3,13,24–28 and following the removal of obstructive CBDS,1,2,20 unless there are specific reasons for considering surgery inappropriate or prohibitively risky.2,9,14,26,35 However, the definition of early cholecystectomy is not uniform, as the optimal timing after common bile duct clearance with ERCP varies among studies from within 24 hours,8,43 72 hours,8,10,12,13,17,31,33,37,43,44 7 days9,20 to 2 weeks,2,22,27 or at the latest 3 weeks, according to the Dutch Pancreatitis Study Group.40 In addition, current guidelines recommend cholecystectomy within the same admission3,15,20,23–25 or within 2 weeks.2,27 The sooner the cholecystectomy is carried out after common bile duct clearance, the better the reduction in the risk of recurrence of biliary events.12,13 The pattern of recurrence of biliary events in our study, all of which occurred in the delayed group with one-half of the first episodes within about 6 weeks, supports this conclusion.

We saw no difference in the rate of open surgery, either planned or converted, after initial laparoscopic attempt. The use of ERCP itself is reported to be a risk factor of difficult cholecystectomy45 or conversion,37 particularly after multiple exams34 or if a stent is left in place.46 However, our study does not allow conclusions about the contribution of ERCP to the difficulty of cholecystectomy. In the majority of studies, no significant difference was observed in conversion rates between early and delayed cholecystectomy,6,29,33,34,37,44 specifically for patients with surgery during the same admission.22,30 Other studies reported significantly increased conversion rates in patients with delayed cholecystectomy.15,16,19,33,43 A review of 14 studies with a total of 1930 patients reported a conversion rate of 4% if cholecystectomy was carried out within 24 hours after ERCP, and up to 14% if cholecystectomy occurred after 6 weeks.43 The European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy strongly recommends performing laparoscopic cholecystectomy within 2 weeks of ERCP to reduce the conversion rate as well as the risk of recurrence of biliary events.1 Operative time may represent a surrogate of the difficulty of operation.31 The majority of studies showed either no difference16,17,19,29,30 or an increased operative time31,33 in late compared with early cholecystectomy, even for index cholecystectomy.31 Also, the rate of surgical complications, as we found in our study, is not increased if cholecystectomy is carried out during the index admission.13,22,30 Similar to others,13,22,30 we found no difference in surgical complications after index compared with delayed cholecystectomy. However, fear of conversion or difficulty in doing early cholecystectomy after ERCP should not be a concern.17,31,37

Older adults with more prevalent comorbidities pose an additional challenge in surgery.4 In a multivariate analysis, age 70 years or older, higher comorbidity score and ASA score (> II) were found to be predictors of 30-day mortality.47 In another meta-analysis, cholecystectomy was shown to reduce the occurrence of biliary complications even in high-risk patients.7 Risk of recurrence of biliary events, even in older adults, may be as high as 30%.48 While expectant management can be regarded as a safe option in high-risk populations,18,35 others studies have shown that cholecystectomy is a safe procedure in older adult patients.9,21,49 We found patients in the index group had a slightly but significantly higher ASA score. Patients 80 years and older were also more prevalent in the index group. This is in contradiction with other studies in which the decision to delay or to not undergo cholecystectomy was substantially favoured in older adults and patients with more comorbidities.6,12,14,18,50 Cholecystectomy remains recommended as a safe procedure even in patients with higher ASA scores7,21 and adults aged 80 years and older.4,49 In patients with ASA scores of I–III, considering the absence of less favourable outcomes between groups, index cholecystectomy after ERCP may be considered safe as in the recommended guidelines.1,2,20,23,27,40,51

The percentage of patients with recurrent CBDS after cholecystectomy was low and all cases occurred in the delayed group (4.1%). However, cases may have been missed. We also did not evaluate readmission after cholecystectomy for other related causes, especially recurrent pancreatitis, but other studies identified that this specific risk is highly diminished in index or very early cholecystectomy after ERCP.1,6,12,22,36 Both initial and post-operative stays were longer in the index group. This is probably attributable to the high proportion of patients with acute cholecystitis, along with wait times for endoscopic ultrasound, ERCP and surgery while in hospital. However, this difference disappears when readmissions are added to the total length of hospital stay (Table 2).

We found the proportion of index cholecystectomy (26.5 %) to be definitively low, but a few recent studies reported index procedures in more than 50% of cases despite recommendations.22,30 However, great variations exist, ranging from 7% to 64%.6,12,22,26,30,36,52,53 A large database of 52 906 patients with cholangitis identified only 6.9% as cases with cholecystectomy within 30 days.52 In a practice audit including all types of indications, only 50% had index cholecystectomy.53 The decision not to operate lies initially with the surgeon who is the treating physician for patients with gallbladder in situ in our centre. From our results, we definitively support increasing the rate of index cholecystectomy.

The operating room for emergency surgery is available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. The lack of resources, particularly the availability of the operating room during the daytime,11,54 and competition with busy elective practices11 are, like others,1,41,50 additional reasons to delay surgery. Implementing an acute care surgery model with dedicated operative time would be a solution to partially alleviate this problem,11,55 although surgeons remain reluctant to perform cholecystectomy at night. We have found that patients are rarely opposed to undergoing cholecystectomy during the same admission, except sometimes older adults. Informing patients, emphasizing the potential problems of delayed cholecystectomy that our study and others have shown, is important in this preferred approach.6,8–10,12,13,20,35,40–42 Therapeutic ERCP is the gold standard for extraction of CBDS.8,23,28 Complications may occur in 4%–8% of cases,3,22,38 and ERCP may be unnecessary in some situations.20,25 In our centre, we have local access and expertise with endoscopic ultrasound. Patients are referred directly for ERCP when very strong predictors of CBDS (stone in imaging, cholangitis or bilirubin > 4 mg/dL [> 68 μmol/L]) are present.25 Indication for ERCP complies with Tokyo guidelines23 and American College of Gastroenterology guidelines28 for cholangitis. In addition, there are recommendations to carry out ERCP and CBDS extraction as early as possible8,22,36,56 and even at index admission for biliary indications.56 Thus, combining recommendations for index ERCP8,22,28,36,56 and index cholecystectomy,1,2,5,13,20,22,23,27,30,40,51 the best practice is to perform both CBDS extraction and surgery at the same initial admission.

Limitations

The single-centre retrospective design of our study presents some limitations. All charts were individually reviewed, a strength that eliminates the majority of missing data from registries. By combining both databases of procedures (cholecystectomies and ERCPs), it is unlikely that patient data were missing from our analyses. We cannot draw conclusions about surgery compared with no surgery because the study included only patients who underwent cholecystectomy. Patients with possible “rescue” cholecystectomy could not be identified, but the percentage of patients who underwent rescue cholecystectomy could be as high as 35%.21,49 The absence of patients with ASA scores of IV probably represents a selection bias, but there was no such precedence reported in the literature for such patients, qualifying them not fit for surgery.2,9 Unfortunately, there was rarely any clear description of specific reasons to avoid surgery in the records of patients. When cholecystectomy was not performed during the index admission, we presumed that, except in cases where there was an evident medical reason for the decision, delayed cholecystectomy was planned. Specifically, decisions for expectant management were rarely identified. Since there are surrounding centres (our centre is part of greater Montréal and suburbs), our analyses may have missed patients who consulted elsewhere for recurrence of biliary events or surgery. Also, it was not possible to identify patients who died or suffered major complications (related or not with gallstone disease) requiring surgery. However, we think that few patients in our population consulted other centres and that this would not alter the conclusions of our study. As cholecystectomy is the cornerstone of the study design, no conclusions can be drawn or extrapolated regarding patients not considered for surgery.

Patients who had cholecystectomy after common bile duct clearance with ERCP during the same hospital admission were older and had higher ASA scores than those who had delayed cholecystectomy. However, a shorter operative time for index cholecystectomy could be attributed to a relatively easier intervention than in the case of delayed intervention. Despite its weaknesses, our study shows index cholecystectomy prevents recurrence of biliary events after common bile duct clearance with ERCP without compromising surgical outcomes, even in older adults and patients with complex or several comorbidities.

Conclusion

Delaying cholecystectomy does not lead to better outcomes for patients after common bile duct clearance with ERCP. Cholecystectomy during the index admission is safe, even for older adults and patients with comorbidities. Our study supports the current guideline recommendations for early and index cholecystectomy after common bile duct clearance.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

Contributors: E. Bergeron and E. Désilets designed the study. T. Doyon and E. Bergeron acquired the data, which E. Bergeron, E. Désilets and T. Manière analyzed. E. Bergeron and E. Désilets wrote the article, which all authors reviewed. All authors approved the final version to be published.

References

- 1.Manes G, Paspatis G, Aabakken L, et al. Endoscopic management of common bile ductstones: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) guideline. Endoscopy 2019;51:472–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Williams E, Beckingham I, El Sayed G, et al. Updated guideline on the management of common bile duct stones (CBDS). Gut 2017;66:765–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buxbaum JL, Abbas Fehmi SM, Sultan S, et al. ASGE guideline on the role of endoscopy in the evaluation and management of choledocholithiasis. Gastrointest Endosc 2019;89:1075–1105.e15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nassar Y, Richter S. Management of complicated gallstones in the elderly: comparing surgical and non-surgical treatment options. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf) 2019;7:205–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ruhl CE, Everhart JE. Gallstone disease is associated with increased mortality in the United States. Gastroenterology 2011;140:508–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huang RJ, Barakat MT, Girotra M, et al. Practice patterns for cholecystectomy after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography for patients with choledocholithiasis. Gastroenterology 2017;153:762–771.e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu J, Yang C. Cholecystectomy outcomes after endoscopic sphincterotomy in patients with choledocholithiasis: a meta-analysis. BMC Gastroenterol 2020;20:229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mulki R, Shah R, Qayed E. Early vs late endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in patients with acute cholangitis: a nationwide analysis. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2019;11:41–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu Y, Xu CJ, Xu SF. Advances in risk factors for recurrence of common bile duct stones. Int J Med Sci 2021;18:1067–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murphy PB, Paskar D, Hilsden R, et al. Western Ontario Research Collaborative on acute care surgery. Acute care surgery: a means for providing cost-effective, quality care for gallstone pancreatitis. World J Emerg Surg 2017;12:20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li S, Su B, Chen P, et al. Risk factors for recurrence of common bile duct stones after endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy. J Int Med Res 2018;46:2595–605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krishna SG, Kruger AJ, Patel N, et al. Cholecystectomy during index admission for acute biliary pancreatitis lowers 30-day readmission rates. Pancreas 2018;47:996–1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.da Costa DW, Bouwense SA, Schepers NJ, et al. Dutch Pancreatitis Study Group. Same-admission versus interval cholecystectomy for mild gallstone pancreatitis (PONCHO): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2015;386:1261–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Edwards K, Johnson G, Bednarz J, et al. Long-term outcomes of elderly patients managed without early cholecystectomy after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and sphincterotomy for choledocholithiasis. Cureus 2021;13:e19074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Banks PA, Freeman ML. Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Practice guidelines in acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol 2006;101:2379–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boerma D, Rauws EA, Keulemans YC, et al. Wait-and-see policy or laparoscopic cholecystectomy after endoscopic sphincterotomy for bile-duct stones: a randomised trial. Lancet 2002;360:761–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lau JY, Leow CK, Fung TM, et al. Cholecystectomy or gallbladder in situ after endoscopic sphincterotomy and bile duct stone removal in Chinese patients. Gastroenterology 2006;130:96–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Archibald JD, Love JR, McAlister VC. The role of prophylactic cholecystectomy versus deferral in the care of patients after endoscopic sphincterotomy. Can J Surg 2007;50:19–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schiphorst AH, Besselink MG, Boerma D, et al. Timing of cholecystectomy after endoscopic sphincterotomy for common bile duct stones. Surg Endosc 2008;22:2046–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Gallstone disease: diagnosis and management of cholelithiasis, cholecystitis and choledocholithiasis. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE); 2014. PMID: . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McAlister VC, Davenport E, Renouf E. Cholecystectomy deferral in patients with endoscopic sphincterotomy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007;2007:CD006233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Noel R, Arnelo U, Lundell L, et al. Index versus delayed cholecystectomy in mild gallstone pancreatitis: results of a randomized controlled trial. HPB (Oxford) 2018;20:932–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mayumi T, Okamoto K, Takada T, et al. Tokyo Guidelines 2018: management bundles for acute cholangitis and cholecystitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 2018;25:96–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Working Group IAP/APA Acute Pancreatitis Guidelines. IAP/APA evidence-based guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis. Pancreatology 2013;13:e1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crockett SD, Wani S, Gardner TB, et al. American Gastroenterological Association Institute Clinical Guidelines Committee. American Gastroenterological Association Institute guideline on initial management of acute pancreatitis. Gastroenterology 2018;154:1096–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Greenberg JA, Hsu J, Bawazeer M, et al. Compliance with evidence-based guidelines in acute pancreatitis: an audit of practices in University of Toronto Hospitals. J Gastrointest Surg 2016;20:392–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Working Party of the British Society of Gastroenterology; Association of Surgeons of Great Britain and Ireland; Pancreatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland; Association of Upper GI Surgeons of Great Britain and Ireland. UK guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis. Gut 2005;54 Suppl 3(Suppl 3):iii1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tenner S, Baillie J, DeWitt J, et al. American College of Gastroenterology guideline: management of acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol 2013;108:1400–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zang JF, Zhang C, Gao JY. Endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography and laparoscopic cholecystectomy during the same session: feasibility and safety. World J Gastroenterol 2013;19:6093–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hoilat GJ, Hoilat JN, Abu-Zaid A, et al. Impact of early cholecystectomy on the readmission rate in patients with acute gallstone cholangitis: a retrospective single-centre study. BMJ Open Gastroenterol 2021;8:e000705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goel A, Kothari S, Bansal R. Comparative analysis of early versus late laparoscopic cholecystectomy following endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreaticography in cases of cholelithiasis with choledocholithiasis. Euroasian J Hepatogastroenterol 2021;11:11–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Senocak R, Çelik SU, Kaymak S, et al. Perioperative outcomes of the patients treated using laparoscopic cholecystectomy after emergent endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography for bile duct stones: does timing matter? Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg 2020; 26:396–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Salman B, Yilmaz U, Kerem M, et al. The timing of laparoscopic cholecystectomy after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreaticography in cholelithiasis coexisting with choledocholithiasis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 2009;16:832–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bostanci EB, Ercan M, Ozer I, et al. Timing of elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreaticography with sphincterotomy: a prospective observational study of 308 patients. Langenbecks Arch Surg 2010; 395:661–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mattila A, Mrena J, Kellokumpu I. Expectant management of gall-bladder stones after endoscopic removal of common bile duct stones. Int J Surg 2017;43:107–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nguyen GC, Rosenberg M, Chong RY, et al. Early cholecystectomy and ERCP are associated with reduced readmissions for acute biliary pancreatitis: a nationwide, population-based study. Gastrointest Endosc 2012;75:47–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang CC, Tsai MC, Wang YT, et al. Role of cholecystectomy in choledocholithiasis patients underwent endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Sci Rep 2019;9:2168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Andriulli A, Loperfido S, Napolitano G, et al. Incidence rates of post-ERCP complications: a systematic survey of prospective studies. Am J Gastroenterol 2007;102:1781–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kawaji Y, Isayama H, Nakai Y, et al. Multiple recurrences after endoscopic removal of common bile duct stones: a retrospective analysis of 976 cases. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019;34(8):1460–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bakker OJ, van Santvoort HC, Hagenaars JC, et al. Dutch Pancreatitis Study Group. Timing of cholecystectomy after mild biliary pancreatitis. Br J Surg 2011;98:1446–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Garg SK, Bazerbachi F, Sarvepalli S, et al. Why are we performing fewer cholecystectomies for mild acute biliary pancreatitis? Trends and predictors of cholecystectomy from the National Readmissions Database (2010–2014). Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf) 2019;7:331–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim SB, Kim TN, Chung HH, et al. Small gallstone size and delayed cholecystectomy increase the risk of recurrent pancreatobiliary complications after resolved acute biliary pancreatitis. Dig Dis Sci 2017;62:777–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Friis C, Rothman JP, Burcharth J, et al. Optimal timing for laparoscopic cholecystectomy after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography: a systematic review. Scand J Surg 2018;107:99–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Aziret M, Karaman K, Ercan M, et al. Early laparoscopic cholecystectomy is associated with less risk of complications after the removal of common bile duct stones by endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Turk J Gastroenterol 2019;30:336–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Reinders JS, Gouma DJ, Heisterkamp J, et al. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is more difficult after a previous endoscopic retrograde cholangiography. HPB (Oxford) 2013;15:230–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nair MS, Uzzaman MM, Fafemi O, et al. Elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy in the presence of common bile duct stent. Surg Endosc 2011;25:429–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sandblom G, Videhult P, Crona Guterstam Y, et al. Mortality after a cholecystectomy: a population-based study. HPB (Oxford) 2015;17:239–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fritz E, Kirchgatterer A, Hubner D, et al. ERCP is safe and effective in patients 80 years of age and older compared with younger patients. Gastrointest Endosc 2006;64:899–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Costi R, DiMauro D, Mazzeo A, et al. Routine laparoscopic cholecystectomy after endoscopic sphincterotomy for choledocholithiasis in octogenarians: is it worth the risk? Surg Endosc 2007;21:41–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Karpuz S, Attaallah W. Could cholecystectomy be abandoned after removal of bile duct stones by endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreaticography? Asian J Surg 2021;44:939–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pisano M, Allievi N, Gurusamy K, et al. 2020 World Society of Emergency Surgery updated guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute calculus cholecystitis. World J Emerg Surg 2020;15:61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Parikh MP, Garg R, Chittajallu V, et al. Trends and risk factors for 30-day readmissions in patients with acute cholangitis: analysis from the national readmission database. Surg Endosc 2021;35:223–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bass GA, Gillis A, Cao Y, et al. European Society for Trauma, Emergency Surgery (ESTES) Cohort Studies Group. Patterns of prevalence and contemporary clinical management strategies in complicated acute biliary calculous disease: an ESTES ‘snapshot audit’ of practice. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg 2022;48:23–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fletcher E, Seabold E, Herzing K, et al. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy in the acute care surgery model: risk factors for complications. Trauma Surg Acute Care Open 2019;4:e000312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hardy K, Metcalfe J, Clouston K, et al. The impact of an acute care surgical service on the quality and efficiency of care outcome indicators for patients with general surgical emergencies. Cureus 2019;11:e5036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Krill TS, Crain R, Al-Saadi Y, et al. Predictors of 30-day readmission after inpatient endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography: a single-center experience. Dig Dis Sci 2020;65:1481–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]