Abstract

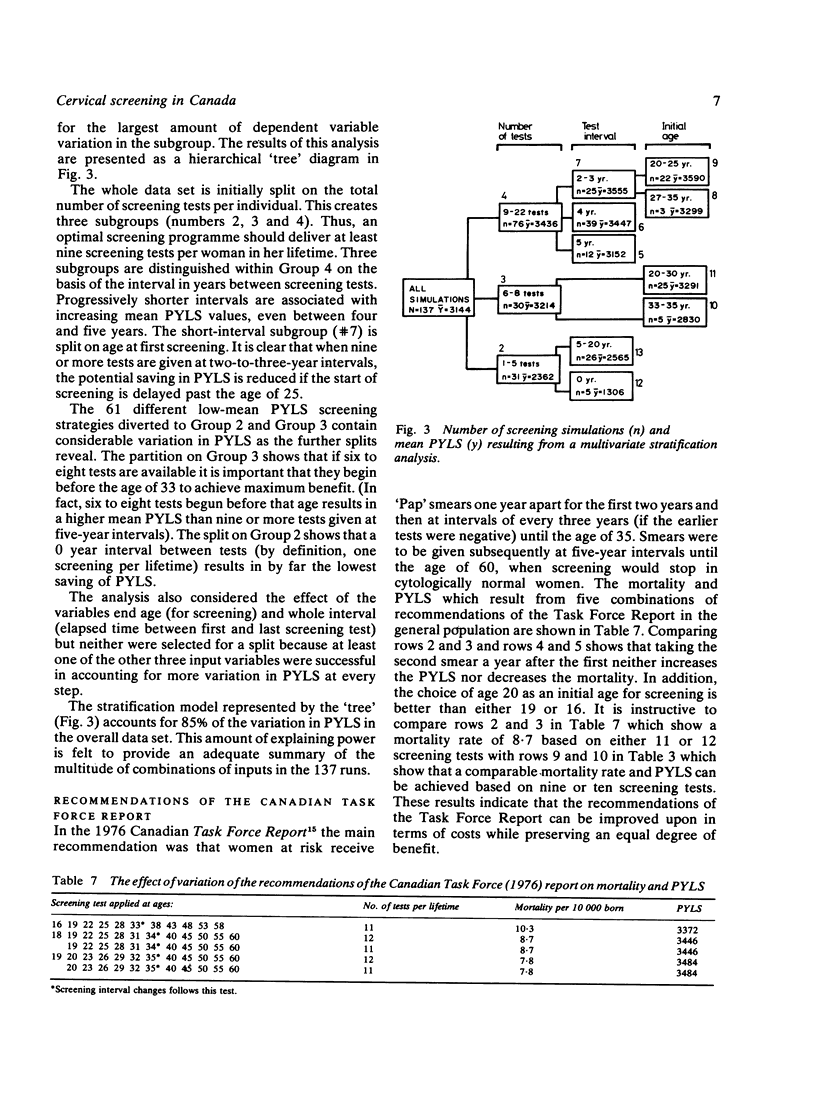

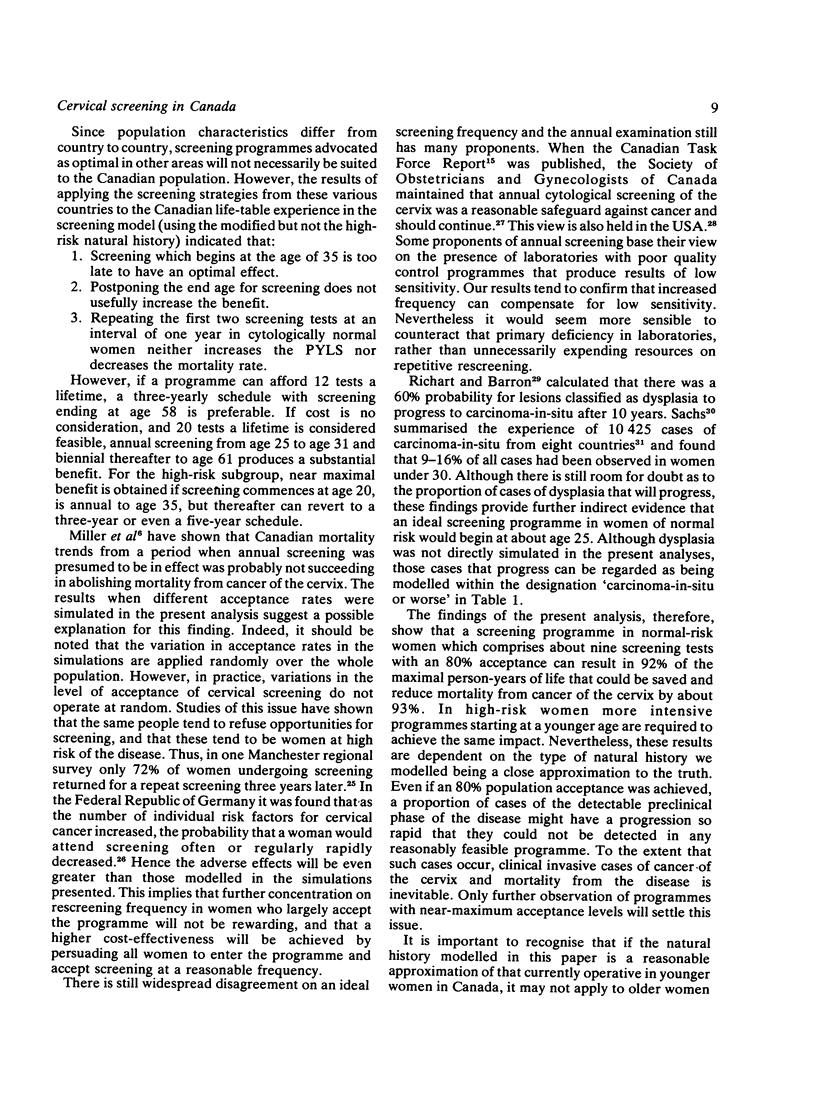

Different approaches to screening for cancer of the cervix by cervical cytology have been evaluated using a computer simulation model developed by Knox and data on the natural history of carcinoma-in-situ (or worse) from a cohort study of women screened in British Columbia, 1949-69. The natural history input parameters and the output parameters without screening were modified to reflect the earlier onset of carcinoma-in-situ in younger cohorts now being experienced in British Columbia, resulting in simulated mortality from carcinoma of the cervix approximately 50% greater than that experienced in Canada in 1955. The simulations showed that the sensitivity of the test and the proportion of women in the population who accept invitations to attend for screening materially influence the extent to which programmes reduce mortality. Missed screens also have an important impact. With a 75% test sensitivity, and an 80% population acceptance, a programme designed to reduce mortality by 90% would commence at age 25, involve triennial screens to age 52, or triennial screens to age 40 and quinquennial screens to age 60, a total of 10 tests in a lifetime. A repeat test at age 26 contributes nothing to the mortality benefit. Nevertheless, additional modifications of the natural history specifications to accommodate high-risk younger women would require a more frequent schedule of examinations under the age of 35, though at a substantial 'cost' in terms of the total number of examinations required in a population.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Andersen R., Smedby B., Eklund G. Automatic interaction detector program for analyzing health survey data. Health Serv Res. 1971 Summer;6(2):165–183. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brindle G., Wakefield J., Yule R. Cervical smears: are the right women being examined? Br Med J. 1976 May 15;1(6019):1196–1197. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.6019.1196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke E. A., Anderson T. W. Does screening by "Pap" smears help prevent cervical cancer? A case-control study. Lancet. 1979 Jul 7;2(8132):1–4. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(79)90172-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foltz A. M., Kelsey J. L. The annual Pap test: a dubious policy success. Milbank Mem Fund Q Health Soc. 1978 Fall;56(4):426–462. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner J. W., Lyon J. L. Efficacy of cervical cytologic screening in the control of cervical cancer. Prev Med. 1977 Dec;6(4):487–499. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(77)90034-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakama M., Räsänen-Virtanen U. Effect of a mass screening program on the risk of cervical cancer. Am J Epidemiol. 1976 May;103(5):512–517. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland W. W. Taking stock. Lancet. 1974 Dec 21;2(7895):1494–1497. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(74)90230-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homesley H. D. Evaluation of the abnormal Pap smear. Am Fam Physician. 1977 Sep;16(3):190–194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johannesson G., Geirsson G., Day N. The effect of mass screening in Iceland, 1965-74, on the incidence and mortality of cervical carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 1978 Apr 15;21(4):418–425. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910210404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knox E. G. Ages and frequencies for cervical cancer screening. Br J Cancer. 1976 Oct;34(4):444–452. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1976.190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macgregor J. E., Teper S. Uterine cervical cytology and young women. Lancet. 1978 May 13;1(8072):1029–1031. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(78)90750-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller A. B., Lindsay J., Hill G. B. Mortality from cancer of the uterus in Canada and its relationship to screening for cancer of the cervix. Int J Cancer. 1976 May 15;17(5):602–612. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910170508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller A. B., Visentin T., Howe G. R. The effect of hysterectomies and screening on mortality from cancer of the uterus in Canada. Int J Cancer. 1981 May 15;27(5):651–657. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910270512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richart R. M., Barron B. A. A follow-up study of patients with cervical dysplasia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1969 Oct 1;105(3):386–393. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(69)90268-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romeder J. M., McWhinnie J. R. Potential years of life lost between ages 1 and 70: an indicator of premature mortality for health planning. Int J Epidemiol. 1977 Jun;6(2):143–151. doi: 10.1093/ije/6.2.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sansom C. D., MacInerney J., Oliver V., Wakefield J., Yule R. Recall of women in a cervical cytology screening programme. An estimate of the true rate of response. Br J Prev Soc Med. 1975 Jun;29(2):131–134. doi: 10.1136/jech.29.2.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt O. A. Cervical cancer screening programs: the SOGC's view. Can Med Assoc J. 1977 May 7;116(9):971-2, 975. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]