Abstract

Integrating sensory information during movement and adapting motor plans over successive movements are both essential for accurate, flexible motor behaviour. When an ongoing movement is off target, feedback control mechanisms update the descending motor commands to counter the sensed error. Over longer timescales, errors induce adaptation in feedforward planning so that future movements become more accurate and require less online adjustment from feedback control processes. Both the degree to which sensory feedback is integrated into an ongoing movement and the degree to which movement errors drive adaptive changes in feedforward motor plans have been shown to scale inversely with sensory uncertainty. However, since these processes have only been studied in isolation from one another, little is known about how they are influenced by sensory uncertainty in real-world movement contexts where they co-occur. Here, we show that sensory uncertainty may impact feedforward adaptation of reaching movements differently when feedback integration is present versus when it is absent. In particular, participants gradually adjust their movements from trial-to-trial in a manner that is well characterised by a slow and consistent envelope of error reduction. Riding on top of this slow envelope, participants exhibit large and abrupt changes in their initial movement vectors that are strongly correlated with the degree of sensory uncertainty present on the previous trial. However, these abrupt changes are insensitive to the magnitude and direction of the sensed movement error. These results prompt important questions for current models of sensorimotor learning under uncertainty and open up new avenues for future exploration in the field.

Author summary

A large body of literature shows that sensory uncertainty inversely scales the degree of error-driven corrections made to motor plans from one trial to the next. However, by limiting sensory feedback to the endpoint of movements, these studies prevent corrections from taking place during the movement. Here, we show that when such corrections are promoted, sensory uncertainty punctuates between-trial movement corrections with abrupt changes that closely track the degree of sensory uncertainty but are insensitive to the magnitude and direction of movement error. This result marks a significant departure from existing findings and opens up new paths for future exploration.

Introduction

During episodes of sensorimotor control, sensory information about the current state of the body and environment are used to generate motor commands to achieve a desired goal. In an ideal world, this process would be implemented perfectly and result in error-free motor behaviour. In the real world, however, every stage of the sensorimotor control process is contaminated by noise [1] and uncertainty [2]. Despite this, humans achieve remarkably accurate and appropriate motor behaviour by harnessing two complementary processes for error correction. First, sensory feedback is rapidly integrated to adjust ongoing movements and compensate for sensed deviations from the planned movement [3, 4]. Second, over successive movements, feedforward motor plans, which map behavioural goals to the motor commands needed to accomplish those goals, are adapted in response to movement errors [5, 6]. Throughout this paper, we refer to the former as feedback integration and the latter as feedforward adaptation[7].

An important question that has attracted attention recently concerns how these error-correction processes are influenced by sensory uncertainty. To date, most studies either investigate feedback integration or feedforward adaptation, but not both. For example, in their pioneering study, Körding and Wolpert [8] had participants perform a variation on a standard visuomotor adaptation task and showed that visual feedback provided briefly at the midpoint of the reach drives movement corrections that are inversely proportional to the level of uncertainty in the sensory feedback. In other words, when uncertainty is high, sensory feedback information is integrated less to correct the ongoing reach (and reliance on prior knowledge increases) compared to when uncertainty is low. Several follow-up studies have made similar observations about the influence of sensory uncertainty on feedback integration [9, 10].

Studies investigating the feedforward adaptation component have similarly shown that adaptation rates inversely scale with sensory uncertainty such that increasing sensory uncertainty leads to smaller updates to the feedforward plan (slower adaptation) and vice versa [9, 11–13]. These studies use endpoint feedback only and in doing so prevent feedback integration, effectively isolating the feedforward component.

Importantly, because the majority of studies investigate these processes in isolation (but see section “Can paradigm differences explain our divergent results?” for a more nuanced discussion of Körding and Wolpert [8]), little is known about how sensory uncertainty influences feedback integration and feedforward adaptation when they co-occur—as they do in most natural movement contexts. For example, if highly uncertain sensory feedback leads to relatively small online corrections during a movement, does it also drive similar adaptive changes in feedforward motor plans? To our knowledge, no existing studies address this key question.

Here, we examine how sensory uncertainty influences feedforward adaptation and feedback integration when they co-occur. Our results indicate that (1) the presence of feedforward adaptation has little to no effect on how sensory uncertainty influences feedback integration, but (2) in the presence of feedback integration, sensory uncertainty appears to punctuate a slow and steady envelope of error reduction with large and abrupt changes to initial movement vectors that are insensitive to the magnitude and direction of the sensed movement error. This latter finding represents a significant departure from the existing literature, which consistently reports that sensory uncertainty inversely scales an error-dependent response.

Results

The overarching aim of our experiments was to determine how different levels of sensory uncertainty impact feedforward adaptation and feedback integration when they co-occur. Participants made planar reaching movements using visual feedback about their hand position provided immediately before movement onset and at midpoint (Experiment 1), or immediately before movement onset, at midpoint, and at endpoint (Experiment 2 and 3). See Figs 1 and 2 for details. We quantify our behavioural results using traditional statistical methods (see the “Statistical modelling” section for details) as well as by fitting state-space models that make explicit assumptions about how motor commands are planned, executed, and updated over time, as well as how these processes are modulated by sensory uncertainty (see section “State-space modelling” for details.)

Fig 1. Experimental apparatus and task structure.

Each participant made planar reaching movements while grasping the KINARM handle. A mirror system occluded vision of the hand and created the impression that the hand and visual targets were in the same plane. Red start target, green reach target, and white cursor feedback are shown.

Fig 2. Experimental protocols: Example adaptation phase trial conditions.

(A) Experiment 1: Midpoint-only feedback (large uncertainty). (B) Experiment 2: Matched midpoint and endpoint feedback (low uncertainty). (C) Experiment 3: Unmatched midpoint (moderate uncertainty) and endpoint (low uncertainty) feedback. Bottom, middle and top slides represent start, middle and end of reach respectively. coloured panels represent the possible uncertainty conditions (blue: σL, orange: σM, green: σH, red: σ∞). The example condition applied is outlined in black. In all experiments, a no-feedback washout phase followed the adaptation phase.

Experiment 1

Feedforward adaptation

Existing studies show that feedforward adaptation—when studied in the absence of feedback control—inversely scales with the level of uncertainty present in the sensory feedback [9, 11, 12, 14–17]. The primary contribution of Experiment 1 is to reveal how feedforward adaptation is influenced by sensory uncertainty when feedback integration is also engaged. To do this, we provided uncertain sensory feedback at movement midpoint (see Fig 2a), and omitted endpoint feedback entirely. We focused on uncertainty at midpoint because feedback integration can only occur if feedback is provided at some point before movement offset. Presenting feedback briefly at midpoint is the simplest possible design in which feedback integration and feedforward adaptation both co-occur.

Previous computational and experimental work suggests that when the motor system performs feedback control, the feedback controller itself can be used as a teaching signal to drive adaptation in the feedforward controller [18–23]. It is therefore possible that feedback integration of sensory uncertainty at midpoint prevents or otherwise alters the influence of sensory uncertainty on feedforward adaptation. To our knowledge, this prediction has never been directly tested. Consequently, another key contribution of this experiment is to provide a clear test of this common assumption of computational models of motor learning.

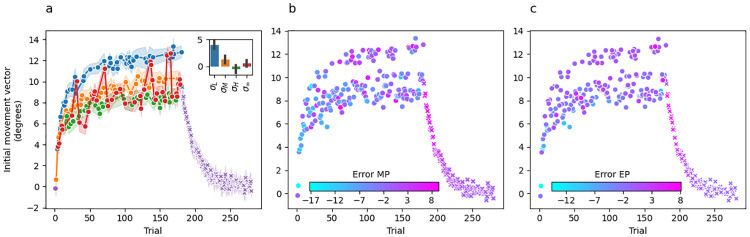

Fig 3 shows group-averaged initial movement vectors for Experiment 1. Panel A is colour coded such that the colour of the dot at trial t indicates the sensory uncertainty experienced at midpoint on trial t − 1. Recall that the trial sequence of perturbations and sensory uncertainty levels were matched across participants, which is a fundamental feature of our experimental design that makes this plot informative. Washout trials are shown in purple, but from the participant’s perspective they are identical to the unlimited uncertainty trials shown in red.

Fig 3. Experiment 1 mean initial movement vector across participants per trial.

(a) Dot colour for trial t represents the level of sensory uncertainty applied at midpoint on the previous trial t − 1. Performance during the washout phase is shown by purple x’s. The inset bar graph shows the mean difference between the last 10 trials of adaptation and the first 10 trials of washout plotted separately for each uncertainty level. Error bars are 95% confidence intervals. (b) Dot colour for trial t represents the error at reach midpoint on the same trial. (c) Dot colour for trial t represents the error at the reach endpoint on the previous trial t − 1.

There are several key takeaways from Fig 3a. First, the change in initial movement vectors across trials during the adaptation phase is in a direction that—on average—tends to reduce error towards an adaptation extent of 7.13±1.9° (59%), averaged over the last 10 trials. Second, initial movement vectors decay smoothly back to baseline during the washout phase. Together, these observations are consistent with the idea that changes in initial movement vector across trials are driven by an incremental error-driven adaptive process. Third, and perhaps most strikingly, there is a clear stratification across sensory uncertainty conditions indicating that sensory uncertainty at midpoint has a dramatic and systematic effect on the evolution of initial movement vectors across trials.

Recall that the perturbation experienced on trial t is on average 12° and therefore the error experienced on every trial should drive the subsequent trial’s initial movement vector in a more positive direction. Instead, we see changes in movement vectors across trials from a lower uncertainty level to a higher uncertainty level (e.g., σL → σM, σM → σH) that are in a direction leading to greater error on the subsequent trial. Considered the other way around, any change across trials from a higher to a lower uncertainty level (e.g., σM → σL, σH → σM) almost always results in a change in initial movement vector that is adaptive (i.e., in an error-reducing direction), but of a much greater magnitude than would be seen if the uncertainty level did not change at all. Motor noise is not a plausible explanation for this pattern because the correlation between the level of uncertainty on the previous trial and movement direction on the current trial is consistent both across the experiment for individual participants and also across all participants.

According to either of the above perspectives, the stratification in initial movement vectors based on the previous trial’s level of sensory uncertainty is difficult to reconcile with what is known about the incremental, error-driven nature of the implicit motor adaptation system. This naturally raises the question of whether the observed stratification reflects the process of motor adaptation at all, or may instead reflect the operation of some other system (e.g., whatever system is responsible for explicit aiming strategies [24]). Even though our paradigm was not designed to address this question, some insight can be gleaned by examining the no-feedback washout phase (shown in purple in Fig 3). For example, if initial movement vectors on low uncertainty trials (blue dots in Fig 3a) are an artifact of explicit aiming, there should be a large difference between the initial movement vectors observed for these trial types at the end of adaptation and those observed at the beginning of washout. Visual inspection of Fig 3 shows that this is indeed the case. To formalize this finding, we computed the difference between the mean accuracy achieved on the last 10 trials of the adaptation phase and the first 3 trials of the washout phase separately for each uncertainty trial type and separately for each subject. We used 3 washout trials instead of 10 in order to limit contamination from forgetting (i.e., the decay back to baseline seen during washout) which can lead to an underestimation of the initial washout state. A repeated-measures ANOVA indicated a significant difference in these difference scores across uncertainty trial types (). Posthoc paired t-tests corrected for multiple comparisons using the Bonferroni method (see Table 1) revealed that these difference scores were larger for the low uncertainty condition than they were for any other uncertainty condition. These difference scores were not significantly different between any of the other uncertainty trial conditions.

Table 1. Experiment 1 pairwise comparisons examining differences between uncertainty trial types in adaptation—washout difference scores.

A and B indicate the uncertainty trial types being compared; T is the observed t-statistic; dof is the degrees of freedom of the test; p-corr is the Bonferroni-corrected p-value; hedges is the Hedges G measure of effect size.

| row | A | B | T | dof | p-corr | hedges |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | σ L | σ M | 6.98 | 19.00 | 0.00 | 1.95 |

| 2 | σ L | σ H | 4.59 | 19.00 | 0.00 | 1.30 |

| 3 | σ L | σ ∞ | 7.01 | 19.00 | 0.00 | 1.86 |

| 4 | σ M | σ H | -2.18 | 19.00 | 0.25 | -0.53 |

| 5 | σ M | σ infty | 0.16 | 19.00 | 1.00 | 0.04 |

| 6 | σ H | σ infty | 2.25 | 19.00 | 0.22 | 0.51 |

Thus, the likely state of adaptation at the beginning of washout appears much more closely aligned with the adaptation estimated by initial movement vectors preceded by medium, high, and infinite uncertainty trials (orange, green, and red dots in Fig 3) than it does with the adaptation estimated by initial movement vectors preceded by low uncertainty trials (blue dots in Fig 3). This is consistent with the possibility that the blue dots in Fig 3a are the output of a process distinct from motor adaptation (see the “Adaptation vs aiming” subsection of the Discussion).

One small, apparent puzzle in our data is that several no-feedback trials (σ∞, in red) result in initial movement vectors on the subsequent trial that appear closely aligned with the low uncertainty trials (σL, in blue). These occur at trials 31, 71, 136, 137, 160 and 165 (Fig 3a). While this pattern could be due to noise, it is striking that out of these 6 trials, 5 are directly preceded by a low-uncertainty trial, and one (trial 137) is preceded by a no-feedback trial. Throughout adaptation, there are only 6 trial pairs where σL precedes σ∞ (trials [[3,4], [30,31], [70,71], [135,136], [159,160], [164,165]]). Thus, in all but the earliest case (trials [3, 4]) a no-feedback trial following a low-uncertainty trial had the same effect as a low-uncertainty trial on subsequent initial movement vectors, suggesting that no-feedback trials may simply preserve the behaviour from the previous trial.

Fig 3b colour codes initial movement vector by the error experienced at midpoint on the previous trial, and Fig 3c colour codes by the error experienced at endpoint. Since no visual feedback was provided at endpoint in this experiment, participants could only estimate endpoint error based on proprioceptive feedback. Interestingly, the stratification pattern observed when colour coding by sensory uncertainty is no longer evident in either of these panels. Overall, this suggests that sensory uncertainty, and not movement error, is responsible for the stratification of initial movement vector across trials.

We formalised these observations by fitting a regression model that treated initial movement vector as the observed variable. Predictor variables in this model were trial, the error experienced at midpoint/endpoint, and the sensory uncertainty experienced at midpoint/endpoint, and the interaction between the error terms and the sensory uncertainty terms. All error and sensory uncertainty predictors were taken from the previous trial. See the “Statistical modelling” section for more details.

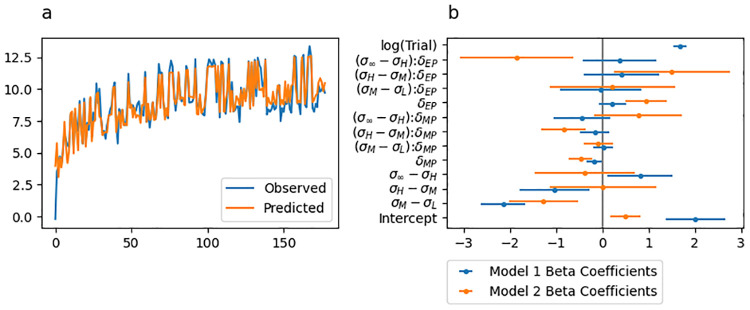

The predicted initial movement vectors from this regression model are shown in Fig 4a, with the best fitting beta coefficients along with their 95% confidence intervals shown by blue lines in Fig 4b. Table 2 includes all estimated beta coefficients and corresponds to the blue confidence intervals displayed in Fig 4b). The model was statistically significant (Adjusted R2 = 0.831, F(8,168) = 103.1, p < .001).

Fig 4. Experiment 1 linear regression fit to initial movement vector.

(a) Initial movement vector predictions from the regression model superimposed over the behavioural data. (b) Point and 95% confidence interval estimates from best fitting regression models. Coefficients of the regression for predicting initial movement vector are shown in blue and coefficients for predicting change in initial movement vector are shown in orange.

Table 2. Experiment 1 regression results for predicting initial movement vector from error and sensory uncertainty terms.

These results correspond to the blue confidence intervals displayed in Fig 3. The coef column contains β coefficients, the se column contains standard errors of these coefficients, the T column contains corresponding t-statistic, the pval column contains corresponding p-values, the CI[2.5%] and CI[97.5%] columns give the 95% confidence interval, and the relimp column gives the corresponding relative importance.

| row | names | coef | se | T | pval | CI[2.5%] | CI[97.5%] | relimp |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | β 0 | 1.06 | 0.29 | 3.69 | 0.00 | 0.50 | 1.63 | NaN |

| 2 | σM − σL | -1.95 | 0.23 | -8.52 | 0.00 | -2.41 | -1.50 | 0.17 |

| 3 | σH − σM | -0.95 | 0.24 | -3.93 | 0.00 | -1.43 | -0.47 | 0.07 |

| 4 | σ∞ − σH | 0.90 | 0.25 | 3.65 | 0.00 | 0.41 | 1.39 | 0.01 |

| 5 | δ MP | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.31 | 0.76 | -0.02 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| 6 | (σM − σL):δMP | -0.01 | 0.04 | -0.28 | 0.78 | -0.08 | 0.06 | 0.05 |

| 7 | (σH − σM):δMP | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.22 | 0.83 | -0.06 | 0.08 | 0.02 |

| 8 | (σ∞ − σH):δMP | 0.04 | 0.04 | 1.16 | 0.25 | -0.03 | 0.12 | 0.01 |

| 9 | log(Trial) | 1.33 | 0.06 | 21.68 | 0.00 | 1.20 | 1.45 | 0.47 |

Sensory uncertainty across all levels significantly predicted the initial movement vector on the following trial in a direction that inversely scaled with uncertainty (Table 2, rows 2–4). Initial movement vectors were significantly greater on trials following low sensory uncertainty than they were following moderate sensory uncertainty (σM − σL; Table 2, row 2) and they were significantly greater on trials following moderate sensory uncertainty than they were following high sensory uncertainty (σH − σM; Table 2, row 3). However, they were significantly lower on trials following high sensory uncertainty than they were following unlimited sensory uncertainty (σ∞ − σH; Table 2, row 4) possibly suggesting that the unlimited uncertainty condition should be treated in a qualitatively distinct fashion relative to the other uncertainty conditions. Error at midpoint (ϵMP; Table 2, row 5) was not a significant predictor of initial movement vector (but see the results from the regression below examining change in initial movement vector). Furthermore, no interaction term between midpoint error and sensory uncertainty was significant (Table 2, rows 6–8). Finally, log(Trial) significantly predicted initial movement vectors (Table 2, row 9), indicating that initial movement vectors tend to increase over the course of the adaptation phase.

The relative importance of the log(Trial) term in the regression model was 0.47, and the relative importance of the sum of uncertainty terms was 0.25. This indicates that the slow envelope of the adaptation curve is well captured by a simple logarithmic function, but that the effect of sensory uncertainty captures substantial variance. Overall, this regression analysis revealed a clear effect of sensory uncertainty that is independent of the error experienced at midpoint. We found no evidence that sensory uncertainty scales the response to movement error.

We also fit a regression model treating change in initial movement vector from trial to trial as the observed variable. Predictor variables for this model were identical to those described above, but with no predictor for trial. The best fitting beta coefficients along with their 95% confidence intervals are indicated by orange lines in Fig 4b. The model was statistically significant (Adjusted R2 = 0.445, F(7,169) = 19.33, p < .001).

An intuition for what this analysis should reveal emerges from careful inspection of Fig 5a, which depicts change in initial movement colour coded by the sensory uncertainty at midpoint on the previous trial. Here it is evident that change in initial movement vectors inversely tracks sensory uncertainty levels with the exception of the no feedback trials (σ∞). This result can be seen in the regression results by noting that change in initial movement vectors were significantly greater on trials following low sensory uncertainty than they were following moderate sensory uncertainty (σM − σL; Table 3, row 2), they were significantly greater on trials following moderate sensory uncertainty than they were following high sensory uncertainty (σH − σM; Table 3, row 3), and they were significantly less on trials following high sensory uncertainty than they were following total sensory uncertainty (σ∞ − σH; Table 3, row 4).

Fig 5. Experiment 1 change in initial movement vector and linear regression fits.

(a) Violin plot depicting in the distribution of mean changes in initial movement vector across all adaptation phase trials of the experiment separately for each uncertainty level. The inset of each violin shows a box plot in which the white dot indicates the median data value, the black box spans the 25% to 75% percentiles, and the whiskers extend to the most extreme data points. (b) Scatter plot showing the mean change in initial movement vector as a function of error experienced at midpoint. Lines indicate fitted simple linear regression lines. These regression lines do not correspond to the coefficients included in Table 3, rows 6–8) and are included only as a visual aid. colours indicate uncertainty level.

Table 3. Experiment 1 regression results for predicting change in initial movement vector from error and sensory uncertainty terms. These results correspond to the orange confidence intervals displayed in Fig 3.

The coef column contains β coefficients, the se column contains standard errors of these coefficients, the T column contains corresponding t-statistic, the pval column contains corresponding p-values, the CI[2.5%] and CI[97.5%] columns give the 95% confidence interval, and the relimp column gives the corresponding relative importance.

| row | names | coef | se | T | pval | CI[2.5%] | CI[97.5%] | relimp |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | β 0 | -0.32 | 0.13 | -2.39 | 0.02 | -0.59 | -0.06 | NaN |

| 2 | σM − σL | -1.44 | 0.37 | -3.92 | 0.00 | -2.16 | -0.71 | 0.17 |

| 3 | σH − σM | -1.52 | 0.39 | -3.93 | 0.00 | -2.29 | -0.76 | 0.12 |

| 4 | σ∞ − σH | 1.68 | 0.39 | 4.27 | 0.00 | 0.90 | 2.46 | 0.04 |

| 5 | δ MP | -0.08 | 0.02 | -3.80 | 0.00 | -0.12 | -0.04 | 0.04 |

| 6 | (σM − σL):δMP | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.93 | 0.35 | -0.06 | 0.17 | 0.07 |

| 7 | (σH − σM):δMP | -0.07 | 0.06 | -1.26 | 0.21 | -0.19 | 0.04 | 0.03 |

| 8 | (σ∞ − σH):δMP | 0.10 | 0.06 | 1.77 | 0.08 | -0.01 | 0.22 | 0.01 |

Further understanding of this effect can be built by examining Fig 5b, which depicts the change in initial movement vectors as a function of midpoint error. The lines in this plot represent simple linear regression lines (they are not the same multiple regression model described above) and are colour coded by sensory uncertainty. Note that if sensory uncertainty scales the response to error, the slope of the blue line (low uncertainty) should be the steepest, the slope of the orange line (moderate uncertainty) should be the next steepest, the slope of the green line (high uncertainty) should be the next steepest, and the slope of the red line should be the shallowest. Fig 5b does not show this pattern. See Table 3 rows 6–8 for statistics corresponding to the interaction between midpoint error and sensory uncertainty at midpoint. However, this analysis does reveal that midpoint error itself significantly contributes to predicting change in hand angle (Table 3 row 5). This can be seen in Fig 5b by noting that the overall trend of all regression lines is negative.

Overall, the results of this regression model (taking change in initial movement vector as the observed variable) largely echo the results of the regression model built with initial movement vector taken as the observed variable. Specifically, while midpoint error clearly influences the magnitude of hand angle change on the next trial, it does not interact with the level of sensory uncertainty. Furthermore, the sum of the relative importance of the sensory uncertainty predictors was much greater than that of midpoint error (0.33 vs 0.04). Thus, the main takeaway from these analyses is that both sensory uncertainty and movement error influence feedforward adaptation as estimated by initial movement vectors, but (1) they do so independently of each other, and (2) the effect of sensory uncertainty is more influential than the effect of movement error.

Feedback integration

Fig 6a shows feedback integration (i.e., the difference between midpoint and endpoint hand angles) as a function of sensory uncertainty at midpoint, and Fig 6b shows feedback integration as a function or error at midpoint coloured by sensory uncertainty. The main pattern observed in Fig 6 is that there are no significant differences in overall feedback integration depending on sensory uncertainty level (panel A), but there are large differences in how feedback integration responds to midpoint error depending on sensory uncertainty level (i.e., slope differences in panel B).

Fig 6. Experiment 1 feedback integration (endpoint hand angle—initial movement vector).

(a) Violin plot depicting the distribution of mean feedback integration across all adaptation phase trials of the experiment separately for each uncertainty level. The inset of each violin shows a box plot in which the white dot indicates the median data value, the black box spans the 25% to 75% percentiles, and the whiskers extend to the most extreme data points. (b) Scatter plot showing the mean feedback integration as a function of error experienced at midpoint. Lines indicate fitted linear regression lines, corresponding to the coefficients included in Table 4, rows 6–8). Point and line colour indicates uncertainty level.

We formalised these observations by fitting a regression model treating the difference between endpoint and midpoint hand angle as the observed variable. Predictor variables were the error experienced at midpoint, the sensory uncertainty experienced at midpoint, and the interaction between these two terms. In contrast to the regression models reported for feedforward adaptation, all error and sensory uncertainty predictors were taken from the current trial. This regression was statistically significant (Adjusted R2 = 0.905, F(7,169) = 241.5, p < .001). Beta coefficient estimates and corresponding statistics are listed in Table 4.

Table 4. Experiment 1 regression results for predicting feedback integration (endpoint hand angle—initial movement vector) from error and sensory uncertainty terms.

The coef column contains β coefficients, the se column contains standard errors of these coefficients, the T column contains corresponding t-statistic, the pval column contains corresponding p-values, the CI[2.5%] and CI[97.5%] columns give the 95% confidence interval, and the relimp column gives the corresponding relative importance.

| row | names | coef | se | T | pval | CI[2.5%] | CI[97.5%] | relimp |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | β 0 | -0.15 | 0.11 | -1.35 | 0.18 | -0.37 | 0.07 | NaN |

| 2 | σM − σL | 0.21 | 0.30 | 0.70 | 0.48 | -0.39 | 0.81 | 0.01 |

| 3 | σH − σM | -0.90 | 0.32 | -2.81 | 0.01 | -1.53 | -0.27 | 0.05 |

| 4 | σ∞ − σH | 0.78 | 0.32 | 2.41 | 0.02 | 0.14 | 1.42 | 0.05 |

| 5 | δ MP | -0.51 | 0.02 | -30.96 | 0.00 | -0.55 | -0.48 | 0.49 |

| 6 | (σM − σL):δMP | 0.33 | 0.05 | 7.03 | 0.00 | 0.23 | 0.42 | 0.05 |

| 7 | (σH − σM):δMP | 0.05 | 0.05 | 1.01 | 0.31 | -0.05 | 0.14 | 0.11 |

| 8 | (σ∞ − σH):δMP | 0.52 | 0.05 | 10.90 | 0.00 | 0.43 | 0.61 | 0.14 |

The most important result from this analysis is that the feedback integration response to increasing midpoint error (i.e., the slopes in Fig 6b) was significantly greater for low sensory uncertainty than it was for moderate uncertainty [(σM − σL) * ϵMP; Table 3 row 6], and was also significantly greater for high uncertainty than it was for unlimited uncertainty midpoint feedback [(σM − σL) * ϵMP; Table 3 row 8]. The difference between moderate and high uncertainty was non-significant [(σH − σM) * ϵMP; Table 3 row 7]. Overall, these results are consistent with prior studies showing that that sensory uncertainty has an error-scaling effect on feedback integration [8, 10].

Experiment 2

The results of Experiment 1 raise the possibility that the uncertainty of sensory feedback does not inversely scale the magnitude of the error-driven feedforward update as it does in an endpoint feedback-only paradigm [11–13, 15–17]. Rather, our analysis suggests that sensory uncertainty acts largely independently of the experienced error to induce large and abrupt changes in the adapted state that can be—in the case of a transition from a high uncertainty trial—in a direction opposite to the general adaptive trend.

These striking results suggest that the presence of feedback integration fundamentally alters how feedforward adaptation is affected by sensory uncertainty. However, another possibility is that feedforward adaptation is influenced by sensory uncertainty differently depending on the temporal proximity of the sensory feedback signal to movement offset, regardless of whether or not feedback integration occurred at the midpoint of the movement [25–27]. Experiment 2 tests this possibility by providing midpoint and endpoint feedback matched in their level of uncertainty (see Fig 2B).

Fig 7 shows group-averaged initial movement vectors per trial, colour coded such that the colour of the point at trial t indicates the sensory uncertainty experienced at midpoint on trial t − 1. The extent of adaptation was 9.69±2.18° (81%) averaged over the last 10 trials.

Fig 7. Experiment 2 mean initial movement vector across participants per trial.

(a) The colour of the dot on trial t represents the level of sensory uncertainty applied at midpoint on the previous trial t − 1. Performance during the washout phase is shown by purple x’s. The inset bar graph shows the mean difference between the last 10 trials of adaptation and the first 10 trials of washout plotted separately for each uncertainty level. Error bars are 95% confidence intervals. (b) The colour of the dots on trial t represents the error at the reach midpoint on the same trial. (c) The colour of the dots on trial t represents the error at the reach endpoint on the previous trial t − 1.

Feedforward adaptation

In terms of sensory uncertainty scaling, the same basic pattern observed in Experiment 1 (i.e. Fig 3) is present here as well. Specifically, the trial-by-trial variation in initial movement vector is large, but cannot be attributed to noise because there is a clear stratification in how a particular uncertainty level influences the subsequent trial. Even with the inclusion of congruent endpoint feedback, sensory uncertainty on trial t − 1 continues to exert a powerful effect on the subsequent initial movement vector.

As was already discussed for Experiment 1, a natural question arises about whether this stratification reflects implicit motor adaptation or some other process such as explicit aiming strategies [24]). We therefore followed the same logic as before and performed the same analysis outlined above. In particular, we computed the difference between the mean accuracy achieved on the last 10 trials of the adaptation phase and the first 3 trials of the washout phase separately for each uncertainty trial type and separately for each subject. A repeated-measures ANOVA indicated that there was a significant difference in these difference scores across uncertainty trial types (). Posthoc paired t-tests corrected for multiple comparisons using the Bonferroni method (see Table 5) revealed that these difference scores were larger for the low uncertainty condition than they were for any other uncertainty condition. Additionally, the difference scores for the high uncertainty trial type (green dots in Fig 7a) were significantly smaller than those for the infinite uncertainty trial type (red dots in Fig 7a). These difference scores were not significantly different between any of the other uncertainty trial conditions.

Table 5. Experiment 2 pairwise comparisons examining differences between uncertainty trial types in adaptation—washout difference scores.

A and B indicate the uncertainty trial types being compared; T is the observed t-statistic; dof is the degrees of freedom of the test; p-corr is the Bonferroni-corrected p-value; hedges is the Hedges G measure of effect size.

| row | A | B | T | dof | p-corr | hedges |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | σ L | σ M | 10.61 | 19.00 | 0.00 | 2.06 |

| 2 | σ L | σ H | 7.11 | 19.00 | 0.00 | 1.56 |

| 3 | σ L | σ ∞ | 10.53 | 19.00 | 0.00 | 2.49 |

| 4 | σ M | σ H | -2.43 | 19.00 | 0.15 | -0.42 |

| 5 | σ M | σ infty | 2.92 | 19.00 | 0.05 | 0.64 |

| 6 | σ H | σ infty | 4.77 | 19.00 | 0.00 | 0.99 |

As seen in Experiment 1, this is consistent with the idea that the likely state of adaptation at the beginning of washout is more closely aligned with the adaptation estimated by initial movement vectors preceded by medium, high, and unlimited uncertainty trials (orange, green, and red dots in Fig 7a) than it does with the adaptation estimated by initial movement vectors preceded by low uncertainty trials (blue dots in Fig 7a). In this case, adaptation appears most aligned with the level estimated by high uncertainty trials. These findings are consistent with the possibility that the blue dots in Fig 7a are the output of a process distinct from motor adaptation (see the “Adaptation vs aiming” subsection of the Discussion).

Fig 7b and 7c depict initial movement vector colour coded by the error experienced at midpoint or endpoint, respectively. As in Experiment 1, these panels show a clear pattern of stratification by sensory uncertainty and no stratification by movement error, suggesting that sensory uncertainty (and not movement error) is responsible for the stratification of initial movement vector observed across trials. As in Experiment 1, the no-feedback trials (σ∞, in red) that follow low-uncertainty trials (σL, in blue) have the same effect on subsequent initial movement vectors as a low uncertainty trial, again suggesting that no-feedback trials may preserve the behaviour from the previous trial.

We fit a regression model of the same form as that reported for Experiment 1 (see also the “Statistical modelling” section). The predicted initial movement vectors from this regression model is shown in Fig 8a and the best fitting beta coefficients along with their 95% confidence intervals are shown by blue lines in Fig 8b. Table 6 includes all estimated beta coefficients and corresponds to the blue confidence intervals displayed in Fig 8b). The model was statistically significant (Adjusted R2 = 0.845, F(12,165) = 81.17, p < .001).

Fig 8. Experiment 2 linear regression fit to initial movement vector.

(a) Initial movement vector predictions from the regression model superimposed over the behavioural data. (b) Point and 95% confidence interval estimates from best fitting regression models. Coefficients of the regression for predicting initial movement vector are shown in blue and coefficients for predicting change in initial movement vector are shown in orange.

Table 6. Experiment 2 regression results for predicting initial movement vector from error and sensory uncertainty terms.

These results correspond to the blue confidence intervals displayed in Fig 8. The coef column contains β coefficients, the se column contains standard errors of these coefficients, the T column contains corresponding t-statistic, the pval column contains corresponding p-values, the CI[2.5%] and CI[97.5%] columns give the 95% confidence interval, and the relimp column gives the corresponding relative importance.

| row | names | coef | se | T | pval | CI[2.5%] | CI[97.5%] | relimp |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | β 0 | 2.01 | 0.33 | 6.12 | 0.00 | 1.36 | 2.66 | NaN |

| 2 | σM − σL | -2.15 | 0.25 | -8.76 | 0.00 | -2.64 | -1.67 | 0.14 |

| 3 | σH − σM | -1.05 | 0.38 | -2.74 | 0.01 | -1.81 | -0.29 | 0.07 |

| 4 | σ∞ − σH | 0.81 | 0.36 | 2.25 | 0.03 | 0.10 | 1.52 | 0.01 |

| 5 | δ MP | -0.17 | 0.08 | -2.10 | 0.04 | -0.34 | -0.01 | 0.03 |

| 6 | (σM − σL):δMP | 0.01 | 0.11 | 0.14 | 0.89 | -0.19 | 0.22 | 0.01 |

| 7 | (σH − σM):δMP | -0.17 | 0.16 | -1.05 | 0.29 | -0.48 | 0.15 | 0.01 |

| 8 | (σ∞ − σH):δMP | -0.45 | 0.31 | -1.44 | 0.15 | -1.07 | 0.17 | 0.01 |

| 9 | δ EP | 0.21 | 0.15 | 1.38 | 0.17 | -0.09 | 0.50 | 0.05 |

| 10 | (σM − σL):δEP | -0.04 | 0.45 | -0.09 | 0.92 | -0.92 | 0.84 | 0.03 |

| 11 | (σH − σM):δEP | 0.41 | 0.42 | 0.98 | 0.33 | -0.41 | 1.23 | 0.02 |

| 12 | (σ∞ − σH):δEP | 0.37 | 0.40 | 0.91 | 0.37 | -0.43 | 1.16 | 0.01 |

| 13 | log(Trial) | 1.68 | 0.07 | 23.32 | 0.00 | 1.54 | 1.82 | 0.47 |

As in Experiment 1, sensory uncertainty across all levels significantly predicted the initial movement vector on the following trial in a direction that inversely scaled with uncertainty (Table 6, rows 2–4). Initial movement vectors were significantly greater on trials following low sensory uncertainty than they were following moderate sensory uncertainty (σM − σL; Table 6, row 2) and they were significantly greater on trials following moderate sensory uncertainty than they were following high sensory uncertainty (σH − σM; Table 6, row 3). However, they were significantly smaller on trials following high sensory uncertainty than they were following total sensory uncertainty (σ∞ − σH; Table 6, row 4), possibly suggesting that total uncertainty is playing a qualitatively distinct role here than that for the other uncertainty conditions.

Error at midpoint (ϵMP; Table 6, row 5), but not error at endpoint (ϵMP; Table 6, row 9), was a significant predictor of initial movement vector. Importantly, no interaction terms between midpoint/endpoint error and sensory uncertainty (Table 6 rows 6–8 and 10–12) were significant. Finally, log(Trial) significantly predicted initial movement vectors (6, row 13), indicating the trend of initial movement vectors to increase over the course of the adaptation phase. The relative importance of the log(Trial) term was 0.47, that for the sum of uncertainty terms was 0.22, and that for the midpoint error (δMP) term was 0.03. This suggests that the dominant source of variance is largely captured by the slow envelope of adaptation, but also shows that sensory uncertainty plays an important role.

Overall, this regression echoed the results of Experiment 1 in revealing (1) both error and sensory uncertainty influence adaptation, but (2) they exert their influences independently of each other. We therefore failed to find any evidence that sensory uncertainty scales the response to movement error.

We also fit a regression model treating change in initial movement vector as the observed variable. Predictor variables for this model were identical to those described above, but with no trial predictor. The best fitting betas along with their 95% confidence intervals is shown by the orange lines in Fig 4b. The model was statistically significant (Adjusted R2 = 0.522, F(11,166) = 18.54, p < .001).

A strong expectation for what this analysis should reveal can be built with careful inspection of Fig 9a, which depicts change in initial movement colour coded by the sensory uncertainty at midpoint on the previous trial. Here it is clear that change in initial movement vectors inversely tracks sensory uncertainty levels with the exception of the no feedback trials (σ∞). This result can be seen in the regression results by noting that change in initial movement vectors were significantly greater on trials following low sensory uncertainty than they were following moderate sensory uncertainty (σM − σL; Table 7, row 2). However, they were not significantly greater on trials following moderate sensory uncertainty than they were following high sensory uncertainty (σH − σM; Table 7, row 3), nor were they significantly greater on trials following high sensory uncertainty than they were following unlimited sensory uncertainty (σ∞ − σH; Table 7, row 4). Thus, while the clear trend is for stratification according to sensory uncertainty, only the low uncertainty comparison reached significance.

Fig 9. Experiment 2 change in initial movement vector and linear regression fits.

(a) Violin plot depicting the distribution of mean changes in initial movement vector across all adaptation phase trials of the experiment separately for each midpoint/endpoint uncertainty combination, colour coded as per Fig 6a. The inset of each violin shows a box plot in which the white dot indicates the median data value, the black box spans the 25% to 75% percentiles, and the whiskers extend to the most extreme data points. (b) Scatter plot showing the mean change in initial movement vector as a function of error experienced at midpoint. Point and line colour indicates uncertainty level. (c) Scatter plot showing the mean change in initial movement vector as a function of error experienced at endpoint on the previous trial. Point and line colour indicates uncertainty level. The lines in panel B and C indicate fitted simple linear regression lines. These regression lines do not correspond to the coefficients included in Table 7) and are included only as a visual aid.

Table 7. Experiment 2 regression results for predicting change in initial movement vector from error and sensory uncertainty terms.

These results correspond to the orange confidence intervals displayed in Fig 8. The coef column contains β coefficients, the se column contains standard errors of these coefficients, the T column contains corresponding t-statistic, the pval column contains corresponding p-values, the CI[2.5%] and CI[97.5%] columns give the 95% confidence interval, and the relimp column gives the corresponding relative importance.

| row | names | coef | se | T | pval | CI[2.5%] | CI[97.5%] | relimp |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | β 0 | 0.49 | 0.17 | 2.95 | 0.00 | 0.16 | 0.82 | NaN |

| 2 | σM − σL | -1.28 | 0.38 | -3.40 | 0.00 | -2.02 | -0.54 | 0.14 |

| 3 | σH − σM | 0.01 | 0.59 | 0.02 | 0.98 | -1.15 | 1.17 | 0.11 |

| 4 | σ∞ − σH | -0.38 | 0.55 | -0.69 | 0.49 | -1.47 | 0.71 | 0.02 |

| 5 | δ MP | -0.48 | 0.13 | -3.76 | 0.00 | -0.73 | -0.23 | 0.06 |

| 6 | (σM − σL):δMP | -0.09 | 0.16 | -0.58 | 0.57 | -0.41 | 0.23 | 0.02 |

| 7 | (σH − σM):δMP | -0.84 | 0.24 | -3.44 | 0.00 | -1.32 | -0.36 | 0.03 |

| 8 | (σ∞ − σH):δMP | 0.77 | 0.48 | 1.60 | 0.11 | -0.18 | 1.72 | 0.03 |

| 9 | δ EP | 0.94 | 0.23 | 4.06 | 0.00 | 0.48 | 1.40 | 0.04 |

| 10 | (σM − σL):δEP | 0.21 | 0.69 | 0.31 | 0.76 | -1.15 | 1.57 | 0.02 |

| 11 | (σH − σM):δEP | 1.50 | 0.64 | 2.35 | 0.02 | 0.24 | 2.76 | 0.02 |

| 12 | (σ∞ − σH):δEP | -1.85 | 0.62 | -2.99 | 0.00 | -3.07 | -0.63 | 0.04 |

Further intuitions can be built by examining Fig 9b, which depicts the change in initial movement vectors as a function of midpoint error. The lines in this plot are colour coded by sensory uncertainty. Fig 9c shows essentially the same information but for endpoint instead of midpoint error. Note that if sensory uncertainty scales the response to error, then the slope of the blue line (low uncertainty) should be the steepest, the slope of the orange line (moderate uncertainty) should be the next steepest, the slope of the green line (high uncertainty) should be the next steepest, and the slope of the red line should be the shallowest. Neither Fig 5b nor Fig 9c show this pattern. See Table 7 rows 6–8 for statistics corresponding to midpoint error, and rows 10–12 for statistics corresponding to endpoint error.

Overall, the results of this regression (using change in initial movement vector as the observed variable) echo the results of the regression modelling using initial movement vector as the observed variable. Furthermore, the results from both regression models are aligned with those from Experiment 1. Specifically, there appears to be a clear error-independent effect of sensory uncertainty—albeit less pronounced statistically then in the results from Experiment 1. Importantly, we find no evidence that sensory uncertainty scales the response to movement error.

Feedback integration

Fig 10a shows feedback integration (i.e., the difference between endpoint and midpoint hand angle) as a function of sensory uncertainty at midpoint, and Fig 10b shows feedback integration as a function or error at midpoint coloured by sensory uncertainty. The main pattern observed in Fig 10 is that there are no significant differences in overall feedback integration depending on sensory uncertainty level (panel A), but there are large differences in how feedback integration responds to midpoint error depending on sensory uncertainty level (i.e., slope differences in panel B).

Fig 10. Experiment 2 feedback integration (endpoint hand angle—initial movement vector).

(a) Violin plot depicting the distribution of mean feedback integration across all adaptation phase trials of the experiment separately for each uncertainty level. The inset of each violin shows a box plot in which the white dot indicates the median data value, the black box spans the 25% to 75% percentiles, and the whiskers extend to the most extreme data points. (b) Scatter plot showing the mean feedback integration as a function of error experienced at midpoint. Lines indicate fitted linear regression lines, corresponding to the coefficients included in Table 8, rows 6–8). Point and line colour indicates uncertainty level.

We formalised these observations by fitting a regression model treating the difference between endpoint and midpoint hand angle as the observed variable. Predictor variables were the error experienced at midpoint, the sensory uncertainty experienced at midpoint, and the interaction between these two terms. In contrast to the regression models reported for feedforward adaptation, all error and sensory uncertainty predictors were taken from the current trial. This regression was statistically significant (Adjusted R2 = 0.911, F(7,170) = 258.7, p < .001). Beta coefficient estimates and corresponding statistics are listed in Table 8.

Table 8. Experiment 2 regression results for predicting feedback integration (endpoint hand angle—initial movement vector) from error and sensory uncertainty terms.

The coef column contains β coefficients, the se column contains standard errors of these coefficients, the T column contains corresponding t-statistic, the pval column contains corresponding p-values, the CI[2.5%] and CI[97.5%] columns give the 95% confidence interval, and the relimp column gives the corresponding relative importance.

| row | names | coef | se | T | pval | CI[2.5%] | CI[97.5%] | relimp |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | β 0 | -0.26 | 0.08 | -3.40 | 0.00 | -0.41 | -0.11 | NaN |

| 2 | σM − σL | -0.16 | 0.21 | -0.74 | 0.46 | -0.58 | 0.26 | 0.01 |

| 3 | σH − σM | -0.85 | 0.22 | -3.83 | 0.00 | -1.28 | -0.41 | 0.02 |

| 4 | σ∞ − σH | 1.11 | 0.22 | 5.02 | 0.00 | 0.67 | 1.55 | 0.02 |

| 5 | δ MP | -0.50 | 0.01 | -34.78 | 0.00 | -0.53 | -0.47 | 0.60 |

| 6 | (σM − σL):δMP | 0.34 | 0.04 | 8.54 | 0.00 | 0.26 | 0.42 | 0.05 |

| 7 | (σH − σM):δMP | -0.02 | 0.04 | -0.45 | 0.65 | -0.10 | 0.06 | 0.08 |

| 8 | (σ∞ − σH):δMP | 0.59 | 0.04 | 14.10 | 0.00 | 0.50 | 0.67 | 0.14 |

The most important result from this analysis is that the response of feedback integration to increasing midpoint error (i.e., the slopes in Fig 10b) was significantly greater for low sensory uncertainty than it was for moderate uncertainty [(σM − σL) * ϵMP; Table 8 row 6], and was also significantly greater for high uncertainty than it was for totally uncertain midpoint feedback [(σM − σL) * ϵMP; Table 8 row 8]. The difference between moderate and high uncertainty was non-significant [(σH − σM) * ϵMP; Table 8 row 7].

Overall, the pattern of feedback integration seen in Experiment 2 are qualitatively identical to those observed in Experiment 1. Both are consistent with prior studies showing that that sensory uncertainty has an error-scaling effect on feedback integration [8, 10].

Experiment 3

In Experiment 3, we sought to further probe how sensory uncertainty influences feedback and feedforward control processes. In particular, Experiment 3 disassociates the sensory uncertainty experienced at midpoint from that experienced at endpoint (see Fig 2c). This allows us to investigate if sensory uncertainty at midpoint dominates sensory uncertainty at endpoint (as might be expected due to the feedback correction made at that time point), or if endpoint dominates midpoint (as might be expected due to its temporal proximity to movement offset) [25, 27].

Fig 11a shows group-averaged initial movement vectors per trial colour coded such that the colour of the point at trial t indicates the midpoint and endpoint sensory uncertainty combinations (σLL, σLH, σHL, σHH) experienced on trial t − 1. Mean adaptation extent over the last 10 trials was 11.91±2.29° (99%). There is a clear stratification between trial types according to endpoint uncertainty, regardless of midpoint uncertainty. Furthermore, similar to Experiment 1 and 2, we see that in the transition from lower endpoint uncertainty trials to higher endpoint uncertainty trials (e.g., σLL → σLH; σHL → σHH) the change in movement vector is in a direction that tends to increase error on the subsequent trial.

Fig 11. Experiment 3 mean initial movement vector across participants per trial.

(a) The colour of the dot on trial t represents the combination of sensory uncertainty applied at midpoint and endpoint on the previous trial t − 1. Specifically, σLL in blue, σLH in orange, σHL in green, and σHH in red. Performance during the washout phase is shown by purple x’s. The inset bar graph shows the mean difference between the last 10 trials of adaptation and the first 10 trials of washout plotted separately for each trial type. Error bars are 95% confidence intervals. (b) The colour of the dots on trial t represents the error at the reach midpoint on the previous trial t − 1. (c) The colour of the dots on trial t represents the error at the reach endpoint on the previous trial t − 1.

Feedforward adaptation

As noted in the Results section of Experiment 1 and 2, it is possible that the stratification of initial movement vector by endpoint hand angle reflects implicit adaptation in the motor system. But it is also possible that it reflects the operation of some other system or process such as explicit aiming strategies [24]. We therefore followed the same logic and performed the same analysis outlined in earlier sections for those experiments. Visual inspection of Fig 11a reveals that initial movement vectors at the beginning of washout are closely matched to those observed at the end of adaptation for the trial types containing high uncertainty at endpoint. To formalise this observation, we computed the difference between the mean accuracy achieved on the last 10 trials of the adaptation phase and the first 3 trials of the washout phase separately for each uncertainty trial type and separately for each subject. A repeated-measures ANOVA indicated that there was a significant difference in these difference scores across uncertainty trial types (). Posthoc paired t-tests corrected for multiple comparisons using the bonferoni method (see Table 9) revealed that these difference scores were larger for trials in high high uncertainty was provided at endpoint than for trials in which low uncertainty was provided at endpoint. The uncertainty provided at midpoint did not make difference.

Table 9. Experiment 3 pairwise comparisons examining differences between uncertainty trial types in adaptation—washout difference scores.

A and B indicate the uncertainty trial types being compared; T is the observed t-statistic; dof is the degrees of freedom of the test; p-corr is the Bonferroni-corrected p-value; hedges is the Hedges G measure of effect size.

| row | A | B | T | dof | p-corr | hedges |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | σ L | σ M | 3.39 | 19.00 | 0.02 | 0.78 |

| 2 | σ L | σ H | -1.03 | 19.00 | 1.00 | -0.25 |

| 3 | σ L | σ ∞ | 4.19 | 19.00 | 0.00 | 0.98 |

| 4 | σ M | σ H | -5.33 | 19.00 | 0.00 | -1.29 |

| 5 | σ M | σ infty | 0.62 | 19.00 | 1.00 | 0.13 |

| 6 | σ H | σ infty | 9.87 | 19.00 | 0.00 | 1.71 |

These findings are consistent with the idea that the likely state of adaptation at the beginning of washout is more closely aligned with the adaptation estimated by initial movement vectors preceded by high endpoint uncertainty trials (orange and red dots in Fig 11a) than it does with the adaptation estimated by initial movement vectors preceded by low endpoint uncertainty trials (blue and green dots in Fig 11a). Thus, the adaptation envelope seen with low uncertainty trials may reflect the output of a process distinct from motor adaptation (see the “Adaptation vs aiming” subsection for further discussion).

Fig 11b and 11c depict initial movement vector colour coded by the error experienced at midpoint or endpoint, respectively. As in Experiment 1 and 2, these panels show that the stratification seen when colour coding by sensory uncertainty trial type is not present when colour coding by error, and suggests that sensory uncertainty and not movement error is responsible for the striation of initial movement vector across trials.

We formalised these observations by fitting a regression model of the same form as that reported in Experiment 1 and 2 (see also the “Statistical modelling” section). The predicted initial movement vectors from this regression model is shown in Fig 12a and the best fitting betas along with their 95% confidence intervals is shown by blue lines in Fig 12b. Table 10 includes all estimated beta coefficients and corresponds to the blue confidence intervals displayed in Fig 8b). The model was statistically significant (Adjusted R2 = 0.917, F(12,165) = 163.2, p < .001).

Fig 12. Experiment 3 linear regression fit to initial movement vector.

(a) Initial movement vector predictions from the regression model superimposed over the behavioural data. (b) Point and 95% confidence interval estimates from best fitting regression models. Coefficients of the regression for predicting initial movement vector are shown in blue and coefficients for predicting change in initial movement vector are shown in orange.

Table 10. Experiment 3 regression results for predicting initial movement vector from error and sensory uncertainty terms.

These results correspond to the blue confidence intervals displayed in Fig 12. The coef column contains β coefficients, the se column contains standard errors of these coefficients, the T column contains corresponding t-statistic, the pval column contains corresponding p-values, the CI[2.5%] and CI[97.5%] columns give the 95% confidence interval, and the relimp column gives the corresponding relative importance.

| row | names | coef | se | T | pval | CI[2.5%] | CI[97.5%] | relimp |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | β 0 | 2.97 | 0.23 | 13.00 | 0.00 | 2.51 | 3.42 | NaN |

| 2 | σLH − σLL | -2.45 | 0.13 | -19.39 | 0.00 | -2.70 | -2.20 | 0.16 |

| 3 | σHL − σLH | 2.21 | 0.30 | 7.37 | 0.00 | 1.62 | 2.80 | 0.02 |

| 4 | σHH − σHL | -2.20 | 0.38 | -5.79 | 0.00 | -2.95 | -1.45 | 0.06 |

| 5 | δ MP | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.22 | 0.83 | -0.05 | 0.06 | 0.02 |

| 6 | (σLH − σLL):δMP | -0.05 | 0.04 | -1.25 | 0.21 | -0.14 | 0.03 | 0.00 |

| 7 | (σHL − σLH):δMP | 0.01 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.93 | -0.15 | 0.16 | 0.01 |

| 8 | (σHH − σHL):δMP | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.58 | 0.56 | -0.14 | 0.25 | 0.02 |

| 9 | δ EP | -0.06 | 0.12 | -0.52 | 0.60 | -0.29 | 0.17 | 0.01 |

| 10 | (σLH − σLL):δEP | 0.24 | 0.33 | 0.73 | 0.47 | -0.41 | 0.88 | 0.01 |

| 11 | (σHL − σLH):δEP | -0.07 | 0.34 | -0.21 | 0.83 | -0.74 | 0.60 | 0.01 |

| 12 | (σHH − σHL):δEP | -0.16 | 0.33 | -0.50 | 0.62 | -0.81 | 0.48 | 0.05 |

| 13 | log(Trial) | 1.72 | 0.05 | 33.82 | 0.00 | 1.62 | 1.82 | 0.56 |

As in Experiment 1 and 2, sensory uncertainty across all conditions significantly influenced the initial movement vector on the following trial. Here, this influence was to increase initial movement vectors after low uncertainty at endpoint and to decrease them after high uncertainty at endpoint (Table 10, rows 2–4). Initial movement vectors were significantly greater on trials following low endpoint sensory uncertainty than they were following high endpoint sensory uncertainty (σLH − σLL and σHH − σHL; Table 10, rows 2 and 4). Neither error at midpoint (ϵMP; Table 10, row 5) nor error at endpoint (ϵEP; Table 10, row 9) were significant predictors of initial movement vector. Importantly, no interaction terms between midpoint/endpoint error and sensory uncertainty (Table 10 rows 6–8 and 10–12) were significant. Finally, log(Trial) significantly predicted initial movement vectors (Table 10, row 13), indicating the trend of initial movement vectors to increase over the course of the adaptation phase. As in Experiment 1 and 2 the relative importance of the log(Trial) term was 0.56 and the sum of the relative importance of the uncertainty terms was 0.24 indicating that both captured important variance in the data.

Overall, this regression echoed the results of Experiments 1 and 2, revealing that the effect of sensory uncertainty on feedforward adaptation is independent of movement error and failing to provide any evidence that sensory uncertainty scales the response to movement error.

We also fit a regression model treating change in initial movement vector as the observed variable. Predictor variables for this model were identical to those described above but with no trial predictor. The best fitting betas along with their 95% confidence intervals is shown by the orange lines in Fig 12b. The model was statistically significant (Adjusted R2 = 0.507, F(11,166) = 17.56, p < .001).

A strong intuition for what this analysis ought to reveal can be built with careful inspection of Fig 13a, which depicts change in initial movement colour coded by the sensory uncertainty at midpoint on the previous trial. Here it is clear that change in initial movement vectors inversely tracks sensory uncertainty levels at endpoint. This result can be seen in the regression results by noting that change in initial movement vectors were significantly smaller following σHH and σLH trials than they were following σHL and σLL trials (Table 11, row 2–4).

Fig 13. Experiment 3 change in initial movement vector and linear regression fits.

(a) Violin plot depicting the distribution of mean changes in initial movement vector across all adaptation phase trials of the experiment separately for each midpoint/endpoint uncertainty combination, colour coded as per Fig 11a. The inset of each violin shows a box plot in which the white dot indicates the median data value, the black box spans the 25% to 75% percentiles, and the whiskers extend to the most extreme data points. (b) Scatter plot showing the mean change in initial movement vector as a function of error experienced at midpoint. Point and line colour indicates uncertainty level. (c) Scatter plot showing the mean change in initial movement vector as a function of error experienced at endpoint on the previous trial. The lines in panel B and C indicate fitted simple linear regression lines. These regression lines do not correspond to the coefficients included in Table 11) and are included only as a visual aid.

Table 11. Experiment 3 regression results for predicting change in initial movement vector from error and sensory uncertainty terms.

These results correspond to the orange confidence intervals displayed in Fig 12. The coef column contains β coefficients, the se column contains standard errors of these coefficients, the T column contains corresponding t-statistic, the pval column contains corresponding p-values, the CI[2.5%] and CI[97.5%] columns give the 95% confidence interval, and the relimp column gives the corresponding relative importance.

| row | names | coef | se | T | pval | CI[2.5%] | CI[97.5%] | relimp |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | β 0 | 0.47 | 0.21 | 2.25 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.88 | NaN |

| 2 | σLH − σLL | -2.49 | 0.27 | -9.36 | 0.00 | -3.02 | -1.97 | 0.23 |

| 3 | σHL − σLH | 3.52 | 0.62 | 5.69 | 0.00 | 2.30 | 4.74 | 0.05 |

| 4 | σHH − σHL | -2.94 | 0.79 | -3.70 | 0.00 | -4.50 | -1.37 | 0.08 |

| 5 | δ MP | -0.24 | 0.06 | -4.28 | 0.00 | -0.35 | -0.13 | 0.05 |

| 6 | (σLH − σLL):δMP | -0.03 | 0.09 | -0.37 | 0.71 | -0.21 | 0.14 | 0.00 |

| 7 | (σHL − σLH):δMP | -0.34 | 0.16 | -2.09 | 0.04 | -0.66 | -0.02 | 0.01 |

| 8 | (σHH − σHL):δMP | 0.27 | 0.20 | 1.30 | 0.19 | -0.14 | 0.67 | 0.02 |

| 9 | δ EP | 0.58 | 0.24 | 2.38 | 0.02 | 0.10 | 1.05 | 0.02 |

| 10 | (σLH − σLL):δEP | -0.27 | 0.69 | -0.39 | 0.70 | -1.62 | 1.09 | 0.01 |

| 11 | (σHL − σLH):δEP | 1.33 | 0.71 | 1.88 | 0.06 | -0.07 | 2.72 | 0.01 |

| 12 | (σHH − σHL):δEP | -0.83 | 0.68 | -1.21 | 0.23 | -2.18 | 0.52 | 0.06 |

Further intuitions can be built by examining Fig 13b, which depicts the change in initial movement vectors as a function of midpoint error. The lines in this plot are colour coded by sensory uncertainty trial type. Fig 13c shows essentially the same information but for endpoint instead of midpoint error.

First note that every line across both of these plots has a negative slope indicating a general trend for both error sources to drive changes in initial movement vector. This is reflected in Table 11, rows 5 and 9 which show that both error at midpoint (δMP) and error at endpoint (δEP) are significant. Note that since the coefficient for midpoint error is negative, it drives changes in initial movement veector that reduce midpoint error on the next trial. However, note that the coefficient for endpoint error is positive, indicating that it drives changes in initial movement vector that increase error at endpoint on the next trial. Here we elect to not speculate too deeply into this finding given that the relative importance of these two terms was only 0.05 and 0.02.

Importantly, if sensory uncertainty at endpoint scales the response to error, then the slope of the blue and green lines (σLL and σHL) should be the steepest, and the slope of the orange and red lines (σLH and σHH) should be shallowest. Neither Fig 13b nor Fig 13c show this pattern. See Table 11 rows 6–8 for statistics corresponding to the interaction between sensory uncertainty with midpoint error, and rows 10–12 for statistics corresponding to the interaction between sensory uncertainty and endpoint error. Of these, only the (σHL − σLH):δMP term was significant and the relative importance of this term was only 0.01. On the other hand, the sum of the relative importance of sensory uncertainty terms was 0.36.

Overall, the results of this regression show that while both sensory uncertainty and movement error influence feedforward adaptation, they do so independently of each other. Furthermore, the influence of sensory uncertainty appears to outweigh the influence of movement error. Finally, like before, we find no evidence that sensory uncertainty scales the response to movement error.

Feedback integration

Fig 14a shows feedback integration (i.e., the difference between endpoint and midpoint hand angle) as a function of sensory uncertainty at midpoint, and Fig 14b shows feedback integration as a function of error at midpoint coloured by sensory uncertainty. The main pattern observed in Fig 14 is that there are no significant differences in overall feedback integration depending on sensory uncertainty level (panel A), but there are large differences in how feedback integration responds to midpoint error depending on sensory uncertainty level (i.e., slope differences in panel B).

Fig 14. Experiment 3 feedback integration (endpoint hand angle—initial movement vector).

(a) Violin plot depicting the distribution of mean feedback integration across all adaptation phase trials of the experiment separately for each midpoint uncertainty level. The inset of each violin shows a box plot in which the white dot indicates the median data value, the black box spans the 25% to 75% percentiles, and the whiskers extend to the most extreme data points. (b) Scatter plot showing the mean feedback integration as a function of error experienced at midpoint. Lines indicate fitted linear regression lines, corresponding to the coefficients included in Table 12, row 4). Point and line colour indicates uncertainty level.

We formalised these observations by fitting a regression model treating the difference between endpoint and midpoint hand angle as the observed variable. Predictor variables were the error experienced at midpoint, the sensory uncertainty experienced at midpoint, and the interaction between these two terms. In contrast to the regression models reported for feedforward adaptation, all error and sensory uncertainty predictors were taken from the current trial. This regression was statistically significant (Adjusted R2 = 0.94, F(3,174) = 925.1, p < .001). Beta coefficient estimates and corresponding statistics are listed in Table 12.

Table 12. Experiment 3 regression results for predicting feedback integration (endpoint hand angle—initial movement vector) from error and midpoint sensory uncertainty terms.

The coef column contains β coefficients, the se column contains standard errors of these coefficients, the T column contains corresponding t-statistic, the pval column contains corresponding p-values, the CI[2.5%] and CI[97.5%] columns give the 95% confidence interval, and the relimp column gives the corresponding relative importance.

| row | names | coef | se | T | pval | CI[2.5%] | CI[97.5%] | relimp |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | β 0 | -0.46 | 0.07 | -6.44 | 0.0 | -0.61 | -0.32 | NaN |

| 2 | σ MP | -1.04 | 0.14 | -7.26 | 0.0 | -1.33 | -0.76 | 0.01 |

| 3 | δ MP | -0.76 | 0.01 | -50.92 | 0.0 | -0.79 | -0.73 | 0.88 |

| 4 | σMP:δMP | 0.28 | 0.03 | 9.41 | 0.0 | 0.22 | 0.34 | 0.05 |

The most important result from this analysis is that the response of feedback integration to increasing midpoint error (i.e., the slopes in Fig 14b) was significantly greater (i.e., steeper slope) for low sensory uncertainty at midpoint than it was for high uncertainty at midpoint (Table 12 row 4).

Overall, the pattern of feedback integration seen in Experiment 3 are qualitatively identical to those observed in Experiment 1 and 2. Both are consistent prior studies showing that that sensory uncertainty has an error-scaling effect on feedback integration [8, 10].

Model-based results

Experiments that study feedforward adaptation in the absence of feedback integration have shown that sensory uncertainty scales an error-driven adaptation. Our experiments—which all provide a short 100 ms window of task-relevant midpoint feedback and therefore induce both feedback integration and feedforward adaptation—clearly show that while both movement error and sensory uncertainty influence feedforward adaptation, they appear to exert their influence independently of each other. Although it seems unlikely, it is possible that our data can be accounted for by a state-space model that embodies the classic view that sensory uncertainty scales the response to error. Another possibility is that error-driven motor adaptation drives the slow envelope of improving performance over the course of the experiment, and the effect of sensory uncertainty is to punctuate this envelope with abrupt changes (boosts or dips) that do not depend on the magnitude or direction of the experienced error.

Here we explore the ability of two classes of models to account for our data. The first class assumes that sensory uncertainty interacts with the updating of an adaptive learning process. This class of models contains the error-scaling, retention-scaling, and bias-scaling models described below. Of these, the error-scaling model embodies the classic view that sensory uncertainty scales an error-driven update. The second class of model assumes that sensory uncertainty interacts with an additional aiming process that is memory-less (i.e., it does not retain any value from one trial to the next and is instead completely determined by the experienced sensory uncertainty on the previous trial). This class of models contains the state-aim-scaling and output-aim-scaling models described below. This model class is in line with the idea that sensory uncertainty transiently activates explicit aiming. However, there is noting intrinsic to this model that demands the aiming be driven by an explicit process (see the “Adaptation vs aiming” discussion section).

Each of these models makes importantly different assumptions about the role of sensory uncertainty on feedforward adaptation in the presence of feedback integration. The feedforward adaptation component of all five models was based on a standard linear dynamical systems model of sensorimotor adaptation [28]. This type of model assumes that internal state variables which map desired motor goals to motor plans are updated on a trial-by-trial basis according to three factors: (1) an error term that determines how internal states are updated after a movement error is detected, (2) a retention term that determines how quickly the internal state returns to baseline, and (3) a bias term that determines the baseline mapping that will be returned to in the absence of sensory input.

The error-scaling model assumes that the error term is inversely scaled by the level of sensory uncertainty. The retention-scaling model assumes that the retention term is inversely scaled by the level of sensory uncertainty. The the bias-scaling model assumes that the bias term is inversely scaled by the level of sensory uncertainty. The state aim-scaling model is equivalent to the bias-scaling model with zero retention and zero error sensitivity. In contrast to all other models, the output-aim-scaling model assumes that the output motor command—as opposed to some aspect of the internal state—is inversely scaled by sensory uncertainty. For all models, four parameters (γL, γM, γH and γ∞) encode the magnitude of scaling applied on low uncertainty, medium uncertainty, high uncertainty, and no-feedback trials.

Sensory uncertainty influences feedback integration in the same way across all five models: error experienced at reach midpoint generates a feedback motor command in the opposite direction of the sensed movement error with a magnitude that inversely scales with the level of sensory uncertainty of that signal. The magnitude of this scaling is captured by four parameters (ηL, ηM, ηH and η∞).

We fit single-state and two-state variants of each of the models just described. As suggested by this nomenclature, single-state model variants assume a single state variable determines the mapping from motor goal to motor plan. Two-state variants assume this mapping is determined by two state variables, one fast but labile and the other slow but stable [29]. In our two-state models, uncertainty scaling was applied only to the fast state variable.

Finally, we fit two different versions of the two-state models that differed in the bounds that the parameters were allowed to take. In one version, these parameter bounds lead the internal state variables to take negative values. In the other version, bounds were constrained such that the internal state variables were not allowed to take negative values. See supplemental figures for slow and fast-state model fits (S1–S30 Figs), as well as distributions of best-fitting parameters (S1–S3 Tables) as described in the State-space modelling section of the Methods and Materials. The BIC values across all models and experiments are presented in Fig 15.

Fig 15. Bar graph depicting model BIC values for Experiments 1,2 and 3.

Error-scaling model variants in blue. Retention-scaling variants in orange. Bias-scaling variants in green. State-aim variants in red. Output-aim variants in purple. Opacity indicate model sub-type: Non-negative two-state models have 100% opacity. Two-state models have 50% opacity and one-state models have 25% opacity. Error-bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

We also performed a model rank analysis in which, for each participant within each experiment, we ordered the models from best fitting (smallest BIC) to worst fitting (largest BIC). We then counted the number of participants, best fit (rank 1), second best fit (rank 2), third best fit (rank 3) etc. for each model. The resulting counts are shown in Fig 16. This figure clearly reveals that in Experiment 1 the State-aim-scaling-two-state and Output-aim-scaling-two-state models provide the first and second best fits to the data. The non-negative versions of these models, in addition to the bias-scale-two-state model, also provide the third, fourth, and fifth best account of the data. A very similar pattern is observed in Experiment 2 with the State-aim-scaling-two-state and Output-aim-scaling-two-state models providing the majority of best and second best fits. However, here here the retention-scale-two-state model provided the best fit for 4 participants, the second best fit for 3 particpants, and the third best for 12 participants. Here, the bias-scale-two-state model provided the fourth best fit for 16 participants. The results for Experiment 3 are slightly more varied with best and second best fits being split between the State-aim-scaling-two-state, Output-aim-scaling-two-state, retention-scale-two-state, and bias-scale-two-state models. These models in addition to the bias-scale-two-state-non-neg are also the third best fitting models. All variants of the error-scaling models did not perform well by this analysis, being ranked between 6 and 10 across all experiments. Additionally, Figs 17, 18 and 19 illustrate the predicted behaviour from each model class in comparison to the behaviour observed in humans for Experiment 1, Experiment 2, and Experiment 3, respectively.

Fig 16. Model rank analysis showing the number of particpants that were best fit (rank 1), second best fit (rank 2), third best fit (rank 3) etc.

by a model of each type. Results for Experiment 1 are shown on the left using shades of blue, results for Experiment 2 are shown in the middle using shades of green, and results for Experiment 3 are shown on the right using shades of red. Deeper colours indicate a greater count.

Fig 17. Experiment 1 model fits.

Left column shows initial movement vectors averaged across participants overlaid with the average full model prediction of the (A) Two-state error-scaling model. (C) Two-state retention-scaling model. (E) Two-state bias-scaling model. (G) Two-state state-aim-scaling model (I) Two-state output-aim-scaling model. Right column shows corresponding model fits to endpoint hand-angles. Here, human performance averaged across participants is shown in blue. Model predictions in orange. Fit lines and R2 values represent average of models fit to individual subjects.

Fig 18. Experiment 2 model fits.

Left column shows initial movement vectors averaged across participants overlaid with the average full model prediction of the (A) Two-state error-scaling model. (C) Two-state retention-scaling model. (E) Two-state bias-scaling model. (G) Two-state state-aim-scaling model (I) Two-state output-aim-scaling model. Right column shows corresponding model fits to endpoint hand-angles. Here, human performance averaged across participants is shown in blue. Model predictions in orange. Fit lines and R2 values represent average of models fit to individual subjects.

Fig 19. Experiment 3 model fits.