Abstract

PURPOSE

The Standardized Definitions for Efficacy End Points (STEEP) criteria, established in 2007 and updated in 2021 (STEEP 2.0), provide standardized definitions of adjuvant breast cancer (BC) end points. STEEP 2.0 identified a need to separately address end points for neoadjuvant clinical trials. The multidisciplinary NeoSTEEP working group of experts was convened to critically evaluate and align neoadjuvant BC trial end points.

METHODS

The NeoSTEEP working group concentrated on neoadjuvant systemic therapy end points in clinical trials with efficacy outcomes—both pathologic and time-to-event survival end points—particularly for registrational intent. Special considerations for subtypes and therapeutic approaches, imaging, nodal staging at surgery, bilateral and multifocal diseases, correlative tissue collection, and US Food and Drug Administration regulatory considerations were contemplated.

RESULTS

The working group recommends a preferred definition of pathologic complete response (pCR) as the absence of residual invasive cancer in the complete resected breast specimen and all sampled regional lymph nodes (ypT0/Tis ypN0 per AJCC staging). Residual cancer burden should be a secondary end point to facilitate future assessment of its utility. Alternative end points are needed for hormone receptor–positive disease. Time-to-event survival end point definitions should pay particular attention to the measurement starting point. Trials should include end points originating at random assignment (event-free survival and overall survival) to capture presurgery progression and deaths as events. Secondary end points adapted from STEEP 2.0, which are defined from starting at curative-intent surgery, may also be appropriate. Specification and standardization of biopsy protocols, imaging, and pathologic nodal evaluation are also crucial.

CONCLUSION

End points in addition to pCR should be selected on the basis of clinical and biologic aspects of the tumor and the therapeutic agent investigated. Consistent prespecified definitions and interventions are paramount for clinically meaningful trial results and cross-trial comparison.

INTRODUCTION

The Standardized Definitions for Efficacy End Points (STEEP) criteria were established in 2007 by a group of breast cancer (BC) clinical trial experts from the National Cancer Institute and the National Clinical Trials Network1 to provide consistent, standardized definitions for end points in adjuvant BC trials. In 2021, STEEP was updated (STEEP 2.0) to address advances in cancer treatment, imaging, and clinical trial design.2 STEEP 2.0 emphasized that the end points used for neoadjuvant trials added a layer of complexity that should be addressed separately. The NeoSTEEP working group was formed to critically evaluate and align neoadjuvant trial end points.

Historically, neoadjuvant systemic therapy was considered in the setting of locally advanced disease to achieve operability, but its use evolved to include downstaging operable tumors to allow for breast conservation. There was early recognition that response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) was prognostic,3 which led to the use of pathologic response as an end point, and to trials of adjuvant therapy focusing on patients with residual disease after NAC. Neoadjuvant therapy has become the standard of care for triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2–positive (HER2+) BC because pathologic response–guided adjuvant therapy has shown improvement in survival.4 The prognostic and clinical value of pathologic response is more limited in hormone receptor–positive (HR+) BCs. Although the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and others have provided guidance on using pathologic complete response (pCR) as an end point in neoadjuvant BC trials,5 there is a lack of standardization for definitions of both pathologic response and long-term efficacy end points, presenting challenges in cross-trial comparison and with meta-analyses.6,7 In addition, study designs have become more complicated as biologic subtypes and targeted therapies were incorporated. In this article, we propose standardized end points for clinical trials of neoadjuvant treatment for early BC and outline trial design considerations affecting end point assessment. The NeoSTEEP working group concentrated on neoadjuvant therapy end points in clinical trials with efficacy outcomes, particularly when there is registrational intent. Special considerations for neoadjuvant studies, such as timing of random assignment and interventions, were reviewed by the working group and incorporated into these guidelines.

RECOMMENDED PATHOLOGIC END POINTS

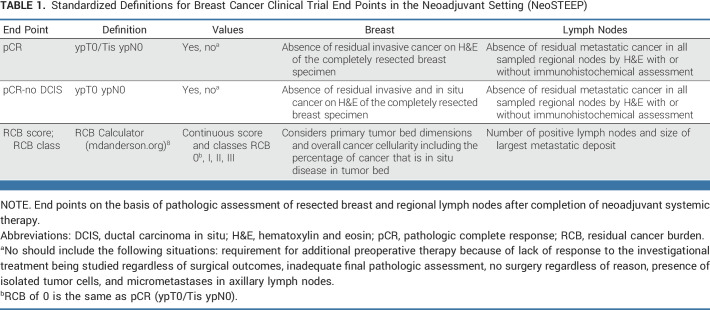

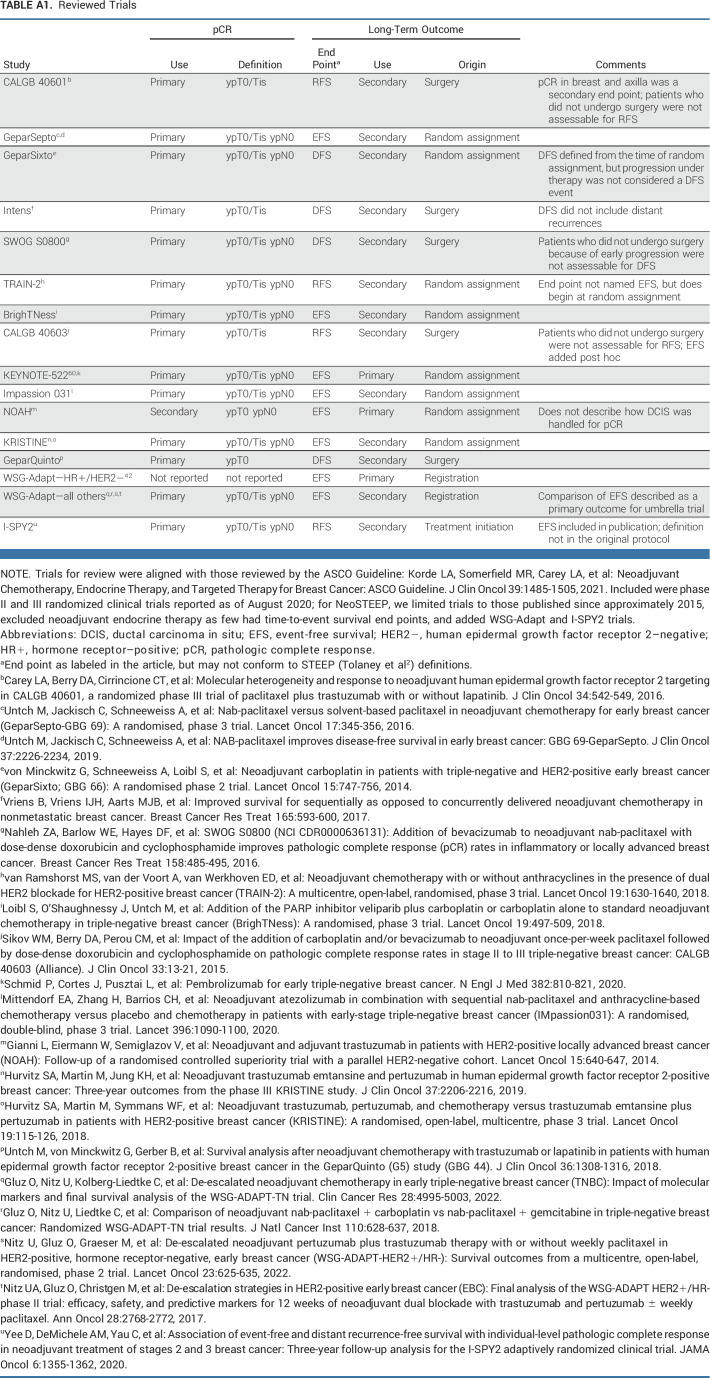

Recent neoadjuvant clinical trials6,7 have used varying definitions of both end points and the elements comprising each end point (reviewed in Appendix Table A1, online only). Here, we recommend standardized definitions of end points for neoadjuvant BC trials. The proposed end points for neoadjuvant BC trials are summarized in Table 1. The working group notes that there are ongoing international efforts to standardize pathologic reporting for numerous cancer types.9

TABLE 1.

Standardized Definitions for Breast Cancer Clinical Trial End Points in the Neoadjuvant Setting (NeoSTEEP)

pCR Definition

pCR is strongly associated with long-term survival outcomes, most notably in HER2+ and TNBC, and is commonly used as the primary end point in neoadjuvant clinical trials.10 The FDA performed a pooled analysis evaluating the three most commonly used definitions of pCR7 and recommended either of two definitions, which differ only on the basis of whether residual ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) is considered5:

pCR (ypT0/Tis ypN0) is defined as the absence of residual invasive cancer on hematoxylin and eosin evaluation of the complete resected breast specimen and all sampled regional lymph nodes following completion of neoadjuvant systemic therapy

or

pCR-no DCIS (ypT0 ypN0) is defined as the absence of residual invasive and in situ cancer on hematoxylin and eosin evaluation of the complete resected breast specimen and all sampled regional lymph nodes following completion of neoadjuvant systemic therapy.

We recommend that the first definition, pCR (ypT0/Tis ypN0), is the preferred definition for neoadjuvant systemic therapy trials.11 However, the absence of DCIS may be valuable in specific clinical situations, such as trials evaluating omitting local therapies. Should a trial prefer pCR-no DCIS (ypT0 ypN0) as the primary end point, this should be defined a priori in the protocol, used consistently in the pathologic assessment, and clearly stated in resulting publications.

Additional Considerations for pCR

For the clinical trial end point definition, a patient who requires further preoperative therapy because of lack of response to the treatments being studied should be considered not to have obtained a pCR regardless of the ultimate surgical outcome, and it should be prespecified in the protocol as an event-free survival (EFS) event (discussed below). This may include trial designs with protocol-specified treatment change on the basis of response, in which a core biopsy showing residual invasive disease would document non-pCR. Similarly, patients in whom the final pathologic assessment is inadequate, or surgery is not performed, should be categorized as having non-pCR. The presence of isolated tumor cells and micrometastases in axillary nodes after neoadjuvant therapy is not considered a pathologic complete response and has been associated with worse outcomes compared with node-negative patients, especially in invasive lobular carcinoma.7,10,12 If relevant in a given trial, these terms should be defined prospectively and consistently reported as present or absent in addition to pCR.13

Novel trial designs, such as those with intrapatient escalation because of nonresponse, present additional nuances. In these types of studies, pCR and EFS will be problematic to interpret for regulatory purposes because such a design cannot isolate the individual contribution of a given agent. Given the complexity of intrapatient escalation designs, if one is being contemplated in a registration trial, a meeting should be requested with regulatory agencies in advance.

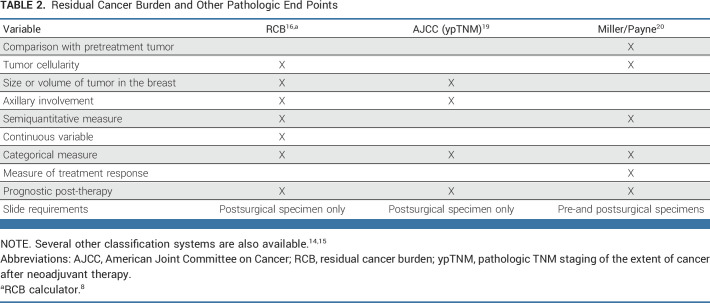

Residual Cancer Burden and Other Pathologic End Points

Although many studies have shown that pCR is associated with an excellent prognosis, additional nuances must be considered among patients who do not obtain a pCR. Several nonbinary end points have been proposed and may provide additional information. However, the current evidence base for these is less robust.14,15 Residual cancer burden index (RCB) incorporates additional pathologic characteristics at the time of definitive surgery and therefore provides more granular information when pCR is not attained. RCB can be used as a continuous variable or to define response classes: RCB-0 (pCR [ypT0/Tis ypN0]), RCB-I (minimal residual disease), RCB-II (moderate residual disease), and RCB-III (extensive residual disease or progression on neoadjuvant therapy). RCB score and class have been demonstrated in multiple studies to be associated with long-term survival outcomes in patients receiving NAC.16,17 The clinical utility of RCB score as a continuous variable for comparison of treatment arms is currently under investigation and will require further validation.18 We have reviewed the available supporting data for RCB and other nonbinary end points (Table 2) and recommend that RCB, both score and class, be included whenever feasible as a secondary end point for neoadjuvant trials to facilitate future assessment of its utility.

TABLE 2.

Residual Cancer Burden and Other Pathologic End Points

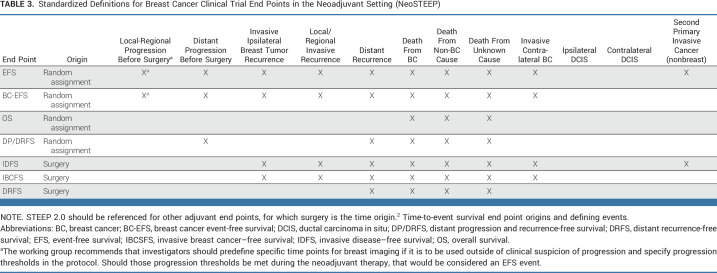

Survival End Points

Investigational treatments can be considered promising on the basis of increasing pCR rate over standard therapy. However, neoadjuvant registration trials should also include time-to-event survival end points that begin at random assignment, such as EFS and overall survival (OS), as these include both progression and deaths because of toxicity before surgery as events. If a trial includes both pre- and postsurgical therapies, end points that begin at the time of definitive surgery, as defined in STEEP 2.0, should also be reported. Table 3 details the starting point (time origin) and events included in each proposed end point definition. EFS events occurring postsurgery align with the invasive disease-free survival (IDFS) events as defined by STEEP 2.0, and similarly, BC-EFS aligns with the invasive breast cancer–free survival (IBCFS) end point. Other adaptations of STEEP 2.0 end points to the neoadjuvant setting may be appropriate, on the basis of standardized STEEP 2.0 definitions and nomenclature.

TABLE 3.

Standardized Definitions for Breast Cancer Clinical Trial End Points in the Neoadjuvant Setting (NeoSTEEP)

The working group recognizes that clinical progression during neoadjuvant therapy does not always result in inoperability, whereas EFS commonly refers only to progression that precludes surgery as an event. Clinical progression may be evaluated and defined differently. The working group recommends investigators predefine specific times for breast imaging, whether it is to be used outside of clinical suspicion of progression, and specify thresholds for progression in the protocol. Should those thresholds be met during neoadjuvant therapy, that would be considered an EFS event as defined in the protocol.

IMAGING CONSIDERATIONS IN NEOADJUVANT CLINICAL TRIALS

Determining Clinical Stage at Baseline

Baseline clinical and imaging evaluation of the breast and regional nodes should be considered standard for all neoadjuvant trials.21 Conventional breast imaging performed before initiation of neoadjuvant therapy includes mammography and ultrasound.22 Dynamic contrast-enhanced breast magnetic resonance imaging (DCE-MRI) may also be used in the baseline evaluation and is the most sensitive modality for BC detection.23 Contrast-enhanced mammography is currently being evaluated. While each imaging modality might have merit on the basis of the trial objectives, the selected imaging protocol should be clearly stated and applied consistently throughout the course of the trial. A core biopsy or fine-needle aspiration of suspicious accessible axillary lymph nodes should be completed before random assignment per standard staging guidelines.21,24 Sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) and/or nodal dissection should not be performed before neoadjuvant treatment if pCR is the primary end point as this precludes evaluation of nodal response.

Response Assessment During Treatment

Imaging evaluation during neoadjuvant treatment may serve three distinct purposes: assess treatment response, substantiate clinical suspicion of disease progression, and assist in surgical treatment planning. The same imaging modality used at baseline should be performed for the measurement of clinical response to therapy. Although ultrasound is commonly used to measure changes in tumor size during neoadjuvant therapy because of its availability and low cost, DCE-MRI offers higher diagnostic accuracy in primary tumor response assessment than other currently established methods (physical examination, mammography, and ultrasonography).25-28 However, no current imaging method predicts pCR accurately enough to obviate the need for surgery.29-31 Multiple emerging functional and molecular imaging techniques, using advanced magnetic resonance imaging and/or radionuclide imaging to assess physiologic changes induced by treatment, as well as machine and deep learning applications, are under investigation to improve the assessment of treatment response.22,32

Disease progression is observed in 3%-5% of patients during NAC.33 Protocols should clearly specify the management, including required imaging, for patients in whom disease progression is suspected. Treatment recommendations, if progression is confirmed, should be predefined in the research plan. In neoadjuvant trial designs, regardless of whether intrapatient treatment escalation is permitted on protocol, patients with progression who discontinue study treatment should be categorized as having non-pCR for regulatory and reporting purposes. The protocol should also specify that progression during neoadjuvant therapy that precludes surgery or meets prespecified criteria is an EFS event.5

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS IN NEOADJUVANT CLINICAL TRIALS

Local Therapy End Points

In early NAC trials, the proportion of patients whose disease was downstaged—either from inoperable to operable or from requiring mastectomy to becoming breast conservation candidates—was considered clinically meaningful and therefore was often reported as a study end point.34,35 As clinical trials in the neoadjuvant setting expand into earlier-stage disease, these end points are less relevant. However, in neoadjuvant clinical trials that accrue large numbers of locally advanced BCs, reporting breast conservation eligibility rates (yes v no) before and after neoadjuvant therapy as a secondary end point is encouraged. If a trial includes eligibility for breast conservation as an end point, the protocol should include specific parameters to define eligibility for breast-conserving surgery, taking into account that some patients who are eligible for breast conservation may opt for mastectomy.21,24

Nodal Staging Considerations at Surgery

In patients treated with neoadjuvant therapy, axillary surgery paradigms are dependent on presenting clinical nodal status and treatment response. The NeoSTEEP working group acknowledges that management of the axilla after neoadjuvant therapy is evolving; however, inadequate axillary evaluation—either before or after neoadjuvant therapy—may affect pCR as an outcome. The staging of the axilla should use the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging system19 at diagnosis, and management should be predefined in the protocol and used consistently throughout the trial with the following as suggested considerations according to the clinical staging of the lymph nodes (cN):

For patients with cN0 disease, no further surgery is indicated in the setting of negative sentinel nodes. For cN1 disease with evidence of response to neoadjuvant therapy, a surgical axillary staging procedure—SLNB with or without targeted excision of the pretreatment biopsied lymph node(s)—can be pursued, provided that technical elements are incorporated to minimize the false-negative rate. While multiple ongoing studies may influence this guidance in the future, currently, any patient with positive node(s) postneoadjuvant therapy or an inadequate surgical axillary staging procedure should undergo axillary node dissection.

For patients with cN2 disease at diagnosis, there is insufficient evidence to support limited axillary evaluation (SLNB with or without targeted excision of the pretreatment biopsied lymph node) and at a minimum, level 1 and 2 axillary dissection should be prespecified.

For patients presenting with cN3 disease, there are no data to support limited axillary evaluation. Level 1 and 2 axillary lymph node dissection with intraoperative palpation of level 3 nodes and dissection if clinically indicated should be performed after neoadjuvant therapy, irrespective of response to therapy. Inclusion of patients with cN3 disease in trials with a primary or coprimary end point of pCR should be carefully considered with well-defined imaging parameters for assessing response to therapy as all sites of disease will not be pathologically examined.

HR+ Disease

The likelihood of pCR varies widely among BC subtypes. HR+ cancers are less likely than triple-negative or HER2+/estrogen receptor (ER)–negative disease to achieve a pCR with chemotherapy. However, as with other subtypes, pCR in HR+ disease is associated with better long-term prognosis compared with non-pCR.10 Reported pCR rates for unselected HR+ disease range from approximately 7% to 11% in chemotherapy trials7,10,36-38 and from 2% to 6% with endocrine therapy alone or combined with targeted therapy, despite high clinical response rates.39-41 Given these low pCR rates, other end points have been sought for evaluation of neoadjuvant treatment efficacy in HR+ disease.

Currently, the working group does not recommend a specific end point associated as a registrational end point for neoadjuvant endocrine therapy (NET). Ki-67 is a measure of proliferation and has been associated with response to NET. Several studies have investigated changes in Ki-67 after short-term NET as a continuous measure, as a binary measure below a threshold of ≤10%, as Preoperative Endocrine Prognostic Index (PEPI) score in combination with clinical tumor size and level of ER expression, or as a surrogate marker for long-term efficacy with endocrine therapy alone.42,43 Results of phase II trials with change in Ki-67 as the primary end point seem to mirror results of larger phase III adjuvant studies.44-47 The PEPI score combines clinical tumor size, Ki-67, and level of ER expression after NET and has been evaluated in several studies, but data have not yet correlated PEPI score with long-term outcomes, and therefore, we are not recommending it as a regulatory end point.48,49 In a meta-analysis of patients treated with NAC,48 higher RCB was associated with worse EFS in patients with unselected HR+ tumors. In contrast to other subtypes, in which EFS is superior with RCB-0 (pCR) than with any degree of residual disease, patients with HR+ disease had similar EFS with RCB-0 and RCB-I. This highlights the complexity of using intermediate neoadjuvant end points in HR+ disease and the heterogeneity of this subset. Thus, although several measures have demonstrated prognostic value, further studies are required to fully validate surrogate end points for long-term outcome in HR+ disease before being considered as primary end points in definitive trials.43,50

Further complicating pathologic response assessment in HR+ disease is the degree of heterogeneity of this subtype. Tumors with a luminal B or basal intrinsic subtype (even with high expression of HRs), higher Ki-67, high-risk gene expression score, and lower quantitative expression of HRs (<10%) are more likely to have a pCR after NAC.51,52 Multiple arms of the I-SPY 2 trial suggested that among HR+ cancers, MammaPrint Ultra-High status might define a subset where pCR rate improvement could serve as a useful early predictor of long-term outcome51,53,54 However, in the current studies, patient selection may heavily influence response rates and long-term outcomes. Neoadjuvant clinical trials including or focusing on HR+ disease should therefore carefully define the biologic subset to be included to facilitate identification of appropriate pathologic end points.55-57

Immunotherapy Trials

Treatment with neoadjuvant immunotherapy combined with chemotherapy for TNBC may improve long-term outcome even in patients who do not achieve a pCR.58 Current data suggest that the burden of residual disease, as measured by RCB, may predict survival benefit of immunotherapy among patients who do not achieve pCR,59 highlighting the importance of including both pCR and EFS as end points in neoadjuvant registrational trials, especially for patients receiving immunotherapy.60

Inflammatory Breast Cancer

Recent international, multi-institutional consensus statements on the clinical management of invasive breast cancer (IBC) recommend NAC as the standard of care61,62 and highlight the paucity of trials that include IBC, leading to limited data on efficacy of new regimens in this patient population. While pCR is associated with improved survival and remains a relevant end point, the magnitude of benefit is less than that of non-IBC pCR.63,64 Modified radical mastectomy continues to be the standard-of-care surgery for this patient population,61 and as such, breast conservation rates are not relevant. Patients with IBC often have cN3 disease at diagnosis and may be unnecessarily excluded from trials assessing pCR out of concern that the unresected cN3 disease is unevaluable. Disease control in unresected regional nodes is excellent, with adequate radiotherapy targeting all diseases visible on pretreatment imaging.65 This highlights the critical importance of adequate clinical staging with cross-sectional imaging through the neck in all patients with cN3 disease.

Bilateral and Multifocal Diseases

The incidence of synchronous bilateral BC is between 1.5% and 3% of all newly diagnosed BCs, and the histologic type and receptor statuses of these cancers may differ from one another.66 Molecular evidence supports viewing the two tumors as two distinct primary lesions and not as one disease with metastatic spread.67 Discordant ER or HER2 receptor status, which is observed in 10%-20% of cases, creates an eligibility conundrum for clinical trials that are BC receptor subtype-specific and may confound results.68 Should investigators choose to include these patients in a neoadjuvant clinical trial, each cancer should be evaluated independently for pathologic response and both the end points and measurements must be carefully predefined. In patients with molecularly distinct synchronous bilateral BCs, the origin of recurrent or metastatic lesions may be challenging to ascertain and postoperative systemic therapy could include multiple agents that would differ from the rest of the trial population; therefore, excluding these patients from trial eligibility may be appropriate.

Improved sensitivity of breast imaging modalities has resulted in an increase in the clinical diagnosis of unilateral multifocal BC. In these cases, the diameter of the largest contiguous lesion is used to assign clinical stage (AJCC 8th edition).19 According to the College of American Pathologists (CAP), when assigning receptor subtype, receptor characterization of only the largest lesion is required (because of >90% concordance in receptor status and other molecular features across distinct foci, indicating singular cellular origin), unless the grade and/or histology are different between the lesions, in which case each distinct histologic lesion should be assessed separately.69,70 Neoadjuvant trials may also include non–standard-of-care imaging to assess response and to explore biologic correlates of response and resistance. These modalities might have increased sensitivity to discern multifocal/multicentric cancers. If the imaging modality used to determine trial eligibility differs from that used to assess on-treatment response, these could generate discordant results; thus, use of a consistent imaging modality is preferred. However, if this is not desirable or feasible, rules to adjudicate discordant results should be clearly outlined in the study protocol.

Planned Correlative Tissue Collection

The inclusion of correlative science and specimen collection during a clinical trial is imperative to elucidate factors associated with treatment response and resistance. However, removal of tissue could affect a primary end point of pCR (eg, multiple core biopsies of a very small tumor may eliminate all residual diseases). There is also a concern that optional biopsies may be distributed unequally if not agreed on before random assignment. We therefore recommend specifying a limited number and size of cores to be obtained. If biopsies are optional, then whether the patient agreed to undergo a biopsy should be considered as a stratification factor.

QUALITY OF LIFE AND PATIENT-REPORTED OUTCOMES

Many aspects of assessing quality of life (QOL) and patient-reported outcomes (PRO) are shared between neoadjuvant and adjuvant systemic therapy trials although neoadjuvant trials have some unique therapeutic aspects. Tumor shrinkage and/or eradication of nodal disease after neoadjuvant therapy allows less extensive surgical therapy, which may lead to increased rates of breast conservation and less surgical morbidity (lower rates of lymphedema) with improved cosmetic outcomes.71 Patient-reported satisfaction with outcome and QOL after breast surgery is an important patient-level outcome. Leaders in the domain of PROs after breast surgery have developed a validated multidomain tool, the BREAST-Q,72 to study the impact of different local therapy strategies (breast-conserving surgery v mastectomy with or without reconstruction) and the impact of axillary treatment on PROs.73

Capturing patient satisfaction with surgical outcome is an important end point in neoadjuvant trials, particularly if the therapies that are compared between the trial arms have different cosmetic outcomes (ie, drugs that might interfere with wound healing, or patients in one trial arm continue to receive an experimental therapy concurrent with radiation therapy).

FDA REGULATORY CONSIDERATIONS

Products that are safe and effective for the treatment of BC should be incorporated into the curative setting, where they will provide the greatest benefit to patients, as efficiently as possible. FDA supports the use of neoadjuvant trials as a means of expediting drug development for high-risk, early-stage BC and encourages the use of pCR as the key pathologic end point in preoperative studies conducted with registrational intent.74 It is expected that the association between pCR and long-term outcome may differ between BC subtypes and classes of therapeutic products. Although achieving pCR portends an improved prognosis for individual patients, the difference in pCR that may translate into a reduced risk of recurrence or death for a given therapeutic agent remains unclear at this time. Given the uncertainties regarding the association of pCR with long-term outcomes, pCR is considered in the context of the totality of data regarding efficacy and safety. Time-to-event end points such as EFS, IDFS, and OS remain essential for risk-benefit assessment to support regulatory approval. Finally, FDA notes that non-pCR in the preoperative setting is a valuable prognostic biomarker for enrichment of adjuvant clinical trials for patients with high unmet medical need.75 All neoadjuvant registration trials should be discussed in advance with regulatory agencies.

In summary, the NeoSTEEP working group reviewed clinical trial designs and herein provides recommendations and definitions for end points for neoadjuvant BC trials. Uniform definitions for events and time of origin for each time-to-event end point are critical and will allow for consistent evaluations of treatment benefit across studies. Nonbinary pathologic end points were reviewed and considered; RCB is currently the most well-studied. The working group recommends that pCR be defined as the absence of residual invasive cancer in the complete resected breast specimen and all sampled regional lymph nodes (ypT0/Tis ypN0 per AJCC staging). We recognize that the binary outcome of pCR may not fully capture the benefits of therapies and interventions, particularly in HR+ disease. While the working group determined that there is no sufficient justification to support RCB as a recommended primary end point for registrational purposes, we recommend that RCB be included as a secondary end point for neoadjuvant BC trials to enable potential validation of this end point for future use, especially when evaluating novel therapeutics and immunotherapies.

Both pCR and time-to-event end points that begin at random assignment should be included as end points in neoadjuvant trials with registrational intent. Additional end points should be chosen on the basis of clinical and biologic aspects of the tumor and the therapeutic agent under investigation. Specification and standardization of biopsy protocols, imaging modalities, time points for data collection, and approaches to pathologic evaluation are also crucial. Consistent prespecified definitions and interventions are paramount to a well-designed and well-conducted trial that will provide clinically meaningful results.

Although there are many factors involved in designing robust neoadjuvant clinical trials, the working group focused the scope of NeoSTEEP on end points in registrational trials and acknowledges that therapeutics will evolve and more questions regarding trial design will emerge. This further necessitates the consistent use of long-term outcome end points with well-defined starting time points and the need to revisit and revise guidelines such as NeoSTEEP over time. As with the STEEP criteria in adjuvant BC, it is expected that NeoSTEEP will similarly require future updates.

APPENDIX

TABLE A1.

Reviewed Trials

Jennifer K. Litton

Honoraria: UpToDate

Consulting or Advisory Role: Pfizer, AstraZeneca, Medivation/Pfizer, Ayala Pharmaceuticals

Speakers' Bureau: Physicians' Education Resource, UpToDate, Med Learning Group, Medscape, Prime Oncology, Clinical Care Options, Medpage

Research Funding: Genentech (Inst), Pfizer (Inst), EMD Serono (Inst), AstraZeneca (Inst), Zenith Epigenetics (Inst), Merck (Inst), GlaxoSmithKline (Inst)

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: UptoDate, Patent Royalty by Certis (Inst)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Physicians' Education Resource, Med Learning Group, Medscape, Clinical Care Options

Other Relationship: Medivation/Pfizer

Meredith M. Regan

Consulting or Advisory Role: Ipsen (Inst), Tolmar, Bristol Myers Squibb, Debiopharm Group (Inst), TerSera, AstraZeneca

Research Funding: Pfizer (Inst), Ipsen (Inst), Novartis (Inst), Merck (Inst), AstraZeneca (Inst), Pierre Fabre (Inst), Bayer (Inst), Bristol Myers Squibb (Inst), Roche (Inst), TerSera (Inst), Debiopharm Group (Inst), BioTheranostics (Inst)

Lajos Pusztai

Honoraria: BioTheranostics, Natera, OncoCyte, Athenex

Consulting or Advisory Role: H3 Biomedicine, Merck, Novartis, Seagen, Syndax, AstraZeneca, Roche/Genentech, Bristol Myers Squibb, Clovis Oncology, Immunomedics, Eisai, Almac Diagnostics, Pfizer

Research Funding: Merck (Inst), Genentech (Inst), Seagen (Inst), AstraZeneca (Inst), Bristol Myers Squibb (Inst), Pfizer (Inst)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: AstraZeneca

Uncompensated Relationships: NanoString Technologies, Foundation Medicine

Open Payments Link: https://openpaymentsdata.cms.gov/physician/110878

Hope S. Rugo

Consulting or Advisory Role: Napo Pharmaceuticals, Puma Biotechnology, Mylan, Eisai, Daiichi Sankyo

Research Funding: OBI Pharma (Inst), Pfizer (Inst), Novartis (Inst), Lilly (Inst), Merck (Inst), Daiichi Sankyo (Inst), Sermonix Pharmaceuticals (Inst), AstraZeneca (Inst), Gilead Sciences (Inst), Astellas Pharma (Inst), Pionyr (Inst), Taiho Oncology (Inst), Veru (Inst), GlaxoSmithKline (Inst), Hoffmann-La Roche AG/Genentech Inc (Inst)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Merck, AstraZeneca, Gilead Sciences

Open Payments Link: https://openpaymentsdata.cms.gov/physician/183398

Sara M. Tolaney

Consulting or Advisory Role: Novartis, Pfizer, Merck, Lilly, AstraZeneca, Genentech, Eisai, Sanofi, Bristol Myers Squibb, Seagen, CytomX Therapeutics, Daiichi Sankyo, Immunomedics/Gilead, 4D Pharma, BeyondSpring Pharmaceuticals, OncXerna Therapeutics, Zymeworks, Zentalis, Blueprint Medicines, Reveal Genomics, ARC Therapeutics, Myovant Sciences, Umoja Biopharma, Menarini Group, AADi, Artios Biopharmaceuticals, Incyte, Zetagen, Bayer

Research Funding: Genentech/Roche (Inst), Merck (Inst), Exelixis (Inst), Pfizer (Inst), Lilly (Inst), Novartis (Inst), Bristol Myers Squibb (Inst), Eisai (Inst), AstraZeneca (Inst), NanoString Technologies (Inst), Cyclacel (Inst), Sanofi (Inst), Seagen (Inst), OncoPep (Inst), Gilead Sciences (Inst)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Lilly, Sanofi

Reva K. Basho

Employment: Alignment Healthcare (I), Apollo Medical Holdings (I), Lawrence J. Ellison Institute for Transformative Medicine

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Alignment Healthcare (I), Apollo Medical Holdings (I), Fresenius (I)

Consulting or Advisory Role: Seagen, Pfizer, Gilead Sciences, AstraZeneca

Speakers' Bureau: Lilly

Research Funding: Seagen (Inst), Merck (Inst), Pfizer (Inst), Takeda (Inst), Lilly (Inst)

Other Relationship: WebMD/Medscape, MJH Healthcare Holdings LLC

Uncompensated Relationships: Novartis, Pfizer, Genentech, AstraZeneca

Jean-Francois Boileau

Consulting or Advisory Role: Roche, Lilly, Pfizer, Merck, Exact Sciences, Novartis, AstraZeneca

Speakers' Bureau: Roche, Novartis, Pfizer, Merck, Exact Sciences, AstraZeneca

Research Funding: Roche (Inst), Novartis (Inst), Pfizer (Inst), AbbVie (Inst), Merck (Inst), Lilly (Inst), Bristol Myers Squibb (Inst), Exact Sciences (Inst), AstraZeneca (Inst)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Roche, Allergan

Carsten Denkert

Consulting or Advisory Role: MSD Oncology, Daiichi Sankyo, Molecular Health, AstraZeneca, Roche, Lilly

Research Funding: Myriad Genetics (Inst), Roche (Inst), German Breast Group (Inst)

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: VMscope digital pathology software, Patent WO2020109570A1, Patent WO2015114146A1, Patent WO2010076322A1

Nadia Harbeck

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: West German Study Group

Honoraria: Roche, Novartis, Pfizer, AstraZeneca, Pierre Fabre, Daiichi-Sankyo, MSD, Seagen, Lilly, Viatris, Sanofi, Zuellig Pharma, Gilead Sciences, Amgen

Consulting or Advisory Role: Novartis, Sandoz, West German Study Group (I), Seagen, Gilead Sciences, Roche/Genentech

Speakers' Bureau: Medscape, Springer Healthcare, EPG Communication

Research Funding: Roche/Genentech (Inst), Lilly (Inst), MSD (Inst), AstraZeneca (Inst)

Heather A. Jacene

Honoraria: Blue Earth Diagnostics, Munrol

Consulting or Advisory Role: Advanced Accelerator Applications, Spectrum Dynamics

Research Funding: GTx (Inst), Siemens Healthineers (Inst), Blue Earth Diagnostics (Inst)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: GE Healthcare

Tari A. King

Honoraria: Genomic Health, Exact Sciences

Consulting or Advisory Role: Genomic Health, Besins Healthcare, Exact Sciences

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Grupo Oncoclinicas

Other Relationship: PrecisCa

Ginny Mason

Consulting or Advisory Role: Novartis Pharmaceuticals UK Ltd (Inst), Novartis (Inst)

Ciara C. O'Sullivan

Honoraria: Seagen (Inst), AstraZeneca (Inst), Medscape (Inst)

Research Funding: Lilly (Inst), Seagen (Inst), Bavarian Nordic (Inst), Academic & Community Cancer Research United (Inst), Sermonix Pharmaceuticals (Inst), Tesaro (Inst), Genentech (Inst), Eisai (Inst), nference (Inst)

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: nference Astra Zeneca (Inst)

Andrea L. Richardson

Consulting or Advisory Role: AstraZeneca, Oliver Wyman Health and Life Sciences Consulting/Marsh McLennan

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: Inventor on HRD assay licensed to Myriad genetics. The IP is designated to Partners Healthcare. I am entitled to royalties and license fees

Mary Lou Smith

Consulting or Advisory Role: Novartis, Pfizer, Bayer (Inst)

Research Funding: Genentech (Inst), Novartis (Inst), Foundation Medicine (Inst), Exact Sciences (Inst), Pfizer (Inst), Seagen (Inst), Lilly (Inst)

Wendy A. Woodward

Honoraria: Exact Sciences

Consulting or Advisory Role: Exact Sciences, Epic Sciences

Open Payments Link: https://openpaymentsdata.cms.gov/physician/440115

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

DISCLAIMER

The views expressed in this article are the authors' views and do not necessarily represent the views, opinions, or positions of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, National Cancer Institute, and the FDA.

J.K.L. and M.M.R. contributed equally as cofirst authors to this work.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Jennifer K. Litton, Meredith M. Regan, Lajos Pusztai, Sara M. Tolaney, Elizabeth Garrett-Mayer, Laleh Amiri-Kordestani, Reva K. Basho, Jean-Francois Boileau, Carsten Denkert, Jared C. Foster, Heather A. Jacene, Tari A. King, Ginny Mason, Ciara C. O'Sullivan, Tatiana M. Prowell, Karla A. Sepulveda, Lynn Pearson Butler, Elena I. Schwartz, Larissa A. Korde

Administrative support: Lynn Pearson Butler

Provision of study materials or patients: Sara M. Tolaney, Nadia Harbeck, Ginny Mason

Collection and assembly of data: Jennifer K. Litton, Meredith M. Regan, Sara M. Tolaney, Reva K. Basho, Jared C. Foster, Nadia Harbeck, Tari A. King, Ciara C. O'Sullivan, Tatiana M. Prowell, Andrea L. Richardson, Karla A. Sepulveda, Judy A. Tjoe, Lynn Pearson Butler, Larissa A. Korde

Data analysis and interpretation: Jennifer K. Litton, Meredith M. Regan, Lajos Pusztai, Hope S. Rugo, Sara M. Tolaney, Ana F. Best, Jean-Francois Boileau, Carsten Denkert, Jared C. Foster, Nadia Harbeck, Tari A. King, Ciara C. O'Sullivan, Tatiana M. Prowell, Andrea L. Richardson, Karla A. Sepulveda, Mary Lou Smith, Judy A. Tjoe, Gulisa Turashvili, Wendy A. Woodward

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Standardized Definitions for Efficacy End Points in Neoadjuvant Breast Cancer Clinical Trials: NeoSTEEP

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/jco/authors/author-center.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

Jennifer K. Litton

Honoraria: UpToDate

Consulting or Advisory Role: Pfizer, AstraZeneca, Medivation/Pfizer, Ayala Pharmaceuticals

Speakers' Bureau: Physicians' Education Resource, UpToDate, Med Learning Group, Medscape, Prime Oncology, Clinical Care Options, Medpage

Research Funding: Genentech (Inst), Pfizer (Inst), EMD Serono (Inst), AstraZeneca (Inst), Zenith Epigenetics (Inst), Merck (Inst), GlaxoSmithKline (Inst)

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: UptoDate, Patent Royalty by Certis (Inst)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Physicians' Education Resource, Med Learning Group, Medscape, Clinical Care Options

Other Relationship: Medivation/Pfizer

Meredith M. Regan

Consulting or Advisory Role: Ipsen (Inst), Tolmar, Bristol Myers Squibb, Debiopharm Group (Inst), TerSera, AstraZeneca

Research Funding: Pfizer (Inst), Ipsen (Inst), Novartis (Inst), Merck (Inst), AstraZeneca (Inst), Pierre Fabre (Inst), Bayer (Inst), Bristol Myers Squibb (Inst), Roche (Inst), TerSera (Inst), Debiopharm Group (Inst), BioTheranostics (Inst)

Lajos Pusztai

Honoraria: BioTheranostics, Natera, OncoCyte, Athenex

Consulting or Advisory Role: H3 Biomedicine, Merck, Novartis, Seagen, Syndax, AstraZeneca, Roche/Genentech, Bristol Myers Squibb, Clovis Oncology, Immunomedics, Eisai, Almac Diagnostics, Pfizer

Research Funding: Merck (Inst), Genentech (Inst), Seagen (Inst), AstraZeneca (Inst), Bristol Myers Squibb (Inst), Pfizer (Inst)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: AstraZeneca

Uncompensated Relationships: NanoString Technologies, Foundation Medicine

Open Payments Link: https://openpaymentsdata.cms.gov/physician/110878

Hope S. Rugo

Consulting or Advisory Role: Napo Pharmaceuticals, Puma Biotechnology, Mylan, Eisai, Daiichi Sankyo

Research Funding: OBI Pharma (Inst), Pfizer (Inst), Novartis (Inst), Lilly (Inst), Merck (Inst), Daiichi Sankyo (Inst), Sermonix Pharmaceuticals (Inst), AstraZeneca (Inst), Gilead Sciences (Inst), Astellas Pharma (Inst), Pionyr (Inst), Taiho Oncology (Inst), Veru (Inst), GlaxoSmithKline (Inst), Hoffmann-La Roche AG/Genentech Inc (Inst)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Merck, AstraZeneca, Gilead Sciences

Open Payments Link: https://openpaymentsdata.cms.gov/physician/183398

Sara M. Tolaney

Consulting or Advisory Role: Novartis, Pfizer, Merck, Lilly, AstraZeneca, Genentech, Eisai, Sanofi, Bristol Myers Squibb, Seagen, CytomX Therapeutics, Daiichi Sankyo, Immunomedics/Gilead, 4D Pharma, BeyondSpring Pharmaceuticals, OncXerna Therapeutics, Zymeworks, Zentalis, Blueprint Medicines, Reveal Genomics, ARC Therapeutics, Myovant Sciences, Umoja Biopharma, Menarini Group, AADi, Artios Biopharmaceuticals, Incyte, Zetagen, Bayer

Research Funding: Genentech/Roche (Inst), Merck (Inst), Exelixis (Inst), Pfizer (Inst), Lilly (Inst), Novartis (Inst), Bristol Myers Squibb (Inst), Eisai (Inst), AstraZeneca (Inst), NanoString Technologies (Inst), Cyclacel (Inst), Sanofi (Inst), Seagen (Inst), OncoPep (Inst), Gilead Sciences (Inst)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Lilly, Sanofi

Reva K. Basho

Employment: Alignment Healthcare (I), Apollo Medical Holdings (I), Lawrence J. Ellison Institute for Transformative Medicine

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Alignment Healthcare (I), Apollo Medical Holdings (I), Fresenius (I)

Consulting or Advisory Role: Seagen, Pfizer, Gilead Sciences, AstraZeneca

Speakers' Bureau: Lilly

Research Funding: Seagen (Inst), Merck (Inst), Pfizer (Inst), Takeda (Inst), Lilly (Inst)

Other Relationship: WebMD/Medscape, MJH Healthcare Holdings LLC

Uncompensated Relationships: Novartis, Pfizer, Genentech, AstraZeneca

Jean-Francois Boileau

Consulting or Advisory Role: Roche, Lilly, Pfizer, Merck, Exact Sciences, Novartis, AstraZeneca

Speakers' Bureau: Roche, Novartis, Pfizer, Merck, Exact Sciences, AstraZeneca

Research Funding: Roche (Inst), Novartis (Inst), Pfizer (Inst), AbbVie (Inst), Merck (Inst), Lilly (Inst), Bristol Myers Squibb (Inst), Exact Sciences (Inst), AstraZeneca (Inst)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Roche, Allergan

Carsten Denkert

Consulting or Advisory Role: MSD Oncology, Daiichi Sankyo, Molecular Health, AstraZeneca, Roche, Lilly

Research Funding: Myriad Genetics (Inst), Roche (Inst), German Breast Group (Inst)

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: VMscope digital pathology software, Patent WO2020109570A1, Patent WO2015114146A1, Patent WO2010076322A1

Nadia Harbeck

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: West German Study Group

Honoraria: Roche, Novartis, Pfizer, AstraZeneca, Pierre Fabre, Daiichi-Sankyo, MSD, Seagen, Lilly, Viatris, Sanofi, Zuellig Pharma, Gilead Sciences, Amgen

Consulting or Advisory Role: Novartis, Sandoz, West German Study Group (I), Seagen, Gilead Sciences, Roche/Genentech

Speakers' Bureau: Medscape, Springer Healthcare, EPG Communication

Research Funding: Roche/Genentech (Inst), Lilly (Inst), MSD (Inst), AstraZeneca (Inst)

Heather A. Jacene

Honoraria: Blue Earth Diagnostics, Munrol

Consulting or Advisory Role: Advanced Accelerator Applications, Spectrum Dynamics

Research Funding: GTx (Inst), Siemens Healthineers (Inst), Blue Earth Diagnostics (Inst)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: GE Healthcare

Tari A. King

Honoraria: Genomic Health, Exact Sciences

Consulting or Advisory Role: Genomic Health, Besins Healthcare, Exact Sciences

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Grupo Oncoclinicas

Other Relationship: PrecisCa

Ginny Mason

Consulting or Advisory Role: Novartis Pharmaceuticals UK Ltd (Inst), Novartis (Inst)

Ciara C. O'Sullivan

Honoraria: Seagen (Inst), AstraZeneca (Inst), Medscape (Inst)

Research Funding: Lilly (Inst), Seagen (Inst), Bavarian Nordic (Inst), Academic & Community Cancer Research United (Inst), Sermonix Pharmaceuticals (Inst), Tesaro (Inst), Genentech (Inst), Eisai (Inst), nference (Inst)

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: nference Astra Zeneca (Inst)

Andrea L. Richardson

Consulting or Advisory Role: AstraZeneca, Oliver Wyman Health and Life Sciences Consulting/Marsh McLennan

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: Inventor on HRD assay licensed to Myriad genetics. The IP is designated to Partners Healthcare. I am entitled to royalties and license fees

Mary Lou Smith

Consulting or Advisory Role: Novartis, Pfizer, Bayer (Inst)

Research Funding: Genentech (Inst), Novartis (Inst), Foundation Medicine (Inst), Exact Sciences (Inst), Pfizer (Inst), Seagen (Inst), Lilly (Inst)

Wendy A. Woodward

Honoraria: Exact Sciences

Consulting or Advisory Role: Exact Sciences, Epic Sciences

Open Payments Link: https://openpaymentsdata.cms.gov/physician/440115

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hudis CA, Barlow WE, Costantino JP, et al. : Proposal for standardized definitions for efficacy end points in adjuvant breast cancer trials: The STEEP system. J Clin Oncol 25:2127-2132, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tolaney SM, Garrett-Mayer E, White J, et al. : Updated standardized definitions for efficacy end points (STEEP) in adjuvant breast cancer clinical trials: STEEP version 2.0. J Clin Oncol 39:2720-2731, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bonnefoi H, Litière S, Piccart M, et al. : Pathological complete response after neoadjuvant chemotherapy is an independent predictive factor irrespective of simplified breast cancer intrinsic subtypes: A landmark and two-step approach analyses from the EORTC 10994/BIG 1-00 phase III trial. Ann Oncol 25:1128-1136, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pusztai L, Foldi J, Dhawan A, et al. : Changing frameworks in treatment sequencing of triple-negative and HER2-positive, early-stage breast cancers. Lancet Oncol 20:e390-e396, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.FDA : Pathological Complete Response in Neoadjuvant Treatment of High-Risk Early-Stage Breast Cancer: Use as an Endpoint to Support Accelerated Approval Guidance for Industry. Rockville, MD, US Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration, Oncology Center of Excellence, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER), Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER), 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fumagalli D, Bedard PL, Nahleh Z, et al. : A common language in neoadjuvant breast cancer clinical trials: Proposals for standard definitions and endpoints. Lancet Oncol 13:e240-e248, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cortazar P, Zhang L, Untch M, et al. : Pathological complete response and long-term clinical benefit in breast cancer: The CTNeoBC pooled analysis. Lancet 384:164-172, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Residual Cancer Burden Calculator. The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX. http://www3.mdanderson.org/app/medcalc/index.cfm?pagename=jsconvert3

- 9.Bossuyt V, Provenzano E, Symmans WF, et al. : Invasive Carcinoma of the Breast in the Setting of Neoadjuvant Therapy Histopathology Reporting Guide. 2nd edition. International Collaboration on Cancer Reporting; Sydney, Australia. https://www.iccr-cancer.org/datasets/published-datasets/breast/breast-neoadjuvant-therapy/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spring LM, Fell G, Arfe A, et al. : Pathologic complete response after neoadjuvant chemotherapy and impact on breast cancer recurrence and survival: A comprehensive meta-analysis. Clin Cancer Res 26:2838-2848, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mazouni C, Peintinger F, Wan-Kau S, et al. : Residual ductal carcinoma in situ in patients with complete eradication of invasive breast cancer after neoadjuvant chemotherapy does not adversely affect patient outcome. J Clin Oncol 25:2650-2655, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wong SM, Almana N, Choi J, et al. : Prognostic significance of residual axillary nodal micrometastases and isolated tumor cells after neoadjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 26:3502-3509, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gradishar WJ, Moran MS, Abraham J, et al. : NCCN guidelines® insights: Breast cancer, version 4.2021. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 19:484-493, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chevallier B, Roche H, Olivier JP, et al. : Inflammatory breast cancer. Pilot study of intensive induction chemotherapy (FEC-HD) results in a high histologic response rate. Am J Clin Oncol 16:223-228, 1993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sataloff DM, Mason BA, Prestipino AJ, et al. : Pathologic response to induction chemotherapy in locally advanced carcinoma of the breast: A determinant of outcome. J Am Coll Surg 180:297-306, 1995 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Symmans WF, Peintinger F, Hatzis C, et al. : Measurement of residual breast cancer burden to predict survival after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 25:4414-4422, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Symmans WF, Wei C, Gould R, et al. : Long-term prognostic risk after neoadjuvant chemotherapy associated with residual cancer burden and breast cancer subtype. J Clin Oncol 35:1049-1060, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marczyk M, Mrukwa A, Yau C, et al. : Treatment Efficacy Score-continuous residual cancer burden-based metric to compare neoadjuvant chemotherapy efficacy between randomized trial arms in breast cancer trials. Ann Oncol 33:814-823, 2022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giuliano AE, Edge SB, Hortobagyi GN: Eighth edition of the AJCC cancer staging manual: Breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 25:1783-1785, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ogston KN, Miller ID, Payne S, et al. : A new histological grading system to assess response of breast cancers to primary chemotherapy: Prognostic significance and survival. Breast 12:320-327, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chavez-MacGregor M, Mittendorf EA, Clarke CA, et al. : Incorporating tumor characteristics to the American Joint Committee on Cancer breast cancer staging system. The oncologist 22:1292-1300, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fowler AM, Mankoff DA, Joe BN: Imaging neoadjuvant therapy response in breast cancer. Radiology 285 2:358-375, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mariscotti G, Houssami N, Durando M, et al. : Accuracy of mammography, digital breast tomosynthesis, ultrasound and MR imaging in preoperative assessment of breast cancer. Anticancer Res 34:1219-1225, 2014 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hortobagyi GN, Connolly JL, D'Orsi CJ, et al. : Breast, in AJCC Cancer Staging Manual (ed 8). Chicago, IL, Springer, 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reig B, Lewin AA, Du L, et al. : Breast MRI for evaluation of response to neoadjuvant therapy. Radiographics 41:665-679, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yuan Y, Chen X-S, Liu S-Y, et al. : Accuracy of MRI in prediction of pathologic complete remission in breast cancer after preoperative therapy: A meta-analysis. Am J Roentgenology 195:260-268, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Croshaw R, Shapiro-Wright H, Svensson E, et al. : Accuracy of clinical examination, digital mammogram, ultrasound, and MRI in determining postneoadjuvant pathologic tumor response in operable breast cancer patients. Ann Surg Oncol 18:3160-3163, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sheikhbahaei S, Trahan TJ, Xiao J, et al. : FDG-PET/CT and MRI for evaluation of pathologic response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with breast cancer: A meta-analysis of diagnostic accuracy studies. Oncologist 21:931-939, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Basik M, Cecchini R, De Los Santos J, et al. : Primary analysis of NRG-BR005, a phase II trial assessing accuracy of tumor bed biopsies in predicting pathologic complete response (pCR) in patients with clinical/radiological complete response after neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NCT) to explore the feasibility of breast-conserving treatment without surgery. Cancer Res 80, 2020. (4 suppl; abstr GS5-05). Proceedings of the 2019 San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium, December 10-14, 2019, San Antonio, TX, Philadelphia, PA [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heil J, Pfob A, Sinn HP, et al. : Diagnosing pathologic complete response in the breast after neoadjuvant systemic treatment of breast cancer patients by minimal invasive biopsy: Oral presentation at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium on Friday, December 13, 2019, Program Number GS5-03. Ann Surg 275:576-581, 2022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Loevezijn AA, van der Noordaa MEM, van Werkhoven ED, et al. : Minimally invasive complete response assessment of the breast after neoadjuvant systemic therapy for early breast cancer (MICRA trial): Interim analysis of a multicenter observational cohort study. Ann Surg Oncol 28:3243-3253, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mercado C, Chhor C, Scheel JR: MRI in the setting of neoadjuvant treatment of breast cancer. J Breast Imaging 4:320-330, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Caudle AS, Gonzalez-Angulo AM, Hunt KK, et al. : Predictors of tumor progression during neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 28:1821-1828, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rastogi P, Anderson SJ, Bear HD, et al. : Preoperative chemotherapy: Updates of National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project Protocols B-18 and B-27. J Clin Oncol 26:778-785, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wolmark N, Wang J, Mamounas E, et al. : Preoperative chemotherapy in patients with operable breast cancer: Nine-year results from National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project B-18. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr:96-102, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Haque W, Verma V, Hatch S, et al. : Response rates and pathologic complete response by breast cancer molecular subtype following neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Breast Cancer Res Treat 170:559-567, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang X, Fan Z, Wang X, et al. : Neoadjuvant endocrine therapy for strongly hormone receptor-positive and HER2-negative early breast cancer: Results of a prospective multi-center study. Breast Cancer Res Treat 195:301-310, 2022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Prat A, Saura C, Pascual T, et al. : Ribociclib plus letrozole versus chemotherapy for postmenopausal women with hormone receptor-positive, HER2-negative, luminal B breast cancer (CORALLEEN): An open-label, multicentre, randomised, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 21:33-43, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Semiglazov VF, Semiglazov VV, Dashyan GA, et al. : Phase 2 randomized trial of primary endocrine therapy versus chemotherapy in postmenopausal patients with estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. Cancer 110:244-254, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cottu P, D'Hondt V, Dureau S, et al. : Letrozole and palbociclib versus chemotherapy as neoadjuvant therapy of high-risk luminal breast cancer. Ann Oncol 29:2334-2340, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ma CX, Suman VJ, Leitch AM, et al. : ALTERNATE: Neoadjuvant endocrine treatment (NET) approaches for clinical stage II or III estrogen receptor-positive HER2-negative breast cancer (ER+ HER2- BC) in postmenopausal (PM) women: Alliance A011106. J Clin Oncol 38, 2020. (abstr 504) [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nitz UA, Gluz O, Kümmel S, et al. : Endocrine therapy response and 21-gene expression assay for therapy guidance in HR+/HER2- early breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 40:2557-2567, 2022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smith I, Robertson J, Kilburn L, et al. : Long-term outcome and prognostic value of Ki67 after perioperative endocrine therapy in postmenopausal women with hormone-sensitive early breast cancer (POETIC): An open-label, multicentre, parallel-group, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 21:1443-1454, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ellis MJ, Tao Y, Luo J, et al. : Outcome prediction for estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer based on postneoadjuvant endocrine therapy tumor characteristics. J Natl Cancer Inst 100:1380-1388, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dowsett M, Ebbs SR, Dixon JM, et al. : Biomarker changes during neoadjuvant anastrozole, tamoxifen, or the combination: Influence of hormonal status and HER-2 in breast cancer—A study from the IMPACT trialists. J Clin Oncol 23:2477-2492, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dowsett M, Smith IE, Ebbs SR, et al. : Short-term changes in Ki-67 during neoadjuvant treatment of primary breast cancer with anastrozole or tamoxifen alone or combined correlate with recurrence-free survival. Clin Cancer Res 11:951s-958s, 2005 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nielsen TO, Leung SCY, Rimm DL, et al. : Assessment of Ki67 in breast cancer: Updated recommendations from the International Ki67 in Breast Cancer Working Group. J Natl Cancer Inst 113:808-819, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yau C, Osdoit M, van der Noordaa M, et al. : Residual cancer burden after neoadjuvant chemotherapy and long-term survival outcomes in breast cancer: A multicentre pooled analysis of 5161 patients. Lancet Oncol 23:149-160, 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yeo B, Dowsett M: Neoadjuvant endocrine therapy: Patient selection, treatment duration and surrogate endpoints. Breast 24:S78-S83, 2015. (suppl 2) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ellis MJ, Suman VJ, Hoog J, et al. : Ki67 proliferation index as a tool for chemotherapy decisions during and after neoadjuvant aromatase inhibitor treatment of breast cancer: Results from the American College of Surgeons Oncology Group Z1031 trial (Alliance). J Clin Oncol 35:1061-1069, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Huppert LA, Rugo HS, Pusztai L, et al. : Pathologic complete response (pCR) rates for HR+/HER2- breast cancer by molecular subtype in the I-SPY2 Trial. J Clin Oncol 40, 2022. (abstr 504) [Google Scholar]

- 52.Whitworth P, Stork-Sloots L, de Snoo FA, et al. : Chemosensitivity predicted by BluePrint 80-gene functional subtype and MammaPrint in the Prospective Neoadjuvant Breast Registry Symphony Trial (NBRST). Ann Surg Oncol 21:3261-3267, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wolf DM, Yau C, Sanil A, et al. : DNA repair deficiency biomarkers and the 70-gene ultra-high risk signature as predictors of veliparib/carboplatin response in the I-SPY 2 breast cancer trial. NPJ Breast Cancer 3:31, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pusztai L, Yau C, Wolf DM, et al. : Durvalumab with olaparib and paclitaxel for high-risk HER2-negative stage II/III breast cancer: Results from the adaptively randomized I-SPY2 trial. Cancer Cell 39:989-998.e5, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Allison KH, Hammond MEH, Dowsett M, et al. : Estrogen and progesterone receptor testing in breast cancer: ASCO/CAP guideline update. J Clin Oncol 38:1346-1366, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bear HD, Wan W, Robidoux A, et al. : Using the 21-gene assay from core needle biopsies to choose neoadjuvant therapy for breast cancer: A multicenter trial. J Surg Oncol 115:917-923, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wolf DM, Yau C, Wulfkuhle J, et al. : Redefining breast cancer subtypes to guide treatment prioritization and maximize response: Predictive biomarkers across 10 cancer therapies. Cancer Cell 40:609-623.e6, 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schmid P, Cortes J, Pusztai L, et al. : Pembrolizumab for early triple-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Med 382:810-821, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pusztai L, Denkert C, O'Shaughnessy J, et al. : Event-free survival by residual cancer burden after neoadjuvant pembrolizumab + chemotherapy versus placebo + chemotherapy for early TNBC: Exploratory analysis from KEYNOTE-522. J Clin Oncol 40, 2022. (abstr 503) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schmid P, Cortes J, Dent R, et al. : Event-free survival with pembrolizumab in early triple-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Med 386:556-567, 2022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ueno NT, Espinosa Fernandez JR, Cristofanilli M, et al. : International consensus on the clinical management of inflammatory breast cancer from the Morgan Welch inflammatory breast cancer research program 10th anniversary conference. J Cancer 9:1437-1447, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Devi GR, Hough H, Barrett N, et al. : Perspectives on inflammatory breast cancer (IBC) research, clinical management and community engagement from the duke IBC consortium. J Cancer 10:3344-3351, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chainitikun S, Espinosa Fernandez JR, Long JP, et al. : Pathological complete response of adding targeted therapy to neoadjuvant chemotherapy for inflammatory breast cancer: A systematic review. PLoS One 16:e0250057, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gianni L, Eiermann W, Semiglazov V, et al. : Neoadjuvant chemotherapy with trastuzumab followed by adjuvant trastuzumab versus neoadjuvant chemotherapy alone, in patients with HER2-positive locally advanced breast cancer (the NOAH trial): A randomised controlled superiority trial with a parallel HER2-negative cohort. Lancet 375:377-384, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Diao K, Andring LM, Barcenas CH, et al. : Contemporary outcomes after multimodality therapy in patients with breast cancer presenting with ipsilateral supraclavicular node involvement. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 112:66-74, 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sakai T, Ozkurt E, DeSantis S, et al. : National trends of synchronous bilateral breast cancer incidence in the United States. Breast Cancer Res Treat 178:161-167, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pak LM, Gaither R, Rosenberg SM, et al. : Tumor phenotype and concordance in synchronous bilateral breast cancer in young women. Breast Cancer Res Treat 186:815-821, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Boros M, Marian C, Moldovan C, et al. : Morphological heterogeneity of the simultaneous ipsilateral invasive tumor foci in breast carcinoma: A retrospective study of 418 cases of carcinomas. Pathol Res Pract 208:604-609, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lester SC, Bose S, Chen YY, et al. : Protocol for the examination of specimens from patients with invasive carcinoma of the breast. Arch Pathol Lab Med 133:1515-1538, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Salgado R, Aftimos P, Sotiriou C, et al. : Evolving paradigms in multifocal breast cancer. Semin Cancer Biol 31:111-118, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Boughey JC, Peintinger F, Meric-Bernstam F, et al. : Impact of preoperative versus postoperative chemotherapy on the extent and number of surgical procedures in patients treated in randomized clinical trials for breast cancer. Ann Surg 244:464-470, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kaur MN, Chan S, Bordeleau L, et al. : Re-examining content validity of the BREAST-Q more than a decade later to determine relevance and comprehensiveness. J Patient Rep Outcomes 7:37, 2023. https://qportfolio.org/breast-q/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pusic AL, Klassen AF, Scott AM, et al. : Development of a new patient-reported outcome measure for breast surgery: The BREAST-Q. Plast Reconstr Surg 124:345-353, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Prowell TM, Pazdur R: Pathological complete response and accelerated drug approval in early breast cancer. N Engl J Med 366:2438-2441, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Prowell TM, Beaver JA, Pazdur R: Residual disease after neoadjuvant therapy—Developing drugs for high-risk early breast cancer. N Engl J Med 380:612-615, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]