Abstract

INTRODUCTION:

As liver disease progresses, scarring results in worsening hemodynamics ultimately culminating in portal hypertension. This process has classically been quantified through the portosystemic pressure gradient (PSG), which is clinically estimated by hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG); however, PSG alone does not predict a given patient's clinical trajectory regarding the Baveno stage of cirrhosis. We hypothesize that a patient's PSG sensitivity to venous remodeling could explain disparate disease trajectories.

METHODS:

We created a computational model of the portal system in the context of worsening liver disease informed by physiologic measurements from the field of portal hypertension. We simulated progression of clinical complications, HVPG, and transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt placement while only varying a patient's likelihood of portal venous remodeling.

RESULTS:

Our results unify hemodynamics, venous remodeling, and the clinical progression of liver disease into a mathematically consistent model of portal hypertension. We find that by varying how sensitive patients are to create venous collaterals with rising PSG we can explain variation in patterns of decompensation for patients with liver disease. Specifically, we find that patients who have higher proportions of portosystemic shunting earlier in disease have an attenuated rise in HVPG, delayed onset of ascites, and less hemodynamic shifting after transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt placement.

DISCUSSION:

This article builds a computational model of portal hypertension which supports that patient-level differences in venous remodeling may explain disparate clinical trajectories of disease.

KEYWORDS: computational modeling, portal hypertension, hemodynamics, cirrhosis, natural history

INTRODUCTION

The natural history of cirrhosis involves the progressive scarring of the liver and therefore increased resistance to blood flow through the organ. The end result is portal hypertension that remodels the portal vasculature, alters systemic hemodynamics, and causes life-threatening decompensating events such as ascites and variceal bleeding. Portal hypertension can be graded in severity using the hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG), which is a surrogate marker of the true portosystemic pressure gradient (PSG)—the pressure difference between the portal vein and hepatic vein. Both the clinically measured HVPG and the true PSG are proportional to the hepatic resistance to blood flow and the portal vein inflow as seen in equation 1, below (1).

| (1) |

Where Q is the blood flow, is the pressure drop across the liver, and RLiver is the parenchyma resistance of the diseased liver.

As liver disease progresses, increases in the PSG (and its surrogate, HVPG) are multifactorial and relate to increases in both resistance and splanchnic flow. Parenchymal resistance of the liver (RLiver) is dependent on blood flow through the sinusoids. Collagen deposition in the Disse space culminates in cirrhotic nodule formation disrupting blood flow through the liver (2,3). Extrinsic inflammatory factors such as alcohol exposure (4), steatosis (5), and vascular tone (6) also play a role in increasing resistance. Splanchnic flow Q is dynamic and relates to the autoregulation of the intestine, systemic hemodynamic derangements, and neurohormonal changes that occur in response to worsening portal hypertension and liver dysfunction (7,8). Together, these factors synergistically lead to the physiologic changes seen as liver disease worsens, with both aspects contributing to the rising PSG, although the dynamics of PSG rise in the context of worsening liver disease is not known.

The more clinically used surrogate for PSG, HVPG, has been the cornerstone for the field of portal hypertension, with elevated HVPG a risk factor for variceal bleeding, decompensation, patient survival, perioperative risk, and response to therapy (1,9–12). Chronically elevated portal pressures induce and enlarge portosystemic shunts, prevalent in up to 63.5% of patients with cirrhosis and correlated with poor outcomes (13). These shunts circumvent portal inflow to the liver and can lower PSG while decreasing Q through the liver (equation (1)). Clinically, these shunts can lower PSG by 5–15 mm Hg, interfering with the diagnostic utility of HVPG (14). Besides affecting PSG, the hemodynamic effects of these shunts may be important drivers of progressive hemodynamic complications termed the splanchnic steal phenomenon, but the plausibility of this hypothesis has not been demonstrated (15,16).

Accordingly, some patients present with similar complications of portal hypertension at different levels of HVPG (1,17). For example, disease progression is conventionally modeled in stages: stage 1 (no varices, no ascites), to stage 2 (varices, no ascites), and to stages 3 and 4 (ascites and/or bleeding) (18). However, patients may not follow this progression in a linear fashion, and although HVPG generally increase throughout the stages, there is significant variability in the pressure at which each stage occurs suggesting other factors contribute (19–21). This inadequacy of HVPG as a marker of disease severity may explain the disparate outcomes between patients with similar levels of portal hypertension who undergo transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) placement for varices compared with ascites (22). In addition to these aspects, HVPG fails to estimate presinusoidal components of portal pressure in biliary cirrhosis and other presinusoidal components of portal hypertension. Furthermore, both HVPG and PSG require invasive measurement.

Computational modeling has provided insight into complex dynamics of the cardiovascular system and could provide insight into the progression of portal hypertension (23,24). Previous applications to liver disease have been limited and have not included venous remodeling, which we hypothesize may alter the trajectory of disease. Golse et al generated a digital twin, or a personalized computational model of the patient (25). This application predicted posthepatectomy portal hypertension in patients with cirrhosis undergoing surgical resection for cancer. Although their model was highly complex and tailored to the patient, a simulation that has broader applicability and applies to decompensated patients would be more appropriate to model disease progression. Another study developed a model to simulate blood flow through the portal system and lobes of the liver (26), treating varices as static shunts. This has the disadvantage of overlooking the nonlinear dynamics of venous remodeling. Still others have modeled the formation of ascites at the level of the sinusoids (27) or portal system (28), but these studies primarily focused on the relationship between sinusoidal pressure and ascites generation and did not include shunts at all.

Thus, a more complete hemodynamic understanding of the system could assist clinicians in understanding portal hypertension and its progression. In this article, we develop a computational model of portal hypertension that can simulate disease trajectories for patients with cirrhosis encountered in clinical practice. We hypothesize that the sensitivity of the portosystemic system to undergo venous remodeling in the face of elevated PSG represents a key driver of variability in trajectories of cirrhosis progression and in patient response to TIPS placement.

METHODS

Objective and hypothesis

In this study, we sought to simulate a consistently increasing amount of liver fibrosis ultimately culminating in the presence of portosystemic shunts and ascites. Simulation conditions are set based on parameter ranges from the literature with the goal of creating a meaningful, clinically relevant model of cirrhosis progression (see Supplementary Materials, Supplementary Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/CTG/A938, for parameters). In contrast to previous work, we hypothesize that variability in the remodeling sensitivity of portosystemic shunts in response to rising PSG represents a key driver of differences in trajectories of cirrhosis progression in different patients. Specifically, patients sensitive to PSG will enlarge portosystemic shunts at a faster rate compared with insensitive patients.

Steady-state simulation

For our simulated patient cases, we assumed that there are no other systemic diseases other than progressive liver fibrosis. We assumed that progression of fibrosis occurs slowly enough to allow for steady state of venous remodeling to be reached. In other words, our model is a simulation of the system at each time point after remodeling has been allowed to occur in response to a given level of fibrosis. This approach is reasonable because the progression of liver disease is known to occur on a much longer timescale than venous shunt formation. For instance, patients with portal vein thrombosis have been noted to form new venous systems within 3–5 weeks (29,30) while the median time from compensated cirrhosis diagnosis to decompensation ranging from 5 to more than 10 years in cohort studies (20,31,32). In lieu of a timescale, the level of hepatic vascular resistance represents the degree of progression of disease. The simulation is designed in this way because (i) time to a given level of resistance is known to vary by cause of liver disease that have different rates of disease progression (e.g., viral, alcohol, metabolic, etc) and (ii) our model simulates a steady state at each possible liver resistance. Using an initial baseline value of 4 mm Hg·min/L (i.e., 4 mm Hg HVPG at 1 L/min portal flow, see the Model parameters section), hepatic vascular resistance (RLiver) was gradually increased. For clinical relevance, we chose to display progression to 35 mm Hg·min/L.

Model parameters and setup

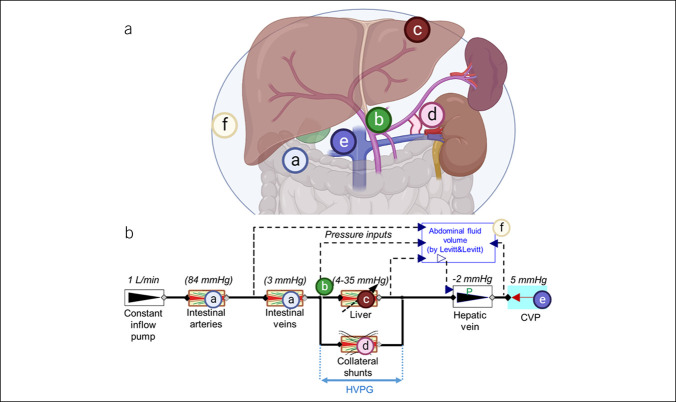

A diagram of the model setup is illustrated in Figure 1. We use 0-D steady-state modeling of isolated splanchnic hemodynamics that begins at the splanchnic arteries (i.e., celiac, superior mesenteric, and inferior mesenteric arteries) and ends in the systemic venous circulation. We assume that the intestinal capillaries receive constant flow to ensure oxygen delivery through perfusion of tissues which we set at 1 L/min. The primary goal of this article was to build a simulation of splanchnoportal hemodynamics and so for initial model building, flow was clamped to this level. We subsequently simulated various input flow levels and patterns to determine the sensitivity of our conclusions to this assumption.

Figure 1.

Anatomy (A) and model setup (B) of the base model (without the TIPS). (a) Intestines, (b) portal vein, (c) liver, (d) shunt, (e) inferior vena cava, and (f) abdominal cavity with ascites. Starting parameters are shown above each component. Created with BioRender.com.

As a basis for our simulator, we used the model previously published by Levitt and Levitt to calculate the steady-state ascites pressure (28). This model consists of resistive components in series (intestinal arteries, intestinal veins, liver, hepatic vein, and assumed central venous pressure) and a model of the peritoneal compartment. When the hepatic vein pressure is lower than the peritoneal pressure, the hepatic vein collapses, increasing its resistance to flow.

The fixed pressure drops assumed by Levitt and Levitt for the liver (6 mm Hg), intestine venules (3 mm Hg), and intestinal arteries were replaced with appropriate resistances so that the pressure drop associated with these components achieves the steady-state values assumed by Levitt and Levitt at the baseline normal inflow of 1 L/min (15,33). Thus, we can observe the change of the pressure drop at different inflow rates. Our model represents an extension of this previously published model, which simulated ascites generation as it is related to portal hemodynamics but did not include shunts.

Novel portosystemic shunt behavior

Most notably, our model incorporates shunt behavior as liver disease progresses which has been theorized to contribute to the hemodynamic derangements of advanced portal hypertension (15,16). This is in comparison to past models that have omitted this major factor or maintained a fixed element to account for all cases (25,26,28,34,35). In this study, we propose that the portosystemic shunting can change as liver disease progresses and that shunt diameter increases as PSG increases. This relationship is well-known clinically and, however, has never before been simulated in the context of portal hemodynamics (36). We term the relationship between PSG and fraction of shunting as the remodeling sensitivity of each patient. In other words, with the same PSG impetus, more sensitive patients may form larger shunts while others who are less sensitive may not. The sensitivity of portosystemic shunts to remodeling should not be confused with minute-to-minute venous compliance, although they share the same units. We represent the behavior of all the portosystemic shunts in a single, lumped resistive compartment. As its luminal diameter increases, the resistance drops according to the Hagen-Poiseuille law as follows:

| (2) |

where Q is the blood flow, is the pressure drop, µ is the dynamic viscosity of the blood, L is the length of the shunt, and r is the actual radius. The shunt is characterized by its linear resistance R, given by the Hagen-Poiseuille law. The actual diameter is calculated from the actual volume as follows:

| (3) |

The actual volume is then given by the shunt's pressure difference Pd (coincides with HVPG) and assumed vessel long-term susceptibility to pressure-dependent remodeling, expressed by the remodeling sensitivity constant Cr.

| (4) |

Vnom is the normal volume, given by the normal diameter rnom as , which in turn is calculated from assumed normal resistance Rnom (1000 mm Hg·min/L) using equation (2). The Pnom is assumed normal healthy pressure difference (8 mm Hg). The value of the remodeling sensitivity constant Cr is varied to explore its predicted effect on the behavior of clinical trajectory. The parameters are listed in Supplementary Table 1 (see Supplementary Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/CTG/A938).

Definitions for stages of cirrhosis

Following the Baveno classification (12), we define the stages of cirrhosis as (i) no ascites present and no portosystemic shunt (varices), (ii) varices present—the shunt receives >10% of the PV flow (100 mL/min given set splanchnic inflow of 1 L/min), (iii) clinically meaningful ascites (over 5 L), and (iv) variceal bleeding as varices present and PSG over 17 mm Hg (10,11,37).

TIPS

TIPS placement is the standard of care for refractory ascites and severe variceal bleeding (38–40). Typical TIPS stents connect the portal vein to hepatic vein with the goal of reducing PSG. To simulate such an effect, we added 1 additional conductance from the portal vein to the hepatic vein, parallel to the liver with assumed resistance of 5 mm Hg·min/L, resulting in reasonable changes in hemodynamics (that is, post-TIPS PSG of about 6.5 mm Hg at pre-TIPS PSG of 15 mm Hg). Because we were interested in short-term TIPS effects, we assumed shunts maintained their pre-TIPS diameter and did not have time to remodel in response to placement.

Experimental setup

We initialized the model in steady state and then gradually increased liver resistance in increments of 2 mm Hg·min/L, mimicking progression of fibrosis, while keeping the inflow constant at 1 L/min. The simulated outputs are PSG, pressure in the portal vein (PPV), abdominal pressure (developed by accumulated ascites), ascites volume, and Baveno stage of cirrhosis for a high and a low value of remodeling sensitivity parameter. Steady-state values were reported (i.e., system free of transients).

In both cases, a simulated TIPS was placed at varying levels of liver resistance and the resultant drop in PSG and portal venous flow to the liver was noted.

Simulations were designed and run in Dymola 2022x, using Modelica Standard Library 4.0 (https://github.com/modelica/ModelicaStandardLibrary) and Physiolibrary v2.5 (https://github.com/filip-jezek/physiolibrary). Source code including model documentation and usage instructions can be found at https://github.com/filip-jezek/ascites. Institutional review board approval was not applicable for this computational study.

RESULTS

Portosystemic shunt remodeling attenuates HVPG rise

After simulation, PSG varied significantly between patients who were PSG-sensitive vs PSG-insensitive remodelers. As liver disease progressed, PSG response can be seen in Figure 2, with end simulation values labeled. Figure 2 illustrates 2 representative cases of the simulated remodeling sensitivity of a patient is continuous, which is continuous and can theoretically span a wide spectrum. Both shunt situations have identical baseline initial conditions with near-zero flow through shunts until diameter rises (prescribed by equation (2)) at a sustained PSG of 5 mm Hg per model starting conditions. PSG-sensitive remodelers are predicted to have lower PSG and PPV as liver disease progressed compared with the insensitive and no-shunt cases. This prediction emerges at each simulated stage of liver disease and is especially prominent in the final simulated stages. An example of a later stage of disease is denoted by the orange line in Figure 2, with PSG decreased by 7–10 mm Hg in insensitive and sensitive patients, respectively. PPV follows a similar ratio, with insensitive and sensitive patients having significant decompression of portal venous pressure. Notably, PSG in both shunted groups rises in a nonlinear fashion, with a plateau of PSG around 25 mm Hg (and 23 mm Hg in the PSG-sensitive group, respectively) at later stages of liver disease despite progression of fibrosis.

Figure 2.

Comparison of flows between representative cases. With increasing liver resistance, increases in PSG (left) and PPV (right) are blunted by remodeled cases compared with no-shunt cases. Patients with more remodeling achieved lower PSG and PPV at all stages. The orange line shows an example of pressures simulated in an advanced disease case. PPV, pressure in portal vein; PSG, portosystemic gradient.

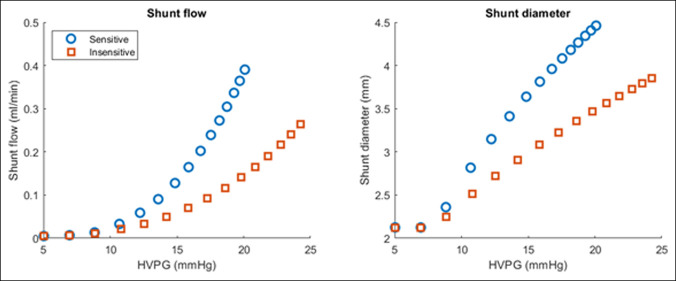

These differences in hemodynamics are further explored in Figure 3. Patients who are PSG sensitive and likely to remodel have higher shunt flow and diameter as PSG rose, with sensitive patients achieving more than 20% higher shunt diameter at PSG of 15 and flow starting in earlier disease, in contrast to the insensitive patient group. These patients have smaller shunt diameter and required a much higher PSG to begin flow through shunts.

Figure 3.

Simulation of collateral shunt flow. With increasing PSG, shunt flow and diameter are higher in patients who are more likely to remodel (PSG-sensitive) patients. HVPG, hepatic venous pressure gradient; PSG, portosystemic gradient.

Extent of remodeling predicts clinical course

Figure 4 shows 2 representative simulations that demonstrate the differences in clinical presentation between PSG-sensitive remodelers (Figure 4A) and PSG-insensitive remodelers (Figure 4B). Specifically, sensitive remodelers displayed in Figure 4A demonstrate a decompensation profile dominated by higher shunt flow (Qs, solid purple dots) and a lower rise in HVPG (blue circles) compared with insensitive patients seen in Figure 4B. Accordingly, these patients experience earlier varices and develop ascites (red squares) later in disease progression. By contrast, the PSG-insensitive remodelers displayed in Figure 4B experience ascites as a presenting symptom, with variceal bleeding occurring later in disease. For instance, at the same HVPG of 15 mm Hg, PSG-sensitive patients would have >100 mL/min of shunt flow, no significant ascites as compared to HVPG-insensitive patients who would have minimal shunt flow and clinically significant ascites. This is consistent with clinical observation in which HVPG alone is not sufficient to predict the portal hypertensive complication type. Regardless of route, both sensitive and insensitive remodelers end at stage 4 disease with symptomatic ascites and variceal bleeding; however, sensitive remodelers have a predicted ascites volume of around 5–7 L in this stage while insensitive patients could potentially generate greater than 10 L. Of course, these are 2 representative simulations, the true PSG-sensitivity factor Cr can be adjusted across a range of values to demonstrate intermediate or extreme phenotypes compared with the illustrated trajectories.

Figure 4.

Two representative cases. As liver disease progresses, HVPG increases nonlinearly. After venous remodeling at each stage, PSG-sensitive (A) cases demonstrate early varices and bleeding compared with insensitive (B) remodelers who present with ascites. At the end of simulation, both groups of patients achieved stage 4 through different trajectories. HVPG, hepatic venous pressure gradient (mm Hg), PSG, portosystemic gradient; Qs, flow though shunts (L/min); VA, volume of ascites (L).

When the sensitivity of the above results to different splanchnic input flows is evaluated, the results are unchanged for assumed flows ranging from 0.5 to 3.0 L/min, except that all the pressures are proportionally scaled (not shown). Specifically, if the splanchnic flow is increased, patients with more venous remodeling continued to show a tendency toward variceal complications compared with ascites complications as seen in Figure 4. Given the known relationship between pressure, flow, and resistance noted in equation (1), the most notable difference in these simulations was the rapidity of progression because at higher flows the modest change in resistance translated to a higher change in PSG.

We encourage the reader to try out different values of sensitivity to remodeling and splanchnic inflow using the web-based simulator at https://filip-jezek.github.io/Ascites/.

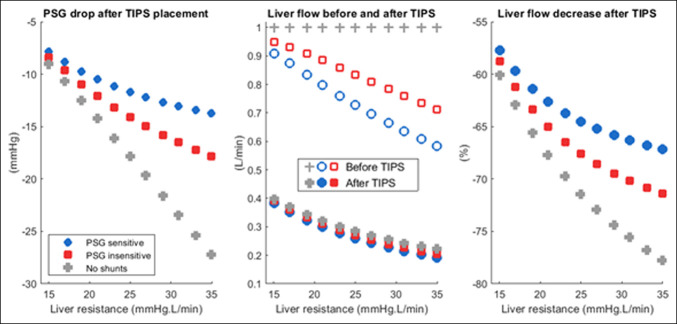

Extent of remodeling predicts portal hemodynamics after TIPS

Results after simulated TIPS placement are displayed in Figure 5. Because TIPS placement is in parallel with natural shunts, PSG drop after TIPS was lower in patients with more pre-TIPS shunt flow, most common among the PSG-sensitive remodelers. After TIPS placement, both PSG-sensitive and PSG-insensitive patients achieved similar residual portal venous flow to the liver. However, in high–shunt flow patients, this was a lower proportional change in portal venous flow to the liver.

Figure 5.

Simulation of TIPS placement. PSG drop after TIPS (left). Patients who had significant portosystemic shunting (PSG-sensitive remodelers, blue) experienced less PSG change after TIPS compared with less remodeled patients (red) and the no-shunt case (gray). Inflow to the liver from the portal vein after TIPS (center). All patients ended up with about the same residual liver flow after TIPS. However, this represents a more significant change for patients with less remodeling or no shunts (right). PSG, portosystemic gradient; TIPS, transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt.

DISCUSSION

Portal hypertension manifests clinically in multiple ways. Understanding the pathophysiology underpinning its heterogeneous phenotypes and clinical courses will empower personalized medical management. To optimize patient outcomes, a deeper knowledge of the patient's physiology may be needed. In this study, we have developed and applied a simulation model which demonstrates that a key determinant of the trajectories of cirrhosis progression is the magnitude of venous remodeling.

Cirrhosis progresses in stages—from no varices and no ascites (stage 1) all the way to ascites and variceal bleeding (stage 4). However, clinically, the transition between stages and the specific reasons for a specific decompensation are less clear (19–21,32,41). For instance, among patients with cirrhosis and varices, D'Amico et al (32) found an 8% annual rate of first decompensation with bleeding versus a 20% annual rate of other events (most commonly ascites), but it is not known why certain patients would present with 1 type of event or another. Similar findings of ascites as a first decompensating event have been described in other large cohorts as well, but in some patients, this is preceded by bleeding (21,41,42). Our study demonstrates that patients who were more sensitive to small increases in PSG were less likely to develop ascites early in their clinical course by undergoing venous remodeling. These patients with remodeling incurred a lesser rise in HVPG and a greater increase in portosystemic shunt flow. Clinically, these patients may have phenotypes that are predominated by variceal bleeding or hepatic encephalopathy rather than ascites. For instance, in a multinational European study, 301 patients with cirrhosis had the cross-sectional area of their largest shunts quantified and their 1 year outcomes measured (43). Patients with shunts of diameter >11 mm had lower rates of ascites and a higher rates of collateral shunt complications (variceal bleeding or hepatic encephalopathy) compared with patients with narrower shunts at 1-year follow-up. In another multinational study of 2,000 patients, large shunts were associated with lower rates of ascites and higher rates of shunt complications such as hepatic encephalopathy (44). As these studies did not measure hepatic resistance directly, patients in the large shunt groups may contain both patients with more advanced parenchymal disease and patients who were more PSG-sensitive and had robust remodeling. The mechanisms for vascular remodeling are not clear, although some translational and animal studies suggest remodeling and angiogenesis is related to vascular endothelial growth factor, placental growth factor, and platelet-derived growth factor release (45–47). Taken together, intrahepatic resistance is a critical component of portal hemodynamic physiology. For these reasons, although predictive of any decompensation, HVPG alone cannot predict which decompensation.

Our analyses support a model of disease trajectory based on 2 opposing competing actions—a patient's rate of worsening liver resistance and their likelihood of creating collateral shunts. As intrahepatic resistance increases, portal vein pressure increases, inflow slows, and portal venous diameter dilates (initially) (36). Collaterals must form to allow venous drainage of the intestines and maintain splanchnic perfusion. The patient continues in a compensated state until (i) collateral flow is overwhelmed and ascites occurs from excess capillary pressure or (ii) a collateral shunt complication occurs (variceal bleeding or hepatic encephalopathy). Both factors can progress past the point of the first decompensation, leading, for example, to Baveno stage 4 cirrhosis (ascites + variceal bleeding).

Although clinical guidelines for predicting and managing portal hypertensive events focus on the HVPG, this single parameter is insufficient to explain why patients present differently and heterogeneity of response to treatment. Our results suggest a subtle but important distinction between elevated HVPG (clinically measured PSG) and intrahepatic resistance. For instance, HVPG-lowering therapy can target decreasing intrahepatic resistance (e.g., alpha blockade or TIPS placement), decreasing flow (beta-blockade or splenic artery embolization), or both. This distinction is apparent in the simulated example of TIPS (Figure 5) in which baseline quantity of collateral shunt flow is predictive of post-TIPS perfusion changes. These findings may explain similar rates of death but higher rates of transplant after TIPS for ascites compared with variceal bleeding indications, perhaps due to more extreme swings in perfusion (22). Similarly, grouping of patients on the basis of HVPG alone may lead to heterogeneous results. For instance, rates of HVPG reduction in response to beta blockers with nitrates were highly variable—1 meta-analysis noted that it was only achieved in around 45% of patients, ranging from 18% to 61% between studies (9). This could also explain why carvedilol, which has effects on both resistance and flow, is superior to older therapies that affect only flow (48). Ultimately, personalized modeling may allow us to infer hepatic resistance as a biomarker to help with trials, treatment, and prognostication. In a corollary to a sudden drop in resistance after TIPS insight can be made about a sudden increase in resistance, in a different clinical scenario—portal vein thrombosis (PVT). Although patients without cirrhosis or portal hypertension often present with signs and symptoms of intestinal ischemia, patients with advanced liver disease often present with no symptoms of PVT or occasionally variceal bleeding. As related to our model, patients with portosystemic shunts who experience a sudden increase in portal vein resistance (i.e., due to PVT) could more easily avoid intestinal ischemia through an increased shunt flow at the potential cost of variceal bleeding.

Our study has several strengths and limitations. First, we do not use actual patient data in our study; however, our goal is not to simulate a specific patient's data but to ensure that the assumptions and physiology were self-consistent when integrated in a unifying model. Furthermore, creation of a digital twin requires invasive measurement of physiologic parameters and acquiring this level of data on the timescale needed to observe the natural history of cirrhosis is impractical (25,34).

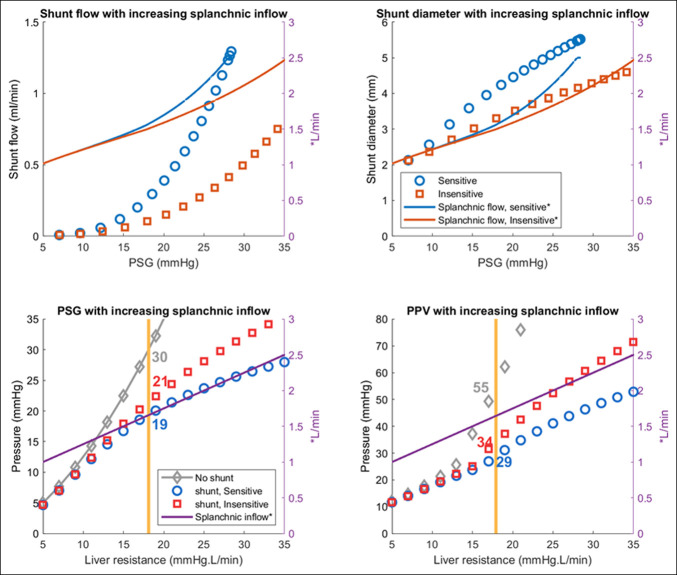

Second, we initially assumed a constant inflow to the splanchnic circulation which empties to portal vein. Although it is well known that total splanchnic flow increases as liver disease progresses (15), we chose to keep this aspect constant for this model as a first step to examine the isolated effect of venous remodeling on PSG trajectory. We investigated this by altering the splanchnic flow rates in both a fixed and ramp fashion. The results were similar in both conditions; however, higher flows are predicted to precipitate earlier progression (Figures 6 and 7).

Figure 6.

Simulation results when splanchnic inflow rates are increased. Arterial inflow was increased throughout the progression of the disease from 1 to 2.5 L/min (extreme case). Patients who are PSG-sensitive remodelers have higher shunt flow (top left), larger shunts (top right), lesser rise in PSG (bottom left), and PPV (bottom right). PPV, pressure in portal vein; PSG, portosystemic gradient.

Figure 7.

Simulation of cirrhotic stages when splanchnic inflow rates are increased. Arterial inflow was increased throughout the progression of the disease from 1 L/min to 2.5 L/min (extreme case). Interpretation of results are unchanged compared with constant inflow assumption but occurred at a faster rate. After venous remodeling at each stage, PSG-sensitive (A) cases demonstrate early varices and bleeding compared with insensitive (B) remodelers who present with ascites. At the end of simulation, both groups of patients achieved stage 4 through different trajectories. PPV, pressure in portal vein; PSG, portosystemic gradient.

Third, our model is intended to be the isolated simulation of the portal system intended to explore the stages of cirrhosis as described in Baveno, but not hepatic encephalopathy (1). Furthermore, we would not be able to account for the significant contributors of liver dysfunction and intestinal microbiome. Fourth, we assume that shunt remodeling and PSG are linearly related. Some studies claim that shunt growth corresponds to shear stress and the wall thickness builds up with the transmural pressure (49). We briefly explored this; however, the simulation does not support that shear stress alone would increase growth of shunts, rather it caused them to close (results not shown). We also investigated remodeling strategy based on transmural pressure without a difference in clinical outcomes (results not shown).

Fifth, in the current study, we model the effect of all shunts lumped into a single component. Given both varices and shunts are exposed to the same PSG and are both venous structures, this served as a simplification of a complex system. Similarly, we assumed simplified conditions regarding turbulent flow, vessel branching, and rate of intrahepatic resistance.

In future work, we hope to couple this model with existing whole-body models to further simulate the changes of end-stage liver disease (23,24). Namely, we hope to show that the classic findings of hyperdynamic circulation and renal hypoperfusion due to effective arterial hypovolemia are a natural result of the findings within this article (7). Furthermore, future studies will incorporate personalized computational modeling with the aim of simulating treatments (beta blockers, diuretics, paracentesis, etc), TIPS, and transplant-related hemodynamic changes.

This study reveals novel insights into the progression of liver disease by incorporating experimental measurements on portal flow, venous remodeling, and variceal bleeding into an interactive, unified physiological model. We demonstrate that although PSG and its surrogate, HVPG, remain a crucial marker of portal hypertension, the full range of clinical presentations is best represented when PSG sensitivity toward venous remodeling is taken into account. Altering this single parameter allows a consistent and flexible explanation for these phenotypes and in this way augments our understanding of the progression through the stages of cirrhosis.

Developing such a model provides a useful tool in illustrating and probing complex interactions between hepatic hemodynamics, ascites formation, and variceal status during the progression of cirrhosis. We encourage the reader to try out different values of sensitivity to remodeling and splanchnic inflow using the web-based simulator at https://filip-jezek.github.io/Ascites/. The model source codes can be downloaded from https://github.com/filip-jezek/Ascites.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Guarantor of the article: Nikhilesh R. Mazumder, MD, MPH.

Specific author contributions: N.R.M., F.J., E.B.T., and D.A.B.: conception of project. N.R.M., F.J. and E.B.T.: literature review. N.R.M., F.J., and D.A.B.: contribution of materials/methods and data analysis. N.R.M., F.J., E.B.T., and D.A.B.: interpretation of results and write up and revision of the manuscript. All authors have been involved in revising the content of this work in preparation for manuscript submission and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work. All authors have given final approval for submission.

Financial support: None to report.

Potential competing interests: F.J. provides occasional training on Modelica language through Creative Connections s.r.o, which supports development of the simulator used in this article. The other authors have nothing to declare.

Study Highlights.

WHAT IS KNOWN

✓ Patients with cirrhosis present with different patterns of complications.

WHAT IS NEW HERE

✓ We created a computational model that simulates the various phenotypes of decompensated cirrhosis. We find that by modifying how sensitive patients are to creating venous collaterals we can explain the heterogeneity of decompensation.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The web simulator accompanying the model is developed using an open-source Bodylight.js framework, with kind technical support of the Creative Connections s.r.o.

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL accompanies this paper at http://links.lww.com/CTG/A938

Nikhilesh R. Mazumder and Filip Jezek are co-first authors.

Contributor Information

Filip Jezek, Email: fjezek@umich.edu.

Elliot B. Tapper, Email: etapper@med.umich.edu.

Daniel A. Beard, Email: beardda@med.umich.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.de Franchis R, Bosch J, Garcia-Tsao G, et al. ; Baveno VII Faculty. Baveno VII: Renewing consensus in portal hypertension. J Hepatol 2022;76(4):959–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Orrego H, Blendis L, Crossley I, et al. Correlation of intrahepatic pressure with collagen in the Disse space and hepatomegaly in humans and in the rat. Gastroenterology 1981;80(3):546–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Picchiotti R, Mingazzini PL, Scucchi L, et al. Correlations between sinusoidal pressure and liver morphology in cirrhosis. J Hepatol 1994;20(3):364–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Luca A, Garcia-Pagan J, Bosch J, et al. Effects of ethanol consumption on hepatic hemodynamics in patients with alcoholic cirrhosis. Gastroenterology 1997;112(4):1284–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mendes FD, Suzuki A, Sanderson SO, et al. Prevalence and indicators of portal hypertension in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012;10(9):1028–33.e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Navasa M, Chesta J, Bosch J, et al. Reduction of portal pressure by isosorbide & mononitrate in patients with cirrhosis effects on splanchnic and systemic hemodynamics and liver function. Gastroenterology 1989;96(4):1110–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oliver JA, Verna EC. Afferent mechanisms of sodium retention in cirrhosis and hepatorenal syndrome. Kidney Int 2010;77(8):669–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Møller S, Hove JD, Dixen U, et al. New insights into cirrhotic cardiomyopathy. Int J Cardiol 2013;167(4):1101–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.D'Amico G, Garcia-Pagan JC, Luca A, et al. Hepatic vein pressure gradient reduction and prevention of variceal bleeding in cirrhosis: A systematic review. Gastroenterology 2006;131(5):1611–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ripoll C, Bañares R, Rincón D, et al. Influence of hepatic venous pressure gradient on the prediction of survival of patients with cirrhosis in the MELD Era. Hepatology 2005;42(4):793–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ripoll C, Groszmann R, Garcia-Tsao G, et al. Hepatic venous pressure gradient predicts clinical decompensation in patients with compensated cirrhosis. Gastroenterology 2007;133(2):481–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.D'Amico G, Garcia-Tsao G, Pagliaro L. Natural history and prognostic indicators of survival in cirrhosis: A systematic review of 118 studies. J Hepatol 2006;44(1):217–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nardelli S, Riggio O, Turco L, et al. Relevance of spontaneous portosystemic shunts detected with CT in patients with cirrhosis. Radiology 2021;299(1):133–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ma J, Gong X, Luo J, et al. Impact of intrahepatic venovenous shunt on hepatic venous pressure gradient measurement. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2020;31(12):2081–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McAvoy NC, Semple S, Richards JMJ, et al. Differential visceral blood flow in the hyperdynamic circulation of patients with liver cirrhosis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2016;43(9):947–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Newby DE, Hayes PC. Hyperdynamic circulation in liver cirrhosis: Not peripheral vasodilatation but ‘splanchnic steal.’ QJM 2002;95(12):827–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morrison JD, Mendoza-Elias N, Lipnik AJ, et al. Gastric varices bleed at lower portosystemic pressure gradients than esophageal varices. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2018;29(5):636–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garcia-Tsao G, D'Amico G, Abraldes JG, et al. Session 2: Predictive models in portal hypertension. In Portal Hypertension IV. Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, 2007, pp 47–102 [Google Scholar]

- 19.D'Amico G, Morabito A, Pagliaro L, et al. Survival and prognostic indicators in compensated and decompensated cirrhosis. Dig Dis Sci 1986;31(5):468–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.D'Amico G, Morabito A, D'Amico M, et al. Clinical states of cirrhosis and competing risks. J Hepatol 2018;68(3):563–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ginés P, Quintero E, Arroyo V, et al. Compensated cirrhosis: Natural history and prognostic factors. Hepatology 1987;7(1):122–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boike JR, Mazumder NR, Kolli KP, et al. Outcomes after TIPS for ascites and variceal bleeding in a contemporary era-an ALTA group study. Am J Gastroenterol 2021;116(10):2079–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ježek F, Kulhánek T, Kalecký K, et al. Lumped models of the cardiovascular system of various complexity. Biocybernet Biomed Eng 2017;37(4):666–78. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jezek F, Randall EB, Carlson BE, et al. Systems analysis of the mechanisms governing the cardiovascular response to changes in posture and in peripheral demand during exercise. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2022;163:33–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Golse N, Joly F, Combari P, et al. Predicting the risk of post-hepatectomy portal hypertension using a digital twin: A clinical proof of concept. J Hepatol 2021;74(3):661–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang T, Liang F, Zhou Z, et al. A computational model of the hepatic circulation applied to analyze the sensitivity of hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG) in liver cirrhosis. J Biomech 2017;65:23–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meedejpraserth N, Leungchavaphongse K. Mathematical modeling of ascites formation in liver diseases. ICBBS '18: Proceedings of the 2018 7th International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedical Science, June 2018, pp 53–58.

- 28.Levitt DG, Levitt MD. Quantitative modeling of the physiology of ascites in portal hypertension. BMC Gastroenterol 2012;12(1):26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.De Gaetano AM, Lafortune M, Patriquin H, et al. Cavernous transformation of the portal vein: Patterns of intrahepatic and splanchnic collateral circulation detected with Doppler sonography. Am J Roentgenol 1995;165(5):1151–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ohnishi K, Okuda K, Ohtsuki T, et al. Formation of hilar collaterals or cavernous transformation after portal vein obstruction by hepatocellular carcinoma: Observations in ten patients. Gastroenterology 1984;87(5):1150–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Merli M, Nicolini G, Angeloni S, et al. Incidence and natural history of small esophageal varices in cirrhotic patients. J Hepatol 2003;38(3):266–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.D'Amico G, Pasta L, Morabito A, et al. Competing risks and prognostic stages of cirrhosis: A 25-year inception cohort study of 494 patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2014;39(10):1180–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Iwao T, Toyonaga A, Sumino M, et al. Portal hypertensive gastropathy in patients with cirrhosis. Gastroenterology 1992;102(6):2060–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Golse N, Joly F, Nicolas Q, et al. Partial orthotopic liver transplantation in combination with two-stage hepatectomy: A proof-of-concept explained by mathematical modeling. Clin Biomech 2020;73:195–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhaleev TR, Kubyshkin VA, Mukhin SI, et al. Mathematical modeling of the blood flow in hepatic vessels. Comput Math Model 2019;30(4):364–77. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhou HY, Chen Tw, Zhang Xm, et al. Patterns of portosystemic collaterals and diameters of portal venous system in cirrhotic patients with hepatitis B on magnetic resonance imaging: Association with Child-Pugh classifications. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol 2015;39(3):351–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moben AL, Alam MA, Noor E Alam SM, et al. Hepatic venous pressure gradient measurement in Bangladeshi cirrhotic patients: A correlation with child's status, variceal size, and bleeding. Euroasian J Hepatogastroenterol 2017;7(2):142–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Boike JR, Thornburg BG, Asrani SK, et al. North American practice-based recommendations for transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts in portal hypertension. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2022;20(8):1636–62.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Salerno F, Cammà C, Enea M, et al. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt for refractory ascites: A meta-analysis of individual patient data. Gastroenterology 2007;133:825–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.García-Pagán JC, Caca K, Bureau C, et al. Early use of TIPS in patients with cirrhosis and variceal bleeding. N Engl J Med 2010;362(25):2370–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Saunders JB, Walters JRF, Davies AP, et al. A 20-year prospective study of cirrhosis. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1981;282(6260):263–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jindal A, Bhardwaj A, Kumar G, et al. Clinical decompensation and outcomes in patients with compensated cirrhosis and a hepatic venous pressure gradient ≥20 mm Hg. Am J Gastroenterol 2020;115(10):1624–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Praktiknjo M, Simón-Talero M, Römer J, et al. Total area of spontaneous portosystemic shunts independently predicts hepatic encephalopathy and mortality in liver cirrhosis. J Hepatol 2020;72(6):1140–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Simón-Talero M, Roccarina D, Martínez J, et al. Association between portosystemic shunts and increased complications and mortality in patients with cirrhosis. Gastroenterology 2018;154(6):1694–705.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Serrano CA, Ling S, Verdaguer S, et al. Portal angiogenesis in chronic liver disease patients correlates with portal pressure and collateral formation. Dig Dis 2019;37(6):498–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fernandez M. Molecular pathophysiology of portal hypertension. Hepatology 2015;61(4):1406–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bolognesi M, Di Pascoli M, Verardo A, et al. Splanchnic vasodilation and hyperdynamic circulatory syndrome in cirrhosis. World J Gastroenterol 2014;20(10):2555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Villanueva C, Albillos A, Genescà J, et al. β blockers to prevent decompensation of cirrhosis in patients with clinically significant portal hypertension (PREDESCI): A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial. Lancet 2019;393(10181):1597–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pries AR, Reglin B, Secomb TW. Remodeling of blood vessels. Hypertension 2005;46(4):725–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]