Abstract

Purpose

Multifocal/multicentric glioblastomas (mGBM) account for up to 20% of all newly diagnosed glioblastomas. The present study investigates the impact of cytoreductive surgery on survival and functional outcomes in patients with mGBM.

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed clinical and imaging data of 71 patients with newly diagnosed primary (IDH1 wildtype) mGBM who underwent operative treatment in 2015–2020 at the authors’ institution. Multicentric/multifocal growth was defined by the presence of ≥ 2 contrast enhancing lesions ≥ 1 cm apart from each other.

Results

36 (50.7%) patients had a resection and 35 (49.3%) a biopsy procedure. MGMT status, age, preoperative KPI and NANO scores as well as the postoperative KPI and NANO scores did not differ significantly between resected and biopsied cases. Median overall survival was 6.4 months and varied significantly with the extent of resection (complete resection of contrast enhancing tumor: 13.6, STR: 6.4, biopsy: 3.4 months; P = 0.043). 21 (58.3%) of resected vs. only 12 (34.3%) of biopsied cases had radiochemotherapy (p = 0.022). Multivariate analysis revealed chemo- and radiotherapy and also (albeit with smaller hazard ratios) extent of resection (resection vs. biopsy) and multicentric growth as independent predictors of patient survival. Involvement of eleoquent brain regions, as well as neurodeficit rates and functional outcomes did not vary significantly between the biopsy and the resection cohorts.

Conclusion

Resective surgery in mGBM is associated with better survival. This benefit seems to relate prominently to an increased number of patients being able to tolerate effective adjuvant therapies after tumor resections. In addition, cytoreductive surgery may have a survival impact per se.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11060-023-04410-7.

Keywords: Multifocal, Multicentric, Glioblastoma, Resection, Biopsy, Growth patterns

Introduction

Glioblastoma has been conceptualized as a systemic brain disease with a somewhat circumscribed beginning, which therefore can often be successfully treated initially with local measures such as surgery and radiotherapy [1]. However, approximately 20% of cases already present with multifocal and/or multicentric disease (mGBM) [2–8]. Multifocal glioblastoma is usually defined by MR imaging showing several contrast enhancing lesions connected by FLAIR hyperintense signal thought to represent tumor infiltration, i.e. migrating tumor cells (as opposed to multicentric disease in which these FLAIR bridges are absent) [2, 3, 5, 9–11].

Current neuro-oncological therapies rest heavily on a tissue and even molecular diagnosis. Hence, obtaining some tissue is mandatory in all glioblastoma cases including patients with multifocal/multicentric disease. The role of additional resective surgery for a circumscribed glioblastomas is well established [12, 13]. However, in everyday clinical practice also many cases with mGBM undergo cytoreductive surgery. This is usually based on the assumption that the traditional “all or nothing” rationale for glioblastoma surgery is an improper simplification of a more complex relation [12–18]. Patients are believed to derive some benefit already from a subtotal tumor removal even if these effects are smaller than the survival impact of a complete resection. There are important technical challenges and restrictions. Extensive resections are usually quite difficult or even impossible to achieve when one is confronted with multiple lesions in different parts of the brain.

In view of these issues we have analyzed our recent institutional experience with the surgical management of patients with mGBM. To this end, we compared patient survival following resective vs. bioptic surgery. We also studied various growth and spread patterns, as well as clinical parameters as possible prognostic predictors, and we assessed functional outcomes.

Patients and methods

Patients and clinical data

We identified 434 patients > 18 years of age undergoing their first surgery in our department for a histologically confirmed glioblastoma from January 2015 to December 2020 in our institutional database. Preoperative imaging data and radiological reports were reviewed and patients were included in the present study if they were found to harbor a multifocal or multicentric tumor (for criteria and radiological data, please see below), and if the neuropathological studies diagnosed a IDH-wildtype glioblastoma, i.e. if at least immunohistochemical studies had been performed showing no expression of mutant IDH1. The final study cohort comprised 71 cases.

Clinical data were collected retrospectively from the patients’ charts. If required patients were also contacted by phone. Progression was defined as institution of a new oncological treatment or of palliative care. Functional outcomes were assessed using the postsurgical (discharge) KPI and NANO scores [19], and the occurrence of surgical, non-temporary neurological or medical complications. The severity of complications was graded using the CTCAE scheme [20] and neurological complications were considered temporary if they resolved within 30 day [21].

Surgical treatment

All cases were discussed in our interdisciplinary neuro-oncological tumor conference. Throughout the study period we offered diagnostic surgery to all patients with a presumed mGBM if patient age and clinical performance status appeared to allow for adjuvant therapy following operative treatment. A tumor resection rather than a biopsy was recommended for large and symptomatic lesions on an individual basis. Open navigation-guided microsurgical rather than stereotactic biopsies were performed for selected non-eloquent and superficially located lesions. A robotic system (neuromate®, Renishaw GmbH, Pliezhausen, Germany) was employed for stereotactic bioptic surgery. We have recently published the technical details and a critical evaluation of the procedure [22]. Surgical adjuncts such as ALA fluorescence, neuromonitoring and awake craniotomies were used for resective surgery as required by lesion location and extension, and deemed useful and/or necessary by the operating surgeon.

Radiological data review volumetry

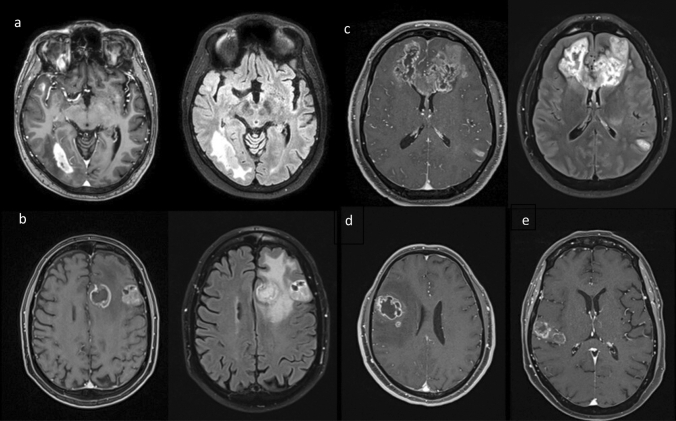

The preoperative MRI studies from all 71 cases were subjected to a neuroradiological review. The designation mGBM required the presence of two or more contrast-enhancing lesions separated by > 1 cm. Cases with only a “perilesional” or “satellite” growth pattern with several discrete lesions but < 1 cm apart from each other were excluded from our analysis [2, 3, 7]. A FLAIR hyperintense signal connecting two lesions defined a multifocal growth pattern, and the lack thereof multicentric spread. Hence, a case with three or more lesions could be categorized as showing both multifocal and multicentric growth if only some of the foci were found to be joined by FLAIR hyperintense tissue (Fig. 1). We also documented bihemispheral, periventricular (< 1 cm distance of a contrast enhancing mass from the ventricle) and pericallosal growth (contrast enhancing tumor within the corpus callosum or within 1 cm from its lateral edge defined by the superolateral border of the lateral ventricle), as well as subarachnoid or subependymal spread (Supplementary Fig. 1) [2, 7].

Fig. 1.

Radiological characteristics of multicentric and multifocal growth patterns. a T1 with contrast and FLAIR weighted MR scans showing two contrast enhancing lesions separated by > 1 cm without a T2/FLAIR bridge—multicentric growth pattern. b T1 and FLAIR weighted images with two contrast enhancing lesions separated by > 1 cm connected by a FLAIR hyperintense signal—multifocal growth pattern. c T1 and FLAIR weighted scans depicting three contrast enhancing foci (and possibly a fourth FLAIR hyperintense lesion in the left thalamus). There is a FLAIR hyperintense signal connecting the frontal foci, but no such bridge between the left temporodorsal tumor manifestation and the other lesions—simultaneous multicentric and multifocal growth pattern. d T1 weighted scan with a smaller contrast enhancing lesion located within 1 cm of the main lesion—unifocal growth pattern with satellite lesion. e T1 weighted image showing two contrast enhancing lesions of similar size within 1 cm of one another—unifocal growth pattern

In order to evaluate the respective patient’s tumorload, we counted contrast enhancing measurable lesions > 1 cm following the RANO criteria [23] and used computer-assisted volumetric analyses of the contrast enhancing tissues employing a well-established computer software (iplanNet, Brainlab AG, Munich, Germany). Location was assessed as involvement of one or more of the following regions: frontal, temporal, parietal and occipital lobe, the cerebellum, brainstem and/or deep midline structures (insula, basal ganglia, thalamus, hypothalamus, internal capsule). All measurable lesions were scored for possible eloquence using the three-tiered scheme originally described by Sawaya et al. [24] and also separately for motor, speech and/or visual pathways eloquence [25]. Cases were assigned to the respective eloquence categories based on the most eloquent tumor manifestation.

Statistical analysis

Routine statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (Version 25.0, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). Two-sided tests were employed throughout. We considered p values < 0.05 as significant. Survival was studied with Kaplan Meier estimates. We employed Cox regression modelling (inclusion procedure) for multivariate survival analyses.

Results

Patient demographics and clinical presentation

We analyzed a total of N = 71 patients (Table 1). Clinical presentation included a reduced KPI ≤ 70 in 23 (32.4%), a NANO score of 3 or more in 36 (50.7%), and seizures in 25 (35.2%) patients.

Table 1.

Demographics, radiological and treatment data

| Characteristics | Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | Age (years) | Mean ± SD (yrs.) | 66.7 ± 13.3 |

| Median (25–75% IQR, yrs.) | 69.0 (58.0–78.0) | ||

| Sex | Male | 36 (50.7%) | |

| Female | 35 (49.3%) | ||

| Preoperative KPI | Mean ± SD | 77.5 ± 15.7 | |

| Median (25–75% IQR) | 80 (70–90) | ||

| Preoperative NANO score | Mean ± SD | 2.85 ± 2.29 | |

| Median (25–75% IQR) | 3 (1–4) | ||

| Postoperative KPI |

Mean ± SD Median (25–75% IQR) |

77.0 ± 17.7 80 (70–90) |

|

| Postoperative NANO |

Mean ± SD Median (25–75% IQR) |

2.89 ± 2.47 2 (1–4) |

|

| Preoperative seizures | Yes | 25 (35.2%) | |

| No | 46 (64.8%) | ||

| MGMT promoter hypermethylationa | Yes | 27 (38.0%) | |

| No | 34 (47.9%) | ||

| Radiological data | |||

| Growth pattern | Multicentric | Yes | 26 (36.6%) |

| No | 45 (63.4%) | ||

| Multifocal | Yes | 54 (76.1%) | |

| No | 17 (23.9%) | ||

| Spread | Bilateral | Yes | 37 (52.1%) |

| No | 34 (47.9%) | ||

| Periventricular | Yes | 64 (90.1%) | |

| No | 7 (9.9%) | ||

| Pericallosal | Yes | 53 (74.6%) | |

| No | 18 (25.4%) | ||

| Subarachnoid | Yes | 12 (16.9%) | |

| No | 59 (83.1%) | ||

| Subependymal | Yes | 12 (16.9%) | |

| No | 59 (16.9%) | ||

| “butterfly”b | Yes | 35 (49.3%) | |

| No | 36 (50.7%) | ||

| Tumor localization | Frontal | Yes | 51 (71.8%) |

| No | 20 (28.2%) | ||

| Parietal | Yes | 44 (62.0%) | |

| No | 27 (38.0%) | ||

| Temporal | Yes | 34 (47.9%) | |

| No | 37 (52.1%) | ||

| Occipital | Yes | 17 (23.9%) | |

| No | 54 (76.1%) | ||

| Insula, basal ganglia, (hypo)thalamus | Yes | 33 (46.5%) | |

| No | 38 (53.5%) | ||

| Cerebellum | Yes | 5 (7.0%) | |

| No | 66 (93.0%) | ||

| Brainstem | Yes | 4 (5.6%) | |

| No | 67 (94.4%) | ||

| Eloquence | Overall | ≥ 1 eloquent lesion | 41 (57.7%) |

| ≥ 1 near-eloquent, but no eloquent lesion | 21 (29.6%) | ||

| No (near) eloquent lesion(s) | 9 (12.7%) | ||

| ≥ 1 any motor eloquent lesion | Yes | 24 (33.8%) | |

| No | 47 (66.2%) | ||

| ≥ 1 speech eloquent lesion | Yes | 12 (16.9%) | |

| No | 59 (83.1%) | ||

| ≥ 1 visual pathways eloquent lesion | Yes | 26 (36.6%) | |

| No | 45 (63.4%) | ||

| Tumorload | Lesion no. |

Mean ± SD Median (25–75% IQR) |

2.94 ± 2.10 2 (1–3) |

| Preoperative tumorload (volume) |

Mean ± SD Median (25–75% IQR, ml) |

23.3 ± 20.5 17.3 (8.1–31.9) |

|

| Postoperative tumorload (volume) |

Mean ± SD (ml) Median (25–75% IQR, ml) |

10.6 ± 15.0 4.5 (0.3–15.0) |

|

| Treatment data | |||

| Operative treatment | Type of operation | Complete resection (postop. contrast enhancing tumor volume < 0.1 ml) | 13 (18.3%) |

| STR | 23 (32.4%) | ||

| Biopsy | 35 (49.3%) | ||

| Extent of resection |

Mean ± SD Median (25–75% IQR, %) |

45.1 ± 46.9% 25.0 (0-98.4) |

|

| Adjuvant therapy | Radiotherapy | Completed | 38 (53.5%) |

| Incomplete | 10 (14.1%) | ||

| None | 23 (32.4%) | ||

| Chemotherapy | Yes | 40 (56.3%) | |

| No | 31 (43.7%) | ||

| Radiochemotherapy | RT completed, TMZ or TMZ/CCNU | 33 (46.5%) | |

| RT incomplete or monotherapy | 16 (22.5%) | ||

| None | 22 (31.0%) |

aN = 61

b“butterfly” = bihemspheric contrast enhancing pericallosal disease

SD standard deviation, IQR interquartile range, KPI Karnofsky performance index, NANO neurologic assessment in neuro-oncology, MGMT O(6)-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase, STR subtotal resection, RT Radiotherapy, TMZ Temozolomide, CCNU Lomustine

Tumor growth patterns and spread

The preoperative MR imaging studies showed multifocal disease in 54 (76.1%) cases and multicentric tumor growth in 26 (36.6%; both: N = 9, 12.7%) (Fig. 1). Bilateral contrast enhancing lesions were seen in 37 (52.1%) patients. Twenty-six (36.6%) patients had ≥ 3 discrete and measurable lesions, and in nine patients the MR scans showed non-measurable disease. Forty-one patients presented with eloquent (57.7%), and 21 cases (29.6%) with near-eloquent tumor manifestations. Motor, language and visual pathway eloquent lesions were seen in 24 (33.8%), 12 (16.9%) and 26 (36.6%) of patients (Table 1).

Surgical management and functional outcomes

Thirty-six patients (50.7%) had tumor resections. In 14 cases we aimed at a complete resection of two (13) or three (1) contrast enhancing tumors during the same surgery (unilateral disease: 11; bifrontal paramedian disease: 3). The remaining 22 patients (uni-/bilateral disease: 10/12, > 2 lesions: 6) had a resection of the largest lesion only, i.e. a planned subtotal resection of the contrast enhancing tissues. The overall mean extent of resection was 45.1 ± 46.9% (median: 25.0, IQR: 0-98.4%), but 88.9 ± 19.8% (median 98.2, IQR: 87.4–100%) in the resective cohort. This includes 13 (36.1%) cases with a complete resection (defined by < 0.1 ml contrast enhancing signal in the early postoperative MR study). Four patients (5.6%) underwent an open microsurgical biopsy and stereotactic (roboter-guided) biopsies were performed in 31 cases (43.7%).

Four cases incurred CTCAE grades 3–5 new or worsened postoperative neurological deficits persisiting ≥ 30 days (5.6%; resection: N = 3, biopsy: N = 1), and five patients CTCAE grades 3–5 local/surgical complications (7.0%; resection: N = 3, biopsy: N = 2; including one brain abscess 3 months after surgery for temporal lobe glioblastoma and three hemorrhages). One case with a VP shunt implanted for normal pressure hydrocephalus required an operative shunt revision for shunt malfunction 13 days after a stereotactic biopsy. 30 days mortality was 4/71 (5.6%) with one patient dying from gastrointestinal bleeding 11 days following surgery, two from progressive tumors, and one from unknown causes. Median preoperative KPI and NANO scores were 80 (25–75% IQR: 20–100) and 3 (25–75% IQR: 1–4); the respective postoperative figures were 80 (25–75% IQR: 20–100) and 2 (25–75% IQR: 1–4). Only two cases (2.8%) had a postoperative ≥ 20 drop of their KPI score, and all neurologically intact patients retained their preoperative NANO score of 0.

Follow-up, adjuvant treatment and survival outcomes

Median follow-up was 5.2 (mean: 7.8 ± 8.0) months with 62 patients (87.3%) followed until death. Postoperative radiotherapy was started in 48 (67.6%) and completed in 38 cases (53.5%). Forty patients (56.3%) had chemotherapy (all temozolomide, including three cases with CCNU/temozolomide combination chemotherapy [26]), and 33 (46.5%) had radiochemotherapy. Radiotherapy only was administered in 9 (12.7%) patients. Median overall survival was 6.4 (95% CI: 4.2–8.5) months, and median progression free survival was 4.1 (95% CI: 3.0-5.2) months.

Of note, the frequency and intensity of adjuvant treatment varied markedly between cases undergoing cytoreductive vs. bioptic surgery. E.g. 24/36 (66.7%) cases completed their course of radiotherapy following cytoreductive surgery vs. only 14/35 (40.0%; P = 0.028) after a biopsy procedure. Radiochemotherapy [26, 27] was given in 21/36 (58.3%) resective cases but only in 12/35 (34.3%; P = 0.022) of biopsy patients (Table 2).

Table 2.

Demographics, radiological and treatment characteristics in the resection vs. biopsy cohorts

| Characteristics | Resection | Biopsy | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | Age | ≤ 69 yrs. (median) | 20 (54.1%) | 17 (45.9%) | NS |

| > 69 yrs. | 16 (47.1%) | 18 (52.9%) | |||

| Sex | Female | 17 (48.6%) | 18 (51.4%) | NS | |

| Male | 19 (52.8%) | 17 (47.2%) | |||

| Preoperative KPI | 80–100 | 26 (54.2%) | 22 (45.8%) | NS | |

| < 80 | 10 (43.5%) | 13 (56.5%) | |||

| Postoperative KPI | 80–100 | 26 (54.2%) | 22 (45.8%) | NS | |

| < 80 | 10 (43.5%) | 13 (56.5%) | |||

| Preoperative NANO score | 0–2 | 14 (40.0%) | 21 (60.0%) | NSb | |

| > 2 | 22 (61.1%) | 14 (38.9%) | |||

| Postoperative NANO score | 0–2 | 20 (57.1%) | 15 (42.9%) | NS | |

| > 2 | 16 (44.4%) | 20 (55.6%) | |||

| Preoperative seizures | Yes | 15 (60.0%) | 10 (40.0%) | NS | |

| No | 21 (45.7%) | 25 (54.3%) | |||

| MGMT promoter hypermethylationa | Positive | 16 (59.3%) | 11 (40.7%) | NS | |

| Negative | 15 (44.1%) | 19 (55.9%) | |||

| Radiological data | |||||

| Growth pattern | Multicentric | Yes | 13 (50.0%) | 13 (50.0%) | NS |

| No | 23 (51.1%) | 22 (48.9%) | |||

| Multifocal | Yes | 27 (50.0%) | 27 (50.0%) | NS | |

| No | 9 (52.9%) | 8 (47.1%) | |||

| Spread | Bilateral | Yes | 15 (40.5%) | 22 (59.5%) | NSc |

| No | 21 (61.8%) | 13 (38.2%) | |||

| Periventricular | Yes | 31 (48.4%) | 33 (51.6%) | NS | |

| No | 5 (71.4%) | 2 (28.6%) | |||

| Pericallosal | Yes | 26 (49.1%) | 27 (50.9%) | NS | |

| No | 10 (55.6%) | 8 (44.4%) | |||

| Subarachnoid | Yes | 4 (33.3%) | 8 (66.6%) | NS | |

| No | 32 (54.2% | 27 (45.8%) | |||

| Subependymal | Yes | 7 (58.3%) | 5 (41.7%) | NS | |

| No | 29 (49.2%) | 30 (50.8%) | |||

| “butterfly”d | Yes | 15 (42.9%) | 20 (57.1%) | NS | |

| No | 21 (58.3%) | 15 (41.7%) | |||

| Tumor localization | Lobar only | 21 (58.3%) | 15 (41.7%) | NS | |

| Any posterior fossa disease | 2 (40.0%) | 3 (60.0%) | |||

| Other | 13 (43.3%) | 17 (56.7%) | |||

| Eloquence | Overall | ≥ 1 eloquent lesion | 23 (56.1%) | 18 (43.9%) | NS |

| ≥ 1 near-eloquent, but no eloquent lesion | 6 (28.6%) | 15 (71.4%) | |||

| No (near) eloquent lesion(s) | 7 (77.7%) | 2 (22.2%) | |||

| ≥ 1 any motor eloquent lesion | Yes | 10 (41.7%) | 14 (58.3%) | NS | |

| No | 26 (55.3%) | 21 (44.7%) | |||

| ≥ 1 speech eloquent lesion | Yes | 7 (58.3%) | 5 (41.7%) | NS | |

| No | 29 (49.2%) | 30 (50.8%) | |||

| ≥ 1 visual pathways eloquent lesion | Yes | 13 (50.0%) | 13 (50.0%) | NS | |

| No | 23 (51.1%) | 22 (48.9%) | |||

| Tumorload | Lesion no. | ≤ 2 (median) | 29 (64.4%) | 16 (35.6%) | 0.002 |

| > 2 | 7 (26.9%) | 19 (73.1%) | |||

| Preoperative | > 17.3 ml (median) | 22 (62.9%) | 13 (37.1%) | 0.043 | |

| ≤ 17.3 ml | 14 (38.9%) | 22 (61.1%) | |||

| Postoperative | > 4.5 ml (median) | 7 (20.0%) | 28 (80.0%) | < 0.001 | |

| ≤ 4.5 ml | 29 (80.6%) | 7 (20.0%) | |||

| Treatment data | |||||

| Adjuvant therapy | Radiotherapy | Completed | 24 (63.2%) | 14 (36.8%) | 0.028 |

| Incomplete | 4 (40.0%) | 6 (60.0%) | |||

| None | 8 (34.8%) | 15 (65.2%) | |||

| Chemotherapy | Yes | 26 (65.0%) | 14 (35.0%) | 0.006 | |

| No | 10 (32.3%) | 21 (67.7%) | |||

| Radiochemotherapy | RT completed, TMZ or TMZ/CCNU | 21 (63.6%) | 12 (36.4%) | 0.022 | |

| RT incomplete or monotherapy | 8 (50.0%) | 8 (50.0%) | |||

| None | 7 (31.8%) | 15 (68.2%) |

aN = 61

bP = 0.075

cP = 0.074

d“butterfly” = bihemspheric contrast enhancing pericallosal disease

KPI Karnofsky performance index, NANO eurologic assessment in neuro-oncology, MGMT O(6)-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase, STR subtotal resection, RT Radiotherapy, TMZ Temozolomide, CCNU Lomustine

Treatment related variables had a strong survival impact (Table 3). Median estimated survival was 10.8 months in patients who completed radiotherapy and had chemotherapy, but only 1.5 months in cases with no adjuvant therapy. There was a statistically significant correlation between extent of resection and survival (Fig. 2). Median survival was 13.6 (95% CI: 11.1–16.1) months after a complete resection (of the contrast enhancing tumor), 6.4 (95% CI: 2.8–10.0) months after a subtotal resection (STR), and only 3.4 (95% CI: 1.05.7) months after a biopsy (P = 0.043). Median survival was 12.0 (95% CI: 7.2–16.8) months following a resection and radiochemotherapy. Finally, multicentric tumor growth was associated with a significantly worsened survival.

Table 3.

Prognostic significance of demographics, radiological and treatment data

| Characteristics | N | mOS | 95% CI | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | Age | ≤ 69 yrs. | 37 | 9.1 | 6.0–12.2 | 0.008 |

| > 69 yrs. (median) | 34 | 3.1 | 0.5–5.7 | |||

| Sex | Female | 35 | 6.6 | 2.9–7.5 | NS | |

| Male | 36 | 5.2 | 3.1–10.0 | |||

| Preoperative KPI | 80–100 | 48 | 8.9 | 5.6–12.2 | NSb | |

| < 80 | 23 | 3.1 | 1.3–4.8 | |||

| Postoperative KPI | 80–100 | 48 | 8.9 | 5.6–12.2 | NSc | |

| < 80% | 23 | 3.1 | 1.2–4.9 | |||

| Preoperative NANO score | 0–2 | 35 | 6.4 | 4.1–8.7 | NS | |

| > 2 | 36 | 5.8 | 0.2–11.4 | |||

| Postoperative NANO score | 0–2 | 36 | 7.0 | 5.2–8.9 | NS | |

| > 2 | 35 | 4.8 | 3.3–6.3 | |||

| Preoperative seizures | Yes | 25 | 7.0 | 2.0–12.0 | NS | |

| No | 46 | 5.8 | 4.1–7.6 | |||

| MGMT promoter hypermethylationa | Positive | 27 | 4.2 | 1.8–6.7 | NS | |

| Negative | 34 | 7.0 | 4.8–9.3 | |||

| Radiological data | ||||||

| Growth pattern | Multicentric | Yes | 26 | 3.2 | 5.7–12.1 | 0.019 |

| No | 45 | 8.9 | 0.5–5.9 | |||

| Multifocal | Yes | 54 | 6.6 | 3.0–5.8 | NS | |

| No | 17 | 4.4 | 4.8–8.4 | |||

| Spread | Bilateral | Yes | 37 | 6.6 | 2.7–10.5 | NS |

| No | 34 | 5.9 | 3.7–8.1 | |||

| Periventricular | Yes | 64 | 5.2 | 2.9–7.5 | NS | |

| No | 7 | 9.3 | 3.5–15.0 | |||

| Pericallosal | Yes | 53 | 5.8 | 3.2–8.5 | NS | |

| No | 18 | 7.0 | 0–14.2 | |||

| Subarachnoid | Yes | 12 | 6.7 | 0.9–12.6 | NS | |

| No | 59 | 5.9 | 3.6–8.2 | |||

| Subependymal | Yes | 12 | 2.4 | 0–6.1 | NS | |

| No | 59 | 7.0 | 3.7–10.3 | |||

| „butterfly“e | Yes | 35 | 7.4 | 2.7–12.1 | NS | |

| No | 36 | 5.9 | 4.0–7.7 | |||

| Tumor localization | Lobar only | 36 | 8.9 | 5.4–12.4 | NS | |

| Any posterior fossa disease | 5 | 1.5 | 0.7–2.4 | |||

| Other | 30 | 5.0 | 3.9–6.1 | |||

| Eloquence | Overall | > 1 eloquent lesion | 41 | 5.9 | 3.6–8.1 | NS |

| > 1 near-eloquent, but no eloquent lesion | 21 | 7.4 | 0–15.9 | |||

| No (near) eloquent lesion(s) | 9 | 6.4 | 4.8–7.9 | |||

| Motor eloquence | Yes | 24 | 4.8 | 4.5–10.3 | NS | |

| No | 47 | 7.4 | 3.3–6.2 | |||

| Speech eloquence | Yes | 12 | 4.1 | 1.9–6.3 | 0.022 | |

| No | 59 | 7.0 | 3.9–10.1 | |||

| Visual pathways eloquence | Yes | 26 | 5.2 | 2.2–8.2 | NS | |

| No | 45 | 6.6 | 3.7–9.4 | |||

| Tumorload | Lesion no | ≤ 2 (median) | 45 | 8.9 | 4.4–13.4 | NSd |

| > 2 | 26 | 3.1 | 1.1–5.0 | |||

| Preoperative | > 17.3 ml (median) | 35 | 4.2 | 2.9–5.6 | NS | |

| ≤ 17.3 ml | 36 | 8.9 | 6.0–11.8 | |||

| Postoperative | > 4.5 ml (median) | 35 | 3.4 | 0.7–6.1 | NS | |

| ≤ 4.5 ml (median) | 36 | 7.0 | 3.3–10.8 | |||

| Treatment data | ||||||

| Operative treatment | Type of operation | Resection | 36 | 10.1 | 5.1–15.1 | 0.015 |

| Biopsy | 35 | 3.4 | 1.0–5.7 | |||

| Extent of resection | Complete resection (postop. contrast enhancing tumor volume < 0.1 ml) | 13 | 13.6 | 11.1–16.1 | 0.043 | |

| STR | 23 | 6.4 | 2.8–10.0 | |||

| Biopsy | 35 | 3.4 | 1.0–5.7 | |||

| Adjuvant therapy | Radiotherapy (RT) | Completed | 39 | 10.2 | 7.6–12.6 | < 0.001 |

| Incomplete | 9 | 5.9 | 2.2–9.5 | |||

| None | 23 | 1.5 | 1.1–2.0 | |||

| Chemotherapy (CT) | Yes | 40 | 10.5 | 8.3–12.7 | < 0.001 | |

| No | 31 | 1.9 | 1.5–2.4 | |||

| Radiochemotherapy | RT completed, TMZ or TMZ/CCNU | 33 | 10.8 | 7.9–13.7 | < 0.001 | |

| RT incomplete or monotherapy | 16 | 5.9 | 0.9–4.0 | |||

| None | 22 | 1.5 | 0.2–1.0 |

aN = 61

bP = 0.066

cP = 0.067

dP = 0.065

e“butterfly” = bihemspheric contrast enhancing pericallosal disease

mOS median overall survival (months); 95%CI – 95% confidence interval, MGMT O(6)-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase, KPI Karnofsky performance index, NANO neurologic assessment in neuro-oncology, STR subtotal resection, RT Radiotherapy, TMZ Temozolomide, CCNU Lomustine

Fig. 2.

Prognostic impact of the extent of resection on overall survival (Kaplan-Meier analysis), STR subtotal resection, Complete res. – postop. contrast enhancing tumor volume < 0.1 ml

Four cases incurred CTCAE grades 3–5 new or worsened postoperative neurological deficits persisiting ≥ 30 days (5.6%; resection: N = 3, biopsy: N = 1), and 5 cases with CTCAE grades 3–5 local/surgical complications (7.0%; resection: N = 3, biopsy: N = 2; including one brain abscess 3 months after surgery for temporal lobe glioblastoma and three hemorrhages). One case with a VP shunt implanted for normal pressure hydrocephalus required an operative shunt revision for shunt malfunction 13 days after a stereotactic biopsy. 30 days mortality was 4/71 (5.6%) with one patient dying from gastrointestinal bleeding 11 days following surgery, two from progressive tumors, and one from unknown causes. Median preoperative KPI and NANO scores were 80 (25–75% IQR: 20–100) and 3 (25–75% IQR: 1–4); the respective postoperative figures were 80 (25–75% IQR: 20–100) and 2 (25–75% IQR: 1–4). Only two cases (2.8%) had a postoperative > 20 drop of their KPI score, and all neurologically intact patients retained their preoperative NANO score of 0.

A multivariate Cox regression analysis (Supplementary Table 1) revealed multicentric growth, biopsy vs. resective surgery, no chemotherapy and no or incomplete radiotherapy as independent negative prognostic predictors with the largest hazard ratios attributed to the adjuvant therapy variables.

Surgical treatment bias

We extensively compared the resection and biopsy patients with respect to demographic factors as well as tumor characteristics (Table 2). Neither age, sex, MGMT status nor preoperative KPI or NANO scores varied significantly between biopsy and resection cases. There was a statistical trend for an association between cytoreductive surgery and a worse preoperative neurological condition as assessed by the NANO score. Cases with three or more lesions had significantly more often bioptic than resective surgery. However, the volumetric tumorload was significantly higher in resective vs. biopsy cases. There was a statistical trend in favor of performing a biopsy in patients with bihemispheral tumor growth.

Discussion

The optimal management of patients with mGBM is controversial [1–6]. Our data suggest that resective surgery in cases with mGBM might be beneficial, and that much of this effect relates to the impact of tumor debulking and reduction of mass effect which allows the patient to undergo adjuvant therapies. However, we also found some evidence that surgical cytoreduction per se might prolong patient survival.

Patient survival following the diagnosis of a mGBM is generally poor. In the literature overall survival varies between 3 and 9 months [2–9]. Median overall survival in the present series was only 6.4 months. However, there was significant interindividual variation. Median survival after a complete resection of the contrast enhancing tumor (which was achieved in 13 [18.3%] cases) was 13.6 months. While the patients’ prognosis was found to correlate significantly also with traditional prognostic factors such as age and KPI, treatment variables appeared to play an even more prominent role. Based on the hazard ratios in the multivariate analysis completion of postoperative adjuvant radiotherapy and chemotherapy were the strongest positive predictors of patient survival. Interestingly, there was a strong correlation between more and completed adjuvant therapy with resective rather than bioptic surgery. This may indicate that successful adjuvant therapy often requires upfront debulking surgery because patients with a large tumorload will not tolerate these treatments because of the mass effect of the tumor [3, 10].

The risk of incurring a neurological deficit and/or complications in general is of course a major concern in cases with limited survival which in addition need active postoperative oncological therapy in order to realize the benefits of their surgery. Surgical management of our patients carried a quite significant but probably still acceptable complication rate. We observed 5.6% new or worsened CTCAE grade 3–5 neurological deficits ≥ 30 days and 7.0% CTCAE grade 3–5 local/surgical complications. Figures were larger for resective than bioptic cases, but the overall small numbers precluded any statistical significance. Still, the well-known lower complication rate of (stereotactic) biopsies when compared to open microsurgery is a relevant issue when dealing with a patient population with a very limited survival prognosis [21]. Nevertheless, at least in this series, the use of resective surgery for mGBM did not result in a relevant number of patients incurring deficits and complications precluding further therapy and thereby shortening survival.

Interestingly, our data and especially the multivariate analysis also suggest that surgical cytoreduction as such may have a significant impact on patient survival. These findings are well in line with the results detailed in the recent studies by Di et al. and Friso et al. The existence of a correlation between degree of resection and survival also in mGBM should not come as a complete surprise. There is a considerable database suggesting that this relationship in (unifocal) GBM cannot be appropriately described by the all-or nothing-paradigm [11]. The extent of resection cut-off for a survival benefit derived from surgery may be in the range of 80–90% [14, 16, 17]. Interestingly (and quite fittingly), the mean extent of resection in cases from this study who had open debulking surgery was 88.9 ± 19.8%. In other words, at least in the present cohort a substantial number of cases had a resection of their contrast-enhancing tumor to a degree believed to be beneficial if performed for unifocal disease. If unifocal and mGBM respond similarly to surgical cytoreduction patients with mGBM could potentially be included in the same (surgical) clinical trials as cases with unifocal disease.

This line of reasoning does not take into account the issue of non-contrast enhancing glioblastoma tissues [15]. Against this background our finding that the presence of multicentric growth predicted a worse survival outcome might be of importance. Multicentric growth is defined by the absence of FLAIR/T2 hypertintense tissue bridges connecting contrast enhancing glioblastoma manifestations and might therefore somewhat resemble cancer metastasis. Multifocal growth on the other hand might be caused by infiltration and (mass cell) migration which will result in a larger and extensive but essentially still conceptually “unifocal” non contrast enhancing tumor. Resecting several contrast-enhancing foci in such cases can be conceptualized as multiple partial resections. Other groups have also compared different growth patterns and have not reported similar results [2–5, 8].

Finally, one of the key arguments against the existence of a causative relationship between degree of resection and survival is the presumed presence of surgical treatment bias, i.e. the notion that cases with an inherently better prognosis receive more aggressive therapy [2, 18, 28, 29]. We did not obtain evidence in favor of such bias with respect to established prognostic factors. We compared our resection and biopsy cohorts quite carefully. The patient subsets did not differ statistically significantly with respect to age, sex, functional (KPI) and neurological (NANO score) status, or preoperative seizure incidence. The rate of tumors with MGMT promoter hypermethylation was also quite similar. The cohorts only differed with respect to parameters describing tumor growth and spread. Tumors with two discrete lesions were much more likely to undergo resective surgery than a biopsy procedure, while higher volumetric tumorload was associated with a tumor resection. The general concept of maximal safe surgery of course precluded resecting some eloquent lesions and if possible resulted in choosing non-eloquent lesions as the biopsy target. This clearly constitutes the major treatment selection bias in this series.

Limitations

Our study has of course significant shortcomings. The overall number of patients investigated was limited. A relatively high proportion of our cases had no or did not complete adjuvant radio- and chemotherapy. Data were retrieved only retrospectively. While surgical treatment followed an institutional protocol, this was not the case with the adjuvant therapies. Many patients were followed at outside institutions.

Conclusions

We provide data to show that resective surgery somewhat counterintuitively may carry a survival benefit in cases with presumed mGBM glioblastoma. This benefit seems to relate prominently to an increased number of patients being able to tolerate effective adjuvant therapies after tumor resections, i.e. our results support the concept of operating in order to gain time and create space for chemo- and radiotherapy. In addition, cytoreductive surgery may have a survival impact per se. Surgical decision making in patients with mGBM should therefore focus on a proper balance between surgical risks, treating mass effect and—if possible—oncologically effective cytoreduction. This is actually very similar to current strategies for unifocal glioblastoma, i.e. also cases with mGBM should be considered for a tumor resection as long as an extensive and safe removal of contrast enhancing tissues is reasonably possible and patients are deemed to be able to undergo effective adjuvant chemo- and radiotherapy.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary material 1 (DOCX 188.1 kb)

Abbreviations

- ALA

5-aminolevulinic acid

- CCNU

lomustine

- CeTeG

lomustine-temozolamide radiochemotherapy combination

- CI

Confidence interval

- CTCAE

Common terminology criteria for adverse events

- FLAIR

Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery

- GBM

Glioblastoma

- IDH1

Isocitrate dehydrogenase 1

- IQR

Interquartile range

- KPI

Karnofsky performance Index

- MGMT

O(6)-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase

- MR

Magnetic resonance

- mGBM

Multifocal/multicentric glioblastoma

- NANO

Neurologic assessment in neuro-oncology

- RANO

Response assessment in neuro-oncology

- STR

Subtotal resection

- SD

Standard deviation

- TMZ

Temozolamide

- VP

Ventriculoperitoneal

Author contributions

DD, AG and MS developed the study concept. Clinical data were collected by DD, AG and DB. Neuroradiology and neuropathology data were contributed by BB and RC, respectively. Data analysis was performed by DD and MS. Figures and Tables were prepared by DD and MS. All authors helped with the preparation of the paper, and read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the responsible institutional review board for human research and ethics committee (Ethikkommission der Ärztekammer Westfalen-Lippe und der Westfälischen Wilhelms-Universität Münster, Germany, Az 2018-143-f-S).

Consent to participate

The responsible institutional research committee and local law do not require written informed consent for this study.

Consent to publish

All authors agreed to the publication of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Wen PY, Weller M, Lee EQ, Alexander BM, Barnholtz-Sloan JS, Barthel FP, Batchelor TT, Bindra RS, Chang SM, Chiocca EA, Cloughesy TF, DeGroot JF, Galanis E, Gilbert MR, Hegi ME, Horbinski C, Huang RY, Lassman AB, Le Rhun E, Lim M, Mehta MP, Mellinghoff IK, Minniti G, Nathanson D, Platten M, Preusser M, Roth P, Sanson M, Schiff D, Short SC, Taphoorn MJB, Tonn JC, Tsang J, Verhaak RGW, von Deimling A, Wick W, Zadeh G, Reardon DA, Aldape KD, van den Bent MJ. Glioblastoma in adults: a society for neuro-oncology (SNO) and european society of neuro-oncology (EANO) consensus review on current management and future directions. Neuro Oncol. 2020;22(8):1073–1113. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noaa106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Di L, Heath RN, Shah AH, Sanjurjo AD, Eichberg DG, Luther EM, de la Fuente MI, Komotar RJ, Ivan ME. Resection versus biopsy in the treatment of multifocal glioblastoma: a weighted survival analysis. J Neurooncol. 2020;148(1):155–164. doi: 10.1007/s11060-020-03508-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Friso F, Rucci P, Rosetti V, Carretta A, Bortolotti C, Ramponi V, Martinoni M, Palandri G, Zoli M, Badaloni F, Franceschi E, Asioli S, Fabbri VP, Rustici A, Foschini MP, Brandes AA, Mazzatenta D, Sturiale C, Conti A. Is there a role for surgical resection of multifocal glioblastoma? a retrospective analysis of 100 patients. Neurosurgery. 2021;89(6):1042–1051. doi: 10.1093/neuros/nyab345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haque W, Thong Y, Verma V, Rostomily R, Brian Butler E, Teh BS. Patterns of management and outcomes of unifocal versus multifocal glioblastoma. J Clin Neurosci. 2020;74:155–159. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2020.01.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baro V, Cerretti G, Todoverto M, Della Puppa A, Chioffi F, Volpin F, Causin F, Busato F, Fiduccia P, Landi A, d’Avella D, Zagonel V, Denaro L, Lombardi G. Newly diagnosed multifocal GBM: a monocentric experience and literature review. Curr Oncol. 2022;29(5):3472–3488. doi: 10.3390/curroncol29050280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hassaneen W, Levine NB, Suki D, Salaskar AL, de Moura LA, McCutcheon IE, Prabhu SS, Lang FF, DeMonte F, Rao G, Weinberg JS, Wildrick DM, Aldape KD, Sawaya R. Multiple craniotomies in the management of multifocal and multicentric glioblastoma clinical article. J Neurosurg. 2011;114(3):576–584. doi: 10.3171/2010.6.JNS091326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parsa AT, Wachhorst S, Lamborn KR, Prados MD, McDermott MW, Berger MS, Chang SM. Prognostic significance of intracranial dissemination of glioblastoma multiforme in adults. J Neurosurg. 2005;102(4):622–628. doi: 10.3171/jns.2005.102.4.0622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thomas RP, Xu LW, Lober RM, Li G, Nagpal S. The incidence and significance of multiple lesions in glioblastoma. J Neurooncol. 2013;112(1):91–97. doi: 10.1007/s11060-012-1030-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kasper J, Hilbert N, Wende T, Fehrenbach MK, Wilhelmy F, Jähne K, Frydrychowicz C, Hamerla G, Meixensberger J, Arlt F. On the prognosis of multifocal glioblastoma: an evaluation incorporating volumetric MRI. Curr Oncol. 2021;28(2):1437–1446. doi: 10.3390/curroncol28020136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lasocki A, Gaillard F, Tacey M, Drummond K, Stuckey S. Multifocal and multicentric glioblastoma: improved characterisation with FLAIR imaging and prognostic implications. J Clin Neurosci. 2016;31:92–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2016.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patil CG, Yi A, Elramsisy A, Hu J, Mukherjee D, Irvin DK, Yu JS, Bannykh SI, Black KL, Nuño M. Prognosis of patients with multifocal glioblastoma: a case-control study. J Neurosurg. 2012;117(4):705–711. doi: 10.3171/2012.7.JNS12147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lacroix M, Abi-Said D, Fourney DR, Gokaslan ZL, Shi W, DeMonte F, Lang FF, McCutcheon IE, Hassenbusch SJ, Holland E, Hess K, Michael C, Miller D, Sawaya R. A multivariate analysis of 416 patients with glioblastoma multiforme: prognosis, extent of resection, and survival. J Neurosurg. 2001;95(2):190–198. doi: 10.3171/jns.2001.95.2.0190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stummer W, Reulen HJ, Meinel T, Pichlmeier U, Schumacher W, Tonn JC, Rohde V, Oppel F, Turowski B, Woiciechowsky C, Franz K, Pietsch T, ALA-Glioma Study Group Extent of resection and survival in glioblastoma multiforme: identification of and adjustment for bias. Neurosurgery. 2008;62(3):564–576. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000317304.31579.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chaichana KL, Jusue-Torres I, Navarro-Ramirez R, Raza SM, Pascual-Gallego M, Ibrahim A, Hernandez-Hermann M, Gomez L, Ye X, Weingart JD, Olivi A, Blakeley J, Gallia GL, Lim M, Brem H, Quinones-Hinojosa A. Establishing percent resection and residual volume thresholds affecting survival and recurrence for patients with newly diagnosed intracranial glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol. 2014;16(1):113–122. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/not137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haddad AF, Young JS, Morshed RA, Berger MS. FLAIRectomy: resecting beyond the contrast margin for glioblastoma. Brain Sci. 2022;12(5):544. doi: 10.3390/brainsci12050544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sanai N, Polley MY, McDermott MW, Parsa AT, Berger MS. An extent of resection threshold for newly diagnosed glioblastomas. J Neurosurg. 2011;115(1):3–8. doi: 10.3171/2011.2.jns10998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kreth FW, Thon N, Simon M, Westphal M, Schackert G, Nikkhah G, Hentschel B, Reifenberger G, Pietsch T, Weller M, Tonn JC. German glioma network. gross total but not incomplete resection of glioblastoma prolongs survival in the era of radiochemotherapy. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(12):3117–3123. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thon N, Thorsteinsdottir J, Eigenbrod S, Schüller U, Lutz J, Kreth S, Belka C, Tonn J-C, Niyazi M, Kreth FW. Outcome in unresectable glioblastoma:MGMT promoter methylation makes the difference. J Neurol. 2017;264(2):350–358. doi: 10.1007/s00415-016-8355-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nayak L, DeAngelis LM, Brandes AA, Peereboom DM, Galanis E, Lin NU, Soffietti R, Macdonald DR, Chamberlain M, Perry J, Jaeckle K, Mehta M, Stupp R, Muzikansky A, Pentsova E, Cloughesy T, Iwamoto FM, Tonn JC, Vogelbaum MA, Wen PY, van den Bent MJ, Reardon DA. The neurologic assessment in neuro-oncology (NANO) scale: a tool to assess neurologic function for integration into the response assessment in neuro-oncology (RANO) criteria. Neuro Oncol. 2017;19(5):625–635. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nox029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Theodosopoulos PV, Ringer AJ, McPherson CM, Warnick RE, Kuntz C, 4th, Zuccarello M, Tew JM., Jr Measuring surgical outcomes in neurosurgery: implementation, analysis, and auditing a prospective series of more than 5000 procedures. J Neurosurg. 2012;117(5):947–954. doi: 10.3171/2012.7.JNS111622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ersoy TF, Mokhtari N, Brainman D, Berger B, Salay A, Schütt P, Weissinger F, Grote A, Simon M. Surgical treatment of cerebellar metastases: survival benefits, complications and timing issues. Cancers. 2021;13(21):5263. doi: 10.3390/cancers13215263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yasin H, Hoff HJ, Blümcke I, Simon M. Experience with 102 frameless stereotactic biopsies using the neuromate robotic device. World Neurosurg. 2019;123:e450–e456. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2018.11.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leao DJ, Craig PG, Godoy LF, Leite CC, Policeni B. Response assessment in neuro-oncology criteria for gliomas: practical approach using conventional and advanced techniques. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2020;41(1):10–20. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A6358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sawaya R, Hammoud M, Schoppa D, Hess KR, Wu SZ, Shi WM, Wildrick DM. Neurosurgical outcomes in a modern series of 400 craniotomies for treatment of parenchymal tumors. Neurosurgery. 1998;42(5):1044–1055. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199805000-00054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chang EF, Smith JS, Chang SM, Lamborn KR, Prados MD, Butowski N, Barbaro NM, Parsa AT, Berger MS, McDermott MM. Preoperative prognostic classification system for hemispheric low-grade gliomas in adults. J Neurosurg. 2008;109(5):817–824. doi: 10.3171/JNS/2008/109/11/0817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Herrlinger U, Tzaridis T, Mack F, Steinbach JP, Schlegel U, Sabel M, Hau P, Kortmann RD, Krex D, Grauer O, Goldbrunner R, Schnell O, Bähr O, Uhl M, Seidel C, Tabatabai G, Kowalski T, Ringel F, Schmidt-Graf F, Suchorska B, Brehmer S, Weyerbrock A, Renovanz M, Bullinger L, Galldiks N, Vajkoczy P, Misch M, Vatter H, Stuplich M, Schäfer N, Kebir S, Weller J, Schaub C, Stummer W, Tonn JC, Simon M, Keil VC, Nelles M, Urbach H, Coenen M, Wick W, Weller M, Fimmers R, Schmid M, Hattingen E, Pietsch T, Coch C, Glas M. Neurooncology working group of the german cancer society. lomustine-temozolomide combination therapy versus standard temozolomide therapy in patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma with methylated MGMT promoter (CeTeG/NOA-09): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2019;393(10172):678–688. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31791-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, Weller M, Fisher B, Taphoorn MJ, Belanger K, Brandes AA, Marosi C, Bogdahn U, Curschmann J, Janzer RC, Ludwin SK, Gorlia T, Allgeier A, Lacombe D, Cairncross JG, Eisenhauer E, Mirimanoff RO. European organisation for research and treatment of cancer brain tumor and radiotherapy groups; national cancer institute of Canada Clinical trials group radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(10):987–996. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Giannopoulos S, Kyritsis AP. Diagnosis and management of multifocal gliomas. Oncology. 2010;79(3–4):306–312. doi: 10.1159/000323492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Winger MJ, Macdonald DR, Schold SC, Jr, Cairncross JG. Selection bias in clinical trials of anaplastic glioma. Ann Neurol. 1989;26(4):531–534. doi: 10.1002/ana.410260406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material 1 (DOCX 188.1 kb)

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.