Abstract

Since 2010, medical toxicology physicians from the American College of Medical Toxicology (ACMT) Toxicology Investigators Consortium (ToxIC) have provided reports on their in-hospital and clinic patient consultations to a national case registry, known as the ToxIC Core Registry. De-identified patient data entered into the registry includes patient demographics, reason for medical toxicology evaluation, exposure agents, clinical signs and symptoms, treatments and antidotes administered, and mortality. This thirteenth annual report provides data from 7206 patients entered into the Core Registry in 2022 by 35 participating sites comprising 52 distinct healthcare facilities, bringing the total case count to 94,939. Opioid analgesics were the most commonly reported exposure agent class (15.9%), followed by ethanol (14.9%), non-opioid analgesic (12.8%), and antidepressants (8.0%). Opioids were the leading agent of exposure for the first time in 2022 since the Core Registry started. There were 118 fatalities (case fatality rate of 1.6%). Additional descriptive analyses in this annual report were conducted to describe the location of the patient during hospitalization, telemedicine consultations, and addiction medicine treatments.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s13181-023-00962-2.

Keywords: Poisoning, Overdose, Surveillance, Epidemiology, Medical Toxicology

Introduction

The Toxicology Investigators Consortium (ToxIC) Core Registry was established by the American College of Medical Toxicology (ACMT) in 2010. ToxIC’s initial project was a case registry of patients seen by medical toxicology physicians through consultations conducted at the bedside and in the clinic [1–12]. Known as the ToxIC Core Registry, patient accrual into this registry has been ongoing since 2010 [1, 2]. The main objectives of the ToxIC Core Registry are to describe toxicological exposures seen by medical toxicology physicians and to provide a data source for research in medical toxicology. Each year, an annual report summarizing this data has been published. This thirteenth annual report provides data from 7206 patients entered into the Core Registry in 2022 by 35 participating sites comprising 52 distinct healthcare facilities.

Within the Core Registry, more detailed data on specific patient populations are gathered through sub-registries and/or focused data collection. The North American Snakebite Registry (NASBR) is one of the largest sub-registries and includes patients with snakebites who have been treated by medical toxicology physicians (Principal Investigator (PI): Anne-Michelle Ruha, MD; funded by BTG Pharmaceuticals, a SERB company). NASBR has accrued more than 1,800 cases since 2013, with detailed data on circumstances of snakebite, clinical manifestations, and response to treatment. NASBR investigators published research in 2022 on late hemotoxicity among snakebite patients treated with crotalidae immune F(ab')2 (equine) antivenom and crotalidae immune polyvalent Fab (ovine) antivenom [13].

The Novel Opioid and Stimulant Exposures (NOSE) focused data collection (PI: Meghan Spyres, MD; funded by SAMHSA 1H79TI085588) provides comprehensive case narratives on patients evaluated by medical toxicology physicians who may have been exposed to a novel agent or had an unusual presentation to a common agent. Coordinated by the American Academy of Addiction Psychiatry (AAAP), quarterly reports on findings are disseminated through the Opioid Response Network (ORN). ToxIC NOSE briefs in 2022 included topics on xylazine, wound botulism, and illicit fentanyl.

Two additional ongoing sub-registries include the Natural Toxins Registry: Mushrooms and Plants, and the Extracorporeal Therapies Registry.

Other ToxIC Multicenter Projects

Since 2020 ToxIC has initiated several multicenter projects separate from the ToxIC Core Registry and Sub-registries. These individual projects leverage the ToxIC infrastructure with medical toxicology physicians serving as PIs at each site.

The Fentalog Study is an ongoing, 5-year prospective cohort study (PI: Alex Manini; NIH NIDA 5R01DA048009 and CDC Supplement R01DA048009-03S1). This study, titled “Predicting Medical Consequences of Novel Fentanyl Analog Overdose Using the Toxicology Investigators Consortium (ToxIC)”, enrolls patients who have a suspected opioid overdose who present to the emergency department at one of 10 participating medical centers. Patient demographics, comorbidities, clinical treatments, and outcome data are collected through chart reviews. Waste blood samples collected for routine laboratories are obtained and sent to the Center for Forensic Science Research and Education (CFSRE) for qualitative toxicology analyses to determine the presence of over 1,000 novel psychoactive substances, illicit substances (e.g., fentanyl, fentanyl analogs, and illicit benzodiazepines), and adulterants (e.g., xylazine) [14]. From 2020–2022, 921 cases were enrolled. The first reported human exposure to N-piperidinyl etonitazene found in 3 patients from one study site was published in 2022 [15].

In 2020, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) ACMT COVID-19 ToxIC (FACT) Pharmacovigilance Project (FDA #75F40119D10031) was initiated in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The project implemented a real-time national toxico-surveillance reporting program at 15 ToxIC sites that identified adverse events associated with COVID-19 therapeutics. By the end of 2022, the project had expanded to 17 sites and 1263 cases with suspected adverse events had been reported, including adverse events to ivermectin [16].

ToxIC Publications and Presentations

Nine peer-reviewed ToxIC publications were released in 2022. In addition, 25 ToxIC abstracts were presented at the North American Congress of Clinical Toxicology (NACCT) meeting, ACMT Annual Scientific Meeting (ASM), and European Association of Poison Centers and Clinical Toxicologists (EAPCCT) meeting. These publications and abstracts are detailed on the ToxIC website: www.toxicregistry.org.

Changes to the ToxIC Core Registry in 2022

As the ToxIC Core Registry continues to grow, changes are made each year to augment data collection. In 2022, new sections were added on past medical history, past psychiatric history, and current and past misuse of pharmaceutical and non-pharmaceutical agents. A new question about the locations of the patient during hospitalization (e.g.,critical care unit, hospital floor, emergency department only) was added as a representation of hospital resource utilization and exposure severity.

Annual Report Objectives

The objective of this annual report is to describe the cases entered into the ToxIC Core Registry in 2022. In addition to a summary of the Core Registry data, descriptive analyses were conducted to describe the location of the patient during hospitalization, telemedicine consultations, and addiction medicine treatments.

Methods

Medical toxicology physicians at participating healthcare sites within the ToxIC Core Registry enter deidentified patient information from medical toxicology consultations and evaluations at the bedside, in the clinic, and via telemedicine. Study data were collected and managed using REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) electronic data capture tools hosted at Vanderbilt University [17, 18]. REDCap is a secure, web-based software platform designed to support data capture for research studies, providing 1) an intuitive interface for validated data capture; 2) audit trails for tracking data manipulation and export procedures; 3) automated export procedures for seamless data downloads to common statistical packages; and 4) procedures for data integration and interoperability with external sources.

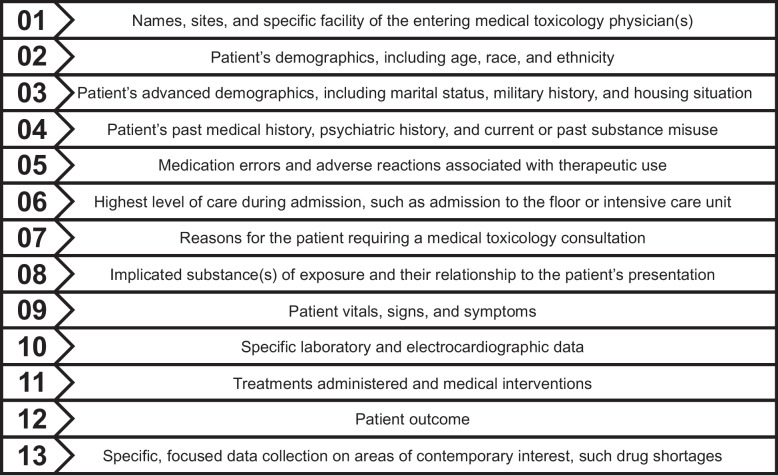

The data gathered in the Core Registry by medical toxicology physicians is a culmination of information from the patient’s electronic medical record and their first-hand evaluation of the patient during their consultation utilizing available evidence (e.g., patient self-report or family report, presence of the product of exposure, clinical presentation, physical examination, ancillary data, and/or laboratory testing results). Figure 1 contains a brief overview of the Core Registry data collection elements.

Fig. 1.

Core Registry data collection elements.

All cases entered into the Core Registry and associated sub-registries/focused data collections are reviewed for quality assurance (QA) by the ToxIC staff. Any inconsistent or incomplete entries are queried back to the entering medical toxicologist for correction or clarification. ToxIC leadership and staff communicate with all sites to review patient accrual, barriers to data entry, quality assurance efforts, and ongoing project opportunities. Additional information regarding ToxIC can be found at www.toxicregistry.org.

Each ToxIC project has been reviewed by the WCG Institutional Review Board (WCG IRB) and operates in accordance with the approval of the participating site IRBs. All data collected by ToxIC is deidentified and compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA).

Statistical Analysis

Data from January 1, 2022-December 31, 2022 were extracted from REDCap and exported into Microsoft Excel. Descriptive statistics were calculated to obtain relative and absolute frequencies for demographics, advanced demographics, past history, medical toxicology consultation location, exposure and treatment information, and mortality among cases in the ToxIC Core Registry. Small cell sizes for specific agent exposures were collapsed into “miscellaneous” categories which are detailed in footnotes for relevant tables.

Results

In 2022, there were a total of 7206 cases of toxicologic exposures reported to the ToxIC Core Registry from 52 healthcare facilities at 35 sites. Individual facilities contributing cases in 2022 are listed in Table 1. One new site, Einstein Medical Center Philadelphia, initiated data collection in 2022.

Table 1.

Participating institutions providing cases to ToxIC in 2022.

| State or Country | City | Hospitals |

|---|---|---|

| Arizona | Phoenix | Banner—University Medical Center Phoenix |

| Phoenix Children's Hospital | ||

| Alabama | Birmingham | University of Alabama at Birmingham Hospital |

| Arkansas | Little Rock | Arkansas Children's Hospital |

| California | Loma Linda | Loma Linda University Medical Center |

| Los Angeles | University of California Los Angeles—Olive View | |

| University of California Los Angeles—Ronald Reagan | ||

| University of California Los Angeles—Santa Monica | ||

| Sacramento | University of California Davis Medical Center | |

| Colorado | Denver | Colorado Children’s Hospital |

| Denver Health Medical Center | ||

| Porter and Littleton Hospital | ||

| Swedish Hospital | ||

| University of Colorado Hospital | ||

| Connecticut | Hartford | Hartford Hospital |

| Florida | Jacksonville | University of Florida Health Jacksonville |

| Georgia | Atlanta | Grady Memorial Hospital |

| Indiana | Indianapolis | Indiana University—Eskenazi Hospital |

| Indiana University—Indiana University Hospital | ||

| Indiana University—Methodist Hospital-Indianapolis | ||

| Indiana University—Riley Hospital for Children | ||

| Kansas | Kansas City | University of Kansas Medical Center |

| Kentucky | Lexington | University of Kentucky Chandler Medical Center |

| University of Kentucky Good Samaritan Hospital | ||

| Massachusetts | Boston | Boston Children's Hospital |

| Worcester | University of Massachusetts Memorial Medical Center | |

| Michigan | Grand Rapids | Corewell Health (previously Spectrum Health Hospitals) |

| Mississippi | Jackson | University of Mississippi Medical Center |

| Missouri | Kansas City | Children's Mercy Hospitals & Clinics |

| St. Louis | Missouri Baptist Medical Center | |

| Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis | ||

| Nebraska | Omaha | University of Nebraska Medical Center |

| New Jersey | Newark | Rutgers/New Jersey Medical School |

| New York | Rochester | Strong Memorial Hospital |

| Syracuse | Upstate Medical University—Downtown Campus | |

| North Carolina | Charlotte | Carolinas Medical Center |

| Oregon | Portland | Doernbecher Children's Hospital |

| Oregon Health & Science University Hospital | ||

| Pennsylvania | Bethlehem | Lehigh Valley Hospital—Cedar Crest |

| Lehigh Valley Hospital—Muhlenberg | ||

| Philadelphia | Einstein Medical Center Philadelphia* | |

| York | York Hospital | |

| Texas | Dallas | Children's Medical Center Dallas |

| Parkland Memorial Hospital | ||

| William P. Clements Jr University Hospital | ||

| Houston | HCA Houston Healthcare Kingwood | |

| Virginia | Charlottesville | University of Virginia Health |

| Canada | Calgary | Foothills Medical Centre |

| England | London | Guy's and St Thomas' NHS Foundation Trust |

| St Thomas' Hospital | ||

| Israel | Haifa | Rambam Health Care Campus |

| Thailand | Bangkok | Vajira Hospital |

*New participating ToxIC sites in 2022

Demographics

In 2022, 47.7% of cases involved female patients, and 1.1% of patients identified as transgender or as gender non-conforming (50.6% female-to-male, 21.5% male-to-female and 26.6% as gender non-conforming). Among female patients, the pregnancy prevalence was 3.5% (Table 2).

Table 2.

Patient gender and pregnancy status.

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Female | 3437 (47.7) |

| Male | 3690 (51.2) |

| Transgender | 79 (1.1) |

| Female to malea | 40 (50.6) |

| Gender non-conforminga | 21 (26.6) |

| Male to femalea | 17 (21.5) |

| Missinga | 1 (1.3) |

| Total | 7206 (100) |

| Pregnantb | 119 (3.5) |

a Percentages based on total number of transgender cases (N = 79)

b Percentage based on number of cases in female patients (N = 3437)

The most prevalent age group was adults 19–65 years old (61.9%). Adolescents ages 13–18 comprised 19.3% of cases, 10.4% of cases were children ≤ 12 years of age, and 8.2% of cases were older adults > 65 years old (Table 3).

Table 3.

Patient age category.

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Less than 2 years old | 211 (2.9) |

| 2–6 years old | 299 (4.1) |

| 7–12 years old | 244 (3.4) |

| 13–18 years old | 1390 (19.3) |

| 19–65 years old | 4458 (61.9) |

| 66–89 years old | 583 (8.1) |

| Over 89 years old | 10 (0.1) |

| Age unknown | 11 (0.2) |

| Total | 7206 (100) |

Table 4 details patient race/ethnicity. Patients were primarily Non-Hispanic White (63.7%), followed by Black/African American (15.4%) and Hispanic (13.3%).

Table 4.

Patient race/ethnicity.

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 121 (1.7) |

| Asian | 154 (2.1) |

| Black/African American | 1113 (15.4) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 4588 (63.7) |

| Hispanic | 962 (13.3) |

| Mixed, not otherwise specified | 44 (0.6) |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 12 (0.2) |

| Race Other | 6 (0.1) |

| Race unknown | 206 (2.9) |

| Total | 7206 (100) |

Advanced Demographic Characteristics

Marital status and military service are reported for patients > 12 years of age (Table 5). The majority of patients reported being single (68.4%) followed by married or with a long-term partner (19.8%) and widowed (2.6%). Of the 41.5% with military status documented, the majority of patients (97.6%) reported no prior military service. Of the 2.4% who reported prior military service, 84.6% were retired or had former military service.

Table 5.

Patient marital status, military service, and housing situation.

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Marital Status | |

| Unknowna | 961 (14.9) |

| Total reported marital statusa | 5491 (85.1) |

| Singleb | 3757 (68.4) |

| Married or long-term partnerb | 1090 (19.8) |

| Divorced or separatedb | 503 (9.2) |

| Widowedb | 141 (2.6) |

| Military Service | |

| Unknowna | 3774 (58.5) |

| Total reported military servicea | 2678 (41.5) |

| No, previous military servicec | 2613 (97.6) |

| Yes, previous military servicec | 65 (2.4) |

| Former/retiredd | 55 (84.6) |

| Current (including reserves)d | 5 (7.7) |

| Unknown if former/currentd | 5 (7.7) |

| Housing Status | |

| Unknowne | 575 (8.0) |

| Total reported housing statuse | 6631 (92.0) |

| Secured housing (home or stable living situation)f | 6150 (92.7) |

| Undomiciled (homelessness, unsecured housing)f | 388 (5.9) |

| Non-criminal supervised care (foster, group home, nursing home)f | 25 (0.4) |

| Rehabilitation or psychiatric facilityf | 21 (0.3) |

| Correctional related facility (jail, prison, incarceration)f | 39 (0.6) |

| Otherf | 8 (0.1) |

a Percentages based on patients age > 12 years old (N = 6452)

b Percentages based on total cases reporting marital status (N = 5491)

c Percentages based on total cases reporting military service (N = 2678)

d Percentages based on total cases reporting yes, previous military service (N = 65)

e Percentages based on total reported cases (N = 7206)

f Percentages based on total cases reporting housing status (N = 6631)

Among patients with housing status information (92.0%), most patients (92.7%) reported a secure or stable living situation and 5.9% reported being undomiciled, where they were experiencing homelessness or an unstable living situation.

Source of Medical Toxicology Referral and Location of Patient Consultation Encounter

Table 6 details the sources of medical toxicology physician consultation referral for inpatient and outpatient encounters. In-hospital consultations primarily consisted of referrals from the Emergency Department (55.5%) or admitting service (33.4%). Few consultations were poison center referrals (0.8%) or primary care/outpatient physician referrals (0.1%). The majority of outpatient consultations in a clinic or office were referred by a primary care or other outpatient physician (59.7%) followed by patient self-referrals (24.3%).

Table 6.

Case referral sources by inpatient/ outpatient status.

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Emergency Department (ED) or Inpatient (IP)a | |

| ED | 3917 (55.5) |

| Admitting service | 2358 (33.4) |

| Request from another hospital service (not ED) | 448 (6.3) |

| Outside hospital transfer | 271 (3.8) |

| Poison Center | 56 (0.8) |

| Primary care provider or other outpatient treating physician | 5 (0.1) |

| Self-referral | 5 (0.1) |

| Employer/Independent medical evaluation | 2 (0.0) |

| Total | 7062 (100) |

| Outpatient (OP)/Clinic/Office Consultationb | |

| Primary care provider or other OP physician | 86 (59.7) |

| Self-referral | 35 (24.3) |

| Employer/Independent medical evaluation | 14 (9.7) |

| Admitting service | 3 (2.1) |

| ED | 3 (2.1) |

| Request from another hospital service (not ED) | 2 (1.4) |

| Outside hospital transfer | 1 (0.7) |

| Poison Center | 0 (0.0) |

| Total | 144 (100) |

a Percentages based on total number of cases (N = 7062) seen by a medical toxicologist as consultant (ED or IP) or as attending (IP)

b Percentages based on total number of cases (N = 144) seen by a medical toxicologist as outpatient, clinic visit, or office consultation

All patient locations at the time of the medical toxicology consultation are reported in Table 7. Patients could be initially evaluated in one location and have follow-up evaluations in another location. Therefore, patients could be seen in more than one location by the medical toxicology physician throughout their hospitalization. For example, if a patient was seen by a medical toxicology physician in the emergency department and then also seen by the medical toxicology physician on the hospital floor, the patient would have two locations for medical toxicology encounters. The majority of patients were seen by a toxicology physician in the Emergency Department (49.9%) while 23.1% were seen in the intensive care unit (ICU)/neonatal ICU (NICU).

Table 7.

Locations of medical toxicology encounters during hospitalization.

| N (%)a | |

|---|---|

| ED | 3524 (49.9) |

| Hospital floor | 2971 (42.1) |

| ICU/NICU | 1628 (23.1) |

| Observation unit | 136 (1.9) |

a Percentages based on total number of cases (N = 7062) seen by a medical toxicologist as consultant (ED or IP) or as attending (IP). Case numbers may include more than one hospital location for medical toxicology encounters. Only one unique case is represented within each location

Table 8 describes all locations of the patient during hospitalization. Most patients spent time in the Emergency Department (76.9%), hospital floor (60.2%), and critical care units (28.2%). Each patient may have more than one hospital location during their hospitalization.

Table 8.

Locations of patient during hospitalization.

| N (%)a | |

|---|---|

| ED | 5433 (76.9) |

| Hospital floor | 4253 (60.2) |

| Critical care unit | 1989 (28.2) |

| Observation unit | 214 (3.0) |

| Inpatient psychiatric unit | 192 (2.7) |

a Percentages based on total number of cases (N = 7062) seen by a medical toxicologist as consultant (ED or IP) or as attending (IP). Case numbers may include more than one hospital location. Only one unique case is represented within each location

Telemedicine referrals (Table 9) were primarily from the Emergency Department (42.5%) and admitting service (42.0%), followed by primary care provider or other outpatient treating physician (11.1%) and then by request from another hospital service outside of the emergency department (3.9%). The most common telemedicine encounters were conducted via video/internet (53.1%) and chart review only (44.0%). Only 2.9% were conducted over the phone. The top four reasons for telemedicine encounters included attempt at self-harm (26.6%), ethanol and/or alcohol withdrawal (17.3%), misuse/abuse (12.1%), and addiction medicine (10.6%).

Table 9.

Telemedicine encounters.

| N (%)a | |

|---|---|

| Source of Telemedicine Referral | |

| ED | 88 (42.5) |

| Admitting service | 87 (42.0) |

| Primary care provider or other outpatient treating physician | 23 (11.1) |

| Request from another hospital service (not ED) | 8 (3.9) |

| Self-referral | 1 (0.5) |

| Nature of Telemedicine Consultation | |

| Patient encounter via video/internet | 110 (53.1) |

| Chart review only | 91 (44.0) |

| Patient encounter over the phone | 6 (2.9) |

| Reason for Telemedicine Encounter | |

| Attempt at self-harmb | 55 (26.6) |

| Misuse/abuseb | 25 (12.1) |

| Addiction medicine consultc | 22 (10.6) |

| Withdrawal – Ethanol | 21 (10.1) |

| Withdrawal – opioids | 19 (9.2) |

| Environmental evaluation | 18 (8.7) |

| Unintentional pharmaceutical and/or nonpharmaceutical exposures | 17 (8.2) |

| Ethanol abuse | 15 (7.2) |

| Interpretation of laboratory data | 7 (3.4) |

| Miscellaneousd | 16 (7.2) |

| Total Telemedicine Encounters | 207 (100) |

a Percentages based on total cases indicating a telemedicine consultation (N = 207)

b Includes intentional pharmaceutical and/or intentional nonpharmaceutical exposures

c Includes opioid agonist therapy, opioid antagonist therapy, pain management, and alcohol dependency pharmacotherapy

d Includes envenomation (snake), occupational evaluation, organ system dysfunction, withdrawal (sedative), and withdrawal (other)

Table 10 describes the primary reason for the medical toxicology encounter. Similar to past years, intentional pharmaceutical exposures were the most common reason for medical toxicology encounters (32.0%). Among intentional pharmaceutical exposures (Table 11), most cases were attempts at self-harm (73.6%), and 12.7% were classified as misuse/abuse. Among the patients with reported self-harm attempts, the majority of these attempts were classified as suicidal intent (82.2%) and 3.9% were classified as no suicidal intent. The remaining patients (13.7%) had unknown suicidal intent.

Table 10.

Reason for medical toxicology encounter.

| N (%)a | |

|---|---|

| Intentional exposure—pharmaceutical | 2654 (32.0) |

| Withdrawal—ethanol | 1010 (12.2) |

| Ethanol abuse | 806 (9.7) |

| Intentional exposure—non-pharmaceutical | 723 (8.7) |

| Withdrawal—opioid | 635 (7.7) |

| Addiction medicine consultation | 527 (6.4) |

| Unintentional exposure—pharmaceutical | 493 (5.9) |

| Organ system dysfunction | 341 (4.1) |

| Unintentional exposure—non-pharmaceutical | 328 (4.0) |

| Envenomation—snake | 268 (3.2) |

| Interpretation of toxicology lab data | 188 (2.3) |

| Environmental evaluation | 127 (1.5) |

| Withdrawal—sedative/hypnotic | 77 (0.9) |

| Envenomation—spider | 33 (0.4) |

| Withdrawal—cocaine/amphetamine | 29 (0.3) |

| Occupational evaluation | 21 (0.3) |

| Withdrawal—other | 15 (0.2) |

| Malicious/criminal | 9 (0.1) |

| Envenomation—other | 8 (0.1) |

| Envenomation—scorpion | 4 (0.0) |

| Marine /fish poisoning | 0 (0.0) |

| Total | 8296 (100) |

a Percentages based on total number of reasons for toxicology encounter (N = 8296). Case entries may include more than one reason for a medical toxicology encounter

Table 11.

Detailed reason for encounter—intentional pharmaceutical exposurea.

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Reason for Intentional Pharmaceutical Exposure Subgroupb | |

| Attempt at self-harm | 1948 (73.6) |

| Misuse/abuse | 337 (12.7) |

| Therapeutic use | 230 (8.7) |

| Unknown | 137 (5.2) |

| Attempt at Self-harm—Suicidal Intent Subclassificationc | |

| Suicidal intent | 1602 (82.2) |

| Suicidal intent unknown | 266 (13.7) |

| No suicidal intent | 75 (3.9) |

a Eight cases listed more than one reason for encounter due to intentional pharmaceutical exposure

b Percentage based on number of cases reporting intentional pharmaceutical exposure (N = 2646)

c Percentage based on number of cases indicating attempt at self-harm (N = 1948)

Table 12 describes addiction medicine consultations reported in 2022. Addiction medicine consults accounted for 7.3% of all medical toxicology encounters. The majority of consultations were for opioid agonist therapy (68.7%) followed by counseling and support (14.2%) and pain management (8.7%).

Table 12.

Addiction medicine consultations.

| N (%)a | |

|---|---|

| Opioid agonist therapy | 362 (68.7) |

| Counseling and support only | 75 (14.2) |

| Pain management | 46 (8.7) |

| Alcohol dependence pharmacotherapy | 34 (6.5) |

| Opioid antagonist therapy | 10 (1.9) |

| Total | 527 (100) |

a Percentage based on total number indicating addiction medicine consultations (N = 527)

Agent Classes

Patient toxicologic exposure by agent class reported during the medical toxicology consultation are described in Table 13. The total number of agent classes reported was 9310. Of the 7206 cases entered into the Core Registry in 2022, 6456 included at least one specific agent of exposure. Single agents were involved in 4662 (72.2%) cases. The top three most prevalent exposure classes were opioids (15.9%), ethanol (14.9%), and analgesics (12.8%).

Table 13.

Exposure agent classes reported in medical toxicology consultations.

| N (%)a | |

|---|---|

| Opioid | 1483 (15.9) |

| Ethanol | 1384 (14.9) |

| Analgesic | 1190 (12.8) |

| Antidepressant | 838 (9.0) |

| Sympathomimetic | 746 (8.0) |

| Sedative-hypnotic/muscle relaxant | 554 (6.0) |

| Anticholinergic/antihistamine | 487 (5.2) |

| Cardiovascular | 460 (4.9) |

| Psychoactive | 354 (3.8) |

| Antipsychotic | 321 (3.4) |

| Envenomation | 291 (3.1) |

| Anticonvulsant | 173 (1.9) |

| Gases/irritants/vapors/dusts | 118 (1.3) |

| Diabetic medication | 101 (1.1) |

| Metals | 99 (1.1) |

| Lithium | 83 (0.9) |

| Herbal products/dietary supplements | 70 (0.8) |

| Toxic alcohols | 60 (0.6) |

| Cough and cold products | 60 (0.6) |

| Antimicrobials | 44 (0.5) |

| Other pharmaceutical product | 41 (0.4) |

| Caustic | 40 (0.4) |

| Plants and fungi | 40 (0.4) |

| Unknown class | 38 (0.4) |

| Household products | 36 (0.4) |

| Chemotherapeutic and immune | 24 (0.3) |

| Gastrointestinal | 24 (0.3) |

| Hydrocarbon | 24 (0.3) |

| Anesthetic | 21 (0.2) |

| Endocrine | 20 (0.2) |

| Other nonpharmaceutical product | 20 (0.2) |

| Anticoagulant | 19 (0.2) |

| Insecticide | 16 (0.2) |

| Ingested foreign body | 7 (0.1) |

| Amphetamine-like hallucinogen | 5 (0.1) |

| Anti-parkinsonism drugs | 5 (0.1) |

| Pulmonary | 5 (0.1) |

| Rodenticide | 4 (0.0) |

| Herbicide | 3 (0.0) |

| Chelators | 1 (0.0) |

| WMDb/riot agent/radiological | 1 (0.0) |

| Cholinergic | 0 (0.0) |

| Fungicide | 0 (0.0) |

| Marine toxin | 0 (0.0) |

| Photosensitizing agents | 0 (0.0) |

| Total agents | 9310 (100) |

a Percentages based on total number of reported agent entries from N = 6456 cases; 4662 registry cases (72.2%) reported single agents

b WMD: Weapon of Mass Destruction

Opioids

Opioid agents are listed in Table 14. Fentanyl was the most commonly reported opioid agent in 2022 (53.9%), while the proportion of heroin cases within the opioid agent class was only 9.4%. Oxycodone (8.1%), methadone (7.0%), and unspecified opioids (6.8%) were the next most frequently reported agents.

Table 14.

Opioids.

| N (%)a | |

|---|---|

| Fentanyl | 798 (53.9) |

| Heroin | 139 (9.4) |

| Oxycodone | 120 (8.1) |

| Methadone | 104 (7.0) |

| Opioid Unspecified | 101 (6.8) |

| Buprenorphine | 72 (4.9) |

| Hydrocodone | 34 (2.3) |

| Tramadol | 31 (2.1) |

| Morphine | 28 (1.9) |

| Hydromorphone | 14 (0.9) |

| Codeine | 11 (0.7) |

| Naloxone | 8 (0.5) |

| Naltrexone | 6 (0.4) |

| Miscellaneousb | 17 (1.1) |

| Class total | 1483 (100) |

a Percentages based on total number of reported opioid class entries

b Includes acetyl fentanyl, depropionylfentanyl, desomorphine, isotonitazene, loperamide, meperidine, N,N-disubstituted piperazine (MT-45), norfentanyl, opium, opium tincture, tapentadol, and U47700

Ethanol and Toxic Alcohols

Ethanol was considered its own agent class separate from non-ethanol toxic alcohols (Table 15). The most commonly reported non-ethanol alcohols and glycols were isopropanol (40.0%), ethylene glycol (18.3%) and methanol (18.3%).

Table 15.

Ethanol and toxic alcohols.

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Ethanola | 1384 (100) |

| Toxic alcoholb | |

| Isopropanol | 24 (40.0) |

| Ethylene glycol | 11 (18.3) |

| Methanol | 11 (18.3) |

| Acetone | 5 (8.4) |

| Miscellaneousc | 9 (15.0) |

| Class total | 60 (100) |

a Ethanol is considered a separate agent class

b Percentages based on total number of reported toxic alcohol (non-ethanol alcohols and glycols) class entries

c Includes diethylene glycol, propylene glycol, benzyl alcohol, ethylene glycol monohexyl ether, and toxic alcohol unspecified

Analgesics

Among the non-opioid analgesic class, acetaminophen was the most prevalent agent (67.3%) (Table 16). Ibuprofen was the next most commonly reported agent (13.1%), followed by gabapentin (6.2%). Aspirin and acetylsalicylic acid are listed as separate agents in the Core Registry, but when combined they made up 7.9% of the agent class.

Table 16.

Analgesics.

| N (%)a | |

|---|---|

| Acetaminophen | 801 (67.3) |

| Ibuprofen | 156 (13.1) |

| Gabapentin | 74 (6.2) |

| Aspirin | 61 (5.1) |

| Acetylsalicylic acid | 33 (2.8) |

| Naproxen | 31 (2.6) |

| Salicylic acid | 13 (1.1) |

| Pregabalin | 9 (0.8) |

| Analgesic unspecified | 5 (0.4) |

| Miscellaneousb | 7 (0.6) |

| Class total | 1190 (100) |

a Percentages based on total number of reported analgesic class entries

b Includes celecoxib, flurbiprofen, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory (NSAID) unspecified, meloxicam, phenazopyridine, and phenylbutazone

Antidepressants

Table 17 describes the antidepressant class agents. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) (43.9%) and other antidepressants (38.9%) represented the majority of agents. Sertraline (16.0%) was the most common SSRI reported. The other antidepressant category consisted of bupropion (24.5%), trazodone (10.6%), mirtazapine (3.2%), and other miscellaneous antidepressants (0.6%). Tricyclic antidepressants were reported in 8.0% of cases.

Table 17.

Antidepressants.

| N (%)a | |

|---|---|

| Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) | 368 (43.9) |

| Sertraline | 134 (16.0) |

| Fluoxetine | 102 (12.2) |

| Escitalopram | 76 (9.1) |

| Citalopram | 34 (4.0) |

| Paroxetine | 12 (1.4) |

| Vilazodone | 6 (0.7) |

| Miscellaneousb | 4 (0.5) |

| Other antidepressants | 326 (38.9) |

| Bupropion | 205 (24.5) |

| Trazodone | 89 (10.6) |

| Mirtazapine | 27 (3.2) |

| Miscellaneousc | 5 (0.6) |

| Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) | 77 (9.2) |

| Venlafaxine | 42 (5.0) |

| Duloxetine | 25 (3.0) |

| Desvenlafaxine | 9 (1.1) |

| Miscellaneousd | 1 (0.1) |

| Tricyclic Antidepressants (TCAs) | 67 (8.0) |

| Amitriptyline | 44 (5.2) |

| Doxepin | 13 (1.6) |

| Miscellaneouse | 10 (1.2) |

| Class total | 838 (100) |

a Percentages based on total number of reported antidepressant class entries

b Includes fluvoxamine

c Includes antidepressant unspecified, tranylcypromine, and vortioxetine

d Includes levomilnacipran

e Includes clomipramine, amoxapine, imipramine, desipramine, nortriptyline, and tianeptine

Sympathomimetics

Table 18 presents the sympathomimetic class. The three most common agents in 2022 were methamphetamine (42.4%), cocaine (30.2%), and amphetamine (8.8%).

Table 18.

Sympathomimetic agents.

| N (%)a | |

|---|---|

| Methamphetamine | 316 (42.0) |

| Cocaine | 225 (30.0) |

| Amphetamine | 66 (8.8) |

| Methylphenidate | 41 (5.4) |

| Dextroamphetamine | 26 (3.5) |

| 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA), Ecstasy) | 21 (2.8) |

| Lisdexamfetamine | 13 (1.7) |

| Atomoxetine | 7 (0.9) |

| Dexmethylphenidate | 6 (0.8) |

| Phentermine | 5 (0.7) |

| Phenylephrine | 5 (0.7) |

| Miscellaneousb | 20 (2.7) |

| Class total | 751 (100) |

a Percentages based on total number of reported sympathomimetic class entries

b Includes 2C-T-7 (designer phenethylamine), 3-Fluoroethamphetamine (3-FEA), 4-Fluoroamphetamine (4-FA), alpha-Pyrrolidinopentiophenone (alpha-PVP), cathinone, clenbuterol, diethylpropion, epinephrine, isometheptene, methylenedioxyethylamphetamine (MDE), mixed amphetamine salts, naphazoline, pseudoephedrine, sympathomimetic unspecified, and tetrahydrozoline

Sedative Hypnotics/Muscle Relaxants

Benzodiazepines (Table 19) represented the majority (63.2%) of the sedative-hypnotic/muscle relaxant class, followed by muscle relaxants (20.6%), other sedatives (9.0%), non-benzodiazepine agonists (5.4%), and barbiturates (1.8%). The benzodiazepines alprazolam (22.9%) and clonazepam (14.6%) were the most common individual agents overall, followed by the muscle relaxant baclofen (8.5%).

Table 19.

Sedative-hypnotic/muscle relaxants by type.

| N (%)a | |

|---|---|

| Benzodiazepine | 350 (63.2) |

| Alprazolam | 127 (22.9) |

| Clonazepam | 81 (14.6) |

| Lorazepam | 44 (8.0) |

| Diazepam | 16 (2.9) |

| Miscellaneousb | 22 (4.0) |

| Benzodiazepine unspecified | 60 (10.8) |

| Muscle Relaxant | 114 (20.6) |

| Baclofen | 47 (8.5) |

| Cyclobenzaprine | 35 (6.3) |

| Tizanidine | 13 (2.4) |

| Methocarbamol | 11 (2.0) |

| Carisoprodol | 8 (1.4) |

| Other Sedatives | 50 (9.0) |

| Buspirone | 40 (7.2) |

| Miscellaneousc | 7 (1.3) |

| Sed-Hypnotic/Muscle Relaxant unspecified | 3 (0.5) |

| Non-benzodiazepine agonists ('Z' drugs) | 30 (5.4) |

| Zolpidem | 23 (4.1) |

| Miscellaneousd | 7 (1.3) |

| Barbituratese | 10 (1.8) |

| Class total | 554 (100) |

a Percentages based on total number of reported sedative-hypnotic/muscle relaxant class entries

b Includes bromazepam, brotizolam, chlorazepate, chlordiazepoxide, clonazolam, clorazepate, etizolam, flubromazepam, midazolam, nitrazepam, and temazepam

c Includes phenibut and propofol

d Includes eszopiclone and zopiclone

e No agent in class with 5 or more occurrences. Includes barbiturate unspecified, butabarbital, butalbital, pentobarbital, and phenobarbital

Anticholinergic/Antihistamine

Table 20 describes the anticholinergic/antihistamine class specific agent exposures. Diphenhydramine (56.3%) and hydroxyzine (21.2%) were the most prevalent reported agents in this class.

Table 20.

Anticholinergics and antihistamines.

| N (%)a | |

|---|---|

| Diphenhydramine | 274 (56.3) |

| Hydroxyzine | 103 (21.2) |

| Benztropine | 20 (4.1) |

| Doxylamine | 15 (3.1) |

| Cetirizine | 13 (2.7) |

| Promethazine | 8 (1.6) |

| Loratadine | 7 (1.4) |

| Dimenhydrinate | 6 (1.2) |

| Pyrilamine | 5 (1.0) |

| Antihistamine unspecified | 8 (1.6) |

| Miscellaneousb | 28 (5.8) |

| Class total | 487 (100) |

a Percentages based on total number of reported anticholinergic/antihistamine class entries

b Includes anticholinergic unspecified, chlorpheniramine, cinnarizine, cyproheptadine, fesoterodine, homatropine, hyoscyamine, levocetirizine, meclizine, oxybutynin, propantheline, and scopolamine

Cardiovascular Agents

Among cardiovascular agents, sympatholytic alpha-2-agonists (29.5%) remain the most common subclass (Table 21). This was followed by beta blockers (26.3%) and calcium channel blockers (16.1%). Among the cardiovascular agents, clonidine (21.3%), amlodipine (10.9%), and propranolol (10.2%) were the most common individual agents reported.

Table 21.

Cardiovascular agents by type.

| N (%)a | |

|---|---|

| Alpha-2 Agonist | 136 (29.5) |

| Clonidine | 98 (21.3) |

| Guanfacine | 36 (7.8) |

| Miscellaneousb | 2 (0.4) |

| Beta Blockers | 121 (26.3) |

| Propranolol | 47 (10.2) |

| Metoprolol | 34 (7.4) |

| Carvedilol | 25 (5.4) |

| Atenolol | 5 (1.1) |

| Miscellaneousc | 10 (2.2) |

| Calcium Channel Blocker | 74 (16.1) |

| Amlodipine | 50 (10.9) |

| Diltiazem | 10 (2.2) |

| Verapamil | 8 (1.7) |

| Miscellaneousd | 6 (1.3) |

| ACEI/ARB | 39 (8.5) |

| Lisinopril | 25 (5.4) |

| Losartan | 11 (2.4) |

| Miscellaneouse | 3 (0.7) |

| Other antihypertensives and vasodilators | 35 (7.6) |

| Prazosin | 20 (4.4) |

| Hydralazine | 7 (1.5) |

| Miscellaneousf | 8 (1.7) |

| Cardiac Glycosides | 23 (5.0) |

| Digoxin | 23 (5.0) |

| Diuretics | 17 (3.7) |

| Hydrochlorothiazide | 9 (2.0) |

| Miscellaneousg | 8 (1.7) |

| Antidysrhythmics and other CV Agents | 10 (2.2) |

| Miscellaneoush | 10 (2.2) |

| Antihyperlipidemic | 5 (1.1) |

| Miscellaneousi | 5 (1.1) |

| Class total | 460 (100) |

a Percentages based on total number of reported cardiovascular class entries

b Includes xylazine

c Includes beta blockers unspecified, bisoprolol, labetalol, and nadolol

d Includes calcium channel blocker unspecified and nifedipine

e Includes isosorbide, minoxidil, nitroprusside, and tamsulosin

f Includes benazepril, captopril, and ramipril

g Includes amiloride, chlorthalidone, furosemide, and chlorthalidone

h No agent in class with 5 or more occurrences. Includes alkyl nitrite, amiodarone, dihydroergotamine, dofetilide, and flecainide

i No agent in class with 5 or more occurrences. Includes atorvastatin and rosuvastatin

Psychoactives

The psychoactive classes include psychoactives such as cannabis, ketamine, and lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) (Table 22). Among the psychoactive agents, cannabis (32.2%) was the most prevalent agent in this class, followed by tetrahydrocannabinol (31.1%). Synthetic cannabinoid cases comprised 4.0% of other psychoactive agents.

Table 22.

Psychoactives.

| N (%)a | |

|---|---|

| Cannabis | 114 (32.2) |

| Tetrahydrocannabinolb | 110 (31.1) |

| Gamma hydroxybutyrate | 26 (7.3) |

| Cannabinoid NonSynthetic | 17 (4.8) |

| Cannabinoid Synthetic | 14 (4.0) |

| Nicotine | 13 (3.7) |

| Delta-8-tetrahydrocannabinol | 11 (3.1) |

| Phencyclidine | 10 (2.8) |

| Cannabidiol | 9 (2.5) |

| Ketamine | 6 (1.7) |

| LSDc | 5 (1.4) |

| Miscellaneousd | 19 (5.4) |

| Class total | 354 (100) |

a Percentages based on total number of reported psychoactive class entries

b Tetrahydrocannabinol (cannabis) also includes reports of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol

c LSD: lysergic acid diethylamide

d Includes 1,4-Butanediol, 3-Methoxyphencyclidine, 5-MeO-DMT (O-methyl-bufotenin), donepezil, gamma butyrolactone, hallucinogen unspecified, hallucinogenic amphetamines, LAMPA (lysergic acid N,N-methylpropylamide), racetam unspecified, and THC-O acetate (ATHC)

Antipsychotics

Quetiapine (40.5%) was the most commonly reported antipsychotic agent, followed by aripiprazole (14.3%) and olanzapine (13.7%) (Table 23).

Table 23.

Antipsychotics.

| N (%)a | |

|---|---|

| Quetiapine | 130 (40.5) |

| Aripiprazole | 46 (14.3) |

| Olanzapine | 44 (13.7) |

| Risperidone | 35 (10.9) |

| Haloperidol | 21 (6.5) |

| Paliperidone | 10 (3.2) |

| Clozapine | 8 (2.5) |

| Lurasidone | 6 (1.9) |

| Miscellaneousb | 21 (6.5) |

| Class total | 321 (100) |

a Percentages based on total number of reported antipsychotic class entries

b Includes antipsychotic unspecified, asenapine, brexpiprazole, cariprazine, chlorpromazine, droperidol, fluphenazine, loxapine, prochlorperazine, thioidazine, and ziprasidone

Envenomations

Table 24 shows data on envenomations and marine poisonings; however, no marine envenomations were reported in 2022. Snakes were the most prevalent type of envenomation (87.6%). Among snake envenomations, Agkistrodon (44.7%) and Crotalus (38.0%) were most frequently reported. Loxosceles spider exposures were reported in 6.9% of all envenomations.

Table 24.

Envenomations.

| N (%)a | |

|---|---|

| Agkistrodon (Copperhead, Cottonmouth/Water moccasin) | 114 (39.2) |

| Crotalus (Rattlesnake) | 97 (33.3) |

| Snake unspecified | 33 (11.3) |

| Loxosceles (Recluse spiders) | 20 (6.9) |

| Miscellaneous snakesb | 11 (3.8) |

| Miscellaneous insects and arachnidsc | 9 (3.1) |

| Miscellaneous scorpionsd | 4 (1.4) |

| Other miscellaneous envenomationse | 3 (1.0) |

| Class total | 291 (100) |

a Percentages based on total number of reported envenomation class entries

b Includes Aspidelaps lubricus (Coral Cobra), Dendroaspis (Mamba species), Hydrodynastes gigas (False Water Cobra), Sistrurus (Minor Rattlesnakes incl Pygmy, Massasauga), Thamnophis elegans (Western terrestrial garter snake), Trimeresurus albolabris (var Pit viper incl white lipped, green tree), Trimeresurus unspecified (Pit viper unspecified), and Vipera palaestinae

c Includes Hymenoptera (bees, wasps, ants), Latrodectus (widow spiders), and spider unspecified

d Includes Centruroides (var Scorpion incl Bark) and Centruroides sculpturatus (Arizona bark scorpion)

e Includes animal bite unspecified, envenomation unspecified, and Varanus komodoensis (Komodo dragon)

Anticonvulsants, Mood Stabilizers, and Lithium

Lithium was considered its own agent class from other anticonvulsant and mood stabilizer agents (Table 25). Lithium was the most common anticonvulsant and mood stabilizer overall with 83 cases. Among other anticonvulsants/mood stabilizers, valproic acid (24.3%) and lamotrigine (22.5%) were the most commonly reported agents, followed by carbamazepine (13.9%) and phenytoin (9.8%).

Table 25.

Anticonvulsants and mood stabilizers.

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Lithiuma | 83 (100.0) |

| Other anticonvulsants/mood stabilizersb | |

| Valproic acid | 42 (24.3) |

| Lamotrigine | 39 (22.5) |

| Carbamazepine | 24 (13.9) |

| Phenytoin | 17 (9.8) |

| Topiramate | 15 (8.7) |

| Oxcarbazepine | 10 (5.8) |

| Divalproex | 9 (5.2) |

| Clobazam | 5 (2.9) |

| Miscellaneousc | 12 (6.9) |

| Class total | 173 (100) |

a Lithium is considered a separate agent class

b Percentages based on total number of reported anticonvulsant and mood stabilizer class entries

c Includes anticonvulsant unspecified, brivaracetam, eslicarbazepine, lacosamide, levetiracetam, perampanel, primidone, and zonisamide

Other Agents

Other agent classes are displayed in order of reported frequency in Supplemental Tables S1-S23.

Clinical Signs and Symptoms

Specific signs and symptoms relating to toxicological exposures are collected within the Core Registry to highlight the manifestations of toxicity from single or multiple agent exposures. These clinical signs and symptoms represent a heterogeneous group of abnormal findings. Each specific sign or symptom has predefined criteria required to be met. Additionally, each case may report more than one clinical sign and symptom within a group or across groups. In 2022, 79.8% (N = 5750) of all cases reported at least one sign/symptom. Among the cases with reported signs/symptoms, 84.8% had signs/symptoms that were considered by the medical toxicology physician to be most likely related to a toxic exposure.

Toxidromes

Toxidromes are listed in Table 26. In 2022, 24.6% of the total cases in the Core Registry (N = 7206) had at least one toxidrome reported. Among all cases in 2022, opioid toxidromes were the most prevalent (9.2%). Sedative-hypnotic (4.9%), anticholinergic (4.1%), and sympathomimetic (3.1%) were also commonly reported toxidromes.

Table 26.

Toxidromes.

| N (%)a | |

|---|---|

| Cases with signs/symptoms, but no toxidrome reported | 3965 (55.0) |

| Cases with one or more toxidromes reported | 1775 (24.6) |

| Total Reported Toxidromesb | 1912 |

| Opioid | 662 (9.2) |

| Sedative-hypnotic | 352 (4.9) |

| Anticholinergic | 296 (4.1) |

| Sympathomimetic | 225 (3.1) |

| Alcoholic ketoacidosis | 186 (2.6) |

| Serotonin syndrome | 120 (1.7) |

| Sympatholytic | 29 (0.4) |

| Washout syndrome | 13 (0.2) |

| Cholinergic | 11 (0.2) |

| Neuroleptic malignant syndrome | 6 (0.1) |

| Cannabinoid hyperemesis | 6 (0.1) |

| Overlap syndromes | 5 (0.1) |

| Anticonvulsant hypersensitivity | 1 (0.0) |

a Percentage based on number of cases reporting toxidromes relative to total number of registry cases (N = 7206)

b Cases may be associated with more than one toxidrome

Major Vital Sign Abnormalities

Major vital sign abnormalities with the clinical parameters for each category are listed in Table 27. In 2022, 21.0% of all cases had one or more major vital sign abnormality. Tachycardia (11.3%) was the most common vital sign abnormality among all cases in the Core Registry in 2022, followed by hypotension (5.0%), hypertension (3.6%), bradycardia (3.4%), bradypnea (2.2%), and hyperthermia (0.5%).

Table 27.

Major vital sign abnormalities.

| N (%)a | |

|---|---|

| Cases with signs/symptoms, but no major vital sign abnormality | 4231 (58.7) |

| Cases with one or more major vital sign abnormality | 1509 (21.0) |

| Total Reported Major Vital Sign Abnormalitiesb | 1869 |

| Tachycardia (HRc > 140 beats per minute) | 816 (11.3) |

| Hypotension (systolic BPd < 80 mmHg) | 361 (5.0) |

| Hypertension (systolic BPd > 200 mmHg and/or diastolic BPd > 120 mmHg) | 258 (3.6) |

| Bradycardia (HRc < 50 beats per minute) | 246 (3.4) |

| Bradypnea (RRe < 10 breaths per minute) | 155 (2.2) |

| Hyperthermia (temp > 105° F) | 33 (0.5) |

a Percentage based on number of cases reporting major vital sign abnormalities relative to the total number of registry cases (N = 7206)

b Cases may be associated with more than one major vital sign abnormality

c HR: heart rate

d BP: blood pressure

e RR: respiratory rate

Clinical Signs and Symptoms – Neurologic

Neurological signs and symptoms were reported in 44.8% of all 2022 Core Registry cases (Table 28). Coma/CNS depression (19.2%), agitation (13.1%), hyperreflexia/myoclonus/clonus/tremor (10.2%), and delirium/toxic psychosis (7.8%) were the most commonly documented neurological signs and symptoms.

Table 28.

Clinical signs and symptoms – neurologic.

| N (%)a | |

|---|---|

| Cases with signs/symptoms, but no neurologic effects | 2516 (34.9) |

| Cases with one or more neurologic effects | 3224 (44.8) |

| Total Reported Neurologic Clinical Effects b | 4498 |

| Coma/CNS depression | 1380 (19.2) |

| Agitation | 946 (13.1) |

| Hyperreflexia/Myoclonus/Clonus/Tremor | 733 (10.2) |

| Delirium/Toxic Psychosis | 559 (7.8) |

| Seizures | 399 (5.5) |

| Hallucination | 288 (4.0) |

| Weakness/Paralysis | 84 (1.2) |

| EPS/Dystonia/Rigidity | 59 (0.8) |

| Numbness/Paresthesia | 40 (0.6) |

| Peripheral Neuropathy (objective) | 10 (0.1) |

a Percentage based on number of cases reporting neurologic effects relative to total number of registry cases (N = 7206)

b Cases may be associated with more than one neurologic effect

Clinical Signs and Symptoms – Pulmonary and Cardiovascular

Pulmonary effects (10.6%) and cardiovascular effects (8.2%) are reported in Table 29. In 2022, among all Core Registry cases respiratory depression (9.3%) and QTc prolongation (6.5%) were the most common pulmonary and cardiovascular effects reported, respectively.

Table 29.

Clinical signs – pulmonary and cardiovascular.

| N (%)a | |

|---|---|

| Pulmonary | |

| Cases with signs/symptoms, but no pulmonary effects | 4980 (69.1) |

| Cases with one or more pulmonary effects | 760 (10.6) |

| Total Reported Pulmonary Effectsb | 840 |

| Respiratory depression | 670 (9.3) |

| Aspiration pneumonitis | 92 (1.3) |

| Acute lung injury/ARDSc | 48 (0.7) |

| Asthma/Reactive airway disease | 30 (0.4) |

| Cardiovascular | |

| Cases with signs/symptoms, but no cardiovascular effects | 5153 (71.6) |

| Cases with one or more cardiovascular effects | 587 (8.2) |

| Total Reported Cardiovascular Effectsb | 698 |

| Prolonged QTc (≥ 500 ms) | 468 (6.5) |

| Prolonged QRS (≥ 120 ms) | 117 (1.6) |

| Myocardial injury or infarction | 60 (0.8) |

| Ventricular dysrhythmia | 38 (0.5) |

| AV Block (> 1st degree) | 15 (0.2) |

a Percentage based on number of cases reporting pulmonary or cardiovascular effects relative to total number of registry cases (N = 7206)

b Cases may be associated with more than one pulmonary or cardiovascular effect

c ARDS: Acute respiratory distress syndrome

Clinical Signs – Other Organ Systems

Table 30 presents clinical signs involving other organ systems, including renal/musculoskeletal, metabolic, hematologic, gastrointestinal/hepatic, and dermatologic. Among these systems, the two with the most frequently reported manifestations were renal/musculoskeletal (6.7%) and metabolic (6.7%). Among all cases in the Core Registry in 2022 (N = 7206), the most commonly observed renal/musculoskeletal effects were acute kidney injury (4.2%) and rhabdomyolysis (3.5%), and the most commonly observed metabolic effects were metabolic acidosis (3.7%) and elevated anion gap (3.2%). Hematologic effects were reported in 6.4% of cases, gastrointestinal/hepatic effects were documented in 5.5%, and dermatologic effects were documented in 2.2%.

Table 30.

Clinical signs – other organ systems.

| N (%)a | |

|---|---|

| Renal/Musculoskeletal | |

| Cases with signs/symptoms, but no renal/musculoskeletal effects | 5256 (72.9) |

| Cases with one or more renal/musculoskeletal effects | 484 (6.7) |

| Total Reported Renal/Musculoskeletal Clinical Effectsb | 553 |

| Acute kidney injury (creatinine > 2.0 mg/dL) | 301 (4.2) |

| Rhabdomyolysis (CPKc > 1000 IU/L) | 252 (3.5) |

| Metabolic | |

| Cases with signs/symptoms, but no metabolic effects | 5261 (73.0) |

| Cases with one or more metabolic effects | 479 (6.7) |

| Total Reported Metabolic Clinical Effectsb | 645 |

| Metabolic acidosis (pH < 7.2) | 265 (3.7) |

| Elevated anion gap (> 20) | 227 (3.2) |

| Hypoglycemia (glucose < 50 mg/dL) | 123 (1.7) |

| Elevated osmole gap (> 20) | 30 (0.4) |

| Hematologic | |

| Cases with signs/symptoms, but no hematologic effects | 5280 (73.3) |

| Cases with one or more hematologic effects | 460 (6.4) |

| Total Reported Hematologic Clinical Effectsb | 578 |

| Thrombocytopenia (platelets < 100 K/µL) | 177 (2.5) |

| Hemolysis (Hgbd < 10 g/dL) | 159 (2.2) |

| Coagulopathy (PTe > 15 s) | 115 (1.6) |

| Leukocytosis (WBCf > 20 K/µL) | 83 (1.2) |

| Methemoglobinemia (MetHgb ≥ 2%) | 26 (0.4) |

| Pancytopenia | 18 (0.2) |

| Gastrointestinal/Hepatic | |

| Cases with signs/symptoms, but no gastrointestinal/hepatic effects | 5342 (74.1) |

| Cases with one or more gastrointestinal/hepatic effects | 398 (5.5) |

| Total Reported Gastrointestinal/Hepatic Clinical Effectsb | 522 |

| Hepatotoxicity (ASTg ≥ 1000 IU/L) | 183 (2.5) |

| Hepatotoxicity (ALTh 100—1000 IU/L) | 183 (2.5) |

| Hepatotoxicity (ALTh ≥ 1000 IU/L) | 84 (1.2) |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | 32 (0.4) |

| Pancreatitis | 30 (0.4) |

| Corrosive injury | 8 (0.1) |

| Intestinal ischemia | 2 (0.0) |

| Dermatologic | |

| Cases with signs/symptoms, but no dermatologic effects | 5584 (77.5) |

| Cases with one or more dermatologic effects | 156 (2.2) |

| Total Reported Dermatologic Clinical Effectsb | 189 |

| Rash | 91 (1.3) |

| Blister/Bullae | 29 (0.7) |

| Necrosis | 33 (0.5) |

| Angioedema | 16 (0.2) |

a Percentage based on number of cases reporting other organ system effects relative to total number of registry cases (N = 7206)

b Cases may be associated with more than category effect

c CPK: creatine phosphokinase

d Hgb: hemoglobin

e PT: prothrombin time

f WBC: white blood cells

g AST: aspartate aminotransferase

h ALT: alanine transaminase

The most common drugs associated with adverse drug reactions are displayed in Supplemental Table S24.

Fatalities

There were 118 fatalities in 2022, comprising 1.6% of the Core Registry cases. Single agent exposures were implicated in 55 cases (Table 31). Thirty-five cases involved multiple agents (Table 32), and in twenty-eight cases the toxicologic exposure agent(s) were unknown (Table 33). There were 47 fatality cases in which life support was withdrawn, representing 0.7% of Core Registry cases. Brain death was declared in 27 of these cases.

Table 31.

2022 Fatalities reported in ToxIC Core Registry with known toxicological exposurea: Single Agent.

| Age / Genderb | Agents Involved | Clinical Findingsc | Life Support Withdrawn |

Brain Death Confirmed |

Treatmentd |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 36 M | Acetaminophen | AG, AKI, CNS, CPT, HPT, HT, MA, PLT, QTC, RBM, TC, WBC | Yes | No | Continuous renal replacement therapy, glucose > 5%, hemodialysis, intubation, IV fluid resuscitation, methylene blue, NAC, vasopressors (epinephrine, norepinephrine, vasopressin), vitamin K |

| 52 F | Acetaminophen | AKI, ALI, CA, CNS, CPT, GIB, HGY, HPT, HT, PLT, PNC, TC | No | Benzodiazepines, continuous renal replacement therapy, CPR, factor replacement, glucose > 5%, intubation, IV fluid resuscitation, NAC, NaHCO3, octreotide, opioids, propofol, steroids, thiamine, transfusion, vasopressors (epinephrine, norepinephrine, phenylephrine, vasopressin) | |

| 53 F | Acetaminophen | AG, AKI, CNS, CPT, HGY, HPT, HT, MA, WAS | No | Glucose > 5%, NAC, transfusion | |

| 61 M | Acetaminophen | AG, AKI, CPT, HPT, HT, HYS, JD, MA, QTC | Yes | No | Fomepizole, glucose > 5%, glucagon, HIE, intubation, IV fluid resuscitation, NAC, NMB, propofol, transfusion, vasopressors (norepinephrine, vasopressin), vitamin K |

| 79 M | Acetaminophen | None | No | IV fluid resuscitation, NAC, vasopressors (norepinephrine) | |

| 17 M | Alprazolam | CNS, HT, SHS | No | None | |

| 16 F | Aspirin | None | No | NaHCO3 | |

| 52 F | Baclofen | AGT, BC, RD, SHS | No | Benzodiazepines, bronchodilators, intubation, IV fluid resuscitation, opioids, propofol | |

| 53 F | Bupivacaine | AG, AKI, AP, BC, BP, CA, CNS, HT, MA, QRS, RD, SZ, VD, WBC | Yes | No | Antiarrhythmics, anticonvulsants, antihypertensives, benzodiazepines, calcium, CPR, intubation, IV fluid resuscitation, lipid therapy, NaHCO3, opioids, propofol, therapeutic, vasopressors (epinephrine, norepinephrine) |

| 14 F | Bupropion | CA, CNS, HT, MA, QRS, RD, RFX | Unknown | Anticonvulsants, CPR, intubation, IV fluid resuscitation, NaHCO3, NMB, vasopressors (norepinephrine) | |

| 54 F | Carbon monoxide | None | No | None | |

| 69 F | Carbon monoxide | ALI, AP, HT, RBM, RD, TC | Unknown | Glucose > 5%, HBO, intubation, IV fluid resuscitation, opioids, vasopressors (epinephrine, norepinephrine) | |

| 69 M | Carbon monoxide | AKI, RBM, RD, RFX, TC | Unknown | Intubation, IV fluid resuscitation, propofol | |

| 85 M | Carbon monoxide | AVB, CNS, HYT, RFX, TC | No | HBO | |

| 69 F | Carvedilol | HT, QTC | No | Atropine, glucagon, IV fluid resuscitation, vasopressors (norepinephrine) | |

| 60 F | Citalopram | RFX, SS | Unknown | Benzodiazepines | |

| 68 M | Clonazepam | AGT, AVB, HAL, HGY, HPT, PAR | No | Benzodiazepines, glucose > 5%, intubation, IV fluid resuscitation, opioids | |

| 57 M | Cocaine | AGT | Unknown | None | |

| 74 F | Codeine | BP, CA, CNS, HT, MA, OT, RD | Yes | Yes | Cardioversion, continuous renal replacement therapy, CPR, intubation, NAC, naloxone/nalmefene, propofol, vasopressors (norepinephrine, vasopressin) |

| 74 M | Colchicine | None | Yes | No | None |

| 6 M | Crotalus (Rattlesnake) | AKI, CA, CNS, CPT, GIB, HT, MA, MI, PLT, RBM, RD, TC | Yes | Yes | Benzodiazepines, continuous renal replacement therapy, Fab antivenom, Fab2 antivenom, intubation, transfusion, vasopressors (epinephrine, norepinephrine, vasopressin) |

| 14 F | Diphenhydramine | AC, BC, BP, CNS, MA, RD, SZ, WBC | Yes | Yes | Anticonvulsants, benzodiazepines, intubation, IV fluid resuscitation, NAC, NMB, vasopressors (norepinephrine) |

| 15 F | Diphenhydramine | AC, DLM, QTC, TC | No | None | |

| 64 M | Diphenhydramine | CNS | No | Intubation, IV fluid resuscitation | |

| 26 F | Ethanol | AG, DLM, HPT, HTN, QTC, TC | No | Benzodiazepines, folate, intubation, IV fluid resuscitation, phenobarbital, thiamine | |

| 43 M | Ethanol | CNS, HPT, OG, QTC | No | Benzodiazepines, folate, glucagon, IV fluid resuscitation, thiamine | |

| 46 M | Ethanol | AKI, CNS, HGY, HT, QTC, RBM | Yes | Unknown | None |

| 61 M | Ethanol | AK, CA, PLT, QTC, TC | No | Acamprosate, benzodiazepines, bronchodilators, CPR, folate, glucagon, IV fluid resuscitation, thiamine | |

| 63 M | Ethanol | AKI, HPT, PLT, QRS, QTC, RFX, TC | No | Benzodiazepines, folate, nicotine replacement therapy, phenobarbital, thiamine | |

| 63 M | Ethanol | AKI, PLT, QRS, QTC, RFX | No | Benzodiazepines, folate, nicotine replacement therapy, phenobarbital, thiamine | |

| 86 M | Ethanol | None | No | Benzodiazepines, folate, IV fluid resuscitation, naltrexone, phenobarbital, thiamine | |

| 59 M | Ethylene glycol | MA, RD | Unknown | Continuous renal replacement therapy, fomepizole, hemodialysis for toxin removal, intubation, IV fluid resuscitation, thiamine, vasopressors (epinephrine) | |

| 15 M | Fentanyl | BC, CNS, OT, RD, SYS | Yes | Unknown | None |

| 17 M | Fentanyl | AG, AKI, BP, CA, CNS, MA, OT, RBM | Yes | Yes | Anticonvulsants, CPR, intubation, IV fluid resuscitation, naloxone/nalmefene, steroids |

| 23 M | Fentanyl | AKI, BC, BP, CNS, HGY, HPT, HT, MI, OT, QRS, RBM, RD, TC, VD | No | Continuous renal replacement therapy, glucose > 5%, IV fluid resuscitation, ketamine, naloxone/nalmefene, opioids, therapeutic hypothermia, vasopressors (norepinephrine, phenylephrine vasopressin) | |

| 37 F | Fentanyl | None | Yes | Yes | Buprenorphine/naloxone, intubation, opioids, propofol, steroids, vasopressors (epinephrine, norepinephrine, vasopressin) |

| 39 F | Fentanyl | AG, AKI, CA, CNS, CPT, HPT, HT, MA, OT, PCT, QRS, QTC, RD, VD, WBC | Yes | Yes | Antiarrhythmics, balloon pump, benzodiazepines, defibrillation, CPR, intubation, NaHCO3, naloxone/nalmefene, vasopressors (norepinephrine) |

| 41 M | Fentanyl | OT | Unknown | IV fluid resuscitation, methadone, opioids | |

| 44 F | Fentanyl | OT, RD, MHG | No | None | |

| 49 M | Fentanyl | HPT, MA, OT, RD, RFX | No | Intubation, IV fluid resuscitation, NAC | |

| 83 F | Flecainide | TC | Unknown | Magnesium | |

| 1 mo F | Homeopathic remedy unspecified | MA | Unknown | IV fluid resuscitation | |

| 22 F | Iron | BC | No | IV fluid resuscitation | |

| 23 mo M | Iron | BP, CNS, HT, MA, TC | Yes | Yes | Benzodiazepines, deferoxamine, ECMO, hemodialysis, IV fluid resuscitation, NMB, opioids, steroids, vasopressors (dopamine, epinephrine, norepinephrine), whole bowel irrigation |

| 64 F | Metformin | AG, AKI, HT, MA, OG, QTC, WBC | No | Benzodiazepines, continuous renal replacement therapy, intubation, IV fluid resuscitation, NaHCO3, steroids, thiamine, vasopressors (epinephrine, norepinephrine, vasopressin) | |

| 64 F | Metformin | AG, AKI, CNS, CPT, DLM, HG, HPT, HT, HYS, MA, OG, PLT, QTC, RBM, WBC | Yes | Yes | Continuous renal replacement therapy, glucose > 5%, intubation, IV fluid resuscitation, methylene blue, NaHCO3, vasopressors (epinephrine, norepinephrine, vasopressin) |

| 72 F | Metformin | AG, AKI, HT, MA, TC | No | Continuous renal replacement therapy, IV fluid resuscitation, NaHCO3, vasopressors (epinephrine, norepinephrine) | |

| 75 F | Metformin | AG, AKI, CNS, HTN, MA, PAR, RBM, SZ, TC | Yes | Yes | Antiarrhythmics, benzodiazepines, bronchodilators, continuous renal replacement therapy, intubation, IV fluid resuscitation, NaHCO3, opioids, propofol, vasopressors (norepinephrine, phenylephrine, vasopressin) |

| 32 F | Methadone | OT, RD | No | Methadone | |

| 43 F | Methamphetamine | OT, RD | No | None | |

| 16 M | Methanol | AG, BC, CNS, HT, RD | Yes | Yes | Folate, fomepizole, intubation, IV fluid resuscitation, propofol, thiamine |

| 31 M | Mixed Amphetamine Salts | CNS, HTN | Yes | Yes | Antihypertensives, intubation |

| 70 F | Morphine | BP, CNS, HYS, PLT | Unknown | IV fluid resuscitation, naloxone/nalmefene | |

| 66 M | Nadolol | HYS, MA, QTC, RD | Unknown | Intubation, IV fluid resuscitation, opioids | |

| 47 F | Tafenoquine | AG, CNS, MA, MHG, PLT, QTC | Unknown | Intubation, NMB |

a Based on response from Medical Toxicologist "Did the patient have a toxicological exposure?" equals Yes with known agent(s)

b Age in years unless otherwise stated. mo: months

c AC: anticholinergic, AG: anion gap, AGT: agitation, AK: alcoholic ketoacidosis, AKI: acute kidney injury, ALI: acute lung injury/ARDS, AP: aspiration pneumonitis, AVB: AV block, BC: bradycardia, BP: bradypnea, CA: cardiac arrest, CNS: coma/CNS depression, CPT: coagulopathy, DLM: delirium, GIB: GI bleeding, HAL: hallucination, HGY: hypoglycemia, HPT: hepatoxicity, HT: hypotension, HTN: hypertension, HYS: hemolysis, HYT: hyperthermia, JD: jaundice, MA: metabolic acidosis, MHG: methemoglobinemia, MI: myocardial injury/ischemia, OG: osmolar gap, OT: opioid toxidrome, PAR: paralysis/weakness, PCT: pancytopenia, PLT: thrombocytopenia, PNC: pancreatitis, QRS: QRS prolongation, QTC: QTc prolongation, RBM: rhabdomyolysis, RD: respiratory depression, RFX: hyperreflexia/clonus/tremor, SHS: sedative-hypnotic syndrome, SS: serotonin syndrome, SYS: sympathomimetic syndrome, SZ: seizures, TC: tachycardia, VD: ventricular dysrhythmia, WBC: leukocytosis

d Pharmacological and Non-pharmacological support as reported by Medical Toxicologist; CPR: cardiopulmonary resuscitation, ECMO: extra-corporeal membrane oxygenation, HBO: hyperbaric oxygenation, HIE: high dose insulin euglycemic therapy, NAC: n-acetyl cysteine, NaHCO3: sodium bicarbonate, NMB: neuromuscular blockers

Table 32.

2022 Fatalities reported in ToxIC Core Registry with known toxicological exposurea: Multiple Agents.

| Age / Genderb | Agents Involved | Clinical Findingsc | Life Support Withdrawn |

Brain Death Confirmed |

Treatmentd |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 83 F | Acetaminophen, aspirin | AKI, HT, RD | Yes | No | IV fluid resuscitation, NAC |

| 46 F | Acetaminophen, aspirin, phentermine | CNS, HGY, MA, QTC, RBM, RD, SYS, TC | Yes | Yes | Benzodiazepines, glucose > 5%, intubation, IV fluid resuscitation, NAC, opioids, propofol |

| 24 F | Acetaminophen, bupropion, lisdexamfetamine | CNS, HPT, HT, RAD | Yes | No | Benzodiazepines, dexmedetomidine, fomepizole, intubation, IV fluid resuscitation, NAC, vitamin K |

| 23 M | Acetaminophen, cocaine, oxycodone | AKI, BC, CA, CNS, HPT, HTN, HYT, MA, QTC, RD, WBC | Yes | Yes | Calcium, continuous renal replacement therapy, CPR, intubation, IV fluid resuscitation, NAC, NaHCO3, vasopressors (epinephrine, norepinephrine) |

| 64 M | Acetone, benzodiazepine unspecified, ethanol, ketamine, methanol, valproic acid | AKI, CNS, HGY, HT, QTC, RD, SZ | Yes | Yes | Activated charcoal, hemodialysis, intubation, IV fluid resuscitation |

| 24 F | Albuterol, famotidine, lorazepam, ondansetron, scopolamine | AC, TC | No | Benzodiazepines, IV fluid resuscitation | |

| 18 F | Amlodipine, benazepril, ranitidine | CNS, MA | No | Glucagon, HIE, hydroxocobalamin, intubation, IV fluid resuscitation, lipid therapy, NaHCO3, vasopressors (angiotensin, epinephrine, norepinephrine, vasopressin) | |

| 75 M | Amlodipine, carvedilol | BC, CPT, PLT, QRS, QTC | No | None | |

| 54 M | Amlodipine, metformin, propranolol | AG, AKI, CNS, CPT, HT, MA, RD | No | Continuous renal replacement therapy, intubation, IV fluid resuscitation, methylene blue, vasopressors (epinephrine, norepinephrine) | |

| 54 M | Amlodipine, metoprolol | BC, HT | Yes | Yes | Activated charcoal, balloon pump, calcium, continuous renal replacement therapy, CPR, ECMO, glucagon, glucose > 5%, HIE, intubation, IV fluid resuscitation, methylene blue, pacemaker, propofol, transfusion, vasopressors (epinephrine, milrinone, norepinephrine, vasopressin) |

| 25 F | Amphetamine, cocaine | AG, AKI, ALI, BP, CA, CNS, HPT, HT, MA, MI, RBM | Yes | Yes | CPR, intubation, vasopressors (norepinephrine, vasopressin) |

| 25 F | Apixaban, codeine, flecainide | AG, ALI, BC, CNS, HT, MA, QRS, QTC, RBM, RD, VD | No | Antiarrhythmics, atropine, cardioversion, continuous renal replacement therapy, CPR, ECMO, factor replacement, glucose > 5%, HIE, intubation, IV fluid resuscitation, lipid therapy, NaHCO3, vasopressors (epinephrine, norepinephrine, phenylephrine, vasopressin) | |

| 31 F | Bupropion, ethanol, fluoxetine, rizatriptan | QTC, RFX | No | Benzodiazepines, propofol | |

| 38 F | Bupropion, lamotrigine | CNS, HT | Yes | No | IV fluid resuscitation |

| 53 M | Carbon monoxide, Cyanide | ALI, CNS, HPT, HT, MI, RBM, TC | Yes | No | Hydroxocobalamin, vasopressors (epinephrine, norepinephrine, phenylephrine) |

| Unknown M | Carbon monoxide, Cyanide | AG, ALI, CNS, HT, MA, RBM | No | Benzodiazepines, hydroxocobalamin, IV fluid resuscitation, NMB, propofol | |

| 74 M | Carvedilol, hydralazine | AKI, BC, CNS, CPT, HPT, HT, MA, PLT, QRS, QTC, VD | No | Continuous renal replacement therapy, CPR, glucagon, intubation, IV fluid resuscitation, NaHCO3, pacemaker, propofol, vasopressors (epinephrine, norepinephrine, phenylephrine, vasopressin) | |

| 80 M | Clonidine, zolpidem | MA, RD, SHS | No | IV fluid resuscitation, naloxone/nalmefene | |

| 35 M | Cocaine, cyclobenzaprine, ethanol, lorazepam | RD | No | Intubation, IV fluid resuscitation | |

| 43 M | Cocaine, fentanyl | None | Unknown | Buprenorphine/naloxone, clonidine, IV fluid resuscitation | |

| 32 F | Cocaine, gamma butyrolactone | AG, ALI, BP, CNS, CPT, HPT, HT, MA, MI, OT, PLT, QRS, QTC, RD, SHS, VD | Yes | Yes | Calcium, CPR, dexmedetomidine, intubation, IV fluid resuscitation, NaHCO3, naloxone/nalmefene, transplantation |

| 35 F | Cocaine, gamma hydroxybutyrate, ketamine, MDMA (methylenedioxy-N-methamphetamine, ecstasy) | AG, ALI, CNS, CPT, GII, HPT, HT, HTN, MA, PLT, QRS, QTC, RD, SHS, VD | Yes | Yes | Antihypertensives, CPR, dexmedetomidine, intubation, IV fluid resuscitation, NaHCO3, naloxone/nalmefene, propofol, vasopressors (epinephrine) |

| 20 F | Cocaine, MDMA (methylenedioxy-N-methamphetamine, ecstasy) | CNS, CPT, HPT, HT, HYT, RBM, SS, TC | Yes | Yes | Benzodiazepines, continuous renal replacement therapy, cyproheptadine, ECMO, opioids, propofol, vasopressors (metaradrine, norepinephrine) |

| 37 M | Cocaine, methamphetamine | AGT, SYS, TC | No | Antipsychotics, benzodiazepines, IV fluid resuscitation, ketamine | |

| 47 M | Cocaine, methamphetamine | AKI, CNS, MI, QRS, RBM, VD | Yes | Yes | Benzodiazepines, IV fluid resuscitation, NAC |

| 42 M | Cocaine, snake unspecified | AK, AKI, CNS, CPT, HPT, HT, HTN, HYT, MA, MI, PLT, RBM, SYS, SZ, TC | Yes | No | Benzodiazepines, Fab antivenom, glucose > 5%, hemodialysis, intubation, IV fluid resuscitation, NMB, propofol, vasopressors (epinephrine, norepinephrine, phenylephrine, vasopressin) |

| 14 M | Dextromethorphan, diphenhydramine | RFX | Unknown | None | |

| 73 T | Digoxin, ethanol | AKI, BC, HT | Yes | Unknown | Folate, thiamine |

| 30 F | Fentanyl, methamphetamine | OT, RBM, RD, SYS | Yes | Yes | Intubation, IV fluid resuscitation, naloxone/nalmefene, opioids, propofol |

| 31 M | Fentanyl, methamphetamine | AG, AGT, AP, BLB, DLM, HPT, OT, RBM, SYS | Yes | Yes | None |

| 37 F | Fentanyl, oxycodone | CNS, HTN, OT, RBM, RD | Yes | Unknown | Intubation, IV fluid resuscitation |

| 17 F | Gabapentin, lamotrigine | BC, HT | No | Atropine, IV fluid resuscitation | |

| 10 F | Herbal (dietary) multibotanical, Soursop (Annona muricata, Graviola) | AG, AKI, AP, CNS, HT, MA, MI, OG, TC | Yes | Yes | CPR, intubation, IV fluid resuscitation, vasopressors (epinephrine, norepinephrine, vasopressin) |

| 30 M | Heroin, methadone | AG, BP, CA, CNS, HT, MA, MI, QTC, RD, SYL | Yes | Yes | Anticonvulsants, CPR, intubation, IV fluid resuscitation, naloxone/nalmefene, propofol, vasopressors (norepinephrine) |

| 71 M | Lorazepam, oxycodone | DLM, SHS, WBC | No | Antipsychotics, benzodiazepines, naloxone/nalmefene, nicotine replacement therapy |

a Based on response from Medical Toxicologist "Did the patient have a toxicological exposure?" equals Yes with known agent(s)

b Age in years unless otherwise stated

c AC: anticholinergic, AG: anion gap, AGT: agitation, AK: alcoholic ketoacidosis, AKI: acute kidney injury, ALI: acute lung injury/ARDS, AP: aspiration pneumonitis, BC: bradycardia, BL: blisters/bullae, BP: bradypnea, CA: cardiac arrest, CNS: coma/CNS depression, CPT: coagulopathy, DLM: delirium, GII: intestinal ischemia, HGY: hypoglycemia, HPT: hepatoxicity, HT: hypotension, HTN: hypertension, HYT: hyperthermia, MA: metabolic acidosis, MI: myocardial injury/ischemia, OG: osmolar gap, OT: opioid toxidrome, PLT: thrombocytopenia, QRS: QRS prolongation, QTC: QTc prolongation, RAD: asthma/reactive airway disease, RBM: rhabdomyolysis, RD: respiratory depression, RFX: hyperreflexia/clonus/tremor, SHS: sedative-hypnotic syndrome, SS: serotonin syndrome, SYL: sympatholytic syndrome, SYS: sympathomimetic syndrome, SZ: seizures, TC: tachycardia, VD: ventricular dysrhythmia, WBC: leukocytosis

d Pharmacological and Non-pharmacological support as reported by Medical Toxicologist; CPR: cardiopulmonary resuscitation, ECMO: extra-corporeal membrane oxygenation, HIE: high dose insulin euglycemic therapy, NAC: n-acetyl cysteine, NaHCO3: sodium bicarbonate, NMB: neuromuscular blockers

Table 33.

2022 Fatalities reported in ToxIC Core Registry with unknown toxicological exposurea.

| Age / Genderb | Clinical Findingsc | Life Support Withdrawn |

Brain Death Confirmed |

Treatment Reportedd |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 F | CNS, HPT, TC | Yes | No | None |

| 16 F | CNS, HT, RD | Yes | Yes | None |

| 26 M | None | Yes | Unknown | None |

| 29 M | CPT, DLM, EPS, HYT, PLT, RBM, RFX, SS, SYS, VD | No | Benzodiazepines, intubation, IV fluid resuscitation, NaHCO3, vasopressors (epinephrine, norepinephrine, vasopressin) | |

| 30 F | AG, AKI, ALI, CNS, HT, MA, PLT, QTC | Yes | No | Intubation, naloxone/nalmefene, vasopressors (epinephrine, norepinephrine) |

| 44 F | None | Unknown | None | |

| 44 M | RD | No | None | |

| 45 M | ALI, CNS, HT, HYT | Unknown | Benzodiazepines, ECMO, intubation, IV fluid resuscitation, ketamine, NMB, opioids, vasopressors (norepinephrine) | |

| 50 F | QTC | Yes | Unknown | Benzodiazepines, folate, IV fluid resuscitation, thiamine |

| 52 F | None | Yes | Yes | Benzodiazepines, buprenorphine/naloxone, IV fluid resuscitation, naloxone/nalmefene |

| 54 M | BC, CNS, HGY, RD | Unknown | Glucagon, intubation, IV fluid resuscitation | |

| 56 M | None | Unknown | None | |

| 57 M | AG, AKI, CNS, HT, MA, OG, RBM, RD | No | None | |

| 58 F | None | Unknown | None | |

| 58 M | AG, AKI, CNS, HPT, HT, MA | Yes | No | Fomepizole, intubation, IV fluid resuscitation, vasopressors (norepinephrine, vasopressin) |

| 60 F | None | No | None | |

| 60 M | AG, BC, CNS, HT, MA | Yes | Unknown | Intubation, IV fluid resuscitation, vasopressors (norepinephrine, vasopressin) |

| 61 M | None | Yes | Yes | None |

| 65 F | None | Yes | Unknown | None |

| 65 M | AG, CNS, HGY, HPT, HYT, MA, VD | No | None | |

| 66 M | None | Unknown | IV fluid resuscitation, thiamine | |

| 68 F | AG, AKI, CNS, HGY, HPT, HT, HYS, MA, PLT | Yes | No | Antiarrhythmics, benzodiazepines, continuous renal replacement therapy, glucose > 5%, intubation, IV fluid resuscitation, NAC, NaHCO3, opioids, transfusion, vasopressors (norepinephrine) |

| 69 F | None | Unknown | None | |

| 69 M | PLT, QTC | Unknown | Anticonvulsants, buprenorphine, buprenorphine/naloxone, clonidine, dexmedetomidine, folate, glucagon, IV fluid resuscitation, NaHCO3, naloxone/nalmefene | |

| 74 F | None | Unknown | None | |

| 77 F | AGT, AKI, RD | No | Continuous renal replacement therapy | |

| 80 M | NMS | Unknown | Intubation, IV fluid resuscitation | |

| 86 M | AG, AGT, RD, RFX | Unknown | None |

a Based on response from Medical Toxicologist "Did the patient have a toxicological exposure?" equals No or Unknown

b Age in years unless otherwise stated

c AG: anion gap, AGT: agitation, AKI: acute kidney injury, ALI: acute lung injury/ARDS, BC: bradycardia, CNS: coma/CNS depression, CPT: coagulopathy, DLM: delirium, EPS: extrapyramidal symptoms/dystonia/rigidity, HGY: hypoglycemia, HPT: hepatoxicity, HT: hypotension, HYS: hemolysis, HYT: hyperthermia, MA: metabolic acidosis, NMS: neuroleptic malignant syndrome, OG: osmolar gap, PLT: thrombocytopenia, QTC: QTc prolongation, RBM: rhabdomyolysis, RD: respiratory depression, RFX: hyperreflexia/clonus/tremor, SS: serotonin syndrome, SYS: sympathomimetic syndrome, TC: tachycardia, VD: ventricular dysrhythmia

d Pharmacological and Non-pharmacological support as reported by Medical Toxicologist; ECMO: extra-corporeal membrane oxygenation, NAC: n-acetyl cysteine, NaHCO3: sodium bicarbonate, NMB: neuromuscular blockers

Among the 90 fatalities with known agents, there were 17 (18.9%) involving opioids, with 10 (11.1%) single agent fatalities and 7 (7.8%) multiple agent fatalities. Acetaminophen was reported in 9 fatalities (10.0%)—of these, 5 (5.6%) cases were single-agent fatalities and 4 (4.4%) were multiple agent fatalities.

In 2022, there were 16 (13.6%) pediatric (age 0–17 years) deaths reported in the Core Registry. Eleven were single-agent exposures, 3 involved multiple agents, and 2 where the exposure agents were unknown. The most commonly implicated agent reported in these pediatric patients was diphenhydramine, associated with 18.8% of pediatric fatalities, with two of the cases reporting diphenhydramine as a single-agent exposure and one case reporting diphenhydramine and dextromethorphan as a multiple agent exposure.

Of note, two patients—one pediatric and one adult— died after exposure to a snakebite. One case reported a single agent exposure to a Crotalus (rattlesnake) and the second was a multiple agent exposure to an unknown type of snake and concomitant cocaine use.

Treatment

Antidotal Therapy