Abstract

Recent advances in lymphoma treatment have significantly improved the survival of patients; however, the current approaches also have varying side effects. To overcome these, it is critical to implement individualized treatment according to the patient’s condition. Therefore, the early identification of high-risk groups and targeted treatment are important strategies for prolonging the survival time and improving the quality of life of patients. Interim positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) has a high prognostic value, which can reflect chemosensitivity and identify patients for whom treatment may fail under this regimen. To date, many prospective clinical studies on interim PET (iPET)-adapted therapy have been conducted. In this review, we focus on the treatment strategies entailed in these studies, as well as the means and timing of iPET assessment, with the aim of exploring the efficacy and existing issues regarding iPET-adapted treatment. It is expected that the improved use of PET-CT examination can facilitate treatment decision-making to identify precise treatment options.

Keywords: Positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT), Lymphoma, Interim PET (iPET)-adapted therapy

Abstract

随着淋巴瘤治疗手段的发展与改进,患者的生存得到了极大的改善。然而,目前的治疗方法存在不同程度的副作用,因此需尽可能减少治疗带来的不良反应,并根据患者的情况实施个体化治疗。基于此,尽早识别高危人群并进行针对性治疗是延长患者生存时间和提高生活质量的重要策略。中期正电子发射计算机断层扫描(PET-CT)具有较高的预后价值,可以反映化疗敏感性并识别在该方案下治疗可能失败的患者。迄今为止,已经进行了多项关于中期PET(iPET)引导治疗的前瞻性临床研究。本综述重点关注上述研究中涉及的治疗策略以及iPET评估的方法和时间,通过探索iPET指导治疗的效果和存在的问题,以期iPET在治疗引导中能发挥更大的价值。

Keywords: 正电子发射计算机断层扫描(PET-CT), 淋巴瘤, 中期PET(iPET)引导的淋巴瘤治疗

1. Introduction

Lymphoma is a malignant tumor originating from the lymphohaemopoietic system, which can be divided into two types based on the tumor cells involved: non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) and Hodgkin’s lymphoma (HL) (Matasar and Zelenetz, 2008). Imaging examinations are commonly used for disease evaluation and may provide valuable information for formulating subsequent treatment strategies. Computed tomography (CT), as a traditional imaging method, is particularly valuable for providing a clear anatomical delineation of pathological lymph nodes and extranodal lesions. Positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT), which combines functional imaging by PET with morphological assessment by CT, is a standard technique for the diagnosis and treatment of many types of tumors, especially 18F-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose (FDG) uptake lymphomas. As a noninvasive, molecular-level functional imaging method, PET-CT plays an important role in the clinical staging and treatment response evaluation of lymphoma (Cheson, 2018; Barrington and Trotman, 2021; Zanoni et al., 2021). Several studies have also confirmed the high prognostic value of PET-CT examination after two to four cycles of chemotherapy (interim PET (iPET)), which can reflect chemosensitivity and identify patients for whom treatment may fail under this regimen (Gallamini et al., 2007; Fuertes et al., 2013; Mamot et al., 2015; Rigacci et al., 2015). Thus far, many prospective clinical studies on iPET-adapted therapy have been conducted. Based on their results, a relatively systematic first-line treatment strategy based on iPET has been established for patients with HL and also implemented into guidelines. However, in NHL, the role of iPET in guiding first-line treatment decision-making remains controversial. Therefore, in this review, we summarize previous iPET-adapted treatment regimens for lymphoma and provide a foundation for the clinical implementation of iPET-adapted first-line treatment strategies.

2. Hodgkin’s lymphoma

2.1. Early-stage Hodgkin’s lymphoma

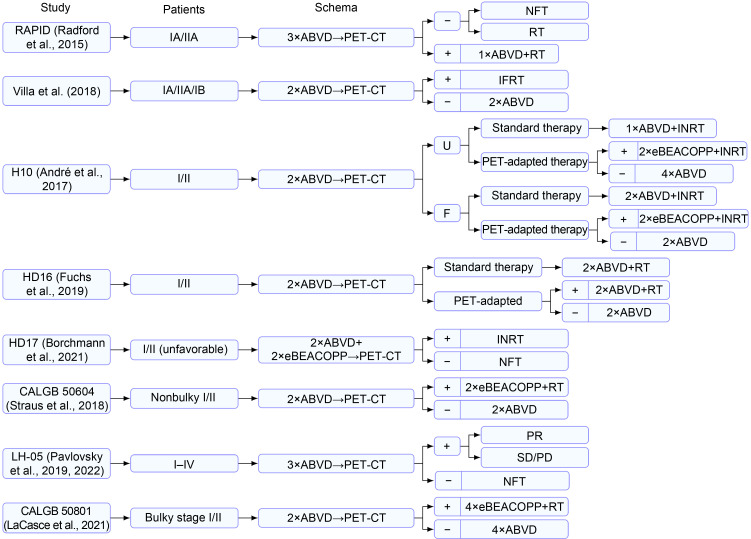

2.1.1. iPET-adapted omission of radiotherapy

For early-stage (Ann Arbor stage Ⅰ/Ⅱ) HL, the combination of chemotherapy and radiotherapy as a standard treatment has proved to achieve excellent results and a remission rate of more than 90% (Engert et al., 2010). However, radiation therapy may cause side effects such as secondary tumors, infertility, and cardiopulmonary damage (Matasar et al., 2015; Rigacci et al., 2015). Therefore, many prospective clinical studies have been conducted to determine whether radiotherapy can be omitted in patients with early-stage HL without affecting treatment efficacy. The details of these studies are summarized in Fig. 1 and Table 1. In the RAPID trial (Radford et al., 2015), iPET was performed after three cycles of chemotherapy with doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine (ABVD) in patients with early-stage HL, and iPET-negative patients (Deauville score≤2) were randomly assigned to radiotherapy and no-further-treatment groups. After a median follow-up of 60 months, the 3-year progression-free survival (PFS) rates for the two groups were 94.6% and 90.8%, respectively (P=0.16). Although no statistical significance was observed, the 3-year PFS difference was -3.8% (95% confidence interval (CI): -8.8%‒1.3%), and the lower limit of the 95% CI (-8.8%) exceeded the original noninferiority margin of -7.0%. The omission of radiotherapy in iPET-negative patients is thought to result in the shortening of PFS in some patients. Villa et al. (2018) demonstrated that the omission of radiotherapy resulted in a 5%–8% increase in the risk of recurrence. According to the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (Fermé et al., 2007), patients in the H10 study (André et al., 2017) were divided into an unfavorable cohort (U cohort) and a favorable cohort (F cohort). Then, the aforementioned cohorts were randomly divided into standard treatment group and iPET-adapted treatment group. In the latter, the iPET-negative patients received two cycles (F cohort) or four cycles (U cohort) of ABVD. The results indicated that the omission of radiotherapy increased the risk of recurrence in iPET-negative patients, especially those in the F cohort (5-year PFS: 87.1% vs. 99.0%). Similar results were obtained in the HD16 trial (Fuchs et al., 2019). The 5-year PFSs of iPET-negative patients with radiotherapy and those without radiotherapy were 93.4% and 86.1%, respectively (P=0.04).

Fig. 1. Therapies based on iPET in early-stage Hodgkin's lymphoma. PET-CT: positron emission tomography-computed tomography; iPET: interim PET; ABVD: doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine; NFT: no further treatment; RT: radiotherapy; IFRT: involved field radiation therapy; U: unfavorable cohort; F: favorable cohort; INRT: involved node radiation therapy; BEACOPP: bleomycin, etoposide, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, procarbazine, and prednisone; eBEACOPP: escalated BEACOPP; PR: partial response; SD: stable disease; PD: progression disease.

Table 1.

Therapies based on iPET in early-stage Hodgkin's lymphoma

| Study | Year | PET-CT criteria | Stage | Age (years) | Median follow-up time | n | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RAPID (Radford et al., 2015) | 2003‒2010 | Deauville score≤2 (negative) | IA/IIA | 16‒75 | 60 months | 571 |

PET-negative with IFRT: 3-year PFS 94.6%, 3-year OS 97.1%; PET-negative with NFT: 3-year PFS 90.8%, 3-year OS 99.0% |

| Villa et al. (2018) | 2005‒2016 | IHP/Deauville score | IA/IIA/IB | 16‒75 | 5.5 years | 239 |

Total: 5-year PFS 88.9%, 5-year OS 97.2%; Negative: 5-year PFS 89.5%, 5-year OS 97.3%; Positive: 5-year PFS 84.9%, 5-year OS 96.6% |

| H10 (André et al., 2017) | 2006‒2011 | IHP | I/II | 15‒70 | F: 5.0 years; U: 5.1 years | 1925 |

PET-positive, 5-year PFS 90.6%; PET-negative, 5-year PFS: U cohort with INRT 92.1%, U cohort without INRT 89.6%, F cohort with INRT 99.0%, F cohort without INRT 87.1% |

| HD16 (Fuchs et al., 2019) | 2009‒2015 | Deauville score≤2 (negative) | I/II | 18‒75 | 45 months | 1150 | PET-negative, 5-year PFS: with INRT 93.4%, without INRT 86.1% |

| HD17 (Borchmann et al., 2021) | 2012‒2017 | Deauville score≤2 (negative) | I/II (unfavorable) | 18‒60 | 46.2 months | 1100 |

Standard combined-modality treatment group: 5-year PFS 97.3%; PET4-guided treatment group: 5-year PFS 95.1% |

| CALGB 50604 (Straus et al., 2018) | 2010‒2013 | Deauville score≤3 (negative) | I/II (without tumor bulk) | 18‒58 | 3.8 years | 164 |

PET-negative: 3-year PFS 91%; PET-positive: 3-year PFS 66% |

| LH-05 (Pavlovsky et al., 2019, 2022) | 2005‒2015 | Deauville score≤2 (negative) | I‒IV | 18‒89 | 69 months | 377 |

Early-stage PET-negative: 3-year PFS 90%; Early-stage PET-positive: 3-year PFS 72%; Advanced-stage PET-negative: 3-year PFS 91%; Advanced-stage PET-positive: 3-year PFS 58% |

| CALGB 50801 (LaCasce et al., 2021) | 2010‒2017 | Deauville score≤3 (negative) | I/II (with bulk) | 18‒58 | 5.5 years | 101 |

PET-negative: 3-year PFS 93.1%; PET-positive: 3-year PFS 89.7%; All patients: 3-year PFS 92.3% |

PET-CT: positron emission tomography-computed tomography; iPET: interim PET; n: patients who completed iPET; IFRT: involved field radiation therapy; PFS: progression-free survival; OS: overall survival; NFT: no further treatment; IHP: International Harmonization Project; F: favorable cohort; U: unfavorable cohort; INRT: involved node radiation therapy.

The aforementioned four prospective clinical trials and a recent meta-analysis (Shaikh et al., 2020) suggested that in patients with early-stage HL, combined therapy is a standard regimen that improves PFS. Many hemato-oncologists considered that the majority of iPET-negative patients can achieve a favorable PFS without radiotherapy, and the failure rate may only be 0%–10% (Villa et al., 2018; Borchmann et al., 2021) while overall survival (OS) is not affected (Radford et al., 2015; Fiad et al., 2022). Several recent prospective randomized studies, including the HD17 (Borchmann et al., 2021), CALGB 50604 (Straus et al., 2018), and LH-05 trial (Pavlovsky et al., 2019, 2022), have confirmed that good outcomes can still be achieved when radiotherapy is omitted in iPET-negative patients. In fact, there are numerous ongoing prospective studies based on the results of iPET and aimed at exploring a new de-escalation therapy for patients with early-stage HL.

2.1.2. iPET-adapted intensive chemotherapy

Whether iPET-positive patients could benefit from more intensive chemotherapy remains unclear. In the H10 trial (André et al., 2017), iPET-positive patients were switched from ABVD to escalated BEACOPP (bleomycin, etoposide, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, procarbazine, and prednisone) (eBEACOPP) combined with involved node radiotherapy (INRT). The results indicated that the iPET-adapted treatment caused an increase in 5-year PFS from 77.4% to 90.6% (P=0.002) and also a significant increase in the 5-year OS (89.3% vs. 96.0%, P=0.062). This suggested that iPET-adapted intensive chemotherapy improves the prognosis of iPET-positive patients. However, the results of the subsequent CALGB 50801 study (LaCasce et al., 2021) indicated no benefit from iPET-adapted intensification therapy.

Based on the above results, the guidelines recommend adopting different treatment plans based on prognostic grouping under the guidance of iPET.

2.2. Advanced-stage Hodgkin’s lymphoma

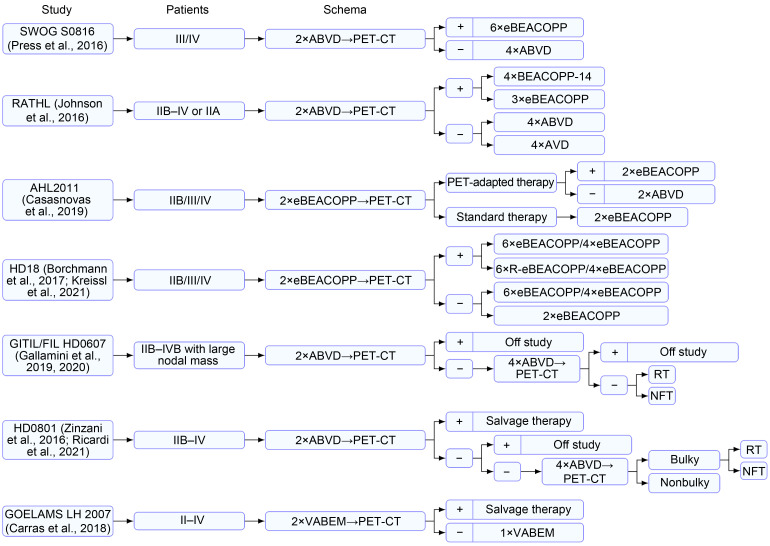

2.2.1. iPET-adapted chemotherapy

The treatment of advanced-stage (Ann Arbor stage Ⅲ/Ⅳ) HL by chemotherapy has resulted in high survival rates. About 60%–70% of patients can be cured by six to eight courses of ABVD (Viviani et al., 2011; Mounier et al., 2014). The eBEACOPP regimen has been shown to achieve higher PFS than ABVD (LaCasce et al., 2021). However, this escalated regimen may contribute to more toxicities, such as acute toxicity, secondary tumors, and infertility (Josting et al., 2003; Sieniawski et al., 2008; Borchmann et al., 2011; Behringer et al., 2013), particularly in younger patients. A number of prospective clinical studies have been conducted to explore the options for iPET-adapted chemotherapy for advanced-stage HL.

2.2.1.1. iPET-adapted escalated therapy

In the SWOG S0816 trial (Press et al., 2016), patients with advanced-stage HL underwent iPET examination after two courses of ABVD. The iPET-negative (Deauville score≤3) and iPET-positive patients received four courses of ABVD and six courses of eBEACOPP, respectively. The 5-year PFSs of the negative and positive patients were 76% and 66%, respectively. For all patients, the 5-year OS was 94%, which was a result beyond expectation (Press et al., 2016; Stephens et al., 2019). However, 25% of the iPET-negative patients relapsed, demonstrating the limitations of the ABVD regimen in advanced-stage HL. On the other hand, iPET-positive patients who received the eBEACOPP regimen had a significantly higher incidence of secondary tumors (14% vs. 2%, P=0.001). In the RATHL study (Johnson et al., 2016), the positive group received four courses of BEACOPP-14 or three courses of eBEACOPP after receiving two courses of ABVD. The overall 3-year PFS was 67.5%, which was significantly higher than that of patients with continued ABVD treatment. However, higher rates of thrombocytopenia and febrile neutropenia were observed for the eBEACOPP regimen. For advanced-stage patients initially treated with ABVD, the current results are controversial as to whether the original regimen should be maintained or the treatment should be upgraded based on the iPET results.

2.2.1.2. iPET-adapted de-escalation therapy

The iPET-adapted de-escalation therapy was investigated in the AHL2011 study (Casasnovas et al., 2019). Therein, a total of 823 patients with advanced-stage HL were divided into a standard treatment group (six courses of eBEACOPP) and an iPET-adapted treatment group. All patients underwent iPET examination after two cycles of eBEACOPP, and a Deauville score of ≤3 was judged as negative. The negative patients in the iPET-adapted treatment group were switched to the ABVD regimen, whereas the positive patients received two courses of the original regimen. The 5-year PFSs of the standard treatment and iPET-adapted groups were 86.2% and 85.7%, respectively (P=0.65). A subgroup analysis (Demeestere et al., 2021) revealed that in patients younger than 45 years of age, the de-escalation therapy reduced damage to fertility and improved treatment compliance. According to the HD18 trial (Borchmann et al., 2017), the eBEACOPP regimen can be reduced from six to eight courses to four courses for iPET-negative patients. This study found that the two cohorts (six to eight course or four courses) had similar 5-year PFS of 90.8% and 92.2%, respectively, and that four courses of eBEACOPP were associated with a lower incidence of severe infections and organ toxicities. Long-term follow-up also reconfirmed the efficacy and safety of iPET-adapted treatment in the HD18 trial (Kreissl et al., 2021). In addition, in the RATHL study (Johnson et al., 2016), the iPET-negative group was randomized to receive four courses of ABVD or AVD (bleomycin omitted), and the 3-year PFS was 85.7% or 84.4%, respectively, with an absolute difference of 1.6% (95% CI, -3.2%–5.3%). Furthermore, a significantly lower incidence of pulmonary toxic effect was observed in the AVD group (0.032% vs. 0.007%, P<0.05).

Recently, a cost-effective analysis of five previous regimens was conducted (Vijenthira et al., 2020). According to the Markov decision analysis model, for patients with advanced-stage HL, the AHL2011 regimen (after two cycles of eBEACOPP treatment, iPET-negative patients would be switched to two cycles of ABVD) was confirmed as the best strategy (Casasnovas et al., 2019). The most recent guidelines offered a comprehensive interpretation of treatment options for patients with advanced-stage HL and highlighted the significance of performing iPET after completing two courses of either eBEACOPP or ABVD (Follows et al., 2022). The selection between ABVD and eBEACOPP depends on a series of factors, particularly the individual risk status of the patient and their perception of the toxicity–efficacy balance between the regimens.

2.2.2. Effect of radiotherapy on improving the outcome in bulky advanced HL

Certain studies have explored the role of iPET-adapted radiotherapy in patients with advanced-stage HL (mass of ≥5 cm in diameter). In the GITIL/FIL HD0607 trial (Gallamini et al., 2019, 2020), 296 patients with advanced-stage HL who were PET-2 (PET-CT after two cycles of ABVD) and PET-6 (PET-CT after six cycles of ABVD)-negative and had large nodules were randomized to receive consolidation radiotherapy or no further treatment. The results indicated that there was no statistically significant difference in the 6-year PFS or OS between the groups. Similarly, the results of the FIL HD0801 study (Ricardi et al., 2021) indicated that in iPET-negative patients, consolidation radiotherapy had no significant effect on the outcome, even in patients with bulk lesions.

2.2.3. iPET-adapted autologous stem cell transplantation

It is not clear whether it is effective for patients with advanced-stage HL who responded poorly to first-line therapy to be switched to autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) as soon as possible. A prospective study (HD0801) (Zinzani et al., 2016; Ricardi et al., 2021) included 512 patients newly diagnosed with advanced-stage HL who received iPET after two cycles of ABVD. Juweid’s criteria (Juweid et al., 2007) were used to judge the iPET results. The iPET-positive patients received ASCT, whereas the iPET-negative patients continued with four courses of ABVD. The results indicated that early ASCT can achieve a similar 2-year PFS in positive patients as that in negative patients. In the GOELAMS LH 2007 study (Carras et al., 2018), salvage therapy was administered to positive patients after two cycles of VABEM (vindesine, doxorubicin, carmustine, etoposide, and methylprednisolone) treatment. Compared with negative patients who only received an additional cycle of VABEM, positive patients exhibited similar event-free survival and OS (85.1% vs. 77.8%, 91.7% vs. 88.2%), indicating that the iPET-adapted early ASCT is safe and feasible.

2.2.4. Others

Pembrolizumab is an immune checkpoint inhibitor generally used for the treatment of patients with relapsed or refractory HL. In recent years, pembrolizumab combined with an AVD regimen has been proven to be safe and effective for newly diagnosed HL (Allen et al., 2021). In an ongoing clinical trial (KEYNOTE-C11 (NCT05008224)), the efficacy of iPET-adapted treatment during first-line therapy is being investigated, and the results may provide new treatment options. This also suggests that with the application of new drugs, it is critical to further evaluate the iPET-adapted therapy to continue optimizing the treatment plan. The existing studies on iPET in advanced-stage HL are summarized in Fig. 2 and Table 2.

Fig. 2. Therapies based on iPET in advanced-stage Hodgkin's lymphoma. PET-CT: positron emission tomography-computed tomography; iPET: interim PET; ABVD: doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine; BEACOPP: bleomycin, etoposide, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, procarbazine, and prednisone; eBEACOPP: escalated BEACOPP; BEACOPP-14: an accelerated version of BEACOPP that involves growth-factor support; R-eBEACOPP: eBEACOPP combined with rituximab; AVD: doxorubicin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine; RT: radiotherapy; NFT: no further treatment; VABEM: vindesine, doxorubicin, carmustine, etoposide, and methylprednisolone.

Table 2.

Therapies based on iPET in advanced-stage Hodgkin's lymphoma

| Study | Year | PET-CT criteria | Stage | Age (years) | Median follow-up time | n | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SWOG S0816 (Press et al., 2016) | 2010‒2012 | Deauville score≤3 (negative) | III/IV | 18‒60 | 5.9 years | 331 |

2-year PFS: all patients 79%, PET-negative 82%, PET-positive 64%; 2-year OS: all patients 98%; 5-year PFS: all patients 74%, PET-negative 76%, PET-positive 66%; 5-year OS: all patients 94% |

| RATHL (Johnson et al., 2016) | 2008‒2012 | Deauville score≤3 (negative) | IIB–IV or IIA* | ≥18 | 41.2 months | 1119 | PET-negative: 3-year PFS: ABVD group 85.7%, AVD group 84.4%;3-year OS: ABVD group 97.2%, AVD group 97.6% |

| AHL2011 (Casasnovas et al., 2019) | 2011‒2014 | Deauville score≤3 (negative) | III/IV/IIB# | 16‒60 | 50.4 months | 823 | 5-year PFS: standard group 86.2%, PET-guided group 85.7% |

| HD18 (Borchmann et al., 2017; Kreissl et al., 2021) | 2008‒2014 | Deauville score≤2 (negative) | III/IV/IIB§ | 18‒60 | 73 months | 1964 | 5-year PFS:PET2-positive: 8×eBEACOPP 90.9%, 8×R-eBEACOPP 87.7%, 6×eBEACOPP 90.1%;PET2-negative: 6/8×eBEACOPP 91.2%, 4×eBEACOPP 93.0% |

| GITIL/FIL HD0607 (Gallamini et al.,2019, 2020) | 2008‒2014 | Deauville score≤3 (negative) | IIB–IVB with LNM | 18‒60 | 5.9 years | 296 |

LNM at baseline was 5‒7 cm, 6-year PFS: RT 91%, NFT 95% (P=0.62); LNM at baseline was 8‒10 cm, 6-year PFS: RT 98%, NFT 90% (P=0.24); LNM at baseline was >10 cm, 6-year PFS: RT 89%, NFT 86% (P=0.53) |

| HD0801 (Zinzani et al., 2016; Ricardi et al., 2021) | 2008‒2013 | Juweid's criteria | IIB–IV | 18‒68 | 27 months | 512 |

PET2-negative: 2-year PFS 81%; PET2-positive: 2-year PFS 76% |

| GOELAMS LH 2007 (Carras et al., 2018) | 2008‒2010 | Visual criteria | II–IV | 18‒65 | 5.3 years | 49 |

All patients: 5-year OS 85.3%, 5-year EFS 75.3%; PET2-negative: 5-year OS 88.2%, 5-year EFS 77.8%; PET2-positive: 5-year OS 91.7%, 5-year EFS 85.1% |

* IIA with adverse features: bulky disease (>33% of the transthoracic diameter or >10 cm elsewhere) or at least three involved sites; # IIB with a mediastinumto-thorax ratio of 0.33 or greater or extranodal localization; § Large mediastinal mass (not less than a third of the maximal thoracic diameter) or extranodal lesions. PET-CT: positron emission tomography-computed tomography; iPET: interim PET; n: patients who completed iPET; PFS: progression-free survival; OS: overall survival; ABVD: doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine; AVD: doxorubicin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine; BEACOPP: bleomycin, etoposide, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, procarbazine, and prednisone; eBEACOPP: escalated BEACOPP; R-eBEACOPP: eBEACOPP combined with rituximab; LNM: large nodal mass; RT: radiotherapy; NFT: no further treatment; EFS: event-free survival.

3. Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma

3.1. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma

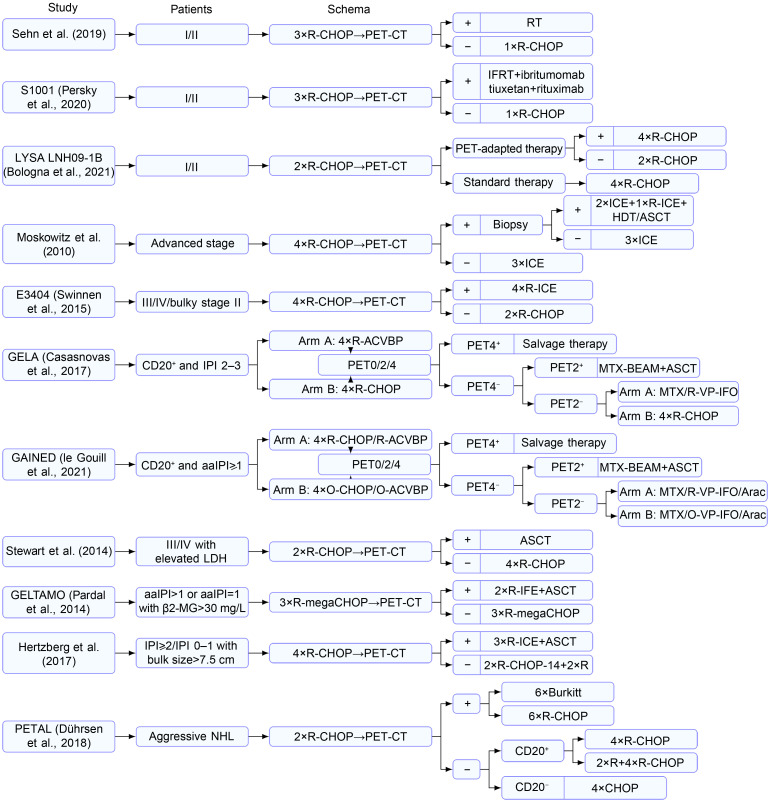

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common subtype of NHL. R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone) is a classic treatment regimen (Coiffier et al., 2002) that can clinically cure about 60% of patients; however, relapse is expected to occur in at least 30% of patients with DLBCL and primary drug resistance in 10% (Friedberg, 2011). Therefore, the early identification of these patients is important. Previous studies have focused on the prognostic role of iPET in DLBCL (Safar et al., 2012; Fuertes et al., 2013; Mamot et al., 2015). On the other hand, iPET-adapted therapy still needs further investigation.

3.1.1. iPET-adapted therapy in early DLBCL

For patients with early-stage (Ann Arbor stage Ⅰ/Ⅱ) DLBCL, three cycles of R-CHOP plus radiotherapy is a category 1 recommendation from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN). Nevertheless, a retrospective study found that only 8% of the iPET-negative patients experienced relapse after receiving an additional cycle of R-CHOP without radiotherapy, suggesting that four courses of R-CHOP are sufficient for early-stage iPET-negative patients (Sehn et al., 2019). Similarly, to minimize the unnecessary toxicities associated with radiotherapy for most patients, Persky et al. (2020) conducted the S1001 study in patients with early-stage DLBCL. After three courses of R-CHOP, iPET examination was performed. Involved field radiation therapy (IFRT) and another cycle of R-CHOP were administered to positive and negative patients (Deauville score≤2), respectively. The final results indicated that the 5-year PFS and OS of negative patients were 89% and 91%, which were 86% and 85% for positive patients, respectively. This trial established that four courses of R-CHOP alone could be used as a new standard approach for patients with limited-stage disease. Furthermore, in a prospective study, Bologna et al. (2021) investigated the difference between six and four courses of R-CHOP for iPET-positive and iPET-negative patients, respectively. The main endpoint was PFS, and after a median follow-up time of 5.1 years, the 3-year PFSs for the standard treatment and experimental groups were 89.2% and 92.0%, respectively. However, the authors pointed out the need for long-term follow-up to assess the risk of late recurrence.

3.1.2. iPET-adapted therapy in advanced DLBCL

For advanced-stage (Ann Arbor stage III/IV) and high-risk (age-adjusted international prognostic index (aaIPI) score of ≥2 points) patients, iPET-adapted therapy has also been investigated, while the results remain controversial.

As early as in 2002, Moskowitz et al. (2010) enrolled 97 patients to evaluate the prognostic value and treatment guidance of iPET in patients with advanced-stage DLBCL. iPET was performed after four courses of R-CHOP, and iPET-positive patients underwent biopsy. Those with a negative biopsy result received the same treatment as the iPET-negative patients: three courses of ICE (ifosfamide, carboplatin, and etoposide). For positive patients confirmed by biopsy, additional ASCT was performed. A total of 38 patients were iPET-positive, 5 of whom were confirmed positive after biopsy. After a median follow-up of 44 months, no statistically significant difference was observed in the PFS between iPET-negative and iPET-positive but biopsy-negative patients (P=0.27). This result suggested the presence of false-positive iPET associated with rituximab treatment where biopsy is necessary, which is the very concern that warrants attention in the current era of rituximab. In the E3404 study (Swinnen et al., 2015), four cycles of R-CHOP were initially administered for advanced-stage DLBCL, with an iPET scan scheduled after three cycles of R-CHOP. The iPET-positive patients received four cycles of R-ICE (rituximab, ICE), whereas the iPET-negative patients continued with two cycles of R-CHOP. The results indicated that the 2-year PFS of positive patients was only 42%, which was lower than the target value (45%). The authors believed that iPET-adapted treatment continues to face several unresolved issues, particularly in determining the management strategy for iPET-positive patients. However, there were only 13 iPET-positive patients in their study, which limits its reliability due to the small sample size.

In the GELA study (Casasnovas et al., 2017), 160 high-risk DLBCL patients (aaIPI score≥2 points) were randomly appointed to two groups to receive R-CHOP-14 or R-ACVBP (rituximab, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vindesine, bleomycin, and prednisone). PET-CT examination was performed before chemotherapy and after two cycles (PET2) and four cycles (PET4) of chemotherapy, and the results were judged based on the International Harmonization Project (IHP) standard (Juweid et al., 2007). PET2+/PET4- patients received ASCT, PET2-/PET4- patients continued with consolidation chemotherapy, and for PET4+ patients, salvage therapy depended on the local investigators’ decision. The results indicated no statistical significance in the 4-year PFS between double-negative patients and PET2+/PET4- patients (75% vs. 85%, P=0.28). The authors believed that a high-risk population cannot be recognized by interpreting the PET2 results based on the IHP standard. In the GAINED experiment (le Gouill et al., 2021), PET-CT was also performed before the chemotherapy (PET0), after two (PET2) and four (PET4) cycles of chemotherapy. Different from GELA, a negative PET-CT result was defined as a decline in the maximum standardized uptake value (ΔSUVmax) of >66% with PET2, and ΔSUVmax of >70% was considered negative with PET4 (Lin et al., 2007). Therein, patients were randomized to receive rituximab or obinutuzumab, whereas the choice between ACVBP and CHOP depended on each center. Similar to the GELA study, after four courses of induction therapy, the consolidation therapy was tailored to the results of PET2 and PET4. They found that a positive PET2 result was not correlated with an inferior outcome when PET4 was negative, whereas a positive PET4 result was associated with an elevated risk of relapse, progression, or death. In addition, the 2-year PFS and 4-year PFS of all patients were 83.1% and 78.1%, respectively, which is a more satisfying result than those in the previously published ones for young patients with aaIPI≥1 point. The authors also asserted that iPET-adapted therapy could be considered for use in routine practice for patients with advanced-stage DLBCL.

Based on the above research data, there are still many issues that need to be resolved regarding iPET-adapted treatment in patients with advanced-stage DLBCL, particularly with regard to the timing and method of assessment. In the GELA and GAINED studies, the therapeutic guidance significance of PET-CT scans after two cycles was limited, regardless of whether they were evaluated using the IHP criteria or ΔSUVmax. Furthermore, according to Casasnovas et al. (2017), ΔSUVmax for iPET assessment proved to be more powerful than the Deauville score, IHP criteria, and visual assessment. However, additional studies are warranted to corroborate these matters.

3.1.3. iPET-adapted early ASCT

Early identification of high-risk patients who may fail R-CHOP treatment and prompt the initiation of salvage treatment is a crucial component of effective treatment. Stewart et al. (2014) aimed to explore the clinical significance of ASCT based on iPET results in high-risk patients (international prognostic index (IPI) 3–5, or with stage III/IV and elevated lactate dehydrogenase (LDH)). A total of 70 patients underwent iPET examination after two cycles of R-CHOP. The iPET scans were considered positive for showing an unfavorable response if the uptake was greater than the background liver at more than one site. For iPET-positive patients, ASCT was performed after one cycle of R-DICEP (rituximab, dose-intensive cyclophosphamide, etoposide, cisplatin), whereas iPET-negative patients continued treatment with four cycles of R-CHOP. After a median follow-up of 41 months, the 3-year PFSs of positive and negative patients were 65.2% and 52.7%, respectively. Furthermore, the 3-year PFS of the overall population was 59.3%, which was not significantly different from non-iPET-adapted treatment. In the GELTAMO trial (Pardal et al., 2014), for newly diagnosed high-risk DLBCL patients, the iPET results were evaluated according to the IHP criteria (Juweid et al., 2007), and the initial treatment consisted of three courses of R-megaCHOP (rituximab 375 mg/m2 on Day 1, cyclophosphamide 1500 mg/m2 on Day 1, doxorubicin 65 mg/m2 on Day 1, vincristine 1.4 mg/m2 on Day 1, and prednisone 60 mg/m2 on Days 1–5). Negative patients continued to receive three courses of the original regimen, whereas positive patients were administered two cycles of R-IFE (rituximab, ifosfamide, and etoposide) and then ASCT. Nevertheless, the positive patients who received early ASCT still experienced a significantly inferior outcome than negative patients (3-year PFS: 57% vs. 81%, P=0.023). However, in another prospective study (Hertzberg et al., 2017), 143 high-risk DLBCL patients (either IPI 2‒5 or 0‒1 with bulk size of >7.5 cm) underwent iPET scans after four cycles of R-CHOP-14. Positive patients (without progression) received three cycles of R-ICE followed by ASCT, whereas negative patients continued to receive two cycles of R-CHOP-14, followed by two doses of rituximab once a week. Positive patients exhibited favorable survival similar to negative patients (2-year PFS: 67% vs. 74%, P=0.11).

In the three aforementioned studies, iPET scans were performed after the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th treatment courses, with positivity rates of 51%, 42%, and 29%, respectively. The research by Stewart et al. (2014) used visual evaluation, whereas the other two studies employed the IHP standard to evaluate iPET. Thus, different iPET detection timing and interpretation methods may yield different results.

3.2. iPET-adapted therapy in other forms of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma

The currently available iPET-adapted treatments are not limited to DLBCL. As such, the PETAL study (Dührsen et al., 2018) on newly diagnosed aggressive NHL was conducted to determine whether iPET can guide therapy. In addition to DLBCL, T-cell lymphoma (n=76), primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma (n=42), and follicular lymphoma (FL) grade 3 (n=42) were included. The initial treatment included two courses of R-CHOP (rituximab was restricted to CD20-positive lymphomas), followed by iPET examination, and the results were judged using ΔSUVmax (Lin et al., 2007). iPET-positive patients were randomized to receive six courses of R-CHOP or six courses of Burkitt regimen, whereas iPET-negative patients were administered four courses of R-CHOP or four courses of R-CHOP plus two doses of rituximab. The results indicated that an additional two courses of rituximab in iPET-negative patients did not provide benefits and that the switch from R-CHOP to Burkitt regimen in iPET-positive patients did not improve the treatment efficacy but increased the treatment-related toxicities. Furthermore, an ongoing phase III prospective clinical trial (IELSG-37; www.clinicaltrials.gov, #NCT01599559) investigated whether radiotherapy can be omitted in primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma (PMBCL). In another ongoing prospective clinical trial (www.clinicaltrials.gov, #NCT04745949) on PMBCL, iPET was administered after two courses of A-O (brentuximab vedotin and nivolumab) and two cycles of A-O-R-CHP (brentuximab vedotin, nivolumab, rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and prednisone) as initial treatment. Negative patients received two courses of A-O-R-CHP and another two courses of A-O, whereas positive patients received four courses of A-O-R-CHP. The above prospective study results are expected to provide more treatment options. In addition, the prognostic value of iPET has been confirmed in patients with FL (Luminari et al., 2014) and peripheral T-cell lymphoma (Mehta-Shah et al., 2019), while treatment adjustment based on iPET still needs to be validated by prospective studies. The details of studies on NHL are presented in Fig. 3 and Table 3.

Fig. 3. Therapies based on iPET in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (NHL). PET-CT: positron emission tomography-computed tomography; iPET: interim PET; CHOP: cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone; R: rituximab; O: opdivo; IFRT: involved field radiation therapy; ICE: ifosfamide, carboplatin, and etoposide; HDT: high-dose therapy; ASCT: autologous stem cell transplantation; CD20+: cluster of differentiation 20-positive; IPI: international prognostic index; aaIPI: age-adjusted IPI; ACVBP: doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vindesine, bleomycin, and prednisone; MTX: methotrexate; BEAM: carmustine, etoposide, cytarabine, and melphalan; VP: etoposide; IFO: ifosfamide; Arac: cytarabine; LDH: lactate dehydrogenase; β2-MG: β2-microglobulin; IFE: ifosfamide and etoposide; R-megaCHOP: rituximab 375 mg/m2 on Day 1, cyclophosphamide 1500 mg/m2 on Day 1, doxorubicin 65 mg/m2 on Day 1, vincristine 1.4 mg/m2 on Day 1, and prednisone 60 mg/m2 on Days 1–5; RT: radiotherapy; Burkitt: the Burkitt protocol consisting of high-dose methotrexate, cytarabine, hyperfractionated cyclophosphamide and ifosfamide, split-dose doxorubicin and etoposide, vincristine, vindesine, and dexamethasone.

Table 3.

Therapies based on iPET in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma

| Study | Year | PET-CT criteria | Stage | Age (years) | Median follow-up | n | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sehn et al. (2019) | 2005‒2019 | IHP (before 2014), Deauville score≤2 (after 2014, negative) | Stage I/II, no B-symptoms, mass size<10 cm | 19‒92 | 6.25 years | 319 |

5-year PFS: PET-positive 74%, PET-negative 88%; 5-year OS: PET-positive 77%, PET-negative 90% |

| S1001 (Persky et al., 2020) | 2011‒2016 | Deauville score≤2 (negative) | Nonbulky (<10 cm) stage I/II CD20+ | 18‒86 | 4.92 years | 128 |

5-year PFS: PET-positive 86%, PET-negative 89%; 5-year OS: PET-positive 85%, PET-negative 91% |

| LYSA LNH09-1B (Bologna et al., 2021) | 2010‒2017 | Deauville score≤3 (negative) | Stage I/II | 18‒80 | 5.1 years | 650 |

Standard arm: 3-year PFS 89.2%; Experimental arm: 3-year PFS 92.0% |

| Moskowitz et al. (2010) | 2002‒2006 | Visual criteria | Advanced stage | 20‒65 | 44 months | 97 | PFS: PET-positive, biopsy-negative vs. PET-negative (P=0.27) |

| E3404 (Swinnen et al., 2015) | 2006‒2009 | EOCG criteria | III/IV or bulky stage II | 20‒74 | 4.6 years | 76 |

2-year PFS: PET-positive 42%, PET-negative 76%; 3-year OS: PET-positive 69%, PET-negative 93% |

| GELA (Casasnovaset al., 2017) | 2007‒2010 | IHP | CD20+ and IPI 2–3 | 18‒59 | 45 months | 211 |

4-year PFS: 75% vs. 85% (P=0.28); 4-year OS: 89.6 vs. 90.4% (P=0.21) |

| GAINED (le Gouill et al., 2021) | 2012‒2015 | ΔSUVmax | CD20+ and aaIPI 1‒3 | 18‒61 | 38.9 months | 670 |

2-year PFS: 83.1%; 4-year PFS: 78.1% |

| Stewart et al. (2014) | 2007‒2011 | Visual criteria | Advanced stage and elevated LDH | 19‒65 | 41 months | 70 |

3-year PFS: PET-positive 65.2%, PET-negative 52.7%, all patients 59.3%; 3-year OS: PET-positive 68.4%, PET-negative 70.5%, all patients 69.8% |

| GELTAMO (Pardal et al., 2014) | 2007‒2009 | IHP | aaIPI>1 or aaIPI=1 with β2-MG>30 mg/L | 18‒70 | 42.8 months | 66 |

4-year PFS: 67%; 4-year OS: 78%; 3-year PFS: 81%; 3-year OS: 89% |

| Hertzberg et al. (2017) | 2009‒2012 | IHP | Either IPI 2‒5 or 0‒1 with bulk size>7.5 cm | 18‒70 | 35 months | 143 |

2-year PFS: PET-positive 67%, PET-negative 74%; 2-year OS: PET-positive 78%, PET-negative 88% |

| PETAL (Dührsen et al., 2018) | 2007‒2012 | ΔSUVmax | Aggressive NHL | 18‒80 |

44.1 months (positive); 54.1 months (negative) |

862 | 2-year EFS: PET-positive/R-CHOP 42.0%, PET-positive/Burrkitt 31.6%, PET-negative/R-CHOP 76.4%, PET-negative/R-CHOP+R 73.5% |

PET-CT: positron emission tomography-computed tomography; iPET: interim PET; n: patients who completed iPET; IHP: International Harmonization Project; PFS: progression-free survival; OS: overall survival; CD20+: cluster of differentiation 20-positive; EOCG criteria: based on modifications of the International Harmonization Project (Juweid et al., 2007), customized for ECOG E3404 interim scans and deemed the "ECOG criteria"; IPI: international prognostic index; aaIPI: age-adjusted IPI; ΔSUVmax: a decline in the maximum standardized uptake value; LDH: lactate dehydrogenase; β2-MG: β2-microglobulin; NHL: non-Hodgkin's lymphoma; EFS: event-free survival; CHOP: cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone; Burkitt protocol: the Burkitt protocol consists of high-dose methotrexate, cytarabine, hyperfractionated cyclophosphamide and ifosfamide, split-dose doxorubicin and etoposide, vincristine, vindesine, and dexamethasone; R: rituximab.

4. Existing challenges

Compared with HL, treatments for NHL are still in the exploratory phase. The rationale of success is highly intricate due to the involvement of several factors. First, the pathophysiology of NHL is different from that of HL; for example, its subtype classification is more complex, there is still significant heterogeneity within the same subtype of NHL, and tumor cell proliferation is more rapid and often presents with leapfrog metastasis. All of these factors considerably weaken the clinical significance of iPET.

Second, because PET-CT reflects the level of metabolism, the problem of false positives should also be considered. In the study by Moskowitz et al. (2010), some iPET-positive patients underwent biopsy, indicating that there was only a certain degree of inflammation and apoptosis in their lesions. This phenomenon was partly due to the application of rituximab and many other new targeted drugs. These can kill tumor cells, activate the patient’s lymphocytes and aggregates around the tumor, produce a large number of cytokines that cause local inflammatory reactions, induce hypermetabolism at the lesion site (tumor flare reaction), and thus cause the unclear demarcation of tumor tissue, resulting in a diminished positive predictive value. It was reported that in patients with HL who were treated with brentuximab vedotin, pathological examination confirmed the occurrence of flare at the tumor site (Zhu et al., 2021). Many studies have also confirmed that the application of rituximab weakened the positive predictive value of iPET (Han et al., 2009; Cashen et al., 2011; Pregno et al., 2012), but its negative predictive value has been affirmed (Dupuis et al., 2009; Cashen et al., 2011). In addition to the abovementioned use of rituximab, other immunotherapies and chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR-T) therapy applications may impact the interpretation of iPET results. CAR-T has exhibited excellent efficacy in patients who had relapse or refractory DLBCL. Furthermore, several studies have investigated the role of PET-CT in CAR-T therapy (Shah et al., 2018; Imber et al., 2020; Derlin et al., 2021; Cohen et al., 2022). For instance, a case report described a flare phenomenon following CAR-T therapy and suggested that early PET-CT scans may have affected the interpretation of the results (Boursier et al., 2022). Therefore, with the development and application of new treatment methods, caution should be exercised when considering the value of PET-CT for therapy.

Previous prospective studies of treatment adjustment based on iPET have also exhibited great heterogeneity. In many of these studies, the timing of iPET was different, particularly in the application of immune and targeted biological agents; thus, the selection of iPET inspection nodes is important. Eertink et al. (2021) found that in patients with DLBCL, PET-CT examination after two cycles of chemotherapy could predict better curative effect response, whereas after four cycles, it could better screen out people who were not sensitive to treatment. This allowed for potential treatment de-escalation after two cycles or treatment escalation after four cycles. However, further research is warranted to confirm this conclusion.

Moreover, the evaluation method for PET-CT will also have a great impact on the results. Standardized and consistent criteria for the interpretation of iPET results are helpful for the development of clinical research and application of iPET. In previous studies, the evaluation methods mainly used the IHP criteria, Deauville score, ΔSUVmax, and total metabolic tumor volume (MTV), and the cut-off criteria were different. In the E3404 trial (Swinnen et al., 2015), the investigators reassessed the iPET-positive patients’ images and the positive rates were increased from 16% to 34%. The iPET results of the GELA study (Casasnovas et al., 2017) were reviewed by the later research team using ΔSUVmax, and the double-negative rate increased from 24% to 79%, suggesting that ΔSUVmax was more helpful in guiding treatment for DLBCL. Similarly, in the GELTAMO experiment (Pardal et al., 2014), a retrospective evaluation revealed that 17 patients judged to be positive were identified as PET-negative in the semiquantitative assessment (ΔSUVmax) method. Other iPET assessment modalities, such as MTV and total glycolytic index, have also been shown to be independent prognostic factors, and more precise PET-CT assessment modalities are expected to provide more robust evidence for iPET-based treatment guidance (Zasadny et al., 1998; Larson et al., 1999; Cottereau et al., 2018; Toledano et al., 2018).

5. Conclusions and prospects

The application and development of iPET will likely yield more ideas for clinical decision-making. Advances in artificial intelligence, deep learning, and neural networks have also provided us with a new strategy to standardize the evaluation of patient imaging data and reduce heterogeneity (Berthon et al., 2016; Barrington and Meignan, 2019). Furthermore, a prognostic model based on PET-CT combined with other indicators, such as circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA), is an additional strategy to identify high-risk patients with aggressive lymphoma and potentially facilitate the development of treatment strategies (Kurtz et al., 2018). In recent years, the development of immuno-PET has also increased options for clinical decision-making. As a novel molecular imaging technology, it can specifically bind to tumor cells and achieve accurate lesion assessment using monoclonal antibody-labeled radionuclides (Knowles and Wu, 2012; Bailly et al., 2017). This approach may, to a certain extent, overcome the problem of false positive iPET in the era of immune-targeted therapy (Ferrari et al., 2021). Although iPET-adapted treatment is still burdened with many controversies, by optimizing the treatment process, standardizing the evaluation method, and combining other prognostic indicators and even the application and development of immuno-PET, this imaging examination method that reflects the level of cell metabolism will have a broad space for development in the evaluation and treatment of diseases.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82270206) and the Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (No. LZ22H160009).

Author contributions

Writing – original draft preparation: Linlin HUANG; Writing – review and editing: Linlin HUANG, Yi ZHAO, and Jingsong HE; Supervision: Yi ZHAO and Jingsong HE; Funding acquisition: Jingsong HE. All authors have read and agreed the final version of the manuscript.

Compliance with ethics guidelines

Linlin HUANG, Yi ZHAO, and Jingsong HE declare that they have no conflict of interest.

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

References

- Allen PB, Savas H, Evens AM, et al. , 2021. Pembrolizumab followed by AVD in untreated early unfavorable and advanced-stage classical Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood, 137(10): 1318-1326. 10.1182/blood.2020007400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- André MPE, Girinsky T, Federico M, et al. , 2017. Early positron emission tomography response-adapted treatment in stage I and II Hodgkin lymphoma: final results of the randomized EORTC/LYSA/FIL H10 trial. J Clin Oncol, 35(16): 1786-1794. 10.1200/JCO.2016.68.6394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailly C, Cléry PF, Faivre-Chauvet A, et al. , 2017. Immuno-PET for clinical theranostic approaches. Int J Mol Sci, 18(1): 57. 10.3390/ijms18010057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrington SF, Meignan M, 2019. Time to prepare for risk adaptation in lymphoma by standardizing measurement of metabolic tumor burden. J Nucl Med, 60(8): 1096-1102. 10.2967/jnumed.119.227249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrington SF, Trotman J, 2021. The role of PET in the first-line treatment of the most common subtypes of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Lancet Haematol, 8(1): e80-e93. 10.1016/S2352-3026(20)30365-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behringer K, Mueller H, Goergen H, et al. , 2013. Gonadal function and fertility in survivors after Hodgkin lymphoma treatment within the German Hodgkin study group HD13 to HD15 trials. J Clin Oncol, 31(2): 231-239. 10.1200/JCO.2012.44.3721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berthon B, Marshall C, Evans M, et al. , 2016. ATLAAS: an automatic decision tree-based learning algorithm for advanced image segmentation in positron emission tomography. Phys Med Biol, 61(13): 4855-4869. 10.1088/0031-9155/61/13/4855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bologna S, Vander Borght T, Briere J, et al. , 2021. Early positron emission tomography response-adapted treatment in localized diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (aaIPI=0): results of the phase 3 LYSA LNH 09-1B trial. Hematol Oncol, 39(S2): 31-32. 10.1002/hon.5_287934105823 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Borchmann P, Haverkamp H, Diehl V, et al. , 2011. Eight cycles of escalated-dose BEACOPP compared with four cycles of escalated-dose BEACOPP followed by four cycles of baseline-dose BEACOPP with or without radiotherapy in patients with advanced-stage Hodgkin’s lymphoma: final analysis of the HD12 trial of the German Hodgkin Study Group. J Clin Oncol, 29(32): 4234-4242. 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.9549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borchmann P, Goergen H, Kobe C, et al. , 2017. PET-guided treatment in patients with advanced-stage Hodgkin’s lymphoma (HD18): final results of an open-label, international, randomised phase 3 trial by the German Hodgkin Study Group. Lancet, 390(10114): 2790-2802. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32134-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borchmann P, Plütschow A, Kobe C, et al. , 2021. PET-guided omission of radiotherapy in early-stage unfavourable Hodgkin lymphoma (GHSG HD17): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol, 22(2): 223-234. 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30601-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boursier C, Perrin M, Bordonne M, et al. , 2022. Early 18F-FDG PET flare-up phenomenon after CAR T-cell therapy in lymphoma. Clin Nucl Med, 47(2): e152-e153. 10.1097/RLU.0000000000003870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carras S, Dubois B, Senecal D, et al. , 2018. Interim PET response-adapted strategy in untreated advanced stage Hodgkin lymphoma: results of GOELAMS LH 2007 phase 2 multicentric trial. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk, 18(3): 191-198. 10.1016/j.clml.2018.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casasnovas RO, Ysebaert L, Thieblemont C, et al. , 2017. FDG-PET-driven consolidation strategy in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: final results of a randomized phase 2 study. Blood, 130(11): 1315-1326. 10.1182/blood-2017-02-766691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casasnovas RO, Bouabdallah R, Brice P, et al. , 2019. PET-adapted treatment for newly diagnosed advanced Hodgkin lymphoma (AHL2011): a randomised, multicentre, non-inferiority, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol, 20(2): 202-215. 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30784-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cashen AF, Dehdashti F, Luo JQ, et al. , 2011. 18F-FDG PET/CT for early response assessment in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: poor predictive value of international harmonization project interpretation. J Nucl Med, 52(3): 386-392. 10.2967/jnumed.110.082586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheson BD, 2018. PET/CT in lymphoma: current overview and future directions. Semin Nucl Med, 48(1): 76-81. 10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2017.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen D, Luttwak E, Beyar-Katz, O, et al. , 2022. [18F]FDG PET-CT in patients with DLBCL treated with CAR-T cell therapy: a practical approach of reporting pre- and post-treatment studies. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging, 49(3): 953-962. 10.1007/s00259-021-05551-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coiffier B, Lepage E, Brière J, et al. , 2002. CHOP chemotherapy plus rituximab compared with CHOP alone in elderly patients with diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med, 346(4): 235-242. 10.1056/NEJMoa011795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cottereau AS, Versari A, Loft A, et al. , 2018. Prognostic value of baseline metabolic tumor volume in early-stage Hodgkin lymphoma in the standard arm of the H10 trial. Blood, 131(13): 1456-1463. 10.1182/blood-2017-07-795476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demeestere I, Racape J, Dechene J, et al. , 2021. Gonadal function recovery in patients with advanced Hodgkin lymphoma treated with a PET-adapted regimen: prospective analysis of a randomized phase III trial (AHL2011). J Clin Oncol, 39(29): 3251-3260. 10.1200/JCO.21.00068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derlin T, Schultze-Florey C, Werner RA, et al. , 2021. 18F-FDG PET/CT of off-target lymphoid organs in CD19-targeting chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy for relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Ann Nucl Med, 35(1): 132-138. 10.1007/s12149-020-01544-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dührsen U, Müller S, Hertenstein B, et al. , 2018. Positron emission tomography-guided therapy of aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphomas (PETAL): a multicenter, randomized phase III trial. J Clin Oncol, 36(20): 2024-2034. 10.1200/JCO.2017.76.8093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupuis J, Itti E, Rahmouni A, et al. , 2009. Response assessment after an inductive CHOP or CHOP-like regimen with or without rituximab in 103 patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: integrating 18fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography to the International Workshop Criteria. Ann Oncol, 20(3): 503-507. 10.1093/annonc/mdn671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eertink JJ, Burggraaff CN, Heymans MW, et al. , 2021. Optimal timing and criteria of interim PET in DLBCL: a comparative study of 1692 patients. Blood Adv, 5(9): 2375-2384. 10.1182/bloodadvances.2021004467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engert A, Plütschow A, Eich HT, et al. , 2010. Reduced treatment intensity in patients with early-stage Hodgkin’s lymphoma. N Engl J Med, 363(7): 640-652. 10.1056/NEJMoa1000067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fermé C, Eghbali H, Meerwaldt JH, et al. , 2007. Chemotherapy plus involved-field radiation in early-stage Hodgkin’s disease. N Engl J Med, 357(19): 1916-1927. 10.1056/NEJMoa064601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari C, Maggialetti N, Masi T, et al. , 2021. Early evaluation of immunotherapy response in lymphoma patients by 18F-FDG PET/CT: a literature overview. J Pers Med, 11(3): 217. 10.3390/jpm11030217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiad NL, Prates MV, Fernandez I, et al. , 2022. P1082: safety and efficacy analysis in older patients treated within the GATLA LH-05 protocol: PET-adapted therapy after 3 cycles of ABVD for all stages of Hodgkin lymphoma. HemaSphere, 6: 972-973. 10.1097/01.HS9.0000847196.45811.7e [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Follows GA, Barrington SF, Bhuller KS, et al. , 2022. Guideline for the first-line management of Classical Hodgkin Lymphoma—a British Society for Haematology guideline. Br J Haematol, 197(5): 558-572. 10.1111/bjh.18083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedberg JW, 2011. Relapsed/refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Hematol Am Soc Hematol Educ Program, 2011(1): 498-505. 10.1182/asheducation-2011.1.498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs M, Goergen H, Kobe C, et al. , 2019. Positron emission tomography-guided treatment in early-stage favorable Hodgkin lymphoma: final results of the international, randomized phase III HD16 trial by the German Hodgkin Study Group. J Clin Oncol, 37(31): 2835-2845. 10.1200/JCO.19.00964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuertes S, Setoain X, Lopez-Guillermo A, et al. , 2013. Interim FDG PET/CT as a prognostic factor in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging, 40(4): 496-504. 10.1007/s00259-012-2320-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallamini A, Hutchings M, Rigacci L, et al. , 2007. Early interim 2-[18F]fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography is prognostically superior to international prognostic score in advanced-stage Hodgkin’s lymphoma: a report from a joint Italian-Danish study. J Clin Oncol, 25(24): 3746-3752. 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.6525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallamini A, Rossi A, Patti C, et al. , 2019. Consolidation radiotherapy could be omitted in advanced Hodgkin lymphoma with large nodal mass in complete metabolic response after ABVD. Final analysis of the randomized HD0607 trial. Hematol Oncol, 37(S2): 147-148. 10.1002/hon.105_2629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallamini A, Rossi A, Patti C, et al. , 2020. Consolidation radiotherapy could be safely omitted in advanced Hodgkin lymphoma with large nodal mass in complete metabolic response after ABVD: final analysis of the randomized GITIL/FIL HD0607 trial. J Clin Oncol, 38(33): 3905-3913. 10.1200/JCO.20.00935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han HS, Escalón MP, Hsiao B, et al. , 2009. High incidence of false-positive PET scans in patients with aggressive non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma treated with rituximab-containing regimens. Ann Oncol, 20(2): 309-318. 10.1093/annonc/mdn629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertzberg M, Gandhi MK, Trotman J, et al. , 2017. Early treatment intensification with R-ICE and 90Y-ibritumomab tiuxetan (Zevalin)-BEAM stem cell transplantation in patients with high-risk diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patients and positive interim PET after 4 cycles of R-CHOP-14. Haematologica, 102(2): 356-363. 10.3324/haematol.2016.154039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imber BS, Sadelain M, DeSelm C, et al. , 2020. Early experience using salvage radiotherapy for relapsed/refractory non-Hodgkin lymphomas after CD19 chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cell therapy. Br J Haematol, 190(1): 45-51. 10.1111/bjh.16541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson P, Federico M, Kirkwood A, et al. , 2016. Adapted treatment guided by interim PET-CT scan in advanced Hodgkin’s lymphoma. N Engl J Med, 374(25): 2419-2429. 10.1056/NEJMoa1510093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Josting A, Wiedenmann S, Franklin J, et al. , 2003. Secondary myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic syndromes in patients treated for Hodgkin’s disease: a report from the German Hodgkin’s Lymphoma Study Group. J Clin Oncol, 21(18): 3440-3446. 10.1200/JCO.2003.07.160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juweid ME, Stroobants S, Hoekstra OS, et al. , 2007. Use of positron emission tomography for response assessment of lymphoma: consensus of the imaging subcommittee of international harmonization project in lymphoma. J Clin Oncol, 25(5): 571-578. 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.2305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowles SM, Wu AM, 2012. Advances in immuno-positron emission tomography: antibodies for molecular imaging in oncology. J Clin Oncol, 30(31): 3884-3892. 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.4887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreissl S, Goergen H, Buehnen I, et al. , 2021. PET-guided eBEACOPP treatment of advanced-stage Hodgkin lymphoma (HD18): follow-up analysis of an international, open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Haematol, 8(6): e398-e409. 10.1016/S2352-3026(21)00101-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtz DM, Scherer F, Jin MC, et al. , 2018. Circulating tumor DNA measurements as early outcome predictors in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol, 36(28): 2845-2853. 10.1200/JCO.2018.78.5246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaCasce AS, Dockter T, Ruppert AS, et al. , 2021. CALGB 50801 (Alliance): PET adapted therapy in bulky stage I/II classic Hodgkin lymphoma (cHL). J Clin Oncol, 39(S15): 7507. 10.1200/JCO.2021.39.15_suppl.7507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson SM, Erdi Y, Akhurst T, et al. , 1999. Tumor treatment response based on visual and quantitative changes in global tumor glycolysis using PET-FDG imaging: the visual response score and the change in total lesion glycolysis. Clin Positron Imaging, 2(3): 159-171. 10.1016/s1095-0397(99)00016-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- le Gouill S, Ghesquières H, Oberic L, et al. , 2021. Obinutuzumab vs rituximab for advanced DLBCL: a PET-guided and randomized phase 3 study by LYSA. Blood, 137(17): 2307-2320. 10.1182/blood.2020008750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin C, Itti E, Haioun C, et al. , 2007. Early 18F-FDG PET for prediction of prognosis in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: SUV-based assessment versus visual analysis. J Nucl Med, 48(10): 1626-1632. 10.2967/jnumed.107.042093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luminari S, Biasoli I, Versari A, et al. , 2014. The prognostic role of post-induction FDG-PET in patients with follicular lymphoma: a subset analysis from the FOLL05 trial of the Fondazione Italiana Linfomi (FIL). Ann Oncol, 25(2): 442-447. 10.1093/annonc/mdt562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamot C, Klingbiel D, Hitz, F, et al. , 2015. Final results of a prospective evaluation of the predictive value of interim positron emission tomography in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with R-CHOP-14 (SAKK 38/07). J Clin Oncol, 33(23): 2523-2529. 10.1200/JCO.2014.58.9846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matasar MJ, Zelenetz AD, 2008. Overview of lymphoma diagnosis and management. Radiol Clin North Am, 46(2): 175-198. 10.1016/j.rcl.2008.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matasar MJ, Ford JS, Riedel ER, et al. , 2015. Late morbidity and mortality in patients with Hodgkin’s lymphoma treated during adulthood. J Natl Cancer Inst, 107(4): djv018. 10.1093/jnci/djv018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta-Shah N, Ito K, Bantilan K, et al. , 2019. Baseline and interim functional imaging with PET effectively risk stratifies patients with peripheral T-cell lymphoma. Blood Adv, 3(2): 187-197. 10.1182/bloodadvances.2018024075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moskowitz CH, Schöder H, Teruya-Feldstein J, et al. , 2010. Risk-adapted dose-dense immunochemotherapy determined by interim FDG-PET in advanced-stage diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol, 28(11): 1896-1903. 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.5942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mounier N, Brice P, Bologna S, et al. , 2014. ABVD (8 cycles) versus BEACOPP (4 escalated cycles ≥4 baseline): final results in stage III-IV low-risk Hodgkin lymphoma (IPS 0‒2) of the LYSA H34 randomized trial. Ann Oncol, 25(8): 1622-1628. 10.1093/annonc/mdu189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardal E, Coronado M, Martín A, et al. , 2014. Intensification treatment based on early FDG-PET in patients with high-risk diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: a phase II GELTAMO trial. Br J Haematol, 167(3): 327-336. 10.1111/bjh.13036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlovsky A, Fernandez I, Kurgansky N, et al. , 2019. PET-adapted therapy after three cycles of ABVD for all stages of Hodgkin lymphoma: results of the GATLA LH-05 trial. Br J Haematol, 185(5): 865-873. 10.1111/bjh.15838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlovsky A, Fiad NL, Prates MV, et al. , 2022. P1081: PET-adapted therapy after three cycles of ABVD for all stages of Hodgkin lymphoma: long term follow up of the GATLA LH-05 trial. HemaSphere, 6: 971-972. 10.1097/01.HS9.0000847192.97515.16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persky DO, Li HL, Stephens DM, et al. , 2020. Positron emission tomography-directed therapy for patients with limited-stage diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: results of intergroup National Clinical Trials Network study S1001. J Clin Oncol, 38(26): 3003-3011. 10.1200/JCO.20.00999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pregno P, Chiappella A, Bellò M, et al. , 2012. Interim 18-FDG-PET/CT failed to predict the outcome in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patients treated at the diagnosis with rituximab-CHOP. Blood, 119(9): 2066-2073. 10.1182/blood-2011-06-359943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Press OW, Li HL, Schöder H, et al. , 2016. US intergroup trial of response-adapted therapy for stage III to IV Hodgkin lymphoma using early interim fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography imaging: Southwest Oncology Group S0816. J Clin Oncol, 34(17): 2020-2027. 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.1119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radford J, Illidge T, Counsell N, et al. , 2015. Results of a trial of PET-directed therapy for early-stage Hodgkin’s lymphoma. N Engl J Med, 372(17): 1598-1607. 10.1056/NEJMoa1408648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricardi U, Levis M, Evangelista A, et al. , 2021. Role of radiotherapy to bulky sites of advanced Hodgkin lymphoma treated with ABVD: final results of FIL HD0801 trial. Blood Adv, 5(21): 4504-4514. 10.1182/bloodadvances.2021005150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigacci L, Puccini B, Zinzani PL, et al. , 2015. The prognostic value of positron emission tomography performed after two courses (INTERIM-PET) of standard therapy on treatment outcome in early stage Hodgkin lymphoma: a multicentric study by the Fondazione Italiana Linfomi (FIL). Am J Hematol, 90(6): 499-503. 10.1002/ajh.23994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safar V, Dupuis J, Itti E, et al. , 2012. Interim [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography scan in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with anthracycline-based chemotherapy plus rituximab. J Clin Oncol, 30(2): 184-190. 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.2648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sehn LH, Scott DW, Villa D, et al. , 2019. Long-term follow-up of a PET-guided approach to treatment of limited-stage diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) in British Columbia (BC). Blood, 134(S1): 401. 10.1182/blood-2019-128722 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shah NN, Nagle SJ, Torigian DA, et al. , 2018. Early positron emission tomography/computed tomography as a predictor of response after CTL019 chimeric antigen receptor-T-cell therapy in B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas. Cytotherapy, 20(12): 1415-1418. 10.1016/j.jcyt.2018.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaikh PM, Alite F, Pugliese N, et al. , 2020. Consolidation radiotherapy following positron emission tomography complete response in early-stage Hodgkin lymphoma: a meta-analysis. Leuk Lymphoma, 61(7): 1610-1617. 10.1080/10428194.2020.1725506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieniawski M, Reineke T, Josting A, et al. , 2008. Assessment of male fertility in patients with Hodgkin’s lymphoma treated in the German Hodgkin Study Group (GHSG) clinical trials. Ann Oncol, 19(10): 1795-1801. 10.1093/annonc/mdn376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens DM, Li HL, Schöder H, et al. , 2019. Five-year follow-up of SWOG S0816: limitations and values of a PET-adapted approach with stage III/IV Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood, 134(15): 1238-1246. 10.1182/blood.2019000719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart DA, Kloiber R, Owen C, et al. , 2014. Results of a prospective phase II trial evaluating interim positron emission tomography-guided high dose therapy for poor prognosis diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma, 55(9): 2064-2070. 10.3109/10428194.2013.862242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus DJ, Jung SH, Pitcher B, et al. , 2018. CALGB 50604: risk-adapted treatment of nonbulky early-stage Hodgkin lymphoma based on interim PET. Blood, 132(10): 1013-1021. 10.1182/blood-2018-01-827246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swinnen LJ, Li HL, Quon A, 2015. Response-adapted therapy for aggressive non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas based on early [18F] FDG-PET scanning: ECOG-ACRIN Cancer Research Group study (E3404). Br J Haematol, 170(1): 56-65. 10.1111/bjh.13389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toledano MN, Desbordes P, Banjar A, et al. , 2018. Combination of baseline FDG PET/CT total metabolic tumour volume and gene expression profile have a robust predictive value in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging, 45(5): 680-688. 10.1007/s00259-017-3907-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vijenthira A, Chan K, Cheung MC, et al. , 2020. Cost-effectiveness of first-line treatment options for patients with advanced-stage Hodgkin lymphoma: a modelling study. Lancet Haematol, 7(2): e146-e156. 10.1016/S2352-3026(19)30218-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villa D, Sehn LH, Aquino-Parsons C, et al. , 2018. Interim PET-directed therapy in limited-stage Hodgkin lymphoma initially treated with ABVD. Haematologica, 103(12): e590-e593. 10.3324/haematol.2018.196782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viviani S, Zinzani PL, Rambaldi A, et al. , 2011. ABVD versus BEACOPP for Hodgkin’s lymphoma when high-dose salvage is planned. N Engl J Med, 365(3): 203-212. 10.1056/NEJMoa1100340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanoni L, Mattana F, Calabrò D, et al. , 2021. Overview and recent advances in PET/CT imaging in lymphoma and multiple myeloma. Eur J Radiol, 141: 109793. 10.1016/j.ejrad.2021.109793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zasadny KR, Kison PV, Francis IR, et al. , 1998. FDG-PET determination of metabolically active tumor volume and comparison with CT. Clin Positron Imaging, 1(2): 123-129. 10.1016/s1095-0397(98)00007-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu CT, Zhao Y, Yu F, et al. , 2021. Tumor flare reaction in a classic Hodgkin lymphoma patient treated with brentuximab vedotin and tislelizumab: a case report. Front Immunol, 12: 756583. 10.3389/fimmu.2021.756583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zinzani PL, Broccoli A, Gioia DM, et al. , 2016. Interim positron emission tomography response-adapted therapy in advanced-stage Hodgkin lymphoma: final results of the phase II part of the HD0801 study. J Clin Oncol, 34(12): 1376-1385. 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.0699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]