Abstract

Aims

This paper aims to systematically identify reported health state utility values (HSUVs) in children and adolescents with mental health problems (MHPs) aged less than 25 years; to summarise the techniques used to elicit HSUVs; and to examine the psychometric performance of the identified multi-attribute utility instruments (MAUIs) used in this space.

Methods

A systematic review was conducted following PRISMA guidelines. Peer-reviewed studies published in English, reporting HSUVs for children and adolescents with MHPs using direct or indirect valuation methods were searched in six databases.

Results

We found 38 studies reporting HSUVs for 12 types of MHPs across 12 countries between 2005 and October 2021. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and depression are the most explored MHPs. Disruptive Behaviour Disorder was associated with the lowest reported HSUVs of 0.06 while cannabis use disorder was associated with the highest HSUVs of 0.88. Indirect valuation method through the use of MAUIs (95% of included studies) was the most frequently used approach, while direct valuation methods (Standard Gamble, Time Trade-Off) were only used to derive HSUVs in ADHD. This review found limited evidence of the psychometric performance of MAUIs used in children and adolescents with MHPs.

Conclusion

This review provides an overview of HSUVs of various MHPs, the current practice to generate HSUVs, and the psychometric performance of MAUIs used in children and adolescents with MHPs. It highlights the need for more rigorous and extensive psychometric assessments to produce evidence on the suitability of MAUIs used in this area.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11136-023-03441-x.

Keywords: Health state utility values, Children and adolescents, Mental health problems

Introduction

Mental health problems (MHPs) denote a worldwide public health challenge and one of the leading causes of disability in children and youth population [1, 2]. With the prevalence being around 14% worldwide, MHPs often account for a high global burden of disease (13% of disability-adjusted life-years) [3]. MHPs often persist to adulthood, impacting not only the health and well-being of children and youth but also their socioeconomic trajectories and family life [4]. Depression, anxiety and behavioural disorders are among the leading causes of disability while suicide is one of the leading causes of death among youths [3].

Economic evaluation is increasingly used to inform decision-making in priority setting worldwide, and is often recommended by government agencies [5]. Economic evaluations using cost-utility analyses (CUAs) commonly require the estimation of quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) to capture the benefits resulting from health interventions. QALYs are calculated by combining length of life and health-related quality of life (HRQoL), where the time spent in a particular health state is weighted by corresponding health state utility values (HSUVs)—used to denote the “quality” in QALYs [6]. HSUVs represent the strength of preference for a particular health state and are anchored on a cardinal scale between 0 (dead) and 1 (full health), where full health is usually defined by the domains of HRQoL measured on each instrument [7].

HSUVs can be derived using either direct or indirect valuation methods [6]. Direct methods include choice-based valuation methods, such as standard gamble (SG), time trade-off (TTO), discrete choice experiments, or best–worst scaling to value health state description (vignettes) or individual’s health state. Indirect valuation method involves the use of generic multi-attribute utility instruments (MAUIs) which usually comprise a descriptive system (largely health related quality of life questionnaires) describing various dimensions of HRQoL, and a preference-based scoring algorithm (tariff) used to convert responses from the descriptive system to a single, numeric HSUV [7]. MAUIs are available as self-report (i.e. one assesses one’s own health state) or proxy-report (i.e. one assesses the health state experienced by someone else) [7].

In modelling-based economic evaluations, analysts may not have the resources and time to acquire original HSUVs for health states of interest, thus often relying on systematic reviews on HSUVs as a robust and transparent source of evidence for various health conditions. Furthermore, HSUVs can be used to explore the burden of disease, especially when compared to population norms or people without the disorder in question. To the best of our knowledge, there has been no previous systematic review on HSUVs for children and youth with MHPs. Furthermore, with the reorientation of mental health services aimed at the young population, which is widely defined as those aged between 15 and 25 years [8], an age group that often experiences a high rate of MHPs [9], exploring HSUVs for the age range up to 25 years is helpful to support studies aimed at this age group which would otherwise be unintentionally excluded by the artificial cut-off point of being 18 years old between adolescents and adults [10].

Over the last decade, while there has been an increased focus on the valuation methods using MAUIs to produce HSUVs for children and youth, the guidelines from international agencies for assessing health outcomes in this population remain unclear [10, 11]. This is concerning as an adequate measure to capture healthcare interventions’ benefits plays a crucial role in the robustness, transparency and rigour of economic evaluations. In adult population, it is well reported that some commonly used MAUIs lack sensitivity to measure the impact of MHPs on quality of life [12]. Specifically, there is evidence that the most commonly used MAUIs, such as the EQ-5D and SF-36 are not sufficiently sensitive to reflect the impact of severe MHPs such as schizophrenia [13, 14], or bipolar disorder [15]. Meanwhile, the psychometric performance of MAUIs used in children and youth with MHPs is not well explored.

The aims of this paper are three-fold: (i) to identify reported utility values associated with MPHs in children and youth aged less than 25 years and conduct a meta-analysis of reported HSUVs if appropriate; (ii) to summarise the elicitation techniques used to derive utility values among children and youth with MPHs; and (iii) to provide a summary of the evidence on the psychometric performance of the identified MAUIs used in this space.

Methods

Search strategy

A systematic literature review was conducted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) checklist [16]. Systematic searches without time limit were conducted in MEDLINE (via Ovid), CINAHL (via EBSCOhost), PsycINFO (via EBSCOhost), Embase (1947 onwards), EconLit (1886 onwards), Cochrane Library (including the Health Technology Assessment Database and NHS Economic Evaluation Database) in October 2021. Search terms (Supplementary Document 1) were developed based on main concepts of (a) HSUVs, (b) direct preference elicitation methods, (c) indirect preference elicitation methods, (d) population of interest, and (e) MHPs. A search strategy that included both keywords and Medical Subject Headings (MESH) terms was developed for MEDLINE (Ovid) and subsequently translated to other databases (Supplementary Document 1). Covidence program was used for duplicate removal and for the screening process. Titles and abstracts were completed by three independent reviewers (TT, JP and AT). If an article received two positive votes, it moved to the next stage of full-text screening. In case of conflicts, a third reviewer was referred to make the final assessment. The same process occurred in the full-text screening.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

-

(i)

Type of study: (a) observational and experimental design studies estimating HSUVs in children and youths with MHPs using either direct or indirect elicitation methods; (b) trial-based or model-based economic evaluations, describing the use of HSUVs in CUA of interventions addressing MHPs for children and youths.

-

(ii)

Study population: Child and young populations (aged up to 25 years) with any MHPs with diagnostic assessment or screened by a self-reported measure such as Kessler-10. Autism-related studies were excluded following national classifications, which do not classify autism as an MHP [17, 18]. As the review focused on studies reporting HSUVs for MHPs, we excluded studies reporting HSUVs for comorbidities with MHPs (e.g., heart disease and depression).

-

(iii)

Type of respondents: proxy- or self-reported HSUVs were included.

-

(iv)

Type of publication: peer-reviewed studies and written in English. Grey literature (e.g., conference abstracts and proceedings, discussion papers, reports, and unpublished theses) were excluded. Articles that reported HSUVs derived from non-generic MAUI (if using indirect preference elicitation methods) were excluded. Previous relevant systematic reviews [19, 20] were used for manual article searching.

Data extraction

Data extraction was conducted by TT and checked by two other authors (AT and JP). The following data were extracted:

Study description: lead author, publication year, country of publication, sample size, study type.

Study population characteristics: age range, mental health condition. We classified the age groups following the recommended practice from the Australian government as: early childhood (< 5 years), primary school children (5–12 years), adolescence (12–19 years) and young adults (20–25 years) [21].

Direct valuation method: method used, proxy- or self-report, reported mean and standard deviation of HSUVs.

Indirect valuation method: generic MAUIs used, proxy- or self-report, algorithm applied, reported mean and standard deviation HSUVs.

For studies reporting HSUVs at different time points, we only extracted baselines scores. For studies reporting HSUVs for more than one type of MHPs, HSUVs for each MHPs were extracted with the corresponding sub-samples. Meta-analysis of reported HSUVs was only conducted if reported HSUVs for the same health condition were derived from the same population using the same valuation method with the same country-specific algorithms [22].

Assessment of psychometric performance

Assessment of the psychometric performance of MAUIs was based on its reliability, validity, and responsiveness as outlined in Rowen et al. [23]. Data were extracted about the following information if available.

Name of MAUIs used, algorithms used, whether the MAUI was self-reported and/or proxy-reported by parents/caregivers, health professionals.

Study sample type of mental health problems studied, sample size, and age range.

Known-group or discriminant validity refers to the ability of an instrument to reflect known-group differences (e.g. with and without the condition).

Convergent validity refers to the extent to which an instrument converges with other measures of the same concept (i.e., the strength of association with other measures of the same concept).

Responsiveness is the capacity of a MAUI to reliably detect changes in HRQoL because of a change in their health status.

Reliability reflects the ability of an instrument in reproducing unchanged utility values where no change in health is detected when measured (a) at two different time points (test–retest reliability), (b) using different administration modes (intermodal reliability), (c) by different respondents (interrater reliability) [23].

Acceptability and feasibility are assessed by the proportion of missing answers and respondents’ understanding of the measure.

Internal consistency reliability explores whether items within a MAUI are measuring the same construct.

Results

Search results

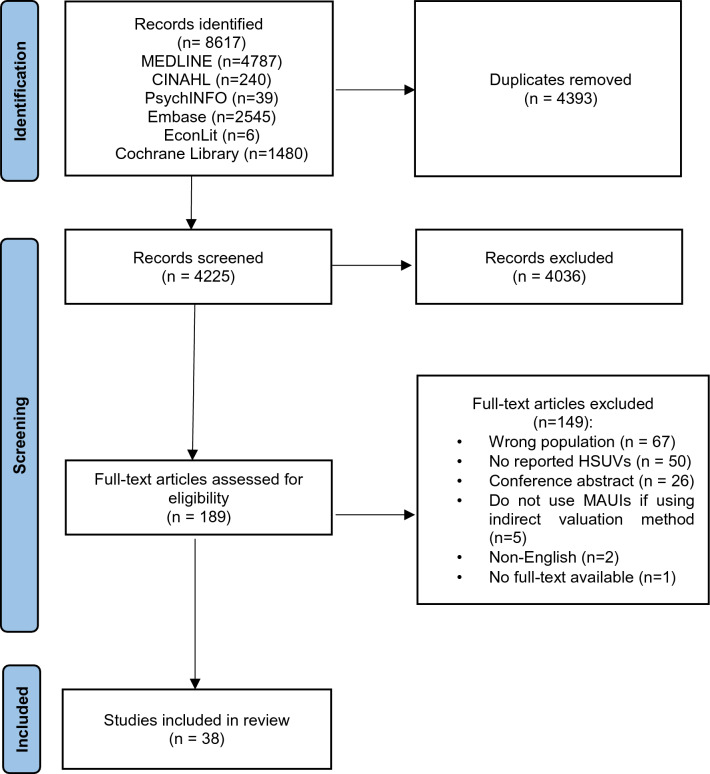

After deduplication, 4225 articles were included for the title and abstract screening. Based on the selection criteria, we screened 189 full texts and of these, 38 were included for data extraction. A PRISMA flow chart of the study selection process is provided in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA diagram

Study characteristics

Table 1 summarises the characteristics of 38 included articles that cover 12 types of MHPs from 2005 to 2021 (Supplementary document 2 for more information). Most studies (89%) were conducted between 2010 and 2021, which indicates a growing research interest in the burden associated with youth mental health. Of 38 included studies, 20 were cross-sectional studies and 18 were randomised controlled trials.

Table 1.

Study characteristics and reported utility values by type of mental health conditions

| First author, year (Reference) | Country | Type of conditions | Type of study | N | Age range (mean age) | Instruments | Algorithm | Perspectives | Utility scores Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. ADHD | |||||||||

| Matza, 2005 [27] | US | ADHD | Cross-sectional | 43 | 5–17 (10.2) | SG | NA | Proxy-report (parents) |

Mild ADHD 0.71 (SD 0.25); Moderate ADHD 0.58 (SD 0.27); Severe ADHD 0.48 (SD 0.28) |

| Secnik, 2005 [30] | UK | ADHD | Cross-sectional | 83 | 7–18 (12.6) | SG, EQ-5D-3L | EQ-5D-3L: UK | Proxy-report (parent) |

Child’s own current health state: SG 0.72 (0.21) EQ-5D-3L: 0.74 (0.19) |

| Lloyd, 2011 [66] | UK | ADHD | Cross-sectional | 100 | 8–16 (11) | TTO | NA | Proxy-report (general public) |

Borderline to mildly ill: 0.787 (0.217) Moderately to markedly ill 0.578 (0.275) Severely ill 0.444 (0.230) |

| Matza, 2005 [61] | US and UK | ADHD | Cross-sectional | 43 (US) and 83 (UK) | 7–18 (11.8) | EQ-5D-3L | UK | Proxy-report (parent) |

Total sample: 0.75 (0.17) US sample: 0.78 (0.15) UK sample: 0.74 (0.19) |

| Peasgood, 2016 [29] | UK | ADHD | Cross-sectional | 476 | 6–18 (11.8) | EQ-5D-Y, CHU9D | CHU9D: UK (adults) | Self-report |

EQ-VAS 80.16 (SD 20.61); CHU9D 0.82 (SD 0.12) EQ-5D-Y: not reported |

| Bouwmans, 2014 [40] | Netherlands | ADHD | Cross-sectional | 739 | 6–18 (11.9) | EQ-5D-3L | Dutch (adults) | Proxy-report (parent) | 0.81 (0.17) |

| Maia, 2016 [58] | Brazil | ADHD | A naturalistic study | 62 children and 28 adolescents |

6–17 Children mean age = 8.62, Adolescent mean age = 13.67) |

HUI2 and HUI3 | Canada tariff | Proxy-report (parent) |

Children: 0.69; Adolescents: 0.66 |

| Sayal, 2016 [31] | UK | At risk of ADHD | RCT | 55 teachers and 40 parents | 4–8(6.16) | EQ-5D-Y and CHU9D |

EQ-5D-Y: UK (adults) CHU9D: UK (adults) |

Proxy-report (parent and teacher) |

Control arm: EQ-5D-Y 0.815 (0.257), CHU9D 0.847 (0.099); Parent only arm: ED-5D-Y 0.734 (0.370) CHU9D (0.818 (0.128); Parent + Teacher arm: EQ-5D-Y 0.771 (0.294); CHU9D 0.897 (0.102) |

| Le 2021 [24] | Australia | ADHD | Cross-sectional | 160 | 11–17 | CHU-9D | Australia (adolescents) | Self-report | 0.74 (0.19) |

| Petrou, 2010 [25] | UK and Republic of Ireland | ADHD | Cross-sectional | 331 term-born classmates | 5–11 | HUI2&HUI3 |

HUI3: Canada (adults) HUI2: UK (adults) |

Proxy report (parents) |

HUI3: 0.629 (0.271); HUI2: 0.792 0.120 |

| 2. Anxiety disorder | |||||||||

| Bodden, 2008 [41] | Netherlands | Anxiety disorder (except for obsessive–compulsive disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder | RCT | 116 | 8–17 years (12.3) | EQ-5D-3L | UK (adults) | Self-report |

Control: 0.87 (0.13), Intervention: 0.83 (0.20) |

| Creswell, 2017 [32] | UK | Anxiety disorders | RCT | 136 | 5–12 years | CHU9D | UK tariff | Self- and proxy-report (parent) |

Self-reported: CHU9D: Control 0·87 (0·09); Intervention 0·88 (0·09) EQ-5D-Y: Control 0·82 (0·15); Intervention 0·80 (0·20) Proxy-reported: CHU9D: Control 0·85 (0·10); Intervention 0·89 (0·07) |

| Chatterton, 2019 [53] | Australia | Anxiety disorder | RCT | 281 | 7–17 | CHU9D | Australia (adolescents) | Self-report | Control: 0.62 (0.24), Intervention 0.64 (0.21) |

| Le 2021 [24] | Australia | Anxiety disorder | Cross-sectional | 97 | 11–17 | CHU-9D | Australia (adolescents) | Self-report | 0.70 (0.24) |

| Astrom, 2020 [26] | Sweden | Anxiety disorder | Cross-sectional | 13 | 13–17 (15.4) | EQ-5D-Y-5L and EQ-VAS | NA | Self-report |

EQ-VAS: 23.5 (15.8) EQ-5D-Y-5L: not reported |

| 3. Depression | |||||||||

| Lynch, 2016 [56] | US | Depression | Cross-sectional | 169 | 13–17 (15.4) | HUI2 and HUI3, EQ-5D-3L, QWB, SF6D |

HUI2&3: Canada EQ-5D-3L QWB SF-6D: UK general population |

Self-report |

HUI-2: 0.695 (SD 0.183); HUI3 0.545 (SD 0.266); EQ-5D 0.759 (SD 0.154); QWB 0.574 (SD 0.090); SF-6D 0.645 (SD 0.087) |

| Turner, 2017 [33] | UK | Depression | RCT | 86 | 14–17 | EQ-5D-5L | UK | Self-report |

Control 0.82 Intervention 0.74 |

| Dickerson, 2018 [57] | US | Depression | Cross-sectional | 376 | 13–17 | (EQ-5D-3L), (HUI2) and (HUI3), (QWB), (SF-6D) |

HUI2&3: Canada EQ-5D-3L QWB SF-6D: UK general population |

Self-report |

HUI2 0.73 (0.18); HUI3 0.56 (0.27); EQ-5D-3L 0.81 (0.15); QWB 0.60 (0.09); SF-6D 0.67 (0.09) |

| Byford, 2013[35] | UK | Depression | RCT | 199 | 11–17 | EQ-5D-3L | UK adult tariff | Self-report | 0.495 (SD 0.296) |

| Byford, 2007 [34] | UK | Depression | RCT | 208 | 11–17 | EQ-5D-3L | UK adult tariff | Self-report | Intervention: 0.49 (0.30); Control: 0.50 (0.29) |

| Wright, 2017 [36] | UK | Depression | RCT | 91 | 12–18 | EQ-5D-Y, HUI-2 | Self-report |

EQ-5D-Y: Intervention: 0.53 (0.26); Control 0.60 (0.33); HUI-2: not reported |

|

| Goodyer, 2017 [37] | UK | Depression | RCT | 447 | 11–17 | EQ-5D-3L | UK adult tariff | Self-report |

Intervention 1: 0.596 (0.275); Intervention 2: 0.578 (0.281); Intervention 3: 0.569 (0.258) |

| Le 2021 [24] | Australia | Major depressive disorder | Cross-sectional | 159 | 11–17 | CHU9D | Australia (adolescents) | Self-report | 0.64 (0.26) |

| Astrom, 2020 [26] | Sweden | Depressive episode/recurrent depressive disorder | Cross-sectional | 15 | 13–17 (15.4) | EQ-5D-Y-5L and EQ-VAS | NA | Self-report |

EQ-VAS: 28.2 (14.4) EQ-5D-Y-5L: not reported |

| 4. Undefined psychiatric disorders | |||||||||

| Petrou, 2010 [25] | UK and Republic of Ireland | Psychiatric disorders | Cross-sectional | 50 | 5–12 | HUI2&HUI3 |

HUI3: Canada (adults) HUI2: UK (adults) |

Proxy report (parents) |

HUI3: Any DSM–IV clinical diagnosis 0.698 (0.273); HUI2: Any DSM–IV clinical diagnosis 0.782 (0.149) |

| Ougrin, 2018 [39] | UK | Psychiatric inpatients | RCT | 106 | 12–17 | EQ-5D-3L | UK (adults) | Self-report |

Intervention: 0.5 (0.3) Control: 0.6 (0.4) |

| Astrom, 2020 [26] | Sweden | Psychiatric inpatients | Cross-sectional | 52 | 13–17 (15.4) | EQ-5D-Y-5L and EQ-VAS | NA | Self-report |

All disorders by age group 13–17 years: 29.2 (19.5) 13–15 years: 25.3 (19.4) 16–17 years: 32.6 (19.3) Bipolar affective disorder: 28.3 (27.7) Reaction to severe stress/ adjustment disorders: 42.5 (23.2) Other: 23.1 (15.1) Observation for suspected mental and behavioural disorders: 39.0 (28.6) |

| 5. Internalizing problems | |||||||||

| Philipsson, 2013 [50] | Sweden | Internalizing problems with recurrent visits to the school nurse for psychosomatic symptoms | RCT | 112 girls | 13–18 | HUI 3 | Self-report |

Intervention: 0.71 (0.66– 0.77) Control: 0.77 (0.73–0.82) |

|

| 6. Personality disorders | |||||||||

| Swales 2016 [38] | UK | Borderline personality disorder | Cross-sectional | 76 | 14–18 | EQ-5D-3L | UK tariff | Self-report (some used clinicians as proxy) | 0.236 (SD 0.32) |

| Feenstra, 2012 [63] | Netherlands | Personality disorders | Cross-sectional | 131 | 14–19 (16.6) | EQ-5D-3L | Dutch tariff | Self-report |

Total: 0.55 (SD 0.27); Borderline personality disorder 0.49 (0.28), Avoidant personality disorder 0.49 (0.27), Personality disorder not otherwise specified 0.70(0.23), Depressive personality disorder 0.34(0.20), Obsessive–compulsive personality disorder 0.50 (0.33) |

| 7. Behaviour disorders | |||||||||

| Vermeulen, 2017 [43] | Netherlands |

Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD), Conduct Disorder (CD), Disruptive Behaviour Disorder (DBD) |

Cross-sectional | Professionals, children, adolescents and parents | 4–18 | EQ-5D-3L | UK tariff | Proxy report (parents, professionals and children) |

Professionals: Children: ODD 0.58 (0.08), CD 0.47 (0.14), DBD 0.58 (0.08), Adolescents: ODD 0.59 (0.12), CD 0.58 (0.15), DBD 0.59 (0.12); Parents: Regular primary education (children’s parents): ODD 0.52 (0.080), CD 0.36 (0.125), DBD 0.28 (0.122) Regular secondary education (adolescents’ parents): ODD 0.49 (0.12), CD 0.23 (0.12), DBD 0.12 (0.12), Vocational training (parents of adolescents with behaviour disorders) ODD 0.485 (0.14), CD 0.269 (0.13), DBD 0.190 (0.14); Children and adolescents: Regular primary education (children) ODD 0.31 (0.15), CD 0.11 (0.09), DBD 0.06 (0.07), Regular secondary education (adolescents) ODD 0.52 (0.12), CD 0.31 (0.13), DBD 0.20 (0.13), Vocational training (adolescents) ODD 0.37 (0.14), CD 0.19 (0.15), DBD 0.12 (0.15) Adolescents in vocational training (with behavioural disorders): own valuation 0.84 (0.008) |

| Le 2021 [24] | Australia | Conduct disorder | Cross-sectional | 48 | 11–17 | CHU-9D | Australia (adolescents) | Self-report | 0.71 (0.23) |

| Petrou, 2010 [25] | UK and Republic of Ireland | Emotional disorder; Conduct disorder | Cross-sectional |

Emotional disorder n = 16 Conduct disorder n = 17 |

5–12 | HUI2&HUI3 |

HUI3: Canada (adults) HUI2: UK (adults) |

Proxy report (parents) |

HUI3: Any emotional disorder 0.672 (0.296); Any conduct disorder 0.727 (0.260); HUI2: Any emotional disorder 0.760 0.161; Any conduct disorder 0.802 0.129; |

| 8. Post-traumatic stress disorder | |||||||||

| Dams, 2021 [64] | Germany | PTSD | RCT | 87 | 14–21 (18.1) | EQ-5D-5L | German (adults) | Self-report | 0.70 (0.25) |

| Dams, 2020 [52] | Germany | PTSD | RCT | 87 | 14–21 | EQ-5D-5L | German (adults) | Self-report | 0.70 (0.03) |

| Aas, 2019 [60] | Norway | PTSD | RCT | 156 | 10–18 | 16D | Finland | Self-report | Intervention: 0.755 (0.012); Control: 0.777 (0.104) |

| 9. Substance use disorders | |||||||||

| Goorden, 2015 [44] | Netherlands | Cannabis use disorder | RCT | 96 (Control 49; Intervention 47) | 13–18 | EQ-5D-3L | Dutch (adults) | Self-report |

Intervention: 0.88 (0.15) Control: 0.89 (0.13) |

| Reckers-Droog, 2020 [45] | Netherlands | Adolescents receiving in- or outpatient mental health care with substance use | Cross-sectional | 167 | 12–18 (15.2) | EQ-5D-3L | Dutch (adults) | Self-report |

Alcohol use 0.82 (0.23); Drugs use 0.83 (0.18); Medicine use 0.81 (0.18); Delinquency 0.82 (0.23) |

| 10. Psychosis | |||||||||

| Grano, 2014 [48] | Finland | At risk for psychosis | Cross-sectional | 202 | 11–22 (15.6) | 16D | Finland | Self-report |

Not at heightened risk of developing psychosis: 0.87 2(0.091) At heightened risk of developing psychosis: 0.795 (0.106) |

| Grano, 2013 [47] | Finland | At risk for psychosis | Cross-sectional |

Total: 90 (Not at heightened risk n = 55; At heightened risk n = 35) |

12–21 (15.1) | 16D | Finland | Self-report |

Not at heightened risk of developing psychosis: 0.8737 (0.0931) At heightened risk of developing psychosis: 0.7992 (0.1) |

| Grano, 2015 [46] | Finland | At risk for psychosis | Cross-sectional |

181 (At risk n = 57 Help-seekers n = 124) |

12–22 (15.3) | 16D | Finland | Self-report |

At risk: 0.80 (0.10) Help-seekers (not at risk): 0.87 (0.09) |

| 11. Self-harm | |||||||||

| Tubeuf, 2019 [28] | UK | Self-harm | RCT | 754 | 11–17 | EQ-5D-3L | UK | Self-report | 0.68 (0.27) |

| Le, 2021 [24] | Australia |

Self-harm Suicide ideation |

Cross-sectional |

Self-harm: n = 328 Suicide ideation n = 220 |

11–17 | CHU9D | Australian (adolescents) | Self-report |

Self-harm: 0.57 (0.26); Suicide ideation 0.54 (0.26) |

| 12. General mental health problems | |||||||||

| Le, 2019 [54] | Australia | Mental health problems screened by Kessler-10 | RCT | 413 | 18–25 | AQoL4D | Australian | Self-report | Both intervention and control groups: 0.56 (0.26) |

| Furber, 2015 [55] | Australia | Having an open episode of mental health care within the last 6 weeks Mental health problems | Cross-sectional | 200 | 5–17 (11.71) | CHU9D | UK (adults) and Australian (Adolescents) tariffs | Proxy report (caregivers) |

UK tariff: 0.803 (0.117); Australian tariff: 0.739 (0.145) |

| Le 2021 [24] | Australia | Mental health diagnosis by Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC-IV) | Cross-sectional | 415 | 11–17 | CHU9D | Australia (adolescents) | Self-report | 0.70 (0.24) |

| Wolf, 2021 [59] | Denmark | Mental health problems screened by Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire | RCT | 396 | 6–15 (10.7) | CHU9D | UK (adults) and Australian (Adolescents) tariffs | Proxy report (parents) |

UK tariff: 0.804 (0.121); Australian tariff: 0.629 (0.214) |

Study population and conditions

Table 2 presents an overview of the 12 types of MHPs explored. Overall, 35 out of 38 studies assessed only one MHPs while three studies assessed more than one MHP such as 8 MHPs [24], or 3 MHPs [25, 26]. The most studied MHP was ADHD (n = 10), followed by depression (n = 9), anxiety disorders (n = 4), substance use (n = 4), undefined psychiatric disorders (n = 4), psychosis (n = 3), personality disorders (n = 2), behaviour disorders (n = 2), PTSD (n = 2), self-harm (n = 2), internalizing problems (n = 1), and general MHPs (n = 3). The sample size in included studies varied from 43 [27] to 754 [28]. The included studies were from the UK (n = 14) [28–39], the Netherlands (n = 6) [40–45], Finland (n = 3) [46–48], Sweden (n = 2) [26, 49, 50], Germany (n = 1) [51, 52], Australia (n = 4) [24, 53–55], US (n = 3) [27, 56, 57], and one study each from Brazil [58], Denmark [59], Norway [60], one study in Ireland and UK [25], and one in UK and US [61].

Table 2.

Elicitation techniques used by MHPs

| EQ-5D-3L | EQ-5D-5L | EQ-5D-Y | CHU9D | HUI2 | HUI3 | QWB | SF-6D | 16D | AQoL4D | SG | TTO | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADHD | 3 [30, 40, 61] | 2 [29, 31] | 3 [24, 29, 31] | 2 [25, 58] | 2 [25, 58] | 2 [27, 30] | 1 [66] | |||||

| AD | 1 [41] | [26] | 3 [24, 32, 53] | |||||||||

| Depression | 5 [34, 35, 37, 56, 57] | 1 [33] | 1 [26, 36] | 1 [24] | 3 [36, 56, 57] | 2 [56, 57] | 2 [56, 57] | 2 [56, 57] | ||||

| IPs | 1 [50] | |||||||||||

| PD | 2 [38, 63] | |||||||||||

| BD | 1 [43] | 1 [24] | 1 [25] | 1 [25] | ||||||||

| PTSD | 2 [52, 64] | 1 [60] | ||||||||||

| Substance use | 2 [44, 45] | 1 [65] | 1 [24] | |||||||||

| Psychiatric disorders | 1 [39] | 1 [26] | 1 [25] | 1 [25] | ||||||||

| Psychosis | 3 [46–48] | |||||||||||

| Self-harm | 1 [28] | 1 [24] | ||||||||||

| MHPs | 3 [24, 55, 59] | [54] |

AD anxiety disorder, AN anorexia nervosa, IPs internalizing problems, PTSD posttraumatic stress disorder, ADHD attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, PD personality disorder, BD behaviour problems, MHPs general mental health problems, SG standard gamble, TTO time trade-off

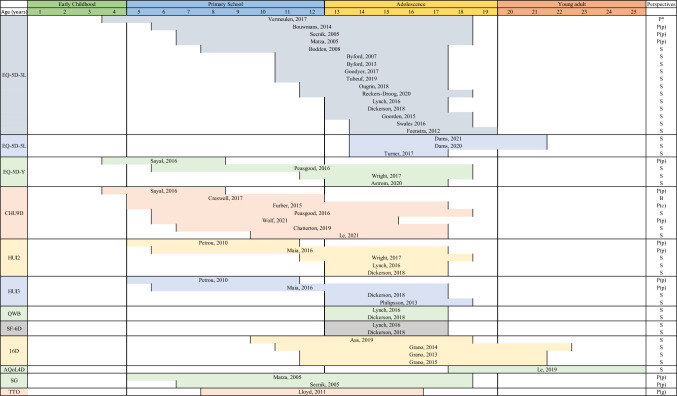

Age range

Figure 2 presents the age range of children and young population in included studies. The age range explored was between 4 and 25 years. EQ-5D-3L was used for a wider age range between 4–19 years. EQ-5D-5L was used mainly for youth aged 14–21. EQ-5D-Y was used for participants aged 4–18. CHU9D was used for children aged between 4 and 17 years. HUI2 and HUI3 were used for participants aged between 5 and 18 years. QWB and SF-6D were used only for adolescents aged 13–18 years. In terms of studies employing direct elicitation techniques, the SG was used for participants aged 5–18 years while TTO for those aged 9–16 years. For samples including mixed adolescents and adults, we found EQ-5D-3L was used for samples aged 14–19 years [63], EQ-5D-5L in samples aged 14–21 years [52, 64] and 15–19 years [65], 16D in samples aged between 11–22 years [46–48].

Fig. 2.

Elicitation methods by age range and perspectives. Notes: P* = Proxy report (parents, professionals and children); P(p) = Proxy-report (parents); P(c) = Proxy report (caregivers); P(g) = Proxy-report (general public); S = Self-report; B = Both self-report and Proxy-report

Valuation methods

Table 2 summarises valuation methods and instruments used in the included studies. Most studies (n = 36) adopted the indirect valuation method, while two used the direct valuation method including SG [27] and TTO [66] which were used only for ADHD. Among 10 MAUIs used as the indirect valuation method, EQ-5D-3L was the most frequently used (n = 16) in 9 types of MHPs, followed by CHU9D (n = 13), HUI2 (n = 7), HUI3 (n = 6), EQ-5D-Y (n = 5), EQ-5D-5L (n = 3), 16D (n = 4), QWB (n = 2), SF-6D (n = 2), and AQoL4D (n = 1). Several studies used more than one MAUI including two studies that used both EQ-5D-Y and CHU9D [29, 31], two using HUI2 and HUI3 [25, 58], one using EQ-5D-Y and HUI2 [36], and two studies using four MAUIs (HUI2, HUI3, EQ-5D-3L, QWB, SF6D) [56, 57]. One study used both direct (SG) and indirect valuation methods (EQ-5D-3L) [30].

Algorithms

EQ-5D-3L was used in five studies with the Dutch (adult) algorithm [40, 44, 45, 63], two with the German (adult) algorithm [52, 64], and four with the UK adult algorithm [30, 35, 38, 41]. EQ-5D-5L was used with the UK adult algorithm [33]. CHU9D was used with the UK adult algorithm in four studies [29, 31, 32, 59], and the Australian adolescent algorithm [53, 59]. HUI2 and HUI3 were used with the Canadian adult algorithm [56–58] while HUI2 was used with the UK adult algorithm in one study [25]. SF-6D was used with the UK adult [56, 57]. Only one study [31] reported HSUVs for EQ-5D-Y using the UK adult algorithm while another study using EQ-5D-Y did not report HSUVs [26] possibly due to the lack of a corresponding value set at the time [23].

Perspectives

Figure 2 summarises the use of elicitation methods and MAUIs used by perspectives. Twenty-eight studies administered the MAUI to children and youth using self-report while 16 studies used proxy-report (either a direct elicitation method and/or MAUIs) including parents (n = 13), caregivers (n = 1), teachers (n = 1), professionals (n = 1), general public (n = 1), and children and youth (i.e. evaluating bespoke health states description) (n = 1). Proxy-report was mainly adopted in studies exploring ADHD (8 out 10 studies) while all studies exploring depression, post-traumatic stress disorders, cannabis use disorder, psychosis and self-harm adopted self-report. Studies using the direct valuation methods such as SG [27, 30] and TTO [66] all adopted proxy-report. Indirect valuation methods were used with proxy-report for children as young as 4 years old [31] and self-report in children as young as 5 years old [32].

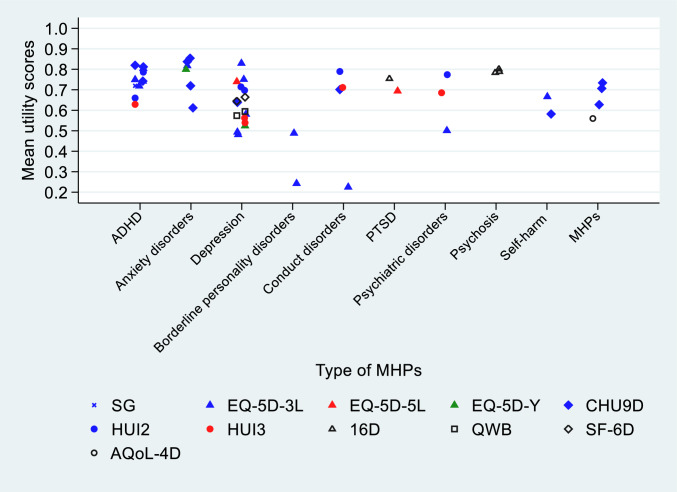

Reported utility values by MHPs

Figure 3 shows the HSUVs derived by different elicitation methods and MAUIs used across MHPs that were explored in more than one study. Across all generated HSUVs by MHPs, Disruptive Behaviour Disorder had the lowest HSUV of 0.06 [43] while cannabis use disorder was associated with the highest HSUVs of 0.88 [44].

Fig. 3.

Reported HSUVs by type of elicitation tools across MHPs. Notes: MHPs having HSUVs derived from only one study were excluded (internalising problems, medicine use, delinquency, tobacco use, other drug used disorders, avoidant personality disorder, personality disorder, depressive personality disorder, and obsessive-compulsive personality disorder)

HSUVs reported for ADHD ranged from 0.444 [66] to 0.897 [31]. Only two studies reported HSUVs associated with severity levels, in which HSUVs for mild ADHD were 0.71 and 0.787, for severe ADHD 0.48 and 0.444 [27, 66]. HSUVs reported for anxiety disorders ranged from 0.62 [53] to 0.88 [32], and for depression from 0.495 [34] to 0.81 [57]. HSUVs for post-traumatic stress disorder range between 0.70 [52, 64] to 0.755 [60], for borderline personality disorder from 0.236 [38] to 0.49 [63]. HSUVs associated with undefined psychiatric disorders ranged from 0.5 [39] to 0.782 [25], for psychosis from 0.7992 [47] to 0.80 [46], for self-harming from 0.57 to 0.68 [28], for alcohol use from 0.82 [45] to 0.73 [24], for conduct disorders from 0.11 [43] to 0.802 [25], and for general MHPs from 0.56 [54] to 0.804 [59].

HSUVs for the following MHPs were derived from only one study each where HSUVs associated with internalising problems were 0.71 [50], with medicine use and delinquency in adolescents with MHPs being 0.81 and 0.82, respectively [45]. Furthermore, HSUVs of 0.49 were reported for avoidant personality disorder, 0.70 for personality disorder not otherwise specified, 0.34 for depressive personality disorder, 0.50 for obsessive–compulsive personality disorder [63], 0.52 for oppositional defiant disorder [43], 0.54 for suicide ideation [24].

Across MAUIs, Fig. 3 shows that the generated HSUVs vary significantly among the most frequently explored types of MHPs while the variations could not be overserved obviously in MHPs explored by fewer studies (n < 3). Specifically, CHU9D yielded generally higher mean HSUV scores while HUI2 and HUI3 yielded lower scores than other MAUIs in ADHD. Interestingly, EQ-5D-3L generated the widest range of HSUVs from the lowest HSUV of 0.495 [34, 57] to the highest of 0.81 among all included scores in depression. Similarly, CHU9D generated both the lowest HSUV of 0.62 [53] to the highest HSUV of 0.88 [32] in anxiety disorders.

A wide variation in reported HSUVs between self- and proxy-report was also observed (Supplementary Document 3). While self-reported HSUVs for anxiety disorders vary significantly, most of them (ranging from 0.62 [53] to 0.87 [32]) are general lower than proxy-reported HSUVs (0.85 [32]). In contrast, proxy-reported HSUVs for undefined psychiatric disorders are generally higher than self-reported ones. In conduct disorders, proxy-reported HSUVs were generally higher than self-reported ones except for one proxy-reported HSUV being the lowest score [43]. Among all included MHPs, depression has the widest range of HSUVs which were all derived from self-report.

A meta-analysis was considered inappropriate given the heterogeneity of reported HSUVs caused by different elicitation methods and MAUIs used, scoring algorithms, age range, country of research, and study designs.

Psychometric performance

Only nine studies assessed the psychometric performance of MAUIs used in youth mental health population in which five studies assessed EQ-5D-3L [35, 40, 56, 57, 61], two studies assessed EQ-5D-5L [26, 64], two studies assessed CHU9D [55, 59], and two studies [56, 57] assessed four MAUIs (EQ-5D-3L, QWB, SF-6D, HUI2 and HUI3). Table 3 reports the positive evidence, mixed evidence and no evidence for each psychometric property per MAUI, followed by the clinical population assessed.

Table 3.

Psychometric performance

| Study reference | Type of disorder tested | N | Age | Algorithm | Perspectives | Discriminant validity | Convergent validity | Responsiveness | Feasibility | Test–retest reliability | Internal consistency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EQ-5D-3L | |||||||||||

| Matza, 2005 [61] | ADHD | 126 | 7–18 | UK (adults) | Proxy-report (parent) | Y | Y | ||||

| Bouwmans, 2014 [40] | ADHD | 6–18 | Dutch (adults) | Proxy (parent) | Y | Y | |||||

| Byford, 2013 [35] | Depression | 199 | 11–17 | UK (adults) | Self-report | Y | + - | Y | |||

| Lynch, 2016 | Depression | 392 | 13–17 | NA | Self-report | Y | |||||

| Dickerson, 2018 [57] | Depression | 376 | 13–17 | NA | Self-report | Y | Y | ||||

| EQ-5D-5L | |||||||||||

| Dams, 2021 [64] | PTSD | 87 | 14–21 | German (adults) | Self-report | Y | Y | N | Y | ||

| EQ-5D-Y-5L | |||||||||||

| Astrom, 2020 [26] | Psychiatric disorders | 52 | 13–17 | Dimension | Self-report | Y | + - | Y | |||

| CHU9D | |||||||||||

| Furber, 2015 [55] | MHPs | 200 | 5–17 | UK (adults) and Australian (Adolescents) tariffs | Proxy report (caregivers) | Y | Y | ||||

| Wolf, 2021 [59] | MHPs | 396 | 6–15 | UK (adults) and Australian (Adolescents) tariffs | Proxy (parent) | Y | Y | Y | |||

| QWB | |||||||||||

| Lynch, 2016 | Depression | 392 | 13–17 | Canada | Self-report | Y | |||||

| Dickerson, 2018 [57] | Depression | 376 | 13–17 | Canada | Self-report | Y | Y | ||||

| SF-6D | |||||||||||

| Lynch, 2016 | Depression | 392 | 13–17 | UK (adults) | Self-report | +− | |||||

| Dickerson, 2018 [57] | Depression | 376 | 13–17 | UK (adults) | Self-report | Y | Y | ||||

| HUI3 | |||||||||||

| Lynch, 2016 | Depression | 392 | 13–17 | Canada | Self-report | Y | |||||

| Dickerson, 2018 [57] | Depression | 376 | 13–17 | Canada | Self-report | Y | Y | ||||

| HUI2 | |||||||||||

| Lynch, 2016 | Depression | 392 | 13–17 | Canada | Self-report | Y | |||||

| Dickerson, 2018 [57] | Depression | 376 | 13–17 | Canada | Self-report | Y | Y | ||||

Y: psychometric performance was significant, N: Psychometric performance was not significant, +−: Psychometric performance was inclusive

MHPs General mental health problems

No study assessed all psychometric properties investigated in this review. Overall, seven studies assessed discriminant validity, six studies assessed convergent validity, five studies assessed responsiveness, one study each assessed test–retest validity and feasibility. Three studies assessed the psychometric performance of MAUIs using proxy-report while six studies used self-report.

For EQ-5D-3L, the review found evidence of discriminating validity, convergent validity and responsiveness from both self-report [35, 56, 57] and proxy (parent) report [40, 61]. Whilst there is evidence of the discriminant validity, convergent validity, test–retest validity and feasibility in using EQ-5D-5L for youth population with mental health [64], the review did not find evidence of responsiveness for EQ-5D-5L [64]. For EQ-5D-Y-5L, one study using self-report showed evidence to support its feasibility, discriminant validity, and test–retest validity, however, the evidence of its convergent validity is mixed [26]. Regarding CHU9D, two included studies using proxy-report (parent) found evidence of the discriminant validity, convergent validity, internal consistency, and responsiveness of the dimensions of CHU9D [55, 59]. One study also provided evidence of the discriminant validity, convergent validity, and responsiveness of CHU9D using both UK (adults) and Australian (adolescents) algorithms [59]. For QWB, SF-6D, HUI2&3, the review found that these MAUIs have discriminant validity, convergent validity, and responsiveness [56, 57].

Discussion

This paper, for the first time, provided a systematic review of evidence on (1) the HSUVs of various MHPs, (2) the current practice to generate HSUVs, and (3) the psychometric performance of MAUIs used in children and youths with MHPs. The review found 38 studies reporting HSUVs for 12 types of MHPs in children and youths aged between 4 and 25 years across 12 countries between 2005 and October 2021. Among 12 types of MHPs reported in the review, depression and ADHD are the most explored MHPs, with 10 studies each. Overall, the review found that Disruptive Behaviour disorder has the lowest HSUV of 0.06 from children in primary education valuing vignettes in a cross-sectional study [43] while cannabis use disorder was associated with the highest HSUVs of 0.88 from an intervention study [44]. Moreover, the indirect valuation method using MAUIs (used in 95% of included studies) is the most frequently used approach to generate HSUVs for all 12 MHPs while only two studies using the direct valuation method was focused on ADHD. Of the ten MAUIs found in this review, the most frequently used was EQ-5D-3L, used in 15 out of 38 studies across eight out of 12 types of MHPs. CHU9D, the only MAUIs developed for use in childhood specific populations was used in 13 out of 38 studies across seven out of 12 MHPs. However, the review found no measure that has sufficient evidence of psychometric performance in children and youths with MHPs.

Heterogeneity was noticeable across the included studies. The variations, mainly caused by different elicitation methods and MAUIs used, scoring algorithms, age range, country of research, and study designs, have made it difficult to derive an estimate of the overall effect. For example, using samples of 11–17 years old adolescents at risk of self-harm, one study reported an HSUV of 0.68 using EQ-5D-3L with the UK adult tariff [28] while another study reported an HSUV of 0.57 using CHU9D with the Australian adolescent tariff [24]. Even using the same clinical sample, different MAUIs produced different HSUVs, for example, an HSUV of 0.56 derived from HUI3 while an HSUVs of 0.81 from EQ-5D-3L based on the same sample of adolescents with depression [57]. These findings are consistent with results from adult literature where different MAUIs produced different scores even in the same person [67]. Furthermore, only one study reports the populations norms for several MHPs [24], none of studies compared HSUVs with their corresponding populations norms. Thus, future research may benefit from such comparison.

We found some MAUIs were used for samples with the age range different from their recommended age range. Specifically, EQ-5D-3L, an adult-specific MAUI, was used in children aged as young as 4 years through proxy-report [31] or as young as 8 years old using self-report [41]. While the recommended ages for 16D are 12–15 years [10], the review found that the 16D was used in adolescents as young as 10 years old [60] or as old as 22 years [48]. We noted that studies may use measures for sample outside of the recommended age range as a way to save time and resources, or to facilitate comparisons across different age groups. However, transitioning between child and adolescent/youth populations can be challenging as there are significant developmental differences between these age groups [68]. Therefore, we urge future research to consider the potential limitations and accuracies that may result from this approach.

This review found limited evidence of the psychometric performance of MAUIs used in children and youths with MHPs with only nine studies covering eight MAUIs in five types of MHPs. Of these MAUIs, more studies assessed the psychometric performance of EQ-5D-3L than other measures. Only CHU9D was assessed using a sample with general MHPs while other MAUIs were assessed using a specific MHP samples. Specifically, EQ-5D-3L was assessed in ADHD and depression, EQ-5D-5L was assessed in PTSD, EQ-5D-Y-5L was assessed in psychiatric disorders, and QWB, SF-6D, HUI2&HUI3 were assessed in depression. Furthermore, we found that MAUIs were used in MHPs where evidence on their psychometric performance is lacking, such as the use of EQ-5D-3L in personality disorder [38, 63], behaviour disorders [43], substance used [44, 45, 65] and psychiatric disorders [39].

Evidence on the psychometric performance of MAUIs used in children and youths with MHPs is not conclusive, which makes it difficult to recommend one MAUI over another. Although the best psychometric evidence exists for EQ-5D-3L and CHU9D in terms of discriminant validity, convergent validity and responsiveness, other psychometric properties remain unclear. For example, both CHU9D and EQ-5D-3L have not been assessed regarding their feasibility, test–retest reliability, and interrater reliability. The evidence of other MAUIs was found either mixed or limited in number of studies and type of MHPs explored. Specifically, EQ-5D-5L was found to lack responsiveness while EQ-5D-Y-5L showed inconsistencies in its ability to converge with other measures. Although the psychometric performance of EQ-5D-5L and EQ-5D-Y-5L may look alarming, it is worth noting that the evidence was derived from one study per measure with small samples less than 100 which may limit the statistical power of the results. The findings on the convergent and discriminant validity of EQ-5D-3L, SF-6D and HUI3 in adolescents with depression align with findings in the adult depression literature [14, 15]. The limited evidence in terms of type of MHPs explored, extensive psychometric properties, number of studies with sufficient samples urges further research to provide comprehensive picture of the psychometric properties of all measures used in children and youths with MHPs.

Indeed, various aspects of MAUI psychometric assessments need further attention. Specifically, we found limited or no evidence in test–retest reliability, internal consistency, and interrater reliability of MAUIs. Various validity tests such as face validity and content validity would also contribute to more conclusive evidence of the psychometric performance of MAUIs in children and youths with MHPs. Lastly, although MAUIs were used across different countries using different languages, the review noted that the cultural validity of MAUIs has not been investigated.

Limitations of our study include the inability to conduct a meta-analysis of reported HSUVs due to the heterogeneity of the included studies and the small number of studies per MHP, which would otherwise provide an overview picture of the impact of MHPs on HSUVs and the associated disease burden [22]. Non-English studies and grey literature were excluded, which may limit the comprehensiveness of our review. Furthermore, following previous systematic reviews [10, 11, 19, 23], we did not conduct quality assessment of the included studies as well as the appropriateness of the statistical analyses undertaken in included studies, however results of included studies were discussed in consideration of sample sizes.

Conclusion

This review provides an overview of HSUVs of various MHPs, the current practice to generate HSUV, and the psychometric performance of MAUIs used in children and youths with MHPs. We report limited evidence on the psychometric performance of MAUIs in terms of psychometric properties assessed, type of MHPs explored, number of studies per measure and sufficient sample sizes. This highlights the need for more rigorous and extensive psychometric assessments to produce conclusive evidence on the suitability of MAUIs used in this area.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions. Million Minds Mission funding [GNT 1179461 2019–2023] Bringing family, community, culture and country to the centre of health care: culturally appropriate models for improving mental health and wellbeing in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people. The funder had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Data availability statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Child and adolescent mental health. https://www.who.int/activities/improving-the-mental-and-brain-health-of-children-and-adolescents (Accessed 08 Jan 2022).

- 2.Australia. Department of and Ageing. Guidelines for preparing submissions to the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee [electronic resource]/Department of Health and Ageing. PANDORA electronic collection. https://nla.gov.au/nla.cat-vn3960721 (Dept. of Health and Ageing, 2006).

- 3.World Health Organization. Adolescent mental health.

- 4.Erskine HE, Moffitt TE, Copeland WE, Costello EJ, Ferrari AJ, Patton G, Degenhardt L, Vos T, Whiteford HA, Scott JG. A heavy burden on young minds: The global burden of mental and substance use disorders in children and youth. Psychological Medicine. 2015;45(7):1551–1563. doi: 10.1017/s0033291714002888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Institute for Health Care Excellence . Guide to the methods of technology appraisal 2013. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE); 2013. NICE process and methods guides. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Drummond MF. Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes. 4. Oxford University Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brazier J, Ratcliffe J, Saloman J, Tsuchiya A. Measuring and valuing health benefits for economic evaluation. Oxford University Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 8. (2020). Health of Young People. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-health/health-of-young-people(online).

- 9.Patel V, Flisher AJ, Hetrick S, McGorry P. Mental health of young people: A global public-health challenge. Lancet. 2007;369(9569):1302–1313. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(07)60368-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rowen D, Rivero-Arias O, Devlin N, Ratcliffe J. Review of valuation methods of preference-based measures of health for economic evaluation in child and adolescent populations: Where are we now and where are we going? PharmacoEconomics. 2020;38(4):325–340. doi: 10.1007/s40273-019-00873-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hill H, Rowen D, Pennington B, Wong R, Wailoo A. A review of the methods used to generate utility values in NICE technology assessments for children and adolescents. Value in Health. 2020;23(7):907–917. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2020.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Krugten FCW, Feskens K, Busschbach JJV, Hakkaart-van Roijen L, Brouwer WBF. Instruments to assess quality of life in people with mental health problems: A systematic review and dimension analysis of generic, domain- and disease-specific instruments. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2021;19(1):249. doi: 10.1186/s12955-021-01883-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Papaioannou, D., Brazier, J., & Parry, G. (2011). How valid and responsive are generic health status measures, such as EQ-5D and SF-36, in schizophrenia? A systematic review. Value in Health, 14(6), 907–920. 10.1016/j.jval.2011.04.006(in English). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Mulhern B, Mukuria C, Barkham M, Knapp M, Byford S, Soeteman D, Brazier J. Using generic preference-based measures in mental health: Psychometric validity of the EQ-5D and SF-6D. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2014;205(3):236–243. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.112.122283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brazier, J., Connell, J., Papaioannou, D., Mukuria, C., Mulhern, B., Peasgood, T., Jones, M. L., Paisley, S., O'Cathain, A., Barkham, M., Knapp, M., Byford, S., Gilbody, S., & Parry, G. (2014). A systematic review, psychometric analysis and qualitative assessment of generic preference-based measures of health in mental health populations and the estimation of mapping functions from widely used specific measures. Health Technology Assessment, 18(34), vii–viii, xiii–xxv, 1–188. 10.3310/hta18340 (in English). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JPA, Clarke M, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: Explanation and elaboration. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.) 2009;339:b2700. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Autistic Society. Metal Health. https://www.autism.org.uk/advice-and-guidance/topics/mental-health

- 18.Health Direct. Autism. https://www.healthdirect.gov.au/autism#:~:text=Autism%20is%20NOT%20a%20mental%20illness%2C%20though%20people%20with%20autism,such%20as%20depression%20and%20anxiety

- 19.Kwon J, Kim SW, Ungar WJ, Tsiplova K, Madan J, Petrou S. A systematic review and meta-analysis of childhood health utilities. Medical Decision Making. 2018;38(3):277–305. doi: 10.1177/0272989X17732990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Ijzendoorn MH, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ. Problematic cost-utility analysis of interventions for behavior problems in children and adolescents. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development. 2020;172:89–102. doi: 10.1002/cad.20360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australia's youth. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/children-youth/australias-youth/contents/introduction#scope

- 22.Peasgood T, Brazier J. Is meta-analysis for utility values appropriate given the potential impact different elicitation methods have on values? PharmacoEconomics. 2015;33(11):1101–1105. doi: 10.1007/s40273-015-0310-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rowen D, Keetharuth AD, Poku E, Wong R, Pennington B, Wailoo A. A review of the psychometric performance of selected child and adolescent preference-based measures used to produce utilities for child and adolescent health. Value in Health. 2021;24(3):443–460. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2020.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Le LK-D, Richards-Jones S, Chatterton ML, Engel L, Lawrence D, Stevenson C, Pepin G, Ratcliffe J, Sawyer M, Mihalopoulos C. Australian adolescent population norms for the child health utility index 9D-results from the young minds matter survey. Quality of Life Research. 2021;30(10):2895–2906. doi: 10.1007/s11136-021-02864-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Petrou S, Johnson S, Wolke D, Hollis C, Kochhar P, Marlow N. Economic costs and preference-based health-related quality of life outcomes associated with childhood psychiatric disorders. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;197(5):395–404. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.081307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Astrom, M., Krig, S., Ryding, S., Cleland, N., Rolfson, O. & Burstrom, K. (2020). EQ-5D-Y-5L as a patient-reported outcome measure in psychiatric inpatient care for children and adolescents—A cross-sectional study. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes,18(1), 164. 10.1186/s12955-020-01366-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Matza LS, Secnik K, Rentz AM, Mannix S, Sallee FR, Gilbert D, Revicki DA. Assessment of health state utilities for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children using parent proxy report. Quality of Life Research. 2005;14(3):735–747. doi: 10.1007/PL00022070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tubeuf, S., Saloniki, E. C., & Cottrell, D. (2019). Parental health spillover in cost-effectiveness analysis: evidence from self-harming adolescents in England. PharmacoEconomics, 37(4), 513–530. 10.1007/s40273-018-0722-6 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Peasgood T, Bhardwaj A, Biggs K, Brazier JE, Coghill D, Cooper CL, Daley D, De Silva C, Harpin V, Hodgkins P, Nadkarni A, Setyawan J, Sonuga-Barke EJS. The impact of ADHD on the health and well-being of ADHD children and their siblings. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2016;25(11):1217–1231. doi: 10.1007/s00787-016-0841-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Secnik K, Matza LS, Cottrell S, Edgell E, Tilden D, Mannix S. Health state utilities for childhood attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder based on parent preferences in the United kingdom. Medical Decision Making. 2005;25(1):56–70. doi: 10.1177/0272989X04273140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sayal, K., Taylor, J. A., Valentine, A., Guo, B., Sampson, C. J., Sellman, E., James, M., Hollis, C., & Daley, D. (2016). Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of a brief school-based group programme for parents of children at risk of ADHD: A cluster randomised controlled trial. Child: Care, Health and Development,42(4), 521–533. 10.1111/cch.12349(in English). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Creswell C, Violato M, Fairbanks H, White E, Parkinson M, Abitabile G, Leidi A, Cooper PJ. Clinical outcomes and cost-effectiveness of brief guided parent-delivered cognitive behavioural therapy and solution-focused brief therapy for treatment of childhood anxiety disorders: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet Psychiatry. 2017;4(7):529–539. doi: 10.1016/s2215-0366(17)30149-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Turner D, Carter T, Sach T, Guo B, Callaghan P. Cost-effectiveness of a preferred intensity exercise programme for young people with depression compared with treatment as usual: An economic evaluation alongside a clinical trial in the UK. British Medical Journal Open. 2017;7(11):e016211. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Byford S, Barrett B, Roberts C, Wilkinson P, Dubicka B, Kelvin RG, White L, Ford C, Breen S, Goodyer I. Cost-effectiveness of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and routine specialist care with and without cognitive behavioural therapy in adolescents with major depression. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;191:521–527. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.038984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Byford, S. (2013). The validity and responsiveness of the EQ-5D measure of health-related quality of life in an adolescent population with persistent major depression. Journal of Mental Health (Abingdon, England),22(2), 101–110. 10.3109/09638237.2013.779366 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Wright B, Tindall L, Littlewood E, Allgar V, Abeles P, Trepel D, Ali S. Computerised cognitive-behavioural therapy for depression in adolescents: Feasibility results and 4-month outcomes of a UK randomised controlled trial. British Medical Journal Open. 2017;7(1):e012834. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goodyer IM, Reynolds S, Barrett B, Byford S, Dubicka B, Hill J, Holland F, Kelvin R, Midgley N, Roberts C, Senior R, Target M, Widmer B, Wilkinson P, Fonagy P. Cognitive-behavioural therapy and short-term psychoanalytic psychotherapy versus brief psychosocial intervention in adolescents with unipolar major depression (IMPACT): A multicentre, pragmatic, observer-blind, randomised controlled trial. Health Technology Assessment. 2017;21(12):1–94. doi: 10.3310/hta21120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zyoud, S. E., Waring, W. S., Al-Jabi, S. W., Sweileh, W. M., & Awang, R. (2016). Health related quality of life for young people receiving dialectical behaviour therapy (DBT): A routine outcome-monitoring pilot. SpringerPlus,5(1), 1137. 10.1186/s40064-016-2826-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Ougrin D, Corrigall R, Poole J, Zundel T, Sarhane M, Slater V, Stahl D, Reavey P, Byford S, Heslin M, Ivens J, Crommelin M, Abdulla Z, Hayes D, Middleton K, Nnadi B, Taylor E. Comparison of effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of an intensive community supported discharge service versus treatment as usual for adolescents with psychiatric emergencies: A randomised controlled trial. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(6):477–485. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30129-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bouwmans, C. (2014). Validity and responsiveness of the EQ-5D and the KIDSCREEN-10 in children with ADHD. European Journal of Health Economics,15(9), 967–977. https://ezproxy.deakin.edu.au/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=ip,sso&db=ecn&AN=1472714&site=ehost-live&scope=site10.1007/s10198-013-0540-x(online). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Bodden, D. H. M., Dirksen, C. D., Bögels, S. M., Nauta, M. H., De Haan, E., Ringrose, J., Appelboom, C., Brinkman, A. G., & Appelboom-Geerts, K. C. M. M. J. (2008). Costs and cost-effectiveness of family CBT versus individual CBT in clinically anxious children. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry,13(4), 543–564. 10.1177/1359104508090602 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.De Bruin, E. J., van Steensel, F. J. A. & Meijer, A. M. (2016). Cost-effectiveness of group and internet cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia in adolescents: Results from a randomized controlled trial. Sleep,39(8), 1571–1581. 10.5665/sleep.6024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Vermeulen KM, Jansen DE, Buskens E, Knorth EJ, Reijneveld SA. Serious child and adolescent behaviour disorders; A valuation study by professionals, youth and parents. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17(1):208. doi: 10.1186/s12888-017-1363-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Goorden, M., Van Der Schee, E., Hendriks, V. M., & Hakkaart-van Roijen, L. (2016). Cost-effectiveness of multidimensional family therapy for adolescents with a cannabis use disorder. Journal of Mental Health Policy and Economics, 18, S17. https://www.embase.com/search/results?subaction=viewrecord&id=L72236016&from=export(online). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Reckers-Droog, V., Goorden, M., Kaminer, Y., van Domburgh, L., Brouwer, W., & Hakkaart-van Roijen, L. (2020). Presentation and validation of the Abbreviated Self Completion Teen-Addiction Severity Index (ASC T-ASI): A preference-based measure for use in health-economic evaluations. PLoS One,15(9), e0238858. 10.1371/journal.pone.0238858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Grano N, Kallionpaa S, Karjalainen M, Edlund V, Saari E, Itkonen A, Anto J, Roine M. Lower functioning predicts identification of psychosis risk screening status in help-seeking adolescents. Early Intervention in Psychiatry. 2015;9(5):363–369. doi: 10.1111/eip.12118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Grano N, Karjalainen M, Edlund V, Saari E, Itkonen A, Anto J, Roine M. Changes in health-related quality of life and functioning ability in help-seeking adolescents and adolescents at heightened risk of developing psychosis during family- and community-oriented intervention model. International Journal of Psychiatry in Clinical Practice. 2013;17(4):253–258. doi: 10.3109/13651501.2013.784791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Grano N, Karjalainen M, Edlund V, Saari E, Itkonen A, Anto J, Roine M. Health-related quality of life among adolescents: A comparison between subjects at risk for psychosis and other help seekers. Early Intervention in Psychiatry. 2014;8(2):163–169. doi: 10.1111/eip.12033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Garmy, P., Clausson, E. K., Berg, A., Steen Carlsson, K. & Jakobsson, U. (2019). Evaluation of a school-based cognitive-behavioral depression prevention program. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health,47(2), 182–189. 10.1177/1403494817746537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Philipsson A, Duberg A, Moller M, Hagberg L. Cost-utility analysis of a dance intervention for adolescent girls with internalizing problems. Cost Effectiveness and Resource Allocation. 2013;11(1):4. doi: 10.1186/1478-7547-11-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Weigel K, Konig HH, Gumz A, Lowe B, Brettschneider C. Correlates of health related quality of life in anorexia nervosa. The International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2016;49(6):630–634. doi: 10.1002/eat.22512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dams J, Rimane E, Steil R, Renneberg B, Rosner R, Konig H-H. Health-related quality of life and costs of posttraumatic stress disorder in adolescents and young adults in Germany. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2020;11(101545006):697. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chatterton ML, Rapee RM, Catchpool M, Lyneham HJ, Wuthrich V, Hudson JL, Kangas M, Mihalopoulos C. Economic evaluation of stepped care for the management of childhood anxiety disorders: Results from a randomised trial. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2019;53(7):673–682. doi: 10.1177/0004867418823272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Le, L. K. D., Sanci, L., Chatterton, M. L., Kauer, S., Buhagiar, K., & Mihalopoulos, C. The cost-effectiveness of an internet intervention to facilitate mental health help-seeking by young adults: Randomized controlled trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research,21(7), e13065. 10.2196/13065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 55.Furber F, Segal L. The validity of the Child Health Utility instrument (CHU9D) as a routine outcome measure for use in child and adolescent mental health services. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2015;13(101153626):22. doi: 10.1186/s12955-015-0218-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lynch, F. L., Dickerson, J. F., Feeny, D. H., Clarke, G. N., & MacMillan, A. L. (2016). Measuring health-related quality of life in teens with and without depression. Medical Care, 54(12), 1089–1097. https://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/wk/mcar/2016/00000054/00000012/art00012;jsessionid=5420vtwxmk3s.x-ic-live-02(online). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 57.Dickerson JF, Feeny DH, Clarke GN, Macmilan AL, Lynch FL. Evidence on the longitudinal construct validity of major generic and utility measures of health-related quality of life in teens with depression. Quality of Life Research. 2018;27(2):447–454. doi: 10.1007/s11136-017-1728-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Maia CR, Stella SF, Wagner F, Pianca TG, Krieger FV, Cruz LN, Polanczyk GV, Rohde LA, Polanczyk CA. Cost-utility analysis of methylphenidate treatment for children and adolescents with ADHD in Brazil. Brazilian Journal of Psychiatry. 2016;38(1):30–38. doi: 10.1590/1516-4446-2014-1516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wolf RT, Ratcliffe J, Chen G, Jeppesen P. The longitudinal validity of proxy-reported CHU9D. Quality of Life Research. 2021;30(6):1747–1756. doi: 10.1007/s11136-021-02774-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Aas, E., Iversen, T., Holt, T., Ormhaug, S. M., & Jensen, T. K. (2019). Cost-effectiveness analysis of trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy: A randomized control trial among Norwegian youth. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 48(1), 298–311. 10.1080/15374416.2018.1463535 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 61.Matza, L. S., Secnik, K., Mannix, S. & Sallee, F. R. (2005). Parent-proxy EQ-5D ratings of children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in the US and the UK. PharmacoEconomics, 23(8), 777–790. 10.2165/00019053-200523080-00004.pdf(online). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 62.EuroQol—A new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy (Amsterdam, Netherlands), 16(3), 199–208. 10.1016/0168-8510(90)90421-9(in English). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 63.Feenstra DJ, Hutsebaut J, Laurenssen EM, Verheul R, Busschbach JJ, Soeteman DI. The burden of disease among adolescents with personality pathology: Quality of life and costs. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2012;26(4):593–604. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2012.26.4.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dams J, Rimane E, Steil R, Renneberg B, Rosner R, Konig HH. Reliability, validity and responsiveness of the EQ-5D-5L in assessing and valuing health status in adolescents and young adults with posttraumatic stress disorder: A randomized controlled trail. The Psychiatric Quarterly. 2021;92(2):459–471. doi: 10.1007/s11126-020-09814-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Vargas-Martinez, A. M., Trapero-Bertran, M., Lima-Serrano, M., Anokye, N., Pokhrel, S. & Mora, T. (2019). Measuring the effects on quality of life and alcohol consumption of a program to reduce binge drinking in Spanish adolescents. Drug Alcohol Dependence,205(7513587), 107597. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.107597 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 66.Lloyd A, Hodgkins P, Sasane R, Akehurst R, Sonuga-Barke EJ, Fitzgerald P, Nixon A, Erder H, Brazier J. Estimation of utilities in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder for economic evaluations. The Patient. 2011;4(4):247–257. doi: 10.2165/11592150-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mihalopoulos C, Chen G, Iezzi A, Khan MA, Richardson J. Assessing outcomes for cost-utility analysis in depression: Comparison of five multi-attribute utility instruments with two depression-specific outcome measures. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2014;205(5):390–397. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.113.136036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education; Board on Children, Youth, and Families; Committee on the Neurobiological and Socio-behavioral Science of Adolescent Development and Its Applications . In: The Promise of Adolescence: Realizing Opportunity for All Youth. Backes EP, Bonnie RJ, editors. National Academies Press; 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.