Abstract

Up to now, the only species in the complex Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato known to cause Lyme borreliosis in the United States has been B. burgdorferi sensu stricto. However, some atypical strains closely related to the previously designated genomic group DN127 have been isolated in the United States, mostly in California. To explore the diversity of B. burgdorferi sensu lato group DN127, we analyzed the nucleotide sequences of the rrf-rrl intergenic spacer regions from 19 atypical strains (18 from California and one from New York) and 13 North American B. burgdorferi sensu stricto strains (6 from California). The spacer region sequences from the entire B. burgdorferi sensu lato complex available in data banks were used for comparison. Phylogenetic analysis of sequences shows that the main species of the B. burgdorferi sensu lato complex (B. afzelii, B. garinii, B. andersonii, B. japonica, B. burgdorferi sensu stricto, B. valaisiana, and B. lusitaniae) each form a coherent cluster. A heterogeneous group comprising strains belonging to the previously designated group DN127 clustered separately from B. burgdorferi sensu stricto. Within this cluster, the deep branches expressing the distances between the rrf-rrl sequences reflect a high level of divergence. This unexpected diversity contrasts with the monomorphism exhibited by B. burgdorferi sensu stricto. To clarify the taxonomic status of this highly heterogeneous group, analysis of the rrs sequences of selected strains chosen from deeply separated branches was performed. The results show that these strains significantly diverge at a level that is compatible with several distinct genomic groups. We conclude that the taxonomy and phylogeny of North American B. burgdorferi sensu lato should be reevaluated. For now, we propose that the genomic group DN127 should be referred to as a new species, B. bissettii sp. nov., and that other related but distinct strains, which require further characterization, be referred to as Borrelia spp.

In Eurasia, seven species of the complex Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato have been reported. Only three of these species are associated with Lyme borreliosis. It has also been shown that each pathogenic species is associated predominantly with a given clinical presentation; Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto is associated with arthritis, B. garinii is associated with neuroborreliosis, and B. afzelii is associated with late cutaneous symptoms (2, 39). Up to now, B. burgdorferi sensu stricto is the only species associated with Lyme borreliosis in North America. However, two other B. burgdorferi sensu lato genospecies coexist in the United States, B. andersonii (22) and the genomic group DN127 (3, 32). B. andersonii seems to be restricted to a limited ecosystem involving cottontail rabbits and Ixodes dentatus ticks. In contrast, the genomic group DN127 appears to be involved in several enzootic transmission cycles (6, 29). A recent study demonstrated substantial genetic heterogeneity among Californian and other American strains (24). We took advantage of the unique structure of ribosomal genes in B. burgdorferi sensu lato to analyze the polymorphism of some strains isolated in California. A single copy of the rrs gene is separated by a large spacer (rrs-rrl; 3,000 to 5,000 bp) from two tandemly duplicated copies of rrl and rrf genes (13, 36). These two copies are separated by a small spacer, rrf-rrl, which is approximately 250 bp long. The genetic heterogeneity of the group DN127 was first evidenced by analysis of the restriction patterns of the rrf-rrl spacer (32). However, the results of DNA-DNA hybridization on a limited number of strains (32) allowed us to place them in a single genomic group. To clarify the genetic relationships between diverse North American strains, 20 atypical strains were compared with 13 B. burgdorferi sensu stricto strains. Identification procedures involved restriction polymorphism and sequencing studies of both the variable rrf-rrl spacer and the conserved rrs gene. Sequences of the rrf-rrl spacer and the rrs gene were used in a phylogenetic analysis. Some Californian strains are closely related to the genomic group DN127, for which we propose the name of B. bissettii sp. nov. Other atypical strains which do not fall into this group are designated merely as Borrelia spp. in this study. The latter strains cannot be assigned to specific genomic groups until more isolates representative of each group are available for further characterization.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and DNA preparation.

The designations and origins of the Borrelia strains used in this study are given in Table 1. The uncloned strains were grown in BSK II medium at 30°C. DNA was extracted by using the Dynabeads DNA direct kit (Dynal), a method based on DNA separation by biomagnetic beads as previously described (17). DNA samples were stored at −20°C until use for PCRs.

TABLE 1.

B. burgdorferi sensu lato isolates evaluated in this study

| Strain | Accession no.

|

Source | Geographic location in the U.S. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rrf-rrl spacer | rrs gene | |||

| B. burgdorferi sensu stricto | ||||

| CA423 | AJ006361a | NAb | I. spinipalpis | California |

| CA19 (35)d | AJ006360a | AJ224137a | I. pacificus | California |

| B31T | L30127 | M59293 | I. scapularis | New York |

| VS2 | AJ006510a | NA | I. scapularis | Shelter Island |

| SON328 | AJ006512a | NA | I. pacificus | California |

| SON188 | AJ006511a | NA | I. pacificus | California |

| SON2110 | AJ006508a | NA | I. pacificus | California |

| MEN 115 | AJ006504a | NA | I. pacificus | California |

| NY1-86 | AJ006505a | NA | Human | New York |

| 297 | AJ006507a | X85204 | Human | Connecticut |

| 19535 | AJ006503a | NA | Peromyscus leucopus | New York |

| 26816 | AJ006506a | NA | Microtus pennsylvanicus | Rhode Island |

| Cat flea | AJ006509a | NA | Ctenocephalides felis | Tennessee |

| B. bissettii sp. nov. | ||||

| CA394 | AJ006359a | NA | I. spinipalpis | California |

| CA395 | AJ006363a | NA | I. spinipalpis | California |

| CA370 | AJ006364a | NA | Neotoma fuscipes | California |

| CA372 | AJ006370a | NA | N. fuscipes | California |

| CA378 | AJ006367a | NA | N. fuscipes | California |

| CA27 (35) | AJ006362a | NA | I. pacificus | California |

| DN127T (32) | L30126 | AJ224141a | I. pacificus | California |

| 25015 (32) | L30122 | AJ224138a | I. scapularis | New York |

| CA55 (32) | L30124 | AJ224140a | I. neotomaec | California |

| CA127 (32) | NA | NA | I. neotomae | California |

| CA128 (32) | AJ006365a | AJ224139a | I. neotomae | California |

| Borrelia spp. | ||||

| CA28 (35) | AJ006375a | AJ224131a | I. pacificus | California |

| CA29 (35) | AJ006373a | AJ224135a | I. pacificus | California |

| CA8 (35) | AJ006369a | AJ224134a | I. pacificus | California |

| CA31 (35) | AJ006372a | AJ224132a | I. pacificus | California |

| CA446 | AJ006366a | AJ224130a | Dipodomys californicus | California |

| CA443 | AJ006368a | NA | D. californicus | California |

| CA404 | AJ006371a | NA | D. californicus | California |

| CA13 (35) | AJ006374a | AJ224133a | I. neotomae | California |

| CA2 (32) | L30123 | AJ224136a | I. neotomae | California |

Sequences determined in this study.

NA, not available.

Now I. spinipalpis (27).

Numbers in parentheses indicate references.

Analysis of restriction patterns of rrf-rrl spacer and sequencing.

The restriction pattern analysis of amplified rrf-rrl spacer was performed by using primers 1 and 2 as described previously (32). MseI and DraI restriction patterns were used to compare the strains. The rrf-rrl spacer was sequenced by a solid-phase approach, using the Cy5-AutoRead sequencing kit with an ALF express automatic sequencer (Pharmacia) (17). To amplify the rrf-rrl spacer, we used primers A (5′-ATTACCCGTATCTTTGGC-3′) and D (5′-TCAATAAATGTTTGCTTCTC-3′), with one of the two primers biotinylated at the 5′ end. The biotinylated strand was then immobilized through the interaction between biotin and streptavidin by using the Dynabeads M-280 streptavidin kit (Dynal) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Sequencing was performed by using the sequencing primers INS1 (5′-GAAAAGAGGAAACACCTGTT-3′) in the rrf gene and INS4 (5′-AGCTCCTAGGCATTCACCAT-3′) at the 5′ end of the rrl gene.

rrs sequencing.

Amplification and sequencing of the rrs gene were done as previously described (17).

Sequence alignments and phylogenetic analysis.

Sequences were aligned both manually on VSM software V.2.0 written by B. Lafay and R. Christen (33) as described recently (10) and by using the multisequence alignment program Clustal V (10). Phylogenetic trees were constructed with distance matrix data (calculated by the method of Jukes of Cantor [14]) and both the neighbor-joining (NJ) method (34) and the unweighted pair group with mathematical average (UPGMA) (37) methods in MEGA software (15). A parsimony method in MEGA was used to analyze the rrf-rrl intergenic spacer sequences of select strains.

Characterization of the rrs-rrl spacer.

The size of the rrs-rrl spacer was determined after amplification by using primer S15 (5′-GGGCCTTGTACACACCGCCC-3′) at the 3′ end of rrs and primer INS4 as given above. The PCR mixture (50 μl) contained 10 ng of DNA in 5 μl, 50 mM Tris-HCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 20 mM NH4SO4, 200 μM each of the four deoxynucleoside triphosphates, 10 pmol of each primer, and 0.45 U of Hot Tub DNA polymerase (Amersham Life Science). The PCR was carried out for 30 cycles with an amplification profile of denaturation at 93°C for 15 s and then simultaneous annealing and extension at 60°C for 8 min, with a final extension step at 60°C for 10 min.

PCR products (10 μl) were digested with 5 U of HinfI (Biolabs) in a total volume of 20 μl. Digested fragments were analyzed by electrophoresis on a 1.2% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The nucleotide sequences of rrf-rrl spacer regions or rrs genes from B. burgdorferi sensu lato isolates have been deposited in EMBL data bank and assigned accession nos. AJ006359 to AJ006375, AJ006503 to AJ006512, and AJ224130 to AJ224141 (see Table 1).

RESULTS

Individualization of B. bissettii deduced from the analysis of the rrf-rrl spacer.

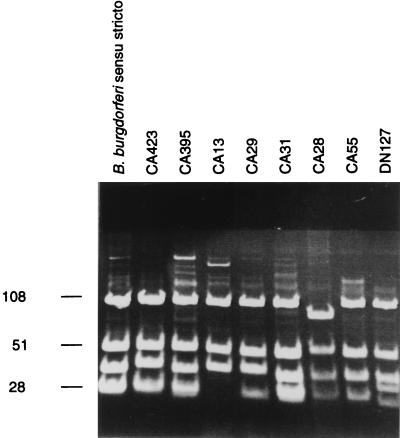

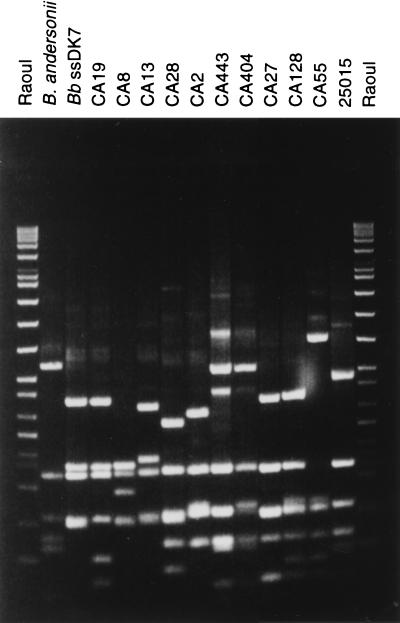

Analysis of MseI restriction patterns of amplification products of the spacer between the two tandem copies of the rrl-rrf ribosomal genes from North American strains revealed 11 different patterns (Table 2). These patterns were not identical to any of the patterns recorded previously for B. burgdorferi sensu lato species and genomic groups. However, they were very similar to the pattern of strains belonging to B. burgdorferi sensu stricto (Fig. 1). The analysis of patterns obtained after restriction by DraI confirmed this heterogeneity (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

MseI and DraI restriction fragments of amplified rrf-rrl spacer

| Strain(s) | Sizea (bp) of fragments produced by:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| MseI | DraI | |

| B. burgdorferi sensu stricto | ||

| B31T | 107, 52, 38, 29, 28 | 144, 53, 29, 28 |

| CA19, CA423 | 107, 52, 40, 29, 28 | 146, 53, 29, 28 |

| B. bissettii sp. nov. | ||

| DN127T, CA27, CA127, CA372, CA378, CA394 | 107, 52, 38, 33, 27 | 144, 53, 33, 27 |

| CA128, CA395 | 107, 52, 38, 29, 27 | 144, 53, 29, 27 |

| CA370 | 107, 53, 38, 28 | 144, 82 |

| CA55 | 107, 52, 38, 29 | 144, 53, 29 |

| 25015 | 107, 52, 34, 27, 17, 12, 4 | 174, 53, 27 |

| Borrelia spp. | ||

| CA2 | 90, 51, 40, 28, 22, 17, 7 | 146, 109 |

| CA31, CA404, CA443, CA446 | 107, 51, 37, 30, 28 | 173, 80 |

| CA8, CA29 | 107, 51, 40, 28, 16, 13 | 146, 80, 16, 13 |

| CA13 | 107, 52, 40, 17 | 146, 53, 17 |

| CA28 | 90, 54, 38, 29, 17 | 144, 55, 29 |

The exact sizes were deduced from rrf-rrl spacer sequences.

FIG. 1.

MseI restriction polymorphism of the amplified rrf-rrl spacer from Californian strains. DNA was electrophoresed on a 16% acrylamide gel, stained with ethidium bromide, and UV illuminated. The species assignment of strains is given in Table 1. The molecular sizes of DNA fragments (in base pairs) are shown to the left of the gel.

Some strains (CA27, CA372, CA378, and CA394) exhibited exactly the same pattern as strain DN127, the type strain of the previous genomic group DN127.

The rrf-rrl spacer region (32) of strains tested ranged from 216 to 257 bp. The percent identity in pairwise alignments of sequences from Borrelia spp. strains ranged from 85.3 to 100 (data not shown). However, all strains with identical MseI or DraI patterns exhibited 100% sequence identity, except strain CA404 which differed by one nucleotide from strains CA31, CA443, and CA446. To compare the polymorphism, the spacer regions from 10 American strains previously identified as B. burgdorferi sensu stricto were sequenced. In contrast with the extreme diversity in Borrelia spp., considerable homogeneity characterized the sequences of B. burgdorferi sensu stricto strains, as nucleotide substitutions or deletions occurred in only five positions.

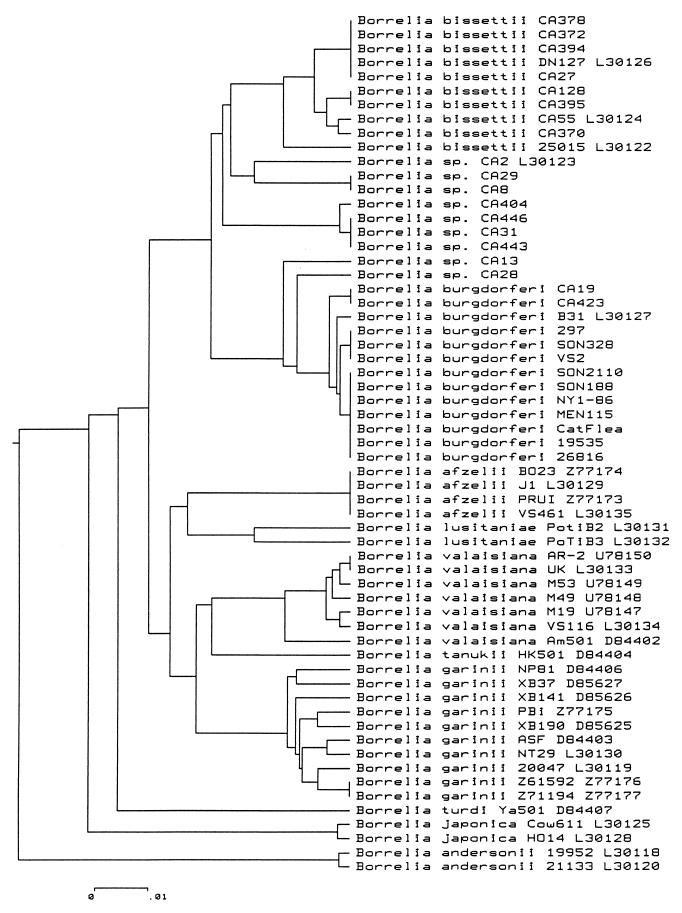

The NJ and UPGMA distance methods were used to construct phylogenetic trees from sequences obtained in this study. An example of a tree drawn by the UPGMA distance method is shown in Fig. 2. Each previous species, namely, B. garinii, B. afzelii, B. valaisiana, B. lusitaniae, B. tanukii, B. turdi, B. andersonii, and B. japonica, clustered separately. One large and heterogeneous cluster of 32 sequences comprises B. burgdorferi sensu stricto, the strains identified as belonging to B. bissettii sp. nov. (formerly the genomic group DN127, DN127, CA128, CA55, and 25015), and all strains with atypical MseI and DraI patterns (Borrelia spp.). Within this cluster, all strains belonging to B. burgdorferi sensu stricto are closely related, which contrasts with the strains of Borrelia spp. that are scattered on several branches. Among the atypical strains, two strains (CA19 and CA423), despite slight differences in their MseI patterns, fell into the B. burgdorferi sensu stricto cluster. Given the large diversity exhibited by the Borrelia spp., segregation of some strains did not correlate precisely with different trees drawn by phenetic (Fig. 2) or cladistic methods (data not shown). For example, the placement of strain CA2 was uncertain, as was the placement of strains CA29 and CA8, because they constituted a separate cluster comprising four distinct branches together with Californian strains CA404, CA443, CA446, and CA31 and B. andersonii in the tree drawn with the NJ distance method (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Phylogenetic tree based on a comparison of the rrf-rrl sequences of B. burgdorferi sensu lato. The branching pattern was generated by the UPGMA method. The bar represents 1% divergence.

However, the branch consisting of strains previously placed in the group DN127 (DN127, CA55, CA128, and 25015), and six additional strains (CA27, CA370, CA372, CA378, CA394, and CA395) was constant, irrespective of the method used to construct the trees.

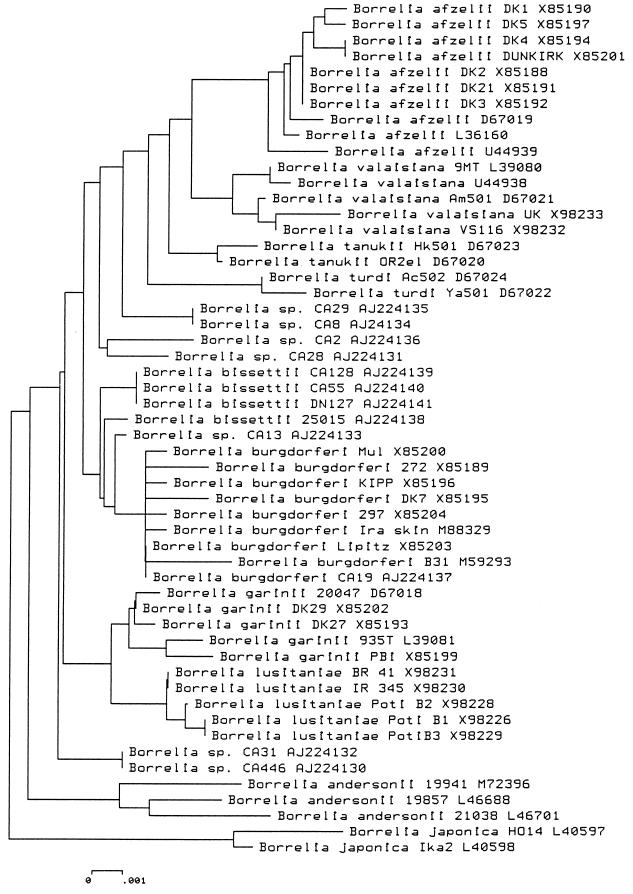

New genomic groups deduced from rrs sequences.

To provide an alternative assessment of phylogenetic relationships between such divergent strains, we sequenced the entire rrs gene from strains representing each of the main branches in the rrf-rrl trees. A phylogenetic tree showing the result of the NJ analysis of sequences is shown in Fig. 3. The assignment of strain CA19 in B. burgdorferi sensu stricto was confirmed. The results showed that strains of Borrelia spp. significantly diverge at a level compatible with distinct genomic groups. Strains CA31 and CA446 constituted one group. Strains CA8 and CA29 comprised another group. Strains CA2 and CA28 were located on two different branches according to the rrf-rrl sequence. They clustered together by rrs sequence, but their genetic distance is relatively large. The status of strain CA2 was not clear on the basis of DNA-DNA hybridization data (32). However, our present results suggest that strains CA2 and CA28 should constitute a new genomic group. Strains CA128, CA55, and 25015 segregated with strain DN127. Whether strain CA13 belong to the latter genomic group remains unknown. The clustering of strains of Borrelia spp. was consistent with that obtained by the UPGMA analysis (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Phylogenetic tree based on a comparison of the rrs sequences of B. burgdorferi sensu lato. The branching pattern was generated by the NJ method. The bar represents 0.1% divergence.

Polymorphism of the rrs-rrl spacer.

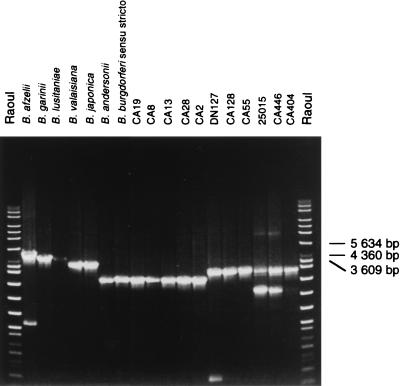

It has been shown previously that the size of the spacer between the rrs gene and the first copy of the rrl gene varied among different Borrelia species (28). The size of the rrs-rrl spacer allowed Borrelia species to be distinguished by decreasing size order from 5,000 bp for B. afzelii to 3,000 bp for B. burgdorferi sensu stricto and B. andersonii (Fig. 4). As shown in Fig. 4, strains evaluated in this work exhibited PCR products of two different sizes. All strains assigned to B. bissettii sp. nov. (DN127, CA55, 25015, CA27, CA394, CA395, CA370, CA372, and CA378), as well as four strains of Borrelia spp. (CA31, CA404, CA443, and CA446) exhibited a rrs-rrl spacer with an identical size of approximately 500 bp larger than that of B. burgdorferi sensu stricto. Other strains of Borrelia spp. had a rrs-rrl spacer whose size was the same as that of B. burgdorferi sensu stricto. The analysis of the HinfI restriction pattern of the rrs-rrl spacer PCR product has been proposed for typing of B. burgdorferi sensu stricto (18, 19). As described earlier (18), we also found two DNA fragment patterns among strains of B. burgdorferi sensu stricto. In contrast to these findings, a strong polymorphism was observed among atypical strains (Fig. 5). Ten distinctive patterns recorded from 17 atypical strains are shown in Fig. 5. Notably, the analyses of polymorphism of both the large rrs-rrl spacer and the small rrf-rrl spacer produced comparable groupings of strains.

FIG. 4.

PCR products of rrs-rrl spacer from B. burgdorferi sensu lato strains. The species assignment of strains is given in Table 1. Amplification was carried out by using the S15-INS4 primer set. DNAs were electrophoresed on a 0.6% agarose gel, stained with ethidium bromide, and UV illuminated. Molecular size standards Raoul (Appligene) were used.

FIG. 5.

Restriction patterns of Californian strains. The species assignment of strains is indicated in Table 1. DNAs from amplified rrs-rrl spacers were digested by HinfI. DNAs were electrophoresed on a 1.2% agarose gel, stained with ethidium bromide, and UV illuminated. Molecular size standards Raoul (Appligene) were used.

DISCUSSION

Since the first description of B. burgdorferi in 1982 (7), it has been assumed that strains in the United States were more homogeneous than the European strains (8, 9). However, an increasing number of atypical strains have been recognized in the United States, particularly in the 1990s (1, 5, 9, 12, 16, 21, 24, 35, 41, 42). Some of these strains were identified as belonging to the species B. andersonii (22), whereas others constituted a new genomic group called group DN127 (3, 32). Considerable phenotypic heterogeneity was found among strains described from California and Colorado (26, 35), and substantial genetic diversity was reported among a large number of North American strains (24) on the basis of genomic macrorestriction analysis and ospA and rrl gene sequencing. Our study emphasizes that the genetic diversity among American strains is much greater than previously thought.

Phylogenetic analyses of rrs gene sequences have often been used to evaluate the taxonomic relatedness of B. burgdorferi sensu lato strains (11, 17, 20, 40). The results of these analyses correlated well with data from DNA-DNA hybridizations (32). The rrs gene sequence analysis of atypical strains confirmed the foregoing results and revealed at least four groups which appear to represent heretofore undescribed genospecies. CA19 belongs to B. burgdorferi sensu stricto. Three new genomic groups were CA29-CA8, CA2-CA28, and CA31-CA446, respectively. The taxonomic position of strain CA13 remains unclear. A polymorphism was observed in the rrf-rrl restriction patterns of the strains within the genomic group DN127. Also, some differences were previously reported for the physical maps of strains DN127 and CA55, which were classified in two separate groups (8). However, data originated from the single gene locus hbb (38), as well as information acquired by multilocus enzyme electrophoresis, involving the whole genome (4) were consistent with data from DNA-DNA hybridizations showing that DN127 and CA55 do belong to the same species (32). Moreover, the rrs sequences of these two strains are 100% identical. To clarify the taxonomic status of B. burgdorferi sensu lato in the United States, we propose the name B. bissettii sp. nov. for the genomic group DN127 in honor of Marjorie L. Bissett, who with her coworker Warren Hill, first described a member of this group in 1987 (5). We refrain from naming the other genomic groups until hybridization data are available for genetic characterization. Instead, we lump them here as Borrelia spp. The noncoding region between the two copies of rrf and rrl genes was shown previously to reflect the taxonomic status of strains (32). The phylogenetic study of this region showed that strains from each B. burgdorferi sensu lato species clustered as expected taxonomically, and each cluster clearly diverged from others. In contrast with the high conservation of sequences within the B. burgdorferi sensu stricto cluster, rrf-rrl sequences from Borrelia strains exhibited an unexpected broad diversity. This region is not constrained genetically, so the number of mutational events found should reflect the relative antiquity of the members of this bacterial complex. Californian strains were found scattered in different clusters. Within each cluster, the deep branches expressing the distances between the rrf-rrl sequences reflect a high divergence level. According to previous studies (23, 32), these results strongly suggest that these strains should constitute new genomic groups. Despite some discrepancies between the different trees, all are consistent with the placement of strains belonging to B. bissettii sp. nov. in a distinct cluster. Within this cluster, only strain 25015 was located on a separate branch.

In opposition with what is usually thought, more than two B. burgdorferi sensu lato species (B. burgdorferi sensu stricto and B. andersonii) seem to occur in the United States. B. burgdorferi sensu stricto is transmitted primarily by Ixodes scapularis and Ixodes pacificus ticks, whereas the new genomic groups described here are associated with these two ticks plus Ixodes neotomae (now Ixodes spinipalpis [27]) and some of its rodent hosts. Moreover, I. spinipalpis also can harbor Borrelia from other genomic groups, since strains CA2 and CA13 represent two distinct groups. Thus, there are a variety of ticks and reservoir host for B. burgdorferi sensu lato in the United States. It is not known whether B. bissettii sp. nov. and the other novel genomic groups can infect humans. All the strains used in this study were isolated from ticks or small mammals. As stated by Oliver (29), clinical manifestations of Lyme borreliosis in the southern United States are mild and some cases may be asymptomatic. Thus, the roles of B. bissettii sp. nov. and Borrelia spp. in producing Lyme borreliosis remain to be demonstrated. In addition, Picken et al. (30, 31) recently described human strains from Slovenia related to strain 25015, which belongs to B. bissettii sp. nov. on the basis of large restriction fragment pattern, protein, and plasmid profile analyses. If the strains from Slovenia are true members of B. bissettii sp. nov., the pathogenicity of this species should be evaluated there as well as in the United States. In Europe, three species are known to be pathogenic for humans; in the United States, all strains isolated from humans so far belong to B. burgdorferi sensu stricto. This could mean that I. spinipalpis does not transmit Borrelia to humans or that these new genomic groups are nonpathogenic for humans. This latter hypothesis seems more likely, since I. pacificus and I. scapularis frequently bite humans and occasionally harbor such strains. Moreover, I. spinipalpis primarily infests rodents and lagomorphs and rarely attaches to humans (25). However, despite the great number of strains isolated from I. scapularis in the United States, 25015 is the only strain recovered from this tick that belongs to a species other than B. burgdorferi sensu stricto. Also, this strain is genetically distant from other strains within B. bissettii sp. nov. This fact could reflect genetic adaptation to an unusual vector. The heterogeneity encountered among B. burgdorferi sensu lato in the United States might be compared to that described in Europe and Asia. On the latter two continents, B. garinii comprises a more heterogenous collection than B. afzelii and B. burgdorferi sensu stricto. Aside from the three pathogenic species, nonpathogenic species, such as B. valaisiana, B. lusitaniae, or B. japonica, coexist. More data are needed to understand the significance of the diversity of B. burgdorferi sensu lato and their role in human Lyme borreliosis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank T. G. Schwan and R. N. Brown for supplying some of the strains, I. Saint Girons for critical reading of the manuscript, and E. Bellenger for technical assistance.

We thank the Pasteur Institute for supporting this work. Also, many of the Californian strains were acquired during ecologic studies supported in part by funding to R.S.L. from the U.S. National Institutes of Health (grant AI22501) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (cooperative agreement U50/CCU906594).

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson J F, Barthold S W, Magnarelli L A. Infectious but nonpathogenic isolate of Borrelia burgdorferi. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:2693–2699. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.12.2693-2699.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Assous M V, Postic D, Paul G, Névot P, Baranton G. Western blot analysis of sera from Lyme borreliosis patients according to the genomic species of the Borrelia strains used as antigens. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1993;12:261–268. doi: 10.1007/BF01967256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Assous M V, Postic D, Paul G, Névot P, Baranton G. Individualisation of two genomic groups among American Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato strains. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1994;121:93–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb07081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balmelli T, Piffaretti J C. Analysis of the genetic polymorphism of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato by multilocus enzyme electrophoresis. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1996;46:167–172. doi: 10.1099/00207713-46-1-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bissett M L, Hill W. Characterization of Borrelia burgdorferi strains isolated from Ixodes pacificus ticks in California. J Clin Microbiol. 1987;25:2296–2301. doi: 10.1128/jcm.25.12.2296-2301.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown R N, Lane R S. Lyme disease in California—a novel enzootic transmission cycle of Borrelia burgdorferi. Science. 1992;256:1439–1442. doi: 10.1126/science.1604318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burgdorfer W, Barbour A G, Hayes S F, Benach J L, Grundwald E, Davis J P. Lyme disease: a tick-borne spirochetosis? Science. 1982;216:1317–1319. doi: 10.1126/science.7043737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Casjens S, Delange M, Ley III H L, Rosa P, Huang W M. Linear chromosomes of Lyme disease agent spirochetes: genetic diversity and conservation of gene order. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:2769–2780. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.10.2769-2780.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dykhuizen D E, Polin D S, Dunn J J, Wilske B, Preac-Mursic V, Dattwyler R J, Luft B J. Borrelia burgdorferi is clonal: implications for taxonomy and vaccine development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:10163–10167. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.21.10163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Foretz M, Postic D, Baranton G. Phylogenetic analysis of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto by arbitrarily primed PCR and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1997;47:11–18. doi: 10.1099/00207713-47-1-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fukunaga M, Hamase A, Okada K, Inoue H, Tsuruta Y, Miyamoto K, Nakao M. Characterization of spirochetes isolated from ticks (Ixodes tanuki, Ixodes turdus, and Ixodes columnae) and comparison of the sequences with those of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato strains. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:2338–2344. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.7.2338-2344.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fukunaga M, Okada K, Nakao M, Konishi T, Sato Y. Phylogenetic analysis of Borrelia species based on flagellin gene sequences and its application for molecular typing of Lyme disease borreliae. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1996;46:898–905. doi: 10.1099/00207713-46-4-898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fukunaga M, Yanagihara Y, Sohnaka M. The 23S/5S ribosomal RNA genes (rrl/rrf) are separate from the 16S ribosomal RNA gene (rrs) in Borrelia burgdorferi, the aetiological agent of Lyme disease. J Gen Microbiol. 1992;138:871–877. doi: 10.1099/00221287-138-5-871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jukes T H, Cantor C R. Evolution of protein molecules. In: Munro H N, editor. Mammalian protein metabolism. New York, N.Y: Academic Press; 1969. pp. 21–132. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kumar S, Tamura K, Masatoshi N. MEGA: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis, version 1.01. University Park, Pa: The Pennsylvania State University; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kurashige S, Bissett M, Oshiro L. Characterization of a tick isolate of Borrelia burgdorferi that possesses a major low-molecular-weight surface protein. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:1362–1366. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.6.1362-1366.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Le Flèche A, Postic D, Girardet K, Péter O, Baranton G. Characterization of Borrelia lusitaniae sp. nov. by 16S ribosomal DNA sequence analysis. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1997;47:921–925. doi: 10.1099/00207713-47-4-921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liveris D, Gazumyan A, Schwartz I. Molecular typing of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato by PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:589–595. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.3.589-595.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liveris D, Wormser G P, Nowakovski J, Nadelman R, Bittker S, Cooper D, Varde S, Moy F H, Forseter G, Pavia C S, Schwartz I. Molecular typing of Borrelia burgdorferi from Lyme disease patients by PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:1306–1309. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.5.1306-1309.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marconi R T, Garon C F. Phylogenetic analysis of the genus Borrelia: a comparison of North American and European isolates of Borrelia burgdorferi. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:241–244. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.1.241-244.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marconi R T, Konkel M E, Garon C F. Variability of osp genes and gene products among species of Lyme disease spirochetes. Infect Immun. 1993;61:2611–2617. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.6.2611-2617.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marconi R T, Liveris D, Schwartz I. Identification of novel insertion elements, restriction fragment length polymorphism patterns, and discontinuous 23S rRNA in Lyme disease spirochetes: phylogenetic analyses of rRNA genes and their intergenic spacers in Borrelia japonica sp. nov. and genomic group 21038 (Borrelia andersonii sp. nov.) isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2427–2434. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.9.2427-2434.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Masuzawa T, Komikado T, Iwaki A, Suzuki H, Kaneda K, Yanagihara Y. Characterization of Borrelia sp. isolated from Ixodes tanuki, I. turdus, and I. columnae in Japan by restriction fragment length polymorphism of rrf (5S)-rrl (23S) intergenic spacer amplicons. FEMS Microbiol. 1996;142:77–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1996.tb08411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mathiesen D A, Oliver J H, Jr, Kolbert C P, Tullson E D, Johnson B J B, Campbell G L, Mitchell P D, Reed K D, Telford III S R, Anderson J F, Lane R S, Persing D H. Genetic heterogeneity of Borrelia burgdorferi in the United States. J Infect Dis. 1997;175:98–107. doi: 10.1093/infdis/175.1.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maupin G O, Gage K L, Piesman J, Montenieri J, Sviat S L, VanderZanden L, Happ C M, Dolan M, Johnson B J B. Discovery of an enzootic cycle of Borrelia burgdorferi in Neotoma mexicana and Ixodes spinipalpis from northern Colorado, an area where Lyme disease is nonendemic. J Infect Dis. 1994;170:636–643. doi: 10.1093/infdis/170.3.636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Norris D E, Johnson B J B, Piesman J, Maupin G O, Clark J L, Black W C. Culturing selects for specific genotypes of Borrelia burgdorferi in an enzootic cycle in Colorado. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2359–2364. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.9.2359-2364.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Norris D E, Klompen J S H, Keirans J E, Lane R S, Piesman J, Black W C., IV Taxonomic status of Ixodes neotomae and I. spinipalpis (Acari: Ixodidae) based on mitochondrial DNA evidence. J Med Entomol. 1997;34:696–703. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/34.6.696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ojaimi C, Davidson B E, Saint Girons I, Old I G. Conservation of gene arrangement and an unusual organization of rRNA genes in the linear chromosomes of the Lyme disease spirochaetes Borrelia burgdorferi, B. garinii and B. afzelii. Microbiology. 1994;140:2931–2940. doi: 10.1099/13500872-140-11-2931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oliver J H. Lyme borreliosis in the southern United States: a review. J Parasitol. 1996;82:926–935. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Picken R N, Cheng Y, Strle F, Cimperman J, Maraspin V, Lotricfurlan S, Ruzicsabljic E, Han D, Nelson J A, Picken M M, Trenholme G M. Molecular characterization of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato from Slovenia revealing significant differences between tick and human isolates. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1996;15:313–323. doi: 10.1007/BF01695664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Picken R N, Cheng Y, Strle F, Picken M M. Patient isolates of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato with genotypic and phenotypic similarities to strain 25015. J Infect Dis. 1996;174:1112–1115. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.5.1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Postic D, Assous M V, Grimont P A D, Baranton G. Diversity of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato evidenced by restriction fragment length polymorphism of rrf (5S)-rrl (23S) intergenic spacer amplicons. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1994;44:743–752. doi: 10.1099/00207713-44-4-743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ruimy R, Breittmayer V, Elbaze P, Lafay B, Boussemart O, Gauthier M, Christen R. Phylogenetic analysis and assessment of the genera Vibrio, Photobacterium, Aeromonas, and Plesiomonas deduced from small-subunit rRNA sequences. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1994;44:416–426. doi: 10.1099/00207713-44-3-416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol. 1987;4:406–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schwan T G, Schrumpf M E, Karstens R H, Clover J R, Wong J, Daugherty M, Struthers M, Rosa P A. Distribution and molecular analysis of Lyme disease spirochetes, Borrelia burgdorferi, isolated from ticks throughout California. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:3096–3108. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.12.3096-3108.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schwartz J J, Gazumyan A, Schwartz I. rRNA gene organization in the Lyme disease spirochete, Borrelia burgdorferi. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:3757–3765. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.11.3757-3765.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sneath P H A, Sokal R R. Numerical taxonomy. San Francisco, Calif: Freeman; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Valsangiacomo C, Balmelli T, Piffaretti J C. A phylogenetic analysis of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato based on sequence information from the hbb gene, coding for a histone-like protein. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1997;47:1–10. doi: 10.1099/00207713-47-1-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Van Dam A P, Kuiper H, Vos K, Widjojokusumo A, de Jongh B M, Spanjaard L, Ramselaar A C P, Kramer M D, Dankert J. Different genospecies of Borrelia burgdorferi are associated with distinct clinical manifestations of Lyme borreliosis. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;17:708–717. doi: 10.1093/clinids/17.4.708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang G, van Dam A P, Le Flèche A, Postic D, Péter O, Baranton G, de Boer R, Spanjaard L, Dankert J. Genetic and phenotypic analysis of Borrelia valaisiana sp. nov. (Borrelia genomic groups VS116 and M19) Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1997;47:926–932. doi: 10.1099/00207713-47-4-926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zingg B C, Anderson J F, Johnson R C, LeFebvre R B. Comparative analysis of genetic variability among Borrelia burgdorferi isolates from Europe and the United States by restriction enzyme analysis, gene restriction fragment length polymorphism, and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:3115–3122. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.12.3115-3122.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zingg B C, Brown R N, Lane R S, LeFebvre R B. Genetic diversity among Borrelia burgdorferi isolates from wood rats and kangaroo rats in California. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:3109–3114. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.12.3109-3114.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]