Key Points

Question

Are US health care workers at greater risk of suicide than non–health care workers?

Findings

From a nationally representative cohort of approximately 1.84 million employed adults observed from 2008 through 2019 and controlling for potentially confounding sociodemographic characteristics, the risk of suicide was higher for health care workers compared with non–health care workers including specifically registered nurses, health care support workers, and health technicians.

Meaning

Heightened suicide risk for registered nurses, health care support workers, and health technicians highlights the need for concerted efforts to support their mental health.

Abstract

Importance

Historically elevated risks of suicide among physicians may have declined in recent decades. Yet there remains a paucity of information concerning suicide risks among other health care workers.

Objective

To estimate risks of death by suicide among US health care workers.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Cohort study of a nationally representative sample of workers from the 2008 American Community Survey (N = 1 842 000) linked to National Death Index records through December 31, 2019.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Age- and sex-standardized suicide rates were estimated for 6 health care worker groups (physicians, registered nurses, other health care–diagnosing or treating practitioners, health technicians, health care support workers, social/behavioral health workers) and non–health care workers. Cox models estimated hazard ratios (HRs) of suicide for health care workers compared with non–health care workers using adjusted HRs for age, sex, race and ethnicity, marital status, education, and urban or rural residence.

Results

Annual standardized suicide rates per 100 000 persons (median age, 44 [IQR, 35-53] years; 32.4% female [among physicians] to 91.1% [among registered nurses]) were 21.4 (95% CI, 15.4-27.4) for health care support workers, 16.0 (95% CI, 9.4-22.6) for registered nurses, 15.6 (95% CI, 10.9-20.4) for health technicians, 13.1 (95% CI, 7.9-18.2) for physicians, 10.1 (95% CI, 6.0-14.3) for social/behavioral health workers, 7.6 (95% CI, 3.7-11.5) for other health care–diagnosing or treating practitioners, and 12.6 (95% CI, 12.1-13.1) for non–health care workers. The adjusted hazards of suicide were increased for health care workers overall (adjusted HR, 1.32 [95% CI, 1.13-1.54]), health care support workers (adjusted HR, 1.81 [95% CI, 1.35-2.42]), registered nurses (adjusted HR, 1.64 [95% CI, 1.21-2.23]), and health technicians (adjusted HR, 1.39 [95% CI, 1.02-1.89]), but adjusted hazards of suicide were not increased for physicians (adjusted HR, 1.11 [95% CI, 0.71-1.72]), social/behavioral health workers (adjusted HR, 1.14 [95% CI, 0.75-1.72]), or other health care–diagnosing or treating practitioners (adjusted HR, 0.61 [95% CI, 0.36-1.03) compared with non–health care workers (reference).

Conclusions

Relative to non–health care workers, registered nurses, health technicians, and health care support workers in the US were at increased risk of suicide. New programmatic efforts are needed to protect the mental health of these US health care workers.

This cohort study compares rates of suicide among 6 categores of US health care workers vs non–health care workers.

Introduction

Compared with the general population, physicians tend to live longer1 and have healthier2 lives. In their occupational roles, however, physicians and other health care workers routinely engage in stressful tasks of caring for severely ill individuals and managing heavy workloads, with little control over patient outcomes. Because health care occupations vary in their emotional demands, they may also vary in suicide risk.

An early meta-analysis (1963-2002), which included some small and methodologically crude studies, reported increased suicide standardized mortality ratios (SMRs) for female (2.27 [95% CI, 1.90-2.73]) and male (1.41 [95% CI, 1.21-1.65]) physicians compared with females and males in the general population.3 A more recent meta-analysis (1969-2018) concluded that corresponding suicide SMRs were 1.94 (95% CI, 1.49-2.58) for female physicians and 1.24 (95% CI, 1.05-1.43) for male physicians.4

Much less is known about suicide risks of the approximately 95% of health care workers who are not physicians. We present results from a nationally representative cohort of 2008 American Community Survey (ACS) participants, who were followed up for cause of death through 2019. We compare suicide risks of physicians, registered nurses, other health care–diagnosing or treating practitioners, health technicians, health care support workers, and social/behavioral health workers with non–health care workers.

Methods

Study population

The study cohort was identified within the Mortality Disparities in American Communities (MDAC) data set5 that links 2008 ACS participants (2.9 million addresses; 97.9% response rate)6 to National Death Index records. We selected employed ACS participants who were aged 26 years or older (N = 1 842 000).

Study Variables

Health care workers were considered among the 6 following groups: (1) registered nurses; (2) health care support workers including nursing, psychiatric, and home health aides, and other support workers; (3) health technologists and technicians (hereafter health technicians); (4) social/behavioral health workers including social workers, counselors, psychologists, and others; (5) other health care–diagnosing or treating practitioners including dentists, physician assistants, and others; and (6) physicians (Box).7

Box. Health Care Worker Groups and Constituent Occupations.

Registered Nurses (n = 42 000)

Health Care Support Workers (n = 39 000)

Nursing, psychiatric, and home health aides; occupational therapist assistants and aides; physical therapist assistants and aides; massage therapists; dental assistants; medical assistants and other health care support occupations

Health Technicians (n = 32 500)

Clinical laboratory technologists and technicians; dental hygienists; diagnostic-related technologists and technicians; emergency medical technicians and paramedics; health care–diagnosing or treating practitioner support technicians; licensed practical and licensed vocational nurses; medical records and health information technicians; dispensing opticians; miscellaneous health technologists and technicians; and other health care practitioners and technical occupations

Social/Behavioral Health Workers (n = 27 000)

Psychologists, counselors, social workers, and other community and social service specialists

Other Health Care–Diagnosing or Treating Practitioners (n = 22 500)

Chiropractors, dentists, dietitians and nutritionists, optometrists, pharmacists, physician assistants, podiatrists, audiologists, occupational therapists, physical therapists, radiation therapists, recreational therapists, respiratory therapists, speech-language pathologists, other therapists, and other health care–diagnosing or treating practitioners

Physicians (n = 13 000)

Physicians and surgeons

Participant sociodemographic characteristics included age in years, sex, race and ethnicity, marital status, education, personal annual income, and residence (urban vs rural). The study outcome was suicide (International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification codes: X60-X84, Y87.0, U03) as the underlying cause of death.

Statistical Analysis

Baseline sociodemographics of worker groups were characterized. Age- and sex-standardized suicide rates per 100 000 person-years with 95% CIs were calculated using the direct method with the entire employed cohort (≥ 26 years) as the reference group. Cox proportional hazard regressions estimated suicide hazard ratios (HRs) for health care worker groups (compared with non–health care workers as the reference group) adjusted for age, sex, race and ethnicity, marital status, education, and urban or rural residence. Event time was measured from ACS survey to suicide, death from other causes, or December 31, 2019, whichever came first. Because occupation generally determines personal income, income was added to secondary analyses as a potential mediator. The interaction of sex by worker group (total health care vs non–health care) with suicide hazard was explored. Because no adjustments were made for multiple comparisons (α = .05), CIs should be interpreted with caution.

ACS weights accounted for age, sex, race, Hispanic ethnicity, and state of residence. Final MDAC-adjusted weights were ratio-adjusted for Hispanic ethnicity and reweighted by raking intersections of age, sex, and race by state. The Census Disclosure Review Board approved data releases. Analyses were performed using SAS statistical software (version 9.4).

Results

Background Characteristics

Occupational groups varied in sociodemographic composition (Table). Registered nurses and health care support workers included the highest percentages of women; physicians included the highest percentage of men. Among health care workers, health care support workers included the highest percentages of non–Hispanic Black and Hispanic individuals. Incomes of physicians, registered nurses, and other health care–diagnosing or treating practitioners were highest while those of health care support workers were lowest.

Table. Sociodemographic Characteristics of Health Care Occupational Groups and Non–Health Care Workersa.

| Characteristic | Registered nurses | Health care support workers | Health technicians | Social/behavioral health workers | Other health care–diagnosing or treating practitioners | Physicians | Non–health care workers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample, No.b | 42 000 | 39 000 | 32 500 | 27 000 | 22 500 | 13 000 | 1 666 000 |

| Age group, y | |||||||

| 26-35 | 32.4 | 25.8 | 26.7 | 25.0 | 25.8 | 26.2 | 25.2 |

| 36-45 | 19.5 | 16.3 | 15.7 | 21.2 | 18.5 | 24.6 | 28.0 |

| 46-55 | 21.4 | 30.0 | 29.6 | 28.7 | 27.4 | 21.5 | 27.4 |

| >55 | 26.7 | 27.9 | 28.0 | 25.1 | 28.2 | 27.7 | 19.4 |

| Age, median (IQR), y | 46 (37-54) | 43 (34-52) | 43 (34-52) | 44 (34-54) | 43 (35-53) | 46 (37-55) | 44 (35-53) |

| Sex | |||||||

| Female | 91.1 | 89.6 | 78.3 | 72.5 | 60.9 | 32.4 | 43.4 |

| Male | 8.9 | 10.4 | 21.7 | 27.5 | 39.1 | 67.6 | 56.6 |

| Race and ethnicity | |||||||

| Black, non-Hispanic | 10.1 | 26.7 | 15.5 | 19.5 | 6.3 | 5.3 | 10.1 |

| Hispanic | 4.3 | 13.3 | 7.7 | 10.4 | 5.0 | 5.7 | 14.0 |

| Other | 9.4 | 6.5 | 6.9 | 4.7 | 9.5 | 18.8 | 6.4 |

| White, non-Hispanic | 76.2 | 53.4 | 69.9 | 65.4 | 79.2 | 70.2 | 69.4 |

| Marital status | |||||||

| Married | 66.8 | 50.5 | 60.1 | 56.3 | 71.4 | 77.7 | 63.2 |

| Separated or divorced | 18.0 | 23.1 | 19.3 | 17.9 | 11.6 | 7.8 | 15.8 |

| Widowed | 2.6 | 4.1 | 2.5 | 2.3 | 1.3 | 1.0 | 2.2 |

| Never married | 12.5 | 22.3 | 18.1 | 23.6 | 15.8 | 13.4 | 18.8 |

| Education attainedc | |||||||

| <High school | 0.4 | 11.4 | 1.6 | 1.4 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 10.4 |

| High school or GED | 1.7 | 33.6 | 17.0 | 7.0 | 2.7 | 0.8 | 27.1 |

| Some college or associate’s degree | 43.1 | 44.7 | 59.6 | 18.0 | 11.1 | 2.1 | 30.9 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 42.0 | 7.5 | 17.4 | 31.4 | 25.8 | 1.8 | 20.4 |

| ≥Master’s degree | 10.3 | 1.5 | 2.8 | 34.5 | 22.8 | 2.4 | 8.2 |

| Doctoral degreed | 2.6 | 1.2 | 1.6 | 7.8 | 36.9 | 92.6 | 2.9 |

| Income level | |||||||

| 0-$40 000\(Loss)e | 5.3 | 37.7 | 16.8 | 16.8 | 6.2 | 3.5 | 21.1 |

| $40 001-$75 000 | 24.8 | 34.0 | 34.5 | 31.2 | 18.2 | 10.0 | 30.9 |

| $75 001-$125 000 | 39.7 | 20.7 | 33.0 | 32.6 | 33.0 | 13.8 | 28.7 |

| >$125 000 | 30.2 | 7.5 | 15.7 | 19.4 | 42.6 | 72.8 | 19.3 |

| Residence | |||||||

| Urban | 74.2 | 77.6 | 74.1 | 81.1 | 76.9 | 83.4 | 76.6 |

| Rural | 25.8 | 22.4 | 25.9 | 18.9 | 23.1 | 16.6 | 23.4 |

Abbreviation: GED, general educational development test.

Data are reported as percent values (based on weighted data) unless otherwise indicated. Data are from the Mortality Disparities in American Communities data set,5 limited to adults aged 26 years and older who were employed at time of the American Community Survey administration. US Census Bureau disclosure review board approval number: CBDRB-FY23-CES004-020.

Numbers of workers are based on unweighted numeric values and rounded to the nearest 500 following US Census rules.

The tabulated data correctly represent the responses to the education question by individuals who reported that they worked as physicians. However, in large general population surveys, there is no means of verifying the accuracy of individual survey responses (eg, physicians with <high school).

Additionally includes professional degrees beyond a bachelor’s degree.

Loss refers to negative or a loss in income dollars for the past 12 months.

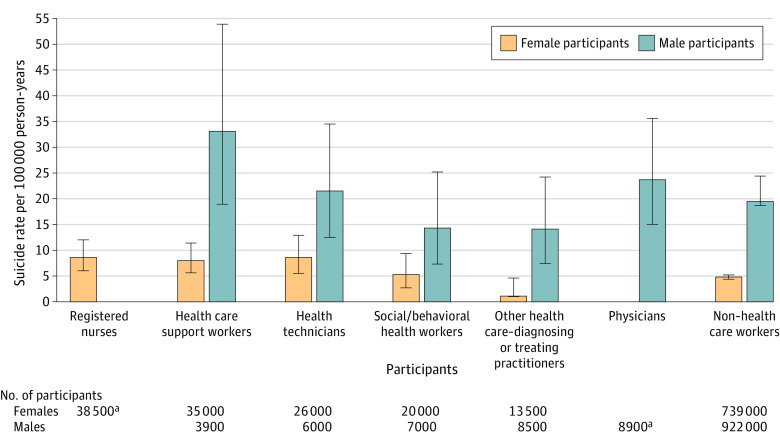

Suicide Risk

Compared with non–health care workers, sex- and age-standardized suicide rates were significantly higher for health care workers overall, including for registered nurses, health care support workers, and health technicians (Figure 1). Other health care–diagnosing or treating practitioners had lower standardized suicide rates than non–health care workers.

Figure 1. Suicide Risks of Health Care Workers Compared With Non–Health Care Workersa.

aData are from the Mortality Disparities in American Communities data set,5 which is limited to adults aged 26 years and older who were employed at the time of the American Community Survey administration. Respondent follow-up duration was through 2019. US Census Bureau disclosure review board approval number: CBDRB-FY23-CES004-029.

bValues for the number of participants, suicide deaths, and years observed are based on unweighted numbers and rounded following US Census Bureau rules.

cP values indicate comparisons with non–health care workers.

dModel 1 is adjusted for age, sex, race and ethnicity, marital status, education, and residence.

eModel 2 is adjusted for age, sex, race and ethnicity, marital status, education, residence, and income.

fInteraction of sex by worker status (health care vs non–health care), χ2 = 4.83; P = .03.

gInteraction of sex by worker status (health care vs non–health care), χ2 = 4.98; P = .03.

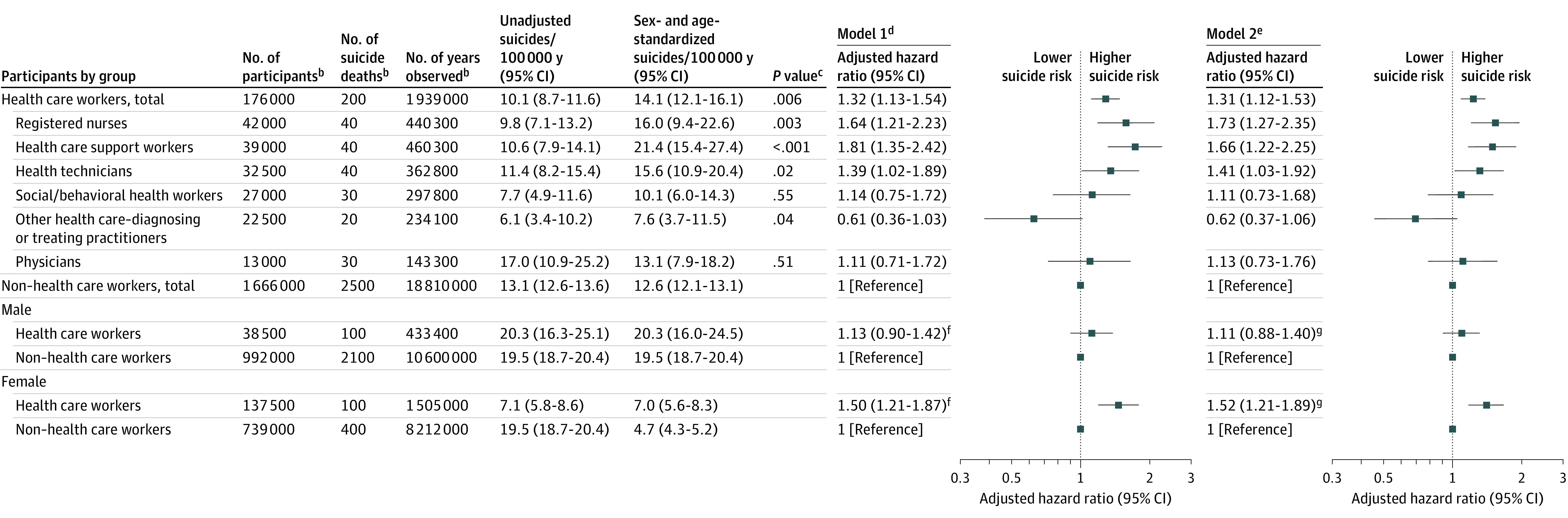

After controlling for potentially confounding sociodemographic characteristics, the adjusted suicide hazards were significantly higher for registered nurses, health care support workers, and health technicians than for non–health care workers (Figure 1). Results did not change appreciably by additionally controlling for income or truncating follow-up at age 65 (eTable 1 in Supplement 1). In an exploratory adjusted Cox regression, the association between occupation (health care vs non–health care worker) and suicide risk was significantly greater for females than males (χ2 = 4.83; P = .03). Sex-stratified suicide rates by occupational group appear in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Suicide Rates per 100 000 Person-Years of Female and Male Health Care Workers and Non–Health Care Workers.

Data are from the Mortality Disparities in American Communities data set,5 which is limited to adults aged 26 years and older who were employed at time of the American Community Survey administration. Numbers of participants are unweighted and rounded to the nearest 500 according to US Census rules. US Census Bureau disclosure review board approval number: CBDRD-FY23-CES004-029.

aThe suicide rates of male registered nurses and female physicians are suppressed to protect participant reidentification. Error bars indicate 95% CIs.

Discussion

Health care workers overall, including registered nurses, health technicians, and health care support workers, were at increased risk of suicide compared with non–health care workers. These results are broadly consistent with evidence that health care workers compared with other workers have elevated risks for mental health problems including higher rates of mood disorders8 and long-term work absences due to mental disorders.9 The importance of increased suicide risk of health care support workers is underscored by their growth from 3.8 million (in 2008) to 6.6 million (in 2021), coinciding with aging of the US population.7

Little is known about specific health care work-related occupational exposures that contribute to suicide risk. For example, burnout has been associated with suicidal ideation in some,10 but not all,11 studies. In the Nurses’ Health Study, work and home stress were related to increased suicide risk,12 while social integration was related to reduced risk.13

Physicians were not at increased suicide risk compared to non–health care workers, though confidence intervals were wide, and sample size constrained stratifying by sex. However, because health care work overall was more strongly associated with suicide risk among female than male workers, future research might examine potential gender-related explanatory mechanisms such as gender differences in work roles, job satisfaction, and occupational stress.

Limitations

This analysis has several limitations. First, the mortality data, which terminated in 2019, do not reflect suicide risks during the COVID-19 era.

Second, death data based on International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification codes may not accurately classify suicide deaths. Suicide deaths involving health care professionals may be particularly prone to underreporting.

Third, there is no means of verifying the accuracy of individual survey responses. In addition, occupational status was based on a 1-time assessment and participants could have changed occupations or retired during follow-up.

Fourth, because ACS does not measure key suicide risk factors, including suicide attempts or mental disorders preceding occupational entry, selection of vulnerable individuals into health care work cannot be distinguished from occupational-related risks.

Fifth, the standard error estimates in this study do not account for within-household clustering of study participants, which is related to household size and intraclass correlation with the outcome. This design effect is reduced by restriction to employed adults and a rare outcome.14

Sixth, sample size limitations constrained precision of risk estimates, increased occupational group heterogeneity, and prevented comparisons between health care worker groups.

Conclusion

During the COVID-19 pandemic peak, the mental health of health care workers received considerable national attention. As the pandemic has receded, efforts to improve the mental health of health care workers could lose momentum. The present analysis, which involves the period before the pandemic, underscores mental health risks for health care workers. To address this challenge, it will be important to identify and ameliorate specific work-related factors that contribute to mental health occupational risks of health care workers, especially registered nurses, health technicians, and health care support workers. In the meantime, developing a coordinated range of workplace mental health interventions may be warranted. The National Plan for Health Workforce Well-Being has emphasized that coordinated systematic efforts to increase access to and lower stigma of confidential and affordable mental health services are needed. Such efforts should ensure that health care workers do not experience punitive consequences for seeking mental health treatment.15

Educational Objective: To identify the key insights or developments described in this article.

-

Age- and sex-standardized suicide rates, adjusted for confounding sociodemographic characteristics, were highest in which group?

Physicians

Registered nurses

Social and behavioral health workers

-

The authors note prior literature that found higher rates of suicide-standardized mortality among physicians, and especially female physicians, in comparison with the general population. What did this study find with regard to physicians?

Male physicians, but not female physicians, demonstrated higher suicide rates compared with non–health care workers.

Physicians were generally younger than the rest of the population under study, confounding comparative data and making conclusions unreliable.

Suicide risk was not increased for physicians compared with non–health care workers although CIs were wide.

-

Among the limitations authors note is this:

Data collection concluded before the COVID-19 era, with its attendant stressors for health care professionals.

Health care workers without a clear cause of death may be more likely to have suicide reported as the cause of death.

The non–health care worker comparison group may have been too heterogenous to be a meaningful reference standard for more strictly defined cohorts of health care workers.

eTable 1. Suicide Risks of Health Care Workers Compared With Non–Health Care Workers Limited to Age 65 Years and Younger

eTable 2. Suicide Rates Per 100 000 Person-Years of Female and Male Health Care Workers and Non–Health Care Workers

Data Sharing Statement

Footnotes

Data are from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics.7 Numeric values are based on unweighted survey numbers and rounded to the nearest 500 following US Census rules.

References

- 1.Frank E, Biola H, Burnett CA. Mortality rates and causes among US physicians. Am J Prev Med. 2000;19(3):155-159. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(00)00201-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ko DT, Chu A, Austin PC, et al. Comparison of cardiovascular risk factors and outcomes among practicing physicians vs the general population in Ontario, Canada. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(11):e1915983. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.15983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schernhammer ES, Colditz GA. Suicide rates among physicians: a quantitative and gender assessment (meta-analysis). Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(12):2295-2302. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.12.2295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dutheil F, Aubert C, Pereira B, et al. Suicide among physicians and health-care workers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2019;14(12):e0226361. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0226361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.US Census Bureau . Mortality Disparities in American Communities (MDAC): Analysis File, Reference Manual, Version 1.0. Accessed July 7, 2023. https://www.census.gov/topics/research/mdac.Reference_Manual.html#list-tab-1414305400

- 6.United States Census Bureau . American Community Survey (ACS). Accessed June 26, 2023. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs

- 7.United States Bureau of Labor Statistics . 2000 Standard Occupational Classification (SOC) Users Guide. Accessed June 25, 2023. https://www.bls.gov/soc/2000/home.htm

- 8.Wieclaw J, Agerbo E, Mortensen PB, Bonde JP. Risk of affective and stress related disorders among employees in human service professions. Occup Environ Med. 2006;63(5):314-319. doi: 10.1136/oem.2004.019398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kokkinen L, Kouvonen A, Buscariolli A, Koskinen A, Varje P, Väänänen A. Human service work and long-term sickness absence due to mental disorders: a prospective study of gender-specific patterns in 1 466 100 employees. Ann Epidemiol. 2019;31:57-61.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2018.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Massie FS, et al. Burnout and suicidal ideation among US medical students. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149(5):334-341. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-5-200809020-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Menon NK, Shanafelt TD, Sinsky CA, et al. Association of physician burnout with suicidal ideation and medical errrors. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(12):e2028780. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.28780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feskanich D, Hastrup JL, Marshall JR, et al. Stress and suicide in the Nurses’ Health Study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2002;56(2):95-98. doi: 10.1136/jech.56.2.95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tsai AC, Lucas M, Kawachi I. Association between social integration and suicide among women in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(10):987-993. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.1002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gulliford MC, Adams G, Ukoumunne OC, Latinovic R, Chinn S, Campbell MJ. Intraclass correlation coefficient and outcome prevalence are associated in clustered binary data. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58(3):246-251. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Academy of Medicine;Action Collaborative on Clinician Well-Being and Resilience; Dzau VJ, Kirch D, Murthy V, Nasca T, eds. National Plan for Health Workforce Well-Being. National Academies Press; 2022, doi: 10.17226/26744. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Suicide Risks of Health Care Workers Compared With Non–Health Care Workers Limited to Age 65 Years and Younger

eTable 2. Suicide Rates Per 100 000 Person-Years of Female and Male Health Care Workers and Non–Health Care Workers

Data Sharing Statement