Abstract

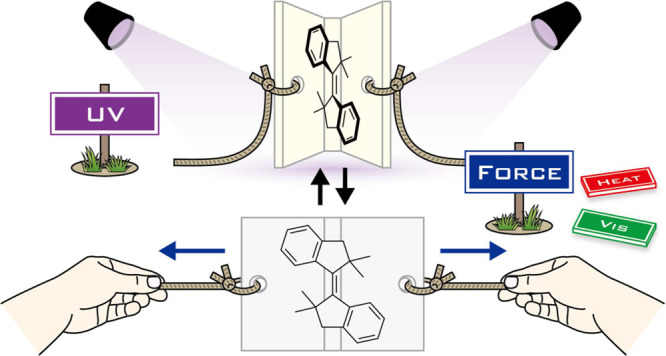

Molecular photoswitches are extensively used as molecular machines because of the small structures, simple motions, and advantages of light including high spatiotemporal resolution. Applications of photoswitches depend on the mechanical responses, in other words, whether they can generate motions against mechanical forces as actuators or can be activated and controlled by mechanical forces as mechanophores. Sterically hindered stiff stilbene (HSS) is a promising photoswitch offering large hinge-like motions in the E/Z isomerization, high thermal stability of the Z isomer, which is relatively unstable compared to the E isomer, with a half-life of ca. 1000 years at room temperature, and near-quantitative two-way photoisomerization. However, its mechanical response is entirely unexplored. Here, we elucidate the mechanochemical reactivity of HSS by incorporating one Z or E isomer into the center of polymer chains, ultrasonicating the polymer solutions, and stretching the polymer films to apply elongational forces to the embedded HSS. The present study demonstrated that HSS mechanically isomerizes only in the Z to E direction and reversibly isomerizes in combination with UV light, i.e., works as a photomechanical hinge. The photomechanically inducible but thermally irreversible hinge-like motions render HSS unique and promise unconventional applications differently from existing photoswitches, mechanophores, and hinges.

Keywords: photoswitch, molecular machine, molecular hinge, mechanophore, polymer mechanochemistry

Introduction

Synthetic molecular machines convert inputs of external stimuli into outputs of controlled mechanical work and attract considerable attention from various fields as the smallest machines.1 Switches2,3 and motors4,5 are the two main categories. Switches are able to reversibly interconvert between at least two thermodynamically (meta)stable states, and motors are capable of cycling unidirectional rotation. In the past few decades, a variety of molecular switches and motors have been designed and developed, and the actuation at the molecular level has been demonstrated. Recently, synthetic molecular machines have been incorporated into organic and inorganic materials including metals, crystals, liquid crystals, metal–organic frameworks, glasses, elastomers, and gels to use their actuation in a practical manner.4−10

In molecular switches, photoisomerizable switches are primarily employed because of the small structures, simple motions, and advantages of light, such as high spatiotemporal resolution, easy and precise control of wavelength and intensity, and no chemical waste. Particularly, azobenzene (AB) is the most commonly used photoswitch in all fields and characterized by the large motions generated in the isomerization between the thermodynamically stable E and unstable Z isomers (Figure 1).11−13 However, the Z isomer is so thermally unstable that the thermal Z-to-E isomerization proceeds rapidly even at room temperature with a half-life (t1/2) of ca. 1 day,11−13 which precludes precise control and limits applications, except for ortho-substituted ABs and azoheteroarenes (t1/2 < several years at room temperature).14−18 Similarly, spiropyran (SP)19,20 and diarylethene (DAE)21,22 are representative photoswitches following AB (Figure 1). SP features the large polarity changes in the isomerization with merocyanine (MC) but shows small motions and prompt thermal isomerization from MC to SP at room temperature.23,24 Although the conjugation changes of DAE are fascinating, the thermally irreversible isomerization also involves only small motions. Therefore, the top three photoswitches cannot combine both large motions and high thermal stability, which are definitely required for practical uses as mechanical photoswitches. In this context, we recently found that sterically hindered stiff stilbene (HSS) is a promising mechanical photoswitch offering unique hinge-like motions larger than AB and parent stiff stilbene (SS)25 in the E/Z isomerization, high thermal stability of the relatively unstable Z isomer with a t1/2 of ca. 1000 years at room temperature, and 90% two-way photoisomerization (Figure 1).26 These properties are superior to those of AB and comparable to those of emerging and sophisticated hydrazone-based photoswitches.27−30 Therefore, HSS is expected to be leveraged in materials as with the typical photoswitches and hydrazones.31−38 However, the response to mechanical forces, i.e., whether HSS mechanically isomerizes, should be elucidated before the use because HSS will work as a machine in materials. In fact, the mechanical responses of the typical photoswitches have been investigated (Figure 1), and their applications have been considered and selected based on the responses.39,40 Mechanical forces isomerize Z-AB to E-AB,41 and tension accelerates the thermal Z-to-E isomerization.42 Thus, AB cannot directly cause macroscopic actuation, which is achieved mainly with the help of the liquid crystallinity.43 SP is well-known to undergo mechanoisomerization to MC44 and applied to mechanochromic polymers as a force probe (mechanophore).45,46 The mechanical ring-opening of DAE would strongly depend on the chemical structures and remains under discussion.47,48 Other photoisomerizable switches such as naphthopyran,49−53 oxazine,54,55 and rhodamine56−60 have been also reported to mechanically isomerize and employed as mechanophores in polymeric materials similar to SP. The mechanical response of HSS would be affected by the significantly high energy barrier in the ground-state isomerization26 but is completely unknown (Figure 1), although large strains in SS macrocycles were found to cause thermal E-to-Z isomerization61 in the context of molecular force probes.61−65

Figure 1.

Isomerization by external stimuli, amplitude of motions, and thermal stability of typical photoswitches and HSS.

In this study, we elucidated the mechanochemical reactivity of HSS by incorporating one HSS into the center of polymer chains, irradiating the polymer solutions with ultrasound, and stretching the films to apply mechanical forces to the embedded HSS. The mechanical response in addition to the large hinge-like motions, high thermal stability, and near-quantitative two-way photoisomerization render HSS a unique photoswitch, mechanophore, and hinge.

Results and Discussion

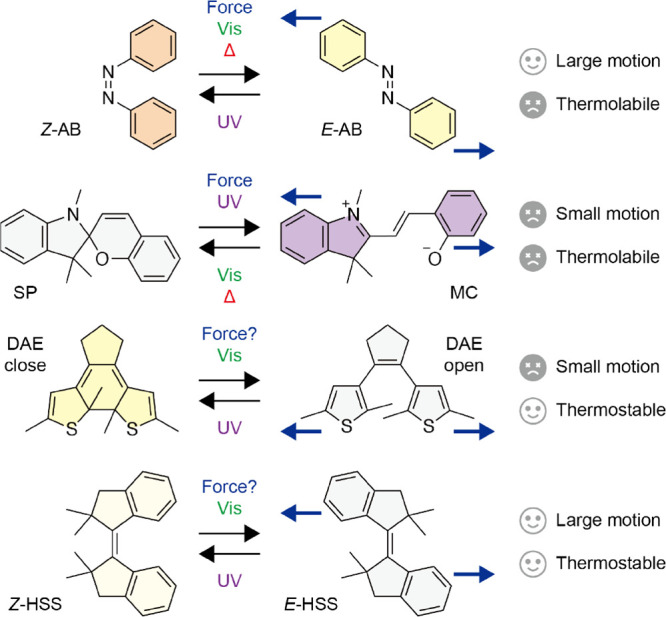

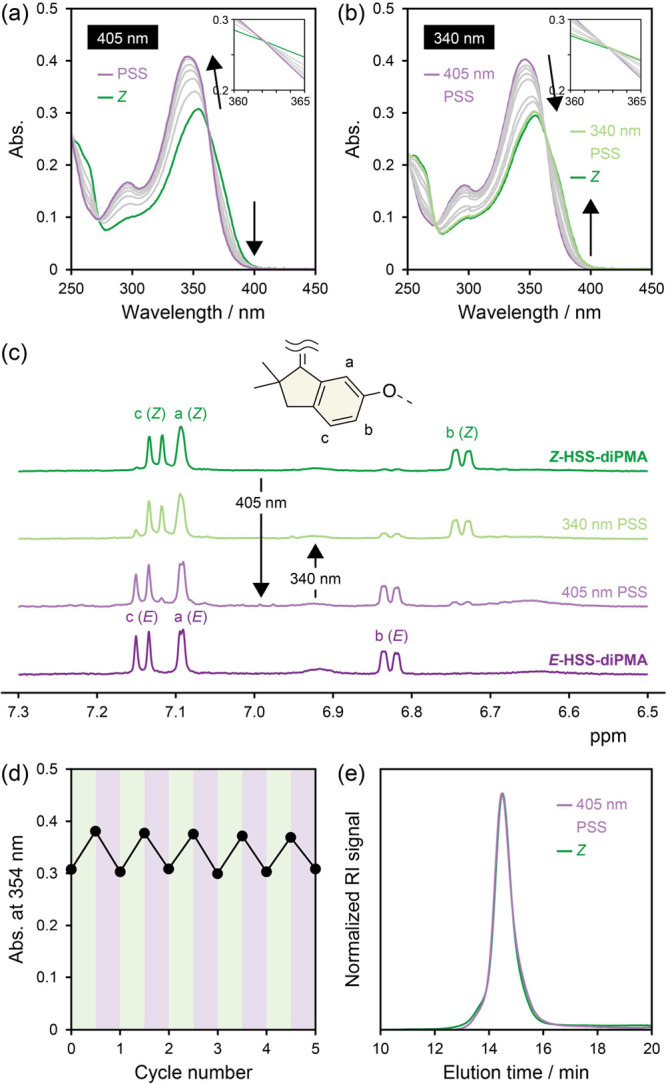

First, we examined the mechanical response simply by grinding powder of the Z and E isomers of a low-molecular-weight HSS with two methoxy groups at the C6 and C6′ positions, HSS-dimethoxy (Figure S1).66 However, any changes were not observed in the UV/vis absorption spectra of Z-HSS-dimethoxy and E-HSS-dimethoxy after grinding (Figure S2). Then, we designed and synthesized Z-HSS and E-HSS with two initiators for atom transfer radical polymerization (ATRP) at the C6 and C6′ positions to incorporate HSS into polymers and apply mechanical forces to HSS through polymer chains (Schemes S1 and S2 and see the Supporting Information for details). The ATRP of methyl acrylate (MA) using the initiators produced poly(methyl acrylate)s (PMAs) with one Z-HSS or E-HSS at the center of polymer chains, Z-HSS-diPMA and E-HSS-diPMA (Figure 2). The unimodal size exclusion chromatography (SEC) curves (refractive index (RI) signals) with high number average molecular weights (Mn = 139,800 and 209,900) and narrow polydispersity indices (PDIs = 1.13 and 1.29) indicate the successful polymerization (Figures 3e, S12, and S18). In the following, we mainly focus on Z-HSS-diPMA because mechanical forces would induce the Z-to-E isomerization as with AB.41,42

Figure 2.

Chemical structures of Z-HSS-diPMA and E-HSS-diPMA.

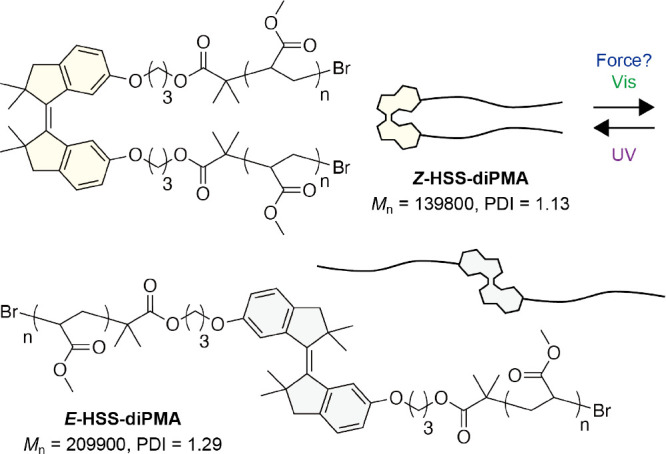

Figure 3.

UV/vis absorption spectra of Z-HSS-diPMA upon irradiation with (a) 405 nm and (b) 340 nm light in THF (2.00 mg mL–1). (c) 1H NMR spectra of Z-HSS-diPMA, 405 and 340 nm PSSs, and E-HSS-diPMA (500 MHz, acetone-d6). (d) Changes in absorbance at 354 nm upon alternating irradiation of Z-HSS-diPMA with 405 and 340 nm light in THF (2.00 mg mL–1). (e) Normalized SEC curves of Z-HSS-diPMA and 405 nm PSS.

We verified the photoswitching ability of the incorporated HSS by UV/vis absorption spectroscopy. Z-HSS-diPMA was dissolved in tetrahydrofuran (THF, 2.00 mg mL–1) and irradiated with 405 nm visible light. The spectra gradually changed and approached to that of the E isomer26 (Figure S30) with two isosbestic points at 272 and 362 nm (Figure 3a), indicating the Z-to-E isomerization without any side reactions. Conversely, irradiation with 340 nm UV light to the solution at the photostationary state (PSS) caused isomerization to the Z isomer with the two isosbestic points (Figure 3b). At the PSSs by 405 and 340 nm irradiation, the Z/E ratios were roughly determined to be 18/82 and 79/21, respectively, from the 1H NMR spectra (Figure 3c), which are comparable to those of the low-molecular-weight HSS, HSS-dimethoxy.26 The reversible photoisomerization was repeatedly observed in at least five cycles (Figures 3d and S31). Therefore, the embedded HSS possesses the capability of photoswitching even after the radical polymerization. This is one of the advantages over parent SS because an SS-based initiator degraded in a similar ATRP condition (Scheme S3 and see the Supporting Information for details) and obtained polymers had little photoabsorption originating from SS (Figure S32). The radical species and Cu complex caused side reactions in the ATRP (Figure S33), which were prevented by the steric hindrance around the central C=C bond in HSS. Recently, SS has been used as a mechanical photoswitch in various fields.25 However, to the best of our knowledge, there is only one published paper on SS-containing covalent polymers, in which a linear polymer with SS as the repeating unit was obtained by ring-opening metathesis polymerization.67 The unavailability in radical polymerization renders the use of SS in polymeric materials difficult, while HSS overcomes the drawback by the steric hindrance and promises broader applications. Importantly, isomerization of the embedded HSS hardly affected the hydrodynamic radii of the random coils (Figure 3e). Therefore, the effect on the mechanical response of HSS is unnecessary to be considered in the following ultrasonication.

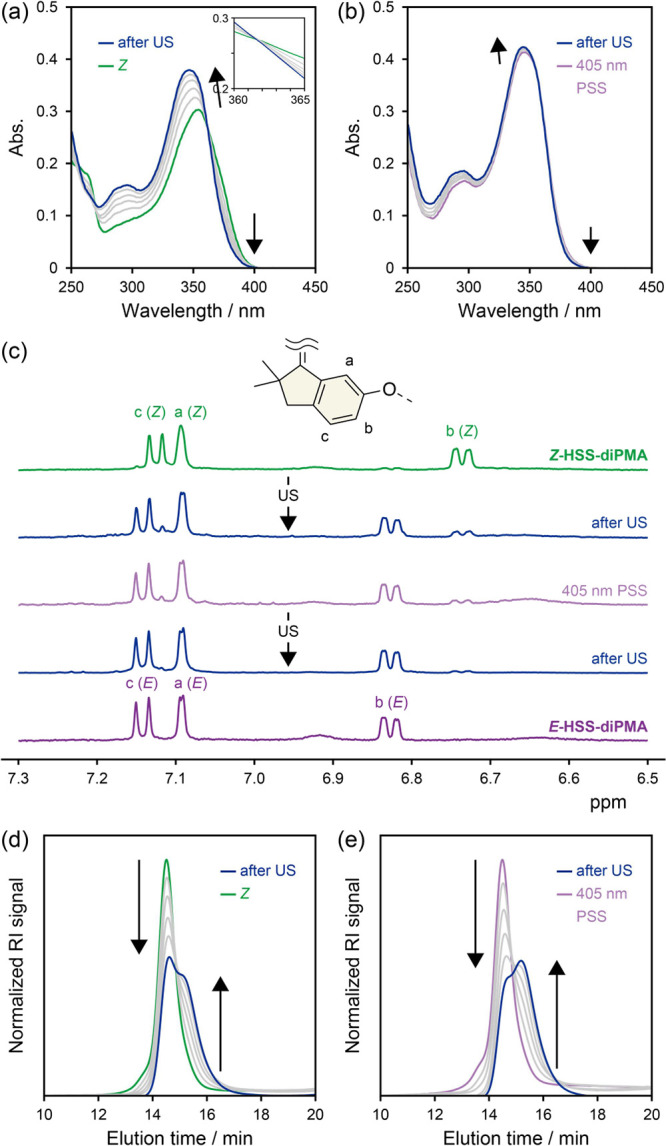

Then, we investigated the mechanical response of HSS by ultrasound irradiation in solutions, which is a common technique for applying mechanical force to a molecule centered in a polymer chain.68 THF solutions (2.00 mg mL–1) of Z-HSS-diPMA and the 405 nm PSS (82% E) were irradiated with pulsed ultrasound (5.6 W cm–2, 0–5 °C, 1 s on/0.5 s off), and UV/vis absorption and 1H NMR spectra and SEC curves were acquired. The UV/vis absorption spectra of Z-HSS-diPMA changed toward that of the E isomer similarly to the photoisomerization (Figure 4a). Although the 405 nm PSS mostly contained the E isomer, the photoabsorption spectra further approached to that of the E isomer (Figure 4b). In contrast, those of E-HSS-diPMA were almost unchanged upon ultrasonication (Figure S35). No clear isosbestic points in the photoabsorption spectra would be attributed to the degradation of PMA because a considerable increase in the absorbance in the UV region was observed even in ultrasonication of pure PMA obtained by ATRP (Mn = 107,400, PDI = 1.11, Figure S36). 1H NMR spectra after ultrasonication indicated that the Z/E ratios changed to 22/78 in Z-HSS-diPMA and from 18/82 to 7/93 in the 405 nm PSS (Figure 4c). The mechanochemical selectivity of the Z-to-E isomerization, i.e., isomerized chains vs cleaved chains, in ultrasonication of Z-HSS-diPMA for 100 min was roughly estimated to be ca. 2 from the 1H NMR spectra and SEC curves, although the value depends on sonication conditions and polymer lengths.69−71 From these results, we concluded that HSS works as a mechanophore and mechanically isomerizes only in the Z to E direction.

Figure 4.

UV/vis absorption spectra of (a) Z-HSS-diPMA and (b) 405 nm PSS during ultrasonication (US) for 100 min in THF (2.00 mg mL–1). (c) 1H NMR spectra of Z-HSS-diPMA and 405 nm PSS before and after US for 100 min (500 MHz, acetone-d6). Normalized SEC curves of (d) Z-HSS-diPMA and (e) 405 nm PSS during US for 100 min.

Ultrasound irradiation and consequent cavitation generate mechanical forces along polymer chains and cause the cleavage around the middle.68 In ultrasonication of both Z-HSS-diPMA and 405 nm PSS, the original RI peaks in the SEC curves attenuated, and a new peak corresponding to about one-half of the original molecular weights appeared and grew with irradiation time, indicating the chain scission near the center (Figure 4d,e). These results support that mechanical forces were generated around HSS centered in the polymer chains and induced the Z-to-E isomerization. To evaluate the mechanoisomerization in detail, we calculated rate constants (ks) of the polymer chain scission from the attenuation of the original RI peaks (Figure S37 and see the Supporting Information for details).71 We compared the ks of Z-HSS-diPMA and the 405 nm PSS (not E-HSS-diPMA) because degree of polymerization significantly affects k but they have the same value.69−71 The ks (mean ± standard deviation, n = 3) were determined to be 5.53 ± 1.77 × 10–3 min–1 for Z-HSS-diPMA and 6.81 ± 2.50 × 10–3 min–1 for the 405 nm PSS and considerably higher than that of the pure PMA (3.18 × 10–3 min–1, Figure S37) probably due to the preferential cleavage of the weak ester bonds in the main-chain HSS initiator.52,72−75 We had presumed that the Z-to-E mechanoisomerization should consume energy and the chain scission of Z-HSS-diPMA should be slower than that of the 405 nm PSS. However, the comparable ks would reject the hypothesis. The reason might be because the large standard deviations buried the difference, because the mechanical energy generated by the ultrasonication and cleaving the polymer chains was too high for the isomerization, or because the chain scission was not a unimolecular reaction. One reason for the large standard deviations is the high sensitivity of SEC to temperature.

To remove the possibility of thermal isomerization in ultrasonication, we also irradiated mixtures of the Z or E isomer of HSS-dimethoxy and PMA with ultrasound. The attenuation of the original RI peak in the SEC curves indicated the chain scission of PMA, but any changes originating from isomerization of HSS were not observed in the UV/vis absorption spectra (Figure S38). Therefore, the Z-to-E isomerization by ultrasonication was clearly demonstrated to be induced mechanically.

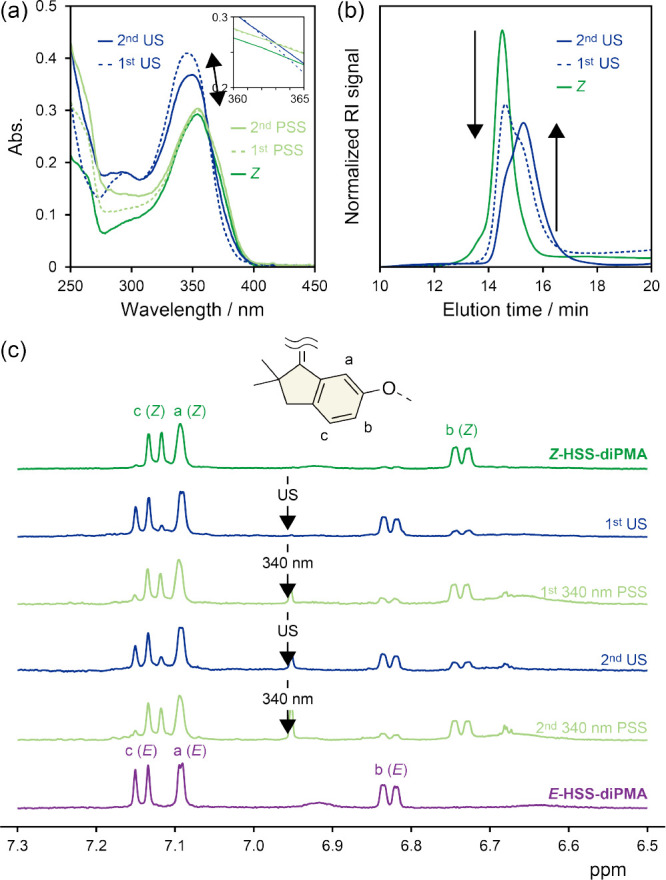

The ultrasonicated solution of Z-HSS-diPMA was further irradiated with 340 nm UV light. The mechanically isomerized HSS underwent the E-to-Z photoisomerization and still possessed the photoswitching ability (Figure S39). Thus, we investigated the repeatability of the photomechanical isomerization by alternating irradiation of Z-HSS-diPMA with ultrasound for 100 min and 340 nm UV light to be PSSs in THF (2.00 mg mL–1). The UV/vis absorption spectra indicate that the repetitive UV light irradiation induced considerable E-to-Z isomerization (Figure 5a) similarly to the 80% two-way photoisomerization (Figure 3). On the other hand, the Z-to-E mechanoisomerization by the second ultrasonication was depressed. This is because the first ultrasonication had cleaved almost half of the polymer chains around the middle, which is indicated by the SEC curves (Figure 5b), and the embedded HSS located near the chain ends in the severed chains was not subjected to mechanical forces. The 1H NMR spectra also demonstrated the reversible photomechanical isomerization (Figure 5c). Therefore, HSS was found to work as a photomechanical switch.

Figure 5.

(a) UV/vis absorption spectra, (b) normalized SEC curves, and (c) 1H NMR spectra (500 MHz, acetone-d6) of Z-HSS-diPMA upon alternating irradiation with ultrasound (US) for 100 min and 340 nm UV light to be PSSs in THF (2.00 mg mL–1).

Finally, we examined the mechanical response of HSS by stretching polymer films. We prepared Z-HSS-diPMA films with ca. 100 μm thickness by solution casting, stretched the rectangular strip specimens by a tensile machine, dissolved the fractured parts in THF after failure, and measured UV/vis absorption spectra (Figure S40). Any changes were not observed in the UV/vis absorption spectra of the Z-HSS-diPMA films after elongation, indicating that stretching the films did not induce mechanoisomerization of Z-HSS incorporated in the center of the PMA chains. Manually pressing the films using a stainless steel block and grinding them below the glass transition temperature of PMA using liquid nitrogen also induced no mechanoisomerization of the embedded Z-HSS (Figure S41). In previous papers, PMAs with one SP around the center of the polymer chains have been prepared by methods similar to the present study, and the incorporated SP isomerized to MC by stretching the films.45,46 The Mns and PDIs were almost comparable to but the mechanical properties were higher than those of Z-HSS-diPMA (Figure S40). These facts suggest a possibility that HSS is less reactive to mechanical forces than SP. Thus, we attempted to estimate the sensitivity by constrained geometries simulate external force (CoGEF) calculations for Z-HSS-dimethoxy using density functional theory at the B3LYP/6-31G(d) and UB3LYP/6-31G(d) levels (Figures S42, S43 and see the Supporting Information for details).76 However, structural changes obviously indicating the Z-to-E isomerization were not observed because the four methyl groups were on the same side until the HSS skeleton collapsed (specifically, C–C bond rupture in the five-membered rings), even when the hybrid functional was changed to dispersion and long-range corrected ones, APFD, CAM-B3LYP, and ωB97X and when two methoxy groups were attached at other positions instead of the C6 and C6’ positions (Figures S42–S49). This is probably because the common method for CoGEF calculations cannot properly describe the strong biradicaloid characters of the transition states.77,78 Nevertheless, the CoGEF calculations for Z-HSS-dimethoxy (C6 and C6′) predicted the maximum force (Fmax) and energy (Emax) to be 5.6–6.1 nN and 794–899 kJ mol–1, which are larger than those (2.6–4.8 nN and 150–386 kJ mol–1) of SP.76 This result might support the less sensitivity of HSS to mechanical forces, which would be enhanced by the introduction of more sterically bulky groups around the central C=C bond in HSS because the activation barrier in thermal isomerization of HSS was lower than that of SS.26 It is worth mentioning that the potentially less mechanochemical reactivity can be an advantage or a disadvantage depending on the applications. What is important is that the uses of HSS should be considered based on the reactivity. Additionally, there are various ways to facilitate mechanoisomerization of HSS in polymeric materials, including the introduction of complex microstructures79 observed in segmented polyurethanes80−86 and organic–inorganic composites,87 crystalline domains,88 multinetwork structures,89 and hydrogen bonding.90 Therefore, we can mechanically isomerize HSS also in materials by appropriately designing polymer and material structures.

Conclusions

In this study, we demonstrated that HSS is a mechanophore and mechanically isomerizes only in the direction from the Z isomer to the E isomer, by incorporating one Z-HSS or E-HSS into the center of PMA chains and ultrasonicating the polymer solutions to apply elongational forces to the embedded HSS. HSS was also found to reversibly isomerize by a combination of mechanical forces and UV light, i.e., work as a photomechanical hinge. Motions of previous molecular hinges are uncontrollable91−95 or controlled mainly by coordination,96,97 pH,98 and redox99 and unknown to be mechanically induced except for flapping mechanophores.86,92,94 Exceptionally, AB is known to offer photomechanically inducible hinge-like motions, however, with thermal instability.41,42,100−102 Therefore, HSS is the first thermally stable photomechanical hinge. The photomechanical hinge-like motions with high thermal stability and high isomerization yields in both directions are unique also as a photoswitch and mechanophore. We believe that HSS will be used in various materials and enable unconventional applications differently from existing photoswitches, mechanophores, and hinges.

Methods

Photoisomerization

A solution of Z-HSS-diPMA in spectrophotometric grade THF (2.00 mg mL–1) was prepared and stirred at room temperature in the dark for 1 day, and a portion of the solution was transferred to a 1.0 cm quartz cuvette with a stirring bar. The cuvette was irradiated with a light-emitting diode with a peak wavelength of 405 nm (19.6 mW cm–2, LDR2-100VL405-W1U, CCS) with stirring at room temperature to reach a PSS and, then, irradiated with a xenon light (MAX-303, Asahi Spectra) using a band pass filter for 340 nm (11.0–12.0 mW cm–2, HQBP340-UV, Asahi Spectra) with stirring at room temperature. UV/vis absorption spectra of the solution were measured during the photoirradiation. The solution of the 405 nm PSS was also used for SEC measurement as it was after 2 days at room temperature in the dark without stirring, and those of the 405 and 340 nm PSSs were used for 1H NMR measurements after concentrated, dried under vacuum, and dissolved in acetone-d6. The RI signals at 10 min in the SEC curves were corrected to 0, and the curves were normalized at the photoabsorption maximum.

Ultrasonication

Z-HSS-diPMA, the 405 nm PSS, E-HSS-diPMA, and PMA were dissolved in spectrophotometric grade THF (2.00 mg mL–1), stirred at room temperature in the dark for 1 day, and irradiated with ultrasound (5.6 W cm–2, 1 s on/0.5 s off) in an ice bath (0–5 °C) under a nitrogen atmosphere for 80 min (E-HSS-diPMA), 150 min (Z-HSS-diPMA and the 405 nm PSS), or 200 min (PMA) using a Branson Sonifier 450 sonicator with a 1.91 cm diameter solid probe. The distance between the titanium tip and bottom of the glass cell was 1 cm. The ultrasonic intensity was calibrated using a previously reported method.44 An aliquot (about 5 mL) was taken from the solutions at each irradiation time and used for UV/vis absorption and SEC measurements as it was after 2 days at room temperature in the dark without stirring. Each aliquot (50 μL) was injected by an automatic sampler in the SEC measurements. The RI signals at 10 min in the SEC curves were corrected to 0, and the curves were normalized by the integrated area. Solutions after ultrasonication were concentrated, dried under vacuum, dissolved in acetone-d6, and used for 1H NMR measurements.

Rate constants of polymer chain scission by ultrasonication were calculated from attenuation (first-order decay) of the original RI peaks in the SEC curves according to a previously reported method.71 The ks and standard deviations for Z-HSS-diPMA and the 405 nm PSS were determined by three independent experiments. Plots shown in Figure S37 provide the average value with the standard deviation for each data point (sonication time). The k for PMA was determined by one experiment.

As control experiments, mixtures of the Z or E isomers of HSS-dimethoxy (1.38 × 10–5 M) and PMA (2.00 mg mL–1) in spectrophotometric grade THF were also irradiated with ultrasound for 100 min, and UV/vis absorption spectra and SEC curves of the solutions were measured by the same procedure described above.

The Z-HSS-diPMA solution was also repeatedly irradiated with ultrasound for 100 min and the 340 nm light (11.0–12.0 mW cm–2) to be PSSs. The 1H NMR spectrum of the solution for each step was measured after the solution was concentrated, dried under vacuum, and dissolved in acetone-d6.

Acknowledgments

This work was mainly supported by JSPS KAKENHI (Grant no. 19K15623 and 21H01987) and MEXT LEADER (Grant no. A6501) and partially supported by JSPS KAKENHI (Grant no. 21H05884), JST PPRESTO (Grant no. JPMJPR21N2), Fujimori Science and Technology Foundation, Ogasawara Toshiaki Memorial Foundation, Takahashi Industrial and Economic Research Foundation, Shorai Foundation for Science and Technology, ENEOS Tonengeneral Research/Development Encouragement and Scholarship Foundation, Yazaki Memorial Foundation for Science and Technology, and International Polyurethane Technology Foundation.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/jacsau.3c00213.

Synthesis, characterization, and details of grinding tests, photoisomerization, ATRP using SS, ultrasonication, tensile tests, and CoGEF calculations (PDF)

Author Contributions

CRediT: Keiichi Imato conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, project administration, visualization, writing-original draft, writing-review & editing; Akira Ishii data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, resources, validation; Naoki Kaneda data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, resources, validation; Taichi Hidaka data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, resources, validation; Ayane Sasaki data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, resources, validation; Ichiro Imae supervision, validation; Yousuke Ooyama supervision, validation, writing-review & editing.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Costil R.; Holzheimer M.; Crespi S.; Simeth N. A.; Feringa B. L. Directing Coupled Motion with Light: A Key Step Toward Machine-Like Function. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 13213–13237. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c00340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pianowski Z. L. Recent Implementations of Molecular Photoswitches into Smart Materials and Biological Systems. Chem. – Eur. J. 2019, 25, 5128–5144. 10.1002/chem.201805814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volarić J.; Szymanski W.; Simeth N. A.; Feringa B. L. Molecular Photoswitches in Aqueous Environments. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 12377–12449. 10.1039/D0CS00547A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-López V.; Liu D.; Tour J. M. Light-Activated Organic Molecular Motors and Their Applications. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 79–124. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baroncini M.; Silvi S.; Credi A. Photo- and Redox-Driven Artificial Molecular Motors. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 200–268. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancia F.; Ryabchun A.; Katsonis N. Life-like Motion Driven by Artificial Molecular Machines. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2019, 3, 536–551. 10.1038/s41570-019-0122-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dattler D.; Fuks G.; Heiser J.; Moulin E.; Perrot A.; Yao X.; Giuseppone N. Design of Collective Motions from Synthetic Molecular Switches, Rotors, and Motors. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 310–433. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goulet-Hanssens A.; Eisenreich F.; Hecht S. Enlightening Materials with Photoswitches. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, 1905966 10.1002/adma.201905966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moulin E.; Faour L.; Carmona-Vargas C. C.; Giuseppone N. From Molecular Machines to Stimuli-Responsive Materials. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, 1906036 10.1002/adma.201906036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corra S.; Curcio M.; Baroncini M.; Silvi S.; Credi A. Photoactivated Artificial Molecular Machines That Can Perform Tasks. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, 1906064 10.1002/adma.201906064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beharry A. A.; Woolley G. A. Azobenzene Photoswitches for Biomolecules. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 40, 4422–4437. 10.1039/c1cs15023e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandara H. M. D.; Burdette S. C. Photoisomerization in Different Classes of Azobenzene. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 1809–1825. 10.1039/C1CS15179G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao M.; Kwaria D.; Norikane Y.; Yue Y. Visible-light-switchable Azobenzenes: Molecular Design, Supramolecular Systems, and Applications. Nat. Sci. 2023, 3, e220020 10.1002/ntls.20220020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bléger D.; Schwarz J.; Brouwer A. M.; Hecht S. O-Fluoroazobenzenes as Readily Synthesized Photoswitches Offering Nearly Quantitative Two-Way Isomerization with Visible Light. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 20597–20600. 10.1021/ja310323y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knie C.; Utecht M.; Zhao F.; Kulla H.; Kovalenko S.; Brouwer A. M.; Saalfrank P.; Hecht S.; Bléger D. Ortho-Fluoroazobenzenes: Visible Light Switches with Very Long-Lived Z Isomers. Chem. – Eur. J. 2014, 20, 16492–16501. 10.1002/chem.201404649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weston C. E.; Richardson R. D.; Haycock P. R.; White A. J. P.; Fuchter M. J. Arylazopyrazoles: Azoheteroarene Photoswitches Offering Quantitative Isomerization and Long Thermal Half-Lives. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 11878–11881. 10.1021/ja505444d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calbo J.; Weston C. E.; White A. J. P.; Rzepa H. S.; Contreras-García J.; Fuchter M. J. Tuning Azoheteroarene Photoswitch Performance through Heteroaryl Design. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 1261–1274. 10.1021/jacs.6b11626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crespi S.; Simeth N. A.; König B. Heteroaryl Azo Dyes as Molecular Photoswitches. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2019, 3, 133–146. 10.1038/s41570-019-0074-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Klajn R. Spiropyran-Based Dynamic Materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 148–184. 10.1039/C3CS60181A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kortekaas L.; Browne W. R. The Evolution of Spiropyran: Fundamentals and Progress of an Extraordinarily Versatile Photochrome. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2019, 48, 3406–3424. 10.1039/C9CS00203K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irie M.; Fukaminato T.; Matsuda K.; Kobatake S. Photochromism of Diarylethene Molecules and Crystals: Memories, Switches, and Actuators. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 12174–12277. 10.1021/cr500249p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J.; Tian H. The Endeavor of Diarylethenes: New Structures, High Performance, and Bright Future. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2018, 6, 1701278 10.1002/adom.201701278. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Imato K.; Nagata K.; Watanabe R.; Takeda N. Cell Adhesion Control by Photoinduced LCST Shift of PNIPAAm-Based Brush Scaffolds. J. Mater. Chem. B 2020, 8, 2393–2399. 10.1039/C9TB02958C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imato K.; Momota K.; Kaneda N.; Imae I.; Ooyama Y. Photoswitchable Adhesives of Spiropyran Polymers. Chem. Mater. 2022, 34, 8289–8296. 10.1021/acs.chemmater.2c01809. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Villarón D.; Wezenberg S. J. Stiff-Stilbene Photoswitches: From Fundamental Studies to Emergent Applications. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 13192–13202. 10.1002/anie.202001031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imato K.; Sasaki A.; Ishii A.; Hino T.; Kaneda N.; Ohira K.; Imae I.; Ooyama Y. Sterically Hindered Stiff-Stilbene Photoswitch Offers Large Motions, 90% Two-Way Photoisomerization, and High Thermal Stability. J. Org. Chem. 2022, 87, 15762–15770. 10.1021/acs.joc.2c01566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Dijken D. J.; Kovaříček P.; Ihrig S. P.; Hecht S. Acylhydrazones as Widely Tunable Photoswitches. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 14982–14991. 10.1021/jacs.5b09519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian H.; Pramanik S.; Aprahamian I. Photochromic Hydrazone Switches with Extremely Long Thermal Half-Lives. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 9140–9143. 10.1021/jacs.7b04993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao B.; Qian H.; Li Q.; Aprahamian I. Structure Property Analysis of the Solution and Solid-State Properties of Bistable Photochromic Hydrazones. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 8364–8371. 10.1021/jacs.9b03932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao B.; Aprahamian I. Hydrazones as New Molecular Tools. Chem 2020, 6, 2162–2173. 10.1016/j.chempr.2020.08.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moran M. J.; Magrini M.; Walba D. M.; Aprahamian I. Driving a Liquid Crystal Phase Transition Using a Photochromic Hydrazone. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 13623–13627. 10.1021/jacs.8b09622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryabchun A.; Li Q.; Lancia F.; Aprahamian I.; Katsonis N. Shape-Persistent Actuators from Hydrazone Photoswitches. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 1196–1200. 10.1021/jacs.8b11558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo X.; Mao T.; Wang Z.; Cheng P.; Chen Y.; Ma S.; Zhang Z. Fabrication of Photoresponsive Crystalline Artificial Muscles Based on PEGylated Covalent Organic Framework Membranes. ACS Cent. Sci. 2020, 6, 787–794. 10.1021/acscentsci.0c00260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang S.; Harris J. D.; Lambai A.; Jeliazkov L. L.; Mohanty G.; Zeng H.; Priimagi A.; Aprahamian I. Multistage Reversible Tg Photomodulation and Hardening of Hydrazone-Containing Polymers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 16348–16353. 10.1021/jacs.1c07504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu Q.; Yang S.; Gerkman M. A.; Fu H.; Aprahamian I.; Han G. G. D. Photon Energy Storage in Strained Cyclic Hydrazones: Emerging Molecular Solar Thermal Energy Storage Compounds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 12627–12631. 10.1021/jacs.2c05384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan R.; Bao J.; Li Z.; Wang Z.; Song C.; Shen C.; Huang R.; Sun J.; Wang Q.; Zhang L.; Yang H. Orthogonally Integrating Programmable Structural Color and Photo-Rewritable Fluorescence in Hydrazone Photoswitch-bonded Cholesteric Liquid Crystalline Network. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202213915 10.1002/anie.202213915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y.; Shen J.; Zhao J.; Li J.; Liu S.; Liu C.; Wei J.; Liu S.; Zhao Q. Multicolor Zinc(II)-Coordinated Hydrazone-Based Bistable Photoswitches for Rewritable Transparent Luminescent Labels. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202202655 10.1002/anie.202202655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thaggard G. C.; Leith G. A.; Sosnin D.; Martin C. R.; Park K. C.; McBride M. K.; Lim J.; Yarbrough B. J.; Kankanamalage B. K. P. M.; Wilson G. R.; Hill A. R.; Smith M. D.; Garashchuk S.; Greytak A. B.; Aprahamian I.; Shustova N. B. Confinement-Driven Photophysics in Hydrazone-Based Hierarchical Materials. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202211776 10.1002/anie.202211776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y.; Mellot G.; van Luijk D.; Creton C.; Sijbesma R. P. Mechanochemical Tools for Polymer Materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 4100–4140. 10.1039/D0CS00940G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu W.; Scofield J. M. P.; Gurr P. A.; Qiao G. G. Mechanochromophore-Linked Polymeric Materials with Visible Color Changes. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2022, 43, 2100866 10.1002/marc.202100866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surampudi S. K.; Patel H. R.; Nagarjuna G.; Venkataraman D. Mechano-Isomerization of Azobenzene. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 7519–7521. 10.1039/c3cc43797c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y.; Hansen H. R.; Brittain W. J.; Craig S. L. Strain-Dependent Kinetics in the Cis-to-Trans Isomerization of Azobenzene in Bulk Elastomers. J. Phys. Chem. B 2019, 123, 8492–8498. 10.1021/acs.jpcb.9b07088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang X.; Lv J.; Zhu C.; Qin L.; Yu Y. Photodeformable Azobenzene-Containing Liquid Crystal Polymers and Soft Actuators. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, 1904224 10.1002/adma.201904224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potisek S. L.; Davis D. A.; Sottos N. R.; White S. R.; Moore J. S. Mechanophore-Linked Addition Polymers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 13808–13809. 10.1021/ja076189x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis D. A.; Hamilton A.; Yang J.; Cremar L. D.; Gough D. V.; Potisek S. L.; Ong M. T.; Braun P. V.; Martínez T. J.; White S. R.; Moore J. S.; Sottos N. R. Force-Induced Activation of Covalent Bonds in Mechanoresponsive Polymeric Materials. Nature 2009, 459, 68–72. 10.1038/nature07970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M.; Zhang Q.; Zhou Y.-N.; Zhu S. Let Spiropyran Help Polymers Feel Force!. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2018, 79, 26–39. 10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2017.11.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kida J.; Imato K.; Goseki R.; Aoki D.; Morimoto M.; Otsuka H. The Photoregulation of a Mechanochemical Polymer Scission. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 3504. 10.1038/s41467-018-05996-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He W.; Yuan Y.; Wu M.; Li X.; Shen Y.; Qu Z.; Chen Y. Multicolor Chromism from a Single Chromophore through Synergistic Coupling of Mechanochromic and Photochromic Subunits. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202218785 10.1002/anie.202218785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robb M. J.; Kim T. A.; Halmes A. J.; White S. R.; Sottos N. R.; Moore J. S. Regioisomer-Specific Mechanochromism of Naphthopyran in Polymeric Materials. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 12328–12331. 10.1021/jacs.6b07610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFadden M. E.; Robb M. J. Force-Dependent Multicolor Mechanochromism from a Single Mechanophore. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 11388–11392. 10.1021/jacs.9b05280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Versaw B. A.; McFadden M. E.; Husic C. C.; Robb M. J. Designing Naphthopyran Mechanophores with Tunable Mechanochromic Behavior. Chem. Sci. 2020, 11, 4525–4530. 10.1039/D0SC01359E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFadden M. E.; Robb M. J. Generation of an Elusive Permanent Merocyanine via a Unique Mechanochemical Reaction Pathway. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 7925–7929. 10.1021/jacs.1c03865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFadden M. E.; Osler S. K.; Sun Y.; Robb M. J. Mechanical Force Enables an Anomalous Dual Ring-Opening Reaction of Naphthodipyran. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 22391–22396. 10.1021/jacs.2c08817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi Q.; Sekhon G.; Chandradat R.; Ofodum N. M.; Shen T.; Scrimgeour J.; Joy M.; Wriedt M.; Jayathirtha M.; Darie C. C.; Shipp D. A.; Liu X.; Lu X. Force-Induced Near-Infrared Chromism of Mechanophore-Linked Polymers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 17337–17343. 10.1021/jacs.1c05923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian H.; Purwanto N. S.; Ivanoff D. G.; Halmes A. J.; Sottos N. R.; Moore J. S. Fast, Reversible Mechanochromism of Regioisomeric Oxazine Mechanophores: Developing in Situ Responsive Force Probes for Polymeric Materials. Chem 2021, 7, 1080–1091. 10.1016/j.chempr.2021.02.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z.; Ma Z.; Wang Y.; Xu Z.; Luo Y.; Wei Y.; Jia X. A Novel Mechanochromic and Photochromic Polymer Film: When Rhodamine Joins Polyurethane. Adv. Mater. 2015, 27, 6469–6474. 10.1002/adma.201503424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T.; Zhang N.; Dai J.; Li Z.; Bai W.; Bai R. Novel Reversible Mechanochromic Elastomer with High Sensitivity: Bond Scission and Bending-Induced Multicolor Switching. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 11874–11881. 10.1021/acsami.7b00176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu M.; Guo Z.; He W.; Yuan W.; Chen Y. Empowering Self-Reporting Polymer Blends with Orthogonal Optical Properties Responsive in a Broader Force Range. Chem. Sci. 2020, 12, 1245–1250. 10.1039/d0sc06140a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu M.; Li Y.; Yuan W.; Bo G. D.; Cao Y.; Chen Y. Cooperative and Geometry-Dependent Mechanochromic Reactivity through Aromatic Fusion of Two Rhodamines in Polymers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 17120–17128. 10.1021/jacs.2c07015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H.; Diesendruck C. E. Accelerated Mechanochemistry in Helical Polymers. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202115325 10.1002/anie.202115325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Z.; Yang Q.-Z.; Khvostichenko D.; Kucharski T. J.; Chen J.; Boulatov R. Method to Derive Restoring Forces of Strained Molecules from Kinetic Measurements. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 1407–1409. 10.1021/ja807113m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Q.-Z.; Huang Z.; Kucharski T. J.; Khvostichenko D.; Chen J.; Boulatov R. A Molecular Force Probe. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2009, 4, 302–306. 10.1038/nnano.2009.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akbulatov S.; Tian Y.; Boulatov R. Force–Reactivity Property of a Single Monomer Is Sufficient To Predict the Micromechanical Behavior of Its Polymer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 7620–7623. 10.1021/ja301928d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian Y.; Kucharski T. J.; Yang Q.-Z.; Boulatov R. Model Studies of Force-Dependent Kinetics of Multi-Barrier Reactions. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 2538. 10.1038/ncomms3538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akbulatov S.; Tian Y.; Huang Z.; Kucharski T. J.; Yang Q.-Z.; Boulatov R. Experimentally Realized Mechanochemistry Distinct from Force-Accelerated Scission of Loaded Bonds. Science 2017, 357, 299–303. 10.1126/science.aan1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imato K.; Irie A.; Kosuge T.; Ohishi T.; Nishihara M.; Takahara A.; Otsuka H. Mechanophores with a Reversible Radical System and Freezing-Induced Mechanochemistry in Polymer Solutions and Gels. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 6168–6172. 10.1002/anie.201412413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan B. P.; Xue L.; Xiong X.; Cui J. Photoinduced Strain-Assisted Synthesis of a Stiff-Stilbene Polymer by Ring-Opening Metathesis Polymerization. Chem. – Eur. J. 2020, 26, 14828–14832. 10.1002/chem.202002418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May P. A.; Moore J. S. Polymer Mechanochemistry: Techniques to Generate Molecular Force via Elongational Flows. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 7497–7506. 10.1039/c2cs35463b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May P. A.; Munaretto N. F.; Hamoy M. B.; Robb M. J.; Moore J. S. Is Molecular Weight or Degree of Polymerization a Better Descriptor of Ultrasound-Induced Mechanochemical Transduction?. ACS Macro Lett. 2016, 5, 177–180. 10.1021/acsmacrolett.5b00855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer M.; Icli B.; Weder C.; Lattuada M.; Kilbinger A. F. M.; Simon Y. C. The Role of Mass and Length in the Sonochemistry of Polymers. Macromolecules 2016, 49, 1630–1636. 10.1021/acs.macromol.5b02362. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Overholts A. C.; McFadden M. E.; Robb M. J. Quantifying Activation Rates of Scissile Mechanophores and the Influence of Dispersity. Macromolecules 2022, 55, 276–283. 10.1021/acs.macromol.1c02232. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tong R.; Lu X.; Xia H. A Facile Mechanophore Functionalization of an Amphiphilic Block Copolymer towards Remote Ultrasound and Redox Dual Stimulus Responsiveness. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 3575–3578. 10.1039/c4cc00103f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karman M.; Verde-Sesto E.; Weder C. Mechanochemical Activation of Polymer-Embedded Photoluminescent Benzoxazole Moieties. ACS Macro Lett. 2018, 7, 1028–1033. 10.1021/acsmacrolett.8b00520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karman M.; Verde-Sesto E.; Weder C.; Simon Y. C. Mechanochemical Fluorescence Switching in Polymers Containing Dithiomaleimide Moieties. ACS Macro Lett. 2018, 7, 1099–1104. 10.1021/acsmacrolett.8b00591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J.; Gao X.; Boarino A.; Célerse F.; Corminboeuf C.; Klok H.-A. Mechanical Acceleration of Ester Bond Hydrolysis in Polymers. Macromolecules 2022, 55, 10145–10152. 10.1021/acs.macromol.2c01789. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Klein I. M.; Husic C. C.; Kovács D. P.; Choquette N. J.; Robb M. J. Validation of the CoGEF Method as a Predictive Tool for Polymer Mechanochemistry. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 16364–16381. 10.1021/jacs.0c06868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazaryan A.; Kistemaker J. C. M.; Schäfer L. V.; Browne W. R.; Feringa B. L.; Filatov M. Understanding the Dynamics Behind the Photoisomerization of a Light-Driven Fluorene Molecular Rotary Motor. J. Phys. Chem. A 2010, 114, 5058–5067. 10.1021/jp100609m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kistemaker J. C. M.; Pizzolato S. F.; van Leeuwen T.; Pijper T. C.; Feringa B. L. Spectroscopic and Theoretical Identification of Two Thermal Isomerization Pathways for Bistable Chiral Overcrowded Alkenes. Chem. – Eur. J. 2016, 22, 13478–13487. 10.1002/chem.201602276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imato K.; Otsuka H. Reorganizable and Stimuli-Responsive Polymers Based on Dynamic Carbon–Carbon Linkages in Diarylbibenzofuranones. Polymer 2018, 137, 395–413. 10.1016/j.polymer.2018.01.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C. K.; Davis D. A.; White S. R.; Moore J. S.; Sottos N. R.; Braun P. V. Force-Induced Redistribution of a Chemical Equilibrium. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 16107–16111. 10.1021/ja106332g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y.; Sijbesma R. P. Dioxetanes as Mechanoluminescent Probes in Thermoplastic Elastomers. Macromolecules 2014, 47, 3797–3805. 10.1021/ma500598t. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Imato K.; Kanehara T.; Nojima S.; Ohishi T.; Higaki Y.; Takahara A.; Otsuka H. Repeatable Mechanochemical Activation of Dynamic Covalent Bonds in Thermoplastic Elastomers. Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 10482–10485. 10.1039/C6CC04767J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagara Y.; Karman M.; Verde-Sesto E.; Matsuo K.; Kim Y.; Tamaoki N.; Weder C. Rotaxanes as Mechanochromic Fluorescent Force Transducers in Polymers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 1584–1587. 10.1021/jacs.7b12405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagara Y.; Traeger H.; Li J.; Okado Y.; Schrettl S.; Tamaoki N.; Weder C. Mechanically Responsive Luminescent Polymers Based on Supramolecular Cyclophane Mechanophores. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 5519–5525. 10.1021/jacs.1c01328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muramatsu T.; Okado Y.; Traeger H.; Schrettl S.; Tamaoki N.; Weder C.; Sagara Y. Rotaxane-Based Dual Function Mechanophores Exhibiting Reversible and Irreversible Responses. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 9884–9892. 10.1021/jacs.1c03790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamakado T.; Saito S. Ratiometric Flapping Force Probe That Works in Polymer Gels. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 2804–2815. 10.1021/jacs.1c12955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosuge T.; Imato K.; Goseki R.; Otsuka H. Polymer–Inorganic Composites with Dynamic Covalent Mechanochromophore. Macromolecules 2016, 49, 5903–5911. 10.1021/acs.macromol.6b01333. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Imato K.; Yamanaka R.; Nakajima H.; Takeda N. Fluorescent Supramolecular Mechanophores Based on Charge-Transfer Interactions. Chem. Commun. 2020, 56, 7937–7940. 10.1039/D0CC03126G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ducrot E.; Chen Y.; Bulters M.; Sijbesma R. P.; Creton C. Toughening Elastomers with Sacrificial Bonds and Watching Them Break. Science 2014, 344, 186–189. 10.1126/science.1248494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X.; Li J.; Wei W.; Yang F.; Wu M.; Wu Q.; Xie T.; Chen Y. Enhanced Mechanochemiluminescence from End-Functionalized Polyurethanes with Multiple Hydrogen Bonds. Macromolecules 2021, 54, 1557–1563. 10.1021/acs.macromol.0c02622. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shoji O.; Okada S.; Satake A.; Kobuke Y. Coordination Assembled Rings of Ferrocene-Bridged Trisporphyrin with Flexible Hinge-like Motion: Selective Dimer Ring Formation, Its Transformation to Larger Rings, and Vice Versa. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 2201–2210. 10.1021/ja0445746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan C.; Saito S.; Camacho C.; Irle S.; Hisaki I.; Yamaguchi S. A π-Conjugated System with Flexibility and Rigidity That Shows Environment-Dependent RGB Luminescence. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 8842–8845. 10.1021/ja404198h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones C. D.; Cook L. J. K.; Marquez-Gamez D.; Luzyanin K. V.; Steed J. W.; Slater A. G. High-Yielding Flow Synthesis of a Macrocyclic Molecular Hinge. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 7553–7565. 10.1021/jacs.1c02891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotani R.; Yokoyama S.; Nobusue S.; Yamaguchi S.; Osuka A.; Yabu H.; Saito S. Bridging Pico-to-Nanonewtons with a Ratiometric Force Probe for Monitoring Nanoscale Polymer Physics before Damage. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 303. 10.1038/s41467-022-27972-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui L.; Shinjo H.; Ichiki T.; Deyama K.; Harada T.; Ishibashi K.; Ehara T.; Miyata K.; Onda K.; Hisaeda Y.; Ono T. Highly Fluorescent Bipyrrole-Based Tetra-BF2 Flag-Hinge Chromophores: Achieving Multicolor and Circularly Polarized Luminescence. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202204358 10.1002/anie.202204358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuasa H.; Hashimoto H. Bending Trisaccharides by a Chelation-Induced Ring Flip of a Hinge-Like Monosaccharide Unit. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999, 121, 5089–5090. 10.1021/ja984062p. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haberhauer G. Control of Planar Chirality: The Construction of a Copper-Ion-Controlled Chiral Molecular Hinge. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 3635–3638. 10.1002/anie.200800062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koo C.-K.; Lam B.; Leung S.-K.; Lam M. H.-W.; Wong W.-Y. A “Molecular Pivot-Hinge” Based on the pH-Regulated Intramolecular Switching of Pt–Pt and Π–π Interactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 16434–16435. 10.1021/ja066914o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shehimy S. A.; Baydoun O.; Denis-Quanquin S.; Mulatier J.-C.; Khrouz L.; Frath D.; Dumont E.; Murugesu M.; Chevallier F.; Bucher C. Ni-Centered Coordination-Induced Spin-State Switching Triggered by Electrical Stimulation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 17955–17965. 10.1021/jacs.2c07196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagamani S. A.; Norikane Y.; Tamaoki N. Photoinduced Hinge-Like Molecular Motion: Studies on Xanthene-Based Cyclic Azobenzene Dimers. J. Org. Chem. 2005, 70, 9304–9313. 10.1021/jo0513616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bléger D.; Liebig T.; Thiermann R.; Maskos M.; Rabe J. P.; Hecht S. Light-Orchestrated Macromolecular “Accordions:” Reversible Photoinduced Shrinking of Rigid-Rod Polymers. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 12559–12563. 10.1002/anie.201106879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen T.-T.-T.; Türp D.; Wang D.; Nölscher B.; Laquai F.; Müllen K. A Fluorescent, Shape-Persistent Dendritic Host with Photoswitchable Guest Encapsulation and Intramolecular Energy Transfer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 11194–11204. 10.1021/ja2022398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.