Abstract

Photoconvertible tracking strategies assess the dynamic migration of cell populations. Here we develop phototruncation-assisted cell tracking (PACT) and apply it to evaluate the migration of immune cells into tumor-draining lymphatics. This approach is enabled by a recently discovered cyanine photoconversion reaction that leads to the two-carbon truncation and consequent blue-shift of these commonly used probes. By examining substituent effects on the heptamethine cyanine chromophore, we find that introduction of a single methoxy group increases the yield of the phototruncation reaction in neutral buffer by almost 8-fold. When converted to membrane-bound cell-tracking variants, these probes can be applied in a series of in vitro and in vivo experiments. These include quantitative, time-dependent measurements of the migration of immune cells from tumors to tumor-draining lymph nodes. Unlike previously reported cellular photoconversion approaches, this method does not require genetic engineering. Overall, PACT provides a straightforward approach to label cell populations with spatiotemporal control.

Graphical Abstract:

Cell migration is a critical component of host immunity against foreign organisms and cancer.1–2 Tumor-draining lymph nodes (TDLNs) lie immediately downstream of tumors and play an important role in cancer immunology and immunotherapy.3–5 Immune cell migration between tumors and TDLNs determines tumor immune status.6–9 However, it is difficult to quantitatively assess cell dynamics between tumors and TDLNs. Photoconvertible cell-tracking strategies allow cell types of interest to be examined with precise control.10–14 Unlike standard direct labeling (i.e., with fluorescent proteins or with antibody labeling), these strategies define the cell population to be tracked through site-specific photoconversion. Green-to-red photo-convertible proteins such as Kaede, EosFP, and Dendra2 have been explored for these applications.12, 15–21 However, these photosensitive proteins require genetic engineering, are not activated by tissue penetrant near-infrared (NIR) light, and can be rejected by immune-competent mice.22–27 Consequently, methods to facilitate in vivo cellular photoconversion experiments remain a significant need.

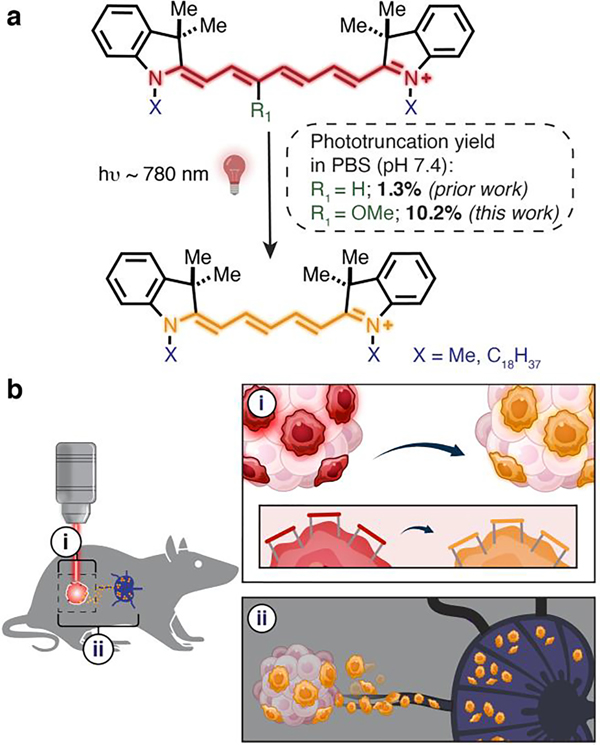

The rich photochemistry of broadly used cyanine probes has enabled applications ranging from super-resolution microscopy to in vivo drug delivery.28–31 We recently found that the hypsochromic photoconversion (i.e. “photoblueing”) of cyanines involves a previously uncharacterized phototruncation reaction (Figure 1a).32,33 This chemistry, mediated by singlet oxygen, involves the formal excision of ethene diradical from the polymethine chain resulting in the two-carbon truncated homologue.33 We demonstrated that cyanine phototruncation could be applied for single-molecule localization microscopy (SMLM) applications.33 However, the modest yield of the cyanine photoconversion reaction in neutral buffer limited the scope of this photoconversion chemistry.

Figure 1.

a) Cyanine phototruncation reaction. b) Depiction of the application of (i) spatially controlled PACT to (ii) cellular migration from tumor to TDLN.

Here we report the development of phototruncation-assisted cell tracking (PACT) (Figure 1a,b). Enabled by efforts that significantly improve the yield of cyanine phototruncation, we apply this chemistry to cell-tracking applications and employ it to examine immune cell migration from the tumor to the TDLN. Building on our prior observation that additives, pH and buffers dramatically impact phototruncation yield, we hypothesized that substituting the cyanine chromophore might impact reaction conversion in neutral aqueous conditions.33 We find that 3’-OMe-substitution on the polymethine chain leads to a dramatic increase (~ 8×) under physiological conditions. We then demonstrate that PACT can be implemented in vivo through intratumoral injection of a 3’-OMe-variant of the cell-tracking DiR dye to track immune cell migration into TDLNs. These studies provide a quantitative means for the temporal characterization of the tumor-derived immune-cell population in the TDLN.

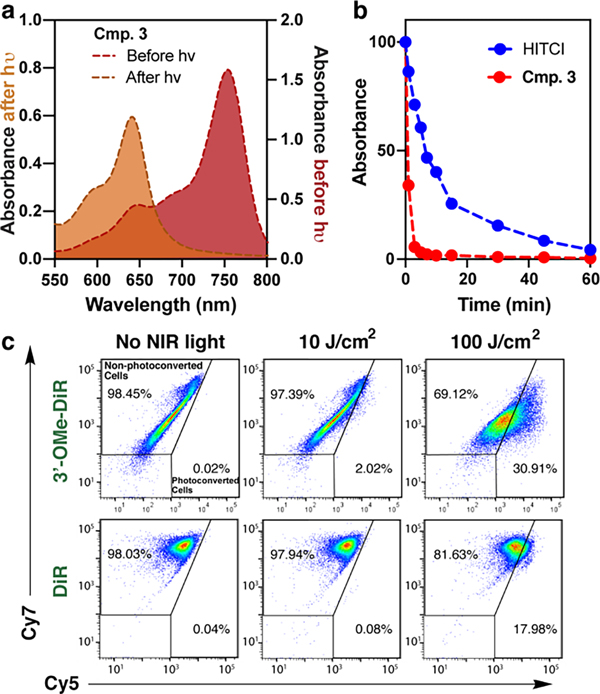

We first set out to improve the yield of phototruncation in neutral buffer. These studies involved examining a series of 3’ 4’, and 5’-substituted cyanines, which were prepared using a recently described method and whose spectral properties are well documented.34–35 Following LED irradiation of 50 μM solution (PBS, pH = 7.4, 37 °C), the yield of the pentamethine product was assessed by UV-vis spectroscopy (Table 1, Figure S1). While the yield of the conversion of the parent probe was modest (1.3% ± 0.12%), we identified several substituents that significantly improved the yield (Table 1). Most dramatically, 3’-OMe substitution led to a roughly 8-fold improvement in the phototruncation yield (10.2 ± 0.92%, Figure 2a). LC-MS analysis of the phototruncated product found the major product was the parent pentamethine cyanine lacking polymethine substitution (Figure S2). In our prior report, we proposed a computationally supported mechanism involving an exothermic 4-membered-ring-driven elimination of oxidized ethene.33 This involved the asynchronous attack of 1O2 at C1’ on the polymethine (Figure S3). However, the formation of the non-substituted pentamethine suggests that 1O2 modifies C3’ on the polymethine, presumably due to electrophilicity imposed by 3’-OMe substitution. Irradiation experiments monitoring the disappearance of the parent heptamethine reveals the 3’-OMe derivative is photoconverted more efficiently the unsubstituted dye (Figure 2b). This observation is likely due to the effect of increased electron-density in the chromophore on 1O2 reactivity, as observed in prior studies.36

Table 1:

Phototruncation yield of substituted heptamethine cyanines.

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Cmp. | R1 | R2 | R3 | Yielda |

|

| ||||

| HITCI | H | H | H | 1.3 ± 0.12 |

| 1 | I | H | H | 0.3 ± 0.01 |

| 2 | CN | H | H | 0.7 ± 0.03 |

| 3 | MeO | H | H | 10.2 ± 0.92 |

| 4 | COOMe | H | H | 4.4 ± 0.21 |

| 5 | H | COOH | H | 4.1 ± 0.02 |

| 6 | H | COMe | H | 4.5 ± 0.04 |

| 7 | H | COOMe | H | 2.4 ± 0.11 |

| 8 | Br | H | Me | 1.8 ± 0.02 |

| 9 | F | H | H | 0.5 ± 0.02 |

| 10 | Ph | H | H | 0.4 ± 0.01 |

| 11 | MeO | COOMe | H | 1.1 ± 0.03 |

| 12 | Me | CN | H | 0.2 ± 0.10 |

| 13 | OMe | CN | H | 0.2 ± 0.01 |

| 14 | H | CN | H | 0.1 ± 0.01 |

| 15 | Br | H | H | 1.1 ± 0.08 |

| 16 | Me | H | H | 0.8 ± 0.03 |

| 17 | H | EtO | H | 1.1 ± 0.06 |

| 18 |

|

0.4 ± 0.03 | ||

| 19 |

|

0.9 ± 0.15 | ||

| 20 |

|

1.2 ± 0.09 | ||

A 50 μM solution of cyanines in the PBS (10 mM; pH = 7.4) buffer was prepared from a 5 mM DMSO stock solution. Irradiations were conducted at 22 °C using either 690, 730, or 780 nm LED (0.5 W/cm2, 1 h). The sample was then analyzed by UV-vis absorbance, and the yield was determined assuming that the peak at 650 nm is the unsubstituted pentamethine product (See Figure S1).

Figure 2.

a) Absorbance curves of 3 (R1 = OMe, R2 = H) before and after irradiation with 730 nm LED (500 mW/cm2 for 1 h (50 μM, pH 7.4 PBS). b) Samples of 3 and HITCl (50 μM, pH 7.4 PBS) were irradiated with a 730 nm LED (50 mW/cm2) for up to 1 h and monitored by UV-vis absorbance designated time intervals. c) Cellular photoconversion data. MC38 cells were incubated with PBS containing 3’-OMe-DiR (20 μM) or DiR (20 μM) for 30 min at 37 °C. The cells were then washed with PBS containing 1% FBS twice and then exposed to NIR light at 10 and 100 J/cm2 (780 nm, 150 mW/cm2). Photoconversion was analyzed by flow cytometry using Cy7 and Cy5 filter sets with identical gating (Figure S4)

Cyanines substituted with C18 alkyl chains are broadly used plasma membrane cell labeling probes and track individual cell populations for several days without effect on their homing or proliferation.13, 37–38 Prior to our report of the underlying phototruncation chemistry, two studies observed a hypsochromic photoconversion of cells labeled with the heptamethine cyanine (i.e., DiR) dye.39–40 While establishing the feasibility of this approach, the modest conversion of the DiR affected detection efficiency. Based on the outcome of our optimization efforts, we synthesized 3’-OMe-DiR (See Supplementary Information) and evaluated its potential for PACT. We first established hepta-to-pentamethine cyanine phototruncation in a series of in vitro studies. The effect of irradiation on 3’-OMe-DiR or DiR labeled EL4 and MC38 cells was first assessed by fluorescence microscopy (Figure S5). Dramatically higher time-dependent fluorescence in the Cy5 channel was observed in cells stained with 3’-OMe-DiR. In line with our initial photoirradiation experiment, fluorescent signal remained in the Cy7 channel for the DiR-labeled samples under these conditions (50 J/cm2). We then evaluated the fraction of phototruncated cells by flow cytometry using the commonly found allophycocyanin (APC) and APC-Cy7 filter set for penta- and hepta-methine cyanines, respectively. We observed significant increases in the fraction of cells in the Cy5 channel following 780 nm irradiation with both probes, however, the conversion was much more efficient for 3’-OMe-DiR (Figure 2c and Figure S6). We also established that light exposure had a negligible effect on the cell viability (Figure S7) up to 100 J/cm2. These experiments demonstrate the potential for cellular phototruncation, and that flow cytometry provides straightforward means to assess photoconversion efficiency.

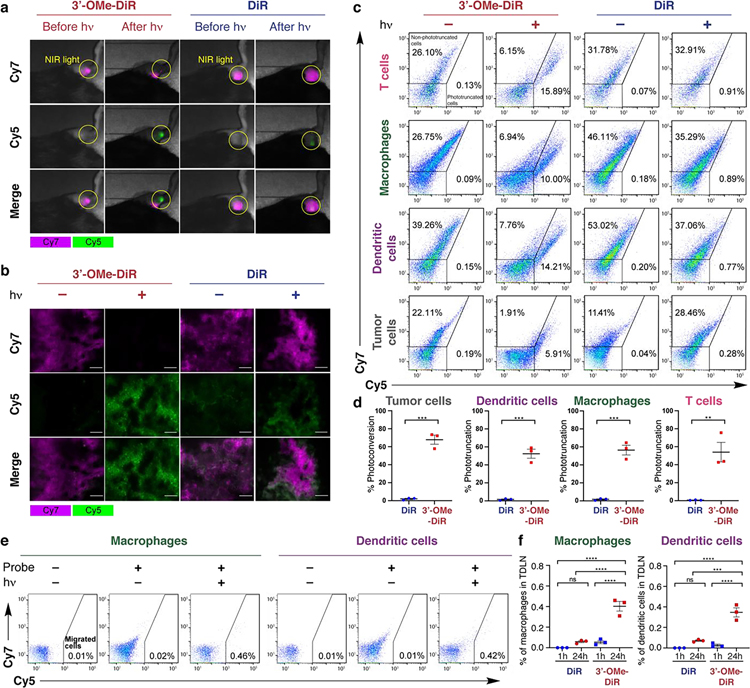

To investigate the potential for in vivo PACT, the probes (10 nmol) were injected into the tumor in the right lower limb of the C57BL/6 mice bearing MC38 xenograft tumors. After 1 h, the tumor was selectively irradiated with an external laser source (780 nm, 150 mW/cm2, 100 J/cm2, 65 sec). Subsequent in vivo fluorescence imaging showed significant photoconversion in the case of 3’-OMe-DiR dye (Figure 3a, Figure S8), which was also confirmed in the fluorescence microscopy of frozen tumor slices (Figure 3b). We then tested the efficiency of PACT in discrete cell types in the tumor bed. A single cell suspension of the tumor was analyzed by flow cytometry using standard immunolabeling procedures. Key immune cells (T-cell, dendritic cells, and macrophages), as well as the tumor cells exhibited quantifiable photoconversion, with improved conversion with the 3’-OMe-DiR variant (Figure 3c–d). These results demonstrate that 3’-OMe substitution provides critical improvements in photoconversion yield relative to the parent DiR probe and establishes the potential for in vivo PACT.

Figure 3.

a) Fluorescence imaging of photoconversion in MC38 tumors (implanted in the right lower limb). After intra-tumoral injection of 3’-OMe-DiR or DiR, fluorescence images were acquired with Cy5 and Cy7 filter settings just before and after NIR light exposure (in yellow circle). b) Fluorescence microscopy of frozen sections of MC38 tumors. After intra-tumoral injection of 3’-OMe-DiR or DiR, the tumor was exposed to NIR light. Frozen sections of the tumor were prepared and observed with a fluorescence microscope. Cy5 and Cy7 fluorescence are shown in magenta and green, respectively. Representative pictures are shown (images; ×200; scale bar, 100 μm). c-d) Flow-cytometric analysis of photoconversion in MC38 tumors. After intra-tumoral injection of 3’-OMe-DiR or DiR, the tumor was exposed to NIR light, followed by the preparation of a single-cell suspension of the tumor. Representative dot plots (c) and comparison of photoconversion rates between 3’-OMe-DiR and DiR (D; n = 3; unpaired t test; **, P < 0.01, ***, P < 0.001) were shown for T cells, macrophages, dendritic cells, and tumor cells. Photoconversion rates were calculated as ((photoconverted cell number)/(sum of non-photoconverted and photoconverted cell numbers)) × 100. e-f) Tracking of photoconverted intra-tumoral immune cells migrated into tumor-draining lymph nodes in MC38 cells. Tumors were exposed to NIR light after intra-tumoral injection of 3’-OMe-DiR or DiR (see methods section). Tumor-draining lymph nodes were harvested 1 h and 24 h after NIR light exposure. e) Representative dot plots of migrated macrophages and dendritic cells with 3’-OMe-DiR 24 h after NIR light exposure. f) Comparison of rates of migrated cells among the mice with 3’-OMe-DiR and DiR staining 1 h and 24 h after NIR light exposure (F; n = 3; one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test; ***, P < 0.001, ****, P < 0.0001) were shown.

PACT was then applied to investigate cell migration from MC38 and LL/2-luc tumors (inoculated in the right dorsum) to TDLNs. To track the migration of the intratumoral immune cells, the TDLN (at approx. 1.5 cm) was extracted 1 and 24 h after NIR light exposure (as described above), and a single-cell suspension was obtained. Subsequent flow cytometry analysis identified labeled, photoconverted tumor cells and immune cells including macrophages and dendritic cells 24 h, but not 1 h, post-injection (Figure 3e–f, Figure S9–10). Critically, without photoconversion, the initial transfer of the cell labeling dye throughout the tumor and TDLN make it impossible to clearly define the migrated cell population (up to 0.06% of non-photoconverted cells at 1 h, Figure S9–10). These efforts establish a means to quantify the relative abundance of tumor-derived macrophages and dendritic cells in the TDLN.

In conclusion, we demonstrate that PACT can facilitate irradiation-dependent cell tracking experiments without genetic modification. These studies were enabled by efforts to examine the role of chromophore substitution, which found that 3’-OMe substitution significantly improves the yield of photoconversion. Motivated by the key role of TDLNs in tumor immune status, we apply PACT to track the migration of innate immune cells from tumors to the TDLNs. This approach represents an easily implemented method for investigating in vivo cell migration from a specific location of interest. These PACT experiments rely on commonly used laser/filter sets found on numerous instruments and may be coupled with fluorescence-activated single-cell sorting (FACS) for further analysis of PACT-labeled cells. We note that, while this photoconversion reaction is O2 dependent, prior work has shown the biologically relevant hypoxia does not significant impact cyanine photooxidation chemistry.36 Going forward, the development of antibody-targeted variants of the 3’-OMe-substituted probes would extend this approach to address cellular migration in an antigen-specific manner. Efforts are currently underway to further define and optimize the underlying chemistry and apply this approach to characterize immune cell and other dynamic migration processes.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), NCI-CCR. P.K. and L.Š. thank the CETOCOEN EXCELLENCE Teaming 2 project (supported by the Czech Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports: CZ.02.1.01/0.0/0.0/17_043/0009632) and the RECETOX research infrastructure (LM2018121). We also thank Radek Tovtik (Masaryk University) for the purification of some Cy7 derivatives. The Biophysics Resource, CCR is acknowledged for use of instrumentation. The table of contents graphic was generated using Biorender.com.

ABBREVIATIONS

- PACT

Phototruncation-assisted cell tracking

- TDLN

tumor draining lymph node

- FACS

fluorescence-activated single-cell sorting

- HITCI

1,1’,3,3,3’,3’-Hexamethylindotricarbocyanine iodide

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website.

Additional experimental details, supplemental figures, materials and methods, including the synthetic details and characterization of 3’-OMe-DiR

Contributor Information

Hiroshi Fukushima, Molecular Imaging Branch, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, NIH, Bethesda, MD, 20892, USA..

Siddharth S. Matikonda, Chemical Biology Laboratory, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Frederick, Maryland 21702, USA..

Syed Muhammad Usama, Chemical Biology Laboratory, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Frederick, Maryland 21702, USA..

Aki Furusawa, Molecular Imaging Branch, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, NIH, Bethesda, MD, 20892, USA..

Takuya Kato, Molecular Imaging Branch, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, NIH, Bethesda, MD, 20892, USA..

Lenka Štacková, Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Science, Masaryk University, Kamenice 5, 625 00 Brno, Czech Republic & RECETOX, Faculty of Science, Masaryk University, Kamenice 5, 625 00 Brno, Czech Republic..

Petr Klán, Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Science, Masaryk University, Kamenice 5, 625 00 Brno, Czech Republic & RECETOX, Faculty of Science, Masaryk University, Kamenice 5, 625 00 Brno, Czech Republic..

Hisataka Kobayashi, Molecular Imaging Branch, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, NIH, Bethesda, MD, 20892, USA.

Martin J. Schnermann, Chemical Biology Laboratory, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Frederick, Maryland 21702, USA

REFERENCES

- 1.Luster AD; Alon R; von Andrian UH, Immune cell migration in inflammation: present and future therapeutic targets. Nat. Immunol. 2005, 6 (12), 1182–1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu J; Zhang X; Cheng Y; Cao X, Dendritic cell migration in inflammation and immunity. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2021, 18 (11), 2461–2471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fransen MF; van Hall T; Ossendorp F, Immune Checkpoint Therapy: Tumor Draining Lymph Nodes in the Spotlights. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22 (17), 9401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marzo AL; Lake RA; Lo D; Sherman L; McWilliam A; Nelson D; Robinson BW; Scott B, Tumor antigens are constitutively presented in the draining lymph nodes. J. Immunol. 1999, 162 (10), 5838–5845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goode EF; Roussos Torres ET; Irshad S, Lymph Node Immune Profiles as Predictive Biomarkers for Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Response. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2021, 8, 382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Riedel A; Shorthouse D; Haas L; Hall BA; Shields J, Tumor-induced stromal reprogramming drives lymph node transformation. Nat. Immunol. 2016, 17 (9), 1118–1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gray EE; Cyster JG, Lymph node macrophages. J. Innate Immun. 2012, 4 (5–6), 424–436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Munn DH; Mellor AL, The tumor-draining lymph node as an immune-privileged site. Immunol. Rev. 2006, 213 (1), 146–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hampton HR; Chtanova T, Lymphatic migration of immune cells. Front. immunol. 2019, 10, 1168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hatta K; Tsujii H; Omura T, Cell tracking using a photoconvertible fluorescent protein. Nat. Protoc. 2006, 1 (2), 960–967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nienhaus GU; Nienhaus K; Hölzle A; Ivanchenko S; Renzi F; Oswald F; Wolff M; Schmitt F; Röcker C; Vallone B, Photoconvertible fluorescent protein EosFP: biophysical properties and cell biology applications. Photochem. Photobiol. 2006, 82 (2), 351–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tomura M; Hata A; Matsuoka S; Shand FH; Nakanishi Y; Ikebuchi R; Ueha S; Tsutsui H; Inaba K; Matsushima K, Tracking and quantification of dendritic cell migration and antigen trafficking between the skin and lymph nodes. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4 (1), 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Progatzky F; Dallman MJ; Lo Celso C, From seeing to believing: labelling strategies for in vivo cell-tracking experiments. Interface Focus 2013, 3 (3), 20130001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kedrin D; Gligorijevic B; Wyckoff J; Verkhusha VV; Condeelis J; Segall JE; Van Rheenen J, Intravital imaging of metastatic behavior through a mammary imaging window. Nat. Methods 2008, 5 (12), 1019–1021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mellott AJ; Shinogle HE; Moore DS; Detamore MS, Fluorescent Photo-conversion: A second chance to label unique cells. Cell. Mol. Bioeng. 2015, 8 (1), 187–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hampton HR; Bailey J; Tomura M; Brink R; Chtanova T, Microbe-dependent lymphatic migration of neutrophils modulates lymphocyte proliferation in lymph nodes. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6 (1), 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tomura M; Yoshida N; Tanaka J; Karasawa S; Miwa Y; Miyawaki A; Kanagawa O, Monitoring cellular movement in vivo with photoconvertible fluorescence protein “Kaede” transgenic mice. PNAS 2008, 105 (31), 10871–10876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Torcellan T; Hampton HR; Bailey J; Tomura M; Brink R; Chtanova T, In vivo photolabeling of tumor-infiltrating cells reveals highly regulated egress of T-cell subsets from tumors. PNAS 2017, 114 (22), 5677–5682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ando R; Hama H; Yamamoto-Hino M; Mizuno H; Miyawaki A, An optical marker based on the UV-induced green-to-red photoconversion of a fluorescent protein. PNAS 2002, 99 (20), 12651–12656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zimmer M, GFP: from jellyfish to the Nobel prize and beyond. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009, 38 (10), 2823–2832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Day RN; Davidson MW, The fluorescent protein palette: tools for cellular imaging. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009, 38 (10), 2887–2921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bresser K; Dijkgraaf FE; Pritchard CE; Huijbers IJ; Song J-Y; Rohr JC; Scheeren FA; Schumacher TN, A mouse model that is immunologically tolerant to reporter and modifier proteins. Commun. Biol. 2020, 3 (1), 1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gambotto A; Dworacki G; Cicinnati V; Kenniston T; Steitz J; Tüting T; Robbins P; DeLeo A, Immunogenicity of enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) in BALB/c mice: identification of an H2-K d-restricted CTL epitope. Gene Ther. 2000, 7 (23), 2036–2040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Han W; Unger W; Wauben M, Identification of the immunodominant CTL epitope of EGFP in C57BL/6 mice. Gene Ther. 2008, 15 (9), 700–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Limberis M; Bell C; Wilson J, Identification of the murine firefly luciferase-specific CD8 T-cell epitopes. Gene Ther. 2009, 16 (3), 441–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lippincott-Schwartz J; Patterson GH, Photoactivatable fluorescent proteins for diffraction-limited and super-resolution imaging. Trends Cell Biol. 2009, 19 (11), 555–565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shcherbakova DM; Subach OM; Verkhusha VV, Red fluorescent proteins: advanced imaging applications and future design. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51 (43), 10724–10738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gorka AP; Nani RR; Schnermann MJ, Cyanine polyene reactivity: scope and biomedical applications. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2015, 13 (28), 7584–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gorka AP; Nani RR; Schnermann MJ, Harnessing cyanine reactivity for optical imaging and drug delivery. Acc. Chem. Res. 2018, 51 (12), 3226–3235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jradi FM; Lavis LD, Chemistry of Photosensitive Fluorophores for Single-Molecule Localization Microscopy. ACS Chem. Biol. 2019, 14 (6), 1077–1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eiring P; McLaughlin R; Matikonda SS; Han Z; Grabenhorst L; Helmerich DA; Meub M; Beliu G; Luciano M; Bandi V; Zijlstra N; Shi Z-D; Tarasov SG; Swenson R; Tinnefeld P; Glembockyte V; Cordes T; Sauer M; Schnermann MJ, Targetable Conformationally Restricted Cyanines Enable Photon-Count-Limited Applications. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60 (51), 26685–26693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Helmerich DA; Beliu G; Matikonda SS; Schnermann MJ; Sauer M, Photoblueing of organic dyes can cause artifacts in super-resolution microscopy. Nat. Methods 2021, 1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Matikonda SS; Helmerich DA; Meub M; Beliu G; Kollmannsberger P; Greer A; Sauer M; Schnermann MJ, Defining the Basis of Cyanine Phototruncation Enables a New Approach to Single-Molecule Localization Microscopy. ACS Cent. Sci. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Štacková L; Muchová E; Russo M; Slavíček P; Štacko P; Klán P, Deciphering the structure–property relations in substituted heptamethine cyanines. J. Org. Chem. 2020, 85 (15), 9776–9790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Štacková L; Štacko P; Klán P, Approach to a substituted heptamethine cyanine chain by the ring opening of zincke salts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141 (17), 7155–7162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nani RR; Gorka AP; Nagaya T; Yamamoto T; Ivanic J; Kobayashi H; Schnermann MJ, In Vivo Activation of Duocarmycin-Antibody Conjugates by Near-Infrared Light. Acs Central Sci 2017, 3 (4), 329–337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Celso CL; Fleming HE; Wu JW; Zhao CX; Miake-Lye S; Fujisaki J; Côté D; Rowe DW; Lin CP; Scadden DT, Live-animal tracking of individual haematopoietic stem/progenitor cells in their niche. Nature 2009, 457 (7225), 92–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kalchenko V; Shivtiel S; Malina V; Lapid K; Haramati S; Lapidot T; Brill AG; Harmelin A, Use of lipophilic near-infrared dye in whole-body optical imaging of hematopoietic cell homing. J. Biomed. Opt. 2006, 11 (5), 050507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carlson AL; Fujisaki J; Wu J; Runnels JM; Turcotte R; Celso CL; Scadden DT; Strom TB; Lin CP, Tracking single cells in live animals using a photoconvertible near-infrared cell membrane label. PLoS One 2013, 8 (8), e69257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Osseiran S; Austin LA; Cannon TM; Yan C; Langenau DM; Evans CL, Longitudinal monitoring of cancer cell subpopulations in monolayers, 3D spheroids, and xenografts using the photoconvertible dye DiR. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9 (1), 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.