Abstract

Objective:

To evaluate low gestational weight gain (GWG) in women who use electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes), combustible cigarettes, or both e-cigarettes and combustible cigarettes (dual use) during pregnancy.

Methods:

We conducted a secondary analysis of the data from 176,882 singleton pregnancies in 2016–2020 U.S. Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS). Postpartum women self-reported their use of e-cigarettes and/or cigarettes during the last 3 months of pregnancy. Low GWG was defined as the total GWG <28, <25, <15, and <11 pounds for women with underweight, normal weight, overweight, and obesity, respectively. We used multivariable logistic regression to estimate the odds ratios (ORs) of low GWG, adjusting for confounders.

Results:

In this national sample, 921 (weighted percentage, 0.5%) of women were e-cigarette users and 1308 (0.7%) were dual users during late pregnancy. Compared with non-users during late pregnancy (40 090, 22.1%), cigarette users (4499, 28.0%) and dual users (427, 26.0%) had a higher risk of low GWG, but e-cigarette users had a similar risk (237, 22.1%). Adjustment for socio-demographic and pregnancy confounders moderately attenuated these associations: confounder-adjusted OR, 1.26 [1.18–1.35] for cigarette users, 1.18 [0.96–1.44] for dual users, and 0.99 [0.78–1.27] for e-cigarette users.

Conclusion:

Unlike combustible cigarette use, e-cigarette use during late pregnancy does not appear to be a risk factor for low GWG.

Keywords: PRAMS, E-cigarettes, electronic cigarettes, ENDS, cigarettes, tobacco, smoking, gestational weight gain, pregnancy, BMI

INTRODUCTION

Adequate gestational weight gain (GWG) is important for the health and development of the fetus.1 Low GWG can lead to preterm birth,2 low birth weight (LBW),2 small for gestational age (SGA),2 and failure to initiate breastfeeding.3 In 2009, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) released updated recommendations for GWG.3 The recommendations were based on pre-pregnancy BMI, which is a strong predictor for GWG.4

Besides pre-pregnancy BMI, other factors such as genetics, environment, medical and psychological conditions, diet, and substance use including combustible cigarettes (we will use “cigarettes” for the rest of the manuscript) can influence the amount of GWG. Smoking during pregnancy is common among U.S. women:5 highest during the first trimester (7.1%) and then decreasing in the second (6.1%) and third (5.7%) trimesters.6 Maternal smoking is associated with preterm birth, stillbirth, fetal growth restriction,7 and low GWG.8

In the past decade, there has been growing popularity of the use of electronic cigarettes (“e-cigarettes” used for the rest of the manuscript) or vaping, among young women and adolescents.9 E-cigarettes are battery-powered devices that heat liquids (mostly nicotine containing) creating aerosols that can be inhaled.10 Some previous smokers of cigarettes may switch to using e-cigarettes during pregnancy with the perception of reducing potential harms to the fetus.11 There is increasing evidence on adverse birth outcomes in offspring being associated with use of e-cigarettes during pregnancy.12 On the other hand, there is limited research on the relationship between e-cigarette use and maternal outcomes such as GWG in mothers. With the experimental use of e-cigarettes in some existing smoking cessation programs,13 more research is needed to better inform users of the possible health effects of e-cigarette use, given that e-cigarettes are relatively new products with less information compared with cigarettes.

Therefore, we aimed to examine the associations of e-cigarette, combustible cigarette, and dual use during late pregnancy with the risk of low GWG.

METHODS

Study design and population

We conducted secondary data analysis using the phase 8 data of Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS, 2016–2020). PRAMS is an ongoing state-based surveillance system managed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the health departments of participating sites including 47 states, the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and the Great Plains Tribal Chairman’s Health Board.14 About 83% of all U.S. live births are covered by the PRAMS surveillance. The goal of PRAMS is to reduce infant mortality and low birth weight as well as to promote safe motherhood. It collects comprehensive data on maternal behaviors, attitudes, and experiences before, during, and shortly after pregnancy via birth certificate records and questionnaire surveys (mail and telephone).

For the purpose of this analysis, we used the most recent phase 8 (2016–2020) PRAMS data, because questions concerning e-cigarette use during pregnancy were first included in the core questionnaire for all participating sites in 2016. We restricted our analysis to singleton births, as the definition of low GWG for a multiple pregnancy is different from that of a singleton pregnancy.3 Of the 206,080 live births in the original phase 8 PRAMS data, 7,038 multiple births were excluded. From the remaining 194,796 singleton births the women must have had complete data for 1) e-cigarette and cigarette use during late pregnancy (exposures), 2) pre-pregnancy BMI, and 3) total GWG in order to define low GWG (outcome). After applying these criteria, 176,882 were included in the analysis. The de-identified PRAMS data were provided by the CDC. This data analysis was approved as non-human-subject research by University at Buffalo Institutional Review Board. An informed consent was not needed and thus not obtained.

Exposure measures

Concerning e-cigarette use, women were asked the following question, “During the last 3 months of your pregnancy, on average, how often did you use e-cigarettes or other electronic nicotine products?” For cigarette use, women were asked the following question, “In the last 3 months of your pregnancy, how many cigarettes did you smoke on an average day?”

Based on the women’s original answers to these questions, we created binary variables (any use/non-use) to indicate their status of e-cigarette/cigarette use during the last 3 months of pregnancy. Accordingly, we categorized women into 4 groups based on their e-cigarette/cigarette use: non-users of either e-cigarettes or cigarettes, exclusive users of e-cigarettes, exclusive users of cigarettes, and dual users of both e-cigarettes and cigarettes.

Outcome measures

According to the IOM’s guidelines,3 the definition of low GWG varied by pre-pregnancy BMI. We first calculated BMI from self-reported weight before pregnancy and height on birth certificates, using the formula BMI = weight in kg/ (height in meters)2. Then, we classified pre-pregnancy BMI into 4 categories: underweight (<18.5 kg/m2), normal weight (18.5–24.9 kg/m2), overweight (25.0–29.9 kg/m2), and obese (≥30.0 kg/m2). We calculated the total GWG as the difference between pre-pregnancy weight and weight before delivery. Low GWG was defined as the total GWG <28, <25, <15, and <11pounds for women with underweight, normal weight, overweight, and obesity, respectively.

Confounders

We considered confounders that were reported to be associated with both e-cigarette/cigarette use (exposure) and low GWG (outcome) in the literature. We required these confounders to occur before pregnancy to avoid inclusion of potential mediators. We considered the following potential confounders: maternal age (≤19, 20–24, 25–29, ≥30 years),15 education (high school or lower, associate degree or some college, bachelors or higher),16 race (White, Black, American Indian/Alaskan, Asian, other non-White, mixed race),16 marital status (unmarried/married),17 type of health insurance (Medicaid, private insurance, self-pay, other),18 pre-pregnancy hypertension (yes/no),19 pre-pregnancy diabetes (yes/no),20 pre-pregnancy BMI (underweight, normal weight, overweight, obese).21 Women reported the information on these variables on birth certificates or survey questionnaires.

Statistical Analysis

We first conducted descriptive analyses to summarize socio-demographic and pregnancy characteristics (Table 1). Frequencies and percentages were used for categorical variables. Means and standard deviation (SD) were used for continuous variables. We then conducted Chi-squared tests to compare the distributions of e-cigarette and cigarette use during pregnancy by these characteristics (Table 2). Similarly, Chi-squared tests were used to identify the significant correlates of low GWG (Table 3).

Table 1.

Characteristics of women with live singleton births (N=176,882)

| Characteristic* | n (%) | Weighted % |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Age, years | ||

| ≤19 | 8,082 (4.6) | 4.2 |

| 20–24 | 32,688 (18.5) | 18.4 |

| 25–29 | 51,496 (29.1) | 29.1 |

| ≥30 | 84,608 (47.8) | 48.2 |

| Education | ||

| High school or lower | 62,131 (35.4) | 35.1 |

| Associates degree or some college | 51,402 (29.3) | 27.5 |

| Bachelors or higher | 62,085 (35.4) | 37.5 |

| Race | ||

| White | 102,955 (58.7) | 70.0 |

| Black | 33,227 (18.9) | 15.6 |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 7,974 (4.5) | 0.9 |

| Asian | 12,578 (7.2) | 5.4 |

| Other non-White | 8,427 (4.8) | 5.1 |

| Mixed race | 10,347 (5.9) | 2.9 |

| Marital status | ||

| Unmarried | 71,419 (40.4) | 37.9 |

| Married | 105,353 (59.6) | 62.1 |

| Type of health insurance | ||

| Medicaid | 75,647 (43.0) | 40.2 |

| Private insurance | 88,420 (50.3) | 53.6 |

| Self-pay | 4,715 (2.7) | 2.9 |

| Other | 7,042 (4.0) | 3.4 |

| Pre-pregnancy hypertension | 20,644 (11.7) | 9.6 |

| Pre-pregnancy diabetes | 12,977 (7.4) | 6.9 |

| Pre-pregnancy BMI | ||

| Underweight | 6,550 (3.7) | 3.5 |

| Normal weight | 77,727 (43.9) | 45.0 |

| Overweight | 45,449 (25.7) | 26.0 |

| Obese | 47,156 (26.7) | 25.5 |

| EC and CC use during the last 3 months of pregnancy | ||

| Non-users | 160,956 (91.0) | 92.0 |

| EC users | 921 (0.5) | 0.5 |

| CC users | 13,697 (7.7) | 6.7 |

| Dual users | 1,308 (0.7) | 0.7 |

BMI- body mass index; EC- electronic cigarette; CC- combustible cigarette.

Sum of categories may not be equal to the total due to missing data.

Table 2.

Correlates of maternal e-cigarette and cigarette use during the last 3 months of pregnancy

| Non-users | EC users | CC users | Dual users | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||||

| Correlates | n (%) | Weighted % | n (%) | Weighted % | n (%) | Weighted % | n (%) | Weighted % | P value |

|

| |||||||||

| In the total sample | 160,956 (91.0) | 92.0 | 921 (0.5) | 0.5 | 13,697 (7.7) | 6.7 | 1,308 (0.7) | 0.7 | |

| Age, years | <0.001 | ||||||||

| ≤19 | 5,499 (89.7) | 89.4 | 64 (1.0) | 1.6 | 488 (8.0) | 7.7 | 77 (1.3) | 1.3 | |

| 20–24 | 21,363 (87.8) | 88.8 | 168 (0.7) | 0.9 | 2,565 (10.5) | 9.3 | 243 (1.0) | 1.0 | |

| 25–29 | 34,560 (89.8) | 90.9 | 179 (0.5) | 0.5 | 3,441 (8.9) | 7.9 | 306 (0.8) | 0.8 | |

| ≥30 | 57,755 (92.9) | 94.1 | 194 (0.3) | 0.4 | 3,920 (6.3) | 5.0 | 330 (0.5) | 0.5 | |

| Education | <0.001 | ||||||||

| High school or lower | 38,357 (83.4) | 85.3 | 314 (0.7) | 0.8 | 6,713 (14.6) | 12.6 | 613 (1.3) | 1.3 | |

| Associates degree or some college | 34,643 (90.4) | 91.0 | 222 (0.6) | 0.7 | 3,172 (8.3) | 7.5 | 305 (0.8) | 0.8 | |

| Bachelors or higher | 45,257 (98.8) | 99.0 | 63 (0.1) | 0.2 | 448 (1.0) | 0.8 | 33 (0.1) | 0.1 | |

| Race | <0.001 | ||||||||

| White | 70,115 (90.5) | 90.9 | 433 (0.6) | 0.7 | 6,261 (8.1) | 7.5 | 707 (0.9) | 0.9 | |

| Black | 22,335 (91.4) | 93.5 | 58 (0.2) | 0.2 | 1,953 (8.0) | 6.1 | 95 (0.4) | 0.2 | |

| American Indian/Alaska Native |

4,466 (79.0) | 83.1 | 29 (0.5) | 0.5 | 1,098 (19.4) | 15.2 | 59 (1.0) | 1.3 | |

| Asian | 9,021 (98.5) | 99.0 | 9 (0.1) | 0.1 | 115 (1.3) | 0.8 | 13 (0.1) | 0.1 | |

| Other non-White | 6,072 (97.3) | 97.9 | 17 (0.3) | 0.2 | 142 (2.3) | 1.7 | 9 (0.1) | 0.1 | |

| Mixed race | 6,126 (87.0) | 88.8 | 53 (0.8) | 0.9 | 792 (11.2) | 9.5 | 70 (1.0) | 0.8 | |

| Marital status | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Unmarried | 59,889 (83.9) | 85.0 | 589 (0.8) | 0.9 | 9,998 (14.0) | 12.7 | 943 (1.3) | 1.4 | |

| Married | 101,001 (95.9) | 96.3 | 328 (0.3) | 0.3 | 3,664 (3.5) | 3.1 | 360 (0.3) | 0.3 | |

|

| |||||||||

| Type of health insurance | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Medicaid | 63,828 (84.4) | 85.4 | 551 (0.7) | 0.8 | 10,265 (13.6) | 12.4 | 1,003 (1.3) | 1.3 | |

| Private insurance | 85,298 (96.5) | 96.7 | 302 (0.3) | 0.4 | 2,594 (2.9) | 2.7 | 226 (0.3) | 0.2 | |

| Self-pay | 4,405 (93.4) | 96.0 | 15 (0.3) | 0.2 | 272 (5.8) | 3.5 | 23 (0.5) | 0.3 | |

| Other | 6,506 (92.4) | 92.5 | 40 (0.6) | 0.6 | 449 (6.4) | 6.0 | 47 (0.7) | 0.8 | |

| Pre-pregnancy hypertension | 0.087 | ||||||||

| Yes | 18,731 (90.7) | 91.6 | 113 (0.5) | 0.6 | 1,665 (8.1) | 7.2 | 135 (0.7) | 0.5 | |

| No | 142,036 (91.0) | 92.0 | 807 (0.5) | 0.5 | 12,001 (7.7) | 6.7 | 1,172 (0.8) | 0.7 | |

| Pre-pregnancy diabetes | 0.253 | ||||||||

| Yes | 11,906 (91.7) | 92.4 | 56 (0.4) | 0.4 | 940 (7.2) | 6.6 | 75 (0.6) | 0.5 | |

| No | 148,863 (90.9) | 92.0 | 864 (0.5) | 0.6 | 12,727 (7.8) | 6.8 | 1,232 (0.8) | 0.7 | |

| Pre-pregnancy BMI | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Underweight | 5538 (84.5) | 86.4 | 65 (1.0) | 1.1 | 833 (12.7) | 10.8 | 114 (1.7) | 1.7 | |

| Normal weight | 71 287 (91.7) | 92.9 | 390 (0.5) | 0.5 | 5481 (7.1) | 6.0 | 569 (0.7) | 0.7 | |

| Overweight | 41 720 (91.8) | 92.5 | 231 (0.5) | 0.6 | 3189 (7.0) | 6.3 | 309 (0.7) | 0.7 | |

| Obese | 42 411 (89.9) | 90.7 | 235 (0.5) | 0.5 | 4194 (8.9) | 8.1 | 316 (0.7) | 0.6 | |

EC - electronic cigarette; CC - combustible cigarette; BMI - body mass index.

Table 3.

Correlates of low gestational weight gain

| Correlates | Low GWG, n(%) | Weighted % | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| In the total sample | 45,253 (25.6) | 22.6 | |

| Age | <0.001 | ||

| 19 and younger | 2,342 (29.0) | 25.6 | |

| 20 – 24 | 8,887 (27.2) | 24.4 | |

| 25 – 29 | 12,946 (25.1) | 21.9 | |

| 30 and older | 21,077 (24.9) | 22.0 | |

| Education | <0.001 | ||

| High school or lower | 18,352 (29.5) | 26.6 | |

| Associates degree or some college | 12,912 (25.1) | 21.7 | |

| Bachelors or higher | 13,630 (22.0) | 19.3 | |

| Race | <0.001 | ||

| White | 24,155 (23.5) | 20.8 | |

| Black | 9,725 (29.3) | 26.7 | |

| American Indian/Alaskan | 2,290 (28.7) | 25.7 | |

| Asian | 3,937 (31.3) | 29.1 | |

| Other non-White | 2,428 (28.8) | 27.1 | |

| Mixed race | 2,358 (22.8) | 22.4 | |

| Marital status | <0.001 | ||

| Unmarried | 19,919 (27.9) | 24.2 | |

| Married | 25,292 (24.0) | 21.5 | |

| Type of health insurance | <0.001 | ||

| Medicaid | 21,845 (28.9) | 25.7 | |

| Private insurance | 20,020 (22.6) | 19.9 | |

| Self-pay | 1,393 (29.5) | 28.8 | |

| Other | 1,680 (23.9) | 21.2 | |

| Pre-pregnancy hypertension | <0.001 | ||

| Yes | 4,609 (22.3) | 19.4 | |

| No | 40,564 (26.0) | 22.9 | |

| Pre-pregnancy diabetes | <0.001 | ||

| Yes | 4,119 (31.7) | 29.2 | |

| No | 41,056 (25.1) | 22.0 | |

| Pre-pregnancy BMI | <0.001 | ||

| Underweight | 3,082 (47.1) | 42.4 | |

| Normal weight | 24,058 (31.0) | 27.1 | |

| Overweight | 7,174 (15.8) | 13.6 | |

| Obese | 10,939 (23.2) | 21.0 | |

GWG - Gestational Weight Gain; BMI - body mass index.

Sum of categories may not be equal to the total due to missing data.

In addition to crude models, multivariable logistic regression models were fitted to examine the associations of e-cigarette and/or cigarette use with risk of low GWG, adjusting for potential confounders (Table 4). The reference category for the exposure variable was “non-users of e-cigarettes or cigarettes”. Odds ratios (ORs) and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated for the other 3 categories including e-cigarette users, cigarette users, and dual users. The significant confounders adjusted in the final model included maternal race, age, marital status, education, health insurance, pre-pregnancy BMI, pre-pregnancy diabetes, and pre-pregnancy hypertension.

Table 4.

Associations between maternal e-cigarette and/or cigarette use during the last 3 months of pregnancy and low gestational weight gain

| Maternal CC/EC use during pregnancy | Low GWG | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| n (%) | Weighted % | Crude OR (95% CI) | Crude OR P-value | Adjusted OR (95% CI)* | Adjusted OR P value | |

|

| ||||||

| Non-users | 40,090 (24.9) | 22.1 | Reference | Reference | ||

| EC users (vs Non-users) | 237 (25.7) | 22.1 | 1.00 (0.79–1.27) | 1.000 | 0.99 (0.78–1.27) | 0.963 |

| CC users (vs Non-users) | 4,499 (32.8) | 28.0 | 1.37 (1.28–1.46) | <0.001 | 1.26 (1.18–1.35) | <0.001 |

| Dual users (vs Non-users) | 427 (32.6) | 26.0 | 1.24 (1.02–1.50) | 0.034 | 1.18 (0.96–1.44) | 0.118 |

| EC users | 237 (25.7) | 22.1 | Reference | Reference | ||

| CC users (vs EC users) | 4,499 (32.8) | 28.0 | 1.37 (1.07–1.76) | 0.014 | 1.27 (0.99–1.64) | 0.065 |

| Dual users (vs EC users) | 427 (32.6) | 26.0 | 1.24 (0.91–1.69) | 0.181 | 1.18 (0.86–1.62) | 0.301 |

| CC users | 4,499 (32.8) | 28.0 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Dual users (vs CC users) | 427 (32.6) | 26.0 | 0.90 (0.74–1.11) | 0.332 | 0.93 (0.75–1.15) | 0.501 |

GWG - Gestational Weight Gain; OR- odds ratio; CI - confidence interval. EC - electronic cigarette; CC - combustible cigarette.

Adjusted for maternal race and ethnicity, age, marital status, education, health insurance, pre-pregnancy body mass index, pre-pregnancy diabetes, and pre-pregnancy hypertension.

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC). Two-sided p-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Sampling weights were used in the statistical analysis (SAS surveyfreq and surveylogistic procedures) to reduce potential selection bias due to non-random sampling, non-coverage, and non-response.14

RESULTS

Sample characteristics

Characteristics of the 176,882 women in the analytic sample are summarized in Table 1. Among them, 84,608 (weighted percentage, 48.2%) were 30 years old or above, 62,085 (37.5%) had bachelors or higher education, 102,955 (70.0%) were White, 33,227 (15.6%) were Black, 105,353 (62.1%) were married, and 88,420 (53.6%) had private insurance. The weighted prevalence of pre-pregnancy hypertension and diabetes was 9.6% (20,644) and 6.9% (12,977), respectively. Before pregnancy, 6,550 (3.5%) women had underweight, 77,727 (45%) had normal weight, 45,449 (26.0%) had overweight, and 47,156 (25.5%) had obesity.

Correlates of e-cigarette and cigarette use during pregnancy

Adolescent mothers (≤19 years) had the highest prevalence of e-cigarette use (64 [weighted percentage, 1.6%]) and dual use (77 [1.3%]) during pregnancy, compared to older mothers (P-value<0.001) (Table 2). Women with bachelors or higher degrees were least likely to use e-cigarettes (63 [0.2%]), cigarettes (448 [0.8%]) or both (33 [0.1%]) (P-value<0.001). Asian women had the lowest prevalence of using e-cigarettes (9 [0.1%]). Women of mixed race had the highest prevalence of e-cigarette use (53 [0.9%]) (P-value<0.001). Married women were less likely than unmarried women to use either e-cigarettes (328 [0.3%] vs 589 [0.9%]) or cigarettes (3,664 [3.1%] vs 9,998 [12.7%]) (P-value<0.001). Women with Medicaid were mostly likely to use e-cigarettes (551 [0.8%]), cigarettes (10,265 [12.4%]), or both (1,003 [1.3%]) (P-value<0.001). Women with underweight were mostly likely (P-value<0.001) to use e-cigarettes (41 [1.1%]), cigarettes (647 [10.8%]), and both (89 [1.7%]), while other mothers had overall similar prevalence of use.

Correlates of low GWG

In the total sample, 45,253 (weighted percentage, 22.6%) of women had low GWG. The risk factors (P-values<0.001) for low GWG included being ≤19 years (2,342 [weighted percentage, 25.6%]), high school or lower education (18,352 [26.6%]), Asian race (3,937 [29.1%]), being unmarried (19,919 [24.2%]), self-pay (1,393 [28.8%]), absence of pre-pregnancy hypertension (40,564 [22.9%]), existence of pre-pregnancy diabetes (4,119 [29.2%]), and underweight (3,082 [42.4%]) (Table 3).

Associations between e-cigarette/cigarette use and low GWG

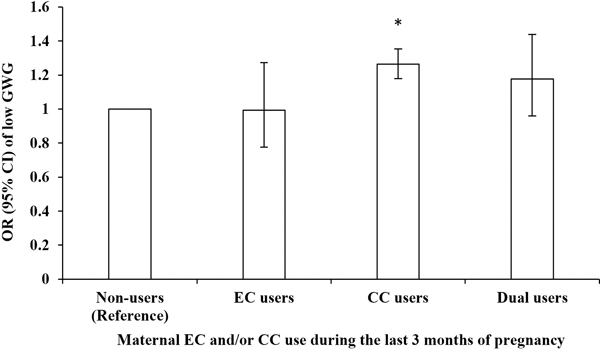

Table 4 shows associations between e-cigarette/cigarette use during the last 3 months of pregnancy and the risk of low GWG among all women. Compared to non-users (40,090 [weighted risk, 22.1%]), cigarette users (4,499 [28.0%]; crude OR, 1.37 [95% CI 1.28–1.46]; P-value<0.001) and dual users (427 [26.0%]; 1.24 [1.02–1.50]; P-value=0.034) had a higher risk of low GWG, but e-cigarette users had a similar risk (237 [22.1%]; 1.00 [0.79–1.27]; P-value=1.000). After adjusting for the confounding effect of maternal race, age, marital status, education, health insurance, pre-pregnancy BMI, and pre-pregnancy diabetes and hypertension, the ORs were moderately attenuated but remained significant for cigarette users (confounder-adjusted OR 1.26 [1.18–1.35]; P-value<0.001), but dual users (1.18 [0.96–1.44]; P-value=0.118) became non-significant (Figure 1). Compared to e-cigarette users, cigarette users (1.27 [0.99–1.64]; P-value=0.065) and dual users (1.18 [0.86–1.62]; P-value=0.301) had a similar risk of low GWG. Compared to cigarette users, dual users (0.93 [0.75–1.15]; P-value=0.501) had a similar risk of low GWG.

Figure 1.

Odds ratio for the associations between maternal EC and/or CC use during the last 3 months of pregnancy and low gestational weight gain

OR - odds ratio; EC - electronic cigarette; CC - combustible cigarette; GWG - gestational weight gain.

* Statistically significant.

DISCUSSIONS

Study Summary

Using U.S. national data from the 2016–2020 PRAMS, we examined the associations of maternal e-cigarette use during pregnancy with low GWG. We found that cigarette users had a high risk of low GWG. However, there was no significant association between e-cigarette use or dual use and low GWG. This novel research suggests that e-cigarette use during late pregnancy may have less impact than cigarette use on GWG.

Correlates of e-cigarette and cigarette use during pregnancy

We observed both similarities and differences between the risk factors for e-cigarette use and cigarette use. Medicaid insurance and low education, both indicators of low socioeconomic status were common among e-cigarette and cigarette users, possibly due to easy access,22 affordability,23 and coping strategy for stress.24, 25 However, users of these two nicotine products differed in age and race. E-cigarette use was most common among adolescent mothers compared to other age groups, and this was consistent with previous findings on the prevalence of e-cigarettes among adolescents.26 E-cigarette use is especially high among adolescents because of novelty seeking,27 e-cigarettes companies’ marketing,28 and peer crowd identification.29 We also found that Native Americans/Native Alaskans were the most frequent users of cigarettes, possibly due to cultural and spiritual factors,30 low cigarette price on the native reservations,31, 32 mental health,33, 34 and low socioeconomic status.35 Mothers of mixed race were the highest users of e-cigarettes among all mothers, but the reasons for this trend are unclear. We recognized our analysis was limited by not addressing systemic factors related to maternal e-cigarette use such as discrimination, health disparities, economic disadvantage, structural and social inequality.36

Association between e-cigarette/cigarette use during pregnancy and low GWG, among all women

In line with the literature,8 we found that cigarette use during late pregnancy was associated with a high risk of low GWG. This association has been tested in both human and animal research to elucidate the possible biological mechanisms. First, it is well-established that smoking cigarettes can lower body weight. Nicotine acts as an appetite suppressant, resulting in decreased food intake. Studies have found that leptin, neuropeptide Y (NPY), and orexins may be involved in nicotine-induced changes in food intake and energy expenditure.37, 38

The most unique contribution of our research to the literature is our finding of a lack of association between e-cigarette use during pregnancy and the risk of low GWG. Although the true reasons for this lack of association are not fully understood, there are several possible explanations. First, some e-cigarettes do not contain nicotine and therefore their use may have limited influence on body weight.39, 40 Animal research suggested that e-cigarette liquid without nicotine had no effect on the body weight gain and food intake of rats,41 which may apply to humans to some extent. Second, even for the e-cigarettes that contain nicotine, they seem to have less impact on body weight than cigarettes. Although there was some decrease in body weight gain and food intake among rats given e-cigarette liquid with nicotine, the effect was not as powerful as in the rats administered with nicotine,41 which might due to decreased bioavailability of nicotine42 and the pH or other chemicals in e-cigarette liquid.43 Third, e-cigarettes do not provide the same satisfaction as cigarettes, therefore, e-cigarette users may have more craving for food (a substitute reward to nicotine).44 Women might have turned to eating more food to gain the satisfaction they previously got from cigarettes because of the overlap of the food and nicotine reward circuitry of the brain.45

It is worthwhile to point out that the dual users in our sample seemed to have intermediate risk of low GWG between e-cigarette users and cigarette users. The association was significant in the crude model, but it was attenuated and became not significant after adjusting for confounders. This interesting finding warrants more research including replication in different cohorts and exploration of the possible reasons.

Strengths and limitations

Our analysis had several strengths. First, we used nationally representative data from PRAMS that covers most live births in the U.S., which could improve generalizability of our findings.14 Second, the large sample size of PRAMS allowed us to examine the individual effects of e-cigarette and cigarettes as well as their dual use. Third, we controlled for key confounders, including sociodemographic and pregnancy characteristics.46 Fourth, the large total sample size could still provide enough statistical power even though we found that the prevalence of e-cigarette use during late pregnancy was low.

However, this study also had a number of important limitations. First, the self-reported data was subject to information bias. E-cigarette and/or cigarette use were likely to be under-reported, partially due to social stigmatization. Second, we did not examine the frequency of e-cigarette and cigarette use to retain the statistical power and sample sizes to examine their exclusive or dual use and the risk of low GWG. Third, we did not control for the potential influence of the use of other tobacco and nicotine products, illicit drugs, alcohol, caffeine, and some medications (e.g., insulin47 and anti-vomiting drugs48) on GWG. Fourth, we could not assess the potential influence of e-cigarette use during early or mid-pregnancy due to lack of this information in PRAMS. Fifth, detailed information on e-cigarette products (e.g., brand, device type, flavoring, and nicotine concentration) was not available in PRAMS.

Conclusions and Implications

We concluded that the effect of maternal use of nicotine products during pregnancy on the risk of low GWG varied by product types. Cigarette users during pregnancy had a high risk of low GWG. However, e-cigarette use during pregnancy did not appear to be a risk factor for low GWG. If replicated in other studies, our novel research can contribute to the scientific knowledge on effects of e-cigarette and/or cigarette use on maternal health and inform clinical practice and public policies.

Synopsis:

Unlike combustible cigarette use, e-cigarette use during pregnancy does not appear to be a risk factor for low GWG.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse and the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Center for Tobacco Products (CTP) through grant no. R21 DA053638 (to XW). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the FDA. The funders had no role in data analysis or writing the manuscript or the decision to submit it for publication.

We are grateful to the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS) Working Group and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for providing the original PRAMS data set and technical support.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST:

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.Teshome AA, Li Q, Garoma W, Chen X, Wu M, Zhang Y, et al. : Gestational diabetes mellitus, pre-pregnancy body mass index and gestational weight gain predicts fetal growth and neonatal outcomes. Clin Nutr ESPEN 2021;42: 307–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu X, Wang H, Yang L, Zhao M, Magnussen CG, Xi B: Associations Between Gestational Weight Gain and Adverse Birth Outcomes: A Population-Based Retrospective Cohort Study of 9 Million Mother-Infant Pairs. Front Nutr 2022;9: 811217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rasmussen KM, Yaktine AL. Weight gain during pregnancy: reexamining the guidelines. Washington (DC): The National Academies Press. 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yu ZM, Van Blyderveen S, Schmidt L, Lu C, Vanstone M, Biringer A, et al. : Predictors of Gestational Weight Gain Examined As a Continuous Outcome: A Prospective Analysis. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2021;30(7): 1006–1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Azagba S, Manzione L, Shan L, King J: Trends in smoking during pregnancy by socioeconomic characteristics in the United States, 2010–2017. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020;20(1): 52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kondracki AJ: Prevalence and patterns of cigarette smoking before and during early and late pregnancy according to maternal characteristics: the first national data based on the 2003 birth certificate revision, United States, 2016. Reprod Health 2019;16(1): 142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cnattingius S: The epidemiology of smoking during pregnancy: smoking prevalence, maternal characteristics, and pregnancy outcomes. Nicotine Tob Res 2004;6 Suppl 2: S125–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Amyx M, Zeitlin J, Hermann M, Castetbon K, Blondel B, Le Ray C: Maternal characteristics associated with gestational weight gain in France: a population-based, nationally representative study. BMJ Open 2021;11(7): e049497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kong G, Kuguru KE, Krishnan-Sarin S: Gender Differences in U.S. Adolescent E-Cigarette Use. Curr Addict Rep 2017;4(4): 422–430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/e-cigarettes/about-e-cigarettes.html. Published 2022. Accessed December 31 2022.

- 11.Wagner NJ, Camerota M, Propper C: Prevalence and Perceptions of Electronic Cigarette Use during Pregnancy. Matern Child Health J 2017;21(8): 1655–1661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Regan AK, Bombard JM, O’Hegarty MM, Smith RA, Tong VT: Adverse Birth Outcomes Associated With Prepregnancy and Prenatal Electronic Cigarette Use. Obstet Gynecol 2021;138(1): 85–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang RJ, Bhadriraju S, Glantz SA: E-Cigarette Use and Adult Cigarette Smoking Cessation: A Meta-Analysis. Am J Public Health 2021;111(2): 230–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shulman HB, D’Angelo DV, Harrison L, Smith RA, Warner L: The pregnancy risk assessment monitoring system (PRAMS): overview of design and methodology. American journal of public health 2018;108(10): 1305–1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roustaei Z, Raisanen S, Gissler M, Heinonen S: Associations between maternal age and socioeconomic status with smoking during the second and third trimesters of pregnancy: a register-based study of 932 671 women in Finland from 2000 to 2015. BMJ Open 2020;10(8): e034839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deputy NP, Sharma AJ, Kim SY, Hinkle SN: Prevalence and characteristics associated with gestational weight gain adequacy. Obstet Gynecol 2015;125(4): 773–781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lindstrom M: Social capital, economic conditions, marital status and daily smoking: a population-based study. Public Health 2010;124(2): 71–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Naavaal S, Malarcher A, Xu X, Zhang L, Babb S: Variations in Cigarette Smoking and Quit Attempts by Health Insurance Among US Adults in 41 States and 2 Jurisdictions, 2014. Public Health Rep 2018;133(2): 191–199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bowman TS, Gaziano JM, Buring JE, Sesso HD: A prospective study of cigarette smoking and risk of incident hypertension in women. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007;50(21): 2085–2092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Willi C, Bodenmann P, Ghali WA, Faris PD, Cornuz J: Active smoking and the risk of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2007;298(22): 2654–2664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abdulmalik MA, Ayoub JJ, Mahmoud A, collaborators M, Nasreddine L, Naja F: Pre-pregnancy BMI, gestational weight gain and birth outcomes in Lebanon and Qatar: Results of the MINA cohort. PLoS One 2019;14(7): e0219248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dalglish E, McLaughlin D, Dobson A, Gartner C: Cigarette availability and price in low and high socioeconomic areas. Aust N Z J Public Health 2013;37(4): 371–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mills SD, Golden SD, Henriksen L, Kong AY, Queen TL, Ribisl KM: Neighbourhood disparities in the price of the cheapest cigarettes in the USA. J Epidemiol Community Health 2019;73(9): 894–896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hobkirk AL, Krebs NM, Muscat JE: Income as a moderator of psychological stress and nicotine dependence among adult smokers. Addict Behav 2018;84: 215–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fidler JA, West R: Self-perceived smoking motives and their correlates in a general population sample. Nicotine Tob Res 2009;11(10): 1182–1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vallone DM, Bennett M, Xiao H, Pitzer L, Hair EC: Prevalence and correlates of JUUL use among a national sample of youth and young adults. Tobacco control 2019;28(6): 603–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Patrick ME, Miech RA, Carlier C, O’Malley PM, Johnston LD, Schulenberg JE: Self-reported reasons for vaping among 8th, 10th, and 12th graders in the US: Nationally-representative results. Drug and alcohol dependence 2016;165: 275–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mantey DS, Cooper MR, Clendennen SL, Pasch KE, Perry CL: E-cigarette marketing exposure is associated with e-cigarette use among US youth. Journal of Adolescent Health 2016;58(6): 686–690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stalgaitis CA, Djakaria M, Jordan JW: The Vaping Teenager: understanding the psychographics and interests of adolescent vape users to inform health communication campaigns. Tobacco use insights 2020;13: 1179173X20945695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kunitz SJ: Historical Influences on Contemporary Tobacco Use by Northern Plains and Southwestern American Indians. Am J Public Health 2016;106(2): 246–255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Golden SD, Kong AY, Ribisl KM: Racial and Ethnic Differences in What Smokers Report Paying for Their Cigarettes. Nicotine Tob Res 2016;18(7): 1649–1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.DeLong H, Chriqui J, Leider J, Chaloupka FJ: Common state mechanisms regulating tribal tobacco taxation and sales, the USA, 2015. Tob Control 2016;25(Suppl 1): i32–i37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Duran B, Sanders M, Skipper B, Waitzkin H, Malcoe LH, Paine S, et al. : Prevalence and correlates of mental disorders among Native American women in primary care. Am J Public Health 2004;94(1): 71–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hodge FS, Fredericks L, Kipnis P: Patient and smoking patterns in northern California American Indian Clinics. Urban and rural contrasts. Cancer 1996;78(7 Suppl): 1623–1628. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Garrett BE, Martell BN, Caraballo RS, King BA: Socioeconomic Differences in Cigarette Smoking Among Sociodemographic Groups. Prev Chronic Dis 2019;16: E74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baah FO, Teitelman AM, Riegel B: Marginalization: Conceptualizing patient vulnerabilities in the framework of social determinants of health-An integrative review. Nurs Inq 2019;26(1): e12268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Filozof C, Fernandez Pinilla M, Fernández‐Cruz A: Smoking cessation and weight gain. Obesity reviews 2004;5(2): 95–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li MD, Parker SL, Kane JK: Regulation of feeding-associated peptides and receptors by nicotine. Mol Neurobiol 2000;22(1–3): 143–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Romberg AR, Miller Lo EJ, Cuccia AF, Willett JG, Xiao H, Hair EC, et al. : Patterns of nicotine concentrations in electronic cigarettes sold in the United States, 2013–2018. Drug Alcohol Depend 2019;203: 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marynak KL, Gammon DG, Rogers T, Coats EM, Singh T, King BA: Sales of Nicotine-Containing Electronic Cigarette Products: United States, 2015. Am J Public Health 2017;107(5): 702–705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Golli NE, Dkhili H, Dallagi Y, Rahali D, Lasram M, Bini-Dhouib I, et al. : Comparison between electronic cigarette refill liquid and nicotine on metabolic parameters in rats. Life sciences 2016;146: 131–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Farsalinos KE, Spyrou A, Tsimopoulou K, Stefopoulos C, Romagna G, Voudris V: Nicotine absorption from electronic cigarette use: comparison between first and new-generation devices. Sci Rep 2014;4: 4133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.DeVito EE, Krishnan-Sarin S: E-cigarettes: Impact of E-Liquid Components and Device Characteristics on Nicotine Exposure. Curr Neuropharmacol 2018;16(4): 438–459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bowker K, Orton S, Cooper S, Naughton F, Whitemore R, Lewis S, et al. : Views on and experiences of electronic cigarettes: a qualitative study of women who are pregnant or have recently given birth. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2018;18(1): 233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stojakovic A, Espinosa EP, Farhad OT, Lutfy K: Effects of nicotine on homeostatic and hedonic components of food intake. J Endocrinol 2017;235(1): R13–R31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lau EY, Liu J, Archer E, McDonald SM, Liu J: Maternal weight gain in pregnancy and risk of obesity among offspring: a systematic review. Journal of obesity 2014;2014: 524939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Makimattila S, Nikkila K, Yki-Jarvinen H: Causes of weight gain during insulin therapy with and without metformin in patients with Type II diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia 1999;42(4): 406–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sullivan CA, Johnson CA, Roach H, Martin RW, Stewart DK, Morrison JC: A pilot study of intravenous ondansetron for hyperemesis gravidarum. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1996;174(5): 1565–1568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]