Abstract

We report on a study of 158 methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) clinical isolates obtained from 1990 to 1996 in 18 different hospitals in Poland. All isolates were recovered from infection and carriage sites of patients, carriage sites of health care personnel, and hospital environment samples. Fifty-seven MRSA strains described here were studied previously and these were divided into two different clusters according to the degree of heterogeneity of methicillin resistance expression. The aim of this study was to extend the correlation between the two clusters and identify the clonal identities among all isolates by a combination of different methodologies: (i) analysis of mecA polymorphs and Tn554 insertion patterns and (ii) determination of pulsed-field gel electrophoresis patterns of chromosomal SmaI digests. Ninety-seven of 158 strains showed a heterogeneous expression of resistance to methicillin. Among these, 75 (77.3%) were ClaI-mecA type I, ClaI-Tn554 type NH (NH, no homology with transposon Tn554), and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) pattern A (I::NH::A); 10 isolates were III::B::M (10.3%); and the remaining clones included a few or single isolates. The isolates with homogeneous expression of resistance to methicillin (n = 61) were predominantly ClaI-mecA type III (49 of 61 [80.3%]) but had great variability in their ClaI-Tn554 and PFGE patterns. This study confirmed the existence of two main clusters of MRSA in Poland.

Staphylococcus aureus is recognized as one of the most important bacterial pathogens seriously contributing to the problem of hospital infections all over the world. Since the appearance in 1961 of intrinsically methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) strains (11), MRSA strains quickly spread, and at present in some countries they can constitute up to 80% of all S. aureus isolates in hospitals (31). A survey of MRSA isolates in Poland showed that the average prevalence of MRSA in hospitals varies from 2.3% (10) to 59.9% (19).

A unique feature of methicillin resistance is its heterogeneous phenotypic expression. In a given culture there are many subpopulations of cells for which methicillin MICs are different. The number of cells belonging to each subpopulation and the range of methicillin MICs for the cells are stable for a particular strain and appear to be strain specific. Tomasz and coworkers (26) defined four different classes of methicillin resistance on the basis of the strains’ resistance phenotypes. The majority of cells in cultures of MRSA strains belonging to classes 1 and 2 have only low levels of resistance to methicillin, but a small proportion of cells are highly resistant to this antibiotic; in MRSA strains of classes 3 and 4, most cells in the culture are highly resistant to methicillin.

Epidemiological typing of MRSA strains isolated in Poland by using both the methicillin resistance phenotype and DNA-based techniques (randomly amplified polymorphic DNA [RAPD] analysis, pulsed-field gel electrophoresis [PFGE], and other techniques) has defined two clusters of MRSA strains. One cluster grouped strains with the methicillin resistance phenotype of classes 1 and 2 (heterogeneously resistant to methicillin [HeMRSA]) and the other includes strains with the methicillin resistance phenotype of classes 3 and 4 (homogeneously resistant to methicillin [HoMRSA]) (13, 27–29).

The aim of the present study was to confirm and extend the previously described correlation between the two clonally related groups of MRSA with a larger collection of isolates (158 isolates) and identify the clonal identities among the isolates by a combination of methodologies not used earlier for Polish isolates. The methodology used was based on the analysis of ClaI-digested genomic DNA hybridization patterns obtained with mecA gene and Tn554 transposon DNA probes and analysis of SmaI-restricted genomic DNAs patterns by PFGE. ClaI-mecA polymorphisms reflect sequence variability in the vicinity of the mecA gene. ClaI-Tn554 insertion patterns result from the number of copies of the Tn554 transposon in the staphylococcal chromosome and the sequence variation in their vicinity. Probing of ClaI-digested genomic DNA with labelled mecA and Tn554 DNA fragments with the complement of PFGE has successfully been applied to epidemiological analyses of MRSA isolates from hospitals in different countries (2, 4, 6–8, 20, 21, 23) and also for tracking of the international spread of some MRSA clones (1, 14, 18, 22).

(Part of this study was presented at the 8th European Congress of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, Lausanne, Switzerland, May 1997 [abstr. P438].)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Clinical isolates.

One hundred fifty-eight MRSA isolates were collected between 1990 and 1996 at nine hospitals in Warsaw (113 isolates; 71.5%) and nine hospitals located in seven other towns in different parts of Poland (45 isolates; 28.5%). Information about the origins of the strains is presented in Tables 1 and 2, and the locations of the hospitals are shown in Fig. 1. Isolates were recovered from patients with infections (79.1%), colonized patients (8.9%) and health care personnel (9.5%), and the hospital environment (3.2%). Strains which caused infections were mostly isolated from postoperative or burn wounds (39.9%), blood (15.2%), purulent eye material (9.5%), skin lesions (6.3%), bronchial exudates (6.3%), ear exudates (5.7%), and sputa (4.4%).

TABLE 1.

Clinical data for and clonal analysis of isolates in the HeMRSA cluster

| Clonal type (ClaI-mecA::ClaI-Tn554::SmaI) | No. of isolates | Reference | Centera | Isolation yr | Antibiogramb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I::NH::A | 75 | WAW1 | 1994 | t r | |

| 29 | WAW1 | 1994 | |||

| GDK1 | 1994 | ||||

| 27 | LOD1 | 1991 | T X | ||

| WAW1 | 1993 | t | |||

| 29 | WAW1 | 1993 | |||

| WAW1 | 1995 | t | |||

| 27 | WAW2 | 1991 | |||

| 28 | WAW2 | 1992 | t | ||

| 13 | WAW2 | 1996 | |||

| WAW3 | 1995 | t e | |||

| WAW4 | 1994 | ||||

| WAW5 | 1994 | ||||

| WAW6 | 1992 | ||||

| XXI::NH::A | 1 | WAW3 | 1995 | ||

| II:NH::A | 1 | WAW1 | 1993 | T | |

| I::NH::J | 2 | WAW3 | 1995 | ||

| II::NH::I | 4 | SUW | 1994 | ||

| WAW1 | 1995 | t | |||

| III::B::C | 1 | SIE | 1995 | TEGChCS | |

| III::B::M | 10 | SIE | 1995 | TEGChCS | |

| III::ϕϕ::N | 1 | SIE | 1995 | TEGCh | |

| III::χχ::M | 1 | SIE | 1995 | TEGChCS | |

| XX::g′::O | 1 | SIE | 1995 | TEGS |

Hospital abbreviations: GDK1, Municipal Hospital in Gdansk; LOD1, Medical University Hospital in Lodz; SUW, Municipal Hospital in Suwalki; SIE, Municipal Hospital in Siemianowice Slaskie; WAW1, Bielany Hospital in Warsaw; WAW2, University Children’s Hospital in Warsaw; WAW3, University Hospital No. 2 in Warsaw; WAW4, Children Hospital Kondratowicza in Warsaw; WAW5, Czerniakowska Hospital in Warsaw; WAW6, Children Memorial Hospital in Warsaw.

Explanation of resistance patterns: C, clindamycin; Ch, chloramphenicol; E, erythromycin; F, fusidic acid; G, gentamicin; R, rifampin; S, spectinomycin; T, tetracycline; X, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. Capital letters indicate that all isolates of a given clone are resistant, lowercase letters indicate that only a fraction of the isolates of the clone are resistant, and no letter indicates that all isolates of the clone are sensitive.

TABLE 2.

Clinical data for and clonal analysis of isolates in the HoMRSA cluster

| Clonal type (ClaI-mecA::ClaI-Tn554::SmaI) | No. of isolates | Reference(s) | Centera | Isolation yr | Antibiogramb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I::E::H | 3 | SIE | 1995 | T E G R C S | |

| WAW4 | 1994 | E G c r R S | |||

| I::ςς::K | 1 | 13 | WAW2 | 1996 | T E G Ch S |

| III::ρρ::B | 13 | 27 | WAW9 | 1991 | T E G S |

| 27 | WAW2 | 1992 | T E G x s | ||

| 13 | WAW2 | 1996 | T E G | ||

| 29 | WAW8 | 1992 | E G R S | ||

| 29 | WRL | 1992 | E G ch s | ||

| III:ρρ::C | 4 | WAW4 | 1994 | E G s | |

| WAW5 | 1994 | E G S | |||

| III::ρρ::D | 1 | 27 | WAW2 | 1990 | T E G S |

| III::κ::C | 7 | GDK1 | 1994 | E G S | |

| GDK1 | 1994 | E G X S | |||

| 28, 29 | WAW2 | 1992 | T E G X S | ||

| WAW4 | 1994 | E G S | |||

| 29 | WAW8 | 1992 | E G S | ||

| III::κ::D | 3 | 13 | WAW2 | 1996 | T E S |

| 27 | WAW7 | 1990 | T E S x | ||

| III::B::B | 1 | 27 | WAW7 | 1990 | T E S |

| III::B::C | 1 | WAW5 | 1994 | E G S | |

| III::B::E | 4 | LOM | 1994 | E G C S | |

| III::B::L | 1 | 29 | KRK | 1992 | E G S |

| III::χχ::C | 4 | SIE | 1995 | T e G ch | |

| WRL | 1994 | E G S | |||

| III::χχ::D | 2 | 29 | WAW6 | 1992 | E G Ch S |

| 29 | WRL | 1992 | E G S | ||

| III::E::F | 1 | LOD2 | 1994 | E G C F X | |

| III::E::G | 1 | 29 | KRK | 1992 | E G Ch S |

| III::ɛɛ::B | 2 | 27 | WAW2 | 1992 | T E G X S |

| 27 | WAW2 | 1992 | E G X S | ||

| III::M::C | 1 | LOM | 1994 | E G S | |

| III::M::E | 1 | LOM | 1994 | E G C S | |

| III::AA::G | 1 | 29 | WAW6 | 1992 | E G S |

| III::ϕϕ::C | 1 | LOM | 1994 | E G S | |

| VI::κ::C | 1 | 29 | GDK2 | 1992 | E G Ch S |

| VI::κ::D | 1 | 27 | WAW2 | 1992 | T E X S |

| XX::κ::D | 1 | 29 | GDK2 | 1992 | E Ch X S |

| XX::g′::O | 1 | SIE | 1995 | T E G S | |

| III′::ρρ::B | 2 | 29 | WAW2 | 1992 | E G |

| 13 | WAW2 | 1996 | T E G | ||

| III"::ρρ::P | 2 | SIE | 1995 | T E G S |

Hospital abbreviations: GDK1, Municipal Hospital in Gdansk; GDK2, University Hospital in Gdansk; LOD2, Polish Mother Memorial Hospital in Lodz; LOM, Municipal Hospital in Lomza; SIE, Municipal Hospital in Siemianowice Slaskie; WRL, University Hospital in Wroclaw; KRK, University Hospital in Krakow; WAW2, University Children’s Hospital in Warsaw; WAW4, Children Hospital Kondratowicza in Warsaw; WAW5, Czerniakowska Hospital in Warsaw; WAW6, Children Memorial Hospital in Warsaw; WAW7, University Hospital No. 1 in Warsaw; WAW8, Institute of Tuberculosis Hospital in Warsaw; WAW9, Wolska Street Hospital in Warsaw.

Explanation of resistance patterns: C, clindamycin; Ch, chloramphenicol; E, erythromycin; F, fusidic acid; G, gentamicin; R, rifampin; S, spectinomycin; T, tetracycline; X, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. Capital letters indicate that all isolates of a given clone are resistant, lowercase letters indicate that only a fraction of isolates of the clone are resistant, and no letter indicates that all isolates of the clone are sensitive.

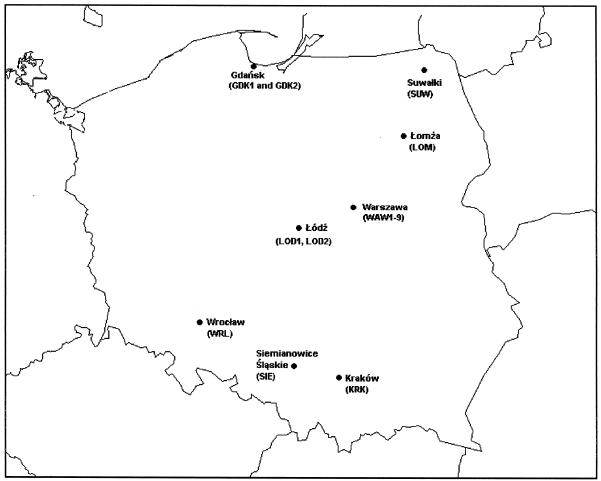

FIG. 1.

Locations of hospitals in which the isolates were collected.

The largest numbers of MRSA isolates were collected from four hospitals; Bielanski Hospital in Warsaw (WAW1), 39 isolates; University Children’s Hospital in Warsaw (WAW2), 30 isolates, University Hospital No. 2 in Warsaw (WAW3), 22 isolates; and the Municipal Hospital in Siemianowice (SIE), 20 isolates. WAW1 is a large teaching hospital, and all MRSA isolates were recovered from its two pediatric wards. WAW2 is a medium-size teaching center (300 beds) which accepts severely debilitated patients from all over the country; MRSA isolates were collected from different wards (intensive care unit, surgery, newborn pathology, hematology, endocrinology, nephrology). WAW3 is a small (160-bed) gynecological-obstetric teaching hospital, and MRSA strains were isolated from patients hospitalized in the neonatal ward. SIE is a regional hospital with a specialized burn unit (60 beds) to which patients with severe burns from the whole country are referred. All MRSA isolates from SIE were recovered from patients on the burn unit.

Fifty-seven of the 158 MRSA isolates were previously typed by a variety of phenotypic methods (including antibiotic susceptibility testing), PFGE, and other DNA-based methods different from the ones used in the present study (13, 27–29).

Susceptibility testing.

All the isolates were tested with a panel of nine antibiotics (erythromycin, gentamicin, tetracycline, chloramphenicol, ciprofloxacin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, rifampin, fusidic acid, and vancomycin) by the disc diffusion method according to the guidelines of the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (17). For interpretation of fusidic acid susceptibility test results, French guidelines were adopted (3).

Resistance to methicillin was evaluated by a rapid agar screening method with tryptic soy agar (Difco, Oxoid, Hampshire, United Kingdom) plates with 25 mg of methicillin (SmithKline Beecham, London, United Kingdom) per liter (5). Strains were classified as HeMRSA if growth of countable colonies was observed after 40 h of incubation at 37°C and as HoMRSA when confluent or semiconfluent growth was observed, as described previously (13, 16, 27–29). Resistance to spectinomycin (Sigma Chemical Company, St. Louis, Mo.) was evaluated on tryptic soy agar plates supplemented with 500 mg of spectinomycin per liter (12).

SmaI PFGE patterns.

Chromosomal grade genomic DNA preparation and SmaI (New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass.) digestion were carried out as described previously (4). PFGE was run in an LKB-Pharmacia 2015 Gene Navigator apparatus (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden) with the following running conditions (21): run time, 22 h; pulses, 5 s for 5 h, 10 s for 6 h, 30 s for 6 h, and 60 s for 5 h; buffer, 0.5× TBE (Tris-borate-EDTA).

ClaI-mecA and ClaI-Tn554 types.

Chromosomal grade DNA preparations were restricted with BspI106 (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.), a ClaI isoschizomer, and were separated by conventional gel electrophoresis as described previously (4). The 1.2-kb PstI-XbaI DNA fragment excised from the pMF13 plasmid (15) was used as a mecA probe in hybridization studies. The 5.5-kb EcoRV fragment of the Tn554 transposon cloned in a pBluescript II vector (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) was used as a Tn554 probe (12). The DNA fragments were extracted from agarose gels with the USBioclean kit (United States Biochemical, Cleveland, Ohio) according to the manufacturer’s protocol and labelled with the ECL Random Prime Labelling System II (RPN3040; Amersham, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom) following the manufacturer’s recommendations. Transfer of DNA onto Hybond N+ membranes (Amersham) was performed with the use of a vacuum blotter (VacuGene XL; Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden) according to the manufacturer’s instructions for conventional gels and following a previously described protocol for PFGE (4). After blotting, the membrane was dried and DNA was fixed with UV light (254 nm). Hybridization, washing, detection, and probe stripping were performed with the ECL system (Amersham) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations.

Interpretation of results obtained by molecular typing techniques.

PFGE patterns were assigned according to established criteria (24): patterns with up to six band differences were considered subtypes (number code) of PFGE major patterns (capital letter), with all patterns being compared to the major pattern (pattern A). ClaI-mecA and ClaI-Tn554 hybridization patterns were designated by roman numerals (for ClaI-mecA) and letters (for ClaI-Tn554) and were interpreted as being different when there was a single DNA band size difference between patterns (12). When patterns had not been described previously, new roman numerals and letters were assigned. If patterns were very similar to the previously described ones, single or double prime symbols were used.

RESULTS

Methicillin resistance expression.

The phenotypic methicillin resistance expression classes (heterogeneous or homogeneous) of 57 previously analyzed isolates (13, 27–29) were confirmed in the course of this study. The remaining 101 isolates were tested by the same methodology. Altogether, 97 of 158 isolates (61.4%) were HeMRSA and 61 (38.6%) were HoMRSA.

Patterns of resistance to antibiotics.

Detailed results of antibiotic resistance testing (together with typing results, year of collection, and data on the origins of the isolates) are presented in Tables 1 and 2. Of all the antibiotics tested, the ones to which resistance was most frequently observed were erythromycin (48.7%), gentamicin (43.7%), tetracycline (40.5%), and spectinomycin (36.7%). The percentages of isolates resistant to chloramphenicol, ciprofloxacin, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole were lower: 12.7, 12.7, and 8.9%, respectively. The antibiotics that were most active against this group of MRSA isolates were rifampin (2.5% of resistant isolates), fusidic acid (0.6% resistant isolates), and vancomycin (all 158 isolates were sensitive).

Considerable differences in the proportions of resistant isolates between the groups of HeMRSA and HoMRSA isolates were observed. HeMRSA isolates were generally found to be less resistant. The greatest differences concerned erythromycin (HeMRSA, 16.5% resistant isolates; HoMRSA, 100%), gentamicin (HeMRSA, 15.5%; HoMRSA, 88.5%), and spectinomycin (HeMRSA, 13.4%; HoMRSA, 73.8%). It was also found that within the HeMRSA cluster, a group of 14 isolates from the burn units of SIE could be distinguished. All of these isolates were characterized by identical resistance profiles and were (in contrast to most of the HeMRSA isolates) resistant to tetracycline, erythromycin, gentamicin, chloramphenicol, ciprofloxacin, and spectinomycin.

SmaI PFGE patterns.

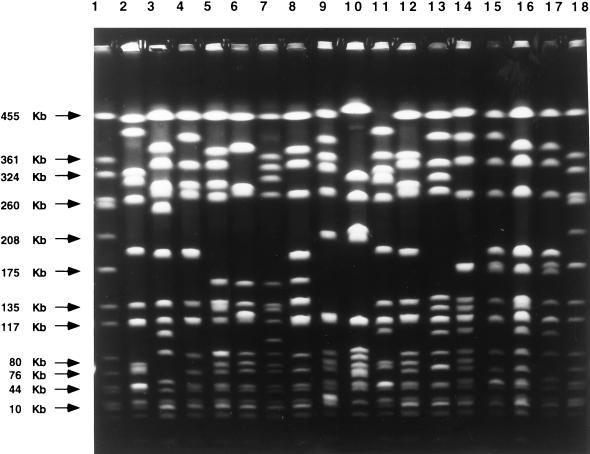

Analysis of SmaI PFGE patterns was based on comparison of the banding patterns obtained by PFGE of chromosomal DNA digested with the SmaI enzyme. The previously tested 57 isolates were retyped by this method, and the patterns obtained were in agreement with the earlier results (13, 27–29). Among all MRSA isolates in the collection, 57 different patterns which belonged to 16 major PFGE types were identified. The most frequent types were A (48.7% of all isolates), C (12.7%), B (11.4%), M (7.0%), and D (5.1%). The remaining types were represented by a few or single isolates.

Among the isolates in the HeMRSA group, seven major PFGE patterns were identified, with two types being predominant: A, 77 of the 97 isolates (79.4%), and M, 11 isolates (11.3%). The most frequent PFGE types among HoMRSA isolates were C (19 of 61 isolates; 31.1%) and B (18 isolates; 29.5%). Examples of the PFGE patterns are shown in Fig. 2.

FIG. 2.

Major PFGE patterns found among the 158 MRSA clinical isolates recovered from Poland. All 16 major PFGE patterns (patterns A through O) obtained after SmaI restriction of chromosomal DNAs are shown. Samples are as follows: lanes 1 and 18, reference strain NCTC 8235 (band molecular sizes are indicated on the left); lane 2, pattern A; lane 3, pattern B; lane 4, pattern C; lane 5, pattern D; lane 6, pattern E; lane 7, pattern F; lane 8, pattern G; lane 9, pattern H; lane 10, pattern I; lane 11, pattern J; lane 12, pattern K; lane 13, pattern L; lane 14, pattern M; lane 15, pattern N; lane 16, pattern O; lane 17, pattern P.

ClaI-mecA types.

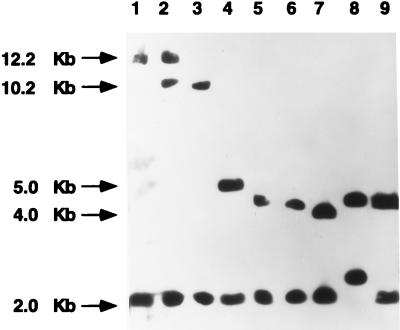

Results of hybridizations of the mecA probe with ClaI-digested genomic DNA from the analyzed isolates revealed the presence of eight polymorphisms in the mecA vicinity (Fig. 3). We detected the presence of the already described types I, II, III, and VI (12), as well as novel types XX, XXI, III′ and III". The most frequent ClaI-mecA types were type I (81 isolates; 51.3%), which was more prevalent among HeMRSA isolates (79.3% of HeMRSA isolates and 6.6% of HoMRSA isolates) and type III (62 isolates; 39.2%), which was most common among HoMRSA isolates (80.3% of HoMRSA isolates and 13.4% of HeMRSA isolates). The remaining ClaI-mecA types were represented by a few or single isolates.

FIG. 3.

ClaI-mecA types found among the 158 MRSA clinical isolates recovered from Poland. All eight ClaI-mecA types found in this study are shown: patterns I, II, VI, and III were described previously (12), and patterns XX, XXI, III′, and III" were first described in this study. Relevant molecular sizes are indicated on the left of the pictures. Samples are as follows: lane 1, type I; lane 2, type XXI; lane 3, type II; lane 4, type VI; lane 5, type III; lane 6, type III′; lane 7, type III"; lane 8, type XX; lane 9, type III (control strain RN7164) (12).

ClaI-Tn554 insertion patterns.

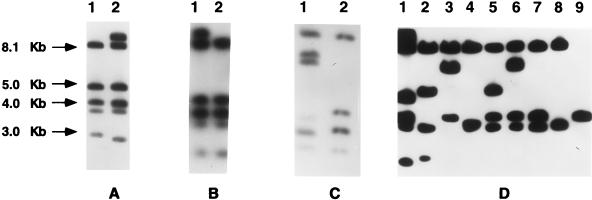

It was found that 83 isolates (52.5%), all of which were HeMRSA, did not carry transposon Tn554 (pattern NH [no homology]). Among the remaining 75 Tn554-positive isolates, 11 different hybridization patterns were identified, including 4 previously described patterns (B, E, M, and AA) (12) and seven patterns reported in this work for the first time (κ, g′, ɛɛ, χχ, ϕϕ, ρρ, and ςς). Of these, the most prevalent was novel pattern ρρ, which was present in 22 HoMRSA isolates (29.3% of Tn554-containing isolates). Pattern B was found in 18 isolates (24.0%; 11 HeMRSA and 7 HoMRSA isolates). Pattern κ was identified exclusively in 13 HoMRSA isolates. The other patterns were represented by a few or single isolates. Altogether, there were 5 ClaI-Tn554 hybridization types among the HeMRSA isolates (including the NH pattern) and 11 among the HoMRSA isolates. The ClaI-Tn554 patterns are shown in Fig. 4.

FIG. 4.

ClaI-Tn554 insertion patterns found among the 158 MRSA clinical isolates recovered from Poland. All ClaI-Tn554 insertion patterns found in this study are shown. Relevant molecular sizes are indicated on the left. (A) Lane 1, pattern B; lane 2, pattern g′. (B) Lane 1, pattern M; lane 2, pattern B. (C) Lane 1, pattern ɛɛ; lane 2, pattern B. (D) lane 1, pattern g′; lane 2, pattern AA; lane 3, pattern ϕϕ; lane 4, pattern E; lane 5, pattern ςς; lane 6, pattern ρρ; lane 7, pattern κ; lane 8, pattern E; lane 9, pattern χχ.

Clonal analysis: the heterogeneous cluster (HeMRSA).

Table 1 provides the results for all the clonal types defined in the HeMRSA cluster. The majority of HeMRSA isolates (75 isolates) were associated with ClaI-mecA type I, ClaI-Tn554 type NH, and PFGE pattern A (abbreviated I::NH::A), 4 isolates were type II::NH::I, and 10 isolates (all from the burn unit of the Siemianowice Hospital) were type III::B::M. The remaining clonal types were represented by single isolates.

Clonal analysis: the homogeneous cluster (HoMRSA).

Table 2 provides the results for the clonal types identified in the HoMRSA cluster. The HoMRSA isolates displayed six ClaI-mecA types, with ClaI-mecA type III being predominant (80.3%). Isolates of this type were very variable in terms of their ClaI-Tn554 patterns (nine types) and PFGE patterns (seven types). The remaining isolates represented several minor clonal types.

DISCUSSION

Previous epidemiological studies of MRSA in Poland were performed with the use of phenotypic typing methods (antibiotic resistance profile typing, phage typing, typing on the basis of type of growth on medium containing crystal violet) and DNA-based methods (PFGE, RAPD analysis) (27, 29) and led to the conclusion that the MRSA strains circulating in Poland formed two distinct groups in terms of strain relatedness. One of the most characteristic features distinguishing strains of these groups was their phenotypic expression of methicillin resistance. All the strains belonging to one cluster were more heterogeneously resistant to methicillin (resistance to methicillin expression classes 1 and 2 [26]), while all the strains belonging to the other cluster were more homogeneously resistant to methicillin (classes 3 and 4). The study reported here, carried out with a larger and more representative collection of isolates from the whole country and with the use of additional typing techniques (ClaI-mecA and ClaI-Tn554 typing), in general confirmed that finding.

The set of typing techniques used in this study, based on Southern hybridization of ClaI-digested DNAs with mecA and Tn554 probes combined with PFGE of SmaI-digested genomic DNAs, have been used for epidemiological analyses of MRSA isolates from many countries (4, 6–8, 18). This methodology was applied for the first time to an analysis of Polish MRSA isolates, and many novel ClaI-mecA and ClaI-Tn554 hybridization patterns were obtained, including some unusual ones (Tables 1 and 2).

The molecular typing techniques used in this study have proved to be useful for the epidemiological study of a large collection of Polish MRSA isolates. A typing technique that is based on the variability of two specific markers (mecA gene and Tn554 transposon) and that has moderate discriminatory power defined a few main clonal types that almost perfectly correlated with the previously defined clusters associated with specific phenotypes of methicillin resistance. The PFGE analysis, a method with high discriminatory power, distinguished a variety of clones within each of the general ClaI-mecA::ClaI-Tn554 types. This allowed a more precise analysis of the epidemiological situation in particular hospitals. A great advantage of this typing system is that the results between different laboratories may easily be compared, which is in contrast to the situation for RAPD typing, which is (due to its low specificity of primer annealing) very sensitive to even small changes in PCR conditions, and so interlaboratory comparisons of the patterns generated by the RAPD typing technique are extremely difficult (30).

The susceptibility testing performed in this study confirmed previous findings that in Poland only HoMRSA isolates have the general multidrug resistance characteristic of MRSA. HeMRSA isolates were found to be generally less resistant than HoMRSA isolates, especially with respect to erythromycin, spectinomycin, and gentamicin resistance. A strong correlation between the presence of Tn554 and resistance to erythromycin was observed; all HoMRSA isolates contained Tn554 and were resistant to erythromycin. On the other hand, most HeMRSA isolates were lacking the transposon (85.6%) and were susceptible to erythromycin (83.5%). Two isolates were found to be free of Tn554 DNA but were resistant to erythromycin, which could be explained by the presence of another resistance gene(s) (for instance, ermC or msrA).

HeMRSA isolates collected in the burn unit of SIE were found to be resistant to more antibiotics than other Polish HeMRSA strains and were also genetically distinct from other HeMRSA strains according to the results of epidemiological typing (discussed below). They were resistant to erythromycin, gentamicin, ciprofloxacin, chloramphenicol, and spectinomycin, which may be due to the use of large quantities of antibiotics in the treatment of patients with burns.

Molecular typing has also confirmed the considerable differences between the HeMRSA and HoMRSA clusters of isolates. As shown in Table 1, HeMRSA isolates form a quite coherent group of related isolates with a high prevalence (77.3%) of the clonal type I::NH::A. In addition, 2.1% of HeMRSA isolates consisted of clones which are related to clonal type I::NH::A (II::NH::A and XXI::NH::A) and shared the same genomic background (PFGE pattern A).

Typing data concerning the HoMRSA cluster indicate that this group was much more genetically diverse than HeMRSA (26 clonal types of HoMRSA versus 10 clonal types of HeMRSA). However, 49 (80.3%) of the HoMRSA isolates were ClaI-mecA type III, and a further 6 (9.8%) were represented by related types XX, III′, and III" that differ from type III only in small band-size shifts. The ClaI-Tn554 types present in HoMRSA isolates were very heterogeneous (11 different types). HoMRSA also presented many different PFGE patterns: 11 different types were defined within this cluster.

Within the entire collection of 158 MRSA isolates, 91 isolates originated from four hospitals, and for these hospitals the following three different situations were observed: (i) the coexistence of clonal types belonging to both clusters (HeMRSA and HoMRSA) in WAW2 in Warsaw; (ii) the dominance of the HeMRSA clone (clone I::NH::A) in the pediatric wards of WAW1 and WAW3, both in Warsaw, in 92.3 and 86.4% of the isolates, respectively; and (iii) the dominance of the unusual HeMRSA clone, clone III::B::M, in the burn unit of SIE among 50% of the isolates. The MRSA isolates recovered from patients in SIE constitute a particular group: most of the isolates were characterized as HeMRSA and were ClaI-mecA type III, and 50% of the isolates were the dominant clone III::B::M. Moreover, these isolates were characterized by specific antibiotypes and PFGE patterns. These data suggest that in this hospital there is a completely new family of clonal types.

The differences in clonal composition between the HeMRSA and HoMRSA clusters of strains indicate that these groups probably evolved from different MRSA strains (single strains or small numbers of strains) that varied originally in the mode of methicillin resistance expression. It was suggested that HoMRSA strains might have been imported from Germany (26a). This hypothesis was based on the fact that the majority of Polish HoMRSA strains were typeable with a local German experimental phage, A994, selected specifically for the typing of German MRSA isolates (32). No HeMRSA isolates were susceptible to this phage (29). The relative genetic diversity of HoMRSA isolates may be a result of multiple introductions of HoMRSA into Polish hospitals or of genetic instability related to the presence of certain phages, transposons, or plasmids integrated into the staphylococcal chromosome (29). Several lines of evidence may support the hypothesis that the HeMRSA isolates form a coherent group that is very different from the HoMRSA cluster. The molecular typing performed in this study has shown that HeMRSA isolates are closely related, so they could have recently diverged from a common ancestor, for example, by the horizontal transfer of the mecA gene to a local methicillin-susceptible S. aureus strain. The existence of the HeMRSA phenotype is in agreement with the observation that introduction of the mecA gene into methicillin-susceptible S. aureus produces a strain which is heterogeneously resistant to methicillin (25). Another clue supporting the idea of the recent emergence of the Polish HeMRSA cluster is the general susceptibility of HeMRSA strains to antibiotics, because there might not have been enough time for the selection of multidrug-resistant clones of HeMRSA. However, the detection of multidrug-resistant HeMRSA strains in Polish hospitals was reported recently (16).

The data presented here revealed that certain epidemic MRSA strains were continuously present in hospitals analyzed over long periods of time (endemic clones). For example, HoMRSA of ClaI-mecA type III and ClaI-Tn554 type ρρ were observed in isolates collected in 1990 and 1996. Similarly, HeMRSA clonal type I::NH::A isolates, which are widespread in Warsaw, were present in the same hospital (WAW2) over a period of at least 5 years. When we consider the geographic origins of the isolates, it is remarkable that among the MRSA strains isolated in Warsaw there is a larger proportion of HeMRSA (69.0%) than the proportion of HeMRSA among the isolates from other locations (42.2%). This observation is in concordance with previous results and can be explained by worse MRSA detection sensitivity in smaller microbiological laboratories outside Warsaw (9). Most of the differences between MRSA from Warsaw and other towns is a simple consequence of the different percentages of HeMRSA and HoMRSA isolates included in these collections. This involves the presence of ClaI-mecA type I and the absence of Tn554 in most isolates from Warsaw. However, some differences between HoMRSA strains from Warsaw and those from other locations were revealed. These differences refer to Tn554 types: among isolates from Warsaw type ρρ prevails, whereas the most frequent type found among isolates from outside Warsaw was type B.

The collection of Polish MRSA isolates analyzed in the present study consists of four large groups of isolates from three hospitals in Warsaw and one hospital in Siemianowice and several small groups of isolates from different hospitals in different towns. The numbers of isolates collected in particular parts of Poland did not reflect the real numbers of MRSA isolates recovered there, so the proportions of the identified clonal types in the collection are probably not representative for the whole country. The results obtained, however, allowed us to define a variety of clonal types present among a large collection of Polish MRSA isolates as well as to confirm the presence of two main clusters of strains with particular phenotypes of methicillin resistance circulating in Poland.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by KBN (Polish Scientific Committee; grant 4 P05D 006 09) and by the CEM/NET initiative: project 31 from IBET (Oeiras, Portugal), contract PRAXIS 2/2.1/BIO/1154/95 (Lisbon, Portugal), and a grant from Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian awarded to H. de Lencastre. T. Leski was supported by a 3-month grant from Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian awarded to the CEM/NET Fellowship Program. D. Oliveira was supported by grants PRODEP from FCT/UNL (Monte da Caparica, Portugal) and BIC 3243 from PRAXIS XXI (Lisbon, Portugal). M. Aires de Sousa was supported by grant BTL 6260 from PRAXIS XXI (Lisbon, Portugal).

REFERENCES

- 1.Aires de Sousa M, Santos Sanches I, Ferro M L, Vaz M J, Saraiva Z, Tendeiro T, Serra J, de Lencastre H. Intercontinental spread of a multidrug resistant methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) clone. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:2590–2596. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.9.2590-2596.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aires de Sousa M, Santos Sanches I, van Belkum A, van Leeuven W, Verbrugh H, de Lencastre H. Characterization of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates from Portuguese hospitals by multiple genotyping methods. Microb Drug Resist. 1996;2:331–340. doi: 10.1089/mdr.1996.2.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Courvalin P, Soussy C J. Report of the Comite de l’Antibiogramme de la Societé Française de Microbiologie. Clin Microbiol Infect. 1996;2:S11–S25. doi: 10.1007/BF01974543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Lencastre H, Couto I, Santos I, Melo-Cristino J, Torres-Pereira A, Tomasz A. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus disease in a Portuguese hospital: characterization of clonal types by a combination of DNA typing methods. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1994;13:64–73. doi: 10.1007/BF02026129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Lencastre H, Figueiredo A M S, Urban C, Rahal J, Tomasz A. Multiple mechanisms of methicillin resistance and improved methods for detection in clinical isolates of Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991;35:632–639. doi: 10.1128/aac.35.4.632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Lencastre H, Severina E P, Milch H, Konkoly-Thege M, Tomasz A. Wide geographic distribution of a unique methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) clone in Hungarian hospitals. Clin Microbiol Infect. 1997;3:289–296. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.1997.tb00616.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Lencastre H, Severina E P, Roberts R B, Kreiswirth B N, Tomasz A the BARG Initiative Pilot Study Group. Testing the efficacy of a molecular surveillance network: methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium (VREF) genotypes in six hospitals in the metropolitan New York City area. Microb Drug Resist. 1996;2:343–351. doi: 10.1089/mdr.1996.2.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dominguez M A, de Lencastre H, Linares J, Tomasz A. Spread and maintenance of a dominant methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) clone during an outbreak of MRSA disease in a Spanish hospital. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:2081–2087. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.9.2081-2087.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hryniewicz W, Trzcinski K. The current situation and perspectives of standardisation in susceptibility testing in Poland. Antiinfect Drugs Chemother. 1994;13:35–40. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hryniewicz W, Zareba T, Jeljaszewicz J. Patterns of antibiotic resistance in bacterial strains isolated in Poland. APUA Newsl. 1993;11:1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jevons M P. “Celebenin“-resistant staphylococci. Br Med J. 1961;i:124–125. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kreiswirth B, Kornblum J, Arbeit R D, Eisner W, Maslow J N, McGeer A, Low D E, Novick R P. Evidence for a clonal origin of methicillin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Science. 1993;259:227–230. doi: 10.1126/science.8093647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leski T A, Gniadkowski M, Trzcinski K, Hryniewicz W. Comparison of genetic characteristics of MRSA strains present in the Warsaw hospital in 1992 and 1996. Zentbl Bakteriol. 1998;287:363–373. doi: 10.1016/s0934-8840(98)80172-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mato R, Santos Sanches I, Venditti M, Platt D J, Brown A, de Lencastre H. Spread of the multiresistant Iberian clone of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) to Italy and Scotland. Microb Drug Resist. 1998;4:107–112. doi: 10.1089/mdr.1998.4.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matthews P R, Tomasz A. Insertional inactivation of the mecA gene in a transposon mutant of a methicillin-resistant clinical isolate of Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990;34:1777–1779. doi: 10.1128/aac.34.9.1777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murcham S, Trzcinski K, Skoczynska A, van Leeuven W, van Belkum A, Pietuszko S, Gadomski T, Hryniewicz W. Spread of old and new clones of epidemic methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Poland. Clin Microbiol Infect. 1998;4:481–490. [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Performance standards for antimicrobial disk susceptibility test. Approved standard. NCCLS document M2-A5. Wayne, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oliveira D, Santos Sanches I, Tamayo M, Ribeiro G, Mato R, Costa D, de Lencastre H. Virtually all MRSA infections in the largest Portuguese hospital are caused by two internationally spread multiresistant strains: the “Iberian” and the “Brazilian” clones of MRSA. Clin Microbiol Infect. 1998;4:373–384. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.1998.tb00081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18a.Oliveira D, Leski T, Sanches I, Hryniewicz W, de Lencastre H. Program and abstracts of the 8th European Congress of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, Lausanne, Switzerland. 1997. Two clusters of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Poland, abstr. P438. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Piechowicz L, Namysl E, Galinski J. Wystípowanie metycylinoopornych gronkowców w Polsce i ich charakterystyka. Med Dosw Mikrobiol. 1993;45:273–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Santos Sanches I, Aires de Sousa M, Cleto L, Baeta de Campos M, de Lencastre H. Tracing the origin of an outbreak of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in a Portuguese hospital by molecular fingerprinting methods. Microb Drug Resist. 1997;2:319–328. doi: 10.1089/mdr.1996.2.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Santos Sanches I, Aires de Sousa M, Sobral L, Calheiros I, Felicio L, Pedra I, de Lencastre H. Multidrug-resistant Iberian epidemic clone of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus endemic in a hospital in northern Portugal. Microb Drug Resist. 1995;1:299–306. doi: 10.1089/mdr.1995.1.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Santos Sanches I, Ramirez M, Troni H, Abecassis H, Padua M, Tomasz A, de Lencastre H. Evidence for the geographic spread of a methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clone between Portugal and Spain. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:1243–1246. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.5.1243-1246.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Teixeira L A, Resende C A, Ormonde L R, Rosenbaum R, Figueiredo A M S, de Lencastre H, Tomasz A. Geographic spread of epidemic multiresistant Staphylococcus aureus clone in Brazil. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2400–2404. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.9.2400-2404.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tenover F C, Arbeit R D, Goering V R, Mickelsen P A, Murray B E, Pershing D H, Swaminathan B. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial strain typing. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2233–2239. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.9.2233-2239.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tomasz A. Auxiliary genes assisting in the expression of methicillin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. In: Novick R P, editor. Molecular biology of staphylococci. New York, N.Y: VCH Publishers, Inc.; 1990. pp. 565–584. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tomasz A, Nachman S, Leaf H. Stable classes of phenotypic expression in methicillin-resistant clinical isolates of staphylococci. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991;35:124–129. doi: 10.1128/aac.35.1.124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26a.Trzcinski, K. Unpublished data.

- 27.Trzcinski K, Hryniewicz W, Claus H, Witte W. Characterization of two different clusters of clonally related methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains by conventional and molecular typing. J Hosp Infect. 1994;28:113–126. doi: 10.1016/0195-6701(94)90138-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Trzcinski K, Hryniewicz W, Kluytmans J, van Leeuven W, Sijmons M, Dulny G, Verbrugh H, van Belkum A. Simultaneous persistence of methicillin-resistant and methicillin susceptible clones of Staphylococcus aureus in a neonatal ward of a Warsaw Hospital. J Hosp Infect. 1997;36:291–303. doi: 10.1016/s0195-6701(97)90056-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Trzcinski K, van Leeuven W, van Belkum A, Grzesiowski P, Kluytmans J, Sijmons M, Verbrugh H, Witte W, Hryniewicz W. Two clones of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Poland. Clin Microbiol Infect. 1997;3:198–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.1997.tb00598.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Van Belkum A, Kluytmans J, van Leeuven W, Quint W, Peters E, Fluit A, Vandenbroucke-Grauls C, van den Brule A, Koeleman H. Multicenter evaluation of arbitrarily primed PCR for typing of Staphylococcus aureus strains. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:1537–1547. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.6.1537-1547.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wenzel R P, Nettleman M D, Jones R N, Pfaller M A. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: implications for the 1990s and effective control measures. Am J Med. 1991;91:221S–227S. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(91)90372-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Witte W, van Dip N, Dunnhaupt K. Methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in German Democratic Republic—incidence and strain characteristics. J Hyg Epidemiol Microbiol Immunol. 1986;30:185–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]