Abstract

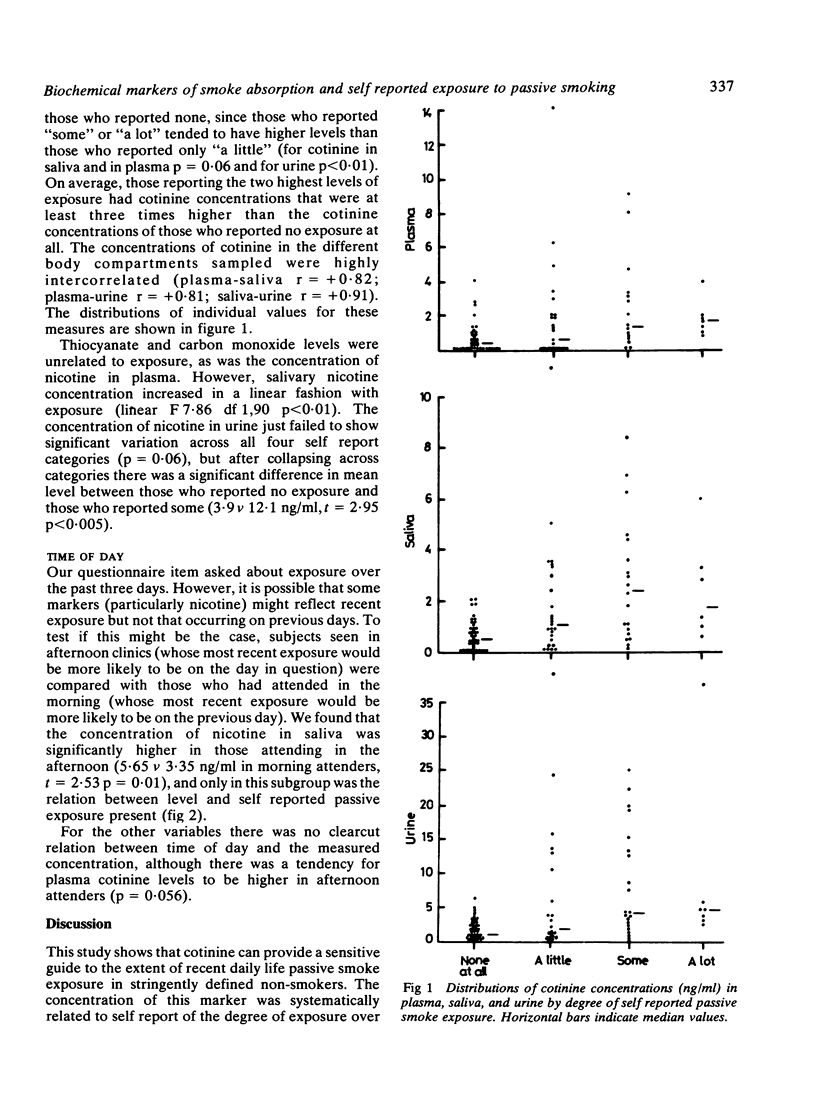

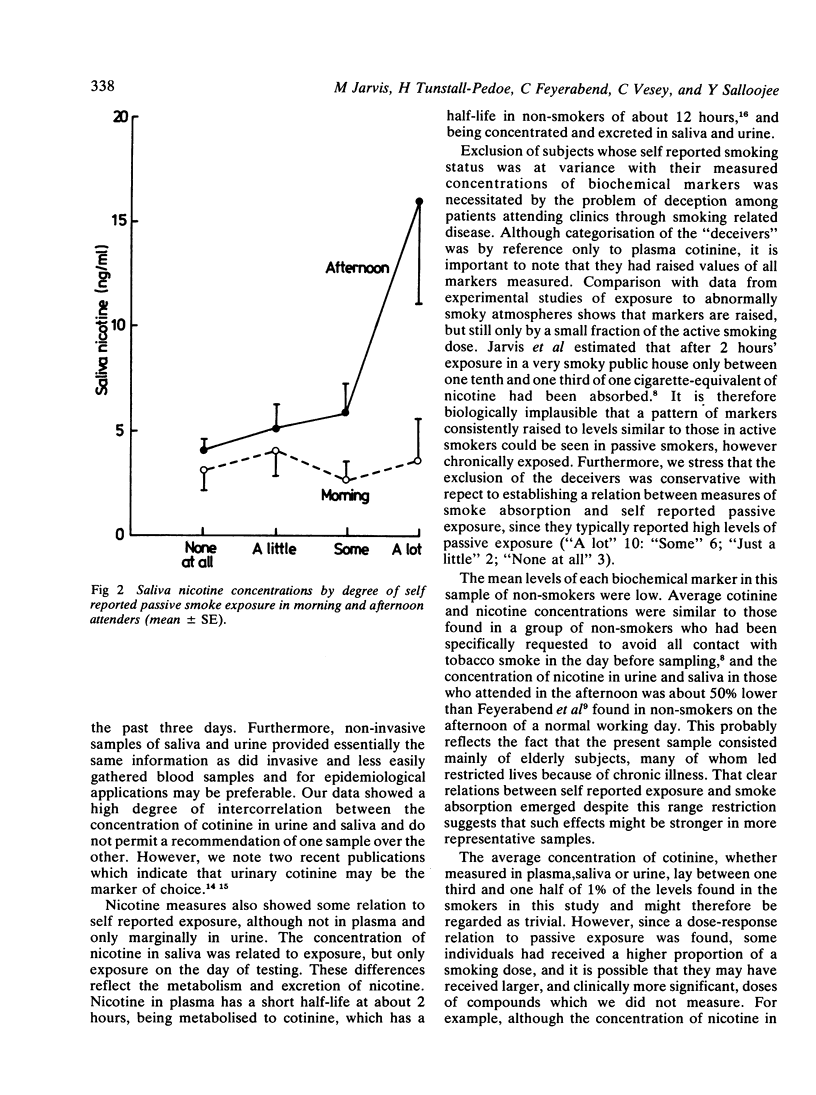

One hundred non-smoking patients attending hospital outpatient clinics reported their degree of passive exposure to tobacco smoke over the preceding three days and provided samples of blood, expired air, saliva, and urine. Although the absolute levels were low, the concentration of cotinine in all body compartments surveyed was systematically related to self reported exposure. Salivary nicotine concentration also showed a linear increase with degree of reported exposure, although this measure was sensitive only to exposure on the day of testing. Measures of carbon monoxide, thiocyanate, and plasma nicotine concentrations were unrelated to exposure. The data indicate that cotinine provides a valid marker of the dose received from passive smoke exposure. The non-invasive samples of urine and saliva are particularly suited to epidemiological investigations. Detailed questionnaire items may also give valuable information.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Feyerabend C., Higenbottam T., Russell M. A. Nicotine concentrations in urine and saliva of smokers and non-smokers. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1982 Apr 3;284(6321):1002–1004. doi: 10.1136/bmj.284.6321.1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feyerabend C., Russell M. A. Assay of nicotine in biological materials: sources of contamination and their elimination. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1980 Mar;32(3):178–181. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1980.tb12885.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feyerabend C., Russell M. A. Rapid gas-liquid chromatographic determination of cotinine in biological fluids. Analyst. 1980 Oct;105(1255):998–1001. doi: 10.1039/an9800500998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman G. D., Petitti D. B., Bawol R. D. Prevalence and correlates of passive smoking. Am J Public Health. 1983 Apr;73(4):401–405. doi: 10.2105/ajph.73.4.401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg R. A., Haley N. J., Etzel R. A., Loda F. A. Measuring the exposure of infants to tobacco smoke. Nicotine and cotinine in urine and saliva. N Engl J Med. 1984 Apr 26;310(17):1075–1078. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198404263101703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirayama T. Non-smoking wives of heavy smokers have a higher risk of lung cancer: a study from Japan. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1981 Jan 17;282(6259):183–185. doi: 10.1136/bmj.282.6259.183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James P. B. Fat embolism in multiple sclerosis. Lancet. 1982 Jun 12;1(8285):1356–1356. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(82)92418-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis M. J., Russell M. A., Feyerabend C. Absorption of nicotine and carbon monoxide from passive smoking under natural conditions of exposure. Thorax. 1983 Nov;38(11):829–833. doi: 10.1136/thx.38.11.829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis M. J., Russell M. A., Saloojee Y. Expired air carbon monoxide: a simple breath test of tobacco smoke intake. Br Med J. 1980 Aug 16;281(6238):484–485. doi: 10.1136/bmj.281.6238.484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyerematen G. A., Damiano M. D., Dvorchik B. H., Vesell E. S. Smoking-induced changes in nicotine disposition: application of a new HPLC assay for nicotine and its metabolites. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1982 Dec;32(6):769–780. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1982.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee P. N. Passive smoking. Food Chem Toxicol. 1982 Apr;20(2):223–229. doi: 10.1016/s0278-6915(82)80254-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell M. A., Cole P. V., Brown E. Absorption by non-smokers of carbon monoxide from room air polluted by tobacco smoke. Lancet. 1973 Mar 17;1(7803):576–579. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(73)90718-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saloojee Y., Vesey C. J., Cole P. V., Russell M. A. Carboxyhaemoglobin and plasma thiocyanate: complementary indicators of smoking behaviour? Thorax. 1982 Jul;37(7):521–525. doi: 10.1136/thx.37.7.521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trichopoulos D., Kalandidi A., Sparros L., MacMahon B. Lung cancer and passive smoking. Int J Cancer. 1981 Jan 15;27(1):1–4. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910270102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wald N. J., Boreham J., Bailey A., Ritchie C., Haddow J. E., Knight G. Urinary cotinine as marker of breathing other people's tobacco smoke. Lancet. 1984 Jan 28;1(8370):230–231. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)92156-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White J. R., Froeb H. F. Small-airways dysfunction in nonsmokers chronically exposed to tobacco smoke. N Engl J Med. 1980 Mar 27;302(13):720–723. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198003273021304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]