Abstract

The beating of motile cilia requires the coordinated action of diverse machineries that include not only the axonemal dynein arms, but also the central apparatus, the radial spokes, and the microtubule inner proteins. These machines exhibit complex radial and proximodistal patterns in mature axonemes, but little is known about the interplay between them during motile ciliogenesis. Here, we describe and quantify the relative rates of axonemal deployment for these diverse cilia beating machineries during the final stages of differentiation of Xenopus epidermal multiciliated cells.

Introduction:

The coordinated beating of motile cilia on multiciliated cells (MCCs) drives directional fluid flow that is essential for the development and homeostasis of diverse organ systems, notably the vertebrate airways, reproductive tract, and central nervous system (Brooks and Wallingford, 2014; Mahjoub et al., 2022). Beating of these cells’ cilia relies on several protein machines that are radially organized throughout the axoneme (Fig. 1A, left)(Dutcher, 2020). For example, microtubule inner proteins (MIPs) project inside the outer doublet microtubules, provide structural stability, and likely regulate axonemal dynein function (Ichikawa and Bui, 2018). The axonemal dyneins, in turn, reside outside these doublet microtubules, and include both the outer and inner dynein arms (ODAs, IDAs)(King, 2018; Yamamoto et al., 2021). In the center of the axoneme are the central pair microtubules and these are surrounded by the central apparatus (Loreng and Smith, 2017). Finally, radial spokes project from the doublets toward the central pair (Zhu et al., 2017). Each of these systems are required for normal ciliary beating, but because each system is more frequently studied in isolation, the interplay between them remains ill defined.

Figure 1:

A) Schematics of a representative vertebrate MCC axoneme (Lin et al., 2014), with relevant components of ciliary beating machineries indicated. ODA (outer dynein arm), IDA (inner dynein arm), CA (central apparatus), N-DRC (nexin-dynein regulatory complex), RS (radial spoke), MIP (microtubule inner protein), ODA-DC (ODA docking complex) B-E) The indicated ODAs, IDAs, radial spokes, and MIPs do not extend to the distal limit of the axoneme, as marked by membrane RFP. F-H) The indicated ODA, radial spoke, and MIP are excluded from the Spef1-enriched distal domain. I) A single frame from a time-lapse movie of GFP-Ift38 and RFP-Spef1. J) A projection of 60 frames of time-lapse data reveals absence of Ift38 from the Spef1-enrched distal domain at st. 27. Scale bars = 10 μm, scale bars for insets = 0.5 μm

In addition to the radial patterning, motile axonemes display a complex proximal to distal (PD) patterning. Such patterning is most obviously displayed by the presence of ODAs and IDAs in highly order repeating units (Fig. 1A, right), but there are more complex patterns as well (Dutcher, 2020). For example, the PD patterning of specific ODA and IDA sub-types has been well defined by structural studies in Chlamydomonas (Bui et al., 2012; Piperno and Ramanis, 1991; Yagi et al., 2009) and by immunostaining of ODA/IDA heavy chains in vertebrates (Dougherty et al., 2016; Fliegauf et al., 2005; Oltean et al., 2018). Motile cilia, including those on vertebrate MCCs, also display specialized distal tip domains that are distinct in structure and composition from the rest of the axoneme (Soares et al., 2019).

One of many unanswered questions relates to how these radial and proximodistal patterns are deployed into nascent growing axonemes during the development of MCCs. For example, a small subset of proximally-restricted IDAs are known to be deployed only very late during cilia regeneration in Chlamydomonas (Piperno and Ramanis, 1991) and immunostaining has identified certain distinct heavy chains associated with these motors (Yagi et al., 2009). A recent study has also explored the initial deployment of certain ODA and IDA heavy chains during ciliary growth in human MCCs (Oltean et al., 2018).

But little or nothing is known about the timing of deployment of the full spectrum of ODA/IDA subtypes or of how ODA/IDA deployment relates to that of distinct machineries like the MIPs, radial spokes, or central apparatus. Likewise one paper has carefully defined central apparatus assembly during flagellogenesis in Chlamydomonas (Lechtreck et al., 2013), but no comparable study has been made in vertebrate MCCs.

These questions are important, because recent studies have highlighted the functional interplay between the central apparatus and deployment of ODA/IDAs and radial spokes (Konjikusic et al., 2022) and because disruption of cytosolic assembly factors for axonemal dyneins in human motile ciliopathy elicits proximodistally-restricted defects in ODA/IDA deployment (Lee et al., 2020; Omran et al., 2008; Tarkar et al., 2013; Yamaguchi et al., 2018). As a starting point for future experimental studies, we present here a quantitative description of the relative rates of deployment of MIPs, radial spokes, the central apparatus, ODAs, and IDAs in the growing axonemes of developing MCCs in the Xenopus epidermis.

Results:

Cilia beating machines and IFT are excluded from the distal axoneme of Xenopus MCCs

The Xenopus epidermis provides a tractable vertebrate model for imaging MCC development (Brooks and Wallingford, 2015; Walentek and Quigley, 2017; Werner and Mitchell, 2012). As a starting point, we co-expressed GFP fusions to ciliary beating machines together with membrane-RFP (memRFP) to mark the axoneme. Using full-length axonemes at St. 27, we first examined representative markers of the ODAs and IDAs (Dnai2, Dnali1)(King, 2018), the radial spokes (Rsph1)(Anderegg et al., 2019), and MIPs (Cfap52)(Gui et al., 2021; Khalifa et al., 2020). As shown in Fig. 1B–E, each of these reporters (green) displayed an obvious lack of signal in the distalmost ~10% of the axoneme when compared to the membrane marker (magenta).

In organisms from Tetrahymena to humans, motile cilia display specialized distal tip regions (Soares et al., 2019), and in Xenopus epidermal MCCs this region is reliably marked by a strong enrichment of Spef1 (aka Clamp)(Gray et al., 2009). This microtubule bundling protein is also present in the central apparatus but at much lower intensity, and its distally enriched domain is readily identifiable (Konjikusic et al., 2022). To ask if the distal region of MCC axonemes lacking ciliary beating machinery corresponds to the Spef1-enriched domain, we co-expressed RFP-Spef1 with GFP fusions to other ciliary proteins. At st. 27, we found that the ODA subunit Dnai2, the radial spoke protein Nme5, and the MIP Cfap52 each displayed the same pattern, with the distal GFP signal terminating at the proximal limit of the enriched RFP-Spef1 signal (Fig. 1F–H).

Dynein arms, radial spokes, and other cargoes are actively transported within axonemes by the intraflagellar transport (IFT) system (Lechtreck, 2015), so we next asked how the movement of IFT trains related to the Spef1-enriched domain. We used high speed time-lapse imaging to track the movement of the IFT protein, Ift38/Cluap1 (Fig. 1I) (Lee et al., 2014), and by merging several frames of such movies, we clearly observed that the distal limit of IFT movement matched tightly to the proximal limit of the Spef1-enriched domain (Fig. 1J).

These data lead us to several interesting, if preliminary, conclusions: First, the data suggest that four major elements of ciliary beating machinery display similar distal extents in later stage axonemes, terminating at the proximal end of the Spef1+ domain. Second, our data suggest that, conversely, the Spef1-enriched region at later stages axonemes may represent a specialized distal domain of Xenopus MCCs that lacks components of the ciliary beating machinery as well as the IFT machinery that transports them. TEM of this region will be of great interest. Third, consistent with the findings in Chlamydomonas that IFT is the key mechanism for transport of dynein arms and radial spokes within cilia (Lechtreck, 2015), the distal extent of IFT we observed is well-matched to that of the ciliary beating machinery. Finally, the absence of IFT from the distal Spef1-enriched domain is curious and begs the question of how proteins are transported to this region. One possibility is that, consistent with the IFT-independent -based transport of Eb1 in Chlamydomonas is independent of IFT (Harris et al., 2015), that Eb1 and other proteins in the distal tip of Xenopus MCC cilia (Konjikusic et al., 2022) are likewise enriched by a diffuse-and-capture mechanism.

The specialized distal axoneme forms early during axoneme growth and is not coupled to deployment of the ciliary beating machinery

Xenopus epidermal MCCs arise via radial intercalation at the early tailbud stage and immediately begin to grow cilia, and over the next several hours, immature cilia can be readily observed (Drysdale and Elinson, 1992; Stubbs et al., 2006). To ask how the Spef1-enriched distal domain is assembled during ciliary growth, we examined GFP-Spef1 and memRFP during cilia growth (St. 21–27). At the earliest stages examined when cilia were quite short, Spef1 evenly labeled axonemes along their length, but by st. 22, a small region of distal enrichment was visible (Fig. 2A, B, I). This distal enrichment grew as axonemes grew, finally reaching its final size by st. 27 (Fig. 2C, I).

Figure 2:

A-C) GFP-Spef1 distal enrichment in growing axonemes at stages indicated. D-E) Eb1-GFP is enriched at the distal tip of growing axonemes at stages indicated. F) Image labelled Eb1-GFP and RFP-Spef1 G-H) The deployment of the radial spoke protein Nme5 does not reach to the Spef1 enriched domain at st. 25 but does so by st. 27. I) Plot of axoneme length versus Spef1 length, Nme5 length and the length of the gap separating them; each point represents a single axoneme. Scale bars = 10 μm, scale bars for insets = 0.5 μm

The distal tips of motile cilia display specializations that differ widely, not just between species but also between cell types (Soares et al., 2019; Dentler and Lecluyse, 1982; Portman et al., 1987; LeCluyse and Dentler, 1984). Because the ultrastructure of the specialized distal axoneme of Xenopus epidermal MCCs has not been described, we sought to better understand how the assembly of the Spef1-enriched domain relates to the axonemal microtubules. To this end, we imaged the localization of the microtubule plus-tip protein Eb1-GFP during ciliary growth. At st. 21, when Spef1 was still diffusely present throughout the short axoneme, Eb1-GFP was already tightly localized a very small domain at the distal tip (Fig. 2D). At st. 23, as the Spef1 enriched domain is beginning form, the tip enrichment of Eb1 remined strong, but was accompanied by an additional, more proximal focus of enrichment (Fig. 2E). By St. 27, this second focus became more obvious and clearly marked the proximal end of the well-defined Spef1+ domain (Fig. 2F). Again, TEM of this region will be of great interest, but one parsimonious explanation of the Eb1 pattern is that the Spef1+ domain marks a region of extended microtubule singlets similar to that observed in the distal tips of diverse axonemes (Soares et al., 2019).

Finally, to understand how the assembly of the Spef1-enriched domain relates to axonemal deployment of ciliary beating machinery, we co-expressed RFP-Spef1 and the radial spoke protein, GFP-Nme5 (Anderegg et al., 2019) and imaged growing cilia. Interestingly, in shorter growing cilia we observed a clear gap between the distal limit of Nme5 and the proximal limit of Spef1 enrichment (Fig. 2G, inset at right). As cilia approach their final length, this gap shrank and eventually disappeared so that Nme5 abuts the Spef1-enriched domain in full-length cilia (Fig. 2H, I). These data suggest that as the axoneme grows, distal tip assembly and deployment of the beating machinery are uncoupled, with the distal Spef1-enriched domain assembling from the growing tip of the axoneme and the relatively delayed deployment of radial spokes proceeding from the ciliary base before finally terminating at the proximal end of the Spef1-enriched region.

Deployment of microtubule inner proteins and radial spokes is tightly coupled to axoneme elongation, while the central apparatus lags behind

We next sought to determine the timing of deployment of ciliary beating machines into the axoneme during ciliary growth. While methods for physically immobilizing Xenopus MCC cilia are well established (Brooks and Wallingford, 2015; Werner and Mitchell, 2013), we have not found them to be effective for time lapse analysis of individual growing cilia. We therefore developed a new approach for quantifying the relative rates of ciliary beating machinery deployment in growing axonemes. Numbers of tested axonemes, cells, and embryos for each protein examined below are provided in the Materials and Methods.

We used GFP fusions to visualize ciliary proteins and co-expressed memRFP to visualize the entire axoneme. Because all elements of the beating machinery ultimately extend to similar distal positions in later stage axonemes (i.e. st. 27; Fig. 1), relative rates of deployment can be assessed by examining growing axonemes of differing lengths and plotting the coverage of GFP-decoration against total axoneme length. Since mature axonemes on Xenopus MCCs are ~15~20 microns in length, we considered only those < 7 microns in length here to ensure that we analyzed only actively growing axonemes.

We used this method first to examine two MIPs, Enkur and Cfap52 (Dougherty et al., 2020; Sigg et al., 2017), and we found that both displayed essentially a one-to-one correlation to overall axoneme length during growth (Fig. 3A, D). This result is consistent with the fact that Enkur and Cfap52 are tightly embedded within the outer microtubule doublets of the axoneme (Gui et al., 2021; Li et al., 2022). The radial spoke protein Nme5 displayed similarly swift kinetics, extending at the same rate as the MIPs and the overall axoneme (Fig. 3B, E).

Figure 3:

A-C) Ciliary proteins fused to GFP displayed with memRFP visualizing the entire axoneme in growing axoneme. D-F) Plots of total axoneme length versus the length of the axoneme decorated by the labeled protein. Note that Cfap52 is re-plotted in the two panels to facilitate comparison. G-L) Double labeling confirms that radial spoke protiens (Nme5, Rsph1) do not display consistent differences from Cfap52, while the central apparatus proteins (Ak7, Spef2) displayed distinct kinetics, lagging behind Cfap52, Nme5 and Rsph1. Numbers of tested axonemes, cells and embryos for each protein are provided in the materials and methods. Scale bar = 5 μm, scale bar for insets = 0.5 μm

By contrast, the central apparatus protein Ak7 displayed distinct kinetics, lagging well behind Enkur and Cfap52 (Fig. 3C, D). The central apparatus is subdivided into C1 and C2 regions (Loreng and Smith, 2017), and Ak7 is a component of C2 region. It’s notable then that another C2 protein, Cfap266 (Dai et al., 2020; Zhao et al., 2019) also displayed identical kinetics (Fig. 3F). (Note: To facilitate comparisons, certain data are re-plotted in multiple panels. Summary statistics for all data are presented in Fig. 5G, H, below).

Figure 5:

A-C) Additional elements of ciliary beating machineries display unexpected kinetics, and dual labeling confirms these relative rates (D-F). Note that data for Ccdc65 and Dnai2 are re-plotted in multiple panels to facilitate comparison. G) Summary of ciliary beating machinery deployment kinetics. Graph shows the mean ratio of decorated axoneme length versus total axoneme length for each protein. H) Heatmap with adjusted p-values representing all pairwise comparisons. Significant differences are indicated in white, and no difference is indicated in dark green. Numbers of tested axonemes, cells and embryos for each protein are provided in the materials and methods. Scale bar = 5 μm, scale bar for insets = 0.5 μm

To confirm these relative rates of deployment in axonemes, we next co-expressed RFP and GFP fusions to representative pairs of ciliary proteins. For example, we consistently observed an RFP-Cfap52-positive and GFP-Ak7-negative region in the distal axoneme of cells co-expressing the two (Fig. 3G), consistent with Ak7 deployment lagging that of Cfap52 (Fig. 3D). By contrast, when we co-expressed the radial spoke proteins Rsph1 or GFP-Nme5 together with RFP-Cfap52, we observed no consistent extension of one reporter distal to the other, though RFP-only or GFP-only regions were sometimes observed (Fig. 3H, I). In addition, Ak7 lagged behind radial spoke proteins, Nme5 and Rsph1 while its deployment is similar to that a C1 protein, Spef2 on the growing axonemes (Fig.3J–L). Thus, the kinetics of MIPs and radial spokes suggest that they are directly integrated into the growing axoneme as it is assembled, while the central apparatus is delayed in its deployment.

Deployment of dynein arms is delayed relative to axoneme elongation, and IDA and ODA motors display distinct kinetics

We next examined the deployment of dynein arms by co-expressing ODA or IDA subunits fused to GFP together with memRFP (Fig. 4A, B) and observed interesting differences in their kinetics. First, deployment of the ODA intermediate chain Dnai2 lagged well behind Enkur and overall axoneme growth as reported by memRFP (Fig. 4C), and when co-expressed, the GFP-Enkur signal consistently extended more distally than did GFP-Dnai2 (Fig. 4D). Another ODA subunit, the light chain Dnal4, displayed kinetics similar to Dnai2 (Fig. 4C), together suggesting that ODA deployment lags well behind axoneme elongation.

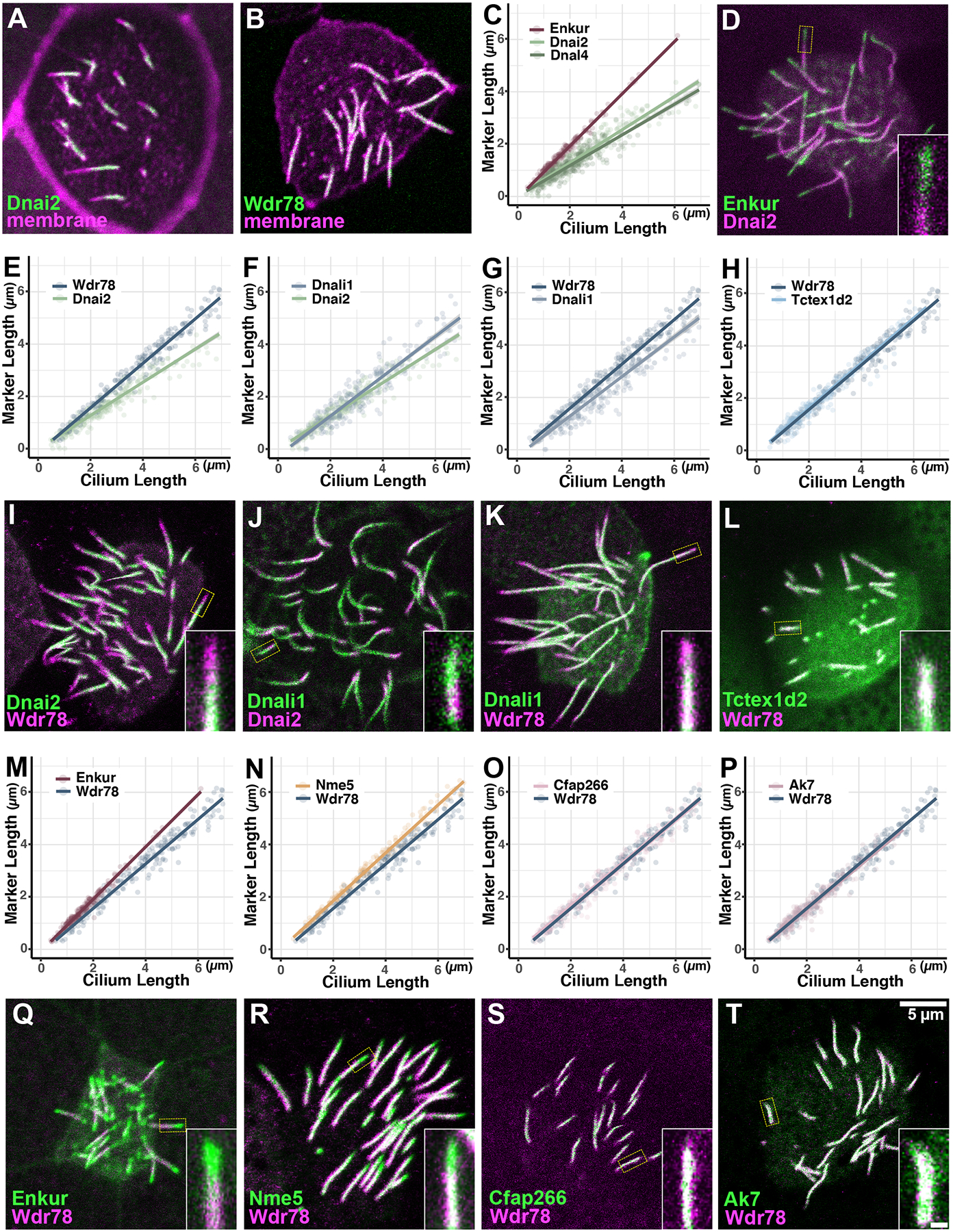

Figure 4:

A, B) Dnai2 and Wdr78 are clearly absent from the distal region of immature axonemes. C) ODA subunits display far slower deployment kinetics as compared to the MIP, Enkur. D) Dual labeling reveals that Enkur consistently extends distally to Dnai2 in growing axonemes, consistent with their distinct kinetics in C. E-H) IDAs display faster deployment kinetics than ODAs, and IDA sub-types display distinct kinetics. I-L) Dual labeling confirms relative rates of deployment for ODA/IDA subunits. M-P) IDAs deploy at rates slower than MIPs and radial spokes, and similar to the central apparatus. Q-T) Dual labeling confirms kinetic data on rates of IDA deployment. Note that data for Wdr78 and Dnai2 are re-plotted in multiple panels to facilitate comparison. Numbers of tested axonemes, cells and embryos for each protein are provided in the materials and methods. Scale bar = 5 μm, scale bar for insets = 0.5 μm

While ODAs drive ciliary beating, a larger and more diverse set of IDAs tune the waveform (Fig. 1A, right)(Yamamoto et al., 2021). We next examined the IDA(f) subunit Wdr78 and the IDA(a,c,d) subunit Dnali1 and found that each deployed faster than did the ODAs (Fig. 4E, F), though the two IDAs were not identical. Indeed, Dnali1 lagged subtly behind Wdr78 (Fig. 4G). Another IDA(f) subunit, Tctex1d2 (aka Dynlt2b) displayed kinetics identical to Wdr78 (Fig. 4H), suggesting the possibility that the distinct kinetics between Dnali1 and Wdr78 does not relate to specific protein subunits but rather more generally to IDA sub-types. Each of these results was confirmed by dual-labeling (Fig. 4I–L).

For a more comprehensive comparison, we then plotted the kinetics of IDA(f) subunit Wdr78 relative to the MIP Enkur and radial spoke protein Nme5 and found that Wdr78 lagged subtly behind (Fig. 4M, N). This result prompted us to compare IDA(f) to the central apparatus, and we found that Wdr78 displayed kinetics identical to those displayed by Cfap266 or Ak7 (Fig. 4O, P). These results, too, were confirmed by dual-labeling experiments (Fig. 4Q–T).

Divergent patterns of deployment kinetics for other elements of the beating machineries

Thus far, a certain coherence can be perceived in the relative rates of deployment for ciliary beating machines, as multiple MIPs share kinetics, as do multiple central apparatus proteins, IDA(f) subunits or ODA subunits. However, this coherence did not extend to additional elements of the cilia beating machinery. For example, the Nexin Dynein Regulatory Complex (N-DRC) is a key regulator of ODA function, but the N-DRC component CCdc65 (Austin-Tse et al., 2013; Horani et al., 2013) displayed far faster kinetics than did the ODA subunits (Fig 5A). In fact, Ccdc65 kinetics were very similar to Enkur and Cfap52 (Fig. 5B), suggesting it may be continuously integrated as the axoneme assembles. Another example is the ODA docking complex protein, Ttc25 (Wallmeier et al., 2016). This protein is essential for the docking of ODAs to the axoneme, but it displayed far faster deployment kinetics than did either ODA subunit examined (Fig. 5C). This result suggests that the docking complex is deployed to axonemes in advance of the transport of the ODAs themselves. These results were confirmed by dual-labeling experiments (Fig. 5D–F).

Discussion:

The development of MCCs begins with their specification by an evolutionarily conserved transcriptional regulatory network and ultimately ends with the assembly and polarization of beating cilia (Brooks and Wallingford, 2014; Mahjoub et al., 2022). Here, we used low-level overexpression of GFP fusions to quantify patterns of deployment of diverse ciliary proteins into nascent cilia. With the caveat that these reporters are present in the background of the endogenous proteins, we report the relative rates of axonemal deployment of diverse machines required for normal ciliary beating in growing MCC cilia in Xenopus (Fig. 5G, H).

By combining quantification of axonemal deployment rates with two-color dual labeling of pairs of axonemal proteins, we find a consistent order to the deployment of these machineries. MIPs and radial spokes are deployed at the same rate as overall axoneme growth, suggesting they may be continuously integrated as the doublets are assembled. The central apparatus and the IDA(f) subtype follow slightly behind the MIPs and radial spokes, with IDA(a,c,d) lagging slightly behind. The last elements to be deployed to developing MCC axonemes are the ODAs. (Fig. 5G)

This series of results raises several interesting points: First, deployment of all IDA and ODA subunits examined here lagged behind Enkur, and thus behind the axoneme generally, suggesting that neither IDA nor ODA deployment is directly integrated with axoneme growth. Second, the kinetics for two ODA subunits were similar, but not identical (Fig. 5G, H). Given the strong evidence that axonemal dyneins are pre-assembled in the cytoplasm and deployed to axonemes as intact motors (Qiu and Roy, 2022), this result may reflect a subtle weakness in our methodology. On the other hand, since only one of our 13 pairwise comparisons deviated from expectation and both ODA subunits were clearly more slowly deployed than any IDA subunit or other component, this result may reflect an as yet unknown subtlety to Dnal4. Indeed, this subunit is relatively poorly studied but notably is not essential for overall ODA integrity, unlike other ODA light chains (Tanner et al., 2008). We note as well, that the two IDA(f) subunits observed displayed identical kinetics, and more0ver these diverged from the kinetics of IDA(a,c,d) (Fig. 5G, H), suggesting that those IDA subtypes are deployed to the axoneme independently.

Moreover, the distinct rates observed for IDA and ODA deployment add yet another piece to the complex puzzle surrounding the regulation of these motors (Desai et al., 2018; Qiu and Roy, 2022). Dynein arms generally are thought to be transported by IFT (Hou et al., 2007; Pazour et al., 1998; Qin et al., 2004; Viswanadha et al., 2014), and we find not only that ODAs and IDAs display widely divergent rates of axonemal deployment, but also that even different IDA sub-types display subtly distinct rates. These results in vertebrate MCCs are consistent with the findings in Chlamydomonas that while IDA deployment via the adaptor Ida3 is a length-dependent process (Hunter et al., 2018; Viswanadha et al., 2014), ODA deployment via the Oda16 adaptor is not (Ahmed et al., 2008; Hou and Witman, 2017; Taschner et al., 2017). It will be important and interesting to ask if other types of motile cilia in vertebrates such as mammalian airway or brain MCCs or nodal cilia which lack the central pair display similar patterns to those reported here.

Finally, our results also raise interesting questions about the relationships between beating machineries and IFT, which transports a wide array of ciliary cargoes and essential for ciliogenesis (Lechtreck, 2015). In Chlamydomonas, live imaging has revealed, for example, tubulin for the outer doublet microtubules is a known cargo of IFT (e.g. (Bhogaraju et al., 2013; Craft et al., 2015; Marshall and Rosenbaum, 2001)), but recent work suggests that diffusion transports the majority of tubulin (Craft Van De Weghe et al., 2020). It will be interesting, then, to determine if IFT or diffusion accounts for the rapid deployment of MIPs into axonemes. Similarly, radial spokes are known cargoes of IFT (Lechtreck et al., 2022; Qin et al., 2004), yet they deploy at rates similar to that of the growing axonemes, raising the possibility that -like tubulin- they may also undergo substantial diffusive movement during axoneme growth. Comparable studies to assess the mechanisms of transport (i.e. active IFT-based vs. diffusion and capture) for different ciliary machineries in growing and steady-state axonemes in vertebrate MCCs will be of interest.

Materials and Methods:

Xenopus embryo manipulations:

Xenopus embryo manipulations were carried out using standard protocols. Briefly, female adult Xenopus were induced to ovulate by injection of hCG (human chorionic gonadotropin). In vitro fertilization was carried out by homogenizing a small fraction of a testis in 1X Marc’s Modified Ringer’s (MMR). Embryos were dejellied in 1/3x MMR with 2.5 %(w/v) cysteine (pH7.8). Embryos were microinjected with mRNA in 2 % Ficoll (w/v) in 1/3x MMR and injected embryos were washed with 1/3x MMR after 30min.

Plasmids for microinjections:

Xenopus gene sequences were obtained from Xenbase (www.xenbase.org) and open reading frames (ORF) of genes were amplified from the Xenopus cDNA library by polymerase chain reaction (PCR), and then are inserted into a pCS10R vector containing a fluorescence tag. These constructs were linearized, and the capped mRNAs were synthesized using mMESSAGE mMACHINE SP6 transcription kit (ThermoFisher Scientific). 40~80 pg of each mRNA was injected into two ventral blastomeres at 4-cell stage.

Imaging and image analysis:

For overall Xenopus embryos were mounted between cover glass and submerged in 1/3x MMR at tadpole stages, and then were imaged immediately. Live images were captured with a Zeiss LSM700 laser scanning confocal microscope using a plan-apochromat 63X/1.4 NA oil objective lens (Zeiss) or with Nikon eclipse Ti confocal microscope with a 63×/1.4 oil immersion objective. To quantify the relative rates of ciliary machinery deployment in growing axonemes, GFP fused ciliary proteins and membrane RFP were co-expressed and images were captured at stage 21 or 22. Number for tested axonemes, cell and embryos are as follows : Enkur (185 axonemes, 33 cells and 7 embryos), Cfap52 (235 axonemes, 34 cells and 8 embryos), Ccdc65 (218 axonemes, 28cells and 7 embryos), Nme5 (172 axonemes, 30 cells and 6 embryos), Wdr78 (210 axonemes, 31 cells and 6embryos), Tctex1d2/Dynlt2b(224 axonemes, 32 cells and 5 embryos), CCfap266 (240 axonemes, 34 cells and 9 embryos), Ak7 (288 axonemes, 30 cells and 5 embryos), Spef2 (197 axonemes, 39 cells and 7 embryos), Ttc25(248 axonemes, 33 cells and 7 embryos), Dnali1 (227 axonemes, 34 cells and 8 embryos), Dnai2(285 axonemes, 32 cells and 8 embryos) and Dnal4 (250 axonemes, 30 cells and 7 embryos). Measurements of protein deployments and axoneme lengths were done in Fiji. Analyzed data were visualized using RStudio. P-values were calculated by one-way ANOVA test and Tukey HSD (Honestly Significant Difference) test in R.

Acknowledgements:

Thea authors thank Sarah Ortiz for initial characterization of the Dnali1 fusion protein. This work was supported by the NHLBI (R01HL117164).

References:

- Ahmed NT, Gao C, Lucker BF, Cole DG, and Mitchell DR. 2008. ODA16 aids axonemal outer row dynein assembly through an interaction with the intraflagellar transport machinery. J Cell Biol. 183:313–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderegg L, Im Hof Gut M, Hetzel U, Howerth EW, Leuthard F, Kyostila K, Lohi H, Pettitt L, Mellersh C, Minor KM, Mickelson JR, Batcher K, Bannasch D, Jagannathan V, and Leeb T. 2019. NME5 frameshift variant in Alaskan Malamutes with primary ciliary dyskinesia. PLoS Genet. 15:e1008378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin-Tse C, Halbritter J, Zariwala MA, Gilberti RM, Gee HY, Hellman N, Pathak N, Liu Y, Panizzi JR, Patel-King RS, Tritschler D, Bower R, O’Toole E, Porath JD, Hurd TW, Chaki M, Diaz KA, Kohl S, Lovric S, Hwang DY, Braun DA, Schueler M, Airik R, Otto EA, Leigh MW, Noone PG, Carson JL, Davis SD, Pittman JE, Ferkol TW, Atkinson JJ, Olivier KN, Sagel SD, Dell SD, Rosenfeld M, Milla CE, Loges NT, Omran H, Porter ME, King SM, Knowles MR, Drummond IA, and Hildebrandt F. 2013. Zebrafish Ciliopathy Screen Plus Human Mutational Analysis Identifies C21orf59 and CCDC65 Defects as Causing Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia. Am J Hum Genet. 93:672–686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhogaraju S, Cajanek L, Fort C, Blisnick T, Weber K, Taschner M, Mizuno N, Lamla S, Bastin P, Nigg EA, and Lorentzen E. 2013. Molecular basis of tubulin transport within the cilium by IFT74 and IFT81. Science. 341:1009–1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks ER, and Wallingford JB. 2014. Multiciliated cells. Curr Biol. 24:R973–982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks ER, and Wallingford JB. 2015. In vivo investigation of cilia structure and function using Xenopus. Methods Cell Biol. 127:131–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bui KH, Yagi T, Yamamoto R, Kamiya R, and Ishikawa T. 2012. Polarity and asymmetry in the arrangement of dynein and related structures in the Chlamydomonas axoneme. J Cell Biol. 198:913–925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craft JM, Harris JA, Hyman S, Kner P, and Lechtreck KF. 2015. Tubulin transport by IFT is upregulated during ciliary growth by a cilium-autonomous mechanism. J Cell Biol. 208:223–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craft Van De Weghe J, Harris JA, Kubo T, Witman GB, and Lechtreck KF. 2020. Diffusion rather than intraflagellar transport likely provides most of the tubulin required for axonemal assembly in Chlamydomonas. J Cell Sci. 133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai D, Ichikawa M, Peri K, Rebinsky R, and Huy Bui K. 2020. Identification and mapping of central pair proteins by proteomic analysis. Biophys Physicobiol. 17:71–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai PB, Dean AB, and Mitchell DR. 2018. Cytoplasmic preassembly and trafficking of axonemal dyneins. In Dyneins: Structure, Biology, and Disease. Vol. 1. King SM, editor. Academic Press/Elsevier, London. [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty GW, Loges NT, Klinkenbusch JA, Olbrich H, Pennekamp P, Menchen T, Raidt J, Wallmeier J, Werner C, Westermann C, Ruckert C, Mirra V, Hjeij R, Memari Y, Durbin R, Kolb-Kokocinski A, Praveen K, Kashef MA, Kashef S, Eghtedari F, Haffner K, Valmari P, Baktai G, Aviram M, Bentur L, Amirav I, Davis EE, Katsanis N, Brueckner M, Shaposhnykov A, Pigino G, Dworniczak B, and Omran H. 2016. DNAH11 Localization in the Proximal Region of Respiratory Cilia Defines Distinct Outer Dynein Arm Complexes. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 55:213–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty GW, Mizuno K, Nöthe-Menchen T, Ikawa Y, Boldt K, Ta-Shma A, Aprea I, Minegishi K, Pang YP, Pennekamp P, Loges NT, Raidt J, Hjeij R, Wallmeier J, Mussaffi H, Perles Z, Elpeleg O, Rabert F, Shiratori H, Letteboer SJ, Horn N, Young S, Strünker T, Stumme F, Werner C, Olbrich H, Takaoka K, Ide T, Twan WK, Biebach L, Große-Onnebrink J, Klinkenbusch JA, Praveen K, Bracht DC, Höben IM, Junger K, Gützlaff J, Cindrić S, Aviram M, Kaiser T, Memari Y, Dzeja PP, Dworniczak B, Ueffing M, Roepman R, Bartscherer K, Katsanis N, Davis EE, Amirav I, Hamada H, and Omran H. 2020. CFAP45 deficiency causes situs abnormalities and asthenospermia by disrupting an axonemal adenine nucleotide homeostasis module. Nat Commun. 11:5520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drysdale TT, and Elinson RP. 1992. Cell migration and induction in the development of the surface ectodermal patttern of the Xenopus laevis tadpole. Dev. Growth & Differ 34:51–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutcher SK 2020. Asymmetries in the cilia of Chlamydomonas. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 375:20190153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fliegauf M, Olbrich H, Horvath J, Wildhaber JH, Zariwala MA, Kennedy M, Knowles MR, and Omran H. 2005. Mislocalization of DNAH5 and DNAH9 in respiratory cells from patients with primary ciliary dyskinesia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 171:1343–1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray RS, Abitua PB, Wlodarczyk BJ, Szabo-Rogers HL, Blanchard O, Lee I, Weiss GS, Liu KJ, Marcotte EM, Wallingford JB, and Finnell RH. 2009. The planar cell polarity effector Fuz is essential for targeted membrane trafficking, ciliogenesis and mouse embryonic development. Nat Cell Biol. 11:1225–1232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gui M, Farley H, Anujan P, Anderson JR, Maxwell DW, Whitchurch JB, Botsch JJ, Qiu T, Meleppattu S, Singh SK, Zhang Q, Thompson J, Lucas JS, Bingle CD, Norris DP, Roy S, and Brown A. 2021. De novo identification of mammalian ciliary motility proteins using cryo-EM. Cell. 184:5791–5806.e5719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris JA, Liu Y, Yang P, Kner P, and Lechtreck KF. 2015. Single particle imaging reveals IFT-independent transport and accumulation of EB1 in Chlamydomonas flagella. Mol Biol Cell. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horani A, Brody SL, Ferkol TW, Shoseyov D, Wasserman MG, Ta-shma A, Wilson KS, Bayly PV, Amirav I, Cohen-Cymberknoh M, Dutcher SK, Elpeleg O, and Kerem E. 2013. CCDC65 mutation causes primary ciliary dyskinesia with normal ultrastructure and hyperkinetic cilia. PLoS One. 8:e72299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou Y, Qin H, Follit JA, Pazour GJ, Rosenbaum JL, and Witman GB. 2007. Functional analysis of an individual IFT protein: IFT46 is required for transport of outer dynein arms into flagella. J Cell Biol. 176:653–665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou Y, and Witman GB. 2017. The N-terminus of IFT46 mediates intraflagellar transport of outer arm dynein and its cargo-adaptor ODA16. Mol Biol Cell. 28:2420–2433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter EL, Lechtreck K, Fu G, Hwang J, Lin H, Gokhale A, Alford LM, Lewis B, Yamamoto R, Kamiya R, Yang F, Nicastro D, Dutcher SK, Wirschell M, and Sale WS. 2018. The IDA3 adapter, required for intraflagellar transport of I1 dynein, is regulated by ciliary length. Mol Biol Cell. 29:886–896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichikawa M, and Bui KH. 2018. Microtubule Inner Proteins: A Meshwork of Luminal Proteins Stabilizing the Doublet Microtubule. Bioessays. 40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalifa AAZ, Ichikawa M, Dai D, Kubo S, Black CS, Peri K, McAlear TS, Veyron S, Yang SK, Vargas J, Bechstedt S, Trempe JF, and Bui KH. 2020. The inner junction complex of the cilia is an interaction hub that involves tubulin post-translational modifications. Elife. 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King SM 2018. Composition and assembly of axonemal dyneins. In Dyneins. Elsevier. 162–201. [Google Scholar]

- Konjikusic MJ, Lee C, Yue Y, Shrestha BD, Nguimtsop AM, Horani A, Brody S, Prakash VN, Gray RS, Verhey KJ, and Wallingford JB. 2022. Kif9 is an active kinesin motor required for ciliary beating and proximodistal patterning of motile axonemes. Journal of Cell Science. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lechtreck KF 2015. IFT-Cargo Interactions and Protein Transport in Cilia. Trends Biochem Sci. 40:765–778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lechtreck KF, Gould TJ, and Witman GB. 2013. Flagellar central pair assembly in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Cilia. 2:15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lechtreck KF, Liu Y, Dai J, Alkhofash RA, Butler J, Alford L, and Yang P. 2022. Chlamydomonas ARMC2/PF27 is an obligate cargo adapter for intraflagellar transport of radial spokes. Elife. 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C, Cox RM, Papoulas O, Horani A, Drew K, Devitt CC, Brody SL, Marcotte EM, and Wallingford JB. 2020. Functional partitioning of a liquid-like organelle during assembly of axonemal dyneins. Elife. 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C, Wallingford JB, and Gross JM. 2014. Cluap1 is essential for ciliogenesis and photoreceptor maintenance in the vertebrate eye. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 55:4585–4592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Fernandez JJ, Fabritius AS, Agard DA, and Winey M. 2022. Electron cryo-tomography structure of axonemal doublet microtubule from Tetrahymena thermophila. Life Sci Alliance. 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin J, Yin W, Smith MC, Song K, Leigh MW, Zariwala MA, Knowles MR, Ostrowski LE, and Nicastro D. 2014. Cryo-electron tomography reveals ciliary defects underlying human RSPH1 primary ciliary dyskinesia. Nat Commun. 5:5727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loreng TD, and Smith EF. 2017. The Central Apparatus of Cilia and Eukaryotic Flagella. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahjoub MR, Nanjundappa R, and Harvey MN. 2022. Development of a multiciliated cell. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 77:102105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall WF, and Rosenbaum JL. 2001. Intraflagellar transport balances continuous turnover of outer doublet microtubules: implications for flagellar length control. J Cell Biol. 155:405–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oltean A, Schaffer AJ, Bayly PV, and Brody SL. 2018. Quantifying Ciliary Dynamics during Assembly Reveals Stepwise Waveform Maturation in Airway Cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 59:511–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omran H, Kobayashi D, Olbrich H, Tsukahara T, Loges NT, Hagiwara H, Zhang Q, Leblond G, O’Toole E, Hara C, Mizuno H, Kawano H, Fliegauf M, Yagi T, Koshida S, Miyawaki A, Zentgraf H, Seithe H, Reinhardt R, Watanabe Y, Kamiya R, Mitchell DR, and Takeda H. 2008. Ktu/PF13 is required for cytoplasmic pre-assembly of axonemal dyneins. Nature. 456:611–616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pazour GJ, Wilkerson CG, and Witman GB. 1998. A dynein light chain is essential for the retrograde particle movement of intraflagellar transport (IFT). J Cell Biol. 141:979–992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piperno G, and Ramanis Z. 1991. The proximal portion of Chlamydomonas flagella contains a distinct set of inner dynein arms. J Cell Biol. 112:701–709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin H, Diener DR, Geimer S, Cole DG, and Rosenbaum JL. 2004. Intraflagellar transport (IFT) cargo: IFT transports flagellar precursors to the tip and turnover products to the cell body. J Cell Biol. 164:255–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu T, and Roy S. 2022. Ciliary dynein arms: Cytoplasmic preassembly, intraflagellar transport, and axonemal docking. J Cell Physiol. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigg MA, Menchen T, Lee C, Johnson J, Jungnickel MK, Choksi SP, Garcia G 3rd, Busengdal H, Dougherty GW, Pennekamp P, Werner C, Rentzsch F, Florman HM, Krogan N, Wallingford JB, Omran H, and Reiter JF. 2017. Evolutionary Proteomics Uncovers Ancient Associations of Cilia with Signaling Pathways. Dev Cell. 43:744–762.e711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soares H, Carmona B, Nolasco S, Viseu Melo L, and Goncalves J. 2019. Cilia Distal Domain: Diversity in Evolutionarily Conserved Structures. Cells. 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stubbs JL, Davidson L, Keller R, and Kintner C. 2006. Radial intercalation of ciliated cells during Xenopus skin development. Development. 133:2507–2515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanner CA, Rompolas P, Patel-King RS, Gorbatyuk O, Wakabayashi K, Pazour GJ, and King SM. 2008. Three members of the LC8/DYNLL family are required for outer arm dynein motor function. Mol Biol Cell. 19:3724–3734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarkar A, Loges NT, Slagle CE, Francis R, Dougherty GW, Tamayo JV, Shook B, Cantino M, Schwartz D, Jahnke C, Olbrich H, Werner C, Raidt J, Pennekamp P, Abouhamed M, Hjeij R, Kohler G, Griese M, Li Y, Lemke K, Klena N, Liu X, Gabriel G, Tobita K, Jaspers M, Morgan LC, Shapiro AJ, Letteboer SJ, Mans DA, Carson JL, Leigh MW, Wolf WE, Chen S, Lucas JS, Onoufriadis A, Plagnol V, Schmidts M, Boldt K, Roepman R, Zariwala MA, Lo CW, Mitchison HM, Knowles MR, Burdine RD, Loturco JJ, and Omran H. 2013. DYX1C1 is required for axonemal dynein assembly and ciliary motility. Nat Genet. 45:995–1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taschner M, Mourão A, Awasthi M, Basquin J, and Lorentzen E. 2017. Structural basis of outer dynein arm intraflagellar transport by the transport adaptor protein ODA16 and the intraflagellar transport protein IFT46. J Biol Chem. 292:7462–7473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viswanadha R, Hunter EL, Yamamoto R, Wirschell M, Alford LM, Dutcher SK, and Sale WS. 2014. The ciliary inner dynein arm, I1 dynein, is assembled in the cytoplasm and transported by IFT before axonemal docking. Cytoskeleton (Hoboken). 71:573–586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walentek P, and Quigley IK. 2017. What we can learn from a tadpole about ciliopathies and airway diseases: Using systems biology in Xenopus to study cilia and mucociliary epithelia. Genesis. 55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallmeier J, Shiratori H, Dougherty GW, Edelbusch C, Hjeij R, Loges NT, Menchen T, Olbrich H, Pennekamp P, Raidt J, Werner C, Minegishi K, Shinohara K, Asai Y, Takaoka K, Lee C, Griese M, Memari Y, Durbin R, Kolb-Kokocinski A, Sauer S, Wallingford JB, Hamada H, and Omran H. 2016. TTC25 Deficiency Results in Defects of the Outer Dynein Arm Docking Machinery and Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia with Left-Right Body Asymmetry Randomization. Am J Hum Genet. 99:460–469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner ME, and Mitchell BJ. 2012. Understanding ciliated epithelia: the power of Xenopus. Genesis. 50:176–185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner ME, and Mitchell BJ. 2013. Using Xenopus skin to study cilia development and function. Methods Enzymol. 525:191–217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yagi T, Uematsu K, Liu Z, and Kamiya R. 2009. Identification of dyneins that localize exclusively to the proximal portion of Chlamydomonas flagella. J Cell Sci. 122:1306–1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi H, Oda T, Kikkawa M, and Takeda H. 2018. Systematic studies of all PIH proteins in zebrafish reveal their distinct roles in axonemal dynein assembly. eLife. 7:e36979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto R, Hwang J, Ishikawa T, Kon T, and Sale WS. 2021. Composition and function of ciliary inner-dynein-arm subunits studied in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Cytoskeleton (Hoboken). 78:77–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao L, Hou Y, Picariello T, Craige B, and Witman GB. 2019. Proteome of the central apparatus of a ciliary axoneme. J Cell Biol. 218:2051–2070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X, Liu Y, and Yang P. 2017. Radial Spokes-A Snapshot of the Motility Regulation, Assembly, and Evolution of Cilia and Flagella. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]