Abstract

Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS), a neurologic disease characterized by acute paralysis, is frequently preceded by Campylobacter jejuni infection. Serotype O19 strains are overrepresented among GBS-associated C. jejuni isolates. We previously showed that all O19 strains tested were closely related to one another by randomly amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) and restriction fragment length polymorphism analyses. RAPD analysis demonstrated a 1.4-kb band in all O19 strains tested but in no non-O19 strains. We cloned this O19-specific band; nucleotide sequence analysis revealed a truncated open reading frame with significant homology to DNA gyrase subunit B (gyrB) of Helicobacter pylori. PCR using the random primer and a primer specific for gyrB showed that in non-O19 strains, the random primer did not recognize the downstream gyrB binding site. The regions flanking each of the random primer binding sites were amplified by degenerate PCR for further sequencing. Although the random primer had several mismatches with the downstream gyrB binding site, a single nucleotide polymorphism 6 bp upstream from the 3′ terminus was found to distinguish O19 and non-O19 strains. PCR using 3′-mismatched primers based on this polymorphism was designed to differentiate O19 strains from non-O19 strains. When a total of 42 (18 O19 and 24 non-O19) strains from five different countries were examined, O19 strains were distinguishable from non-O19 strains in each case. This PCR method should permit identification of O19 C. jejuni strains.

Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) is a neurologic disease characterized by ascending paralysis that can lead to respiratory muscle compromise and death (3, 11). Although the exact trigger of GBS is unknown, case control studies have shown that GBS is frequently preceded by acute infectious illness (11, 21). In recent decades, serologic and cultural studies have suggested that Campylobacter jejuni infection is one of the most important triggers of GBS (2, 5, 23). Culture confirmation of preceding C. jejuni infection in 8 to 50% of GBS patients has been achieved (2), despite the fact that many GBS patients with antecedent Campylobacter infection are likely to have already cleared their stools by the time neurologic symptoms begin.

C. jejuni strains isolated from the stools of patients with GBS include Penner serotypes O1, O2, O10, O19, O41, and O64 (8, 13, 14, 17, 28). Among the diverse lipopolysaccharide molecules of C. jejuni strains, some structures closely resemble human gangliosides (4, 22, 30, 41–43), suggesting that molecular mimicry could trigger the neuronal injury observed in GBS. O19 strains account for 83 and 29% of GBS-associated C. jejuni isolates in Japan (8, 14) and the United States (3), respectively, but for <3% of C. jejuni isolates from patients with uncomplicated gastroenteritis in both countries (25, 26). About one of every thousand Campylobacter infections of any serotype results in GBS; however, the risk of developing GBS after infection with an O19 C. jejuni strain is estimated to be about 1 in 158 (2). We hypothesized that O19 strains (especially those isolated from GBS patients) have close genetic relationships to one another and that they may represent a particularly virulent clone. To test this hypothesis, the genetic variation among GBS-associated C. jejuni and enteritis-associated (control) strains was determined by randomly amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) and restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analyses (7). Although each of the non-O19 strains had a unique pattern, whether they shared O or Lior serotypes, all O19 strains tested were closely related, regardless of Lior serotype, country of origin, or whether they were GBS associated (7). RAPD analysis using primer D14307 (1) revealed a 1.4-kb band shared by all O19 strains tested, but not in the non-O19 strains (7). We now ask whether genetic differences can be used to distinguish O19 from non-O19 strains for clinical purposes. Our goals in the present study were to clone the O19-specific RAPD band, to determine its nucleotide sequence, and to define differences between O19 and non-O19 strains. As a result of these studies, a PCR technique using 3′-mismatched primers (9, 15, 19) that differentiates O19 from non-O19 strains was developed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture conditions.

A total of 42 C. jejuni strains, including 18 O19 strains and 24 strains of other serotypes, isolated from patients with GBS or with uncomplicated enteritis in five different countries were used in this study (Table 1). Strains were suspended in brucella broth (BBL Microbiology Systems, Cockeysville, Md.) containing 15% glycerol (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) and stored at −70°C until tested. The thawed bacteria were cultured microaerobically (10% CO2, 5% O2 and 85% N2) on Trypticase soy agar containing 5% sheep blood (BBL) at 37°C for 48 h. The strains had been typed according to the Penner (O) (27) and Lior (18) serotyping schemes described previously (7). C. jejuni D450 (O19 and GBS), D3083 (O19 and non-GBS), 84-196 (non-O19 and GBS), and 85-1 (non-O19 and non-GBS) strains (Table 1) were used for the DNA sequence analyses. Escherichia coli DH5α was grown in L broth or on L plates (31).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains used in this study

| Strain | Serotype

|

Clinical setting | Country of origina | PCRb

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O | H | O19 | Non-O19 | |||

| 84-158 | 19 | 84 | GBS | Germany | + | − |

| D445 | 19 | 77 | GBS | US | + | − |

| D450 | 19 | 77 | GBS | US | + | − |

| D452 | 19 | 77 | GBS | US | + | − |

| OH4382 | 19 | 7 | GBS | Japan | + | − |

| CUM001 | 19 | 7 | GBS | Japan | + | − |

| OH4384 | 19 | 7 | GBS | Japan | + | − |

| D3083 | 19 | 7 | Diarrhea | US | + | − |

| D3180 | 19 | 7 | Diarrhea | US | + | − |

| D3145 | 19 | 70 | Diarrhea | US | + | − |

| D3141 | 19 | 70 | Diarrhea | US | + | − |

| D3088 | 19 | 70 | Diarrhea | US | + | − |

| D3226 | 19 | 70 | Diarrhea | US | + | − |

| D3002 | 19 | 84 | Diarrhea | US | + | − |

| D3468 | 19 | 84 | Diarrhea | US | + | − |

| D3409 | 19 | 84 | Diarrhea | US | + | − |

| D3215 | 19 | 23 | Diarrhea | US | + | − |

| 4f | 19 | NDc | Diarrhea | Japan | + | − |

| 93-001 | 1 | ND | GBS | US | − | + |

| 84-196 | 2 | 4 | GBS | Germany | − | + |

| 84-197 | 8, 17 | 40 | GBS | Germany | − | + |

| 86-381 | 2 | 4 | GBS | US | − | + |

| D2769 | 2 | 4 | GBS | US | − | + |

| 97-001 | 11 | ND | GBS | UK | − | + |

| 97-002 | 64 | ND | GBS | UK | − | + |

| 97-003 | 64 | ND | GBS | UK | − | + |

| 97-004 | NTd | ND | GBS | UK | − | + |

| 97-005 | NT | ND | GBS | UK | − | + |

| 84-159 | 1, 8w | 1 | Diarrhea | US | − | + |

| 84-194 | 16, 50 | 7 | Diarrhea | US | − | + |

| 84-195 | 16, 50 | 7 | Diarrhea | US | − | + |

| 85-198 | 1, 8 | 1 | Diarrhea | US | − | + |

| 85-1 | 1, 8w | 4 | Diarrhea | US | − | + |

| 86-386 | 2 | 4 | Diarrhea | US | − | + |

| 86-355 | 15, 38 | 13 | Diarrhea | US | − | + |

| 84-163 | 6, 7, 25 | 6 | Diarrhea | NAe | − | + |

| 85-191 | 2 | 36, 4 | Diarrhea | US | − | + |

| 85-3 | 16, 50 | 6 | Diarrhea | Sweden | − | + |

| 86-357 | NT | 13, 9 | Diarrhea | US | − | + |

| 86-389 | NT | 4 | Diarrhea | US | − | + |

| 81-176 | 23, 36 | 5 | Diarrhea | US | − | + |

| 81-116 | 6 | NT | Diarrhea | UK | − | + |

Abbreviations: US, United States; UK, United Kingdom.

PCR amplification with O19- or non-O19-specific primer. Symbols: +, amplified; −, not amplified.

ND, not determined.

NT, not typeable.

NA, information not available.

Genetic techniques.

Bacteria were grown on blood agar plates for 48 h, and chromosomal DNA was prepared as described previously (7). Plasmids were isolated by using the QIAprep Spin Plasmid Kit (Qiagen Inc. Chatsworth, Calif.) as specified by the manufacturer. DNA fragments from agarose gels were extracted with QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen), and PCR products were purified with the QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen). All other standard molecular genetic techniques were used as described elsewhere (31). The nucleotide sequence was determined with an ABI automated sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Inc., Foster City, Calif.) in the Vanderbilt University Cancer Center Core Facility. Oligonucleotide primers listed in Table 2 were synthesized with an ABI 392 DNA synthesizer (Applied Biosystems). Computer analysis of DNA and protein sequences were performed with the Genetics Computer Group programs; database similarity searches were performed through the National Center for Biotechnology Information by use of the BLASTX algorithm.

TABLE 2.

PCR primers used in this study

| Primera | Positionsb | DNA sequence (5′→3′) |

|---|---|---|

| Random | ||

| D14307 | GGTTGGGTGAGAATTGCACG | |

| Degeneratec | ||

| AN024 (F) | GGNATGTAYATHGGNGAYAC | |

| AN025 (R) | CATNGTNGTYTCCCANAR | |

| Specificd | ||

| A8683 (R) | 532–551 | CTTTCATGTTTGCCTACGCG |

| B7493 (F) | 532–551 | CGCGTAGGCAAACATGAAAG |

| AN263 (F) | 1–22 | ACAAACATAGGCGGACTTCATC |

| AN076 (R) | 334–353 | CCTTCTGAAAATTCTTGACG |

| AN077 (F) | 1548–1567 | AGCTTTGAGCGAATACCTGA |

| C3648 (R) | 2038–2055 | TTGCTCAGGATTCATTTC |

| C3647 (F) | 1222–1239 | CAAGCTATACTGCCTTTG |

| C3650 (R) | 1656–1673 | TCAAGATCTTTTAAAATT |

| C3652 (R) | 1656–1673 | TCAAGATCTTTTAAAATC |

| C3649 (F) | 1639–1656 | GTCGCAGCTTATCGTGCA |

| C3651 (F) | 1639–1656 | GCTGCAGCTTATCGTGCG |

| AN787 (F) | 1643–1656 | CAGCTTATCGTGCA |

| AN789 (F) | 1643–1656 | CAGCTTATCGTGCG |

| AN788 (R) | 1656–1669 | GATCTTTTAAAATT |

| AN790 (R) | 1656–1669 | GATCTTTTAAAATC |

The letters in parentheses indicate the orientation of the primer as follows: F, forward; R, reverse.

Nucleotide positions are based on gyrB sequence from strain D450 (2,055 bp).

The degenerate primers were designed based on conserved amino acid sequences of GyrB from H. pylori, E. coli, and S. typhimurium. AN024 is based on conserved sequence GMYIGDT, and AN025 is based on conserved sequence LWETTM.

O19-specific primers C3650, C3649, AN787, and AN788 (18- or 14-mers) terminating at the mismatched sequences with non-O19 strains were designed based on nucleotide sequences of gyrB from strain D450. Non-O19-specific primers C3652, C3651, and AN787 (18- or 14-mers) terminating at the mismatched sequences with O19 strains were designed based on nucleotide sequences of gyrB from strain 84-196.

PCR techniques.

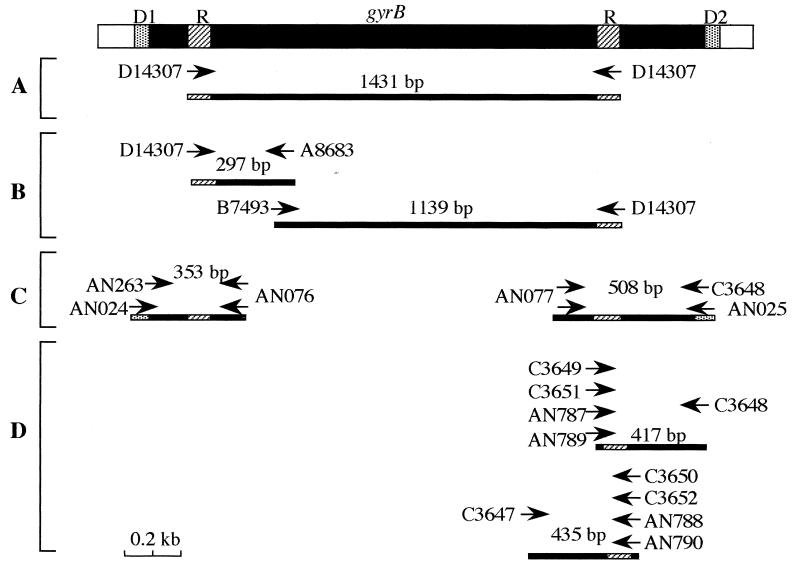

PCR techniques used in this study are schematically shown in Fig. 1.

FIG. 1.

Schematic representations of PCR techniques used in this study. (A) An O19-specific band was amplified by RAPD PCR using primer D14307, as previously described (7). (B) Random primer D14307 was paired with a specific primer (A8683 or B7493) to determine whether the random primer recognizes an analogous binding site among non-O19 strains. (C) To determine the sequences of the regions flanking each D14307 binding site, degenerate primers (AN024 or AN025) were paired with nondegenerate primers (AN076 or AN077). After sequencing from the nondegenerate primer binding site, new primers (AN263 and C3648) specific to each region flanking the degenerate primer binding sites were designed and then nondegenerate PCR was performed. (D) To differentiate O19 strains from non-O19 strains, specific PCR primers for each group were designed. Oligonucleotide primers (14- or 18-mer) terminating at the mismatched sequences observed in the gyrB alleles were synthesized. Primer C3647 or C3648 was paired with each of these specific primers. The random primer (D14307) and degenerate primer binding sites are indicated by hatched areas R and D1 or D2, respectively.

(i) RAPD PCR.

RAPD PCR was conducted by using the 20-mer oligonucleotide D14307, as described previously (1), except for minor modifications. In brief, PCR was performed in a DNA thermal cycler (Perkin-Elmer Cetus, Norwalk, Conn.) in reaction mixtures of 25 μl containing 20 ng of genomic DNA, 2.5 μl of 10× reaction buffer (Qiagen), 3 mM MgCl2, 160 pM primer, 0.625 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Qiagen), and 250 μM each of the four deoxynucleotides, under mineral oil. The PCR program was as follows: (i) 4 cycles, with 1 cycle consisting of 5 min at 94°C, 5 min at 40°C, and 5 min at 72°C, (ii) 30 cycles, with 1 cycle consisting of 1 min at 94°C, 1 min at 55°C, and 2 min at 72°C, and (iii) incubation at 72°C for 10 min to complete the extension. The resulting amplicons were separated by electrophoresis in 1% agarose gels. The 1.4-kb O19-specific band was cloned into pT7Blue (Novagene, Madison, Wis.) to create pTIC120 (strain D450) or pTIC121 (strain D3083).

(ii) Specific PCR.

After sequence analysis of the O19-specific band, new primers specific for the fragment were designed (Table 2). PCR was performed to determine why random primer D14307 failed to amplify a 1.4-kb band in non-O19 strains. Primer A8683 or B7493 was used as a specific upstream or downstream primer. We confirmed that each of these specific primers was able to recognize both O19 and non-O19 strains. To determine whether D14307 bound to either primer binding site among non-O19 strains, PCR amplification was performed for 30 cycles, with 1 cycle consisting of denaturation at 94°C for 1 min, annealing at 50°C for 1 min, and extension at 72°C for 2 min, followed by extension at 72°C for 10 min. The PCR mixture was prepared as described for the RAPD PCR above, except that the concentration of MgCl2 was reduced to 1.5 mM. Six O19 and non-O19 strains were used in this experiment.

(iii) Degenerate PCR.

Nucleotide and amino acid sequence analyses of the 1.4-kb amplicon revealed a truncated open reading frame homologous to known DNA gyrase subunit B (gyrB) (see below). To determine the sequences of the regions flanking each D14307 binding site, degenerate primers were designed and paired with nondegenerate primers. The degenerate primers were synthesized based on conserved amino acid sequences of GyrB from Helicobacter pylori (GenBank accession no. P55923), E. coli (GenBank accession no. P06982), and Salmonella typhimurium (GenBank accession no. Q60008). For the upstream primer binding region within gyrB, the forward degenerate primer AN024, based on the conserved amino acid sequence GMYIGDT, was paired with the reverse specific primer AN076 (Fig. 1). For the downstream primer binding region within gyrB, the reverse degenerate primer AN025, based on conserved amino acid sequence LWETTM, was paired with the specific forward primer AN077. The target DNA was amplified for 30 cycles of PCR, with 1 cycle consisting of denaturation at 94°C for 1 min, annealing of primers for 2 min at 37°C, and primer extension for 3 min at 72°C. The amplicons from two O19 strains (D450 and D3083) were extracted from agarose gels and then purified. After sequencing from the nondegenerate primer binding site, new primers (AN263 and C3648) specific to each region flanking the degenerate primer binding sites were designed and then nondegenerate PCR was performed. Nucleotide sequences of the amplicons from two O19 (D450 and D3083) and non-O19 (84-196 and 85-1) strains were compared.

(iv) PCR using 3′-mismatched primers.

To differentiate O19 from non-O19 strains, PCR using 3′-mismatched primers, a procedure reported to discriminate chromosomal point mutations (9, 15, 19), was adopted. Oligonucleotide primers based on a polymorphic gyrB sequence that differed between O19 and non-O19 strains were synthesized. The 3′-terminal nucleotides of the 14- or 18-mer oligonucleotides were exactly complementary to either O19 or non-O19 target sequences (Table 2). Primer C3647 (forward) or C3648 (reverse) was used with each specific primer. In preliminary experiments, these primers were confirmed to PCR amplify the expected band in both O19 and non-O19 strains (data not shown). The allele-specific PCRs were performed in a 25-μl reaction volume including 10× PCR buffer, 0.625 U of Taq DNA polymerase, 80 pM primer, 250 μM each of the four deoxynucleotides, and 20 ng of template DNA. To evaluate appropriate PCR conditions for distinguishing O19 strains from non-O19 strains, initially two O19 and two non-O19 strains were studied; the annealing temperature was varied, and the resulting amplicons from all strains were compared. The optimal PCR program examined (data not shown) consisted of 40 cycles of PCR, with 1 cycle consisting of denaturation at 94°C for 1 min, annealing for 1 min, and extension at 72°C for 1 min.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The 2,055-nucleotide sequence in gyrB was deposited in GenBank data bank under accession no. AF093760.

RESULTS

Cloning and sequencing of the O19-specific band.

We confirmed our previous result (7), that by RAPD PCR using random primer D14307, a 1.4-kb fragment was detected in two O19 strains but not in two non-O19 strains (data not shown). The O19-specific band was extracted from agarose gels and cloned into pT7Blue. Nucleotide sequence analysis of the cloned amplicons from two O19 strains (D450 and D3083) revealed the presence of an open reading frame of at least 1,431 nucleotides. A search for amino acid sequence homologies revealed that this O19-specific fragment has 64% identity with the DNA gyrase subunit B (encoded by gyrB) of H. pylori. Comparison with the H. pylori sequence showed that the C. jejuni fragment did not contain the nucleotides encoding either the N- or C-terminal region of the intact protein.

Specific PCR analysis.

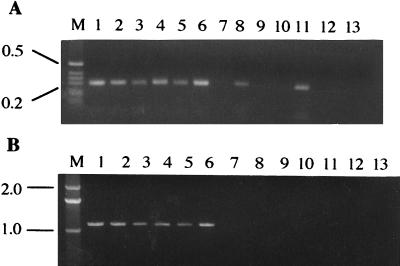

We then sought to determine whether the difference between O19 and non-O19 strains by RAPD PCR might be attributed to mismatched sequences at the sites in gyrB at which D14307 could bind. To confirm our hypothesis, new primers (A8683 and B7493) which bind to both O19 and non-O19 strains were synthesized. When D14307 was used as the 5′ primer with A8683 as the 3′ primer, a band of the expected (0.3-kb) size was detected in all six O19 strains and in two of six non-O19 strains (Fig. 2). In contrast, when D14307 was used as the 3′ primer and B7493 was the 5′ primer, a band of the expected (1.1-kb) size was amplified in all O19 strains but in none of the non-O19 strains (Fig. 2). These results suggest that the downstream D14307 binding site of gyrB is important in differentiating O19 from non-O19 strains by RAPD PCR.

FIG. 2.

PCR of 12 C. jejuni isolates using random primer D14307 and primers specific for gyrB. O19 isolates (lanes 1 to 6) and non-O19 isolates (lanes 8 to 13) from patients with GBS (lanes 1 to 3 and 8 to 10) or diarrhea (lanes 4 to 6 and 11 to 13) were used. (A) PCR using D14307 (forward) and specific primer A8683 (reverse). (B) PCR using specific primer B7493 (forward) and D14307 (reverse). Lanes 7 and 14 are the no-DNA control. Lane M contains the 1-kb ladder markers. The positions (in kilobases) of molecular size markers are indicated to the left of the gel.

Degenerate PCR analysis.

To determine the exact sequences of both the upstream and downstream D14307 binding regions within gyrB, we first designed degenerate PCR primers that flank the expected sites. Since all fragments amplified by RAPD PCR were originally extended from primer D14307, the binding sites would not be expected to reflect exact sequences if D14307 mismatched the template DNA. Paired degenerate and nondegenerate primers were used to amplify a DNA fragment that flanked each region (Fig. 1). A band of the expected size (0.3 or 0.5 kb for the targeted upstream or downstream fragments, respectively) in each degenerate PCR was detected in each of the two O19 strains (D450 and D3083) tested (data not shown). Each band was extracted from an agarose gel, and sequences were analyzed directly with the specific primers. Next, new specific primers adjacent to the degenerate primer binding region were synthesized. The two pairs of specific primers also amplified bands of the expected size in each of two O19 (D450 and D3083) and non-O19 (84-196 and 85-1) strains (data not shown). In total, we sequenced 2,055 nucleotides within gyrB, using the above combination of amplicons.

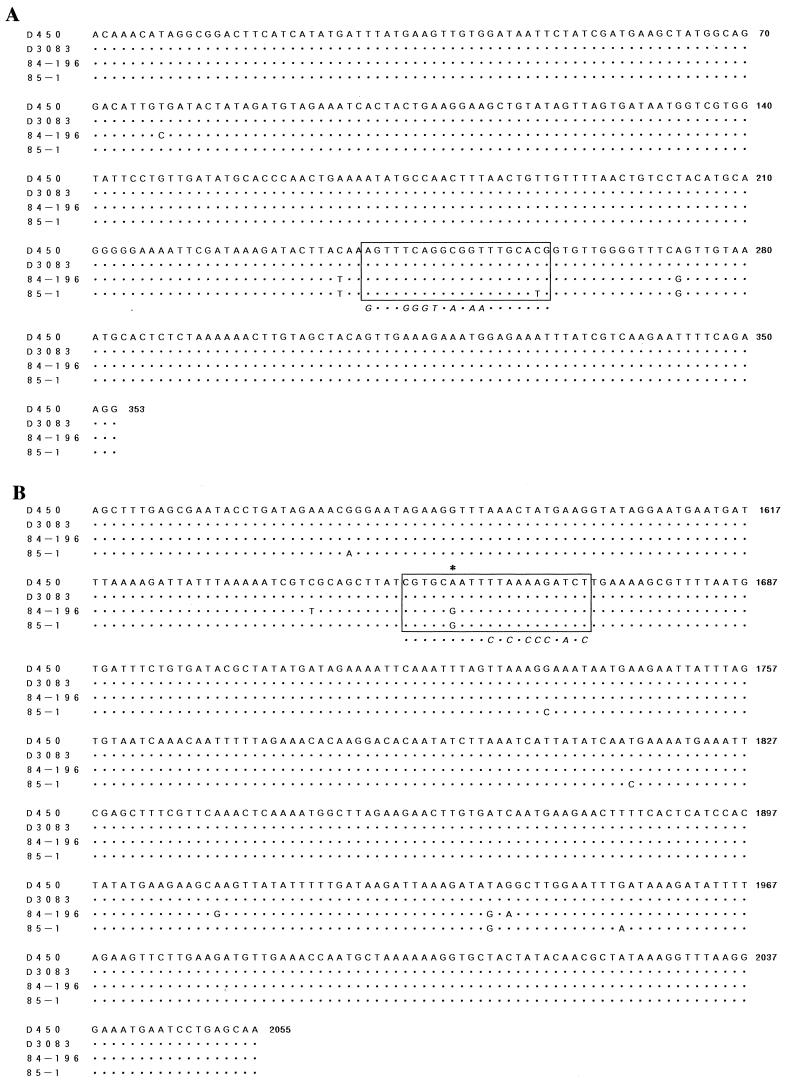

Sequence analysis of the O19-specific fragment.

Comparison of the sequences of the four PCR amplicons for the two regions showed only small differences among the O19 and non-O19 strains tested (Fig. 3). When the sequences of D14307 and each binding site in the O19 strains were compared, 7 or 8 of 20 nucleotides at the upstream or downstream binding site, respectively, were mismatched. Nevertheless, most nucleotides at the 3′ end of each binding site were completely matched (Fig. 3). In the upstream gyrB D14307 binding site, the sequences of two O19 strains and one of the two non-O19 strains were identical, except for a single nucleotide difference (C or T) 2 bp upstream of the 3′ terminus of the binding region in strain 85-1 (Fig. 3). Similarly, in the downstream gyrB D14307 binding site, a single nucleotide polymorphism (A or G) 6 bp upstream of the 3′ terminus of the binding region was found in the O19 and non-O19 strains tested (Fig. 3). The results of the RAPD PCR and the PCR using the combination of a random primer and a specific primer with the non-O19 strains suggest that D14307 is not able to recognize the downstream binding site present in O19 strains due to a single nucleotide difference in the template DNA.

FIG. 3.

Comparison of the nucleotide sequences of gyrB among O19 (D450 and D3083) and non-O19 strains (84-196 and 85-1). Fragments initially were amplified by degenerate PCR (Fig. 1), then new primers (AN263 and C3648) specific to each region were designed, and specific PCR was then performed for further sequencing. Fragments of 353 bp near the upstream end (A) and of 508 bp near the downstream end (B) of gyrB were amplified in all strains tested. Nucleotides identical to those in D450 are indicated by dots. Each D14307 binding site is enclosed in a box. The sequence of random primer D14307 is shown in italics under the box indicating its binding site. PCR primers with the 3′ end mismatched in relation to the position indicated with an asterisk were designed to differentiate O19 strains from non-O19 strains.

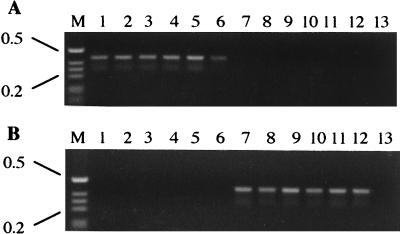

PCR specific for O19 or non-O19 strains.

Because this single nucleotide difference at the downstream D14307 binding region in gyrB discriminated between O19 and non-O19 strains, we adopted a PCR method that was developed to directly screen for site-directed genomic polymorphisms (15, 19). New downstream binding site primers were designed so that the only difference between the O19- and non-O19-specific primers was the 3′-terminal nucleotide (Table 2). To begin, we used two O19 and two non-O19 strains to optimize PCR conditions and programs. When short 5′ and 3′ primers or long 5′ primers were used as specific primers, either no PCR product was amplified or the O19 and non-O19 strains were not completely differentiated, even with variation in annealing temperatures. With other test conditions, the groups were distinguishable, but different PCR programs had to be run for each group (data not shown). In contrast, when the long O19-specific primer oligonucleotide (C3650) was used as the 3′ primer and C3647 was used as the 5′ primer and annealed at 48°C, the O19-specific band was detected. However, a faint band also was amplified for the non-O19 strains. By increasing the annealing temperature to 50°C, the band was not detected in the non-O19 strain, but the O19-specific band had become faint. However, when the long non-O19 specific oligonucleotide (C3652) was used as a 3′ primer, specific bands were detected at both annealing temperatures and no O19 band was amplified. We next combined two PCR programs to eliminate nonspecific amplification and to amplify the specific band. The new PCR program was performed as follows: 10 cycles, with 1 cycle consisting of 1 min at 94°C, 1 min at 50°C, and 1 min at 72°C, followed by 30 cycles, with 1 cycle consisting of 1 min at 94°C, 1 min at 48°C, and 1 min at 72°C. Using this single program, O19 and non-O19 strains were clearly differentiated by each specific primer (C3650 or C3652, respectively) in conjunction with C3647 (Fig. 4). A total of 42 strains, including 18 O19 strains and 24 non-O19 strains, were examined under the PCR conditions determined to be optimal. All O19 and non-O19 strains tested were distinguished, and there was no nonspecific amplification (Table 1). Each 3′ primer specific for the O19 or non-O19 strains amplified two bands, even though they were specific to each group of strains. Although one band (0.4 kb) was of the expected size, the second (0.3-kb) band was unexpected based on the locations of each specific primer (C3650 or C3652) in conjunction with C3647. We thus hypothesized that another region highly homologous to the primer binding site might exist in gyrB. Further analysis demonstrated a sequence (5′-TTATTTAAAAGATGAAAA-3′) that was highly homologous to the downstream binding site (5′-AATTTTAAAAGATCTTGA-3′) and was 123 bp upstream of it. These data indicate that in conjunction with C3647, the specific primers used also bound to this second genomic sequence, yielding the second (0.3-kb) band.

FIG. 4.

Successful PCR discrimination between O19 and non-O19 strains using O19 (A) or non-O19 (B) specific primers to gyrB. O19 isolates (lanes 1 to 6) and non-O19 isolates (lanes 7 to 12) from patients with GBS (lanes 1 to 3 and 7 to 9) or enteritis (diarrhea alone) (lanes 4 to 6 and 10 to 12) were used. Strain designations for the lanes are as follows: lane 1, D450 (O19); lane 2, 84-158 (O19); lane 3, OH4382 (O19); lane 4, D3083 (O19); lane 5, D3180 (O19); lane 6, D3145 (O19); lane 7, 84-196 (O2); lane 8, 84-197 (O8, O17); lane 9, 86-381 (O2); lane 10, 84-194 (O16, O50); lane 11, 85-1 (O1); lane 12, 81116 (O6). Lane 13 is the no-DNA control. Lane M contains the 1-kb ladder markers. The positions (in kilobases) of molecular size markers are indicated to the left of the gel.

DISCUSSION

This study was initiated to search for genetic differences between O19 and non-O19 strains. In a previous study (7), we demonstrated that all O19 strains tested were closely related to one another and we identified O19-specific bands by RAPD analysis. Thus, RAPD analysis (37) is a useful tool for scanning the entire genome to look for differences between strains of C. jejuni (10, 20) as reported in other bacterial pathogens (6, 36).

In this study, we successfully extracted, cloned, and sequenced one O19-specific band that shows significant homology to gyrB in H. pylori (33). Because gyrB is essential for bacterial viability (34), we sought to determine whether the random primer used in this study (D14307) was able to bind to gyrB in non-O19 strains. The fact that D14307 was able to recognize the upstream binding site but not the downstream site within gyrB in some non-O19 strains suggests that the D14307 downstream binding sites may be important in differentiating O19 from non-O19 strains. Next, gyrB regions were amplified by degenerate PCR to allow sequence analysis of each D14307 binding site. In total, we determined about 90% of the overall sequence (2,055 bp) of gyrB in C. jejuni compared to 2,319 bp of gyrB in H. pylori 26695 (33). Sequence analysis revealed that both nucleotide and amino acid sequences were highly conserved among the O19 and non-O19 strains tested. The fact that the sequences of O19 strains D450 and D3083 were identical even though the strains were obtained from different clinical settings and had different Lior serotypes is consistent with the close genetic relationship among O19 strains previously postulated (7). In contrast, non-O19 strains 84-196 and 85-1 had small differences at the nucleotide level, which is consistent with the known high degree of genetic diversity in C. jejuni (16, 24). However, nearly all the differences in nucleotide sequences were synonymous.

When the sequences in the random primer D14307 and both binding sites in O19 strains were compared, several nucleotide mismatches were found. The fact that several nucleotides toward the 3′ end of D14307 and each binding site were completely matched was apparently sufficient for initiation of PCR despite the mismatches at each 5′ end. The fact that the difference between O19 and non-O19 strains in the downstream D14307 binding region consists of a single polymorphism near the 3′ terminus indicates that this single difference, in the context of the numerous mismatches, was sufficient to prevent annealing to the template.

Although O19 and non-O19 strains are distinguishable by RAPD PCR (12), a PCR method using specific primers is more desirable for maximizing accuracy of diagnosis. Since efficient PCR amplification requires a primer whose 3′-terminal nucleotide is complementary to the target sequence (38), we adopted a PCR method using 3′-end mismatched primers to differentiate the strains. Specific PCR conditions, including reagents, annealing temperature, and primer length, were optimized, leading to a method specific for differentiating O19 and non-O19 strains that can be performed under identical conditions and that will facilitate rapid laboratory diagnosis. Modifications in the PCR reagents, such as decreasing the deoxynucleoside triphosphate or magnesium level, which have been reported to improve discrimination (15), were not necessary. PCRs using two different sets of primers are advantageous by yielding one positive and one negative signal regardless of the allele. The reproducible results of the screening test using 42 strains from different parts of the world suggest the broad utility of these genotypic methods, although more-exhaustive studies will be needed to completely define the method’s accuracy. The constancy in genotypes of O19 strains at this single locus as well as our previous RAPD and RFLP results (7) contrasts with reported phenotypic differences in lipopolysaccharide structure (29, 30). Use of this PCR method, as opposed to RAPD PCR, which may be difficult to standardize, or serotyping, which is not widely available, should make detection of O19 strains available to most clinical microbiology laboratories.

DNA gyrase consists of two A and two B subunits which are encoded by the genes gyrA and gyrB, respectively (34). High-level resistance of Campylobacter spp. to the fluoroquinolones and nalidixic acid, which are DNA gyrase inhibitors, has been reported (12). Mutations conferring quinolone resistance in E. coli were found in both gyrA and gyrB (39, 40). However, alterations in GyrA rather than GyrB are associated with high-level resistance in Campylobacter spp. (12, 32). Similarly, for C. jejuni strains, gyrA mutations causing changes at Ala-70, Thr-86, and Asp-90 in the protein resulted in nalidixic acid resistance (35). In the present study, the nucleotide difference found in the 3′-primer binding region did not affect the amino acid sequence and does not determine the quinolone susceptibility phenotype. Thus, the differences we found between O19 and non-O19 strains are independent of fluoroquinolone resistance.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported in part by a Center grant from the National Cancer Institute (CA68485), grant K08-NS01709 from the National Institutes of Health (NINDS), the Medical Research Service of the Department of Veterans Affairs, and by the Iris and Homer Akers Fellowship in Infectious Diseases (to N.M.).

We thank Richard Hughes, Jeremy Rees, and Manfred Kist for providing strains.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akopyanz N, Bukanov N O, Westblom T U, Kresovich S, Berg D E. DNA diversity among clinical isolates of Helicobacter pylori detected by PCR-based RAPD fingerprinting. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:5137–5142. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.19.5137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allos B M, Blaser M J. Potential role of lipopolysaccharides of Campylobacter jejuni in the development of Guillain-Barré syndrome. J Endotoxin Res. 1995;2:237–238. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allos B M, Lippy F T, Carlsen A, Washburn R G, Blaser M J. Campylobacter jejuni strains from patients with Guillain Barré syndrome. Emerg Infect Dis. 1998;4:263–268. doi: 10.3201/eid0402.980213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aspinall G O, Fujimoto S, McDonald A G, Pang H, Kurjanczyk L A, Penner J L. Lipopolysaccharides from Campylobacter jejuni associated with Guillain-Barré syndrome mimic human gangliosides in structure. Infect Immun. 1994;62:2122–2125. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.5.2122-2125.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Enders U, Karch H, Toyka K V, Heeseman J, Hartung H P. Campylobacter jejuni and Guillain-Barré syndrome. Ann Neurol. 1994;35:248–249. doi: 10.1002/ana.410350228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fadl A A, Nguyen A V, Khan M I. Analysis of Salmonella enteritidis isolates by arbitrarily primed PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:987–989. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.4.987-989.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fujimoto S, Allos B M, Misawa N, Patton C M, Blaser M J. Restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis and random amplified polymorphic DNA analysis of Campylobacter jejuni strains isolated from patients with Guillain-Barré syndrome. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:1105–1108. doi: 10.1086/516522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fujimoto S, Yuki N, Itoh T, Amako K. Specific serotypes of Campylobacter jejuni associated with Guillain-Barré syndrome. J Infect Dis. 1992;165:183. doi: 10.1093/infdis/165.1.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ge Z, Taylor D E. Rapid polymerase chain reaction screening of Helicobacter pylori chromosomal point mutations. Helicobacter. 1997;2:127–131. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.1997.tb00073.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hilton A C, Mortiboy D, Banks J G, Penn C W. RAPD analysis of environmental, food and clinical isolates of Campylobacter spp. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 1997;18:119–124. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1997.tb01036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hughes, R. A. C., and J. H. Rees. 1997. Clinical and epidemiologic features of Guillain-Barré syndrome. J. Infect. Dis. 176(Suppl. 2):S92–S98. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Husmann M, Feddersen A, Steitz A, Freytag C, Bhakdi S. Simultaneous identification of campylobacters and prediction of quinolone resistance by comparative sequence analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2398–2400. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.9.2398-2400.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jacob B C, Hazenberg M P, van Doorn P A, Endtz H, van der Meché F G A. Cross-reactive antibodies against gangliosides and Campylobacter jejuni lipopolysaccharides in patients with Guillain-Barré syndrome or Miller Fisher Syndrome. J Infect Dis. 1997;175:729–733. doi: 10.1093/infdis/175.3.729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kuroki S, Saida T, Nukina M, Haruta T, Yoshioka M, Kobayashi Y, Nakanishi H. Campylobacter jejuni strains from patients with Guillain-Barré syndrome belong mostly to Penner serogroup 19 and contain β-N-acetylglucosamine residues. Ann Neurol. 1993;33:243–247. doi: 10.1002/ana.410330304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kwok S, Kellogg D E, McKinney N, Spasic D, Goda L, Levenson C, Sninsky J J. Effects of primer-template mismatches on the polymerase chain reaction: human immunodeficiency virus type 1 model studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:999–1005. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.4.999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lam K M, Yamamoto R, DaMassa A J. DNA diversity among isolates of Campylobacter jejuni detected by PCR-based RAPD fingerprinting. Vet Microbiol. 1995;45:269–274. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(94)00133-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lastovica, A. J., E. A. Goddard, and A. C. Argent. 1997. Guillain-Barré syndrome in South Africa associated with Campylobacter jejuni O:41 strains. J. Infect. Dis. 176(Suppl. 2):S139–S143. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Lior H, Woodward D L, Edgar J A, Laroche L J, Gill P. Serotyping of Campylobacter jejuni by slide agglutination based on heat-labile antigenic factors. J Clin Microbiol. 1982;15:761–768. doi: 10.1128/jcm.15.5.761-768.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Major J J G. A rapid PCR method of screening for small mutations. BioTechniques. 1992;12:40–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mazurier S, van de Giessen A, Heuvelman K, Wernars K. RAPD analysis of Campylobacter isolates: DNA fingerprinting without the need to purify DNA. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1992;14:260–262. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765x.1992.tb00700.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mishu B, Blaser M J. The role of Campylobacter jejuni infection in the initiation of Guillain-Barré syndrome. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;17:104–108. doi: 10.1093/clinids/17.1.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moran A P, O’Malley D T. Potential role of lipopolysaccharides of Campylobacter jejuni in the development of Guillain-Barré syndrome. J Endotoxin Res. 1995;2:233–235. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nachamkin I, Allos B M, Ho T. Campylobacter species and Guillain-Barré syndrome. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1998;11:555–567. doi: 10.1128/cmr.11.3.555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nachamkin I, Bohachick K, Patton C M. Flagellin gene typing of Campylobacter jejuni by restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:1531–1536. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.6.1531-1536.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nakanishi H, Nukina M, Sakazaki R. Proceedings of the Symposium on the 100th Anniversary of Japanese Society of Veterinary Medicine: Its Advance and View of Research. Tokyo, Japan: Japanese Society of Veterinary Medicine; 1985. Serogroups of Campylobacter jejuni and C. coli; pp. 70–73. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patton C M, Nicholson M A, Ostroff S M, Ries A A, Wachsmuth I K, Tauxe R V. Common somatic O and heat-labile serotypes among Campylobacter strains from sporadic infections in the United States. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:1525–1530. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.6.1525-1530.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Penner J L, Hennessy J N. Passive hemagglutination technique for serotyping Campylobacter fetus subsp. jejuni on the basis of soluble heat-stable antigens. J Clin Microbiol. 1980;12:732–737. doi: 10.1128/jcm.12.6.732-737.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rees J H, Soudain S E, Gregson N A, Hughes R A. Campylobacter jejuni infection and Guillain-Barré syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1374–1379. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199511233332102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saida, T., S. Kuroki, Q. Hao, M. Nishimura, M. Nukina, and H. Obayashi. 1997. Campylobacter jejuni isolates from Japanese patients with Guillain-Barré syndrome. J. Infect. Dis. 176(Suppl. 2):S129–S134. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Salloway S, Mermel L A, Seamans M, Aspinall G O, Nam Shin J E, Kurjanczyk L A, Penner J L. Miller-Fisher syndrome associated with Campylobacter jejuni bearing lipopolysaccharide molecules that mimic human ganglioside GD3. Infect Immun. 1996;64:2945–2949. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.8.2945-2949.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sambrook J E, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taylor D E, Chau S-S. Cloning and nucleotide sequencing of the gyrA gene from Campylobacter fetus subsp. fetus ATCC 27374 and characterization of ciprofloxacin-resistant laboratory and clinical isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:665–671. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.3.665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tomb J-F, White O, Kerlavage A R, Clayton R A, Sutton G G, Fleischmann R D, Ketchum K A, Klenk H P, Gill S, Dougherty B A, Nelson K, Quackenbush J, Zhou L, Kirkness E F, Peterson S, Loftus B, Richardson D, Dodson R, Khalak H G, Glodek A, McKenney K, Fitzgerald L M, Lee N, Adams M D, Venter J C. The complete genome sequence of the gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nature. 1997;388:539–547. doi: 10.1038/41483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang J C. DNA topoisomerases. Annu Rev Biochem. 1985;54:665–697. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.54.070185.003313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang Y, Huang W M, Taylor D E. Cloning and nucleotide sequence of the Campylobacter jejuni gyrA gene and characterization of quinolone resistance mutations. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:457–463. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.3.457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Welsh J, McClelland M. Fingerprinting genomes using PCR with arbitrary primers. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:7213–7218. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.24.7213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Williams J G K, Hanafey M K, Rafalski J A, Tingey S V. Genetic analysis using random amplified polymorphic DNA marker. Methods Enzymol. 1993;218:704–740. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(93)18053-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu D Y, Ugozzoli L, Pal B K, Wallace R B. Allele-specific enzymatic amplification of β-globin genomic DNA for diagnosis of sickle cell anemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:2725–2760. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.8.2757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yoshida H, Bogaki M, Nakamura M, Nakamura S. Quinolone resistance-determining region in the DNA gyrase gyrA gene of Escherichia coli. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990;34:1271–1272. doi: 10.1128/aac.34.6.1271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yoshida H, Bogaki M, Nakamura M, Yamanaka L M, Namamura S. Quinolone resistance-determining region in the DNA gyrase gyrB gene of Escherichia coli. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991;35:1647–1650. doi: 10.1128/aac.35.8.1647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yuki N, Handa S, Taki T E. Cross-reactive antigen between nervous tissue and a bacterium elicits Guillain-Barré syndrome: molecular mimicry between ganglioside GM1 and lipopolysaccharide from Penner serotype 19 of Campylobacter jejuni. Biomed Res. 1992;13:451–453. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yuki N, Taki T, Inagaki F, Kasama T, Takahashi M, Saito K, Handa S, Miyatake T. A bacterium lipopolysaccharide that elicits Guillain-Barré syndrome has a GM1 ganglioside-like structure. J Exp Med. 1993;178:1771–1775. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.5.1771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yuki N, Taki T, Takahashi M, Saito K, Tai T, Miyatake T, Handa S. Penner serotype 4 of Campylobacter jejuni has a lipopolysaccharide that bears a GM1 ganglioside epitope as well as one that bears a GD1a epitope. Infect Immun. 1994;62:2101–2103. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.5.2101-2103.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]