Abstract

Objective:

Eating disorders (EDs) and depression impact youth at alarming rates, yet most adolescents do not access support. Single-session interventions (SSIs) can reach youth in need. This pilot examines the acceptability and utility of an SSI designed to help adolescents improve functionality appreciation (a component of body neutrality) by focusing on valuing one’s body based on the functions it performs, regardless of appearance satisfaction.

Method:

Pre- to post-intervention data were collected, and within-group effect sizes and 95% confidence intervals were computed, to evaluate the immediate effects of the SSI on hopelessness, functionality appreciation, and body dissatisfaction. Patterns of use, demographics, program feedback, and responses from within the SSI were collected.

Results:

The SSI and all questionnaires were completed by 75 adolescents (ages 13–17, 74.70% White/Caucasian, 48.00% woman/girl) who reported elevated body image and mood problems. Analyses detected significant pre-post improvements in hopelessness (dav = 0.60, 95% CI 0.35, 0.84; dz = 0.77, 95% CI 0.51, 1.02), functionality appreciation (dav = 0.72, 95% CI 0.46, 0.97; dz = 0.94, 95% CI 0.67, 1.21), and body dissatisfaction (dav = 0.61, 95% CI 0.36, 0.86; dz = 0.76, 95% CI 0.50, 1.02). The SSI was rated as highly acceptable, with a mean overall score of 4.34/5 (SD = 0.54). Qualitative feedback suggested adolescents’ endorsement of body neutrality concepts, including functionality appreciation, as personally-relevant, helpful targets for intervention.

Discussion:

This evaluation supports the acceptability and preliminary effectiveness of the Project Body Neutrality SSI for adolescents with body image and mood concerns.

Keywords: Body neutrality, body dissatisfaction, single-session intervention, transdiagnostic risk factors, online self-help

Introduction

Rates of mental health concerns among youth have risen over the last decade (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2018) and especially alarming is the increase in depression and eating disorders (EDs). Rates of major depressive episodes among adolescents rose 52% from 2005 to 2017 (Twenge et al., 2019). From 2019 to 2020, the rate of individuals under 30 who received their first ED diagnosis increased by 15.3%, and this increased risk was greatest for youth aged 10–19 (Taquet et al., 2021). Notably, depression and EDs are highly comorbid, with 31.0% of adolescents with bulimia nervosa and 35.4% of adolescents with binge eating disorder experiencing depression (Swanson et al., 2011). On their own, depression and ED pathology adversely impact quality of life (Clark & Kirisci, 1996; de la Rie et al., 2007; Griffiths et al., 2017), and outcomes worsen when these conditions co-occur (Button et al., 2010; Hjern et al., 2006). Accordingly, support addressing both depression symptoms and eating difficulties is necessary. However, the treatment gap is enormous (Kazdin et al., 2017; Rice et al., 2017), with access to evidence-based care limited by shortages of mental healthcare providers along with myriad logistical and financial barriers (Thomas et al., 2009; Hoyt et al., 2018). Furthermore, even when individuals are successful in accessing care, evidence-based treatments only lead to symptom remission in 30–40% of patients (Fairburn et al., 2015; McIntosh et al., 2016; Wonderlich et al., 2014), indicating the importance of ED prevention. Options for support—ideally, supports equipped to prevent and reduce depression and eating difficulties simultaneously—must expand beyond traditional psychotherapy in order to become more scalable, accessible, and acceptable (Kazdin, 2019).

Digital Interventions and the Single-Session Approach

Given the failure of traditional in-person support to reach many youth in need, digital, self-help interventions may offer an avenue toward increasing youth mental healthcare access (Lehtimaki et al., 2021). With most adolescents owning smartphones (Anderson & Jiang, 2018) and seeking mental health information online (Bauer et al. 2016; Gay et al. 2016), internet-embedded tools present common-sense opportunities to offer in-the-moment mental health support to youth. Although internet- and app-based mental health supports have proliferated in recent years (Palmer & Burrows, 2021; Torous & Roberts, 2017), most lack key evidence-based intervention components (Wasil et al., 2019). Additionally, most existing internet-based tools require long-term engagement—but in reality, 96% of users disengage from mental health apps within two weeks (Baumel et al., 2019). These realities create a need for digital mental health interventions that include evidence-based content and optimize the likelihood that even brief usage can yield sustainable, positive change (Schleider et al., 2020a).

Digital single-session interventions (SSIs) are poised to address these needs directly. SSIs are “structured programs that intentionally involve just one visit or encounter with a clinic, provider, or program” (Schleider et al. 2020a). To optimize odds of sustainable mental health improvements following a single session, SSIs target the proximal outcomes and core, theory-driven aspects of longer interventions (Schleider & Beidas, 2022). Research has demonstrated that digital, self-guided SSIs can yield sustained mental health improvements in young people at three-month to nine-month follow-up (Schleider et al., 2022; Schleider & Weisz, 2018). One trial of 2,452 adolescents found that two digital, self-guided SSIs significantly reduced depression symptoms, anxiety, and restrictive eating compared to a supportive-therapy control (Schleider et al., 2022). Furthemore, a meta-analysis of 50 randomized trials found that SSIs significantly reduced youth mental health concerns compared to controls and that there is no significant difference in the effects produced by therapist-administered versus self-administered SSIs (Schleider & Weisz, 2017), suggesting self-guided, digital SSIs as an especially scalable path to disseminating evidence-based, effective mental health supports.

While sparse, research on SSIs for EDs has begun. A meta-analysis found a large effect on SSIs targeting ED symptoms and disorders, however, this effect was not statistically significant given that only three SSIs met the meta-analysis inclusion criteria (g = 1.05; 95% CI: −0.33, 2.93) (Schleider & Weisz, 2017). To date, most research on SSIs for EDs has focused on prevention, with the development of SSIs that target known ED risk and protective factors related to body image. For example, three 5-minute long techniques incorporating strategies to reduce body dissatisfaction—cognitive dissonance, acceptance, and distraction—all significantly improved weight and appearance satisfaction among female undergraduates compared to a control condition, although there was no follow-up (Wade et al., 2009). Additionally, single-session imagery rescripting interventions have been used to strengthen ED protective factors in college-age females. In one study, a 5-minute, online imagery rescripting intervention significantly increased body image acceptance compared to a brief cognitive dissonance intervention and increased self-compassion compared to a control, at one-week follow-up (Pennesi & Wade, 2018). In another study, 10-minute online interventions including a single-session body imagery rescripting intervention, a general imagery rescripting intervention, and a psychoeducational intervention each led to significant improvements in body acceptance and global ED psychopathology compared to a control condition, at one-week follow-up (Zhou et al., 2020). A longer, 90-minute body image SSI delivered by teachers to girls and boys in secondary schools demonstrated small-to-medium improvements in body image and disordered eating outcomes at post-intervention, but some of these effects were only significant for girls and they were not maintained at 4–9.5 week follow-up (Diedrichs et al., 2015). Overall, the existing research on SSIs for EDs demonstrates their promising short-term effects, warranting further study.

Utility of Targeting Both Depression and EDs

Since depression and EDs share risk factors (Goldschmidt et al., 2016; Stice et al., 2017), interventions have the potential to prevent or treat both concurrently. Of the risk factors shared between depression and EDs, body dissatisfaction has been described as one of the most evidence-based and potent (Jacobi & Fittig, 2010; Becker et al., 2014). One pathway whereby body dissatisfaction can lead to EDs is through increased dietary restraint and negative affect (i.e., the dual pathway model, Stice, 2001; Stice et al., 1996). Body dissatisfaction also confers risk for depressed mood (Paxton et al., 2006; Stice & Bearman, 2001). Reducing body dissatisfaction may therefore reduce core symptomatology of both EDs and depression, over time.

In fact, there is evidence that interventions for EDs can have significant effects on depression, even when they do not target depression directly. A systematic review of 26 ED prevention and early intervention trials found that 42% significantly reduced depression symptoms, in addition to eating pathology (Rodgers & Paxton, 2014). Additionally, a meta-analysis of 13 RCTs found that interventions designed to reduce adolescent body dissatisfaction significantly reduced depression symptoms, as well (Ahuvia et al., 2022). These studies suggest that interventions mitigating ED pathology can reduce depression symptoms, even when depression is not intentionally targeted.

Furthermore, risk for EDs may be lessened when depression is alleviated. Depression-focused interventions have led to small decreases in some ED symptoms. For example, two depression-focused SSIs (one teaching behavioral activation, one teaching that traits and symptoms are malleable) both led to significant three-month reductions in adolescent depression severity (as intended) and restrictive eating (not directly targeted) (Schleider et al., 2022). While the potential of depression-focused interventions to reduce ED symptoms warrants further study, interventions that intentionally target transdiagnostic risk factors for depression and EDs may carry considerable utility.

Reductions in both ED and depression symptoms could be improved by designing programs that address their shared risk factors (Ahuvia et al., 2022; Puccio et al., 2016; Becker et al., 2014). Some existing interventions already target shared risk factors. For example, capitalizing on the scalability that can come from self-guided, digital programs, Stice and colleagues (2017) evaluated the Internet-based eBody Project which is designed to decrease body dissatisfaction, ED symptoms, and negative affect among female college students by reducing thin-body ideal internalization, based on the dual pathway model. The eBody Project produced significant reductions in all four of these outcomes compared to an educational video control, but nearly half of the participants did not complete all six, 40-minute modules (Stice et al., 2017). A self-guided, digital SSI that deliberately targets shared risk factors for depression and EDs may optimize impacts on both sets of problems and produce meaningful change from the brief engagement. One approach could involve developing a digital SSI that targets body dissatisfaction.

Functionality Appreciation and Body Neutrality

A novel approach to reducing body dissatisfaction is increasing functionality appreciation. Functionality appreciation entails appreciating the body for everything it is capable of doing, including functions related to internal processes, physical capacities, senses and sensations, creativity, communication with others, and self-care (Alleva et al., 2017; Alleva & Tylka, 2021). Item pool visualization research on body image scales suggests that functionality appreciation is a distinct body image construct (Swami et al., 2020) and experimental studies demonstrate that functionality appreciation improves multiple body image outcomes (e.g., physical functionality satisfaction, body satisfaction, internalized weight stigma) (Alleva et al., 2015; Mulgrew et al., 2017; Mulgrew et al., 2019; Stern & Engeln, 2018; Dunaev et al., 2018). For example, the Expand Your Horizon program is a three-session, online writing intervention that prompts participants to focus on their body functionality rather than their physical appearance (Alleva et al., 2015). Compared to a control group, women with negative body image who participated in the Expand Your Horizon program experienced improvements in functionality satisfaction, immediately post-intervention and at one-month follow-up (Alleva et al., 2018). This literature suggests that functionality appreciation is modifiable through intervention and that these changes can lead to improvements in body image, including body satisfaction (Alleva & Tylka, 2021). While additional experimental and longitudinal research is needed to expand on the relationship between functionality appreciation and other body image constructs as well as identify the mechanisms behind the body image improvements spurred by functionality appreciation interventions, the four theories that incorporate body functionality—body conceptualization theory (Franzoi, 1995), objectification theory (Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997), the acceptance model of intuitive eating (Avalos & Tylka, 2006), and the developmental theory of embodiment (Piran, 2017; Piran & Teall, 2012)—share the sentiment that there are benefits associated with focusing on functionality appreciation and consequences associated with over-valuing physical appearance (Alleva & Tylka, 2021).

Another adaptive body image construct that incorporates these principles is body neutrality. Anne Poirier, a body image coach, is credited with popularizing the term in the mid-2010s, and it has since gathered mainstream media attention (Cowles, 2022; Khan, 2022; Haupt, 2022). At this point in 2023, there is no published empirical research attempting to validate a definition of body neutrality, and there is some variation in the definitions proliferating in the media. In her book The Body Joyful and in multiple interviews, Poirier has explained that “body neutrality prioritizes the body’s function, and what the body can do, rather than its appearance. You don’t have to love or hate it. You can feel neutral towards it . . . You’ll consider the way you look as one small part of who you are, and accept that your weight doesn’t define your worth” (Cowles, 2022; Khan, 2022; Haupt, 2022). Other definitions of body neutrality, such as the following description provided by a leading Australian ED organization, emphasize that body neutrality “shifts the focus from positivity and acceptance and into the idea that a person can exist in their body without thinking too much about how it looks . . . The focus is instead on functionality and looking beyond physical appearance as the sole indicator of worth” (The Butterfly Foundation, 2023). While consideration of all aspects of these definitions of body neutrality is outside the scope of this paper, a clear commonality across many proposed definitions is that body neutrality incorporates functionality appreciation as a central component. An additional important element of body neutrality highlighted by these definitions is its contrast with body positivity.

Unlike body positivity, which encourages individuals to love the way their body looks, the functionality appreciation aspect of body neutrality involves encouraging individuals to value their body based on the functions it performs, even if they are not always satisfied with its physical appearance. As such, body neutrality is an approach that diverges from many traditional positive body image constructs that have been researched and implemented in ED prevention and treatment since Cash and Pruzinsky (2002) initiated this direction (Tylka & Wood-Barcalow, 2015). Following the recognition that strengths-based approaches targeting the presence of positive body image, rather than the absence of body dissatisfaction alone, may be important for ED recovery (Cook-Cottone, 2015; Koller et al., 2019; Linardon et al., 2022), interventions designed to enhance positive body image have been developed (e.g., Beilharz et al., 2021; Cassone et al., 2016; Fitzsimmons-Craft et al., 2022). However, targeting body positivity alone might not align with patients’ and providers’ needs, with commentaries and qualitative studies suggesting a desire for approaches that integrate body neutrality, not just positivity (Perry et al., 2019; Hartman-Munick et al., 2021).

Mainstream media attention to body neutrality demonstrates its cultural significance as an alternative to body positivity (Cowles, 2022; Khan, 2022; Haupt, 2022). Although body positivity is adaptive for some (Rodgers et al., 2022), it has faced criticism as a movement for deviating from its roots in uplifting marginalized communities and instead centering white cisgender women who are relatively thin and able-bodied (Miller, 2016; Darwin & Miller, 2021; Cwynar-Horta, 2016). Moreover, body positivity typically emphasizes loving one’s physical appearance regardless of its adherence to socially constructed body ideals (Cohen et al., 2019), but this appearance-centered focus can be counterproductive. Body positivity messages may reinforce the myth that one’s worth is based on their appearance, which can undermine agency and self-esteem (Legault & Sago, 2022; Rodgers et al., 2022; Lazuka et al., 2020). This can have harmful side-effects for those who feel unable to love how their body looks, such as individuals experiencing gender dysphoria (McGuire et al., 2016).

Body image experts have suggested that a body neutrality mindset can be adopted with multiple strategies, including increasing functionality appreciation by focusing on what one’s body can do (Cowles, 2022; Khan, 2022; Haupt, 2022; Jordan, 2023). Strategies also include stopping unwanted diet and body-oriented conversations (Khan, 2022; Haupt, 2022), reframing the purpose behind exercise and movement (Cowles, 2022; Haupt, 2022), replacing automatic negative self-talk with body neutral statements (Haupt, 2022; Jordan, 2023), and dismantling the binary that one’s body is good or bad (Khan, 2022; Jordan, 2023). We therefore conceptualize increasing functionality appreciation to be one strategy for embracing a body neutrality mindset and a central component of body neutrality definitions.

Present Study

This is the first evaluation of a new digital SSI designed to increase functionality appreciation, an important aspect of body neutrality, to reduce body dissatisfaction—a transdiagnostically-relevant risk factor connected to depression symptoms and eating difficulties (Becker et al., 2014). To our knowledge, this new digital SSI is a novel contribution to the field given that it is a) the first single-session digital program intentionally designed to improve body image and mood, and b) the first empirical investigation of an SSI designed to introduce the concept of body neutrality and improve functionality appreciation in users. Of note, we titled this SSI “Project Body Neutrality” because body neutrality, compared to functionality appreciation, is the term that explicitly contrasts body positivity and has received recognition in popular culture. Furthermore, framing the SSI using the culturally-relevant concept of body neutrality may optimize reach, uptake, engagement, and accessibility. This is a pilot study without follow-up, so we are not assessing long-term clinical outcomes. Rather, we are interested in the SSI’s immediate impact on proximal outcomes as well as user experiences. We hypothesize that Project Body Neutrality will be acceptable and feasible to deliver, and that adolescents who complete it will demonstrate significant improvements in hopelessness, functionality appreciation, and body dissatisfaction, which have been collectively linked to depression and EDs (Schleider et al., 2020; Becker et al., 2014; Alleva & Tylka, 2021). We will also gather the respondents’ perspectives on body positivity and body neutrality.

Methods

Ethical Considerations

This non-randomized, anonymous program evaluation was reviewed by the Stony Brook University IRB and deemed not human subjects research. The same determination has previously been made for similar study designs (e.g., Dobias et al., 2022). Parent permission was not required to participate. Our research team has led multiple randomized trials and evaluations in which parent permission was not required for youth to take part (i.e., parent permission requirements have been waived in consultation with University IRBs) (Schleider et al., 2022; Schleider et al., 2020b). This step was taken to minimize adolescents’ treatment access barriers, including discomfort with disclosing psychological distress to parents (as many parents are not aware of their children’s symptoms) (Wilson & Deanem 2012; Samargia et al., 2006; Cavazos-Rehg et al., 2020), and, in the case of anonymous program evaluations, to ensure that youth remain unidentifiable. Procedures and planned analyses were pre-registered on Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/t7gms).

Procedures

Respondents learned about Project Body Neutrality through an Instagram advertisement which led to a Qualtrics survey. Respondents completed a screening with the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2) (Kroenke et al., 2003), the Weight Concerns Scale (WCS) (Killen et al., 1994), and a question about their age. The language for the first item of the WCS was changed to reference “people” rather than “girls.” This evaluation was targeted to adolescents who self-identified as being between ages 13–17 and who reported non-zero mood problems (PHQ-2 ≥2) as well as body image concerns. Respondents who scored ≥47 on the WCS, endorsed weight being more important than most things in life or the most important thing in life on the WCS, and/or who endorsed being very afraid of or terrified of gaining three pounds on the WCS, were considered to have elevated weight and shape concerns (Fitzsimmons-Craft et al., 2022). The 13–17 age range was targeted as a peak age of onset for EDs is during the teenage years (Volpe et al., 2016). Those who did not self-identify as being 13–17 years-old, reported PHQ <2, or who did not have elevated body image concerns were shown a message directing them to other online single-session experiences available through our lab (Project YES; https://osf.io/e52p3), and they could still proceed with Project Body Neutrality if desired. Eligible adolescents progressed directly to the Project Body Neutrality pre-intervention questionnaires. The SSI itself and the post-SSI questionnaires followed. There was no target sample size since this was an open evaluation. Respondents did not receive compensation. There was no follow-up and we only examined outcomes that could plausibly change from pre- to post-intervention. Figure 1 depicts the hypothesized theory of change.

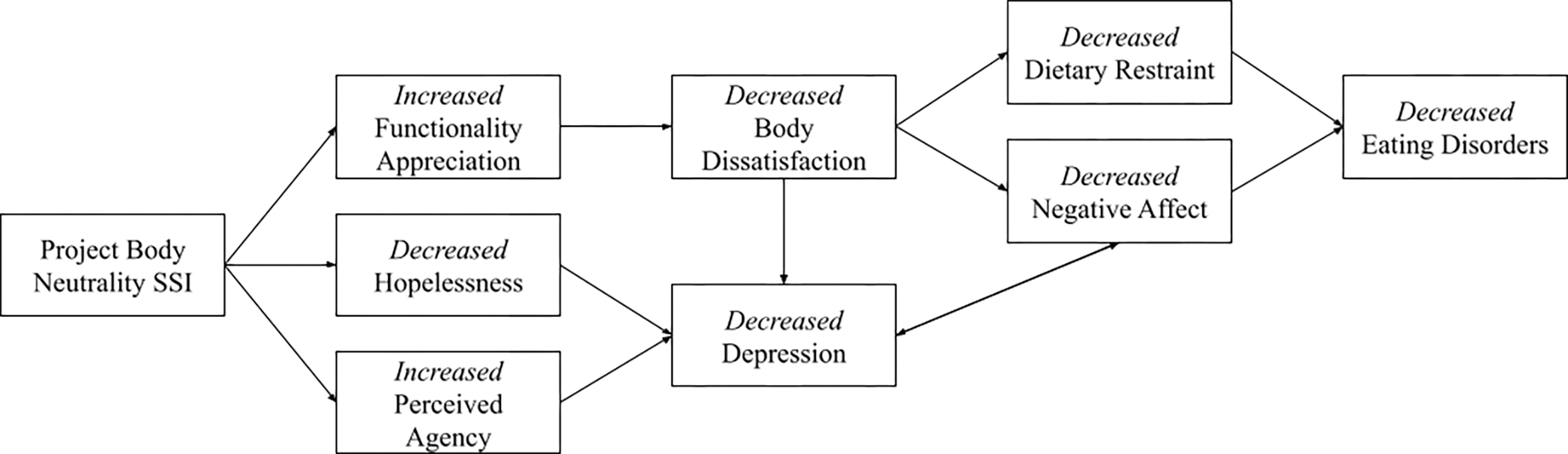

Figure 1: SSI Theory of Change.

Project Body Neutrality is designed to instill a “body neutrality” mindset through best practices in SSI design (Schleider et al., 2020a) in order to increase functionality appreciation and perceived agency as well as to decrease hopelessness. Increases in perceived agency and decreases in hopelessness caused by SSI use may lead to eventual decreases in depression (Schleider et al., 2019a). Increases in functionality appreciation improve body satisfaction (Alleva & Tylka, 2021), the inverse of body dissatisfaction. Decreases in body dissatisfaction lead to eventual reductions in ED symptoms through decreases in dietary restraint and negative affect (Stice, 2001; Stice et al., 1996). Reduction of body dissatisfaction also reduces the risk of depressive symptoms (Paxton et al. 2006; Stice & Bearman, 2001). Persistent negative affect is a core diagnostic component of major depressive disorder (American Psychiatric Association, 2022).

Intervention

Project Body Neutrality (Smith et al., 2022) is a digital, self-guided SSI that includes components based on best practices in SSI design (Schleider et al., 2020a). The full SSI can be viewed on Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/xspz9). It contains:

Self-reflection exercises, vignettes from fictional peers, and psychoeducation that support users in understanding why body positivity may be a difficult mindset for some individuals to obtain.

Additional self-reflection exercises and vignettes that present body neutrality as a well-rounded alternative to body positivity. Body neutrality is defined for users as “valuing your body based on what it does for you, even if you are not always happy with how it looks” (Smith et al., 2022).

Psychoeducation about the connection between body image and mood, emphasizing the benefits that obtaining a body neutrality mindset may have on mood.

Exercises that culminate in a user-generated list of activities that their body allows them to enjoy.

Exercises that help users to counter negative thoughts about their bodies by replacing them with body neutral statements, such as, “How I feel about my appearance does not determine my worth as a human being” (Smith et al., 2022).

Writing prompts where users provide advice based on body neutrality principles to fictional peers struggling with their body image.

An opportunity to contribute their advice or reflections anonymously to a lab-run social media campaign as a form of body neutrality advocacy.

Measures

Demographics

Respondents selected their age bracket, sex assigned at birth, gender identity, sexual orientation, race/ethnicity, and disability status. Demographic information was collected pre-intervention.

Hopelessness

The Beck Hopelessness Scale - 4 item version (Perczel Forintos et al., 2013) is a reliable, valid measure that asked respondents to rate four statements reflecting their sense of hopelessness from 0 (Absolutely Disagree) to 3 (Absolutely Agree). Total scores can range from 0 to 12, with higher scores indicating greater levels of hopelessness. The measure was presented pre- and immediately post- intervention. Internal consistency was α = 0.83 and α = 0.86 at pre- and post-SSI, respectively. We added language to the instructions preceding the measure in order to capture state characteristics, as has been done in other SSI trials (e.g., Schleider et al., 2022): “Please take a few moments to focus on yourself and what is going on in your life at this very moment. Once you have this “here and now” mindset, tell us how much you agree with these statements, based on how you are feeling right now.”

Functionality Appreciation

The Functionality Appreciation Scale (Alleva et al., 2017) is a reliable, valid measure of functionality appreciation, defined as “appreciating, respecting, and honouring the body for what it is capable of doing, and extending beyond mere awareness of body functionality.” Respondents were asked to rate seven statements from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 5 (Strongly Agree), where higher scores indicate greater appreciation for body functionality. Total sum-scores can range from 7 to 35. The measure was presented pre- and post- intervention. Internal consistency was α = 0.89 and α = 0.94 at pre- and post-SSI, respectively. The measure does not explicitly measure state functionality appreciation, so we added language to the instructions to orient respondents to the present: “Please share how you are feeling right now, at this moment.”

Body Dissatisfaction

The Body Shape Satisfaction Scale (Wang et al., 2019) is an abbreviated version of the Body Shape Satisfaction Scale (Pingitore et al., 1997) that assessed respondents’ dissatisfaction with various body parts. The ten items were rated from 1 (Very Dissatisfied) to 5 (Very Satisfied). Items were reverse-scored and summed for a total score, where higher scores indicate greater body dissatisfaction, and scores can range from 10 to 50. The measure was presented pre- and post- intervention. Internal consistency was α = 0.81 and α = 0.91 at pre- and post-SSI, respectively. In order to measure state body dissatisfaction, the words “right now” were added to the questionnaire: “How satisfied are you, right now, with your [item].”

Program Feedback

The Program Feedback Scale (PFS) (Schleider et al., 2019b) asked respondents to rate seven statements regarding intervention acceptability and feasibility; it also included open-ended items that invited respondents to share what they liked and/or would change about the intervention. The seven statements were rated from 1 (Really Disagree) to 5 (Really Agree). Total scores can range from 5 to 35, with higher scores indicating a more positive evaluation. The measure was presented at post-intervention only. Internal consistency across PFS items was α = 0.83.

Analytic Plan

Planned Analyses

SSI Usage and Feedback

We identified the number of respondents who (1) started Project Body Neutrality, (2) completed Project Body Neutrality (3) completed the PFS, and (4) completed all pre- and post-SSI measures. We also investigated the duration of use and dropout rates at pre-SSI, during the SSI, and post-SSI. For all respondents who completed the PFS, we computed overall and item-level means to assess SSI acceptability. A mean overall score of >3, across all items, reflected overall perceived SSI acceptability; a mean score >3 on any individual item reflected endorsement of that item (Schleider et al., 2020b). We also reviewed all the qualitative feedback provided.

SSI Effects on Proximal Outcomes

Pre- to post-intervention changes for hopelessness, functionality appreciation, and body dissatisfaction were evaluated by computing within-group effect sizes. Specifically, we used the R package Measure of Effect (MOTE) (Buchanan et al., 2019) to calculate 95% confidence intervals and Cohen’s dav (which provides difference scores as a ratio of the average standard deviation of the outcome at both timepoints), Cohen’s dz (which provides difference scores as a ratio of the standard deviation of change scores), and Cohen’s drm (which corrects dz by adjusting for the correlation between timepoints) (Lakens, 2013). When the standard deviations of both timepoints are similar, dav and drm are similar (Lakens, 2013). These calculations used a subsample of eligible respondents who completed the SSI and all pre- and post-intervention measures.

Exploratory Analyses

Within-SSI Questions about Body Positivity and Body Neutrality

Embedded in the SSI content were questions about body positivity and body neutrality. We used the responses of those who completed the SSI and the PFS to gather information on respondents’ perspectives about these constructs.

Deviation from Pre-Registered Analysis Plan

Of the six-item State Hope Scale (Snyder et al., 1996), we intended to only use the three-item, odd-numbered Pathways subscale in order to assess respondents’ perceived ability to identify goal-oriented routes (e.g., “I can think of many ways to reach my current goals”). Instead, we erroneously included the even-numbered Agency items (e.g., “At this time, I am meeting the goals that I have set for myself”), which are less amenable to short-term change. Because it is unlikely that responses to the Agency items can meaningfully change in approximately 30 minutes, their outcomes cannot be interpreted usefully or appropriately in this study. We are therefore not reporting this measure.

Results

Sample Characteristics

Over five days (October 12th-16th, 2022), 353 people accessed Project Body Neutrality. Of this group, 156 (44.19%) completed the screen and were part of our target population of 13 to 17-year-olds who reported non-zero mood problems and body image concerns. Of these 156 respondents, 150 scored ≥47 on the WCS, two scored <47 on the WCS and endorsed weight being more important than most things in life or the most important thing in life, and four scored <47 on the WCS and endorsed being very afraid of or terrified of gaining three pounds. This sample is thus comparable to studies that include individuals with ED risk factors on the basis of elevated weight concerns. Eighty-eight (56.41%) eligible respondents completed the SSI, 81 (51.92%) completed the PFS, and 75 (48.08%) completed all pre- and post-SSI questionnaires. This sample size is consistent with early trials of newly developed SSIs (Schleider & Weisz, 2018) and sufficient for assessing intervention acceptability and proximal outcomes (Julious, 2005; Whitehead et al., 2016).

Of the final sample of eligible “full-completers,” 74 (98.70%) were assigned female at birth. Gender identity was more diverse than sex assigned at birth, with less than half the sample identifying as a woman/girl (n = 36, 48.00%). In terms of sexual orientation, the three options most frequently selected were bisexual (n = 17, 22.70%), gay/lesbian/homosexual (n = 15, 20.00%), and straight/heterosexual (n = 12, 16.00%). Most respondents identified as White/Caucasian (n = 56, 74.70%), Asian (n = 13, 17.30%), and Hispanic/Latinx/Latine (n = 11, 14.70%). About one-third of the sample identified as having a disability (n = 28, 37.30%). All eligible respondents were 13 to 17-years old per the inclusion criteria. Multiple responses were allowed for racial/ethnic identity and gender identity, while all other demographic categories were limited to a single response. All demographics are reported in Table 1.

Table 1:

Respondent Demographics

| N (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Sex | ||

| Male | 1 (1.33%) | |

| Female | 74 (98.70%) | |

| Intersex | 0 (0.00%) | |

|

| ||

| Gender | ||

| Man/Boy | 7 (9.33%) | |

| Woman/Girl | 36 (48.00%) | |

| Transgender | 11 (14.70%) | |

| Female to male transgender | 9 (12.00%) | |

| Male to female transgender | 1 (1.33%) | |

| Trans male/Trans masculine | 10 (13.30%) | |

| Trans female/Trans feminine | 2 (2.67%) | |

| Genderqueer | 14 (18.70%) | |

| Gender expansive | 4 (5.33%) | |

| Androgynous | 10 (13.30%) | |

| Nonbinary | 24 (32.00%) | |

| Two-spirited | 1 (1.33%) | |

| Third gender | 0 (0.00%) | |

| Agender | 2 (2.67%) | |

| Not sure | 8 (10.70%) | |

| Other | 7 (9.33%) | |

|

| ||

| Sexual Orientation | ||

| Straight/Heterosexual | 12 (16.00%) | |

| Gay/Lesbian/Homosexual | 15 (20.00%) | |

| Bisexual | 17 (22.70%) | |

| Pansexual | 8 (10.70%) | |

| Queer | 8 (10.70%) | |

| Asexual | 1 (1.33%) | |

| Other | 4 (5.33%) | |

| Unsure/Questioning | 5 (6.67%) | |

| I do not use a label | 5 (6.67%) | |

| I do not want to respond | 0 (0.00%) | |

|

| ||

| Race and Ethnicity | ||

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 5 (6.67%) | |

| Asian | 13 (17.30%) | |

| Black/African American | 6 (8.00%) | |

| Hispanic/Latinx/Latine | 11 (14.70%) | |

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | 2 (2.67%) | |

| White/Caucasian | 56 (74.70%) | |

| Other | 1 (1.33%) | |

| Prefer not to answer | 3 (4.00%) | |

|

| ||

| Disabled | ||

| Yes | 28 (37.30%) | |

| No | 39 (52.00%) | |

| Prefer not to answer | 8 (10.70%) | |

Duration of Use and Dropout

Respondents spent averages of 3.76 minutes (SD = 2.73), 26.10 minutes (SD = 22.70), and 3.48 minutes (SD = 2.43) completing the pre-SSI questionnaires, the SSI itself, and the post-SSI questionnaires, respectively. Sixty-eight (19.26%) of the 353 respondents who started the survey discontinued while completing the screening questions; 29 (18.59%) of the 156 eligible respondents discontinued before completing the pre-SSI questionnaires; 39 (30.71%) of the 127 remaining discontinued during the SSI; and 13 (14.78%) of the 88 remaining discontinued before completing all the post-SSI questionnaires.

Program Feedback

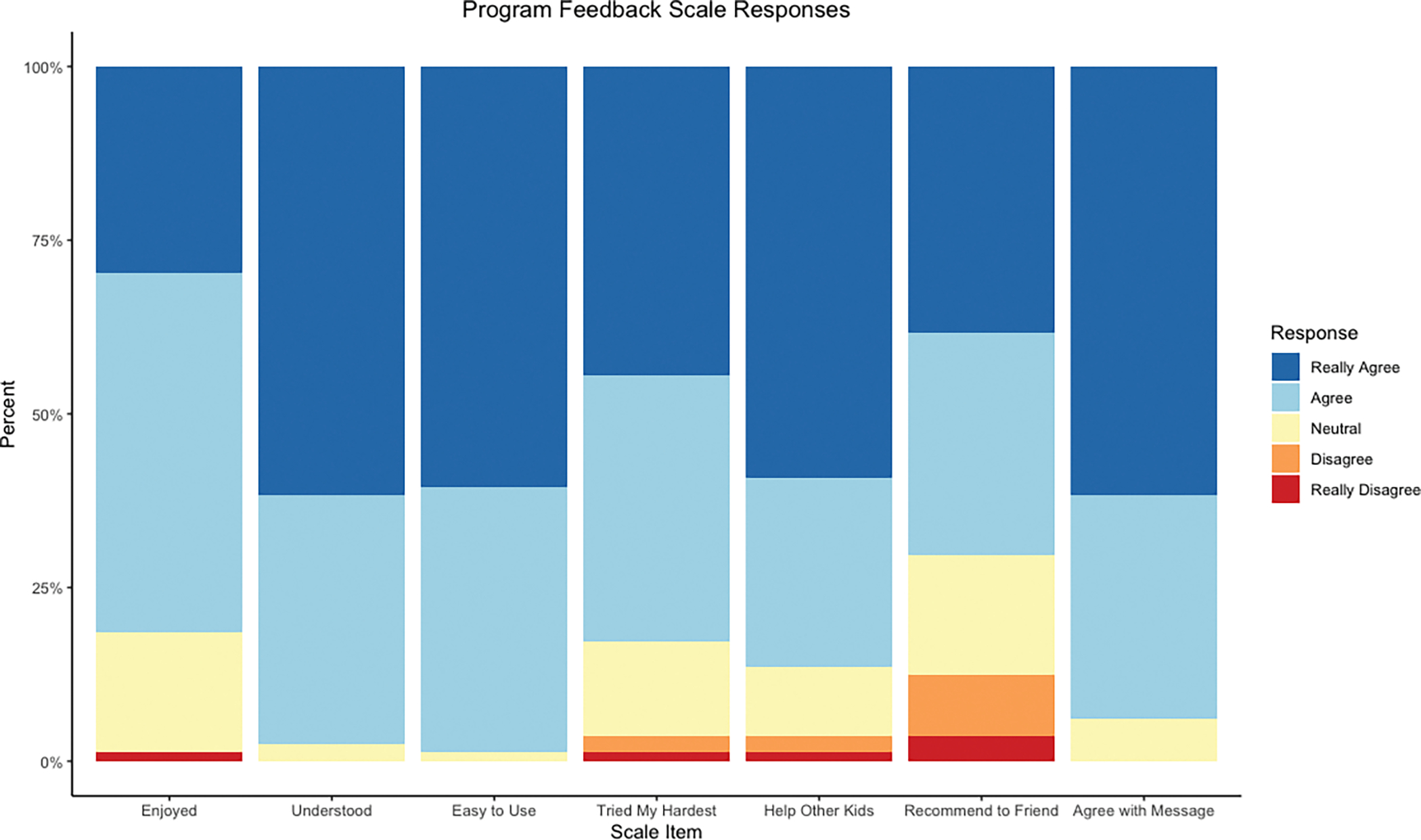

Eighty-one eligible respondents completed the SSI and the PFS. These respondents found Project Body Neutrality to be acceptable, with an overall mean score of 4.34/5 (SD = 0.54). Specifically, 81.48% of respondents agreed they enjoyed the SSI (M = 4.09, SD = 0.76), 97.53% agreed they understood it (M = 4.59, SD = 0.54), 98.77% found it easy to use (M = 4.59, SD = 0.52), and 82.72% reported they tried their hardest while using it (M = 4.22, SD = 0.87). Additionally, 86.42% of respondents thought the SSI would help others their age (M = 4.41, SD = 0.86), 70.37% would recommend it to a friend (M = 3.93, SD = 1.12), and 93.83% agreed with the activity’s message (M = 4.56, SD = 0.61). Figure 2 depicts the distribution of ratings.

Figure 2:

Program Feedback Scale Responses

Additionally, many respondents voluntarily provided written feedback. Sixty-two (76.54%) of the 81 PFS respondents shared positive feedback, 37 (45.68%) shared constructive feedback, and 38 (46.91%) shared other comments about the SSI. See Table 2 for examples of open-ended respondent feedback.

Table 2:

Program Feedback

| Positive Feedback | Constructive Feedback | Additional Feedback |

|---|---|---|

| “I appreciated the transparency, and found the questions opened the door for self reflection. Additionally I appreciated the diversity” | “I would change the message a little. Like i explained before, looks have importance. It might be shallow of me, but i would include positive thinking strategies for how we look.” | “This should also be advertised on TikTok since so many teens use it.” |

| “I found the language clear and inclusive, and there were many different types of people included (different pronouns, disabled people, poc, etc) so everyone feels included” | “I feel like the examples could be more tailored to our own identity. I couldn’t think of ways to help the disabled person with body neutrality because I haven’t experienced it” | “I think it would be a lot more helpful if it wasnť just a survey if it was an actual program or something” |

| “it was diverse, easy to use, and the images were nice. i felt like i could relate to it” | “The stories about the random people were kind of weird, I get iťs like #relatable type thing or whatever but they just feel like story book characters not really real people to relate to.” | “This should be an app in the future, using past responses and daily queries to help teens” |

| “I liked read other peoples problems and helping them and it really make you think to treat yourself like you would a stranger” | “Honestly it felt weirdly cheesy. Like something my school would make me fill out before they sent me to the school shrink.” | “You should reach out to schools about this I think it would benefit the girls at my all girls school [redacted]” |

| “What I likes about this activity is that it shows me what other people said and felt and it relates to me and makes me not feel lonely.” | “Id like a more operational definition of body positivity and body neutrality. I donť think iťs as clear as it could be in this activity” | “This should include more about how to deal with systemic issues” |

| “I really liked how it gave you a chance to share your mind to others and your own advice” | “Not much to be honest. Maybe make more? I would’ve liked to maybe see more specific things about different problems such as gender dysphoria, body dysmorphia, eating disorders, and resources for those issues.” | “Maybe some tips on how to feel more comfortable with your body on days where you just donť like how you look. Or give some advice on how to deal with EDs” |

| “The activities were helpful and there were lots of examples, it was good to have a takeaway” | “I didnť see teens that look like me, I have stereotypical features like blonde hair and blue eyes with freckles, but I'm plus size with narrow hips and have many other things about me that I didnť really see included.” | “This should include information about how to approach friends about this if they are struggling with it” |

Pre- to Post-Intervention Changes

Youth who completed the SSI and all questionnaires reported significant improvements in hopelessness, functionality appreciation, and body dissatisfaction. For reductions in hopelessness from pre- to post-intervention, effects were medium-to-large (dav = 0.60, 95% CI 0.35, 0.84; dz = 0.77, 95% CI 0.51, 1.02). For improvements in functionality appreciation from pre- to post-intervention, effects were large (dav = 0.72, 95% CI 0.46, 0.97; dz = 0.94, 95% CI 0.67, 1.21). There were medium-to-large effects for reductions in body dissatisfaction (dav = 0.61, 95% CI 0.36, 0.86; dz = 0.76, 95% CI 0.50, 1.02). Table 3 summarizes these results and includes drm values for comprehensiveness.

Table 3:

Changes in Proximal Outcomes

| Outcome | Pre-SSI: Mean (SD) | Post-SSI: Mean (SD) | Cohen’s dav (95% CI) |

Cohen’s dz (95% CI) |

Cohen’s drm (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Hopelessness | 7.35 (2.85) | 5.59 (3.04) | 0.60 (0.35, 0.84) |

0.77 (0.51, 1.02) |

0.60 (0.35, 0.84) |

| Functionality Appreciation |

20.50 (6.58) | 25.30 (6.66) | 0.72 (0.46, 0.97) |

0.94 (0.67, 1.21) |

0.72 (0.46, 0.97) |

| Body Dissatisfaction |

39.50 (5.89) | 35.40 (7.58) | 0.61 (0.36, 0.86) |

0.76 (0.50, 1.02) |

0.59 (0.34, 0.83) |

Perspectives on Body Positivity and Body Neutrality

When asked to select from any of ten (and/or generate their own) personal barriers to adopting a body positivity mindset, 91.40% (n = 74) of the 81 respondents who completed the PFS selected “Comparing myself to my friends,” 82.70% (n = 67) selected “Comments from family members, friends, or loved ones,” 70.40% (n = 57) selected “Messages/advertisements about weight loss or dieting,” 60.50% (n = 49) selected “Fatphobia” and “Lack of media representation of bodies like mine,” 58.00% (n = 47) selected “Gender dysphoria,” 50.60% (n = 41) selected “Bullying,” 42.00% (n = 34) selected “Comments from a doctor, coach, teacher, a health/wellness figure,” 18.50% (n = 15) selected “Ableism,” and 13.60% (n = 11) selected “Racism.” Two respondents shared additional barriers in the free response option: “BMI Scale” and “eating disorders.”

Most respondents endorsed having heard of body positivity before starting the SSI (n = 79, 97.50%), whereas most respondents had not heard of body neutrality (n = 45, 55.60%). Regardless of pre-existing familiarity, 90.12% of respondents (n = 73) provided open-ended responses about what the term body positivity means to them and 81.48% (n = 66) provided open-ended responses about what body neutrality means. See Table 4 for an illustrative selection of responses about adolescents’ perceived meanings of “body positivity” and “body neutrality.”

Table 4:

Definitions of Body Positivity and Body Neutrality:

| Body Positivity Definitions | Body Neutrality Definitions |

|---|---|

| “Loving your body and appreciating the way it looks no matter what.” | “No idea what it means” |

| “understanding that your body is something to cherish and hold high because it is uniquely yours” | “Appreciating your body not for the way it looks, but for what it does for you.” |

| “loving your body for what it does and how you're shaped because everyone is different and unique and a scale does not define beauty” | “It means to acknowledge how our bodies function and what it does for us. It feels more attainable and realistic some days.” |

| “Loving and respecting your body for what it is capable of and what it does for you” | “Neutrality on how ur body feels and looks neither good or bad?” |

| “It means to have a positive self image and viewpoint of your body, generally in terms of how it looks rather than what it does/how it feels” | “my guess is not hating your body but not forcing yourself to love it either” |

| “Everybody deserves to be able to show their body and live in their body without judgement from others.” | “accepting that you don’t have to love how you look to appreciate what it does for you and not feel like you need to change it” |

| “Societally accepting and positive attitude toward bodies of all shapes, sizes, abilities, and color.” | “Recognizing that our body is just one part of us and doesn’t define our actual selves. Our bodies don’t need to be seen as attractive or beautiful for us to exist and be respected. Our bodies do so much more and allow us to do so much more than be seen by others.” |

| “Be happy about your body which is difficult” | “being accepting of all bodies - none is better than the other” |

| “you have to love your body, even if youre just pretending to love it” | “Possibly meaning having a neutral opinion of your body / other people's body's” |

| “Loving yourself where you’re at and if you want to become healthier, do it while loving yourself and do it in a healthy way” | “Body neutrality means to have a neutral self image and viewpoint of your body, and not think about it in a positive or negative way (particularly in regards to how it looks). A lot more of body neutrality is focused on observing your body, what it does, and what it is capable of rather than making judgements or opinions. It’s also a lot of times used in eating disorder/body image recovery as a more realistic goal rather than body positivity, or as a stepping stone into positive body image” |

When asked to rate how much they like the ideas of body positivity and body neutrality, following the SSI, respondents rated body positivity an average of 2.99/5 (SD = 1.22). Body neutrality was rated higher, with a mean of 4.33/5 (SD = 0.85). When asked why they chose these ratings, 77.78% (n = 63) of respondents provided an open-ended response about their body positivity rating and 76.54% (n = 62) shared a response about their body neutrality rating. See Table 5 for an illustrative selection of respondents’ explanations about these ratings.

Table 5:

Ratings of Body Positivity and Body Neutrality

| Body Positivity Ratings | Body Neutrality Ratings |

|---|---|

| “Body positivity is unattainable for most, and truly ignores and marginalizes trans+, disabled, and bipoc communities who have more to their body image than just diet culture and looks. Although for some it can be empowering and helpful, for so many more it’s just ignorant and insulting to ignore that part of their identity and image.” | “It’s a lot easier to appreciate your body than to love it. For me, I struggle with medical conditions that can upset the way my body functions AND I struggle with body image and don’t like the way I look. Body neutrality is focusing on the good, however small it may be, rather than pretending that I love everything about my body.” |

| “It sounds great but it’s not when you don’t look like the majority of the standard” | “it makes more sense, to me at least, because literally nobody is going to be happy with their body looks 100% of the time, but people should always appreciate all the things it can do for you.” |

| “everyone deserves to feel good about themselves, but often times the body positivity mindset is impractical, if not toxic.” | “Iťs more nuanced. Accepting your body for what it is and being happy for the things it DOES do for you feels so much better than just sucking it up and trying to force myself to love my pain” |

| “Sometimes this just is not possible for people, and then they end up feeling broken or isolated for not being able to conform.” | “It’s great because it’s just appreciating what your body can do for you and isn’t tied to actually liking the way it looks” |

| “I donť like my body, but I like the idea of encouraging others to love their own” | “I’m proud of the things I can do and my body is the reason I can do it. That matters more than body positivity, because I can remember that no matter how I look my body is still doing the things it’s does and it’s taking care of me.” |

| “It helps people feel better with how they look and it makes them more confident!” | “It feels like I can reach it. Iťs not on such a high shelf. Iťs more scientific and it acknowledges the functions it allows me to do.” |

| “Iťs super great because it creates an atmosphere for everyone, if you are able to appreciate yourself and every curve or flat surface then you can start to focus on encouraging others to do the same making body shaming more stigmatized and scrutinized.” | “I gave this a 5 because I really love the idea of appreciating what my body can do first. Once I can appreciate what it can do no matter how it looks, I can actually love the way it looks BECAUSE of what it can do for me” |

| “It focuses on how your body looks, and also can encourage being an unhealthy size” | “It’s not toxic positivity and allows you to feel negative emotions while still being appreciative and grateful for what your body does for you.” |

| “It isnť a realistic goal and bodies shouldnť exist to be looked at and judged” | “People still treat me badly and my life is miserable because of my body” |

| “It focuses to much on loving your body the way it is.. making you feel like you have to lose weight to like it.” | “It doesnt hit all of the thought bases for me. I still struggle based on how I look because looks are a pillar of sociatal life. Everyone judges, and this might be shallow of me, but looks are important and I cannot just ignore them constantly.” |

Discussion

Overview of Findings

Adolescents who completed Project Body Neutrality—a digital, self-guided SSI targeting risk factors for depression and EDs—reported medium to large reductions in hopelessness and body dissatisfaction, and large increases in functionality appreciation, regardless of the effect size metric used. SSI completion was 56.41% and Project Body Neutrality was rated as highly acceptable (overall M = 4.34/5). The completion and acceptability of Project Body Neutrality are consistent with, and slightly stronger than, results from open trials of other SSIs (e.g., Schleider et al., 2020b), indicating its feasibility. Implementation models (RCT vs open program evaluation) and incentives (compensation vs no compensation) are factors that can predict SSI engagement. Participants in an RCT for which they received compensation were more likely to complete the SSI than participants in a non-randomized, non-paid program evaluation, and no other factor (age group, race/ethnicity, gender identity, sexual orientation, or baseline hopelessness scores) was a significant predictor (Cohen & Schleider, 2022). Since this study was a program evaluation with no compensation, the dropout rates we observed here align with the broader literature on SSIs and self-guided, online interventions.

In line with calls for more interventions to target shared risk factors (Ahuvia et al., 2022; Puccio et al., 2016; Becker et al., 2014), Project Body Neutrality targets transdiagnostically-relevant risk factors connected to depression and EDs. Its single-session format recognizes the dropout characteristic of longer-term interventions (Fleming et al., 2018; Clough et al., 2022), and capitalizes on the changes that can be accomplished in a short timeframe (Schleider et al., 2020a). These findings build on other recent research highlighting the benefits of single-session and low-intensity interventions for EDs. A single-session body image course resulted in significant, pre- to post-intervention improvements in body image with a moderate effect (d = 0.54) (Nemesure et al., 2022). Moreover, a meta-analysis found that low-intensity interventions were more effective at addressing DSM-5 severity related outcomes, and equivalent at reducing ED psychopathology, compared to high-intensity interventions (Davey et al., 2022).

Consistent with other web-based SSI trials (e.g., Schleider et al., 2020b), this pilot yielded a diverse sample of youth. Notably, this pilot reached many sexual and gender minority (SGM) youth. Disordered eating appears to be more common among SGM individuals than non-SGM individuals (Nagata et al., 2020; Goldhammer et al., 2019; Diemer et al., 2015), yet sexual minority youth underutilize ED treatment services, and ED prevention efforts are disproportionately aimed at cisgender girls/women (Cohn et al., 2016; Parmar et al., 2021). By advertising Project Body Neutrality on social media and allowing adolescents to participate anonymously, without parental content, the pilot minimized the social access barriers that youth often face when seeking treatment (McDanal et al., 2022). The resulting diverse sample may reflect the benefits of these research practices.

Strengths and Limitations

Project Body Neutrality has many strengths, including that it was designed to be delivered digitally—an important strategy for increasing access to mental health resources (Kazdin et al., 2017; Taylor et al., 2020). The pilot also adds to the limited academic literature on body neutrality. To meet the needs of gender diverse patients, some researchers and clients have suggested that ED treatments emphasize body neutrality (Perry et al., 2019; Hartman-Munick et al., 2021). With SSI completers endorsing the concept more strongly than body positivity (M endorsement = 4.33/5 vs M = 2.99/5), and 93.83% agreeing with the SSI’s message, the results imply that functionality appreciation, and potentially body neutrality overall, is an acceptable intervention target for adolescents struggling with body image and mood problems.

This pilot has limitations. Although prompts were revised to orient respondents to the present moment, some of the measures used to assess short-term changes (i.e., the Functionality Appreciation Scale and the Body Shape Satisfaction Scale) have not explicitly been validated as state measures. The use of adapted trait measures for state measurements is a limitation. Future research investigating the short-term impact of interventions on body dissatisfaction should consider the use of state measures such as the Body Image State Scale (Cash et al., 2002) and visual analogue scales, but at this time, there is no state measure designed to measure functionality appreciation specifically. In addition to continued use of the Beck Hopelessness Scale (Perczel Forintos et al., 2013), which has been used to measure short-term and long-term changes in hopelessness in large RCTs of SSIs (e.g., Schleider et al, 2022), it may be useful to also measure general state affect using the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (Watson et al., 1998). As observed in other SSI evaluations (Cohen & Schleider, 2022), about half of eligible respondents who accessed Project Body Neutrality completed the SSI and all pre- and post-SSI questionnaires. However, the non-completers’ data were not analyzed, so we did not examine their feedback. Additionally, the WCS, which has shown predictive validity for ED onset in girls (Killen et al., 1994), was used to assess eligibility. While it probable that a subset of our sample would qualify for an ED diagnosis, this was not assessed, and the predictive ability of this measure among boys enrolled in the study is limited. Furthermore, no cisgender boys (i.e., individuals assigned male at birth who currently identify as a man/boy) completed Project Body Neutrality and all the questionnaires. We were therefore unable to evaluate the acceptability and utility of the SSI for cisgender boys, despite this population’s need for ED treatment (Nagata et al., 2020). Finally, since this was a pilot, there was no control group. Therefore, it cannot be determined if the effects were due to providing an intervention in general, or if they were due specifically to the content of the SSI, and effect sizes may be unstable.

Future Directions and Implications

Project Body Neutrality may benefit from refinement that incorporates perspectives of end-users who were not represented in this evaluation, such as cisgender boys. Additionally, although immediate changes in transdiagnostically-relevant risk factors following Project Body Neutrality are potentially meaningful, randomized trials testing longer-term clinical effects—and testing shifts in proximal targets as mediators of long-term outcomes—are needed. Future work examining longer-term impacts on ED behaviors (e.g., restrictive eating, binge eating, purging, excessive exercising) will be particularly important given that other ED-focused SSIs (which did not teach about functionality appreciation or body neutrality) have previously shown large effects immediately post-intervention that were not sustained overtime (e.g., Diedrichs et al., 2015; Withers et al., 2002). While this study is an exciting beginning for research that incorporates the concept of body neutrality, research is needed to define body neutrality and produce valid scales that can allow researchers to measure its presence. We used the definitions of body neutrality available in the media to conceptualize functionality appreciation as a central component of body neutrality, but empirical research is necessary to better understand how body neutrality relates to other body image constructs, including functionality appreciation.

Results of our pilot also carry broader implications for ED research and practice. In the broader psychology literature, EDs are often characterized as “niche” disorders that are rare and disconnected from other mental health disorders (Haynos et al., under review). On the contrary, EDs are common and highly comorbid with other disorders, suggesting that interventions targeting shared risk factors may represent cost-effective “best-buys,” with broad public health applications (Kazdin et al., 2017). Our pilot of Project Body Neutrality adds to the literature on the feasibility of addressing risk factors associated with both EDs and depression (Stice et al., 2017). Results also bolster support for the utility of the single-session approach in mitigating body image concerns and potentially other ED symptoms—an intentionally-scalable intervention delivery model that circumvents long-standing barriers to accessing lengthy, costly ED treatments (Schleider et al., 2023). Additional work will ascertain the clinical and public health value of accessible, digital SSIs that intentionally address risk factors for both EDs and depression.

Public Health Significance Statement.

Results suggest the acceptability and utility of a digital, self-guided, single-session intervention—Project Body Neutrality—for adolescents experiencing co-occurring depressive symptoms and body image disturbances. Given the intervention’s low cost and inherent scalability, it may be positioned to provide support to youth with limited access to traditional care.

Acknowledgements:

JLS has received funding from the National Institute of Health Office of the Director (DP5OD028123), National Institute of Mental Health (R43MH128075), the Upswing Fund for Adolescent Mental Health, the National Science Foundation (2141710), Health Research and Services Association (U3NHP45406-01-00), the Society for Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, HopeLab, and the Klingenstein Third Generation Foundation. Preparation of this article was supported in part by the Implementation Research Institute (IRI), at the George Warren Brown School of Social Work, Washington University in St. Louis; through an award from the National Institute of Mental Health (R25MH080916; JLS is an IRI Fellow).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: JLS serves on the Scientific Advisory Board for Walden Wise and the Clinical Advisory Board for Koko; receives consulting fees from Kooth; is Co-Founder and Co-Director of Single Session Support Solutions; and receives book royalties from New Harbinger, Oxford University Press, and Little Brown Book Group.

Data Availability Statement:

The data and code that support the findings of this evaluation, excluding identifying information, are openly available at https://osf.io/w82bf/.

References

- Ahuvia I, Jans L, & Schleider J (2022). Secondary effects of body dissatisfaction interventions on adolescent depressive symptoms: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 55(2), 231–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alleva JM, Martijn C, Van Breukelen GJP, Jansen A, & Karos K (2015). Expand Your Horizon: A programme that improves body image and reduces self-objectification by training women to focus on body functionality. Body Image, 15, 81–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alleva JM, Diedrichs PC, Halliwell E, Martijn C, Stuijfzand BG, Treneman-Evans G, & Rumsey N (2018). A randomised-controlled trial investigating potential underlying mechanisms of a functionality-based approach to improving women’s body image. Body Image, 25, 85–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alleva JM, & Tylka TL (2021). Body functionality: A review of the literature. Body Image, 36, 149–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alleva JM, Tylka TL, & Kroon Van Diest AM (2017). The Functionality Appreciation Scale (FAS): Development and psychometric evaluation in U.S. community women and men. Body Image, 23, 28–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed., text rev.).

- Anastasiadou D, Folkvord F, & Lupiañez-Villanueva F (2018). A systematic review of mHealth interventions for the support of eating disorders. European Eating Disorders Review, 26(5), 394–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson M, & Jiang J (2018, May 31). Teens, Social Media and Technology 2018. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2018/05/31/teens-social-media-technology-2018/ [Google Scholar]

- Avalos LC, & Tylka TL (2006). Exploring a model of intuitive eating with college women. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 53(4), 486–497. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer R, Conell J, Glenn T, Alda M, Ardau R, Baune BT, Berk M, Bersudsky Y, Bilderbeck A, Bocchetta A, Bossini L, Castro AMP, Cheung EY, Chillotti C, Choppin S, Del Zompo M, Dias R, Dodd S, Duffy A, … Bauer M (2016). Internet use by patients with bipolar disorder: Results from an international multisite survey. Psychiatry Research, 242, 388–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumel A, Muench F, Edan S, & Kane JM (2019). Objective User Engagement With Mental Health Apps: Systematic Search and Panel-Based Usage Analysis. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 21(9), e14567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beilharz F, Sukunesan S, Rossell SL, Kulkarni J, & Sharp G (2021). Development of a positive body image chatbot (KIT) with young people and parents/carers: qualitative focus group study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 23(6), e27807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker CB, Plasencia M, Kilpela LS, Briggs M, & Stewart T (2014). Changing the course of comorbid eating disorders and depression: what is the role of public health interventions in targeting shared risk factors? Journal of Eating Disorders, 2, 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan E, Gillenwaters A, Scofield J, Valentine K (2019). MOTE: Measure of the Effect: Package to assist in effect size calculations and their confidence intervals. R package version 1.0.2, http://github.com/doomlab/MOTE.

- Button EJ, Chadalavada B, & Palmer RL (2010). Mortality and predictors of death in a cohort of patients presenting to an eating disorders service. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 43(5), 387–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cash TF, Fleming EC, Alindogan J, Steadman L, & Whitehead A (2002). Beyond body image as a trait: The development and validation of the Body Image States Scale. Eating Disorders, 10(2), 103–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cash TF, & Pruzinsky T (2002). Future challenges for body image theory, research, and clinical practice. In Cash TF & Pruzinsky T (Eds.), Body image: A handbook of theory, research, and clinical practice (pp. 509–516). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cassone S, Lewis V, & Crisp DA (2016). Enhancing positive body image: An evaluation of a cognitive behavioral therapy intervention and an exploration of the role of body shame. Eating Disorders, 24(5), 469–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavazos-Rehg P, Min C, Fitzsimmons-Craft EE, Savoy B, Kaiser N, Riordan R, Krauss M, Costello S, & Wilfley D (2020). Parental consent: A potential barrier for underage teens’ participation in an mHealth mental health intervention. Internet Interventions, 21, 100328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018, October 9). Youth Risk Behavior Survey Data Summary & Trends Report 2007–2017. National Prevention Information Network. https://npin.cdc.gov/publication/youth-risk-behavior-survey-data-summary-trends-report-2007-2017 [Google Scholar]

- Clark DB, & Kirisci L (1996). Posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, alcohol use disorders and quality of life in adolescents. Anxiety, 2(5), 226–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough B, Yousif C, Miles S, Stillerova S, Ganapathy A, & Casey L (2022). Understanding client engagement in digital mental health interventions: An investigation of the eTherapy Attitudes and Process Questionnaire. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 78(9), 1785–1805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen KA, & Schleider JL (2022). Adolescent dropout from brief digital mental health interventions within and beyond randomized trials. Internet Interventions, 27, 100496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen R, Irwin L, Newton-John T, & Slater A (2019). #bodypositivity: A content analysis of body positive accounts on Instagram. Body Image, 29, 47–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohn L, Murray SB, Walen A, & Wooldridge T (2016). Including the excluded: Males and gender minorities in eating disorder prevention. Eating Disorders, 24(1), 114–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook-Cottone CP (2015). Incorporating positive body image into the treatment of eating disorders: A model for attunement and mindful self-care. Body image, 14, 158–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowles C (2022, February 2). Can “body neutrality” change the way you work out? The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/02/02/well/move/body-neutrality-exercise.html [Google Scholar]

- Cwynar-Horta J (2016). The commodification of the body positive movement on Instagram. STREAM Journal, 8(2), 36–56. [Google Scholar]

- Darwin H, & Miller A (2021). Factions, frames, and postfeminism(s) in the Body Positive Movement. Feminist Media Studies, 21(6), 873–890. [Google Scholar]

- Davey E, Bennett S, Bryant-Waugh R, Micali N, Takeda A, Alexandrou A, & Shafran R (2022). Low intensity psychological interventions for the treatment of feeding and eating disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- de la Rie S, Noordenbos G, Donker M, & van Furth E (2007). The patient’s view on quality of life and eating disorders. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 40(1), 13–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diedrichs PC, Atkinson MJ, Steer RJ, Garbett KM, Rumsey N, & Halliwell E (2015). Effectiveness of a brief school-based body image intervention “Dove Confident Me: Single Session” when delivered by teachers and researchers: Results from a cluster randomised controlled trial. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 74, 94–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diemer EW, Grant JD, Munn-Chernoff MA, Patterson DA, & Duncan AE (2015). Gender Identity, Sexual Orientation, and Eating-Related Pathology in a National Sample of College Students. Journal of Adolescent Health, 57(2), 144–149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobias ML, Morris RR, & Schleider JL (2022). Single-Session Interventions Embedded Within Tumblr: Acceptability, Feasibility, and Utility Study. JMIR Formative Research, 6(7), e39004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunaev J, Markey CH, & Brochu PM (2018). An attitude of gratitude: The effects of body-focused gratitude on weight bias internalization and body image. Body Image, 25, 9–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn C, Bailey-Straebler S, Basden S, Doll H, Jones R, Murphy R, et al. (2015). A transdiagnostic comparison of enhanced cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT-E) and interpersonal psychotherapy in the treatment of eating disorders. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 70, 64–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzsimmons-Craft EE, Chan WW, Smith AC, Firebaugh M-L, Fowler LA, Topooco N, DePietro B, Wilfley DE, Taylor CB, & Jacobson NC (2022). Effectiveness of a chatbot for eating disorders prevention: A randomized clinical trial. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 55(3), 343–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming T, Bavin L, Lucassen M, Stasiak K, Hopkins S, & Merry S (2018). Beyond the Trial: Systematic Review of Real-World Uptake and Engagement With Digital Self-Help Interventions for Depression, Low Mood, or Anxiety. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 20(6), e199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franzoi SL (1995). The body-as-object versus the body-as-process: Gender differences and gender considerations. Sex Roles, 33(5–6), 417–437. [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson BL, & Roberts T-A (1997). Objectification theory: Toward understanding women’s lived experiences and mental health risks. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 21(2),173–206. [Google Scholar]

- Gay K, Torous J, Joseph A, Pandya A, & Duckworth K (2016). Digital Technology Use Among Individuals with Schizophrenia: Results of an Online Survey. JMIR Mental Health, 3(2), e15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldhammer HB, Maston ED, & Keuroghlian AS (2019). Addressing Eating Disorders and Body Dissatisfaction in Sexual and Gender Minority Youth. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 56(2), 318–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldschmidt AB, Wall M, Choo T-HJ, Becker C, & Neumark-Sztainer D (2016). Shared risk factors for mood-, eating-, and weight-related health outcomes. Health Psychology, 35(3), 245–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths S, Murray SB, Bentley C, Gratwick-Sarll K, Harrison C, & Mond JM (2017). Sex Differences in Quality of Life Impairment Associated With Body Dissatisfaction in Adolescents. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 61(1), 77–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartman-Munick SM, Silverstein S, Guss CE, Lopez E, Calzo JP, & Gordon AR (2021). Eating disorder screening and treatment experiences in transgender and gender diverse young adults. Eating Behaviors, 41, 101517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haupt A (2022, February 25). You don’t have to love or hate your body. Here’s how to adopt “body neutrality.” The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/wellness/2022/02/25/body-neutrality-definition/ [Google Scholar]

- Haynos AF, Egbert AH, Fitzsimmons-Craft EE, Levinson CA, & Schleider JL (under review). Not niche: Eating disorders and the dangers of over-specialization. 10.31234/osf.io/cvsre [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hjern A, Lindberg L, & Lindblad F (2006). Outcome and prognostic factors for adolescent female in-patients with anorexia nervosa: 9- to 4-year follow-up. British Journal of Psychiatry, 189(5), 428–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyt MF, Bobele M, Slive A, Young J, & Talmon M (2018). Single-session/one-at-a-time walk-in therapy. In Single-Session Therapy by Walk-In or Appointment (pp. 3–24). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobi C, & Fittig E (2010). Psychosocial risk factors for eating disorders. In Agras WS & Robinson A (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Eating Disorders (pp. 106–125). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan S (2023, Jan 3). Body Neutrality: What It Is and How It Can Help with Body Image. Philadelphia Magazine. https://www.phillymag.com/be-well-philly/2023/01/03/body-neutrality-body-image/ [Google Scholar]

- Julious SA (2005). Sample size of 12 per group rule of thumb for a pilot study. Pharmaceutical Statistics: Journal of Applied Statistics in the Pharmaceutical Industry, 4(4), 287–291 [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE (2019). Annual Research Review: Expanding mental health services through novel models of intervention delivery. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 60(4), 455–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE, Fitzsimmons-Craft EE, & Wilfley DE (2017). Addressing critical gaps in the treatment of eating disorders. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 50(3), 170–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan A (2022, May 18). The “body neutrality” movement wants you to care less about how you look. VICE. https://www.vice.com/en/article/qjb7ww/body-neutrality-movement-identity-body-positivity-toxic [Google Scholar]

- Killen JD, Taylor CB, Hayward C, Wilson DM, Haydel KF, Hammer LD, Simmonds B, Robinson TN, Litt I, & Varady A (1994). Pursuit of thinness and onset of eating disorder symptoms in a community sample of adolescent girls: a three-year prospective analysis. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 16(3), 227–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koller KA, Thompson KA, Miller AJ, Walsh EC, & Bardone-Cone AM (2020). Body appreciation and intuitive eating in eating disorder recovery. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 53(8), 1261–1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, & Williams JBW (2003). The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Medical Care, 41(11), 1284–1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakens D (2013). Calculating and reporting effect sizes to facilitate cumulative science: a practical primer for t-tests and ANOVAs. Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazuka RF, Wick MR, Keel PK, & Harriger JA (2020). Are We There Yet? Progress in Depicting Diverse Images of Beauty in Instagram’s Body Positivity Movement. Body Image, 34, 85–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legault L, & Sago A (2022). When body positivity falls flat: Divergent effects of body acceptance messages that support vs. undermine basic psychological needs. Body Image, 41, 225–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehtimaki S, Martic J, Wahl B, Foster KT, & Schwalbe N (2021). Evidence on Digital Mental Health Interventions for Adolescents and Young People: Systematic Overview. JMIR Mental Health, 8(4), e25847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linardon J, Gleeson J, Yap K, Murphy K, & Brennan L (2019). Meta-analysis of the effects of third-wave behavioural interventions on disordered eating and body image concerns: implications for eating disorder prevention. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 48(1), 15–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linardon J, McClure Z, Tylka TL, & Fuller-Tyszkiewicz M (2022). Body appreciation and its psychological correlates: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Body Image, 42, 287–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDanal R, Rubin A, Fox KR, & Schleider JL (2022). Associations of LGBTQ+ Identities on Acceptability and Response to Online Single-Session Youth Mental Health Interventions. Behavior Therapy, 53(2), 376–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire JK, Doty JL, Catalpa JM, & Ola C (2016). Body image in transgender young people: Findings from a qualitative, community based study. Body Image, 18, 96–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh V, Jordan J, Carter J, Luty S, McKenzie J, Bulik C, et al. (2016). Psychotherapy for transdiagnostic binge eating: A randomized controlled trial of cognitive-behavioural therapy, appetite-focused cognitive-behavioural therapy, and scheme therapy. Psychiatric Research, 240, 412–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller AL (2016). Eating the Other Yogi: Kathryn Budig, the Yoga Industrial Complex, and the Appropriation of Body Positivity. Race and Yoga, 1(1). [Google Scholar]

- Mulgrew KE, Prichard I, Stalley N, & Lim MSC (2019). Effectiveness of a multi-session positive self, appearance, and functionality program on women’s body satisfaction and response to media. Body Image, 31, 102–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulgrew KE, Stalley NL, & Tiggemann M (2017). Positive appearance and functionality reflections can improve body satisfaction but do not protect against idealised media exposure. Body Image, 23, 126–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagata JM, Ganson KT, & Austin SB (2020). Emerging trends in eating disorders among sexual and gender minorities. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 33(6), 562–567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemesure MD, Park C, Morris RR, Chan WW, Fitzsimmons-Craft EE, Rackoff GN, Fowler LA, Taylor CB, & Jacobson NC (2022). Evaluating change in body image concerns following a single session digital intervention. Body Image, 44, 64–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer KM, & Burrows V (2021). Ethical and Safety Concerns Regarding the Use of Mental Health–Related Apps in Counseling: Considerations for Counselors. Journal of Technology in Behavioral Science, 6(1), 137–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parmar DD, Alabaster A, Vance S Jr, Ritterman Weintraub ML, & Lau JS (2021). Disordered Eating, Body Image Dissatisfaction, and Associated Healthcare Utilization Patterns for Sexual Minority Youth. Journal of Adolescent Health, 69(3), 470–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxton SJ, Neumark-Sztainer D, Hannan PJ, & Eisenberg ME (2006). Body dissatisfaction prospectively predicts depressive mood and low self-esteem in adolescent girls and boys. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 35(4), 539–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennesi JL, & Wade TD (2018). Imagery rescripting and cognitive dissonance: A randomized controlled trial of two brief online interventions for women at risk of developing an eating disorder. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 51(5), 439–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perczel Forintos D, Rózsa S, Pilling J, & Kopp M (2013). Proposal for a short version of the Beck Hopelessness Scale based on a national representative survey in Hungary. Community Mental Health Journal, 49(6), 822–830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]