Summary

The HNRNPH2 proline-tyrosine nuclear-localization-signal/PY-NLS is mutated in HNRNPH2-related X-linked neurodevelopmental disorder, causing the normally nuclear HNRNPH2 to accumulate in the cytoplasm. We solved the cryo-EM structure of Karyopherin-β2/Transportin-1 bound to the HNRNPH2 PY-NLS to understand importin-NLS recognition and disruption in disease. HNRNPH2 206RPGPY210 is a typical R-X2-4-P-Y motif comprising PY-NLS epitopes 2 and 3, followed by an additional Karyopherin–β2-binding epitope at residues 211DRP213 we term epitope 4; no density is present for PY-NLS epitope 1. Disease variant mutations at epitopes 2-4 impair Karyopherin-β2 binding and cause aberrant cytoplasmic accumulation in cells, emphasizing the role of nuclear import defect in disease. Sequence/structure analysis suggests that strong PY-NLS epitopes 4 are rare and thus far limited to close paralogs of HNRNPH2, HNRNPH1 and HNRNPF. Epitope 4-binidng hotspot Karyopherin-β2 W373 corresponds to close paralog Karyopherin-β2b/Transportin-2 W370, a pathological variants site in neurodevelopmental abnormalities, suggesting that Karyopherin-β2b/Transportin-2-HNRNPH2/H1/F interactions may be compromised in the abnormalities.

Graphical Abstract

eTOC blurb

Gonzalez et al. present a cryo-EM structure of Karyopherin-β2 bound to HNRNPH2 PY-NLS peptide, which explains nuclear import defects of HNRNPH2 variants in HNRNPH2-related X-linked neurodevelopmental disorder and reveals a new PY-NLS epitope that suggests mechanistic changes in pathological variants of the Karyopherin-β2 paralog Transportin-2 in neurodevelopmental abnormalities.

Introduction

Karyopherin-β2 and Karyopherin-β2b (Kapβ2 and Kapβ2b, also named Transportin-1/TNPO1 or Transportin-2/TNPO2) are close paralogs (85% sequence identity) in the Karyopherin-β family of nuclear transport receptors.1-5 Kapβ2 and Kapβ2b transport many of the same RNA binding proteins from the cytoplasm into the nucleus. These cargos include HNRNPs A1, A2, D, F, H1, H2, FUS, EWS and TAF15, many of which are linked to neurodegenerative, neuromuscular, or neurodevelopmental diseases.6,7 FUS, EWS, TAF15, HNRNP A1 and HNRNP A2 are linked to amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and frontal temporal dementia (FTD), HNRNPs A1 and A2 are also involved in multisystem proteinopathy, HNRNPDL in limb girdle muscular dystrophy, and HNRNPs H1 and H2 (also known as H’) in neurodevelopmental disorders.8,9 Pathogenesis of these diseases involves aberrant cytoplasmic localization of nuclear import cargos due to defects in Kapβ2-mediated nuclear import.8,10

The Kapβ2 proteins bind to very diverse 15-100 residues long nuclear localization signals (NLSs) in their cargos that are named the proline-tyrosine- or PY-NLSs. These signals reside in intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs) of the cargos, have overall basic character, and contain a set of 2-3 Kapβ2-binding sequence motifs or epitopes.7,11,12 PY-NLS epitope 1 is a hydrophobic or basic motif at the N-terminus of the NLS, epitope 2 is often a single arginine residue or sometimes a helix with multiple arginine residues and epitope 3 is most often a proline-tyrosine (PY) dipeptide. Epitopes 2 and 3 together make up the C-terminal RX2-5PY motif. Some PY-NLSs use all three epitopes and others use only a subset of the three epitopes to bind Kapβ2/Kapβ2b.7,13 Mutations in the Kapβ2 cargos FUS, HNRNPH2 and HNRNPH1 are found in epitopes 2 or 3 of their PY-NLSs in familial ALS, HNRNPH2-related X-linked neurodevelopmental disorder and HNRNPH1-related syndromic intellectual disability, respectively.8,10,14-17

Disease mutations in the FUS PY-NLS have been examined structurally and quantitatively, but the mechanism of how the PY-NLS of HNRNPH2 binds Kapβ2 and how pathogenic variants affect the interaction have not been studied.10,18 HNRNPH2 and its close paralog HNRNPH1 are RNA processing proteins that shuttle between the nucleus and cytoplasm, but the proteins mostly reside in the nucleus.19 Both proteins are involved in transcription, mRNA splicing, translation, mRNA degradation and localization. Most patients with HNRNPH2-related X-linked neurodevelopmental disorder have mutations in or near the HNRNPH2 PY-NLS (R206W, R206Q, R206G, R206L, P209L, Y210C, R212S, R212T, R212G and P213L) that cause the normally nuclear HNRNPH2 to accumulate in the cytoplasm and associate with stress granules upon stress (Figure 1A).14,15,20 The mutations at R206 and P209/Y210 are likely in epitopes 2 and 3 of the PY-NLS, respectively, but the roles of R212 and P213 are unknown. Here, we examined how the HNRNPH2 PY-NLS binds Kapβ2, how binding energy is distributed across the NLS sequence and how disease-causing mutations affect Kapβ2-cargo interactions.

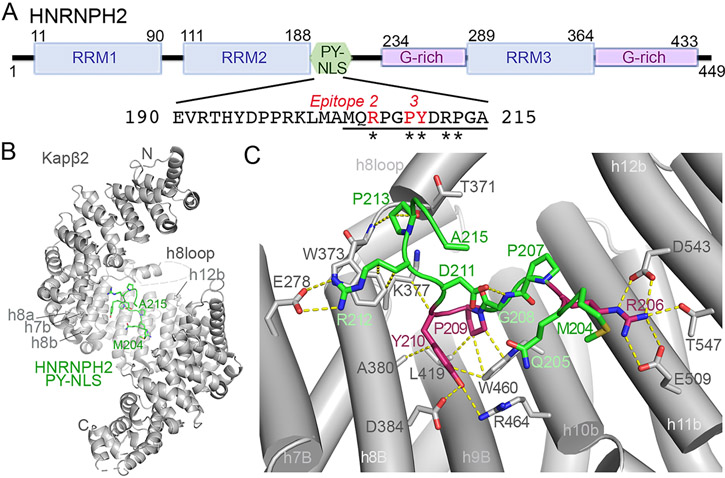

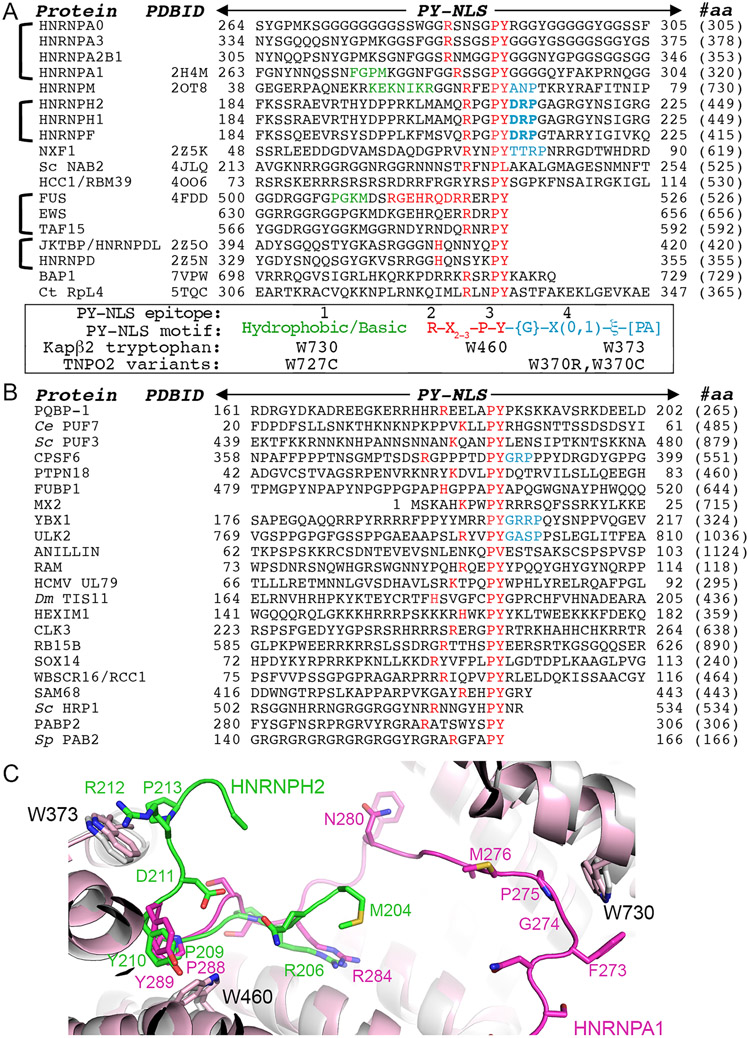

Figure 1. Structure of Kapβ2 bound to the HNRNPH2 PY-NLS.

(A) Schematic of the HNRNPH2 domains and the PY-NLS sequence. PY-NLS residues that were modeled in the Kapβ2•HNRNPH2 cryo-EM structure are underlined with notation of the appropriate PY-NLS epitopes, and variants found in HNRNPH2-related X-linked neurodevelopmental disorder are marked with asterisks. (B) Overall structure of HNRNPH2(103-225) (green) bound to Kapβ2 (gray). The determination of appropriate fragment used for assembly of the complex is shown in Figure S1; map statistics and densities are in Figure S2 and S3, and data statistics in Table 2. (C) Interactions of HNRNPH2 PY-NLS with Kapβ2 (contacts < 4Å shown with yellow dashed lines). Epitopes 2 and 3 (R206, P209 and Y210) are colored red as in (A). See also Figure S1-3.

Results and discussion

Cryo-EM structure of Kapβ2 bound to HNRNPH2(103-225)

The 449-amino acid HNRNPH2 protein contains three RNA Recognition Motif (RRM) domains: RRM1 and RRM2 are connected by a short linker while RRM2 and RRM3 are connected by a 100-reside disordered linker that contains a PY-NLS followed by a glycine-rich segment (Figure 1A). PY-NLS-containing HNRNPH2 fragments are prone to proteolytic degradation. We used pull-down binding assays and mapped the Kapβ2-binding HNRNPH2 segment that is most stable against proteolytic degradation to residues 103-225. This HNRNPH2 fragment covers the RRM2 domain followed by 47 residues that contain the PY-NLS (Figure S1A). HNRNPH2(103-225) shows minimal proteolytic degradation and binds Kapβ2 tightly with a dissociation constant (KD) of 50 nM, measured by isothermal titration calorimetry or ITC (Table 1 and Figure S1B). A shorter fragment that does not contain RRM2 (residues 190-225) binds Kapβ2 tightly with a KD of 40 nM, similar affinity as HNRNPH2(103-225), but is highly prone to degradation (Table 1 and Figure S1C). RRM2 domain alone shows no detectable Kapβ2-binding (Table 1 and Figure S1D) – inclusion of the RRM2 in the HNRNPH2(103-225) construct appears critical only for the technical purpose of maintaining an intact and non-degraded PY-NLS.

Table 1.

| Sample in the cell | Titrant in the syringe | KD [2σa] |

|---|---|---|

| Kapβ2 | MBP-HNRNPH2 | |

| WT | RRM2-PY-NLS (103-225) | 50 [24, 87] nM |

| WT | PY-NLS (190-225) | 40 [24, 60] nM |

| WT | RRM2 (103-189) | No binding |

| Kapβ2 | MBP-HNRNPH2 (103-225) | |

| WT | R206W | 5.2 [2, 28] μM |

| WT | R206Q | 3.6 [1.6, 9] μM |

| WT | P209L | 16.3 [2.3, 47] μM |

| WT | R212A | 3.2 [2, 5.5] μM |

| W373A | WT | 6.1 [3, 36] μM |

| Kapβ2 | MBP-HNRNPM PY-NLS (41-70) | |

| WT | WT | 9 [1.8, 22] nMb |

| W373A | WT | 4.5 [U, 11.7] nM |

95% confidence interval determined by error-surface projection in the global analysis of duplicate experiments.

A single measurement was done as the same experiment was previously published.11

We assembled a complex of Kapβ2 bound to HNRNPH2(103-225) for single particle cryo-EM structure determination. Initial attempts yielded a map with no clear density for the HNRNPH2 peptide. We therefore subjected the complex to mild crosslinking and then cryo-EM data collection. Because of the small and symmetrical nature of Kapβ2 molecule (890 amino acids), the cryo-EM particles obtained for the Kapβ2*HNRNPH2(103-225) sample were filtered by many rounds of 2D classification and then further cleaned up in 3D classification. ~ 30% of the particles used in 3D classification were used for reconstruction of a single class of Kapβ2 with well-defined features for the entire superhelix; the remaining particles partitioned into six other classes that looked like incomplete pieces of Kapβ2 (Figure S2). A final non-uniform refinement produced a map of 3.2 A resolution that we used to solve the structure of Kapβ2•HNRNPH2 complex (Statistics in Figure S2 and Table 2, local resolution in Figure S3A).

Table 2:

Cryo-EM data collection, refinement, and validation

| Kapβ2-HNRNPH2(103-225) | |

|---|---|

| Data collection and processing | |

| Facility | UTSW |

| Magnification | 105kx |

| Voltage (kV) | 300 |

| Electron exposure (e−/Å2) | 60 |

| Defocus range (μm) | −1.0 to −2.2 |

| Pixel size (Å) | 0.415 |

| Symmetry imposed | C1 |

| Initial particle images (no.) | 4,042,358 |

| Final particle images (no.) | 208,572 |

| Map resolution (Å) | 3.17 |

| FSC threshold | 0.143 |

| Refinement | |

| Initial model used (PDB | 2OT8 |

| Model resolution (Å) | 3.0/3.1/3.3 |

| FSC threshold | 0/0.143/0.5 |

| Map sharpening B factor (Å2) | 116.5 |

| Model composition | |

| Nonhydrogen atom | 6831 |

| Protein residues | 856 |

| Ligand | 0 |

| B factors (min/max/mean) (Å2) | |

| Protein | 68.79/419.83/169.44 |

| Ligand | 0 |

| R.m.s. deviations | |

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.003 |

| Bond angles (°) | 0.715 |

| Validation | |

| MolProbity score | 1.36 |

| Clashscore | 6.06 |

| Poor rotamers (%) | 0.13 |

| Ramachandran plot | |

| Favored (%) | 97.88 |

| Allowed (%) | 2.12 |

| Outliers (%) | 0.0 |

| CaBLAM outliers (%) | 0.36 |

| PDB/EMDB ID | 8SGH/EMD-40455 |

Kapβ2 adopts a superhelical conformation of 20 HEAT repeats (h1-h20, each with a pair of antiparallel a and b helices) (Figure 1B). All previous Kapβ2*PY-NLS structures in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) were solved by X-ray crystallography, using a Kapβ2 construct where the long and flexible 67-residue HEAT repeat 8 loop (h8loop) was truncated.10,13,21 This is the first structure of a complex that contains the full length Kapβ2 with an intact h8loop. We modeled Kapβ2 h8loop residues 308-325 and 362-374 that contain two short helices proximal to the a and b helices of repeat h8; no density is present for distal h8loop residues 326-361 (Figure S3B). The resolution of the cryo-EM map and the density at the N- and C-terminal Kapβ2 HEAT repeats (h1 and h17-h20) deteriorate (Figure S3A), suggesting flexibility at the termini of the Kapβ2 superhelix, similar to recent cryo-EM structures of cargo-bound yeast importin Kap114.22

The cryo-EM density corresponding to the HNRNP PY-NLS is strong and the local resolution of the peptide, except at the very N-terminus, is at ~ 3.2 A resolution (Figure S3C). We modeled HNRNPH2 residues 204-215, which bind across the C-terminal concave surface of Kapβ2, with the b helices of repeats h7-h12 (Figure 1A-C and S3C). The conformation of this binding site is very similar to those of other PY-NLS bound Kapβ2 structures (2H4M, 2OT8, 2Z5K, 4FDD, 4JLQ, 4OO6; root mean square deviation or RMSD values aligning residues in h7-h16 are 0.9-1.5 A).10,12,21,23 No density is present for the RRM2 domain (residues 103-188) and residues 189-203 at the N-terminus of the PY-NLS. The persistently bound portion of the HNRNPH2 PY-NLS (residues 204-215) covers PY-NLS epitope 2 (R206), epitope 3 (209PY210) and five residues C-terminal of the PY-motif (211DRPGA215) (Figure 1A and C). The absence of cryo-EM density for residues N-terminal of M204 suggests that epitope 1 of the HNRNPH2 PY-NLS either binds very weakly or is absent.

Kapβ2-HNRNPH2 PY-NLS interactions: epitopes 2 and 3

HNRNPH2 R206 (epitope 2 of the PY-NLS) is a mutational hot spot for HNRNPH2-related X-linked neurodevelopmental disorder.14,15 Like all previously observed epitope 2 arginine residues, R206 contacts several acidic residues of Kapβ2 (Figure 1C).11,12,23,24 ITC data show that two of the most prevalent mutations of R206 found in patients, R206W and R206Q, decreased Kapβ2 affinities by 70-100 fold (Table 1; Figure S4A-C). Such significant Kapβ2-binding defects explain the aberrant accumulation of HNRNPH2 R206 variants in the cytoplasm and association with stress granules upon stress.20 The less prevalent R206G and R206L epitope 2 variants also cannot participate in electrostatic interactions with Kapβ2 and are expected to have substantially decreased Kapβ2 affinities and aberrant subcellular localization (binding and localization of these HNRNPH2 R206 variants have not been performed).

Residues that flank HNRNPH2 R206, 204MQ205 and 207PG208, make no contact with Kapβ2. Further C-terminus, the HNRNPH2 209PY210 dipeptide is a typical PY-NLS epitope 3 that contacts Kapβ2 residues W460, L419 and A380, most likely through multiple polar and hydrophobic interactions (Figure 1C). Variants of the PY motif, P209L and Y210C, have been identified in patients.14,15 The P209L mutation of HNRNPH2(103-225) decreased Kapβ2 affinity by ~ 200 fold (Table 1; Figure S4D), consistent with its aberrant localization in cells.20 The pathogenic HNRNPH2 Y210C variant also abolished interactions with Kapβ2 and accumulated in the cytoplasm20, consistent with the many contacts that Y210 makes with Kapβ2 in the structure.

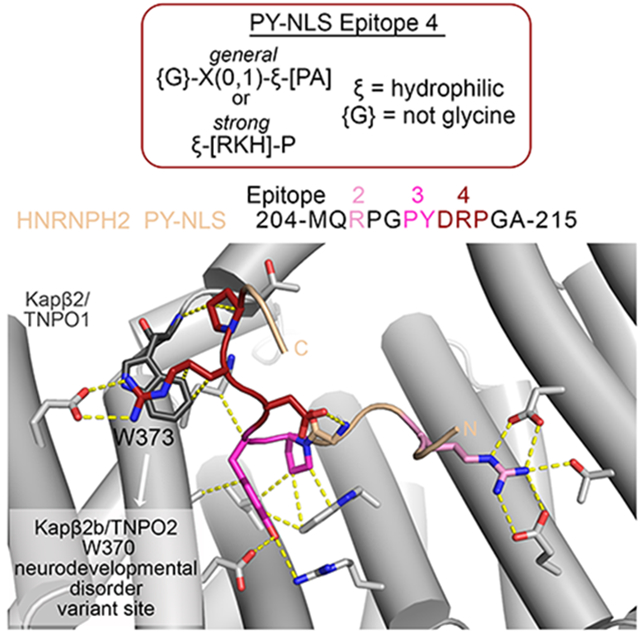

Kapβ2-HNRNPH2 PY-NLS interactions C-terminal of the PY-motif - epitope 4

C-terminal of the PY motif, the HNRNPH2 polypeptide chain takes a turn and almost folds back on itself, likely stabilized by intramolecular contacts between side chain of D211 with the main chain of G208 (Figure 1C). The β-turn-like conformation positions the next two residues, R212 and P213, to contact Kapβ2 residues E278, W373 and T371 from repeats h7 and h8 (Figure 1C). HNRNPH2 R212 likely makes electrostatic interactions with Kapβ2 residue E278 and the aliphatic portion of its side chain makes hydrophobic interactions with Kapβ2 W373. HNRNPH2 P213 also appears to make hydrophobic interactions with Kapβ2 W373.

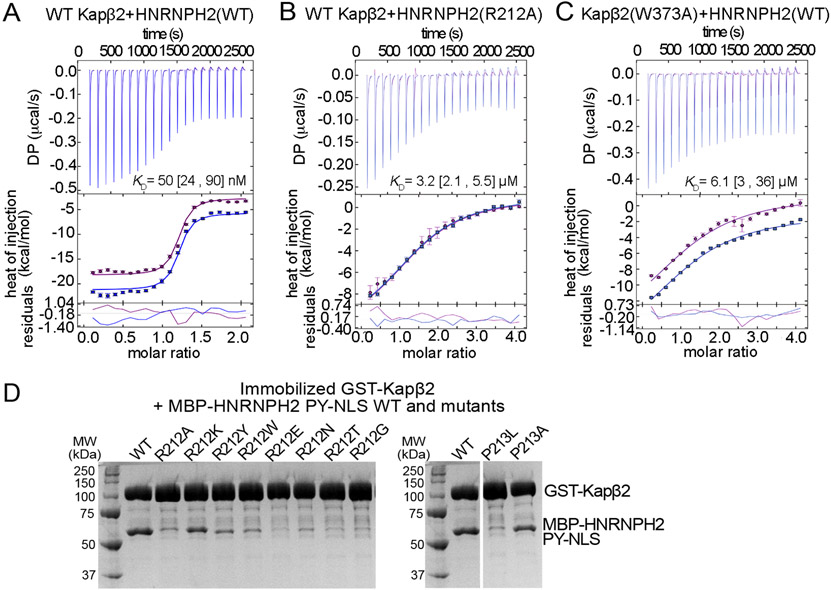

We generated the MBP-HNRNPH2(103-225) R212A mutant to test the importance of side chain contacts made by R212. The R212A mutation decreased Kapβ2 affinity by 64-fold (ITC KD of 3.2 μM; Table 1 and Figure 2A and B). We also mutated the Kapβ2 residue (W373) that contacts HNRNPH2 R212 and P213, to alanine. Kapβ2(W373A) bound WT HNRNPH2 120-fold weaker (KD 6.1 μM) (Table 1 and Figure 2C). These results suggest that HNRNPH2 R212 and Kapβ2 W373 are binding hotspots for Kapβ2-HNRNPH2 interactions.

Figure 2. HNRNPH2 residues 212RP213 and Kapβ2-W373 are binding hotspots for Kapβ2-HNRNPH2 interactions.

(A-C) ITC titration of MBP-HNRNPH2(103-225) WT binding to WT Kapβ2 (A), MBP-HNRNPH2(103-225) R212A to WT Kapβ2 (B) or MBP-HNRNPH2(103-225) WT to Kapβ2(W373A) mutant (C). The top panels show reconstructed thermograms from NITPIC, the middle panels show binding isotherms and individual fits, and the bottom panels show the fitting residuals. Dissociation constants or KDs obtained from global analysis of duplicate measurement are displayed with 95% confidence intervals in brackets. (D) Pull-down binding assay with GST-Kapβ2 immobilized on glutathione beads incubated with MBP-HNRNPH2(103-225) WT or mutant proteins and then washed extensively. Bound proteins were separated and visualized by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie-staining. The gel on the left shows binding assays comparing interactions of HNRNPH2 WT (control) with various mutants of HNRNPH2 R212. The same HNRNPH2 WT control is shown on the right for comparison with mutants of HNRNPH2 P213.

We also mutated HNRNPH2 R212 to lysine (K), tyrosine (Y), tryptophan (W), glutamic acid (E) or asparagine (N) to test the importance of electrostatic, polar or hydrophobic interactions by a side chain at position 212. Furthermore, R212T and R212G were recently identified as variants in HNRNPH2-related X-linked neurodevelopmental disorder.15,20 We probed Kapβ2-binding using qualitative pull-down binding assays with immobilized GST-Kapβ2 and MBP-HNRNPH2(103-225) (Figure 2D). R212A, E, N, T or G mutations greatly decreased the amount of MBP-HNRNPH2 that was pulled down by GST-Kapβ2 while R212Y and W showed some residual binding and R212K showed the least impairment. These results suggest that both hydrophobic and electrostatic interactions from basic side chains at HNRNPH2 residue 212 are important for Kapβ2-binding. Thus, arginine, lysine and likely histidine (R/K/H) are preferred at position 212 of HNRNPH2.

To probe the importance of HNRNPH2 P213, we mutated the residue to alanine and leucine (P213L is also a recently discovered neurodevelopmental disorder variant site) and tested the mutants by pull-down binding assay. The P213L mutant substantially decreased the amount of HNRNPH2(103-225) that was pulled down by GST-Kapβ2, but interestingly the P213A mutant caused only a small decrease when compared to WT (Figure 2D). These results suggest that although a proline at position 213 is ideal, a small side chain like alanine is better tolerated than a bulky one like leucine. Altogether, mutagenic binding studies of R212 and P213 of HNRNPH2 suggest that the two residues are part of a Kapβ2-binding hotspot that may constitute a new PY-NLS epitope that we term epitope 4.

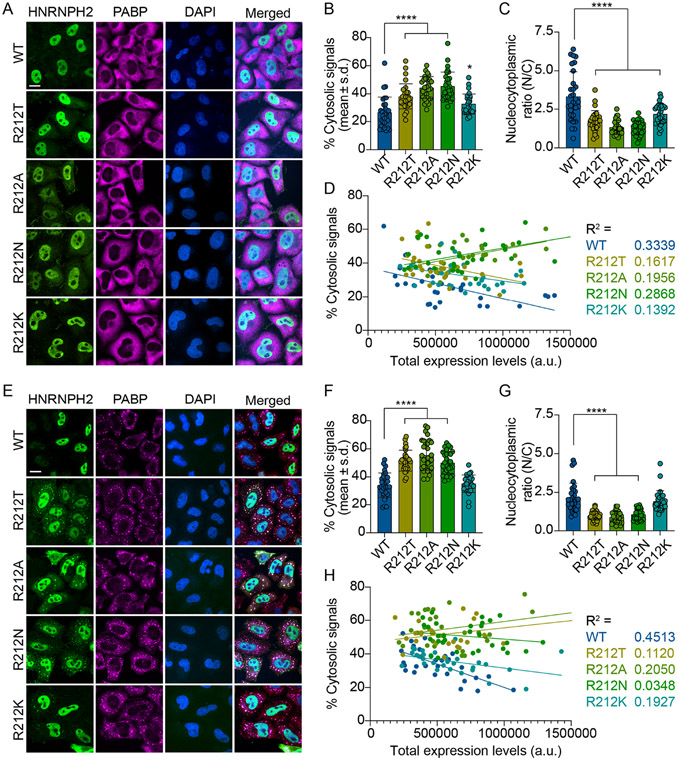

To examine the consequence of epitope 4 mutations on subcellular localization of HNRNPH2, we expressed FLAG-epitope tagged hnRNPH2 WT and R212 non-binding variants (R212A, R212N and disease variant R212T), in addition to permissive mutant R212K in HeLa cells at basal conditions (Figure 3A-D). Following disassembly of the polysome after initiation of the integrated stress response, IDR-containing RNA-binding proteins are often found to relocalize to condensates known as stress granules.25,26 Disease-associated mutations that disrupt the nucleocytoplasmic ratio (e.g. NLS mutations) can worsen the phenotype by compromising the interactions with their nuclear transport receptors.27,28 Karyopherin-βs play a crucial role in disaggregating cytoplasmic accumulated proteins and restoring nuclear localization.29 The relocalization of cytoplasmic RNA-binding proteins to these puncta facilitates visualization of the redistribution of proteins from nucleus to cytoplasm, thus we also accessed the localization of HNRNPH2 after exposure to 30 minutes of sodium arsenite (Figure 3E-H). As previously observed20, the R212T variant shows increased cytoplasmic accumulation at basal conditions as assessed through immunofluorescent imaging (Figure 3A), direct measurement of the increase in % of cytoplasmic signal (Figure 3B) and decrease in the nucleocytoplasmic ratio (Figure 3C). There is minimal correlation between localization to the cytoplasm and hnRNPH2 expression levels indicating that accumulation in the cytoplasm is independent of expression level for all variants of hnRNPH2 (Figure 3D). Upon sodium arsenite treatment, the HNRNPH2 R212T variant accumulates in the cytoplasm and localizes to stress granules (Figure 3E-H). The Kapβ2-binding impaired R212A and R212N mutants have similar cytoplasmic accumulation to the disease mutant at both basal and stress conditions, whereas the R212K mutant localization is not significantly different from that of wild type protein, consistent with its still-substantial pull-down of Kapβ2 (Figures 2 and 3). Moreover, stress granule-associated HNRNPH2 signals were significantly higher in cells expressing R212T, R212A, and R212N mutants, but not in R212K, compared to WT (Figure S5), suggesting that these mutants not only have impaired nuclear import, but also accumulate more in stress granules under stress conditions. Together, the in vitro and in vivo experiments show that this epitope 4 is critical for HNRNPH2 PY-NLS to bind Kapβ2 and for nuclear import.

Figure 3. Epitope 4 of the PY-NLS regulates nuclear transport of HNRNPH2 in HeLa cells.

(A-D) HeLa cells were transfected with indicated FLAG-tagged full-length HNRNPH2 WT or mutants for 48 hrs. (A) Representative images from cells that were fixed, stained, and visualized with anti-FLAG (green) and anti-PABP (magenta) antibodies. Nucleus was visualized with DAPI (blue). Scale bar, 10 μm. (B) Quantification of the percentage of cytoplasmic FLAG-epitope tagged signal, or (C) the nucleocytoplasmic ratio (nuclear/cytoplasmic) from n=30 cells per condition from (A). Error bars represent mean ± s.d. (D) % cytosolic signal relative to the total expression/fluorescent signal for individual cells. R2 values show the absence of correlation between expression levels and cytosolic signal. *P=0.0391, ****P<0.0001 by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. (E-H) As in (A-D), but 48 hrs post-transfection, HeLa cells were treated with 0.5 mM NaAsO2 for 30 min. ns = not significant. See also Figure S5.

In summary, Kapβ2-HNRNPH2 interactions are dominated by strong epitopes 2 (R206) and 3 (209PY210), as well as a strong new epitope 4 at 212RP213. Mutations to all five residues within the three epitopes of the HNRNPH2 PY-NLS impair Kapβ2-mediated import and are found in patients with HNRNPH2-related X-linked neurodevelopmental disorder.

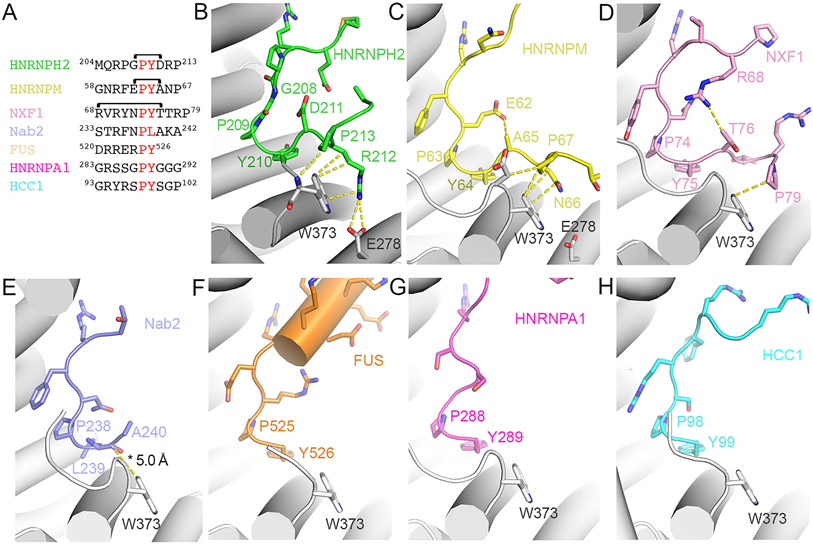

Comparison of HNRNPH2 Epitope 4 with epitopes of other PY-NLSs

We examined whether epitope 4 is found in other PY-NLSs. Of the structures of Kapβ2 bound to PY-NLSs often different cargos in the PDB10-12,21,23,24, only the Kapβ2-bound PY-NLSs of HNRNPM, NXF1 and Nab2 adopt conformations where residues C-terminal of the PY or homologous PL motifs come close to Kapβ2 (Figure 4A-E). Residues 66NP67 of HNRNPM and residue P79 of NXF1 occupy the same positions as HNRNPH2 212RP213 and make similar contacts with Kapβ2, especially with residue W373 (Figure 4B-D). Nab2 residues 239-240 are positioned slightly further away from Kapβ2, too far for contacts (Figure 4E).11,21,23 Residues C-terminal of the PY motifs of other PY-NLSs are either flexible and not modeled, or the PY residues are the C-termini of the cargo proteins (Figure 4F-H).

Figure 4. Interactions of Kapβ2 with the C-terminal portions of diverse PY-NLSs.

(A) Sequences of the C-terminal regions of PY-NLSs from HNRNPH2 (green), HNRNPM (yellow), NXF1 (pink), Nab2 (purple), FUS (orange), HNRNPA1 (magenta) and HCC1 (cyan). Brackets indicate intramolecular interactions between residue pairs. Epitope 3 (PY) is in red. (B-H) Interactions between Kapβ2 and PY-NLS residues C-terminal the PY motifs of HNRNPH2 (B), HNRNPM (PDBID 2OT8, C), NXF1 (PDBID 2Z5K, D), Nab2 (PDBID 4JLQ, E), FUS (PDBID 4FDD, F), HNRNPA1 (PDBID 2H4M, G) and HCC1 (PDBID 4OO6, H), are shown with dashed lines (interactions are < 4.0 Å except when marked with an asterisk *).

Many contacts of the HNRNPH2 epitope 4 are with residue W373 of Kapβ2 and almost all contacts of the epitopes 4 of HNRNPM and NXF1 are with W373 (Figure 4B-D). However, while Kapβ2 W373A mutation decreased HNRNPH2-binding substantially (KD 6.1 μM for Kapβ2(W373A) vs KD 50 nM for WT Kapβ2), the same Kapβ2 mutation did not affect HNRNPM PY-NLS binding (KD 4.5 nM for Kapβ2(W373A) vs KD 9 nM for WT Kapβ2) (Table 1 and Figure 2C, S4E and F). These results suggest that, in contrast to the strong epitope 4 of the HNRNPH2 PY-NLS, the epitope 4 of HNRNPM contributes little binding energy for Kapβ2 interactions. On the other hand, mutagenesis of NXF1 residues 76-80 (76TTRPN80) to alanines by Zhang et al. decreased Kapβ2-binding somewhat but still pulled-down substantial amounts Kapβ2, suggesting that the epitope 4 of NXF1 is likely intermediate in its contribution to total binding energy.30 Like PY-NLS epitopes 1, 2 and 3, all of which can have variable contributions to total binding energies in different PY-NLSs, epitopes 4 are similarly variable.7,11,12

We compared the structures of Kapβ2-bound epitopes 4 of HNRNPH2 (206RPGPYDRP213; epitope 4 underlined), HNRNPM (60RFEPYANP67) and NXF1 (68RVRYNPYTTRP79) to rationalize the variable epitopes 4. All three sequences share a proline two or three residues C-terminal of the PY-motif, and the residues between this C-terminal proline and the PY-motif interact with Kapβ2. 212RP213 of HNRNPH2 makes many contacts with Kapβ2 W373, with R212 participating in electrostatic interactions. By comparison, HNRNPM 66NP67 makes fewer contacts with Kapβ2 W373 and no electrostatic interactions. On the other hand, there are three residues between the PY-motif and the C-terminal proline (P79) of NXF1, positioning 78RP79 further away from Kapβ2 W373 and resulting in very few contacts, which may explain a weaker epitope 4.30 Having two residues between the PY and the C-terminal proline appears optimal for positioning the side chain that precedes the latter to contact Kapβ2 W373.

All three PY-NLS chains of HNRNPH2, HNRNPM and NXF1 make turns after the PY-motifs that are seemingly stabilized by intramolecular interactions. The D211 side chain of HNRNPH2 makes intramolecular polar interactions with G208 (Figure 4B). The T76 side chain of NXF1 also likely makes a polar intramolecular contact with R68 side chain (Figure 4D). The short A65 side chain of HNRNPM makes intramolecular Van der Waals contact with E62, but this non-polar interaction may not be optimal, and together with the lack of contacts between 66NP67 with Kapβ2 may make epitope 4 of HNRNPM weak (Figure 4C, S4E and F and Table 1). Nevertheless, intramolecular contacts are likely important to position epitopes 4 to interact with Kapβ2.

Based on the common characteristics of the interactions between Kapβ2 and the epitopes 4 of HNRNPH2, HNRNPM and NXF1, we propose a consensus sequence {G}-X(0,1)-ξ-[PA] that describes a PY-NLS epitope 4 that immediately follows the PY-motif. {G} is for any amino acid except glycine, which has no side chain to make intramolecular interactions; X(0,1) is for no amino acid or any amino acid; ξ is for hydrophilic amino acid and [PA] is for proline or alanine. A more stringent ξ-[RKH]-P consensus (ξ for hydrophilic amino acid; [RKH] for R, K or H), based on the structural and mutagenic studies of HNRNPH2, may describe an epitope 4 that contributes strongly to total binding energy of the PY-NLS. This strong epitope 4 consensus sequence accounts for possible polar intramolecular interaction made by the first amino acid of the consensus, electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions to Kapβ2 residues E278 and W373 by a basic side chain in the second position and favorable spacing between the PY-motif and the epitope 4 proline.

Prevalence of epitope 4 in known PY-NLSs

We show PY-NLS sequences for which Kapβ2-bound structures are available and the sequences of close paralogs in Figure 5A. We also examined the sequences of other PY-NLSs that were reported to bind Kapβ2 for the predicted strong (ξ-[R/K/H]-P) or likely weaker ({G}-X(0,1)-ξ-[PA]) epitope 4 , but we found none (Figure 5B).12,19,31-43 If we further relax the consensus to allow glycine in the first position (eliminating intramolecular interaction), we found only three PY-NLSs with sequences that barely passes for epitope 4. Therefore, of the 40 PY-NLS sequences analyzed in Figure 5A and B, strong epitopes 4 are found only in HNRNPH2 and close paralogs HNRNPH1 and HNRNPF (Figure 5A). If the PY-NLS epitope 4 is uncommonly used in Kapβ2 cargos, we expect that its binding site W373 is also not often used for cargo-binding.

Figure 5. PY-NLS sequences and their Kapβ2-binding epitopes.

(A) Sequences of PY-NLSs for which structures are available bound to Kapβ2 and the sequences of their close paralogs. The residues of epitopes 1 observed in the structures are colored green and those of epitopes 2 and 3 are colored red. Observed/predicted epitopes 4 are colored blue, with energetically strong epitopes 4 in bold. Kapβ2 tryptophan residues that contact these epitopes are indicated. (B) Previously reported PY-NLS sequences. Epitopes 2 and 3 are in red, and three stretches of 3-4 amino acids that partially match the epitope 4 consensus are in blue. (C) Aligned structures of Kapβ2(gray)•HNRNPH2(green) and Kapβ2(pink)•HNRNPA1(magenta) (PDBID 2H4M).12

Examination of Kapβ2-PY-NLS structures and the distributions of binding energies across the PY-NLSs also suggests that epitope 1 (N-terminal basic/hydrophobic motif) is rarely strong.7,10,12,44 Epitope 1 is not modeled in many structures and of the ones resolved structurally, the epitope is strong only in HNRNPA1 and are weak in HNRNPM and FUS (Figure 5A).10,11 In contrast, epitopes 2 and 3, which make up the C-terminal R-X2-3-P-Y/ϕ motif (ϕ is hydrophobic), are often used and the PY dipeptides often contribute substantially to Kapβ2-binding.7,10,11

PY-NLS-binding Kapβ2 tryptophan residues and their roles in disease

We previously noted that epitopes 1 of PY-NLSs contact W730 on Kapβ2 helix h16b, and epitopes 3 contact W460 on helix h10b (Figure 5A and C).12 The WW/AA mutant of Kapβ2, in which W460 and W730 are mutated to alanines, is commonly used to test cargo-binding.12,29,45 Epitopes 4 of HNRNPH2, HNRNPM and NXF1 contact W373, which is immediately N-terminal of helix h8b (Figure 4 and 5C). A series of three tryptophan residues, W373, W460 and W730, arrayed across the concave surface of the C-terminal half of Kapβ2 mediate hydrophobic interactions with three separate epitopes across the peptide chains of PY-NLSs. The array of tryptophan residues binding across an NLS is also used in lmportin-α binding to classical-NLSs where an array of tryptophan side chains on neighboring Armadillo repeats of lmportin-α make hydrophobic interactions with the array of aliphatic moieties of basic NLS side chains.46-48

Our assessment that epitopes 1 and 4 are used sparsely in Kapβ2 cargos is interesting and potentially useful in the context of the recent report that identified Kapβ2b/TNPO2 variants in patients with neurodevelopmental abnormalities.49 Many studies have shown that close paralogs Kapβ2 and Kapβ2b import almost the same set of cargos.2,50-53 In pediatric patients with neurodevelopmental abnormalities, the variant site at W370 of Kapβ2b (homologous to Kapβ2 W373; the epitope 4 binding site) is either arginine or cysteine, and the variant site at W727 (homologous to Kapβ2 W730; binds epitope 1) is cysteine (Figure 5A).49 Since epitope 4 is uncommonly used in known PY-NLSs and strong epitopes 4 so far are found only in the HNRNPH/F family members (Figure 5A and B), the W370R and W370C Kapβ2b variants may be defective in importing only a small subset of PY-NLS containing cargos including HNRNPH2, HNRNPH1 and HNRNPF, whose epitopes 4 are critical for Kapβ2- and/or Kapβ2b-binding. Nuclear import defects that result from Kapβ2b W370R and W370C in neurodevelopmental abnormalities patients may be related to those in HNRNPH2-related X-linked neurodevelopmental disorders. Future work to determine if HNRNPH2/H1/F and/or other cargos are mislocalized by Kapβ2b variants in cells will be important to understand if and how altered Kapβ2b-mediated nuclear import results in neurodevelopmental abnormalities.

Conclusion

The structure of the HNRNPH2 PY-NLS bound to Kapβ2 shows an NLS that spans residues 204-215. Epitope 1 or the N-terminal hydrophobic/basic motif of the PY-NLS is either missing or weak and therefore not persistently bound to Kapβ2. Instead, the PY-NLS of HNRNPH2 consists of energetically strong epitopes 2 (R206), 3 (209PY210) and a newly defined epitope 4 (211DRP213). Mutations at each of these epitopes, corresponding to different pathogenic variants in HNRNPH2-related X-linked neurodevelopmental disorders, decrease binding affinities for Kapβ2 substantially, explaining their mislocalization to the cytoplasm of cells. Strong epitopes 4 are not common in Kapβ2 cargos; they are so far found only in HNRNPH2 and its close paralogs HNRNPH1 and HNRNPF. Epitope 4 makes many interactions with Kapβ2 W373, which corresponds to a site of pathological variants of the close paralog Kapβ2b/TNPO2 (W370) that cause neurodevelopmental abnormalities, pointing to a pathological mechanism that may be very similar to that of the HNRNPH2-related X-linked neurodevelopmental disorders.

STAR Methods

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Yuh Min Chook (yuhmin.chook@utsouthwestern.edu).

Materials availability

All reagents generated in this study are available from the lead contact.

Data and code availability

Standardized cryo-EM data have been deposited in the PDB and EMDB and are publicly available as of the date of publication. The PDB and EMDB accession numbers are provided in the key resources table. Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request. This paper does not report original code.

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Mouse monoclonal anti-FLAG | Sigma-Aldrich | #F1804 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-PABP | Abcam | #ab21060 |

| Alexa Fluor 488 secondary antibody | Invitrogen | #A21202 |

| Alexa Fluor 647 secondary antibody | Invitrogen | #A31573 |

| Bacterial and virus strains | ||

| BL21-Gold (DE3) E. coli | Agilent | #230132 |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| IPTG | Goldbio | #12481C |

| Tris HCl | RPI | #T60040 |

| NaCl | RPI | #S23020 |

| EDTA | RPI | #E57020 |

| β-mercaptoethanol | Sigma-Aldrich | #M6250 |

| Glycerol | Sigma-Aldrich | #G7893 |

| Benzamidine | Sigma-Aldrich | #434760 |

| Leupeptin | Alfa Aesar | #J61188 |

| AEBSF | Goldbio | #A540 |

| Glutathione | Sigma-Aldrich | #G4251 |

| HEPES | Goldbio | #H400 |

| cOmplete protease inhibitor cocktail | Sigma-Aldrich | #05056489001 |

| Maltose | Sigma-Aldrich | #M5885 |

| Imidazole | Sigma-Aldrich | #79227 |

| Glutaraldehyde | Electron Microscopy Sciences | #16100 |

| NP-40 | Biovision | #S226 |

| ViaFect | Promega | #E4981 |

| Sodium Arsenite | Sigma-Aldrich | #S7400 |

| Paraformaldehyde | Electron Microscopy Sciences | #15710 |

| Triton-X | Electron Microscopy Sciences | #22140 |

| BSA | Sigma-Aldrich | # A8806 |

| DAPI | Invitrogen | #P36931 |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| ADAM-CellT | NanoEntek Inc. | #ADAM-CellT |

| Deposited data | ||

| Kapβ2-HNRNPH2(103-225) | This study | PDB: 8SGH EMDB: EMD-40455 |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| See Table S1 | This study | N/A |

| Experimental models: Cell lines | ||

| HeLa cells | ATCC | CCL-2 |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| pGex-tev-Kapβ2 | Chook and Blobel, 199954 | N/A |

| pGex-tev-Kapβ2(W373A) | This study | N/A |

| pHis6-Mal-tev-HNRNPH2 fragments and variants | This study | N/A |

| pGex-tev-HNRNPH2 fragments | This study | N/A |

| pMal-tev-HNRNPM PY-NLS | Cansizoglu et al., 200711 | N/A |

| pGex-tev-M9M | Cansizoglu et al., 200711 | N/A |

| pcDNA3.1(+) FLAG-tagged HNRNPH2 full length WT and R212T | Korff et al., 202320 | N/A |

| pcDNA3.1(+) FLAG-tagged HNRNPH2 R212A, R212N, R212K | This study | N/A |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| NITPIC | Keller et al., 201255 | http://biophysics.swmed.edu/MBR/software.html |

| SEDPHAT | Houtman et al., 200756 | http://www.analyticalultracentrifugation.com/sedphat/ |

| GUSSI | Brautigam, 201557 | http://biophysics.swmed.edu/MBR/software.html |

| SerialEM | Mastronarde, 200558 | http://www2.mrc-lmb.cam.ac.uk/personal/pemsley/coot/ |

| cryoSPARC | Punjani et al.,201759 | https://cryosparc.com/ |

| UCSF Chimera | Petterson et al., 200460 | https://www.cgl.ucsf.edu/chimera/ |

| Phenix | Adams et al., 201061 | https://phenix-online.org/ |

| Coot | Emsley and Cowtan, 200462 | http://www2.mrc-lmb.cam.ac.uk/personal/pemsley/coot/ |

| ISOLDE | Croll, 201863 | https://isolde.cimr.cam.ac.uk/what-isolde/ |

| UCSF ChimeraX | Goddard et al., 201864 | https://www.cgl.ucsf.edu/chimerax/ |

| PyMOL ver2.5 | Schrüdinger | https://pymol.org/2/ |

| ImageJ | Schneider et al., 201265 | https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/download.html |

| GraphPad Prism | https://www.graphpad.com/features | |

| ilastik | Berg et al., 201966 | https://www.ilastik.org/ |

| cellpose | Stringer et al., 202067 | https://www.cellpose.org/ |

| CellProfiler | Carpenter et al., 200668 | https://cellprofiler.org/ |

Experimental model and subject details

Bacterial strains and cell lines

BL21-Gold (DE3) E. coli cells were purchased from Agilient Technologies (#230132) and were used to purify all recombinant proteins. HeLa cells were purchased from ATCC (CCL-2).

Method details

Protein expression and purification

The plasmid to overexpress GST-Kapβ2 was as described in previous work.54 Various truncation variants of HNRNPH2 described in this work were subcloned into pMal-TEV with or without His6 inserted before the MBP, or into the pGex-tev vector as for the GST-Kapβ2 overexpression plasmid. Some single amino acid mutants were generated by site-directed mutagenesis and others were purchased synthesized (GenScript).

GST-Kapβ2 was overexpressed in BL21-Gold (DE3) E. coli cells and expression was induced with 0.5 mM isopropyl-β-d-1-thiogalactoside (IPTG) for 12 h at 25 °C. The bacterial cells were harvested by centrifugation, resuspended in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 15% v/v glycerol, 1 mM benzamidine, 10 μg/mL leupeptin and 50 μg/mL AEBSF and then lysed with the EmulsiFlex-C5 cell homogenizer (Avestin, Ottawa, Canada). GST-Kapβ2 proteins were purified by affinity chromatography using Glutathione Sepharose 4B beads (GSH; #17075604, Cytiva). For ITC analysis and cryo-EM structure determination, the GST tag was removed by adding TEV protease to GST-Kapβ2 on the GSH column. Kapβ2 released from the GSH beads was further purified by anion exchange chromatography followed by size-exclusion chromatography (Superdex 200 increase, Cytiva). For pull-down binding assays, GST-Kapβ2 was eluted from GSH beads with 20mM glutathione at pH 6.5 and the protein was further purified by anion exchange followed by size-exclusion chromatography (Superdex 200 Increase).

MBP-HNRNPH2 and His6-MBP-HNRNPH2 proteins were overexpressed in BL21-Gold (DE3) E. coli cells (induced with 0.5 mM IPTG for 16 h at 20 °C). The bacteria cells were lysed in buffer containing 50 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 1.5 M NaCl, 10% v/v glycerol, 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol and cOmplete protease inhibitor cocktail. The high salt is used to disrupt association with nucleic acids. MBP-HNRNPH2 proteins were purified by affinity chromatography using amylose resin (#E8021, New England BioLabs) and eluted with buffer containing 20 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM DTT, 10% v/v glycerol, and 20 mM maltose. His6-MBP-HNRNPH2 proteins were first purified using Ni-NTA Agarose (#30230, Giagen) and eluted with buffer containing 250 mM imidazole pH 7.8, 10 mM NaCl, 10% v/v glycerol, 2mM β-mercaptoethanol. Both MBP-HNRNPH2 and His6-MBP-HNRNPH2 proteins were further purified by size-exclusion chromatography (Superdex 200 Increase).

Pull-down binding assays for Kapβ2 binding to immobilized GST-HNRNPH2 proteins

E. coli (BL21-Gold) transformed with pGEX-tev plasmids expressing GST-HNRNPH2 proteins were grown to OD600 0.6. Protein expression was then induced with 0.5 mM IPTG for 4 hours at 37°C. Cells were harvested by centrifugation, resuspended in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 2 mM DTT, 15% glycerol, 1 mM benzamidine, 10 μg/mL leupeptin and 50 μg/mL AEBSF) and lysed by sonication. The lysate was centrifuged and the supernatant containing GST-HNRNPH2 proteins added to Glutathione Sepharose 4B beads. The solution was spun down to obtain bead bed with immobilized GST-HNRNPH2 proteins, which was then washed with 1ml of lysis buffer. 50 μl of bead slurry containing ~60 μg immobilized GST-HNRNPH2 proteins were then incubated with 8 μM Kapβ2 in 100 μl total volume for 30 min at 4°C and then washed three times with 1 ml of lysis buffer. Proteins bound on the beads were eluted by boiling in SDS sample buffer and visualized by Coomassie staining of SDS-PAGE gels.

Isothermal titration calorimetry

Kapβ2 and MBP-HNRNPH2 proteins were dialyzed into ITC buffer (20 mM Tris pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 10% v/v glycerol, 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol). ITC experiments were performed in a MicroCal PEAQ-ITC (Malvern Panalytical, Worcestershire, UK) calorimeter; it has a stirred 206.2 μL reaction cell held at 20 °C. The first injections were 0.5 μL, followed by twenty 1.9 μL injections with a stirring rate of 750 rpm. Kapβ2 was used at 10 μM in the ITC cell; 100-350 μM MBP-HNRNPH2 proteins were used in the syringe. All ITC experiments were performed in duplicate except when noted. ITC data were integrated and baseline corrected using NITPIC.55 The integrated data were globally analyzed in SEDPHAT56 using a model considering a single class of binding sites. Thermogram and binding figures were plotted in GUSSI.57

Cryo-EM sample and grid preparation

Kapβ2 and HNRNPH2(103-225) were mixed at room temperature at 1:1.4 molar ratio, followed by a rapid addition of glutaraldehyde to a final concentration of 0.025% for 1 minute, and immediate injection to size-exclusion chromatography in a Superdex 200 Increase column. Fractions containing the crosslinked mixture were pooled, aliquoted and stored at −80°C for later use. Aliquots were diluted to a approximate concentration of 2.7 mg/mL in buffer containing 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 150 nM NaCl, 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol and 0.003125% [w/v] NP-40 to set up cryo-EM grids. 4 μL of Kapβ2*HNRNPH2 was applied to a 300 mesh copper grid (Quantifoil R1.2/1.3) that was glow-discharged using a PELCO easiGlow glow discharge apparatus at 30 mA/30 s on top of a metal grid holder (Ted Pella). Excess sample was blotted 3 s before plunge-freezing in a Vitrobot System (Thermo Fisher) at 4°C with 95% humidity.

Cryo-EM data collection and data processing

Cryo-EM data collection for the Kapβ2•HNRNPH2(103-225) complex was collected at the UT Southwestern Cryo-Electron Microscopy Facility on a Titan Krios at 300 kV with a Gatan K3 detector in correlated double sampling super-resolution mode at a magnification of 105,000x corresponding to a pixel size of 0.415 Å using an energy filter with slit width of 20 eV. Each movie was recorded for a total of 60 frames over 5.4 s with an exposure rate of 8 electrons/pixel/s. The datasets were collected using SerialEM58 software with a defocus range of −0.9 and −2.4 μm.

A total of 5,937 movies were collected for Kapβ2•HNRNPH2. The dataset was processed using cryoSPARC59 where it was first subjected to Patch Motion Correction and Patch CTF Estimation. The Blob Picker was implemented on 25 micrographs to pick all possible particles with little bias. This small set of particles were subjected to 2D Classification to generate 2D templates. A subset of templates was selected and used in Template Picker, resulting in 4,042,358 particles selected. 681,236 particles of Kapβ2•HNRNPH2 were selected after 14 rounds of 2D Classification and were then sorted into seven 3D classes using Ab-initio reconstruction followed by Heterogeneous Refinement. The 208,572 particles from one 3D class of the Kapβ2•HNRNPH2 complex were utilized for Non-uniform Refinement which yielded a 3.17 Å resolution map.

Cryo-EM model building, refinement, and analysis

The Kapβ2 and HNRNPH2 proteins were built using coordinates from the deposited structure PDB:2OT8. Model was roughly docked into the map using UCSF Chimera60 and then subjected to real-space refinement with global minimization and rigid body restraints on Phenix.61 The resulting models were then manually rebuilt and refined using Coot62, further corrected using ISOLDE63 on UCSF ChimeraX64, and subjected to more rounds of refinement in Phenix. UCSF ChimeraX and PyMOL version 2.5 were used for 3D structure analysis.

Cellular localization analysis of HNRNPH2 proteins

HeLa cells were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Cells were counted using ADAM-CellT, plated and transfected using ViaFect for transient overexpression according to the manufacturer’s instructions. HNRNPH2 was over-expressed using pcDNA3.1(+) FLAG-tagged HNRNPH2 WT and mutants as indicated.20 Mutants were generated by site directed mutagenesis of the WT plasmid.

HeLa cells were seeded on 4-well glass slides (Millipore). Forty-eight hours post transfection for overexpression, cells were stressed with 500 μM sodium arsenite for 30 min. Cells were then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100, and blocked in 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA). Primary antibodies used were mouse monoclonal anti-FLAG (1:1000, M2) and rabbit polyclonal anti-PABP (1:1000). For visualization, the appropriate host-specific Alexa Fluor 488 or 647 secondary antibodies were used. Slides were mounted using Prolong Gold Antifade Reagent with DAPI. Imaging was performed using a Yokogawa CSU W1 spinning disk attached to a Nikon Ti2 eclipse with a Photometrics Prime 95B camera using Nikon Elements software (version 5.21.02). The DAPI and PABP channels were used to segment the nucleus and cytoplasm using the freehand selection tool on ImageJ.65 Integrated intensity of the nucleus, and integrated cellular signal was quantified and background signal subtracted. Integrated cytoplasmic signal was calculated by subtracting the integrated nuclear signal from the integrated cell signal. Percent cytoplasmic signal was calculated by dividing the integrated cytoplasmic signal over the integrated cell signal. For automated analysis ilastik software66 was used to segment stress granules and the cell boundary was detected using cellpose software67, both using the PABP channel. The mean intensity of HNRNPH2 in stress granules and within the cell were calculated using a CellProfiler (Broad Institute) pipeline optimized for stress granule filtering and analysis.68

Quantification and Statistical Analysis

Details on statistical analysis and tests performed can be found in figure legends. Calculations were done by SEDPHAT for Figure 2, S1 and S4, cryoSPARC and Phenix for Figure S2 and performed in GraphPad Prism 9 for Figure 3 and S5.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

A 3.2 Å resolution cryo-EM structure of the Karyopherin-β2*HNRNPH2 PY-NLS complex

A new PY-NLS epitope 4 is delineated

Neurological disorder variant of Transportin-2 is binding site for PY-NLS epitope 4

Acknowledgements

We thank the Structural Biology Laboratory and the Cryo-EM Facility at UTSW, which are partially supported by grant RP170644 from the Cancer Prevention & Research Institute of Texas (CPRIT), for their assistance with cryo-EM data collection. We thank the Macromolecular Biophysics Resource at UTSW for training and use of their ITC resources. We thank James Messing and Alexandre Carisey for assistance with automated imaging analysis. This work was funded by NIGMS of NIH under Awards R35GM141461 (Y.M.C.), R01GM069909 (Y.M.C.), the Welch Foundation Grants I-1532 (Y.M.C.), support from the Alfred and Mabel Gilman Chair in Molecular Pharmacology and the Eugene McDermott Scholar in Biomedical Research (Y.M.C.), the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (J.P.T) and by NINDS of NIH under awards R35NS097974 (J.P.T) and F31NS120465 (A.G.).

Inclusion and diversity

One or more of the authors of this paper self-identifies as an underrepresented ethnic minority in their field of research or within their geographical location. One or more of the authors of this paper received support from a program designed to increase minority representation in their field of research.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of interests

JPT is a consultant for Nido Biosciences.

References

- 1.Gorlich D, and Kutay U (1999). Transport between the cell nucleus and the cytoplasm. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 15, 607–660. 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.15.1.607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guttinger S, Muhlhausser P, Koller-Eichhorn R, Brennecke J, and Kutay U (2004). Transportin2 functions as importin and mediates nuclear import of HuR. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101, 2918–2923. 10.1073/pnas.0400342101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tran EJ, Bolger TA, and Wente SR (2007). Snapshot: nuclear transport. Cell 131, 420. 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weis K (2003). Regulating access to the genome: nucleocytoplasmic transport throughout the cell cycle. Cell 112, 441–451. 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00082-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wing CE, Fung HYJ, and Chook YM (2022). Karyopherin-mediated nucleocytoplasmic transport. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 23, 307–328. 10.1038/s41580-021-00446-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chook YM, and Suel KE (2011). Nuclear import by karyopherin-betas: recognition and inhibition. Biochim Biophys Acta 1813, 1593–1606. 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2010.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Suel KE, Gu H, and Chook YM (2008). Modular organization and combinatorial energetics of proline-tyrosine nuclear localization signals. PLoS Biol 6, e137. 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dormann D, Rodde R, Edbauer D, Bentmann E, Fischer I, Hruscha A, Than ME, Mackenzie IR, Capell A, Schmid B, et al. (2010). ALS-associated fused in sarcoma (FUS) mutations disrupt Transportin-mediated nuclear import. EMBO J 29, 2841–2857. 10.1038/emboj.2010.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shorter J (2019). Phase separation of RNA-binding proteins in physiology and disease: An introduction to the JBC Reviews thematic series. J Biol Chem 294, 7113–7114. 10.1074/jbc.REV119.007944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang ZC, and Chook YM (2012). Structural and energetic basis of ALS-causing mutations in the atypical proline-tyrosine nuclear localization signal of the Fused in Sarcoma protein (FUS). Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109, 12017–12021. 10.1073/pnas.1207247109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cansizoglu AE, Lee BJ, Zhang ZC, Fontoura BM, and Chook YM (2007). Structure-based design of a pathway-specific nuclear import inhibitor. Nat Struct Mol Biol 14, 452–454. 10.1038/nsmb1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee BJ, Cansizoglu AE, Suel KE, Louis TH, Zhang Z, and Chook YM (2006). Rules for nuclear localization sequence recognition by karyopherin beta 2. Cell 126, 543–558. 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Soniat M, and Chook YM (2016). Karyopherin-beta2 Recognition of a PY-NLS Variant that Lacks the Proline-Tyrosine Motif. Structure 24, 1802–1809. 10.1016/j.str.2016.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bain JM, Cho MT, Telegrafi A, Wilson A, Brooks S, Botti C, Gowans G, Autullo LA, Krishnamurthy V, Willing MC, et al. (2016). Variants in HNRNPH2 on the X Chromosome Are Associated with a Neurodevelopmental Disorder in Females. Am J Hum Genet 99, 728–734. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.06.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bain JM, Thornburg O, Pan C, Rome-Martin D, Boyle L, Fan X, Devinsky O, Frye R, Hamp S, Keator CG, et al. (2021). Detailed Clinical and Psychological Phenotype of the X-linked HNRNPH2-Related Neurodevelopmental Disorder. Neurol Genet 7, e551. 10.1212/NXG.0000000000000551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pilch J, Koppolu AA, Walczak A, Murcia Pienkowski VA, Biernacka A, Skiba P, Machnik-Broncel J, Gasperowicz P, Kosinska J, Rydzanicz M, et al. (2018). Evidence for HNRNPH1 being another gene for Bain type syndromic mental retardation. Clin Genet 94, 381–385. 10.1111/cge.13410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reichert SC, Li R, S AT, van Jaarsveld RH, Massink MPG, van den Boogaard MH, Del Toro M, Rodriguez-Palmero A, Fourcade S, Schluter A, et al. (2020). HNRNPH1-related syndromic intellectual disability: Seven additional cases suggestive of a distinct syndromic neurodevelopmental syndrome. Clin Genet 98, 91–98. 10.1111/cge.13765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gonzalez A, Mannen T, Cagatay T, Fujiwara A, Matsumura H, Niesman AB, Brautigam CA, Chook YM, and Yoshizawa T (2021). Mechanism of karyopherin-beta2 binding and nuclear import of ALS variants FUS(P525L) and FUS(R495X). Sci Rep 11, 3754. 10.1038/s41598-021-83196-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van Dusen CM, Yee L, McNally LM, and McNally MT (2010). A glycine-rich domain of hnRNP H/F promotes nucleocytoplasmic shuttling and nuclear import through an interaction with transports 1. Mol Cell Biol 30, 2552–2562. 10.1128/MCB.00230-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Korff A, Yang X, O’Donovan K, Gonzalez A, Teubner BJW, Nakamura H, Messing J, Yang F, Carisey A, Wang Y-D, et al. (2023). A murine model of hnRNPH2-related neurodevelopmental disorder recapitulates clinical features of human disease and reveals a mechanism for genetic compensation of HNRNPH2. bioRxiv, 2022.2003.2017.484791. 10.1101/2022.03.17.484791. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Soniat M, Sampathkumar P, Collett G, Gizzi AS, Banu RN, Bhosle RC, Chamala S, Chowdhury S, Fiser A, Glenn AS, et al. (2013). Crystal structure of human Karyopherin beta2 bound to the PY-NLS of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Nab2. J Struct Funct Genomics 14, 31–35. 10.1007/s10969-013-9150-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jiou J, Shaffer JM, Bernades NE, Fung HYJ, Dias JK, D’Arcy S, and Chook YM (2023). Mechanism of RanGTP priming H2A-H2B release from Kap114 in an atypical RanGTP•Kap114•H2A-H2B complex. bioRxiv, 2022.2011.2022.517512. 10.1101/2022.11.22.517512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Imasaki T, Shimizu T, Hashimoto H, Hidaka Y, Kose S, Imamoto N, Yamada M, and Sato M (2007). Structural basis for substrate recognition and dissociation by human transports 1. Mol Cell 28, 57–67. 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huber FM, and Hoelz A (2017). Molecular basis for protection of ribosomal protein L4 from cellular degradation. Nat Commun 8, 14354. 10.1038/ncomms14354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Protter DSW, and Parker R (2016). Principles and Properties of Stress Granules. Trends Cell Biol 26, 668–679. 10.1016/j.tcb.2016.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Srimany A, Jayashree B, Krishnakumar S, Elchuri S, and Pradeep T (2015). Identification of effective substrates for the direct analysis of lipids from cell lines using desorption electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom 29, 349–356. 10.1002/rcm.7111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Naruse H, Ishiura H, Mitsui J, Date H, Takahashi Y, Matsukawa T, Tanaka M, Ishii A, Tamaoka A, Hokkoku K, et al. (2018). Molecular epidemiological study of familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in Japanese population by whole-exome sequencing and identification of novel HNRNPA1 mutation. Neurobiol Aging 61, 255 e259–255 e216. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2017.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vance C, Scotter EL, Nishimura AL, Troakes C, Mitchell JC, Kathe C, Urwin H, Manser C, Miller CC, Hortobagyi T, et al. (2013). ALS mutant FUS disrupts nuclear localization and sequesters wild-type FUS within cytoplasmic stress granules. Hum Mol Genet 22, 2676–2688. 10.1093/hmg/ddt117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guo L, Kim HJ, Wang H, Monaghan J, Freyermuth F, Sung JC, O'Donovan K, Fare CM, Diaz Z, Singh N, et al. (2018). Nuclear-Import Receptors Reverse Aberrant Phase Transitions of RNA-Binding Proteins with Prion-like Domains. Cell 173, 677–692 e620. 10.1016/j.cell.2018.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang ZC, Satterly N, Fontoura BM, and Chook YM (2011). Evolutionary development of redundant nuclear localization signals in the mRNA export factor NXF1. Mol Biol Cell 22, 4657–4668. 10.1091/mbc.E11-03-0222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Twyffels L, Wauquier C, Soin R, Decaestecker C, Gueydan C, and Kruys V (2013). A masked PY-NLS in Drosophila TIS11 and its mammalian homolog tristetraprolin. PLoS One 8, e71686. 10.1371/journal.pone.0071686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chai K, Wang Z, Pan Q, Tan J, Qiao W, and Liang C (2021). Effect of Different Nuclear Localization Signals on the Subcellular Localization and Anti-HIV-1 Function of the MxB Protein. Front Microbiol 12, 675201. 10.3389/fmicb.2021.675201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tanaka T, Kasai M, and Kobayashi S (2018). Mechanism responsible for inhibitory effect of indirubin 3'-oxime on anticancer agent-induced YB-1 nuclear translocation in HepG2 human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Exp Cell Res 370, 454–460. 10.1016/j.yexcr.2018.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shin SH, Lee EJ, Chun J, Hyun S, and Kang SS (2015). ULK2 Ser 1027 Phosphorylation by PKA Regulates Its Nuclear Localization Occurring through Karyopherin Beta 2 Recognition of a PY-NLS Motif. PLoS One 10, e0127784. 10.1371/journal.pone.0127784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang L, Li M, Cai M, Xing J, Wang S, and Zheng C (2012). A PY-nuclear localization signal is required for nuclear accumulation of HCMV UL79 protein. Med Microbiol Immunol 201, 381–387. 10.1007/s00430-012-0243-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang T, Ba X, Zhang X, Zhang N, Wang G, Bai B, Li T, Zhao J, Zhao Y, Yu Y, and Wang B (2022). Nuclear import of PTPN18 inhibits breast cancer metastasis mediated by MVP and importin beta2. Cell Death Dis 13, 720. 10.1038/s41419-022-05167-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang B, Chen J, and Teng Y (2021). TNPO1-Mediated Nuclear Import of FUBP1 Contributes to Tumor Immune Evasion by Increasing NRP1 Expression in Cervical Cancer. J Immunol Res 2021, 9994004. 10.1155/2021/9994004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen A, Akhshi TK, Lavoie BD, and Wilde A (2015). Importin beta2 Mediates the Spatio-temporal Regulation of Anillin through a Noncanonical Nuclear Localization Signal. J Biol Chem 290, 13500–13509. 10.1074/jbc.M115.649160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gonatopoulos-Pournatzis T, and Cowling VH (2014). RAM function is dependent on Kapbeta2-mediated nuclear entry. Biochem J 457, 473–484. 10.1042/BJ20131359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Calado A, Kutay U, Kuhn U, Wahle E, and Carmo-Fonseca M (2000). Deciphering the cellular pathway for transport of poly(A)-binding protein II. RNA 6, 245–256. 10.1017/s1355838200991908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mallet PL, and Bachand F (2013). A proline-tyrosine nuclear localization signal (PY-NLS) is required for the nuclear import of fission yeast PAB2, but not of human PABPN1. Traffic 14, 282–294. 10.1111/tra.12036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mordovkina DA, Kim ER, Buldakov IA, Sorokin AV, Eliseeva IA, Lyabin DN, and Ovchinnikov LP (2016). Transportin-1-dependent YB-1 nuclear import. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 480, 629–634. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.10.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Leemann-Zakaryan RP, Pahlich S, Grossenbacher D, and Gehring H (2011). Tyrosine Phosphorylation in the C-Terminal Nuclear Localization and Retention Signal (C-NLS) of the EWS Protein. Sarcoma 2011, 218483. 10.1155/2011/218483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Soniat M, Cagatay T, and Chook YM (2016). Recognition Elements in the Histone H3 and H4 Tails for Seven Different Importins. J Biol Chem 291, 21171–21183. 10.1074/jbc.M116.730218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Barraud P, Banerjee S, Mohamed WI, Jantsch MF, and Allain FH (2014). A bimodular nuclear localization signal assembled via an extended double-stranded RNA-binding domain acts as an RNA-sensing signal for transportin 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111, E1852–1861. 10.1073/pnas.1323698111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Soniat M, and Chook YM (2015). Nuclear localization signals for four distinct karyopherin-beta nuclear import systems. Biochem J 468, 353–362. 10.1042/BJ20150368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lott K, and Cingolani G (2011). The importin beta binding domain as a master regulator of nucleocytoplasmic transport. Biochim Biophys Acta 1813, 1578–1592. 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2010.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Conti E, Uy M, Leighton L, Blobel G, and Kuriyan J (1998). Crystallographic analysis of the recognition of a nuclear localization signal by the nuclear import factor karyopherin alpha. Cell 94, 193–204. 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81419-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Goodman LD, Cope H, Nil Z, Ravenscroft TA, Charng WL, Lu S, Tien AC, Pfundt R, Koolen DA, Haaxma CA, et al. (2021). TNPO2 variants associate with human developmental delays, neurologic deficits, and dysmorphic features and alter TNPO2 activity in Drosophila. Am J Hum Genet 108, 1669–1691. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2021.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kimura M, Morinaka Y, Imai K, Kose S, Horton P, and Imamoto N (2017). Extensive cargo identification reveals distinct biological roles of the 12 importin pathways. Elife 6. 10.7554/eLife.21184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Twyffels L, Gueydan C, and Kruys V (2014). Transportin-1 and Transportin-2: protein nuclear import and beyond. FEBS Lett 588, 1857–1868. 10.1016/j.febslet.2014.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mackmull MT, Klaus B, Heinze I, Chokkalingam M, Beyer A, Russell RB, Ori A, and Beck M (2017). Landscape of nuclear transport receptor cargo specificity. Mol Syst Biol 13, 962. 10.15252/msb.20177608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rebane A, Aab A, and Steitz JA (2004). Transportins 1 and 2 are redundant nuclear import factors for hnRNP A1 and HuR. RNA 10, 590–599. 10.1261/rna.5224304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chook YM, and Blobel G (1999). Structure of the nuclear transport complex karyopherin-beta2-Ran x GppNHp. Nature 399, 230–237. 10.1038/20375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Keller S, Vargas C, Zhao H, Piszczek G, Brautigam CA, and Schuck P (2012). High-precision isothermal titration calorimetry with automated peak-shape analysis. Anal Chem 84, 5066–5073. 10.1021/ac3007522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Houtman JC, Brown PH, Bowden B, Yamaguchi H, Appella E, Samelson LE, and Schuck P (2007). Studying multisite binary and ternary protein interactions by global analysis of isothermal titration calorimetry data in SEDPHAT: application to adaptor protein complexes in cell signaling. Protein Sci 16, 30–42. 10.1110/ps.062558507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Brautigam CA (2015). Calculations and Publication-Quality Illustrations for Analytical Ultracentrifugation Data. Methods Enzymol 562, 109–133. 10.1016/bs.mie.2015.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mastronarde DN (2005). Automated electron microscope tomography using robust prediction of specimen movements. J Struct Biol 152, 36–51. 10.1016/j.jsb.2005.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Punjani A, Rubinstein JL, Fleet DJ, and Brubaker MA (2017). cryoSPARC: algorithms for rapid unsupervised cryo-EM structure determination. Nat Methods 14, 290–296. 10.1038/nmeth.4169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, Couch GS, Greenblatt DM, Meng EC, and Ferrin TE (2004). UCSF Chimera--a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem 25, 1605–1612. 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Adams PD, Afonine PV, Bunkoczi G, Chen VB, Davis IW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Hung LW, Kapral GJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, et al. (2010). PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 66, 213–221. 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Emsley P, and Cowtan K (2004). Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 60, 2126–2132. 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Croll TI (2018). ISOLDE: a physically realistic environment for model building into low-resolution electron-density maps. Acta Crystallogr D Struct Biol 74, 519–530. 10.1107/S2059798318002425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Goddard TD, Huang CC, Meng EC, Pettersen EF, Couch GS, Morris JH, and Ferrin TE (2018). UCSF ChimeraX: Meeting modern challenges in visualization and analysis. Protein Sci 27, 14–25. 10.1002/pro.3235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Schneider CA, Rasband WS, and Eliceiri KW (2012). NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat Methods 9, 671–675. 10.1038/nmeth.2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Berg S, Kutra D, Kroeger T, Straehle CN, Kausler BX, Haubold C, Schiegg M, Ales J, Beier T, Rudy M, et al. (2019). ilastik: interactive machine learning for (bio)image analysis. Nat Methods 16, 1226–1232. 10.1038/s41592-019-0582-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Stringer C, Wang T, Michaelos M, and Pachitariu M (2021). Cellpose: a generalist algorithm for cellular segmentation. Nat Methods 18, 100–106. 10.1038/s41592-020-01018-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Carpenter AE, Jones TR, Lamprecht MR, Clarke C, Kang IH, Friman O, Guertin DA, Chang JH, Lindquist RA, Moffat J, et al. (2006). CellProfiler: image analysis software for identifying and quantifying cell phenotypes. Genome Biol 7, R100. 10.1186/gb-2006-7-10-r100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Standardized cryo-EM data have been deposited in the PDB and EMDB and are publicly available as of the date of publication. The PDB and EMDB accession numbers are provided in the key resources table. Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request. This paper does not report original code.

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Mouse monoclonal anti-FLAG | Sigma-Aldrich | #F1804 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-PABP | Abcam | #ab21060 |

| Alexa Fluor 488 secondary antibody | Invitrogen | #A21202 |

| Alexa Fluor 647 secondary antibody | Invitrogen | #A31573 |

| Bacterial and virus strains | ||

| BL21-Gold (DE3) E. coli | Agilent | #230132 |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| IPTG | Goldbio | #12481C |

| Tris HCl | RPI | #T60040 |

| NaCl | RPI | #S23020 |

| EDTA | RPI | #E57020 |

| β-mercaptoethanol | Sigma-Aldrich | #M6250 |

| Glycerol | Sigma-Aldrich | #G7893 |

| Benzamidine | Sigma-Aldrich | #434760 |

| Leupeptin | Alfa Aesar | #J61188 |

| AEBSF | Goldbio | #A540 |

| Glutathione | Sigma-Aldrich | #G4251 |

| HEPES | Goldbio | #H400 |

| cOmplete protease inhibitor cocktail | Sigma-Aldrich | #05056489001 |

| Maltose | Sigma-Aldrich | #M5885 |

| Imidazole | Sigma-Aldrich | #79227 |

| Glutaraldehyde | Electron Microscopy Sciences | #16100 |

| NP-40 | Biovision | #S226 |

| ViaFect | Promega | #E4981 |

| Sodium Arsenite | Sigma-Aldrich | #S7400 |

| Paraformaldehyde | Electron Microscopy Sciences | #15710 |

| Triton-X | Electron Microscopy Sciences | #22140 |

| BSA | Sigma-Aldrich | # A8806 |

| DAPI | Invitrogen | #P36931 |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| ADAM-CellT | NanoEntek Inc. | #ADAM-CellT |

| Deposited data | ||

| Kapβ2-HNRNPH2(103-225) | This study | PDB: 8SGH EMDB: EMD-40455 |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| See Table S1 | This study | N/A |

| Experimental models: Cell lines | ||

| HeLa cells | ATCC | CCL-2 |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| pGex-tev-Kapβ2 | Chook and Blobel, 199954 | N/A |

| pGex-tev-Kapβ2(W373A) | This study | N/A |

| pHis6-Mal-tev-HNRNPH2 fragments and variants | This study | N/A |

| pGex-tev-HNRNPH2 fragments | This study | N/A |

| pMal-tev-HNRNPM PY-NLS | Cansizoglu et al., 200711 | N/A |

| pGex-tev-M9M | Cansizoglu et al., 200711 | N/A |

| pcDNA3.1(+) FLAG-tagged HNRNPH2 full length WT and R212T | Korff et al., 202320 | N/A |

| pcDNA3.1(+) FLAG-tagged HNRNPH2 R212A, R212N, R212K | This study | N/A |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| NITPIC | Keller et al., 201255 | http://biophysics.swmed.edu/MBR/software.html |

| SEDPHAT | Houtman et al., 200756 | http://www.analyticalultracentrifugation.com/sedphat/ |

| GUSSI | Brautigam, 201557 | http://biophysics.swmed.edu/MBR/software.html |

| SerialEM | Mastronarde, 200558 | http://www2.mrc-lmb.cam.ac.uk/personal/pemsley/coot/ |

| cryoSPARC | Punjani et al.,201759 | https://cryosparc.com/ |

| UCSF Chimera | Petterson et al., 200460 | https://www.cgl.ucsf.edu/chimera/ |

| Phenix | Adams et al., 201061 | https://phenix-online.org/ |

| Coot | Emsley and Cowtan, 200462 | http://www2.mrc-lmb.cam.ac.uk/personal/pemsley/coot/ |

| ISOLDE | Croll, 201863 | https://isolde.cimr.cam.ac.uk/what-isolde/ |

| UCSF ChimeraX | Goddard et al., 201864 | https://www.cgl.ucsf.edu/chimerax/ |

| PyMOL ver2.5 | Schrüdinger | https://pymol.org/2/ |

| ImageJ | Schneider et al., 201265 | https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/download.html |

| GraphPad Prism | https://www.graphpad.com/features | |

| ilastik | Berg et al., 201966 | https://www.ilastik.org/ |

| cellpose | Stringer et al., 202067 | https://www.cellpose.org/ |

| CellProfiler | Carpenter et al., 200668 | https://cellprofiler.org/ |