Abstract

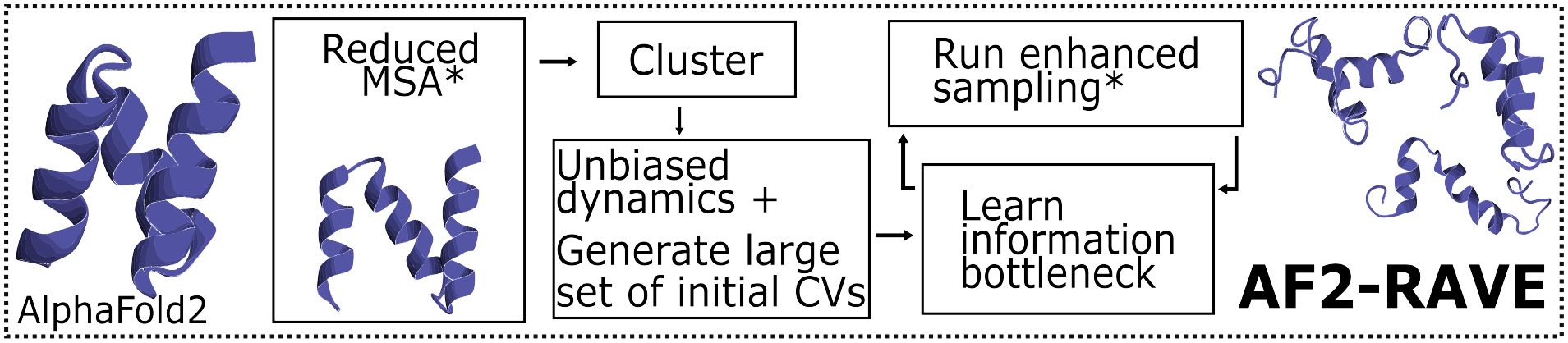

While AlphaFold2 is rapidly being adopted as a new standard in protein structure predictions, it is limited to single structures. This can be insufficient for the inherently dynamic world of biomolecules. In this Letter, we propose AlphaFold2-RAVE, an efficient protocol for obtaining Boltzmann ranked ensembles from sequence. The method uses structural outputs from AlphaFold2 as initializations for AI augmented molecular dynamics. We release the method as an open-source code, and demonstrate results on different proteins.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

While protein structure prediction has traditionally relied on different experimental techniques, 2021 saw a change in the status quo with AlphaFold2.1 It has surpassed the accuracy of other models2,3 and offers a seemingly robust tool for structure prediction directly from amino acid sequences, relying on the idea that conservation of residues across evolutionary protein sequences is correlated with three-dimensional Euclidean distances. Building on this, AlphaFold2 generates multiple sequence alignments (MSA) of evolutionarily related sequences, hence identifying residues that co-evolve to facilitate structure prediction.

While AlphaFold2 indeed represents phenomenal leaps forward for structural biology, it has some key limitations4–6 with no clear solution so far. The first is that in its original incarnation, AlphaFold2 is a single structure prediction method. Biology is often not about a single structure, but about the ensemble of inter-converting structures.7 This problem was first addressed by simply reducing the size of the input MSA in AlphaFold2, and effectively increasing the conformational diversity explored.5,8 However, this does not provide any notion of relative probabilities of these conformations, even as it introduces several thermodynamically unstable or improbable structures. A second limitation is that AlphaFold2 fails in predicting changes in protein structure due to missense mutations.4 Being able to assign Boltzmann weights would instantly rule out unphysical models generated by MSA length reduction, simulataneously ranking them by thermodynamic propensity, thereby addressing both limitations.

In this communication, we solve these limitations using Artificial Intelligence (AI) augmented all-atom resolution Molecular Dynamics (MD) methods.9 In principle, long unbiased MD simulations, with no AI or AlphaFold2 assistance, should directly characterize the conformational diversity and thermodynamics of all proteins. However, MD simulations are limited in timescales, making sampling diverse protein conformations with statistical fidelity impossible.10 We propose a protocol wherein starting from a given sequence, we obtain an ensemble of Boltzmann-weighted structures, i.e. structures with their relative thermodynamic stabilities. We combine AlphaFold2 in post-processing with the AI-augmented MD method “Reweighted Autoencoded Variational Bayes for Enhanced Sampling (RAVE)”,9 calling the final protocol AlphaFold2-RAVE. RAVE is one of many enhanced MD methods that surmount the timescale limitation; in SI Methods we provide an overview, the advantages it provides over other enhanced MD methods, and other technical details. We emphasize that detailed comparisons between RAVE and other possible enhanced sampling approaches is beyond the scope of this Letter, as our intention is to demonstrate one working protocol together with open-source code.

We present illustrative results using AlphaFold2-RAVE on proteins with unique challenges: the 1HZB CSP11 for side-chain orientation predictions, ubiquitin binding protein UBA2 for disorder effects of missense mutations,4,12–14 and SSTR2 GPCR for conformational diversity predictions.15 For each, we show that AlphaFold2 fails, even with the reduced MSA trick from Ref. 5. AlphaFold2-RAVE does a perfect job in reproducing benchmarks for CSP known from experiments and specialized simulations, while providing results that correlate with both experimental results and biological roles for UBA2 and GPCR.

Our central idea is to first use reduced-MSA AlphaFold2 to generate many possible conformations as the initialization for RAVE, which uses an autoencoder-inspired framework to learn relevant slow degrees of freedom, also called reaction coordinates (RC), by iterating between rounds of MD and autoencoder based analysis, wherein every MD iteration is biased to enhance fluctuations along the new RC. The RC itself is expressed as a “State Predictive Information Bottleneck (SPIB)”,16 i.e. the least information needed about a protein’s current attributes to predict its future state after a specified time. This allows one to account for the inherently dynamic personalities of proteins,17 as well as obtain a Boltzmann-weighted ensemble of conformations.

Results

Rotameric metastability in cold shock Protein.

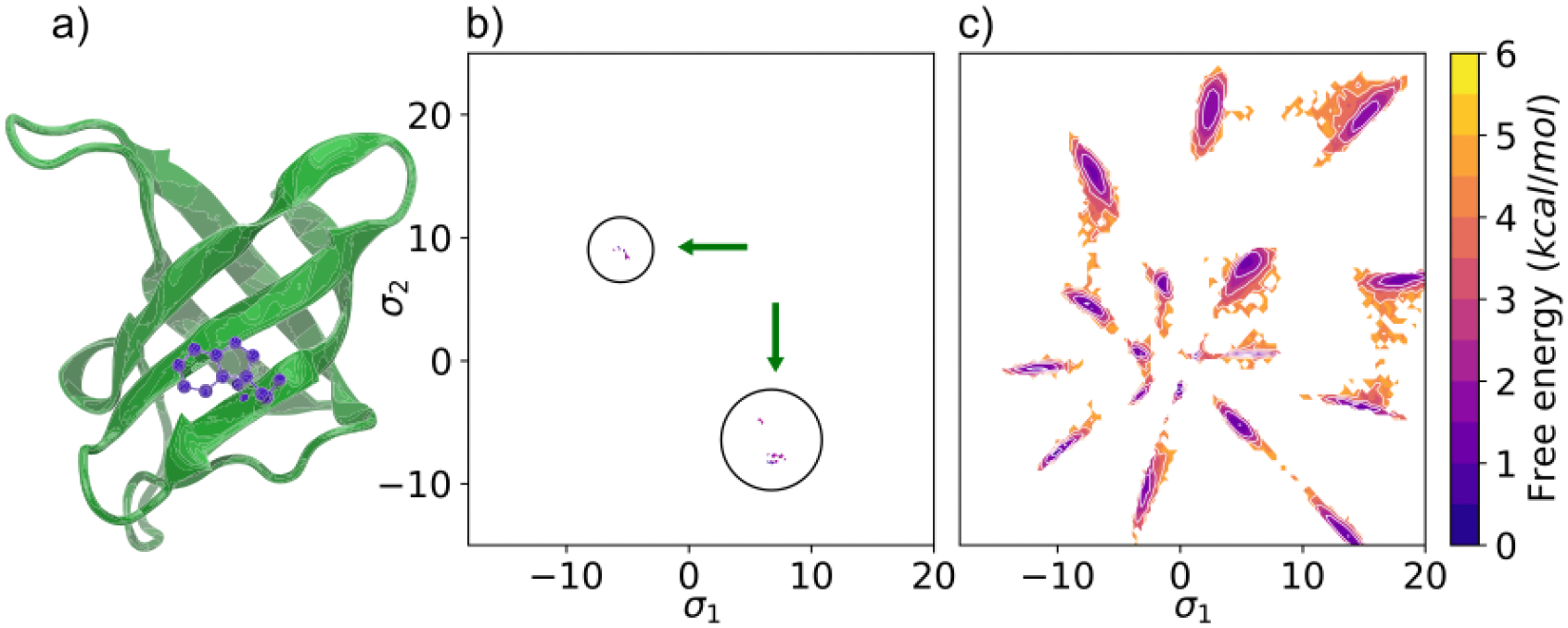

Fig. 2 shows results for the 66-residue CSP (PDB:1HZB). CSP has known rotameric metastability in its eighth residue Trp8 (Fig. 2a), exhibiting 6 states in its χ1 and χ2 torsions through fluorescence spectroscopy.11 To demonstrate the power of AlphaFold2-RAVE, we assume no prior knowledge of any such special residues. Fig. 2b) and c) show probability distributions of conformations obtained from AlphaFold2 with reduced MSA length and with AlphaFold2-RAVE respectively, projected in the space of SPIB coordinates. The enhancement in quality of sampling is unequivocally evident. Further analysis is provided in SI section II establishing that the enhanced sampling here conforms to the Boltzmann distribution(Fig. S1,S2), and that our protocol is also more general than focused sampling (Fig. S3).

Figure 2:

a) Results using AlphaFold2-RAVE on the 1HZB cold-shock protein (CSP). a) Structure of the CSP with tryptophan in purple shown in its most stable rotameric form. Potentials of Mean Force (PMFs) projected along the two-dimensional SPIB σ1 and σ2 learnt from our scheme: b) using structures obtained from reduced MSA AlphaFold2, with some additional diversity compared with traditional AlphaFold2, however without thermodynamic reliability, c) from AlphaFold2-RAVE, showing both conformational diversity and thermodynamics.

Disorder in mutant form of Ubiquitin associated protein.

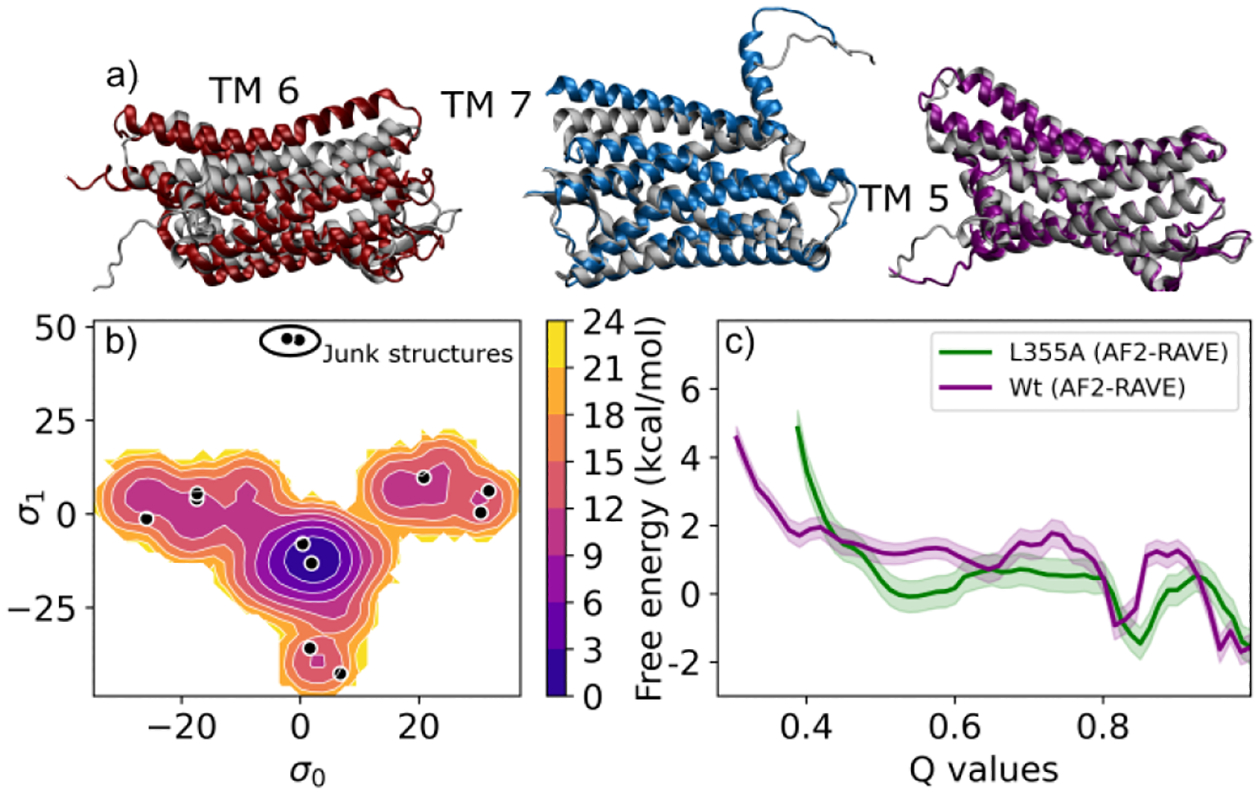

Fig. 3c shows PMFs from AlphaFold2-RAVE for both WT and L355A UBA2. AlphaFold2 was recently shown to be unable to capture the changes in native state stability of a partially helical disordered structure caused by the missense mutation L355A.4 For the WT we find that the unfolded-folded state energy difference is −0.3 kcal/mol, while for the mutant the same difference is 1.2 kcal/mol. Calculation and further analysis can be found in SI section IV. This shows that the mutation does indeed increase its disordered nature. In Fig. 1 we show representative structures obtained from all three stages of our protocol, demonstrating our significantly enhanced sampling of quasi-helical disordered structures.

Figure 3:

a) SSTR2 structures highlighting helix movement in TM6, TM7, TM5 via AlphaFold2-RAVE enhanced sampling, agreeing with experiments18 and biological function. Low energy structures are in colour, overlaid on native structure (grey). b) SSTR2 PMF using AlphaFold2-RAVE, showing multiple potential states. Black dots show structures obtained from reduced-MSA AF2, with structures marked as “junk” representing CV regions that cannot be sampled through transitions. c) UBA2 PMFs along total Q-value for WT(purple), L355A(green). The wild type shows a visibly higher barrier and L355A has a wider, stabler disordered region.

Figure 1:

AlphaFold2-RAVE schematic with representative UBA2 L355A structures from AlphaFold2, reduced MSA AlphaFold2, and partially disordered structure predicted by AlphaFold2-RAVE.

Helical motion in G-protein coupled receptor.

The final system we study is the medically relevant19 G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR), for which AlphaFold2 is unable to capture conformational diversity.14 Specifically, we explore conformational shifts in the somatostatin receptor SSTR2. Once again, we find that AlphaFold2-RAVE detects several local changes in sidechain positions, and also larger scale helical motions. This corresponds well with known evidence of GPCR structural diversity.18 In Fig. 3a, we show examples of the large scale helical shifts we are able to observe. Fig. 3b shows the PMF projected on the SPIB. Details on collective variables and further discussions can be found in SI section I-E and III respectively.

Conclusion

To conclude, we propose the AlphaFold2-RAVE method, combining strengths of AlphaFold2 with all-atom resolution enhanced sampling powers of RAVE.9 This combination provides an effective reaction coordinate, the SPIB, for a particular protein sequence that discovers and differentiates biologically relevant conformational ensembles. A converged enhanced sampling method like metadynamics along the SPIB ranks these conformations with their correct Boltzmann weights. Even prior to convergence, significant information can be gained regarding the relative importance of metastable structures, which can be useful to distill inputs for structure based drug design methods.20,21 It is true that to some extent, we are relying on the ability of our modified version of AlphaFold2 to capture some structural diversity. It is possible that for some rare proteins with no evolutionary homologues with structural diversity, we may not see this. However, we do note that we are able to sample regions (in both CSP and UBA2) that were not represented in the AlphaFold2 output, but that the learned information bottleneck can still lead to.

While any sampling protocol could in principle be implemented here, we prefer RAVE (specifically the SPIB variant) due to minimal hand-tuning and prior knowledge required regarding metastable states and latent spaces to drive sampling. RAVE itself can be augmented with any rare event sampling method, and there exist several such methods with their own specific advantages and disadvantages. Here we choose to demonstrate the protocol using metadynamics for its relatively straightforward implementation, but alternately our protocol can incorporate one of many methods that use collective variables, such as umbrella sampling,22 weighted ensemble,23 NEUS,24 string method,25 etc. Similarly, instead of AlphaFold2 we could use other experimental26 or computational2,3 approaches to generate initial dictionaries of possible conformations; we choose AlphaFold2 for its simplicity, accuracy and relative ease. However, we present a methodology combining three approaches in a novel protocol to learn more than the sum of its parts: structure prediction from sequence, learning collective variables using machine learning, and molecular dynamics. Here, we apply AlphaFold2-RAVE to three systems of biological relevance, demonstrating its usefulness in obtaining Boltzmann ranked conformational diversity.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Research in this publication was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R35GM142719. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. We thank Deepthought2, MARCC, and XSEDE27 (projects CHE180007P and CHE180027P) for computational resources. We thank Dr. Eric Beyerle, Zachary Smith, and Luke Evans for critical reading of the manuscript, and Dr. Ed Miller and Dr. Dilek Coskun for helpful discussions regarding GPCRs.

Footnotes

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): P.T. is a consultant to Schrodinger, Inc. and is on their Scientific Advisory Board.

Supporting Information Available

Detailed description of methods used and further analysis of systems and sampling can be found in the supplement.

Code Availability

The code to run the full pipeline in a seamless manner is available at https://github.com/tiwarylab/alphafold2rave. This can be run on Google Colab using GPUs. Using Colab Pro is advised. We also have a toolkit that can be made available on request to be used to prepare files for use on high performance computers. This will be made available on the same Github soon. Note that the online tutorial uses OpenMM28 whereas our results are using GROMACS. This is because only OpenMM can be easily run on colab for demonstrative purposes.

Data Availability

All data associated with this work is available through https://github.com/tiwarylab/alphafold2rave.

References

- (1).Jumper J et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 2021, 596, 583–589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Miao Y; McCammon JA Annual reports in computational chemistry; Elsevier, 2017; Vol. 13; pp 231–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Baek M et al. Accurate prediction of protein structures and interactions using a threetrack neural network. Science 2021, 373, 871–876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Buel GR; Walters KJ Can AlphaFold2 predict the impact of missense mutations on structure? Nature Structural & Molecular Biology 2022, 29, 1–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).del Alamo D; Sala D; Mchaourab HS; Meiler J Sampling alternative conformational states of transporters and receptors with AlphaFold2. eLife 2022, 11, e75751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Kabir A; Inan T; Shehu A Analysis of AlphaFold2 for Modeling Structures of Wildtype and Variant Protein Sequences. Proceedings of 14th International Conference. 2022; pp 53–65. [Google Scholar]

- (7).Henzler-Wildman K; Kern D Dynamic personalities of proteins. Nature 2007, 450, 964–972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Schlessinger A; Bonomi M Artificial Intelligence: Exploring the conformational diversity of proteins. eLife 2022, 11, e78549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Wang Y; Ribeiro JML; Tiwary P Past–future information bottleneck for sampling molecular reaction coordinate simultaneously with thermodynamics and kinetics. Nature Communications 2019, 10, 3573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Frauenfelder H; Sligar SG; Wolynes PG The Energy Landscapes and Motions of Proteins. Science 1991, 254, 1598–1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Moors SLC; Hellings M; De Maeyer M; Engelborghs Y; Ceulemans A Tryptophan rotamers as evidenced by X-ray, fluorescence lifetimes, and molecular dynamics modeling. Biophysical journal 2006, 91, 816–823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Becht DC; Leavens MJ; Zeng B; Rothfuss MT; Briknarová K; Bowler BE Residual Structure in the Denatured State of the Fast-Folding UBA(1) Domain from the Human DNA Excision Repair Protein HHR23A. Biochemistry 2022, 61, 767–784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Bertolaet BL; Clarke DJ; Wolff M; Watson MH; Henze M; Divita G; Reed SI UBA domains of DNA damage-inducible proteins interact with ubiquitin. Nature Structural Biology 2001, 8, 417–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).He X.-h.; You C.-z.; Jiang H.-l.; Jiang Y; Xu HE; Cheng X AlphaFold2 versus experimental structures: evaluation on G protein-coupled receptors. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica 2022, 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).del Alamo D; Sala D; Mchaourab HS; Meiler J Sampling alternative conformational states of transporters and receptors with AlphaFold2. eLife 2022, 11, e75751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Wang D; Tiwary P State predictive information bottleneck. The Journal of Chemical Physics 2021, 154, 134111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Henzler-Wildman K; Kern D Dynamic personalities of proteins. Nature 2007, 450, 964–972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Dalton JA; Lans I; Giraldo J Quantifying conformational changes in GPCRs: glimpse of a common functional mechanism. BMC bioinformatics 2015, 16, 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Insel PA; Sriram K; Wiley SZ; Wilderman A; Katakia T; McCann T; Yokouchi H; Zhang L; Corriden R; Liu D, et al. GPCRomics: GPCR expression in cancer cells and tumors identifies new, potential biomarkers and therapeutic targets. Frontiers in pharmacology 2018, 9, 431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Jiménez J; Doerr S; Martínez-Rosell G; Rose AS; De Fabritiis G DeepSite: protein-binding site predictor using 3D-convolutional neural networks. Bioinformatics 2017, 33, 3036–3042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Krivák R; Hoksza D P2Rank: machine learning based tool for rapid and accurate prediction of ligand binding sites from protein structure. Journal of Cheminformatics 2018, 10, 39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Torrie G; Valleau J Nonphysical sampling distributions in Monte Carlo free-energy estimation: Umbrella sampling. Journal of Computational Physics 1977, 23, 187–199. [Google Scholar]

- (23).Huber GA; Kim S Weighted-ensemble Brownian dynamics simulations for protein association reactions. Biophys J 1996, 70, 97–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Vani BP; Weare J; Dinner AR Computing transition path theory quantities with trajectory stratification. The Journal of Chemical Physics 2022, 157, 034106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Roux B String Method with Swarms-of-Trajectories, Mean Drifts, Lag Time, and Committor. The Journal of Physical Chemistry A 2021, 125, 7558–7571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Yip KM; Fischer N; Paknia E; Chari A; Stark H Atomic-resolution protein structure determination by cryo-EM. Nature 2020, 587, 157–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Towns J; Cockerill T; Dahan M; Foster I; Gaither K; Grimshaw A; Hazlewood V; Lathrop S; Lifka D; Peterson GD; Roskies R; Scott JR; Wilkins-Diehr N XSEDE: Accelerating Scientific Discovery. Computing in Science Engineering 2014, 16, 62–74. [Google Scholar]

- (28).Eastman P; Swails J; Chodera JD; McGibbon RT; Zhao Y; Beauchamp KA; Wang L-P; Simmonett AC; Harrigan MP; Stern CD; Wiewiora RP; Brooks BR; Pande VS OpenMM 7: Rapid development of high performance algorithms for molecular dynamics. PLOS Computational Biology 2017, 13, e1005659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data associated with this work is available through https://github.com/tiwarylab/alphafold2rave.