Abstract

Objective

While the role of Hedgehog (Hh) signaling in promoting zonal fibrocartilage production during development is well-established, whether this pathway can be leveraged to improve tendon-to-bone repair in adults is unknown. Our objective was to genetically and pharmacologically stimulate the Hh pathway in cells that give rise to zonal fibrocartilaginous attachments to promote tendon-to-bone integration.

Design

Hh signaling was stimulated genetically via constitutive Smo (SmoM2 construct) activation of bone marrow stromal cells or pharmacologically via systemic agonist delivery to mice following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction (ACLR). To assess tunnel integration, we measured mineralized fibrocartilage (MFC) formation in these mice 28 days post-surgery and performed tunnel pullout testing.

Results

Hh pathway-related genes increased in cells forming the zonal attachments in WT mice. Both genetic and pharmacologic stimulation of the Hh pathway increased MFC formation and integration strength 28 days post-surgery. We next conducted studies to define the role of Hh in specific stages of the tunnel integration process. We found Hh agonist treatment increased proliferation of the progenitor pool in the first week post-surgery. Additionally, genetic stimulation led to continued MFC production in later stages of the integration process. These results indicate that Hh signaling plays an important biphasic role in cell proliferation and differentiation towards fibrochondrocytes following ACLR.

Conclusion

This study reveals a biphasic role for Hh signaling during the tendon-to-bone integration process after ACLR. In addition, the Hh pathway is a promising therapeutic target to improve tendon-to-bone repair outcomes.

Keywords: hedgehog signaling, ACL reconstruction, tendon-to-bone repair, mineralized fibrocartilage, transgenic mice

INTRODUCTION

During tendon growth and development, there is a coordinated series of events that lead to zonal enthesis formation1. These events begin with the specification of the enthesis progenitor pool1–5 followed by expansion of these progenitors and synthesis of the collagenous matrix. A subset of these cells then differentiates into fibrochondrocytes that deposit proteoglycan-rich matrix to create the unmineralized fibrocartilage zone. Finally, a portion of unmineralized fibrochondrocytes closest to the bone interface mineralize the surrounding matrix to create the mineralized fibrocartilage (MFC) zone1. Similarly, adult anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction produces zonal tendon-to-bone attachments between the tendon graft and adjacent newly formed bone through a staged repair response6–11. Using a murine ACL reconstruction (ACLR) model, we previously demonstrated that an alpha smooth muscle actin (αSMA)-expressing amplifying progenitor pool of bone marrow stromal cells (bMSCs) adjacent to the tendon graft, not the tenocytes within the graft, initiate zonal attachment formation by infiltrating the graft and anchoring collagen fibers to the adjacent bone12,13. The cells in these nascent attachment sites then synthesize proteoglycan-rich fibrocartilage and ultimately mineralize this fibrocartilage to form four distinct zones within the tendon-to-bone attachment. While the tunnel integration process involves these specific and coordinated stages, the cell signaling events that regulate this response are not clear.

One such cell signaling pathway that is critical to enthesis development and may play a similar role in tendon-to-bone repair is the hedgehog (Hh) pathway. During embryonic development, the downstream Hh transcription factor Gli1 is one of the distinct markers that delineates enthesis progenitors from adjacent tendon midsubstance or nascent cartilage cells. These Gli1-expressing progenitors give rise to the unmineralized and mineralized fibrochondrocytes of the fully formed zonal enthesis4. Hh signaling is a potent positive regulator of fibrocartilage differentiation and maturation1,4,5,14–16. For instance, Hh overactivation in Scx-expressing tendon cells leads to ectopic fibrocartilage formation in the tendon midsubstance5 while ablating Hh signaling leads to striking deficits in enthesis MFC formation1,4,14. Furthermore, Hh ligands play a biphasic role in enthesis development1,4,5,14,16. Sonic hedgehog (Shh) regulates the specification of enthesis progenitors in utero16 and Indian hedgehog (Ihh) promotes enthesis maturation during postnatal growth1,5. Ultimately, Hh signaling plays critical roles in promoting zonal enthesis fibrocartilage specification, differentiation, and maturation.

Since the Hh pathway is a potent regulator of enthesis fibrocartilage formation during growth and development, we hypothesize that it plays a similar role in fibrocartilage production during tendon-to-bone repair. The pathway is active following tendon-to-bone repair of the rotator cuff in rats17 and ACLR in rats and mice18–20. However, it is not clear what role the pathway has in regulating the healing response after surgery. Therefore, the objective of the current study is to stimulate the Hh pathway genetically and pharmacologically to promote tendon-to-bone integration following ACLR. The extent of zonal tunnel integration is assessed using multiplexed mineralized cryohistology and tunnel pullout tests. An improved understanding of the signaling pathways regulating tendon-to-bone attachment formation during repair is a crucial step towards developing new therapies to improve repair outcomes.

METHODS

Mice

All animal procedures were approved by the University of Pennsylvania’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. The mouse lines used in this study were described previously: αSMACreERT221, R26R-tdTomato Cre reporter (B6;129S6-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm9(CAG-tdTomato)Hze/J, stock # 007905)22, and R26SmoM2 (STOCK Gt(ROSA)26Sortm1(Smo/EYFP)Amc/J, stock # 005130)23. αSMACreERT2 and R26R-tdTomato mice were bred in a mixed genetic background containing C57BL/6, CD1, and 129/SvJ strains. R26SmoM2 mice were maintained on a C57BL/6 background. αSMACreERT2 mice were crossed with R26SmoM2 mice or R26R-tdTomato mice to yield double transgenic mice.

Experimental design

ACL reconstructions were performed on 71 mice (mean ± SD age, 16.5 ± 2.3 weeks old). To measure expression of Hh- and enthesis-related genes, αSMACreERT2;R26R-tdTomato mice were sacrificed at 3, 7, and 14 days post-surgery for qPCR analysis from microdissected histological sections (n = 3–4/timepoint). To increase Hh activity genetically in cells that give rise to the tendon-to-bone attachments, αSMACreERT2;R26SmoM2 (SmoCA) mice received intraperitoneal tamoxifen injections (80 mg/kg) (Sigma-Aldrich Corp.) on the day of surgery and every other day thereafter for a total of five injections to activate Smo in αSMA-expressing cells. These mice were compared to Cre-negative littermate controls. Mice were randomly assigned to cryohistology (n = 10–13/group) or biomechanics (n = 5–7/group) and sacrificed at 28 days post-surgery. Demeclocycline (Sigma-Aldrich Corp.) injections (60 mg/kg) were given the day prior to sacrifice to label deposited mineral for mice assigned to cryohistology. A subset of mice also received calcein (6 mg/kg) (Sigma-Aldrich Corp.) seven days prior to sacrifice to label deposited mineral at that time. To increase Hh activity pharmacologically, αSMACreERT2;R26R-tdTomato mice received the Hh agonist Hh-Ag1.5 (Cellagen Technology, 20 mg/kg)24 five times per week (control mice received PBS). These mice were sacrificed at 28 days post-surgery and assigned to cryohistology (n = 6–7/group) or biomechanics (n = 7/group). Additional agonist-treated and PBS control mice were assigned to proliferation and microdissected qPCR analysis at day 7 post-surgery. These mice received tamoxifen injections on the day of surgery, 3-, and 5-days post-surgery along with 5-Ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU, Click Chemistry Tools, 3 mg/kg) every day (n = 4–5/group). Cryosections were either collected for qPCR analysis or stained for EdU. Both male and female sexes were included and equally distributed across treatment groups. KF was aware of the treatment group assignments and TBK conducted the analyses while blinded to these treatment groups.

ACL reconstruction procedure

ACL reconstructions were performed similarly to previously described work12,13. Briefly, 27G needles were used to drill the femoral and tibial tunnels and tail tendon autografts were used to reconstruct the ACL. Washers (316 stainless-steel) were used as external fixators on the femoral and tibial cortices. Detailed surgical procedures are described in the Supplementary Materials.

qPCR of microdissected sections

Mice were euthanized at days 3, 7, and 14 post-surgery for gene expression analysis of different stages of the repair process. Hindlimbs were processed as previously described25. Tape-stabilized 20μm thick tissue sections were collected and kept frozen until tissue capture. Specific regions from each timepoint were collected by cutting the tissue and underlying tape with a 27G needle (Fig. S1). Regions of the expanding marrow (defined as the fibrotic marrow adjacent to the tunnel interface), early attachments, and mineralized attachments were collected from the day 3, 7, and 14 samples, respectively. Native ACL entheses were collected from contralateral limbs. Tissues were digested, RNA was isolated, cDNA was synthesized, and the cDNA was pre-amplified as previously described25. qPCR was performed on the pre-amplified cDNA samples using the Taqman Fast Advanced Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific) with Taqman probes listed in Supplemental Table 1. Principal component analysis (PCA) and hierarchical clustering was performed on ΔCT values using ClustVis26.

For gene expression analysis of the subset of mice that received Hh agonist or vehicle injections for 7 days, mice were euthanized at 7 days post-surgery. Regions of expanding marrow around both sides of the femoral tunnel were captured and used for qPCR analysis with Taqman probes for 18S, Gli1, and Ptch1.

Multiplexed mineralized cryohistology

Following euthanasia, hindlimbs were harvested, fixed in formalin for 3 days, transferred to 30% sucrose overnight, and embedded in OCT. Tape-stabilized 8μm thick frozen mineralized sagittal sections27 of the knee were collected and each section was subjected to multiple rounds of imaging on the Zeiss Axio Scan.Z1 digital slide scanner. For samples assigned to histology at 28 days after surgery, imaging rounds included 1) fluorescent reporters, mineralization labels, and polarized light, 2) alkaline phosphatase (AP) fluorescent staining (ELF97 Phosphatase Substrate, Thermo Fisher Scientific) with TO-PRO-3 counterstain (Invitrogen), and 3) 0.025% toluidine blue (TB). Sections from mice assigned to histology 7 days after surgery underwent the following rounds: 1) fluorescent reporters, polarized light, and Calcein Blue staining (Sigma-Aldrich Corp.)27, 2) EdU detection with Alexa Fluor 647 azide (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and Click-&-Go Cell Reaction Buffer Kit (Click Chemistry Tools), and 3) Hematoxylin and aqueous eosin staining (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Layered composite images of all imaging rounds were assembled and aligned in image editing software.

Tunnel pullout test

Tunnel pullout tests were performed similarly to previous work12. Dissected femurs were potted in polymethyl methacrylate and mounted to a custom fixture. Scar tissue around the washer was carefully dissected. If the tendon was accidentally cut, the sample was excluded. Fishing line was passed through the femoral washer, gripped, and loaded uniaxially at 0.025 mm/sec until failure on an Instron Model 5542a. Failure location was noted from video recordings of the test.

Image analysis

MFC area, percentage of tunnel length containing MFC, percentage of MFC produced in the last week, and EdU+ cells in the expanding marrow were quantified using Fiji (ImageJ)28. Detailed methodology for each measurement can be found in Supplementary Materials.

Statistics

Sample size estimation was performed a priori using G*Power 3.1.9.6 software and additional analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 9.2.0 (GraphPad Software). Based on previous experiments by our group12, a sample size of 7 per group provides 80% power with an alpha level of 0.05 to detect a difference of 0.5 (standard deviation of 0.3) between control and Hh-stimulated mice. Normally distributed data were confirmed using Shapiro-Wilk normality tests. Treated and control groups for their respective datasets were compared using Student’s t-tests (p < 0.05). Data are presented as mean ± SD.

RESULTS

Hh-related gene activity increases during tendon-to-bone integration

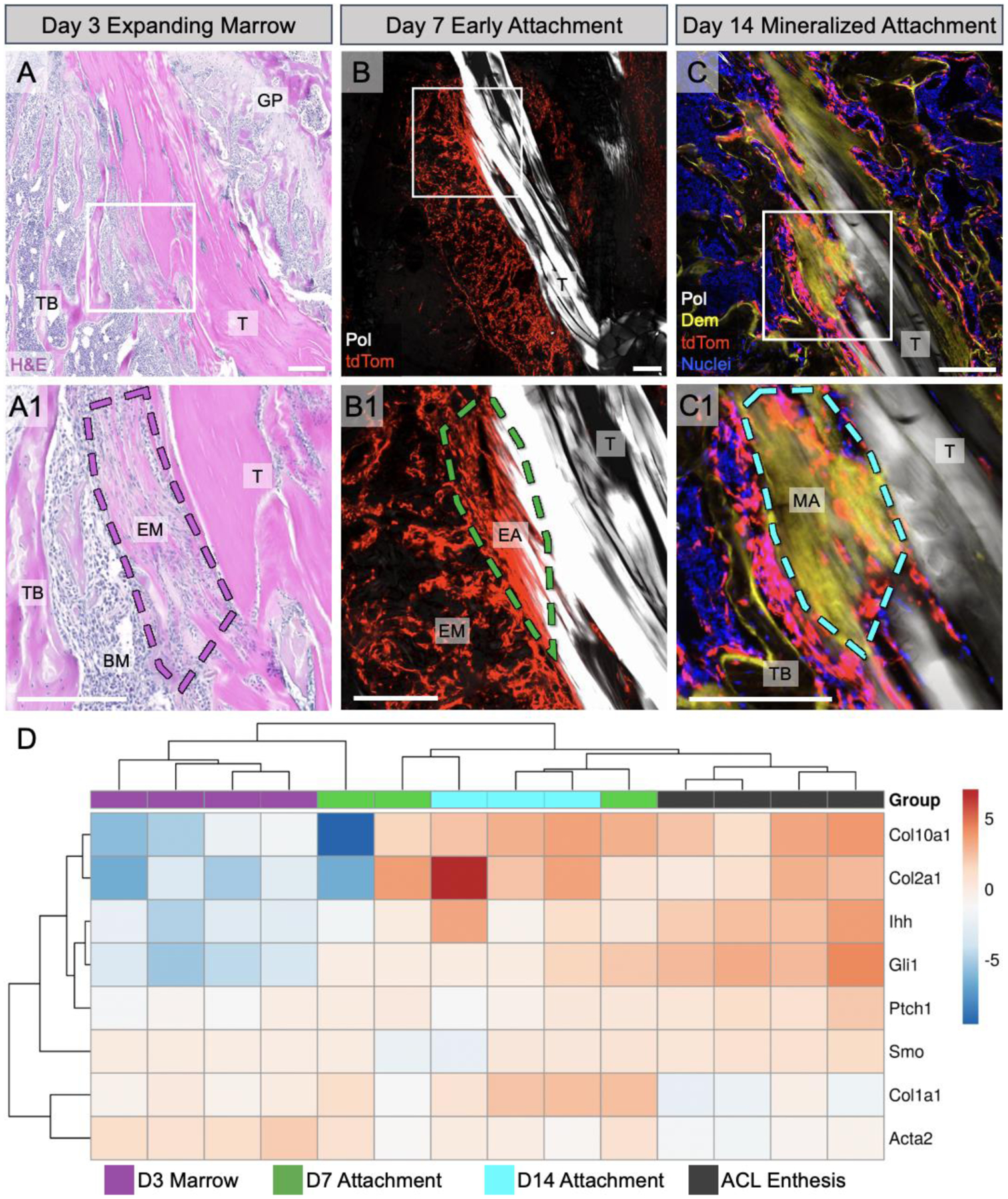

Following ACL reconstruction, tendon-to-bone integration occurs through a series of coordinated events6–13,18. We first wanted to investigate the spatiotemporal expression pattern of Hh-related genes during these stages. Therefore, we captured specific tissue regions from fixed sections at days 3, 7, and 14 post-surgery (Fig. S1). In the day 3 sections, we captured the expanding marrow, which is characterized by areas of denser extracellular matrix (eosin in Fig. 1A, A1) containing αSMA-expressing cells12 adjacent to the tendon graft. In day 7 sections, we captured tissue from regions where αSMA+ cells began to infiltrate the tendon graft and initiate the attachment (Fig. 1B, B1). Finally, we captured tissue from regions of the mineralized attachment sites in day 14 sections, which could be visualized with αSMACreERT2;R26R-tdTomato expression in areas of strong demeclocycline labeling (Fig. 1C, (C1). These attachment sites were more mature compared to the nascent sites seen at day 7, which did not contain mineralized fibrocartilage. Contralateral ACL entheses were captured from both day 3 and day 7 samples as controls.

Figure 1. Hh-related gene activity increased during tendon-to-bone integration after ACLR.

At day 3 post-surgery, bone marrow cells amplified and expanded around the tendon graft, resulting in expanding marrow (EM) with denser ECM indicated by stronger eosin staining (A, A1). At 7 days post-surgery, the amplified cells as visualized with the αSMACreERT2;R26R-tdTomato model began to infiltrate the tendon graft and form early attachment sites (B, B1). By day 14 post-surgery, there were mineralized attachments present containing mineralized fibrocartilage (MFC) where collagen fibers (Pol light, white) span an area of strong demeclocycline (Dem) signal (C, C1). We captured these specific regions at each timepoint for qPCR, where panels A-C are for demonstration purposes with A1, B1, and C1 showing the specific tissue regions of interest at those timepoints. Contralateral ACL enthesis tissue was also collected. A qPCR (ΔCT) heatmap (D) was generated after analyzing captured tissues for fibrochondrocyte (Col10a1, Col2a1), Hh-related (Ihh, Gli1, Ptch1, Smo), and ECM (Col1a1, Acta2) genes (n = 3–4/group). T = tunnel, GP = growth plate, TB = trabecular bone, BM = bone marrow, MA = mineralized attachment. Scale bars = 200μm.

We then queried gene expression changes of Hh-related and other marker genes throughout the integration process using qPCR. We performed principal component analysis with hierarchical clustering on ΔCT values obtained from qPCR for all samples and target genes. Hierarchical clustering revealed that samples from each timepoint generally clustered together. As expected, cells from regions of expanding marrow (day 3) expressed higher levels of Acta2 as the cells activated and expanded in response to the surgery (Fig. 1D), corresponding with previous IHC data12. Additionally, Col1a1 levels increased throughout the repair process as cells infiltrated the graft and deposited collagen matrix to anchor the newly formed attachments to bone, while cells in the native contralateral ACL enthesis had lower Col1a1 expression. As expected, the ACL entheses and day 14 mineralized attachments had higher expression of the fibrocartilage markers Col2a1 and Col10a1, compared to the expanding marrow and early attachments. Finally, the Hh-responsive gene Gli1 and the ligand Ihh were highly expressed in ACL entheses and mineralized attachment sites, correlating with mature enthesis fibrocartilage markers, whereas Ptch1 and Smo were relatively consistent during the repair process. Overall, these expression data indicate that Hh activity increases in cells as they form mature tendon-to-bone attachments.

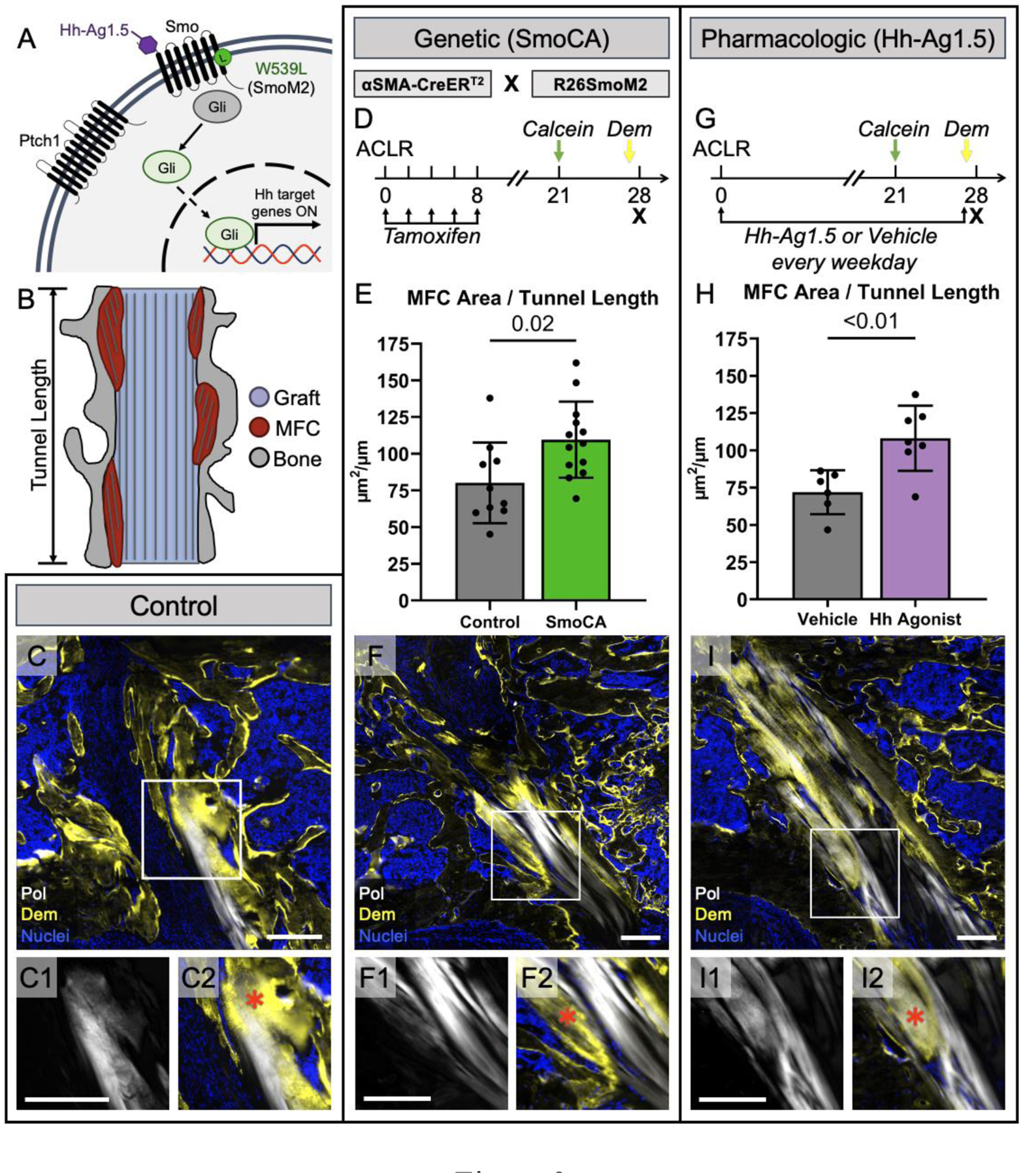

Hh signaling promotes zonal tunnel integration following ACL reconstruction

To investigate the role of Hh signaling in regulating the repair response after surgery, we utilized genetic and pharmacologic approaches to stimulate the pathway in cells participating in the repair response. In our genetic approach, we crossed αSMACreERT2 mice, which we previously showed target the amplifying bMSCs that contribute to zonal attachment formation12, with mice containing the R26SmoM2 construct harboring a W539L point mutation in the central signal transducer of the Hh pathway Smoothened (Smo) (Fig. 2A). Upon tamoxifen administration, these mice experienced expression of the constitutively active form of Smo (SmoCA) in αSMA-expressing cells and their progeny. To assess the extent of zonal tunnel integration after ACL reconstruction, we used mineral labeling (demeclocycline) and collagen structure (polarized light) in histological sections to identify regions of mineralized fibrocartilage (MFC), which we then quantified and normalized to bone tunnel length (Fig. 2B). With increased Hh signaling in αSMA-lineage cells (Fig. 2D), the SmoCA mice had 36% greater MFC area than controls at 28 days post-surgery (p = 0.02, Fig. 2E, F). This result indicates that Hh signaling in these cells promotes the production of zonal tendon-to-bone attachments in the tunnels.

Figure 2. Hh signaling promoted zonal attachment formation following ACL reconstruction.

Without Hh ligand binding, the Hh pathway (A) is inhibited by Ptch1 suppressing the activity of Smo and maintaining Gli proteins in their repressed form. Upon ligand binding to Ptch1, the Smo inhibition is removed and Smo can convert Gli proteins into their active state, leading to downstream Hh-target gene expression. Mineralized frozen sections were made at day 28 post-surgery and we quantified MFC area (B) by outlining areas where collagen fibers (white in C, C1, C2) displayed Dem mineral label (yellow in C, C2) and normalized the area by the tunnel length. We genetically modulated the Hh pathway by incorporating a mutant form of Smo, SmoM2, that leads to Ptch1 and ligand-independent activation of the pathway and crossed these mice with αSMACreERT2 mice (SmoCA) that target the cells participating in attachment formation (D). We gave tamoxifen injections in the first week post-surgery and mineral labels 7 and 1 day before sacrifice to label deposited mineral. SmoCA mice had increased MFC area 28 days post-surgery (E) (p = 0.02, n = 10–13/group). Representative sagittal section from SmoCA mice is shown in (F), with insets showing collagen structure (F1) and MFC (F2). We also gave systemic injections of the Smo agonist, Hh-Ag1.5, (A) every weekday for 28 days post-surgery (G), which increased MFC area (H) (p < 0.01, n = 6–7/group). A representative section from an agonist-treated mouse is shown in (I). Scale bars = 200μm. Red * in C2, F2, and I2 represent MFC.

Since genetic Smo overexpression had a positive effect on MFC formation, we next determined whether a therapy using the small molecule Hh agonist (Hh Ag1.5), which binds to Smo regardless of Smo inhibition by Patched1 (Ptch1) (Fig. 2A), would have a similar effect on tunnel integration. To confirm that the agonist increased Hh activity in cells participating in repair, we gave daily injections and measured expression of Gli1 and Ptch1 in regions adjacent to the bone tunnels on day 7. This dosing regimen yielded 16.2- and 11.7-fold increases in Gli1 and Ptch1, respectively (Fig. S2). After demonstrating effectiveness using this dose, we then gave injections every weekday for 28 days post-surgery (Fig. 2G) and compared the MFC formation to vehicle controls. Hh agonist-treated mice had 50% greater MFC area after 28 days compared to mice that received vehicle injections (p < 0.01, Fig. 2H, I), indicating that Hh agonist delivery promotes tendon-to-bone integration.

Up-regulating Hh signaling improves tendon-to-bone integration strength

To directly test whether the increased MFC in Hh-stimulated mice resulted in higher integration strength, we performed tunnel pullout tests on SmoCA and Hh agonist-treated mice as previously described12. Femurs were used for pullout tests because the tendon knot around the tibial washer was not strong enough to consistently withstand the forces experienced during the pullout test. While the mean pullout strength in SmoCA mice was 58% higher than controls, it was not significantly different (p = 0.25, Fig. 3A, left). Hh agonist-treated mice yielded 48% greater pullout strength compared to vehicle controls (p = 0.03, Fig. 3A, right). Interestingly, the failure location in the SmoCA mice, and their Cre-negative littermates, was shifted towards the graft region outside the tunnel compared to the intra-tunnel failures for mice in the agonist experiment (Fig. 3B, C). This shift in failure location may have negatively impacted the results of the SmoCA study. Nonetheless, these results indicate that the increased MFC formation in the Hh-stimulated mice can result in improved tunnel integration strength.

Figure 3. Hh signaling improved tendon-to-bone integration strength following ACL reconstruction.

Femurs were dissected of soft tissue and mounted in PMMA. Fishing line was hooked through the femoral washer on one end and a grip on a linear actuator on the other end. The washer was pulled linearly until failure and the maximum failure force was recorded. SmoCA mice (A, left) and Hh agonist-treated mice (A, right) had greater pullout strengths compared to their respective controls (p = 0.25, n = 5–7/group for SmoCA, p = 0.03, n = 7/group for Hh agonist). Failure locations for each sample were recorded and were categorized into i) inside tunnel, ii) outside tunnel, and iii) washer failures. Failure locations for each sample are denoted in A with shapes and the percentage distributions for failure locations are plotted in B for SmoCA (B, left) and Hh agonist-treated mice (B, right). Schematics to help visualize failure locations are shown in C.

Hh signaling promotes proliferation of the amplifying progenitor pool

Since our results indicated that Hh stimulation increased tendon-to-bone integration, both genetically and pharmacologically, we next sought to determine the mechanism by which Hh signaling improved this process. Given that the Hh pathway was previously shown to promote bMSC proliferation29, in addition to several other cell types30–32, we determined the effect of agonist treatment on proliferation of the expanding bMSC progenitor pool. By increasing expansion of this pool, there would be more cells capable of forming attachments, which could contribute to the increased MFC formation at day 28 (Fig. 2). Therefore, we delivered daily injections of Hh-Ag1.5 or vehicle in addition to daily injections of EdU for one week post-surgery and assessed the percentage of EdU positive cells within the expanding marrow adjacent to the tunnels at 7 days post-surgery (Fig. 4A). Since these regions contained newly formed woven bone that harbored EdU+ cells (Fig. 4A1), we excluded the woven bone from our analysis (Fig. 4A2). We found that agonist treatment yielded a 52% increase in cell proliferation (p = 0.03, Fig. 4B) and a 18% increase in cell density in the expanding marrow (p < 0.01, Fig. 4C), suggesting that hedgehog stimulation results in a larger pool of cells capable of forming tendon-to-bone attachments.

Figure 4. Hh stimulation in the first week post-surgery increased proliferation of the amplifying progenitor pool.

αSMACreERT2;R26R-tdTomato mice that received Hh-Ag1.5 and EdU for 6 days post-surgery were assessed at 7 days post-surgery to determine the effect of Hh agonist treatment in the first week of surgery on proliferation of the amplifying bMSC progenitor pool. The area around the tunnel where tdTomato cells were present in the expanding marrow was used for analysis (dashed white outline in A). Because newly formed woven bone was present in this region at 7 days post-surgery (gray in A1), the EdU cell count contributions from the bone areas were removed from the final EdU+ cell counts (A2). Hh agonist treatment increased the proliferation of cells in the expanding marrow (B) (p = 0.03, n = 4–5/group) which resulted in an increased cell density in this region (C) (p < 0.01). GP = growth plate. Scale bar in A = 200μm.

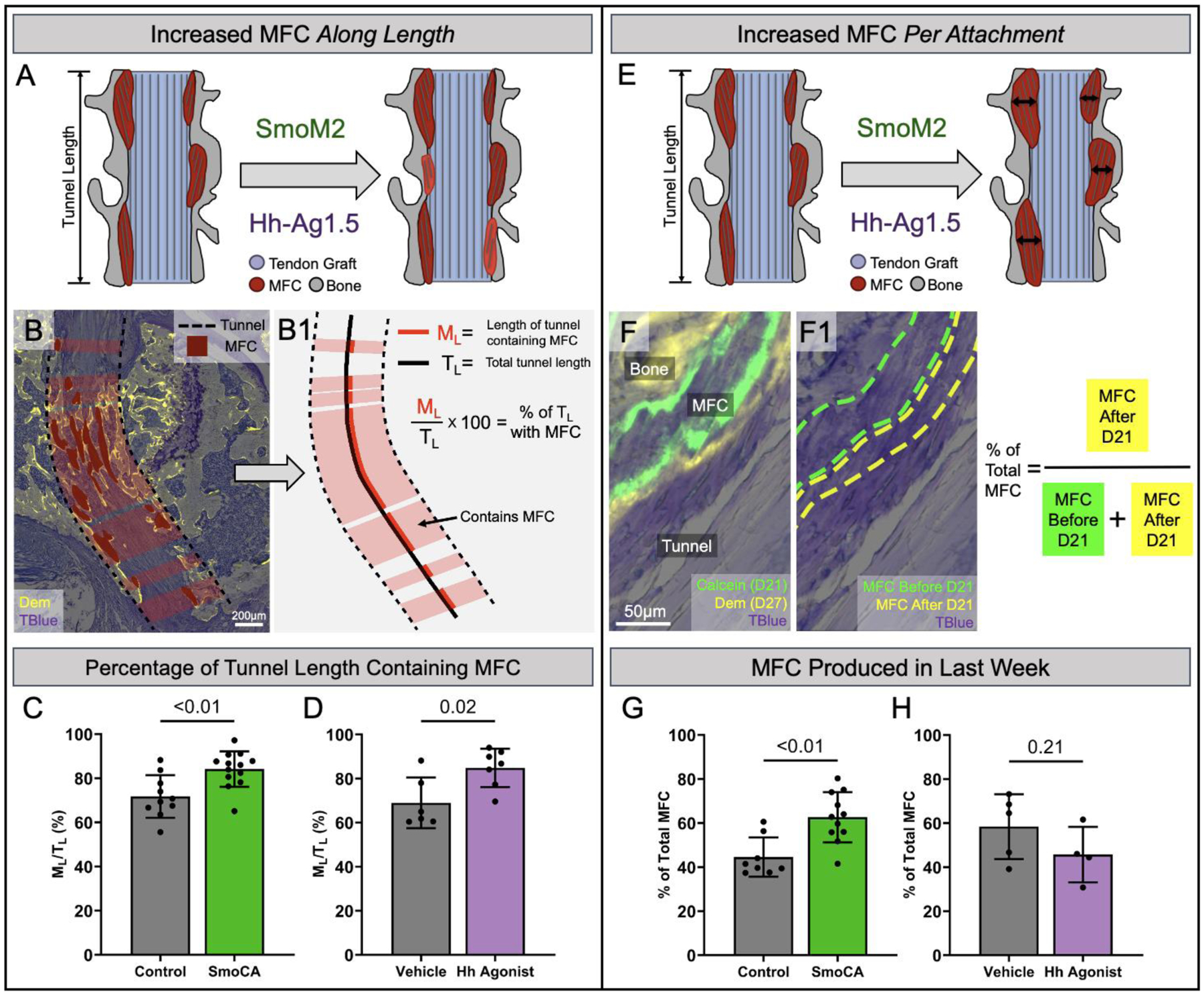

Hh stimulation results in more attachments along the tunnel length and increased mineral apposition within each attachment

Since Hh agonist treatment increased proliferation of the bMSC progenitor pool that gives rise to zonal attachments, there are conceivably more cells available to infiltrate the graft, differentiate into mineralizing fibrochondrocytes, and create zonal attachment sites. This would ultimately lead to more attachment sites along the tunnel length (Fig. 5A). To test this mechanism, we took the sections used for MFC area analysis and projected the MFC areas horizontally to the edges of the tunnel (Fig. 5B) to obtain the length of the tunnel containing MFC (ML), which was then normalized by the total length of the tunnel (TL) to calculate the percentage of the tunnel length containing MFC (Fig. 5B1). We found that SmoCA mice had 17% greater percentage of tunnel length containing MFC compared to controls (p < 0.01, Fig. 5C). Additionally, Hh agonist-treated mice had 23% greater percentage of tunnel length containing MFC compared to vehicle controls (p = 0.02, Fig. 5D). These results indicate that Hh stimulation increased the number of attachment sites formed, which may be attributed to the increased proliferation of the bMSC progenitor pool.

Figure 5. Mineralized fibrocartilaginous attachments increased after Hh stimulation as a result of more attachments along the tunnel length and increased mineral apposition within each attachment.

Mice that were used for MFC area analysis from SmoCA and Hh agonist-treated mice were analyzed to determine the mechanism for increased MFC area: more attachments along the tunnel length (A) or more MFC produced in the last week as a result of more fibrocartilaginous differentiation (E). The MFC area regions used for MFC area/tunnel length quantification (dark red regions in B) were extended horizontally to the edges of the tunnel (dashed black lines in B) to obtain the length of the tunnel containing MFC (ML) which was then normalized by the total length of the tunnel (TL) to get the percentage of the tunnel length containing MFC (B1). The percentage of the tunnel length containing MFC was increased in the SmoCA mice (C) (p < 0.01, n = 10–13/group) and after Hh agonist treatment (D) (p = 0.02, n = 6–7/group) 28 days post-surgery. To determine if the mechanism for greater MFC area was due to more MFC production in the last week post-surgery, SmoCA and Hh agonist-treated mice received a calcein label at day 21 and a demeclocycline label at day 27 to label mineral deposited in the last week, and the MFC area between the two labels was measured (F, F1). SmoCA mice had greater percentage of MFC produced in the last week compared to controls (G) (p < 0.01, n = 8–11/group), while Hh agonist-treatment did not produce a difference in MFC produced in the last week (H) (p = 0.21, n = 4–5/group). Although the same samples were used for quantifying both the percentage of the tunnel length containing MFC and MFC produced in the last week, the lower sample size for the latter measurement was due to missing calcein mineral labels.

Another mechanism that could explain the increased MFC area is an increase in mineral apposition by fibrochondrocytes in each attachment (Fig. 5E), which would indicate that Hh signaling promoted fibrocartilage maturation similar to its role in enthesis growth and development1,4,14. To test this mechanism, we measured MFC produced during the last week by subtracting MFC area up to day 21 (defined by the calcein label given on day 21) from the total MFC area (defined by the demeclocycline label, see Fig. 2) in SmoCA and Hh agonist-treated mice (Fig. 5F, (F1). SmoCA mice had 40% greater percentage of MFC produced in the last week compared to controls (p < 0.01, Fig. 5G) while Hh agonist treatment did not significantly affect the percentage of MFC produced in the last week (p = 0.21, Fig. 5H, breakdown of MFC produced before and after day 21 can be found in Fig. S3). In addition to the proliferation results in Fig. 4, these findings suggest that Hh signaling has a biphasic role in tendon-to-bone attachment formation in this model.

DISCUSSION

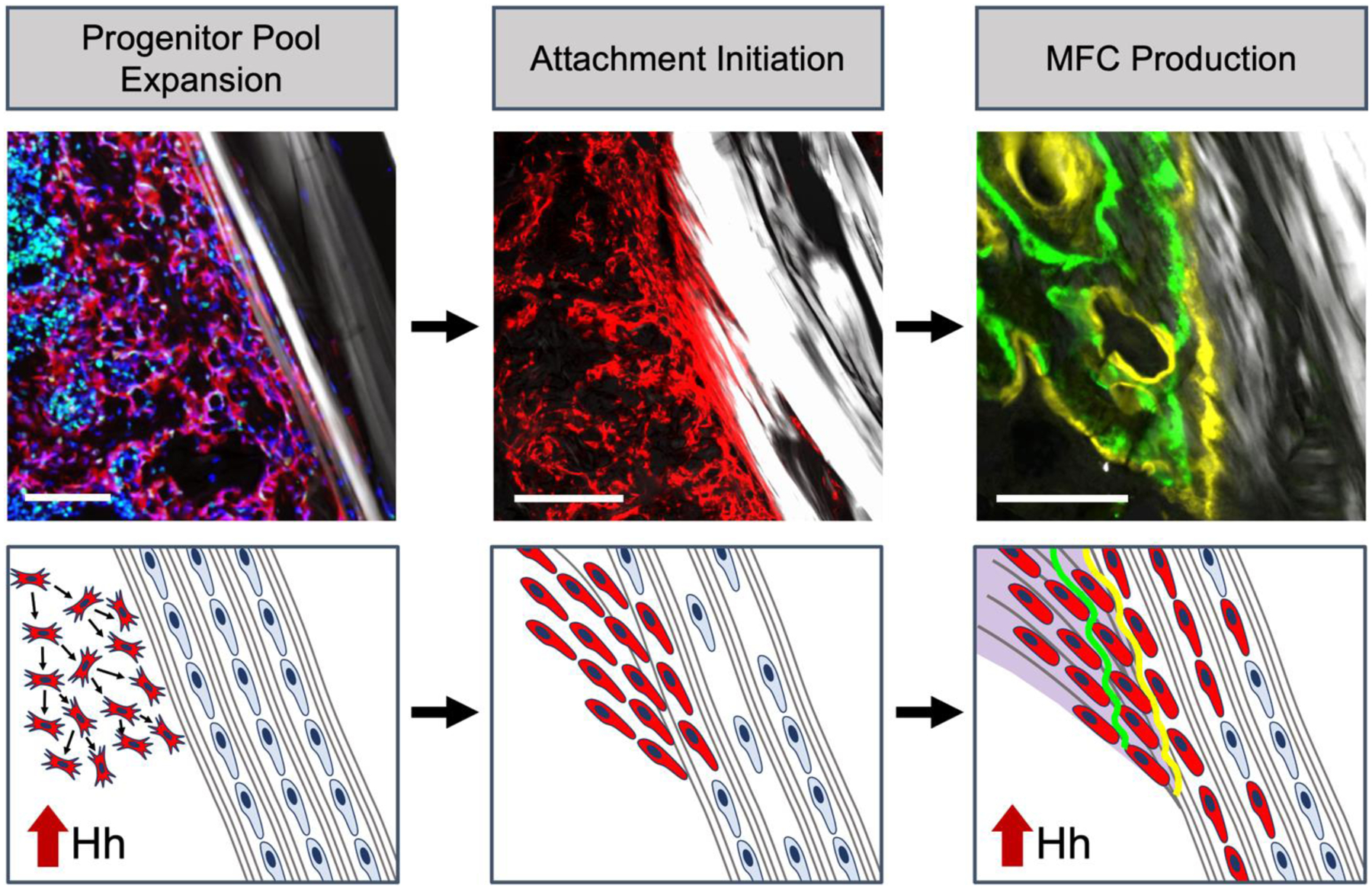

Tendon-to-bone integration following ACL reconstruction occurs through a coordinated series of events, beginning with amplification of the bMSC progenitor pool, followed by infiltration of these cells into the graft, and finally production of zonal fibrocartilaginous tendon-to-bone attachments. This study demonstrates that Hh signaling plays a biphasic role in this coordinated process by positively regulating the proliferation of the expanding progenitor pool and promoting MFC production in the zonal tendon-to-bone attachments in the bone tunnels (Fig. 6). While it has previously been reported that the Hh pathway is active during tendon-to-bone repair17–19 and may have a positive role in enthesis healing33,34, we demonstrated via genetic and pharmacologic approaches that it promotes both bMSC proliferation and MFC formation during the tunnel integration process. As the cells differentiate into Col2a1 and Col10a1-expressing mineralized fibrochondrocytes, the levels of Gli1, Ptch1, and Ihh expression increase, indicating that Hh activity becomes more prominent during the later stages of zonal attachment formation (Fig. 1D). We also used inducible αSMACreERT2 mice to activate Hh signaling in cells after they initiate the repair response. This genetic approach yielded increased zonal tendon-to-bone attachment formation (Fig. 2D–F), indicating that activating Hh signaling within the αSMA-expressing progenitor pool improves their ability to form MFC within the attachments. We then used the small molecule agonist, Hh Ag-1.5, to stimulate the pathway pharmacologically, which produced similar improvements in tendon-to-bone integration (Fig. 2G–I). Taken together, these results indicate that the Hh pathway is a potent regulator of the tendon-to-bone integration process.

Figure 6. Hh signaling has a biphasic role in the tendon-to-bone integration following ACL reconstruction.

The tunnel integration process begins with bMSC progenitor pool expansion in response to the drilling of the bone tunnels. We found that hedgehog signaling plays a role in promoting expansion of this progenitor pool, leading to a greater population of cells capable of initiating the graft and creating attachments. These cells then infiltrate the tendon graft to initiate the attachments, which coincides with cell death of native tenocytes within the graft. Finally, the infiltrating cells synthesize proteoglycan-rich extracellular matrix (purple) and mineralize this region in an appositional manner, leading to the creation of distinct zones of bone, mineralized fibrocartilage, unmineralized fibrocartilage, and tendon midsubstance.

Given that Hh signaling has a positive role in cell proliferation29–32, fibrocartilage differentiation1,4,5,14–16,35, and osteogenesis36–46, we investigated the influence of Hh signaling on these specific stages of the tendon-to-bone integration process. These stages are not independent, however. For instance, a greater expansion of the bMSC progenitor pool would equate to a greater number of cells capable of producing zonal attachments, even if fibrocartilage differentiation is not affected. Indeed, we found that Hh agonist delivery promoted cell proliferation within the expanding marrow (Fig. 4), which is the source of cells that form the zonal attachments. Additionally, a larger proportion of the tunnel length contained MFC following Hh stimulation (Fig. 5A–D), suggesting that this proliferation effect led to an increase in the number of tendon-to-bone attachment sites along the tunnel length. Furthermore, if Hh signaling promoted fibrocartilage differentiation, we would expect there to be continued mineral apposition within each attachment site. Indeed, we found higher production of MFC at later stages of tunnel integration in the SmoCA mice compared to controls (Fig. 5G). Taken together, these data indicate that Hh signaling has a positive role in both cell proliferation and mineralized fibrocartilage production in the formation of zonal tendon-to-bone attachments, leading to improved tunnel integration strength (Fig. 3).

While genetic and pharmacologic Hh stimulation both increased MFC area (Fig. 2) and the percentage of the tunnel length containing MFC (Fig. 5A–D), only the SmoCA mice yielded an increase in the MFC produced in the last week (as a percentage of total MFC) compared to their respective control mice (Fig. 5G). When breaking down the MFC production to before and after day 21 (Fig. S3), SmoCA and agonist treatments had different MFC dynamics. SmoCA mice produced more MFC than controls at later stages of the integration process, whereas Hh agonist treatment led to more MFC production in the earlier stages (Fig. S3D). Why daily systemic injections of the Hh agonist did not continue to stimulate MFC production could be due to several reasons. First, while αSMA-expressing cells in the bMSC progenitor pool and their progeny had constitutive and unrestricted activity of SmoM2 in the SmoCA mice, the agonist treated mice relied on continued delivery of the agonist to the tunnel space. The bone tunnels changed drastically during the tunnel integration process as the attachments mature with more accumulated MFC and bone. As this maturation occurs, diffusion of the agonist to these attachment sites would likely be reduced. Additionally, Hh Ag-1.5 becomes less effective on cells at high concentrations,47 suggesting that cells may become desensitized to the agonist delivery at later stages. On the other hand, the agonist had a greater effect on MFC production during early stages (Fig. S3), perhaps because the agonist is targeting a larger number of cells than the SmoCA model. Additionally, there is likely a lag in Hh activation in the SmoCA mice, compared to agonist treated mice, due to the pharmacokinetics of tamoxifen metabolism, Cre recombination, and smoothened protein production. Future studies will investigate different agonist treatment windows to further establish whether Hh plays a more prominent role in the early stages of proliferation and lineage commitment to fibrochondrocytes or later stages of mineralized fibrocartilage production.

Because Hh signaling promotes osteogenesis36–46, which may influence the tendon-to-bone integration in this model, we also measured new bone formation at multiple timepoints. Interestingly, we found that Hh stimulation had no appreciable effect on bone formation (Figs. S4–5). We previously found that αSMA-expressing cells in the expanding marrow gave rise to fewer osteocytes than mineralized fibrochondrocytes12, which may explain why the SmoCA mice did not affect bone formation (Fig. S5). Furthermore, we also did not see an effect on bone formation with agonist delivery (Figs. S4–5). This is in contrast with the osteogenic role of Hh in fracture healing24,36–39. However, fracture healing is driven by periosteal progenitor cells undergoing endochondral ossification, whereas bMSCs give rise to new bone following ACLR via intramembranous ossification. Ultimately, our data indicate that Hh signaling plays a more prominent role in the formation of fibrocartilaginous attachment sites than new bone in this ACLR model.

This study is not without limitations. For instance, while the murine model offers tremendous genetic tools to tackle mechanistic questions, the small animal size presents some technical limitations. We utilized tail tendons for the ACL graft as they allow for improved fixation12,13 with external fixators due to their increased length compared to other tendons in the mouse. Therefore, the tunnel integration process is more analogous to a hamstring tendon graft used clinically, as opposed to bone-patellar tendon-bone. Additionally, the tunnel pullout test is impacted by soft tissue scar formation around the femoral washer, requiring careful dissection to remove the scar without damaging the adjacent tendon graft. We recorded videos of each test to help exclude samples in which too much scar tissue remained. Unlike the agonist study, many of the samples in the SmoCA study failed outside the bone tunnel adjacent to the washer, which limited our ability to test the tendon-to-bone interface in the tunnel (Fig. 3B, C). The reason for this difference in failure location is unknown.

Future therapeutic work targeting this pathway is also needed. For instance, the prolonged dose of daily agonist injections over several weeks is likely not a viable treatment regimen, as Hh signaling is essential in the maintenance of multiple tissues48,49. In our study, a small number of mice receiving Hh-Ag1.5 developed hair loss and skin hypertrophy at the injection sites around the third week of injection. A subset of SmoCA mice displayed heterotopic ossification lesions in the fat pad in the knee and around the patellar tendon (Fig. S6), likely due to Smo overexpression in αSMA-expressing cells in the healing tissue in these regions. These lesions did not have a noticeable effect on limb ambulation, however. Additionally, we did not include loss-of-function (e.g., conditional knockout or small molecule inhibitor delivery) groups in this study. Instead, we focused on stimulating the pathway to improve tunnel integration. Nonetheless, we would expect that lower hedgehog activity would lead to reduced cell proliferation and MFC formation. In the future, we plan to deliver Hh agonists or inhibitors at different stages of the repair process to identify an optimal therapeutic window for targeting the pathway to improve repair. Ultimately, localized agonist delivery within a specific therapeutic window will be essential for harnessing the therapeutic potential of the Hh pathway in enhancing tendon-to-bone repair.

An improved understanding of the signaling pathways that regulate zonal insertion formation in the adult are crucial to developing new therapies to improve repair outcomes. By genetically and pharmacologically stimulating the Hh pathway in our ACL reconstruction model, we demonstrated that the Hh pathway plays a prominent, biphasic role in zonal attachment formation in the bone tunnels. Future work from our group will focus on localized delivery of Hh agonists to translate this therapy to larger animal models that more closely replicate the tissue size and joint forces of the human knee. This study suggests that novel therapeutics effectively targeting the Hh pathway would likely improve repair outcomes, expediting recovery times and reducing healthcare expenditures for these debilitating injuries.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by NIH R01-AR076381, R21-AR078429, R00-AR067283, F31-AR079840 (support for TBK), and P30-AR069619 (pilot grant award and core facilities) in addition to the McCabe Fund Pilot Award at the University of Pennsylvania.

ROLE OF THE FUNDING SOURCE

All funding sources had no influence on the design, collection, or analysis of data in this study. Funding sources are National Institutes of Health R01-AR076381, R21-AR078429, R00-AR067283, F31-AR079840 (support for TBK), and P30-AR069619 (pilot grant award and core facilities) in addition to the McCabe Fund Pilot Award at the University of Pennsylvania.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

DECLARATION OF COMPETING INTEREST

The authors have no competing interests to disclose that would influence the work reported in this paper.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dyment NA, Breidenbach AP, Schwartz AG, Russell RP, Aschbacher-Smith L, Liu H, et al. Gdf5 progenitors give rise to fibrocartilage cells that mineralize via hedgehog signaling to form the zonal enthesis. Dev Biol. 2015;405:96–107. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2015.06.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blitz E, Sharir A, Akiyama H, Zelzer E. Tendon-bone attachment unit is formed modularly by a distinct pool of Scx-and Sox9-positive progenitors. Development (Cambridge). 2013;140:2680–2690. doi: 10.1242/dev.093906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sugimoto Y, Takimoto A, Akiyama H, Kist R, Scherer G, Nakamura T, et al. Scx+/Scx9+ progenitors contribute to the establishment of the junction between cartilage and tendon/ligament. Development (Cambridge). 2012;140:2280–2288. doi: 10.1242/dev.096354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schwartz AG, Long F, Thomopoulos S. Enthesis fibrocartilage cells originate from a population of hedgehog-responsive cells modulated by the loading environment. Development (Cambridge). 2015;142:196–206. doi: 10.1242/dev.112714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu CF, Breidenbach A, Aschbacher-Smith L, Butler D, Wylie C. A Role for Hedgehog Signaling in the Differentiation of the Insertion Site of the Patellar Tendon in the Mouse. Xie J, ed. PLoS One. 2013;8:e65411. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deehan DJ, Cawston TE. The biology of intergration of the anterior cruciate ligament. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery - Series B. 2005;87:889–895. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.87B7.16038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kobayashi M, Watanabe N, Oshima Y, Kajikawa Y, Kawata M, Kubo T. The fate of host and graft cells in early healing of bone tunnel after tendon graft. American Journal of Sports Medicine. 2005;33:1892–1897. doi: 10.1177/0363546505277140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rodeo SA, Arnoczky SP, Torzilli PA, Hidaka C, Warren RF. Tendon-healing in a bone tunnel. A biomechanical and histological study in the dog. J Bone Joint Surg. 1993;75:1795–1803. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199312000-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bedi A, Kawamura S, Ying L, Rodeo SA. Differences in tendon graft healing between the intra-articular and extra-articular ends of a bone tunnel. HSS Journal. 2009;5:51–57. doi: 10.1007/s11420-008-9096-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hexter AT, Thangarajah T, Blunn G, Haddad FS. Biological augmentation of graft healing in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Bone Joint J. 2018;100-B:271–284. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.100b3.bjj-2017-0733.r2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weiler A, Hoffmann RFG, Bail HJ, Rehm O, Südkamp NP. Tendon healing in a bone tunnel. Part II: Histologic analysis after biodegradable interference fit fixation in a model of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in sheep. Arthroscopy. 2002;18:124–135. doi: 10.1053/jars.2002.30657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kamalitdinov TB, Fujino K, Shetye SS, Jiang X, Ye Y, Rodriguez AB, et al. Amplifying Bone Marrow Progenitors Expressing α-Smooth Muscle Actin Produce Zonal Insertion Sites During Tendon-to-Bone Repair. Journal of Orthopaedic Research. 2020;38:105–116. doi: 10.1002/jor.24395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hagiwara Y, Dyrna F, Kuntz AF, Adams DJ, Dyment NA. Cells from a GDF5 origin produce zonal tendon-to-bone attachments following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2020;1460:57–67. doi: 10.1111/nyas.14250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Breidenbach AP, Aschbacher-Smith L, Lu Y, Dyment NA, Liu CF, Liu H, et al. Ablating hedgehog signaling in tenocytes during development impairs biomechanics and matrix organization of the adult murine patellar tendon enthesis. Journal of Orthopaedic Research. 2015;33:1142–1151. doi: 10.1002/jor.22899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu CF, Aschbacher-Smith L, Barthelery NJ, Dyment N, Butler D, Wylie C. Spatial and Temporal Expression of Molecular Markers and Cell Signals During Normal Development of the Mouse Patellar Tendon. Tissue Eng Part A. 2012;18:598–608. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2011.0338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Felsenthal N, Rubin S, Stern T, Krief S, Pal D, Pryce BA, et al. Development of migrating tendon-bone attachments involves replacement of progenitor populations. Development. 2018;145:dev165381. doi: 10.1242/dev.165381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zong JC, Mosca MJ, Degen RM, Lebaschi A, Carballo C, Carbone A, et al. Involvement of Indian hedgehog signaling in mesenchymal stem cell–augmented rotator cuff tendon repair in an athymic rat model. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2017;26:580–588. doi: 10.1016/J.JSE.2016.09.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carbone A, Carballo C, Ma R, Wang H, Deng X, Dahia C, et al. Indian hedgehog signaling and the role of graft tension in tendon-to-bone healing: Evaluation in a rat ACL reconstruction model. Journal of Orthopaedic Research. 2016;34:641–649. doi: 10.1002/jor.23066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deng XH, Lebaschi A, Camp CL, Carballo CB, Coleman NW, Zong J, et al. Expression of Signaling Molecules Involved in Embryonic Development of the Insertion Site Is Inadequate for Reformation of the Native Enthesis. J Bone Joint Surg. 2018;100:e102. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.16.01066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yu H, Fu F, Yao S, Luo H, Xu T, Jin H, et al. Biomechanical, histologic, and molecular characteristics of graft-tunnel healing in a murine modified ACL reconstruction model. J Orthop Translat. 2020;24:103–111. doi: 10.1016/J.JOT.2020.05.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grcevic D, Pejda S, Matthews BG, Repic D, Wang L, Li H, et al. In vivo fate mapping identifies mesenchymal progenitor cells. Stem Cells. 2012;30:187–196. doi: 10.1002/stem.780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Madisen L, Zwingman TA, Sunkin SM, Oh SW, Zariwala HA, Gu H, et al. A robust and high-throughput Cre reporting and characterization system for the whole mouse brain. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:133–140. doi: 10.1038/nn.2467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jeong J, Mao J, Tenzen T, Kottmann AH, McMahon AP. Hedgehog signaling in the neural crest cells regulates the patterning and growth of facial primordia. Genes Dev. 2004;18:937–951. doi: 10.1101/gad.1190304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McKenzie JA, Maschhoff C, Liu X, Migotsky N, Silva MJ, Gardner MJ. Activation of hedgehog signaling by systemic agonist improves fracture healing in aged mice. Journal of Orthopaedic Research. 2019;37:51–59. doi: 10.1002/jor.24017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tsinman TK, Jiang X, Han L, Koyama E, Mauck RL, Dyment NA. Intrinsic and growth-mediated cell and matrix specialization during murine meniscus tissue assembly. FASEB Journal. 2021;35:e21779. doi: 10.1096/fj.202100499R [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Metsalu T, Vilo J. ClustVis: A web tool for visualizing clustering of multivariate data using Principal Component Analysis and heatmap. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:W566–W570. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dyment NA, Jiang X, Chen L, Hong SH, Adams DJ, Ackert-Bicknell C, et al. High-Throughput, Multi-Image Cryohistology of Mineralized Tissues. Journal of Visualized Experiments. Published online 2016. doi: 10.3791/54468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schindelin J, Arganda-Carreras I, Frise E, Kaynig V, Longair M, Pietzsch T, et al. Fiji: An open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat Methods. 2012;9:676–682. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Warzecha J, Göttig S, Brüning C, Lindhorst E, Arabmothlagh M, Kurth A. Sonic hedgehog protein promotes proliferation and chondrogenic differentiation of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells in vitro. Journal of Orthopaedic Science. 2006;11:491–496. doi: 10.1007/s00776-006-1058-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang Y, Zhang X, Huang H, Xia Y, Yao YF, Mak AFT, et al. Osteocalcin expressing cells from tendon sheaths in mice contribute to tendon repair by activating hedgehog signaling. Elife. 2017;6. doi: 10.7554/eLife.30474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li J, Cui Y, Xu J, Wang Q, Yang X, Li Y, et al. Suppressor of Fused restraint of Hedgehog activity level is critical for osteogenic proliferation and differentiation during calvarial bone development. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2017;292:15814–15825. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M117.777532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martínez C, Smith PC, Rodriguez JP, Palma V. Sonic hedgehog stimulates proliferation of human periodontal ligament stem cells. In: Journal of Dental Research. Vol 90. J Dent Res; 2011:483–488. doi: 10.1177/0022034510391797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schwartz AG, Galatz LM, Thomopoulos S. Enthesis regeneration: A role for Gli1+ progenitor cells. Development (Cambridge). 2017;144:1159–1164. doi: 10.1242/dev.139303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu Y, Liu S, Song Z, Chen D, Album Z, Green S, et al. GLI1 Deficiency Impairs the Tendon–Bone Healing after Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction: In Vivo Study Using Gli1-Transgenic Mice. J Clin Med. 2023;12:999. doi: 10.3390/JCM12030999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Amano K, Densmore M, Nishimura R, Lanske B. Indian hedgehog signaling regulates transcription and expression of collagen type X via Runx2/Smads interactions. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2014;289:24898–24910. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.570507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kazmers NH, McKenzie JA, Shen TS, Long F, Silva MJ. Hedgehog signaling mediates woven bone formation and vascularization during stress fracture healing. Bone. 2015;81:524–532. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2015.09.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baht GS, Silkstone D, Nadesan P, Whetstone H, Alman BA. Activation of hedgehog signaling during fracture repair enhances osteoblastic-dependent matrix formation. Journal of Orthopaedic Research. 2014;32:581–586. doi: 10.1002/jor.22562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu X, McKenzie JA, Maschhoff CW, Gardner MJ, Silva MJ. Exogenous hedgehog antagonist delays but does not prevent fracture healing in young mice. Bone. 2017;103:241–251. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2017.07.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kashiwagi M, Hojo H, Kitaura Y, Maeda Y, Aini H, Takato T, et al. Local administration of a hedgehog agonist accelerates fracture healing in a mouse model. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2016;479:772–778. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.09.134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Edwards PC, Ruggiero S, Fantasia J, Burakoff R, Moorji SM, Paric E, et al. Sonic hedgehog gene-enhanced tissue engineering for bone regeneration. Gene Ther. 2005;12:75–86. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miller MQ, McColl LF, Arul MR, Nip J, Madhu V, Beck G, et al. Assessment of Hedgehog Signaling Pathway Activation for Craniofacial Bone Regeneration in a Critical-Sized Rat Mandibular Defect. In: JAMA Facial Plastic Surgery. Vol 21. American Medical Association; 2019:110–117. doi: 10.1001/jamafacial.2018.1508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Levi B, James AW, Nelson ER, Li S, Peng M, Commons GW, et al. Human adipose-derived stromal cells stimulate autogenous skeletal repair via paracrine hedgehog signaling with calvarial osteoblasts. Stem Cells Dev. 2011;20:243–257. doi: 10.1089/scd.2010.0250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fuchs S, Dohle E, Kirkpatrick CJ. Sonic Hedgehog-Mediated Synergistic Effects Guiding Angiogenesis and Osteogenesis. In: Vitamins and Hormones. Vol 88. Academic Press; 2012:491–506. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-394622-5.00022-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Petrova R, Joyner AL. Roles for Hedgehog signaling in adult organ homeostasis and repair. Development. 2014;141:3445–3457. doi: 10.1242/dev.083691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang Q, Huang C, Zeng F, Xue M, Zhang X. Activation of the hh pathway in periosteum-derived mesenchymal stem cells induces bone formation in vivo: Implication for postnatal bone repair. American Journal of Pathology. 2010;177:3100–3111. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.100060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Oliveira FS, Bellesini LS, Defino HLA, da Silva Herrero CF, Beloti MM, Rosa AL. Hedgehog signaling and osteoblast gene expression are regulated by purmorphamine in human mesenchymal stem cells. J Cell Biochem. 2012;113:204–208. doi: 10.1002/jcb.23345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Frank-Kamenetsky M, Zhang XM, Bottega S, Guicherit O, Wichterle H, Dudek H, et al. Small-molecule modulators of Hedgehog signaling: identification and characterization of Smoothened agonists and antagonists. J Biol. 2002;1:10. Accessed March 4, 2019. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12437772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Curran T Reproducibility of academic preclinical translational research: Lessons from the development of Hedgehog pathway inhibitors to treat cancer. Open Biol. 2018;8. doi: 10.1098/rsob.180098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bakshi A, Chaudhary SC, Rana M, Elmets CA, Athar M. Basal cell carcinoma pathogenesis and therapy involving hedgehog signaling and beyond. Mol Carcinog. 2017;56:2543–2557. doi: 10.1002/mc.22690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.