Abstract

Preterm birth remains the leading cause of neonatal morbidity and mortality worldwide. A substantial number of spontaneous preterm births occur in the context of sterile intra-amniotic inflammation, a condition that has been mechanistically proven to be triggered by alarmins. However, sterile intra-amniotic inflammation still lacks treatment. The NLRP3 inflammasome has been implicated in sterile intra-amniotic inflammation; yet, its underlying mechanisms, as well as the maternal and fetal contributions to this signaling pathway, are unclear. Here, by utilizing a translational and clinically relevant model of alarmin-induced preterm labor and birth in Nlrp3−/− mice, we investigated the role of NLRP3 signaling using imaging and molecular biology approaches. Nlrp3 deficiency abrogated preterm birth and the resulting neonatal mortality induced by the alarmin S100B by impeding the premature activation of the common pathway of labor as well as by dampening intra-amniotic and fetal inflammation. Moreover, Nlrp3 deficiency altered leukocyte infiltration and functionality in the uterus and decidua. Last, embryo transfer revealed that maternal and fetal Nlrp3 signaling contribute to alarmin-induced preterm birth and neonatal mortality, further strengthening the concept that both individuals participate in the complex process of preterm parturition. These findings provide novel insights into a common etiology of preterm labor and birth, sterile intra-amniotic inflammation, and suggest that the adverse perinatal outcomes resulting from prematurity can be prevented by targeting NLRP3 signaling.

Keywords: sterile intra-amniotic inflammation, inflammasome, prematurity, fetus, neonate, preterm birth, parturition

INTRODUCTION

Preterm birth – defined as delivery prior to 37 weeks of gestation – is the leading cause of neonatal morbidity and mortality worldwide [1, 2]. Compared to other developed countries, the United States continues to have a higher rate of preterm birth [2, 3] that accounts for almost 400,000 preterm babies born per year [2]. Approximately two-thirds of all preterm birth cases are preceded by spontaneous preterm labor [4], a syndrome that comprises multiple etiologies [5]. Among these, intra-amniotic inflammation is one of the most studied and, in a fraction of cases, this clinical condition is induced by a variety of microbes (i.e., intra-amniotic infection) [6–9]. However, the majority of the cases of spontaneous preterm labor associated with intra-amniotic inflammation occurs in the absence of detectable microorganisms, a clinical condition that has been termed sterile intra-amniotic inflammation [5, 10–15]. Women with sterile intra-amniotic inflammation have similar rates of preterm birth and adverse neonatal outcomes to those with intra-amniotic infection [5], and this condition has been associated with obstetrical diseases such as an asymptomatic short cervix [12] and preterm prelabor rupture of membranes (PPROM) [13]. While new evidence has emerged to advance the treatment of intra-amniotic infection [16–19], there is a paucity of therapeutic options to ameliorate sterile intra-amniotic inflammation. Hence, there is a compelling need to elucidate the mechanisms behind sterile intra-amniotic inflammation to identify new therapeutic strategies for preventing the consequent adverse pregnancy and neonatal outcomes.

Sterile inflammation is caused by the release of endogenous danger signals, or alarmins, by cells undergoing processes such as stress, necrosis, or senescence [20, 21]. Accordingly, increased concentrations of the alarmins high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1), interleukin (IL)-1α, S100A12, and S100B have been reported in amniotic fluid of women with sterile intra-amniotic inflammation who delivered preterm [22]. Indeed, the administration of these alarmins into the amniotic cavity induces preterm birth in mice, thus providing a causal link between sterile intra-amniotic inflammation and preterm birth [23–28]. The mechanisms behind this phenomenon are thought to involve the nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain, leucine-rich repeat, and pyrin domain-containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome [24, 25, 29–31], a cytoplasmic multi-subunit protein complex that, once assembled, induces the activation of caspase (CASP)-1 [32, 33] and the subsequent cleavage and release of the mature form of IL-1β [34–36]. Importantly, this cytokine is the master regulator of parturition [37–39], which includes fetal membrane activation, uterine contraction, and cervical dilatation as well as the initiation of local immune processes in the decidua [40–42]. Indeed, we recently demonstrated that Nlrp3 deficiency had a protective effect against preterm birth and adverse neonatal outcomes in dams that received an intra-amniotic injection of a microbial product [43] or the alarmin IL-1α [25]. Similarly, a prior study indicated that the blockade of NLRP3 signaling using a specific inhibitor could reduce the incidence of preterm birth and neonatal mortality driven by the alarmin S100B [44]. However, the immune mechanisms underlying NLRP3 signaling in preterm labor and birth associated with alarmins (i.e., sterile intra-amniotic inflammation), as well as the maternal and fetal contributions to this process, have not been elucidated.

In the current study, we investigated the mechanisms of NLRP3 signaling in the context of sterile intra-amniotic inflammation by assessing fetal and maternal responses to S100B injection in wild type and Nlrp3-deficient mice. Alteration of fetal hemodynamic parameters, inflammation of fetal and maternal tissues, and activation of the common pathway of labor were evaluated using high-resolution ultrasound, immunoblotting, and high-throughput RT-qPCR. In addition, immunophenotyping and RNA sequencing were performed to characterize the cellular innate immune responses induced by S100B preceding preterm birth. Finally, embryo transfer experiments were utilized to directly compare the fetal and maternal contributions to NLRP3 signaling. Overall, the data presented herein expand on our prior studies to provide novel mechanistic evidence implicating maternal-fetal NLRP3 signaling in sterile intra-amniotic inflammation leading to adverse perinatal outcomes.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Mice

C57BL/6 (WT or Nlrp3+/+) and B6.129S6-Nlrp3tm1Bhk/J (KO or Nlrp3−/−) mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA) and housed in the animal care facility at the C.S. Mott Center for Human Growth and Development at Wayne State University (Detroit, MI, USA). A circadian cycle (light:dark = 12:12 h) was used for all mice. Eight- to twelve-week-old females were mated with males of proven fertility. Female mice were checked daily between 8:00 – 9:00 a.m. to investigate the appearance of a vaginal plug, which indicated 0.5 days post coitum (dpc). Females with a vaginal plug were then housed separately from the males, their weights were monitored daily, and a weight gain of ≥ 2 grams by 12.5 dpc confirmed pregnancy. All mice were randomly assigned to sterile intra-amniotic inflammation or control groups prior to the experiments described herein. Numbers of biological replicates are indicated in each figure caption.

Ethics statement

All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at Wayne State University under Protocol Nos. A-07-03-15, 18-03-0584, and 21-04-3506.

Animal model of S100B-induced intra-amniotic inflammation

Ultrasound-guided intra-amniotic injection of S100B [either (cat# 1820-SB; R&D Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, MN) or (cat# P1035-50; BioVision, Inc., Milpitas, CA)] was used to model sterile intra-amniotic inflammation in mice, as previously described [24]. Briefly, dams were anesthetized on 16.5 days post coitum (dpc) by inhalation of 1.75-2% isoflurane (Fluriso™/Isoflurane, USP; VetOne, Boise, ID, USA) and intra-amniotically injected with S100B at concentrations of 60 ng per 25 μL of sterile 1X phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Fisher Scientific Bioreagents, Fair Lawn, NJ, USA or Life Technologies Limited, Pailey, UK) in each amniotic sac under ultrasound guidance using the Vevo® 2100 Imaging System (VisualSonics Inc., Toronto, Ontario, Canada) with a 30-gauge needle. This dose was chosen based on the pathophysiological concentrations of S100B in the amniotic fluid of women with intra-amniotic inflammation and/or infection who delivered preterm (100–30,000 pg/mL) [45]. Control dams were intra-amniotically injected in each sac with 25 μL of PBS. Following intra-amniotic injection, mice were placed under a heat lamp until they regained full motor function, approximately 10 min after removal from anesthesia.

Video monitoring of pregnancy outcomes

A video camera system (Sony Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) was used to record pregnancy parameters, including the rates of preterm birth and neonatal mortality. Gestational length was calculated as the duration of time from the presence of the vaginal plug (0.5 dpc) to the detection of the first pup in the cage bedding. Preterm birth was defined as delivery occurring before 18.5 dpc. The rate of preterm birth was calculated as the proportion of females delivering preterm out of the total number of mice per group. The rate of neonatal mortality was defined as the proportion of delivered pups found dead among the total number of pups. Neonatal weights were recorded at postnatal week 1, 2, and 3.

Evaluation of maternal-fetal obstetrical parameters by Doppler ultrasonography

Nlrp3+/+ or Nlrp3−/− dams were intra-amniotically injected on 16.5 dpc with 60 ng of S100B / 25 μL of PBS in each amniotic sac, as described above. Sixteen h after injection, maternal-fetal obstetrical parameters were evaluated by Doppler ultrasonography using the Vevo 2100 Imaging System with a 55-MHz linear ultrasound probe (VisualSonics Inc.), as previously described [46–50]. Briefly, after induction of anesthesia, the fetal heart rate and peak systolic velocity (PSV) of the umbilical artery of four fetuses from each dam were evaluated, including the fetus most proximal to the cervix in each uterine horn.

Sampling from dams intra-amniotically injected with S100B

Pregnant Nlrp3+/+ or Nlrp3−/− mice were intra-amniotically injected with 60 ng of S100B/25 μL of PBS in each amniotic sac on 16.5 dpc, as described above. Mice were euthanized on 17.5 dpc (16 h after injection). The amniotic fluid was collected from each amniotic sac and centrifuged at 1,300 x g for 5 min at 4°C. The resulting supernatants and cell pellets were stored at −20°C until analysis. Animal dissection to obtain the cervix, uterus (including predominantly myometrial tissue), placenta, decidua basalis, fetal membranes, fetal lung, fetal intestine, and fetal brain was performed. The placentas and fetuses were imaged during tissue dissection and their weights were recorded. Tissues were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen for immunoblotting, or preserved in RNAlater Stabilization Solution (cat# AM7021; Invitrogen by Thermo Fisher Scientific, Carlsbad, CA, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions, for reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR).

RNA isolation, cDNA synthesis, and RT-qPCR analysis of murine tissues

Total RNA was isolated from the fetal membranes, uterus, cervix, decidua, placenta, fetal lung, fetal intestine, and fetal brain using QIAshredders (cat#79656; Qiagen, Germantown, MD, USA), RNase-Free DNase Sets (cat#79254; Qiagen), and RNeasy Mini Kits (cat#74106; Qiagen), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For fetal tissues, the RNA was isolated from fetuses from a single dam and pooled together for RT-qPCR. The NanoDrop 8000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE, USA) and the Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent Technologies, Wilmington, DE, USA) were used to evaluate RNA concentrations, purity, and integrity. Superscript IV VILO Master Mix (cat# 11756050; Invitrogen by Thermo Fisher Scientific Baltics UAB, Vilnius, Lithuania) was used to synthesize complementary (c)DNA. Gene expression profiling of the tissues was performed on the BioMark System for high-throughput RT-qPCR (Fluidigm, San Francisco, CA, USA) with the TaqMan gene expression assays (Applied Biosystems, Life Technologies Corporation, Pleasanton, CA, USA) listed in Table S1.

Negative delta cycle threshold (−ΔCT) values were determined using multiple reference genes (Gusb, Hsp90ab1, Gapdh, and Actb) averaged within each sample for contractility-associated and inflammatory genes. The −ΔCT values were normalized by calculating the Z-score of each gene with the study groups (Nlrp3+/+ dams injected with S100B and Nlrp3−/− dams injected with S100B). Heatmaps were created representing the mean of the Z-score of −ΔCT using GraphPad Prism (v9.0.2; GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA).

Immunoblotting of amniotic fluid and murine tissues

The collected fetal membrane and uterine tissues were snap-frozen and mechanically homogenized in PBS containing a complete protease inhibitor cocktail (cat#11836170001; Roche Applied Sciences, Mannheim, Germany). The resulting lysates were centrifuged at 15,700 x g for 5 min at 4°C and the supernatants were stored at −80°C until use. Next, the Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (cat#23225; Pierce Biotechnology, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Rockford, IL, USA) was used to determine the total protein concentrations in amniotic fluid and tissue lysate samples prior to immunoblotting.

Cell lysates and culture supernatants from murine bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) were utilized as positive controls for the expression of pro-CASP-1, CASP-1 p-20, and mature IL-1β, as previously described [24, 25, 51]. In short, bone marrow was collected from C57BL/6 mice (12 to 16 weeks old) and the cells were differentiated in IMDM medium (cat#12440-053; Thermo Fisher Scientific) with 10% FBS (cat#16140-071; Invitrogen by Thermo Fisher Scientific) and 10 ng/mL of M-CSF (cat#576402; BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA) at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 7 days. Next, the resulting BMDMs were seeded into 6-well tissue culture plates (Fisher Scientific) at 5 x 105 cells/well and cultured at 37°C with 5% CO2 overnight. The cells were then incubated with 0.5 μg/mL of lipopolysaccharide (LPS; Cat#L4391; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) alone for 4 h, after which 10 μM of Nigericin (cat#N7142; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was added for an additional 1 h of incubation to create positive controls for caspase-1 and mature IL-1β. From the LPS- and Nigericin-treated BMDMs, the supernatants were collected and centrifuged at 1,300 x g for 5 min to remove floating cells and debris. Cell-free supernatants were concentrated 10-fold using the Amicon Ultra Centrifuge filter (cat#UFC800324; Ultracel 3K, EMD Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany) and stored at −20°C until use. Cultured BMDMs were then collected and lysed with RIPA buffer (cat#R0278; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) containing a complete protease inhibitor cocktail. Lysates were centrifuged at 15,700 x g for 5 min at 4°C and the supernatants were collected and stored at −20°C until use.

Amniotic fluid (31 μg total protein per well), fetal membrane and uterine tissue lysates (50 μg per well), and concentrated BMDM cell supernatants (30 or 50 μg per well) were subjected to electrophoresis in 4%–12% sodium dodecyl sulphate-polyacrylamide gels (cat# NP0336BOX; Invitrogen). After separation, the proteins were transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes (cat# 1620145; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA), which were then submerged in blocking solution (cat# 37542; StartingBlock T20 Blocking Buffer, Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 30 min at room temperature (RT). Next, the membranes were probed overnight at 4°C with anti-mouse CASP-1 (cat# 14-9832-82; Thermo Fisher Scientific) or anti-mouse mature IL-1β (cat# 63124S; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA). Lastly, the membranes were washed with 1X Tris-buffered saline containing 0.05% Tween 20 (TBST), blocked with 5% dry milk in 1X TBST, and re-probed for 1 h at RT with a mouse anti-β-actin (ACTB) monoclonal antibody (cat# A5441, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). After incubation with each primary antibody, membranes were incubated with HRP-conjugated anti-rat IgG (cat# 7077S; Cell Signaling) for CASP-1, HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (cat#7074S; Cell Signaling) for mature IL-1β, or HRP-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (cat# 7076S; Cell Signaling) for ACTB for 1 h at RT. The ChemiGlow West Chemiluminescence Substrate Kit (cat# 60-12596-00; ProteinSimple, San Jose, CA, USA) was used to detect chemiluminescent signals, and corresponding images were acquired using the ChemiDoc Imaging System (Bio-Rad). Finally, quantification was performed using ImageJ software [52], which automatically quantified each individual protein band detected on the blot image. The internal control, β-actin, was used to normalize the target protein expression in each fetal membrane and uterine tissue sample for relative quantification. Internal controls were not utilized for amniotic fluid samples; yet, identical protein amounts were loaded for each sample.

Immunoprecipitation of mature IL-1β in murine tissues and amniotic fluid

Immunoprecipitation of cleaved IL-1β from uterine tissue lysates and amniotic fluid was performed using the Pierce™ Classic IP Kit (Cat# 26146; Thermo Fisher Scientific) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Snap-frozen uterine tissues were mechanically homogenized in IP lysis buffer containing a complete protease inhibitor cocktail. Lysates were centrifuged at 13,000 x g for 10 min and the supernatants were collected. Amniotic fluid samples from five dams of each study group were pooled. Culture supernatants from murine BMDMs were prepared as described above and utilized as positive controls. Following the determination of total protein concentration, each uterine tissue lysate (1,000 μg protein) or pooled amniotic fluid sample (1,000 μg protein) was pre-cleared using the control agarose resin and incubated with rabbit anti-mouse mature IL-1β antibody overnight at 4°C to form the immune complex. Next, the immune complex was captured using Pierce Protein A/G Agarose. After several washes to remove non-bound proteins, the immune complex was eluted with sample buffer and subjected to electrophoresis in 4%–12% sodium dodecyl sulphate-polyacrylamide gels followed by western blot transfer, as described above. The blot was then incubated with rabbit anti-mouse mature IL-1β antibody, followed by incubation with an HRP-conjugated anti-heavy chain of rabbit IgG antibody (cat#HRP-66467; Proteintech, Rosemont, IL, USA). Finally, chemiluminescent signals were detected with the ChemiGlow West Substrate Kit and images were acquired using the ChemiDoc Chemiluminescence Imaging System.

Leukocyte isolation from decidual and uterine tissues

Isolation of leukocytes from decidual or uterine tissues was performed as previously described with brief modifications [53] for immunophenotyping or FACS. Dams were intra-amniotically injected with 60 ng of S100B/25 μL of PBS in each amniotic sac on 16.5 dpc, as described above. Mice were euthanized on 17.5 dpc (16 h after intra-amniotic injection) and the decidual and uterine tissues were collected. Tissues were gently minced using fine scissors and enzymatically digested with StemPro Accutase Cell Dissociation reagent (cat #A11105-01; Thermo Fisher) for 25 min at 37°C. Leukocyte suspensions were filtered using a 100-μm cell strainer (cat#22-363-549; Fisher Scientific, Fair Lawn, NY) and washed with PBS immediately prior to immunophenotyping or FACS.

Immunophenotyping of leukocytes from decidual and uterine tissues

Leukocytes isolated from the decidua and uterus were incubated with the CD16/CD32 mAb (FcγIII/II receptor; cat# 553142; BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) for 10 min, followed by incubation with extracellular fluorochrome-conjugated anti-mouse mAbs (Table S2) for 30 min at 4°C in the dark. After washing, the cells were fixed and permeabilized using the BD Cytofix/Cytoperm kit (cat# 554714; BD Biosciences) and subsequently incubated with intracellular fluorochrome-conjugated anti-mouse mAbs (Table S2) for 30 min at 4°C in the dark. Following staining, 10 μL of absolute counting beads (cat# C36950, Thermo Fisher Scientific) were added to each tube, and cells were analyzed using the BD LSRFortessa flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) and FACSDiva 8.0 software (BD Biosciences). The leukocyte numbers were adjusted according to the number of tissues collected per dam. Heatmaps were generated using log2-transformed cell counts.

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting and RNA isolation of viable neutrophils and macrophages from the decidua and uterus

Leukocytes were isolated from the decidua and uterus as mentioned above. After staining with viability dye, the cells were resuspended in 50 μL of stain buffer (cat# 554656; BD Biosciences) and incubated with extracellular fluorochrome-conjugated anti-mouse mAbs (Table S2) for 30 min at 4°C in the dark. The cells were then washed with stain buffer to remove excess mAbs and resuspended in 500 μL of stain buffer for sorting. Viable CD45+CD11b+Ly6G+F4/80- neutrophils and viable CD45+CD11b+F4/80+Ly6G− macrophages were sorted using the BD FACSMelody cell sorter (BD Biosciences) and BD FACSChorus v1.3 software (BD Biosciences). Sorted cells were collected by centrifugation at 3,000 x g for 10 min at RT and resuspended with RNA Extraction Buffer included in the Pico Pure RNA Isolation Kit (Applied Biosystems by Thermo Fisher Scientific). Next, the cell suspensions were incubated at 42°C for 30 min and centrifuged at 3,000 x g for 2 min at RT. The supernatants were stored at −80°C until RNA isolation. Total RNA was isolated using the Pico Pure RNA Isolation Kit, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA concentrations, purity, and integrity were evaluated using the NanoDrop 1000 spectrophotometer and the Bioanalyzer 2100. To obtain sufficient quantities of RNA for RNA-seq, two – four neutrophil samples (biological replicates) from each group were combined. Low-input RNA-seq libraries were constructed by Beijing Genomics Institute (BGI; Wuhan, China) using the Nextera DNA Library Preparation Kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). The libraries were sequenced on the DNB sequencer (DNBSEQ-G400, BGI) with paired-end 100 base reads. Raw data were provided by BGI.

RNA-seq data analysis

Transcript abundance from RNA-seq reads was quantified with Salmon [54] and used to test for differential expression with a negative binomial distribution model implemented in the DESeq2 [55] package from Bioconductor [56]. Genes with a minimum fold change of 1.25-fold and an adjusted p-value (q-value) of < 0.1 were considered differentially expressed. Venn diagrams were drawn for overlapping sets of upregulated and downregulated genes. In order to increase the power for enrichment analyses, a less conservative significance threshold of nominal p < 0.05 was used to select differentially expressed genes (DEG) for each between-group comparison to be used as input in iPathwayGuide (ADVAITA Bioinformatics, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) [57–59] to determine the enriched biological processes. Volcano plots were used to display differential gene expression between Nlrp3+/+ dams injected with S100B and Nlrp3−/− dams injected with S100B. The top ten enriched Biological Processes (BP) are shown in horizontal bar charts from the most to least significant adjusted p-value.

Embryo transfer

Superovulation was performed by the intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of 5 IU/100 μL of pregnant mare serum gonadotropin (PMGS; cat# HOR-272, ProSpec, Rehovot, Israel) and 5 IU/100 μL of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG; cat# CG-5; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) into eight- to nine-week-old female Nlrp3+/+ or Nlrp3−/− mice. Next, the superovulated mice were mated with male mice of the same genotype overnight. Next morning, female mice with a vaginal plug were utilized as embryo donors. Simultaneously, female Nlrp3−/− or Nlrp3+/+ mice were mated with vasectomized males of the same genotype. Pseudopregnant mice with a vaginal plug were utilized as embryo recipients. Day 0.5 embryos from the plugged donor female mice were collected and cultured in the global media (cat# LGGG-020; Cooper Surgical, Trumbull, CT, USA) supplemented with 2% bovine serum albumin (BSA; cat# A9576; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). At 0.5 dpc, the female recipient mice were anesthetized with 100 mg/kg of ketamine hydrochloride (Henry Schein, Melville, NY, USA) and 13.5 mg/kg of xylazine (AnaSed, AKORN, Lake Forest, IL, USA) and placed in a prone position, followed by back fur removal with an electric clipper and skin sterilization with iodine. Next, 50 μL of Ethiqa XR (1.3 mg/mL; Fidelis Pharmaceuticals, LLC, New Jersey, US) was subcutaneously (S.C.) injected into the female recipient mice. A skin incision of approximately 1 cm was made along the dorsal midline of the mice. The skin over the left ovary was pulled back and the abdominal wall was cut to expose the left ovary and oviduct. Seven-to-ten embryos from donor female mice with opposing genotypes (Nlrp3−/− donor embryos for Nlrp3+/+ recipients and vice versa) were transferred into the oviduct via infundibulum by tipped glass pipette. The same number of embryos were transferred into the right oviduct using the same procedure. The skin was closed by PDS II (polydioxanone) suture (cat# Z463G; Ethicon, Raritan, NJ, USA) and the recipient female mice were placed on a heating pad until they regained full motor function. The weight and condition of the recipient were monitored daily. The pregnancy of recipient mice was confirmed by a weight gain of ≥ 2 grams by 12.5 dpc. The resulting Nlrp3−/− dams carrying Nlrp3+/+ fetuses and Nlrp3+/+ dams carrying Nlrp3−/− fetuses were utilized to evaluate pregnancy conditions and neonatal outcomes in a model of S100B-induced intra-amniotic inflammation, as described above.

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism (v9.0.2; GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA) and the R package (https://www.r-project.org/). The Fisher’s exact test was used to compare the rates of preterm birth. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were used to plot and compare the gestational length data and neonatal survival data (Gehan-Breslow-Wilcoxon test). Kruskal-Wallis tests followed by post-hoc tests were performed to assess the statistical significance of neonatal weights. Mann-Whitney U-tests were performed to assess the statistical significance of neonatal mortality, umbilical artery peak systolic velocity, protein expression, mRNA expression, and absolute cell counts. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Nlrp3-deficient mice are resistant to S100B-induced preterm birth and neonatal mortality

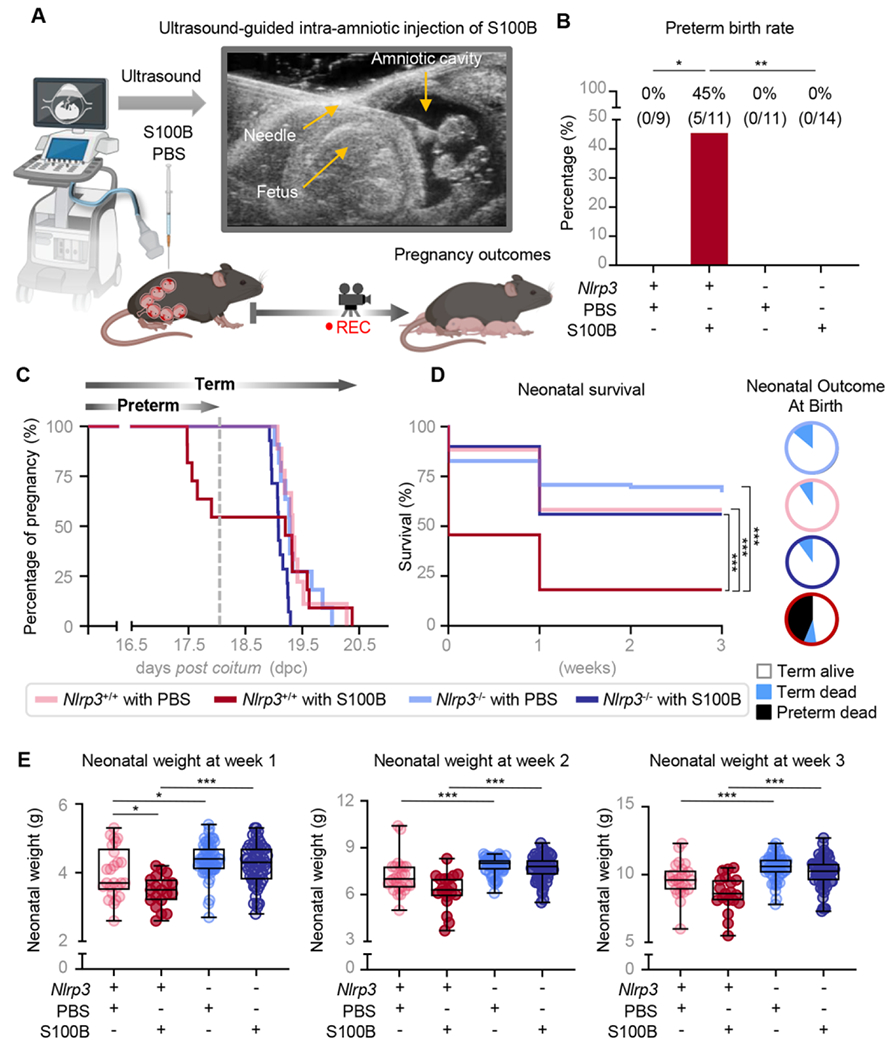

We have previously shown that the intra-amniotic administration of alarmins (e.g., S100B) causes preterm birth by inducing intra-amniotic inflammation, which includes the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome [24, 25]. To evaluate the role of NLRP3 signaling in the pathophysiology of sterile intra-amniotic inflammation-induced preterm labor and birth, we used wild type (WT; Nlrp3+/+) and Nlrp3-deficient (Nlrp3−/−) mice. Wild type and Nlrp3−/− dams underwent the ultrasound-guided intra-amniotic injection of the alarmin S100B or PBS (vehicle control) in late gestation [16.5 days post coitum (dpc)] (Fig 1A). Consistent with our prior report [24], the intra-amniotic injection of S100B in WT mice induced a 45% rate of preterm birth, further validating this animal model. Strikingly, none of the Nlrp3−/− dams injected with S100B delivered preterm (Fig 1B). All control dams injected with PBS delivered at term regardless of Nlrp3 expression (Fig 1B). Accordingly, the shortest gestational lengths were observed for WT dams that received intra-amniotic injection of S100B (Fig 1C). Thus, these data indicate that Nlrp3 deficiency confers resistance to preterm birth in the setting of sterile intra-amniotic inflammation.

Fig 1. Nlrp3-deficient mice are resistant to S100B-induced preterm birth and neonatal mortality.

(A) Pregnant Nlrp3+/+ and Nlrp3−/− mice were intra-amniotically injected under ultrasound guidance with S100B (60 ng/25 μL; Nlrp3+/+ mice, n = 11; Nlrp3−/− mice, n = 14) or PBS (Nlrp3+/+ mice, n = 9; Nlrp3−/− mice, n = 11) on 16.5 days post coitum (dpc). (B) Rates of preterm birth among Nlrp3+/+ and Nlrp3−/− mice injected with S100B or PBS. P-values were determined using the Fisher’s exact test. (C) Gestational lengths of WT and Nlrp3−/− mice injected with S100B or PBS are depicted as Kaplan-Meler survival curves. P-values were determined using the Gehan-Breslow-Wilcoxon test. (D) Survival rates of neonates born to Nlrp3+/+ or Nlrp3−/− dams up to three weeks of age are displayed as Kaplan-Meler survival curves. P-values were determined using the Gehan-Breslow-Wilcoxon test. Neonatal outcomes are displayed as proportions in pie charts (white = term delivery, born alive; blue = term delivery, born dead; black = preterm delivery, born dead). (E) Weights (g) of neonates born to Nlrp3+/+ or Nlrp3−/− mice injected with S100B (Nlrp3+/+ neonates, n = 19; Nlrp3−/− neonates, n = 62) or PBS (Nlrp3+/+ neonates, n = 25; Nlrp3−/− neonates, n = 63) across the first three weeks of life. P-values were determined using the Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s post-hoc test. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

Preterm birth is associated with devastating short- and long-term consequences for the offspring [60–63]. Therefore, we next assessed the outcomes of neonates born to WT and Nlrp3−/− dams injected with S100B during the first three weeks of life. While a high proportion of neonates born to WT dams injected with S100B were delivered preterm and died shortly after birth, the majority of neonates born to Nlrp3−/− dams injected with S100B were delivered at term and were viable (Fig 1D). Furthermore, both WT and KO dams injected with PBS delivered term viable neonates (Fig 1D). Surviving neonates born to S100B-injected Nlrp3−/− dams thrived, displaying significantly higher weights compared to those born to S100B-injected WT dams across the first three weeks of life (Fig 1E). These data indicate that the deleterious effects on neonatal survival induced by sterile intra-amniotic inflammation are abrogated in dams deficient for Nlrp3.

By directly comparing WT mice injected with S100B with those injected with saline; we have previously reported that alarmins induce preterm birth and neonatal mortality by triggering an inflammatory response in the amniotic cavity and maternal-fetal interface [24]. Therefore, we hereafter focused on directly comparing WT and Nlrp3−/− dams injected with S100B to decipher the NLPR3-driven mechanisms underlying pregnancy and neonatal outcomes in the setting of sterile intra-amniotic inflammation.

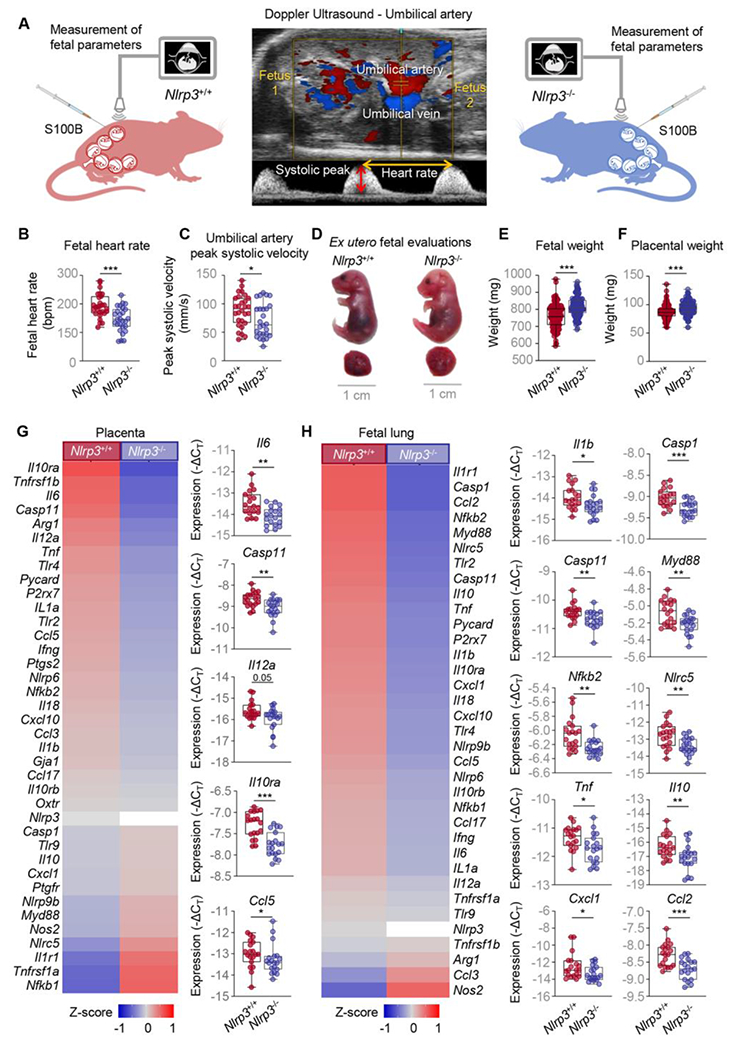

Nlrp3 deficiency impedes S100B-induced fetal inflammatory responses

Our previous studies have shown that the nature of the inflammatory response triggered by alarmins (i.e., sterile intra-amniotic inflammation) is different from that initiated by microorganisms (i.e., intra-amniotic infection) in the amniotic cavity [22, 30, 64–67]. Specifically, by using animal models we have observed that alarmin-induced intra-amniotic inflammation [24] is milder than that induced by microbes [68, 69]. Indeed, fetuses from dams injected with alarmins do not display differences in fetal and placental weights compared to control mice injected with saline, despite increased concentrations of pro-inflammatory mediators in the amniotic cavity [24]. Consistently, using high-resolution Doppler ultrasound (Fig 2A) we found that the intra-amniotic injection of S100B in WT mice did not alter the fetal heart rate or umbilical artery blood flow (Fig S1A&B), parameters indicative of fetal wellbeing [70, 71]. In Nlrp3−/− mice, intra-amniotic injection of S100B reduced the fetal heart rate without causing bradycardia (Fig 2B), as observed in compromised fetuses [43, 46, 47]. Nlrp3 deficiency also decreased the peak systolic velocity, indicating improved placental blood flow (Fig 2C). To complement these in utero observations, ex utero evaluation of fetal wellbeing was also performed in WT and Nlrp3−/− mice. Overall, Nlrp3−/− fetuses of dams injected with S100B appeared less reddish and inflamed compared to those of WT dams (Fig 2D), and fetal and placental growth were enhanced (Fig 2E&F). To further elucidate the inflammatory pathways truncated in the fetal compartment by Nlrp3 deficiency, the placenta and fetal organs traditionally affected by prematurity (i.e., lung, intestine, and brain) [72–74] were collected from WT and Nlrp3−/− dams injected with S100B and targeted gene expression was evaluated. Nlrp3 deficiency dampened the expression of several inflammatory mediators in all fetal organs (Fig 2G&H and Fig S2A&B); specifically, the placenta and fetal lung (Fig 2G&H). In the placenta, Nlrp3 deficiency resulted in reduced expression of Il6, Casp11, Il12a, Il10ra, and Ccl5 in response to S100B (Fig 2G). In the fetal lung, Nlrp3 deficiency resulted in reduced expression of Il1b, Casp1, Casp11, Myd88, Nfkb2, Nlrc5, Tnf, Il10, Cxcl1, and Ccl2 (Fig 2H). Taken together, these data show that Nlrp3 deficiency impedes fetal inflammatory responses driven by S100B, which results in improved neonatal outcomes.

Fig 2. Nlrp3 deficiency impedes S100B-induced fetal inflammatory responses.

(A) Pregnant Nlrp3+/+ and Nlrp3−/− mice were intra-amniotically injected under ultrasound guidance with S100B (60 ng/25 μL; Nlrp3+/+ mice, n = 19; Nlrp3−/− mice, n = 19) in each amniotic sac on 16.5 days post coitum (dpc). Doppler ultrasonography was used to assess umbilical artery peak systolic velocity on 17.5 dpc in four fetuses from each of seven dams per study group (Nlrp3+/+ dams n = 7, fetuses n = 28; Nlrp3−/− dams n = 7, fetuses n = 27). Placenta and other fetal tissues were collected at 17.5 dpc. A representative Doppler ultrasound image of the umbilical artery evaluation is shown. (B) Fetal heart rate and (C) umbilical artery peak systolic velocities of Nlrp3+/+ and Nlrp3−/− mice injected with S100B. P-values were determined using the Mann-Whitney U-test. (D) Representative images showing fetuses and placentas from Nlrp3+/+ and Nlrp3−/− mice injected with S100B. (E) Fetal and (F) placental weights from Nlrp3+/+ and Nlrp3−/− mice injected with S100B. P-values were determined using the Mann-Whitney U-test. Heatmap representation and box plots depicting gene expression (−ΔCT) of immune mediators in the (G) placenta and (H) fetal lung from Nlrp3+/+ and Nlrp3−/− mice injected with S100B. Data are shown as box and whisker plots where midlines indicate medians, boxes indicate interquartile ranges, and whiskers indicate minimum and maximum values. P-values were determined using the Mann-Whitney U-test. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. See also Fig S1&S2.

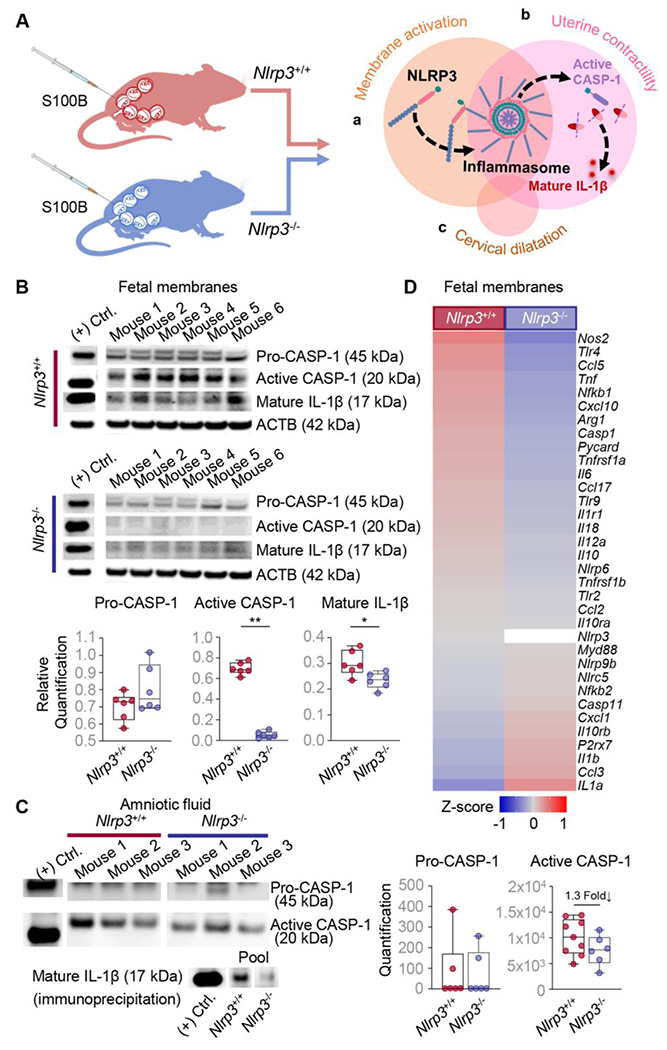

Nlrp3 deficiency impedes the S100B-induced intra-uterine inflammatory response

Our prior investigations have shown that NLRP3 inflammasome activation is a key component of the physiologic common pathway of labor in humans [31, 75–77], which intra-uterine components include fetal membrane activation, uterine contractility and inflammation, and cervical dilatation [40–42]. Using animal models, we have also shown that intra-uterine NLRP3 inflammasome activation is required for the onset of preterm labor induced by microbial products, which involves an exacerbated inflammatory response [43, 51]. However, the role of the NLRP3 inflammasome in the intra-uterine response triggered by alarmins has not been established. To fill this gap in knowledge, we first explored whether S100B induced the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome, as evidenced by cleavage of CASP-1 and the processing of mature IL-1β, in the intra-amniotic space (i.e., fetal membranes and amniotic fluid) in WT and Nlrp3−/− mice (Fig 3Aa). Consistent with prior reports [24], the intra-amniotic injection of S100B induced the activation of CASP-1 and maturation of IL-1β in the fetal membranes and amniotic fluid of WT dams (Fig S3A–C). Nevertheless, activation of CASP-1 and maturation of IL-1β were ablated in the fetal membranes and amniotic fluid of Nlrp3−/− dams upon S100B injection (Fig 3B&C). Nlrp3 deficiency also dampened the S100B-induced expression of multiple inflammatory mediators in the fetal membranes (Fig 3D).

Fig 3. Nlrp3 deficiency impedes the S100B-induced intra-uterine inflammatory response.

(A) Pregnant Nlrp3+/+ and Nlrp3−/− mice were injected with S100B (60 ng/25 μL) in each amniotic sac on 16.5 days post coitum (dpc). Fetal membranes and amniotic fluid were collected from each sac on 17.5 dpc. The representative diagram illustrates NLRP3 inflammasome activation in each component of the common pathway of parturition: (Aa) fetal membrane activation, (Ab) uterine contractility, and (Ac) cervical dilatation. (B) Immunoblotting and relative quantification of pro-CASP-1, active CASP-1, and mature IL-1β expression in the fetal membranes (n = 6 per group). (C) Immunoblotting and quantification of pro-CASP-1 and active CASP-1 expression was performed on amniotic fluid samples (n = 6 - 9 per group). Representative immunoblot images are shown that depict n = 3 samples per group in each. Immunoblotting of mature IL-1β expression in pooled amniotic fluid samples (n = 5 per group) immunoprecipitated with anti-cleaved IL-1β antibody is also shown. (D) Heatmap representation of inflammatory and inflammasome-associated gene expression in the fetal membranes. Data are shown as box and whisker plots where midlines indicate medians, boxes indicate interquartile ranges, and whiskers indicate minimum and maximum values. P-values were determined using the Mann-Whitney U-test. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01. (+) Ctrl.; positive control. See also Fig S3.

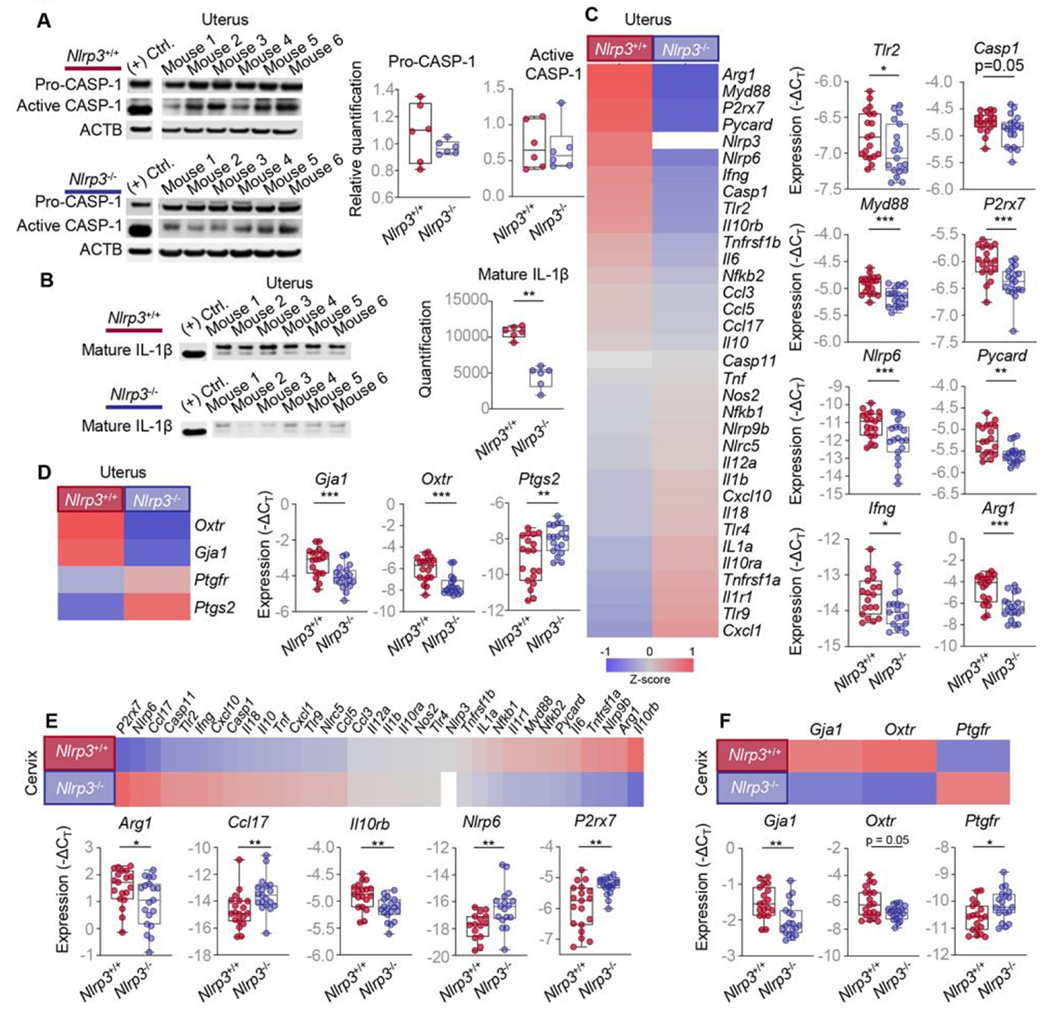

Next, we explored whether Nlrp3 deficiency interferes with uterine contractility and the inflammatory milieu (Fig 3Ab). Uterine tissues from WT and Nlrp3−/− dams were evaluated for inflammasome activation readouts and expression of uterine activation proteins. As anticipated, based on prior in vitro reports [78, 79], the intra-amniotic injection of S100B induced the activation of CASP-1 and maturation of IL-1β in the uterine tissues of WT mice (Fig S4A&B). By contrast, a rise in the active forms of CASP-1 in the uteri of Nlrp3−/− dams injected with S100B was not observed (Fig 4A); yet, the levels of mature IL-1β were reduced compared to S100B-injected WT dams (Fig 4B). Furthermore, the expression of several S100B-induced inflammatory mediators was attenuated in the uterine tissues of Nlrp3−/− dams (Fig 4C), and aberrant expression of uterine activation proteins was also observed (Fig 4D).

Fig 4. Nlrp3 deficiency limits the S100B-induced uterine and cervical inflammatory response and contractility.

Pregnant Nlrp3+/+ and Nlrp3−/− mice were intra-amniotically injected under ultrasound guidance with S100B (60 ng/25 μL; Nlrp3+/+ mice, n = 19; Nlrp3−/− mice, n = 19) in each amniotic sac on 16.5 days post coitum (dpc). Uterine and cervical tissues were collected on 17.5 dpc. (A) Immunoblotting and relative quantification of pro-CASP-1 and active CASP-1 expression in the uterine tissues (n = 6 per group). (B) Immunoblotting and quantification of mature IL-1β expression in the uterine tissues lysates immunoprecipitated with anti-cleaved IL-1β antibody (n = 6 per group). (C) Heatmap representation and box and whisker plots of expression (−ΔCT) of specific inflammatory and inflammasome-associated gene expression in the uterine tissues (n = 19 per group). (D) Heatmap representation and box plots showing the expression (−ΔCT) of specific contractility-associated genes (Gja1, Oxtr, Ptgs2, and Ptgfr) in the uterine tissues (n = 19 per group). (E) Heatmap representation and box plots showing the expression (−ΔCT) of specific inflammatory or inflammasome-associated genes in the cervical tissues (n = 19 per group). (F) Heatmap representation and box plots showing the expression (−ΔCT) of specific contractility-associated genes (Gja1, Oxtr, and Ptgfr) in the cervical tissues (n = 19 per group). Data are shown as box and whisker plots where midlines indicate medians, boxes indicate interquartile ranges, and whiskers indicate minimum and maximum values. P-values were determined using the Mann-Whitney U-test. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. See also Fig S4.

We and others have demonstrated that cervical dilatation does not require inflammasome activation [43, 80]; yet, it is well established that this process involves an inflammatory milieu during parturition [81–83]. Therefore, we also evaluated whether Nlrp3 deficiency altered the gene expression of several inflammatory mediators and contractility proteins in the cervix (Fig 3Ac). Notably, the expression of both inflammatory mediators and contractility proteins was dysregulated in the cervix of Nlrp3−/− dams compared to WT dams in response to S100B (Fig 4E&F).

Collectively, these results indicate that Nlrp3 deficiency limits the intra-uterine inflammatory responses triggered by S100B, which include inflammasome activation. These data provide molecular evidence showing that Nlrp3−/− dams do not undergo the common cascade of preterm parturition in the setting of sterile intra-amniotic inflammation.

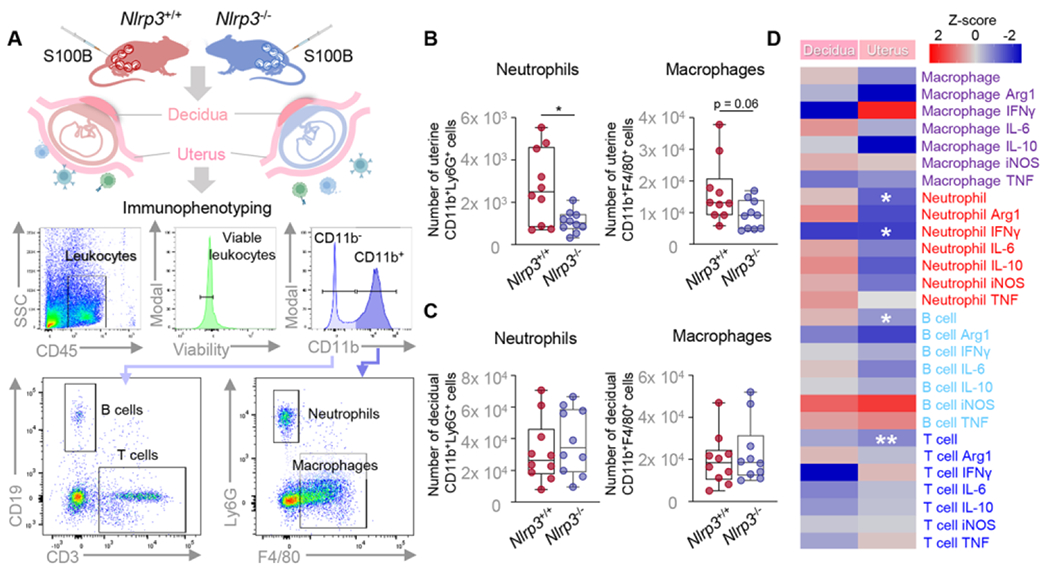

Nlrp3 deficiency impairs leukocyte recruitment and/or function in the uterus and decidua

Leukocyte recruitment into the reproductive tissues is a hallmark of labor [81, 84–87]. Therefore, we next evaluated whether Nlrp3 deficiency impairs the infiltration and function of immune cells implicated in the local inflammatory milieu accompanying labor. Specifically, we used flow cytometry to quantify the infiltration of major immune cell populations (e.g., neutrophils, macrophages, T cells, and B cells) in the uterine and decidual tissues of WT and Nlrp3−/− dams in response to S100B (Fig 5A). Nlrp3 deficiency impaired neutrophil and macrophage influx in the uterine tissues (Fig 5B). Specifically, fewer uterine neutrophils expressing IFNγ were found in Nlrp3−/− dams compared to WT dams in response to S100B (Fig 5D). In addition, uterine T- and B-cell infiltration was also reduced by Nlrp3 deficiency (Fig 5D). However, leukocyte infiltration was not altered in the decidual tissues by Nlrp3 deficiency (Fig 5C&D). Nonetheless, the S100B-induced gene expression profile of the decidual tissues from Nlrp3−/− dams differed from that of WT dams (Fig S5A–C).

Fig 5. Nlrp3 deficiency impairs leukocyte recruitment in the uterus and decidua.

(A) Pregnant Nlrp3+/+ and Nlrp3+/+ mice were intra-amniotically injected under ultrasound guidance with S100B (60 ng/25 μL; Nlrp3+/+ mice, n = 10; Nlrp3−/− mice, n = 10) in each amniotic sac on 16.5 days post coitum (dpc). Decidual and uterine tissues were collected on 17.5 dpc. A representative gating strategy for the phenotyping of leukocytes isolated from the decidual and uterine tissues is shown. Total numbers of neutrophils and macrophages in the (B) uterine and (C) decidual tissues isolated from Nlrp3+/+ and Nlrp3−/− mice injected with S100B. (D) Heatmap representation of phenotypic changes of decidual and uterine leukocytes from S100B-injected Nlrp3+/+ mice compared to S100B-injected Nlrp3−/− mice. Data are shown as box and whisker plots where midlines indicate medians, boxes indicate interquartile ranges, and whiskers indicate minimum and maximum values. P-values were determined using the Mann-Whitney U-test. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

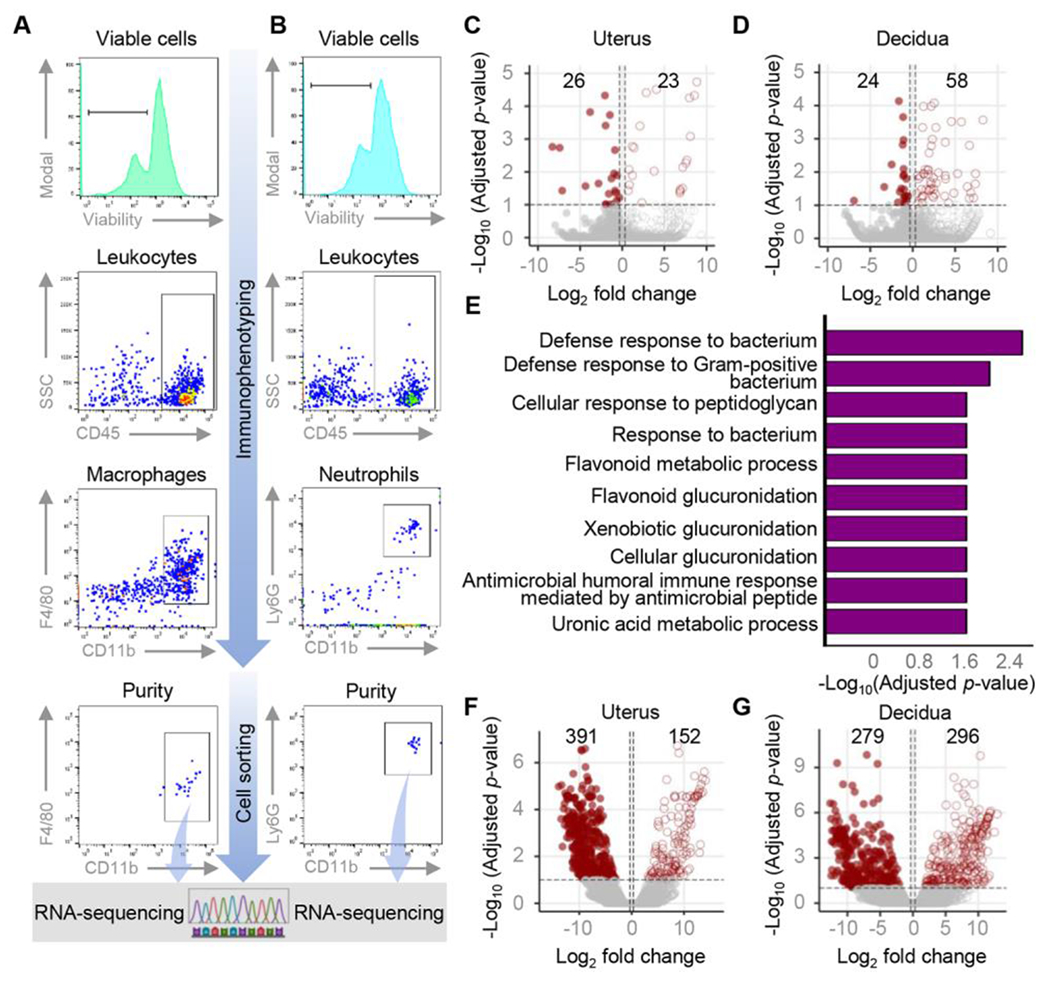

Next, we investigated whether Nlrp3 deficiency induced functional changes in uterine and decidual macrophages and neutrophils. We sorted macrophages (Fig 6A) and neutrophils (Fig 6B) by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) from uterine and decidual tissues and performed RNA sequencing. The transcriptomic activity of uterine (Fig 6C) and decidual (Fig 6D macrophages was altered in response to S100B in Nlrp3−/− mice, as indicated by the numbers of differentially expressed genes (DEGs). Specifically, Nlrp3 deficiency caused altered expression of 49 DEGs (26 downregulated, 23 upregulated) by uterine macrophages and 82 DEGs (24 upregulated, 58 downregulated) by decidual macrophages in response to S100B (Fig 6C&D and Tables S3–4). In uterine macrophages, DEGs were significantly enriched for biological processes related to host defense mechanisms, such as “defense response to bacterium”, “response to bacterium”, and “antimicrobial humoral immune response mediated by antimicrobial peptide” (Fig 6E). By contrast, DEGs in decidual macrophages were involved, but not significantly, in processes related to “negative regulation of ion transmembrane transport”, “response to bacterium”, “regulation of peptidase activity”, and “response to wounding” (Fig S6). Interestingly, Nlrp3 deficiency caused a drastic difference in transcriptomic activity in both uterine and decidual neutrophils (Fig 6F&G). In particular, neutrophils isolated from the uterus exhibited 543 (391 downregulated, 152 upregulated) DEGs, and those from the decidua exhibited 575 (279 downregulated, 296 upregulated) in response to S100B (Fig 6F&G and Tables S5–6). However, these DEGs were not enriched for any known biological processes in the Gene Ontology (GO) database.

Fig 6. Nlrp3 deficiency impairs leukocyte function in the uterus and decidua.

Pregnant Nlrp3+/+ and Nlrp3−/− mice were intra-amniotically injected under ultrasound guidance with S100B (60 ng/25 μL; Nlrp3+/+ mice, n = 8; Nlrp3−/− mice, n = 8) in each amniotic sac on 16.5 days post coitum (dpc). Uterine and decidual tissues were collected on 17.5 dpc. Immunophenotyping followed by sorting was utilized to isolate (A) macrophages and (B) neutrophils for RNA-seq. A representative gating strategy used for the sorting of macrophages and neutrophils is shown. (C) Volcano plot showing the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between uterine macrophages from Nlrp3−/− and Nlrp3+/+ dams injected with S100B. (D) Volcano plot showing the DEGs between decidual macrophages from Nlrp3−/− and Nlrp3+/+ dams injected with S100B. (E) Biological processes enriched when comparing uterine macrophages from Nlrp3−/− and Nlrp3+/+ dams injected with S100B. (F) Volcano plot showing the DEGs between uterine neutrophils from Nlrp3−/− and Nlrp3+/+ dams injected with S100B. (G) Volcano plot showing the DEGs between decidual neutrophils from Nlrp3−/− and Nlrp3+/+ dams injected with S100B. See also Fig S5.

Together, these data show that Nlrp3 deficiency alters the leukocyte influx in the uterine tissues without affecting the numbers of decidual immune cell types in response to S100B. Yet, Nlrp3 deficiency profoundly impacts the functional properties of maternal neutrophils and macrophages in the uterus and decidua. These data indicate that the loss of NLRP3 signaling impairs leukocyte influx and/or function, which may contribute to the resistance to alarmin-induced preterm birth observed in Nlrp3−/− dams.

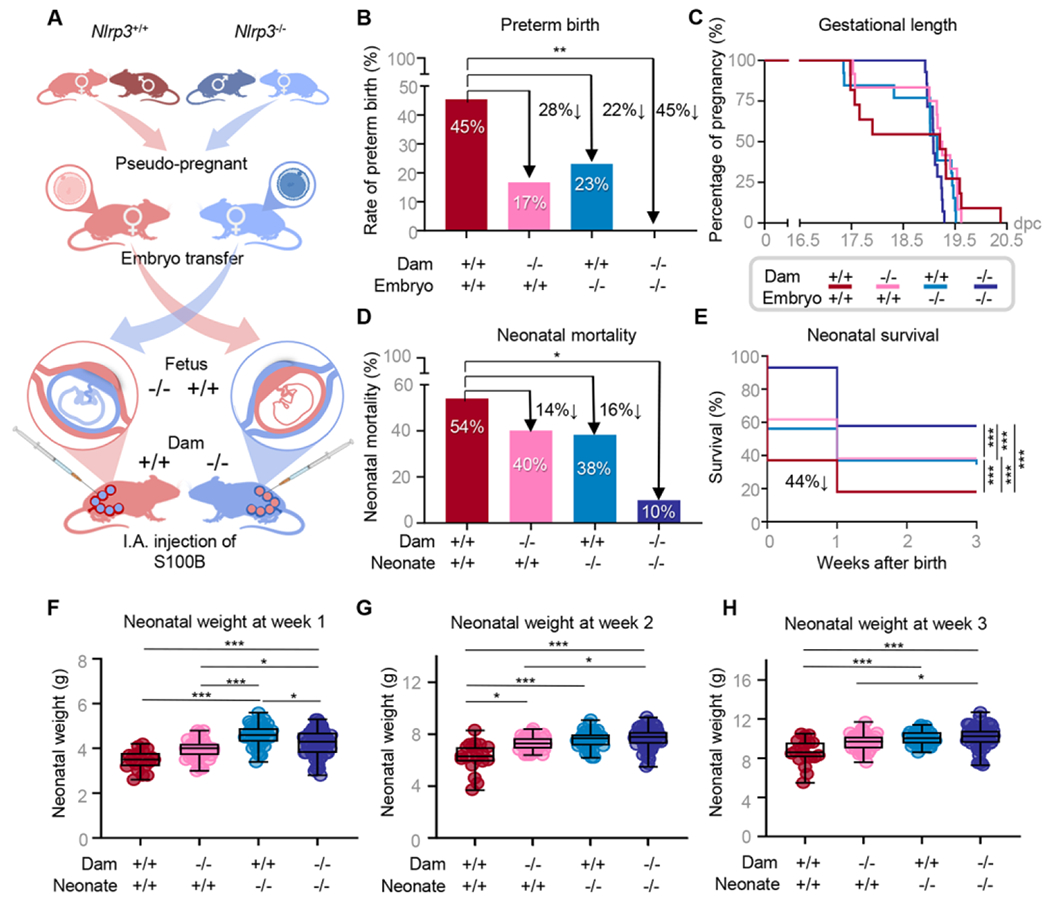

Both maternal and fetal NLRP3 signaling contribute to preterm birth and neonatal mortality in the context of sterile intra-amniotic inflammation

Thus far, our data have shown that Nlrp3 deficiency interferes with the common pathway of labor and the intra-uterine inflammatory response induced by intra-amniotic S100B, providing resistance to preterm birth and neonatal mortality. However, such processes involve both maternal and fetal tissues, and up to this point the contribution of each individual is unclear. To independently evaluate the maternal and fetal contribution to Nlrp3 signaling, we devised an embryo transfer strategy in which WT (Nlrp3+/+) or Nlrp3−/− embryos are implanted into pseudo-pregnant dams of the opposing genotype, yielding two experimental groups (Fig 7A). Specifically, donor WT embryos were transferred to recipient pseudo-pregnant Nlrp3−/− mice, and donor Nlrp3−/− embryos were transferred to recipient pseudo-pregnant WT (Nlrp3+/+) mice (Fig 7A). WT/WT and Nlrp3−/−/Nlrp3−/− maternal-fetal dyads (as shown in Fig 1B) were also included as controls. As previously shown, a significantly lower rate of preterm birth following maternal S100B injection was observed for Nlrp3−/− neonates born to Nlrp3−/− dams (0/14, 0%) relative to WT neonates born to WT dams (5/11, 45%) (Fig 7B). Notably, there was a clear reduction in the rates of preterm birth for Nlrp3+/+ neonates born to Nlrp3−/− dams (2/12, 17%) and Nlrp3−/− neonates born to Nlrp3+/+ dams (3/13, 23%) compared to WT dyads (Fig 7B). Accordingly, these findings were reflected by the extended gestational lengths among the experimental groups (Fig 7C). Compared to WT neonates born to WT dams, the rate of neonatal mortality following maternal S100B injection was significantly reduced for Nlrp3−/− neonates born to Nlrp3−/− dams (10%), and a modest (non-significant) reduction was observed for Nlrp3+/+ neonates born to Nlrp3−/− dams (40%) and Nlrp3−/− neonates born to Nlrp3+/+ dams (38%) (Fig 7D). When evaluating neonatal parameters across the first three weeks of life, more striking differences emerged. The rate of neonatal survival was significantly higher for Nlrp3−/− neonates born to Nlrp3−/− dams than any of the other three groups (Fig 7E). Interestingly, by week three, the survival rates for neonates from either experimental group (Nlrp3+/+ neonates born to Nlrp3−/− dams and Nlrp3−/− neonates born to Nlrp3+/+ dams) were significantly higher than for WT neonates born to WT dams (Fig 7E). Moreover, higher neonatal weight across the first three weeks of life was consistently observed for Nlrp3+/+ neonates born to Nlrp3−/− dams, as compared to WT neonates born to WT dams (Fig 7F–H). Hence, either maternal or fetal Nlrp3 deficiency is protective against S100B-induced neonatal mortality by three weeks of age, while fetal Nlrp3 deficiency is further associated with improved neonatal growth across the first three weeks of life. These results show that maternal and fetal Nlrp3 signaling contribute to the pathological processes leading to preterm birth and neonatal mortality in the context of sterile intra-amniotic inflammation.

Fig 7. Maternal and fetal NLRP3 signaling contributes to preterm birth and neonatal mortality in the context of sterile intra-amniotic inflammation.

(A) Mating strategies, embryo transfer, and resulting fetal genotypes. Nlrp3+/+ carrying Nlrp3+/+ fetuses, Nlrp3+/+ dams carrying Nlrp3−/− fetuses, Nlrp3−/− dams carrying Nlrp3+/+ fetuses, and Nlrp3−/− dams carrying Nlrp3−/− fetuses were intra-amniotically injected under ultrasound guidance with S100B (60 ng/25 μL) on 16.5 days post coitum (dpc) (n = 11 – 14 per group). (B) Preterm birth rates. P-values were determined using the Fisher’s exact test. (C) Gestational lengths depicted as Kaplan-Meler survival curves. (D) Neonatal mortality rates. P-values were determined using the Fisher’s exact test. (E) Neonatal survival displayed as Kaplan-Meler survival curves. P-values were determined using the Gehan-Breslow-Wilcoxon test. (F-H) Weights (g) of neonates across the first three weeks of life. P-values were determined using the Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons test. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. See also Fig S6.

DISCUSSION

In the current study, we showed that Nlrp3-deficient mice are resistant to S100B-induced preterm birth and neonatal mortality. These results are in line with previous in vitro and in vivo studies undertaken by our group demonstrating a role for the NLRP3 inflammasome in sterile intra-amniotic inflammation-associated preterm birth. Specifically, we have demonstrated a causal link between the intra-amniotic injection of alarmins, such as S100B, and preterm labor and birth [23–27]. Moreover, murine and human fetal membranes exposed to alarmins display increased expression of NLRP3 inflammasome components compared to controls, suggesting activation of this inflammasome in the context of sterile intra-amniotic inflammation [24, 25, 29]. As an initial proof of concept, we previously showed that NLRP3 blockade with a specific inhibitor, MCC950, prevented alarmin-induced preterm labor and birth [24]; yet, the mechanisms whereby the inhibition of this inflammasome prevents preterm labor and birth, as well as the fetal and maternal contributions to NLRP3 signaling, had not been explored. As the logical follow-up to these findings, herein we demonstrated a central role for the NLRP3 inflammasome in the pathologic activation of the common pathway of parturition induced by S100B by showing that caspase-1 activation and mature IL-1β concentrations were reduced in the intra-uterine tissues of Nlrp3−/− mice in response to this alarmin. Importantly, the inflammatory milieu in each tissue component of the common pathway of parturition was diminished in Nlrp3−/− dams, which is consistent with the impaired NLRP3 inflammasome activation in these compartments. Therefore, the data provided herein further expand on our prior observations by providing deeper mechanistic insight into the molecular and cellular processes that are regulated by NLRP3 in the context of alarmin-induced preterm birth, further supporting a central role for the NLRP3 inflammasome as a regulator of the untimely (i.e., premature) activation of the common pathway of labor.

Another important finding of the current study is that NLRP3 is implicated in alarmin-driven inflammation in fetal organs, such as the placenta, lung, intestine, and brain, as demonstrated by the reduced inflammatory response observed in fetuses from Nlrp3−/− dams injected with S100B. These results are consistent with the adverse outcomes of neonates born to women with histologic or clinical chorioamnionitis (the majority of whom display intra-amniotic inflammation [88, 89]) that include pulmonary dysfunction/damage (e.g., bronchopulmonary dysplasia, BPD [90, 91]), gastrointestinal disease (e.g., necrotizing enterocolitis, NEC [92, 93]), and neurologic disorders (e.g., cerebral palsy [94, 95]). Interestingly, mice expressing a gain-of-function Nlrp3 allele displayed enhanced inflammasome activation resulting in abnormal lung development and died shortly after birth [96], further implicating aberrant NLRP3 inflammasome activation in early-life pulmonary injury. A prior study using a model of BPD reported caspase-1 activation and elevated IL-1β together with reduced alveolarization in neonatal mice, findings that were reverted in Nlrp3−/− neonates [97]. Furthermore, treatment of the affected neonates with IL-1RA (to block IL-1β activity) or glyburide (to block NLRP3 inflammasome activation) similarly reduced inflammation and improved alveolarization [97]. Subsequently, a number of in vivo and in vitro studies have utilized various treatments that result in the blockade or dampening of the NLRP3 inflammasome to demonstrate improvements in models of pulmonary damage [98–101]. Similar results have been reported in in vivo and in vitro models of NEC, indicating the involvement of the NLRP3 inflammasome in intestinal injury [102–105]. Notably, the inhibition of this inflammasome using different broad or targeted approaches improved the survival of mice with NEC [102, 104, 105]. Finally, the upregulation of NLRP3 and inflammasome activation have been reported in a number of hypoxic-ischemic brain injury models [106, 107]; however, the potential neuroprotective effects of impaired NLRP3 inflammasome signaling in knockout mice were inconclusive [108, 109]. Regardless, treatments that directly or indirectly suppress NLRP3 inflammasome activation have generally resulted in improved outcomes after brain injury in animals [110–113]. Taken together, the above studies provide a plausible explanation to our results showing a reduced inflammatory response in fetal organs from mice lacking Nlrp3, and thus a consequent reduction in neonatal mortality.

The inflammatory nature of labor is characterized by the infiltration of leukocytes into the myometrium [81, 84, 114], decidua [81, 115], and cervix [81, 85, 116, 117] during the physiologic process of parturition. The pathologic process of preterm labor occurring in the context of intra-amniotic inflammation is similarly characterized by a massive leukocyte influx [43, 118–120]. In the current study, we demonstrated that there is diminished infiltration of neutrophils in the uterine tissues of Nlrp3-deficient mice in response to S100B. This finding suggests that the loss of NLRP3-driven signaling can influence the recruitment of pro-inflammatory leukocytes during labor. In addition to impaired neutrophil infiltration, we found that the transcriptomic profile of neutrophils and macrophages was perturbed in the uterine and decidual tissues of Nlrp3-deficient mice injected with S100B. Prior transcriptomic investigations of the myometrium [121–125], cervix [80, 126, 127], and gestational tissues (i.e., placenta and decidua/chorioamniotic membranes) [66, 128, 129] indicated an upregulated expression of inflammation-related transcripts that accompanies labor. Recent investigation of the human myometrium in labor using single-cell RNA-sequencing (scRNA-seq) indicated distinct transcriptomic profiles of accumulating monocytes and macrophages, and furthermore pointed to the involvement of these cells in cell-cell signaling networks that may be critical for parturition [114]. Therefore, our findings point to a key role for NLRP3 in modifying the transcriptomic profiles of neutrophils and monocytes/macrophages responding to sterile intra-amniotic inflammation, which may in turn affect their ability to infiltrate the reproductive and gestational tissues and its participation in the process of labor.

The current study demonstrates that both the mother and the fetus contribute to the mechanisms implicated in preterm birth driven by alarmins. This finding builds upon our prior observation that maternal and fetal NLRP3 signaling is also implicated in the intra-amniotic inflammatory response to microbial products [43], which mirrors the clinical scenario of intra-amniotic infection. Prior studies had suggested that the mother was the primary contributor to the mechanisms leading to preterm labor and birth [130–132]; yet, a growing body of evidence have pointed to a role for the fetus in regulating the onset of parturition [41, 42, 133–136]. Our results showing that the mother and fetus actively participate in the process of sterile intra-amniotic inflammation-associated preterm birth is clinically relevant and can promote the investigation of preventative strategies that consider both entities. Therefore, anti-inflammatory therapies are needed that are safe for the mother and fetus and can effectively cross the placenta. In this regard, we have recently demonstrated that betamethasone [26] and clarithromycin [28] can successfully prevent alarmin-induced preterm labor and birth in mice. Importantly, both therapies are safe for using during pregnancy and can cross the placenta to reach the fetus. Indeed, clarithromycin exerts an anti-inflammatory effect in the common pathway of labor and in fetal organs [28], and together with the current investigation indicates that targeting both the mother and the fetus is an effective strategy to prevent preterm labor and birth induced by alarmins.

Collectively, our current findings mechanistically demonstrate a key role for the NLRP3 inflammasome pathway in the alarmin-induced inflammatory milieu that accompanies preterm labor leading to preterm birth. We show that Nlrp3 deficiency dampens inflammatory signaling in the common pathway of labor, amniotic cavity, and fetal organs, providing a in vivo explanation for the observed resistance to alarmin-induced preterm birth and neonatal mortality in these mice. Moreover, leukocyte infiltration and functionality are also regulated by the NLRP3 molecule. Importantly, we establish the contributions of maternal and fetal NLRP3 signaling to the propagation of alarmin-induced inflammation, which further strengthens the concept that both the mother and fetus participate in the process of preterm parturition. Together, the data generated herein provide novel insight into the molecular underpinnings of preterm labor associated with sterile intra-amniotic inflammation and support the potential utility of targeting the NLRP3 pathway to prevent such an outcome and ameliorate adverse consequences for the offspring.

Supplementary Material

BRIEF COMMENTARY.

Background:

Preterm birth has devastating short- and long-term neonatal outcomes. Most preterm births are preceded by spontaneous preterm labor. Sterile intra-amniotic inflammation (SIAI), a condition associated with alarmins, has emerged as a prevalent etiology of preterm labor and birth. However, there is currently no treatment for SIAI.

Translational significance:

We demonstrate that Nlrp3 deficiency abrogates preterm birth and neonatal mortality induced by alarmins by interfering with the common pathway of parturition involving fetal and maternal inflammation. Therefore, targeting NLRP3 signaling may serve as a therapeutic approach to prevent SIAI-associated preterm labor and birth, thereby ameliorating adverse neonatal outcomes.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Catherine Demery-Poulos, MSc for her helpful feedback on the manuscript. This research was supported by the Perinatology Research Branch, Division of Obstetrics and Maternal-Fetal Medicine, Division of Intramural Research, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (NICHD/NIH/DHHS) under contract HHSN275201300006C. This research was also supported by the Wayne State University Perinatal Initiative in Maternal, Perinatal and Child Health (NGL and ALT). RR contributed to this work as part of his official duties as an employee of the U.S. federal government. Figures include art created with BioRender.

Abbreviations:

- ACTB

anti-β-actin

- BPD

Bronchopulmonary dysplasia

- CASP

Caspase

- CT

Cycle threshold

- DEGs

differentially expressed genes

- DPC

Days post coitum

- FACS

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting

- GO

Gene ontology

- hCG

human chorionic gonadotropin

- HMGB1

High mobility group box 1

- IFN

Interferon

- Ig

Immunoglobulin

- IL

Interleukin

- IP

Intra-peritoneal

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- mAbs

monoclonal antibodies

- NEC

Necrotizing enterocolitis

- NLRP3

Nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain, leucine-rich repeat, and pyrin domain-containing 3

- PBS

Phosphate-buffered saline

- PPROM

Preterm prelabor rupture of membranes.

- PSV

Peak systolic velocity

- scRNA-seq

Single-cell RNA-sequencing

- SIAI

Sterile intra-amniotic inflammation

- sPTL

spontaneous preterm labor

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The study was conducted at the Perinatology Research Branch, NICHD/NIH/DHHS, in Detroit, Michigan; the Branch has since been renamed as the Pregnancy Research Branch, NICHD/NIH/DHHS.

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing interests. The authors have read the journal’s policy on disclosure of potential conflicts of interest.

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

Data and code availability

Data generated in this study are included in the manuscript and/or in the supplemental materials. Generated RNA-Seq data were deposited in the NCBI’s Gene Expression Omnibus (accession number GSE217041)

References

- [1].Liu L, Oza S, Hogan D, et al. Global, regional, and national causes of under-5 mortality in 2000-15: an updated systematic analysis with implications for the Sustainable Development Goals. Lancet. 2016;388:3027–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Chawanpaiboon S, Vogel JP, Moller AB, et al. Global, regional, and national estimates of levels of preterm birth in 2014: a systematic review and modelling analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2019;7:e37–e46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].MacDorman MF, Matthews TJ, Mohangoo AD, Zeitlin J. International comparisons of infant mortality and related factors: United States and Europe, 2010. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2014;63:1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Goldenberg RL, Culhane JF, Iams JD, Romero R. Epidemiology and causes of preterm birth. Lancet. 2008;371:75–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Romero R, Dey SK, Fisher SJ. Preterm labor: one syndrome, many causes. Science. 2014;345:760–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Romero R, Sirtori M, Oyarzun E, et al. Infection and labor. V. Prevalence, microbiology, and clinical significance of intraamniotic infection in women with preterm labor and intact membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989;161:817–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].DiGiulio DB, Romero R, Amogan HP, et al. Microbial prevalence, diversity and abundance in amniotic fluid during preterm labor: a molecular and culture-based investigation. PLoS One. 2008;3:e3056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Novy MJ, Duffy L, Axthelm MK, et al. Ureaplasma parvum or Mycoplasma hominis as sole pathogens cause chorioamnionitis, preterm delivery, and fetal pneumonia in rhesus macaques. Reprod Sci. 2009;16:56–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Bastek JA, Gomez LM, Elovitz MA. The role of inflammation and infection in preterm birth. Clin Perinatol. 2011;38:385–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Romero R, Miranda J, Chaiworapongsa T, et al. A novel molecular microbiologic technique for the rapid diagnosis of microbial invasion of the amniotic cavity and intra-amniotic infection in preterm labor with intact membranes. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2014;71:330–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Combs CA, Gravett M, Garite TJ, et al. Amniotic fluid infection, inflammation, and colonization in preterm labor with intact membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;210:125 e1– e15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Romero R, Miranda J, Chaiworapongsa T, et al. Sterile intra-amniotic inflammation in asymptomatic patients with a sonographic short cervix: prevalence and clinical significance. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2015;28:1343–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Romero R, Miranda J, Chaemsaithong P, et al. Sterile and microbial-associated intra-amniotic inflammation in preterm prelabor rupture of membranes. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2015;28:1394–409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Romero R, Miranda J, Kusanovic JP, et al. Clinical chorioamnionitis at term I: microbiology of the amniotic cavity using cultivation and molecular techniques. J Perinat Med. 2015;43:19–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Burnham P, Gomez-Lopez N, Heyang M, et al. Separating the signal from the noise in metagenomic cell-free DNA sequencing. Microbiome. 2020;8:18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Lee J, Romero R, Kim SM, Chaemsaithong P, Yoon BH. A new antibiotic regimen treats and prevents intra-amniotic inflammation/infection in patients with preterm PROM. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2016;29:2727–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Oh KJ, Romero R, Park JY, et al. Evidence that antibiotic administration is effective in the treatment of a subset of patients with intra-amniotic infection/inflammation presenting with cervical insufficiency. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;221:140 e1– e18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Yoon BH, Romero R, Park JY, et al. Antibiotic administration can eradicate intra-amniotic infection or intra-amniotic inflammation in a subset of patients with preterm labor and intact membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;221:142 e1– e22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Kacerovsky M, Romero R, Stepan M, et al. Antibiotic administration reduces the rate of intraamniotic inflammation in preterm prelabor rupture of the membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;223:114 e1– e20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Matzinger P. An innate sense of danger. Semin Immunol. 1998;10:399–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Rider P, Voronov E, Dinarello CA, Apte RN, Cohen I. Alarmins: Feel the Stress. J Immunol. 2017;198:1395–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Romero R, Grivel JC, Tarca AL, et al. Evidence of perturbations of the cytokine network in preterm labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213:836 e1– e18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Gomez-Lopez N, Romero R, Plazyo O, et al. Intra-Amniotic Administration of HMGB1 Induces Spontaneous Preterm Labor and Birth. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2016;75:3–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Gomez-Lopez N, Romero R, Garcia-Flores V, et al. Inhibition of the NLRP3 inflammasome can prevent sterile intra-amniotic inflammation, preterm labor/birth, and adverse neonatal outcomes. Biol Reprod. 2019;100:1306–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Motomura K, Romero R, Garcia-Flores V, et al. The alarmin interleukin-1alpha causes preterm birth through the NLRP3 inflammasome. Mol Hum Reprod. 2020;26:712–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Galaz J, Romero R, Arenas-Hernandez M, et al. Betamethasone as a potential treatment for preterm birth associated with sterile intra-amniotic inflammation: a murine study. J Perinat Med. 2021;49:897–906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Motomura K, Romero R, Plazyo O, et al. The alarmin S100A12 causes sterile inflammation of the human chorioamniotic membranes as well as preterm birth and neonatal mortality in mice. Biol Reprod. 2021;105:1494–509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Galaz J, Romero R, Arenas-Hernandez M, et al. Clarithromycin prevents preterm birth and neonatal mortality by dampening alarmin-induced maternal-fetal inflammation in mice. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2022;22:503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Plazyo O, Romero R, Unkel R, et al. HMGB1 Induces an Inflammatory Response in the Chorioamniotic Membranes That Is Partially Mediated by the Inflammasome. Biol Reprod. 2016;95:130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Gomez-Lopez N, Romero R, Panaitescu B, et al. Inflammasome activation during spontaneous preterm labor with intra-amniotic infection or sterile intra-amniotic inflammation. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2018;80:e13049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Gomez-Lopez N, Motomura K, Miller D, et al. Inflammasomes: Their Role in Normal and Complicated Pregnancies. J Immunol. 2019;203:2757–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Martinon F, Burns K, Tschopp J. The inflammasome: a molecular platform triggering activation of inflammatory caspases and processing of proIL-beta. Mol Cell. 2002;10:417–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Guo H, Callaway JB, Ting JP. Inflammasomes: mechanism of action, role in disease, and therapeutics. Nat Med. 2015;21:677–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Black RA, Kronheim SR, Merriam JE, March CJ, Hopp TP. A pre-aspartate-specific protease from human leukocytes that cleaves pro-interleukin-1 beta. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:5323–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Kostura MJ, Tocci MJ, Limjuco G, et al. Identification of a monocyte specific pre-interleukin 1 beta convertase activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:5227–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Fantuzzi G, Dinarello CA. Interleukin-18 and interleukin-1 beta: two cytokine substrates for ICE (caspase-1). J Clin Immunol. 1999;19:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Romero R, Brody DT, Oyarzun E, et al. Infection and labor. III. Interleukin-1: a signal for the onset of parturition. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989;160:1117–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Romero R, Durum S, Dinarello CA, et al. Interleukin-1 stimulates prostaglandin biosynthesis by human amnion. Prostaglandins. 1989;37:13–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Romero R, Mazor M, Brandt F, et al. Interleukin-1 alpha and interleukin-1 beta in preterm and term human parturition. Am J Reprod Immunol. 1992;27:117–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Romero R. The preterm labor syndrome. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1994;734:414–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Norwitz ER, Robinson JN, Challis JR. The control of labor. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:660–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Parturition Smith R.. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:271–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Motomura K, Romero R, Galaz J, et al. Fetal and maternal NLRP3 signaling is required for preterm labor and birth. JCI Insight. 2022;7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Gomez-Lopez N, Romero R, Garcia-Flores V, et al. Inhibition of the NLRP3 inflammasome can prevent sterile intra-amniotic inflammation, preterm labor/birth, and adverse neonatal outcomesdagger. Biol Reprod. 2019;100:1306–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Friel LA, Romero R, Edwin S, et al. The calcium binding protein, S100B, is increased in the amniotic fluid of women with intra-amniotic infection/inflammation and preterm labor with intact or ruptured membranes. J Perinat Med. 2007;35:385–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Gomez-Lopez N, Romero R, Arenas-Hernandez M, et al. In vivo T-cell activation by a monoclonal αCD3ε antibody induces preterm labor and birth. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2016;76:386–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].St Louis D, Romero R, Plazyo O, et al. Invariant NKT Cell Activation Induces Late Preterm Birth That Is Attenuated by Rosiglitazone. J Immunol. 2016;196:1044–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Arenas-Hernandez M, Romero R, Xu Y, et al. Effector and Activated T Cells Induce Preterm Labor and Birth That Is Prevented by Treatment with Progesterone. J Immunol. 2019;202:2585–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Gomez-Lopez N, Arenas-Hernandez M, Romero R, et al. Regulatory T Cells Play a Role in a Subset of Idiopathic Preterm Labor/Birth and Adverse Neonatal Outcomes. Cell Rep. 2020;32:107874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Galaz J, Romero R, Arenas-Hernandez M, et al. A Protocol for Evaluating Vital Signs and Maternal-Fetal Parameters Using High-Resolution Ultrasound in Pregnant Mice. STAR Protoc. 2020;1:100134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Faro J, Romero R, Schwenkel G, et al. Intra-amniotic inflammation induces preterm birth by activating the NLRP3 inflammasome. Biol Reprod. 2019;100:1290–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat Methods. 2012;9:671–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Arenas-Hernandez M, Sanchez-Rodriguez EN, Mial TN, Robertson SA, Gomez-Lopez N. Isolation of Leukocytes from the Murine Tissues at the Maternal-Fetal Interface. J Vis Exp. 2015:e52866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Patro R, Duggal G, Love MI, Irizarry RA, Kingsford C. Salmon provides fast and bias-aware quantification of transcript expression. Nat Methods. 2017;14:417–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014;15:550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Gentleman RC, Carey VJ, Bates DM, et al. Bioconductor: open software development for computational biology and bioinformatics. Genome Biol. 2004;5:R80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Draghici S, Khatri P, Tarca AL, et al. A systems biology approach for pathway level analysis. Genome Res. 2007;17:1537–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Khatri P, Draghici S, Tarca AL, Hassan SS, Romero R. A system biology approach for the steady-state analysis of gene signaling networks. In: Rueda L, Mery D, Kittler J, editors. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Berlin: Springer; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- [59].Tarca AL, Draghici S, Khatri P, et al. A novel signaling pathway impact analysis. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:75–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Altman M, Vanpee M, Cnattingius S, Norman M. Neonatal morbidity in moderately preterm infants: a Swedish national population-based study. J Pediatr. 2011;158:239–44 e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Blencowe H, Cousens S, Chou D, et al. Born too soon: the global epidemiology of 15 million preterm births. Reprod Health. 2013;10 Suppl 1:S2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Allotey J, Zamora J, Cheong-See F, et al. Cognitive, motor, behavioural and academic performances of children born preterm: a meta-analysis and systematic review involving 64 061 children. BJOG. 2018;125:16–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Bui DS, Perret JL, Walters EH, et al. Association between very to moderate preterm births, lung function deficits, and COPD at age 53 years: analysis of a prospective cohort study. Lancet Respir Med. 2022;10:478–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Gomez-Lopez N, Romero R, Tarca AL, et al. Gasdermin D: Evidence of pyroptosis in spontaneous preterm labor with sterile intra-amniotic inflammation or intra-amniotic infection. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2019;82:e13184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Bhatti G, Romero R, Rice GE, et al. Compartmentalized profiling of amniotic fluid cytokines in women with preterm labor. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0227881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Motomura K, Romero R, Galaz J, et al. RNA Sequencing Reveals Distinct Immune Responses in the Chorioamniotic Membranes of Women with Preterm Labor and Microbial or Sterile Intra-amniotic Inflammation. Infect Immun. 2021;89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]