Abstract

Objective:

Research suggests that the 2016 U.S. election was a potential stressor among Latinos residing in the U.S. Sociopolitical stressors targeted toward ethnic minority communities and become embodied through psychosocial distress. The current study investigates if and how sociopolitical stressors related to the 45th President, Donald Trump, and his administration are associated with psychological distress in early pregnancy of Latina women living in Southern California during the second half of his term.

Methods:

This cross-sectional analysis uses data from the Mothers’ Cultural Experiences study (n=90) collected from December 2018 to March 2020. Psychological distress was assessed in three domains: depression, state anxiety, and pregnancy-related anxiety. Sociopolitical stressors were measured through questionnaires about sociopolitical feelings and concerns. Multiple linear regression models examined the relationship between sociopolitical stressors and mental health scores, adjusting for multiple testing.

Results:

Negative feelings and a greater number of sociopolitical concerns were associated with elevated pregnancy-related anxiety and depressive symptoms. The most frequently endorsed concern was about issues of racism (72.3%) and women’s rights (62.4%); women endorsing these particular concerns also had higher scores on depression and pregnancy-related anxiety. No significant associations were detected with state anxiety after correction for multiple testing.

Limitations:

This analysis is cross-sectional and cannot assess causality in the associations between sociopolitical stressors and distress.

Conclusions:

These results are consistent with the hypothesis that the 2016 election, the subsequent political environment, and the anti-immigrant rhetoric and policies of former President Trump and his administration were sources of stress for Latinos residing in the U.S.

Keywords: Sociopolitical stressors, psychological distress, depression, Latina health disparities, pregnancy-related anxiety, Trump administration

Introduction:

Fears and concerns related to Donald Trump’s presidency and his administration’s policies may have negatively impacted health and well-being among the U.S. Latino population. Latino immigrant communities residing in the U.S. have reported increased fear of deportation and family separation in the wake of the 2016 election, resulting in delays in utilization of healthcare services (Cervantes and Menjívar, 2020; Fleming et al., 2019). Anti-immigrant policies that increase deportation fears amongst Latino immigrants contribute to widening Latino health disparities through emotional distress (Dreby, 2015; Eskenazi et al., 2019; Nichols et al., 2018) and adverse physical health outcomes (Martínez et al., 2017; Torres et al., 2019). Furthermore, the 2016 election may have also contributed to adverse birth outcomes of Latina women (Gemmill et al., 2020; Gemmill et al., 2019). While concerns about immigration policies are particularly salient for Latino communities, this population was also targeted by other political threats, such as loss of access to health care and social services (Callaghan et al., 2019; Rodriguez et al., 2019). Our study investigates associations between sociopolitical concerns related to the 45th U.S. president, Donald Trump, and his administration, and psychological distress in a cohort of pregnant Latina women living in Southern California from December 2018 to March 2020, roughly two years into the Trump presidency.

There is growing recognition of the contributions of sociopolitical stressors to psychological well-being and minority mental health disparities in the U.S. Ecosocial theory posits that these macrosocial factors of social ecology impact health through processes of embodiment to produce population-level patterns of health disparities (Krieger, 2001). Recent theorization that situates politics within the realm of affective psychological science suggests that day-to-day politics may become embodied by viewing politics as a form of chronic stress that impacts individuals’ psychological health (Ford and Feinberg, 2020). Such stressors can be defined as threatening rhetoric or political legislation targeting specific sociodemographic groups, which may affect the psychological well-being of minoritized communities (Krieger et al., 2018). The Minority Stress Model posits that minoritized social groups are disproportionately and uniquely exposed to such stressors and related stress due to their identity (Meyer, 1995). While originally developed to explain disproportionate burdens of psychological distress among sexual minority individuals, this model has been expanded to explain multiple intersecting identity-related chronic stressors, such as discrimination, sexism, and nativism, for other populations, including Latino immigrant populations (Valentín-Cortés et al., 2020). These perspectives inform our hypothesis that the Trump presidency and administration may have uniquely impacted the psychological well-being of pregnant Latinas.

Donald Trump’s election and presidency can be considered a sociopolitical stressor due to the use of racialized and nationalist rhetoric during President Trump’s campaign, as well as the subsequent implementation of anti-immigrant policies that targeted minoritized communities (Waldinger, 2018; Winders, 2016). Rises in discrimination and hate crimes against minority groups has also been linked to the 2016 primaries and election (Edwards and Rushin, 2018; Feinberg et al., 2019). The Pew Research Center reported that in 2018 a majority of persons of Hispanic ethnicity (54%) said that it had become more difficult to be Hispanic in the U.S. and 38% reported experiencing at least one type of discrimination within the past year, in both 2018 and 2019 (Gonzalez-Barrera and Lopez, 2020; Lopez et al., 2018). These stressors may exacerbate existing mental health disparities in the US by increasing fear and psychological distress of minoritized groups targeted by these events and rhetoric (Williams and Medlock, 2017). Severe sociopolitical stressors targeting minoritized communities, including those exacerbated after the 2016 election, have been shown to detrimentally impact the health and well-being of Latino, Muslim, and immigrant populations in the U.S. (Bakhtiari, 2020; Hatzenbuehler et al., 2017; Philbin et al., 2018; Torche and Sirois, 2019; Young et al., 2020). The election had specific health impacts on Latino populations given the intensity with which this community was targeted by Trump (Morey, 2018; Nichols et al., 2018). Such stressors may widen mental health inequalities in the US and impact vulnerable individuals, such as pregnant Latina women.

Pregnancy is a particularly sensitive life stage in which sociopolitical stressors may contribute to patterns of mental health disparities through embodiment, and intergenerationally through processes of biological embedding (Conradt et al., 2020; Fox et al., 2015). A number of epidemiological studies have demonstrated associations between the 2016 presidential election and adverse birth outcomes, such as preterm birth and small for gestational age, which have been shown elsewhere to be sensitive to acute psychosocial stressors (Gemmill et al., 2020; Gemmill et al., 2019; Krieger et al., 2018). Krieger et al. (2018) reported increased preterm birth rates among foreign-born Latinas living in New York after the election, with no increases for other demographic groups. Using data from all U.S. births from 2009–2017, Gemmill et al. (Gemmill et al., 2020; 2019) observed greater increases in preterm and periviable birth rates among Latinas than predicted by pre-election trends and found no similar associations for other groups. While such analyses of large datasets reveal population level trends, they are unable to elucidate potential mechanisms.

Our study

The objective of our study was to examine associations between sociopolitical concerns and maternal psychological distress between 8–16 weeks of gestation amongst a cohort of Latina women living in Southern California enrolled in the Mothers’ Cultural Experiences (MCE) study. This population was targeted by Trump administration policies ranging from immigration policy threats to loss of access to social services. Informed by ecosocial theory, the minority stress model, and political determinants perspectives, we test the hypothesis that sociopolitical stressors related to Trump and his presidency are associated with symptoms of psychological distress in pregnancy and seek to address three research questions (RQ):

Are feelings about Trump, his presidency, and administration’s policies related to psychological distress?

Is having more political concerns associated with greater psychological distress?

Which specific sociopolitical concerns are more strongly associated with psychological distress?

This analysis builds upon our previous work conducted with the MCE study. In a cross-sectional survey of pregnant and early postpartum Latina women living in Southern California from January 2017 – May 2018, we observed that participants who endorsed 2016 election-related concerns about former President Trump’s attitudes toward women and women’s rights reported higher levels of state anxiety (Fox, 2022). Here we follow up with an investigation of Latina women’s sociopolitical concerns and psychological distress between December 2018 and March 2020, focusing on early pregnancy as this is a potentially sensitive window during which maternal distress affects fetal development (Ghimire et al., 2021). We did not have any a priori hypotheses about the three predictors and tested the three research questions independently.

Our study builds on the extant literature by examining sociopolitical concerns beginning one year and 11 months into the Trump administration. We extend the previous literature to include multiple domains of political concerns and participants’ self-reported feelings. We expand upon previous studies that compare outcomes from large datasets before and after a political event and examines self-reported distress at the individual level. This research contributes to a growing literature on the contributions of politics and political rhetoric in exacerbating health disparities experienced by minoritized communities in the United States.

Methods:

Cohort

Data used in this analysis are derived from Wave 2 of the MCE study, an ongoing longitudinal cohort study examining how social and cultural stressors relate to maternal-infant health and developmental among Latinas living in Southern California. Participation in the MCE study was limited to women who self-identify as Latina, Hispanic, Chicana, Mexicana, and/or Latin American. Wave 2 women were recruited in early pregnancy, beginning in December 2018. Data used in this analysis are derived from the first timepoint (T1, 8–19 weeks’ gestation, average 12 weeks). T1 data were collected from December 2018–March 2020. Potential participants were approached in clinic waiting rooms at recruitment sites. Written, informed consent was obtained after a description of the study procedures. Questionnaires were administered in English or Spanish depending on the participant’s preference. This study was approved at the Institutional Review Boards of all participating institutions and adheres to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Psychological distress

Depressive symptoms were assessed using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS). The EPDS is a 10-item self-report measure of postnatal depressive symptoms, and is scored as a sum after reverse coding seven items (Cox et al., 1987). Higher scores indicate greater depression. We removed the 10th item about self-harm due to ethical concerns and the score used in this analysis is based on the other nine items. The scale has been validated for use with pregnant women to detect depressive symptoms in the antepartum period (Alvarado-Esquivel et al., 2006; Cox et al., 1996). Cronbach’s alpha was 0.85 (Spanish = 0.78; English = 0.85).

Anxiety symptoms were in two domains: state anxiety was assessed using the short form version of the State form of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) (Spielberger, 1983) and pregnancy-related anxiety (PRA) was quantified by the Pregnancy-Related Anxiety Scale (Wadhwa et al., 1993). The STAI short form is a six-item measure developed and validated for use with pregnant women (Marteau and Bekker, 1992; Tluczek et al., 2009). The score is calculated by computing the mean after reverse scoring three items. The validation study reported that prorated scores were comparable to the full version of the scale (Marteau and Bekker, 1992). The PRA scale is a 10-item scale on worries over pregnancy and fetal development. A score is calculated by computing the mean of items after reverse scoring two items. Cronbach’s alpha for STAI and PRA were 0.69 (Spanish = 0.51; English = 0.76) and 0.83 (Spanish = 0.82; English = 0.88), respectively. The lower alphas among Spanish speaking participants may be due to problems with translations or perhaps distinct cross-cultural ideas of state anxiety.

Sociopolitical stressors and concerns

Sociopolitical stressors and concerns were assessed using two original questionnaires to assess participants’ feelings and specific concerns related to the Trump presidency (Tables S1-S2). The Political Feelings Questionnaire is a seven-item questionnaire designed to capture participants’ feelings about Trump as president, modeled after the STAI. The prompt “How do you feel now about Trump as president of the U.S?” was presented and participants were asked to respond to the following feelings on a Likert scale: afraid, worried, happy, stressed, hopeful, supportive, and angry. The response scale ranged from (1) not at all to (4) very much. Positive items were reverse scored such that a higher score on the scale indicated more negative feelings about Trump as president. A summary score was calculated by averaging the response to each question. We conducted a confirmatory factor analysis to assess the latent structure of this questionnaire. We first imposed a unidimensional factor structure in which all items were contained within a single factor. We then constructed a second-order model in which the responses were separated into positive and negative factors. Results suggest that a two-factor structure of negative and positive feelings best represented the latent structure of the questionnaire data (Tables S3-S4). The overall Cronbach’s alpha for the questionnaire was 0.82, (Spanish=0.82; English=0.71), suggesting good internal consistency of the items. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.89 (Spanish=0.90; English=0.96) for the positive subscale and 0.92 (Spanish=0.90; English=0.90) for the negative subscale.

The Sociopolitical Concerns Questionnaire (Table S2) consisted of a checklist of eight items, as well as space for participants to write in other concerns, and was prefaced with the prompt: “What are your personal fears or concerns about Trump as president of the U.S.?”, followed by the instructions “These questions are about your feelings and opinions. There are no right or wrong answers.” Concerns were related to immigration, such as the participant’s own risk of deportation, or the risk for their children, family or friends, potential loss of access to social services such as WIC, and other sociopolitical issues related to Trump’s attitudes towards women’s rights and possible corruption. For responses to the “other” option, the research team recoded any overlapping responses with the original questionnaire items as though the participant had endorsed that item. Three participants wrote in responses and all three responses fell under existing concern options. A total number of concerns was calculated.

Statistical analyses

Analyses of the Political Feelings Questionnaire were conducted on the positive and negative subscale scores. Each item of the Sociopolitical Concerns Questionnaire was analyzed individually as dichotomous variables with individuals who did not endorse that specific concern coded as the reference group. We also ran multivariable regression models for individuals who did not endorse any concerns with participants who endorsed one or more specific concern as the reference group.

Covariates included socioeconomic status (SES), nativity, parity, and maternal age. SES was calculated using a composite based on food insecurity and education. Using the clusterSim R package, each variable was normalized by unitization with zero minimum such that values closer to two reflected higher SES (Walesiak and Dudek, 2020), and scores were then averaged across the two items. Household income was not included in SES calculations as many participants could not reliably estimate the income of other members of their household. Place of birth was recoded to reflect U.S.-born or born outside of the U.S. Participants reported number of children and were coded as nulliparous or parous.

All analyses were conducted using the R(Version 1.3.1093) statistical programming language and environment. For RQ1 and RQ2, we used multivariable regression to examine associations between sociopolitical feelings, total number of sociopolitical concerns, and mental health scores, controlling for the demographic covariates. In order to investigate associations with specific sociopolitical concerns (RQ3), we ran a series of 9 multivariable linear regression models to examine how each sociopolitical concern was associated with scores on each of the mental health measures. The variable for each specific concern was coded such that individuals who did not endorse that concern were the reference group. Regression model p-values were corrected for multiple testing using the Benjamini-Hochberg (B-H) procedure to adjust for false discovery rate at 0.05.

Results

Prior to analysis, N=17 participants were excluded due to missing sociopolitical concerns or demographic data. In total, complete data were available for n=90 participants. Demographic characteristics of the study participants are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics

| n=90 | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Age, M (SD) | 32.42 (5.82) |

| Parity, N (%) | |

| Nulliparous | 32 (35.6%) |

| Parous | 58 (64.4%) |

| Place of Birth, N (%) | |

| U.S. | 45 (50%) |

| Other | 45 (50%) |

| Education, N (%) | |

| Less than high school | 15 (16.6%) |

| High school | 45 (50.0%) |

| Technical or Associates | 16 (17.8%) |

| College degree and higher | 14 (15.6%) |

| Food Security, N (%) | |

| Secure | 63 (70%) |

| Insecure | 27 (30%) |

| Discrimination, M (SD) | 1.60 (0.66) |

| Psychological Distress, M (SD) | |

| Depression score | 5.86 (5.08) |

| State anxiety score | 1.77 (0.53) |

| Pregnancy anxiety score | 1.70 (0.55) |

| In your opinion, is Trump’s presidency good for the U.S.?, N (%): | |

| No | 63 (70%) |

| Yes | 4 (4.4%) |

| Not good or bad | 23 (25.6%) |

| In your opinion, is Trump’s presidency good for you and your family?, N (%) | |

| No | 57 (63.3%) |

| Yes | 4 (4.5%) |

| Not good or bad | 30 (33.2) |

Depression was assessed with the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression scale (EPDS), with possible scores ranging from 0–27. State anxiety was assessed with the State form of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory – Short Form (STAI-SF) with possible scores ranging from 1–4. Pregnancy anxiety was assessed with the Pregnancy-related anxiety scale with possible scores ranging from 1–4. Discrimination was measured using the Everyday Discrimination scale, preceded by the instructions “Because of your ethnicity/race, how often …”, with a possible range of scores of 1–4.

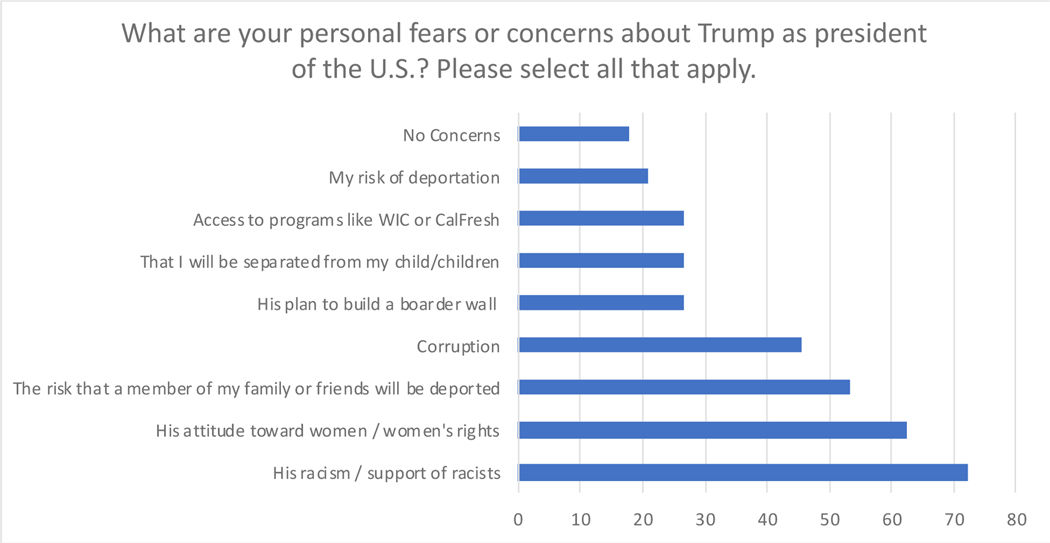

The frequencies of endorsed sociopolitical concerns are presented in Figure 1. Eighty-two percent of the sample endorsed at least one sociopolitical concern. The most frequently endorsed concern was “his racism or support of racists” with 72% of the sample noting this concern.

Figure 1. Frequencies of Endorsed Sociopolitical Concerns.

RQ1: Feelings about Trump as president and psychological distress

We first tested if positive and negative feelings about Trump as president were associated with psychological distress using multivariable regression to adjust demographic covariates, including SES, nativity, parity, and maternal age. Positive feelings were not related to scores on any of the distress measures (p-values>0.05, Table 2).

Table 2.

RQ1: Multivariable regression of sociopolitical feelings and mental health adjusting for demographic covariates

| Negative Feelings |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β (SE) | p | Adj Model R2 | Model p | B-H Adj p-value | |

|

|

|||||

| Depression | 1.180 (0.51) | 0.023* | 0.138 | 0.003** | 0.027+ |

| State anxiety | 0.131 (0.06) | 0.025* | 0.016 | 0.274 | 0.379 |

| Pregnancy anxiety | 0.123 (0.06) | 0.034* | 0.094 | 0.020* | 0.065 |

|

|

|||||

| Positive Feelings | |||||

|

|

|||||

| β (SE) | p | Adj Model R2 | Model p | B-H Adj p-value | |

|

|

|||||

| Depression | 0.382 (0.70) | 0.585 | 0.085 | 0.028* | 0.078 |

| State anxiety | 0.003 (0.08) | 0.966 | 0.041 | 0.916 | 0.943 |

| Pregnancy anxiety | −0.036 (0.08) | 0.64 | 0.065 | 0.058 | 0.103 |

P-value < 0.05,

p-value < 0.01,

p-value < 0.001

Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted p-value < 0.05

We then tested for associations with negative feelings about Trump as president and detected statistically significant associations between negative feelings and EPDS (β=1.18, p-value=0.02, Adj. R2=0.14), STAI (β=0.13, p-value=0.03, Adj. R2=0.02) and PRA (β=0.12, p-value=0.03, Adj. R2=0.09) scores, after adjusting for the demographic covariates (Table 2). However, only the associations with EPDS scores survived correction for multiple testing (q-values>0.05).

RQ2: Total concerns and psychological distress

We then examined whether having a greater number of concerns about Trump as president were associated with scores on the psychological distress measures using multivariable linear regressions to control for demographic covariates (Table 3). The total number of political concerns remained significantly associated with EPDS (β=0.51, p-value=0.03, Adj. R2=0.10) and PRA (β=0.06, p-value=0.03, Adj. R2=0.10) scores, but did not survive correction for multiple testing (q-value≥0.05).

Table 3.

RQ2: Multivariable Regression of Total Sociopolitical Concerns and Mental Health

| Multivariable Regression | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β (SE) | p | Adj Model R2 | Model P | B-H Adj p-value | |

|

|

|||||

| Depression | 0.506 (0.23) | 0.033* | 0.103 | 0.011* | 0.050 |

| State anxiety | 0.032 (0.03) | 0.240 | 0.026 | 0.076 | 0.109 |

| Pregnancy anxiety | 0.056 (0.03) | 0.025* | 0.102 | 0.011* | 0.050 |

P-value < 0.05,

p-value < 0.01,

p-value < 0.001

Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted p-value < 0.05

Each row represents one multivariable regression model adjusting for demographic covariates for each of the mental health measures as an outcome. Details of each regression model are presented in Table S7.

RQ3: Associations with specific concerns

We performed a multivariable linear regression for each of the specific sociopolitical concerns, adjusting for demographic concerns. This resulted in nine regressions for each of three psychological distress measures. We compared scores on each of the psychological distress measures for participants who endorsed the specific concern with those who did not endorse that concern as the reference group (Table 4). For example, scores on the EPDS were compared for those who were concerned with their risk of deportation relative to those who did not endorse that specific concern.

Table 4.

RQ3: Multivariable regression for associations between specific sociopolitical concerns and psychological distress

| Depression | State anxiety | Pregnancy anxiety | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||||

| β (SE) | p | Adj Model R2 | Model P | B-H Adj p-value | β (SE) | p | Adj Model R2 | Model P | B-H Adj p-value | Β (SE) | p | Adj Model R2 | Model P | B-H Adj p-value | |

|

|

|||||||||||||||

| None | −2.956 (1.50) | 0.053 | 0.095 | 0.015* | 0.054 | −0.353 (0.17) | 0.035* | 0.008 | 0.334 | 0.445 | −0.331 (0.16) | 0.046* | 0.095 | 0.014* | 0.054 |

| Access to programs like WIC or CalFresh | 1.254 (1.13) | 0.270 | 0.069 | 0.041* | 0.098 | 0.091 (0.13) | 0.470 | 0.036 | 0.884 | 0.943 | 0.155 (.12) | 0.209 | 0.071 | 0.039* | 0.098 |

| My risk of deportation | 0.500 (1.38) | 0.717 | 0.058 | 0.063 | 0.103 | −0.018 (0.15) | 0.906 | 0.042 | 0.943 | 0.943 | 0.107 (0.15) | 0.474 | 0.060 | 0.059 | 0.103 |

| That I will be separated from my child/children | 1.445 (1.47) | 0.327 | 0.067 | 0.045* | 0.101 | −0.048 (0.16) | 0.771 | 0.041 | 0.936 | 0.943 | 0.053 (0.16) | 0.740 | 0.055 | 0.069 | 0.104 |

| The risk that a member of my family or friends will be deported | 0.164 (1.05) | 0.876 | 0.057 | 0.066 | 0.103 | 0.042 (0.12) | 0.716 | 0.040 | 0.931 | 0.943 | −0.110 (0.11) | 0.335 | 0.064 | 0.050 | 0.103 |

| His plan to build a boarder wall | 0.769 (1.13) | 0.499 | 0.061 | 0.055 | 0.103 | −0.026 (0.13) | 0.835 | 0.041 | 0.940 | 0.943 | 0.077 (0.12) | 0.535 | 0.058 | 0.062 | 0.103 |

| His racism / support of racists | 3.303 (1.06) | 0.002** | 0.148 | 0.001*** | 0.018+ | 0.157 (0.12) | 0.206 | 0.023 | 0.725 | 0.870 | 0.332 (0.12) | 0.005** | 0.132 | 0.003** | 0.027+ |

| His attitude toward women / women’s rights | 2.378 (1.01) | 0.021* | 0.110 | 0.008** | 0.048+ | 0.202 (0.11) | 0.081 | 0.007 | 0.506 | 0.628 | 0.343 (0.11) | 0.002** | 0.149 | 0.001*** | 0.018+ |

| Corruption | 1.552 (1.03) | 0.136 | 0.080 | 0.027* | 0.078 | 0.206 (0.11) | 0.074 | 0.005 | 0.483 | 0.621 | 0.289 (0.11) | 0.010* | 0.122 | 0.005** | 0.036+ |

P-value < 0.05,

p-value < 0.01,

p-value < 0.001

Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted p-value < 0.05

Associations with depression scores

Scores on the EPDS (Table 4) were significantly associated with the concerns related to racism (β=3.03, p-value=0.002, Adj. R2=0.15) and women’s rights (β=2.38, p-value=0.02, Adj. R2=0.11), both of which survived correction for multiple testing (q-value<0.05).

Associations with state anxiety scores

Participants who did not endorse any sociopolitical concerns had lower STAI scores (β=0.04, p-value=0.04, Adj. R2=0.01, Table 4). However, this association did not survive correction for multiple testing (q-value>0.05). None of the specific concerns were significantly associated with STAI scores (p-values>0.05).

Associations with pregnancy anxiety scores

Scores on the PRA (Table 4) were also significantly associated with concerns about racism (β=0.33, p-value=0.05, Adj. R2=0.13), women’s rights (β=0.34, p-value=0.002, Adj. R2=0.15) and also with corruption (β=0.29, p-value=0.01, Adj. R2=0.12), and all three survived correction for multiple testing. Furthermore, participants who did not endorse any specific concerns had lower PRA scores (β=−0.33, p-value=0.046, Adj. R2=0.09) relative to those who endorsed one or more concerns, however this association did not persist after correction for multiple testing (q-value>0.05.

None of the immigration-related concerns were statistically significantly associated with any of the psychological distress variables.

Discussion

The current study examined associations between sociopolitical concerns related to the 45th U.S. president and his rhetoric, behavior, and administration’s policies. Overall, our findings support the hypothesis that macrosocial political factors become embodied through individual-level psychological processes (psychological distress). In a cohort of Latina women living in Southern California, we found that individuals who reported experiencing negative feelings, such as worry and fear, related to the Trump administration had higher scores on depressive and pregnancy-related anxiety symptoms at 8–16 weeks of pregnancy, although these associations did not survive correction for multiple testing (RQ1). Women who reported greater numbers of sociopolitical concerns (RQ2), as well as concerns about racism, women’s rights, and corruption (RQ3) also had higher scores on depression and pregnancy-related anxiety questionnaires. These results are consistent with the hypothesis that the political environment and the anti-immigrant rhetoric and policies of former President Trump and his administration were sources of chronic stress for this population. We extend the existing literature by investigating associations between these stressors and psychological distress beginning one year and 11 months into the Trump presidency. Our study builds on our group’s previous work examining the same sociopolitical concerns specifically related to the 2016 election and mental health using data collected from January 2017 – May 2018 (Fox, 2022).

Politics and health

The 2016 election and the subsequent political climate were, and continue to be, sources of stress for many adults in the U.S. (American Psychological Association, 2017). Several studies conducted after the election reported increases in rates of preterm and previable births among Latina women and hospitalizations due to acute cardiovascular disease in the general population that, speculatively, may be attributable to sociopolitical stress surrounding the 2016 election (Gemmill et al., 2020; Gemmill et al., 2019; Mefford et al., 2020) Studies conducted with Latino young adults also suggest that the election was associated with negative affect and elevation of cortisol (Hoyt et al., 2018; Zeiders et al., 2020). We found that sociopolitical concerns were sustained well into the Trump administration and were not isolated to the immediate post-election period. Our interviews were conducted from December 2018 to March 2020, beginning one year and 11 months into the Trump administration. These concerns mirror those of a cross-sectional survey of pregnant and early postpartum Latina women conducted by our team from January 2017 – May 2018 which found that the most frequently endorsed election-related concerns were similar- 69% were concerned about racism and 62% were concerned about women’s rights (Fox, 2022).

We found that both the total number of concerns and specific sociopolitical concerns related to racism and women’s rights were associated with symptoms of depression and pregnancy-related anxiety well into the Trump administration. This is broadly in line with the ecosocial theory and supports the notion that the political climate is a macrosocial stressor that influences patterns of health and well-being, particularly for minoritized communities (Krieger et al., 2018). The Minority Stress Model provides insight into why studies find, among white or otherwise majority-identity populations, immediate negative emotional responses following political events, such as presidential elections, yet do not find long-term changes in well-being (Roche and Jacobson, 2019; Simchon et al., 2020). Such long-term effects on well-being may only be observed for populations disproportionately experiencing minority identity-related stressors that are exacerbated by political rhetoric and harmful policies (Valentín-Cortés et al., 2020). Our results are broadly in line with the hypothesis that minoritized groups may have been uniquely impacted by chronic sociopolitical stress in the wake of the 2016 election and subsequent political climates and policy decisions. Political concerns may manifest in psychological distress in these populations as responses to targeted hurtful political rhetoric (Chavez et al., 2019).

Specific sociopolitical concerns

We found that participants who endorsed concerns about racism and women’s rights were more likely to have high symptom burdens of depression and pregnancy-related anxiety. Our results suggest patterns of specific sociopolitical concerns are multifaceted and may reflect multiple domains of minoritized-identity status, such as race and gender. The associations between racism and psychological distress are likely explained by rising rates of hate crimes and discrimination in this period. Previous studies have shown that both Latino U.S. citizens and foreign-born Latinos with citizenship or residency documents were increasingly questioned about belonging in the U.S. (Fleming et al., 2019) and experienced discrimination and racism (Findling et al., 2019). Experiences of racial discrimination are robustly associated with adverse physical and mental health outcomes (Pascoe and Smart Richman, 2009). Latinas are vulnerable to multiple and intersecting forms of identity-related discrimination, such as racism, sexism and xenophobia that may compound the impacts of discrimination on their health (Rosenthal and Lobel, 2020; Velez et al., 2015). Pregnant women may also experience pregnancy-related discrimination that may detrimentally impact their psychological well-being (Hackney et al., 2021).

The high percentage of participants who endorsed concerns about women’s rights (62.4%) likely reflects the numerous and frequent policy initiatives targeting women’s health. The Trump administration health policy efforts sought to roll back women’s health efforts, including access to abortion, contraception, and maternity care (Brindis et al., 2017; Grossman, 2017). Such policies may exacerbate existing health care access inequalities as Latina women historically face myriad political, economic, and social barriers to health care (Alcalá et al., 2016). Concerns about access to prenatal care are particularly salient as disruptions of prenatal care are associated with elevated psychological distress in pregnancy (Groulx et al., 2021).

Notably, when analyzing associations for specific sociopolitical concerns, we did not find any associations for the immigration-related items. This is one of few studies to ask both U.S.-born and foreign-born participants about their perceived immigration policy concerns. Another study conducted with pregnant immigrant Latinas living in North Carolina found that deportation fears were associated with prenatal state and trait anxiety, but not depression (Lara-Cinisomo et al., 2019). Our participants Concerns about the risk of family separation are contextualized by the revelations regarding the Trump administration’s family separation policies at this time. Reports of family separation first emerged in late 2017 and dominated the national discourse by summer 2018 (Southern Poverty Law Center, 2020). Expectant mothers may feel particularly threatened by such policies. While we did not ask about documentation status due to ethical concerns, it is possible that concerns about deportation risk varied by citizenship or residency status.

The relatively low percentage of participants endorsing fears about their own risk of deportation may reflect how Los Angeles declared itself a sanctuary city in early 2019 (Smith and Ormseth, 2019). Our findings are in line with a recent study among Latino adolescents living in California, of whom half reported at least some worries about the effect of U.S. immigration policy on themselves and their families (Eskenazi et al., 2019). Previous studies have shown that being born in the U.S. does not necessarily buffer Latino communities from fears about immigration policy vulnerability (Asad, 2020; Fleming et al., 2019).

Concerns about corruption were positively associated with symptoms of pregnancy-related anxiety. The literature on associations between government corruption and mental health is small. Corruption, measured as exposure at the individual- and national-level, has been associated with adverse mental health outcomes in high- and low-income countries (Achim et al., 2020; Gillanders, 2016; Sharma et al., 2021; van Deurzen, 2017). It is unclear why such concerns manifest in pregnancy-related anxiety in this population but it may be that participants are worried about corruption resulting in restricted access to healthcare. Future studies should investigate in more detail what acts women viewed as corruption in the Trump administration.

Strengths and limitations

This is one of only a few studies that has interviewed pregnant Latina women on their specific sociopolitical concerns. Many studies have focused on immigration-related concerns and our questionnaire was designed to assess multiple domains of sociopolitical concerns. Furthermore, there was an option for participants to write in sociopolitical concerns that were not included in the provided list. We also assessed multiple domains of psychological distress. Psychological distress encompasses symptoms from multiple domains of mental health that tend to covary together. This warrants investigation of multiple specific domains that may be differentially impacted by sociopolitical stressors.

The results of this study should be considered in light of several limitations. This analysis was cross-sectional and we are unable to assess changing sociopolitical concerns over time. While our results support our hypothesis, we cannot rule out the alternative causal pattern such that having more severe distress symptoms causes women to have more sociopolitical concerns. We did not ask about citizenship or immigration status. While documented and undocumented populations report psychological distress due to immigration concerns, the association is stronger for undocumented immigrants (Hacker et al., 2012). The Spanish version of the STAI exhibited somewhat poor reliability in our sample. This lack of reliability may account for our unexpected non-significant STAI findings. Finally, our sample is limited to Latina women, predominantly of Mexican heritage living in Southern California. This limits our ability to generalize our findings to Latina populations living in other regions of the U.S. or those with heritage from other countries. Future studies are needed to investigate these associations in other areas and with more diverse cohorts and better assess the validity of measures of sociopolitical concerns and feelings.

Conclusion

We found that sociopolitical concerns and feelings about Trump and his administration were related to symptoms of psychological distress in early pregnancy in a cohort of Latina women in Southern California. The results of this study contribute to the growing body of evidence suggesting that sociopolitical stressors targeting minoritized communities become embodied in adverse mental health outcomes. These findings highlight the need for policy interventions that can improve the well-being of Latina communities. Future research should investigate other sociopolitical policies that target minoritized populations, such as anti-immigration policies, contraception and abortion restriction, bans on gender-affirming health care for transgender populations, and marriage equality in the U.S. and other contexts.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors deeply thank the study participants and their families as well as the students and volunteers of the MCE study. The authors also thank the health clinics and staff that made this research possible including Kajokaite, Maridet Ibanez and the team at Women’s Infants and Children in Santa Ana CA, Celia Bernstein and the team at Westside Family Health Center, Lirona Katzir and the team at Olive View-UCLA Medical Center, and Yvette Bojorquez and the team at MOMS Orange County. The authors thank colleagues and collaborators that provided helpful feedback on this study, including Patricia Greenfield, Gail Greendale, Rachel Brook, Janet P. Pregler, Laura M. Glynn, Curt A. Sandman, and Chris Dunkel Schetter. This study was funded by NIH National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases K01 DK105110 and R03 DK125524 to M.F., F32 MD015201 to K.S.W., and UCLA Center for the Study of Women Faculty Research Grant to M.F.

Funding Statement:

This study was funded by NIH National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases K01 DK105110 and R03 DK125524 to M.F., F32 MD015201 to K.S.W., and UCLA Center for the Study of Women Faculty Research Grant to M.F.

Footnotes

Ethics Approval Statement: This study was reviewed and received approval from the University of California, Los Angeles Institutional Review Board.

Patient Consent Statement: All participants provided written informed consent for participation in this study.

Conflict of Interest Disclosure: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Data Availability Statement:

Data are available from the corresponding or senior author upon reasonable request.

References:

- Achim MV, Văidean VL, Borlea SN, 2020. Corruption and health outcomes within an economic and cultural framework. The European Journal of Health Economics 21, 195–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alcalá HE, Albert SL, Trabanino SK, Garcia RE, Glik DC, Prelip ML, Ortega AN, 2016. Access to and Use of Health Care Services Among Latinos in East Los Angeles and Boyle Heights. Family & community health 39, 62–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarado-Esquivel C, Sifuentes-Alvarez A, Salas-Martinez C, Martínez-García S, 2006. Validation of the Edinburgh postpartum depression scale in a population of puerperal women in Mexico. Clinical Practice and Epidemiology in Mental Health 2, 33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association, 2017. Stress in America: Coping with change, Part 1. Stress in America™ Survey.

- Asad AL, 2020. Latinos’ deportation fears by citizenship and legal status, 2007 to 2018. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117, 8836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakhtiari E, 2020. Health effects of Muslim racialization: Evidence from birth outcomes in California before and after September 11, 2001. SSM - population health 12, 100703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brindis CD, Freund KM, Baecher-Lind L, Bairey Merz CN, Carnes M, Gulati M, Joffe H, Klein WS, Mazure CM, Pace LE, Regensteiner JG, Redberg RF, Wenger NK, Younger L, 2017. The Risk of Remaining Silent: Addressing the Current Threats to Women’s Health. Women’s health issues : official publication of the Jacobs Institute of Women’s Health 27, 621–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callaghan T, Washburn DJ, Nimmons K, Duchicela D, Gurram A, Burdine J, 2019. Immigrant health access in Texas: policy, rhetoric, and fear in the Trump era. BMC Health Services Research 19, 342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervantes AG, Menjívar C, 2020. Legal Violence, Health, and Access to Care: Latina Immigrants in Rural and Urban Kansas. J Health Soc Behav 61, 307–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavez LR, Campos B, Corona K, Sanchez D, Ruiz CB, 2019. Words hurt: Political rhetoric, emotions/affect, and psychological well-being among Mexican-origin youth. Social Science & Medicine 228, 240–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conradt E, Carter SE, Crowell SE, 2020. Biological Embedding of Chronic Stress Across Two Generations Within Marginalized Communities. Child Development Perspectives 14, 208–214. [Google Scholar]

- Cox J, Holden J, Sagovsky R, 1987. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. The British Journal of Psychiatry 150, 782–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox JL, Chapman G, Murray D, Jones P, 1996. Validation of the Edinburgh postnatal depression scale (EPDS) in non-postnatal women. Journal of affective disorders 39, 185–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreby J, 2015. U.S. immigration policy and family separation: the consequences for children’s well-being. Social science & medicine (1982) 132, 245–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards GS, Rushin S, 2018. The effect of President Trump’s election on hate crimes. SSRN Electronic Journal.

- Eskenazi B, Fahey CA, Kogut K, Gunier R, Torres J, Gonzales NA, Holland N, Deardorff J, 2019. Association of Perceived Immigration Policy Vulnerability With Mental and Physical Health Among US-Born Latino Adolescents in California. JAMA pediatrics 173, 744–753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg A, Branton R, Martinez-Ebers V, 2019. Counties that hosted a 2016 Trump rally saw a 226 percent increase in hate crimes, The Washington Post.

- Findling MG, Bleich SN, Casey LS, Blendon RJ, Benson JM, Sayde JM, Miller C, 2019. Discrimination in the United States: Experiences of Latinos. Health services research 54 Suppl 2, 1409–1418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming PJ, Lopez WD, Mesa H, Rion R, Rabinowitz E, Bryce R, Doshi M, 2019. A qualitative study on the impact of the 2016 US election on the health of immigrant families in Southeast Michigan. BMC public health 19, 947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford BQ, Feinberg M, 2020. Coping with Politics: The Benefits and Costs of Emotion Regulation. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences 34, 123–128. [Google Scholar]

- Fox M, 2022. How demographics and concerns about the Trump administration relate to prenatal mental health among Latina women. Social Science & Medicine 307, 115171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox M, Entringer S, Buss C, DeHaene J, Wadhwa PD, 2015. Intergenerational transmission of the effects of acculturation on health in Hispanic Americans: a fetal programming perspective. American journal of public health 105, S409–S423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gemmill A, Catalano R, Alcalá H, Karasek D, Casey JA, Bruckner TA, 2020. The 2016 presidential election and periviable births among Latina women. Early Human Development 151, 105203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gemmill A, Catalano R, Casey JA, Karasek D, Alcalá HE, Elser H, Torres JM, 2019. Association of Preterm Births Among US Latina Women With the 2016 Presidential Election. JAMA Netw Open 2, e197084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghimire U, Papabathini SS, Kawuki J, Obore N, Musa TH, 2021. Depression during pregnancy and the risk of low birth weight, preterm birth and intrauterine growth restriction- an updated meta-analysis. Early Human Development 152, 105243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillanders R, 2016. Corruption and anxiety in Sub-Saharan Africa. Economics of Governance 17, 47–69. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Barrera A, Lopez MH, 2020. Before COVID-19, many Latinos worried about their place in America and had experienced discrimination.

- Grossman D, 2017. Sexual and reproductive health under the Trump presidency: policy change threatens women in the USA and worldwide. Journal of Family Planning and Reproductive Health Care 43, 89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groulx T, Bagshawe M, Giesbrecht G, Tomfohr-Madsen L, Hetherington E, Lebel CA, 2021. Prenatal Care Disruptions and Associations With Maternal Mental Health During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Frontiers in Global Women’s Health 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hacker K, Chu J, Arsenault L, Marlin RP, 2012. Provider’s perspectives on the impact of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) activity on immigrant health. Journal of health care for the poor and underserved 23, 651–665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hackney KJ, Daniels SR, Paustian-Underdahl SC, Perrewé PL, Mandeville A, Eaton AA, 2021. Examining the effects of perceived pregnancy discrimination on mother and baby health. Journal of Applied Psychology 106, 774–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Prins SJ, Flake M, Philbin M, Frazer MS, Hagen D, Hirsch J, 2017. Immigration policies and mental health morbidity among Latinos: A state-level analysis. Social science & medicine (1982) 174, 169–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyt LT, Zeiders KH, Chaku N, Toomey RB, Nair RL, 2018. Young adults’ psychological and physiological reactions to the 2016 U.S. presidential election. Psychoneuroendocrinology 92, 162–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger N, 2001. Theories for social epidemiology in the 21st century: an ecosocial perspective. Int J Epidemiol 30, 668–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger N, Huynh M, Li W, Waterman PD, Van Wye G, 2018. Severe sociopolitical stressors and preterm births in New York City: 1 September 2015 to 31 August 2017. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 72, 1147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lara-Cinisomo S, Fujimoto EM, Oksas C, Jian Y, Gharheeb A, 2019. Pilot Study Exploring Migration Experiences and Perinatal Depressive and Anxiety Symptoms in Immigrant Latinas. Maternal and Child Health Journal 23, 1627–1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez MH, Gonzalez-Barrera A, Krogstad JM, 2018. More Latinos have serious concerns about their place in America under Trump. Pew Research Center 55. [Google Scholar]

- Marteau TM, Bekker H, 1992. The development of a six‐item short‐form of the state scale of the Spielberger State—Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI). Br. J. Clin. Psychol 31, 301–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez AD, Ruelas L, Granger DA, 2017. Household fear of deportation in Mexican-origin families: Relation to body mass index percentiles and salivary uric acid. American journal of human biology : the official journal of the Human Biology Council 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mefford MT, Mittleman MA, Li BH, Qian LX, Reynolds K, Zhou H, Harrison TN, Geller AC, Sidney S, Sloan RP, Mostofsky E, Williams DR, 2020. Sociopolitical stress and acute cardiovascular disease hospitalizations around the 2016 presidential election. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117, 27054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH, 1995. Minority Stress and Mental Health in Gay Men. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 36, 38–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morey BN, 2018. Mechanisms by Which Anti-Immigrant Stigma Exacerbates Racial/Ethnic Health Disparities. American journal of public health 108, 460–463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols VC, LeBrón AMW, Pedraza FI, 2018. Policing Us Sick: The Health of Latinos in an Era of Heightened Deportations and Racialized Policing. PS: Political Science & Politics 51, 293–297. [Google Scholar]

- Pascoe EA, Smart Richman L, 2009. Perceived discrimination and health: a meta-analytic review. Psychological bulletin 135, 531–554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philbin MM, Flake M, Hatzenbuehler ML, Hirsch JS, 2018. State-level immigration and immigrant-focused policies as drivers of Latino health disparities in the United States. Social science & medicine (1982) 199, 29–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roche MJ, Jacobson NC, 2019. Elections Have Consequences for Student Mental Health: An Accidental Daily Diary Study. Psychological reports 122, 451–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez RM, Torres JR, Sun J, Alter H, Ornelas C, Cruz M, Fraimow-Wong L, Aleman A, Lovato LM, Wong A, Taira B, 2019. Declared impact of the US President’s statements and campaign statements on Latino populations’ perceptions of safety and emergency care access. PloS one 14, e0222837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal L, Lobel M, 2020. Gendered racism and the sexual and reproductive health of Black and Latina Women. Ethnicity & Health 25, 367–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma S, Singhal S, Tarp F, 2021. Corruption and mental health: Evidence from Vietnam. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 185, 125–137. [Google Scholar]

- Simchon A, Guntuku SC, Simhon R, Ungar LH, Hassin RR, Gilead M, 2020. Political depression? A big-data, multimethod investigation of Americans’ emotional response to the Trump presidency. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 149, 2154–2168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith D, Ormseth M, 2019. It took a while, but L.A. formally declares itself a ‘city of sanctuary’, Los Angeles Times.

- Southern Poverty Law Center, 2020. Family separation under the Trump administration—A timeline.

- Spielberger CD, 1983. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory: STAI (Form Y). Consulting Psychologists Press, Palo Alta, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Tluczek A, Henriques JB, Brown RL, 2009. Support for the reliability and validity of a six-item state anxiety scale derived from the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. J. Nurs. Meas 17, 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torche F, Sirois C, 2019. Restrictive Immigration Law and Birth Outcomes of Immigrant Women. American journal of epidemiology 188, 24–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres JM, Deardorff J, Holland N, Harley KG, Kogut K, Long K, Eskenazi B, 2019. Deportation Worry, Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factor Trajectories, and Incident Hypertension: A Community-Based Cohort Study. Journal of the American Heart Association 8, e013086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentín-Cortés M, Benavides Q, Bryce R, Rabinowitz E, Rion R, Lopez WD, Fleming PJ, 2020. Application of the Minority Stress Theory: Understanding the Mental Health of Undocumented Latinx Immigrants. American Journal of Community Psychology 66, 325–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Deurzen I, 2017. And justice for all: Examining corruption as a contextual source of mental illness. Social Science & Medicine 173, 26–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velez BL, Campos ID, Moradi B, 2015. Relations of Sexual Objectification and Racist Discrimination with Latina Women’s Body Image and Mental Health. The Counseling Psychologist 43, 906–935. [Google Scholar]

- Wadhwa PD, Sandman CA, Porto M, Dunkel-Schetter C, Garite TJ, 1993. The association between prenatal stress and infant birth weight and gestational age at birth: A prospective investigation. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 169, 858–865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldinger R, 2018. Immigration and the election of Donald Trump: why the sociology of migration left us unprepared … and why we should not have been surprised. Ethnic and Racial Studies 41, 1411–1426. [Google Scholar]

- Walesiak M, Dudek A, 2020. The Choice of Variable Normalization Method in Cluster Analysis, In: Soliman K. (Ed.), Education Excellence and Innovation Management: A 2025 Vision to Sustain Economic Development During Global Challenges, pp. 325–340.

- Williams DR, Medlock MM, 2017. Health Effects of Dramatic Societal Events — Ramifications of the Recent Presidential Election. New England Journal of Medicine 376, 2295–2299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winders J, 2016. Immigration and the 2016 Election. Southeastern Geographer 56, 291–296. [Google Scholar]

- Young MT, Beltrán-Sánchez H, Wallace SP, 2020. States with fewer criminalizing immigrant policies have smaller health care inequities between citizens and noncitizens. BMC public health 20, 1460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeiders KH, Nair RL, Hoyt LT, Pace TWW, Cruze A, 2020. Latino early adolescents’ psychological and physiological responses during the 2016 U.S. presidential election. Cultural diversity & ethnic minority psychology 26, 169–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available from the corresponding or senior author upon reasonable request.