Abstract

Eating disorders (ED) and weight stigma pose significant healthcare challenges. Patients at higher weights, like some with atypical anorexia (AAN), may face increased challenges due to weight stigma. This study analyzed patients’ lived experiences with weight stigma in healthcare. Thirty-nine adult patients with AAN completed in-depth, semi-structured interviews regarding healthcare experiences. Guided by narrative inquiry approaches, transcripts were thematically coded. Across the illness trajectory (ED development, pre-treatment, treatment, post-treatment), patients reported that weight stigma in healthcare contributed to initiation and persistence of ED behaviors. Themes included “providers pathologizing patient weight,” which patients reported triggered ED behaviors and relapse, “provider minimization and denial” of patients’ EDs, which contributed to delays in screening and care, and “overt forms of weight discrimination,” leading to healthcare avoidance. Participants reported that weight stigma prolonged ED behaviors, delayed care, created suboptimal treatment environments, deterred help-seeking, and lowered healthcare utilization. This suggests that many providers (pediatricians, primary care providers, ED treatment specialists, other healthcare specialists) may inadvertently reinforce patients’ EDs. Increasing training, screening for EDs across the weight spectrum, and targeting health behavior promotion rather than universal weight loss, could enhance quality of care and improve healthcare engagement for patients with EDs, particularly those at higher weights.

Keywords: Weight Stigma, Atypical Anorexia Nervosa, Eating Disorders, Anorexia Nervosa, Body Size, Higher Weight Populations, Barriers to Care

1. Introduction

Eating disorders (EDs) are complex biopsychosocial conditions that pose significant challenges to diagnosis, treatment, and relapse prevention. Patient denial , minimization, and difficulty engaging in treatment contribute to illness persistence (Abbate-Daga et al., 2013; Couturier & Lock, 2006). Thus many frontline medical providers feel “unsure” about diagnosing and treating EDs and desire more training (Linville et al., 2010). Not surprisingly, provider attitudes toward patients with EDs often reflect frustration, hopelessness, lack of competence, and worry (Thompson-Brenner et al., 2012).

Atypical anorexia nervosa (AAN), is an ED estimated to impact .2%−4.9% of women during their lifetime, with lifetime prevalence estimates double or triple that of typical anorexia nervosa (AN; Harrop, et al., 2021). Both AAN and AN are characterized by severe caloric restriction, overvaluation of weight and shape, body image disturbance, and intense fear of gaining weight. Individuals with AN and AAN experience disordered eating behaviors (e.g., food rituals, obsessive calorie counting, secretive eating) and dangerous compensatory behaviors (e.g., compulsive exercise, self-induced vomiting, laxative/diuretic abuse). Additionally, individuals with AN and AAN experience body image distortion and preoccupation, resulting in time-consuming body checking rituals.

The defining element differentiating AAN from AN is body mass index (BMI); patients whose BMIs are within or above the normal range are designated “AAN” while those considered underweight are designated “AN” (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). However, the similarities between these two EDs has led some to recommend that these disorders be considered within the same diagnostic category (Harrop, 2022). Though individuals with AAN do not present as emaciated, they experience life-threatening medical consequences (Sawyer et al., 2016) at rates similar to AN (Peebles et al., 2010), one of the deadliest psychiatric disorders (Chesney et al., 2014). Further, those with AAN who with elevated BMI face more severe psychological symptoms compared to those without elevated BMI (Matthews et al., 2021; Sawyer et al., 2016).

While researchers have studied experiences of self-starvation in bodies with “normal” or higher BMIs for decades, AAN was only recently designated in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders 5th Edition (DSM-5) in 2013. Prior, AAN was referred to by many names, including ED Not Otherwise Specified (EDNOS), EDNOS-AN, “subthreshold AN,” “restrained ED,” “restrictive EDNOS,” and “EDNOS-weight” (Harrop et al., 2021). However, several of these categories only identified self-starvation in those with “normal” BMIs (e.g., EDNOS-AN), excluding those at higher weights. Similarly, prior to 2013, many providers were less aware of restrictive EDs in individuals at “normal” or high BMIs. While ED awareness has grown tremendously in the last several decades, medical education around EDs is limited in time and scope. Training often focuses on “stereotypical cases” such as clinical vignettes featuring classically thin presentations of AN (Mishra & Harrop, in press). Since a hallmark symptom of AN is emaciation, it is natural to fall back on these heuristic methods, at the expense of missing AN symptoms in higher weight individuals.

Weight stigma refers to how higher weight (“fat”) people are systematically devalued in societies that idealize thinness. Fat people1 experience discrimination, fewer opportunities, and other forms of systemic mistreatment including microaggressions, marginalization, and violence (Apos et al., 2013; Pausé, 2014). Weight discrimination occurs in employment, education, healthcare settings, and social relationships (Puhl & Heuer, 2009; Rudolph et al., 2009). Healthcare providers report strong negative attitudes towards heavier patients, inadvertently influencing provider perceptions, behaviors, and quality of care (Phelan et al., 2015). Physicians (including pediatricians) are more likely to believe higher weight patients are unattractive, less intelligent, and less likely to respond to clinical recommendations; nurses reflect similar attitudes (Budd et al., 2011). Provider weight bias has been hypothesized to increase healthcare avoidance and mistrust of providers (Phelan et al., 2015).

Debates persist regarding the long-term benefits of weight-centric health approaches. Obesity experts focus on obesity prevention via diet and weight management (Falconer et al., 2014), whereas other experts question the benefits of weight-centric healthcare, as BMI is a poor predictor of cardiometabolic health in normal and high BMI populations (Tomiyama et al., 2016). They argue that weight-centric approaches reproduce health inequities including unhealthy weight control behaviors, weight-cycling, and weight stigma, and instead advocate for weight inclusive health practices focused on health behaviors and wellness maximization regardless of a person’s weight (O’Hara & Taylor, 2018; Tylka et al., 2014).

This debate is particularly pronounced in pediatric spheres. Since the advent of the “obesity epidemic,” much emphasis has been placed on childhood obesity. For example, a 1978 review article (Coates & Thoresen, 1978) described current best practices for childhood obesity management which included: caloric restriction, anorectic drugs, physical exercise, therapeutic starvation (e.g., overseen by hospital staff or summer camps), bypass surgery (in extreme cases), and behavioral therapy. Since 1978, scientific knowledge regarding dieting, weight loss, and weight science has grown significantly. For example, researchers now acknowledge complex social and environmental factors involved in children’s weight (Reed et al., 2011), in addition to questioning the efficacy of long-term weight loss efforts (Fildes et al., 2015). Further, researchers have highlighted how seemingly “harmless” interventions, such as informing adolescents that they are “overweight,” could be correlated with increases in BMI (Hunger & Tomiyama, 2014) and ED severity (Mensinger et al., 2021). However, despite growing critiques regarding how to ethically address issues of weight in children, recent guidelines released from the Academy of Pediatrics (Hampl et al.) continue to promote an aggressive approach to childhood “obesity management.” Given this controversy, it is unsurprising many providers might struggle to discern best practices.

Weight stigma in healthcare may be particularly risky in pediatric settings when children are forming foundational beliefs about their growing bodies. Focusing on weight management goals in pediatric care versus more inclusive health aims may inadvertently lead to harm (O’Hara & Taylor, 2018; Tylka et al., 2014). To wit, dieting, disordered eating, and EDs appear to exist on a continuum of risk in ED development (Neumark-Sztainer et al., 2006). Longitudinal evidence has shown that dieting in childhood and adolescence is associated with increased likelihood of later EDs (Neumark-Sztainer et al., 2006). These data suggest that alternative approaches (rather than weight-loss) may be needed in pediatric settings to support lifelong health enhancement.

Because individuals with AAN present at higher weights compared to patients with AN, individuals with AAN are more likely to experience weight stigma. Previous research has suggested that this may complicate disease trajectories for AAN (Billings et al., 2013; Hamilton et al., 2022). For example, in a vignette study (Veillette et al., 2018) of a patient presenting with AN symptoms, mental health trainees were significantly more likely to diagnose patients who were underweight compared to those with normal or overweight BMIs. Similarly, heavier clients were recommended fewer therapy sessions compared to underweight clients. In another vignette study, participants assigned greater stigma to the patient with AAN compared to the patient with AN; similarly, the patient with AAN was also perceived to have significantly more control over their illness, compared to the patient with AN (Cunning & Rancourt, 2023).

Several qualitative studies have also highlighted the potential impact of stigma on patients with AAN. For example, in a study of Family Based Therapy (FBT), practitioners reported that their patients with AAN were more likely to have experienced higher weights as children (and weight-based teasing) compared to their patients with AN (Kimber et al., 2018). These practitioners identified that ED treatment often sent “mixed messages” to patients with AAN, telling them they needed to gain weight for recovery, while also sending messages about weight management and weight loss. The authors concluded that when treating patients with AAN, providers should empathize with patients’ fear of weight gain, while being wary of colluding with the ED. Similar themes were echoed in another study with FBT providers who treated patients with AAN, in which authors concluded that FBT practitioners reported differing opinions on weight restoration targets, particularly for higher weight patients (Dimitropoulos et al., 2019).

Within much of this literature, the patient perspective of AAN is notably absent. While several recent studies (Eiring et al., 2021; Kelly et al., 2021) have explored the experiences of mixed samples of individuals with AN and AAN, these studies did not report results specific to AAN. To our knowledge, only two qualitative studies have addressed the lived experiences of patients with AAN. In a case study, Harrop (2018) contrasted the ED treatment they received when they had an AN diagnosis compared to the ED treatment they received later as a higher weight patient. Harrop concluded that patients with AAN face compounded challenges as they confront the illness challenges of an ED and stigma, as their higher weight may be pathologized by society and the medical community (Harrop, 2018). In a more recent study, Harrop and colleagues (Harrop et al., 2023) examined the lived experiences of trans and nonbinary patients with AAN, and concluded that participants viewed their EDs as interconnected with their gender identity and experiences of social pressure and discrimination. Participants acknowledged the cooccurring pressures of thin body ideals and gender norms, highlighting the importance intersectional approaches when examining patient narratives.

1.1. The Present Study

This study aimed to address this gap in the literature by investigating the lived experiences of individuals with AAN. To shed light on patients’ experiences with potential weight stigma in healthcare, we explored the following questions:

How do patients with a history of AAN report experiencing weight stigma in healthcare settings?

What are patients’ perceptions of the impacts of these experiences?

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

Data were drawn from a longitudinal, mixed-methods study of individuals with histories of AAN. The parent study involved semi-structured interviews at baseline, 6-months, and 12-months in addition to survey data. Baseline interviews addressed participants’ ED initiation and development. Six-month interviews focused on participants’ experiences with healthcare providers, treatment seeking, and treatment. Twelve-month interviews addressed experiences of recovery or continued ED illness. This longitudinal approach allowed each interview to build upon the previous one, and facilitated in-depth data collection, increasing rapport, the development of complex narratives, and the ability to track changing perspectives over time. The current study analyzed the 6-month interviews on healthcare experiences. Six-month interviews typically took two hours, ranging from 1.5–4 hours. Survey data from the parent study were not used in this analysis.

2.2. Recruitment and Screening

Thirty-eight participants completed their 6-month interview, representing 97.5% of participants. Participants were recruited through ED treatment centers, provider referral, social media groups, snowball recruitment, and potential participants directly contacting the researcher. This study utilized purposive sampling with maximum variation, criterion, theory-based, and confirming/disconfirming strategies (Emmel, 2013).

Participants were screened by the first author (a mental health evaluator and medical social worker) using the ED Assessment for DSM-5 (Sysko et al., 2015) to verify history of AAN. To be eligible, women and non-binary persons assigned female at birth (AFAB) had to be age 18 or older, live in the US, speak English, and have experienced AAN. Those currently in inpatient or residential treatment settings and those with acute suicidality or psychosis were ineligible.

2.3. Sample Characteristics

Participants ranged from 18 to 74 years (M=35.6, SD=11.8). Seventy-nine percent (n=30) were cisgender women, and 20.4% (n=8) were trans/nonbinary, including one trans man and one trans woman. Regarding race, 74% (n=28) identified as white only, 13.1% (n=5) as Latinx, 7.9% (n=3) as Black, one (2.6%) as Alaska Native, one (2.6%) as Asian and Pacific Islander, one (2.6%) as Middle Eastern. Of note, 17.9% identified as (n=7) as multiracial (identities included in previous counts). Forty-two percent (n=16) received public assistance as children. Full demographic characteristics are found in Table 1. Of note, participants were not required to be in recovery; as such, participants presented at different points in their illness journeys. Although a weight loss cutoff was not used, all participants qualified for AAN diagnosis according to the EDA-5, and all lost at least 10% of their premorbid body weight during AAN.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Participants

| Pseudonym | Age | Gender | Sex Assigned at Birth | Sexual Orientation | Relationship Orientation | Race | Ethnicity | Highest Degree | Public Assistance Child? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bette | 38 | Nonbinary/genderqueer | Female | Pansexual | Monogamous | Caucasian/white | Celtic | Master’s | Yes |

| Elizabeth | 45 | Female | Female | Lesbian | Monogamous | Caucasian/white | Non-Hispanic | Master’s | No |

| Amanda | 33 | Female | Female | Heterosexual | Monogamous | Caucasian/white | Caucasian | Bachelor’s | Yes |

| Gretchen | 44 | Female | Female | Bisexual | Polyamorous, but prefer monogamous relationships | Caucasian/white | Western Europe | Bachelor’s | No |

| Joanna | 30 | Female | Female | Bisexual | Monogamous | Caucasian/white | Caucasian | Bachelor’s | No |

| Molly | 47 | Female | Female | Heterosexual | Monogamous | Caucasian/white | Gen-European | Bachelor’s | No |

| Tori | 32 | Female | Female | Bisexual | Monogamous | Caucasian/white | Caucasian | Some college | No |

| Abby | 30 | Female | Female | Asexual | Monogamous | Caucasian/white | Non-Hispanic | Master’s | Yes |

| Carly | 45 | Female | Female | Straight leaning | Open | Caucasian/white | Irish | Master’s | No |

| Dover | 36 | Female | Female | Bisexual | Currently monogamous | Caucasian/white | White, Finnish American | Master’s | No |

| Uki | 37 | Female | Female | Heterosexual | Monogamous | Alaskan Native | Non-Hispanic | Post-Baccalaureate | Yes |

| Grace | 22 | Female | Female | Straight | Monogamous | Caucasian/white | White | Some college | Yes |

| Hope | 30 | Nonbinary/genderqueer | Female | Queer/lesbian | Single | Biracial, White/Hispanic (Latinx) | Mexican | Master’s | Yes |

| Eli | 23 | Female | Female | Fluid | Monogamous | Latino | Latino | Bachelor’s | Yes |

| Lexi | 29 | Female | Female | Straight | Monogamous | Caucasian, Persian/Middle Eastern | Persian (Iranian) and European | Bachelor’s | No |

| Arati | 74 | Female | Female | None/queer | Monogamous | Caucasian/white | Northern European mutt | Bachelor’s | No |

| Mary | 26 | Female | Male | Homoflexible | Monogamous | Caucasian/white | Polish, Northwestern European | Bachelor’s | No |

| Josephine | 66 | Female | Female | Hetero to asexual | Monogamous | Caucasian/white | Northern European | Master’s | No |

| Riley | 40 | Female | Female | Bisexual | Polyamorous | Caucasian, Hispanic | Hispanic | Master’s | No |

| Candy | 28 | Female | Female | Queer | Monogs | Black, biracial | Half Kenyan | Bachelor’s | No |

| Cabaletta | 24 | Female | Female | Straight | Monogamous | Caucasian/white | Caucasian | Associate’s | No |

| Rosalie | 31 | Female | Female | Straight | Monogamous | Caucasian/white | Irish-Italian American | Bachelor’s | No |

| Layla | 38 | Nonbinary/genderqueer | Female | Bi queer | Monogamousish | Caucasian/white | Ashkenazi Jewish | Doctorate | No |

| Jen | 47 | Female | Female | Heterosexual | Monogamous | Caucasian/white | Caucasian American | Masters | No |

| Chelsea | 31 | Female | Female | Straight | Monogamous | Caucasian/white | White | Associate’s | Yes |

| Lynn | 28 | Female | Female | Straight | Monogamous | Caucasian/white | Caucasian | Master’s | No |

| Pseudonym | Age | Gender | Sex Assigned at Birth | Sexual Orientation | Relationship Orientation | Race | Ethnicity | Highest Degree | Public Assistance as Child? |

| Michelle | 40 | Female | Female | Lesbian | Married | Caucasian/white | White | Master’s | No |

| Veronica | 40 | Female | Female | Heterosexual | Monogamous | Caucasian/white | White | Bachelor’s | Yes |

| Carter | 18 | Male | Female | Pansexual | Monogamous | African American, Caucasian | African-American Caucasian | High school student | Yes |

| Gaia | 38 | Female | Female | Bisexual/pansexual | Monogamous | White, Asian, Pacific Islander | Italian, German, Scottish, Irish, Hungarian, Filipina, Indian | Bachelor’s | Yes |

| Daisy | 25 | Nonbinary/genderqueer | Female | Queer | Polyamorous | Caucasian/white | White | Bachelor’s | Yes |

| Ari | 21 | Female | Female | Unsure | Monogamous | Hispanic | Mexican | Some college | Yes |

| Charlie | 32 | Nonbinary/genderqueer | Female | Queer | Primary-partnered open | Caucasian/white | White | Doctorate | Yes |

| Sonja | 48 | Female | Female | Heterosexual | Monogamous | Caucasian/white | Ashkenazi Jewish | Doctorate | No |

| Marie | 51 | Female | Female | Heterosexual | Monogamous | Caucasian/white | Anglo Saxon/American | Masters | No |

| Jessie | 25 | Nonbinary/genderqueer | Female | Bisexual/queer | Polyamorous | Caucasian/white | Jewish | Some college | No |

| Carrie-Ann | 26 | Female | Female | Gay | Monogamous | Black, Latina | Afro-Latinx | Bachelor’s | Yes |

| Sisu | 36 | Nonbinary/genderqueer | Female | Queer | Ethically non-monogamous | Caucasian/white | Italian, German, English | Bachelor’s | Yes |

2.4. Epistemological Approach and Theoretical Frame

This research project was framed using interpretive hermeneutic and critical feminist approaches. An underlying assumption in interpretive frameworks is that there is no objective, absolute truth, but rather, “truth” depends on our social locations, perspectives, and interpretations (Rosenberg, 2016). Within this study, stories were the main source of data. Storytelling is situated within a critical feminist paradigm, in which it is a means of resistance and a tool for countering dominant narratives that reinforce established power structures. Personal narratives (e.g., “stories”), particularly stories from marginalized groups (e.g., higher weight patients in this analysis), add diverse voices to traditional histories and have the power to tell transformational stories about society (Stone-Mediatore, 2003). We also drew on elements of narrative inquiry, specifically regarding constructing shared narratives between participants (Wells, 2011). Central to this interpretation of narrative is the concept of the simple hermeneutic—that we tell stories with lenses that interpret meaning. It is then the job of the interpretive scientist to analyze and interpret the various narratives (the double hermeneutic – the researcher interpreting the interpreting subject) (Stone-Mediatore, 2003).

Regarding illness stories specifically, we drew on Kleinman’s (1988) work centering patient illness narratives and explanatory models. To Kleinman, understanding the patient’s illness experience was critical to a physician’s understanding of their illness and treating their disease. Thus, to best understand and treat AAN, Kleinman would argue that providers first need to understand the patient’s understanding of their own illness experience.

Finally, this research was undertaken from a liberatory, intersectional stance (Crenshaw, 1991; Freire, 1970). A liberatory stance is built on the assumption that research is (and cannot be) neutral; a primary goal of liberatory research is to ameliorate social inequities and injustices (Sandoval & Davis, 2000; Smith, 2012).

2.5. Researcher Positionality

Qualitative research standards suggest researchers consistently engage in reflexive practices (i.e., reflection, memos, discussion). The authorship team have disciplinary backgrounds in social work, psychology, and public health. Multiple individuals have ED histories, are neurodivergent, and/or chronically ill. Our team also shared the following identities: white (5/5), larger bodied (3/5), non-heterosexual (4/5), trans/nonbinary (2/5), highest degree (4/5 PhD, 1/5 Masters), and low income as child (2/5).

All interviews were conducted by the first author, who identifies as a white, queer, larger bodied, nonbinary person with an ED history. In the 12-month interview, participants were asked to reflect on how the interviewer’s social identities impacted them. Participants commented that the interviewer’s larger body size was “reassuring”; queer and trans/nonbinary participants mentioned they felt less pressure to “explain” themselves due to reading the interviewer as genderqueer. Participants of color did not bring up the interviewer’s whiteness; however, the research team did not interpret this to mean that race “was not an issue.” Rather, we suspect that participants may have felt more comfortable commenting on areas of similarity (e.g., body size, sexual orientation, gender), and less comfortable exploring differences. When a participant of color, with whom the interviewer had significant rapport, was specifically asked to comment on the impact of the interviewer’s race, the participant noted that she felt comfortable due to the interviewer’s size and the fact that she was “used to” navigating primarily white spaces.

2.6. Measures and Procedures

To prepare for the interview (two weeks in advance), participants were invited to create an image depicting their interactions with medical, healthcare, and/or ED treatment systems in response to the prompt, (“What has it been like to be an ED patient in your healthcare system?” Twenty-seven participants (71.1%) submitted images. Participants eddiscuss the meaning of their art during the interview. “Summary images” were selected to illustrate various themes as they related to the interviews. While arts-based methods are more novel research approaches, they are gaining traction, with examples including photo elicitation, digital storytelling, creative writing prompts, collage, journaling, visual arts, and mapping (Golden, 2022; Leavy, 2020). In this study, art prompts were included to a) prime participants to consider the main concepts of the interview, b) offer a touchpoint for participants during the interview, c) promoteexamination of experiences or feelings that may be difficult to verbalize, d) facilitate dissemination, e) provide nonverbal communication options, and f) offer a therapeutic, trauma-informed support as participants recounted difficult experiences.

On the day of the appointment, participants completed a structured diagnostic DSM-5 interview to establish time frames for ED symptoms and diagnoses. Participants then completed semi-structured interviews regarding their healthcare experiences, help seeking, treatment experiences, and provider interactions. The interview guide is located in Appendix A.

2.7. Ethics Considerations

All study procedures were approved by the [University Institutional Review Board], and all participants provided verbal and written informed consent. Study data were collected and managed using Research Electronic Data Capture (Harris et al., 2009), a secure web-based application designed to support data collection.

2.8. Data Analysis

2.8.1. Transcript Preparation

Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed, validated, and de-identified. All names in this manuscript are pseudonyms. Notes were recorded on participant appearance, affect, mannerisms, and emotional valence, in addition to interviewer reflections and emerging themes. Transcription utilized a modified verbatim format omitting false starts and filler words. During participant validation, 2 of 38 participants provided minor corrections to their transcripts.

2.8.2. Data Immersion

Transcripts were summarized with brief hermeneutic narratives (Hollway, 2000). Following Sheard and Marsh (2019), pen portraits were produced, summarizing each participant’s transcript, diagnostic interview, memos, and artwork. Portraits also identified major themes for each participant and included summative quotes.

2.8.3. Coding Guide

To develop the coding guide, four coders read the first 20 participant interviews and generated over 200 potential codes. These inductive codes (arising from the data) were added to a list of a priori codes (arising from previous literature and theory) developed during study conceptualization and literature review. The following code types (as categorized by Miles, Huberman, and Saldana, 2014) were generated: descriptive codes, in vivo codes, process codes, emotion codes, and holistic codes. Codes were condensed and organized hierarchically. Stigma codes were sorted into externalized (stigma from others or society) and internalized (stigma towards oneself) codes, based on extant literature detailing how weight stigma is experienced. Other a priori codes included stigma impact and provider disciplines. Experiences of weight stigma were coded across four a priori codes based on illness trajectories: 1) ED risk and development (when ED behaviors emerged), 2) ED pre-treatment (during a symptomatic ED prior to care), 3) during ED treatment, and 4) post-treatment (during partial or full remission).The final coding guide was discussed and approvedby all coders. Code definitions were developed iteratively, with six codes added after transcripts 21–39 were coded. The final coding guide is available upon request.

2.8.4. Coding Process

Transcripts were analyzed by four coders using established coding conventions, with disagreements resolved by discussion and consensus (Miles et al., 2013). Coders met regularly to discuss data interpretations and identify areas of similarity and dissimilarity among participants.Codes were applied using Dedoose Version 8.0.35, a web-based data management application permitting multiple coders to code data concurrently (SocioCultural Research Consultants, 2018). The first author re-reviewed all transcripts to identify missing or wrongly attributed codes.

2.8.5. Theme Development

Following coding, researchers discussed emerging themes. Disconfirming cases were sought to deepen understanding (Emmel, 2013). Matrices were developed tracking weight stigma themes across illness periods. Primary quotes (approximately 10–30) were selected for each participant, based on the hermeneutic narratives and pen portraits. Following this, the first author worked in collaboration with a community partner (a local fat activist) to organize quotes into distinct, related “buckets.” Themes were interpreted and finalized by the research team through group discussions about areas of similarity and dissimilarity among the participants. Illustrative quotes for each type of stigma and time period were recorded to determine the most robust themes. Additionally, summary images were identified for each time period, matching participant artwork to the most salient qualitative themes.

2.8.6. Member Checking and Expert Review

The first author compiled a document with all themes organized into hierarchical related categories for each illness period themes, accompanied by supportive quotes. This document was emailed to participants for member-checking and feedback. Of 29 (76%) participants who elected to review findings prior to publication, seven (18.4%) provided feedback that was incorporated into this article. Additionally, the manuscript was also reviewed by the community partner who assisted with theme development.

3. Results

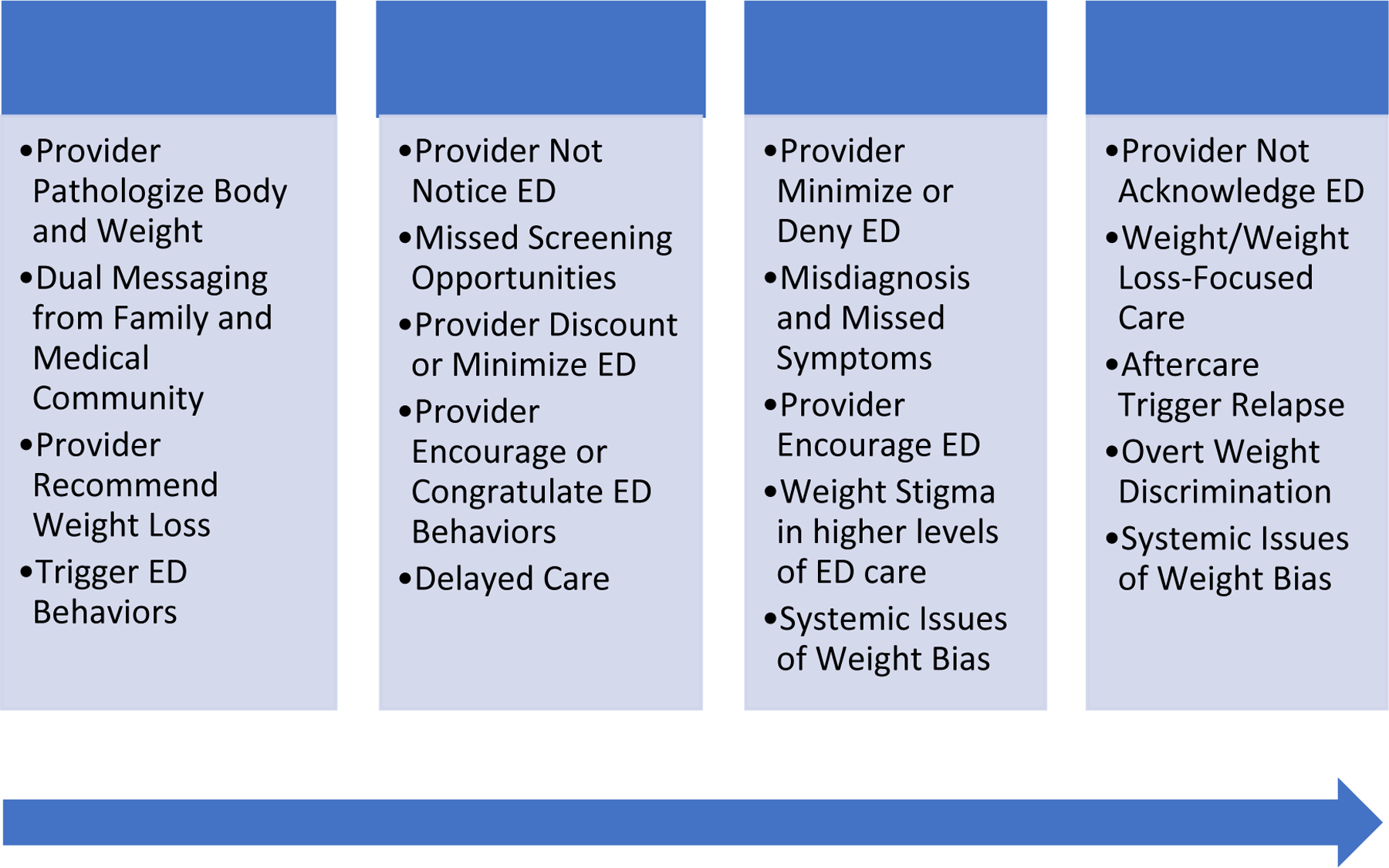

Figure 1 outlines the major themes across patient illness trajectories. A full list of all themes with participant artwork is available (Harrop, 2020). Participants reported experiencing weight stigma in healthcare throughout each ED stage. To summarize, as young children, participants learned that their fat bodies were unhealthy, and were instructed by family and providers to control their bodies through food and exercise. As their EDs developed and progressed, participants “fl[ew] under the radar” (stated by Uki) due to their lack of emaciation. Participants who received treatment reported ongoing messages to lose weight, even while in ED treatment. Participants who reached full or partial remission often experienced more overt forms of weight stigma from providers due to gaining weight in recovery. In the following sections, we describe the major themes; themes are italicized. Of note, in our findings we report on participants’ interactions with “providers,” which included a broad range of healthcare providers including physicians, ED specialists (therapists, dieticians, medical staff), nurses, and other specialists, in primary care, emergency, and specialty care settings.

Figure 1.

Weight stigma themes identified across the illness trajectory.

3.1. ED Risk and Development

Table 2 summarizes themes reported during ED development. Beginning in childhood, participants reported that providers pathologized their weight and growing bodies. Those who were heavy children received messages from providers that their weight was too high and posed imminent health risks. Eli recalled going to the doctor with her mother for a sore throat and being lectured on BMI. Seven-year-old Carly was told to lose weight because of frequent ear infections; she started viewing her body as a “problem we have to fix, because it’s shameful.” As a young teen, during an urgent care visit to cauterize a nosebleed, Mary was told that she was “destined for hypertension, heart disease, and diabetes.” Sonja described “brutal” messages about her body as she approached puberty (10–11 years old): “ [my pediatrician] said, ‘You’ve gained 10 pounds this year. That’s going to be a real big problem... You better watch how you’re gaining weight.’ That was brutal for so many reasons.” Pathologizing messages were particularly salient for trans/nonbinary participants who reported compounding feelings of body shame due to their bodies being perceived as too large and not conforming to societal gender norms.

Table 2.

Themes and Illustrative Quotes of Weight Stigma in ED Risk and Development Periods

| Weight Stigma in ED Risk and Development Periods |

| Pediatrician Pathologizing Body and Weight |

| Carly: 99.9% of the things… medical professionals [said] are less than helpful. Like “Ooh, you’re not even on the growth chart?” ...But it wasn’t until I think, like, the doctor said something that it was, like, a “problem we have to fix” …because it’s shameful… “You’re not trying hard enough and there’s something wrong with you.” |

| Gaia: My weight was like 99th percentile plus, so he didn’t quite tell me that I was fat, but really, really pointedly told me that that was a lot. And I was like, “Oh, okay, I guess I weigh too much.” |

| Sonja: It set in motion this idea that, like, your body size was actually something that you could control, because, you know, your pediatrician is telling you, “You need to control this.” |

| Compounding Messaging from Family and Medical Community |

| Mary: So, I was too fat for the regular doctor, but not fat enough for the fat doctor… My mom and I resolved we’d just take care of it ourselves, which, I think, is the point at which we started trying our own brand of Weight Watchers, and later, Atkins. |

| Joanna: Both of my parents were in medicine, and they are both very diet-oriented and fat-phobic… I think my experience would have been a lot different if all the adults in my life besides medical practitioners had been able to look past my BMI and look at behaviors. |

| Elizabeth: I guess the stuff around weight with my mom. But I think my mom initiated that. I don’t think the doctor initiated. |

| Pediatrician Recommending Weight Loss |

| Joanna: I thought that my primary care physician was doing the right thing by recommending Weight Watchers and warning me that if I didn’t get a handle on my weight now, as a teenager, that it would snowball and be out of control… Now I know that they were actually harmful. |

| Chelsea: I first discussed diets with a healthcare provider when I was like 16 years old… He suggested Weight Watchers. |

| Elizabeth: He [MD] recommended Children’s Weight Watchers… So that was back when I was nine or 10. |

| Provider Triggering Disordered Eating or ED |

| Sonja: I was already getting messaging from my parents that my body was too big… [pediatrician] just reinforced whatever fears that I had that my body was wrong… that’s when the real thoughts of restriction started to really settle in. |

| Carly: I was at the doctor for… chronic ear problems… and left with a diet… I think that probably started my ED journey. |

| Ari: [My pediatrician] be like, “Looks like your weight’s going down” …I was restricting. I remember she told me that I was… still overweight… I had been going through the fasting… that was the first time I went home and purged. |

While some participants reported first hearing weight stigmatizing messages from providers, others recalled messages from family, with compounding messages from the medical community solidifying beliefs that their bodies were unacceptable. Though Sonja’s parents told her that her weight was too high, it was not until her physician reinforced this message that the “real thoughts of restriction started to settle in.” Parental concerns over participants’ growing bodies were exacerbated by pediatrician admonishments to “watch their weight.” Participants frequently reported being put on their first diet by parents following advice from pediatricians recommending weight loss. In response to medical recommendations, parents started diet programs (Mary’s mother “started trying our own brand of Weight Watchers”), withheld “forbidden foods” (Carly’s mom withheld birthday cake), and modeled other ED behaviors (Bette’s grandmother taped thinspiration to the refrigerator).

Finally, a subset of participants reported that conversations with providers triggered initiation of ED behaviors. Elizabeth traced her ED to her pediatrician recommending Weight Watchers at nine years old. Carly stated, “so thinking about… ‘First, do no harm…’ My first ED was doctor-prescribed and mother-approved and then perpetuated for 40 years.” Similarly, when Ari’s pediatrician commented that she was “still overweight,” after she had begun fasting and losing, Ari was so crushed that she purged for the first time the evening after that doctor’s appointment, starting an ED journey that continued into adulthood: “I was restricting… [My pediatrician] told me that I was… overweight… that was the first time I… purged.”

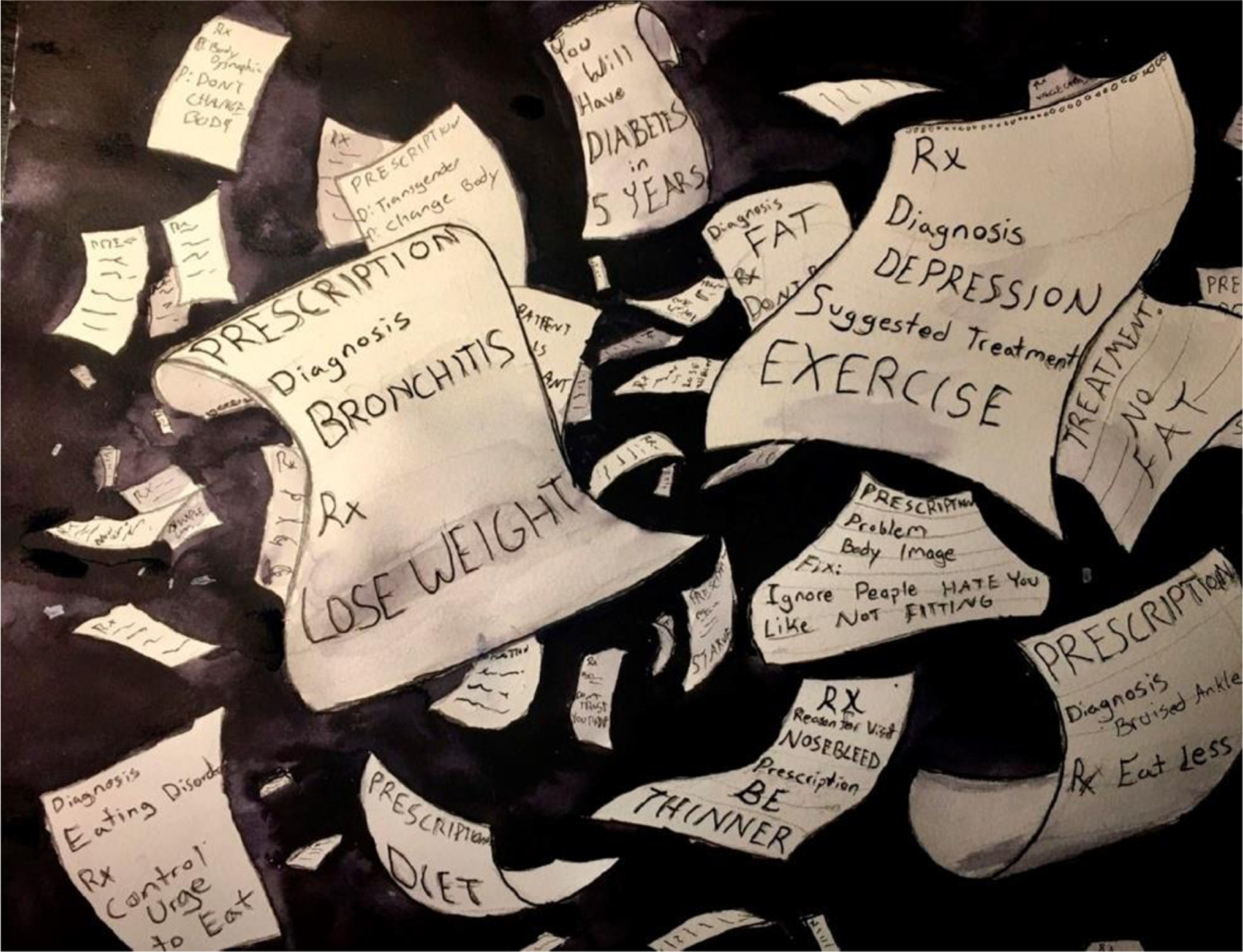

3.1.1. Summary Image

Figure 2 shows the summary image for ED Risk and Development. In this image, Mary depicts her experience as a collection of prescription pad notes, swirling against a black background. On the prescription notes, she recorded various healthcare encounters, many of which occurred during her childhood and adolescence: “Diagnosis: depression. Suggested treatment: exercise,” “Diagnosis: Transgender. Prescription: Change Body,” “Problem: Body Image. Fix: Ignore People Hat[ing] You. Like Not Fitting [In]”, and “Diagnosis: Eating Disorder. Rx: Control Urge to Eat.” She summarized her healthcare experiences as a “whack-a-mole” experience where “every person I’ve seen has ended up almost causing as many problems as they’re trying to solve.” Mary’s art integrates each of the themes from this section, demonstrating the harm she experienced from her pediatrician pathologizing her body (“Reason for visit: Nosebleed. Prescription: BE THINNER,” “Diagnosis: bronchitis. Prescription: lose weight,”), the compounding messaging from family and the medical community (“Diagnosis: Bruised Ankle. Rx: Eat Less,” a message she reports hearing from her aunt), the harm of her pediatrician recommending weight loss (“Prescription: BE THINNER,”), and how her providers triggered her ED (“Prescription: STARVE”).

Figure 2.

Summary Image of Weight Stigma in ED Risk and Development Periods

Image Description:

A multimedia piece of art created by “Mary” with a dark gray and black background done in watercolor. Many pieces of light-colored prescription pad paper swirl around the image. Prescriptions and diagnoses are written on them, including, “Diagnosis: bronchitis. Prescription: lose weight,” “Diagnosis: depression. Suggested treatment: exercise,” “Diagnosis: Transgender. Prescription: Change Body,” “Problem: Body Image. Fix: Ignore People Hate You. Like Not Fitting [In]”, “Diagnosis: Eating Disorder. Rx: Control Urge to Eat,” and “Diagnosis: Bruised Ankle. Rx: Eat Less.”

3.2. Pre-Treatment for EDs

Table 3 summarizes pre-treatment themes. When patients initiated ED behaviors (e.g., caloric restriction, fasting, eliminating foods, calorie counting, compensatory behaviors), physicians praised these behaviors and the resulting weight loss. Dover was congratulated for her “perfect weight and size alignment” after beginning restriction and compulsive running. As an adolescent, Lexi was praised for her obsessive consumption of fruits and vegetables to the exclusion of other foods. Her male physician also warned that her BMI was “high,” while reassuring her that the weight was “distributed” in an “attractive” and “reassuring” way. At 16 years old, after losing over half her body weight in a year, Mary’s physician encouraged her to lose “a little more” and congratulated her “achievement:”

Table 3.

Themes and Illustrative Quotes of Weight Stigma Pre-Treatment for ED

| Weight Stigma Pre-Treatment for ED |

| Provider Encourage or Congratulate ED Behaviors |

| Riley: Some of the worst damage that I have done to myself has been through dieting and has been supported by my doctors. Doctors… helped me find better ways to starve myself for 30 years. |

| Tori: Two weeks later… I had lost like 20 pounds… She was like “oh how did you do it?” I was like “I just haven’t been eating…” “Oh… it’s okay I’m so proud of you for losing weight…” I just remember thinking, huh… alright, as long as I’m losing weight, I guess it’s okay. I knew it wasn’t… My size has made it so that I am laughed at, and told to continue my ED… |

| Amanda: I just got reamed out for 20 minutes by this [OBGYN]… I needed to lose weight. That I shouldn’t be fat. I was terrified and mortified. Yeah, it just solidified my ED. |

| Providers Not Noticing or Seeing ED |

| Lynn: [Doctors] just look at you, and if you look healthy, you’re good to go. But there can be a lot going on underneath even if you’re in a healthy weight range… |

| Lexi: I’ve had a doctor say, “Well, you don’t look anorexic. You don’t look underweight... do you want to look like someone who is anorexic?” I was like, “I have no idea why you are asking this or how to answer this question.” |

| Jen: If you’re round, you just don’t have a restrictive ED. You never did. Or maybe you did, but what was your lowest? Oh, your lowest was a BMI of overweight? Well, you know… It doesn’t count. Nobody sees it except for, you know, true, true, true ED professionals. Nobody sees it as possible. |

| Missed Screening Opportunities |

| Bette: I was running at least 3 miles a night, and I was not really eating. …I would eat equal packets and ice... When I had, sort of like, talked to a doctor about this, their sort of response was like, “Well, your weight looks good. You know, your blood pressure is low, your heartbeat’s low. That means you’re healthy.” And I would think that if I had a smaller body, those behaviors would have been looked at in a different way. |

| Arati: I don’t remember their ever talking about [my ED] other than to say to put it in the context of some of my labs and to say you really need to exercise more. You really need to lose weight... |

| Gretchen: There was never a concern [for an ED]. I think the doctor was like, “Maybe you’re losing [weight] too fast…” I don’t even know if I got that… There was always just a pat on the back. |

| Providers Discounting or Minimizing ED |

| Joanna: I think that if I had been smaller and not having a period, they might have looked at my nutritional intake as a consideration of why I’m not having a period, but that wasn’t ever considered. |

| Eli: I [told my doctor] that I thought I had an ED... he said that I was doing just fine... and I could actually probably lose a little bit of weight… I knew that I was sick… but I just wasn’t sick enough. I wasn’t physically emaciated or thin enough to be considered. |

| Bette: All the times that I tried to communicate that I’m really tired, and my hair’s falling out, and my skin is just bleeding; it’s so dry... and all these other things. And providers would just answer back with... you know, “Are you putting on lotion?” |

| Delay of Care |

| Riley: I have been before doctors my entire life, and no one diagnosed me with an ED until I went into treatment and said, “I have an ED and I need you to pay attention.” |

| Sisu: I think my body size is the reason why I was never diagnosed with an ED until this study… I think my body size has affected everything about my medical care and ED care. |

| Charlie: I could have potentially been diagnosed really early on this—Before I had, like, really deeply-entrenched behaviors, and thoughts and coping mechanisms, and I could have lived a less stressful life. |

Fifty-eight percent of my body weight gone... I was weak, cold all the time, lost most of my muscle mass... [Doctor] “you’ve lost some weight... Keep it up.” ... [I] was eating under 800 calories a day... But it was all rendered invisible because I was a previously fat person who had become the “correct” size. I was a success story.

Candy was complimented on her thin, muscular frame; Molly reported that physicians expressed “polite congratulations” following weight loss. Josephine concluded, “they’ve never gone into how I’m doing it… it was just encouragement to keep doing [it].” These findings emphasize the extent to which participants internalized potentially offhand provider remarks that reinforced their EDs. Amanda concluded that her pediatrician “just solidified my ED.”

Though their bodies were shrinking, doctors did not notice EDs, failing to recognize their changing bodies and behaviors as problematic. Providers rarely asked how participants were losing weight or screened for EDs. Lynn recalls being told she “looked healthy” in a “healthy BMI range,” despite eating under 1000 calories and running daily. Marie and Mary described themselves as “invisible” to providers. Lexi’s provider told her she didn’t “look anorexic” when she reported struggling with restriction and purging. Veronica expressed dismay that providers ignored her “clearly malnourished” form (with clavicles protruding and lanugo, a fine hair that covers the body when malnourished), dismissing it as “normal” athleticism: “it’s ‘runners’ body.” Daisy summarized her experience with her provider:

She still told me “I was too heavy to have an ED.” …I’m tracking all my food, barely eating, exercising multiple hours a day, freezing all the time, standing up and getting dizzy, acid reflux, throwing up my food weekly, low heart rate, anemia, always bruised all over, my hair was falling out.

Others reported having no conversations regarding EDs. Though Uki sought help for amenorrhea (which resolved after nutritional rehabilitation), she was never asked about restriction or compulsive exercise. Her amenorrhea was blamed on her fitness regimen, and she was advised to lose additional weight to restore menses. Carrie-Anne reported that no provider discussed her ED, though “nurses sometimes ma[d]e comments on my weight.” Carrie-Anne never received care, treating her ED by attending 12-step meetings. She suspected her ED could have identified if providers had asked about her eating and weight loss as an adolescent.

Participants reported physical symptoms of malnutrition or purging (e.g., amenorrhea, lanugo, fainting, dizziness, pitting edema, hair loss, dry/bleeding skin, fatigue, weakness, blood in vomit) to their providers who missed opportunities for ED screening. Even when patient reports were validated by clinician-gathered measures (e.g., low heart rate, elevated bilirubin, orthostatic changes, weight loss), little follow-up occurred. Amanda was briefly asked “Are you starving yourself?” after lab work showed elevated bilirubin. She denied starvation, no follow-up was recommended, and she never returned for care. Bette was advised to “use lotion” for their dry, bleeding skin. In high school, Riley had repeated episodes of fainting and electrolyte imbalance requiring hospital admission, but was not screened for an ED: “You have a child who is passing out… whose potassium drops so low they have to be hospitalized… No one ever suspected that I might have an ED… [because] I was fat.” Similarly, Gaia stated, “I had told him [physician] that my hair was falling out… he said that was normal… we were talking about why my heart was racing. I hadn’t eaten for like 21 hours.”

When patients discussed their ED behaviors, providers often discounted or minimized their ED. As a teen, Eli suspected she had an ED and asked her physician; her doctor insisted she was “okay,” and “could actually probably lose a little bit of weight.”Eli wondered how much shorter her ED illness may have been had she received treatment when she first sought care, instead of eight years later. Eli concluded, “I knew that I was sick… but I just wasn’t sick enough.” These thoughts fueled her ED for years to come.

After being diagnosed by her therapist with a restrictive ED, Tori’s physician told her she was “too overweight” and declined treatment referrals. Daisy, one of the youngest participants, was told their size precluded them from having an ED. Gretchen’s pediatrician insisted her 16-pound weight loss in two weeks was “water weight.” When Bette called the nurses line at 16 years old and reported her purging behaviors and having vomited “a considerable amount of blood,” she was told, “oh that’s fine. That’s just esophageal tearing.” No follow-up or referrals were provided. Participants indicated that these interactions nurtured denial and minimization.

Bette concluded:

I feel like if I had a smaller body right from the start, I would have gotten help when I was 15, for sure, when everybody started noticing I was losing a lot of weight and at 16 when I was vomiting blood. I would have gotten help when I kept going to all the doctors and I kept asking them, what can I do? … I feel like I had all these opportunities to get the help that I needed…

The combined impact of these healthcare experiences led participants to conclude that their higher weight contributed to delays of care. Participants frequently wondered how their illness courses (and lives) could have been different with earlier intervention. Uki poignantly questioned, “What if anyone would have asked? What if I didn’t have to fight another decade? What could my life be like now, had someone noticed, asked, or even just suggested my behaviors were problematic?”

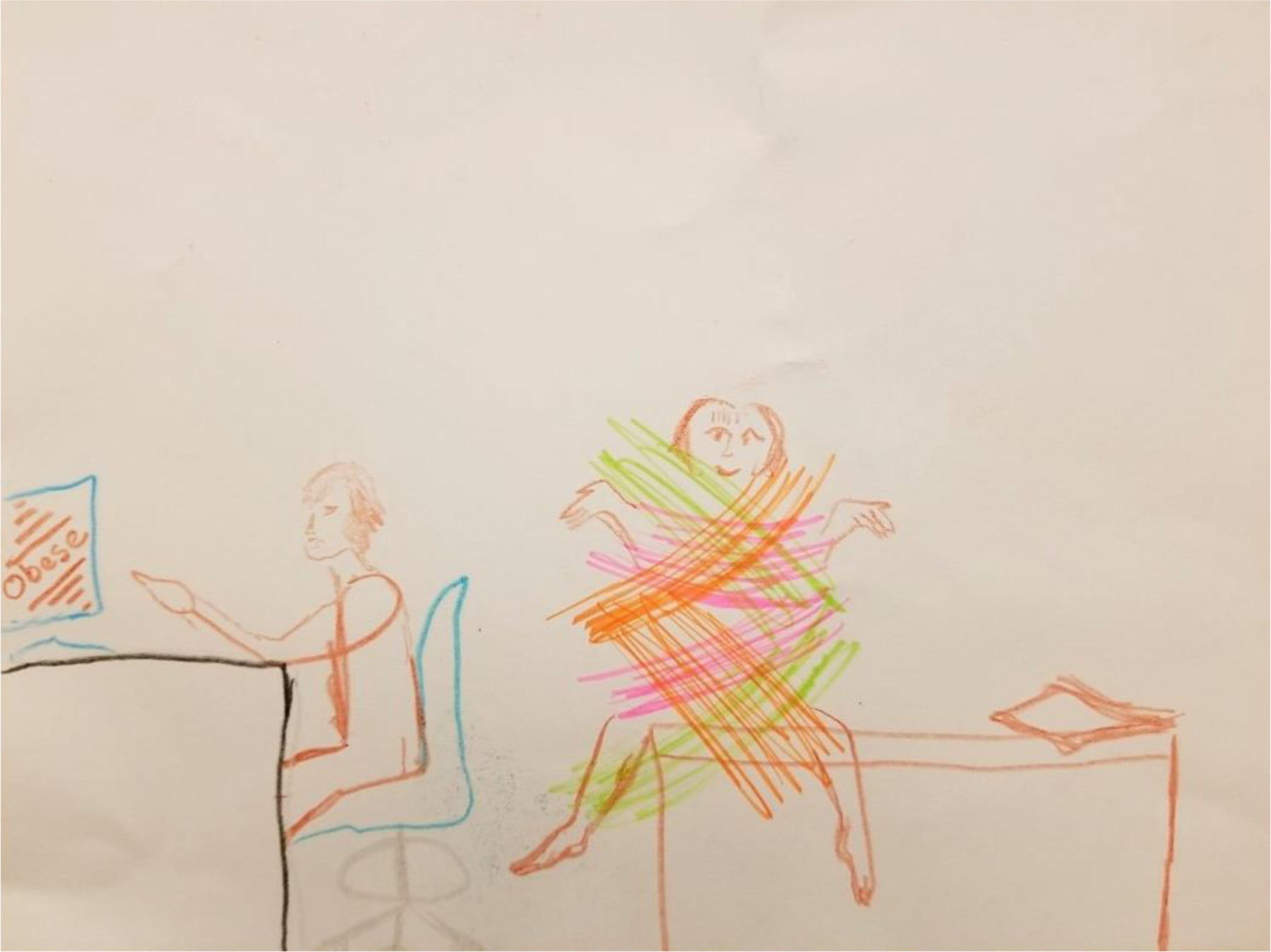

3.2.1. Summary Image

The remaining summary images (Figures 3–5) are located in Appendix B. In the summary image for the pre-treatment period, Molly depicts her experience as a patient, sitting on an exam table, while her doctor stares at a computer screen that reads “Obese.” Colors swirl around her, obscuring her body. She explains, “they don’t see me… They’re not really listening. All they see is fat… Obesity, obesity, obesity… They don’t see anything else… They’re not seeing me as a person.” Molly’s image and interview depict the main themes of this section, including providers not noticing the ED (“when I’m starving myself if I’m still fat, they don’t notice that I’m starving myself”), missed screening opportunities (“‘Here I am. Here’s my whole body.’ Isn’t there anything else to say besides you’re too fat?”), provider encouraging ED behaviors (“he said, ‘Your number one goal in life should be weight loss.’”), and delay of care (“I haven’t been in that much treatment for my ED”).

Figure 3.

Summary Image of Weight Stigma Pre-Treatment for ED

Image Description:

A drawing created by “Molly” done with colored pencil and highlighter depicts a patient sitting on an exam table in a doctor’s office. The doctor is sitting at a desk, gesturing at the computer showing the diagnosis: “obese”. The patient is enveloped by swipes of brown, orange, pink, and bright green gathered strokes, obscuring their body.

Figure 5.

Summary Image of Weight Stigma Post-ED Treatment

Image Description:

A drawing by “Carly” made using fine tip markers on light green paper depicts a patient’s experience at the doctor’s office. The sign saying “doctor office” is enveloped in a storm cloud, with heavy rain and a tornado underneath. The patient is very small, while the doctor (who is saying “No!” and pointing) is much larger. Words are written in different places across the drawing, including, “You’re fat,” “Healthy,” “You’re unhealthy,” “Just join Weight Watchers for life,” “You’ve done it before. You know how to do it. You are skilled at losing weight.” A scale is on the right of the image, with “Too fat” written above it.

3.3. During Treatment for ED

Table 4 summarizes themes during ED treatment. While 26.3% of participants in this study had not received treatment, three quarters had received ED treatment. However, despite being in ED treatment, providers continued to encourage ED behaviors. Marie’s ED therapist gave her a diet book. Abby’s provider recommended a gluten-free diet for weight loss. Cabaletta’s providers oscillated between recommending weight loss, encouraging her to stop purging and restricting, and recommending weight loss following weight restoration. These confusing, conflicting suggestions spurred distrust in treatment and recovery.

Table 4.

Themes and Illustrative Quotes of Weight Stigma in ED Treatment

| Weight Stigma in ED Treatment |

| Provider Encouraged ED Behaviors |

| Marie: She [provider] was really toxic for my ED… she ended up giving me a diet book… because she thought that if I was more comfortable with what I was eating, that I would eat |

| Cabaletta: I go back, and he’s [doctor] like, “you need to lose weight” and there’s like this constant cycle of, like, losing weight versus not using an ED. |

| Joanna: The interaction after I just said, “You know I am not sure how to hold your food restriction advice with the fact that I’m in recovery from anorexia. I don’t know how to hold both those.” |

| Provider Minimize or Deny ED |

| Marie: I said, “I have an ED.” And she looked at me. She said, “You don’t look like you have an ED.” |

| Grace: When I started becoming eating disordered later, I don’t think I was taken seriously. |

| Beth: All… others were kind of either overlooked or glib or didn’t understand the ramifications of what the disorder does or doesn’t do. I would say… it’s been mostly negative. |

| Misdiagnosis and Missed Symptoms |

| Layla: I was diagnosed with compulsive overeating during one of my most restrictive points. |

| Jessie: Even when I was diagnosed with bulimia, okay… that wasn’t really accurate, because I wasn’t really bingeing, but they assumed, “this fat person must binge.” …the advice was “you shouldn’t do that ‘cause it won’t help you lose weight.” |

| Jen: [My body size] had everything to do with it. “I wasn’t in any medical danger” or if I was, it wasn’t looked for. |

| Weight Stigma Experiences at Higher Levels of Care |

| Abby: [In treatment] People were treated very differently because they were at different weights. |

| Joanna: Other folks making statements about there being a limit on how much weight someone should gain before it becomes a “problem.” |

| Lexi: In a lot of ED treatments, you get in higher levels of care, the milieu or care staff is often new or less educated around EDs and can sometimes just make stupid comments. |

| Systemic Issues of Weight Stigma in Healthcare |

| Bette: [if I were thin] I think that I would’ve been able to get PHP, and I would be able to stay in it longer... |

| Lynn: The ED behavior started coming back, I was exercising significantly more… she wanted me to go back to residential… My insurance was trying to cut me to IOP. |

| Michelle: I wish [my insurance] hadn’t sent me home. The conversation about suicide and the hospital, disclosing [the abuse], having to move to an apartment by myself, and stepping down to IOP all happened in the same week. How can you hear all of that and still shove that client to a lower level of care? |

Similarly, providers minimized participants’ EDs, leading participants to feel their ED symptoms were taken less seriously than their thinner peers. Providers told Elizabeth that she didn’t “look like they had an ED.” After inpatient admission for suicidality and food refusal, Carter, a trans Black teen, was excluded the ED group because of their weight: “[Providers] told me that I don’t “meet the numbers” and I couldn’t be a part of the [ED] group even though they said I had an ED… They just said basically it wasn’t bad enough for me to meet with that group.” Additionally, while these experiences affected white, cisgender participants, provider minimization was more pronounced for participants with multiply marginalized identities, such as participants of color, trans/nonbinary, and those in poverty.

Participants also reported instances of misdiagnosis. In ED treatment, Layla was diagnosed with “compulsive overeating” despite ingesting only bone broth and vegetables for months and losing 22% of their body weight. Layla attributed this misdiagnosis to their higher weight. Abby was diagnosed with bulimia when she did not binge, a requirement for bulimia diagnosis. Participants also reported providers assumed binge or purge behaviors, while failing to screen for restriction. This contributed to missed symptoms, such as Ari’s likely orthostasis (reflecting her body’s inability to regulate its own blood pressure), Marie’s kidney injury, and Uki’s pitting abdominal edema and bradycardia (indicating possible cardiac and electrolyte imbalance), all conditions requiring medical stabilization.

Participants also reported weight stigma in higher levels of ED care, occurring in intensive outpatient, partial hospitalization, and residential treatment. Within higher levels of care, weight stigma took on a different tone, as participants received treatment within therapeutic milieus with ED peers in thinner bodies. Participants believed their experiences differed from their peers, with providers seemingly less concerned with and less likely to believe larger patients. Participants cited fatphobic remarks (which went unchallenged) from peers and treatment providers, contributing to feelings of inadequacy and exclusion. Participants with multiple marginalized identities (participants of color, trans/nonbinary, lower income) commented that higher levels of care were particularly fraught spaces, as few treatment staff and peers reflected their identities. Hope (larger bodied, lesbian, biracial, nonbinary, low income) explained they experienced “a lot of anxiety when I see [a provider] who is just super thin, and super pretty, and super white—like all the things that I’m not… It’s just really hard when you when you walk into a room and no one else looks like you.”

Finally, participants reported systemic weight bias in healthcare. Notably, no participant believed they received adequate ED treatment. Participants universally reported that insurance coverage prohibited higher levels of care or prematurely ended coverage while they (and their providers) believed higher levels of care were still needed. Participants also reported having to “fight insurance” for coverage (e.g., appealing decisions, taking legal action), and others accepted lower levels of care or no care at all.

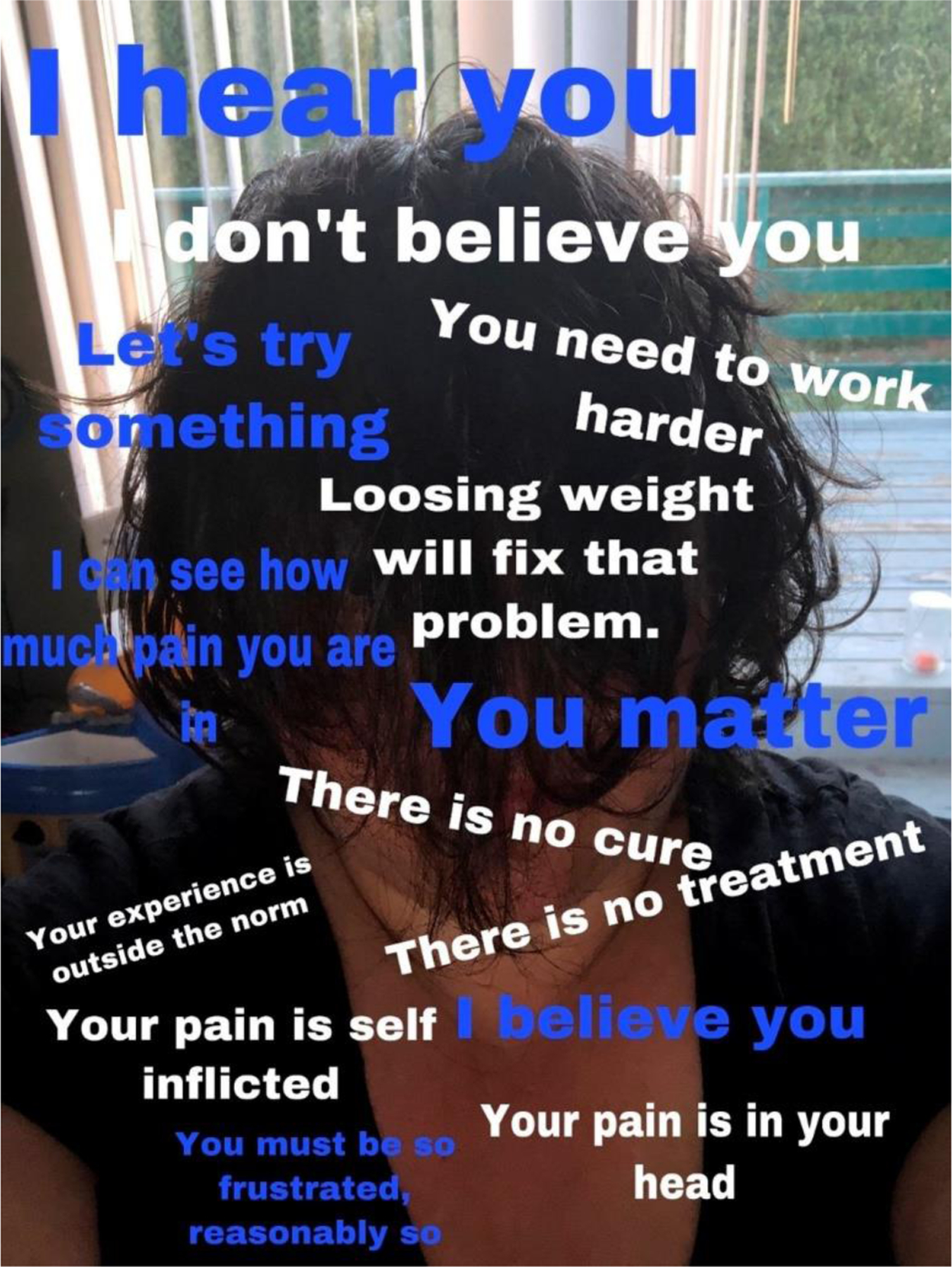

3.3.1. Summary Image

The summary image for the ED treatment period depicts Layla’s experience as a higher weight patient, who was unable to get ED care once diagnosed due to insurance and childcare issues. Their image features a picture of a person with black hair obscuring their face, with text overlays of quotes from providers that exemplify the main themes of this section, including providers encouraging ED behaviors (“Losing weight will fix that problem. You need to work harder.”), providers minimizing or denying the ED (“Your pain is self-inflicted,” “I don’t believe you”), and systemic issues of weight stigma in healthcare (“there is no treatment”).

3.4. Post-Treatment

Table 5 summarizes themes reported post-treatment. Even after patients were treated for EDs, providers disbelieved or failed to acknowledge their EDs. Uki’s provider falsely assumed her ED was “obviously not happening right now” only six months after discharge from residential care. Similarly, Elizabeth, who struggled with intense cognitive ED symptoms post-treatment, reported her ED was “not seen as real.” She attributed this to “not look[ing] emaciated” following weight restoration. Candy’s cardiologist disputed her ED diagnosis, suggesting she was not “telling the truth” about her medical history; another provider prescribed her a 500-calorie daily diet. Likewise, Lexi reported her providers said she didn’t “look anorexic” when she disclosed her ED.

Table 5.

Themes and Illustrative Quotes of Weight Stigma Post-Treatment (Relapse Prevention)

| Weight Stigma Post-Treatment in Relapse Prevention |

| Providers Not Acknowledging ED |

| Candy: I was just like, “well I’ve been anorexic…” He said… “You weren’t anorexic. You have Binge ED.” |

| Elizabeth: I don’t look emaciated, [so] either it’s not even been on people’s radars or it’s… something that’s so in the past. It’s not even on my problem list... It’s been ignored... not seen as real. |

| Uki: I see this doc... “So, tell me about this ED thing, obviously, it’s not happening right now.” [I] was like, “No, I’m not currently using behaviors, but I’ve only been out of treatment for six months.” ...Just like, “I doubt your story and I just think that this thing in your medical record is completely useless.” |

| Weight- and Weight-Loss Focused Healthcare |

| Candy: I always told them, “I have an ED, like, prior history. I cannot diet...” And I would frequently--doctors be like, “Well you could diet.” ...Like only if you want to get better. |

| Abby: I’ve been told by other providers that I need to lose weight... they didn’t care about the fact that I had ED on my chart. It just didn’t matter to them. |

| Riley: I have had continuously through my life had doctors tell me to lose weight… including the last almost three years while I’ve been in recovery… |

| Aftercare Triggering Increased ED Cognitions or Relapse |

| Amanda: [I’m] terrified of maybe a full-blown relapse because I’m avoiding going to doctor because of the immediate uncomfortableness in the room, one-on-one. |

| Joanna: [The doctor] was a challenge to some of the new beliefs I was trying to adopt [in treatment]. It made me even more scared of sugar than I already was, and made me doubt the treatment approach |

| Abby: I had a conversation with that doctor [to see] whether or not they could leave out my weight information on… the summary page that they print out… A notation of “obesity” was just super, super triggering. |

| Overt Discriminatory Medical Care |

| Carly: I’ve had quite literal disdain from providers based on the size of my body. |

| Sisu: I had an acupuncturist make comments about my body and like how my arms look swollen, really they’re just fat. |

| Josephine: the one who would not touch me even to take my pulse or listen to my heart… he was very uncomfortable with my body size. |

| Systemic Issues in Healthcare |

| Rosalie: I don’t get health care anymore… My health insurance is shit… You only have a select amount of providers. [I don’t want] a fat-shamer or someone who is going to promote weight loss on you. It’s a nightmare. |

| Lexi: In ED treatment facilities, it’s... much more common to see people in thinner bodies [as] providers and that just kind of fucks with your head... |

| Grace: We’re [ED patients] struggling hard… because we’re just pushed through the system. We’re not actually helped. |

Additionally, participants reported experiencing weight- or weight loss-focused healthcare following treatment. After one experience, Bette felt the medical community had become the “voice of [their] ED,” agreeing with their ED more than contradicting it. Though Arati explained her ED history and desire to maintain a stable weight, her physician regularly recommended weight loss. Participants who disclosed their EDs and requested providers not discuss weight loss were repeatedly told to lose weight and labeled “non-compliant.” Tori was recommended weight loss surgery (for a sinus infection). Carly summarized her experience saying, “Doctors quite literally do harm by prescribing a diet even when there is a fucking ED listed in my medical chart.”

Participants reported that weight-loss focused aftercare triggered increased ED cognitions or relapse. When Abby’s doctor spoke as an “authority” figure telling her to lose weight, this “trigger[ed her] ED.” Similarly, Veronica said that medical professionals believed her ED was preferable to “being fat;” their comments exacerbated her recovery fears rather than enhancing her motivation. She maintained a subthreshold ED diagnosis for years. Sisu identified receiving a restrictive diet from the physician as the “beginning of when my orthorexia really deepened.”

For patients who recovered into larger, fatter bodies, experiences of overt discrimination were more pronounced. Larger participants were treated “less than humanely” by providers after weight restoring to higher body weights These experiences bolstered their ED fears, making it more challenging to commit to recovery. Participants also reported experiencing anticipatory stigma and healthcare avoidance, as participants feared future stigmatizing interactions with providers. Participants with multiple marginalized identities (participants of color, trans/nonbinary, lower income) again reported experiencing weight stigma differently. Candy described the intersection of her identities poignantly:

As a fat, Black woman in particular, [that] was something that I’ve been perceived of even when I was at my thinnest. I just was consistently seen as “non-compliant” by providers… But when I got fat, it got a lot worse… They were just observing my ‘non-compliance,’ and that I was stupid, that I was ignorant, that I was lazy… In those moments, they were taking me back into my ED.

Additionally, participants expressed concern about systemic weight stigma in healthcare, such as a lack of size-inclusive providers, lack of medical equipment for larger bodies, and discriminatory health insurance policies.

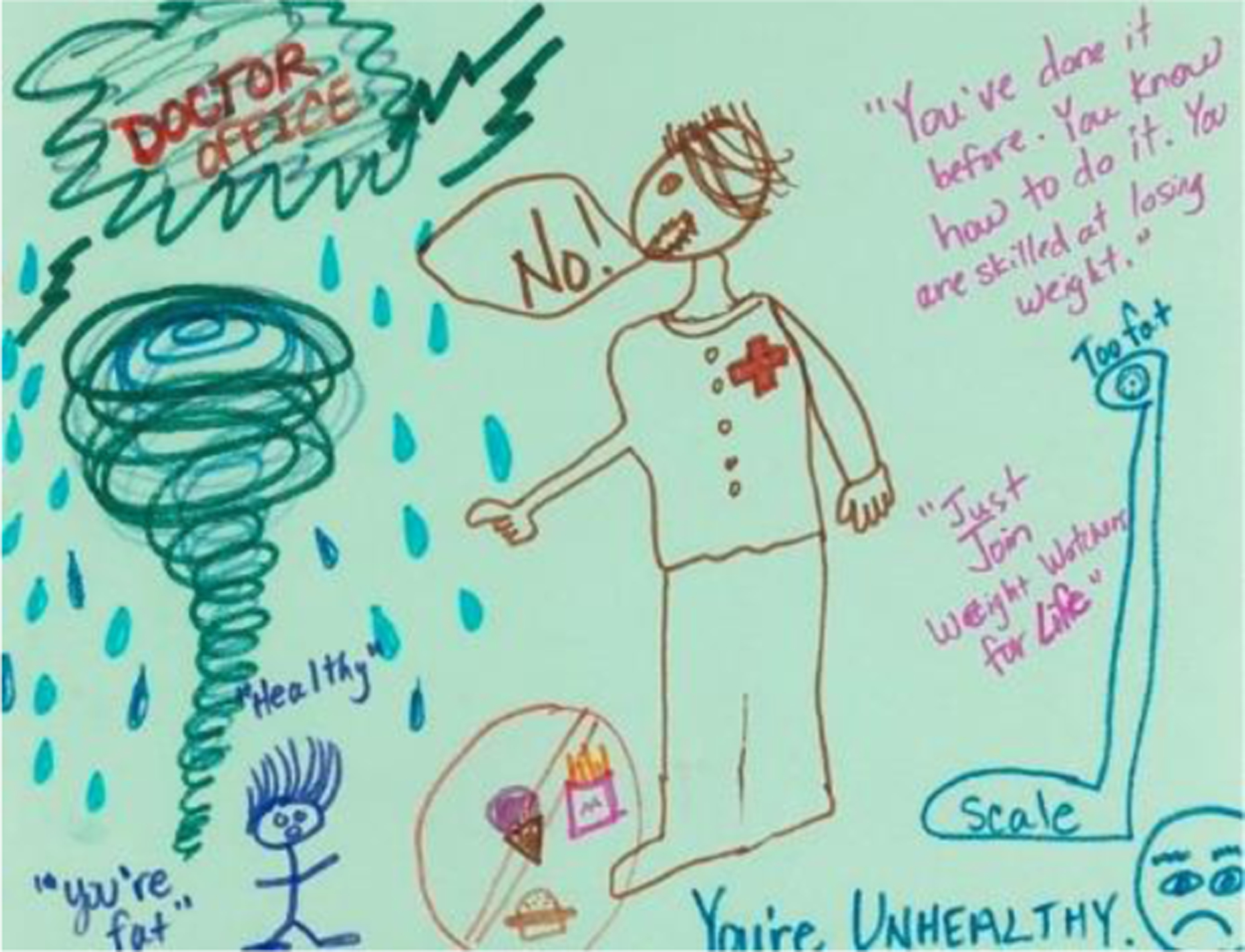

3.4.1. Summary Image

In the summary image for post-ED treatment, Carly depicts her experiences as a small stick-figured character who is now “healthy” followingED treatment. As she approaches her doctor’s office, represented by a black thunder cloud (a “scary place and it’s mistrustful, and you do not want to go there…unless you absolutely have to”), a tornado swirls, representing “getting sucked up into their culture and cycling around in that for years” with raindrops representing “all the tears that I cried from shame, from medical professionals and family, because I’m fat.” Over her stick-figure body, a larger-than-life doctor points at her accusingly saying “No!” with a scale in the background. Her art depicts several of themes from this section, including providers not acknowledging her ED (“You’ve done it before. You know how to do it. You are skilled at losing weight”), weight-focused healthcare (“you’re fat,” “too fat”), poor treatment of recovering fat patients (tears of shame), and overt discriminatory care (thunderclouds, tornado).

4. Discussion

A hallmark of EDs is patients’ difficulty recognizing their need for help. For participants in this study, minimization and denial persisted for years, sometimes decades, often aided by healthcare providers. Participants had difficulty viewing their ED behaviors as problematic when providers recommended similar behaviors (restriction, weight loss, exercise) and perceived their larger bodies as unhealthy and needing weight loss. For these patients, their EDs were obscurred by their larger or seemingly “healthy” body size. This theme is echoed in other literature, when peers, family members, or providers judged patients “not sick enough” (Eiring et al., 2021). For example, in Eiring and colleagues’ study (2021), participants with AAN and AN reported experiences of “not being skinny enough” to have an ED, needing to “prove” their ED, and needing to achieve “weight-based thresholds in order to access ED treatment,” all themes reflected in our current analysis. As Mary summarized, her ED was “rendered invisible, because I was a previously fat person who had become the correct size.” This aligns with previous researchers who asserted that in absence of more visible indicators, AAN is less readily identified, contributing to treatment delay (Hamilton et al., 2022; Hartmann et al., 2014; Thomas et al., 2015).

Participant minimization was mirrored by providers’ behavior and persisted through post-treatment. This was evident in themes of denial, disbelief, failure to diagnose, screen, or refer, even when participants displayed hallmark malnutrition symptoms. Providers ascribed malnutrition symptoms to athleticism (for thinner participants), and more often, to higher weight. In fact, Uki was told both—that her heartrate was low due to her intense CrossFit regimen, and that her menses would resume if she lost more weight. Screening for EDs across the weight spectrum with any malnutrition symptoms (e.g., rapid weight loss, fainting, orthostasis, bradycardia, amenorrhea) could facilitate quicker diagnosis.

Additionally, when participants lost weight, providers lauded their “achievements,” supporting previous findings that patients with AAN lose proportionally more body weight before receiving care (Peebles et al., 2010; Sawyer et al., 2016). Failure to assess and recognize malnutrition in patients not visibly underweight led to care delays, missing opportunities for diagnosis and referral. This finding aligns with previous research that patients with AAN may experience longer duration of symptoms and delays of care compared to low-weight patients (Hughes et al., 2017; Sawyer et al., 2016). Many participants wondered how their lives could have been different with earlier intervention. Studies linking early intervention to better outcomes suggest that identifying patients earlier is paramount (Fichter et al., 2006; Treasure & Russell, 2011).

Themes of providers pathologizing weight and praising ED behaviors were reported throughout participants’ illness experiences, often beginning in childhood. Hearing that their bodies were “unhealthy,” “destined for disease” and death, “didn’t fit the numbers,” and were “off the curve” further damaged patients’ body image, fueling driven weight loss. This aligns with literature showing that, controlling for BMI, patients who believe their weight is unacceptable struggle with increased disordered eating behaviors (Haynes et al., 2018). Further, participants who viewed their bodies as “wrong” and “controllable” approached healthcare visits with fear and shame. If “acceptance of body and self” is a hallmark of ED recovery (Bachner-Melman et al., 2018), such messaging would certainly impede improvement.

Participants reported that providers also pathologized their bodies during and following ED treatment, including during inpatient treatment and while they were severely restricting caloric intake. For these patients, providers recurrently recommended the very behaviors patients were attempting to stop (e.g., restriction, compulsive exercise, weight monitoring), unwittingly reinforcing ED behaviors. Additionally, patients reported overt experiences of weight discrimination in discussions of weight and eating behaviors. Participants with the highest BMIs reported overt discrimination such as allegations they were “lazy” or “noncompliant.” These experiences align with findings that higher weight patients encounter more negative attitudes by medical professionals (Buxton & Snethen, 2013; Lee & Pausé, 2016), which likely negatively impacts trust and patient engagement.

Finally, participants also reported experiencing systemic weight stigma, for example by insurance companies and in ED treatment center milieus. This aligns with recent research exploring experiences of weight stigma within ED treatment settings (Chen & Gonzales, 2022; Harrop, 2018). Because patients with EDs routinely experience distorted body image and internalized weight stigma, weight stigma in ED treatment is particularly concerning as providers may unwittingly reinforce the disordered, fat-phobic beliefs of patients (Harrop, 2018). Additionally, participants noted that stepping down in levels of care too early led to cyclic re-admissions. They postulated their illness trajectories were lengthened due to chronic undertreatment, suggesting a link between systemic stigma and illness duration.

4.1. Implications

The lived experiences of these patients highlight the need for provider education in screening for EDs across the weight spectrum. While patients with AAN may not present with visible emaciation, screening for malnutrition symptoms (e.g., heart rate, amenorrhea, dizziness, orthostasis, and hypothermia) in addition to restrictive and compensatory ED behaviors is efficient and inexpensive, and may facilitate illness identification.

These data also highlight the detrimental impacts of universal weight loss or weight management recommendations. Instead, health-promoting self-care recommendations are needed (Tylka et al., 2014). Providers who inquire about past and present diagnoses and behaviors, assess nutritional intake, and screen for ED behaviors (e.g., fasting, purging, compulsive exercise, bingeing) and cognitions are more likely to recommend health behaviors that do not exacerbate harm.

Some larger bodied participants reported such traumatic experiences that they concluded seeking care was more dangerous than going without. This cycle of stigma, mistrust, fear, and avoidance interfered with effective healthcare for years. With weight stigma, its social acceptability adds to the implicit bias that operates below awareness. Promoting health equity requires providers to engage in critical self-examination of implicit biases to avoid missing unexpected symptoms, failing to ask basic questions, discounting truthful reports, pathologizing ED remission, and recommending inappropriate behaviors. To do otherwise risks malpractice, creates a culture distrust, and causes patient harm, especially given patients’ high esteem for providers. Participants cared what providers said and took their messages to heart. By listening to and approaching patients with curiosity and concern, providers can play a pivotal role in reinforcing healthy behaviors for patients on difficult recovery journeys. This is especially important for patients whose bodies do not align with societal beauty standards.

4.2. Future Research Directions

This study highlights the need to study systemic inequities in treatment access for higher weight individuals with EDs. It would be prudent to investigate if disparities exist in insurance coverage (e.g., number of days in higher levels of care, insurance denials, appeals, etc.) for ED patients at different BMIs. Additionally, this research highlights the importance of developing and testing ED assessments and screeners that can be utilized in healthcare settings to identify EDs in patients with higher weights. Future research should also include providers themselves (ED specialists and general practitioners) to investigate provider awareness of internalized weight bias and its impact on patient care. Finally, evaluating the long-term effects of weight stigma interventions for providers is needed.

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

Study strengths include the use of audio recording, transcription with multiple validation (research assistant, interviewer, participant), multiple coders, hermeneutic summaries and analysis, iterative coding, member checking, triangulation with arts-based methods, and qualitative software. The primary coder (first author) also practiced self-reflexive memo writing and sought expert consultation.

Nonetheless, this study has important limitations. Although a validated diagnostic measure and structured interview were used to verify participant diagnoses, these tools may be less sensitive to OSFED subtypes compared to threshold disorders (Hartmann et al., 2014). The retrospective design required some participants to recall events that occurred decades prior, limiting confidence in recall, although current perspectives were captured. Despite the diversity of the sample, analyses were limited or absent for some subgroups (e.g., participants assigned male at birth, Asian, and American Indian); future studies should include greater representation from underrepresented groups. Finally, this study did not exclude participants who experienced other EDs in addition to AAN within their lifetime. Accordingly, experiences should not be considered unique to AAN, but rather informative about the range of possible experiences with AAN.

4.4. Conclusion

To our knowledge, this is the first qualitative study to explore experiences of weight stigma in healthcare settings for patients with AAN. Participants reported experiencing weight stigma in healthcare throughout their ED journeys, from risk development to relapse prevention. Specifically, participants reported that pediatrician appointments focused on weight loss contributed to the onset of ED behaviors, and lack of ED screening prolonged disordered behaviors. Aftercare visits focused on weight loss weakened recovery, and in some cases, triggered relapse. Thus, weight stigma delayed care, led to suboptimal treatment environments, and lowered healthcare utilization. Such findings suggest that addressing weight stigma in healthcare as it manifests interpersonally, in provider behavior, and in larger systemic ways, could improve speed of treatment referrals, quality of care, and patient engagement.

Supplementary Material

Figure 4.

Summary Image of Weight Stigma in ED Treatment

Image Description:

Artwork created by “Layla” in which text overlays a photograph of a person in a black shirt looking down with their black hair in front of their face. There is both white text, representing what the participant heard from healthcare providers and blue text representing what they wished they had heard from providers. The white text reads “I don’t believe you,” “You need to work harder,” “Loosing weight will fix that problem,” “There is no cure, “ “There is no treatment,” “Your experience is outside the norm,” “Your pain is self inflicted,” and “Your pain is in your head.” The blue text reads “I hear you,” “Let’s try something,” “I can see how much pain you are in,” “You matter,” “I believe you,” and “You must be so frustrated, reasonable so.”

Highlights.

Atypical anorexia patients reported weight stigma in care throughout their illness

Medical weight stigma contributed to eating disorder initiation and persistence

Providers frequently disbelieved and failed to screen higher weight patients

Medical weight stigma contributed to healthcare avoidance and treatment delay