Letter (New Observation):

Bilateral globus pallidus internus deep brain stimulation (GPi-DBS) is increasingly used in the treatment of medically-refractory dystonia in children, including for status dystonicus. GPi-DBS has proven effective for DYT-TOR1A, DYT-KMT2B, DYT/CHOR-GNAO1, DYT-THAP1, DYT-SGCE and MxMD-ADCY5 1, though the full spectrum of monogenic hyperkinetic disorders with a favorable response to DBS remains to be established. Here we report the case of a 7-year-old male with UBA5-related epilepsy-dyskinesia syndrome (NM_024818.6: c.1111G>A, (p.Ala371Thr); c.110C>T (p.Thr37Ile)) who presented with medically-refractory status dystonicus and showed a rapid and sustained response to GPi-DBS.

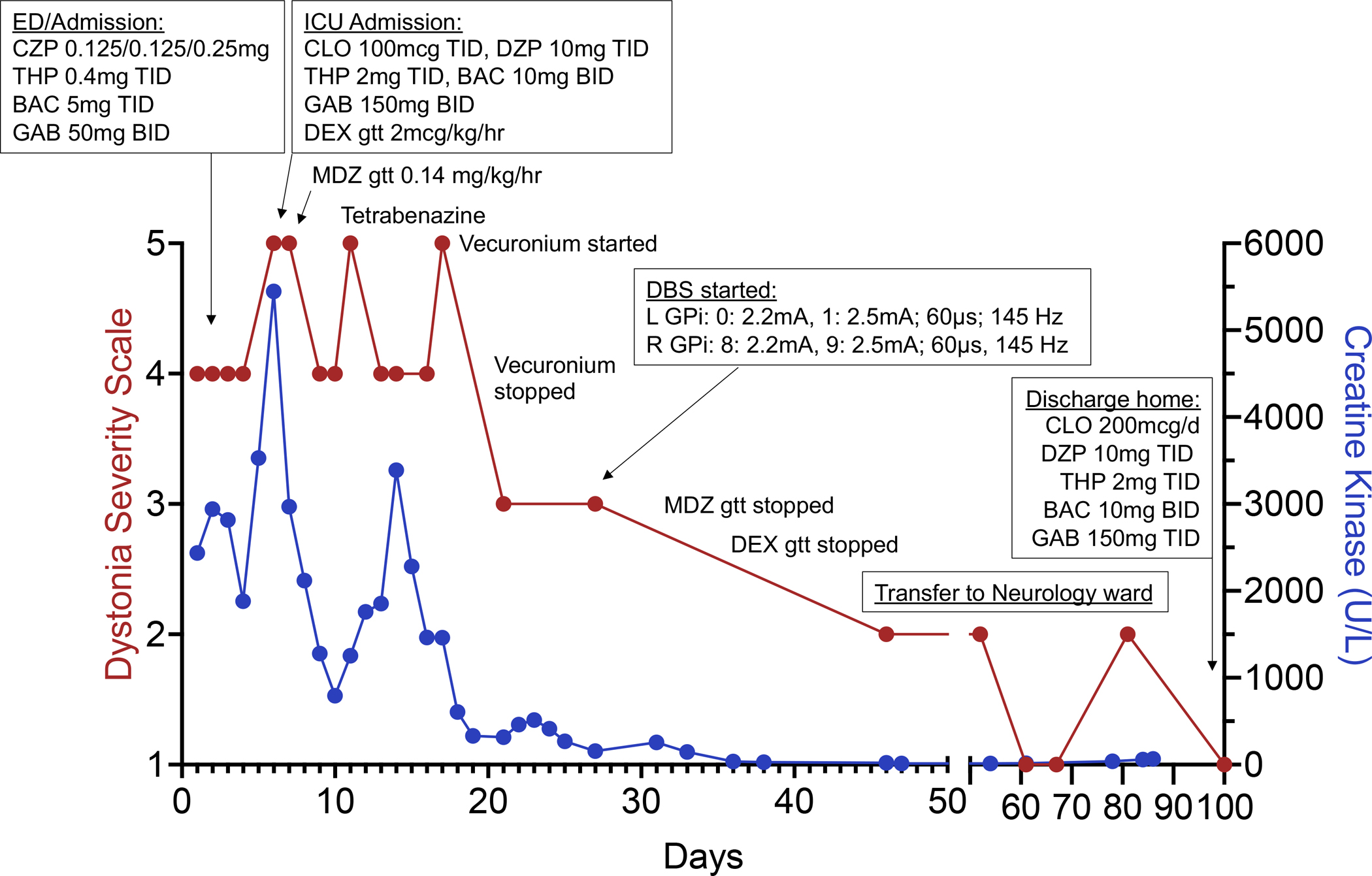

In line with the phenotypic spectrum of UBA5-related disorder 2–4, the patient presented with a developmental epileptic encephalopathy with intellectual disability (non-verbal), axial hypotonia, spastic tetraparesis (GMFCS 5) and mild generalized dystonia, as well as dysphagia with G-tube dependence. Seizures were controlled on valproic acid and his dystonia was managed with trihexyphenidyl, with no prior history of status dystonicus. In the setting of weaning trihexyphenidyl for anticholinergic side-effects, the patient presented with a 4-week prodrome of increased dyskinesia (mostly chorea of the upper limbs, Video 1), followed by rapid deterioration to status dystonicus with prominent generalized dystonic posturing, inability to tolerate a seated position and fragmented sleep (dystonia severity scale (DSS) 5 =3), refractory to treatment with increasing doses of clonazepam (Figure 1). Initial examination showed generalized dystonic posturing, associated with tachycardia, diaphoresis, and distress (Video 2, DSS=4), and elevated serum creatine kinase levels to 2436U/L. Treatment with increasing doses of clonidine and diazepam was initiated. On day 5 of the admission, the patient’s dystonia worsened to a DSS of 5 with respiratory distress and increased CK-emia (5446U/L), necessitating escalation to treatment with intravenous infusions of dexmedetomidine and subsequently midazolam (Video 3). On day 7, the patient was intubated, and sedatives had to be escalated rapidly. Paralysis with vecuronium was initiated for 3 days due to refractory dystonic posturing and persistent CK-emia. Dystonia-targeted therapy was intensified with increasing doses of trihexyphenidyl (eventually limited by urinary retention), diazepam, tetrabenazine, clonidine and gabapentin (Figure 1). Despite aggressive medical therapy (dexmedetomidine 2mcg/kg/hr, midazolam 0.4mg/kg/hr in addition to bolus doses), the dystonia remained refractory. Brain MR imaging showed cerebral and cerebellar volume reduction consistent with UBA5-related disorder. Continuous video-EEG identified no seizures. GPi-DBS (Medtronic Percept™ PC) was placed on day 29 and stimulation was initiated the next day. Parameters were gradually increased. Under DBS (double unipolar configuration, left GPi: contact 0: 2.2mA, 1a: 0.8mA, 1b: 0.8mA, 1c: 0.8mA; right GPi: contact 8: 2.2mA, 9a: 0.8mA, 9b: 0.8mA, 9c: 0.8mA; pulse width of 60μs, frequency of 145Hz), rapid and sustained control of the patient’s dystonia was achieved, allowing de-escalation of treatment with stepwise discontinuation of intravenous infusions, tetrabenazine and a significant reduction in medication doses. At the time of discharge, the patient had no significant dystonia and only mild dyskinesia (Video 4) on a stable medication regimen and DBS settings (left GPi: contact 0: 2.2mA, 1a: 0.6mA, 1b: 0.6mA, 1c: 0.6mA; right GPi: contact 8: 2.2mA, 9a: 0.7mA, 9b: 0.7mA, 9c: 0.7mA; pulse width of 60μs, frequency 135Hz). He continued to gradually improve, was able to participate in physical and occupational therapy, tolerated seated positions, recovered sleep, and eventually fully returned to his previous baseline (DSS=1, Video 5).

Figure 1.

Clinical course shown as a timeline of medications, interventions, and level of care relative to dystonia severity scale (DSS) scores (left y-axis) and serum creatine kinase levels (right y-axis). The patient’s weight is 22.1kg. Abbreviations: BAC (baclofen), CLO (clonidine), CZP (clonazepam), DBS (deep brain stimulation), DEX (dexmedetomidine), GAB (gabapentin), GPi (globus pallidus internus), L (left), MDZ (midazolam), R (right), THP (trihexyphenidyl).

This case illustrates the challenges of managing status dystonicus in rare movement disorders and provides first evidence that status dystonicus in UBA5-related disorder may be responsive to GPi-DBS. Our report has limitations, including the relatively short follow up (4 months after DBS implantation) and unknown natural history of this ultra-rare disease. Although there is no general agreement on the optimal timing of DBS placement in the treatment of pediatric status dystonicus, our experience calls for early genetic testing and early consideration of DBS in the management of status dystonicus, particularly in the setting of monogenic hyperkinetic movement disorders.

Supplementary Material

Video 1: Nine days prior to presenting to the emergency room with status dystonicus, the patient presented to our outpatient clinic with a 4-week prodrome of increased dyskinesia, primarily consisting of chorea of the upper limbs, in addition to stereotyped bicycling movements of the lower limbs and orofacial dyskinesia. This presentation was consistent with a grade 3 on the dystonia severity scale.

Video 2: The patient presented to the emergency room with generalized dystonic posturing and upper limb chorea, associated with tachycardia, diaphoresis, and distress. Serum creatine kinase levels were elevated to 2436U/L. This presentation was consistent with a grade 4 on the dystonia severity scale.

Video 3: The patient was transferred to Intensive Care Unit for worsening dystonia, worsening rhabdomyolysis, and respiratory distress despite increases in clonidine and diazepam doses. He was subsequently intubated. This presentation was consistent with a grade 5 on the dystonia severity scale.

Video 4: At time of discharge, the patient had no significant dystonia. There were mild dyskinesia, stable on a medication regimen. This presentation was consistent with a grade 1 on the dystonia severity scale.

Video 5: About one month after discharge, the patient continues to have intermittent mild dyskinesia. He is rebuilding strength that he lost during his prolonged hospitalization. This presentation was consistent with a grade 1 on the dystonia severity scale.

Acknowledgements:

The authors thank the patient and his family for supporting this study.

Funding:

D.E.-F.’s research program received funding from the Tom Wahlig Foundation, the CureAP4 Foundation, the CureSPG50 Foundation, the Spastic Paraplegia Foundation, the Manton Center for Orphan Disease Research, the National Institute of Health / National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (1K08NS123552-01), and the Boston Children’s Hospital Office of Faculty Development.

Footnotes

Financial disclosures: None of the authors have any conflict of interest relevant to this study.

| Zainab Zaman | Employed by Boston Children’s Hospital. |

| Nadine Straka | Employed by Boston Children’s Hospital. |

| Anna L. Pinto | Employed by Boston Children’s Hospital. |

| Rasha Srouji | Employed by Boston Children’s Hospital. |

| Amy Tam | Employed by Boston Children’s Hospital. |

| Scellig Stone | Employed by Boston Children’s Hospital. |

| Monica Kleinman | Employed by Boston Children’s Hospital. |

| Weston T. Northam | Employed by Boston Children’s Hospital. |

| Darius Ebrahimi-Fakhari | Employed by Boston Children’s Hospital. Research grants: NIH/NINDS, CureAP4 Foundation, CureSPG50 Foundation, Spastic Paraplegia Foundation, Tom Wahlig Foundation, Manton Center for Orphan Disease Research, BCH Office of Faculty Development, BCH Translational Research Program. Joint research agreement: Astellas Pharmaceuticals Inc.. Royalties: Cambridge University Press. Speaker honoraria: Movement Disorders Society. Scientific advisory board (unpaid): CureAP4 Foundation, The Maddie Foundation, SPG69/Warburg Micro Research Foundation, Genetic Cures for Kids Inc., Lilly and Blair Foundation, The SPG15 Research Foundation. Local advisory committees (unpaid): BCH Gene Therapy Scientific Review Committee. International advisory committees (unpaid): Movement Disorders Society - Taskforce on the Nomenclature of Genetic Movement Disorders, Taskforce on Pediatric Movement Disorders |

Data Availability Statement:

The full data set is available from the corresponding author upon request.

References:

- 1.Artusi CA, Dwivedi A, Romagnolo A, Bortolani S, Marsili L, Imbalzano G, Sturchio A, Keeling EG, Zibetti M, Contarino MF, Fasano A, Tagliati M, Okun MS, Espay AJ, Lopiano L, Merola A. Differential response to pallidal deep brain stimulation among monogenic dystonias: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. Apr 2020;91(4):426–433. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2019-322169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Colin E, Daniel J, Ziegler A, et al. Biallelic Variants in UBA5 Reveal that Disruption of the UFM1 Cascade Can Result in Early-Onset Encephalopathy. Am J Hum Genet. Sep 1 2016;99(3):695–703. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.06.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Muona M, Ishimura R, Laari A, et al. Biallelic Variants in UBA5 Link Dysfunctional UFM1 Ubiquitin-like Modifier Pathway to Severe Infantile-Onset Encephalopathy. Am J Hum Genet. Sep 1 2016;99(3):683–694. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.06.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Briere LC, Walker MA, High FA, Cooper C, Rogers CA, Callahan CJ, Ishimura R, Ichimura Y, Caruso PA, Sharma N, Brokamp E, Koziura ME, Mohammad SS, Dale RC, Riley LG, Undiagnosed Diseases N, Phillips JA, Komatsu M, Sweetser DA. A description of novel variants and review of phenotypic spectrum in UBA5-related early epileptic encephalopathy. Cold Spring Harb Mol Case Stud. Jun 2021;7(3)doi: 10.1101/mcs.a005827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lumsden DE, King MD, Allen NM. Status dystonicus in childhood. Curr Opin Pediatr. Dec 2017;29(6):674–682. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0000000000000556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Video 1: Nine days prior to presenting to the emergency room with status dystonicus, the patient presented to our outpatient clinic with a 4-week prodrome of increased dyskinesia, primarily consisting of chorea of the upper limbs, in addition to stereotyped bicycling movements of the lower limbs and orofacial dyskinesia. This presentation was consistent with a grade 3 on the dystonia severity scale.

Video 2: The patient presented to the emergency room with generalized dystonic posturing and upper limb chorea, associated with tachycardia, diaphoresis, and distress. Serum creatine kinase levels were elevated to 2436U/L. This presentation was consistent with a grade 4 on the dystonia severity scale.

Video 3: The patient was transferred to Intensive Care Unit for worsening dystonia, worsening rhabdomyolysis, and respiratory distress despite increases in clonidine and diazepam doses. He was subsequently intubated. This presentation was consistent with a grade 5 on the dystonia severity scale.

Video 4: At time of discharge, the patient had no significant dystonia. There were mild dyskinesia, stable on a medication regimen. This presentation was consistent with a grade 1 on the dystonia severity scale.

Video 5: About one month after discharge, the patient continues to have intermittent mild dyskinesia. He is rebuilding strength that he lost during his prolonged hospitalization. This presentation was consistent with a grade 1 on the dystonia severity scale.

Data Availability Statement

The full data set is available from the corresponding author upon request.