Thyroid Eye Disease (TED) is a rare, potentially debilitating and disfiguring eye condition that typically coexists with autoimmune thyroid disease, and in particular, Graves’ Disease.1 TED studies have been conducted primarily in clinical cohorts or in homogenous populations, limiting generalizability of results across different populations.2-7 In a study of Graves’ orbitopathy incidence Bartley et al. reported a bimodal age distribution and higher rates in women in a population-based cohort of White residents of Olmstead County, Minnesota between 1976-1990, observations also supported by other studies.1-4 Smoking has been identified consistently as a risk factor for TED in a number of studies 6; ancestry (e.g., more common in Whites than Asian patients)6 and genetic factors7 have been raised as possible associated factors but need further investigation. With the recent availability of biologic treatment in 2020, an improved understanding of factors associated with TED and its course in different patient populations has become urgent to guide clinical management.

The IRIS® Registry (Intelligent Research in Sight) is a unique clinical database launched by the American Academy of Ophthalmology (Academy) that as of July 2022 includes data from electronic medical records (EMRs) on over 75 million unique patients from approximately 15,799 clinicians in ophthalmology practices in the US).8 The IRIS Registry provides an opportunity to study rare ophthalmic conditions with much broader scope than previously possible.5, 9, 10 This study leverages the IRIS Registry data to estimate TED prevalence and the frequency of its vision-threatening manifestations and evaluates associated factors (e.g., age, gender, ethnicity, smoking) overall in the large population of ophthalmology patients from practices across the United States included in the registry.

Methods

Data Source and Environment

The methods of data collection and aggregation of the IRIS Registry database have previously been described.11 Access to the IRIS Registry data was given to the selected academic centers as participants in IRIS Registry Analytic Center Consortium. The database used for these analyses was Rome (version 1), a version containing data through 2018. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Given the use of de-identified data, this project was exempted from Wills Eye Hospital Institutional Review Board review. The database was queried using SQL (PostgresSQL version 8.0.2), and all analyses were performed within the Amazon Web Services Virtual Private Cluster environment.

Study Population

All patients in the IRIS Registry (2013-2018) between 18-90 years of age as of last procedure or documented diagnosis were included in these analyses. The presence of TED was defined as having at least two visits to an ophthalmology practice coded with International Classification of Diseases, Ninth/Tenth Revision (ICD-9: 242.00, ICD-10: E05.00). Individuals not meeting these criteria were considered to be non-cases. Severity of TED was estimated by measuring frequency of vision-threatening manifestations (VTMs) (dysthyroid optic neuropathy (International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-9: 377; ICD-10: H47.01) and keratitis (ICD-9: 370; ICD-10: H16.8)) (Supplemental Table 1). Type I and Type II diabetes mellitus were defined using specified ICD-9/−10 codes on at least one visit (Supplemental Table 2).

Statistical Analysis

Prevalence was estimated (as a percent) overall and by: age groups (years) (18-29, 30-39, 40-49, 50-59, 60-69, 70+), gender (patients with unknown gender were excluded), race (Asian, White, Black/African-American, Other, Unknown), ethnicity (Hispanic, Not Hispanic, Unknown), geographic region (Midwest, Northeast, South, West, Unknown), Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus (yes or no), Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (yes or no), and smoking status (never, former, current, or unknown). Geographic region was defined based on the state of the practice where the patient was diagnosed, if the patient had TED, or the state of the practice where the patient’s last diagnosis or procedure took place, if the patient was never diagnosed with TED. These states were then assigned to a geographic region (Supplemental Table 3). If the practice did not have a state specified, that practice was classified as unknown geographic region. Smoking status was defined as the most commonly occurring status for each patient across all of their records. When a tie occurred for the most common status, the following hierarchy was used: current (top choice), former, never, unknown (last choice). In cases that were still ambiguous (a hierarchical algorithm was used that prioritized former smokers over never smoker, and never smokers over unknown status. Patients with missing data on smoking status (N = 6,804,017 (TED patients (n=2870) and patients without TED (n=6,801,147)) were excluded from the univariable and multivariable analyses for smoking status.

Characteristics of patients with and without TED were compared. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% Confidence Intervals (CIs) were estimated for prevalent TED using univariable and multivariable logistic regression to evaluate possible associated factors including age, gender, race, ethnicity, geographic region, Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus, Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus, and smoking status. Model fit was assessed using McFadden’s R2. Differences between characteristics of TED patients with and without vision-threatening manifestations were compared using χ2 tests; multivariable logistic regressions were also performed to evaluate factors associated with any vision-threatening manifestations (optic neuropathy or corneal microbial keratitis). All statistical analyses were performed using R Version 3.6.0, and statistical significance was defined as meeting a two-sided significance level of 0.05 (α=0.05).

Results

Prevalence by Demographics and Diabetes History

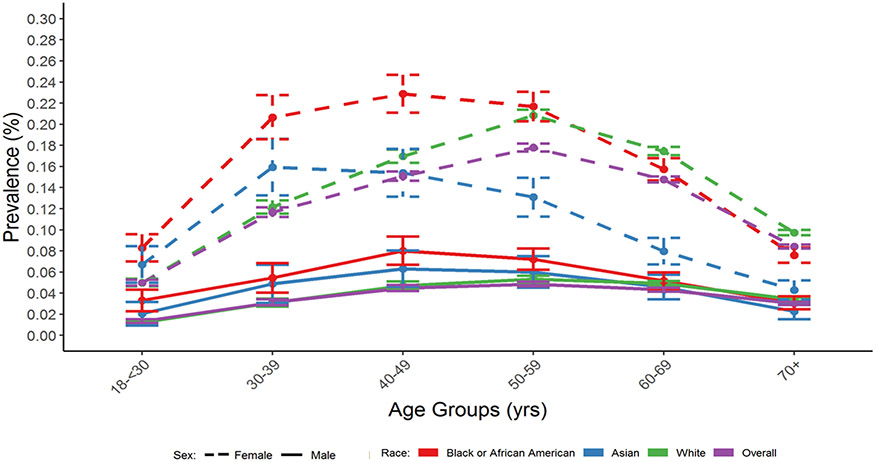

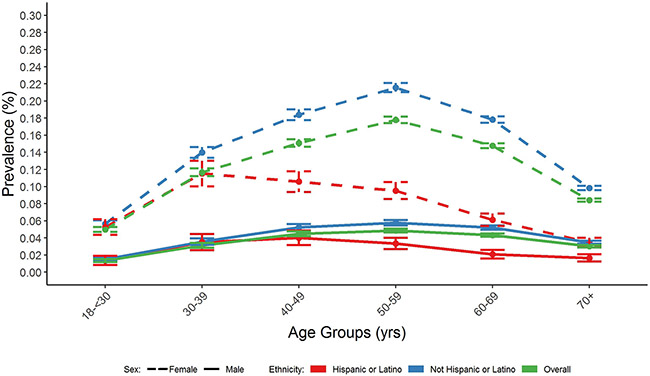

41,211 cases of TED documented at ≥2 visits were identified from 47,872,555 IRIS Registry patients, 18-90 years of age with visits between 2013 and 2018, resulting in an overall TED prevalence of 0.09%. Prevalence by age showed a unimodal distribution; was lowest in younger adults 18-30 years old (0.03%), peaked at 0.12% in middle-aged adults (50-54 years old), and decreased to 0.06% in patients ≥70 years of age (Table 1 and Figures 1 and 2). A 3-fold higher prevalence in females (0.12%) versus males (0.04%) was seen overall; the higher prevalence in females was seen across all age groups, race and ethnicity categories. Prevalence varied by race with the highest rates in Black/African American (0.12%) and White (0.11%) patients, and lowest in Asian patients (0.08%), and by ethnicity, being twice as high in non-Hispanic (0.10%) compared to Hispanic patients (0.05%) (Table 1). The unimodal age distribution was observed regardless of gender, race or ethnicity, though the peak prevalence age for TED was younger for Asian and Black/ African American patients than White patients and for Hispanic (ages 30-39 years) compared to non-Hispanic (ages 50-59 years) patients for both females and males (Figures 1 and 2). Current (0.16%) and former (0.11%) smokers had higher TED prevalence than never (0.08%) smokers (Table 1). Prevalence also varied by geographic region, with the highest frequency in the Midwest (0.12%) and similar prevalence in the other three regions, prevalence was higher in persons with Type 1 diabetes than without (0.15% vs 0.09%) and slightly lower in persons with Type 2 diabetes than without (0.07% vs 0.09%).

Table 1.

Prevalence of Thyroid Eye Disease in the IRIS® Registry by Demographic Characteristics, Diabetes History and Smoking Status (2013-2018).

| Characteristic | Total Patients Observed | Patients with TED | Percent Prevalence (SE) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | (%) | N | (%) | |||

| All Patients | 47,872,555 | (100) | 41,211 | (100) | 0.09 (0.0004) | |

| Age Group (years) | 18-<30 | 4,208,063 | (9) | 1,441 | (3) | 0.03 (0.0009) |

| 30–39 | 3,694,074 | (8) | 2,997 | (7) | 0.08 (0.0015) | |

| 40–49 | 5,117,054 | (11) | 5,403 | (13) | 0.11 (0.0014) | |

| 50–59 | 8,254,130 | (17) | 10,138 | (25) | 0.12 (0.0012) | |

| 60–69 | 11,648,079 | (24) | 12,076 | (29) | 0.10 (0.0009) | |

| 70+ | 14,951,155 | (31) | 9,156 | (22) | 0.06 (0.0006) | |

| Gender | Male | 20,308,218 | (42) | 7,450 | (18) | 0.04 (0.0004) |

| Female | 27,564,337 | (58) | 33,761 | (82) | 0.12 (0.0007) | |

| Race | White | 30,872,279 | (64) | 30,039 | (73) | 0.10 (0.0006) |

| Asian | 1,409,598 | (3) | 1,050 | (3) | 0.07 (0.0023) | |

| Black/African American | 3,483,498 | (7) | 4,053 | (10) | 0.12 (0.0018) | |

| Other | 491,334 | (1) | 464 | (1) | 0.09 (0.0044) | |

| Unknown | 11,615,846 | (24) | 5,605 | (14) | 0.05 (0.0006) | |

| Ethnicity | Not Hispanic | 31,446,783 | (66) | 32,267 | (78) | 0.10 (0.0006) |

| Hispanic | 3,579,022 | (7) | 1,849 | (4) | 0.05 (0.0012) | |

| Unknown | 12,846,750 | (27) | 7,095 | (17) | 0.06 (0.0007) | |

| Geographic Region | South | 13,558,130 | (28) | 10,411 | (25) | 0.08 (0.0008) |

| Midwest | 7,375,548 | (15) | 8,516 | (21) | 0.12 (0.0013) | |

| Northeast | 7,547,243 | (16) | 6,677 | (16) | 0.09 (0.0011) | |

| West | 7,257,295 | (15) | 5,532 | (13) | 0.08 (0.0010) | |

| Unknown | 12,134,339 | (25) | 10,075 | (24) | 0.08 (0.0008) | |

| Type I Diabetes Mellitus | No | 47,046,174 | (98) | 39,998 | (97) | 0.09 (0.0004) |

| Yes | 826,381 | (2) | 1,213 | (3) | 0.15 (0.0042) | |

| Type II Diabetes Mellitus | No | 39,082,325 | (82) | 34,851 | (85) | 0.09 (0.0005) |

| Yes | 8,790,230 | (18) | 6,360 | (15) | 0.07 (0.0009) | |

| Smoking Status | Never | 27,915,653 | (58) | 21,220 | (51) | 0.08 (0.0005) |

| Former | 8,475,587 | (18) | 9,523 | (23) | 0.11 (0.0012) | |

| Current | 4,677,298 | (10) | 7,598 | (18) | 0.16 (0.0019) | |

| Unknown | 6,804,017 | (14) | 2,870 | (7) | 0.04 (0.0008) | |

Abbreviations: TED = Thyroid Eye Disease; SE = Standard Error; IRIS = Intelligent Research in Sight.

Figure 1.

Prevalence (with 95% CIs) of Thyroid Eye Disease Among AAO IRIS® Registry Patients by Race, Gender, and Age Group (2013-2018).

Abbreviations: CI = Confidence Interval; AAO = American Academy of Ophthalmology; IRIS = Intelligent Research in Sight; yrs = years; ICD = International Classification of Diseases.

TED was defined as having ≥2 visits to an ophthalmologist coded with the following ICD codes: ICD-9: 242.00; ICD-10: E05.00.

Figure 2.

Prevalence (with 95% CIs) of Thyroid Eye Disease Among AAO IRIS® Registry Patients by Ethnicity, Gender, and Age Group (2013-2018).

Associated Factors

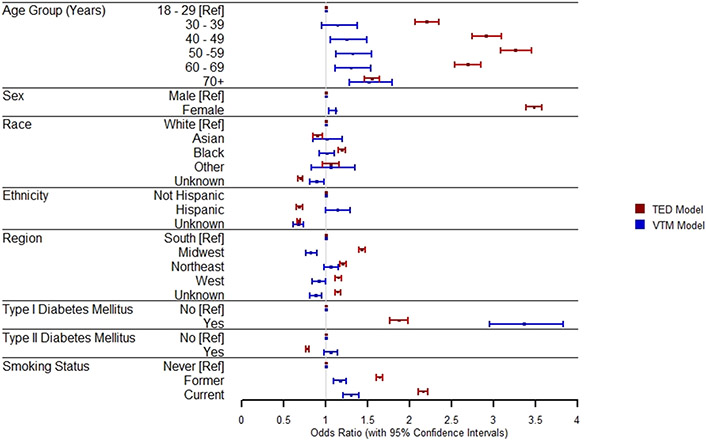

Age, gender, race, ethnicity, geographic region, Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes, and smoking status were independently associated with TED in a multivariable model including all factors as covariates (Table 2, Figure 3). Compared to younger patients (18-30 year olds), the adjusted odds ratio (OR (95% CI)) of having TED increased in patients from 30-39 years to 40-49 years old, peaked at 50-59 years (OR: 3.26 (3.08, 3.45) and then decreased in older ages to 1.55 (1.46, 1.64) in patients 70 years and older (all p values <0.0001) (Table 2). Females were 3.5 times more likely to have TED than males (OR: 3.48 (3.39, 3.57); p<0.0001)). Compared to White patients, Black/African American patients were more likely to have TED (OR: 1.19 (1.15, 1.23); p <0.0001), and Asian patients less likely (OR: 0.9 (0.85, 0.96); p=0.002). TED was also less likely to be diagnosed in Hispanic patients compared to non-Hispanic patients (OR: 0.68 (0.65, 0.72); p <0.0001).

Table 2.

TED and Associated Factors Among IRIS® Registry Patients (2013-2018): Univariable and Multivariable Logistic Regression Analyses

| Univariable | Multivariable* | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | TED Patients | Patients without TED | OR | 95% CI | P-Value | OR | 95% CI | P-Value | |||

| N | (%) | N | (%) | ||||||||

| All Patients | 42,211 | (100) | 47,831,344 | (100) | |||||||

| Age Group (years) | 18-<30 | 1,441 | (3) | 4,206,622 | (9) | [Ref] | [Ref] | ||||

| 30-39 | 2,997 | (7) | 3,691,077 | (8) | 2.37 | (2.23, 2.52) | < 0.0001 | 2.20 | (2.06, 2.35) | < 0.0001 | |

| 40-49 | 5,403 | (13) | 5,111,651 | (11) | 3.09 | (2.91, 3.27) | < 0.0001 | 2.91 | (2.74, 3.09) | < 0.0001 | |

| 50-59 | 10,138 | (25) | 8,243,992 | (17) | 3.59 | (3.40, 3.79) | < 0.0001 | 3.26 | (3.08, 3.45) | < 0.0001 | |

| 60-69 | 12,076 | (29) | 11,636,003 | (24) | 3.03 | (2.87, 3.20) | < 0.0001 | 2.69 | (2.54, 2.85) | < 0.0001 | |

| 70+ | 9,156 | (22) | 14,941,999 | (31) | 1.79 | (1.69, 1.89) | < 0.0001 | 1.55 | (1.46, 1.64) | < 0.0001 | |

| Gender | Male | 7,450 | (18) | 20,300,768 | (42) | [Ref] | [Ref] | ||||

| Female | 33,761 | (82) | 27,530,576 | (58) | 3.34 | (3.26, 3.43) | < 0.0001 | 3.48 | (3.39, 3.57) | < 0.0001 | |

| Race | White | 30,039 | (73) | 30,842,240 | (64) | [Ref] | [Ref] | ||||

| Asian | 1,050 | (3) | 1,408,548 | (3) | 0.77 | (0.72, 0.81) | < 0.0001 | 0.90 | (0.85, 0.96) | 0.002 | |

| Black or African American | 4,053 | (10) | 3,479,445 | (7) | 1.20 | (1.16, 1.24) | < 0.0001 | 1.19 | (1.15, 1.23) | < 0.0001 | |

| Other | 464 | (1) | 490,870 | (1) | 0.97 | (0.89, 1.06) | 0.52 | 1.06 | (0.96, 1.16) | 0.26 | |

| Unknown | 5,605 | (14) | 11,610,241 | (24) | 0.50 | (0.48, 0.51) | < 0.0001 | 0.70 | (0.67, 0.72) | < 0.0001 | |

| Ethnicity | Not Hispanic | 32,267 | (78) | 31,414,516 | (66) | [Ref] | [Ref] | ||||

| Hispanic | 1,849 | (4) | 3,577,173 | (7) | 0.50 | (0.48, 0.53) | < 0.0001 | 0.68 | (0.65, 0.72) | < 0.0001 | |

| Unknown | 7,095 | (17) | 12,839,655 | (27) | 0.54 | (0.52, 0.55) | < 0.0001 | 0.68 | (0.66, 0.70) | < 0.0001 | |

| Geographic Region | South | 10,411 | (25) | 13,547,719 | (28) | [Ref] | [Ref] | ||||

| Midwest | 8,516 | (21) | 7,367,032 | (15) | 1.50 | (1.46, 1.55) | < 0.0001 | 1.43 | (1.39, 1.47) | < 0.0001 | |

| Northeast | 6,677 | (16) | 7,540,566 | (16) | 1.15 | (1.12, 1.19) | < 0.0001 | 1.20 | (1.17, 1.24) | < 0.0001 | |

| West | 5,532 | (13) | 7,251,763 | (15) | 0.99 | (0.96, 1.03) | 0.66 | 1.15 | (1.11, 1.19) | < 0.0001 | |

| Unknown | 10,075 | (24) | 12,124,264 | (25) | 1.08 | (1.05, 1.11) | < 0.0001 | 1.14 | (1.11, 1.18) | < 0.0001 | |

| Type I Diabetes Mellitus | No | 39,998 | (97) | 47,006,176 | (98) | [Ref] | [Ref] | ||||

| Yes | 1,213 | (3) | 825,168 | (2) | 1.73 | (1.63, 1.83) | < 0.0001 | 1.87 | (1.76, 1.98) | < 0.0001 | |

| Type II Diabetes Mellitus | No | 34,851 | (85) | 39,047,474 | (82) | [Ref] | [Ref] | ||||

| Yes | 6,360 | (15) | 8,783,870 | (18) | 0.81 | (0.79, 0.83) | < 0.0001 | 0.78 | (0.76, 0.8) | < 0.0001 | |

| Smoking Status | No | 21,220 | (51) | 27,894,433 | (58) | [Ref] | [Ref] | ||||

| Former | 9,523 | (23) | 8,466,064 | (18) | 1.48 | (1.44, 1.51) | < 0.0001 | 1.64 | (1.6, 1.68) | < 0.0001 | |

| Current | 7,598 | (18) | 4,669,700 | (10) | 2.14 | (2.08, 2.20) | < 0.0001 | 2.16 | (2.1, 2.22) | < 0.0001 | |

Abbreviations: TED = Thyroid Eye Disease; OR = Odds Ratio; CI = Confidence Interval; IRIS = Intelligent Research in Sight; Ref = Reference.

Multivariable logistic regression model contained all of the above factors (age group, gender, geographic region, race, ethnicity, smoking status, Type I diabetes, Type II diabetes). Patients with unknown smoking status were excluded from the analyses (TED Patients (N=2870); Patients w/o TED (N=6,801,147). Bolded variables represent statistical significance (p<0.05).

Figure 3.

Forest Plot of the Adjusted Odds Ratios* of Factors and Their Associations with TED Among IRIS® Registry Patients (N = 47,872,555), and the Adjusted Odds Ratios of Associated Factors and vision-threatening manifestations among TED Patients (N = 41,211) (2013-2018).

Abbreviations: IRIS = Intelligent Research in Sight; CI = Confidence Interval; Ref = Reference; TED = Thyroid Eye Disease; ICD = International Classification of Diseases

* Adjusted Odds Ratio presented derived from a multivariable logistic regression model containing all other above risk factors.

TED diagnosis varied by geographic region, with the highest odds seen with practices in the Midwest compared to the South (OR: 1.4 (1.39, 1.47); p <0.0001), was positively associated with Type 1 diabetes (OR: 1.87 (1.76, 1.98); p <0.0001) and inversely associated with Type 2 diabetes (OR: 0.78 (0.76, 0.8); p <0.0001). TED was also positively associated with former smoking (OR: 1.64 (1.6, 1.68); p <0.0001) and current smoking (OR: 2.1 (2.1, 2.2); p <0.0001) compared to non-smoking, showing a dose-response pattern.

Vision-Threatening Manifestations

Additional analyses focused on those patients with the TED-associated VTMs of dysthyroid optic neuropathy and corneal disease. Eighteen percent (7,551/41,211) of TED patients in our cohort had VTMs, with the majority (71%) attributed to keratitis. (Table 3).

Table 3.

Distribution of Vision-Threatening Manifestations and Surgical Procedures among TED Patients in the IRIS® Registry (2013-2018).

| N | (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Total TED Patients | 41,211 | (100) |

| TED Patients with ≥ 1 VTM | 7,551 | (18) |

| Optic Neuropathy (ON) only | 1,455 | (4) |

| Corneal Keratitis (CMK) only | 5,364 | (13) |

| ON and CMK | 732 | (2) |

Abbreviations: VTM = Vision-Threatening Manifestations; TED = Thyroid Eye Disease; IRIS = Intelligent Research in Sight.

Patients with TED-associated VTMs were more likely to be female, have Type 1 diabetes, and be current or former smokers based on multivariable analyses, findings similar to those observed in all TED patients (Table 4). Unlike the full TED cohort, VTMs tended to increase increasing age with the highest odds in the oldest age group 70+ years (vs 18-30 years) (OR: 1.5 (1.28, 1.79)) (Table 4). In addition, while VTMs were associated with Hispanic ethnicity (OR: 1.14 (1.00, 1.29)), no associations with race were observed.

Table 4.

TED Patients with and without Vision-Threatening Manifestations by demographic characteristics, Diabetes and Smoking history

| Univariable | Multivariable§ | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | TED Patients without VTM |

TED Patients with VTM |

P value | OR | 95% CI | P-Value | OR | 95% CI | P-Value | |||

| N | (%) | N | (%) | |||||||||

| All Patients | 33,660 | (100) | 7,551 | (18) | ||||||||

| Age Group (years) | 18-<30 | 1,234 | (4) | 207 | (3) | < 0.0001 | [Ref] | |||||

| 30-39 | 2,521 | (7) | 476 | (6) | 1.16 | (0.97, 1.40) | 0.11 | 1.14 | (0.95, 1.38) | 0.16 | ||

| 40-49 | 4,487 | (13) | 916 | (12) | 1.28 | (1.08, 1.52) | 0.005 | 1.25 | (1.05, 1.49) | 0.01 | ||

| 50-59 | 8,293 | (25) | 1,845 | (24) | 1.37 | (1.17, 1.62) | 0.0001 | 1.32 | (1.12, 1.55) | 0.001 | ||

| 60-69 | 9,865 | (29) | 2,211 | (29) | 1.38 | (1.17, 1.62) | 0.0001 | 1.30 | (1.11, 1.54) | 0.002 | ||

| 70+ | 7,260 | (22) | 1,896 | (25) | 1.61 | (1.37, 1.90) | <0.0001 | 1.51 | (1.28, 1.79) | < 0.0001 | ||

| Gender | Male | 6,129 | (18) | 1,321 | (17) | 0.15 | [Ref] | |||||

| Female | 27,531 | (82) | 6,230 | (83) | 1.03 | (0.97, 1.11) | 0.27 | 1.12 | (1.04, 1.20) | 0.002 | ||

| Race | White | 24,344 | (72) | 5,695 | (75) | < 0.0001 | [Ref] | |||||

| Asian | 872 | (3) | 178 | (2) | 0.88 | (0.74, 1.03) | 0.12 | 1.01 | (0.85, 1.20) | 0.92 | ||

| Black or African American | 3,288 | (10) | 765 | (10) | 0.97 | (0.89, 1.05) | 0.44 | 1.01 | (0.92, 1.10) | 0.84 | ||

| Other | 373 | (1) | 91 | (1) | 1.02 | (0.81, 1.30) | 0.86 | 1.06 | (0.83, 1.35) | 0.63 | ||

| Unknown | 4,783 | (14) | 822 | (11) | ** | 0.72 | (0.66, 0.79) | <0.0001 | 0.89 | (0.81, 0.98) | 0.02 | |

| Ethnicity | Not Hispanic | 25,999 | (77) | 6,268 | (83) | < 0.0001 | [Ref] | |||||

| Hispanic | 1,488 | (4) | 361 | (5) | 1.01 | (0.90, 1.15) | 0.81 | 1.14 | (1.00, 1.29) | 0.05 | ||

| Unknown | 6,173 | (18) | 922 | (12) | ** | 0.61 | (0.57, 0.66) | <0.0001 | 0.67 | (0.61, 0.73) | < 0.0001 | |

| Geographic Region | South | 8,364 | (25) | 2,047 | (27) | < 0.0001 | [Ref] | |||||

| Midwest | 7,012 | (21) | 1,504 | (20) | 0.88 | (0.81, 0.95) | 0.001 | 0.82 | (0.76, 0.89) | < 0.0001 | ||

| Northeast | 5,358 | (16) | 1,319 | (17) | 0.99 | (0.92, 1.08) | 0.89 | 1.06 | (0.98, 1.15) | 0.18 | ||

| West | 4,556 | (14) | 976 | (13) | 0.86 | (0.79, 0.94) | 0.001 | 0.92 | (0.84, 1.00) | 0.06 | ||

| Unknown | 8,370 | (25) | 1,705 | (23) | ** | 0.82 | (0.76, 0.88) | <0.0001 | 0.88 | (0.81, 0.95) | 0.0006 | |

| Type I Diabetes Mellitus | No | 32,966 | (98) | 7,032 | (93) | < 0.0001 | [Ref] | |||||

| Yes | 694 | (2) | 519 | (7) | 3.59 | (3.19, 4.05) | <0.0001 | 3.36 | (2.95, 3.83) | < 0.0001 | ||

| Type II Diabetes Mellitus | No | 28,754 | (85) | 6,097 | (81) | < 0.0001 | [Ref] | |||||

| Yes | 4,906 | (15) | 1,454 | (19) | 1.39 | (1.30, 1.49) | <0.0001 | 1.06 | (0.98, 1.14) | 0.12 | ||

| Smoking Status | Never | 17,616 | (52) | 3,604 | (48) | < 0.0001 | [Ref] | |||||

| Former | 7,628 | (23) | 1,895 | (25) | 1.21 | (1.14, 1.29) | <0.0001 | 1.17 | (1.09, 1.24) | < 0.0001 | ||

| Current | 5,942 | (18) | 1,656 | (22) | 1.36 | (1.28, 1.45) | <0.0001 | 1.30 | (1.21, 1.39) | < 0.0001 | ||

Abbreviations: TED = Thyroid Eye Disease; VTM = Vision Threatening Manifestation; CI = Confidence Interval; Ref = Reference.

Unless otherwise noted, p-value of the association between each factor and VTM was derived using the Chi-Square test of association.

Category not included as part of the statistical test.

Multivariable logistic regression model contained all of the above factors (age group, gender, geographic region, race, ethnicity, smoking status, type I diabetes, type II diabetes). Patients with unknown smoking status were excluded from the analyses (TED Patients w/o VTMs (N=2474); Patients with VTMs (N=396). Bold values indicate statistically significant results (p<0.05).

Discussion

Overview

Leveraging the large, geographically and ethnically diverse IRIS Registry dataset, this study represents the largest and broadest epidemiological description of prevalence and associated factors for adult TED and TED severity in a national clinical registry, to our knowledge. Our study identified several novel observations including a unimodal, rather than bimodal age distribution for TED prevalence and significant variations in TED prevalence and peak age prevalence by race and ethnicity discussed in detail below. TED prevalence was highest in Black/African American patients, a finding not previously reported to our knowledge, and lowest in Asian and Hispanic patients with younger ages of peak prevalence in Black/African American, Asian and Hispanic patients compared to Whites. The higher TED prevalence rates in females, smokers and persons with Type 1 diabetes tie together observations from prior studies based on smaller, clinically based homogenous groups of patients, and support the generalizability of the IRIS Registry data for such investigations.

TED Prevalence

Demographic Characteristics

Using a conservative definition for TED requiring diagnosis at a minimum of two visits, the observed TED prevalence of 0.09% with a 3:1 ratio of females to males (0.12% prevalence in females and 0.04% prevalence in males) in the IRIS Registry is consistent with prior estimates of 0.08 – 0.16 % in females and 0.009 – 0.029% in males.4, 6, 12-14 This 3-fold-higher prevalence in women is consistent with studies of TED patients across multiple geographic locations including Europe4 and Asia,15, 16 and in patients with Graves’ and other autoimmune diseases.17 The unimodal age distribution of TED observed in the IRIS registry irrespective of gender, race, or ethnicity, differed from Bartley et al.’s 25 year incidence study describing a bimodal age distribution for Graves’ ophthalmopathy.14

Bartley et al.’s classic report14 in the relatively homogenous population of Olmstead County, Minnesota, provides the best available comparison with IRIS Registry prevalence data. Their study described a bimodal age distribution of TED with one peak age of incidence in the 40s and the second peak age in the 60s, as well as a roughly five-fold increased incidence in women. Men tended to develop TED about five years later than women in their cohort. In contrast, in the IRIS Registry, the TED peak age of prevalence was 50-59 years for both men and women (Figure 1). While the different patterns in age distributions between studies may be explained by differences in study design, definition of TED, patient sampling and sample size, the fact that the unimodal age distribution was observed across all gender and race/ethnicity subgroups in the IRIS Registry lends support to the validity of this single peak distribution.

TED prevalence was associated with race, ethnicity, and geographic region in our cohort. Our findings regarding higher TED prevalence in Black/African American patients and lower rates in Hispanic patients are new observations, though consistent with reported variation in TED prevalence in different ethnic groups in other populations studied,4, 7 even when controlling for smoking and other risk factors. Specifically, prevalence of TED has been reported to be lower in Asians compared to Whites6 and comparable within different European subgroups12; however, very limited data are available for Black/African Americans or others of African descent. In countries with multiple highly-represented ethnic groups, such as Malaysia,18 prevalence also varied among the different ethnicity subsets, suggesting that ethnicity may be more important than pure geography in the pathogenesis of TED. A further indication of a role for ethnic variation in TED is the distinct and growing body of evidence suggesting that in India,19 TED prevalence is similar in females and males, unlike the female preponderance seen in our study and others. Finally, the younger age of peak prevalence observed in the IRIS Registry in Asian and Hispanic patients is consistent with reports that identify a much younger mean age of diagnosis in Asian patients18, 20 in 30s and 40s20, 21 compared to White14 or African22 patients. Improved understanding of the basis for these different patterns will advance understanding of causes and management of TED in a range of patients.

Direct comparison of these prior studies with the IRIS Registry data is limited as each study is a single-center analysis of a small cohort with limited geographic diversity and generally a homogeneous population. For example, while in the Mayo Clinic study all 120 patients were White14. the IRIS Registry cohort includes over 40,000 racially and ethnically diverse patients with TED across the United States; the ability to analyze racial and ethnic variation in a single data set with a large sample size is a unique advantage of the IRIS Registry and provides strong support to tie the results of these single-center analyses together into a coherent whole.

There may be several explanations for our observation of increased prevalence in Black/African-American patients and decreased prevalence in Asian and Hispanic patients. Underlying thyroid disease state may be different in these subgroups, which is not distinguished by ICD-9/ICD-10 coding. Orbital anatomy and exophthalmometry does vary among races with Black/African Americans23 and Asians24 both having shallower orbits and higher proptosis measurements. However, ethnic variation in osteology cannot explain why Black/African Americans have a higher TED prevalence and Asians have a lower prevalence, suggesting that pure anatomy does not fully explain these differences. Specifically, the genetics of TED has been studied and loci such as human leukocyte antigen (HLA), cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4), tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα), and the thyroid stimulating hormone receptor (TSH-R) all display allelic variation that may be responsible for the observed racial/ethnic variation.25 Hispanics in particular share genetic polymorphisms with Asians,26 which may account for the observed decreased prevalence in Hispanics and Asians. Diet and nutrition can also be contributing factors to the observed geographic and racial/ethnic variation. For example, while selenium has been long described as a vital trace element in the anti-inflammatory response and TED specifically,27 there are numerous elements derived from drinking water, soil, and food that could potentially be implicated,28 including cobalt and cesium. Vitamin D levels are both nutritionally and environmentally dependent and have been shown to be significantly lower in patients with Graves’ and TED.29 Environmental pollutants unique to geographic location, confounding genetic factors, and different patterns in TED diagnosis and treatment by physicians could also play a role in this observed finding. Inquiry into possible roles of genetics, the microbiome, and environmental exposures could further elucidate the underlying reasons for these phenomena. Variation in prevalence by geographic region in the US based on practice location was also observed, with the highest observed rate present in the Midwest; however, the reasons for this observation are unclear. The significant variation in prevalence of TED by gender, race and ethnicity in the IRIS Registry suggests the importance of considering racial, ethnic, and geographic heterogeneity in the interpretation of prior studies with more homogenous populations.

Other Associated Factors

Our study lends further support to smoking as an independent risk factor for TED. The increased risk of TED due to smoking has long been established,6, 30 and smoking is known to be associated with more severe manifestations of disease31 and resistance to treatment.32 Smoking has been found to be associated with TED in multiple racial and ethnic groups including Africans,22 Europeans,6 and North Americans33 and is present across racial and ethnic groups in the IRIS Registry cohort. This is surmised to be due to increased oxidative stress and fibroblast proliferation with subsequent recruitment of the inflammatory response and production of glycosaminoglycans leading to the clinical manifestations of TED.34 Ours is the largest study to find cigarette smoking as an independent risk factor for TED controlling for age, gender, and ethnicity and provides further authority for smoking cessation counseling for dysthyroid patients.

Finally, we noted that Type 1 diabetes was a risk factor for TED, a finding consistent with the literature.35 This observed association of Type 1 diabetes and TED is consistent with prior reports5, 35 and may be explained by both conditions being T-cell mediated autoimmune diseases. Furthermore, interplay between the insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) receptor on the orbital fibroblast and upregulated serum IGF-1 levels in patients with diabetes or insulin resistance37 could contribute to this finding. The slightly protective effect of Type 2 diabetes on TED differs from prior work that predominantly shows no association between Type 2 diabetes and prevalence of TED.5, 35 One possible explanation is that patients with Type 2 diabetes may be overrepresented in the IRIS Registry by twofold36 compared to the normal population, as patients are routinely evaluated by ophthalmologists for diabetic retinopathy, leading to a possible spurious result. Nevertheless, further investigations are necessary to fully elucidate the relationship of diabetes and thyroid eye disease.

Vision-Threatening Manifestations among TED patients

In this large national database, VTMs were seen in 18% of TED patients, with 13% of TED patients exhibiting keratitis and 4% experiencing optic neuropathy (Table 3). TED patients with VTMs overall tended to be older, female, more likely to have Type 1 diabetes, and to be current or former smokers.

The observed associations of VTMs with older age (>70 years) and female sex are consistent with previous reports in which severe TED was associated with progressive age. Older patients exhibited more diplopia and vision loss38, optic neuropathy39, and overall inflammation and morbidity,4, 40 a pattern that has been previously reported41 and can manifest as a protracted, fibrotic disease course.39 The strong relationship between Type 1 Diabetes and VTMs (OR 3.36) in the IRIS Registry database is consistent with reported associations of diabetes with optic neuropathy and keratitis, independent of TED5 lending credibility to our finding. Finally, the association of VTMs with former and current smoking compared to non-smokers observed in the IRIS Registry is also consistent with prior studies. Current smokers had the highest risk of VTMs (OR 1.3), followed by former smokers (OR 1.17) (Table 4). This dose-response relationship in severe TED has been widely reported in the literature6, 30-33 and demonstrates that smokers are at higher risk not only for developing TED, but also for developing severe TED. This association appears to be also directly correlated with the number of cigarettes smoked in other studies, as former smokers are still at risk, but less so compared to current smokers.42 These data provide further support to rigorous smoking cessation counseling for patients with TED.

Strengths and Limitations

Our study has a number of limitations. First, TED diagnosis is based on ICD diagnosis codes provided by physicians to the EMR. Coding errors and inconsistencies can lead to misclassification of TED cases and non-cases, resulting in false positives and false negatives in in a large database. For example, patients who are referred for evaluation for TED, whilst not actually having the disease, may be classified with the same TED ICD-9/ICD-10 codes. We attempted to minimize the likelihood of these biases by including only patients who had at least two visits to an ophthalmologist with the required ICD codes, as patients truly without TED would not likely be coded as having the disease on multiple visits. However, this more restrictive definition of TED may also have led to exclusion of TED patients with mild disease who were only seen once by an ophthalmologist or may not have had overt eyelid retraction, proptosis or inflammation and were not diagnosed with TED. This misclassification of patients with TED as non-TED cases would result in an underestimate of the disease prevalence, and also depending on the degree of misclassification, limiting our ability to detect between-group differences.

TED cases may have been missed for various other reasons. Coding based on ICD-9/ICD-10 classification for TED tends to selectively include patients with Graves’-related hyperthyroidism as an underlying diagnosis. As such, our definition of a TED case may potentially exclude patients with Hashimoto’s or euthyroid orbitopathy, resulting in an underestimate of the prevalence and potential biases in the resulting associations. In fact, the IRIS registry does not include data on underlying thyroid state so we do not know the nature of the underlying autoimmune thyroid disorder. However, in the United States, the underlying thyroid diagnosis for majority of TED patients is Graves’ disease43, minimizing the potential impact of this limitation on the interpretation of our findings. The conclusions are also drawn from a population comprised of adult patients who were treated by an eye care provider in the United States. This excludes patients who are treated for TED only by an endocrinologist, neurology-trained neuro-ophthalmologist who would not participate in the IRIS Registry, or a physician outside the United States.

In addition, the definition of severe disease is also based on surrogate markers for disease activity including the presence of coding for optic neuropathy and keratitis, potentially resulting in an underestimate of these patients. On the other hand, the majority of patients identified with VTMs had keratitis which is typically mild in nature, overestimating the prevalence of true VTMs. When we attempted to classify patients with microbial vs exposure keratitis, few patients were coded with this level of specificity and it was not possible to distinguish between keratitis categories in a meaningful way. However, in our experience, keratitis is not typically selected as a diagnosis code unless findings are significant enough to impair visual function in some way Therefore, while our definition of severe disease is not as sensitive, it is specific as clinicians are not likely to code for these additional and rare findings unless present.

As the IRIS Registry is generalized for ophthalmology and not oculofacial plastic surgery, specific factors of interest are not available, including measurements for proptosis, eyelid retraction, or strabismus. The rate of ICD coding for strabismus in our population was much lower than the expected 50% usually observed in TED patients, suggesting that these data were unreliable. We also investigated CPT codes for strabismus surgery, but recognized that this measure excluded many patients who have strabismus but do not undergo surgery for it. We were also unable to evaluate underlying thyroid state, serum antibody levels, antithyroid therapy given (i.e., thyroidectomy, radioactive iodine, or medical treatment), or disease progression over time. Data on demographic characteristics, smoking status and diabetes are also subject to the inherent limitations of electronic medical record data which may be incomplete or inaccurate and should be considered in the interpretation of the study findings. Estimates from the logistic regression model are known to have bias for rare events, a point to consider when interpreting the study results. The alternative methods (e.g. penalized likelihood approach) originally developed to reduce potential bias for rare events yielded similar results to those based on logistic regression. Future research is needed to develop approaches with better parameter estimates and model fits under large data settings (such as the IRIS Registry).

Despite these limitations that are characteristic of big data studies based on EMR data, a number of our findings are largely consistent with prior studies, supporting their validity as well as the validity of our new observations of a unimodal age distribution and race and age-based variation. The large sample size and geographic, ethnic, and racial heterogeneity present in the IRIS Registry is more representative of patients seen in clinical practice in the United States today and may improve the general applicability of these findings to TED patients seen in ophthalmology practices across the United States. Future research can build upon these new observations by prospectively and rigorously studying TED phenotypes to investigate genetic, clinical, environmental, and other factors that may influence the course of the disease in the different subgroups. Related translational research can focus on identifying genomic or metabolic variance to further understand the pathophysiology of TED. Specifically, identifying the molecular basis underlying age, gender, and racial/ethnic variation would be of great utility in diagnosing and treating TED patients.

Conclusions

This is the largest study to date that has evaluated TED prevalence and associated factors within a large national clinical registry. Novel findings include a unimodal age distribution, ethnic variation with higher prevalence in Black/African American patients and lower prevalence in Asian and Hispanic patients, and younger ages of peak prevalence for Asian, Hispanic and Black/African American patients. These finding offer new avenues for research to better understand TED. The observations regarding higher prevalence with female sex and smoking, and more severe disease in older ages and patients with Type 1 diabetes lend further support to prior reports. This epidemiologic profile of TED in the United States can help physicians in the counseling and management of patients who present with autoimmune thyroid disease and raises novel questions about the underlying pathogenesis of TED in different populations that are worthy of future investigation.

Supplementary Material

Financial Support:

PNC Charitable Trust Newell Delvalpine Foundation, Baltimore MD and the William and Ella Owens Medical Research Foundation, San Antonio TX.

The sponsor or funding organizations had no role in the design or conduct of this research.

Abbreviations:

- TED

Thyroid Eye Disease

- VTM

vision-threatening manifestation

- IRIS Registry

Intelligent Research in Sight

- EMR

electronic medical record

- OR

odds ratio

- CI

confidence intervals

- ICD-9

International Classification of Diseases Ninth revision

- ICD-10

International Classifications of Diseases Tenth revision

Footnotes

Meeting Presentation: Previously presented at The Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology (ARVO) Annual Meeting, 2020

Conflict of Interest: Aaron Lee reports grants from Santen, Regeneron, Carl Zeiss Meditec, and Novartis, and personal fees from Genentech, Roche, and Johnson and Johnson, outside of the submitted work. Sathyadeepak Ramesh receives speaking fees from Horizon Therapeutics. The sponsor or funding organizations had no role in the design or conduct of this research.

References

- 1.Bartley GB, Fatourechi V, Kadrmas EF, Jacobsen SJ, Ilstrup DM, Garrity JA, Gorman CA. The chronology of Graves’ ophthalmopathy in an incidence cohort. Am J Ophthalmol. 1996;121:426–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bartley GB. The epidemiologic characteristics and clinical course of ophthalmopathy associated with autoimmune thyroid disease in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1994;92:477–588. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bartley GB, Fatourechi V, Kadrmas EF, Jacobsen SJ, Ilstrup DM, Garrity JA, Gorman CA. Clinical Features of Graves’ Ophthalmopathy in an Incidence Cohort. Am J Ophthalmol. 1996;121:284–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perros P, Crombie AL, Matthews JNS, Kendall-Taylor P. Age and gender influence the severity of thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy: A study of 101 patients attending a combined thyroid-eye clinic. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1993;38:367–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patel VK, Padnick-Silver L, D’Souza S, Bhattacharya RK, Francis-Sedlak M, Holt RJ. Characteristics of Diabetic and Nondiabetic Patients With Thyroid Eye Disease in the United States: A Claims-Based Analysis. Endocr Pract. 2022;28:159–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tellez M, Cooper J, Edmonds C. Graves’ ophthalmopathy in relation to cigarette smoking and ethnic origin. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1992;36:291–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stan MN, Bahn RS. Risk factors for development or deterioration of Graves’ ophthalmopathy. Thyroid. 2010;20:777–783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.IRIS Registry Data Analysis Overview. https://www.aao.org/iris-registry/data-analysis/requirements; 2022. Accessed December 2, 2022.

- 9.Stein JD, Childers D, Gupta S, Talwar N, Nan B, Lee BJ, Smith TJ, Douglas R. Risk factors for developing thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy among individuals with graves disease. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2015;133:290–296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chin YH, Ng CH, Lee MH, Koh JWH, Kiew J, Yang SP, Sundar G, Khoo CM. Prevalence of thyroid eye disease in Graves’ disease: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2020;93:363–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chiang MF, Sommer A, Rich WL, Lum F, Parke DW. The 2016 American Academy of Ophthalmology IRIS® Registry (Intelligent Research in Sight) Database: Characteristics and Methods. Ophthalmology. 2018;125:1143–1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laurberg P, Berman DC, Bülow Pedersen I, Andersen S, Carlé A. Incidence and Clinical Presentation of Moderate to Severe Graves’ Orbitopathy in a Danish Population before and after Iodine Fortification of Salt. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:2325–2332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hiromatsu Y, Eguchi H, Tani J, Kasaoka M, Teshima Y. Graves’ ophthalmopathy: Epidemiology and natural history. Intern Med. 2014;53:353–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bartley GB, Fatourechi V, Kadrmas EF, Jacobsen SJ, Ilstrup DM, Garrity JA, Gorman CA. The incidence of Graves’ ophthalmopathy in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Am J Ophthalmol. 1995;120:511–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lim NCS, Sundar G, Amrith S, Lee KO. Thyroid eye disease: A Southeast Asian experience. Br J Ophthalmol. 2015;99:512–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Woo KI n., Kim YD, Lee SY eu. Prevalence and risk factors for thyroid eye disease among Korean dysthyroid patients. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2013;27:397–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bahn RS, Heufelder AE. Pathogenesis of Graves’ ophthalmopathy. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1468–1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lim SL, Lim AKE, Mumtaz M, Hussein E, Wan Bebakar WM, Khir AS. Prevalence, risk factors, and clinical features of thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy in multiethnic Malaysian patients with Graves’ disease. Thyroid. 2008;18:1297–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Naik MN, Vasanthapuram VH. Demographic and clinical profile of 1000 patients with thyroid eye disease presenting to a Tertiary Eye Care Institute in India. Int Ophthalmol. 2021;41:231–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Muralidhar A, Das S, Tiple S. Clinical profile of thyroid eye disease and factors predictive of disease severity. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2020;68:1629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reddy SVB, Jain A, Yadav SB, Sharma K, Bhatia E. Prevalence of graves’ ophthalmopathy in patients with graves’ disease presenting to a referral centre in north India. Indian J Med Res. 2014;139:99–104. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mbarek S, Abid F, Ammari W, Alaya W, Mahmoud A, Messaoud R. Graves’ Orbitopathy: Report of 82 cases. Tunis Med. 2021;99:243–251. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Juan E, Hurley DP, Sapira JD. Racial Differences in Normal Values of Proptosis. Arch Intern Med. 1980;140:1230–1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim IT, Choi JB. Normal Range of Exophthalmos Values on Orbit Computerized Tomography in Koreans. Ophthalmologica. 2001;215:156–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chng CL, Seah LL, Khoo DHC. Ethnic differences in the clinical presentation of Graves’ ophthalmopathy. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;26:249–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fry CL, Naugle TC, Cole SA, Gelfond J, Chittoor G, Mariani AF, Goros MW, Haik BG, Voruganti VS. The latino eyelid: Anthropometric analysis of a spectrum of findings. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;33:440–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marcocci C, Kahaly GJ, Krassas GE, Bartalena L, Prummel M, Stahl M, Altea MA, Nardi M, Pitz S, Boboridis K, Sivelli P, von Arx G, Mourits M, Baldeschi L, Bencivelli W, Wiersinga W for the European Group on Graves’ Orbitopathy. Selenium and the Course of Mild Graves’ Orbitopathy. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1920–1931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu Y, Liu S, Mao J, Piao S, Qin J, Peng S, Xie X, Guan H, Li Y, Shan Z, Teng W. Serum Trace Elements Profile in Graves’ Disease Patients with or without Orbitopathy in Northeast China. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018: 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Planck T, Shahida B, Malm J, Manjer J. Vitamin D in graves disease: Levels, correlation with laboratory and clinical parameters, and genetics. Eur Thyroid J. 2018;7:27–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thornton J, Kelly SP, Harrison RA, Edwards R. Cigarette smoking and thyroid eye disease: a systematic review. Eye. 2007;21:1135–1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shine B, Fells P, Edwards OM, Weetman AP. Association between Graves’ ophthalmopathy and smoking. Lancet. 1990;335:1261–1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bartalena L, Marcocci C, Tanda ML, Manetti L, Dell’Unto E, Bartolomei MP, Nardi M, Martino E, Pinchera A. Cigarette Smoking and Treatment Outcomes in Graves Ophthalmopathy. Ann Intern Med. 1998;129:632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nunery WR, Martin RT, Heinz GW, Gavin TJ. The Association of Cigarette Smoking with Clinical Subtypes of Ophthalmic Gravesʼ Disease. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg.993;9:77–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bartalena L, Tanda ML, Piantanida E, Lai A. Oxidative stress and Graves’ ophthalmopathy: In vitro studies and therapeutic implications. BioFactors. 2003;19:155–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Le Moli R, Muscia V, Tumminia A, Frittitta L, Buscema M, Palermo F, Sciacca L, Squatrito S, Vigneri R. Type 2 diabetic patients with Graves’ disease have more frequent and severe Graves’ orbitopathy. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2015;25:452–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report website. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/data/statistics-report/index.html. Accessed 02/25/2022.

- 37.Brismar K, Fernqvist-Forbes E, Wahren J, Hall K. Effect of insulin on the hepatic production of insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-1 (IGFBP-1), IGFBP-3, and IGF-I in insulin-dependent diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1994;79:872–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ben Simon GJ, Katz G, Zloto O, Leiba H, Hadas B, Huna-Baron R. Age differences in clinical manifestation and prognosis of thyroid eye disease. Graefe’s Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2015; 253:2301–2308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Campbell AA, Nanda T, Oropesa S, Kazim M. Age-Related Changes in the Clinical Phenotype of Compressive Optic Neuropathy in Thyroid Eye Disease. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;35:238–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kendler DL, Lippa J, Rootman J. The Initial Clinical Characteristics of Graves’ Orbitopathy Vary With Age and Sex. Arch Ophthalmol. 1993;111:197–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Uddin JM, Rubinstein T, Hamed-Azzam S. Phenotypes of Thyroid Eye Disease. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2018;34:S28–S33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pfeilschifter J, Ziegler R. Smoking and endocrine ophthalmopathy: impact of smoking severity and current vs lifetime cigarette consumption. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1996;45:477–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li Z, Cestari D, Fortin E. Thyroid eye disease: what is new to know? Current Opinion Ophthal 2018; 29: 528–534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.