Eyelid nystagmus is a slow, rhythmic, involuntary movement of both levator palpebrae muscles seldom reported in the literature. It has been related to lesions involving the brainstem or cerebellum. Here we report a case occurring in isolation and discuss its current nosological status.

Case Report

A 75‐year‐old right‐handed woman was followed up at our clinic for a 6‐year history of non‐progressive unsteadiness. Her background was relevant for hypertension, Graves‐Basedow disease, and lumbar spinal stenosis. The examination revealed a slow gait with decreased step height and generalized hyperreflexia, consistent with a higher‐level gait disorder. No parkinsonian, cerebellar or other pyramidal signs were elicited. In addition, non‐distressing slow, rhythmic, symmetrical movements of the upper lids, exacerbated by lateral gaze were noted (Video 1). Both phases of the movement seemed to show a similar velocity in the absence of other abnormal movements of the eyes. It was consistent with previously reported cases of eyelid nystagmus.

Video 1.

Eyelid nystagmus. Slow, rhythmic, symmetrical movements of the upper lids, exacerbated by lateral gaze can be seen.

Analytical tests (hemogram, biochemistry, serologies for syphilis and HIV, and thyroid function) were normal. An autoimmunity profile showed positive antithyroid antibodies and negative antinuclear as well as nuclear and surface antineuronal antibodies. A 1.5 T brain MRI showed advanced leukoencephalopathy with major involvement of the middle pons, suggesting vascular etiology (Fig. 1A–C). A cervical MRI showed diffuse spondylosis with no signs of myelopathy. The CSF analysis, including cellular count, proteins, glucose and oligoclonal bands was normal.

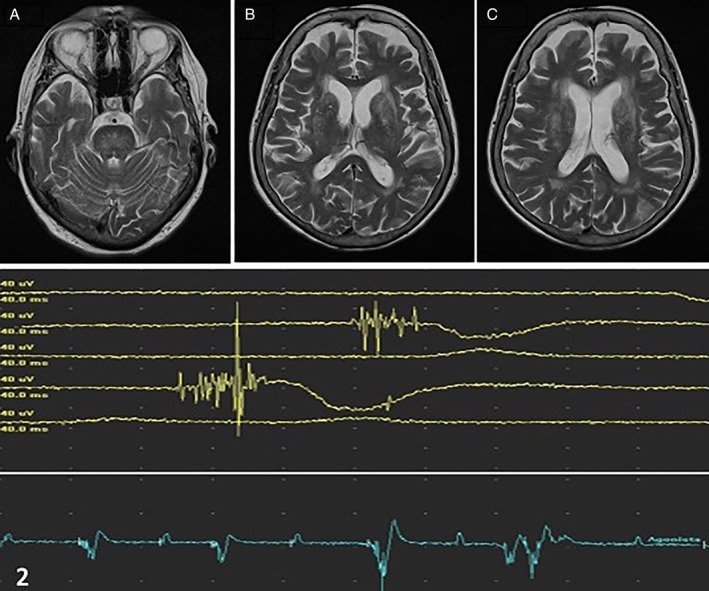

Figure 1.

(A–C) Axial T2‐weighted MRI at the pons (A), basal ganglia (B) and corona radiata (C) levels. (2) Electromyography of levator palpebrae muscle. Rhythmic or semi rhythmic movements (bottom line) of normal morphology bursts (upper lines) with a duration of about 50 ms are registered.

An EMG of the levator palpebrae showed a continuous slow semi‐rhythmic activity (1–2 Hz.) of short EMG bursts (lasting around 50 ms), whose amplitude was attenuated in the vertical versions (especially infraversion, where presumably physiological levator inhibition silences electromyographic activity) and clearly exacerbated by lateral gaze (Fig. 1 and 2).

Discussion

Eyelid nystagmus was first recognized in 1916 by Pick. 1 Very few other cases have been reported, whose features are summed in Table 1. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 Although the phenomenology shows resemblances in all cases, there are differential features that raise pathophysiological questions. Some cases are coupled with the fast phase of ocular vertical nystagmus, which may point to an aberrant activation of the otherwise normally coordinated movement of the lids and eyes, reported in lesions possibly involving the ventral tegmental tract. 5 , 10 , 14 In the case by Daroff, eyelid nystagmus was attributed to a disruption of the spinocerebellar pathways. 3 The cases elicited by ocular convergence were related to pathways connected with the cerebellum. 1 , 4 , 5 , 7 , 8 , 13 In our case, eyelid nystagmus was exacerbated by lateral versions and unaccompanied by abnormal eye movements. These features make us suggest that the underlying pathophysiology may not be unique, and different types of eyelid nystagmus could be caused by the involvement of different pathways. Especially in cases without ocular nystagmus such as ours we hypothesize that the lid nystagmus could be regarded either as a form of slow tremor or a form of myorhythmia.

TABLE 1.

Previous eyelid nystagmus cases reported, subtypes, and etiologies (chronological order)

| Author, year | Type of eyelid nystamgus | Etiology |

|---|---|---|

| Pick, 1916 1 | Convergence‐evoked | Multiple sclerosis |

| Site of the lesion not confirmed | ||

| Popper, 1916 2 | Coupled with fast phase of gaze‐evoked horizontal eye nystagmus | Harmful use of alcohol |

| Site of the lesion not confirmed | ||

| Daroff, 1968 3 | Gaze‐evoked | Lateral medullary stroke |

| Inhibited by near reflex | ||

| Sanders, 1968 4 | Convergence‐evoked | Cerebellar sarcoma |

| Rohmer, 1972 5 | 1. – Coupled with upbeat eye nystagmus | 1. – Multiple sclerosis |

| 2. – Exacerbated by lateral gaze and upward optokinetic reflex | 2. – Head injury | |

| 3. – Head injury | ||

| 3. – Elicited by upward optokinetic reflex, right lateral gaze and convergence | ||

| Salisachs, 1977 6 | Elicited by head rotation with upward component and downward optokinetic reflex (cases 1 and 2) | Miller‐Fisher syndrome |

| Convergence‐evoked (case 2) | ||

| Safran, 1982 7 | Convergence‐evoked | 1. – Head injury |

| 2. – Cerebellar vermis tumor | ||

| Howard, 1986 8 | Convergence‐evoked | Brainstem vascular malformation |

| Brodsky, 1995 9 | Lateral‐gaze evoked | Midbrain low‐grade astrocytoma |

| Milivojević, 2013 10 | Coupled with primary position upbeat eye nystagmus | Pontine hemorrhage |

| Matarazzo, 2016 11 | Coupled with fast phase of horizontal eye nystagmus, exacerbated with lateral versions | Toxic: |

| 1. – Carbamazepine | ||

| 2. – Oxcarbazepine | ||

| Costa, 2021 12 | Horizontal gaze‐evoked | Miller‐Fisher syndrome post‐COVID 19 |

| Scheitler, 2021 13 | Convergence‐evoked | Thalamic‐midbrain hematoma |

Myorhythmia is a slow rhythmic movement affecting the cranial and/or limb muscles, occurring at rest but also present while maintaining a posture. 15 Electromyography shows discharges of motor units with normal, variable morphology at 1–4 Hz. 15 Two major forms have been described: limb myorhythmia and oculomasticatory myorhythmia 15 whereas a third form, palatal tremor, is a matter of controversy. Palatal tremor is currently regarded as a form of focal slow tremor, 16 although only an agonist muscle is involved and it often shows irregularity within the movement. 17 Furthermore, the symptomatic forms of palatal tremor are frequently accompanied by ocular pendular nystagmus (ie, oculopalatal tremor) or other involuntary movements such as myorhythmia involving mainly the cranial muscles, 17 and some authors have suggested to integrate it within the spectrum of myorhythmia. 15 Limb myorhythmia and oculopatalal tremor have been related often with ischaemic vascular lesions, although other etiologies have been documented (eg, pontine hemorrhage, posterior fossa tumors or head injury). 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 Oculomasticatory myorhythmia is a highly distinctive feature of Whipple's disease, often considered as pathognomonic.

The pathophysiology of myorhythmia and slow tremors remains elusive. Nevertheless, their low‐rate rhythmicity point to a central supraspinal pacemaker. In the case of oculopalatal tremor, the inferior olive has been invoked as the generator, whose signal would be then amplified by the deep cerebellar nuclei within the so‐called Guillain‐Mollaret triangle. 15 , 18 Although hypertrophy of the inferior olivary nucleus is frequent in cases of oculopalatal tremor, it rarely develops in other forms of slow tremors or myorhythmias. 15 , 18 Following this model, we hypothesize that an unknown central pacemaker could be responsible for the genesis of the eyelid movement, which could then be modulated through other pathways (eg, cerebellothalamic).

In conclusion, we report a case of isolated eyelid nystagmus possibly attributable to vascular disease. Regarding its clinical and electrical features, we hypothesize that this case could be integrated within the spectrum of slow tremors or myorhythmia. This suggestion needs, however, to be taken cautiously. Indeed, eyelid nystagmus has not been related to other movements than eye nystagmus, whereas slow tremors and myorhythmia may co‐occur with other rhythmic movements. 15 , 17 Therefore, we consider that our suggestions must be best regarded as a source of debate. Further clinicoradiological and neurophysiological reports are needed to clarify the nosology of this very particular phenomenon.

Author Roles

(1) Research Project: A. Conception, B. Organization, C. Execution; (2) Manuscript Preparation: A. Writing of the First Draft, B. Review and Critique.

C.M.O.: 1A, 1C, 2A

A.Q‐C.: 1B, 1C, 2B

L.Y‐G.: 1C, 2B

Disclosures

Ethical Compliance Statement: Written informed constent for video publishing was obtained from the patient. The authors confirm that the approval of an institutional review board was not required for this work. We confirm that we have read the Journal's position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this work is consistent with those guidelines.

Funding Sources and Conflicts of Interest: No conflict of interests are reported by the authors. No specific funding was received for this study.

Financial Disclosures for Previous 12 Months: The authors declare that there are no additional disclosures to report.

References

- 1. Pick A. Kleine Beitrage zur Neurologie des Auges; Ober den Nystagmus der Bulbi begleitende gleichartige Bewegungen des oberen Augenlides (Nystagmus des 004Fberlides.). Arch Augenheilk 1916;80:36–40. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Popper E. Ein Beitrag zur Frage des "Lidnystagmus". Mschr Psychiat Neurol 1916;39:188–192. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Daroff RB, Hoyt WF, Sanders MD, Nelson LR. Gaze‐evoked eyelid and ocular nystagmus inhibited by the near reflex: unusual ocular motor phenomena in a lateral medullary syndrome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psiquatr 1968;31(4):362–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sanders MD, Hoyt WF, Daroff RB. Lid nystagmus evoked by ocular convergence: an ocular electromyographic study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1968. Aug;31(4):368–371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rohmer F, Conraux C, Collard M. Convergence nystagmus and palpebral nystagmus. Rev Oto‐Neuro‐Ophthalmol 1972;44:89–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Salisachs P, Lapresle J. Upper lid jerks in the fisher syndrome. Eur Neurol 1977;15(4):237–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Safran AB, Berney J, Safran E. Convergence‐evoked eyelid nystagmus. Am J Ophthalmol 1982;93(1):48–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Howard RS. A case of convergence evoked eyelid nystagmus. J Clin Neuroophthalmol 1986;6(3):169–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Brodsky MC, Boop FA. Lid nystagmus as a sign of intrinsic midbrain disease. J Neuroophthalmol 1995;15(4):236–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Milivojević I, Bakran Ž, Adamec I, Miletić Gršković S, Habek M. Eyelid nystagmus and primary position upbeat nystagmus. Neurol Sci 2013;34(8):1463–1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Matarazzo M, Galán Sánchez‐Seco V, Méndez‐Guerrero AJ, Gata‐Maya D, Domingo‐Santos Á, Ruiz‐Morales J, Benito‐León J. Drug‐related eyelid nystagmus: two cases of a rare clinical phenomenon related to carbamazepine and derivatives. Clin Neuropharmacol 2016;39(1):49–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Costa AF, Rodríguez A, Martínez P, Blanco DCM. Teaching video NeuroImage: uncommon neuro‐ophthalmic finding in a patient with miller fisher syndrome and past SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. Neurology 2021;97(24):e2431–e2432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Scheitler KM, Mustafa R, Wijdicks EFM. Lid and convergence retraction nystagmus in thalamic–midbrain hematoma. Neurocrit Care 2021;34:691–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Helmchen C, Rambold H. The eyelid and its contribution to eye movements. Dev Ophthalmol 2007;40:110–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Baizabal‐Carvallo JF, Cardoso F, Jankovic J. Myorhythmia: phenomenology, etiology, and treatment. Mov Disord 2015;30(2):171–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bhatia KP, Bain P, Bajaj N, et al. Consensus Statement on the classification of tremors. From the task force on tremor of the International Parkinson and Movement Disorder Society. Mov Disord 2018;33(1):75–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Erro R, Reich SG. Rare tremors and tremors occurring in other neurological disorders. J Neurol Sci 2022;15(435):120200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Shaikh AG, Hong S, Liao K, et al. Oculopalatal tremor explained by a model of inferior olivary hypertrophy and cerebellar plasticity. Brain 2010;133(3):923–940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]