Abstract

Background –

The 10-year Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease (ASCVD) risk score is the standard approach to predict risk of incident cardiovascular events, and recently, addition of CAD polygenic scores (PGSCAD) have been evaluated. Although age and sex strongly predict the risk of CAD, their interaction with genetic risk prediction has not been systematically examined. This study performed an extensive evaluation of age and sex effects in genetic CAD risk prediction.

Methods –

The population-based Norwegian HUNT2 cohort of 51,036 individuals was used as the primary dataset. Findings were replicated in the UK Biobank (372,410 individuals). Models for 10-year CAD risk were fitted using Cox proportional hazards and Harrell’s concordance index, sensitivity, and specificity were compared.

Results –

Inclusion of age and sex interactions of PGSCAD to the prediction models increased the C-index and sensitivity by accounting for non-additive effects of PGSCAD and likely countering the observed survival bias in the baseline. The sensitivity for females was lower than males in all models including genetic information. We identified a total of 82.6% of incident CAD cases by using a two-step approach: i) ASCVD risk score (74.1%) and ii) the PGSCAD interaction model for those in low clinical risk (additional 8.5%).

Conclusions –

These findings highlight the importance and complexity of genetic risk in predicting CAD. There is a need for modeling age and sex-interactions terms with polygenic scores to optimize detection of individuals at high-risk, those who warrant preventive interventions. Sex-specific studies are needed to understand and estimate CAD risk with genetic information.

Keywords: risk prediction, polygenic score, coronary artery disease, interactions, survival bias

Introduction

Coronary artery disease (CAD) is a complex disease influenced by risk factors including hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, tobacco use, age, and genetics, which leads to high morbidity and mortality1. The American College of Cardiology / American Heart Association2 recommends the 10-year Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease (ASCVD) risk score [calculated with the Pooled Cohort Equation (PCE)] to estimate an individual’s risk using several demographic and cardiovascular disease risk factors. Other models include Systematic COronary Risk Evaluation (SCORE)3, QRISK4, Framingham risk score5, and NORRISK6. The predictive capacity of these models is moderate (C-index is between 0.6–0.8), depending on characteristics (ie., age, statin use) of the external validation dataset7–10.

There is significant additive value of integrating genome-wide genetic data to enhance risk prediction using polygenic scores (PGS)7–10. Additionally, individuals with a PGS in the highest 8% of score distribution have a risk of CAD comparable to having monogenic familial hypercholesterolemia (3-fold increased risk)10. To date, investigators have shown that adding PGS11–17 to standard risk prediction algorithms enhances the power of the model to predict CAD, consistent with the estimated contribution of genetic factors responsible for 40–50% of CAD risk18.

The most predictive components of CAD prediction models are age and sex2. The interplay of these two factors with the other traditional risk factors has been evaluated extensively in epidemiologic studies2–6. However, only a limited amount of genetic risk prediction studies have evaluated the CAD risk separately for males and females19–21. Of these three studies, two used PGSs based on significant CAD SNPs only, whereas, Huang et al. additionally evaluated the performance of polygenic score with more than one million variants. All these studies concluded that genetic prediction works better for males than for females. However, these studies did not model longitudinal time to event which is required to evaluate the usefulness of the score in the clinical setting. To systematically evaluate the age and sex effects in the genetic CAD risk prediction, we used a longitudinal population-based dataset of 51,036 samples from Norway and performed Cox proportional hazards models to explore how age and sex impact CAD genetic risk prediction (Supplemental Table 1, Supplemental Methods). The objective was to identify whether CAD genetic risk scores’ performance in the prediction of incident CAD depends on a patient’s age and sex.

Methods

Desccriptions of the used datasets and detailed statistical analysis methods can be found from Supplemental Methods. Participation in the The Trøndelag Health (HUNT) Study is based on informed consent and the study has been approved by the Data Inspectorate and the Regional Ethics Committee for Medical Research in Norway (REK: 2014/144). The summary level HUNT2 data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. UK Biobank had obtained ethics approval from the North West Multi-centre Research Ethics Committee. All UK Biobank data and materials have been made public for research purposes and can be accessed at https://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk.

Results

CAD Polygenic Score and Correlations with Age and Sex

We initially tested whether the genome-wide polygenic score for CAD estimated using metaGRS weights12 (hereafter called the PGSCAD) was associated with sex or age in HUNT2 before examining how to optimally account for age and sex in CAD risk-stratification model. In principle, one would expect PGSs for various diseases to show equivalent distributions among males and females, provided age, sex, and ancestry are corrected in the underlying summary statistics and sex-chromosomes are excluded from the evaluation. However, the relationship between the PGS, sex, and age could be impacted by ascertainment bias, undetected population stratification, or survival bias by genotype.

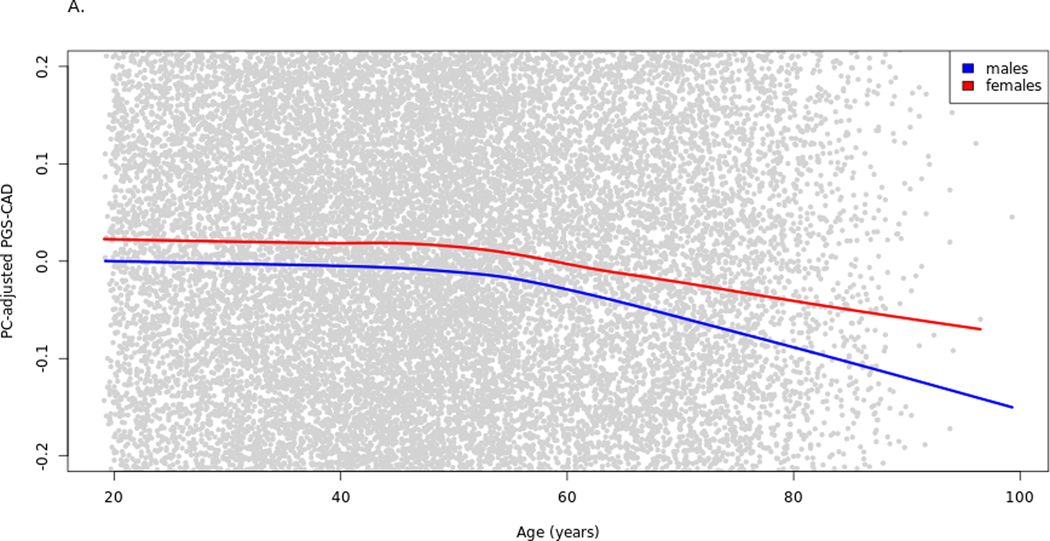

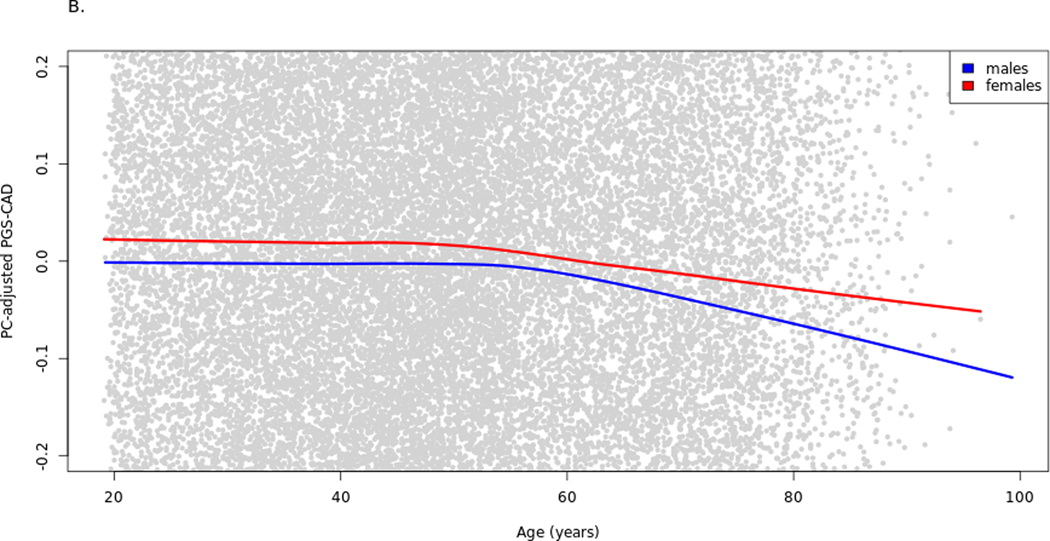

Significant associations were observed between enrollment age and PGSCAD and between sex and PGSCAD when assessing baseline data only (Supplemental Table 2A–B). These results suggest that there is non-random selection in the cohort related to PGSCAD, possibly ascertainment bias or survival effects. Based on the results from these two models, males at baseline had an average 0.06 SD-units lower PGSCAD than females, and the PGSCAD was 0.003 SD-units lower per year of age. The association of age with PGSCAD was significant for both males and females (Supplemental Table 2C–D), although the effect for males was marginally higher (PGSCAD 0.0032 SD-units lower per year for males, 0.0025 for females) (Figure 1A). However, when adding the interaction term to the linear regression model, age*sex term was not significant (P-value = 0.212). The sex-PGSCAD association was partly age dependent as the effect of sex on PGSCAD becomes non-significant (P-value = 0.404) when the interaction term is added (Supplemental Table 2E). The age and sex associations were confirmed by testing the models in the UK Biobank. In UK Biobank, the interaction term age*sex on the PGSCAD was statistically significant (P-value = 1.0e-8; Supplemental Table 3A–C, Supplemental Figure 1A). The trends were reduced when including the prevalent cases (together with the baseline statin users in the UK Biobank) in the baseline analysis for both datasets, (N=1,455 in HUNT2, N=84,292 in UK Biobank; Figure 1B, Supplemental Table 4A–B, Supplemental Figure 1B). The slight gradual decrease in mean PGSCAD by age, particularly in men, could be due to lower survival of older males with high PGSCAD, who are probably absent from the cohort at baseline (and some of whom were excluded from analyses due to prevalent or earlier-onset CAD).

Figure 1.

Raw PGSCAD by age and sex in the cohort baseline. Illustration of the selection bias in the cohort baseline using lowess curves for PGSCAD by age for males and females separately. The plot has been zoomed in relative to the y-axis to better show the trends. Panel A shows the trends in the analysis dataset used in the Cox models (prevalent cases excluded) and panel B when prevalent cases are included. PGS-CAD = PGSCAD = Coronary artery disease polygenic score.

CAD Polygenic Score and Age and Sex Interaction Models

The PGSCAD performance was tested while explicitly modeling age, sex, and a comprehensive set of interaction terms to counter the survival bias observed at baseline. We used an additive PGSCAD model (model C1, Supplemental Table 5) as the comparison model to test the effect of added interaction effects to the model performance (Supplemental Table 6). To fully capture any potential interactions, a model including all interaction terms of age, sex, and PGSCAD was examined. Specifically, we aimed to test for the possible age-dependent (Age*PGSCAD term) and sex-dependent (Sex*PGSCAD term) behavior of the PGSCAD, and age-effects of the PGSCAD predictive performance that may differ between males and females (Age*Sex*PGSCAD term) (model C2).

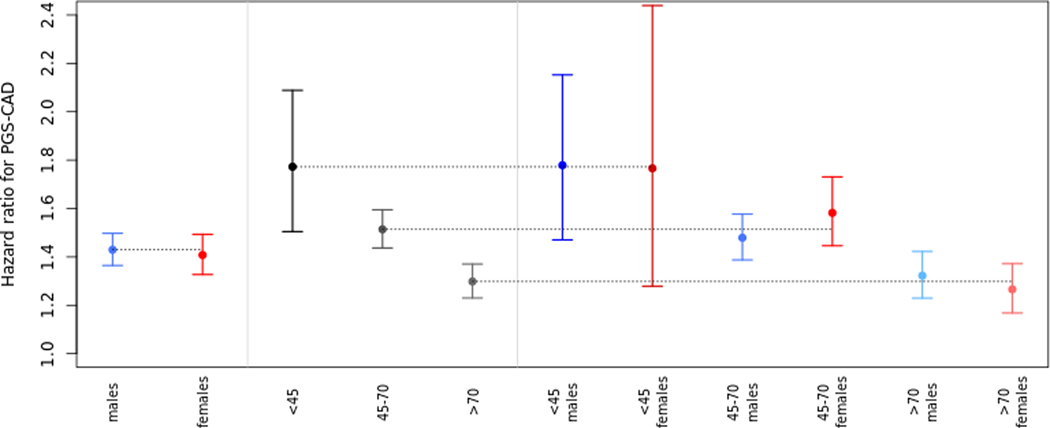

The sensitivity (78.4%) increased in the full interaction model (model C2, Supplemental Table 7) compared to the model with additive genetic effects only (model C1) (sensitivity 77.0%, Table 1), whereas, the C-index did not show a significant increase (model C2 C-index 0.839 [0.833; 0.845], model C1 C-index 0.838 [0.832; 0.844]). Similarly in the UK Biobank, the C-index did not change. The sensitivity increased after adding the interaction terms while specificity decreased. The overall sensitivity and specificity values between the two cohorts are different likely due to the well-known bias towards healthier individuals in the UK Biobank dataset (consistent with later analyses where the 7.5% risk threshold to classifies a smaller proportion of individuals into the high-risk group). However, the proportional gain in the sensitivity was consistent between the two cohorts (1.8% increase in HUNT2 and 1.2% in UK Biobank). Figure 2 illustrates the effect of the Age*Sex*PGSCAD term in the HUNT2 dataset. The hazard ratios (HRs) for the PGSCAD on CAD 10-year risk with a model fit separately for males and females were not significantly different. However, we observed significant differences in model performance between the age groups when stratifying the dataset into three age-bins, demonstrating an age interaction. When further stratifying both males and females separately into age bins (approximating the Age*Sex*PGSCAD interaction term in model C2), we observed small differences in the HRs between males and females in the same age bins, which however, were not statistically significant due to the lower number of samples in the subgroups. Simultaneously, we added an age*sex interaction term to ensure the model was valid by including all lower-level effects. The positive beta of this term indicates that irrespective of the PGSCAD, age increases the CAD risk more substantially for females compared to males. This observation may be due the effect of menopause on increased CAD risk in females22.

Table 1.

Diagnostic metrics for additive PGSCAD model (model C1) and PGSCAD model with all interactions (model C2) in HUNT2 and UK Biobank.

| Dataset | Risk model | Incident cases with risk ⋝7.5% | Incident cases with risk <7.5% | Non-cases with risk ⋝7.5% | Non-cases with risk <7.5% | Specificity/Selectivity | Sensitivity/Recall | C-index [95% confidence interval] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HUNT2 | PGSCAD additive model (model C1) | 2290 | 684 | 11133 | 36929 | 76.8% | 77.0% | 0.838 [0.832; 0.844] |

| HUNT2 | PGSCAD with all interactions (model C2) | 2332 | 642 | 11539 | 36523 | 76.0% | 78.4% | 0.839 [0.833; 0.845] |

| UK Biobank | PGSCAD additive model (model C1) | 8688 | 8881 | 52201 | 233948 | 84.6% | 66.4% | 0.743 [0.739; 0.746] |

| UK Biobank | PGSCAD with all interactions (model C2) | 8996 | 8573 | 54913 | 231236 | 83.9% | 67.2% | 0.743 [0.740; 0.747] |

PGSCAD=Coronary artery disease polygenic score

Figure 2.

Age dependence of the sex-effect. This figure shows the hazard ratios with 95% confidence intervals for PGSCAD in models fitted in 11 different subsets. Subsets were separated by sex (males, females), by age (<45-year-old, between 45 and 70, and more than 70-year-old) and finally stratified by both. All models have been adjusted for within-bin age and age2-effects and additionally the 3 age-bin models for sex. PGS-CAD = PGSCAD = Coronary artery disease polygenic score.

CAD Polygenic Score with ASCVD risk score

Modeling clinical and genetic risk together

We expect that genetic risk will most likely be used in conjunction with or in addition to already existing risk estimates. With this in mind, we modeled the ASCVD risk score with the PGSCAD. Our model with additive effects only (model C3, Supplemental Table 8) had a higher C-index (0.842 [0.836; 0.848]) and slightly lower sensitivity than model C1 (76.8%), which suggests that including the ASCVD risk score (i.e., clinical score) on top of the PGSCAD does not increase the number of identified cases, but rather affects the specificity, which increases from 76.8% (in model C1) to 77.4% (in model C3 which in includes ASCVD risk), and is observable as an increase in the C-index. This finding could be caused by reduced transferability of PCE into Norwegian population. However, to evaluate the impact of the genetic interaction terms in a model with the clinical risk included, we tested the improvement in the model metrics by including the ASCVD risk score into the full PGSCAD interaction model (model C4, Table 2). This model had the highest C-index (0.845 [0.839; 0.851]) and sensitivity (79.6%) of the combined prediction models. Moreover, when comparing the model with PGSCAD and ASCVD predictors but without the interaction terms (model C3) to the same model with genetic interaction terms (model C4) the sensitivity increased from 76.8% to 79.7% while specificity decreased from 77.4% to 76.0%. Almost all of the interaction terms showed significant P-value in this model (Table 2) suggesting that the interactions between the genetic risk and age and sex should be taken into account when modeling the clinical and genetic risk together.

Table 2.

Model statistics for PGSCAD model with all interactions and ASCVD in HUNT2 (model C4)

| Variable/term (units) | Effect | SE | HR | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age2 (year2) | −2.8e-3 | 1.5e-4 | 0.997 | 9.4e-83 |

| Sex (female=0, male=1) | 3.24 | 0.255 | 25.47 | 7.1e-37 |

| Age (year) | 0.417 | 0.018 | 1.517 | 3.25e-119 |

| PGSCAD (SD-unit) | 1.21 | 0.182 | 3.369 | 2.3e-11 |

| ASCVD (risk/100) | 3.01 | 0.199 | 20.33 | 1.2e-51 |

| Sex*Age (year for males compared to females) | −0.041 | 3.8e-3 | 0.960 | 7.3e-28 |

| Sex*PGSCAD (SD-units for males compared to females) | −0.436 | 0.221 | 0.647 | 0.048 |

| Age*PGSCAD (SD-units per year) | −0.013 | 2.6e-3 | 0.987 | 6.9e-7 |

| Sex*Age*PGSCAD (SD-units per year for males compared to females) | 6.2e-3 | 3.2e-3 | 1.006 | 0.052 |

SE=Standard error of the effect, HR=Hazard ratio, PGSCAD=Coronary artery disease polygenic score, SD=Standard deviation, ASCVD=Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk score

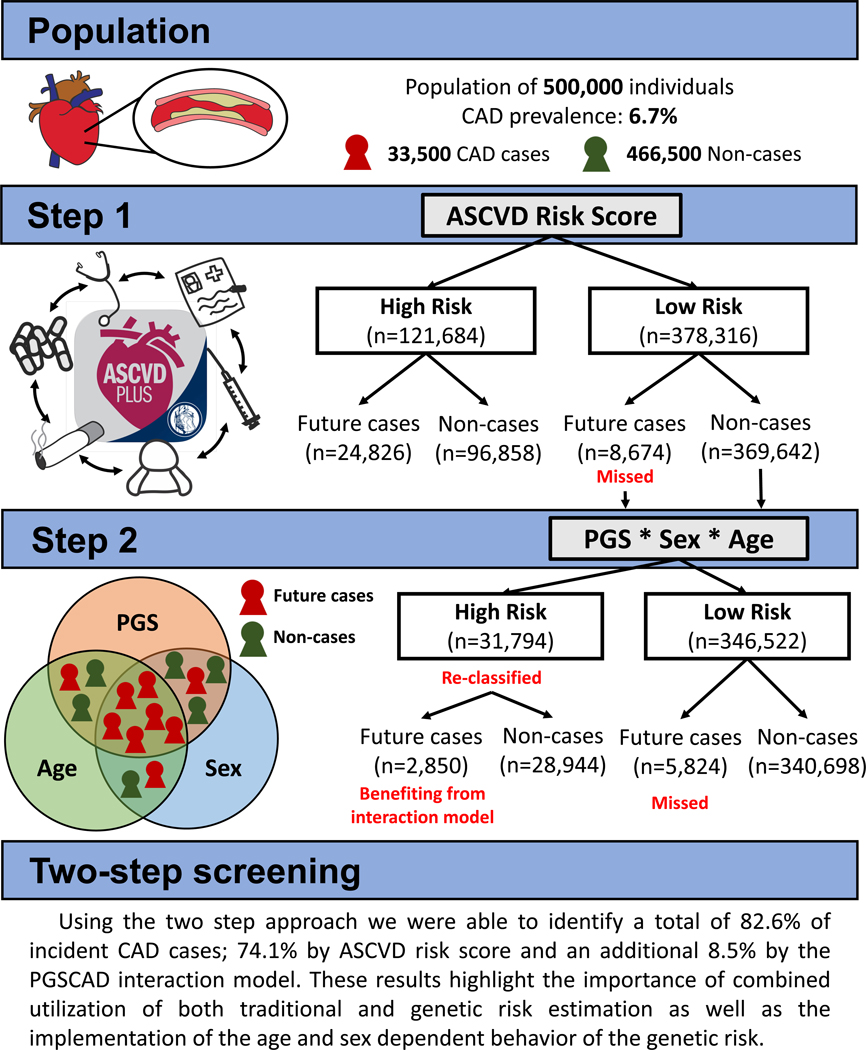

Two-step Approach

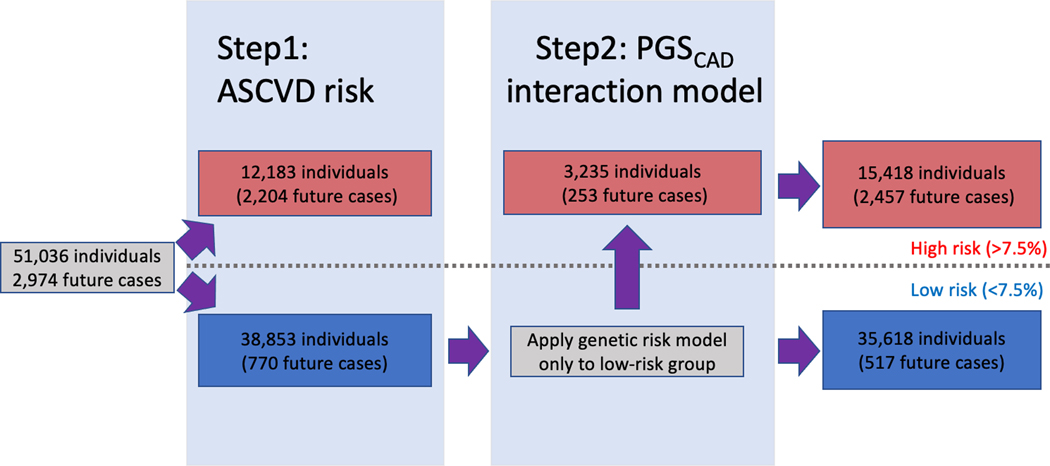

We also tested a scenario where the PGSCAD could be added as an independent risk estimation tool to identify additional cases that were not already identified by their ASCVD risk score. This two-step case identification procedure is based on two sequential and independent risk estimates. After identifying high-risk individuals by the ASCVD risk score we applied the PGSCAD risk model to the remaining individuals, including interaction terms (effects coming from the model C2 for the full population with full population variable distributions). This staged approach, where ASCVD is first applied and PGSCAD with genetic interaction terms is then applied, newly classified 3,235 individuals as high-risk (8.3% of the remaining dataset or 27.2% of the total dataset) totaling to 82.6% of the cases identified with the two-step approach. Among those newly classified, we observed 253 additional future cases during the 10-year follow-up (32.9% of the cases missed by the ASCVD score; Figure 3). If we used model C1 (the model without interaction terms) in the second step instead of the model C2 with the interactions, we would identify 81.5% of the total cases instead of 82.6%, highlighting the importance of interaction modeling also when using the sequential approach. The 253 additional incident cases identified using model C2 had a mean ASCVD risk of 4.73% ranging from 1.09% to 7.49%, suggesting the PGSCAD provides information orthogonal to the ASCVD. We identified the same number of cases when applying the PGSCAD model first (model C2) and then the ASCVD risk score (individuals that have either high PGSCAD model C2 risk or high ASCVD risk). However, using the ASCVD first and then applying the genetic model may be more cost efficient as the number of samples needed to be genotyped is lower (only those with low ASCVD risk), and follows the current standard clinical practice for the first stage.

Figure 3.

Illustration of the two-step approach combining ASCVD risk and the genetic risk model in HUNT2. This figure shows how combining the atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk score (ASCVD) and the genetic risk model with interactions in two consecutive steps allows for identification of additional cases. PGSCAD = Coronary artery disease polygenic score.

Sex-Specific Models and Sex-Specificity of Model Metrics

The currently applied clinical risk scores are typically applied to males and females separately instead of using sex-interaction models. To test the applicability of our PGSCAD interaction models in the similar manner, we tested the performance of models allowing for age-dependence of the PGSCAD separately in males and females. First, we evaluated the PGSCAD model without interactions (model S1, Supplemental Tables 9A–B). The C-indexes observed were 0.850 [0.840; 0.860] for females and 0.816 [0.808; 0.824] for males, and the magnitude of the HR for the PGSCAD was similar for both sexes (HR females = 1.41 [1.33; 1.49], HR males = 1.43 [1.37; 1.50]).

The inclusion of the PGSCAD*Age interaction into the models (Supplemental Tables 10A–B) did not notably change the C-indexes, even though the interaction term was significant for both sexes (P-value in females = 1.85e-6, in males = 8.91e-4). However, the sensitivity increased for both sexes in HUNT2 (Table 3A–B). In UK Biobank, the sensitivity only increased for males (Supplementary Tables 11A–B). Both the C-index and sensitivity increased for both males and females when adding the ASCVD risk score to the model (model S3, Supplemental Tables 12A–B). Lastly, we performed the two-step process described earlier for males and females separately by including i). the conventional ASCVD risk and ii) PGSCAD with age-interaction term. Using the two-step approach, we correctly re-classified an additional 194 and 59 future cases for males and females, respectively (38.3% and 22.4% of the cases missed by the ASCVD risk assessment). We observed increased sensitivity by the two-step approach also in the UK Biobank. The corresponding numbers without the interaction terms in the second step were 183 future cases for males and 51 for females (36.1% and 19.4% of the cases missed by the ASCVD risk score).

Table 3.

Diagnostic metrics for sex-stratified models and ASCVD risk score in HUNT2

| Females Risk model | Incident cases with risk ⋝7.5% | Incident cases with risk <7.5% | Non-cases with risk ⋝7.5% | Non-cases with risk <7.5% | Specificity/Selectivity | Sensitivity/Recall | C-index [95% confidence interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASCVD | 865 | 263 | 5171 | 21256 | 80.4% | 76.7% | NA * |

| Additive PGSCAD model (model S1) | 807 | 321 | 4658 | 21769 | 82.4% | 71.5% | 0.850 [0.840; 0.860] |

| PGSCAD with age-interaction (model S2) | 823 | 305 | 4792 | 21635 | 81.9% | 73.0% | 0.851 [0.843; 0.859] |

| PGSCAD with age-interaction and ASCVD (model S3) | 833 | 295 | 4707 | 21720 | 82.2% | 73.8% | 0.859 [0.851; 0.867] |

| 2 step: ASCVD then PGSCAD with age-interaction ** | 924 | 204 | 6032 | 20395 | 77.2% | 81.9% | NA* |

| Males Risk model | Incident cases with risk ⋝7.5% | Incident cases with risk <7.5% | Non-cases with risk ⋝7.5% | Non-cases with risk <7.5% | Specificity/Selectivity | Sensitivity/Recall | C-index [95% confidence interval |

| ASCVD | 1339 | 507 | 4808 | 16827 | 77.8% | 72.5% | NA* |

| Additive PGSCAD model (model S1) | 1504 | 342 | 6727 | 14908 | 68.9% | 81.5% | 0.816 [0.808; 0.824] |

| PGSCAD with age-interaction (model S2) | 1510 | 336 | 6745 | 14890 | 68.8% | 81.8% | 0.816 [0.808; 0.824] |

| PGSCAD with age-interaction and ASCVD (model S3) | 1537 | 309 | 6828 | 14807 | 68.4% | 83.3% | 0.822 [0.814; 0.830] |

| 2 step: ASCVD then PGSCAD with age-interaction † | 1533 | 313 | 6928 | 14707 | 68.0% | 83.0% | NA* |

C-index not available as the risk score is not based on a fitted model;

This is not a model but a sequential identification of high risk individuals using first ASCVD risk score and then genetic interaction model to estimate ASCVD risk.

ASCVD=Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk score, PGSCAD=Coronary artery disease polygenic score

Sex-Specific Model Metrics and the Effect of the Risk Threshold

We saw lower sensitivity and higher specificity for females compared to males in all sex stratified models that included genetic information. These two metrics are dependent on the risk-threshold. Therefore, we tested how changing the threshold would affect the risk classification. The sensitivity and specificity for males and females for varied risk-thresholds are presented in Supplemental Figures 2–5. For all of the sex-stratified models, the percentages of individuals in the high-risk group were higher for males than for females at any given risk threshold. This finding was expected given that females have a lower overall prevalence of CAD. The proportion of individuals in the high-risk group based on ASCVD risk was close between the two sexes (Supplemental Figure 5). This is most likely due to the underestimation of the ASCVD risk seen for males when applying the ASCVD risk calculation to our test dataset (Supplemental Figure 6). Supplemental Figure 7 shows the risk calibration for the model S3 as comparison. However, lower sensitivity was observed for females for models that include the PGSCAD. To achieve the same sensitivity observed for males at the 7.5% risk threshold (81.4%), we would need to lower the risk threshold in females to 5.0% (Supplemental Figures 2,3 and 4). In all three models (S1–3), the specificity in females with the 5.0% risk threshold was better than the specificity in males with the 7.5% risk threshold.

Discussion

This study evaluated statistical approaches in two population-based datasets to fine-tune the prediction of individuals at risk for 10-year CAD events by accounting for different rates and age distributions of CAD in males and females. We found that the C-index and sensitivity of the 10-year prediction of CAD improved by including sex and age interactions when modeling PGSCAD compared to a model without interaction effects in both datasets. Inclusion of the interaction terms accounts for the non-additive effects of age and sex that have been shown to exist for many of the complex traits23. Additionally, including the interaction terms most likely corrects for the baseline survival bias observed. The implications of these results highlight the importance of modeling age and sex interactions in predicting CAD events with genetic information.

In our baseline correlation checks, we observed significant associations between the genetic score and both age and sex, and replicated these findings in the UK Biobank. The observed associations suggest non-random selection related to genetics in the study cohorts, and we contend that the age association is derived from the survival bias of individuals with lower genetic risk of CAD. The sex association is most likely derived from the earlier onset of CAD in males, which enhances the survival bias of those with lower genetic risk in males. We expect these biases to be present in all cross-sectional studies where the age ranges over the expected age-of-onset of the studied disease. Moreover, the same biases are most likely also present in populations where risk estimates are applied to identify high-risk individuals.

We evaluated the potential incorporation of genetic information into identifying at-risk individuals by modeling clinical and genetic risk at the same time or by applying two risk estimates (clinical and genetic) in a sequential manner. Both of these approaches showed increased number of cases identified when the age and sex dependent behavior of the genetic risk was taken into account. This suggests that the genetic risk should be evaluated in a similar manner as the other clinically relevant risk factors; separately for males and females and individuals of different ages. Additionally, with genome-wide genotyping being translated into clinical settings, CAD risk prediction may be enhanced by the sequential two-step approach we evaluate here: i.) first apply the existing clinical score (i.e., PCE/ASCVD risk score) and ii.) from those identified with a low ASCVD risk, apply a second model incorporating age, sex, and genetic information with age and sex interactions to identify additional high-risk individuals (Figure 4). Using our two-step approach with a set risk threshold of 7.5%, we identified a total of 82.6% of incident CAD diagnoses (74.1% by ASCVD risk estimation and an additional 8.5% by the PGSCAD interaction model). The newly identified future cases in the second step suggests that incorporating genetic information including age and sex interaction modeling captures cases that do not yet show clinical signs of atherosclerosis or hypertension (which are the biggest clinical contributors to the ASCVD risk after age and sex). The implications of these results could be two-fold i.) clinicians maintain the ability to identify high-risk individuals using the ASCVD risk tool, and ii.) clinicians with access to genetic information on patients are able to more accurately discern which additional individuals may benefit from timely prevention strategies (Figure 5). Implementation of this approach will require a large study with diverse populations to tests risk factors including genetic information to ascertain population level effects that can be applied to a single patient in clinical practice.

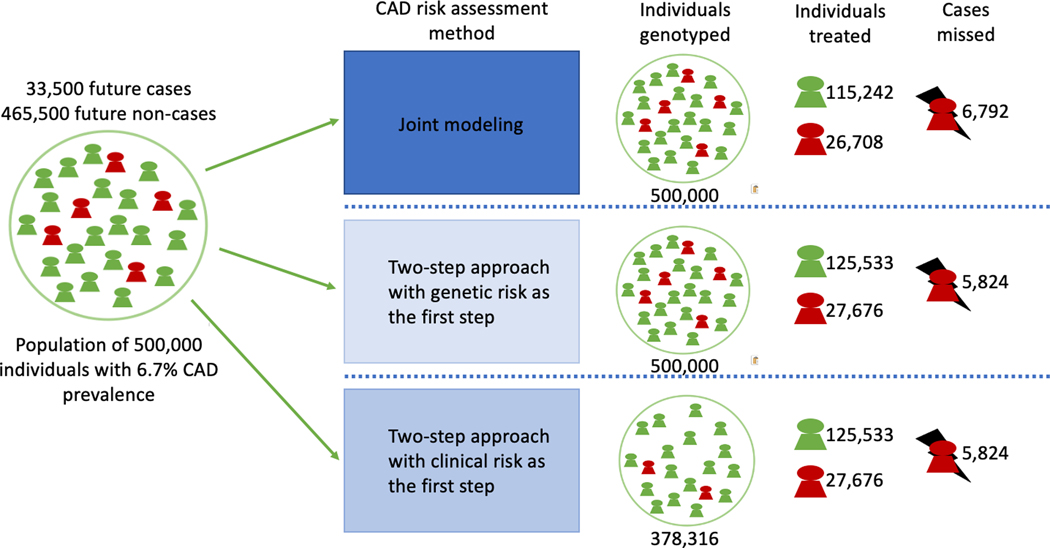

Figure 4.

Demonstration of the different risk models implementing clinical and genetic risk with interactions in a hypothetical population of 500,000 people. The Coronary artery disease (CAD) prevalence used in the demonstration is based on the current CAD prevalence in the United States.

Figure 5.

Coronary Artery Disease Polygenic Scores Used for Risk Prediction Exhibit Age and Sex-Interactions. This figure is an illustration showing the effect of the two-step approach with the age and sex interactions included in screening of 500,000 individuals. CAD = Coronary Artery Disease, n = number of samples, PGS = Polygenic score, ASCVD = Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk score

For both cohorts, the sensitivity for females was consistently lower than for males. In the HUNT2 dataset, we found that similar sensitivity to predict female cases could be achieved by lowering the risk threshold for preventive therapies from 7.5% to 5.0%. Additionally, this would not result in a higher proportion of females recommended for treatment relative to males. We suggest that the risk threshold used in the genetic screening should be independently evaluated in males and females before applying genetic information in an equal manner in the clinical setting. For example, in our dataset, if we changed the risk threshold from 7.5% to 5.0% in females when applying the two-step sequential approach, we would increase the identification of cases from 81.9% to 86.2%% without increasing the proportional amount of females suggested for treatment (25.3%) relative to males recommended for treatment (36.0%). However, as has been previously shown24, the composition of CAD risk differs between males and females also in the non-genetic risk-factors suggesting that the specificity of female CAD prediction could be improved by including additional CAD risk factors (ie., c-reative protein and hormone therapies). Nonetheless, the inclusion of genetic information into clinical practice and the effect of the inclusion to the risk-thresholds needs to be comprehensively validated in further clinical studies, ideally with sex-segregated groups.

Our study has important limitations. First, the datasets used in this study, HUNT2 and UK Biobank, are sampled from different populations than the datasets in which the ASCVD score was originally created (different ancestry, country of residence, younger, and healthier). Moreover, the ASCVD score was developed to evaluate the risk of developing CAD or stroke. In our study, we used the ASCVD score to predict CAD event or death during the 10-year follow-up time. This approach may have caused the miscalibration observed in the HUNT2 study, which limits our ability to perform unbiased one-to-one comparisons between the performance of these scoring methods. However, the trends and conclusions reported herein do not rely on the exact ASCVD risk, but rather, compare the change in the metrics when modeling genetics with and without age and sex interaction terms. Second, the participants in this study are of European ancestry, and therefore, the results may not be generalizable to populations with other ancestries25. Additional studies are needed to determine the importance of interaction effects in the genetic prediction of other traits and in diverse populations with different rates of clinical risk factors such as hypertension and high LDL cholesterol. Third, due to the lack of family history information available in the hospital registry linked HUNT2 dataset, we tested the performance of the interaction models against only one clinical score, albeit the one recommended by the American Heart Association(2). Lastly, our models were based on only a single PGS, although the performance of several different genome-wide PGSs (i.e. those derived from statistical methods such as metaGRS, LDpred or PRS-CS) have shown to be nearly equivalent in CAD prediction26.

Conclusion

All populations screened for CAD risk are subject to survival bias that shows as a depletion of high PGS individuals. We suggest using age and sex interactions with the PGS to account for the non-additive effects in disease prediction to further increase the number of future cases identified. To predict future CAD events, the best performing models in this study utilized both clinical and genetic information including interactions -- whether applied as a single model or in a sequential two-step process. Moreover, CAD prediction studies with genetic information should focus on the sex-specific behavior of the predictors and prediction models to account for sex-specific genetic effects and differences in the incidence of CAD events between males and females.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

The authors thank the HUNT and UK Biobank participants for their contributions to research. The authors thank Kuan-Han Wu for his important graphical contributions.

I.S., K.H and C.J.W. designed the study. I.S., S.C.R and B.N.W. analyzed the data. A.H.S., M.E.G. and L.T. contributed to the phenotype harmonization. N.R.S. and W.E.H. provided clinical expertise. I.S., W.E.H., S.C.R., M.I., K.H. and C.J.W. wrote the paper. All the authors read and revised the manuscript.

Sources of Funding:

Cristen J. Willer is supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01-HL127564, R35-HL135824, and R01-HL142023). Ida Surakka is supported by a Precision Health Scholars Award from the University of Michigan Medical School. Scott C. Ritchie is funded by a British Heart Foundation (BHF) Programme Grant (RG/18/13/33946). Nadia R. Sutton is supported by the National Institutes of Health (1K76AG064426-01A1). Michael Inouye is supported by the Munz Chair of Cardiovascular Prediction and Prevention and the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre (BRC-1215-20014) [The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care]. HUNT-MI study, which comprises the genetic investigations of the The Trøndelag Health (HUNT) Study, is a collaboration between investigators from the HUNT study and University of Michigan Medical School and the University of Michigan School of Public Health. The K.G. Jebsen Center for Genetic Epidemiology is financed by Stiftelsen Kristian Gerhard Jebsen; Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) and Central Norway Regional Health Authority. This research has been conducted using the UK Biobank Resource under Application Number 7439. This work was supported by core funding from the: British Heart Foundation (RG/13/13/30194; RG/18/13/33946), Cambridge British Heart Foundation (BHF) Centre of Research Excellence (RE/13/6/30180) and NIHR Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre (BRC-1215-20014) [The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care]. This work was also supported by Health Data Research UK, which is funded by the UK Medical Research Council, Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council, Economic and Social Research Council, Department of Health and Social Care (England), Chief Scientist Office of the Scottish Government Health and Social Care Directorates, Health and Social Care Research and Development Division (Welsh Government), Public Health Agency (Northern Ireland), British Heart Foundation and Wellcome.

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms:

- ASCVD

Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease

- Harrell’s C-index, referred to as C-index throughout the study

Concordance index

- CAD

Coronary artery disease

- HRs

Hazard ratios

- PCE

Pooled Cohort Equation

- PGS

polygenic score

- HUNT

Trøndelag Health Study

- UK Biobank

United Kingdom Biobank

Footnotes

Disclosures: Cristen J Willer’s spouse works for Regeneron Pharmaceuticals. Nadia R Sutton serves on advisory committees for Cordis and Philips and has received honoraria for speaking from Zoll and Cordis. All other authors have nothing to disclose.

References:

- 1.GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2020;396:1204–1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goff DC Jr., Lloyd-Jones DM, Bennett G, Coady S, D’Agostino, Gibbons R, Greenland P, Lackland DT, Levy D, O’Donnell CJ et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the assessment of cardiovascular risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;63:2935–2959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Piepoli MF, Hoes AW, Agewall S, Albus C, Brotons C, Catapano AL, Cooney MT, Corrà U, Cosyns B, Deaton C et al. 2016 European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: The Sixth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice (constituted by representatives of 10 societies and by invited experts)Developed with the special contribution of the European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation (EACPR). Eur Heart J. 2016;37:2315–2381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hippisley-Cox J, Coupland C, Robson J and Brindle P. Derivation, validation, and evaluation of a new QRISK model to estimate lifetime risk of cardiovascular disease: cohort study using QResearch database. BMJ 2010;341:c6624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anderson KM, Wilson PW, Odell PM and Kannel WB. An updated coronary risk profile. A statement for health professionals. Circulation 1991;83:356–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Selmer R, Lindman AS, Tverdal A, Pedersen JI, Njølstad I, Veierød MB. [Model for estimation of cardiovascular risk in Norway]. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen 2008;128:286–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Damen JA, Pajouheshnia R, Heus P, Moons KGM, Reitsma JB, Scholten RJPM, Hooft L and Debray TPA. Performance of the Framingham risk models and pooled cohort equations for predicting 10-year risk of cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med 2019;17:109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wekesah FM, Mutua MK, Boateng D, Grobbee DE, Asiki G, Kyobutungi CK and Klipstein-Grobush K. Comparative performance of pooled cohort equations and Framingham risk scores in cardiovascular disease risk classification in a slum setting in Nairobi Kenya. Int J Cardiol Heart Vasc. 2020;28:100521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Siontis GC, Tzoulaki I, Siontis KC and Ioannidis JP. Comparisons of established risk prediction models for cardiovascular disease: systematic review. BMJ 2012;344:e3318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sun L, Pennells L, Kaptoge S, Nelson CP, Ritchie SC, Abraham G, Arnold M, Bell S, Bolton T, Burgess S et al. Polygenic risk scores in cardiovascular risk prediction: A cohort study and modelling analyses. PLoS Med. 2021;18:e1003498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khera AV, Chaffin M, Aragam KG, Haas ME, Roselli C, Choi SH, Natarajan P, Lander ES, Lubitz SA, Ellinor PT et al. Genome-wide polygenic scores for common diseases identify individuals with risk equivalent to monogenic mutations. Nat Genet 2018;50:1219–1224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Inouye M, Abraham G, Nelson CP, Wood AM, Sweeting MJ, Dudbridge F, Lai FY, Kaptoge S, Brozynska M, Wang T et al. Genomic Risk Prediction of Coronary Artery Disease in 480,000 Adults: Implications for Primary Prevention. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72:1883–1893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elliott J, Bodinier B, Bond TA, Chadeau-Hyam M, Evangelou E, Moons KGM, Dehghan A, Muller DC, Elliott P and Tzoulaki I. Predictive Accuracy of a Polygenic Risk Score-Enhanced Prediction Model vs a Clinical Risk Score for Coronary Artery Disease. JAMA 2020;323:636–645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mars N, Koskela JT, Ripatti P, Kiiskinen TTJ, Havulinna AS, Lindbohm JV, Ahola-Olli A, Kurki M, Karjalainen J, Palta P et al. Polygenic and clinical risk scores and their impact on age at onset and prediction of cardiometabolic diseases and common cancers. Nat Med. 2020;26:549–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mega JL, Stitziel NO, Smith JG, Chasman DI, Caulfield M, Devlin JJ, Nordio F, Hyde C, Cannon CP, Sacks F et al. Genetic risk, coronary heart disease events, and the clinical benefit of statin therapy: an analysis of primary and secondary prevention trials. Lancet 2015;385:2264–2271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tada H, Melander O, Louie JZ, Catanese JJ, Rowland CM, Devlin JJ, Kathiresan S and Shiffman D. Risk prediction by genetic risk scores for coronary heart disease is independent of self-reported family history. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:561–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abraham G, Havulinna AS, Bhalala OG, Byars SG, De Livera AM, Yetukuri L, Tikkanen E, Perola M, Schunkert H, Sijbrands EJ et al. Genomic prediction of coronary heart disease. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:3267–3278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khera AV and Kathiresan S. Genetics of coronary artery disease: discovery, biology and clinical translation. Nat Rev Genet. 2017;18:331–344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang Y, Hui Q, Gwinn M, Hu YJ, Quyyumi AA, Vaccarino V and Sun YV. Sexual Differences in Genetic Predisposition of Coronary Artery Disease. Circ Genom Precis Med. 2021;14:e003147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pechlivanis S, Lehmann N, Hoffmann P, Nöthen MM, Jöckel KH, Erbel R and Moebus S. Risk prediction for coronary heart disease by a genetic risk score - results from the Heinz Nixdorf Recall study. BMC Med Genet. 2020;21:178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hajek C, Guo X, Yao J, Hai Y, Johnson WG, Frazier-Wood AC, Post WS, Psaty BM, Taylor KD and Rotter JI. Coronary Heart Disease Genetic Risk Score Predicts Cardiovascular Disease Risk in Men, Not Women. Circ Genom Precis Med. 2018;11:e002324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.El Khoudary SR, Aggarwal B, Beckie TM, Hodis HN, Johnson AE, Langer RD, Limacher MC, Manson JE, Stefanick ML, Allison MA et al. Menopause Transition and Cardiovascular Disease Risk: Implications for Timing of Early Prevention: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2020;142:e506–e532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jiang X, Holmes C and McVean G. The impact of age on genetic risk for common diseases. PLoS Genet. 2021;17:e1009723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baart SJ, Dam V, Scheres LJJ, Damen JAAG, Spijker R, Schuit E, Debray TPA, Fauser BCJM, Boersma E, Moons KGM et al. Cardiovascular risk prediction models for women in the general population: A systematic review. PLoS One 2019;14:e0210329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martin AR, Kanai M, Kamatani Y, Okada Y, Neale BM and Daly MJ. Clinical use of current polygenic risk scores may exacerbate health disparities. Nat Genet. 2019;51:584–591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wolford BN, Surakka I, Ritchie SC, Lambert S, Nielsen JB, Skogholt A, Gabrielsen ME, Brumpton B, Jonasson C, Hveem K et al. Comprehensive benchmarking of integrated polygenic and conventional risk factor models for cardiovascular traits in the Nord-Trøndelag Health Study. (Abstract/1128). Presented at the 70th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Human Genetics, Oct 28th, 2020, Virtual [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krokstad S, Langhammer A, Hveem K et al. Cohort Profile: the HUNT Study, Norway. International journal of epidemiology 2013;42:968–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhou W, Fritsche LG, Das S et al. Improving power of association tests using multiple sets of imputed genotypes from distributed reference panels. Genetic epidemiology 2017;41:744–755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nikpay M, Goel A, Won HH et al. A comprehensive 1,000 Genomes-based genome-wide association meta-analysis of coronary artery disease. Nature genetics 2015;47:1121–1130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sudlow C, Gallacher J, Allen N et al. UK biobank: an open access resource for identifying the causes of a wide range of complex diseases of middle and old age. PLoS medicine 2015;12:e1001779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Inouye M, Abraham G, Nelson CP et al. Genomic Risk Prediction of Coronary Artery Disease in 480,000 Adults: Implications for Primary Prevention. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2018;72:1883–1893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eckel RH, Jakicic JM, Ard JD et al. 2013 AHA/ACC guideline on lifestyle management to reduce cardiovascular risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2014;63:2960–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Khera R, Pandey A, Ayers CR et al. Performance of the Pooled Cohort Equations to Estimate Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease Risk by Body Mass Index. JAMA network open 2020;3:e2023242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Albarqouni L, Doust JA, Magliano D, Barr EL, Shaw JE, Glasziou PP. External validation and comparison of four cardiovascular risk prediction models with data from the Australian Diabetes, Obesity and Lifestyle study. The Medical journal of Australia 2019;210:161–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2019;73:e285–e350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.