Abstract

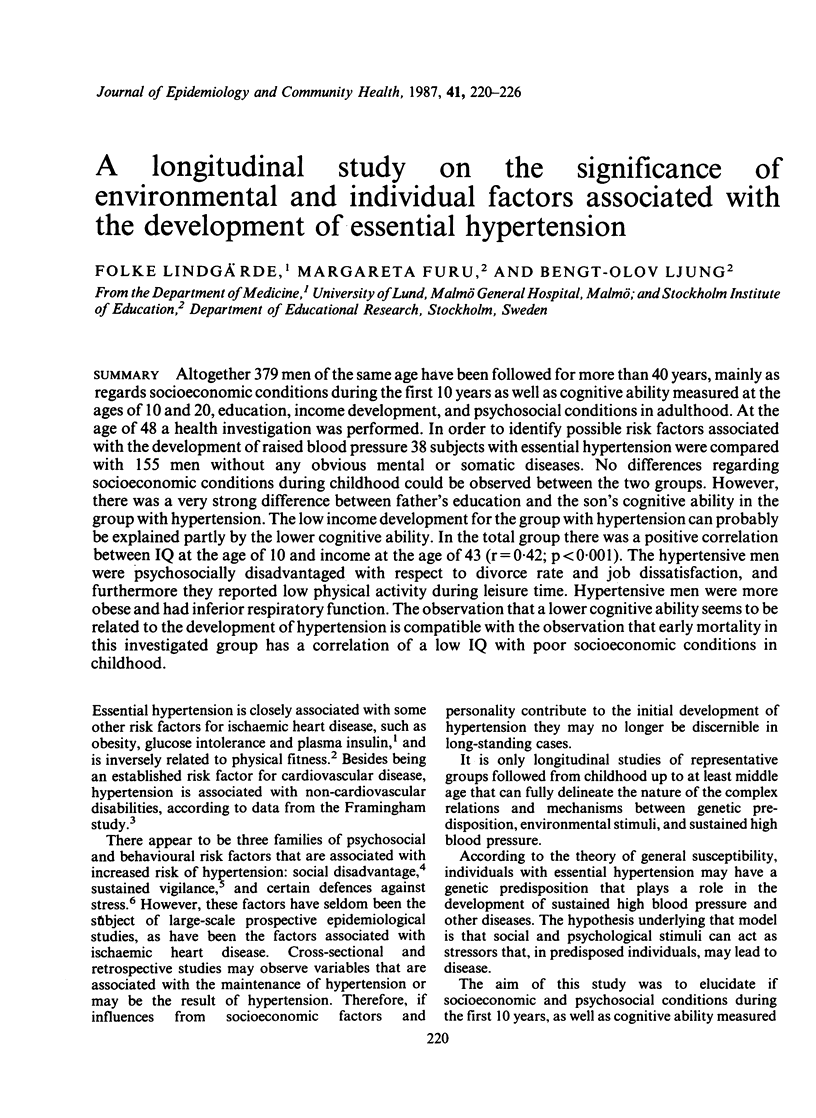

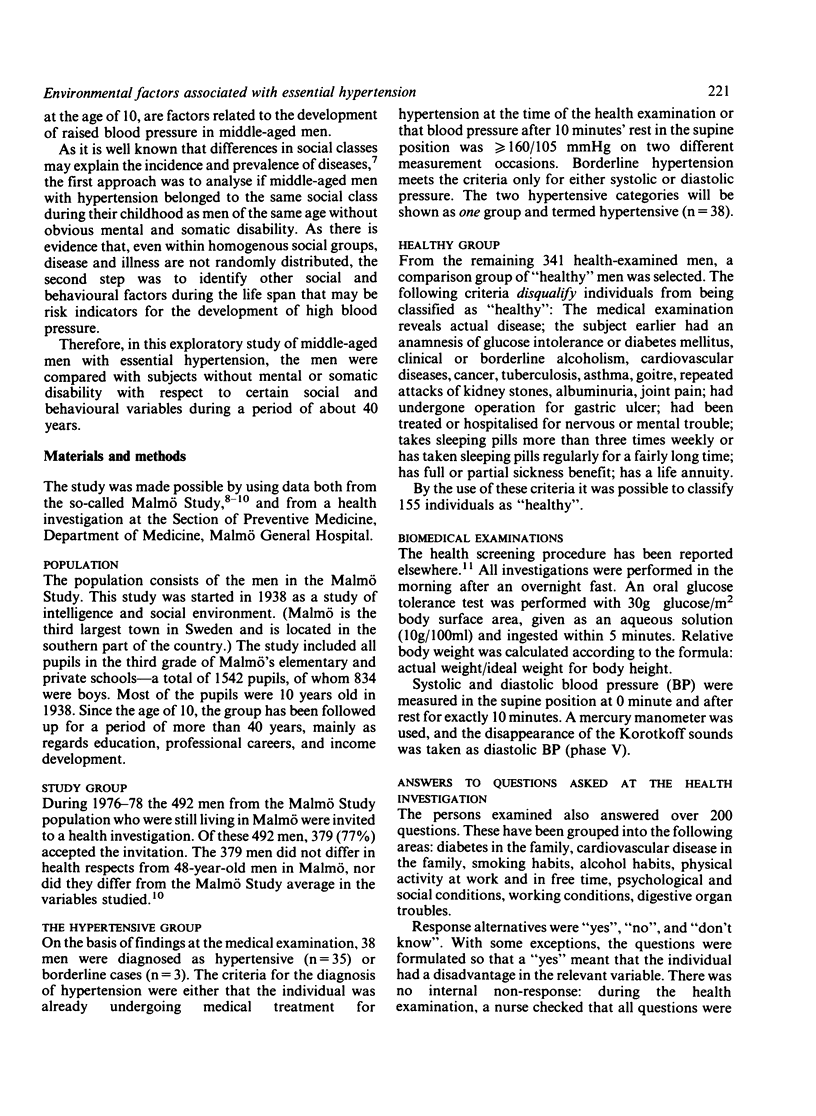

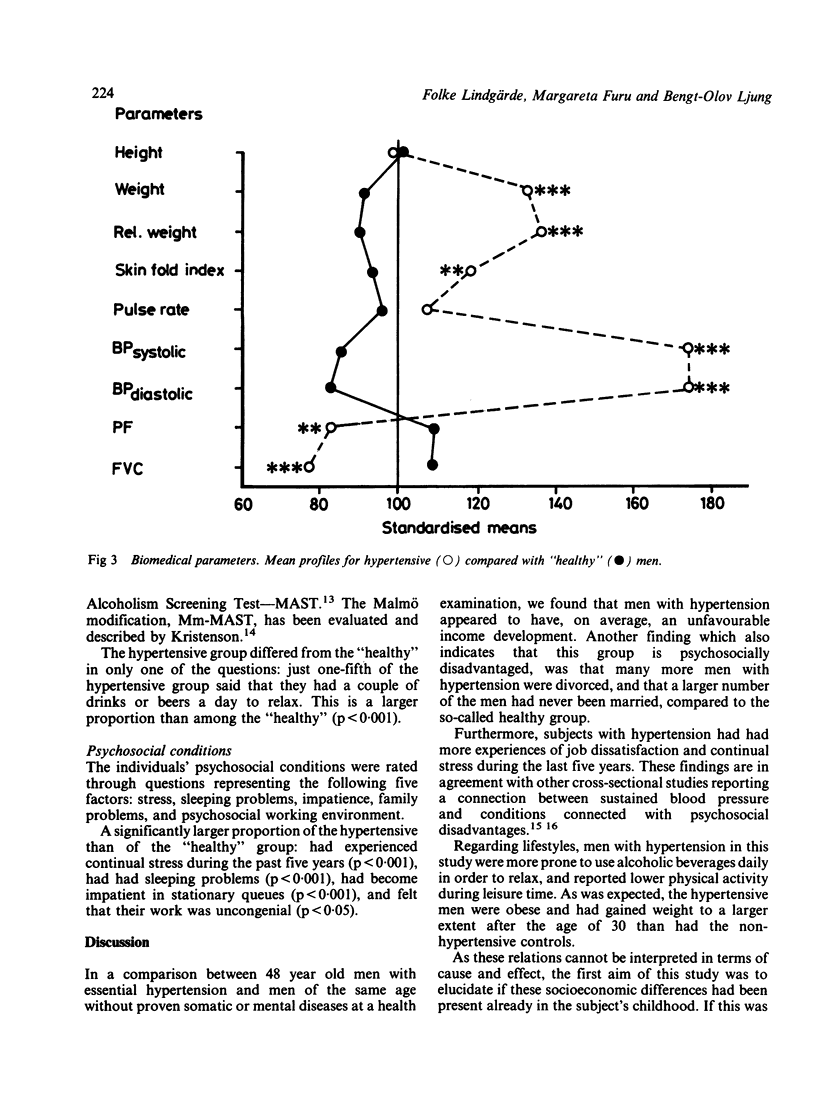

Altogether 379 men of the same age have been followed for more than 40 years, mainly as regards socioeconomic conditions during the first 10 years as well as cognitive ability measured at the ages of 10 and 20, education, income development, and psychosocial conditions in adulthood. At the age of 48 a health investigation was performed. In order to identify possible risk factors associated with the development of raised blood pressure 38 subjects with essential hypertension were compared with 155 men without any obvious mental or somatic diseases. No differences regarding socioeconomic conditions during childhood could be observed between the two groups. However, there was a very strong difference between father's education and the son's cognitive ability in the group with hypertension. The low income development for the group with hypertension can probably be explained partly by the lower cognitive ability. In the total group there was a positive correlation between IQ at the age of 10 and income at the age of 43 (r = 0.42; p less than 0.001). The hypertensive men were psychosocially disadvantaged with respect to divorce rate and job dissatisfaction, and furthermore they reported low physical activity during leisure time. Hypertensive men were more obese and had inferior respiratory function. The observation that a lower cognitive ability seems to be related to the development of hypertension is compatible with the observation that early mortality in this investigated group has a correlation of a low IQ with poor socioeconomic conditions in childhood.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Antonovsky A. Social class, life expectancy and overall mortality. Milbank Mem Fund Q. 1967 Apr;45(2):31–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair S. N., Goodyear N. N., Gibbons L. W., Cooper K. H. Physical fitness and incidence of hypertension in healthy normotensive men and women. JAMA. 1984 Jul 27;252(4):487–490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borkan G. A., Sparrow D., Wisniewski C., Vokonas P. S. Body weight and coronary disease risk: patterns of risk factor change associated with long-term weight change. The Normative Aging Study. Am J Epidemiol. 1986 Sep;124(3):410–419. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyer A. R., Stamler J., Shekelle R. B., Schoenberger J. The relationship of education to blood pressure: findings on 40,000 employed Chicagoans. Circulation. 1976 Dec;54(6):987–992. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.54.6.987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harburg E., Erfurt J. C., Chape C., Hauenstein L. S., Schull W. J., Schork M. A. Socioecological stressor areas and black-white blood pressure: Detroit. J Chronic Dis. 1973 Sep;26(9):595–611. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(73)90064-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasl S. V., Cobb S. Blood pressure changes in men undergoing job loss: a preliminary report. Psychosom Med. 1970 Jan-Feb;32(1):19–38. doi: 10.1097/00006842-197001000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keil J. E., Tyroler H. A., Sandifer S. H., Boyle E., Jr Hypertension: effects of social class and racial admixture: the results of a cohort study in the black population of Charleston, South Carolina. Am J Public Health. 1977 Jul;67(7):634–639. doi: 10.2105/ajph.67.7.634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmot M. G., Rose G., Shipley M., Hamilton P. J. Employment grade and coronary heart disease in British civil servants. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1978 Dec;32(4):244–249. doi: 10.1136/jech.32.4.244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmot M. G., Shipley M. J., Rose G. Inequalities in death--specific explanations of a general pattern? Lancet. 1984 May 5;1(8384):1003–1006. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)92337-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modan M., Halkin H., Almog S., Lusky A., Eshkol A., Shefi M., Shitrit A., Fuchs Z. Hyperinsulinemia. A link between hypertension obesity and glucose intolerance. J Clin Invest. 1985 Mar;75(3):809–817. doi: 10.1172/JCI111776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris J. N., Chave S. P., Adam C., Sirey C., Epstein L., Sheehan D. J. Vigorous exercise in leisure-time and the incidence of coronary heart-disease. Lancet. 1973 Feb 17;1(7799):333–339. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(73)90128-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinsky J. L., Branch L. G., Jette A. M., Haynes S. G., Feinleib M., Cornoni-Huntley J. C., Bailey K. R. Framingham Disability Study: relationship of disability to cardiovascular risk factors among persons free of diagnosed cardiovascular disease. Am J Epidemiol. 1985 Oct;122(4):644–656. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selzer M. L. The Michigan alcoholism screening test: the quest for a new diagnostic instrument. Am J Psychiatry. 1971 Jun;127(12):1653–1658. doi: 10.1176/ajp.127.12.1653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trell E. Community-based preventive medical department for individual risk factor assessment and intervention in an urban population. Prev Med. 1983 May;12(3):397–402. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(83)90248-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuomilehto J., Puska P., Virtamo J., Neittaanmäki L., Koskela K. Coronary risk factors and socioeconomic status in Eastern Finland. Prev Med. 1978 Dec;7(4):539–549. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(78)90266-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]