Abstract

Objective.

To establish conditions for effective hypothalamic suppression in normal and high BMI women and test the hypothesis that intravenous administration of pulsatile recombinant FSH (rFSH) can overcome the clinically evident dysfunctional pituitary-ovarian axis in women with obesity.

Design.

Prospective interventional study.

Setting.

Academic Medical Center.

Participants.

Twenty-seven normal weight women and 27 women with obesity, eumenorrheic, ages 21-39 years.

Intervention.

Two-day frequent blood sampling study, in early follicular phase, before and after cetrorelix suppression of gonadotropins and exogenous pulsatile intravenous (IV) rFSH administration.

Main Outcome Measure(s).

Serum inhibin B and estradiol levels (basal and rFSH stimulated).

Results.

A modified GnRH antagonism protocol effectively suppressed production of endogenous gonadotropins in women of normal and high BMI, providing a model to address the functional role of FSH in the hypothalamic-pitutary-ovarian axis. Intravenous rFSH treatment resulted in equivalent serum levels and pharmacodynamics in normal weight women and those with obesity. However, women with obesity exhibited reduced basal levels of inhibin B and estradiol and a significantly decreased response to FSH stimulation. BMI was inversely correlated with serum inhibin B and estradiol. In spite of this observed deficit in ovarian function, pulsatile intravenous rFSH treatment in women with obesity, resulted in levels of estradiol and inhibin B comparable to those observed in normal weight women, in the absence of exogenous FSH stimulation.

Conclusions.

Despite normalization of FSH levels and pulsatility by exogenous intravenous administration, women with obesity demonstrate ovarian dysfunction with respect to estradiol and inhibin B secretion. Pulsatile FSH can partially correct the relative hypogonadotropic hypogonadism of obesity, thereby providing a potential treatment strategy to mitigate some of the adverse effects of high BMI on fertility, assisted reproduction and pregnancy outcomes.

Keywords: obesity, infertility, ovary, gonadotropins, cetrorelix

Capsule:

Women with obesity exhibit ovarian dysfunction, with respect to FSH-stimulated estradiol and inhibin B secretion, which can be partially overcome by IV rFSH administration.

Introduction

The association between obesity and reduced reproductive fitness is well documented but the mechanisms are poorly understood (1, 2). Much less attention has been paid to infertility and poor response to treatment in women with obesity and regular, ovulatory cycles, compared to those women with obesity and PCOS. Several studies have documented low gonadotropin and ovarian hormone levels among women with obesity (3–5). Overweight women had lower follicular serum follicle stimulating hormone (FSH), luteinizing hormone (LH) and inhibin B levels compared to normal weight women but no differences in estradiol (E2) or follicle counts (3), while the Nurse’s Health Study observed lower serum E2 levels associated with obesity (5). Similarly, decreased urinary FSH, LH, and progesterone metabolites were seen in women with obesity (4). In women with infertility and obesity, a higher dose of exogenous gonadotropin is needed to achieve adequate ovarian stimulation (6, 7) and an increase in body mass index (BMI) negatively impacts outcomes (oocyte retrieval, clinical pregnancy, live birth and miscarriage) in women undergoing in vitro fertilization (IVF) (8–10). These findings suggest that both pituitary and ovarian dysfunction may be implicated in the evident adverse effects of obesity on fertility and fecundity (11).

FSH and LH stimulate ovarian follicular development. Obesity is associated with reduced LH pulse amplitude with no change in frequency, however, less is known regarding FSH secretion and activity (12). While both FSH and LH are secreted in a pulsatile manner in humans, the role of FSH is not well characterized (13). Transgenic mouse models have demonstrated that re-routed FSH (secreted via the pulsatile LH pathway) enhances ovarian function and fertility (14). Currently, there are no standardized human models to delineate and study the specific effects of FSH, particularly in women with obesity.

Exogenous FSH can be utilized to investigate its pulsatile effects on the ovary in women with obesity. However, subcutaneous dosing must be individualized based on BMI due to variable absorption rates of FSH (6). Intravenous (IV) administration of exogenous FSH represents a potential strategy to circumvent this limitation by ensuring more predictable systemic delivery. Confounding effects of endogenous gonadotropin secretion, in the context of exogenous FSH, can be suppressed by administration of a GnRH antagonist. Considering the previously reported phenomenon of premature escape from GnRH antagonist suppression in women with obesity (15), we developed and implemented a modified ‘booster’ strategy to enforce endogenous suppression in all study participants.

We hypothesized that the relative hypogonadotropic hypogonadism and consequent decreased reproductive fitness characteristic of obesity is due to pituitary dysfunction, which would be rescued by pulsatile exogenous FSH treatment. Herein, we report a novel model to investigate the specific effects of pulsatile IV recombinant FSH (rFSH), in women of normal weight or with obesity, following suppression of endogenous LH and FSH secretion with the GnRH antagonist cetrorelix. Specifically, effects of IV rFSH on the relative hypogonadal phenotype characteristic of women with obesity were examined with respect to FSH-stimulation of E2 and inhibin secretion.

Materials and Methods

Participants

The study was approved by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board (15-0474) and registered on Clinicaltrials.gov (NCT02478775). Informed consent was obtained prior to enrollment and participants were compensated.

54 women with normal BMI (n=27) or high BMI (n=27), were recruited from the Denver Metro area between January 2016 and June 2021. All participants underwent a history and physical with screening labs at the Clinical Translational Research Center (CTRC). Inclusion criteria were: age 21-39 years; normal (18.5 kg/m2 – 24.9 kg/m2) or high (≥30 kg/m2) BMI; regular menses (25-40 days); normal prolactin, thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH), complete metabolic panel and blood count; no history or clinical diagnosis of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), no chronic disease affecting hormone production, metabolism or clearance; no use of thiazolidinediones or metformin; no current use of medications or supplements containing hormones within three months of entry; less than 4 hours of strenuous exercise per week; not currently pregnant, looking to get pregnant or breast feeding; no significant weight loss or gain (> 2lbs/week) within 3 months.

Study Design

Study design is summarized in Supplemental Fig. 1. The 26-hour study visit was completed in the early follicular phase (days 2-7) of each participant’s menstrual cycle. Visits began at 1:30pm on study day 1 (baseline) with the placement of an in-dwelling IV catheter and a serum pregnancy test prior to the administration of study medications. At 2:00pm frequent blood sampling commenced with 3-4 mL of blood being collected every 10 minutes for 10 hours for measurement of LH, FSH, Inhibin B and estradiol (E2). At midnight (10 hours post study initiation) 3 mg of the GnRH antagonist cetrorelix (EMD Serono, Rockland, MA) was injected subcutaneously in the abdomen and participants were allowed to sleep for 6 hours. At 6:00am on study day 2 (stimulated), a second, subcutaneous, ‘booster’ dose (0.25 mg) of cetrorelix was administered and frequent blood sampling (q10’) for hormone measurements resumed. Additionally, beginning at 6:00 am on study day 2, 30 IU of rFSH was given IV every hour for 10 hours, for a total dose of 300IU.

Hormone Assays

LH, FSH and estradiol (E2) were measured by competitive immunoassay using direct chemiluminescent technology (Advia Centaur CP, Siemens Healthcare Diagnostic, Tarrytown, NY; AB_2895592, AB_28955593 and AB_2895133, respectively). Inter- and intra-assay coefficients of variation (CVs) were 3.99% and 2.89%; for LH; 4 .44% and 5.11% for FSH, and 3.25% and 2.67% for E2, respectively. Inhibin B and anti-mullerian hormone (AMH) were measured by ELISA (Ansh Labs, Webster, TX; AB_2783661 and AB_2783675). Inter- and intra-assay CVs were 1.9% and 4.98 for inhibin B and 2.5% and 4.25% for AMH, respectively.

Mass Spectrometry measurement of cetrorelix

Serum cetrorelix concentrations were determined by LC/MS-MS (Applied Biosystems Sciex 4000) as described (Supplemental Methods). Limit of detection was 1.22 ng/mL.

Pharmacokinetic analysis of serum FSH

FSH concentration-time data was subjected to non-compartmental analysis, by the linear trapezoidal-linear interpolation method with uniform weighting, using Phoenix® WinNonlin® v8.3.3 (Certara L.P., Princeton, NJ), to obtain predicted values for total exposure, clearance and volume of distribution at steady state.

Statistical Analysis

An a priori sample size estimate using the reported difference (30pg/ml) in inhibin B levels between women of normal weight and with obesity (3), with an alpha of 0.05 was performed, resulting in 80% power with 27 women in each group. Differences between groups and/or study days were tested with two-sample paired t-tests for continuous variables and Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables. Two-sample t tests and linear regressions were only used as analysis methods when we included one observation per person in a model. Linear regression was used to adjust BMI group differences for age, cycle day and AMH. Outcome distributions and model diagnostic plots confirmed that parametric testing was appropriate. Analyses were conducted in R version 4.2.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria)

Results

Participant characteristics

54 participants were included in the study, with equal cohorts of women with normal and high BMI, as outlined in the Consort Diagram (Supplemental Fig. 2). Baseline demographic and hormonal characteristics of participants are shown in Table 1. By design, BMI and weight, were statistically different between the two cohorts. Women of normal BMI were younger (age 27 vs 32, p<0.001) and had a lower average TSH level, compared to women with high BMI. However, all women in the study were euthyroid, with normal TSH, and of reproductive age with regular menstrual cycles. There were no significant differences in other parameters, including waist:hip ratio, prolactin, AMH or cycle length.

Table 1:

Demographic data are summarized for the 54 participants. Continuous variables are summarized with means (standard deviations), and differences between groups are tested with two-sample t-tests. Categorical variables are summarized with frequencies (percentages) and associations are tested with Fisher’s exact test.

| Characteristic | Normal BMI | High BMI | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 27 | 27 | |

| Age (years) | 27.3 (4.8) | 32.0 (4.1) | <0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.5 (1.4) | 37.7 (6.2) | <0.001 |

| Weight (kg) | 61.2 (5.5) | 102.0 (19.3) | <0.001 |

| Height (cm) | 164.9 (6.3) | 164.3 (5.6) | 0.675 |

| Waist/hip ratio | 0.84 (0.12) | 0.90 (0.12) | 0.082 |

| TSH (μIU/mL) | 1.51 (0.87) | 2.15 (1.13) | 0.024 |

| Prolactin (ng/mL) | 8.15 (3.66) | 9.74 (4.68) | 0.172 |

| AMH (ng/mL) | 6.16 (5.64) | 6.31 (4.31) | 0.848 |

| Cycle Length (days) | 28.22 (1.5) | 28.39 (1.23) | 0.67 |

| Cycle Day of Visit | 5.0 (1.5) | 4.2 (1.3) | 0.054 |

Baseline endogenous FSH and LH secretion

Mean endogenous serum FSH and LH levels at each sampling interval (Study Day 1) are shown in Fig. 1. Consistent with our previous studies (16–18), participants with high BMI exhibited significantly lower levels of LH (Fig. 1A) compared to their normal BMI counterparts. Area under the curve (AUC) and mean levels ± SEM of LH for normal BMI (2942 ± 180.4 and 4.78 ± 0.21 mIU/mL, respectively) were significantly different from high BMI (2300 ± 164.8 and 3.95 ± 0.16 mIU/mL, respectively; p<0.0001 for both). Levels of serum FSH (AUC) in normal BMI women were not significantly different from those in the high BMI group (p=0.21).

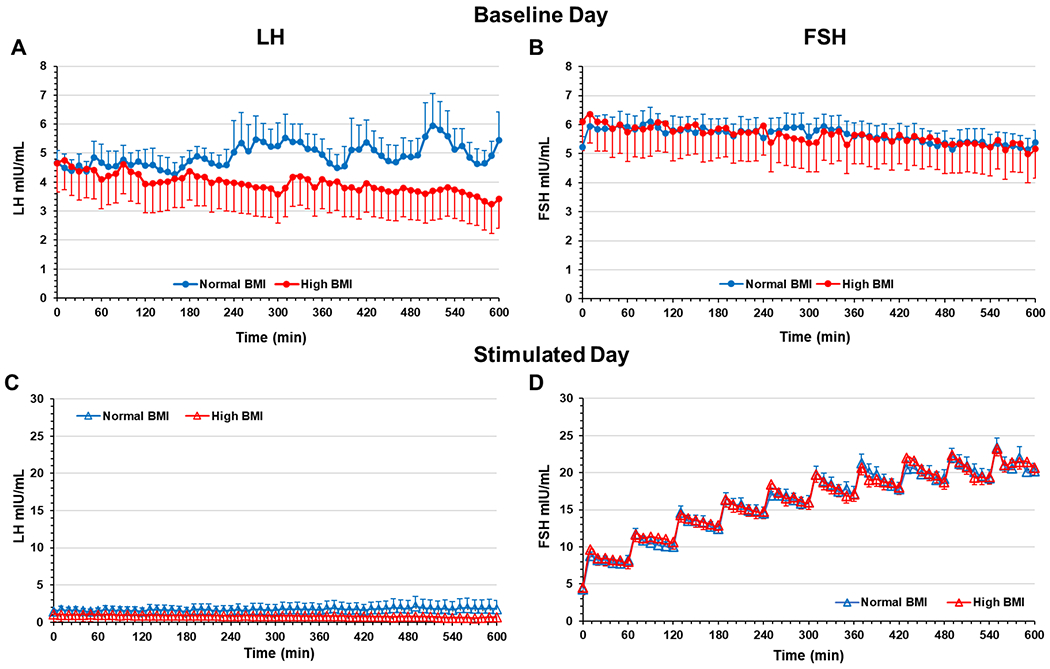

Fig. 1:

Serum LH and FSH (sampled q 10’) on the baseline study day 1 (A and B) and stimulated study day 2 (C and D) in normal and high BMI groups. Exogenous IV rFSH was administered every 60 min for 10 hours as indicated by the observed peaks in the serum FSH levels. Data are mean of 27 participants per group; error bars are standard error of the mean.

Pulsatile Exogenous rFSH Profiles and Pharmacokinetics

Treatment with the GnRH antagonist cetrorelix, using our modified ‘booster’ strategy, effectively suppressed LH levels in both normal weight and women with obesity for the duration of study day 2 (Fig. 1C). Subsequent IV administration of hourly boluses of rFSH produced a pulsatile pattern and elevated serum FSH concentrations in both normal and high BMI groups (Fig. 1D). There was no statistical difference in AUC between the cohorts for LH (p=0.49) or FSH (p=0.86). Thus, pulsatile IV rFSH treatment resulted in comparable serum levels, pulse amplitude and frequency in normal and high BMI women.

We next examined the pharmacokinetics of serum FSH, during study day 2, using standard non-compartmental methodology. There was no difference in clearance of serum FSH or volume of distribution at steady state between the normal and high BMI groups (Supplemental Fig. 3). In addition, there were no significant differences in urinary concentrations of FSH between normal and high BMI women, indicating similar FSH clearance (data not shown).

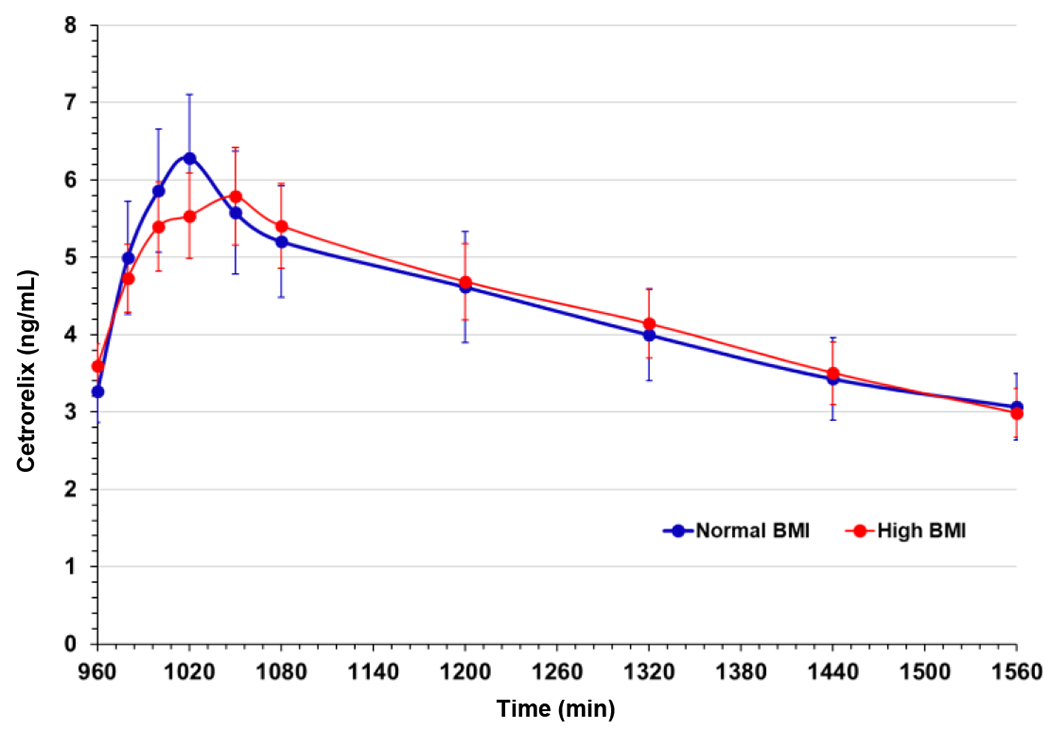

We also determined cetrorelix levels, by mass spectrometry analysis, in serum from baseline and FSH stimulated days. Serum cetrorelix levels on study day 2 peaked approximately one hour after the booster dose, and declined slowly thereafter (Fig. 2). No differences in serum cetrorelix profiles were observed between the normal and high BMI groups. Thus, using a supplemental booster dose of cetrorelix resulted in similar pharmacokinetics in both normal and high BMI women, and effective functional suppression of LH was maintained in both cohorts for the duration of study day 2 (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 2:

Serum cetrorelix levels determined at the indicated time points by mass spectrometry (Supplemental methods). Data are means of 27 participants per group; error bars are standard error of the mean.

Effects of obesity on ovarian response to pulsatile IV rFSH

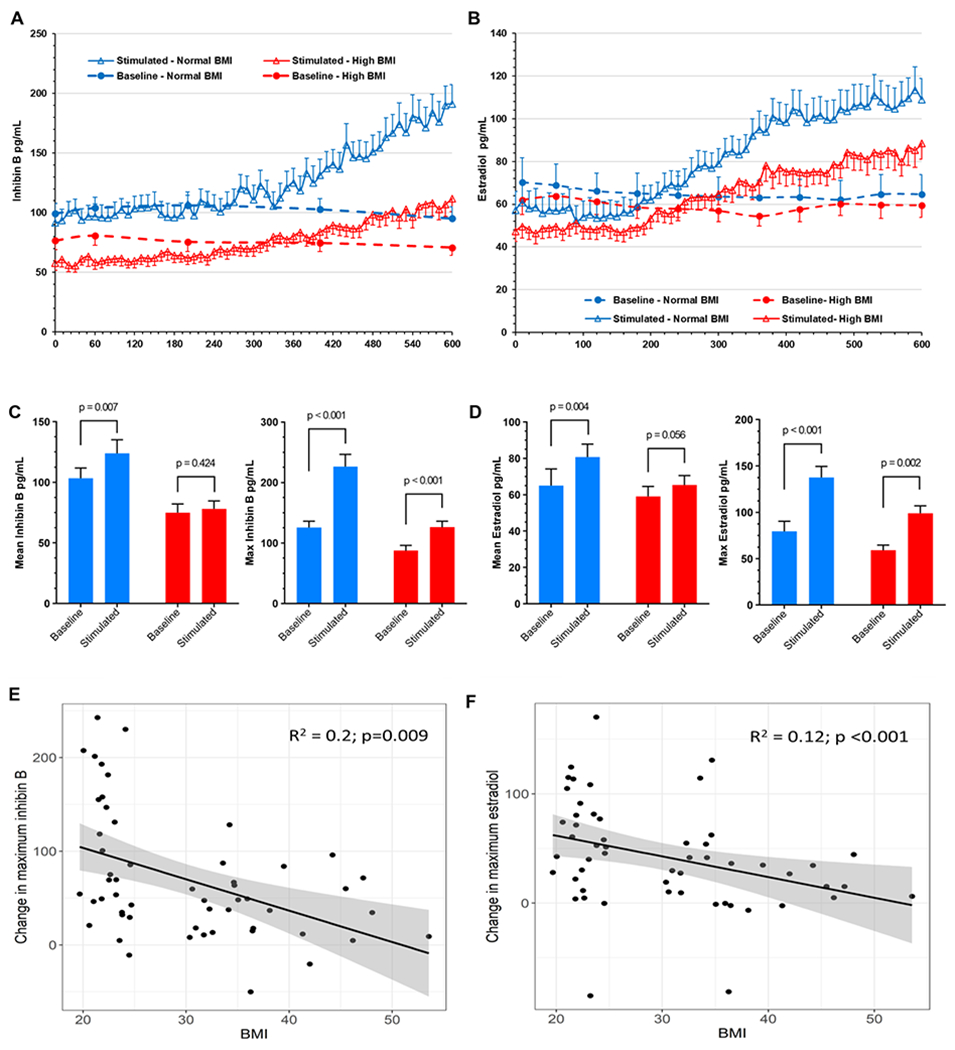

Baseline levels of inhibin B (Fig. 3A) and E2 (Fig. 3B) were significantly lower in women of high BMI. Inhibin B levels (AUC) were 61524 ± 10661 for normal BMI and 43581 ± 9088 for high BMI (p<0.0001). Similarly, E2 AUCs in normal versus high BMI women were 36932 ± 5694 and 34589 ± 3933, respectively (p=0.008). Pulsatile administration of rFSH increased serum inhibin B (Fig. 3A) and E2 (Fig. 3B) levels, above the baseline averages, for both the normal and high BMI groups. However, rFSH induction of both inhibin B and E2 was significantly attenuated in the high BMI group. Mean and maximum inhibin B and E2 levels increased in response to pulsatile rFSH administration from study day 1 to study day 2 within each cohort (Fig 3C & D). The difference in mean E2 was statistically significant for the normal BMI group (p= 0.004) but not for the high BMI group (p=0.056). The increase in maximum E2 between baseline and stimulated day, in response to FSH, is significant for both cohorts (p<0.001 for both). Changes in maximum inhibin B response to rFSH were significant in normal and high BMI groups (both p<0.001). Mean inhibin B was also increased in both cohorts from study day 1 to study day 2, but is only significant in women with normal BMI (p=0.007).

Fig. 3:

Serum inhibin B (A) and estradiol (B) levels in normal and high BMI during the baseline (dashed lines) and the stimulated days (solid lines). Inhibin B and estradiol were measured at the indicated 5 timepoints on study day 1 and every 10 minutes on study day 2. (C) Inhibin B and (D) estradiol mean and maximum levels on baseline and FSH-stimulated days, in normal and high BMI groups. Data are means of 27 participants per group; error bars are standard error of the mean. Change in the difference between the baseline and FSH-stimulated maximum estradiol (E) and inhibin B (F) plotted against participant’s BMI. Shaded area indicates 95% confidence intervals.

Analysis of the differences in maximum inhibin B and E2 levels (pg/ml) between baseline and stimulated days shows significantly decreased responses to FSH for inhibin B (−62.1 (95% CI: −94.1, −30.0), p<0.001) and E2 (−31.8 (95%CI: −56.5, −7.1), p=0.013) in the high BMI group compared to the normal BMI group. These differences remained significant after adjusting for age, cycle day, and AMH levels (−54.7 (95%CI: −89.1, −20.3), p=0.002 for inhibin B and −32.7 (95%CI: −60.7, −4.7), p=0.023 for E2). Thus, despite similar FSH levels, pulse amplitude and frequency, in both normal and high BMI groups (Fig 1D), FSH-induced increases in both E2 and inhibin levels were significantly attenuated in women with high BMI. However, we note that, in response to pulsatile IV rFSH treatment, day 2 serum E2 (99.1±8) and inhibin B (126.3±10) in the high BMI women did achieve levels (pg/ml ± sem) comparable to those observed, at baseline (79.3±11.1 and 125.7±11.1, respectively), in the normal BMI group (Fig 3).

Relationship between degree of obesity and ovarian response

We next examined the relationship between BMI and change in the maximum inhibin B and E2 levels between baseline and the FSH-stimulated days (Fig. 3E & F). A significant correlation was observed between BMI and the change in maximum E2 (R2 012, p<0.001) and inhibin B (R2 0.20, p=0.009). Linear regression demonstrated a 2.82 pg/ml (95%CI: −4.68, −0.96, p=0.004) decrease in maximum inhibin B response to FSH (stimulated-baseline) for every unit increase in BMI, adjusted for age, cycle day, and AMH. Similarly, a 1.71 pg/ml (95%CI: −3.21, −0.20 p=0.027) adjusted decrease in maximum E2 response to FSH, per unit increase in BMI was observed.

Discussion

We have developed an in vivo model to address the specific role of FSH in the female hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis and examined the effects of pulsatile exogenous FSH on reproductive hormones in obese compared to normal weight women. Multiple prior studies have characterized obesity as a state of relative hypogonadotropic hypogonadism with decreased levels of gonadotropins, an attenuated response to GnRH stimulation (16–19) and lower levels of progesterone, E2 and their urinary metabolites (3, 12, 20) . In addition, women with obesity undergoing IVF require higher gonadotropin doses and longer stimulation time, yet still exhibit lower oocyte yield and quality (21) and adverse changes in the follicular environment (22). Similarly, animal models of obesity have shown smaller oocyte size, ovarian mitochondrial dysfunction, increased endoplasmic reticulum stress markers, and elevated relative oxygen species (21). Our study demonstrates that, while pulsatile intravenous rFSH can compensate for the deficit in pituitary gonadotropin secretion and improve ovarian response in women with obesity, there remains a state of relative ovarian dysfunction that is exacerbated by increasing BMI in this model.

Lower exogenous FSH absorption in obese women is well documented for subcutaneous and intramuscular administration (23, 24). We attempted to correct these abnormal FSH pharmacodynamics in obese women and the observed deficit in FSH secretion (3, 12, 17, 18) by superimposing pulsatile exogenous IV rFSH, postulating that it would restore normal inhibin B and E2 levels. We found that, despite achieving equal FSH serum levels and identical pulse amplitude and frequency, women with obesity exhibited lower E2 and inhibin B serum levels, compared to those of normal weight women. These effects were seen in linear regression models even after adjusting for differences in age, cycle day of study, and AMH. Further, inhibin B and E2 response to pulsatile exogenous rFSH were inversely related to BMI. Analysis of the pharmacokinetics of FSH in our study cohort did not find a difference in clearance or volume of distribution that could explain the decreased ovarian response. Thus, our data show that short term pulsatile rFSH does not fully correct the relative hypogonadism characteristic of obesity, indicating a deficit in ovarian response to gonadotropins, in addition to the previously reported pituitary dysfunction (12, 16, 18). However, while women with obesity exhibited a significantly attenuated ovarian response, exogenous IV rFSH administration did result in an increase in inhibin B and E2 producing levels comparable to those of normal weight women at baseline. This suggests that pulsatile rFSH can partially compensate for the observed relative hypogonadotropism of obesity (12, 13, 18) and potentially mitigate for ovarian dysfunction that may underlie the decreased IVF success rates and adverse pregnancy outcomes (6–11).

In considering limitations of our study, we note that the women with obesity were older than their normal weight counterparts. However, both cohorts were of reproductive age, regular cycling, and serum AMH levels were not different. The study protocol was identical for normal and high BMI groups but we acknowledge that diurnal variation in hormones could contribute to observed differences within groups. However, reports of circadian regulation of E2 and gonadotropins are inconsistent and diurnal variation appears minimal in the early follicular phase (25, 26). While small declines in nocturnal LH and FSH secretion have been reported (27), these occurred primarily after midnight, outside of our sampling window. We found no reports of diurnal inhibin variation in women. While we observed increased inhibin B and E2 in response to IV rFSH administration in women with obesity, the levels only reached those of baseline of normal weight women. Thus, there remains a significant impairment in ovarian responsiveness, indicating that acute pulsatile IV FSH cannot fully compensate for the chronic ovarian suppression characteristic of women with obesity under these study conditions. Future studies should consider increasing the duration of rFSH treatment and correlating responses with age, AMH and antral follicle counts (AFC), as indicators of ovarian functional status. It is also possible that higher amplitude gonadotropin pulses and total exposure (in the form of higher IV doses of rFSH, stratified by BMI) may further improve ovarian responsiveness in women with obesity (28). We did not measure AFC, however, it was shown previously that, while women with obesity exhibited lower inhibin B levels, AFC was not significantly different compared to normal weight women. This suggests that ovarian reserve is not impaired in obesity and that the apparent ovarian endocrine dyfunction is not attributable to decreased follicle number. Finally, our study design isolated the effect of FSH on ovarian function by suppressing endogenous gonadotropins and, while LH levels are typically low during the early follicular phase and FSH is primarily responsible for follicular growth and estrogen production, we cannot exclude a complementary, contributary role for LH (29).

Our model utilized a modified cetrorelix protocol since a prior study using the typical 3mg subcutaneous dose, to suppress gonadotropins, observed a rebound in LH in approximately half of women with obesity, but not in normal weight women within 14 hours after cetrorelix administration (15). The obese group exhibited significantly decreased distributional half-life and increased clearance of cetrorelix. Herein, we demonstrate that an additional booster dose, to augment cetrorelix levels, successfully circumvented this possible escape from cetrorelix suppression in women of high BMI. Our results show comparable levels of cetrorelix in both normal and high BMI groups with sustained endogenous LH suppression for the duration of the study. Serum FSH levels were reduced equally in both cohorts to levels consistent with previous observations (30). These data demonstrate that endogenous gonadotropins can be effectively suppressed, in both normal and high BMI women, with appropriate cetrorelix dosing.

In summary, our results demonstrate a significant decrease in ovarian response to FSH in obesity. However, we also show that pulsatile IV rFSH administration can circumvent issues with pharmacokinetics of subcutaneous injection in women with obesity, thereby partially compensating for this intrinsic deficit, resulting in FSH-induced E2 and inhibin levels comparable to those of normal weight women at baseline. The use of FSH pumps to deliver IV pulses, over extended periods with dosing based upon BMI, merits further exploration. Such approaches hold promise for assisted reproductive technology procedures for women with obesity and infertility, to improve oocyte yield, quality and pregnancy outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Attestation Statement:

The subjects in this trial have not concomitantly been involved in other randomized trials.

Data regarding any of the subjects in the study has not been previously published unless specified.

Data will be made available to the editors of the journal for review or query upon request.

Acknowledgments.

The authors acknowledge the assistance of the University of Colorado Clinical Translational Research Center (UL1 RR02578) and thank Dr. Joshua Johnson and Dr. Nanette Santoro (University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus) for critical review of the manuscript. We thank our study participants without whom this research would not have been possible.

Funding Statement:

NIH R01 HD081162 to AJP; NIH K01 OD026526 to LW and NIH R01 AG029531, NIH R01 HD103384 and The Makowski Family Endowment to TRK

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure Statement: The authors have nothing to disclose

Trial Registration: Clinicaltrials.gov # NCT02478775.

Data Sharing Statement:

Restrictions apply to the availability of some or all data generated or analyzed during this study to preserve patient confidentiality. The corresponding author will on request detail the restrictions and any conditions under which access to some data may be provided.

References

- 1.Meldrum DR. Introduction: Obesity and reproduction. Fertil Steril 2017;107:831–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jungheim ES, Travieso JL, Carson KR, Moley KH. Obesity and reproductive function. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am 2012;39:479–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Pergola G, Maldera S, Tartagni M, Pannacciulli N, Loverro G, Giorgino R. Inhibitory effect of obesity on gonadotropin, estradiol, and inhibin B levels in fertile women. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006;14:1954–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Santoro N, Lasley B, McConnell D, Allsworth J, Crawford S, Gold EB et al. Body size and ethnicity are associated with menstrual cycle alterations in women in the early menopausal transition: The Study of Women’s Health across the Nation (SWAN) Daily Hormone Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2004;89:2622–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tworoger SS, Eliassen AH, Missmer SA, Baer H, Rich-Edwards J, Michels KB et al. Birthweight and body size throughout life in relation to sex hormones and prolactin concentrations in premenopausal women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2006;15:2494–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dodson WC, Kunselman AR, Legro RS. Association of obesity with treatment outcomes in ovulatory infertile women undergoing superovulation and intrauterine insemination. Fertil Steril 2006;86:642–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mahutte N, Kamga-Ngande C, Sharma A, Sylvestre C. Obesity and Reproduction. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2018;40:950–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ribeiro LM, Sasaki LMP, Silva AA, Souza ES, Oliveira Lyrio A, A CMGF et al. Overweight, obesity and assisted reproduction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2022;271:117–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bellver J BMI and miscarriage after IVF. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 2022;34:114–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shah DK, Missmer SA, Berry KF, Racowsky C, Ginsburg ES. Effect of obesity on oocyte and embryo quality in women undergoing in vitro fertilization. Obstet Gynecol 2011;118:63–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Silvestris E, de Pergola G, Rosania R, Loverro G. Obesity as disruptor of the female fertility. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 2018;16:22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jain A, Polotsky AJ, Rochester D, Berga SL, Loucks T, Zeitlian G et al. Pulsatile luteinizing hormone amplitude and progesterone metabolite excretion are reduced in obese women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2007;92:2468–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hall JE. Chapter 7 - Neuroendocrine Control of the Menstrual Cycle. In: Barbieri JSaR, ed. Yen and Jaffe’s Reproductive Endocrinology (Eighth Edition) Physiology, Pathophysiology, and Clinical Management, 2019:149–66.e5. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang H, Larson M, Jablonka-Shariff A, Pearl CA, Miller WL, Conn PM et al. Redirecting intracellular trafficking and the secretion pattern of FSH dramatically enhances ovarian function in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014;111:5735–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roth LW, Bradshaw-Pierce EL, Allshouse AA, Lesh J, Chosich J, Bradford AP et al. Evidence of GnRH antagonist escape in obese women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2014;99:E871–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chosich J, Bradford AP, Allshouse AA, Reusch JE, Santoro N, Schauer IE. Acute recapitulation of the hyperinsulinemia and hyperlipidemia characteristic of metabolic syndrome suppresses gonadotropins. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2017;25:553–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McDonald R, Kuhn K, Nguyen TB, Tannous A, Schauer I, Santoro N et al. A randomized clinical trial demonstrating cell type specific effects of hyperlipidemia and hyperinsulinemia on pituitary function. PLoS One 2022;17:e0268323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Santoro N, Schauer IE, Kuhn K, Fought AJ, Babcock-Gilbert S, Bradford AP. Gonadotropin response to insulin and lipid infusion reproduces the reprometabolic syndrome of obesity in eumenorrheic lean women: a randomized crossover trial. Fertil Steril 2021;116:566–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vermeulen A, Kaufman JM, Deslypere JP, Thomas G. Attenuated luteinizing hormone (LH) pulse amplitude but normal LH pulse frequency, and its relation to plasma androgens in hypogonadism of obese men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1993;76:1140–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Al-Safi ZA, Liu H, Carlson NE, Chosich J, Lesh J, Robledo C et al. Estradiol Priming Improves Gonadotrope Sensitivity and Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines in Obese Women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2015;100:4372–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Broughton DE, Moley KH. Obesity and female infertility: potential mediators of obesity’s impact. Fertil Steril 2017;107:840–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Robker RL, Akison LK, Bennett BD, Thrupp PN, Chura LR, Russell DL et al. Obese Women Exhibit Differences in Ovarian Metabolites, Hormones, and Gene Expression Compared with Moderate-Weight Women. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 2009;94:1533–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee MS, Lanes A, Dolinko AV, Bailin A, Ginsburg E. The impact of polycystic ovary syndrome and body mass index on the absorption of recombinant human follicle stimulating hormone. J Assist Reprod Genet 2020;37:2293–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Steinkampf MP, Hammond KR, Nichols JE, Slayden SH. Effect of obesity on recombinant follicle-stimulating hormone absorption: subcutaneous versus intramuscular administration. Fertil Steril 2003;80:99–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klingman KM, Marsh EE, Klerman EB, Anderson EJ, Hall JE. Absence of circadian rhythms of gonadotropin secretion in women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2011;96:1456–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rahman SA, Grant LK, Gooley JJ, Rajaratnam SMW, Czeisler CA, Lockley SW. Endogenous Circadian Regulation of Female Reproductive Hormones. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2019;104:6049–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mortola JF, Laughlin GA, Yen SS. A circadian rhythm of serum follicle-stimulating hormone in women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1992;75:861–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Su HI, Sammel MD, Freeman EW, Lin H, DeBlasis T, Gracia CR. Body size affects measures of ovarian reserve in late reproductive age women. Menopause 2008;15:857–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Raju GA, Chavan R, Deenadayal M, Gunasheela D, Gutgutia R, Haripriya G et al. Luteinizing hormone and follicle stimulating hormone synergy: A review of role in controlled ovarian hyper-stimulation. J Hum Reprod Sci 2013;6:227–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Erb K, Klipping C, Duijkers I, Pechstein B, Schueler A, Hermann R. Pharmacodynamic effects and plasma pharmacokinetics of single doses of cetrorelix acetate in healthy premenopausal women. Fertil Steril 2001;75:316–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Restrictions apply to the availability of some or all data generated or analyzed during this study to preserve patient confidentiality. The corresponding author will on request detail the restrictions and any conditions under which access to some data may be provided.