Abstract

We conducted a 12-month prospective study comparing two approaches to the detection of Mycobacterium avium in the blood of human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected patients, namely, a lytic centrifugation system combined with Middlebrook solid culture medium (the conventional procedure) and the nonradiometric BACTEC 9000 MB system. Species identification relied on 16S rRNA probe hybridization and cell wall fatty acids chromatography. M. avium was isolated in 17 of 345 (5%) blood specimens by the BACTEC 9000 MB automated system and in 14 of 345 (4%) blood specimens by the conventional procedure (nonsignificant, χ2 test). Detection time was 16 ± 6 days by the BACTEC 9000 MB automated system and 27 ± 3 days by the conventional procedure (P < 0.001, Student t test). Non-M. avium mycobacteria were not recovered during the study period. Contamination rate was 8% (30 specimens) by the BACTEC 9000 MB system and 0% by the conventional procedure, indicating the necessity of using an antibiotic mixture (PANTA, consisting of polymyxin B, amphotericin B, nalidixic acid, trimethoprim, and azlocillin). Working time was 1 min 30 s by the BACTEC 9000 MB system and 8 min by the conventional procedure, which was 1.8 times more expensive than the BACTEC system. Use of the BACTEC 9000 MB system increased the sensitivity of M. avium detection and reduced detection time in blood culture.

Systemic Mycobacterium avium infection is a hallmark of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) infection and accounts for the definition of AIDS (1). It represents one of the most important groups of opportunistic pathogens infecting patients with AIDS (6). The risk of developing M. avium complex (MAC) disseminated disease increases as the CD4 lymphocyte count declines, rarely occurring at cell counts above 100 × 106/liter (8). This is an important cause of reduced survival in HIV-infected patients. MAC lymphadenitis is also an emerging clinical feature of MAC infection in patients treated with highly active antiretroviral therapy (11).

The recommended procedure for MAC isolation and culture from blood includes the use of a lytic centrifugation system and an 8-week incubation of the pellet on Middlebrook agar medium (9, 16). This procedure includes extensive manipulation of HIV-1-contaminated blood during its centrifugation. Moreover, time required for MAC detection is from about 21 to 36 days (5), resulting in the delay of appropriate treatment (8). Although automated MAC culture by the BACTEC 460 TB radiometric method has been shown to be a rapid and sensitive detection method (4), its use has previously been limited because of radioactive reagents. The new nonradiometric BACTEC 9000 MB system (Becton Dickinson, Sparks, Md.), a fluorescence-based system which measures bacterial growth by determining oxygen consumption, has recently been developed. However, the performance of the BACTEC 9000 system in the isolation of blood-borne MAC strains has been evaluated in only one recent study (14). We evaluated a number of positive samples and the detection time with this system and compared the results with those of the lytic centrifugation conventional method.

A total of 345 blood samples were collected from 242 HIV-1-infected patients admitted to a medical school hospital in Marseille, southern France. Ten milliliters of blood was aseptically collected in a lytic centrifugation blood tube (Isolator 10; Wampole Laboratories, Cranbury, N.J.) and collected directly in a BACTEC 9000 MB vial. The tubes were centrifuged once at 720 × g for 30 min, and the sediment was washed twice with sterile distilled water and concentrated by centrifugation (15); the 200-μl pellet was then inoculated onto Middlebrook 2 solid media (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) and incubated in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C for 8 weeks. Middlebrook media were examined once a week for visual detection of mycobacterial growth. The BACTEC 9000 MB vial was supplemented with supplement F (containing 2.3 mg of polyoxyethylene stearate per ml, 116 mg of bovine serum albumin per ml, 3.5 mg of lactic acid per ml, 23 mg of dextrose per ml, and 0.012 mg of biotin per ml) in order to enhance mycobacterial growth.

BACTEC vials were incubated at 37°C for 40 days in the BACTEC 9000 MB system, and fluorescence levels were measured automatically every 10 min. The acid-fastness of the microorganisms was confirmed by Ziehl-Neelsen staining. Isolate identification was based on 16S rRNA probe hybridization (GenProbe, San Diego, Calif.) (3) and confirmed by analysis of the cellular fatty acids chromatogram determined by gas-liquid chromatography (12).

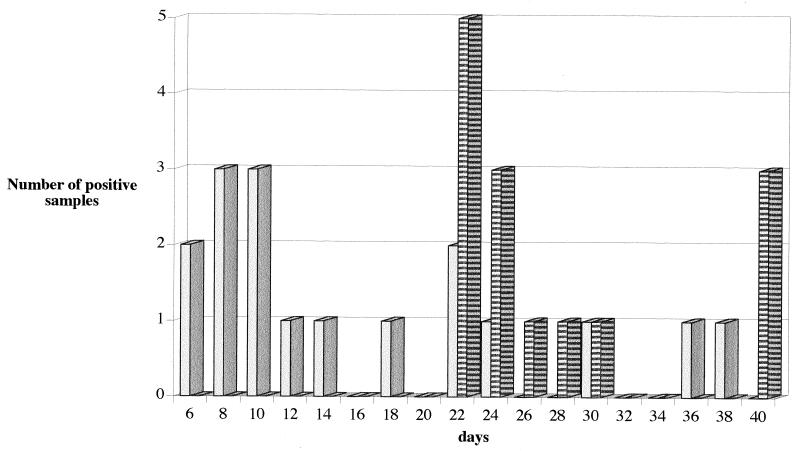

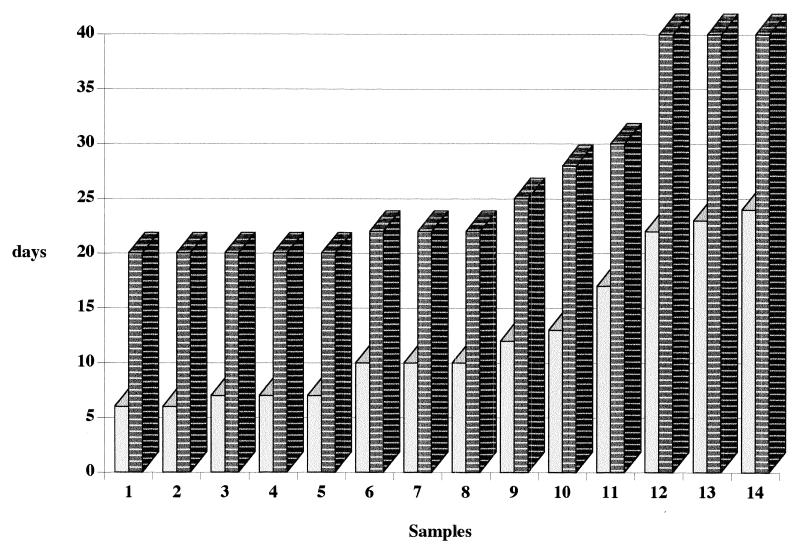

Of 345 blood specimens, 17 (5%) yielded MAC by the BACTEC 9000 MB system, and 14 (4%) yielded MAC by the conventional procedure (the difference is nonsignificant [χ2 test]). Three MAC isolates recovered from three independent blood samples after 30, 36, and 39 days of incubation were not isolated by the conventional procedure. Detection time was 16.4 ± 6 days (6 to 39 days) with the BACTEC 9000 system and 27.7 ± 3 days (22 to 40 days) with the conventional procedure (Fig. 1). The median detection times were 10 days with the BACTEC 9000 MB system and 22 days with the conventional procedure. No specimens found to be positive after the 25th day by the BACTEC system were positive when the conventional procedure was used (Fig. 2). The difference between the detection times of these two methods was significant (P <0.001, Student t test) by the couple method for comparison of the average of the two matched series. Non-M. avium mycobacteria were not recovered during the study period. No contamination was observed by the conventional procedure, whereas 30 of 345 blood specimens (8%) yielded nonmycobacterial microorganisms, including Staphylococcus epidermidis (20 specimens), Candida albicans (4 specimens), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (2 specimens), Micrococcus spp. (2 specimens), Proteus mirabilis (1 specimen), and Streptococcus pneumoniae (1 specimen). Twenty-six of these were considered contamination, whereas 4 of 30 were considered indicative of true bacteremia because of their concurrent presence on standard blood cultures.

FIG. 1.

Detection time of a positive sample with the BACTEC 9000 MB system and the lytic centrifugation system. Light bars represent the lytic centrifugation system, and striped bars represent the BACTEC 9000 MB system.

FIG. 2.

Comparative detection times of M. avium in 14 positive blood samples by the BACTEC 9000 MB system and the lytic centrifugation system. Light bars represent the lytic centrifugation system, and striped bars represent the BACTEC 9000 MB system.

The average working time was 8 min with the conventional procedure (plus centrifugation times before inoculation onto Middlebrook medium), whereas it was 1 min 30 s for the BACTEC 9000 MB system and consisted in inoculation of growth factor before vials were placed in the BACTEC 9000 MB instrument. The cost of materials used was 1.8 times higher for the conventional procedure than for the BACTEC 9000 MB system.

Radiometric detection is a reference system but has known limitations because radioactive reagents are used. An automatic nonradioactive system has been designed with the aim of reducing the delay in the detection of mycobacteria and improving detection rates. The efficacy of acid-fast bacillus detection by the BACTEC 9000 MB system and conventional culture procedures on Middlebrook media was evaluated in parallel for the isolation of M. avium in blood cultures of HIV-1-infected patients. Little data was available regarding the detection time and recovery rates of this mycobacterium in blood culture by the automated system. The necessity of evaluating the performance of any automated system for detection of MAC in blood has recently been stressed (7). Previous evaluations of the BACTEC 9000 MB included all species of mycobacteria in various clinical specimens including respiratory samples; pleural, abdominal, and cerebrospinal fluids; and urine specimens, but experience with blood culture was limited (10, 13, 17). To date, no study has been specifically devoted to the isolation of blood-borne mycobacteria. Indeed, of 72 MAC strains isolated in a previous report, only one was from blood (10). In a second study, 14 MAC strains were isolated from extrapulmonary specimens, including urine (six strains), stool (two strains), cerebrospinal fluid (three strains), and nonspecified samples (three strains) (17). Evaluation of detection time with the BACTEC 9000 MB system has been carried out for M. avium (17), and the time has been compared with that for the conventional method. The typical detection time was from 5 to 11 days with the BACTEC 9000 MB system and from 25 to 35 days with culture on Lowenstein-Jensen medium. The average MAC detection time was measured as 10.8 days with the BACTEC 9000 MB system versus 16 days with the BACTEC 460 system and 28.5 days with solid culture. In this study, however, of the 451 mycobacterial isolates, 8 were MAC isolates, including only 1 blood culture isolate. Contamination rates in these two studies were 4.1% in one (17) and 8.3% in the other (10). In the most recent study, by Waite and Woods (14), the authors compared the performance of Myco/F lytic medium in the BACTEC 9240 blood culture system to that of the Isolator system and the ESP II system for the recovery of mycobacteria. Of the 687 samples of blood cultured for mycobacteria, 58 blood samples grew MAC. Sixty-four blood samples were positive for mycobacteria; 42 isolates were recovered with Myco/F lytic medium in the BACTEC 9240 system, 18 were isolated with Myco/F lytic medium only, and 4 were isolated with the ESP II system alone.

In our study, the recovery rate of M. avium from blood was 5% by the automated method and 4% by the conventional procedure on Middlebrook media. The difference was not statistically significant. The M. avium-containing specimens which remained negative by the 30th day by the BACTEC 9000 MB system may have contained only very low numbers of viable bacteria.

The average detection time of MAC in blood culture was reduced with the BACTEC 9000 MB system (14 days earlier than with the conventional method). The time-to-detection data may be biased toward the BACTEC 9000 MB system because its continuous monitoring is an unequivocal advantage in comparison to the weekly detection with the conventional procedure. Another difference in the culture medium may account for the different rates; a liquid medium was used in the BACTEC vials, while solid medium was used with the conventional method.

The contamination rate in our study was about 8%. There were 26 (87%) probable contaminations and 4 (13%) instances of true bacteremia. Supplementation with PANTA antimicrobial mixture (consisting of polymyxin B, amphotericin B, nalidixic acid, trimethoprim, and azlocillin) effectively reduced contamination rates (data not shown), and we therefore recommend PANTA inoculation in BACTEC vials for blood culture.

The BACTEC 9000 MB system is the quickest and most sensitive method of detecting mycobacterial infection. As no blood manipulation is required, the BACTEC 9000 MB system fulfills safety rules for a microbiology laboratory (2). The system prevents vials from being broken during transportation and handling and reduces the centrifugation-induced risk of mycobacterial aerosol and the transfer of MAC-contaminated pellet to solid medium. Moreover, the BACTEC 9000 MB system is more economical and reduces working time. The BACTEC 9000 MB system is of great interest for routine use in clinical laboratories, and we therefore recommend its use with the addition of the PANTA antimicrobial mixture for the isolation and culture of MAC from blood.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Christian De Fontaine for technical assistance and Richard Birtles for reviewing the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1992 revised classification system for HIV infection and expanded surveillance case definition for AIDS among adolescents and adults. Morbid Mortal Weekly Rep. 1993;41:1–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Biosafety in microbiological and biomedical laboratories. 3rd ed. HHS publication no. 93-8395. Atlanta, Ga: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Doern G V. Turnaround times for mycobacterial cultures. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1041–1042. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.4.1041-1042.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Doern G V, Westerling J A. Optimum recovery of Mycobacterium avium complex from blood specimens of human immunodeficiency virus-positive patients using small volumes of Isolator concentrate inoculated into Bactec 12 B vials. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:2576–2577. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.10.2576-2577.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hanna B A, Walters S B, Bonk S J, Tick L J. Recovery of mycobacteria from blood in mycobacterial growth indicator tube and Lowenstein-Jensen slant after lysis-centrifugation. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:3315–3316. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.12.3315-3316.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Horsburgh C R. Epidemiology of Mycobacterium avium complex disease. Am J Med. 1997;102:11–15. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Inderlied C B. Microbiology and minimum inhibitory concentration testing for Mycobacterium avium complex prophylaxis. Am J Med. 1997;102:2–10. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Low N, Pfluger D, Egger M the Swiss HIV Cohort Study. Disseminated Mycobacterium avium complex disease in the Swiss HIV Cohort Study: increasing incidence, unchanged prognosis. AIDS. 1997;11:1165–1171. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199709000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nolte F S, Metchock B. Mycobacterium. In: Murray P R, Baron E J, Pfaller M A, Tenover F C, Yolken R H, editors. Manual of clinical microbiology. 6th ed. Washington, D.C: ASM Press; 1995. pp. 400–437. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pfyffer G E, Cieslak C, Welscher H M. Rapid detection of mycobacteria in clinical specimens by using the automated BACTEC 9000 MB system and comparison with radiometric and solid-culture systems. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2229–2234. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.9.2229-2234.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Race E M, Adelson-Mitty J, Barlam T F, Reimann K A, Letvin N L, Japour A J. Focal mycobacterial lymphadenitis following initiation of protease-inhibitor therapy in patients with advanced HIV-1 disease. Lancet. 1998;351:252–255. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)04352-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smid I, Salfinger M. Mycobacterial identification by computer-aided gas-liquid chromatography. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1994;16:400–402. doi: 10.1016/0732-8893(94)90117-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van Griethuysen A J, Jansz A R, Buiting A G M. Comparison of fluorescent BACTEC 9000 MB system, Septi-Chek AFB system, and Lowenstein-Jensen medium for detection of mycobacteria. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2391–2394. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.10.2391-2394.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Waite R T, Woods G L. Evaluation of Bactec Myco/F lytic medium for recovery of mycobacteria and fungi from blood. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:1176–1179. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.5.1176-1179.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wasilauskas B, Morell R., Jr Inhibitory effect of the Isolator blood culture system on growth of Mycobacterium avium-M. intracellulare in BACTEC 12B bottles. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:654–657. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.3.654-657.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wolinski E. Conventional diagnostic methods for tuberculosis. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;19:396–401. doi: 10.1093/clinids/19.3.396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zanetti S, Ardito F, Sechie L. Evaluation of a nonradioactive system (BACTEC 9000 MB) for detection of mycobacteria in human clinical samples. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2072–2075. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.8.2072-2075.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]