Abstract

Objectives:

To identify barriers and facilitators of evaluating children exposed to caregiver intimate partner violence (IPV) and develop a strategy to optimize the evaluation.

Study Design:

Using the EPIS (Exploration, Preparation, Implementation, and Sustainment) framework, we conducted qualitative interviews of 49 care providers, including emergency department clinicians (n=18), child abuse pediatricians(n=15), child protective services staff (n=12), and caregivers who experienced IPV (n=4), and reviewed meeting minutes of a family violence community advisory board (CAB). Researchers coded and analyzed interviews and CAB minutes using the constant comparative method of grounded theory. Codes were expanded and revised until a final structure emerged.

Results:

Four themes emerged: 1) benefits of evaluation, including the opportunity to assess children for physical abuse and to engage caregivers; 2) barriers, including limited evidence about the risk of abuse in these children, burdening a resource-limited system, and the complexity of IPV; 3) facilitators, including collaboration between medical and IPV providers; and 4) recommendations for trauma- and violence-informed care (TVIC) in which a child’s evaluation is leveraged to link caregivers with an IPV advocate to address the caregiver’s needs.

Conclusions:

Routine evaluation of IPV-exposed children may lead to the detection of physical abuse and linkage to services for the child and the caregiver. Collaboration, improved data on the risk of child physical abuse in the context of IPV, and implementation of TVIC may improve outcomes for families experiencing IPV.

Intimate partner violence (IPV) between caregivers is an important risk factor for the physical abuse of children. IPV affects 1 in 4 women and nearly 1 in 10 men in America during their lifetime,1 with children present during 50–75% of IPV episodes.2, 3 IPV may serve as a “sentinel” event and an opportunity to intervene to protect children from abuse. Physical abuse affects about 120,000 children annually in the United States, with children <3 years old at the highest risk.4 Physical child abuse is reported to occur in 30–60% of homes with IPV,5–10 and in a highly selective sample of children for whom a child abuse pediatrician was consulted, among 61 IPV-exposed children, 59% had injuries identified, and almost half of these were occult and detected only by x-rays.11 Most IPV-exposed children, however, are never evaluated for abuse – a critical gap because detection of child abuse in the context of IPV may lead to interventions to reduce future family violence.12

Evaluation of children for abuse after exposure to IPV, however, raises ethical, legal, and logistical considerations. Detection of abuse has competing consequences for children and caregivers. While recognition may benefit the child, it may harm non-abusive caregivers if it leads to their own (re)victimization, loss of custody, or legal sanctions.13 Fear of legal sanctions may lead families to provide inaccurate information and may serve as a barrier to victims seeking help.14 In contrast, concerns about the safety of a child in the context of ongoing family violence may be an important catalyst for an abused caregiver to seek help for herself or the child.15 Given these complexities, an understanding of priorities of professionals who care for IPV survivors and their children and survivors themselves is critical to inform approaches to the evaluation of abuse in IPV-exposed children.

The purpose of this study, therefore, was to understand the perspectives of providers involved in the care of IPV victims and their children to: 1) identify the barriers and facilitators of the evaluation of young IPV-exposed children for abuse and to 2) develop a strategy to optimize the evaluation. The EPIS framework,40,41 developed to guide implementation of programs in publicly funded sectors, identifies four well-defined phases that describe the implementation process: Exploration, Preparation, Implementation, and Sustainment, would be deployed. In each stage, factors important to successful implementation in both the inner context (ie, within the implementing organization itself) and the outer context (ie, external to, but still influential on, the implementing organization) are identified, as are bridging factors that connect the inner and outer contexts (i.e., community-academic partnerships) and their interactions. EPIS allows for examination of processes for change at multiple levels, across time, and through successive stages that build toward implementation, while identifying factors that impact sustainability.

Methods

Prior to implementing the study, a Family Violence Community Advisory Board (CAB) was established to guide the development of a local program implemented in an emergency department (ED) to evaluate IPV-exposed children for abusive injuries.16 Members included IPV service providers, child protective services (CPS) staff, ED providers and a social worker, child abuse pediatricians (CAPs), a trauma clinician and an IPV survivor. CAB members participated in ongoing discussions about the development and refinement of the local program and provided guidance on how to address the needs and priorities of IPV survivors while implementing a program to evaluate children exposed to IPV. CAB meetings were recorded, and meeting minutes were transcribed by a program administrative assistant and reviewed and edited for accuracy by a co-director of the CAB (GT). For this study, CAB members participated in research activities, including development of the interview guide and identification and recruitment of care providers to be interviewed; meeting minutes were used as data for the qualitative study.

In this “Exploration” phase of EPIS, we used a qualitative approach to understand barriers and facilitators of implementing routine evaluation of abuse in children living with IPV in an existing program designed to evaluate young IPV-exposed children for abusive injuries and in child abuse centers nationally. Key informant interviews were conducted to understand perspectives on evaluating IPV-exposed children. Care providers included: 1) local ED clinicians (physicians, nurses, and social workers); 2) child abuse pediatricians (CAPs) locally and nationally who are members of the Child Abuse Pediatrics Network (CAPNET), a multicenter child abuse research network;17 3) local CPS staff; and 4) parents who experienced IPV and accompanied their children to an ED after an IPV event. Purposive recruitment of care providers of the program occurred by email, in-person, at staff meetings, and through snowball sampling in which existing participants or CAB members recruited additional participants.18 Care providers who had voiced either support for or concerns about the program were recruited to understand varying perspectives. The PI was notified by ED staff when children presented for evaluation after IPV exposure and sought consent during the ED visit to call the caregiver for an interview. The informed consent materials highlighted that participation was voluntary and that the caregiver’s decision about participation would not affect the care of their children.

Interviews were conducted in-person prior to the COVID pandemic, and by phone or via Zoom after its onset. While efforts to recruit care providers paused during the first 3 months of the pandemic from March-June 2020, efforts resumed in July 2020. Caregiver recruitment occurred only over a 3-month period before the local program implemented in the ED to evaluate children exposed to IPV was refined and relocated. Participants were compensated with a $25 gift card. To triangulate interview data and incorporate additional perspectives of IPV service providers and an IPV survivor, minutes from six CAB meetings during the first year of its existence were analyzed. The COREQ checklist was used to report elements of the study design.19

Interviews were conducted by GT, PS, and DC, all of whom were trained in qualitative interviewing, from January 2020 to September 2021. Caregivers who experienced IPV were interviewed only by PS and DC, neither of whom was involved in the clinical care of the children. The research team and CAB members developed and iteratively modified interview guides for each care provider group (Table I). Guided by the EPIS framework, questions sought to understand care providers’ perspectives on barriers to and facilitators of evaluating IPV-exposed children, factors in the “Inner Context” (ie, the readiness of an organization, frontline provider buy-in), and “Outer Context” (ie, values of IPV groups) that may impact evaluation, and recommendations to facilitate the evaluation. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed. Yale University’s IRB approved the study, and participants provided signed informed consent.

Table 1:

Examples of questions for participant groups

| Participant Group | Questions |

|---|---|

| Pediatric Emergency Department (ED) providers | What are some challenges to evaluating children exposed to intimate partner violence for abuse in the pediatric ED? What are some benefits? What would help you evaluate a child in the ED after intimate partner violence exposure? What would be the ideal process for assessing children exposed to intimate partner violence for injury? |

| Child Protective Services (CPS) Staff | How do you assess a child’s safety risk when intimate partner violence exposure is a primary cause of the DCF* report? What are some challenges in assessing for abuse and neglect in a child reported to DCF after experiencing intimate partner violence? What helps when working with intimate partner violence-exposed families? |

| Child Abuse Pediatricians | In your opinion, what would be the ideal process for evaluating intimate partner violence - exposed children for injury? What are some benefits and challenges to medically evaluating intimate partner violence - exposed children without a known injury? What do you think would facilitate a standardized practice in hospitals for evaluating intimate partner violence -exposed children for injury? |

| IPV-affected caregivers | What were some of the challenges you had with having your child seen in the ED? Were there any benefits to you or your child from this ED visit? What can be done in the ED to help families who are experiencing violence? In your opinion, what would be the best way to have your child get a medical evaluation to check for an injury? How do you feel about reaching out for help for yourself in the future if you experience violence in the home? |

**DCF-Department of Children and Families, Connecticut’s CPS agency

Analysis

Five coders experienced in the analysis of qualitative data and with varying backgrounds in child abuse and IPV to ensure reliability used the constant comparative method of grounded theory to analyze data.18 Researchers independently reviewed the transcripts and applied codes to categorize portions of the data.20 Codes were iteratively expanded, revised, and merged as they were applied to incoming data until a final code structure emerged (Supplemental File 1).20 While codes were inductively clustered into recurrent themes related to barriers and facilitators of evaluating IPV-exposed children,42 the EPIS internal, external, and bridging factors were used as a guide. The code list contained a definition of the codes and categories and guidelines for their application. When discrepancies about codes arose, text segments that had been assigned the same code previously were assessed to determine whether they reflected the same concept. Coders engaged in discussion to attain consensus about the correct label for each segment of the text. Codes were clustered into recurrent themes. Qualitative software (ATLAS.ti 5.0) facilitated data organization and retrieval.

To optimize dependability and credibility, we maintained an audit trail and performed a member check by intermittently presenting results to CAB members (who acted as a proxy for the participants) to assess if our interpretations were a reasonable representation of care providers’ input.21 Data collection/analysis continued until past the point of thematic saturation for the perspectives of each professional care provider group.21–23

Results

The transcripts of 49 care provider interviews (Table 2) and minutes from six CAB meetings were analyzed. Among the ED clinician and CPS investigator groups, 3 providers each were recruited by CAB members for voicing concerns about routine evaluation of IPV-exposed children.

Table 2:

Participants’ Clinical and Demographic Data

| ED Clinicians, n=18 (2 nurses, 12 doctors, 4 social workers) | CPS Staff, n=12 (6 investigators, 6 supervisors) | CAPs, n=15 | Parents, n=4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| • Unknown | 1 (5.6%) | - | - | |

| Age, mean (SD) | 43 (12.2) | 44 (7.7) | 55 (9.9) | 29 (6.2) |

| • Female | 13 (72.2%) | 8 (66.7%) | 9 (60%) | 4 (100%) |

| • Other | 3 (16.6%) | 1 (8.0 %) | 1 (7.0%) | |

| • Hispanic | 1 (5.6%) | 1 (8.0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (25%) |

Four themes emerged: 1) benefits of a routine evaluation of IPV-exposed children, 2) barriers to evaluation, 3) facilitators of such evaluations, and 4) a strategy of trauma- and violence-informed care (TVIC). Table 3 provides additional quotations related to each theme.

Table 3:

Themes and Representative Quotes

| Theme | Quotations | |

|---|---|---|

| 1) an opportunity to assess children at highest risk | Pediatric ED Physician – “To find the one that might go home and be killed by the violence, to try to prevent any significant harm” | |

| 2) reassurance about the physical well-being of a child | CPS investigator – “She was feeding the baby. She questioned the dad about selling formula and dad kicked her in the back when she was breastfeeding. It was reassuring to the mom and me that there was no physical injuries because of the IPV. For the mom, it was nice to know that the baby who can’t speak was okay and for me. I was like, “Oh my God. I found out through this investigation that the baby fell a week prior.” Although there’s no visible injuries, I’m not a doctor.” | |

| 3) possibility to engage a caregiver in resources through the child’s evaluation | ED Social Worker – “The benefits are also making sure that the family’s treated as a unit. You’re not just focusing on the child’s needs.” | |

| 1) lack of robust evidence about the risk of child abuse in the context of IPV | Child Abuse Pediatrician – “If one [IPV-exposed child] was brought to me, I wouldn’t [obtain occult injury testing] right now. We need to know more information on that. Right now, a witness, a kid in another room, I wouldn’t do any of those tests. I don’t have a great argument, I just don’t have any data to really tell me what to do.” | |

| 2) burden on a resourcelimited system | Child Abuse Pediatrician – “If you think about the number of women who are victims, the number of women who have kids… what’s the system’s capacity?” | |

| 3) parental refusal of an evaluation | CPS Investigator – “I get a lot of pushback from family sometimes when they feel, okay, children weren’t present. They were in another room, or they would say they weren’t—basically, they weren’t present. They would push back and say that there’s no need for them to have them bein’ seen by the doctor or somethin’ like that. They would say, ‘Oh, the incident, it’s the first time they were physical with each other.’“ | |

| 4) complexity of IPV cases | Child Abuse Pediatrician – “Also you’re in a volatile, violent situation and the more interventions you have—now you’re getting the kid evaluated, and that might make it more volatile, because more stuff starts flowing out and it becomes harder and more unwieldy for anyone to control. I think that’s why when you start doing these things, you have to have the systems in place and you have to know how to handle what you find, to not escalate something that’s already bad for somebody.” | |

| Theme 3: Facilitators of evaluating children after exposure to IPV | 1) collaboration | CPS Investigator – “I wanna say just the ability to communicate with the workers, staff involved in this process from the doctors to the nurses to the people facilitating this study. The ability to communicate with them has been good.” |

| 2) training for providers on IPV and providing caregiver-centered support | Child Abuse Pediatrician – “pediatricians, they feel uncomfortable. They don’t know how to have those conversations with families to be asking the appropriate questions to even know if it’s [IPV] an issue, and so I think across the board that tends to be a challenge and leading to under recognition or delayed recognition. Victim willingness to talk, trust…go hand-in-hand?” | |

| Theme 4: A trauma- and violence-informed care strategy for IPV | ED Nurse – “I think if there’s any obvious injury, really bruising or bleeding… of course, if they have anything that looks like a fracture…they should [be seen in an emergency department]. If they look well-appearing children, nourished and fed well and not with any bruises, those might be the kids that might be able to go to a different set up, like a clinic or primary care provider…” Child abuse pediatrician – “I think that an ideal process would be for these families to get evaluated in a different setting. Perhaps the child abuse clinic where we can offer services to both the mom and the child in a friendly, calm environment and really offer the support that the mom needs and have follow-through.” Parent – “Going through the ER seemed like it was scary for x (son). He doesn’t understand what was going on. The pediatrician’s office is—the walls have pictures. They have stuff over there that, just a little bit more, it makes the kids feel comfortable. I will say that, when you handed him the toys, though, he was so much happier. He looked like he was, actually, enjoying it.” |

|

Theme 1: Benefits

Opportunity to assess the most vulnerable children:

Most care providers understood the interconnection between IPV and child physical abuse. They valued the medical evaluation of IPV-exposed children regardless of whether the child had an overt injury, particularly in infants and toddlers who are not able to speak about what they have seen or experienced and felt a medical evaluation may provide an opportunity to identify potential for harm and to intervene before the violence escalated. One child abuse pediatrician noted,

We may be seeing the proverbial tip of the iceberg… Maybe they reported some yelling, or the kid was left outside without a jacket in cold weather. I think it’s hard to know exactly what’s going on inside the head of a younger child, particularly a preverbal child, who can’t really describe what they’re experiencing.

Care providers felt that the medical evaluation may also help address the child’s unmet medical and behavioral health needs. One social worker commented, “Is this a child that nobody’s realized needs a Birth to Three [Early Intervention] because they’re not speaking or they’re not meeting certain milestones?”

Reassurance:

CPS investigators endorsed feeling reassured by a normal physical exam and negative testing for occult injury and described a reduction in the “burden” of having to assess the child’s physical well-being themselves. Many investigators felt that routine evaluation of a child after IPV exposure was important because parents may fail to report injury to their children for various reasons.

Parents reported that medical evaluations provided reassurance and did not dissuade them from seeking help for themselves in the future. They commented that they wanted to ensure that their children were physically healthy. After participating in her child’s evaluation, one mother stated: “it makes me feel a lot more comfortable in calling the police anytime anything like this would ever happen. I feel like there was a lot of people rallying around me and the kids…”

Caregiver engagement:

Many providers discussed that a child’s visit could serve as an opportunity to connect the caregiver to resources. Members of the CAB discussed how a child’s visit could be leveraged to connect the caregiver to an IPV advocate who would be able to address the caregiver’s needs. One member said, “We want to understand which children are at highest risk of being abused…, but we also want to find a way to support the caregiver going through the trauma of IPV.”

Theme 2: Barriers

Lack of evidence:

Care providers discussed the lack of data to support routine evaluation of all IPV-exposed children. While many CAPs identified similarity in their management of children <2-years-old who are physically injured after IPV exposure with that of children who present with injuries concerning for physical abuse (a physical exam and occult injury testing), they universally described struggling with how to proceed when an uninjured child (e.g., a child that was asleep in another room during the IPV event) or an older injured child presented after IPV exposure. Participants advocated for generating data on the risk of occult injury in both injured and uninjured IPV-exposed children so that evaluation could be informed by evidence.

Burden on the system:

CPS investigators and ED providers felt medical evaluations of IPV-exposed children would increase workloads and prolong encounters in the ED. CAPs discussed burdening an already-burdened system if all IPV-exposed children were to receive medical evaluations. They also discussed the challenges of evaluating IPV-exposed children in community EDs or pediatric clinics, which may not have trained providers or access to resources such as social workers or radiology studies. Finally, participants identified lack of mental health resources as a major barrier to providing necessary support to IPV-exposed children.

Parental refusal:

Another barrier reported was a parent’s refusal of a child’s evaluation due to the belief that the child was not injured and fear of what might happen because of the evaluation. One CPS investigator discussed why a caregiver may not want a child evaluated, “They’re [parents] saying, “the kids weren’t injured.” Yeah, they were in the home when the incident happened but not directly in the vicinity when the domestic violence occurred…” During interviews and CAB meetings, care providers discussed that caregivers may fear reports to CPS or even losing custody of a child if an injury were discovered during the evaluation: “parents are afraid they’re gonna lose their children. If I bring my child there to be evaluated and there’s something wrong…, and I potentially expose them, then I’m gonna lose my child…”

The complexity of IPV cases:

Care providers described the complexity of working with and supporting families in which one of the caregivers is experiencing IPV. Care providers discussed the frequent dependence of the primary caregiver on the abuser for finances, housing, and other necessities; concerns about immigration status; the frequent co-occurrence of mental health and substance use disorders with IPV; and a caregiver’s tolerance of the abuse to provide stability for the child. A parent described her dependence on the abuser, “He won’t give the kids money to eat or anything. I feel like it’s just a really big control issue. It’s frustrating. That’s the reason why I ended up going back the last time I got a restraining order on him. If we’re not together, he doesn’t help out with anything.” One child abuse pediatrician similarly summarized,

they’re worried that if they left, they would be isolated from everything they knew… Maybe they thought they would be killed. Many times folks think that they have protected their children without recognizing that their children may have been either physically or emotionally harmed in that context, despite their best efforts…

Care providers described feeling challenged in their effort to advocate simultaneously for both the children and their parents. They reflected that while identifying physical abuse in children might be beneficial if corrective interventions were put in place, it could further victimize parents who might then be considered unable to protect their children and potentially face a report to CPS. CAB members and CPS investigators also discussed the potential for racial inequity to wrongly influence which families would undergo evaluation if a model of routine evaluation was implemented. They discussed structural racism and how that might impact a perception of choice about a child’s evaluation among minority families. One CPS investigator discussed,

I have mixed feelings…I happen to be African American. We talk about disproportionality in many facets of social work and most of our clients, especially in New Haven, are black and brown. I think that, sometimes, they’re so fearful of us [CPS] that they don’t feel like they have much of a choice to do certain things.

Theme 3: Facilitators

Collaboration:

Partnerships between IPV service providers, CPS and medical providers were thought to facilitate a cohesive approach to supporting the family. One CAP described the value of connecting a caregiver to an IPV advocate during a child’s evaluation, “having established ways of working together, those are facilitators… being able to contact a colleague who would be working with the mother so that she can meet the mother right there and then…” Participants described at least three different models in which medical providers partnered with community providers: some described situations in which IPV advocates were housed within the hospital and available to meet caregivers when children presented after IPV, some described housing of child protective services in the same building as a child advocacy center that facilitated consultation of a CAP for cases of child-exposure to IPV, and others described a model in which “warm referrals” made by the provider on behalf of the caregiver to an IPV service provider could be implemented during a child’s visit.

Access to social workers and CAPs was also felt to be important. ED providers discussed the social worker’s role in obtaining a more complete history in a nonjudgmental manner and connecting families to community resources. Care providers also discussed the benefits of having a CAP guide the medical evaluation and decisions on reporting to CPS when children presented after IPV.

Training and Support:

Participants discussed the importance of training medical clinicians to provide adequate support once an IPV disclosure was made, such as by offering local IPV-based community resources, minimizing blame, practicing compassion, and building trust with caregivers. One IPV survivor discussed the importance of provider compassion,

Language, tone and how you present information is very important. In the last two years, I would not have admitted anything [IPV] was happening even if it was. The people asking me didn’t even look at me. They were asking questions they had to ask.

Theme 4: A Trauma- and Violence-Informed Two-Track Model of Care for IPV-exposed Children

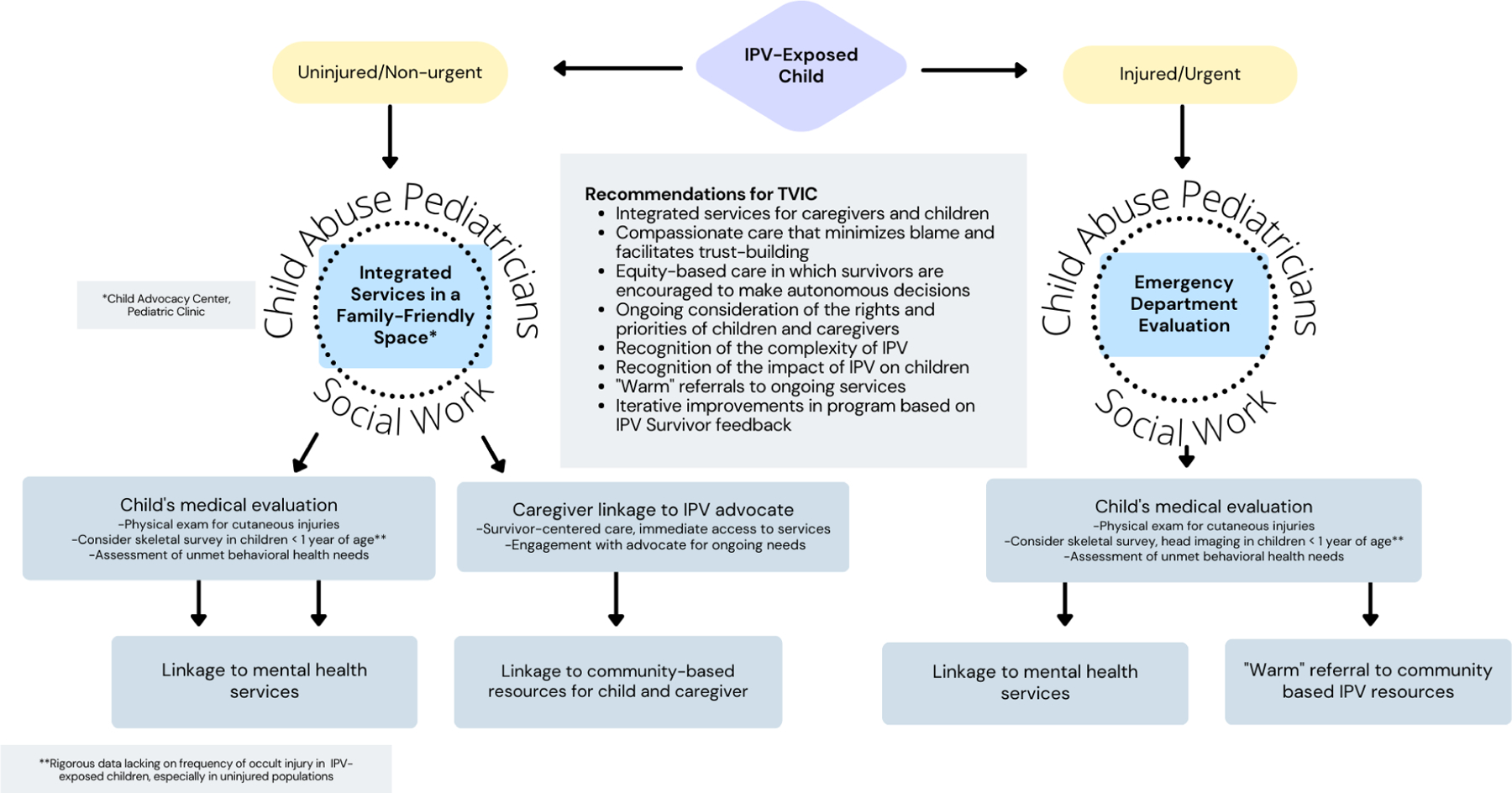

Care providers desired a more standardized process for the evaluation of children exposed to IPV that was informed by the evidence and could obviate variability in which children were evaluated for abusive injuries and reported to CPS. Care providers’ input about an optimal way to evaluate IPV-exposed children informed our two-track model of care for IPV, supported by social-workers and CAPs and informed by a strategy of trauma- and violence- informed care (TVIC) (Figure 1). Care providers recommended that urgent evaluations, like those performed for suspected physical abuse, occur in EDs for injured children (e.g., the child was dropped while the mother was assaulted or a child was found to have injuries, such as bruising after exposure to an IPV event), especially if <2-years-old. For children without obvious injuries or older children, non-urgent medical evaluations were recommended to occur in a family-friendly environment, such as a child advocacy center, in which care could be co-located for the child and the abused caregiver. Principles of TVIC emphasized by our care providers included the integration of services for the caregiver and children, practice of compassionate care that minimized blame on the caregiver and facilitated trust-building, equity-based care that prioritized caregiver autonomy, ongoing consideration of rights and priorities of children and caregivers that recognized the complexity of IPV and its impact on children, and routine linkage of caregivers and children to ongoing community-based services.

Figure 1:

Trauma- and Violence-Informed Care (TVIC): A Two-Track Model for IPV-exposed Children

Discussion

Our study examines barriers and facilitators to the evaluation of young IPV-exposed children for abusive injuries and informs next steps in IPV research in the pediatric population. Our findings demonstrate that while the complexity of IPV and the lack of definitive data about the risk of child physical abuse in IPV-exposed children serve as barriers to routine evaluation of young children exposed to IPV, benefits of the evaluation include the detection of child physical abuse and linkage to services for the child and the abused caregiver. Collaboration among professionals and implementation of trauma- and violence-informed care (TVIC) may improve outcomes for families experiencing IPV.

Participants discussed numerous barriers to providing care to families living with IPV. The literature about help-seeking behavior by IPV survivors echoes these barriers, such as the lack of independent housing, concerns about worsening safety for the child or self, and personal barriers (eg, co-occurring substance use).24 Furthermore, as discussed by participants, evaluation of children and the potential recognition of child abuse may have competing ramifications for children and caregivers. In studies examining barriers to help-seeking for IPV, caregivers describe concerns about potential consequences for their children in the setting of IPV disclosure, which include involvement of CPS, removal of the children from the non-abusive parent’s custody, the potential for the abuser to gain full custody, worsening the physical safety of the children and, finally, concerns around leaving children without their fathers.24 While caregivers in our study had a positive perception of the evaluation of their children, understanding of the perspectives of caregivers affected by IPV who have not sought care or consented to evaluation for their children after identified IPV might further inform the development of a model of child evaluation after IPV exposure. In addition, examining help-seeking behaviors of caregivers after the child has been evaluated for abuse will be important to assess unintended consequences of such a model of care.

Professionals in our study also discussed concerns about reporting to CPS in the setting of child evaluation after exposure to IPV. While exposure to IPV has been shown to have harmful effects on child development, there is less agreement on when exposure to IPV should be reported to CPS.25 Furthermore, in a study examining CPS reports in the context of a caregiver’s seeking health care in an ED for IPV, Butala et al. demonstrated that the odds of reporting to CPS when adjusting for the child’s physical involvement in the IPV remained higher in Hispanic patients, especially those who reported Spanish vs. English-language preference,26 indicating possible bias in reporting practices in the context of IPV. Decision support around when to report to CPS and how to support caregivers when a report is being made may be acceptable to frontline clinicians, improve care of abused caregivers, and ultimately lead to reports only when a specific harm threshold has been met.

Participants, importantly, discussed concerns about the lack of robust data on the frequency of abusive injuries in IPV-exposed children and potential bias affecting which children would undergo evaluation. The yield of testing for abusive injuries in IPV-exposed children has been reported only in one small study, which demonstrated that in a highly selective sample for whom a child abuse pediatrician was consulted, among 61 IPV-exposed children, 59% had injuries identified, and almost half of these were not apparent based on the history of physical exam.11 While IPV may be a critical opportunity to recognize physical child abuse and to intervene to prevent ongoing disability or death in children, this problem has not been adequately studied. Better understanding of the frequency of abusive injuries and the factors that increase risk (e.g., the IPV victim sustains internal injuries) can help ensure that limited resources are targeted to children at highest risk.

Despite the lack of robust data on frequency of abusive injuries in young children, numerous survey-based studies have demonstrated a frequent co-occurrence of physical child abuse and IPV,5–7, 9, 10 while others have demonstrated suboptimal well child-care27 and unmet behavioral health needs28, 29 for children whose mothers report IPV. In our study, participants felt that evaluation of IPV-exposed children could facilitate the identification of abuse and connections to needed services, such as those for mental health for both the child and caregiver. Participants also noted that the evaluation may present an opportunity to intervene to prevent future harm. Previous research supports this idea; one study identified lower rates of severe physical abuse in children who lived in a home where IPV had been identified, perhaps because the earlier IPV event had triggered protective interventions.12 Another study of families with caregiver-reported IPV undergoing evaluation for maltreatment by CPS noted a significant improvement in children’s behavioral health problems after resolution of IPV.29 Resolution of IPV was associated with referrals to IPV services by CPS.29

Collaboration between medical providers, CPS, and IPV groups was thought to facilitate evaluation and the care of children exposed to IPV. One example of a hospital-based, regional program that offers IPV-related support to clinicians and provides direct confidential support to survivors when IPV is disclosed during a pediatric visit is the Children’s and Mom’s Project (CAMP). In the CAMP model, screening-based disclosures of IPV during a child’s visit for any reason to one children’s hospital led to a direct referral to an on-site IPV counsellor. Evaluation demonstrated 6 to 22 new referrals per month occurring from all pediatric settings, including EDs and pediatric clinics.30 The authors recognized the value of embedding IPV services within pediatrics to facilitate supportive services for caregivers who had experienced IPV. Similarly, best practices in child welfare agencies seeking to improve the response to children exposed to IPV include that CPS agencies should collaborate with other disciplines, such as IPV service providers involved with preventing and responding to IPV.31 Rigorous evaluation of collaborative strategies may increase knowledge and dissemination of effective practices.

While trauma-informed care in medical encounters aims to create safe spaces that limit the potential for further harm in care interactions with individuals who have experienced trauma, TVIC expands this concept and accounts for the overlapping impacts of systemic and interpersonal violence and structural inequities on a person’s life.32 TVIC includes: 1) awareness of trauma and violence and their impacts on people’s lives; 2) prioritizing physical, emotional, and cultural safety; 3) promoting person-centered connection, collaboration and choice; and 4) finding and building on people’s existing strengths.32, 33 TVIC also emphasizes the responsibility of healthcare providers/organizations to align services at the point of care, rather than people having to work to obtain services to meet their needs. Our strategy of TVIC for IPV that recommends providing services for the caregiver during the child’s evaluation promotes person-centered connection by emphasizing the linkage to advocacy services for the caregiver while attending to the medical and mental health needs of the child. Provision of compassionate care that minimizes blame and promotes trust-building may further lead to perceptions of emotional safety for the caregiver.

While care providers discussed the importance of racism and its impact, particularly on CPS-involved families, as well as the co-existence of many social determinants of health with IPV, explicit discussion about providing services for culturally diverse families was lacking. This may, in part, be due to the limited diversity of our sample of care providers. In the context of IPV, women of immigrant and refugee background face additional barriers such as past exposures to trauma, fear of deportation, limited English proficiency, social isolation, and challenges with accessing support services that may limit disclosure of and access to services for IPV.34 Future research to examine the experiences and priorities of diverse caregivers will be important to further modify our strategy and assure cultural competence in its delivery.

Our study has at least four limitations. First, our sample included only four caregivers who were affected by IPV. Thus, we did not obtain a representative sample of caregivers and were unable to achieve thematic saturation related to the perspective of caregivers. However, we included minutes from CAB meetings during which 3 IPV service providers and an IPV survivor provided active input. Second, most care providers identified as white, and only 22% were Black or Hispanic. This lack of diversity may have decreased the cultural responsiveness of the recommendations provided in this study and propagate unintended consequences of routine evaluations that differentially impact children of color. To partially mitigate the impact of this limitation, discussions about limiting bias and addressing racism for the families involved in the child welfare system were routinely addressed by CAB members and 5/14 (36%) members of the CAB identified as Black or Hispanic. Third, we interviewed CPS investigators and ED clinicians from one region and one academic center, respectively; therefore, our findings may not be generalizable to other regions and states in which IPV-related processes may differ. Obtaining perspectives of CAPs nationally may have partially mitigated this concern. ED clinicians practicing in general EDs and other clinicians, such as general pediatricians, who may be faced with a disclosure of IPV may offer additional important perspectives. Fourth, we employed snowball sampling; this approach may have skewed our sample to those more likely to have positive perceptions about evaluating IPV-exposed children. However, we specifically recruited those who had voiced concerns during discussions about evaluating IPV-exposed children. Implications and Next Steps:

First, our findings could significantly alter the approach taken to evaluate and provide care to children exposed to IPV. A TVIC strategy to evaluate young children exposed to IPV in which evaluation of IPV-exposed children is leveraged to connect the parent to an IPV advocate may improve engagement of the caregiver with a child’s evaluation and improve safety planning for children and caregivers living with household violence. Second, clinicians evaluating children exposed to IPV and their caregivers must strive to gain understanding of the complexity of IPV, knowledge of cultural norms and beliefs, and acquire attitudes and skills that assure equity, promote autonomy, and respect cultural differences among diverse populations.35 Third, collaboration among clinicians, IPV groups and CPS is critical to providing holistic care to families living with IPV. Next steps include implementing the TVIC model and assessing its effectiveness on clinical outcomes related to children (e.g., reports to CPS for IPV exposure, engagement in behavioral health services) and caregivers (e.g., perceptions of empowerment, follow-up with IPV-based services, reports of continued IPV) and incorporating diverse survivor perspectives to assure patient-centeredness of the model.

In conclusion, routine evaluation of IPV-exposed children may lead to the detection of ongoing abuse and linkage to services for the child and abused caregiver. Collaboration, improved data on the frequency of abuse, and implementation of a TVIC model may improve outcomes for IPV-involved families.

Supplementary Material

Funding:

This work was supported by funds from the National Institute of Child Health & Human Development grant K23HD107178 (GT). The contents of this manuscript are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of the NIH.

Conflict of Interest:

Andrea Asnes reports that the Department of Pediatrics receives payment for her expert testimony in child abuse cases and that she receives grants from the State of Connecticut to support the Yale Child Abuse Programs. The other authors report no other financial or ethical conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The findings in this paper were previously presented as a presentation at the 2021 Pediatric Academic Societies conference.

References

- [1].Breiding MJ, Smith SG, Basile KC, Walters ML, Chen J, Merrick MT. Prevalence and characteristics of sexual violence, stalking, and intimate partner violence victimization--national intimate partner and sexual violence survey, United States, 2011. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2014;63:1–18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Ernst AA, Weiss SJ, Enright-Smith S. Child witnesses and victims in homes with adult intimate partner violence. Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13:696–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Fantuzzo J, Fusco R. Children’s direct sensory exposure to substantiated domestic violence crimes. Violence Vict. 2007;22:158–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Administration on Children, Youth and Families, Children’s Bureau. Child Maltreatment 2018. 2020.

- [5].Jouriles EN, McDonald R, Slep AM, Heyman RE, Garrido E. Child abuse in the context of domestic violence: prevalence, explanations, and practice implications. Violence Vict. 2008;23:221–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Appel AHG. The co-occurence of spouse and physical child abuse: A review and appraisal. Journal of Family Psychology. 1998;12:578–99. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Edleson J The Overlap Between Child Maltreatment And Woman Battering. Violence Against Women. 1999;5:134–54. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Christian CW, Scribano P, Seidl T, Pinto-Martin JA. Pediatric injury resulting from family violence. Pediatrics. 1997;99:E8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Casanueva C, Martin SL, Runyan DK. Repeated reports for child maltreatment among intimate partner violence victims: findings from the National Survey of Child and Adolescent Well-Being. Child Abuse Negl. 2009;33:84–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Hamby S, Finkelhor D, Turner H, Ormrod R. The overlap of witnessing partner violence with child maltreatment and other victimizations in a nationally representative survey of youth. Child Abuse Negl. 2010;34:734–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Tiyyagura G, Christian C, Berger R, Lindberg D, Ex SI. Occult abusive injuries in children brought for care after intimate partner violence: An exploratory study. Child Abuse Negl. 2018;79:136–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Miyamoto S, Romano PS, Putnam-Hornstein E, Thurston H, Dharmar M, Joseph JG. Risk factors for fatal and non-fatal child maltreatment in families previously investigated by CPS: A case-control study. Child Abuse Negl. 2017;63:222–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Bragg HL. Child Protection in families experiencing domestic violence. Washing DC: Department of Health and Human Services; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Rizo CF, Macy RJ, Ermentrout DM, O’Brien J, Pollock MD, Dababnah S. Research With Children Exposed to Partner Violence: Perspectives of Service-Mandated, CPS- and Court-Involved Survivors on Research With Their Children. J Interpers Violence. 2017;32:2998–3026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Zink T, Elder N, Jacobson J. How children affect the mother/victim’s process in intimate partner violence. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003;157:587–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Newman SD, Andrews JO, Magwood GS, Jenkins C, Cox MJ, Williamson DC. Community advisory boards in community-based participatory research: a synthesis of best processes. Prev Chronic Dis. 2011;8:A70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Kratchman DM, Vaughn P, Silverman LB, Campbell KA, Lindberg DM, Anderst JD, et al. The CAPNET multi-center data set for child physical abuse: Rationale, methods and scope. Child Abuse Negl. 2022;131:105653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Curry LA, Nembhard IM, Bradley EH. Qualitative and mixed methods provide unique contributions to outcomes research. Circulation. 2009;119:1442–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19:349–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Strauss AL, Corbin Juliet M. Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Hanson JL, Balmer DF, Giardino AP. Qualitative research methods for medical educators. Acad Pediatr. 2011;11:375–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Varpio L, Ajjawi R, Monrouxe LV, O’Brien BC, Rees CE. Shedding the cobra effect: problematising thematic emergence, triangulation, saturation and member checking. Med Educ. 2017;51:40–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].LaDonna KA, Artino AR Jr., Balmer DF. Beyond the Guise of Saturation: Rigor and Qualitative Interview Data. J Grad Med Educ. 2021;13:607–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Robinson SR, Ravi K, Voth Schrag RJ. A Systematic Review of Barriers to Formal Help Seeking for Adult Survivors of IPV in the United States, 2005–2019. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2021;22:1279–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Victor BG, Rousson AN, Henry C, Dalvi HB, Mariscal ES. Child Protective Services Guidelines for Substantiating Exposure to Domestic Violence as Maltreatment and Assigning Caregiver Responsibility: Policy Analysis and Recommendations. Child Maltreat. 2021;26:452–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Butala N, Asnes A, Gaither J, Leventhal JM, O’Malley S, Jubanyik K, et al. Child safety assessments during a caregiver’s evaluation in emergency departments after intimate partner violence. Acad Emerg Med. 2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Bair-Merritt MH, Crowne SS, Burrell L, Caldera D, Cheng TL, Duggan AK. Impact of intimate partner violence on children’s well-child care and medical home. Pediatrics. 2008;121:e473–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Campbell KA, Vargas-Whale R, Olson LM. Health and Health Needs of Children of Women Seeking Services for and Safety From Intimate Partner Violence. J Interpers Violence. 2021;36:NP1193–204NP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Campbell KA, Thomas AM, Cook LJ, Keenan HT. Resolution of intimate partner violence and child behavior problems after investigation for suspected child maltreatment. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167:236–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Cruz M, Cruz PB, Weirich C, McGorty R, McColgan MD. Referral patterns and service utilization in a pediatric hospital-wide intimate partner violence program. Child Abuse Negl. 2013;37:511–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Cross TP, Mathews B, Tonmyr L, Scott D, Ouimet C. Child welfare policy and practice on children’s exposure to domestic violence. Child Abuse Negl. 2012;36:210–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Wathen CN, Mantler T. Trauma- and Violence-Informed Care: Orienting Intimate Partner Violence Interventions to Equity. Curr Epidemiol Rep. 2022;9:233–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].McTavish JR, Chandra PS, Stewart DE, Herrman H, MacMillan HL. Child Maltreatment and Intimate Partner Violence in Mental Health Settings. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Pokharel B, Yelland J, Hooker L, Taft A. A Systematic Review of Culturally Competent Family Violence Responses to Women in Primary Care. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2021:15248380211046968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Henderson S, Horne M, Hills R, Kendall E. Cultural competence in healthcare in the community: A concept analysis. Health Soc Care Community. 2018;26:590–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.