Abstract

Background

Tobacco smoking increases frailty risk among the general population and is common among people with HIV (PWH), who experience higher rates of frailty at earlier ages than the general population.

Methods

We identified 8,608 PWH across 6 Centers for AIDS Research Network of Integrated Clinical Systems (CNICS) sites who completed ≥2 patient-reported outcome assessments, including a frailty phenotype measuring unintentional weight loss, poor mobility, fatigue, and inactivity, scored 0–4. Smoking was measured as baseline pack-years and time-updated never, former, or current use with cigarettes/day. We used Cox models to associate smoking with risk of incident frailty (score ≥3) and deterioration (frailty score increase by ≥2 points), adjusted for demographics, antiretroviral medication, and time-updated CD4 count.

Results

Mean follow-up of PWH was 5.3 years (median: 5.0), the mean age at baseline was 45 years, 15% were female, and 52% were non-White. At baseline, 60% reported current or former smoking. Current (HR: 1.79; 95%CI: 1.54–2.08) and former (HR: 1.31; 95%CI: 1.12–1.53) smoking were associated with higher incident frailty risk, as was higher pack-years. Current smoking (among younger PWH) and pack-years, but not former smoking, were associated with higher risk of deterioration.

Conclusion

Among PWH, smoking status and duration are associated with incident and worsening frailty.

Keywords: Frailty, Tobacco Smoking, People with HIV, HIV and aging

INTRODUCTION

Smoking is common among people with HIV (PWH)1,2, an estimated 42% of PWH engaged in care in the US smoke compared to 21% of the US adult population3. Smoking is a risk factor for many chronic diseases and mortality2,4,5 yet its role is understudied in the context of aging with HIV2,6,7. Advancements in HIV treatment have led to decreases in early mortality among PWH, and as such, the focus of care is shifting to prioritize healthy aging with an increased emphasis on aging-related disease, functional decline, and frailty, a multidimensional measure of decreased physiologic reserve and vulnerability to health stressors8–11. Frailty can be observed more often12–14 and at younger ages (comparable to a decade of aging)15–18 among PWH and is often attributed to chronic inflammation from HIV infection leading to immune system exhaustion12,17,19,20. Similarly, smoking increases the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and contributes to stress and declines in the immune system5,21,22. Together, smoking and HIV (in addition to other lifestyle and comorbidity factors11,23) could negatively impact aging of PWH, but published evidence thoroughly investigating this association is scarce.

In populations without HIV, smoking predicts worsening frailty24–27, but the relationship may differ by sex and age7,28,29. One study reported evidence of an association between smoking and frailty among men but not women28, while another found an association between smoking and frailty among men and women younger than 60, but nonsignificant associations among those 60 and older29. Whether these trends persist for PWH is unknown, but observed disparities in risky behaviors, frailty, and survival between men and women with HIV suggest possible differences7. The primary hypothesis linking smoking and frailty is that increased inflammation and physiologic stress caused by smoking contributes to immune system exhaustion, ultimately leading to frailty21,24,30–32. Specifically, reactive oxygen and nitrogen species caused by smoking induce a heightened inflammatory state and cellular senescence earlier than in the absence of smoking30. This cumulative oxidative stress is theorized to contribute to aging via loss of organ function over time and can lead to an increase in aging-related conditions30–33.

The combination of smoking- and HIV-induced chronic inflammation is concerning as both can contribute to ‘inflammaging’, a theory connecting inflammation to accelerated aging, characterized by earlier presentation of frailty and other aging-related conditions30,34,35. Among PWH, there is evidence that smoking-associated DNA methylation (a biomarker used to evaluate biological and chronological age34) was linked with frailty and mortality36, and smoking has been associated with higher levels of inflammatory markers (e.g., C reactive protein)22. In addition, cross-sectional studies have found evidence of a direct association between smoking and frailty37,38. Most of these studies have been limited by cross-sectional design29,37–39, small sample size for subgroups36,40,41, only measuring smoking by status of use24,25,27,28,37,41, or excluding PWH24–29,39,42. In light of these evidence gaps in the literature, we conducted a longitudinal study to estimate the associations between smoking status, intensity, and duration with the development and progression of physical frailty among a large, diverse population of PWH. We also focused specifically on age and sex in these analyses.

METHODS

Setting and Participants

This study was conducted within the Centers for AIDS Research Network of Integrated Clinical Systems (CNICS) cohort. CNICS is an ongoing study including PWH aged 18 years and older in care at 8 academic clinical sites in the US43. Six sites with relevant data were included in this study. The CNICS data repository integrates and harmonizes clinical data including laboratory values, diagnoses, and medications, as well as demographic information and patient reported outcome measures (PROs). The CNICS clinical PRO assessment are completed every ~6 months at routine clinic visits with electronic tablets and consists of validated survey instruments such as the HIV Symptom Index and substance use measures, and are offered in English, Spanish, and Amharic44.

PWH who completed at least 2 clinical PRO assessments, including both frailty and tobacco measures, between 1/2012–8/2021 were included in this study. Baseline was the date of the first completed PRO assessment within the study period including tobacco and frailty measures. For time-to-event models, follow-up ended at the earliest date of: 1) event occurrence, or 2) last visit in CNICS within the observation period. In some analyses we allowed follow-up time to include up to the last visit within the observation period rather than censoring at frailty incidence to allow for observation of frailty recovery. Time was measured as years since baseline. Institutional review boards at each site approved CNICS protocols and all participants completed informed consent prior to entry into CNICS.

Smoking

Smoking was collected in the PRO assessment. Time-varying smoking status was measured as never, former, or current use with intensity of smoking (the number of cigarettes smoked per day) among those reporting current use. Cigarettes smoked per day was centered at 10 per day so when status of use and intensity are modeled together, the interpretation for currently smoking represents someone who currently smokes 10 cigarettes per day. Pack-years of smoking was assessed at baseline for ever-smokers.

Frailty

Physical frailty was defined using a validated, modified version of Fried’s frailty phenotype45,46, an approach that has been used in prior HIV studies15,47,48. We defined physical frailty by scoring PWH from 0–4 based on the PRO responses using 4 of the 5 components of Fried’s phenotype: fatigue, low physical activity, poor mobility, and unintentional weight loss. The fifth component of Fried’s phenotype, weakness, was not collected in CNICS. Each component was dichotomized as present or absent then combined into a single score (Table S1). We defined 2 frailty events: 1) incident frailty (score ≥3) and 2) deterioration (increase of ≥2 points compared to baseline score), which were modeled separately (i.e., someone could experience both incident frailty and deterioration).

Covariates

Demographic information (e.g., age, birth sex, and race/ethnicity [Black, White, Hispanic, or Other]) is collected at initial CNICS visit. Additional covariates included baseline self-report of antiretroviral therapy (ART) use (yes/no) and time-updated CD4 cell count as a measure of immune status. We also collected baseline alcohol (measured by Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test Consumption [AUDIT-C])49 and recreational drug use (illicit opioids, methamphetamines, cocaine/crack, and marijuana measured by a modified World Health Organization Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test [ASSIST] instrument)50.

Statistical Analysis

We used Cox proportional hazards models to estimate the association between tobacco smoking and incident frailty, with the exposures of interest being 1) time-updated smoking status plus intensity of use (cigarettes smoked per day), and 2) baseline pack-years. These models were adjusted for demographic characteristics, ART use, and time-updated CD4 cell count. We stratified these models into 4 groups defined by sex and baseline age (dichotomized at 50, as is common in frailty studies among PWH19,51) to evaluate sex- and age-specific associations and understand whether differences observed in studies among the general population persist among PWH28,29. We conducted multiple sensitivity analyses, including assessing for interactions with smoking by age and sex (see Methods S1 in Supplementary Appendix) and adjusting for baseline alcohol and drug use. We repeated the main models to estimate the associations between smoking and incident deterioration of frailty score. This analysis was intended to supplement the main models and represent significant change in frailty status even if it does not reach the frail stage (i.e., transition from 0 to 2). PWH with baseline frailty scores ≥3 were excluded from all Cox models (both for incident frailty and deterioration). Proportional hazards for each model were tested using Schoenfeld residuals and in the case of violations, we stratified on the variable(s) of concern52,53. Collinearity between smoking measures was checked and the variance inflation factors were low, below 1.354.

We used linear mixed models (LMMs) to assess associations between smoking and frailty. LMMs utilize all available data (all baseline frailty scores) and allow for observation of increasing and decreasing frailty score without indicating a specific event/censoring as in Cox models55. We modeled log-transformed frailty scores as a linear function using LMMs with random intercepts and slopes for individuals, adjusting for demographic characteristics, ART use, site, time since baseline, and time-updated CD4 cell count. We exponentiated coefficients to represent the multiplicative increase in frailty score associated with each smoking exposure. We used separate models to estimate associations with 1) time-updated smoking status plus intensity of use, and 2) baseline pack-years of smoking for each subgroup. Analyses were performed using Stata version 17.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

RESULTS

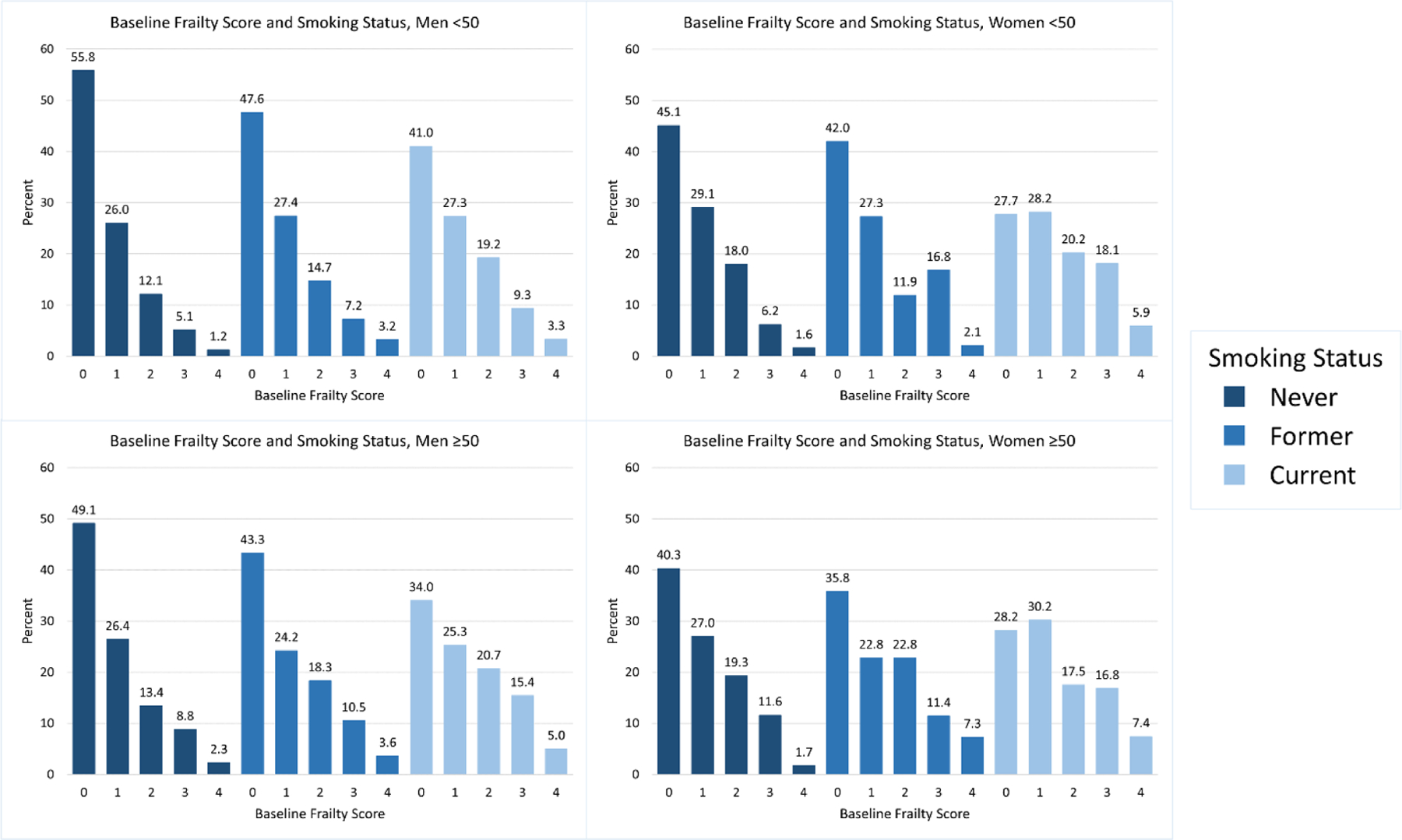

We identified a cohort of 8,608 PWH with complete information on smoking and frailty status at baseline and over follow-up. At baseline, 45% of PWH were not frail, 43% were prefrail, and 12% were frail as measured by our frailty phenotype, with mean follow-up time of 5.3 years (median: 5.0). The mean age at baseline was 45 years (median: 46) and 15% were female, while almost half (48%) were non-Hispanic White and 31% were non-Hispanic Black (Table 1). Sixty percent of PWH reported either former (29%) or current (31%) smoking at baseline (Table 1). Among all age and sex subgroups, more PWH who smoked (former or current) were frail (Figure 1). Baseline median frailty score was 1 for all the subgroups and follow-up time was similar across the groups as well as by baseline frailty status (mean 5.3–5.4 years, standard deviation: 2.7 years for all groups). There were 1,023 incident frailty cases over 37,310 person-years of follow-up: among PWH with a frailty score of 0–2 at baseline, the incidence rate of frailty was 27 per 1,000 person-years; the incidence rate was lower among men (26 per 1,000 person-years among 831 cases) than women (38 per 1,000 person-years among 192 cases). The incidence rate was lower among PWH under 50 years old (23 per 1,000 person-years among 396 cases) compared to PWH aged 50 and older (31 per 1,000 person-years among 627 cases).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of PWH by sex and age subgroup in CNICS, 2012–2021

| Characteristic | All | Men | Women | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <50 years | ≥50 years | <50 years | ≥50 years | ||

| N (%) | 8608 | 4687 (54) | 2647 (31) | 769 (9) | 505 (6) |

| Agea (years) | 45 (11) | 38 (8) | 57 (6) | 39 (7) | 57 (6) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||

| Black | 2643 (31) | 1264 (27) | 623 (24) | 424 (55) | 332 (66) |

| Hispanic | 1410 (16) | 947 (20) | 313 (12) | 111 (14) | 39 (8) |

| White | 4104 (48) | 2160 (46) | 1618 (61) | 205 (27) | 121 (24) |

| Other | 451 (5) | 316 (7) | 93 (4) | 29 (4) | 13 (3) |

| Smoking | |||||

| Never | 3493 (41) | 1826 (39) | 1046 (40) | 388 (50) | 233 (46) |

| Former | 2478 (29) | 1296 (28) | 916 (35) | 143 (19) | 123 (24) |

| Current | 2637 (31) | 1565 (33) | 685 (26) | 238 (31) | 149 (30) |

| Cigarettes per daya,b | 12 (8) | 12 (8) | 13 (9) | 11 (8) | 12 (9) |

| Pack-yearsa,c | 9 (9) | 7 (8) | 12 (11) | 7 (7) | 10 (9) |

| CD4 cell count (cells/mm3) | |||||

| ≥500 | 4896 (57) | 2559 (55) | 1523 (58) | 484 (63) | 330 (65) |

| 350–499 | 1619 (19) | 894 (19) | 500 (19) | 136 (18) | 89 (18) |

| <350 | 2093 (24) | 1234 (26) | 624 (24) | 149 (19) | 86 (17) |

| ART Use | 7519 (88) | 3964 (85) | 2441 (92) | 663 (86) | 451 (89) |

| HIV VL ≥200 copies/mL | 1441 (17) | 966 (21) | 274 (11) | 144 (19) | 57 (11) |

| Frailty Score | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 1.0 (1.1) | 0.9 (1.1) | 1.1 (1.2) | 1.1 (1.1) | 1.2 (1.2) |

| Median (IQR) | 1 (0–2) | 1 (0–1) | 1 (0–2) | 1 (0–2) | 1 (0–2) |

| Follow-up yrs | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 5.3 (2.7) | 5.3 (2.7) | 5.3 (2.7) | 5.2 (2.5) | 5.2 (2.5) |

| Median | 5.0 | 5.2 | 5.0 | 4.6 | 4.5 |

Abbreviations: antiretroviral therapy, ART; Centers for AIDS Research Network of Integrated Clinical Systems, CNICS; interquartile range, IQR; people with HIV, PWH; standard deviation, SD; viral load, VL

Mean (SD)

Among current smokers

Among ever-smokers

Figure 1. Distribution of baseline frailty score by baseline smoking status among people with HIV (PWH) by sex and age subgroup in CNICS, 2012–2021.

We graphed the proportion of PWH by their baseline frailty score and baseline smoking status, stratified by the 4 subgroups of interest by age and sex. PWH who reported never smoking had a greater proportion of lower frailty scores than PWH reporting former or current smoking. Additionally, older and female PWH had a greater proportion of higher frailty scores compared to their younger and male counterparts.

Abbreviations: Centers for AIDS Research Network of Integrated Clinical Systems, CNICS; people with HIV, PWH

Smoking status and cumulative burden of smoking (i.e., pack-years) were associated with both clinically and statistically significantly higher risks of incident frailty among PWH who were not frail or prefrail at baseline (Table 2). Former smoking was associated with a 31% higher risk of incident frailty (95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.12–1.53) and current smoking was associated with a 79% higher risk (95%CI: 1.54–2.08). Additionally, we observed a 12% greater risk of frailty for every 5 pack-years of smoking (95%CI: 1.09–1.16) (Table 2). When stratified into subgroups by age and sex, we observed generally similar associations, although with some loss of precision likely due to smaller sample sizes. Among women under 50, we observed a dose-response association with cigarettes per day, where every 10 additional cigarettes smoked was associated with a 47% higher risk of incident frailty (95%CI: 1.07–2.02). We evaluated interactions with smoking by sex and age and did not find evidence of effect measure modification (Tables S2–S4).

Table 2.

Associations between time-updated tobacco cigarette smoking and smoking intensity and baseline pack-years and incident frailty (score ≥3) among PWH in CNICS, stratified by age and sex

| Cohort | Variable | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | p-value | Proportional hazards |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Everyonea n=7,494 | Former Smoking | 1.31 (1.12–1.53) | <0.01 | 0.17 |

| Current Smoking | 1.79 (1.54–2.08) | <0.001 | ||

| + 10 cigarettes/dayb | 1.05 (0.93–1.19) | 0.43 | ||

| Everyonea n=7,438 | Pack-years (per 5) | 1.12 (1.09–1.16) | <0.001 | 0.38 |

| Men <50c n=4,205 | Former Smoking | 1.49 (1.17–1.89) | <0.01 | 0.18 |

| Current Smoking | 2.02 (1.61–2.52) | <0.001 | ||

| + 10 cigarettes/dayb | 1.03 (0.86–1.23) | 0.78 | ||

| Men <50c n=4,157 | Pack-years (per 5) | 1.13 (1.07–1.20) | <0.001 | 0.14 |

| Men ≥50c n=2,237 | Former Smoking | 1.26 (0.98–1.61) | 0.07 | 0.59 |

| Current Smoking | 1.53 (1.16–2.03) | <0.01 | ||

| + 10 cigarettes/dayb | 0.97 (0.76–1.23) | 0.80 | ||

| Men ≥50c n=2,197 | Pack-years (per 5) | 1.10 (1.05–1.16) | <0.001 | 0.62 |

| Women <50c n=643 | Former Smoking | 1.15 (0.67–1.98) | 0.60 | 0.73 |

| Current Smoking | 1.72 (1.11–2.65) | 0.02 | ||

| + 10 cigarettes/dayb | 1.47 (1.07–2.02) | 0.02 | ||

| Women <50c n=639 | Pack-years (per 5) | 1.18 (1.05–1.34) | 0.01 | 0.75 |

| Women ≥50c n=409 | Former Smoking | 0.86 (0.45–1.64) | 0.65 | 0.52 |

| Current Smoking | 1.89 (1.13–3.13) | 0.01 | ||

| + 10 cigarettes/day b | 0.98 (0.62–1.52) | 0.91 | ||

| Women ≥50c n=404 | Pack-years (per 5) | 1.11 (0.99–1.25) | 0.08 | 0.51 |

Abbreviations: antiretroviral therapy, ART; Centers for AIDS Research Network of Integrated Clinical Systems, CNICS; people with HIV, PWH

Adjusted for sex, age, race/ethnicity, ART use, and time updated CD4 cell count

Cigarettes/day centered at 10

Adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, ART use, and time updated CD4 cell count

In sensitivity analyses adjusting for baseline alcohol use, we observed similar associations (Table S5). When we adjusted for recreational drug use, there was some attenuation of the associations, but interpretations generally remained consistent with the main models (Table S6). There was concern regarding small sample size, discussed in Results S1.

We estimated the association between smoking status and deterioration stratified by age due to violation of proportional hazards. Among PWH <50, current smoking was associated with a 40% higher risk of deterioration compared to never smoking (95%CI: 1.17–1.68), as well as a 17% higher risk associated with smoking an additional 10 cigarettes per day (95%CI: 1.01–1.37) (Table 3). We did not observe these associations among PWH ≥50. Among all ages, there was no greater risk of deterioration associated with former smoking. Among all PWH, every 5 pack-years smoking was associated with a 6% higher risk of deterioration (95%CI: 1.02–1.09) (Table 3). Subgroup results are presented in Table S7 and Results S2.

Table 3.

Associations between time-updated tobacco cigarette smoking and smoking intensity and baseline pack-years and increasing frailty at least 2 points (deterioration) among PWH in CNICS

| Cohort | Variable | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | p-value | Proportional hazards |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Everyonea n=7,526 | Former Smoking | 1.05 (0.90–1.21) | 0.54 | 0.01 |

| Current Smoking | 1.30 (1.12–1.50) | <0.001 | ||

| + 10 cigarettes/dayb | 1.10 (0.97–1.24) | 0.15 | ||

| Everyonea n=7,429 | Pack-years (per 5) | 1.06 (1.02–1.09) | <0.01 | 0.07 |

| PWH <50a n=4,860 | Former Smoking | 1.10 (0.91–1.34) | 0.32 | 0.12 |

| Current Smoking | 1.40 (1.17–1.68) | <0.001 | ||

| + 10 cigarettes/dayb | 1.17 (1.01–1.37) | 0.04 | ||

| PWH ≥50a n=2,666 | Former Smoking | 0.98 (0.79–1.22) | 0.88 | 0.08 |

| Current Smoking | 1.15 (0.90–1.46) | 0.26 | ||

| + 10 cigarettes/dayb | 0.97 (0.78–1.22) | 0.82 |

Abbreviations: antiretroviral therapy, ART; Centers for AIDS Research Network of Integrated Clinical Systems, CNICS; people with HIV, PWH

Adjusted for sex, age, race/ethnicity, ART use, and time updated CD4 cell count

Cigarettes/day centered at 10

In LMMs, which included PWH with all baseline frailty scores, all measures of smoking were associated with increasing frailty scores over follow-up (Table 4, discussed in Results S3). Current smoking was associated with a 1.15-times higher frailty score over the study period (95%CI: 1.10–1.21) (Table 4). Intensity of smoking (cigarettes per day) was associated with frailty, likely due to an increase in statistical power in LMMs compared to survival models. The subgroup results were similar to the pooled results, with some fluctuations in estimates and precision but consistent interpretations (Table S8).

Table 4.

Estimated frailty change associated with time-updated tobacco cigarette smoking, smoking intensity, and baseline pack-years among PWH in CNICS

| Variable | Relative Risk (95% CI)c | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Everyonea n=8,565 | Former Smoking | 1.09 (1.05–1.13) | <0.001 |

| Current Smoking | 1.15 (1.10–1.21) | <0.001 | |

| + 10 cigarettes/dayb | 1.03 (1.01–1.06) | 0.02 | |

| Everyonea n=8,464 | Pack-years (per 5) | 1.07 (1.05–1.08) | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: antiretroviral therapy, ART; Centers for AIDS Research Network of Integrated Clinical Systems, CNICS; people with HIV, PWH

Adjusted for sex, age, race/ethnicity, ART use, CNICS site, time in study, and time updated CD4 cell count

Cigarettes/day centered at 10

Exponentiated log-linear coefficients, representing the multiplicative increase in frailty score associated with exposure, i.e., relative risk

DISCUSSION

We found strong evidence of a higher risk of physical frailty associated with tobacco smoking in a large, diverse cohort of PWH in the US. Former and current smoking were associated with 31% and 79% higher risks of incident frailty, respectively. Moreover, every 5 pack-years smoking was associated with a 12% higher risk of frailty. Furthermore, in analyses estimating the risk of deterioration, we found that current smoking among PWH <50 years old and more pack-years of smoking (among all ages) were associated with higher risk of deterioration. Former smoking, however, was not associated with a higher risk of deterioration, suggesting smoking cessation could reduce the risk of worsening frailty. This study expands upon the limited literature on this topic by including subgroup analyses (i.e., age, sex), multiple measures of smoking (i.e., status, intensity, and pack-years), and significant follow-up (average >5 years). In addition, we evaluated these relationships in multiple models to understand both incidence and deterioration of frailty, as well as changes in score over time to account for improvement.

We focused analyses on subgroups by age and sex due to possible important differences regarding both exposure to smoking (e.g., patterns/severity of use) as well as physiologic pathways of frailty development. Further, subgrouping is useful to understand which groups may benefit most from certain smoking cessation interventions56. Our approach was similar to that of DeClercq et al.29 except we dichotomized age at 50 years (vs. 60) based on the relevance of PWH experiencing frailty at younger ages15,17,18. We observed some variability in estimates between subgroups but overall did not find evidence of effect measure modification by age or sex. Our results consistently suggest that smoking is associated with a higher risk of frailty among all subgroups and support the notion that smoking cessation is beneficial for healthy aging among PWH. We did, however, find that women, particularly young women with higher smoking intensity, may experience the worst frailty outcomes associated with smoking, possibly due to biological differences from sex or age, or from differential behaviors that otherwise increase the risk of frailty (discussed further in the Discussion of the Supplementary Appendix).

Our analysis evaluating the risk of deterioration of frailty score offers an alternative perspective on the progression of frailty by considering baseline frailty status and modeling a standard change in score as well as novel findings regarding the association between smoking cessation and deterioration of frailty score. Notably, we observed that former smoking was not associated with a risk of deterioration, while there was some risk associated with cumulative burden and currently smoking among younger PWH. A meta-analysis evaluating smoking and frailty among the general population found no difference between the risk of frailty among former and never smokers and concluded that cessation may reduce frailty risk66. Our results are less conclusive, given the observation of cumulative associations between smoking and deterioration risk, but the lack of association between former smoking and deterioration suggests there may be cases where cessation helps mitigate the risk of frailty progression. In addition, the differences in associations between age strata support the notion that older PWH who had not already experienced a deterioration in physical health, and thus were included in these analyses, may have been more resilient for some reason and maintained their health status.

Our findings highlight the complexities of frailty as a disease state, as well as the multiple pathways that smoking may operate through to increase frailty risk. We hypothesize that the mechanism between smoking and frailty is largely affected by long-term cumulative effects of smoking, including inflammation, as well as the presence of other comorbidities, but may be mitigated through quitting followed by some degree of reduction in levels of inflammatory markers22,67 and risks of comorbidities68,69. Among PWH in the Strategies for Management of Antiretroviral Therapy (SMART) trial, current smoking was found to contribute to 25% of cardiovascular disease, 31% of non-AIDS cancer, and 24% to overall mortality69. Additionally, an analysis within the Data collection on Adverse Events of Anti-HIV Drugs (D:A:D) study found risks of cardiovascular disease to further decrease as time since quitting smoking increased68. Whether this trend persists for frailty risk is currently unknown, but our results and the existing literature nonetheless suggest benefit of smoking reductions or cessation on frailty risk22. While we measured frailty via phenotype, which differentiates it clinically from other diseases and disability, the accumulation of deficits model of capturing frailty relies on enumerating present comorbidities70, directly linking these conditions to frailty26. Even though we do not take this approach or adjust for comorbidities, the presence of comorbidities likely influences the presence and degree of frailty (measured by phenotype) as well through deterioration of physiologic reserve and polypharmacy contributing to declines in overall health18,27,45,48.

CNICS boasts both geographic and demographic diversity among a large cohort of PWH, allowing for subgroup analyses by sex and age. Additionally, we had sufficient follow-up to observe changes in frailty status over time, while many prior studies have only been able to conduct cross-sectional analyses. We also included multiple ways of measuring smoking as an exposure. Similarly, we considered multiple approaches to quantify changes in frailty, by incidence of becoming frail, a deterioration of frailty score, and changes in score.

Our study has an important focus on PWH engaged in HIV care in the US, but results may not be generalizable to other populations. We focused on tobacco cigarette smoking, thus did not capture other smoking behaviors such as cigars or vaping. We focused analyses on evaluating the association of interest among subgroups, however, that resulted in small sample sizes for some groups. This particularly impacted sensitivity analysis models that were unable to produce estimates due to violations of positivity. Similarly, we were unable to differentiate between individual recreational drugs while preserving power, so we used a composite variable. Our frailty phenotype is self-reported and, while validated, includes 4 of the 5 original components included in Fried’s frailty phenotype (missing weakness)46. There may be unmeasured confounding of this relationship, as we did not have data on socioeconomic status, which may increase the likelihood of smoking as well as frailty24,71. Additionally, we did not have enough participants to incorporate transgender status, which could be associated with hormone use and affect frailty risk59.

Conclusion

We found strong evidence of a higher risk of physical frailty associated with smoking among PWH. Both current and former smoking were associated with a greater risk of frailty, as well as cumulative burden (i.e., pack-years). We also provide evidence of a higher risk of deterioration of frailty score associated with current and cumulative smoking, but not former smoking, suggesting benefit of cessation. Future studies to advance our understanding of this relationship and investigate the role of cessation should evaluate inflammatory biomarkers, recreational drug use, transitions in frailty, measure time since quitting smoking, and continue to consider sex and age subgroups.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

The authors acknowledge all CNICS participants and study personnel for their essential contributions to this work.

Sources of Funding:

This work was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (grant U18HS026154); the National Institute on Aging (grant R33AG067069); the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (grant R24 AI067039); the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (grants U01AA020793 and P01AA029544-01); and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (grant R01DA047045).

Footnotes

Findings were presented in part at: International Conference on Pharmacoepidemiology and Therapeutic Risk Management (ICPE 2022), August 24–28, 2022, Copenhagen, Denmark

Statistical code is available on request to ruderman@uw.edu. Data from CNICS may be shared with investigators with an approved concept proposal. Instructions for data access and concept proposal forms may be found at: https://www.uab.edu/cnics/submit-proposal.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors report no potential conflicts of interest, including relevant financial interests, activities, relationships, and affiliations.

References

- 1.Johnston PI, Wright SW, Orr M, et al. Worldwide relative smoking prevalence among people living with and without HIV. AIDS. 2021;35(6):957–970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Helleberg M, May MT, Ingle SM, et al. Smoking and life expectancy among HIV-infected individuals on antiretroviral therapy in Europe and North America. AIDS. 2015;29(2):221–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mdodo R, Frazier EL, Dube SR, et al. Cigarette smoking prevalence among adults with HIV compared with the general adult population in the United States: cross-sectional surveys. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(5):335–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Helleberg M, Afzal S, Kronborg G, et al. Mortality attributable to smoking among HIV-1-infected individuals: a nationwide, population-based cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56(5):727–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arnson Y, Shoenfeld Y, Amital H. Effects of tobacco smoke on immunity, inflammation and autoimmunity. J Autoimmun. 2010;34(3):J258–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Petoumenos K, Law MG. Smoking, alcohol and illicit drug use effects on survival in HIV-positive persons. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2016;11(5):514–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Womack JA, Justice AC. The OATH Syndemic: opioids and other substances, aging, alcohol, tobacco, and HIV. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2020;15(4):218–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clegg A, Young J, Iliffe S, Rikkert MO, Rockwood K. Frailty in elderly people. Lancet. 2013;381(9868):752–762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morley JE, Vellas B, van Kan GA, et al. Frailty consensus: a call to action. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013;14(6):392–397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rodriguez-Manas L, Feart C, Mann G, et al. Searching for an operational definition of frailty: a Delphi method based consensus statement: the frailty operative definition-consensus conference project. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2013;68(1):62–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lang PO, Michel JP, Zekry D. Frailty syndrome: a transitional state in a dynamic process. Gerontology. 2009;55(5):539–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brothers TD, Rockwood K. Biologic aging, frailty, and age-related disease in chronic HIV infection. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2014;9(4):412–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bloch M Frailty in people living with HIV. AIDS Res Ther. 2018;15(1):19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kooij KW, Wit FW, Schouten J, et al. HIV infection is independently associated with frailty in middle-aged HIV type 1-infected individuals compared with similar but uninfected controls. AIDS. 2016;30(2):241–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Desquilbet L, Jacobson LP, Fried LP, et al. HIV-1 infection is associated with an earlier occurrence of a phenotype related to frailty. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62(11):1279–1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Levett TJ, Cresswell FV, Malik MA, Fisher M, Wright J. Systematic Review of Prevalence and Predictors of Frailty in Individuals with Human Immunodeficiency Virus. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(5):1006–1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Montano M, Oursler KK, Xu K, Sun YV, Marconi VC. Biological ageing with HIV infection: evaluating the geroscience hypothesis. The Lancet Healthy Longevity. 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Althoff KN, Jacobson LP, Cranston RD, et al. Age, comorbidities, and AIDS predict a frailty phenotype in men who have sex with men. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2014;69(2):189–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wing EJ. HIV and aging. Int J Infect Dis. 2016;53:61–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Falutz J Frailty in People Living with HIV. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2020;17(3):226–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goncalves RB, Coletta RD, Silverio KG, et al. Impact of smoking on inflammation: overview of molecular mechanisms. Inflamm Res. 2011;60(5):409–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Poudel KC, Poudel-Tandukar K, Bertone-Johnson ER, Pekow P, Vidrine DJ. Inflammation in Relation to Intensity and Duration of Cigarette Smoking Among People Living with HIV. AIDS Behav. 2021;25(3):856–865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brinkman S, Voortman T, Kiefte-de Jong JC, et al. The association between lifestyle and overall health, using the frailty index. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2018;76:85–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kojima G, Iliffe S, Walters K. Smoking as a predictor of frailty: a systematic review. BMC Geriatr. 2015;15:131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kojima G, Iliffe S, Jivraj S, Liljas A, Walters K. Does current smoking predict future frailty? The English longitudinal study of ageing. Age Ageing. 2018;47(1):126–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hubbard RE, Searle SD, Mitnitski A, Rockwood K. Effect of smoking on the accumulation of deficits, frailty and survival in older adults: a secondary analysis from the Canadian Study of Health and Aging. J Nutr Health Aging. 2009;13(5):468–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hanlon P, Nicholl BI, Jani BD, Lee D, McQueenie R, Mair FS. Frailty and pre-frailty in middle-aged and older adults and its association with multimorbidity and mortality: a prospective analysis of 493 737 UK Biobank participants. Lancet Public Health. 2018;3(7):e323–e332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang C, Song X, Mitnitski A, et al. Gender differences in the relationship between smoking and frailty: results from the Beijing Longitudinal Study of Aging. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2013;68(3):338–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.DeClercq V, Duhamel TA, Theou O, Kehler S. Association between lifestyle behaviors and frailty in Atlantic Canadian males and females. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2020;91:104207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liguori I, Russo G, Curcio F, et al. Oxidative stress, aging, and diseases. Clin Interv Aging. 2018;13:757–772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.In: How Tobacco Smoke Causes Disease: The Biology and Behavioral Basis for Smoking-Attributable Disease: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta (GA)2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.In: The Health Consequences of Smoking-50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta (GA)2014. [Google Scholar]

- 33.El Assar M, Angulo J, Rodriguez-Manas L. Frailty as a phenotypic manifestation of underlying oxidative stress. Free Radic Biol Med. 2020;149:72–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Franceschi C, Garagnani P, Parini P, Giuliani C, Santoro A. Inflammaging: a new immune-metabolic viewpoint for age-related diseases. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2018;14(10):576–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.De la Fuente M, Miquel J. An update of the oxidation-inflammation theory of aging: the involvement of the immune system in oxi-inflamm-aging. Curr Pharm Des. 2009;15(26):3003–3026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang X, Hu Y, Aouizerat BE, et al. Machine learning selected smoking-associated DNA methylation signatures that predict HIV prognosis and mortality. Clin Epigenetics. 2018;10(1):155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Erlandson KM, Fitch KV, McCallum SA, et al. Geographical Differences in the Self-Reported Functional Impairment of People with HIV and Associations with Cardiometabolic Risk. Clin Infect Dis. 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ruderman SA, Whitney BM, Nance RM, et al. Associations between frailty and clinical characteristics, comorbidities, and substance use among people living with HIV. International Workshop on HIV & Aging 2020; 2020; Virtual [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shin J, Kim KJ, Choi J. Smoking, alcohol intake, and frailty in older Korean adult men: cross-sectional study with nationwide data. Eur Geriatr Med. 2020;11(2):269–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brothers TD, Kirkland S, Theou O, et al. Predictors of transitions in frailty severity and mortality among people aging with HIV. PLoS One. 2017;12(10):e0185352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Erlandson KM, Wu K, Koletar SL, et al. Association Between Frailty and Components of the Frailty Phenotype With Modifiable Risk Factors and Antiretroviral Therapy. J Infect Dis. 2017;215(6):933–937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Niederstrasser NG, Rogers NT, Bandelow S. Determinants of frailty development and progression using a multidimensional frailty index: Evidence from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. PLoS One. 2019;14(10):e0223799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kitahata MM, Rodriguez B, Haubrich R, et al. Cohort profile: The Centers for AIDS Research Network of Integrated Clinical Systems. Int J Epidemiol. 2008;37(5):948–955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fredericksen R, Crane PK, Tufano J, et al. Integrating a web-based, patient-administered assessment into primary care for HIV-infected adults. J AIDS HIV Res. 2012;4(2):47–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56(3):M146–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ruderman SA, Webel AR, Willig AL, et al. Validity Properties of a Self-reported Modified Frailty Phenotype Among People With HIV in Clinical Care in the United States. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Akgun KM, Tate JP, Crothers K, et al. An adapted frailty-related phenotype and the VACS index as predictors of hospitalization and mortality in HIV-infected and uninfected individuals. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;67(4):397–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sung M, Gordon K, Edelman EJ, Akgun KM, Oursler KK, Justice AC. Polypharmacy and frailty among persons with HIV. AIDS Care. 2021;33(11):1492–1499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bradley KA, Bush KR, Epler AJ, et al. Two brief alcohol-screening tests From the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): validation in a female Veterans Affairs patient population. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(7):821–829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Group WAW. The Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST): development, reliability and feasibility. Addiction. 2002;97(9):1183–1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McMillan JM, Gill MJ, Power C, Fujiwara E, Hogan DB, Rubin LH. Construct and Criterion-Related Validity of the Clinical Frailty Scale in Persons With HIV. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2021;88(1):110–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hess KR. Graphical methods for assessing violations of the proportional hazards assumption in Cox regression. Stat Med. 1995;14(15):1707–1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.George B, Seals S, Aban I. Survival analysis and regression models. J Nucl Cardiol. 2014;21(4):686–694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kim JH. Multicollinearity and misleading statistical results. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2019;72(6):558–569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Diggle PJ. An approach to the analysis of repeated measurements. Biometrics. 1988;44(4):959–971. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Corraini P, Olsen M, Pedersen L, Dekkers OM, Vandenbroucke JP. Effect modification, interaction and mediation: an overview of theoretical insights for clinical investigators. Clin Epidemiol. 2017;9:331–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Austad SN, Fischer KE. Sex Differences in Lifespan. Cell Metab. 2016;23(6):1022–1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Oksuzyan A, Crimmins E, Saito Y, O’Rand A, Vaupel JW, Christensen K. Cross-national comparison of sex differences in health and mortality in Denmark, Japan and the US. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25(7):471–480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Austad SN. Why women live longer than men: sex differences in longevity. Gend Med. 2006;3(2):79–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Oksuzyan A, Juel K, Vaupel JW, Christensen K. Men: good health and high mortality. Sex differences in health and aging. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2008;20(2):91–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Meyer JP, Springer SA, Altice FL. Substance abuse, violence, and HIV in women: a literature review of the syndemic. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2011;20(7):991–1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Feldman JG, Minkoff H, Schneider MF, et al. Association of cigarette smoking with HIV prognosis among women in the HAART era: a report from the women’s interagency HIV study. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(6):1060–1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Barrett SP, Darredeau C, Pihl RO. Patterns of simultaneous polysubstance use in drug using university students. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2006;21(4):255–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hileman CO, McComsey GA. The Opioid Epidemic: Impact on Inflammation and Cardiovascular Disease Risk in HIV. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2019;16(5):381–388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Graham JE, Christian LM, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. Stress, age, and immune function: toward a lifespan approach. J Behav Med. 2006;29(4):389–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Amiri S, Behnezhad S. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the association between smoking and the incidence of frailty. Neuropsychiatr. 2019;33(4):198–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.McElroy JP, Carmella SG, Heskin AK, et al. Effects of cessation of cigarette smoking on eicosanoid biomarkers of inflammation and oxidative damage. PLoS One. 2019;14(6):e0218386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Petoumenos K, Worm S, Reiss P, et al. Rates of cardiovascular disease following smoking cessation in patients with HIV infection: results from the D:A:D study(*). HIV Med. 2011;12(7):412–421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lifson AR, Neuhaus J, Arribas JR, et al. Smoking-related health risks among persons with HIV in the Strategies for Management of Antiretroviral Therapy clinical trial. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(10):1896–1903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mitnitski AB, Mogilner AJ, Rockwood K. Accumulation of deficits as a proxy measure of aging. ScientificWorldJournal. 2001;1:323–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hiscock R, Bauld L, Amos A, Fidler JA, Munafo M. Socioeconomic status and smoking: a review. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2012;1248:107–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.