Abstract

Objective:

We evaluated PrEP initiation, persistence, and adherence measured via tenofovir-diphosphate (TFV-DP) concentrations in dried blood spots (DBS) among women offered PrEP during pregnancy.

Methods:

We prospectively analyzed data from participants in the PrIMA Study (NCT03070600) who were offered PrEP during the 2nd trimester and followed through 9-months postpartum. At follow-up visits (monthly in pregnancy; 6 weeks, 6 months, 9 months postpartum), self-reported PrEP use was assessed, and DBS were collected for quantifying TFV-DP concentrations.

Results:

In total, 2949 participants were included in the analysis. At enrollment, median age was 24 years (IQR 21–29), gestational age 24 weeks (IQR 20–28), and 4% had a known partner living with HIV. Overall, 405 (14%) participants initiated PrEP in pregnancy with higher frequency among those with risk factors for HIV acquisition, including >2 lifetime sexual partners, syphilis during pregnancy, forced sex, and intimate partner violence (p<0.05). At 9-months postpartum, 58% of PrEP initiators persisted with PrEP use, of which 54% self-reported not missing any PrEP pills in the last 30 days. Among DBS randomly selected from visits where participants persisted with PrEP (n=427), 50% had quantifiable TFV-DP. Quantifiable TFV-DP was twice as likely in pregnancy than postpartum (aRR=1.90, 95% CI 1.40–2.57, p<0.001). Having a partner known to be living with HIV was the strongest predictor of PrEP initiation, persistence, and quantifiable TFV-DP (p<0.001).

Conclusions:

PrEP persistence and adherence waned postpartum, though over half of PrEP initiators persisted through 9-months postpartum. Interventions should prioritize increasing knowledge of partner HIV status and sustaining adherence in the postpartum period.

INTRODUCTION

High HIV incidence among young cisgender women in East and Southern Africa persists during pregnancy1 and HIV acquisition risk increases by 2-fold during pregnancy and the postpartum period compared to non-pregnant periods.2–5 The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends offering daily oral tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF)-based pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) to pregnant and lactating people at substantial risk for HIV.6–9 PrEP delivery is scaling up in East and Southern Africa with notable uptake successes in PrEP implementation among pregnant women in Kenya and ongoing demonstration projects in South Africa, Lesotho, Malawi, Zambia and Zimbabwe.6,10–14 Up to 79% of pregnant women with characteristics associated with HIV acquisition, such as having a male partner known to be living with HIV, accept PrEP pills when offered within routine antenatal care in Kenya.15 Few data exist on longitudinal PrEP use patterns after PrEP is initiated during pregnancy and available evidence suggests early and frequent PrEP discontinuation.15

PrEP effectiveness depends on adherence16–18, yet taking daily oral PrEP is challenging and the transitional periods of pregnancy and postpartum present unique PrEP adherence barriers.10,19,20 In qualitative studies, motivation for PrEP use during pregnancy was driven by the desire to prevent HIV transmission to infants.21,22 PrEP adherence may be reduced postpartum if perception of the infant’s HIV risk is reduced, similar to waning adherence patterns among women living with HIV (WLHIV) receiving antiretroviral therapy (ART).23,24 Additionally, common symptoms of pregnancy overlap with PrEP-related side effects, which may negatively impact adherence in pregnancy.21,22 Existing data suggest PrEP adherence, measured via self-report, is suboptimal among pregnant women in Kenya.25–27 Longitudinal data on PrEP initiation, persistence, and adherence among pregnant women could help elucidate the PrEP continuum of care in this unique population and identify opportunities for promoting PrEP use among those most likely to benefit.

We prospectively analyzed data from participants enrolled in the PrEP Implementation for Mothers in Antenatal Care (PrIMA) study to quantify and identify cofactors of PrEP initiation, persistence, and adherence among cisgender Kenyan women offered PrEP during pregnancy who were followed until 9-months postpartum. Our overall objective was to expand evidence on the PrEP continuum of care among pregnant and postpartum Kenyan women and inform strategies for enhancing PrEP use in this population.

METHODS

Study population and setting

The PrIMA Study protocol has been previously described (NCT03070600).28 Briefly, the PrIMA Study was a cluster randomized trial conducted between January 2018 and July 2021 that evaluated PrEP delivery models (universal vs. risk-based PrEP offer) among pregnant cisgender women attending 20 antenatal care (ANC) clinics in Siaya and Homa Bay, Kenya–a region with a HIV prevalence of 20% among women.29,30 ANC attendees were eligible for enrollment if they were currently pregnant, HIV-negative, not currently using PrEP, ≥15 years old, tuberculosis negative, planned to reside in the region for at least 1-year postpartum, planned to receive postnatal care at the study facility, and were not enrolled in another study.

Study procedures

At enrollment, participants had confirmatory HIV testing. At clinics assigned to the universal PrEP offer arm, participants received PrEP counselling using a standardized script which included a list of behaviors associated with HIV acquisition and considerations for PrEP use, after which participants decided whether to initiate PrEP. At clinics assigned to risk-based PrEP offer, participants were assessed for HIV acquisition risk using an empiric HIV risk scoring tool validated to predict HIV risk in Kenyan pregnant and postpartum women31; only those determined to be at high risk (risk scores >6) were offered PrEP. In both arms, participants who elected to use PrEP were assessed for PrEP medical eligibility (based on Kenya Ministry of Health guidelines);32 <1% of participants were medically ineligible for PrEP in the parent study. Participants in the risk-based PrEP offer arm were also offered HIV self-test kits (HIVST) for use with their partners. During the study period, the Kenya Ministry of Health introduced offer of partner HIVSTs to women attending ANC; thus, data on HIVST uptake was collected in both study arms. Participants had monthly study visits during antenatal care, followed by postnatal care visits at 6 weeks, 14 weeks, 6 months, and 9 months postpartum aligned with Kenyan national guidelines.

Data collection

At enrollment, questionnaires were administered on sociodemographic and psychosocial characteristics, self-efficacy, behaviors associated with HIV acquisition and HIV risk perception, partnership characteristics, intimate partner violence (IPV) using the Hurt, Insult, Threaten, Scream (HITS) scale,33 PrEP knowledge, partner HIV status, and obstetric history. At follow-up visits, experience of PrEP-related side effects (e.g., nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, etc.) was collected. Self-reported PrEP adherence was assessed by ascertaining the number of missed doses in the past 30 days. Information on partner HIV status self-test outcomes were self-reported by participants.

Laboratory procedures

Participants received HIV testing at all study visits following Kenyan national guidelines. Dried blood spots (DBS) were collected for tenofovir diphosphate (TFV-DP) quantification by study nurses who received standardized training on DBS collection via fingerstick. Previous studies demonstrated that DBS from fingerstick and venipuncture can be used for TFV-DP quantification.34 DBS were transported to a central −20C freezer for storage within a 48-hour window after collection. DBS were collected at all follow-up visits for participants who accepted PrEP.

DBS were tested for TFV-DP in red blood cells using validated ultra-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) methods at the University of Colorado.35 Values below the lower limit of quantification for TFV-DP (25 fmol/punch) were considered unquantifiable.34 TFV-DP has a half-life of 17 days in red blood cells and DBS provides a marker of cumulative adherence over the prior 1–2 months once steady state is achieved (typically 1 month).34 TFV-DP concentration results were not returned to participants as TFV-DP quantification is not an approved clinical test in Kenya.

Analysis

Participants were included in the current analysis if they enrolled during the 2nd trimester to allow for similar follow-up time in pregnancy, were followed until 9-months after their pregnancy end date, and remained HIV-negative throughout follow-up. PrEP initiation, persistence, and adherence were evaluated as primary outcomes in the current analysis. Confirmed PrEP initiation was defined as participant-report of swallowing PrEP pills at a follow-up visit after PrEP acceptance at a prior visit. PrEP persistence was assessed at every follow-up visit and defined as participant report of continuing with PrEP medication. At each follow-up visit, self-reported PrEP adherence was dichotomized as those who reported no missed doses versus those who reported missing any doses in the past 30 days. Among a randomly selected subset of PrEP users, PrEP adherence was also defined using TFV-DP concentrations with TFV-DP for DBS collected from visits with self-reported PrEP use. We summarized frequency of having any quantifiable TFV-DP and also the distribution of adherence benchmarks established in IMPAACT 2009 for pregnant and postpartum women (e.g., ≥600 fmol/punch indicating ~7 doses/week) who used directly-observed daily oral TDF/FTC-based PrEP for >4 weeks).36

We used univariate Poisson regression models with clustering by site to identify potential correlates of PrEP initiation, persistence, and adherence by comparing characteristics between: 1) women who initiated PrEP vs. those who did not initiate PrEP, 2) women who persisted with PrEP use until 9-months postpartum (i.e., never stopped PrEP use) vs. those who discontinued and did not restart among those who initiated, and 3) women with quantifiable TFV-DP levels vs. those with unquantifiable levels and/or those who discontinued or did not report PrEP use among the random subset. We also compared the subsets for analyses of each respective outcome with the overall PrIMA study population and sub-group of PrEP initiators to evaluate representativeness. Multivariable models were adjusted for age (years), primigravity (yes/no), education (<12 vs. ≥12 years), and partner HIV status (positive, negative, or unknown) based on the known association of these characteristics with PrEP use outcomes.13,37 We conducted exploratory analyses to evaluate trajectories of PrEP persistence among the subset of participants who had complete self-reported adherence information and attended all postpartum follow-up visits. We also evaluated trajectories of PrEP adherence among the subset of participants who had more than one visit randomly selected for TFV-DP quantification. All analyses were conducted using Stata SE 17.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Considerations for human subjects

Protocols were approved by the Kenyatta National Hospital-University of Nairobi Ethics and Research Committee (P73/02/2017) and University of Washington Institutional Review Board (STUDY00000438). All participants provided written informed consent.

RESULTS

Overall, 2949 participants enrolled during the 2nd trimester, were followed through 9-months postpartum, and met inclusion criteria for the current analysis; there were no appreciable differences between participants included in this analysis and overall PrIMA participants (Supplemental Material). The median age was 24.2 years (interquartile range [IQR] 21.0–28.6), 5.6% were ≤18 years, and 14.4% were formally employed (Table 1). The median gestational age at enrollment was 24 weeks (IQR 20–28), 22.9% were primigravida, and 4.3% had a partner known to be living with HIV.

Table 1.

Demographic, clinical, and behavioral characteristics of participants offered PrEP between 14–32 weeks gestation (n=2949)

| N | n (%) or Median (IQR) | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Demographic characteristics | ||

|

| ||

| Study arm | 2949 | |

| Universal PrEP offer | 1488 (50.5) | |

| Targeted PrEP offer | 1461 (49.5) | |

|

| ||

| Age (years) | 2948 | 24.2 (21.0, 28.6) |

|

| ||

| Age category (years) | 2948 | |

| <24 | 1392 (47.2) | |

| ≥24 | 1556 (52.8) | |

|

| ||

| Currently married | 2914 | 2527 (86.7) |

|

| ||

| Education (years) | 2886 | 10 (8, 12) |

|

| ||

| Education category (years) | 2886 | |

| <12 | 1843 (63.9) | |

| ≥12 | 1043 (36.1) | |

|

| ||

| Regular employment | 2904 | 418 (14.4) |

|

| ||

| People per room | 2917 | 1.7 (1, 2.5) |

|

| ||

| 2+ people per room | 2917 | 1428 (49.0) |

|

| ||

| Pregnancy characteristics | ||

|

| ||

| Gestational age at enrollment (weeks) | 2949 | 24 (20, 28) |

|

| ||

| Previous pregnancy | 2934 | 2261 (77.1) |

|

| ||

| Previous abortion/miscarriage | 2930 | 314 (10.7) |

|

| ||

| Previous premature birth (<37 weeks) | 2949 | 30 (1.0) |

|

| ||

| Behavioral characteristics | ||

|

| ||

| No. of lifetime sexual partners | 2939 | 2 (2, 3) |

|

| ||

| HIV status of primary sexual partner(s) | 2942 | |

| Positive | 126 (4.3) | |

| Negative | 1880 (63.9) | |

| Unknown | 902 (30.7) | |

| No male partner | 34 (1.2) | |

|

| ||

| Partner on ART if HIV-positive | 121 | 116 (95.9) |

|

| ||

| Syphilis Positive (RPR, HIV/Syphilis dual) | 2895 | 29 (1.0) |

|

| ||

| In the last 6 months: | ||

| Exchange sex for money or favors | 2937 | 51 (1.7) |

| Diagnosed or treated for an STI | 2937 | 70 (2.4) |

| Forced to have sex against will | 2936 | 145 (4.9) |

| Experience intimate partner violence 1 | 2932 | 230 (7.8) |

| Shared needles during drug use | 2936 | 7 (0.2) |

| Used PEP >2 times | 2934 | 8 (0.3) |

|

| ||

| High HIV risk score 2 | 2949 | 1075 (36.5) |

|

| ||

| Psychosocial characteristics | ||

|

| ||

| Heard of PrEP before | 2922 | 1438 (49.2) |

|

| ||

| Know someone on PrEP | 2932 | 205 (7.0) |

|

| ||

| High perceived HIV risk 3 | 2928 | 250 (8.5) |

|

| ||

| High self-efficacy to take daily medication 4 | 2811 | 1966 (69.9) |

STI=sexually transmitted infection

HITS score ≥ 10

HIV risk score ≥6 (translating to HIV incidence 7.3 per 100 person-years) 31

Self-perceived HIV risk assessed by asking “What is your gut feeling about how likely you are to get infected with HIV?”, with possible responses of “extremely likely”, “very likely”, “somewhat likely”, “very unlikely”, “extremely unlikely”. (High self-perceived HIV risk: Extremely likely/Very likely = “Yes”, Somewhat likely/very unlikely/extremely unlikely = “No”).

Self-efficacy to take a daily oral medication assessed by asking participants to rank on a 0–10 scale (0=Cannot do it at all, 10=Completely certain can do it) their response to the question: “How confident are you that you can integrate a daily medication into your daily routine? (High self-efficacy to take daily medication: >=5)

PrEP initiation

Overall, 14% (95% CI 13%–15%) of women (n=405) enrolled during pregnancy initiated PrEP use. In multivariable analyses, pregnant women were more likely to initiate PrEP if they had characteristics associated with HIV acquisition, including having >2 lifetime sexual partners, having a syphilis diagnosis during pregnancy, being forced to have sex in the last 6 months, and experiencing IPV (p<0.05, Table 2). Pregnant women were also more likely to initiate PrEP if they had higher education, had a partner known to be living within HIV or of unknown HIV status, knew someone taking PrEP, and had high perceived risk of HIV acquisition (p<0.05). Frequency of PrEP initiation was 4.7-fold higher among women who had high self-efficacy for daily pill taking compared to low self-efficacy (adjusted risk ratio[aRR]=4.67, 95% CI 2.97–7.36, p<0.001) and 2.6-fold higher among women with high HIV risk scores compare to lower risk scores (aRR=2.63, 95% CI 1.88–3.67, p<0.001). Women who were primigravida were less likely to initiate PrEP during pregnancy than women who had prior pregnancies (aRR=0.70, 95% 0.58–0.85, p<0.001). Among women who were offered HIV self-tests for male partners (n=1461), accepting HIVST for at-home couples or partner testing was not associated with PrEP initiation (p=0.775).

Table 2.

Correlates of PrEP initiation during pregnancy among women offered PrEP between 14–32 weeks gestation (n=2949)

| n (%) |

Univariate Poisson models

|

Multivariate Poisson models

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N |

Ever initiated PrEP During Pregnancy

|

Risk Ratio (95% CI) | p-value 1 | Adj Risk Ratio (95% CI) | p-value 1 | ||

| Demographic characteristics | No (N=2544) | Yes (n=405) | |||||

|

| |||||||

| Study arm | 2949 | ||||||

| Universal PrEP offer | 1488 | 1270 (49.9) | 218 (53.8) | 1.14 (0.77–1.69) | 0.498 | ||

| Targeted PrEP offer | 1461 | 1274 (50.1) | 187 (46.2) | ref | |||

|

| |||||||

| Age category (years) | 2948 | ||||||

| <24 | 1392 | 1229 (48.3) | 163 (40.3) | 0.75 (0.64–0.88) | <0.001 | 1.08 (0.92–1.27) | 0.3474 |

| ≥24 | 1556 | 1314 (51.7) | 242 (59.8) | ref | ref | ||

|

| |||||||

| Currently married | 2914 | ||||||

| Yes | 2527 | 2166 (86.2) | 361 (90.3) | 1.42 (0.95–2.12) | 0.088 | ||

| No | 387 | 348 (13.8) | 39 (9.8) | ref | |||

|

| |||||||

| Education (years) | 2886 | ||||||

| <12 | 1043 | 1557 (62.5) | 286 (72.8) | 1.51 (1.21–1.89) | <0.001 | 1.30 (1.05–1.61) | 0.015 5 |

| ≥12 | 1843 | 936 (37.6) | 107 (27.2) | ref | ref | ||

|

| |||||||

| Regular employment | 2904 | ||||||

| Yes | 418 | 364 (14.5) | 54 (13.6) | 0.94 (0.74–1.18) | 0.583 | ||

| No | 2486 | 2143 (85.5) | 343 (86.4) | ref | |||

|

| |||||||

| 2+ people per room | 2917 | ||||||

| Yes | 1428 | 1198 (47.6) | 230 (57.5) | 1.41 (1.14–1.74) | 0.001 | 1.18 (0.97–1.45) | 0.0996 |

| No | 1489 | 1319 (52.4) | 170 (42.5) | ref | ref | ||

|

| |||||||

| Primigravida | 2934 | ||||||

| Yes | 673 | 620 (24.5) | 53 (13.1) | 0.51 (0.40–0.64) | <0.001 | 0.70 (0.58–0.85) | <0.001 7 |

| No | 2261 | 1910 (75.5) | 351 (86.9) | ref | ref | ||

|

| |||||||

| Risk assessment chacteristics | |||||||

| No. of lifetime sexual partners >2 | 2939 | ||||||

| Yes | 1453 | 1215 (47.9) | 238 (59.1) | 1.48 (1.26–1.72) | <0.001 | 1.24 (1.06–1.45) | 0.008 6 |

| No | 1486 | 1321 (52.1) | 165 (40.9) | ref | ref | ||

|

| |||||||

| HIV status of primary sexual partner(s) among women with partners | 2908 | ||||||

| Positive | 126 | 45 (1.8) | 81 (20.2) | 7.28 (4.77–11.12) | <0.001 | 6.37 (4.18–9.69) | <0.001 8 |

| Negative | 1880 | 1714 (68.4) | 166 (41.3) | ref | ref | ||

| Unknown | 902 | 747 (29.8) | 155 (38.6) | 1.95 (1.42–2.68) | <0.001 | 1.87 (1.37–2.54) | <0.001 8 |

|

| |||||||

| Partner on ART if HIV-positive | 120 | ||||||

| Yes | 116 | 41 (97.6) | 75 (96.2) | 0.86 (0.45–1.65) | 0.654 | ||

| No | 4 | 1 (2.4) | 3 (3.9) | ref | |||

|

| |||||||

| Syphilis results (RPR, HIV/Syphilis dual) | 2895 | ||||||

| Positive | 29 | 19 (0.8) | 10 (2.5) | 2.55 (1.67–3.88) | <0.001 | 1.84 (1.24–2.75) | 0.003 6 |

| Negative | 2866 | 2478 (99.2) | 388 (97.5) | ref | ref | ||

|

| |||||||

| Forced sex in the last 6 months: | 2936 | ||||||

| Yes | 145 | 106 (4.2) | 39 (9.7) | 2.07 (1.35–3.17) | 0.001 | 1.59 (1.10–2.29) | 0.014 6 |

| No | 2791 | 2428 (95.8) | 363 (90.3) | ref | ref | ||

|

| |||||||

| High HIV risk score 9 | 2949 | ||||||

| Yes | 1075 | 826 (32.5) | 249 (61.5) | 2.78 (1.95–3.96) | <0.001 | 2.63 (1.88–3.67) | <0.001 8 |

| No | 1874 | 1718 (67.5) | 156 (38.5) | ref | ref | ||

|

| |||||||

| HITS score ≥ 10 | 2932 | ||||||

| Yes | 230 | 167 (6.6) | 63 (15.6) | 2.17 (1.67–2.83) | <0.001 | 1.65 (1.25–2.17) | <0.001 6 |

| No | 2702 | 2361 (93.4) | 341 (84.4) | ref | ref | ||

|

| |||||||

| Psychosocial factors | |||||||

| Heard of PrEP before | 2922 | ||||||

| Yes | 1438 | 1227 (48.7) | 211 (52.5) | 1.14 (0.96–1.35) | 0.136 | ||

| No | 1484 | 1293 (51.3) | 191 (47.5) | ref | |||

|

| |||||||

| Know someone on PrEP | 2932 | ||||||

| Yes | 205 | 167 (6.6) | 38 (9.4) | 1.38 (1.06–1.80) | 0.018 | 1.49 (1.15–1.94) | 0.002 6 |

| No | 2727 | 2361 (93.4) | 366 (90.6) | ref | ref | ||

|

| |||||||

| High perceived HIV risk 2 | 2928 | ||||||

| Yes | 250 | 158 (6.3) | 92 (22.9) | 3.18 (2.21–4.57) | <0.001 | 2.01 (1.49–2.73) | <0.001 6 |

| No | 2678 | 2368 (93.8) | 310 (77.1) | ref | ref | ||

|

| |||||||

| High self-efficacy to take daily pill3 | 2811 | ||||||

| Yes | 1966 | 1612 (66.4) | 354 (92.7) | 5.43 (3.49–8.47) | <0.001 | 4.67 (2.97–7.36) | <0.001 6 |

| No | 845 | 817 (33.6) | 28 (7.3) | ref | ref | ||

|

| |||||||

| HIV self-test outcomes | |||||||

| Ever accepted HIV self-tests during pregnancy | 1461 | ||||||

| Yes | 993 | 870 (68.3) | 123 (65.8) | 0.91 (0.46–1.78) | 0.775 | ||

| No | 468 | 404 (31.7) | 64 (34.2) | ref | |||

|

| |||||||

| Partner ever used HIV self-tests if accepted during pregnancy | 1273 | ||||||

| Yes | 774 | 684 (61.6) | 90 (55.2) | 0.79 (0.41–1.55) | 0.499 | ||

| No | 499 | 426 (38.4) | 73 (44.8) | ref | |||

Poisson regression clustered on site, relative risk of initiated PrEP during pregnancy

Self-perceived HIV risk assessed by asking “What is your gut feeling about how likely you are to get infected with HIV?”, with possible responses of “extremely likely”, “very likely”, “somewhat likely”, “very unlikely”, “extremely unlikely”. (High self-perceived HIV risk: Extremely likely/Very likely = “Yes”, Somewhat likely/very unlikely/extremely unlikely = “No”).

Self-efficacy to take a daily oral medication assessed by asking participants to rank on a 0–10 scale (0=Cannot do it at all, 10=Completely certain can do it) their response to the question: “How confident are you that you can integrate a daily medication into your daily routine? (High self-efficacy to take daily medication: >=5)

Adjusted for primigravida (yes/no), education (<12 vs. >=12 years), and partner HIV status

Adjusted for age (continuous), primigravida (yes/no), and partner HIV status

Adjusted for age (continuous), primigravida (yes/no), education (<12 vs. >=12 years), and partner HIV status

Adjusted for age (continuous), education (<12 vs. >=12 years), and partner HIV status

Adjusted for age (continuous), primigravida (yes/no), and education (<12 vs. >=12 years)

HIV risk score ≥6 (translating to HIV incidence 7.3 per 100 person-years) 31

PrEP persistence

Overall, 363 women who initiated PrEP in pregnancy either persisted with PrEP use through 9-months postpartum or stopped use without restarting; 42 women restarted PrEP after stopping and were excluded from the persistence analysis. There were no appreciable differences between participants included in the subset and overall PrEP initiators (Supplemental Material). At 9-months postpartum, 58% (95% CI 53%–64%) had persisted with PrEP use and 54% (95% CI 47%–61%) of those who persisted reported not missing any PrEP pills in the last 30 days. Among women with information on reasons for PrEP discontinuation (n=66), the most frequent reasons for discontinuation included traveling (24%), change in location of residence (20%), and feeling healthy and not at-risk for HIV (18%).

Participants with partners known to be living with HIV at enrollment were more likely to persist with PrEP use through 9-months postpartum compared to participants with partners who were presumed to be HIV-negative (80% vs. 53%, aRR=1.34, 95% CI 1.14–1.57, p<0.001); there was no significant difference between women with partners presumed to be HIV-negative and those of unknown HIV status. PrEP persistence at 9-months postpartum was also associated with having a syphilis diagnosis in pregnancy (aRR=1.40, 95% CI:1.12–1.76, p=0.003). Compared to participants ≥24 years, those <24 years were less likely to persist with PrEP use at 9-months (aRR=0.72, 95% CI 0.57–0.90, p=0.005). Women who were primigravida at PrEP initiation were also less likely to persist with PrEP use (aRR=0.62, 95% CI 0.43–0.91, p=0.013) as were women with a partner known to be living with HIV on ART (p=0.001); only 3 women with had a partner living with HIV not on ART. There was no association between PrEP persistence at 9-months postpartum and other demographic, behavioral, or pregnancy-related characteristics or partner HIV self-test use (Table 3).

Table 3.

Correlates of PrEP persistence at 9-months postpartum among women who initiated PrEP during pregnancy (n=363)

| n (%) |

Univariate Poisson models

|

Multivariate Poisson models

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N |

Persisted with PrEP use at 9-months postpartum

|

Risk Ratio (95% CI) | p-value 1 | Adj Risk Ratio (95% CI) | p-value 1 | ||

| Demographic characteristics | No (N=151) | Yes (n=212) | |||||

|

| |||||||

| Study arm | 363 | ||||||

| Universal PrEP offer | 193 | 83 (55.0) | 110 (51.9) | 0.95 (0.73–1.24) | 0.702 | ||

| Targeted PrEP offer | 170 | 68 (45.0) | 102 (48.1) | ref | |||

|

| |||||||

| Age category (years) | 363 | ||||||

| <24 | 149 | 85 (56.3) | 64 (30.2) | 0.62 (0.50–0.77) | <0.001 | 0.72 (0.57–0.90) | 0.005 4 |

| ≥24 | 214 | 66 (43.7) | 148 (69.8) | ref | ref | ||

|

| |||||||

| Currently married | 359 | ||||||

| Yes | 324 | 128 (86.5) | 196 (92.9) | 1.41 (0.93–2.14) | 0.106 | ||

| No | 35 | 20 (13.5) | 15 (7.1) | ref | |||

|

| |||||||

| Education (years) | 353 | ||||||

| <12 | 254 | 88 (60.7) | 166 (79.8) | 1.54 (1.18–2.02) | 0.002 | 1.40 (1.11–1.77) | 0.004 5 |

| ≥12 | 99 | 57 (39.2) | 42 (20.2) | ref | ref | ||

|

| |||||||

| Regular employment | 357 | ||||||

| Yes | 51 | 20 (13.5) | 31 (14.8) | 1.04 (0.88–1.24) | 0.618 | ||

| No | 306 | 128 (86.5) | 178 (85.2) | ref | |||

|

| |||||||

| 2+ people per room | 359 | ||||||

| Yes | 204 | 79 (53.0) | 125 (59.5) | 1.12 (0.92–1.36) | 0.264 | ||

| No | 155 | 70 (47.0) | 85 (40.5) | ref | |||

|

| |||||||

| Primigravida | 362 | ||||||

| Yes | 312 | 117 (77.5) | 195 (92.4) | 0.51 (0.34–0.76) | 0.001 | 0.62 (0.43–0.91) | 0.013 6 |

| No | 50 | 34 (22.5) | 16 (7.6) | ref | ref | ||

|

| |||||||

| Risk assessment chacteristics | |||||||

| No. of lifetime sexual partners >2 | 361 | ||||||

| Yes | 211 | 86 (57.3) | 125 (59.2) | 1.03 (0.87–1.23) | 0.709 | ||

| No | 150 | 64 (42.7) | 86 (40.8) | ref | |||

|

| |||||||

| HIV status of primary sexual partner(s) among women with partners | 360 | ||||||

| Positive | 71 | 14 (9.3) | 57 (27.3) | 1.53 (1.32–1.77) | <0.001 | 1.34 (1.14–1.57) | <0.001 7 |

| Negative | 152 | 72 (47.7) | 80 (38.3) | ref | - | ref | - |

| Unknown | 137 | 65 (43.1) | 72 (34.5) | 1.00 (0.82–1.22) | 0.989 | 1.04 (0.88–1.23) | 0.6577 |

|

| |||||||

| Partner on ART if HIV-positive | 69 | ||||||

| Yes | 66 | 13 (100.0) | 53 (94.6) | 0.80 (0.71–0.91) | 0.001 | ||

| No | 3 | 0 (0.0) | 3 (5.4) | ref | |||

|

| |||||||

| Syphilis results (RPR, HIV/Syphilis dual) | 356 | ||||||

| Positive | 8 | 1 (0.7) | 7 (3.4) | 1.53 (1.14–2.04) | 0.005 | 1.40 (1.12–1.76) | 0.003 8 |

| Negative | 348 | 148 (99.3) | 200 (96.6) | ref | ref | ||

|

| |||||||

| Forced sex in the last 6 months: | 360 | ||||||

| Yes | 34 | 16 (10.7) | 18 (8.6) | 0.90 (0.63–1.28) | 0.554 | ||

| No | 326 | 134 (89.3) | 192 (91.4) | ref | |||

|

| |||||||

| High HIV risk score 9 | 363 | ||||||

| Yes | 221 | 86 (57.0) | 135 (63.7) | 1.13 (0.95–1.34) | 0.178 | ||

| No | 142 | 65 (43.1) | 77 (36.3) | ref | |||

|

| |||||||

| HITS score ≥ 10 | 362 | ||||||

| Yes | 57 | 25 (16.6) | 32 (15.2) | 0.96 (0.80–1.14) | 0.623 | ||

| No | 305 | 126 (83.4) | 179 (84.8) | ref | |||

|

| |||||||

| Psychosocial factors | |||||||

| Heard of PrEP before | 361 | ||||||

| Yes | 187 | 72 (48.0) | 115 (54.5) | 1.15 (0.95–1.31) | 0.193 | ||

| No | 174 | 78 (52.0) | 96 (45.5) | ref | |||

|

| |||||||

| Know someone on PrEP | 362 | ||||||

| Yes | 36 | 15 (10.0) | 21 (9.9) | 1.00 (0.66–1.49) | 0.983 | ||

| No | 326 | 135 (90.0) | 191 (90.1) | ref | |||

|

| |||||||

| High perceived HIV risk 2 | 360 | ||||||

| Yes | 82 | 28 (18.7) | 54 (25.7) | 1.17 (0.92–1.49) | 0.192 | ||

| No | 278 | 122 (81.3) | 156 (74.3) | ref | |||

|

| |||||||

| High self-efficacy to take daily pill3 | 343 | ||||||

| Yes | 315 | 127 (89.4) | 188 (93.5) | 1.29 (0.91–1.82) | 0.158 | ||

| No | 28 | 15 (10.6) | 13 (6.5) | ref | |||

|

| |||||||

| PrEP and HIV self-test outcomes | |||||||

| Ever experienced PrEP side effects | 350 | ||||||

| Yes | 118 | 51 (37.0) | 67 (31.6) | 0.91 (0.72–1.15) | 0.425 | ||

| No | 232 | 87 (63.0) | 145 (68.4) | ref | |||

| Ever accepted HIV self-tests | 170 | ||||||

| Yes | 113 | 51 (75.0) | 62 (60.8) | 0.78 (0.60–1.02) | 0.071 | ||

| No | 57 | 17 (25.0) | 40 (39.2) | ref | |||

|

| |||||||

| Partner ever used HIV self-tests | 150 | ||||||

| Yes | 84 | 38 (64.4) | 46 (50.6) | 0.80 (0.65–1.00) | 0.046 | 1.19 (0.96–1.48) | 0.1118 |

| No | 66 | 21 (35.6) | 45 (49.5) | ref | ref | ||

Poisson regression clustered on site, relative risk of persisted PrEP

Self-perceived HIV risk assessed by asking “What is your gut feeling about how likely you are to get infected with HIV?”, with possible responses of “extremely likely”, “very likely”, “somewhat likely”, “very unlikely”, “extremely unlikely”. (High self-perceived HIV risk: Extremely likely/Very likely = “Yes”, Somewhat likely/very unlikely/extremely unlikely = “No”).

Self-efficacy to take a daily oral medication assessed by asking participants to rank on a 0–10 scale (0=Cannot do it at all, 10=Completely certain can do it) their response to the question: “How confident are you that you can integrate a daily medication into your daily routine? (High self-efficacy to take daily medication: >=5)

Adjusted for primigravida (yes/no), education (<12 vs. >=12 years), and partner HIV status

Adjusted for age (continuous), primigravida (yes/no), and partner HIV status

Adjusted for age (continuous), education (<12 vs. >=12 years), and partner HIV status

Adjusted for age (continuous), primigravida (yes/no), and education (<12 vs. >=12 years)

Adjusted for age (continuous), primigravida (yes/no), education (<12 vs. >=12 years) and partner HIV status

HIV risk score ≥6 (translating to HIV incidence 7.3 per 100 person-years) 31

Among women who initiated PrEP with information on side effects (n=350), 34% experienced at least one side effect and the most frequent side effects reported were dizziness (14%), nausea (13%), and vomiting (11%); frequency of having any side effects of dizziness, nausea, or vomiting was more common in pregnancy than postpartum (28% vs. 5%, p<0.001). Experiencing side effects was not associated with PrEP persistence (p=0.425).

PrEP adherence

Overall, 198 participants (49% of PrEP initiators) were randomly selected for inclusion in the PrEP adherence analysis and were similar to overall PrEP initiators in PrIMA (Supplemental Material). Each participant contributed a median of 3 visits to the analysis (IQR 2–4). Among visits from the subset (n=454), 94% (427/454, 95% CI 91%–96%) of women reported any PrEP use in the last 30 days. Among DBS from these visits (n=427), 50% (95% CI 45%–55%) had quantifiable TFV-DP of which 26% (95% CI 20%–32%) had TFV-DP concentrations indicating <2 doses/week, 65% (95% CI 58%–71%) 2–6 doses/week, and 9% (95% CI 6%–14%) 7 doses/week. Having a partner known to be living with HIV was associated with a 2-fold higher likelihood of any quantifiable TFV-DP compared to having partners who were presumed HIV-negative (aRR=2.03, 95% CI 1.33–3.09, p<0.001). Quantifiable TFV-DP was also twice as likely during pregnancy compared to postpartum (53% vs. 27%, aRR=1.87, 95% CI 1.38–2.53, p<0.001). Among postpartum visits, 33% had quantifiable TFV-DP at 6 weeks (n=114), 23% at 6 months (n=65), and 20% at 9 months (n=65). Self-reporting no missed pills in the last 30 days was associated with higher likelihood of TFV-DP quantification (aRR=1.48, 95% CI 1.03–2.12, p=0.035), though only 122/254 (48%) of DBS from visits where participants reported no missed pills had any quantifiable TFV-DP.

A higher likelihood of quantifiable TFV-DP was also associated with high perceived HIV risk (aRR=1.34, 95% CI 1.02–1.77, p=0.033) and trended towards an association with experiencing IPV (aRR=1.35, 95% CI 0.99–1.83, p=0.059). Participants who experienced side effects were less likely to have quantifiable TFV-DP aRR=0.68, 95% CI 0.47–0.99, p=0.042). There was no association between quantifiable TFV-DP and other demographic, behavioral, or pregnancy-related characteristics or partner HIV self-test use (Table 4).

Table 4.

Correlates of any quantifiable TFV-DP exposure at follow-up visits among women who initiated PrEP during pregnancy (n=524)

| n (%) | Univariate Poisson models |

Multivariate Poisson models |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N |

Quantifiable TFV-DP exposure

|

Risk Ratio (95% CI) | p-value 1 | Adj Risk Ratio (95% CI) | p-value 1 | ||

| Demographic characteristics | No (N=311) | Yes (n=213) | |||||

|

| |||||||

| Study arm | 524 | ||||||

| Universal PrEP offer | 282 | 181 (58.2) | 101 (47.4) | 0.77 (0.46–1.30) | 0.334 | ||

| Targeted PrEP offer | 242 | 130 (41.8) | 112 (52.6) | ref | |||

|

| |||||||

| Age category (years) | 524 | ||||||

| <24 | 189 | 127 (40.8) | 62 (29.1) | 0.73 (0.57–0.93) | 0.010 | 0.82 (0.62–1.07) | 0.1464 |

| ≥24 | 335 | 184 (59.2) | 151 (70.9) | ref | ref | ||

|

| |||||||

| Currently married | 522 | ||||||

| Yes | 478 | 281 (90.9) | 197 (92.5) | 1.13 (0.59–2.19) | 0.709 | ||

| No | 44 | 28 (9.1) | 16 (7.5) | ref | |||

|

| |||||||

| Education (years) | 513 | ||||||

| <12 | 379 | 213 (70.5) | 166 (78.7) | 1.30 (0.92–1.84) | 0.133 | ||

| ≥12 | 134 | 89 (29.5) | 45 (21.3) | ref | |||

|

| |||||||

| Regular employment | 522 | ||||||

| Yes | 83 | 53 (17.2) | 30 (14.1) | 0.87 (0.57–1.32) | 0.508 | ||

| No | 439 | 256 (82.9) | 183 (85.9) | ref | |||

|

| |||||||

| 2+ people per room | 522 | ||||||

| Yes | 313 | 179 (57.9) | 134 (62.9) | 1.13 (0.87–1.47) | 0.352 | ||

| No | 209 | 130 (42.1) | 79 (37.1) | ref | |||

|

| |||||||

| Primigravida | 524 | ||||||

| Yes | 69 | 53 (17.0) | 16 (7.5) | 0.54 (0.33–0.87) | 0.013 | 0.77 (0.46–1.32) | 0.3435 |

| No | 455 | 258 (83.0) | 197 (92.5) | ref | ref | ||

|

| |||||||

| Visit timing | 524 | ||||||

| Pregnant | 280 | 133 (42.8) | 147 (69.0) | ||||

| Postpartum | 244 | 178 (57.2) | 66 (31.0) | 1.94 (1.40–2.69) | <0.001 | 1.87 (1.38–2.53) | <0.001 7 |

|

| |||||||

| Risk assessment chacteristics | |||||||

| No. of lifetime sexual partners >2 | 524 | ||||||

| Yes | 313 | 187 (60.1) | 126 (59.2) | 0.98 (0.80–1.19) | 0.813 | ||

| No | 211 | 124 (39.9) | 87 (40.9) | ref | |||

|

| |||||||

| HIV status of primary sexual partner(s) among women with partners | 519 | ||||||

| Positive | 104 | 35 (11.3) | 69 (33.2) | 2.25 (1.49–3.40) | <0.001 | 2.03 (1.33–3.09) | 0.001 6 |

| Negative | 210 | 148 (47.6) | 62 (29.8) | ref | ref | ||

| Unknown | 205 | 128 (41.2) | 77 (37.0) | 1.27 (0.84–1.92) | 0.252 | 1.30 (0.88–1.91) | 0.1916 |

|

| |||||||

| Partner on ART if HIV-positive | 104 | ||||||

| Yes | 100 | 35 (100.0) | 65 (94.2) | 0.65 (0.51–0.83) | 0.001 | ||

| No | 4 | 0 (0.0) | 4 (5.8) | ref | |||

| Syphilis results (RPR, HIV/Syphilis dual) | 524 | ||||||

| Positive | 13 | 8 (2.6) | 5 (2.4) | 0.94 (0.57–1.56) | 0.824 | ||

| Negative | 511 | 303 (97.4) | 208 (97.7) | ref | |||

|

| |||||||

| Forced sex in the last 6 months: | 524 | ||||||

| Yes | 35 | 21 (6.8) | 14 (6.6) | 0.98 (0.54–1.81) | 0.956 | ||

| No | 489 | 290 (93.3) | 199 (93.4) | ref | |||

|

| |||||||

| High HIV risk score 9 | 524 | ||||||

| Yes | 330 | 177 (56.9) | 153 (71.8) | 1.50 (0.98–2.29) | 0.060 | ||

| No | 194 | 134 (43.1) | 60 (28.2) | ref | |||

|

| |||||||

| HITS score ≥ 10 | 524 | ||||||

| Yes | 91 | 41 (13.2) | 50 (23.5) | 1.46 (1.06–2.01) | 0.020 | 1.35 (0.99–1.83) | 0.0597 |

| No | 433 | 270 (86.8) | 163 (76.5) | ref | ref | ||

|

| |||||||

| Psychosocial factors | |||||||

| Heard of PrEP before | 524 | ||||||

| Yes | 240 | 125 (40.2) | 115 (54.0) | 1.39 (1.06–1.82) | 0.016 | 1.26 (0.92–1.72) | 0.1567 |

| No | 284 | 186 (59.8) | 98 (46.0) | ref | ref | ||

|

| |||||||

| Know someone on PrEP | 524 | ||||||

| Yes | 58 | 28 (9.0) | 30 (14.1) | 1.31 (0.92–1.89) | 0.137 | ||

| No | 466 | 283 (91.0) | 183 (85.9) | ref | |||

|

| |||||||

| High perceived HIV risk 2 | 520 | ||||||

| Yes | 125 | 58 (18.7) | 67 (31.9) | 1.48 (1.06–2.07) | 0.022 | 1.34 (1.02–1.77) | 0.033 7 |

| No | 395 | 252 (81.3) | 143 (68.1) | ref | ref | ||

|

| |||||||

| High self-efficacy to take daily pill3 | 504 | ||||||

| Yes | 480 | 285 (96.3) | 195 (93.4) | 0.75 (0.40–1.41_ | 0.371 | ||

| No | 24 | 11 (3.7) | 13 (6.3) | ref | |||

|

| |||||||

| PrEP and HIV self-test outcomes | |||||||

| Ever experienced PrEP side effects | 511 | ||||||

| Yes | 174 | 122 (40.7) | 52 (24.6) | 0.63 (0.42–0.95) | 0.028 | 0.68 (0.47–0.99) | 0.042 7 |

| No | 337 | 178 (59.3) | 159 (75.4) | ref | ref | ||

| Ever accepted HIV self-tests | 242 | ||||||

| Yes | 176 | 107 (82.3) | 69 (61.6) | 0.60 (0.48–0.76) | <0.001 | 1.13 (0.78–1.64) | 0.5237 |

| No | 66 | 23 (17.7) | 43 (38.4) | ref | ref | ||

|

| |||||||

| Partner ever used HIV self-tests | 204 | ||||||

| Yes | 129 | 87 (76.3) | 42 (46.7) | 0.51 (0.35–0.75) | 0.001 | 0.80 (0.54–1.17) | 0.2507 |

| No | 75 | 27 (23.7) | 48 (53.3) | ref | ref | ||

| No missed PrEP pill last 30 days 8 | 524 | ||||||

| Yes | 254 | 122 (39.2) | 132 (62.0) | 1.73 (1.33–2.25) | <0.001 | 1.48 (1.03–2.12) | 0.035 7 |

| No | 270 | 189 (60.8) | 81 (38.0) | ref | ref | ||

Poisson regression clustered on site, relative risk of persisted PrEP

Self-perceived HIV risk assessed by asking “What is your gut feeling about how likely you are to get infected with HIV?”, with possible responses of “extremely likely”, “very likely”, “somewhat likely”, “very unlikely”, “extremely unlikely”. (High self-perceived HIV risk: Extremely likely/Very likely = “Yes”, Somewhat likely/very unlikely/extremely unlikely = “No”).

Self-efficacy to take a daily oral medication assessed by asking participants to rank on a 0–10 scale (0=Cannot do it at all, 10=Completely certain can do it) their response to the question: “How confident are you that you can integrate a daily medication into your daily routine? (High self-efficacy to take daily medication: >=5)

Adjusted for primigravida (yes/no), education (<12 vs. >=12 years), and partner HIV status

Adjusted for age (continuous), education (<12 vs. >=12 years), and partner HIV status

Adjusted for age (continuous), primigravida (yes/no), and education (<12 vs. >=12 years)

Adjusted for age (continuous), primigravida (yes/no), education (<12 vs. >=12 years) and partner HIV status

Based on self-report

HIV risk score ≥6 (translating to HIV incidence 7.3 per 100 person-years) 31

Among participants with more than one visit randomly selected for the PrEP adherence analysis (n=156, median of 3 visits), 25% had quantifiable TFV-DP at all visits. Participants with partners known to be living with HIV were 5.5 times more likely to have quantifiable TFV-DP at all visits compared to women with partners who were perceived to be HIV-negative or of unknown HIV status (RR=5.5, 95% CI 2.7–11.01, p<0.001); power was limited to detect associations with other correlates (data not shown).

Exploratory analyses

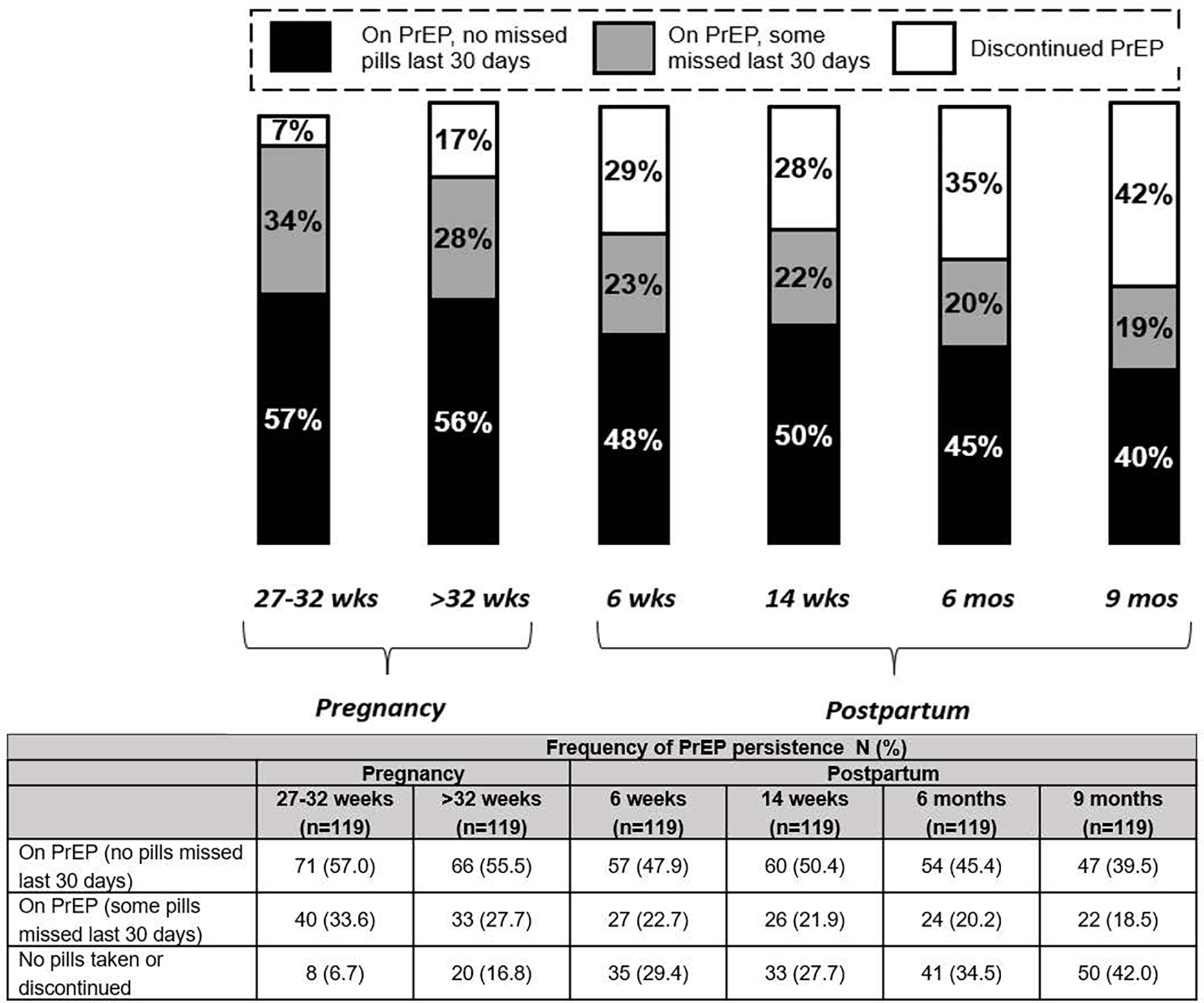

Overall, 119 women had complete self-reported information on PrEP pill-taking and attended all follow-up visits after PrEP initiation. Among this subset, 40% of participants who continued PrEP use through 9 months postpartum reported missing no PrEP pills in the last 30 days; having this trajectory of PrEP use was associated with syphilis diagnosis in pregnancy and having a partner known to be living with HIV (p<0.05; data not shown). Frequency of PrEP continuation and self-reporting no missed PrEP pills decreased from pregnancy through 9-months postpartum (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Frequency of PrEP persistence over time among participants who initiated PrEP during pregnancy and had complete information on PrEP use at all follow-up visits (n=119).

1 n=48 participants initiated PrEP at 14–26 weeks gestation and n=71 participants initiated PrEP 27–32 weeks gestation; all attended follow-up visits at 27–32 weeks and >32 weeks gestation

2 Excludes all visits prior to PrEP initiation

3 If a participant had >1 visit during the pregnancy windows (14–26 weeks, 27–32 weeks, or >32 weeks), the visit with their first indication of PrEP use was included.

4 On PrEP defined as responding “yes” to the questionnaire item, “Are you currently taking PrEP?”

DISCUSSION

In this large prospective evaluation among Kenyan women in a high HIV prevalence area who were offered PrEP in pregnancy, over half of those who initiated PrEP continued use through 9-months postpartum, and a substantial proportion of PrEP users had quantifiable TFV-DP levels, indicating at least some PrEP pill-taking. PrEP continuation and adherence waned throughout the postpartum period, though over half of all PrEP initiators continued use through 9-months postpartum. In a recent meta-analysis, pooled PrEP discontinuation in the 6 months following PrEP initiation was 43.3% (95% CI 27.5–60.6) among cisgender women and 47.5% (95% CI 29.4–66.4) among studies from sub-Saharan Africa38, similar to the rates of discontinuation (42%) we found at 9 months postpartum after approximately 12 months of PrEP use. Our findings demonstrate that women desire PrEP and persist with PrEP during the peripartum period and illustrate need for further interventions to support PrEP adherence during this critical period. Our evaluation contributes to the very few data on the PrEP continuum of care among pregnant and postpartum women.

Our findings support that knowledge of partners’ HIV status is important for PrEP use and that women with partners known to be living with HIV are highly motivated to use daily oral PrEP, similar to studies among pregnant PrEP users in South Africa.39 Dispensing HIV self-tests to pregnant women attending antenatal care to give to their male partners is scaling up in East and Southern Africa to increase testing coverage among men.28,40–43 Few studies have evaluated HIV self-test distribution with PrEP,44 though existing data suggest acceptance of self-tests is not associated with PrEP uptake within family planning clinics.45 Increasing awareness of male partner HIV status could be a powerful strategy for promoting PrEP use among women most likely to benefit.

Pregnant women with characteristics associated with HIV acquisition frequently initiated PrEP in our study, similar to findings of studies among pregnant women in South Africa10,46 and our team’s prior work among Kenyan women.13 One-third of participants who initiated PrEP experienced side effects and this was associated with lower PrEP adherence, similar to previous studies.13 In populations other than pregnant women, less than 10% of PrEP users experience any side effects (as low as <2% in some studies).47 Generally, PrEP side effects occur during the “start-up” period and go away within 2 weeks,47 though side effects may be altered or exacerbated in pregnancy. We also found that primigravida women and those <24 years were less likely to persist with PrEP use. Tailored support for women who initiate PrEP during pregnancy that includes managing side effects and addresses concerns for first-time and young mothers could help sustain adherence.11,20,48 Some factors (IPV, self-efficacy, knowing someone on PrEP, etc.) associated with initiating PrEP were not associated with PrEP persistence, perhaps because the initiators are a subset with these selected characteristics and thus, there is less heterogeneity to discern differences in these characteristics among those who persist.

To date, few PrEP studies among pregnant and postpartum women have incorporated objective markers of PrEP adherence. A recent study that followed South African women who initiated PrEP in pregnancy until 12-months postpartum found that 72% of all DBS samples had TFV-DP concentrations corresponding with <2 doses/week46 and frequency of any quantifiable TFV-DP was higher in pregnancy than postpartum.39 We similarly found high frequency of TFV-DP concentrations corresponding with <2 doses/week (64% overall) and lower adherence levels postpartum than pregnancy. These data suggest PrEP adherence wanes in the postpartum period, a time critical for HIV prevention as sexual activity resumes and vertical transmission of HIV via breastfeeding poses a risk to infants.49 Interventions that support PrEP adherence postpartum could be especially beneficial and one ongoing study is testing an SMS intervention to promote postpartum PrEP adherence (NCT04472884). Another study is evaluating implementation of injectable long-acting cabotegravir (CAB-LA) within postpartum services in a primarily breastfeeding population in Botswana (NCT05515770). These studies will accrue data on interventions and newer PrEP agents that address adherence challenges postpartum.

Participants in our study were more likely to initiate PrEP and persist with PrEP use following a syphilis diagnosis in pregnancy. Participants with higher perceived HIV risk were also more likely to initiate PrEP, though overall <10% perceived themselves to be at high risk for HIV. Previous studies have shown an imbalanced relationship between perceived versus actual HIV risk among pregnant women, based on solely self-reported sexual behaviors.50,51 Low perceived HIV risk is a common reason for declining PrEP among pregnant women, even when male partner HIV status is unknown.52 Within ANC, syphilis testing could inform HIV risk assessment and perception, and subsequently PrEP decision-making. Several countries, including Kenya, conduct universal antenatal syphilis screening using rapid syphilis testing to accelerate maternal treatment and prevention of newborn complications of syphilis,53,54 though similar efforts to scale up screening of other STIs have not been implemented.55,56 Data suggest that STIs are common among pregnant PrEP users in Kenya and South Africa57–59 and a STIs are facilitator of PrEP initiation. In a recent study, 93% of HIV-negative South African women with an STI diagnosed in pregnancy started taking PrEP.46 Intervention studies that evaluate STI testing as a strategy to enhance PrEP initiation among women in HIV high-burden settings could be useful for informing PrEP decision-making and the burden of STIs in this population.

Our study has limitations. We relied on self-report of PrEP persistence, though we included evaluation of TFV-DP levels as an objective marker of adherence. The study was designed to offer PrEP during pregnancy, and we did not systematically evaluate PrEP uptake in the postpartum period. Less than 15% of PrEP initiators in the parent study initiated PrEP postpartum (n=70) which limits our statistical power to evaluate postpartum PrEP uptake. We relied on self-report for HIV status and self-testing outcomes among male partners, similar to other studies of HIV self-test secondary distribution in Kenya.45,60 We also did not systematically capture information on viral suppression of male partners living with HIV or timing of ART initiation which may influence PrEP discontinuation when PrEP is used as a bridge until viral suppression of the partner living with HIV is achieved.61 We purposively selected a subset who enrolled in the second trimester based on the median gestational age at enrollment among PrIMA participants and to allow for similar follow-up time for longitudinal analyses and therefore cannot evaluate timing of PrEP initiation in pregnancy and PrEP outcomes. We did not detect differences between the subset and overall PrIMA participants though the subset may not be representative of all ANC attendees in this setting. Patterns of stopping and restarting PrEP were also not systematically captured in the parent study, though this accounts for <10% of all PrEP initiators in this study population. Reasons for discontinuing PrEP were also missing for a substantial portion of participants who discontinued. Future studies should examine newer long-acting PrEP products, once available approved for use in pregnancy, to evaluate whether patterns of use are similar with additional PrEP options.

In conclusion, we found that PrEP persistence and adherence waned in the postpartum period among participants who initiated PrEP pregnancy, though overall approximately half of PrEP initiators continued through postpartum. Interventions should prioritize increasing knowledge of partner HIV status, refining risk assessment, potentially with STI testing, and sustaining adherence support systems in the postpartum period.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

GJG, JMB, JK, JH, and JP conceived and designed the study. JK, FA, MM, SW, and BO conducted data collection. JP, LG, JCD, and JS analyzed the data. PA analyzed laboratory specimens. JP and GJS drafted the paper. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript. The authors would like to gratefully thank the study participants and PrIMA staff for their time and contributions. We thank the Kenyan Ministry of Health nationally, the Kisumu County Department of Health, and the facility heads and in-charges for their collaboration with this study.

Funding:

Funding for this project was provided by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease (GJS- R01AI125498) and Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development (GJS- R01HD094630; JP-R01HD100201). JP was additionally supported by NICHD (R01HD108041) and the National Institute of Nursing Research (R01NR019220). The team was supported by the University of Washington’s Center for AIDS Research Behavioral Sciences Core and Biometrics Core (P30AI027757) and the Global Center for the Integrated Health of Women, Adolescents, and Children (Global WACh). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: JMB is an employee of Gilead Sciences, outside of the present work. The remaining authors have no financial conflicts of interest to declare. PLA received personal fees from Gilead, Merck, and ViiV, not related to this work and research/contract work from Gilead Sciences, paid to his institution.

REFERENCES

- 1.Drake AL, Wagner A, Richardson B, John-Stewart G. Incident HIV during pregnancy and postpartum and risk of mother-to-child HIV transmission: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. Feb 2014;11(2):e1001608. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thomson KA, Hughes J, Baeten JM, et al. Increased Risk of Female HIV-1 Acquisition Throughout Pregnancy and Postpartum: A Prospective Per-coital Act Analysis Among Women with HIV-1 Infected Partners. J Infect Dis. Mar 2018;doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiy113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Graybill LA, Kasaro M, Freeborn K, et al. Incident HIV among pregnant and breast-feeding women in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS (London, England). Apr 1 2020;34(5):761–776. doi: 10.1097/qad.0000000000002487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Joseph Davey DL, Nyemba DC, Gomba Y, et al. Prevalence and correlates of sexually transmitted infections in pregnancy in HIV-infected and- uninfected women in Cape Town, South Africa. PloS one. 2019;14(7):e0218349. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0218349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Joseph Davey D, Farley E, Gomba Y, Coates T, Myer L. Sexual risk during pregnancy and postpartum periods among HIV-infected and -uninfected South African women: Implications for primary and secondary HIV prevention interventions. PloS one. 2018;13(3):e0192982. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0192982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Joseph Davey DL, Pintye J, Baeten JM, et al. Emerging evidence from a systematic review of safety of pre-exposure prophylaxis for pregnant and postpartum women: where are we now and where are we heading? Journal of the International AIDS Society. Jan 2020;23(1):e25426. doi: 10.1002/jia2.25426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stalter RM, Pintye J, Mugwanya KK. Safety review of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine pre-exposure prophylaxis for pregnant women at risk of HIV infection. Expert Opin Drug Saf. May 28 2021:1–7. doi: 10.1080/14740338.2021.1931680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Organization WH. WHO Technical brief: Preventing HIV during pregnancy and breastfeeding in the context of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). 2017. CC BY-NC-SA 30 IGO. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mofenson LM, Baggaley RC, Mameletzis I. Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate safety for women and their infants during pregnancy and breastfeeding. AIDS (London, England). Jan 14 2017;31(2):213–232. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joseph Davey DL, Mvududu R, Mashele N, et al. Early pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) discontinuation among pregnant and postpartum women: Implications for maternal PrEP roll out in South Africa. medRxiv. 2021:2021.May.04.21256514. doi: 10.1101/2021.05.04.21256514 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pintye J, Davey DLJ, Wagner AD, et al. Defining gaps in pre-exposure prophylaxis delivery for pregnant and post-partum women in high-burden settings using an implementation science framework. The lancet HIV. Aug 2020;7(8):e582–e592. doi: 10.1016/s2352-3018(20)30102-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bekker L-G, Brown B, Joseph-Davey D, et al. Southern African guidelines on the safe, easy and effective use of pre-exposure prophylaxis: 2020. pre-exposure prophylaxis; HIV; prevention tools; pregnant and breastfeeding women; transgender women. 2020. 2020–12-10 2020;21(1)doi: 10.4102/sajhivmed.v21i1.1152 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kinuthia J, Pintye J, Abuna F, et al. Pre-exposure prophylaxis uptake and early continuation among pregnant and post-partum women within maternal and child health clinics in Kenya: results from an implementation programme. The lancet HIV. Jan 2020;7(1):e38–e48. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(19)30335-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zimba C, Maman S, Rosenberg NE, et al. The landscape for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis during pregnancy and breastfeeding in Malawi and Zambia: A qualitative study. PloS one. 2019;14(10):e0223487. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0223487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kinuthia J, Pintye J, Abuna F, et al. Pre-exposure prophylaxis uptake and early continuation among pregnant and post-partum women within maternal and child health clinics in Kenya: results from an implementation programme. Lancet HIV. Jan 2020;7(1):e38–e48. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(19)30335-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Musinguzi N, Muganzi CD, Boum Y, 2nd, et al. Comparison of subjective and objective adherence measures for preexposure prophylaxis against HIV infection among serodiscordant couples in East Africa. Aids. Apr 24 2016;30(7):1121–9. doi: 10.1097/qad.0000000000001024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marrazzo JM, Ramjee G, Richardson BA, et al. Tenofovir-based preexposure prophylaxis for HIV infection among African women. N Engl J Med. Feb 5 2015;372(6):509–18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1402269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van Damme L, Corneli A, Ahmed K, et al. Preexposure prophylaxis for HIV infection among African women. N Engl J Med. Aug 2 2012;367(5):411–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1202614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davey DLJ, Knight L, Markt-Maloney J, et al. “I had made the decision, and no one was going to stop me” —Facilitators of PrEP adherence during pregnancy and postpartum in Cape Town, South Africa. medRxiv. 2020:2020.November.23.20236729. doi: 10.1101/2020.11.23.20236729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pintye J, O’Malley G, Kinuthia J, et al. Influences on Early Discontinuation and Persistence of Daily Oral PrEP Use Among Kenyan Adolescent Girls and Young Women: A Qualitative Evaluation From a PrEP Implementation Program. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999). 2021/04// 2021;86(4):e83–e89. doi: 10.1097/qai.0000000000002587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pintye J, Beima-Sofie KM, Kimemia G, et al. “I Did Not Want to Give Birth to a Child Who has HIV”: Experiences Using PrEP During Pregnancy Among HIV-Uninfected Kenyan Women in HIV-Serodiscordant Couples. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. Nov 2017;76(3):259–265. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heffron R, Thomson K, Celum C, et al. Fertility Intentions, Pregnancy, and Use of PrEP and ART for Safer Conception Among East African HIV Serodiscordant Couples. AIDS Behav. Sep 2017;doi: 10.1007/s10461-017-1902-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haas AD, Msukwa MT, Egger M, et al. Adherence to Antiretroviral Therapy During and After Pregnancy: Cohort Study on Women Receiving Care in Malawi’s Option B+ Program. Clin Infect Dis. November 01 2016;63(9):1227–1235. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tsegaye R, Etafa W, Wakuma B, Mosisa G, Mulisa D, Tolossa T. The magnitude of adherence to option B plus program and associated factors among women in eastern African countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. Nov 27 2020;20(1):1812. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09903-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pintye J, Escudero J, Kinuthia J, et al. Motivations for early PrEP discontinuation among Kenyan adolescent girls and young women: A qualitative analysis from a PrEP implementation program ( WEPED822). presented at: International AIDS Society (IAS) Conference on HIV Science; 2019; Mexico City, Mexico. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pintye J, Kinuthia J, Abuna F, et al. Frequent detection of tenofovir-diphosphate among young Kenyan women in a real-world PrEP implementation program (Abstract # TUAC0305LB). presented at: International AIDS Society (IAS) Conference on HIV Science; 2019; Mexico City, Mexico. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kinuthia J, Pintye J, Abuna F, Mugwanya K, Lagat H, Onyango D, Bengel E, Dettinger J, Baeten J, John-Stewart G. Pre-exposure prophylaxis uptake and early continuation among pregnant and postpartum women within maternal child health clinics in Kenya: results from an implementation programme. The lancet HIV. 2019;In Press; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dettinger JC, Kinuthia J, Pintye J, et al. PrEP Implementation for Mothers in Antenatal Care (PrIMA): study protocol of a cluster randomised trial. BMJ Open. Mar 2019;9(3):e025122. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.National AIDS and STI Control Programme (NASCOP). Kenya AIDS Indicator Survey 2012: Final Report. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 30.National AIDS and STI Control Programme (NASCOP). Preliminary Kenya Population-based HIV Impact Assessment (KENPHIA) 2018 Report. Nairobi: NASCOP; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pintye J, Drake AL, Kinuthia J, et al. A risk assessment tool for identifying pregnant and postpartum women who may benefit from pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). Clin Infect Dis. Dec 28 2016;doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ministry of Health NASCP. Guidelines on use of Antiretroviral Drugs for Treating and Preventing HIV Infection in Kenya 2016. July 2016. Accessed December 11, 2016. http://emtct-iatt.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Guidelines-on-Use-of-Antiretroviral-Drugs-for-Treating-and-Preventing-HI....pdf

- 33.Sherin KM, Sinacore JM, Li XQ, Zitter RE, Shakil A. HITS: a short domestic violence screening tool for use in a family practice setting. Fam Med. Jul-Aug 1998;30(7):508–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Anderson PL, Liu AY, Castillo-Mancilla JR, et al. Intracellular Tenofovir-Diphosphate and Emtricitabine-Triphosphate in Dried Blood Spots following Directly Observed Therapy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 01 2018;62(1)doi: 10.1128/AAC.01710-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zheng JH, Rower C, McAllister K, et al. Application of an intracellular assay for determination of tenofovir-diphosphate and emtricitabine-triphosphate from erythrocytes using dried blood spots. J Pharm Biomed Anal. Apr 2016;122:16–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2016.01.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stranix-Chibanda L, Anderson PL, Kacanek D, et al. Tenofovir diphosphate concentrations in dried blood spots from pregnant and postpartum adolescent and young women receiving daily observed pre-exposure prophylaxis in sub-Saharan Africa. Clin Infect Dis. Dec 2020;doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pintye J, Kinuthia J, Abuna F, et al. Frequency and predictors of tenofovir-diphosphate detection among young Kenyan women in a real-world pre-exposure prophylaxis implementation program. Clin Infect Dis. Feb 2020;doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang J, Li C, Xu J, et al. Discontinuation, suboptimal adherence, and reinitiation of oral HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis: a global systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet HIV. Apr 2022;9(4):e254–e268. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(22)00030-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Joseph Davey D, Nyemba DC, Castillo-Mancilla J, et al. Adherence challenges with daily oral pre-exposure prophylaxis during pregnancy and the postpartum period in South African women: a cohort study. J Int AIDS Soc. Dec 2022;25(12):e26044. doi: 10.1002/jia2.26044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bulterys MA, Mujugira A, Nakyanzi A, et al. Costs of Providing HIV Self-Test Kits to Pregnant Women Living with HIV for Secondary Distribution to Male Partners in Uganda. Diagnostics (Basel). May 19 2020;10(5)doi: 10.3390/diagnostics10050318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ashburn K, Antelman G, N’Goran MK, et al. Willingness to use HIV self-test kits and willingness to pay among urban antenatal clients in Cote d’Ivoire and Tanzania: a cross-sectional study. Trop Med Int Health. September 2020;25(9):1155–1165. doi: 10.1111/tmi.13456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hershow RB, Zimba CC, Mweemba O, et al. Perspectives on HIV partner notification, partner HIV self-testing and partner home-based HIV testing by pregnant and postpartum women in antenatal settings: a qualitative analysis in Malawi and Zambia. J Int AIDS Soc. July 2019;22 Suppl 3:e25293. doi: 10.1002/jia2.25293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Choko AT, Fielding K, Johnson CC, et al. Partner-delivered HIV self-test kits with and without financial incentives in antenatal care and index patients with HIV in Malawi: a three-arm, cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet Glob Health. July 2021;9(7):e977–e988. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(21)00175-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mujugira A, Nakyanzi A, Nabaggala MS, et al. Effect of HIV Self-Testing on PrEP Adherence Among Gender-Diverse Sex Workers in Uganda: A Randomized Trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. Apr 01 2022;89(4):381–389. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000002895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pintye J, Drake AL, Begnel E, et al. Acceptability and outcomes of distributing HIV self-tests for male partner testing in Kenyan maternal and child health and family planning clinics. AIDS. Jul 2019;33(8):1369–1378. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000002211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Joseph Davey D, Nyemba D, Mvududu R, et al. PrEP CONTINUATION AND OBJECTIVE ADHERENCE IN PREGNANT/POSTPARTUM SOUTH AFRICAN WOMEN (Abstract No. 704). presented at: Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI) 2022; 2022; Virtual. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tetteh RA, Yankey BA, Nartey ET, Lartey M, Leufkens HG, Dodoo AN. Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis for HIV Prevention: Safety Concerns. Drug Saf. Apr 2017;40(4):273–283. doi: 10.1007/s40264-017-0505-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pintye J, Rogers Z, Kinuthia J, et al. Two-Way Short Message Service (SMS) Communication May Increase Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis Continuation and Adherence Among Pregnant and Postpartum Women in Kenya. Glob Health Sci Pract. Mar 2020;doi: 10.9745/GHSP-D-19-00347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Saidi F, Chi BH. Human Immunodeficiency Virus Treatment and Prevention for Pregnant and Postpartum Women in Global Settings. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. Dec 2022;49(4):693–712. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2022.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dearborn JL, Lewis J, Mino GP. Preventing mother-to-child transmission in Guayaquil, Ecuador: HIV knowledge and risk perception. Glob Public Health. 2010;5(6):649–62. doi: 10.1080/17441690903367141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Darak S, Gadgil M, Balestre E, et al. HIV risk perception among pregnant women in western India: need for reducing vulnerabilities rather than improving knowledge! AIDS Care. 2014;26(6):709–15. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2013.855303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kinuthia J, Pintye J, Mugwanya K, et al. High PrEP uptake among Kenyan pregnant women offered PrEP during routine antenatal care (Abstract #1366). presented at: Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI); 2018; Boston, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Swartzendruber A, Steiner RJ, Adler MR, Kamb ML, Newman LM. Introduction of rapid syphilis testing in antenatal care: A systematic review of the impact on HIV and syphilis testing uptake and coverage. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. Jun 2015;130 Suppl 1:S15–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2015.04.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.World Health Organization. Global guidance on criteria and processes for validation: elimination of mother-to-child transmission (EMTCT) of HIV and syphilis. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Looker KJ, Magaret AS, May MT, et al. First estimates of the global and regional incidence of neonatal herpes infection. Lancet Glob Health. Mar 2017;5(3):e300–e309. doi: 10.1016/s2214-109x(16)30362-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.World Health Organization. Guidelines for the Management of Sexually Transmitted Infections. Revised 2003. ISBN 92 4 154626 3. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/42782/1/9241546263_eng.pdf

- 57.Nyemba D, Peters R, Medina-Marino A, et al. SCREENING OF STIs IN PREGNANCY AND PREGNANCY OUTCOMES IN WOMEN WITH AND WITHOUT HIV (Abstract No. 886). presented at: Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI) 2022; 2022; Virtual. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mogaka J, FAbuna F, Dettinger J, et al. HIGH ACCEPTABILITY OF STI TESTING AND EPT AMONG PREGNANT KENYAN WOMEN INITIATING PREP (Abstract Submission ID 1346185). presented at: Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI) 2023; 2023; Seattle, WA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- 59.de Voux A, Mvududu R, Happel A, et al. Point-of-Care Sexually Transmitted Infection Testing Improves HIV Preexposure Prophylaxis Initiation in Pregnant Women in Antenatal Care in Cape Town, South Africa, 2019 to 2021. Sex Transm Dis. Feb 01 2023;50(2):92–97. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000001729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Thirumurthy H, Masters SH, Mavedzenge SN, Maman S, Omanga E, Agot K. Promoting male partner HIV testing and safer sexual decision making through secondary distribution of self-tests by HIV-negative female sex workers and women receiving antenatal and post-partum care in Kenya: a cohort study. Lancet HIV. Jun 2016;3(6):e266–74. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(16)00041-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Musinguzi N, Kidoguchi L, Mugo NR, et al. Adherence to recommendations for ART and targeted PrEP use among HIV serodiscordant couples in East Africa: the “PrEP as a bridge to ART” strategy. BMC Public Health. Oct 28 2020;20(1):1621. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09712-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.