Abstract

We describe a case of coccidioidomycosis in which several unusual morphologic forms of Coccidioides immitis occurred in biopsy tissue from the right lower lung of a patient. To our knowledge, this is the first case where so many diverse morphologic forms were manifested in a single patient in the absence of typical endosporulating spherules. Immature spherules demonstrating segmentation mimicked morula forms of Prototheca spp. Certain elements resembled budding cells of Blastomyces dermatitidis. These consisted of juxtaposed immature spherules without endospores, a germinating endospore, or thick-walled hyphal cells. Branched, septate hyphae and moniliform hyphae consisting of chains of thick-walled arthroconidia or immature spherules were also present. Complement fixation and immunodiffusion tests performed on the patient’s serum were negative for C. immitis, B. dermatitidis, and Histoplasma capsulatum antibodies. Fluorescent-antibody studies were carried out with a specific C. immitis conjugate. All of the diverse fungal tissue elements stained positive with a moderate to strong (2 to 3+) intensity.

Coccidioides immitis, a dimorphic fungus, manifests wide morphologic variation in its mycelial as well as its parasitic form. In its mycelial form, fast-growing colonies may vary in texture from cottony to velvety, powdery, or granular with smooth, folded, or zonate surfaces. Even though the majority of isolates produce dull white colonies in culture, atypical variants producing gray, lavender, buff, lemon yellow, or brown colonies have been described in the literature (4, 5, 7).

In tissue, C. immitis typically forms spherules containing endospores. Infrequently, it produces uncharacteristic hyphae forming arthroconidia in cavitary lesions or air spaces in the lungs or in pleural spaces (2, 3, 14–17, 20). In rare cases, appressed immature or atypical spherules resembling budding cells of Blastomyces dermatitidis have been reported (9, 16). We describe a human case in which several unusual morphologic forms of C. immitis occurred concomitantly in a lung tissue specimen. Multiple diverse morphologic forms, any of which could lead to an incorrect diagnosis, are described herein.

Case report.

The patient, an 80-year-old male, was admitted on 11 November 1994 for a workup on a cavitary lesion (2 by 2 cm) in the right lower lung. The patient was seen by one of us (G.V.) because histologic examination of his resected lung was positive for fungal elements. He had lived in San Francisco, Calif., for 1.5 years, and during that time he had visited Arizona, New Mexico, and the Rio Grande valley, areas known to be endemic for coccidioidomycosis. Hospital records indicated that other travel occurred at unspecified times to Michigan, northeastern Mexico, Philippines, Utah, and Washington, D.C. A bronchoscopy and a needle biopsy examination were nondiagnostic. Resection of the right lower lobe of the lung was done to rule out and treat possible cancer. No attempt was made to culture the biopsied tissue. Histologic examination of the biopsied tissue revealed what were believed to be broad-based, yeast-like cells and, in some areas, delicate, septate hyphal elements. A tentative diagnosis of blastomycosis was made. Treatment with itraconazole (400 mg/day) was initiated.

The patient’s serum and sections of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded lung tissue were submitted to the Mycoses Immunodiagnostic Laboratory of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for serologic and histologic studies. Tissue sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin and Gomori-methenamine silver (GMS). Complement fixation and immunodiffusion tests were performed for B. dermatitidis, C. immitis, and Histoplasma capsulatum antibodies and interpreted in accordance with protocols described earlier (8). None of these antibody tests were positive. Although blastomycosis and histoplasmosis were included in the differential diagnosis, the presence of branching septate and moniliform hyphae and morula-like bodies in the biopsied tissue was not consistent with the in vivo morphological manifestations of B. dermatitidis and H. capsulatum. These findings together with the patient’s travel history suggested a possible diagnosis of coccidioidomycosis. Accordingly, our initial approach was to stain the tissue with a C. immitis-specific conjugate.

Immunofluorescence staining.

Deparaffinized tissue sections were treated with 1% trypsin for 45 min (11). Specific fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated rabbit C. immitis antiglobulins were prepared, and direct staining was performed in accordance with the method of Kaplan and Clifford (6). Tissues treated with the labeled C. immitis antiglobulins were examined with a Leitz Ortholux II incident-light fluorescence microscope. A specimen was considered positive if the fungal elements stained weakly (1+) or with a greater intensity.

Sections stained with GMS showed fungal elements exhibiting a wide variety of morphologic forms, none of which were pathognomonic for any particular fungal pathogen. Some spherule-like elements showed multiple cleavages in different planes that resembled the morula forms of Prototheca spp. (Fig. 1). Others occurred as oval to spherical cells either singly, in pairs, in groups of three to five, or sometimes in small chains (Fig. 1). Typical mature spherules with endospores were not observed. Fungal cells forming germ tubes (Fig. 2) and appressed hyphal cells with thick walls mimicked the broad-based budding cells of B. dermatitidis (Fig. 3). There were septate, hyphal elements of various lengths present. Some of the hyphal cells that were aligned in a row became thick-walled, resembling moniliform hyphae (Fig. 4). In other areas, septate, branched hyphal elements of various lengths were also observed (Fig. 5). A hematoxylin-and-eosin-stained slide revealed the fungal elements to be hyaline.

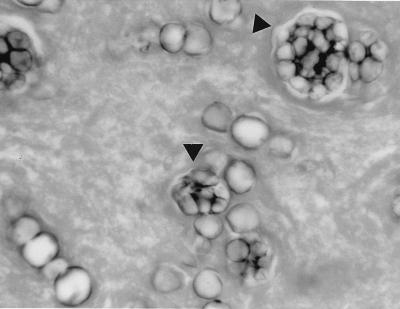

FIG. 1.

Biopsied tissue section of the lung with spherule-like cells showing multiple cleavages (arrowheads) that resemble cells of Prototheca spp. and other oval to spherical cells occurring singly, in pairs, or in small chains. GMS stain. Magnification, ×743.

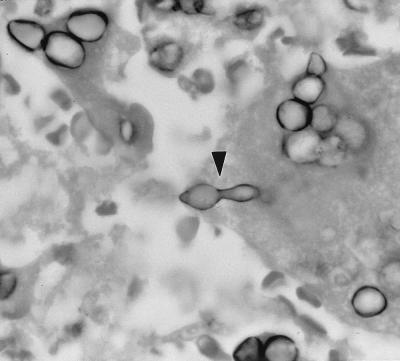

FIG. 2.

C. immitis endospore or arthroconidium (arrowhead) forming a germ tube that resembles budding cells of B. dermatitidis. GMS stain. Magnification, ×875.

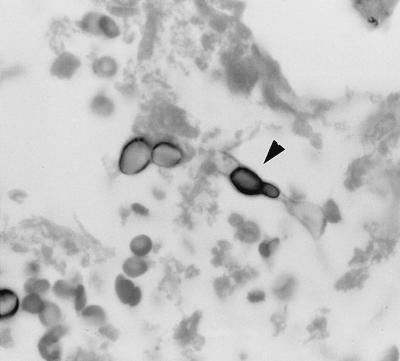

FIG. 3.

Thick-walled, adjoining hyphal cells (arrowhead) mimicking broad-based budding cells of B. dermatitidis. GMS stain. Magnification, ×875.

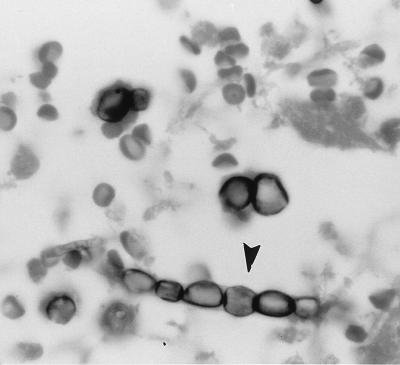

FIG. 4.

Thick-walled hyphal cells in a row resembling moniliform hyphae (arrowhead). GMS stain. Magnification, ×875.

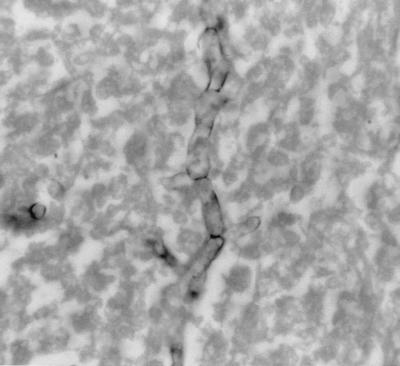

FIG. 5.

A branched septate hypha of C. immitis. GMS stain. Magnification, ×875.

Immunofluorescence studies of biopsy tissue with a C. immitis-specific conjugate revealed the fungal elements to be those of C. immitis. The conjugate stained the young spherules, hyphal cells, and moniliform hyphal elements with a 2 to 3+ intensity.

Atypical forms of C. immitis in tissues from humans have been recognized in several studies (2, 3, 12, 14, 15, 17, 19, 20). Immature spherules frequently cannot be distinguished from budding cells of B. dermatitidis, H. capsulatum var. duboisii, or Prototheca spp. On occasion, one or two diverse forms, such as hyphal elements with or without arthroconidia or appressed cells resembling budding cells of B. dermatitidis, occur, and in most instances they are accompanied by the typical endosporulating spherules. In the present study, exhaustive microscopic examination of numerous fields of the biopsied tissue sections revealed only the existence of the four aforementioned diverse morphologic forms of C. immitis (morula-like, broad-based yeast-like, moniliform, and true hyphae). The observation of cells resembling the morulas of Prototheca spp. was an unusual one for us. However, such structures were observed for an earlier case of coccidioidomycosis (12). Any of the four atypical forms could be confused with the tissue forms of other pathogenic fungi. Histologic diagnosis was complicated because none of these diverse forms were found in association with typical elements of C. immitis. Diagnosis of coccidioidomycosis was achieved by identifying the polymorphic forms by using a C. immitis fluorescent-antibody reagent. The value of using multiple methods for establishing a diagnosis cannot be overemphasized. In this study, culture was not attempted and serologic tests were negative. Negative serologic tests are not unusual with sera from patients with coccidioidal cavitary disease. Approximately 40% of patients with coccidioidal pulmonary cavitation may be negative for coccidioidomycosis by serologic tests (18). However, a higher percentage of such patients might be serodiagnosed by immunodiffusion testing of concentrated sera (13). Histologic results were equivocal, and the use of a specific fluorescent-antibody reagent established the diagnosis. Culture remains the most reliable means to establish a definitive diagnosis. Even though no attempts were made to culture the tissue in our case, we stress the need for surgeons and operating room assistants to conserve tissue for culture.

With the greater frequency in international travel, the incidence of coccidioidomycosis is increasing in areas where this infection was not previously seen. Cases were recently identified in India and Japan, where 1 and 14 cases of coccidioidomycosis, respectively, were documented in the literature (1, 10). Of the 14 patients, 12 had a history of travel to areas where coccidioidomycosis is endemic. In two Japanese patients, there was no history of travel to the areas of endemicity, but both patients worked in cotton mills and handled raw cotton imported from areas of endemicity, which exposed them to the infectious arthroconidia of C. immitis. These facts emphasize not only the importance of noting the patient’s history of travel to areas of endemicity but also any contact with materials imported from areas of endemicity that can serve as a source of C. immitis. Equally important is the need for laboratorians to be aware of the diverse manifestations of C. immitis in tissue which can lead to misdiagnoses.

Acknowledgments

We thank D. Pappagianis, Department of Medical Microbiology and Immunology, University of California School of Medicine, Davis, for his constructive suggestions and criticism.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bharucha N E, Ramamoorthy K, Sorabjee J, Kuruvilla T. All that caseates is not tuberculosis. Lancet. 1996;348:1313. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(05)65793-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dolan M J, Lattuada C P, Melcher G P, Zellmer R, Allendoerfer R, Rinaldi M G. Coccidioides immitis presenting as a mycelial pathogen with empyema and hydropneumothorax. J Med Vet Mycol. 1992;30:249–255. doi: 10.1080/02681219280000311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fee H J, McAvoy J M, Michals A A, Gold P M. Unusual manifestations of Coccidioides immitis infection. J Cardiovasc Surg. 1977;74:548–550. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huppert M, Sun S H, Bailey J W. Natural variability in Coccidioides immitis. In: Ajello L, editor. Coccidioidomycosis. Tucson: University of Arizona Press; 1967. pp. 323–328. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huppert M, Sun S H, Rice E H. Specificity of exoantigens for identifying cultures of Coccidioides immitis. J Clin Microbiol. 1987;8:346–348. doi: 10.1128/jcm.8.3.346-348.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaplan W, Clifford M K. Production of fluorescent antibody reagents specific for the tissue form of Coccidioides immitis. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1964;89:651–658. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1964.89.5.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaufman L, Standard P G. Specific and rapid identification of medically important fungi by exoantigen detection. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1987;41:209–225. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.41.100187.001233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaufman L, Kovacs J A, Reiss E. Clinical immunology. In: Rose N R, Conway de Macario E, Folds J D, Lane H C, Nakamura R M, editors. Manual of clinical laboratory immunology. 5th ed. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1997. pp. 585–604. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kwon-Chung K J, Bennett J E. Medical mycology. Philadelphia, Pa: Lea and Febiger; 1992. pp. 356–396. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ogiso A, Ito M, Koyama M, Yamaoka H, Hotchi M, McGinnis M R. Pulmonary coccidioidomycosis in Japan: case report and review. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;25:1260–1261. doi: 10.1086/516970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Palmer D F, Kaufman L, Kaplan W, Cavallaro J J. The fluorescent antibody technique. In: Balows A, editor. Serodiagnosis of mycotic diseases. Springfield, Ill: Charles C Thomas, Publisher; 1977. pp. 143–153. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pappagianis D. Coccidioidomycosis. In: Balows A, Hausler W J Jr, Ohashi M, Turano A, editors. Laboratory diagnosis of infectious diseases: principles and practice. Vol. 1. New York, N.Y: Springer-Verlag; 1988. pp. 600–623. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pappagianis D, Zimmer B L. Serology of coccidioidomycosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1990;3:247–268. doi: 10.1128/cmr.3.3.247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Puckett T F. Hyphae of Coccidioides immitis in tissues of human host. Am Rev Tuberc. 1954;70:320–327. doi: 10.1164/art.1954.70.2.320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Putnam J S, Harper W K, Green J F, Nelson K G, Zurek R C. Coccidioides immitis. A rare cause of pulmonary mycetoma. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1975;112:733–738. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1975.112.5.733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rippon J W. Coccidioidomycosis. In: Rippon J W, editor. Medical mycology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: The W. B. Saunders Co.; 1988. pp. 433–473. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rohatgi P K, Schimitt R G. Pulmonary coccidioidal mycetoma. Am J Med. 1984;76:734–736. doi: 10.1097/00000441-198405000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith C E, Saito M T, Simons S A. Pattern of 39,500 serologic tests in coccidioidomycosis. J Am Med Assoc. 1956;160:546–552. doi: 10.1001/jama.1956.02960420026008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thadepalli H, Salem F A, Mandal A K, Rambhatla K, Einstein H E. Pulmonary mycetoma due to Coccidioides immitis. Chest. 1977;71:429–430. doi: 10.1378/chest.71.3.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wolf J E, Little J R, Pappagianis D, Kobayashi G S. Disseminated coccidioidomycosis in a patient with the acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1986;5:311–336. doi: 10.1016/0732-8893(86)90038-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]